Jaswal & Akhtar convincingly suggested that subjects with autism do not have diminished social motivation. However, they still recognize that autistic people behave socially in unusual ways: (a) low levels of eye contact, (b) infrequent pointing, (c) motor stereotypies, and (d) echolalia. Why?

By highlighting the outcome of different researchers in the field of autism (Caballero et al. Reference Caballero, Mistry, Vero and Torres2018; Curti et al. Reference Curti, Serret and Askenasy2015; Foxe et al. Reference Foxe, Molholm, Del Bene, Frey, Russo, Blanco, Saint-Amour and Ross2015; Stevenson et al. Reference Stevenson, Segers, Ferber, Barense and Wallace2014a; Torres et al. Reference Torres, Brincker, Isenhower, Yanovich, Stigler, Nurnberger, Metaxas and Jose2013) and the suggestions from an emerging field in neuroscience – multisensory integration and prediction (Riva Reference Riva2018) – in this commentary, we suggest that these behaviours are the results of a multisensory integration deficit. Specifically, we suggest that autistic people's unusual behaviours do not indicate diminished social motivation, but diminished social prediction skills.

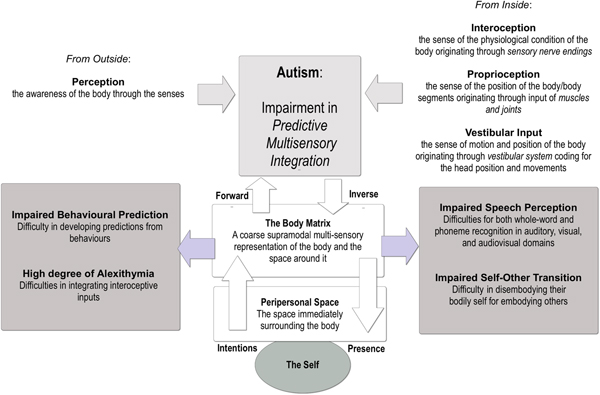

Recently, Riva (Reference Riva2018) suggested that our bodily experience is constructed from early development through the continuous integration of sensory and cultural data from different representations of the body. On one side, these representations are integrated into a coherent supramodal representation (body matrix) through a predictive, multisensory integration activated by central top-down attentional processes. On the other side, this integrated representation allows the self to extend its boundaries. There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that the peripersonal space (PPS) gates the representation of the potential motor acts afforded by visible objects allowing their identification as potential targets for one's own actions or the actions of others (Maranesi et al. Reference Maranesi, Bonini and Fogassi2014). Moreover, multisensory integration within PPS is strictly related to the ability to localize oneself in space and differentiate self from others (Noel et al. Reference Noel, Cascio, Wallace and Park2017). In this view, damage, malfunctioning, or altered feedback from and toward the body matrix (multisensory integration deficit) might be involved in the aetiology of different disturbances (Riva et al. Reference Riva, Serino, Di Lernia, Pavone and Dakanalis2017), including autism. Specifically, recent studies showed that all the deficits that characterize autism spectrum disorder (ASD) – the presence of repetitive behaviours and restricted interest, the lack of social reciprocity, and language or communication problems – can be explained by impairments in multisensory processing (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Multisensory impairments in autism.

First, the original work by Elizabeth Torres and her team suggests that individuals with autism are impaired in updating the body matrix with new contents from real-time perception-driven inputs (Caballero et al. Reference Caballero, Mistry, Vero and Torres2018; Torres & Denisova Reference Torres and Denisova2016). In their studies, Torres and colleagues demonstrated that in these individuals there is a deficit in micro-movement proprioception that limits their ability to make meaningful categorizations of movements and sense unexpected internal and external disruptions. In other words, individuals with autism are not able to perceive the temporal relationship between cross-modal inputs, making it difficult to develop reliable statistical predictions from their behavioural variability (Stevenson et al. Reference Stevenson, Siemann, Schneider, Eberly, Woynaroski, Camarata and Wallace2014b). This situation forces subjects with autism to live with a constant element of surprise, amplifying anxiety and reducing predictability, also in social situations.

