In a field full of slippery constructs, willpower may be one of the most slippery. It has never been clear what will means, or whether it even exists, and its derivative – willpower – is perhaps even less precisely defined. Thus, as Ainslie notes, willpower has come to mean different things to different people. From here, Ainslie suggests that willpower is not unitary but instead takes two major forms, which he calls “resolve” and “suppression.” He sees these distinctions as more or less self-evident, although he makes it clear that up to this point, his exclusive focus as a scholar has been on the former. He then suggests that although willpower sounds effortful, not all forms of willpower are equally effortful.

From our perspective, Ainslie is right to be concerned but has started in the wrong place and has not gone far enough. If one wishes to make the case for heterogeneity – and we share Ainslie's wish to do just that – we think a better starting point is self-control, which we define as the “self-initiated regulation of conflicting impulses in the service of enduringly valued goals” (Duckworth, Gendler, & Gross, Reference Duckworth, Gendler and Gross2016, p. 35). We prefer self-control as an object of scientific inquiry because, in our view, willpower is hopelessly polysemous and thus, for all its popularity, not amenable to cumulative science.

Our definition of self-control embraces Ainslie's conception of multiple, competing motives that must be regulated when they come into conflict. Working from this definition, we first sketch the process by which impulses of any kind are generated, and then use this sketch to consider how conflicts between mutually exclusive impulses can be adjudicated. We refer to our approach as the process model of self-control (Duckworth et al., Reference Duckworth, Gendler and Gross2016).

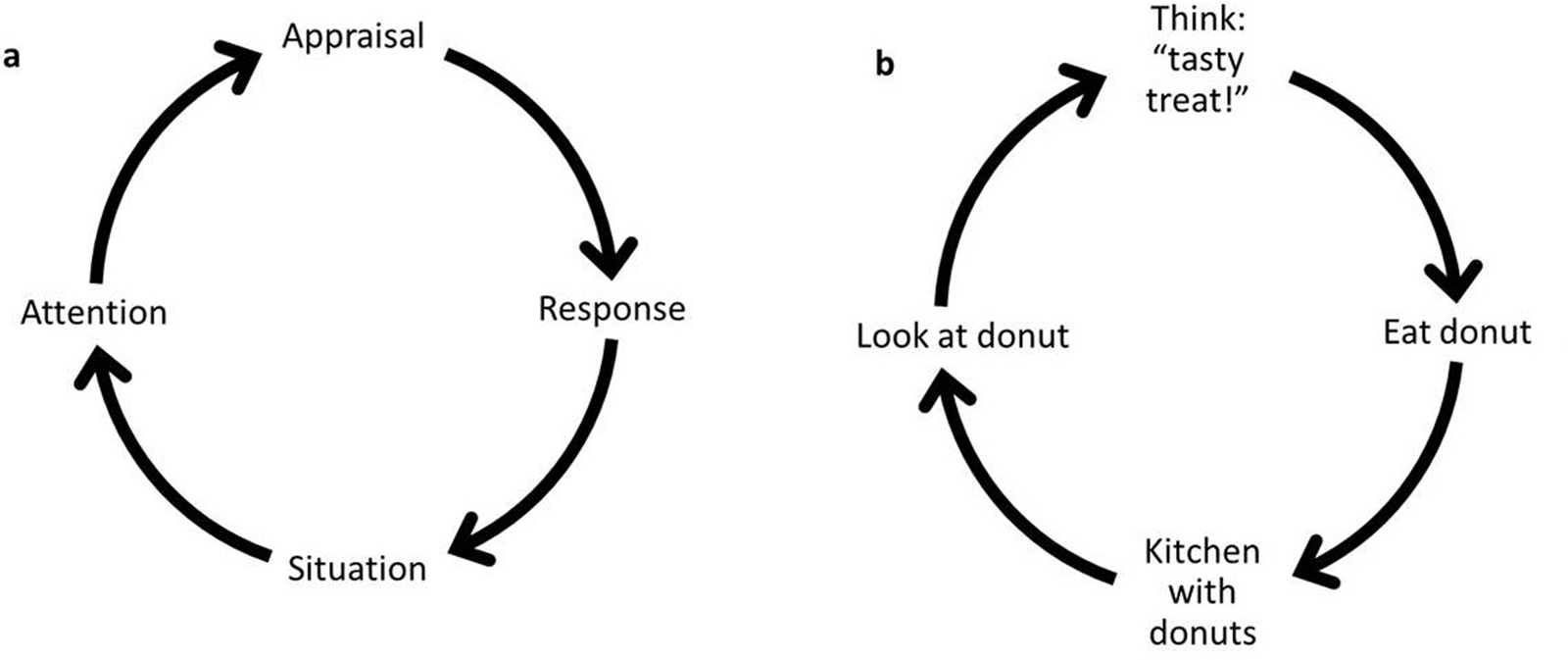

Figure 1 illustrates the recursive process by which impulses – whether they are good for us in the long run or not – are generated. To begin, an impulse arises when a particular situation in the world is attended to and then appraised in a way that is relevant to currently active goals. For instance, we may walk into the kitchen (situation), notice a box of donuts on the kitchen counter (attention), think how delicious they would taste (appraisal), and then feel an urge to open the box lid (response). Now, our situation has changed. We are in the kitchen with an open box of donuts, which leads us to notice the scent of cinnamon and sugar, and so on.

