Cleansing behavior permeates everyday life. From morning to evening, people engage in any number of cleansing routines such as washing their hands, cleaning their face, brushing their teeth, rinsing their mouth, taking a shower, clipping their nails, shaving their body hair, clearing the garbage, doing the dishes, laundering the clothes, and vacuuming the house. Data from the most recent American Time Use Survey (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017) indicate that the four categories with the highest percentages of the civilian population engaging in relevant activities per day were sleeping (99.9%), eating and drinking (95.1%), leisure and sports (95.6%), and grooming (80.1%). Among those who engaged in grooming activities (e.g., bathing/showering, brushing/flossing teeth, shaving, washing face, and washing hands), women spent 57 min per day on them, men 44 min. The next major category was household activities (76.2%), which included activities such as interior cleaning (23.1%; 91 min per day among those who engaged in relevant activities), laundry (15.7%; 62 min), and kitchen and food cleanup (22.4%; 34 min). People devote a non-trivial amount of time to personal grooming and household cleansing on a regular basis.

Although norms regarding the form and frequency of cleansing vary between societies and historical periods (Ashenburg, Reference Ashenburg2007; Hoy, Reference Hoy1995), the existence of hygienic care is a human universal (Brown, Reference Brown1991). It is understandable, as personal hygiene confers public health benefits and survival value (Lee & Schwarz, Reference Lee, Schwarz, Duschinsky, Schnall and Weiss2016). For example, hand hygiene is one of the easiest and most cost-effective mechanisms for reducing risks of many diseases (Boyce & Pittet, Reference Boyce and Pittet2002; Kampf & Kramer, Reference Kampf and Kramer2004) and is among the routines most recommended by the World Health Organization (Pittet, Allegranzi, & Boyce, Reference Pittet, Allegranzi and Boyce2009), particularly during contagious pandemics (e.g., COVID-19). But even without pandemics, every year awareness of the benefits of hand-washing is raised on October 15 – the Global Handwashing Day.

Health may not be the only reason for cleansing behavior though. A burgeoning body of work in the past 15 years has revealed a host of psychological antecedents and consequences of physical cleansing. Unlike earlier studies, which tended to be correlational or observational in nature, this recent wave of research was experimental and highlighted causal links between cleansing and various psychological aspects of daily life, such as religion, morality, emotion, well-being, and decision-making. The findings provide insight into what domains can be influenced by cleansing. But much less is known about how cleansing produces these effects. This paper seeks to move the focus from “wow” to “how” (Strack, Reference Strack2012), from the loosening to the tightening phase in the creative cycle of theory formation (Fiedler, Reference Fiedler2004, Reference Fiedler2018). The potential to advance theoretical understanding, capture empirical nuances, and generate unique predictions motivates us to offer a mechanistic account for the psychology of cleansing, with generalizability to other physical actions.

This paper is organized as follows: Cleansing effects have been observed across a variety of psychological domains. Empirically, how replicable and robust are these effects? Theoretically, how do they operate? Major prevailing accounts include the conceptual metaphor of Morality Is Cleanliness/Purity (Lakoff & Johnson, Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980, Reference Lakoff and Johnson1999) and, relatedly, the emotion of disgust (Rozin & Fallon, Reference Rozin and Fallon1987; Rozin, Haidt, & McCauley, Reference Rozin, Haidt, McCauley, Lewis, Haviland-Jones and Barrett2008). By focusing on the moral domain and on disgusting stimuli, they capture a subset of cleansing effects, but cannot easily handle cleansing effects in non-moral, non-disgusting contexts. To fill the gap, we offer the construct grounded procedures. We propose that grounded procedures of separation can be a proximate mechanism underlying cleansing effects. This account differs from the prevailing ones in terms of explanatory kind, interpretive parsimony, and predictive scope. Its components are falsifiable. Its unique predictions have received empirical support. The construct of grounded procedures is generalizable to other physical actions of separation beyond cleansing. As a flipside of separation, grounded procedures of connection are also observed. Together, separation and connection open up new conceptual and empirical questions. They shed light on cognitive functioning, attitude change, and the interplay between mental and physical processes.

1. Cleansing effects across domains

By “cleansing effects,” we mean experimental effects of two kinds: (1) effects of cleansing-related manipulations on psychological outcomes and (2) effects of psychological manipulations on cleansing-related outcomes. That is, the term includes both the psychological consequences and antecedents of cleansing. As an example of the first kind, an experiment manipulated cleansing behavior in the context of risky decision-making driven by luck (Xu, Zwick, & Schwarz, Reference Xu, Zwick and Schwarz2012, Experiment 2). Participants who kept losing money in a gambling situation felt unlucky and made smaller bets in a subsequent round. But if they were asked to wash their hands (under the pretense of testing and evaluating a soap product), the impact of their losing streak was eliminated, as if they had washed away their bad luck. Conversely, participants who kept winning money felt lucky and made bigger bets. But washing their hands eliminated the impact of their winning streak, as if they had washed away their good luck. Merely examining the soap, without washing one's hands, did not influence gambling behavior.

