1. Introduction

Over the past century, the concept of prejudice has become increasingly central to scientific thinking about relations between groups, marking a profound moral and political, as well as a conceptual shift. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many scholars favoured conceptual frameworks based around notions of group differences, hierarchy, and biological inheritance (e.g., see Goldberg Reference Goldberg1993; Haller Reference Haller1971). By rooting the causes of ethnic and racial hostility in the supposed characteristics of its targets, these scholars upheld the traditional doctrine of the “well-deserved reputation” (Zawadzki Reference Zawadzki1948). Between the 1920s and 1940s, however, an “abrupt reversal” (Samelson Reference Samelson1978) occurred in scientific thinking. Rather than crediting it to the inherited deficiencies of minorities, social disharmony was attributed increasingly to the bigotry of majority group members.Footnote 1 In the years following the end of World War II, the concept of prejudice became central to the explanation of a range of social problems, including problems of discrimination, inequality, ideological extremism, and genocide. By the 1950s, prejudice research had “spread like a flood both in social psychology and in adjacent social sciences” (Allport Reference Allport1951, p. 4). The deluge continued in subsequent decades, and prejudice rapidly became a fundamental concept within research on intergroup relations.

Yet what is prejudice? The modern roots of the term lie in the eighteenth century with enlightenment liberalism, which distinguished opinions based on religious authority and tradition from opinions based on reason and scientific rationality (Billig Reference Billig1988). The legacy of this ideological heritance has been prominent in modern research, which often treats prejudice as a form of thinking that distorts social reality, leading us to judge “a specific person on the basis of preconceived notions, without bothering to verify our beliefs or examine the merits of our judgements” (Saenger Reference Saenger1953, p. 3).

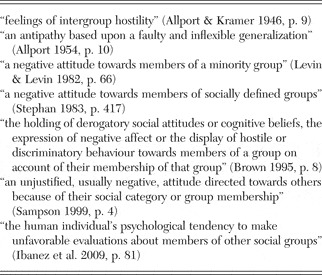

However, prejudice has seldom been treated purely as a matter of irrational beliefs. It has also been widely characterized as a negative evaluation Footnote 2 of others made on the basis of their group membership (see Table 1). The nature of the relationship between the cognitive and affective dimensions of this kind of evaluation has, of course, generated considerable debate. For some researchers, prejudice should be regarded as an indissoluble combination of both; for others, emotional antipathy lies at the core of the problem, with concepts such as stereotyping being treated as empirically related but analytically distinct (e.g., see Duckitt Reference Duckitt1992, pp. 11–13). Likewise, although most researchers have conceived prejudice as a generic negative response to members of another group, others have attempted to differentiate emotional subcategories. Kramer (Reference Kramer1949) was an early advocate of this approach. His work prefigured recent developments in research on intergroup emotions, evolutionary psychology, and social neuroscience, which has increasingly focused on target-specific reactions such as fear, anger, and disgust and on the evolutionary and neurological mechanisms that underpin such reactions (e.g., see Cottrell & Neuberg Reference Cottrell and Neuberg2005; Harris & Fiske Reference Harris and Fiske2006; Neuberg et al. Reference Neuberg, Kenrick and Schaller2011; Phelps et al. Reference Phelps, O'Connor, Cunningham, Funayama, Gatenby, Gore and Banaji2000).

Table 1. Some definitions of prejudice

The underlying causes of our negative evaluations of others have also been subject to considerable debate, and theoretical accounts have shifted over time. Explanations of prejudice have been grounded variously in personality development, socialization, social cognition, evolutionary psychology, and neuroscience, as well as in sociological theories of normative and instrumental conflict (for overviews, see Brown Reference Brown1995; Dovidio Reference Dovidio2001; Dovidio et al. Reference Dovidio, Glick and Rudman2005; Duckitt Reference Duckitt1992; Nelson Reference Nelson2009; Neuberg & Cottrell Reference Neuberg., Cottrell, Schaller, Simpson and Kenrick2006; Quillian Reference Quillian2006; Wetherell & Potter Reference Wetherell and Potter1992). Moreover, whereas earlier theories focused on “hot,” direct, and explicit forms of prejudice (e.g., Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford1950; Dollard et al. Reference Dollard, Doob, Miller, Mowrer and Sears1939; Sherif et al. Reference Sherif, Harvey, White, Hood and Sherif1961), modern theories often prioritize “cool,” indirect, and implicit evaluations (e.g., Dovidio & Gaertner Reference Dovidio, Gaertner and Zanna2004; Kinder & Sears Reference Kinder and Sears1981; Pettigrew & Meertens Reference Pettigrew and Meertens1995). Notwithstanding this historical and conceptual complexity, at the heart of most prejudice research is a deceptively simple question: Why don't we like one another?

This question also underlies a closely related body of research on prejudice reduction, which encompasses work on interventions such as reeducation, perspective taking, cooperative learning, common identification, empathy arousal, and intergroup contact (e.g., Aronson & Patnoe Reference Aronson and Patnoe1997; Lilienfeld et al. Reference Lilienfeld, Ammirati and Landfield2009; Pettigrew & Tropp Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2006; Stephan & Finlay Reference Stephan and Finlay1999). Although evidence of their effectiveness has been challenged (Paluck & Green Reference Paluck and Green2009), such interventions are typically portrayed as a shining example – perhaps the shining example – of how social science research on intergroup relations can promote a better society (e.g., see Brewer Reference Brewer1997). To be sure, in meeting the challenge of prejudice reduction, researchers have adopted varying theoretical perspectives, with varying implications for how processes of change are formulated. Perspectives treating prejudice as the outcome of deep-seated personality dynamics, for example, have constructed the problem of change differently than perspectives treating it as the outcome of more tractable forces such as social norms (e.g., Long Reference Long1951). Likewise, perspectives treating prejudice as a consciously held attitude have constructed change differently than perspectives treating it as an automatic and implicit process (e.g., Olson & Fazio Reference Olson and Fazio2006; Wheeler & Fiske Reference Wheeler and Fiske2005). By and large, however, advocates of prejudice reduction have united around a central imperative, which has become an interdisciplinary rallying call: How can we get individuals to think more positive thoughts about, and hold more positive feelings towards, members of other groups? In short, how can we get people to like each other?

The point of the present article is not to devalue research on prejudice or to deny its profound historical significance. Rather, we wish to explore the limits of the orthodox conception of prejudice as negative evaluation. What has this conception contributed to knowledge about relations between groups and what has it obscured? How effective or ineffective has it been in guiding attempts to improve such relations? This article has two main sections. The first section presents some critical alternatives to, or substantive elaborations of, the traditional concept of prejudice. We capitalize in particular on developments in research on paternalistic ideology, ambivalent sexism, infra-humanization, common identification, and intergroup helping. The second section interrogates the related process of prejudice reduction, focusing on emerging research on the paradoxical consequences of intergroup contact. We argue that it is especially in the arena of social change that the traditional concept of prejudice falls short, and developing this theme, we discuss the tensions between prejudice reduction and collective action models of change. The article's conclusion outlines directions for future research and recommends some ways in which researchers might move “beyond prejudice.”

2. Limits of a concept of prejudice as negative evaluation

2.1. The “velvet glove” of benign discrimination

Sherif's Summer Camp studies are amongst the most influential studies ever conducted on prejudice (Sherif et al. Reference Sherif, Harvey, White, Hood and Sherif1961). They are rightly heralded as classics in the psychological and sociological literature. By creating an experimental context in which groups of boys competed for scarce resources, Sherif and his collaborators famously manufactured forms of intergroup hostility that echoed all too starkly the violence of intergroup conflict in the real world. They demonstrated that ordinary children – with no prior history of animosity or special inclination towards bigotry – could rapidly develop many of the hallmarks of extreme prejudice if placed under the right structural conditions, including negative stereotyping, voluntary segregation, and verbal and physical aggression.

