1. Introduction

Social conflict has been part and parcel of human history and exerts a range of effects that easily exceed imagination. Conflict is associated with the rise and fall of nations and large-scale migration flows, and interferes with individual life trajectories. Conflict destroys welfare and lives, creates collective imprints and out-group resentments that transcend generations, and can cause famine and the spreading of infectious disease. Conversely, conflict drives technological innovation, inspires art, and creates and destroys hierarchies. Indeed, throughout history, conflicts have revised established structures and divides, introduced new views and practices, and changed the social order of individuals and their groups.

Conflict can be about many things such as ownership, territorial access, status and respect, and what is right and wrong (e.g., Blattman & Miguel Reference Blattman and Miguel2010; Bornstein Reference Bornstein2003; De Dreu Reference De Dreu, Fiske, Gilbert and Lindzey2010; Deutsch Reference Deutsch1973; Gould Reference Gould1999; Rapoport Reference Rapoport1960; Schelling Reference Schelling1960). Sometimes, these conflicts are about something all parties want but that only some can have (Coombs & Avrunin Reference Coombs and Avrunin1988). Examples include politicians competing for the same senate seat, rivaling research laboratories claiming the patent ownership of a potentially lucrative technology, and superpowers seeking world hegemony. Alternatively, conflicts emerge because some parties want something that others try to prevent from happening (Durham Reference Durham1976; Miller Reference Miller2009; Pruitt & Rubin Reference Pruitt and Rubin1986). Examples include revisionist states seeking to capture their neighbor's territory, activist rebels fighting elitist powerholders, companies launching hostile take-over attempts, and terrorists attacking civilian and military targets.

Conflicts among nonhuman animals typically have such a structure of attack and defense (Boehm Reference Boehm2009; Reference Boehm2012; Dawkins & Krebs Reference Dawkins and Krebs1979; Sapolsky Reference Sapolsky2017; Wrangham Reference Wrangham2018). Human conflicts may be no different. In fact, more than two-thirds of the 2,000 militarized interstate disputes that emerged since the Congress of Vienna in 1816 involved a revisionist state and a non-revisionist state (De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Gross, Meder, Griffin, Prochazkova, Krikeb and Columbus2016a; Gochman & Maoz Reference Gochman and Maoz1984; Wright Reference Wright2014). Likewise, 68% of community disputes involved a challenger who desired a revision and a defender who protected the status quo (Ufkes et al. Reference Ufkes, Giebels, Otten and Van der Zee2014). Finally, people often perceive the other side as the threatening aggressor who leaves them no option but to aggressively defend themselves, a psychological bias often fueled by leader rhetoric (Chambers et al. Reference Chambers, Baron and Inman2006; Plous Reference Plous1985; Staub Reference Staub1996).

Although conflicts often have an attack-defense structure, theory and research have rarely made a clear distinction between attack and defense (Lopez Reference Lopez2017; Pruitt & Rubin Reference Pruitt and Rubin1986; Rusch Reference Rusch2014a; Reference Rusch2014b; Wrangham Reference Wrangham2018). We currently lack theory and research about the ways in which clashes between attackers and defenders evolve, about the neurocognitive mechanisms that scaffold attack and defense, and about the cultural institutions that groups use to attack their neighbors or to defend against enemy attacks. Accordingly, our aim here is to provide a framework of the structure, psychological adaptations, and institutional consequences of attacker-defender conflicts.

We proceed as follows. Section 2 presents a formal model of attack-defense conflict and identifies unique properties of games of attack and defense that are neither present in nor captured by canonical games of conflict that have dominated classic and contemporary conflict analysis and research. Section 3 maps these properties onto behavioral decision-making and delineates its underlying neurocognitive mechanisms. We show that psychological “biases” often viewed as a result of imperfect human cognitive architectures may be functional for either attack or defense. Section 4 considers games of attack and defense between groups of people. We argue that groups face greater difficulty motivating and coordinating a collective attack of out-groups than defending against outside enemies, and that an out-group attack requires distinctly different sociocultural mechanisms and institutional arrangements than in-group defense. Section 5 shows how games of attack and defense, both within and between groups, may have shaped human capacities for cooperation and aggression.

2. The structure of conflict

Mankind spends great amounts of energy on injuring others, and on protecting against injury.

— John Stuart Mill (Reference Mill1848, p. 147)The study of conflict incorporates a broad variety of conceptual and methodological tools, is strongly interdisciplinary, and encompasses multiple levels of analysis between individuals, groups of people, and (coalitions of) nation states (e.g., Blattman & Miguel Reference Blattman and Miguel2010; Bornstein Reference Bornstein2003; Cunningham et al. Reference Cunningham, Gleditsch and Salehyan2009; Gould Reference Gould1999; Humphreys & Weinstein Reference Humphreys and Weinstein2006; Pietrazewski Reference Pietrazewski2016; Rusch Reference Rusch2014a). At the same time, there is a growing consensus to view conflicts as situations in which individuals or groups cannot realize their preferred state when other individuals or groups realize their own preferred state (Coombs & Avrunin Reference Coombs and Avrunin1988; De Dreu Reference De Dreu, Fiske, Gilbert and Lindzey2010; Deutsch Reference Deutsch1973; Kelley & Thibaut Reference Kelley and Thibaut1978; Pruitt Reference Pruitt, Gilbert, Fiske and Lindzey1998; Schelling Reference Schelling1960). This conceptualization of conflict as incompatibility of interests is adopted here as well.

At the core of this unifying approach is behavioral game theory, which offers stylized models of conflict (e.g., Camerer Reference Camerer2003; Hirshleifer Reference Hirshleifer1988; Kagel & Roth Reference Kagel and Roth1995; Schelling Reference Schelling1960). Indeed, game theoretical models of conflict have been used extensively in the study of international tension and interstate warfare (Bacharach & Lawler Reference Bacharach and Lawler1981; Huth & Russett Reference Huth and Russett1984; Jervis Reference Jervis1978; Snyder & Diesing Reference Snyder and Diesing1977) to understand the group dynamics and cultural arrangements that create and fuel intergroup conflict (Abbink Reference Abbink, Garfinkel and Skaperdas2012; Bornstein Reference Bornstein2003; Colman Reference Colman2003; De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Balliet and Halevy2014; Lacomba et al. Reference Lacomba, Lagos, Reuben and van Winden2014), to investigate the neural networks and neuroendocrine pathways involved in cooperation and competition (Cikara & Van Bavel Reference Cikara and Van Bavel2014; Decety & Cowell Reference Decety and Cowell2014; De Dreu Reference De Dreu2012; Rilling & Sanfey Reference Rilling and Sanfey2011), and to model the evolution of human prosociality and aggression (Bowles & Gintis Reference Bowles and Gintis2011; Garcia et al. Reference Garcia, Van Veelen and Traulsen2014; Henrich & McElreath Reference Henrich and McElreath2003; Nowak Reference Nowak2006; Rusch Reference Rusch2014a; West et al. Reference West, Griffin and Gardner2007).

Almost invariably, these lines of inquiry rely on models of conflict in which opposing decision-makers compete for the same reason(s). Accordingly, these models are ill-suited to approach the attacker-defender conflicts between revisionist and non-revisionist states, rebels and elitist powerholders, terrorists and security officers, or progressives and traditionalists. In this section, we highlight the structural properties of attack-defense conflicts that set them apart from the canonical games of conflict that dominate classic and contemporary conflict analysis and research (for notable exceptions, see, e.g., Carter & Anderton Reference Carter and Anderton2001; Dresher Reference Dresher1962; Durham Reference Durham1976; Grossman & Kim Reference Grossman, Kim, Garfinkel and Skaperdas1996; Reference Grossman and Kim2002). These structural properties have critical implications for the incentives to engage in conflict or not, for the predictions about conflict expenditures, and for the psychological and institutional mechanisms underlying aggression or appeasement.

2.1. Conflict as incompatible interests

In its most basic form, game theory models conflict as two decision-makers (or “players”) each with two possible actions to choose from, with the action that maximizes one's personal gain prohibiting the counterpart from maximizing her own personal gain at the same time. Imagine, for example, two countries both seeking world hegemony and building up a nuclear arsenal to subordinate the other side and to protect themselves against the other side's possible aggression. Only one country can achieve world hegemony, and the other must lose (or both lose when the nuclear option is used). Or imagine two farmers trying to gain exclusive access to the same water source, or two scientists working on the same problem trying to publish their breakthrough first. Again, what is in each player's best interest is incompatible with what is in the other side's best interest, and each will achieve its preferred state – world hegemony, access to the water source, or claiming a scientific discovery – only when the other does not.