Figure 1. Process model of self-control. Note. Impulses develop in an iterative cycle, beginning with the situation, then attention is directed to select features of the situation, then subjective appraisals are made of these situational features, leading to a response tendency that, when sufficiently strong, is enacted, thereby changing the situation anew. Figure reproduced with permission from Duckworth et al. (Reference Duckworth, Gendler and Gross2016).

Having articulated the stages through which impulses are generated, we can now consider how competing impulses can be regulated. In Figure 2, we distinguish five points at which an impulse might be modified: situation selection (electing to be in one situation vs. another), situation modification (altering an existing situation), attentional deployment (redirecting one's attention), cognitive change (altering the way a situation is mentally represented), and response modulation (trying to directly adjust the strength of an impulse).

Figure 2. Self-control strategies. Note. Self-control strategies target distinct stages in the generation of impulses. Situational self-control strategies (shown in the light, hatched boxes) precede cognitive strategies (shown in the dark, solid boxes). Figure reproduced with permission from Duckworth et al. (Reference Duckworth, Gendler and Gross2016).

Self-control entails weakening the less-valued impulse, strengthening the more-valued impulse, or both. To illustrate, in Figure 3a, we lay out how the impulse to eat a donut might be weakened, and in Figure 3b, how the impulse to eat a banana instead might be strengthened. Self-control strategies need not be mutually exclusive – individuals often engage in polyregulation, deploying more than one strategy at once (Ford, Gross, & Gruber, Reference Ford, Gross and Gruber2019).

Figure 3. Examples of self-control strategies. Note. Self-control strategies can (a) weaken a pleasure-oriented impulse or (b) strengthen a health-oriented impulse. Figure reproduced with permission from Duckworth et al. (Reference Duckworth, Gendler and Gross2016).

From our perspective, the process model of self-control offers several advantages over willpower: (1) it avoids the pitfalls associated with trying to clarify a construct as messy as willpower by focusing instead on the more sharply defined concept of self-control; (2) it links how impulses are generated to how they might be regulated, providing a conceptual framework for making principled distinctions among self-control strategies; (3) it allows for more useful distinctions than Ainslie does (note that what Ainslie calls “resolve” may be considered a special case of cognitive change, whereas his view of “suppression” may be considered a mix of attentional deployment and cognitive change); (4) it articulates a continuum of effort, with strategies deployed earlier (e.g., situation selection) generally more efficient than strategies deployed later (e.g., response modulation) within a cycle of impulse generation; (5) it can be extended to explain the benefits of planning, personal rules, and habits; and (6) it suggests that self-control is a special case of interacting valuation systems.

Finally, the process model offers one additional affordance. Although developed in the context of self-control, this scheme does not require the individual to initiate the regulation of impulses. This structure opens up the possibility of expanding beyond self-control (Angela regulates Angela's impulse in the service of Angela's long-term goal) to extrinsic regulation (James regulates Angela's impulse in the service of Angela's long-term goal, or the government regulates Angela's impulse in the service of Angela's long-term goal) (Duckworth & Gross, Reference Duckworth and Gross2020; Duckworth, Milkman, & Laibson, Reference Duckworth, Milkman and Laibson2018). In so doing, we can connect the psychological science of self-control to behavioral economics research on “nudges” and sociological perspectives on agency – deepening our appreciation of the multitude of contextual factors that influence whether what we do in the moment furthers or undermines our long-term well-being.

In a field full of slippery constructs, willpower may be one of the most slippery. It has never been clear what will means, or whether it even exists, and its derivative – willpower – is perhaps even less precisely defined. Thus, as Ainslie notes, willpower has come to mean different things to different people. From here, Ainslie suggests that willpower is not unitary but instead takes two major forms, which he calls “resolve” and “suppression.” He sees these distinctions as more or less self-evident, although he makes it clear that up to this point, his exclusive focus as a scholar has been on the former. He then suggests that although willpower sounds effortful, not all forms of willpower are equally effortful.