In a fascinating thought experiment, however, Mary Jackman (Reference Jackman1994) asks us to consider how events might have unfolded in these studies had the following conditions prevailed: (1) relations were protracted in time; (2) one group of boys achieved stable dominance over the other in terms of the commandeering of valued resources; and (3) that this dominance depended on their securing an ongoing transfer of benefits from the subordinate group. Such conditions, of course, mirror real relations of class, race, and gender more faithfully than the brief, equal status, zero sum competition engineered by Sherif. Jackman argues that these conditions also yield a very different pattern of intergroup responses than that evidenced by the Summer Camp studies.

The point of her thought experiment is not to discredit Sherif's contribution. Instead, Jackman wants to highlight the contextual specificity of the Summer Camp findings and to challenge the assumption that negative reactions typify everyday relations in historically unequal societies. To the contrary, she argues, real relations of domination and subordination are marked by emotional complexity and ambivalence, with positive responses such as affection and admiration mingling with negative responses such as contempt and resentment. Sherif's work constitutes the exception rather than the rule. According to Jackman (Reference Jackman1994; Reference Jackman, Dovidio, Glick and Rudman2005), it also captures a wider tendency for researchers to overemphasize the role of antipathy within discriminatory relations between groups.

Jackman's (Reference Jackman1994) landmark book, The Velvet Glove, addresses this problem, exposing the insidious role of positive intergroup emotions in the reproduction of systems of inequality. Under conditions of long-term, stable inequality, she contends, it is neither functional nor feasible for members of dominant groups to maintain uniformly negative attitudes towards subordinates. Given that dominants are dependent on subordinates' cooperation in order to sustain a smooth transfer of benefits (e.g., in the form of labour and services), the ideal social system is one of paternalism. Within paternalistic systems, role differentiation allows dominants to define the ideal characteristics of subordinates in ways that sustain the status quo and then to reward those who display these characteristics with affirmation, admiration, and even love. Such systems sugar-coat the harsh realities of inequality by framing social relations in more palatable terms for both dominant and subordinate group members. For dominants, exploitation is transformed into paternalistic regard. For subordinates, exploitation becomes more difficult to recognize and to resist. The bonds of connection fostered by paternalistic institutions encourage subordinates to identify with the very roles on which their subordination is founded. They nurture positive feelings for the dominant group and decrease the motivation to challenge the status quo, a point elaborated later in the article (sects. 3.1, 3.2, 4).

Gender relations provide the clearest illustration of paternalistic influences on intergroup attitudes, exposing the limits of a concept of prejudice based solely around negative evaluation. Such relations were largely ignored in early work in the field, when the foundations of prejudice research were laid. Yet few commentators would nowadays dispute that gender discrimination remains pervasive or that men are often its complicit beneficiaries. At the same time, evidence suggests that many men express warm emotional attitudes towards women. Indeed, they tend to like them more than they like other men, a phenomenon that is sometimes labeled, not a little ironically, the “women are wonderful effect” (Eagly & Mladinic Reference Eagly and Mladinic1989; Reference Eagly, Mladinic, Stroebe and Hewstone1993). If men behave in ways that maintain gender inequality and discriminate against women, then it is not because they feel some sort of generic hostility towards them. The traditional concept of prejudice as “unalloyed antipathy” (Glick & Fiske Reference Glick and Fiske2001, p. 109) does not seem to fit well.

2.2. Ambivalent sexism (and racism)

This paradox has been investigated recently by researchers working within the theoretical framework of Ambivalent Sexism developed by Peter Glick and Susan Fiske. According to Glick & Fiske (Reference Glick and Fiske2001), sexist attitudes come in two forms. Hostile Sexism (HS) refers to attitudes of overt “hostility towards women who challenge male power” (Glick et al. Reference Glick, Lameiras, Fiske, Eckes, Masser, Volpato, Manganelli, Pek, Huang, Sakalli-Uğurlu, Castro, Luiza, Pereira, Willemson, Brunner, Materna and Wells2004, p. 715), and this concept is broadly consistent with an approach that treats prejudice as negative evaluation. Benevolent Sexism (BS), by contrast, refers to attitudes that seem supportive towards women, treating them as “wonderful fragile creatures who ought to be protected and provided for by men” (Glick et al. Reference Glick, Lameiras, Fiske, Eckes, Masser, Volpato, Manganelli, Pek, Huang, Sakalli-Uğurlu, Castro, Luiza, Pereira, Willemson, Brunner, Materna and Wells2004, p. 715), but also as creatures who lack agency and independence.

HS and BS are manifest in all cultures and, according to Glick, Fiske, and others, their ubiquity expresses a fundamental ambivalence in attitudes towards women. On the one hand, as a subordinate group, women must be kept in their “proper place.” This encourages the derogation of those who threaten (the legitimacy of) male advantage. On the other hand, men are dependent on women for, among other benefits, the provision of emotional support, child care, and sexual gratification. This encourages the veneration of women who “know their place,” whose conformity to traditional gender roles inspires admiration, idealization, sacrifice, and protectiveness. In everyday situations, of course, the expression of these hostile or benevolent attitudes is highly flexible, varying, for example, according to whether female targets are perceived as undermining (e.g., “career woman”) or supporting (e.g., “homemaker”) the wider gender hierarchy (see also Eagly Reference Eagly, Eagly, Baron and Hamilton2004).

Ambivalent sexism theory is relevant to our argument here because it directly challenges the assumption that intergroup prejudice – and associated forms of discrimination – operates primarily via attitudinal negativity. The point of the theory is not simply to explain how men express and reconcile their polarized attitudes towards women, but also to highlight the broader ideological role of HS and BS in maintaining gender inequality. A number of issues are worth flagging here.

First, BS is associated with a range of discriminatory beliefs, attributions, and behaviours (e.g., see Abrams et al. Reference Abrams, Viki, Masser and Bohner2003; Chapleau et al. Reference Chapleau, Oswald and Russell2007; Rye & Meaney Reference Rye and Meaney2010). Yet because of its veneer of affectionate regard for (certain types of) women, BS is less readily perceived as sexist as HS (Barreto & Ellemers Reference Barreto and Ellemers2005). It is hence a defensible ideology in societies where gender equality is a social ideal. Second and related, as well as shaping men's gender attitudes, BS plays a powerful role in structuring women's attitudes towards other women. Longitudinal research indicates, for example, that women who score high on BS are more likely to express hostile attitudes towards their own gender in the future (Sibley et al. Reference Sibley, Overall and Duckitt2007). They are also more likely to judge women who transgress traditional gender roles harshly and to support female behaviour that affirms these roles, such as the use of beauty products (e.g., Forbes et al. Reference Forbes, Jung and Haas2006). Third, it is important to appreciate how hostile and benevolent attitudes act in tandem to sustain the status quo. Cross-national research suggests that individuals' scores on measures of BS and HS tend to be positively correlated and that national averages for both forms of sexism are elevated in societies with higher levels of gender inequality (Glick & Fiske Reference Glick and Fiske2001).

As this brief review illustrates, emerging research on Ambivalent Sexism has gone some way to answering Jackman's (Reference Jackman, Dovidio, Glick and Rudman2005, p. 89) call for researchers to “dethrone hostility” as the affective hallmark of discriminatory relations. To what extent, however, can work on attitudes in the field of gender relations be generalized to other kinds of intergroup relations?

Doubtless, gender relations are in several senses a “special case,” involving unusually intense forms of intimacy and interdependency (see also Glick & Fiske Reference Glick and Fiske1996). Even so, there is growing evidence that other kinds of intergroup relations may be characterized by a similar blend of positive and negative elements. Recent research on stereotype content demonstrates, for example, that groups other than women (e.g., the elderly) evoke paternalistic prejudices, which combine positive attributions of emotional warmth with negative attributions of intellectual incompetence. Conversely, other groups (e.g., Jews) evoke so-called “envious” prejudices, which combine attributions of intellectual competence with attributions of emotional coldness (see Cuddy et al. Reference Cuddy, Fiske, Glick and Zanna2008).