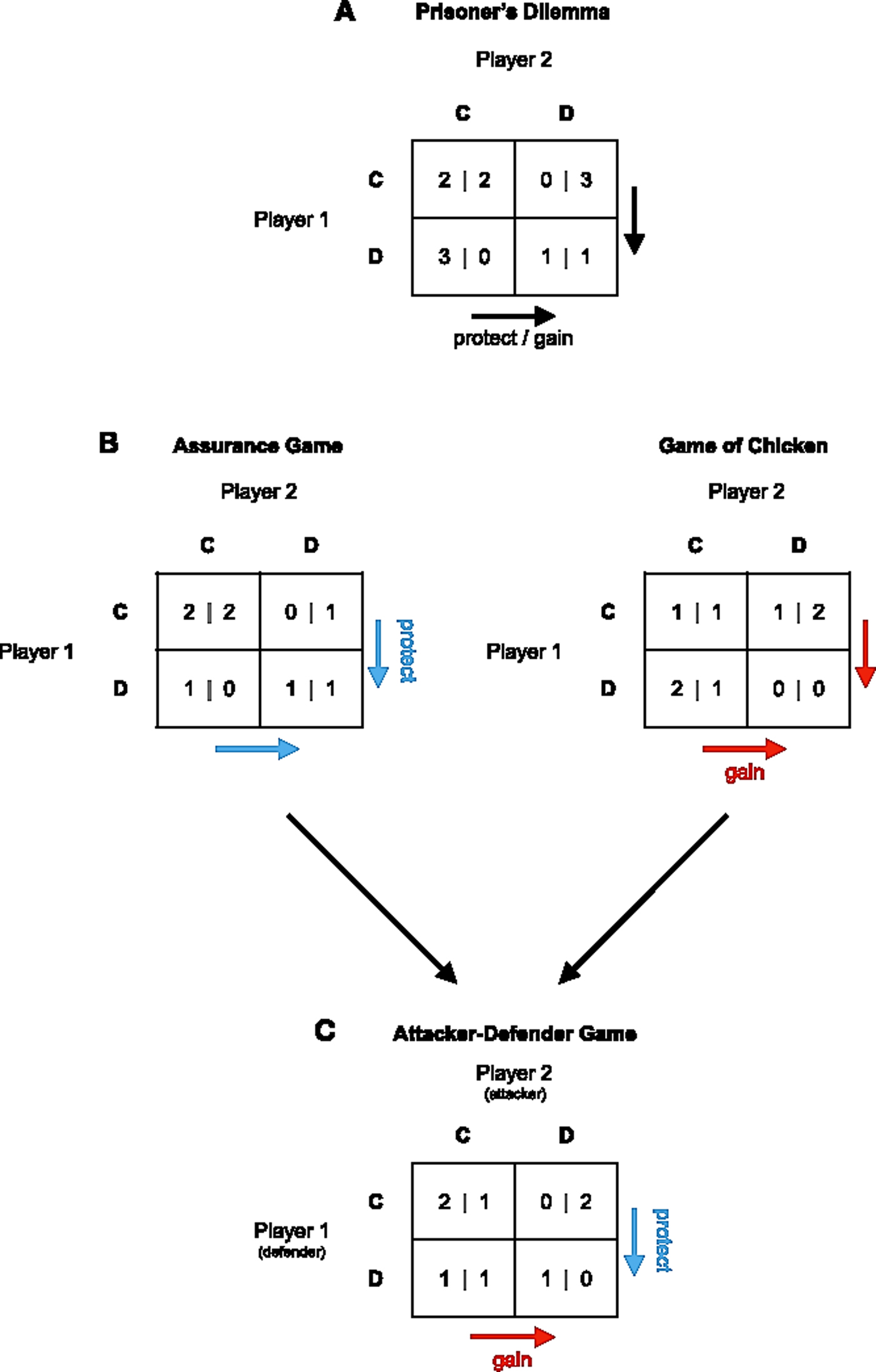

These and related situations of incompatible interests have been modeled with various games of strategy. In the classic Prisoner's Dilemma, for example, two players can choose between two possible actions labeled “cooperation” (C) and “defection” (D), as shown in Figure 1A. Each player can obtain one of four possible outcomes, depending on the action choice by the other side and oneself. Mutual cooperation (CC) is more beneficial to both players than mutual defection (DD). However, mutual cooperation is unstable because each player can increase its gain by playing defection when the other player cooperates, and vice versa. Player 1 thus prefers DC over CC, whereas player 2 prefers CD over CC. Players cannot both realize their preferred outcome at the same time.

Figure 1. Games of conflict. (A) In Prisoner's Dilemma, both parties would mutually benefit from playing CC as opposed to DD. Playing D, however, can yield the highest gain. Further, playing C is risky, as it does not protect against exploitation. (B) In the Assurance Game, D protects against obtaining the worst outcome and guarantees a certain payoff. This situation reverses in the Game of Chicken, in which playing D can yield the highest gain, but does not protect against the risk of obtaining the worst outcome. (C) Combining the payoffs of player 1 in the Assurance Game with the payoffs of player 2 in the Game of Chicken leads to the Attacker-Defender Game. By playing D, player 1 can protect a loss with certainty (defend), while player 2 can gamble for a higher gain (attack).

Defection in the Prisoner's Dilemma is psychologically tempting for two reasons: First, defection can maximize personal gain. Second, defection protects against exploitation attempts of the other party (Coombs Reference Coombs1973). These two reasons for choosing defection rather than cooperation are disentangled in two other well-known games of strategy, the Game of Chicken and the Stag Hunt or Assurance Game (see Fig. 1B; Camerer Reference Camerer2003; Kagel & Roth Reference Kagel and Roth1995). In the Game of Chicken, choosing D can maximize personal gain if the other side cooperates. Thus, choosing D does not protect against loss, as in the Prisoner's Dilemma, but can increase personal gain compared with mutual cooperation (CC). This captures the conflict between two farmers who desire to move their cattle into new territory that can feed only one farmer's herd. Conversely, in the Assurance Game, choosing D cannot maximize personal gain but can protect against the worst outcome that is obtained when choosing C, if the other party chooses D. This captures a situation in which players do not expect their counterpart to cooperate (viz., distrust) and act preemptively to protect against exploitation (Abbink & de Haan Reference Abbink and de Haan2014; Böhm et al. Reference Böhm, Rusch and Güreck2016; Halevy Reference Halevy2016; Simunovic et al. Reference Simunovic, Mifune and Yamagishi2013).Footnote 1

Crucially, these three basic games have in common that they are symmetric. Switching positions (player A becomes B, and vice versa) should not change their choice of strategy, nor the reasons for choosing that strategy. As such, opposing players have exactly the same structural motives for choosing C or D – gamble for maximizing personal gain, or avoid any risk and protect against loss and exploitation (Messick & Thorngate Reference Messick and Thorngate1967; Pruitt Reference Pruitt1967; Pruitt & Kimmel Reference Pruitt and Kimmel1977). As such, symmetric games fail to capture the conflicts in which some players choose defection to maximize personal reward and others choose defection to prevent loss and exploitation. In such conflicts, switching positions (A becomes B, and vice versa) does not necessarily change their action but certainly the reason for preferring a certain action. For example, a rogue state contesting a superpower's world hegemony competes to increase its territory and its position in the global world order, whereas the superpower competes to protect its territory and to defend its top-ranking status position. When the leaders of both countries change positions, they may still decide to compete but now for diametrically opposite reasons.

2.2. Modeling the game of attack and defense

The distinct psychological reasons to compete – maximize reward versus protect against exploitation – separate players into attackers and defenders. In such conflicts, attackers have a preference-ordering similar to that of the Game of Chicken, whereas the defenders' preference-ordering is that of the Assurance Game. An ordinal variant of this game of attack and defense, which we call the Attacker–Defender Game (AD-G), is shown in Figure 1C.

Two features of the AD-G set it apart from symmetric games of conflict. First and foremost, in the AD-G, CC is more attractive to defenders than any other configuration of outcomes, whereas to attackers it is less attractive than the victory achieved when choosing attack (D) while the defender chooses to not defend (C). This fits the intuition that conflict may be triggered by relative deprivation and inequity aversion (see sect. 2.3). Thus, defenders benefit from peaceful interactions and compete to protect against exploitation, whereas attackers have an incentive to compete to maximize their personal reward. Relatedly, in the AD-G, collision (DD) is less costly to defenders than to attackers, which fits the defender's “home territory advantage”; whereas attackers need to overcome their rivals' defense, defenders only need to keep their attackers at arm's length (e.g., Galanter et al. Reference Galanter, Silva, Rowell and Rychtářc2017).Footnote 2

Second, in AD-G, defenders prefer C > D when their attackers play C: Unilateral defense is costly. However, when defenders play C and thus are defenseless, attackers prefer D > C. Game-theoretically, the one-shot AD-G thus lacks a dominant strategy for both the attacker and defender and has its Nash-equilibrium in mixed strategies.Footnote 3 This is also the case in some symmetric conflict games, such as the Game of Chicken, where defection maximizes reward when the counterpart cooperates and cooperation maximizes reward when the counterpart defects. However, in contrast to symmetric games with a mixed-strategy equilibrium, games of attack and defense have their equilibrium in an asymmetric matching-mismatching of strategies. Whereas it is in the defender's best interest to match its attacker's strategy (outcome DD or CC), it is in the attacker's best interest to mismatch its defender's strategy (outcome DC or CD) (e.g., Goeree et al. Reference Goeree, Holt and Palfrey2003). As an example, consider the Hide-and-Seek Game between a terrorist who seeks a target area where security officers will not look (mismatching strategy) and security officers surveilling areas where they think the terrorist is most likely to attack (a matching strategy) (Bar-Hillel Reference Bar-Hillel2015; Flood Reference Flood1972; Steele et al. Reference Steele, Halkin, Smallwood, McKenna, Mitsopoulos and Beam2008; Von Neumann Reference Von Neumann, Kuhn and Tucker1953; see also sect. 3.2 on social signaling).