Furthermore, recent evidence also suggested that deficits in the integration of bodily inputs that arise from within the body (i.e., interoceptive inputs) might be associated with the fundamental emotional impairments that characterize the autistic condition (Hatfield et al. Reference Hatfield, Brown, Giummarra and Lenggenhager2019; Mul et al. Reference Mul, Stagg, Herbelin and Aspell2018). In addition, autistic people often showed a high degree of alexithymia – namely, the inability to correctly recognize emotions and self-related both in other persons – and this trait has also been recently connected to alterations in the processing of interoceptive inputs (Hatfield et al. Reference Hatfield, Brown, Giummarra and Lenggenhager2019; Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Catmur and Bird2018), further supporting the hypothesis that multisensory integration deficits might determine the severe social skill impairments in people with autism (Noel et al. Reference Noel, Lytle, Cascio and Wallace2018).

In addition, difficulty in predicting behaviours also affects relationships with others. Specifically, as demonstrated by recent studies using the rubber hand illusion, individuals with autism have difficulty in disembodying their bodily self for embodying others, which affects their social and communication abilities (Noel et al. Reference Noel, Cascio, Wallace and Park2017). As noted by Noel et al. (Reference Noel, Cascio, Wallace and Park2017), “[these individuals] show a steeper gradient between self and other. Stated more concretely, the prediction is that the spatial extent within which the far exteroceptive sensory modalities, such as audition and vision, the transition from not influencing tactile processing on the body to influencing tactile processing is smaller than under typical circumstances” (p. 10).

Last, it is well known that individuals with ASD have difficulties for both whole-word and phoneme recognition in auditory, visual, and audiovisual domains (Stevenson et al. Reference Stevenson, Segers, Ferber, Barense and Wallace2014a; Stevenson et al. Reference Stevenson, Baum, Segers, Ferber, Barense and Wallace2017). As recently demonstrated by Stevenson et al. (Reference Stevenson, Baum, Segers, Ferber, Barense and Wallace2017), these difficulties are associated with a reduced ability in multisensory integration. This lack of multisensory integration had a more relevant impact at the level of whole-word recognition and at low signal-to-noise ratios.

In conclusion, the assumption that autistic people's unusual behaviours indicate diminished social motivation has to be replaced by the one that they have diminished social prediction skills. Specifically, they are not able to use multisensory integration for doing stable prediction of both their own and others’ behaviours. This is due to an impaired ability to integrate multisensory information, including social ones, into a cross-modal and coherent content.

Jaswal & Akhtar convincingly suggested that subjects with autism do not have diminished social motivation. However, they still recognize that autistic people behave socially in unusual ways: (a) low levels of eye contact, (b) infrequent pointing, (c) motor stereotypies, and (d) echolalia. Why?

By highlighting the outcome of different researchers in the field of autism (Caballero et al. Reference Caballero, Mistry, Vero and Torres2018; Curti et al. Reference Curti, Serret and Askenasy2015; Foxe et al. Reference Foxe, Molholm, Del Bene, Frey, Russo, Blanco, Saint-Amour and Ross2015; Stevenson et al. Reference Stevenson, Segers, Ferber, Barense and Wallace2014a; Torres et al. Reference Torres, Brincker, Isenhower, Yanovich, Stigler, Nurnberger, Metaxas and Jose2013) and the suggestions from an emerging field in neuroscience – multisensory integration and prediction (Riva Reference Riva2018) – in this commentary, we suggest that these behaviours are the results of a multisensory integration deficit. Specifically, we suggest that autistic people's unusual behaviours do not indicate diminished social motivation, but diminished social prediction skills.