Along similar lines, Jackman (Reference Jackman1994; Reference Jackman, Dovidio, Glick and Rudman2005) holds that systems of domination other than patriarchy rely on a combination of negative and paternalistic attitudes, a claim supported by an array of historical evidence. Consider, for example, the history of slavery in the United States. In their monumental study of the mind of Southern slaveholders, Elizabeth Fox-Genovese and Eugene Genovese (2005) point out that enslaved people were widely viewed as a sacred trust to whom the owners owed paternal care. As an illustration, they cite one such slaveholder, John Hartwell Cocke, who insisted that dutiful slaves should be treated with “kindness, and even sometimes with indulgence” (p. 370) and condemned the whipping of a slave out of passion or malice as “absolutely mean and unmanly” (p. 370). In stark contrast, however, harsh measures to deal with undutiful slaves – those who malingered, stole, or absconded – were deemed not only permissible, but also necessary by slaveholders. As William Elliot told members of the State Agricultural Society of South Carolina in 1849, “against insubordination alone, we are severe” (p. 368, emphasis in the original).

This ambivalent alliance between paternalistic care and punitive aggression mirrors Glick and Fiske's (Reference Glick and Fiske2001) distinction between benevolent forms of sexism (expressed towards women who accept their dependency) and hostile forms (expressed towards those who challenge it). What Fox-Genovese & Genovese's (Reference Fox-Genovese and Genovese2005) analysis also confirms is that benevolence towards enslaved people was not associated with opposition to slavery. Rather, it was quite the opposite. By subscribing to a code of chivalry, slaveholders sought to depict slavery as “a system of organic social relations that, unlike the market relations of the free-labor system, created a bond of interest that encouraged Christian behaviour” (p. 368). After all, only if one was nice to one's chattel could one sustain the legitimizing myth that slavery was “a blessing to both master and slave” (p. 515).

Although slavery has long been abolished, Jackman (Reference Jackman1994) suggests that there remains a complex set of interrelations between benevolence, hostility, and racial inequality in our own times. Using national survey data on race attitudes in the United States, for example, she has shown that many white Americans (39%) who express inclusive feelings towards African Americans also express conservative or reactionary attitudes towards policies designed to create racial equality in the domains of housing, employment, and education. Positive intergroup emotions, in other words, happily coexist with rejection of race-targeted interventions, as depicted by the “paternalistic” quadrant of Figure 1. Of course, interpreting the implications of such findings is not straightforward, and resistance to interventions such as affirmative action in the workplace does not necessarily equate to racial discrimination. Moreover, Jackman's findings do not refute the claim that negative evaluations play a key role in maintaining ethnic and racial inequality in many contexts. Indeed, her analysis also shows that only a small percentage of white respondents (7%) who feel emotionally estranged from black people support race-targeted policies (the “tolerant” quadrant in Fig. 1), whereas a high percentage (39%) espouse either conservative or reactionary policy attitudes (the “conflictive” quadrant in Fig. 1). Nevertheless, her findings do indicate that antipathy is not the whole story of racial and ethnic discrimination, a theme that is being developed in other areas of research.

Figure 1. Configurations of interracial feelings and attitudes towards race-targeted policies, based on Jackman (Reference Jackman1994, p. 280). Respondents were classified as having Inclusive Feelings when their attitudes towards the out-group were similar to, or more positive than, their attitudes towards the in-group. Estranged Feelings were defined as feelings where the in-group was favoured over the out-group. Policy attitudes were classified as Affirmative when respondents' ratings suggested they believed the government should be doing more to promote racial equality in the areas of housing, employment, and education than they were currently doing. They were classified as Conservative or Reactionary when respondents' ratings indicated that the government was already doing enough or too much, respectively, to promote racial equality.

2.3. The spectrum of dehumanization: From genocidal hatred to loving condescension

As the term suggests, dehumanization is a process through which other people become perceived as “less than human.” This process has been associated historically with some of the most degrading expressions of prejudice. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine a more negative reaction than one that likens others to animals, filth, or disease, relegates them beyond the scope of justice (Opotow Reference Opotow1990), or targets them for mass extermination (Staub Reference Staub1989). Such brutal expressions of prejudice concerned researchers in the period following World War II and continue to blight relations in many societies. They are undoubtedly linked to powerful negative emotions such as hatred and disgust (e.g., Goff et al. Reference Goff, Eberhardt, Williams and Jackson2008; Harris & Fiske Reference Harris and Fiske2006). As the most recent wave of research illustrates, however, dehumanization also assumes subtler forms that are irreducible to affective and cognitive negativity (see Haslam Reference Haslam2006; Leyens et al. Reference Leyens, Demoulin, Vaes, Gaunt and Paladino2007 for overviews). In some circumstances, dehumanization expresses the kind of “benign” condescension of which Jackman (Reference Jackman1994; Reference Jackman, Dovidio, Glick and Rudman2005) and Glick and Fiske (Reference Glick and Fiske2001) have written.

Advances in this aspect of our understanding of dehumanization have been inspired by the work of Leyens and his colleagues, who identified a subtype of dehumanization now widely known as infra-humanization. In their seminal work, this research group demonstrated that individuals attribute “secondary emotions” (e.g., empathy, remorse) more readily to members of the in-group than to members of the out-group, but that no such difference occurs for the attribution of primary emotions (e.g., anger, happiness) (Leyens et al. Reference Leyens, Rodriguez, Rodriguez, Gaunt, Paladino, Vaes and Demoulin2001; Reference Leyens, Cortes, Demoulin, Dovidio, Fiske, Gaunt, Paladino, Rodriguez-Perez, Rodriguez-Torres and Vaes2003). Subsequent research has suggested that this process may occur both within our controlled and conscious judgments of others (Explicit Infra-humanization) and also within our uncontrolled and unconscious associations (Implicit Infra-humanization). Using sequential priming techniques, for example, Boccato et al. (Reference Boccato, Cortes, Demoulin and Leyens2007) found that respondents react more quickly to in-group/secondary emotion associations than to out-group/secondary emotion associations, supporting the claim that infra-humanization has an automatic component.

Many commentators have interpreted infra-humanization as a form of prejudice. After all, primary emotions are generally perceived as being shared by human beings and animals, whereas secondary emotions implicate moral, civil, and aesthetic qualities that are somehow “uniquely human” (Leyens et al. Reference Leyens, Rodriguez, Rodriguez, Gaunt, Paladino, Vaes and Demoulin2001). To deny that out-group members experience such emotions to the same degree as in-group members is thus to diminish their humanity. Infra-humanization and other forms of dehumanization often occur, however, in the absence of overt conflict between the groups involved (Leyens et al. Reference Leyens, Demoulin, Vaes, Gaunt and Paladino2007). Moreover, their expression is relatively independent of the negative evaluations highlighted by the traditional concept of prejudice: it is the nature of the emotional attributions (secondary versus primary) rather than their valence (negative versus positive) that is crucial to processes of infra-humanization.

Indeed, as Haslam and Loughnan (Reference Haslam, Loughnan, Dixon and Levine2012) have argued, even forms of dehumanization that are grounded in direct comparisons between people and animals do not necessarily entail antipathy. Saminaden et al. (Reference Saminaden, Loughnan and Haslam2010) found that members of so-called “primitive” or “traditional” cultures were implicitly associated with animals but that this association was not accompanied by negative evaluations. To the contrary, primitives were actually evaluated somewhat more positively than the members of the in-group. Haslam and Loughnan (Reference Haslam, Loughnan, Dixon and Levine2012) have suggested that such responses are congruent with idealised and superficially positive images of “the noble savage” – images in which members of “traditional” cultures are treated as authentic and innocent and thus in need of protection and “development.” In other words, they illustrate how dehumanization may sustain relations of benevolent paternalism as much as it does relations of genocidal hatred, a contradiction that would surprise few historians of Western colonialism (e.g., Said Reference Said1993).