Attacker-defender conflicts are often about an attacker's desire to improve on the status quo and a defender's desire to maintain and protect the status quo. The status quo defines a reference point (Kahneman et al. Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler1991; Samuelson & Zeckhauser Reference Samuelson and Zeckhauser1988), with attackers trying to gain relative to the status quo and defenders trying to not lose relative to the status quo. To capture this, the AD-G can be transformed to a contest game (De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Scholte, Van Winden and Ridderinkhof2015), in which one player (henceforth, attacker) has to decide how much to invest in attack (x) out of a given endowment e (with 0 ≤ x ≤ e), while the other player (henceforth, defender) simultaneously decides how much to invest in defense (y) out of an equal endowment e (with 0 ≤ y ≤ e). If x > y, the attacker wins and obtains all of e–y. Added to the remaining endowment e–x, this leads to a total payoff for the attacker of 2e–x–y, while the defender is left with 0. If x ≤ y, the attacker appropriates nothing and the defender “survives,” leading to a payoff of e–x for the attacker and e–y for the defender. This game is formally equivalent to a contest with a contest success function f = x m/(x m + y m), where f is the probability that the attacker wins, with m = ∞ for x ≠ y, and with the modification that f = 0 if y = x (Dechenaux et al. Reference Dechenaux, Kovenock and Sheremeta2015; Grossman & Kim Reference Grossman and Kim2002; Rusch & Gavrilets Reference Rusch and Gavrilets2019; Tullock Reference Tullock, Buchanan, Tollison and Tullock1980).Footnote 4

2.3. Summary and implications

Conflict theory and analysis mostly neglected models of attack and defense that emerge when states aggress their non-revisionist neighbors, when raiding parties attack adjacent communities, or when viruses battle with a host's immune system. Here we modeled such asymmetric conflicts as AD-G with a binary or continuous action space (see also Notes 2 and 4). The AD-G provides a stylized game-theoretic framework to formally analyze attacker's and defender's strategic choices, and to observe attack and defense in behavioral experiments.

Several potential extensions to our analysis are worth noting. First, our modeling of attacker-defender conflicts is limited to two-player conflicts and excluded multiplayer disputes in which more than two (groups of) individuals oppose each other. Multiplayer conflicts have an extra dimension of complexity because alliances among subsets of players can be forged that turn former foes into new friends and that change the power relations and payoff functions between rivaling factions. Second, as in any game of strategy, power is often asymmetrically distributed between antagonists (Bornstein & Weisel Reference Bornstein and Weisel2010; Choi et al. Reference Choi, Chowdhury and Kim2016; Durham et al. Reference Durham, Hirshleifer and Smith1998; Hirshleifer Reference Hirshleifer1991). Asymmetry in power can be modeled by inequality in resource endowments in the AD-G contest game and can dramatically change the motivation to attack or to defend. Finally, in dynamic settings, the position of attack and defense may change across time, depending on resources and conflict success, and repeated interactions can give rise to a shadow of the future that may increase the prevalence of conflict rather than promote peace (McBride & Skaperdas Reference McBride and Skaperdas2014; Skaperdas & Syropoulos Reference Skaperdas and Syropoulos1996).

Our analysis, thus far, assumed strategic choices to be driven by the motivation to maximize gain (among attackers) and to avoid loss (among defenders). Humans are noteworthy for making social comparisons and strategic choices in conflict are also conditioned by the anticipated gain and loss relative to one's antagonist. For example, a wealth of research has shown how relative deprivation – having less than one's counterpart – drives strategic choices away from mutual cooperation and peace and toward conflict and competition (e.g., Halevy et al. Reference Halevy, Chou, Cohen and Bornstein2010). Such social comparisons may differentially influence attackers and defenders (Chowdhury et al. Reference Chowdhury, Jeon and Ramalingam2018). For example, in the ordinal variant of the AD-G given in Figure 1C, both CC and DD would provide the attacker with less than the defender. Because of inequity aversion (Fehr & Schmidt Reference Fehr and Schmidt1999), attackers may be indifferent between CC and DD and prefer DC to CD. Conversely, attackers may anticipate guilt when their defection exploits a cooperating defender, and guilt aversion may inhibit the impulse to attack (Battigalli & Dufwenberg Reference Battigalli and Dufwenberg2009; Dufwenberg et al. Reference Dufwenberg, Gächter and Hennig-Schmidt2011; Ellingsen et al. Reference Ellingsen, Johannesson, Tjotta and Torsvik2010). To give one final example: Players sometimes value collective rather than personal outcomes (Bolton & Ockenfels Reference Bolton and Ockenfels2000; De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Weingart and Kwon2000; Engelmann & Strobel Reference Engelmann and Strobel2004; Van Lange Reference Van Lange1999), making cooperation rather than defection the preferred strategy among both attackers and defenders. In short, game theoretical analyses can provide a powerful tool to understand the structure of conflict, while behavioral experiments and psychological theory are needed to understand how people perceive, adapt, and react to these conflict structures. We explore this in the next two sections.

3. Psychological functions for attack and defense

The rabbit runs faster than the fox, because the rabbit is running for his life while the fox is only running for his dinner.

— Richard Dawkins & John R. Krebs (Reference Dawkins and Krebs1979, p. 493)Our model of attack-defense conflicts reveals structural properties that set them apart from symmetric games of conflict and that may have significant implications for conflict behavior and its underlying neurobiological and cognitive processes. In this section, we first review recent studies investigating the behavioral decisions attackers and defenders take. We then link these behavioral patterns for attack and defense to extant findings in neurobiological and psychological research regarding the neural networks, cognitive processes, and motivational biases related to cooperation and competition (Bazerman et al. Reference Bazerman, Curhan, Moore and Valley2000; Carnevale & Pruitt Reference Carnevale and Pruitt1992; De Dreu & Carnevale Reference De Dreu and Carnevale2003). In particular, we focus on neural networks involved in reward processing and threat detection (Molenberghs Reference Molenberghs2013; Rilling & Sanfey Reference Rilling and Sanfey2011), on literature linking aggressive hostility to overconfidence and biased perceptions of the rival's hostility (Ross & Ward Reference Ross and Ward1995), and to feelings of superiority and tendencies to dehumanize opponents (Atran & Ginges Reference Atran and Ginges2012; Leyens et al. Reference Leyens, Demoulin, Vaes, Gaunt and Paladino2007).

3.1. Behavioral approach–avoidance in attack–defense conflicts

In general, people are loss averse; losses are more painful than commensurate gains are pleasurable (Kahneman et al. Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler1991; Kahneman & Tversky Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979; Reference Kahneman and Tversky1984), and people compete in prisoners' dilemmas more when their outcomes are framed as losses rather than gains (Andreoni Reference Andreoni1995; Brewer & Kramer Reference Brewer and Kramer1986; De Dreu & McCusker Reference De Dreu and McCusker1997; McCusker & Carnevale Reference McCusker and Carnevale1995; Sonnemans et al. Reference Sonnemans, Schram and Offerman1998). Likewise, negotiators demand more and concede less when they focus on what they lose relative to their level of aspiration, rather than on what they gain relative to some rock-bottom resistance point (Bottom & Studt Reference Bottom and Studt1993; De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Carnevale, Emans and Van de Vliert1994; Kuhberger Reference Kuhberger1998).

The principle of loss aversion implies that attackers should compete less intensely than defenders (Chowdhury et al. Reference Chowdhury, Jeon and Ramalingam2018). Indeed, negotiation studies show that individuals who challenge the status quo (viz., attackers) engage in less domineering behavior, use punitive tactics less frequently, and are less successful than their counterpart who aims to maintain the status quo (viz., defenders) (De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Kluwer and Nauta2008; Ford & Blegen Reference Ford and Blegen1992; Kteily et al. Reference Kteily, Saguy, Sidanus and Taylor2013). Furthermore, experiments using the AD-G contest game, outlined previously, show that attackers invested less than defenders (Fig. 2A; F= 4.14, p= 0.044) and less often decided to invest in attack than defenders decided to invest in defense (Fig. 2B; F= 18.97, p= 0.001; De Dreu & Giffin Reference De Dreu and Giffin2018; De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Scholte, Van Winden and Ridderinkhof2015; Reference De Dreu and Giffin2018). However, when investing, attackers and defenders used the same force; they invested about the same amount in attack and defense (Fig. 2C; F< 1).