From our perspective, Ainslie is right to be concerned but has started in the wrong place and has not gone far enough. If one wishes to make the case for heterogeneity – and we share Ainslie's wish to do just that – we think a better starting point is self-control, which we define as the “self-initiated regulation of conflicting impulses in the service of enduringly valued goals” (Duckworth, Gendler, & Gross, Reference Duckworth, Gendler and Gross2016, p. 35). We prefer self-control as an object of scientific inquiry because, in our view, willpower is hopelessly polysemous and thus, for all its popularity, not amenable to cumulative science.

Our definition of self-control embraces Ainslie's conception of multiple, competing motives that must be regulated when they come into conflict. Working from this definition, we first sketch the process by which impulses of any kind are generated, and then use this sketch to consider how conflicts between mutually exclusive impulses can be adjudicated. We refer to our approach as the process model of self-control (Duckworth et al., Reference Duckworth, Gendler and Gross2016).

Figure 1 illustrates the recursive process by which impulses – whether they are good for us in the long run or not – are generated. To begin, an impulse arises when a particular situation in the world is attended to and then appraised in a way that is relevant to currently active goals. For instance, we may walk into the kitchen (situation), notice a box of donuts on the kitchen counter (attention), think how delicious they would taste (appraisal), and then feel an urge to open the box lid (response). Now, our situation has changed. We are in the kitchen with an open box of donuts, which leads us to notice the scent of cinnamon and sugar, and so on.

Figure 1. Process model of self-control. Note. Impulses develop in an iterative cycle, beginning with the situation, then attention is directed to select features of the situation, then subjective appraisals are made of these situational features, leading to a response tendency that, when sufficiently strong, is enacted, thereby changing the situation anew. Figure reproduced with permission from Duckworth et al. (Reference Duckworth, Gendler and Gross2016).

Having articulated the stages through which impulses are generated, we can now consider how competing impulses can be regulated. In Figure 2, we distinguish five points at which an impulse might be modified: situation selection (electing to be in one situation vs. another), situation modification (altering an existing situation), attentional deployment (redirecting one's attention), cognitive change (altering the way a situation is mentally represented), and response modulation (trying to directly adjust the strength of an impulse).

Figure 2. Self-control strategies. Note. Self-control strategies target distinct stages in the generation of impulses. Situational self-control strategies (shown in the light, hatched boxes) precede cognitive strategies (shown in the dark, solid boxes). Figure reproduced with permission from Duckworth et al. (Reference Duckworth, Gendler and Gross2016).

Self-control entails weakening the less-valued impulse, strengthening the more-valued impulse, or both. To illustrate, in Figure 3a, we lay out how the impulse to eat a donut might be weakened, and in Figure 3b, how the impulse to eat a banana instead might be strengthened. Self-control strategies need not be mutually exclusive – individuals often engage in polyregulation, deploying more than one strategy at once (Ford, Gross, & Gruber, Reference Ford, Gross and Gruber2019).

Figure 3. Examples of self-control strategies. Note. Self-control strategies can (a) weaken a pleasure-oriented impulse or (b) strengthen a health-oriented impulse. Figure reproduced with permission from Duckworth et al. (Reference Duckworth, Gendler and Gross2016).

From our perspective, the process model of self-control offers several advantages over willpower: (1) it avoids the pitfalls associated with trying to clarify a construct as messy as willpower by focusing instead on the more sharply defined concept of self-control; (2) it links how impulses are generated to how they might be regulated, providing a conceptual framework for making principled distinctions among self-control strategies; (3) it allows for more useful distinctions than Ainslie does (note that what Ainslie calls “resolve” may be considered a special case of cognitive change, whereas his view of “suppression” may be considered a mix of attentional deployment and cognitive change); (4) it articulates a continuum of effort, with strategies deployed earlier (e.g., situation selection) generally more efficient than strategies deployed later (e.g., response modulation) within a cycle of impulse generation; (5) it can be extended to explain the benefits of planning, personal rules, and habits; and (6) it suggests that self-control is a special case of interacting valuation systems.

Finally, the process model offers one additional affordance. Although developed in the context of self-control, this scheme does not require the individual to initiate the regulation of impulses. This structure opens up the possibility of expanding beyond self-control (Angela regulates Angela's impulse in the service of Angela's long-term goal) to extrinsic regulation (James regulates Angela's impulse in the service of Angela's long-term goal, or the government regulates Angela's impulse in the service of Angela's long-term goal) (Duckworth & Gross, Reference Duckworth and Gross2020; Duckworth, Milkman, & Laibson, Reference Duckworth, Milkman and Laibson2018). In so doing, we can connect the psychological science of self-control to behavioral economics research on “nudges” and sociological perspectives on agency – deepening our appreciation of the multitude of contextual factors that influence whether what we do in the moment furthers or undermines our long-term well-being.

Financial support

This paper was made possible by the Walton Family Foundation and the John Templeton Foundation.

Conflict of interest

None.