2.4. Ironies of intergroup helping

Unlike dehumanization, helping is generally conceived as a pro-social phenomenon, involving elevated emotions such as empathy, compassion, and consideration. Given that people are generally more inclined to assist in-group than out-group members (e.g., Levine & Crowther Reference Levine and Crowther2008), helping across intergroup boundaries has been deemed an especially positive activity. As such, intergroup helping is sometimes used as a yardstick for judging the success of prejudice reduction interventions such as common identification. To cite one example: Nier et al. (Reference Nier, Gaertner, Dovidio, Banker and Ward2001) reported that white spectators at an American football game were significantly more helpful to a black confederate when he shared their university affiliation (indicated via clothing displays) than when he had a different university affiliation (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2. The relationship between the social identity displayed by a black confederate and support for assimilationist versus multicultural race-targeted policies (based on Dovidio et al. Reference Dovidio, Gaertner, Shnabel, Saguy, Johnson, Stürmer and Snyder2010).

However, helping relations also involve an inherent inequality. The act of giving signifies the power of a donor to confer benefits to a (needy) beneficiary and may hence produce status differences between them. Moreover, at least delivered in certain forms, helping may foster long-term relations of dependency and inequality. To use Nadler et al.'s (Reference Nadler, Halabi and Harpaz-Gorodeisky2007, p. 4) terminology: “the continuous downward flow of assistance can be conceptualized as a social barter where the higher status group provides caring and assistance to the lower status group, which reciprocates by accepting the social hierarchy and its place in it as legitimate.”

Gender relations again provide the most obvious illustration of the political complexity of helping relationships. The ability to cater to women's needs (e.g., economic welfare) has served historically as an ideological cornerstone of patriarchal relations and, in so “benefitting,” women have sacrificed power and autonomy. Over the past decade or so, however, Arie Nadler and his colleagues have identified analogous processes operating within other kinds of unequal intergroup relations (e.g., between Israeli Arabs and Jews) and have developed a general theoretical model of helping as a “status organizing process” (e.g., see Halabi et al. Reference Halabi, Dovidio and Nadler2008; Nadler Reference Nadler2002; Nadler & Halabi Reference Nadler and Halabi2006). Their work has shown that intergroup helping relations may service relations of domination in varying ways, depending on the prevailing ideological conditions.

In societies with secure and stable status hierarchies, helping relations often serve to justify the status quo. When an advantaged group caters to the needs of a disadvantaged group, and this assistance is treated as desirable and necessary, then power relations become ideologically reconstructed as moral responsibility. In societies marked by insecure and unstable status hierarchies, by contrast, helping may be a mechanism for reestablishing threatened power differentials. Revealingly, under such conditions, research suggests dominants tend to favour the provision of chronic, dependency-oriented help, which allows them to reassert control and shore up the status hierarchy. By contrast, subordinates tend to favour the kind of help that allows them to retain collective autonomy and efficacy. They have misgivings about help that entrenches the status hierarchy by enabling others to intervene in their affairs or break down self-reliance (see Nadler Reference Nadler, Sturmer and Synder2010).

Helping relations, in sum, illustrate our broader point that superficially positive behavior can have discriminatory consequences, being implicated in wider power struggles in historically unequal societies. One is reminded here of the words of Albert Camus, who once wrote that “The welfare of the people has always been the alibi of tyrants, and it provides the further advantage of giving the servants of tyranny a good conscience” (Camus Reference Camus, Camus and O'Brien1955/1961).

2.5. Common identification: The darker side of “we”

A similar kind of argument can be applied to processes of common identification. Proposed originally by Samuel Gaertner and Jack Dovidio, the so-called Common Identity Model holds that inducing members of different social groups (e.g., blacks and whites) to view one another as members of a shared in-group (e.g., Americans) tends to improve their intergroup attitudes, reducing intergroup bias and increasing positive responses such as liking and empathy (see Gaertner & Dovidio Reference Gaertner and Dovidio2000; Reference Gaertner, Dovidio and Nelson2009). Research on this model is now extensive and overwhelmingly supportive. Common identification is widely viewed as one of the most promising interventions to improve intergroup relations.

In an elaboration of their own model, however, Dovidio et al. (Reference Dovidio, Gaertner and Saguy2009) have discussed the so-called “the darker side of we,” exploring some of the unacknowledged consequences of social inclusion. First, they concede that the ideological terms of inclusion are often a site of intergroup struggle. Members of historically advantaged groups typically favour assimilative forms of inclusion (a “one-group” representation of common identity) that leave intact the existing status hierarchy, whereas members of disadvantaged groups prefer a dual-identity model, which tends to better protect their group interests (see also Dovidio et al. Reference Dovidio, Gaertner and Saguy2008). Second, although it reduces prejudice by encouraging us to like one another more, common identification does not necessarily lead to support for policies designed to produce structural change in historically unequal societies.

In a striking demonstration, Dovidio and colleagues exposed white students to a black “confederate” who displayed either a common category membership (University identity), a dual identity (black and a university identity), a black identity, or an individual identity (Dovidio et al. Reference Dovidio, Gaertner, Shnabel, Saguy, Johnson, Stürmer and Snyder2010). In line with the Common Identity Model, they found that levels of racial prejudice – both towards the confederate in particular and black people in general – were lowest amongst whites in the common category condition and levels of “empathic concern” were highest. However, they also found that this group showed least support for policies designed to encourage multiculturalism on campus and most support for assimilationist policies that effectively disregard “race” (see Fig. 2). To the extent that multicultural policies challenge the status quo more than assimilationist policies (e.g., by conferring selective benefits to black students) – and we concede that this is a controversial issue in its own right – then one could argue that perceived common identification had the ironic effect of increasing whites' resistance to meaningful social change.

Emerging research has also examined effects of common identification on the political attitudes of minority groups. Greenaway et al.'s (Reference Greenaway, Quinn and Louis2011) study of the consequences of appeals to “common humanity” provides a revealing illustration. Although this kind of appeal may unite the victims and perpetrators of historical atrocities, increasing “forgiveness” of perpetrators, Greenaway et al. argue that it may also reduce victims' intentions to engage in collective action to transform enduring inequalities. Recognizing their shared humanity with others, in other words, may encourage victims to accept discrimination rather than to do something about it. We develop this theme in section 3.

2.6. Summary and implications

In sum, several independent strands of research have recently converged to challenge the traditional concept of prejudice as negative evaluation. Research on dehumanization has demonstrated how social perceptions that sustain intergroup hierarchies may operate in ways that are orthogonal to emotional valence. Dehumanization often occurs in absence of rancor. Indeed, we may deprive others of full human status whilst retaining indifference or even a mild, if condescending, affection towards them – as long, that is, as they accept their dependent place. If subordinate group members begin to contest their dependency, then that is often when negativity kicks in.

Research on common identification suggests that even when we are successful in creating more positive intergroup attitudes, encouraging people to evaluate one another more favourably, we may leave unaltered the conservative policy orientations of the historically advantaged. Viewing others as part of a shared in-group, it seems, does not necessarily promote support change in a structural or institutional sense. Moreover, members of dominant groups lean towards “assimilative” forms of inclusion that preserve rather than challenge social inequalities.

Perhaps most worrying, research on paternalistic social relations has suggested that “benevolent” intergroup attitudes may not only coexist with social inequality, but also serve as a mechanism through which it is reproduced. Men generally express warm and protective, if not loving, attitudes towards women and reserve antipathy primarily for those who challenge the gender hierarchy. As work on Ambivalent Sexism (and also on racism) has evinced, however, patriarchal relations are sustained by the warmth as well as the antipathy. It is the former as much as the latter, for example, that encourages many women to “buy into” conventional forms of gender differentiation and indeed to take responsibility for policing their boundaries. In a similar way, attempts by dominant groups to “help” the disadvantaged – arguably the ultimate expression of pro-social sentiment – may carry consequences that entrench rather than challenge social inequalities. Although such interventions may be motivated by positive emotions (e.g., empathy for others) and carry other beneficial consequences, they may equally help to reproduce status differences between the advantaged and the disadvantaged. Helping is thus a double-edged sword.