Figure 2. Behavioral strategies for individual-level attack and defense. Results from the aggregate of three incentivized experiments in which participants made 30–60 investment decisions in the role of attacker or defender, each time matched with a new partner. Shown are means ± SE, with N = 85 attackers and 85 defenders. (A) Overall investment (out of an endowment of e = 10). (B) Frequency of peaceful actions (no investment out of 30 trials). (C) Force of investments. (D) Time taken to decide.

Reward seeking has been linked to the neurobiological system of behavioral activation and approach, and the aversion of loss and punishment to the neurobiological system of behavioral inhibition and avoidance (Albert et al. Reference Albert, Walsh and Jonik1993; Gray Reference Gray1990). Conceptually, the behavioral activation system is triggered when the organism receives cues signaling rewards and controls actions that are regulating approach. Behavioral activation associates with positive emotions, such as excitement, hope, and optimism, in response to reward signals. It is modulated by the mesolimbic dopaminergic system and steroid hormones like testosterone (Ashby et al. Reference Ashby, Isen and Turken1999; Boot et al. Reference Boot, Baas, Van Gaal, Cools and De Dreu2017; Depue & Collins Reference Depue and Collins1999; Eisenegger et al. Reference Eisenegger, Haushofer and Fehr2011; Harmon-Jones & Sigelman Reference Harmon-Jones and Sigelman2001; Sapolsky Reference Sapolsky2005; Reference Sapolsky2017). Conversely, the behavioral inhibition system is triggered in response to anxiety-relevant cues and controls actions aimed at avoiding such negative and unpleasant events (Carver & White Reference Carver and White1994; Elliot & Church Reference Elliot and Church1997; Gray Reference Gray1990). It associates with negative emotions such as fear, disgust and resentment, and, in the case of survival, relief.Footnote 5 Behavioral inhibition is modulated by the serotonergic pathway and stress-regulating hormones such as cortisol (Montoya et al. Reference Montoya, Terburg, Bos and van Honk2012; Nelson & Trainor Reference Nelson and Trainor2007; Roskes et al. Reference Roskes, Elliot and De Dreu2014; Sapolsky et al. Reference Sapolsky, Romero and Munck2000).

A first hypothesis emerging from this neuropsychological work is that attack and defense recruit distinct biobehavioral systems. In theory, attack should be associated with the release of the steroid hormone testosterone, mediated by the mesolimbic dopaminergic system, and activation in neural circuitries involved in the processing of rewards, such as the ventral striatum and the nucleus caudate. Conversely, defense should be associated with the release of cortisol and the recruitment of neural circuitries involved in threat detection and risk-avoidance such as the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the insula.Footnote 6

A second hypothesis emerging from this work is that, with all else equal, attackers are disproportionally less successful than defenders. People invest less in attack than in defense, and the motivation to increase reward is weaker than the drive to avoid loss and defeat (Kahneman & Tversky Reference Kahneman and Tversky1984; see also sect. 3.3). Indeed, a negotiated settlement typically favors defenders rather than attackers (De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Kluwer and Nauta2008), and our experimental results on attacker-defender contests showed that, defenders survived 66.4% of the contests (averaged over 60 one-shot rounds). A similar pattern emerges from archival analyses. When we analyzed success rates in the almost 1,500 militarized disputes between revisionist and non-revisionist nation states documented in the Correlates of War project (Gochman & Maoz Reference Gochman and Maoz1984; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Bremer and Singer1996; Wright Reference Wright2014), we found that only 25% were settled in favor of the revisionist state. Likewise, hostile takeover attempts in industry have a success rate less than 40% (De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Gross, Meder, Griffin, Prochazkova, Krikeb and Columbus2016a). In short, attackers compete less intensely than defenders and have difficulty winning the conflict.

3.2. (Mis)Matching, deception, and social signaling

As discussed in section 2, a key property of asymmetric attack-defense conflicts is what we referred to as asymmetric matching-mismatching of strategies; attackers benefit from mismatching their defenders' level of competitiveness, whereas defenders should match their attackers' competitiveness. Studies of marital conflict regarding household chores and child care have documented a so-called demand-withdrawal pattern in which one spouse demands change in the other, who matches the intensity of the demand for change with an equally or more intense tendency to avoid interaction and discussion of the conflict issues (Kluwer et al. Reference Kluwer, Heesink and Van de Vliert1997; Vogel & Karney Reference Vogel and Karney2002; see also Mikolic et al. Reference Mikolic, Parker and Pruitt1997). Behavioral experiments provide further support for this asymmetric matching-mismatching property. Specifically, we examined asymmetric matching-mismatching of strategies in 35 dyadic interactions across 40 rounds of Attacker-Defender contests. (For details on methods and materials, see De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Kret and Sligte2016b.) Consistent with the principle of loss aversion, we, again, found that defenders invested more than attackers (and both invested less at later rounds; Fig. 3A). We then calculated for attackers (defenders) the average investment of their opponent over the last three rounds and regressed investments in attack (defense) on this historical level of defense (attack). As shown in Figure 3B, attackers conditioned their behavior on their defenders' average investment: They attacked more when historical defense was low rather than high. And the more they engaged in such strategic forecasting, the more successful they were. Defenders, in contrast, invested more the higher their attackers' historical level of attack.

Figure 3. Strategic track-and-attack behavior. Results from an incentivized experiment in which participants made 40 investment decisions in the role of attacker and 40 investments as defender. In each 40-trial block, they were matched to the same partner and on each trial received full feedback. (A) Defenders (blue) invest more than attackers (red) on average (shown are means ± SE, with N = 35 attackers and 35 defenders). (B) Attackers are more successful when they condition attack on defenders' past behavior. The upper panel shows the distribution of regression weights for defenders' past investments (over the last three rounds) predicting attackers' expenditure on conflict. Negative values indicate larger attack expenditures when historic defense expenditure of the defender was low (and vice versa). Participants who systematically mismatch past defense expenditure are more successful (lower panel; final earnings on the y-axis; each dot represents one attacker).

That attackers mismatch their defenders' strategy and defenders match their attackers' (expected) level of hostility have important implications for social signaling and deception among attackers and defenders. Precisely because both attackers and defenders lack a dominant strategy, they should be motivated to predict their rivals' future strategy and, at the same time, try to hide their own true intentions from their rivals. In games of attack and defense, defenders are motivated to signal strength and commitment to deter their rivals from attacking, whereas attackers are motivated to signal nonaggressiveness to lure their defenders into a state of (illusionary) safety (Slantchev Reference Slantchev2010; Wheeler Reference Wheeler2009). To paraphrase Dawkins and Krebs (Reference Dawkins and Krebs1979): Whereas the rabbit runs faster and shows off its running strength with pride and confidence, the fox hides its true running capacity and instead feigns limpness.

3.3. Deliberate attack and spontaneous defense

Social signaling, attempts at deception, and accurate prediction of future events all require executive control and working memory. At the neuronal level, such a control network involves mainly prefrontal regions such as the inferior frontal gyrus, the dorsolateral and orbitofrontal gyrus, and the anterior cingulate (Aron et al. Reference Aron, Robbins and Poldrack2014; Braver Reference Braver2012; Dosenbach et al. Reference Dosenbach, Fair, Cohen, Schlaggar and Petersen2008; Posner & Rothbart Reference Posner and Rothbart2007). A wealth of neuroimaging studies related these neural regions to risk assessment, to the inhibition of habitual responses and impulses, and to strategic planning and deliberation during decision-making (e.g., Aron et al. Reference Aron, Fletcher, Bullmore, Sahakian and Robbins2003; Coan & Allen Reference Coan and Allen2003; Gross et al. Reference Gross, Emmerling, Vostroknutov and Sack2018; Knoch et al. Reference Knoch, Gianotti, Pascual-Leone, Treyer, Regard, Hohmann and Brugger2006a; Reference Knoch, Pascual, Meyer, Trever and Fehr2006b; Mehta & Beer Reference Mehta and Beer2010; Peterson et al. Reference Peterson, Gable and Harmon-Jones2008; Potegal Reference Potegal2012; Strang et al. Reference Strang, Gross, Schuhmann, Riedl, Weber and Sack2015).

Although both attack and defense may be conditioned by executive control, there is reason to believe that attack recruits top-down control more so than defense. First, the attacker's task to mismatch its defender's strategy may require more controlled flexibility in thinking than the defender's task to reactively match its attacker's level of competitiveness. Indeed, in attack-defense contest games, attackers invested with greater variability (Fig. 2A) took more time to make their decisions (Fig. 2D; F= 7.212, p= 0.008), and they reported greater fatigue following the contest than defenders (De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu and Giffin2018). Second, neuroimaging studies revealed greater activation in prefrontal control regions during attack than defense (De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Scholte, Van Winden and Ridderinkhof2015; Nelson & Trainor Reference Nelson and Trainor2007; Siegel et al. Reference Siegel, Roeling, Gregg and Kruk1999). Third, and, finally, there is evidence that reduced functionality of the control network affects attack more than defense. In one study, attackers and defenders performed cognitively taxing tasks prior to the contest. Results showed that, whereas defenders were not influenced by cognitive taxation, attackers made more aggressive investments when taxed rather than not (De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu and Giffin2018). In another study, the functionality of the right inferior frontal gyrus (rIFG) was manipulated using Theta Burst Stimulation (De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Kret and Sligte2016b). Again, defenders were not influenced and attackers more often invested when the rIFG was dysregulated, a pattern reminiscent of impulsive “high firing.” However, when rIFG functionality was upregulated, attackers tracked their defenders' history of play more systematically and attacked when defenders were predicted to be weak rather than strong.