Recently, Riva (Reference Riva2018) suggested that our bodily experience is constructed from early development through the continuous integration of sensory and cultural data from different representations of the body. On one side, these representations are integrated into a coherent supramodal representation (body matrix) through a predictive, multisensory integration activated by central top-down attentional processes. On the other side, this integrated representation allows the self to extend its boundaries. There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that the peripersonal space (PPS) gates the representation of the potential motor acts afforded by visible objects allowing their identification as potential targets for one's own actions or the actions of others (Maranesi et al. Reference Maranesi, Bonini and Fogassi2014). Moreover, multisensory integration within PPS is strictly related to the ability to localize oneself in space and differentiate self from others (Noel et al. Reference Noel, Cascio, Wallace and Park2017). In this view, damage, malfunctioning, or altered feedback from and toward the body matrix (multisensory integration deficit) might be involved in the aetiology of different disturbances (Riva et al. Reference Riva, Serino, Di Lernia, Pavone and Dakanalis2017), including autism. Specifically, recent studies showed that all the deficits that characterize autism spectrum disorder (ASD) – the presence of repetitive behaviours and restricted interest, the lack of social reciprocity, and language or communication problems – can be explained by impairments in multisensory processing (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Multisensory impairments in autism.

First, the original work by Elizabeth Torres and her team suggests that individuals with autism are impaired in updating the body matrix with new contents from real-time perception-driven inputs (Caballero et al. Reference Caballero, Mistry, Vero and Torres2018; Torres & Denisova Reference Torres and Denisova2016). In their studies, Torres and colleagues demonstrated that in these individuals there is a deficit in micro-movement proprioception that limits their ability to make meaningful categorizations of movements and sense unexpected internal and external disruptions. In other words, individuals with autism are not able to perceive the temporal relationship between cross-modal inputs, making it difficult to develop reliable statistical predictions from their behavioural variability (Stevenson et al. Reference Stevenson, Siemann, Schneider, Eberly, Woynaroski, Camarata and Wallace2014b). This situation forces subjects with autism to live with a constant element of surprise, amplifying anxiety and reducing predictability, also in social situations.

Furthermore, recent evidence also suggested that deficits in the integration of bodily inputs that arise from within the body (i.e., interoceptive inputs) might be associated with the fundamental emotional impairments that characterize the autistic condition (Hatfield et al. Reference Hatfield, Brown, Giummarra and Lenggenhager2019; Mul et al. Reference Mul, Stagg, Herbelin and Aspell2018). In addition, autistic people often showed a high degree of alexithymia – namely, the inability to correctly recognize emotions and self-related both in other persons – and this trait has also been recently connected to alterations in the processing of interoceptive inputs (Hatfield et al. Reference Hatfield, Brown, Giummarra and Lenggenhager2019; Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Catmur and Bird2018), further supporting the hypothesis that multisensory integration deficits might determine the severe social skill impairments in people with autism (Noel et al. Reference Noel, Lytle, Cascio and Wallace2018).

In addition, difficulty in predicting behaviours also affects relationships with others. Specifically, as demonstrated by recent studies using the rubber hand illusion, individuals with autism have difficulty in disembodying their bodily self for embodying others, which affects their social and communication abilities (Noel et al. Reference Noel, Cascio, Wallace and Park2017). As noted by Noel et al. (Reference Noel, Cascio, Wallace and Park2017), “[these individuals] show a steeper gradient between self and other. Stated more concretely, the prediction is that the spatial extent within which the far exteroceptive sensory modalities, such as audition and vision, the transition from not influencing tactile processing on the body to influencing tactile processing is smaller than under typical circumstances” (p. 10).

Last, it is well known that individuals with ASD have difficulties for both whole-word and phoneme recognition in auditory, visual, and audiovisual domains (Stevenson et al. Reference Stevenson, Segers, Ferber, Barense and Wallace2014a; Stevenson et al. Reference Stevenson, Baum, Segers, Ferber, Barense and Wallace2017). As recently demonstrated by Stevenson et al. (Reference Stevenson, Baum, Segers, Ferber, Barense and Wallace2017), these difficulties are associated with a reduced ability in multisensory integration. This lack of multisensory integration had a more relevant impact at the level of whole-word recognition and at low signal-to-noise ratios.

In conclusion, the assumption that autistic people's unusual behaviours indicate diminished social motivation has to be replaced by the one that they have diminished social prediction skills. Specifically, they are not able to use multisensory integration for doing stable prediction of both their own and others’ behaviours. This is due to an impaired ability to integrate multisensory information, including social ones, into a cross-modal and coherent content.

Acknowledgments

This article was supported by the Italian Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca (MIUR) research project “Unlocking the memory of the body: Virtual Reality in Anorexia Nervosa” (201597WTTM).