3. The limits of a prejudice reduction model of social change

3.1. Two routes to social change in historically unequal societies

If negative evaluation of the disadvantaged is defined as the problem, then the emotional and cognitive rehabilitation of the advantaged becomes the solution. We need, by this logic, to get such people to like others more and to abandon their negative stereotypes. In due course, incidences of discrimination will decline, creating a more equitable society in which the potential for intergroup conflict wanes. The concept of prejudice, in short, implies a ready-made antidote, which is a model of social change grounded in the psychology of prejudice reduction (see Table 2, top panel).

Table 2. Two models of change in historically unequal societies

The main level of analysis at which this model operates is the individual, the person whose negative feelings and thoughts need to be changed. Of course, if change remained hidden in the recesses of the individual mind, then prejudice reduction interventions would have limited utility. Accordingly, most prejudice researchers presume that what happens inside our heads ultimately carries consequences at other levels of social reality. By changing individuals' prejudices, we also change how they relate to other people in their lives, and in turn this effect is believed to ripple outwards to shape wider patterns of intergroup conflict and discrimination. To be sure, the intermediate steps and processes through which this occurs are often underspecified. Nevertheless, we concur with Wright and Baray (Reference Wright, Baray, Dixon and Levine2012), who claim that most researchers presume prejudice reduction interventions have positive consequences that flow from a micro (individual) to a meso (interpersonal encounters and relationships) to a macro (institutional and intergroup relationships) level of analysis in order to create a more peaceful and just society.

Over the course of its history, this model of change has been periodically challenged. Some critics have argued that it individualises the historical, structural, and political roots of intergroup discrimination (e.g., Blumer Reference Blumer1958; Henriques et al. Reference Henriques, Hollway, Urwin, Venn and Walkerdine1984; Rose Reference Rose1956; Wetherell & Potter Reference Wetherell and Potter1992). Others have worried about the implication, embedded in several conceptualizations of prejudice, that social change is inevitably circumscribed by certain universal and intractable features of human psychology (e.g., Hopkins et al. Reference Hopkins, Reicher and Levine1997). Still others have questioned the strength of its supporting evidence (e.g., Paluck & Green Reference Paluck and Green2009) or directly challenged its underlying assumptions (Reicher Reference Reicher2007). Nevertheless, prejudice reduction remains the most intensively researched and passionately advocated perspective on how to improve intergroup relations, and it is particularly influential within the discipline of psychology.

Prejudice reduction is not, however, the only perspective. Table 2 (bottom panel) depicts a second model of social change that has engaged psychologists (e.g., Dion Reference Dion2002; Drury & Reicher Reference Drury and Reicher2009; Klandermans Reference Klandermans1997; van Zomeren et al. Reference van Zomeren, Postmes and Spears2008), along with historians (Rude Reference Rude1981; Thompson Reference Thompson1991; Tilly et al. Reference Tilly, Tilly and Tilly1975), political scientists (Ackerman & Kruegler Reference Ackerman and Kruegler1994; Piven & Cloward 1979; Roberts & Ash Reference Roberts and Ash2009; Ulfelder Reference Ulfelder2005), and sociologists (Smelser Reference Smelser1962; Tarrow Reference Tarrow2011; Turner & Killian Reference Turner and Killian1987). According to this model, dominant group members rarely (if ever) give away their power and privileges. Rather, these must be wrested from them by members of subordinate groups. The analytic focus therefore shifts away from the goodwill of dominants towards the resistance of subordinates. More specifically, this model highlights the role of collective action in achieving social justice. Its guiding assumption is that social change is predicated upon mass mobilization, a process that typically brings representatives of historically disadvantaged groups (who stand to benefit from change) into conflict with representatives of historically advantaged groups (who stand to lose out from change). Its significance is captured by Frances Fox Piven's contention that the “great moments of equalizing reform in American political history” (Reference Piven2008, p. 21) have come about through the exercise of disruptive collective action.

To illustrate this alternative to a prejudice reduction model of social change, let us consider what are arguably the three greatest moments of racial equalization in modern history: the end of apartheid in South Africa, civil rights reforms in the United States, and the abolition of New World slavery. In the case of apartheid, there is some controversy over whether the violent struggles of the African National Congress' (ANC's) armed wing Unkhonto we Sizwe or the nonviolent struggles of civic organizations and trade unions had a greater role in overturning the system (Zunes Reference Zunes1999). Yet there is little disagreement that change was principally down to black collective action. To say this is not to downplay either the role of international solidarity through the boycott movement or the role of white radicals and business organisations in securing the transition to majority rule. (Particularly in the twilight years of apartheid, for example, corporations such as Consolidated Gold Fields played an important part in bringing the State and the ANC together in negotiations and ensuring a peaceful end to the old system.) Nevertheless, as Harvey (Reference Harvey2003) relates in his book The Fall of Apartheid: “There can be no doubt that the black majority won South Africa's bitterly fought racial war,” even if, equally, there can be no doubt that “white surrender was conditional and took place well before military considerations alone would have dictated” (p. 2).

The achievement of U.S. civil rights followed a similar trajectory. Of course, white politicians and white radicals played an important role. Yet, as Oppenheimer (Reference Oppenheimer1994–1995) asks: What happened between April 1, 1963, when Kennedy opposed the introduction of a Civil Rights Act, and May 20, when he directed the Department of Justice to draft just such an Act (which was signed into law on July 2, 1964, by Lyndon Johnson)? His answer is admirably terse: “In a word – Birmingham” (p. 646). He is referring, of course, to the massive desegregation campaign led by Martin Luther King, Jr., who arrived in Birmingham, Alabama, on April 2, 1963. The resulting legislative changes had profound effects in all areas of American life, not least in the political domain. In 1965, only 193 black people held elected office in the entire United States. By 1985 – when Barack Obama began working as a political organizer in Chicago – the figure stood at 6,016 (Sugrue Reference Sugrue2010). And, of course, on November 4, 2008, Obama himself was elected as president. A popular slogan in the last days of his election campaign was “Rosa sat so Martin could walk/Martin walked so Obama could run/Obama is running so our children can fly” (cited in Sugrue Reference Sugrue2010). Or, as Obama himself acknowledged in his Selma speech of March 4, 2007: “I'm here because somebody marched” (full text available at http://blogs.suntimes.com/sweet/2007/03/obamas_selma_speech_text_as_de.html).

Finally, let us consider how slavery was abolished. This is an area of furious controversy (see, e.g., the debate in Drescher & Emmer Reference Drescher and Emmer2010), and the controversy is complicated by the fact that different dynamics were at play in the British, French, Spanish, and American instances of abolition (Blackburn Reference Blackburn2011). However, it is significant that the debate concerns the relative contribution of two different forms of collective action: on the one hand, the resistance of slaves themselves, and on the other, the agitation of the largely white-led abolitionist movement. In other words, it concerns the contribution of collective struggles both between and within the slave and “master” communities. What is not in question is: (a) that abolitionist movements were critical in rallying popular sentiment against slaveholding interests (Marques Reference Marques2006; Reference Marques, Drescher and Emmer2010b); (b) that the success of such movements was facilitated by crises or divisions in the slaveholding state (see Blackburn Reference Blackburn2011); and (c) above all, that slave revolts – or the threat of slave revolts – were critical in inspiring abolitionist movements and in ensuring their ultimate success (Marques Reference Marques, Drescher and Emmer2010a).

In all three examples, then, equality was won rather than given away. In all three, change was the result of sustained collective resistance rather than some kind of general improvement, whether incremental or dramatic, in intergroup attitudes. What is more, the examples illustrate that such collective resistance can occur at many levels. The struggle of the subordinate group against the dominant group – and hence the struggle to mobilise subordinate group members – often has a determining weight. However, the struggle within the dominant group should not be forgotten, a point to which we shall return in the conclusion of our article. For the rest of this section, though, we address the question of how the two traditions of research on social change depicted in Table 2 are interrelated.