The hypothesis that attack is more controlled than defense can offer an explanation for the mixed findings on the role of deliberation in public good provision games. Whereas some studies find that deliberation predicts more competition (e.g., Rand et al. Reference Rand, Greene and Nowak2012), others either find no relation between deliberation and competition, or find that deliberation predicts less competition (Bouwmeester et al. Reference Bouwmeester, Verkoeijen, Aczel, Barbosa, Begue, Branas-Garza, Chmura, Cornelissen, Dossing, Espin, Evans, Ferreira-Santos, Fiedler, Flegr, Ghaffari, Glockner, Goeschl, Guo, Hauser, Hernan-Gonzalez, Herrero, Horne, Houdek, Johannesson, Koppel, Kujal, Laine, Lohse, Martins, Mauro, Mischkowski, Mukherjee, Myrseth, Navarro-Martinez, Neal, Novakova, Paga, Paiva, Palfi, Piovesan, Rahal, Salomon, Srinivasan, Srivastava, Szaszi, Szollosi, Thor, Tinghog, Trueblood, Van Bavel, van 't Veer, Vastfjall, Warner, Wengstrom, Wills and Wollbrant2017). These studies invariably rely on symmetric games such as the N-person Prisoner's Dilemma, and the reason to compete can be to protect, to exploit, or a mixture of both motives. We propose that cognitive control and strategic deliberation play a stronger role when people compete for maximum reward than when they compete to avoid loss and exploitation (see also Simunovic et al. Reference Simunovic, Mifune and Yamagishi2013). Games of attack and defense that disentangle motives of protection and exploitation may be a useful model to further understand when and whether deliberation promotes competition, or instead has little bearing on it.

3.4. Overconfidence and hostile attributions

People have a tendency to engage in motivated reasoning, searching and processing information that supports their goals and desires, while avoiding and downplaying information that is inconvenient or otherwise unsupportive (Jervis Reference Jervis1978; Kahneman & Tversky Reference Kahneman, Tversky, Arrow, Mnookin, Ross, Tversky and Wilson1995; Ross & Ward Reference Ross and Ward1995). Conflict theory and research have identified two types of motivated reasoning that are particularly problematic for conflict resolution and dispute settlement: overconfidence and hostile attributions. Overconfidence refers to overestimating one's relative strength (Deutsch Reference Deutsch1973; Kahneman & Tversky Reference Kahneman, Tversky, Arrow, Mnookin, Ross, Tversky and Wilson1995). Hostile attribution bias refers to overestimating malicious intent in others (Kramer Reference Kramer1995; Pruitt & Rubin Reference Pruitt and Rubin1986). In game-theoretic terms, overconfidence may be operationalized as an overestimation of the probability that one's rival plays C rather than D, and hostile attribution as an underestimation of the probability that one's rival plays C rather than D.

Overconfidence plays an important role in conflict spiral theory (Bacharach & Lawler Reference Bacharach and Lawler1981; Deutsch Reference Deutsch1973). It argues that conflict escalates when and because (groups of) individuals believe they can win and emerge as the victor, for example, because they perceive themselves as relatively powerful. Indeed, overconfidence has been identified as a psychological precursor to conflicts such as the First World War (WWI), the Vietnam War, and the war in Iraq (Johnson Reference Johnson2004; Johnson & Fowler Reference Johnson and Fowler2011; Van Evera Reference Van Evera and Hanami2003). In experimental war games, people who are overconfident about their expectations of success are more likely to attack (Johnson Reference Johnson2006), and, in bargaining games, higher overconfidence is associated with more competition (Neale & Bazerman Reference Neale and Bazerman1985; Ten Velden et al. Reference Ten Velden, Beersma and De Dreu2011).

Overconfidence has been linked to neuronal processes that we identified as involved in attack, including positive affect (Ifcher & Zarghamee Reference Ifcher and Zarghamee2014; Koellinger & Treffers Reference Koellinger and Treffers2015), the release of testosterone (Johnson Reference Johnson2006), and activation in reward processing areas such as the bilateral striatum (Molenberghs et al. Reference Molenberghs, Trautwein, Bockler, Singer and Kanske2016). In that sense, overconfidence may be functional to attack; it enables people to compete under risk (de la Rosa Reference De la Rosa2011; Johnson & Fowler Reference Johnson and Fowler2011; Li et al. Reference Li, Szolnoski, Cong and Wang2016). Or, as noted by Kahneman and Tversky (Reference Kahneman, Tversky, Arrow, Mnookin, Ross, Tversky and Wilson1995, p. 49): “Confidence, short of complacency, is surely an asset once the contest begins. The hope of victory increases effort, commitment, and persistence in the face of difficulty or threat of failure, and thereby raises the chances of success.”

Defenders are unlikely to be overconfident. When confronted with potential attackers, overestimating one's strength and underestimating the rival's aggressive inclinations can be devastating. Rather, and perhaps therefore, defenders may be suspicious about their rivals' attack intentions, and their vigilant scrutiny may return biased impressions. In general, people more heavily weigh events that have negative, rather than positive implications for them (Pratto & John Reference Pratto and John1991; Taylor Reference Taylor1991). Also, person perception is influenced more by negative, rather than positive information (Fiske Reference Fiske1980). Automatic vigilance for negativity, such as for signals of the opponent's strength and malicious intent, may be accentuated during defense and elicit a hostile attribution bias (Kramer Reference Kramer1995; Pruitt & Rubin Reference Pruitt and Rubin1986; Waytz et al. Reference Waytz, Young and Ginges2014).

Hostile attribution bias can motivate (groups of) people to launch preemptive strikes aimed at neutralizing perceived threat and deterring one's rival from initiating attacks (Abbink & De Haan Reference Abbink and de Haan2014; Bacharach & Lawler Reference Bacharach and Lawler1981; Halevy Reference Halevy2016; Jervis Reference Jervis1978). Preemptive strikes can provoke retaliation and, as such, create in defenders a self-fulfilling prophecy of strikes and counterstrikes that are wasteful and mutually destructive (Halevy Reference Halevy2016; Simunovic et al. Reference Simunovic, Mifune and Yamagishi2013; Stott & Reicher Reference Stott and Reicher1998). In times of peace, on the other hand, hostile attribution bias could create a sustained and prolonged distrust in rivals that motivates investment in defense without apparent threats. There is some evidence that hostile attribution bias is indeed more prominent in defenders than attackers. In ideological conflicts between traditionalists who defend the status quo and revisionists who pursue change, traditionalists were more prone to polarize the two sides' attitudes and to attribute more extreme convictions to revisionists (Back Reference Back2013; Keltner & Robinson Reference Keltner and Robinson1997; Robinson & Keltner Reference Robinson and Keltner1996).

3.5. Feeling superior

People tend to believe that they are smarter, more moral, and less mean than others in general and their opponent, in particular. For example, experiments with professional negotiators, governmental decision-makers, and organizational consultants show that people view themselves as more constructive and as less destructive than their opponents (De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Evers, Beersma, Kluwer and Nauta2001), and such feelings of superiority are associated with increased hostility and an enhanced likelihood of future conflict (Babcock & Loewenstein Reference Babcock and Loewenstein1997; De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Nauta and Van de Vliert1995; see also Atran & Ginges Reference Atran and Ginges2012; Böhm et al. Reference Böhm, Thielmann and Hilbig2018; Ross & Ward Reference Ross and Ward1995).

Feeling superior may be especially functional for attack. Attack means that targets may be harmed, subordinated, and exploited. Imposing such negative externalities onto others is generally inhibited by empathy (Batson Reference Batson, Lindzey and Aronson1998; Decety & Cowell Reference Decety and Cowell2014; Lamm et al. Reference Lamm, Decety and Singer2011), guilt aversion (see sect. 2.3), and social norms such as the “do-no-harm principle” (Baron Reference Baron1994; Mill Reference Mill1848). In recent experiments, we found that attackers with stronger other-concern, indeed, invested less in attack than attackers with weaker other-concern. Investment in defense, on the other hand, was not conditioned by other-concern (De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu and Giffin2018). Feeling superior may reduce other-concern and provide the psychological justification for attacking others; it lowers the bar for using violence as a “means to an end” (Rai et al. Reference Rai, Valdesolo and Graham2017).