Although these models have developed largely in isolation, in our experience most researchers presume that they are complementary to the broader project of improving relations between groups. Prejudice researchers concentrate on changing the hearts and minds of the advantaged; collective action researchers study how, when, and why the disadvantaged take political action to create more just societies. The models seem to fit together as different parts of the overall puzzle of social change. Recent research indicates, however, that their interrelationship may be more complicated and more vexed.

According to Steve Wright and colleagues, the two models of social change entail psychological processes that actually work in opposing directions (Wright Reference Wright, Brown and Gaertner2001; Wright & Baray Reference Wright, Baray, Dixon and Levine2012; Wright & Lubensky Reference Wright, Lubensky, Demoulin, Leyens and Dovidio2009). On the one hand, prejudice reduction diminishes our tendency to view the world in “us” versus “them” terms, encouraging us to view others either as individuals (e.g., Brewer & Miller Reference Brewer, Miller, Miller and Brewer1984), as part of a common in-group (e.g., Gaertner & Dovidio Reference Gaertner, Dovidio and Nelson2009), or at least as people who share “crossed” category memberships (e.g., Crisp & Hewstone Reference Crisp and Hewstone1999). Such interventions foster positive emotional responses towards others, such as empathy and trust, whilst decreasing negative responses such as anxiety and anger (e.g., Esses & Dovidio Reference Esses and Dovidio2002; Paolini et al. Reference Paolini, Hewstone, Cairns and Voci2004; Pettigrew & Tropp Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2008; Stephan & Finlay Reference Stephan and Finlay1999). For the most part, they also encourage participants to view one another as equal in status and sometimes involve active attempts to establish such equality, at least within the immediate context of intervention (e.g., see Riordan Reference Riordan1978). The overarching objective of this model of social change is to reduce intergroup conflict in historically divided societies, producing more stable and peaceful societies.

On the other hand, collective action interventions are based on the assumption that group identification is a powerful motor of social change. Within this model of change, an “us” versus “them” mentality is generally construed as functional and strategic: It encourages members of disadvantaged groups to display in-group loyalty and commitment to the cause of changing society, to form coalitions with similar groups, and, crucially, to act together in their common interest (Craig & Richeson Reference Craig and Richeson2012; Klandermans Reference Klandermans1997; Reference Klandermans2002; Tajfel & Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986; Wright & Baray Reference Wright, Baray, Dixon and Levine2012). Collective action also generally requires the emergence of “negative” intergroup emotions and perceptions, including anger and a sense of relative deprivation (e.g., Barlow et al. Reference Barlow, Sibley and Hornsey2012; Grant & Brown Reference Grant and Brown1995; van Zomeren et al. Reference van Zomeren, Spears, Fischer and Leach2004), which encourage group members to recognize injustice and status disparities and thus strive to change the status quo.Footnote 3 Its main goal is not to reduce but to instigate intergroup conflict in order to challenge institutional inequality. Conflict is viewed as the fire that fuels social change rather than as a threat to extinguish at the point of conflagration.

3.2. Paradoxical effects of intergroup contact

Recognition of the potentially contradictory relationship between these two models of social change has inspired research on the “ironic” effects of prejudice reduction on the psychology of the disadvantaged. This idea was originally mooted by Wright (Reference Wright, Brown and Gaertner2001), and other researchers are now developing some of his insights.

Emerging research has focused mainly on the impact of interventions to promote intergroup contact, extending work on the so-called contact hypothesis (Allport Reference Allport1954). The contact hypothesis is the most important tradition of research on prejudice reduction, and it has generated a vast research literature that spans a wide spectrum of disciplines, including sociology, psychology, and political science (e.g., see Allport Reference Allport1954; Brown & Hewstone Reference Brown, Hewstone and Zanna2005; Forbes Reference Forbes1997; Pettigrew & Tropp Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2006; Sigelman & Welch Reference Sigelman and Welch1993). Its basic premise is simple. Interaction between members of different groups reduces intergroup prejudice, particularly when it occurs under favourable conditions (e.g., equality of status between participants). Evidence supporting this idea is extensive and, many believe, conclusive. Pettigrew & Tropp's (Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2006) widely cited meta-analysis found that contact decreased prejudice in 94% of 515 studies reviewed. A follow-up analysis (Pettigrew & Tropp Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2008) suggested that this effect was largely explained by reductions in intergroup anxiety and increases in intergroup empathy, as well as by improvements in participants' knowledge about members of other groups.

Like most traditions of research on prejudice, research on the contact hypothesis has focused mainly on the reactions of members of historically advantaged groups. In some recent studies, however, the impact of contact on the psychology of the historically disadvantaged has been prioritized, with some provocative results.

Dixon, Durrheim, and colleagues conducted two national surveys of racial attitudes in South Africa (Dixon et al. Reference Dixon, Durrheim and Tredoux2007; Reference Dixon, Durrheim, Tredoux, Tropp, Clack and Eaton2010a). Their first survey explored the relationship between interracial contact and South Africans' support for race-targeted policies being implemented by the ANC government to redress the legacy of apartheid, including policies of land redistribution and affirmative action (Dixon et al. Reference Dixon, Durrheim and Tredoux2007). They identified a divergence in the results for white and black respondents. For whites, positive contact with blacks was positively correlated with support for government policies of redress; for blacks, positive contact with whites was negatively correlated with support for such policies. In other words, contact was associated with increases in whites' and decreases in blacks' support for social change. In their second survey, Dixon et al. (Reference Dixon, Durrheim, Tredoux, Tropp, Clack and Eaton2010a) investigated the relationship between interracial contact and black South Africans' perceptions of racial discrimination in the post-apartheid era. They found that respondents who reported having favourable contact experiences with whites also perceived the racial discrimination faced by their group to be less severe. As Figure 3 conveys, this effect was mediated both by perceived personal discrimination and by blacks' racial attitudes. That is, the inverse relationship between contact and judgments of collective discrimination was partly explained by reductions in respondents' sense of being personally targeted for racial discrimination, as well as increases in their positive emotions towards whites.

Figure 3. Indirect effects of contact quality on black South Africans' perceptions of group discrimination (taken from Dixon et al. Reference Dixon, Durrheim, Tredoux, Tropp, Clack, Eaton and Quayle2010b).

In a more recent study, Cakal et al. (Reference Cakal, Hewstone, Schwär and Heath2011) provided a partial replication and extension of Dixon et al.'s (Reference Dixon, Durrheim and Tredoux2007; Reference Dixon, Durrheim, Tredoux, Tropp, Clack and Eaton2010a) results. To simplify a more complex set of findings, they reported that contact had a so-called “sedative effective” on black South Africans' readiness to engage in collective action benefitting their in-group, which operated both directly and indirectly. On the one hand, positive contact with whites was associated directly with a reduced inclination to participate in collective action. On the other hand, such contact exercised an indirect effect on collective action by moderating participants' sense of relative deprivation. That is, for participants who had comparatively little contact with whites, a sense of relative deprivation was positively associated with collective action tendencies. However, this relationship did not emerge for participants who had comparatively higher levels of contact with whites.

These effects are not unique to the South African situation. Wright and Lubensky (Reference Wright, Lubensky, Demoulin, Leyens and Dovidio2009) reported that contact with white Americans reduced Africans' and Latin Americans' willingness to endorse group efforts to accomplish racial equality. Revealingly, as a collective action perspective would predict, this effect was mediated by shifts in their sense of identification with their respective ethnic groups. Similarly, in a longitudinal study conducted on a university campus in the United States, Tropp and colleagues found that making white friends tended to lower perceptions of racial discrimination and decrease support for ethnic activism amongst members of three minority groups (African American, Latin American, and Asian American) (Tropp et al. Reference Tropp, Hawi, van Laar and Levin2012). The effects were strongest for African Americans, the group that otherwise reported the highest levels of experienced discrimination and the greatest willingness to challenge such discrimination (e.g., through political demonstrations). Surveys conducted in Israel by Saguy et al. (Reference Saguy, Tausch, Dovidio and Pratto2009, study 2) and in India by Tausch et al. (Reference Tausch, Saguy and Singh2009) have confirmed these “ironic” consequences of intergroup contact. In both studies, positive contact was associated with reduced perceptions of social injustice and lowered support for social change amongst members of disadvantaged groups (Arab Israelis and Muslims). In both studies, too, such effects were indirect, being mediated by respondents' attitudes towards the out-group in question (Jewish Israelis and Hindus).

Saguy et al. (Reference Saguy, Tausch, Dovidio and Pratto2009, study 1) and Glasford and Calcagno (2011) have provided laboratory confirmation of these survey-based data, laying the foundations for a program of experimental work that warrants further development. Saguy et al. (Reference Saguy, Tausch, Dovidio and Pratto2009, study 1) created an experimental paradigm in which higher and lower power groups interacted under conditions that emphasized either their differences (less positive contact) or their commonality (more positive contact). Higher-power group members were then asked to distribute a series of rewards across the two groups, whilst lower-power group members estimated the nature of the resulting distribution. The results provided a stark demonstration of the “darker side” of both common identification and positive contact – two preeminent techniques of prejudice reduction. Participants in the low-power/common-identity/positive-contact cell consistently overestimated the extent to which higher-power participants would distribute rewards equitably. (In reality, the powerful group displayed a predictable pattern of in-group favouritism.) This study thus highlights the potential problem of nurturing positive intergroup evaluations whilst creating false expectations of equality amongst the disadvantaged.

Glasford and Calcagno (Reference Glasford and Calcagno2012) investigated the interrelations between commonality, intergroup contact, and political solidarity amongst members of historically disadvantaged groups. As research on both collective action and common identification would predict, their study showed that cueing a sense of common identity amongst members of black and Latin American communities in the United States increased their political solidarity; that is, their readiness to work together to improve the status of both groups. However, this effect was moderated by contact with members of the historically advantaged white community. Specifically, the more intergroup contact Latin Americans had with whites, the less effective the commonality intervention was in fostering their sense of political solidarity with blacks. Once again, notwithstanding its beneficial effects on intergroup attitudes and stereotypes, contact exercised a potentially counterproductive impact on the political consciousness of the disadvantaged. As Glasford and Calcagno (Reference Glasford and Calcagno2012) summarize: “The conflict of harmonious intergroup contact may lie in the fact that despite harmony leading to increased positive attitudes (Pettigrew & Tropp Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2006), it also has the potential to decrease a variety of social-change oriented responses among minority group members.” (p. 227).

3.3. Summary and implications

In this section, we have contrasted a prejudice reduction model of social change (based around getting dominant group members to like subordinate group members) with a collective action model (based around getting subordinate groups members to challenge dominant group advantage). Building on the work of Wright and colleagues, we have suggested that these models of change entail different, and potentially contradictory, psychological processes, as illustrated by recent research on the consequences of intergroup contact.

Such research indicates that contact with members of historically advantaged groups may improve the intergroup attitudes of the historically disadvantaged, but also, paradoxically, reduce the extent to which they acknowledge and challenge wider forms of social injustice or display solidarity with other disadvantaged communities. From a prejudice reduction perspective, we have a resounding success; from a collective action perspective, a dismal failure. Further, this work shows that the very processes that underpin prejudice reduction also help to explain the “ironic” impacts of intergroup contact on political attitudes. Perhaps most significant, several studies suggest that it is precisely because contact improves intergroup attitudes (prejudice reduction) that it also decreases perceptions of discrimination, support for race-targeted policies, and readiness to engage in collective action. When the disadvantaged come to like the advantaged, when they assume they are trustworthy and good human beings, when their personal experiences suggest that the collective discrimination might not be so bad after all, then they become more likely to abandon the project of collective action to change inequitable societies. Jackman's (Reference Jackman1994; Reference Jackman, Dovidio, Glick and Rudman2005) warning reverberates here. Inequality is maintained not only through emotional negativity and the exercise of repressive force, but also through the “coercive embrace” of an affectionate but conditional sense of inclusion.

4. Conclusions and future directions

For most of the history of prejudice research, negativity has been treated as its emotional and cognitive signature, a conception that continues to dominate work on the topic.Footnote 4 By this definition, prejudice occurs when we dislike or derogate members of other groups. We do not dispute that research in this tradition has focused attention on processes that are essential to understanding the nature of intergroup discrimination. Recent work, however, has complicated the idea that prejudice consists exclusively of negative evaluations, highlighting the need to develop what Eagly (Reference Eagly, Eagly, Baron and Hamilton2004) calls an “inclusive” conception of the role of intergroup emotions and beliefs in sustaining discrimination. A common theme in this research is its functionalist emphasis on the social and psychological processes that serve to reproduce unequal social relations, an emphasis that resonates with Rose's (1956, p. 5) early definition of prejudice as a “set of attitudes which causes, supports or justifies discrimination.” What is clear from evidence on topics such as paternalism, Ambivalent Sexism, common identification, intergroup contact, and intergroup helping is that “positive” evaluations of others may play as a central role within such processes as negative evaluations.

By necessity, our coverage of relevant literature has been selective. We have not had space to review, for example, emerging research on the “differentiated” nature of intergroup emotions (e.g., Mackie & Smith Reference Mackie and Smith2002) and stereotype content (Cuddy et al. Reference Cuddy, Fiske, Glick and Zanna2008) or on the broader factors that foster acceptance of unjust social systems amongst the historically disadvantaged (Jost et al. Reference Jost, Banaji and Nosek2004). Nevertheless, taken collectively, the research discussed in this article offers a compelling challenge both to the orthodox conception of prejudice as negative evaluation and to the assumption that getting us to like one another more is some kind of sine qua non for promoting social change. Although evidence has accumulated steadily for several years, it is perhaps only in the domain of gender research that this emerging perspective has had a substantial impact, notably through work on Ambivalent Sexism. However, the significance of the subtler forms of discrimination discussed in this article extends beyond gender relations. Paternalistic ideology pervades other forms of intergroup relations. It is perhaps in the arena of social change that the limitations of the traditional concept of prejudice as negative evaluation become most apparent.

4.1. Prejudice reduction and social change revisited: Some suggested parameters and future directions

The question of change has troubled us most whilst preparing this article. An enduring strength of work on prejudice, as noted in our introduction, is that it shifted the target of social science research on intergroup relations. The study of immutable and hierarchical differences between groups became recast as the study of dominant group bigotry; and in the wake of this paradigmatic “reversal” (Samelson Reference Samelson1978), a rich tradition of research on prejudice reduction was born. The latter stages of our article, however, have complicated this optimistic view of the contribution of prejudice reduction interventions. As it turns out, there is mounting evidence that nurturing bonds of affection between the advantaged and the disadvantaged sometimes entrenches rather than disrupts wider patterns of discrimination.

In this closing section, we offer some general reflections on possible routes forward. To begin with, we advocate three ways in which research on the consequences of prejudice reduction should be extended, which concern the importance of acknowledging: (a) the relational nature of intergroup attitudes and perceptions, (b) the political, as well as the emotional and cognitive, effects of prejudice reduction, and (c) the complex relationship between harmony and conflict in the transformation of historically unequal societies. To conclude, we then revisit the question of how, if at all, prejudice reduction and collective action models of social change might be reconciled.