3.6. Summary and implications

The available research on competition in games of attack and defense permits three conclusions. First, attackers are less likely to compete than defenders and attackers invest fewer resources in fighting than defenders. Second, and possibly because of these behavioral asymmetries, attackers are disproportionately less successful than defenders. Across a range of settings, from laboratory experiments to private sector competition to interstate warfare, we observed an attacker success rate averaging around 30% (De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Gross, Meder, Griffin, Prochazkova, Krikeb and Columbus2016a). Thus, the prevention of exploitation is more likely than subordination. Third, we reviewed evidence that, consistent with the game structure of asymmetric conflicts, attackers are likely to mismatch the level of competition in their defenders, whereas defenders reactively match their attackers' competitiveness.

We have linked these distinct behavioral patterns to a range of neurocognitive functions underlying human attack and defense. We suggested that attack elicits behavioral approach and is associated more with prefrontal networks in the human brain than defensive behavior. Defense elicits behavioral avoidance and vigilant scanning for threat, and may be more automatic and intuitive than actions aimed at exploitation or profit maximization. Further, attacking and defending may markedly differ in overconfidence and risk-tolerance, hostile attributions, and feelings of superiority. Indeed, whereas overconfidence and feeling superior enable attack and may make people victorious against others, hostile attribution bias sustains defense and survival. Thus, one set of psychological biases may be the best response to the other set of psychological biases.

People possess both the dormant potential of overconfidence or dehumanization, on the one hand, and the potential for being vigilant and making hostile attributions, on the other hand. These abilities allow them to be both attacker and defender per situational requirements. At the same time, differences in psychological traits may differentially prepare people for these distinct roles in conflict. Taken to the extreme, the psychological characteristics of attackers merge into a psychological profile of people with high reward sensitivity, who are calculative and able to control impulses, are willing to accept risk, and lack empathy. Although these characteristics are usually temporary and triggered by contextual variation, when chronically activated, these characteristics merge into a profile reminiscent of trait psychopathy. Indeed, individuals labeled as psychopaths are impervious to the distress of others, lack fear of negative consequences of risky or criminal behavior, and demonstrate insensitivity to punishment (Book & Quinsey Reference Book and Quinsey2004; Hare & Neumann Reference Hare and Neumann2008; Meloy Reference Meloy and Gothard1995; Patrick Reference Patrick1994). Conversely, the psychological characteristics of defense merge into a profile of people with high punishment sensitivity and risk aversion, who act intuitively, and are prone to making hostile attributions. When chronically activated, this profile is reminiscent of trait paranoia, a mental condition characterized by thought processes that include beliefs of conspiracy concerning a perceived threat toward oneself (Green & Phillips Reference Green and Phillips2004; Saalveld et al. Reference Saalveld, Ramadan, Bell and Raihani2018). During the late 1960s, former U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson, for example, found himself engaged in an intense political struggle around the ongoing war in Vietnam, and often complained that he could not trust anybody. By the end of his administration, Johnson “had become convinced that he was engaged in a life-and-death struggle, in which not only his foreign policy, but also his presidency … were at stake” (Kramer Reference Kramer1995, p. 127).

In as much as psychopathy and paranoia are considered dysfunctional pathologies, psychological science long considered the neurocognitive operations that impede constructive conflict resolution as manifestations of self-centered motivation and imperfect cognitive architectures (Bazerman et al. Reference Bazerman, Curhan, Moore and Valley2000; De Dreu & Carnevale Reference De Dreu and Carnevale2003; Kahneman & Klein Reference Kahneman and Klein2009). An alternative perspective, put forward here, is to view biases and motivated reasoning as adaptations to recurrent problems that humans repeatedly faced in the past (Cosmides & Tooby Reference Cosmides, Tooby and Dupre1987; Fiedler Reference Fiedler2000; Gigerenzer & Brighton Reference Gigerenzer and Brighton2009; Haselton & Nettle Reference Haselton and Nettle2006; Tooby & Cosmides Reference Tooby and Cosmides1990). Key examples include overconfidence and feeling superior as adaptations to recurrent opportunities for attack, and hostile attributions as adaptations to recurrent threats of attack.

4. Intergroup games of attack and defense

Men, I now know, … fight for one another. Any man in combat, who lacks comrades who will fight for him, or for whom he is willing to die is … truly damned.

— William Manchester (Reference Manchester1980)Our framework, thus far, considered individual actors. To some extent, individual-level tendencies may operate also when groups of people engage in games of attack and defense. Indeed, entire groups can be overconfident about their attack being successful (Janis Reference Janis1972) and feel superior to their rivals (Atran & Ginges Reference Atran and Ginges2012; Haslam Reference Haslam2006; Leyens et al. Reference Leyens, Demoulin, Vaes, Gaunt and Paladino2007). Likewise, entire groups can be in a state of persistent vigilance, prone to hostile attribution biases, and collectively dehumanize their rivals (Boyer & Liénard Reference Boyer and Liénard2006). At the same time, however, intergroup conflicts have specific properties that are not present when unitary actors, such as individuals, engage in games of attack and defense. Specifically, in intergroup conflict, individuals within opposing groups have some discretion to contribute or not to the collective attack of out-groups or to join the collective defense of the in-group against an out-group threat (Bornstein Reference Bornstein2003; see also Humphreys & Weinstein Reference Humphreys and Weinstein2008; Radford et al. Reference Radford, Majolo and Aureli2016). Because individual contributions to the intergroup conflict are not a given, groups make use of institutions like cultural rituals and sanctioning systems to motivate their members to fight or compete. Here, we review evidence that the structural properties of intergroup games of attack and defense require attacker groups, more than defenders, to create institutional arrangements that motivate and coordinate individual contributions to intergroup conflict.

4.1. Games of attack and defense between groups

Behavioral game theory has modeled intergroup conflict as “team-level games” in which group behavior depends on individual level preferences for in-group cooperation and competition (Aaldering et al. Reference Aaldering, Ten Velden, Van Kleef and De Dreu2018; Abbink et al. Reference Abbink, Brandts, Herrmann and Orzen2010; Reference Abbink, Brandts, Hermann and Orzen2012; Böhm et al. Reference Böhm, Thielmann and Hilbig2018; Bornstein et al. Reference Bornstein, Budescu and Zamir1997; Reference Bornstein, Gneezy and Nagel2002; Reference Bornstein, Kugler and Zamir2005; De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Balliet and Halevy2014; Halevy et al. Reference Halevy, Bornstein and Sagiv2008; Rapoport & Bornstein Reference Rapoport and Bornstein1987). To illustrate, consider the team-level game of attack and defense between two three-person groups shown in Table 1. The group-level payoff matrix is based on the preference ordering in the Intergroup Chicken Dilemma (to model the attacker group's interests) and the Intergroup Assurance Dilemma (to model the defender group's interests) (Bornstein & Gilula Reference Bornstein and Gilula2003; Bornstein et al. Reference Bornstein, Mindelgrin and Rutte1996; De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Gross, Meder, Griffin, Prochazkova, Krikeb and Columbus2016a). Within groups, however, individuals are faced with a classic public goods provision problem. In this example, within each group, individuals have a binary decision to contribute or not contribute personal resources to the group's fighting capacity. The attacker group wins when it has more contributors than the defender group; otherwise, defenders “survive.” Individuals pay a cost c when engaging in attack or defense. Assuming that the spoils from victory are divided equally among all members of the attacker group, it is in each team's best interest to have its members contribute, and it is in each individual's best interest to not contribute in the hopes that others will.

Table 1. Team-level game of attack and defense

m A = Number of contributors in the attacker group; m D = Number of contributors in the defender group.

Note. Entries indicate aggregate group outcomes (defenders left, attackers right). Defenders and attackers start with 1 “utility” point. When defenders do not defend, they earn 2 points each (e.g., they spend their time farming). Attackers and defenders pay a cost of 1 when attacking and defending, respectively. When m A > m D, the attacker group appropriates the resources of the defender group. When m A ≤ m D, defenders survive and keep their earnings, whereas attackers have to pay the cost of attack without receiving any spoils from conflict. The upper triangle (shown in italics) of the payoff matrix constitutes attack-success. Numbers in boldface mark the best responses for each choice of the other group.

Hence, individuals within both attacker and defender groups face a dilemma between what is good for their group (to contribute) and what is good for themselves (to not contribute). At the same time, the motivation to not contribute may be stronger in attacker than defender groups. Regardless of whether an out-group attack fails or succeeds, non-contributors in attacker groups earn more than contributors. This is different in defender groups. When a defense is successful, non-contributors in the defender group earn more than contributors. But when in-group defense fails, all members lose regardless of whether or not they contributed. Thus, in defender groups, individual interests are by definition more aligned than in attacker groups because they share a common fate when they lose.