4.1.1. Recovering the relational character of intergroup attitudes

Research on prejudice has generally focused on the attitudes of the historically advantaged. This pattern was established by formative work on the topic, which sought to redress the problems of racism and anti-Semitism in the United States. It shone a harsh spotlight on the bigotry of the white, Protestant majority. Yet it often left the reactions of blacks, Jews, and other minority groups in the shadows, implicitly casting them as passive targets of bigotry. Of course, this early work had admirable objectives. As an unintended consequence, however, it established a lacuna that has persisted to the present day: a failure to acknowledge, sufficiently, how intergroup attitudes emerge in and through the relational dynamics of interaction between groups, with the actions of members of one group (e.g., blacks) forming the context in which the reactions of the other (e.g., whites) take shape and find expression, and vice versa (see also Shelton Reference Shelton2000; Shelton & Richeson Reference Shelton and Richeson2006).

This neglect must be borne in mind when evaluating research on the consequences of prejudice reduction interventions. Typically, such interventions shape the experiences of members of both historically advantaged and disadvantaged groups (e.g., by fostering more frequent intergroup contact). Moreover, they shape not only the intergroup attitudes of each group independently, but also the overall nature of the relationship between them (e.g., by encouraging recategorization so that “us” and “them” become “we”). For much of the history of research on prejudice reduction, however, scholars have prioritized its effects on the responses of the historically advantaged and have left its effects on the psychology of the disadvantaged comparatively underspecified.

We recommend, then, that the relational implications of prejudice reduction be brought to the forefront of future research. If this is done, then we anticipate that the ironic consequences highlighted in the present article will become increasingly apparent. We also recommend that researchers move beyond a simple, dualistic, “dominant” versus “subordinate” group model in order to explore other kinds of relatedness. Building on Glasford and Calcagno's (Reference Glasford and Calcagno2012) study, for example, one might hypothesize that interventions designed to improve a subordinate group's attitudes towards a dominant group (e.g., by creating new forms of inclusion) may have unintended effects on its members' attitudes towards other subordinate groups. Not only may such interventions increase horizontal hostility (White & Langer Reference White and Langer1999), but also they may decrease the willingness of members of different subordinate groups to act collectively in their shared interest. This attitudinal pattern is prevalent in post-colonial societies in Africa and the near East, where the “divide and rule” strategies of colonial authorities were designed precisely to prevent the formation of rebellious alliances that might challenge the status quo.

4.1.2. Broadening the conception of a successful intervention “outcome.”

Researchers have employed varying indices when evaluating the success of prejudice reduction interventions, which have become more sophisticated over time. Indices of blatant and controlled intergroup attitudes have been complemented by indices of indirect and automatic attitudes. Self-report indices have been complemented by behavioral and physiological indices. Scales measuring generic antipathy have been complemented by scales measuring specific intergroup emotions and associated action tendencies. By and large, however, the definition of a successful intervention outcome has remained within the boundaries of a concept of prejudice as negative evaluation. As its benchmark, prejudice reduction research continues to track shifts in emotional antipathy and pejorative stereotyping (or close proxies).

This emphasis on the cognitive and emotional rehabilitation of the bigoted individual has led to an underutilization of other, equally important, measures of outcome. For one thing, it has downplayed the role of positive (or ambivalent) emotions in sustaining relations of discrimination and inequality, a possibility raised by the work reviewed in our article, as well as by other functionalist research on how intergroup attitudes and beliefs serve to reproduce status and power relations.Footnote 5 For another thing, it has submerged the political dimension of intergroup attitudes and perceptions of social reality. As Wright and Lubensky (Reference Wright, Lubensky, Demoulin, Leyens and Dovidio2009, p. 18) remarked: “When efforts to reduce prejudice focus exclusively on getting dominant group members to think nicer thoughts and feel positive emotions about the disadvantaged group, they may not necessarily increase support for broader structural and institutional changes.”

Consider, as an instructive example, research on whites' support for policies designed to promote racial equality. Several researchers have argued that such support declines as policies come to threaten the racial hierarchy more directly (e.g., see Bobo & Kluegel Reference Bobo and Kluegel1993; Dixon et al. Reference Dixon, Durrheim and Tredoux2007; Schuman et al. Reference Schuman, Steeh, Bobo and Krysan1997; Sears et al. Reference Sears, van Laar, Carrillo and Kosterman1997; Tuch & Hughes Reference Tuch and Hughes1996). Along these lines, for example, proponents of the Blumerian tradition of sociological research on prejudice have highlighted the evolution of what Bobo et al. (Reference Bobo, Kluegel, Smith, Tuch and Martin1997) have called a “kinder, gentler, anti-black ideology” in the United States, a set of political beliefs that justify racial inequality not in terms of the overt bigotry of “Jim Crow” racism, but in terms that are more defensible in the modern era. A key, and seemingly paradoxical, feature of this emerging ideology is that widespread acceptance of the principles of equality, integration, and anti-discrimination is offset by widespread resistance to their concrete implementation.

According to Jackman and Crane (Reference Jackman and Crane1986), this kind of attitudinal pattern is unlikely to be eradicated by traditional techniques of prejudice reduction, which put “parochial negativism” rather than political attitudes at the heart of the problem of social change. In their analysis of national survey data gathered in the United States, for example, they reported that interracial contact led whites to espouse greater emotional warmth towards blacks, but had little impact on their acceptance of government interventions to address racial injustice. Likewise, as we have discussed, common identification – another prominent technique of prejudice reduction – may increase dominant group members' emotional acceptance of minorities without increasing their willingness to embrace institutional change (Dovidio et al. Reference Dovidio, Gaertner, Shnabel, Saguy, Johnson, Stürmer and Snyder2010).

Our general point here is not that support for structural change is unaffected by prejudice reduction. It is that prejudice researchers need to adopt a broader conception of the ideal outcomes of intervention. In particular, we need to know more about the relationship between prejudice reduction and the political attitudes that sustain the institutional core of disadvantage in historically unequal societies, justifying an unequal distribution of wealth, opportunity, and political power. How, for example, does prejudice reduction shape dominant and subordinate group members' attributions about the causes of group differences in wealth and opportunity? How does it affect acceptance of ideological belief systems that either justify or challenge the status quo (see also Jost et al. Reference Jost, Banaji and Nosek2004)? Over the history of prejudice research, the goal of getting individuals to like one another has drawn attention away from these equally, if not more, important outcomes.

4.1.3. Acknowledging the complexities of harmony and conflict

The promotion of intergroup harmony has always been a cardinal objective of research on prejudice, and understandably so. Research on prejudice gathered impetus as a way of explaining the mass violence of World War II, and subsequent bloodshed throughout the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries did little to allay social scientists' concerns about “the toll in death, suffering and displacement caused by large-scale conflicts caused by groups defined by ethnicity, nationality, religion or other social identities” (Eidelson & Eidelson Reference Eidelson and Eidelson2003, p. 183). In the face of such events, the promotion of harmonious relations became an unquestioned moral imperative for many researchers.

However, the relationship among intergroup harmony, conflict, and social change is more complex than it first appears. On the one hand, harmony has a negative face, which our article has revealed. To borrow Jost et al.'s (Reference Jost, Banaji and Nosek2004) terminology, it carries insidious, often unacknowledged, “system-justifying” consequences. Seemingly tolerant and inclusive intergroup attitudes not only coexist with gross injustices, but also they can serve as a mechanism through which they are reproduced. On the other hand, if the unquestioned acceptance of intergroup harmony as an “absolute good” is simplistic, then so is the unquestioned rejection of intergroup conflict as an “absolute bad.” Unlike harmony, whose meaning is often taken for granted by social scientists, conflict has been intensely scrutinized and condemned as a social problem. By implication, the diffusion of intergroup tensions has become the cardinal principle of prejudice reduction interventions. Whatever other contributions it has made, this approach has entrenched the assumption that conflict between groups is inherently pathological, disconnected from human rationality, and without social value. It has quietly obscured the possibility that such conflict is also “a normal and perfectly healthy aspect of the political process that is social life.” (Oakes Reference Oakes, Brown and Gaertner2001, p. 16). Its psychological correlates of anger, strong social identification, recognition of status disparities, and sense of injustice do not sit easily with a prejudice reduction model of social change; however, in fueling collective resistance, conflict may improve intergroup relations in a structural and institutional sense.