As in individual attack-defense conflicts, intergroup conflict often arises because attackers seek an improvement over their status quo that defenders seek to protect. Thus, such conflicts are captured as team-level variants of the Best-Shot/Weakest Link Game (Chowdhury et al. Reference Chowdhury, Lee and Sheremeta2013; Chowdhury & Topolyan Reference Chowdhury and Topolyan2016a; Note 4) and the Intergroup Aggressor-Defender Contest (IAD-C; De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Gross, Meder, Griffin, Prochazkova, Krikeb and Columbus2016a) in which individual contributions are modeled continuously rather than binary. For example, assume an equal number of members in the two rivaling groups, with N = N A = N D. Each member i is endowed with e from which she can contribute g (0 ≤ g≤ e) to their group's fighting capacity C (0 ≤ C≤ Ne). Individual contributions to the pool C are wasted, but when C A > C D, the attacker group wins the remaining resources of the defenders, with the spoils divided equally among attacker group members and added to their remaining endowments (e – g + (Ne – C D)/N). Defenders thus earn 0 when attackers win. However, when C A ≤ C D, defenders survive and individuals on both sides keep their non-invested resources (e – g). Accordingly, the incentive to free-ride is stronger in attacker than defender groups because, in case of failure, attackers keep what they did not contribute, whereas defenders earn nothing regardless of their contribution.

4.2. In-group cohesion and social identification

The stronger alignment of individual interests in defender groups, along with its anchoring on avoiding defeat, has important behavioral and psychological ramifications. Public good provision experiments show that, when group interests are more salient than individual interests, people are more likely to cooperate (e.g., Brewer & Kramer Reference Brewer and Kramer1986; De Dreu & McCusker Reference De Dreu and McCusker1997). And indeed, in Intergroup Attacker-Defender Contests, individuals free-ride less when defending than attacking (De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Gross, Meder, Griffin, Prochazkova, Krikeb and Columbus2016a; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Gross, De Dreu and Ma2018).

Facing an outside threat also drives people together into close-knitted groups (Boyer et al. Reference Boyer, Firat and Van Leeuwen2015; Hamilton Reference Hamilton1971; Radford Reference Radford2008; Willems & Van Schaik Reference Willems and Van Schaik2017) and increases group cohesion and social identification (Calo-Blanco et al. Reference Calo-Blanco, Kovářík, Mengel and Romero2017; Gilead & Lieberman Reference Gilead and Lieberman2014; Schaub Reference Schaub2017; see also Correll & Park Reference Correll and Park2005; Roccas et al. Reference Roccas, Sagiv and Schwartz2008). Cultural tightness, a tendency for groups to adhere to and enforce strong norms, is associated with more frequent attacks from enemy groups (Gelfand et al. Reference Gelfand, LaFree, Fahey and Feinberg2013), and in-group identification is stronger the more group and individual outcomes can be negatively influenced by out-groups (Bobo & Hutchins Reference Bobo and Hutchins1996; Quillian Reference Quillian1995; Weisel & Zultan Reference Weisel and Zultan2016).

We tested the possibility that in-group identification is stronger among defender than attacker groups by probing in-group identification following a series of contest rounds in which individuals contributed to out-group attack or to in-group defense. As predicted, we saw stronger identification among defenders than attackers (F[1, 24] = 14.71, p = 0.001; Fig. 4A). Importantly, and fitting the idea that in-group identification is a response to threat, identification among defenders was a positive function of their rivals' average investment in attack (r = 0.615, p = 0.001; Fig. 4B) and strongly predicted investments in in-group defense (r = 0.431, p = 0.035; Fig. 4C). Identification in attacker groups was unrelated to their rivals' level of defense (r = –0.136, p = 0.528) and negatively related to investment in out-group attack (r = –0.422, p = 0.040; Fig. 4B,C). Perhaps the latter finding is related to the relatively low success rates (approx. 25%) that attacker groups achieve even when they invest a lot (i.e., people dis-identifying from unsuccessful groups).

Figure 4. In-group identification. (A) In-group identification was measured after 10 investment rounds with one item: “I felt part of a group and identified with my colleagues” (1 = not at all, to 7 = very strongly). Ratings were averaged across members within defender and attacker groups (N = 24). (B, C) Dots show correlations (blue = defenders; red = attackers); solid lines represent best linear fit (blue = defenders; red = attackers). Data are based on unpublished results from De Dreu et al. (Reference De Dreu, Gross, Meder, Griffin, Prochazkova, Krikeb and Columbus2016a, experiment 1).

If in-group identification among defenders is a strong function of the threat posed by its rivals, the absence of out-group enemies may undermine in-group identification and loyalty. Because this makes the group a potentially attractive target for exploitation, groups may benefit from a continuous reminder of outside danger, which Boyer and Liénard (Reference Boyer and Liénard2006) refer to as the priming of a “mental hazard-precaution system.” Examples include leader rhetoric that elicits enemy images of threatening out-groups and alludes to the dangers associated with being unprepared and off-guard (Staub Reference Staub1996; Sternberg Reference Sternberg2003), or rites and rituals that allude to clues of possible danger (Watson-Jones & Legare Reference Watson-Jones and Legare2016). Modern-day rituals, such as military drills and mock battles, may similarly activate the mental hazard-precaution system. In addition to practicing and showing off strength and commitment to enemy states, they signal to their constituent audiences that the world is a dangerous place with untrustworthy neighbors.

4.3. Motivating contributions to out-group attack and in-group defense

Within defender groups, the stronger interest alignment and concomitant in-group identification can help resolve the individual tension between doing good to oneself (to not contribute) and doing good for the sake of the group (to contribute) in favor of the latter. This has a twofold implication. First, in-group cooperation emerges more spontaneously in defender rather than attacker groups. Second, and therefore, attacker groups are in greater need of measures to motivate their members to contribute to group fighting and to deter them from free-riding on their team mates (see also Humphreys & Weinstein Reference Humphreys and Weinstein2008).

Some measures that attacker groups use to motivate in-group cooperation directly aim to boost the otherwise fragile level of in-group identification. For example, attacker groups selectively invite friends to join a raid (Glowacki et al. Reference Glowacki, Isakov, Wrangham, McDermott, Fowler and Christakis2016; see also Gould Reference Gould1999; Reference Gould2000), build strong bonds and friendships among its members (Macfarlan et al. Reference Macfarlan, Walker, Flinn and Chagnon2014; Whitehouse et al. Reference Whitehouse, McQuinn, Buhrmester and Swann2014), and engage in cultural rituals such as war dances that increase cohesion and commitment among its warriors (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Callander, Reddish and Bulbulia2013; Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Jong, Bilkey, Whitehouse, Zollmann, McNaughton and Halberstadt2018; Lang et al. Reference Lang, Bahma, Shaver, Reddish and Xygalatas2017; Whitehouse & Lanman Reference Whitehouse and Lanman2014).

Other measures that attacker groups use are focused on deterring free-riding among its members. This includes the use of sanctions such as fines, physical punishment, gossip, and public shaming (Balliet & Van Lange Reference Balliet and Van Lange2013; Egas & Riedl Reference Egas and Riedl2008; Fehr & Gächter Reference Fehr and Gächter2002; Henrich et al. Reference Henrich, McElreath, Barr, Ensminger, Barrett, Bolyanatz, Cardenas, Gurven, Gwako, Henrich, Lesorogol, Marlowe, Tracer and Ziker2006; Ule et al. Reference Ule, Schram, Riedl and Cason2009; Yamagishi Reference Yamagishi1986). An extreme example of deterrence aimed punishment is the execution of deserting soldiers who refused to actively participate in attacking the enemy, as was practiced during the trench warfare of WWI (Axelrod Reference Axelrod1984). Experiments further show that punishment institutions indeed reduce free-riding and motivate individuals to contribute to their in-group's fighting capacity (Abbink et al. Reference Abbink, Brandts, Herrmann and Orzen2010, Reference Abbink, Brandts, Hermann and Orzen2012; Bernard Reference Bernard2012; Gneezy & Fessler Reference Gneezy and Fessler2012). Consistent with the current hypothesis, we found that punishment institutions were used more in attacker rather than defender groups, and reduced free-riding (De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Gross, Meder, Griffin, Prochazkova, Krikeb and Columbus2016a).

Sanctions do not have to be material or financial. For example, anthropologists have shown that belief in punitive gods, similar to peer punishment, not only promotes in-group cooperation, but also contributes to success in intergroup conflict (Atran & Ginges Reference Atran and Ginges2012; Johnson Reference Johnson2005; McKay et al. Reference McKay, Efferson, Whitehouse and Fehr2011; Norenzayan & Shariff Reference Norenzayan and Shariff2008; Norenzayan et al. Reference Norenzayan, Shariff, Gervais, Willard, McNamara, Slingerland and Henrich2016; Purzycki et al. Reference Purzycki, Apicella, Atkinson, Cohen, McNamara, Willard, Xygalatas, Norenzayan and Henrich2016). Resonating with the hypothesis that especially out-group attack groups benefit from religious beliefs is the finding that, across very different cultures, disadvantaged groups lacking religious spirit avoided aggression against their resource-rich and powerful counterparts, whereas disadvantaged groups with strong religiosity were less restrained and more likely to attack (Neuberg et al. Reference Neuberg, Warner, Mistler, Berlin, Hill, Johnson, Filip-Crawford, Millsap, Thomas, Winkelman, Broome, Taylor and Schober2014).

Although the literature on sanctions has largely focused on punishment, groups sometimes use moral, religious, or financial rewards to motivate members to contribute to out-group attack (Weinstein Reference Weinstein2005). For example, to entice the English to join the Second Crusade in 1147 CE, Bernard of Clairvaux wrote: “Take up arms with joy and with zeal for your Christian name… O mighty soldiers, O men of war, you have a cause for which you can fight without danger to your souls; a cause in which to conquer is glorious and for which to die is gain. But to those of you who are merchants, men quick to seek a bargain, let me point out the advantages of this great opportunity … the reward is great” (Brundage Reference Brundage1962, pp. 92–93). An interesting avenue for future research is to examine the effectiveness of promising rewards relative to the threat of punishment in motivating people to contribute to out-group attack and reduce free-riding during out-group attack. Indeed, Doğan et al. (Reference Doğan, Glowacki and Rusch2018) varied the distributions of possible earnings from victory within groups and found that privileged group members pushed for higher aggression against out-groups than disadvantaged group members.

Apart from group cohesion and reinforcement, leaders and institutions sometimes try to motivate attack by transforming group members' beliefs about the conflict structure. Putting attackers into a defensive mindset not only switches the reference point from a potential gain to a looming loss, but also exploits that collective defense is a shared interest and perceived as morally superior, while attack faces a more severe free-rider problem and is more likely to be seen as morally devious. Indeed, to change attackers' belief of the “game they are playing,” leaders and societies sometimes use propaganda – selective, misleading, and emotionally laden information aimed at creating an illusionary, yet threatening, scenario of loss and exploitation.

Recent history provides telling examples of such propaganda aimed at suggesting that attack is needed for defensive reasons (Fig. 5). Large-scale genocides and “ethnic cleansing” in Rwanda and former Yugoslavia served powerholders' desire for economic and territorial expansion and were justified by depicting “the enemy” as vicious threats to the nation's moral and cultural heritage and a danger to the nation's sovereignty (Mgbeoji Reference Mgbeoji2006; Staub Reference Staub1996; Sternberg Reference Sternberg2003). Between 1933 and 1938, Hitler justified Germany's aims at expansion with appeals to collective security, equality, and self-determination (Goddard Reference Goddard2015). The anti-Jewish propaganda after WWI and during Nazi Germany often portrayed Jews as scheming, backstabbing, and sneaky characters that betray and exploit “good patriots” when not on guard. A common theme of war propaganda is the creation of an imaginary attack on safety, health, and social order. During the Gleiwitz Incident in 1939, for example, Himmler's Schutzstaffel disguised as Polish attacked themselves. It allowed Hitler to frame his invasion of Poland the next morning as a defensive reaction to this attack.

Figure 5. Examples of historical propaganda aimed at convincing the viewer of a threat to the status quo. (A) “Destroy this mad brute,” a German soldier portrayed as a wild ape on the shore of America (WWI propaganda, ~1917). (B) “Jews, lice, and typhus,” depiction of a deformed head behind the outline of a louse, trying to associate Jews with sickness and contagiousness (Nazi propaganda, Warshaw, ~1941/1942). (C) “Is this tomorrow,” depiction of a burning American flag with fighting men in the foreground (anti-communist propaganda, 1947). (D) “Come unto me, ye opprest!” European Anarchist with dagger and bomb attempting to destroy the Statue of Liberty (American propaganda, 1919). (E) The depiction of a Jew backstabbing a German soldier at the front, illustrating the Dolchstoßlegende, a shared conspiracy theory during and after the Weimar Republic that the German defeat in WWI was caused by betrayal from inside (Austria, 1919).

4.4. Coordinating matching-mismatching of team attack and defense

By virtue of the common bad and the endogenously emerging in-group cohesion and identification, individuals within defender groups are aligned both in their self-sacrificial contributions to in-group defense and in their psychological orientation toward enemy threat. In general, such alignments enable tacit coordination on a shared focal point of not losing (Halevy & Chou Reference Halevy and Chou2014; Schelling Reference Schelling1960; Van Dijk et al. Reference Van Dijk, De Kwaadsteniet and De Cremer2009). In contrast, coordination should be more difficult in attacker groups. Next to the pertinent problem of motivating members to contribute, groups should attack when their target's in-group defense is low rather than high (per the principle of matching-mismatching of strategies). Thus, attacker groups not only need to motivate its members to contribute the proper force, but also need to coordinate the timing of their attack. Our experimental results indeed show that attacker groups not only invested less than defenders across contest rounds (Fig. 6A), but also that the variance in investments across rounds was substantially higher in attacker than defender groups (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Group-level attack and defense across contest rounds. (A) Investments into defense and attack across the five contest rounds (displayed means ± SE). (B) Mean variance for investments into defense and attack across the five contest rounds (displayed means ± SE). Data are based on unpublished results from De Dreu et al. (Reference De Dreu, Gross, Meder, Griffin, Prochazkova, Krikeb and Columbus2016a); baseline treatments of experiments 1 and 2 combined; N = 46 three-person attacker versus three-person defender groups.

In the absence of endogenously emerging norms and focal points on which to coordinate, attacker groups need explicit coordination mechanisms to align individual actions. Examples of such mechanisms include pre-decision communication, deferring to a leader, and clear command hierarchies. Indeed, public good provision experiments have shown better coordination when group members were able to communicate rather than not (Abele et al. Reference Abele, Stasser and Chartier2010; Alvard & Nolin Reference Alvard and Nolin2002; Janssen et al. Reference Janssen, Anderies and Joshi2011; Oprea et al. Reference Oprea, Charness and Friedman2014). Likewise, groups coordinate better when they have a leader (Glowacki & Von Rueden Reference Glowacki and Von Rueden2015; Gross et al. Reference Gross, Meder, Okamoto-Barth and Riedl2016; Levati et al. Reference Levati, Sutter and Van der Heijden2007; Potters et al. Reference Potters, Sefton and Vesterlund2007; Van Dijk et al. Reference Van Dijk, Wilke and Wit2003; Van Vugt & De Cremer Reference Van Vugt and De Cremer1999). Leaders can set the example for others to follow, and such leading-by-example coordinates contributions and reduces the variance in contributions within the group (Gächter et al. Reference Gächter, Nosenzo and Sefton2013; Hermalin Reference Hermalin1998; Loerakker & Van Winden Reference Loerakker and Van Winden2017).

There is some evidence for the hypothesis that especially attacker groups benefit from explicit coordination mechanisms. In two experiments using the Intergroup AD-Contest Game, we compared a baseline treatment in which group members decide simultaneously to a sequential decision-protocol in which one member made a first move to attack or not, followed by the second member, and so on. Defender groups were unaffected by this variation in decision procedure. Attacker groups, however, were significantly better at coordinating their contributions when they made attack decisions sequentially and were, therefore, more often victorious (De Dreu et al. Reference De Dreu, Gross, Meder, Griffin, Prochazkova, Krikeb and Columbus2016a; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Gross, De Dreu and Ma2018).

4.5. Summary and implications

Modeling intergroup conflict as team-level games of attack and defense revealed three insights. First, group-level defense creates a common fate for defenders that is absent in attackers and augments cohesiveness and in-group identification. Second, and relatedly, in-group defense elicits sacrifice and is more tacitly coordinated than out-group attack. Third, because out-group attack is more vulnerable to both motivation and coordination failures than in-group defense, effective out-group attack requires sociocultural arrangements to deter free-riding, to motivate self-sacrifice, and to coordinate the timing of attack. Bonding rituals, sanctioning institutions, communication, belief manipulation, and leadership may be functional and emerge more for motivating and coordinating out-group attack than in-group defense. Possibly also, the greater threat of free-riding in attacker groups may promote steeper hierarchical power structures (Gross et al. Reference Gross, Meder, Okamoto-Barth and Riedl2016) compared with defender groups, and may have accompanied the transitions to the centralization of power, the emergence of “warrior class” specialization, and dedicated hierarchically organized military organizations when humans moved from hunter-gatherer societies to chiefdoms and states (Boehm Reference Boehm2009; Reference Boehm2012; Carneiro Reference Carneiro, Jones and Krautz1981; Earle Reference Earle1987).

5. Conclusions and implications

There is a constant struggle … between the instinct of the one to escape its enemy and of the other to secure its prey.

— Charles Darwin (Reference Darwin1873)The present theory of attack and defense provides a threefold complement to existing conflict theory. We have argued that existing conflict theory is heavily focused on symmetric models. Symmetric conflicts, however, present a special class of conflict in which the motive to defend and the motive to attack and exploit are indistinguishable and present within each agent at the same time; the attacker is likewise defender, and vice versa. Asymmetric games of attack and defense, presented here, allow to tease apart these distinct motives. We have reviewed evidence that these new models are helpful in experimental studies to investigate the behavioral dynamics and underlying mechanisms involved when people seek victory and, alternatively, to protect against defeat and exploitation.

Teasing apart attack from defense can further reveal the functional relevance of a range of neurobiological, psychological, and sociocultural mechanisms for either attack or defense. As shown here, asymmetric conflict structures can help us understand when and why actors exhibit overconfidence, hostile attribution bias, dehumanization, and in-group identification. Our theory thus clarifies which of these psychological functions operate when and why.