As an example of the second kind of cleansing effects, a pair of experiments examined the impact of ostracism on cleansing-related desires (Poon, Reference Poon2019). Participants experienced cyberostracism by receiving two (as opposed to 10) out of 30 ball tosses in a Cyberball game (Experiment 1) or by receiving one like (as opposed to five likes) from 11 users on a social networking site (Experiment 2). Both manipulations increased participants' willingness to purchase cleansing products, but not their willingness to purchase non-cleansing products (Experiment 2).

Both kinds of cleansing effects have been observed in a variety of psychological domains, be they directly related to morality (e.g., fairness/cheating, sanctity/degradation), indirectly related to morality (e.g., religiosity, empathy), or unrelated to morality (e.g., postdecisional dissonance, information processing). Cleansing-related manipulations range from actual behavior (e.g., washing hands with soap, discarding objects) to mental simulation of behavior (e.g., imagining taking a shower, watching video of someone else using an antiseptic wipe) to conceptual activation (e.g., unscrambling sentences or words related to cleansing). Cleansing-related outcomes also range from actual behavior (e.g., likelihood of washing hands, time spent cleaning an object) to judgment/feeling (e.g., desirability of cleansing products, extent of feeling clean or dirty) to concept accessibility (e.g., number of cleansing-related words completed, reaction time in lexical decisions of cleansing-related words).

1.1. Replicability concerns

Among all the psychological domains involved in cleansing effects, morality has received the most attention (for recent reviews, see Lee & Schwarz, Reference Lee, Schwarz, Duschinsky, Schnall and Weiss2016; West & Zhong, Reference West and Zhong2015). Two early papers on the clean–moral link sparked interest in the field. One paper (Zhong & Liljenquist, Reference Zhong and Liljenquist2006) reported that participants who recalled their own immoral (as opposed to moral) behavior or hand-copied a story of someone else's immoral (as opposed to moral) behavior later completed more cleansing-related word fragments (Experiment 1), evaluated cleansing products more favorably (Experiment 2), and were more likely to choose an antiseptic wipe over a pencil as a free gift (Experiment 3). After recalling their own immoral behavior, participants who were (vs. were not) asked to use an antiseptic wipe had lower levels of immoral emotions and became less likely to volunteer to help another researcher (Experiment 4). Another paper (Schnall, Benton, & Harvey, Reference Schnall, Benton and Harvey2008) reported that participants judged moral violations in vignettes to be less wrong if they had unscrambled sentences containing cleansing/purity-related (vs. neutral) words (Experiment 1) or if they had (vs. had not) been asked to wash their hands after watching a disgusting film clip and before judging the moral violations (Experiment 2).

These and other cleansing effects have prompted replications and extensions. Some of the replications found non-significant results and/or smaller effects than in the original experiments. For example, regarding Schnall et al. (Reference Schnall, Haidt, Clore and Jordan2008), one paper (Johnson, Cheung, & Donnellan, Reference Johnson, Cheung and Donnellan2014b) reported direct replications using American samples (as opposed to the original British samples) and found effect sizes (Cohen's ds) of 0.009 and −0.016 (as opposed to the original 0.606 and 0.852). Another paper (Huang, Reference Huang2014) reported extended replications of Schnall et al.'s Experiment 1 by moving the setting from lab to online and by adding a measure (Experiment 1) or a manipulation (Experiments 2 and 2a) of participants' response effort. When response effort was low, the expected effects were observed (ds = 0.409, 0.289, and 0.375) though smaller in size than the original (0.606). When response effort was high, the effects trended in the opposite direction (ds = −0.186 and −0.173 in Experiments 2 and 2a; data not available for Experiment 1).

Regarding Zhong and Liljenquist (Reference Zhong and Liljenquist2006), one paper reported direct replications of the original effects using Spanish samples (Gámez, Díaz, & Marrero, Reference Gámez, Díaz and Marrero2011) and found effect sizes of 0.088, −0.024, 0.562, 0.269, and 0.716, as opposed to the original 0.290, 0.997, 0.887, 0.443, and 0.777 among North American samples. Another paper reported variations of the original Experiment 2 by adding a measure (willingness to pay for cleansing products; Earp, Everett, Madva, & Hamlin, Reference Earp, Everett, Madva and Hamlin2014, Replications 1–3), moving the setting from lab to online (Replications 2 and 3), changing the manipulation from hand-copying a passage to retyping it and inserting punctuation marks (Replications 2 and 3), and testing different populations (United Kingdom in Replication 1 and India in Replication 3). Effect sizes for the desirability of cleansing products were −0.005, 0.130, and −0.223, as opposed to the original 0.997. Yet another paper reported a conceptual replication of the original Experiment 3 by having participants first complete 183 ratings of their own conscientiousness and nominate others to rate their personality (Fayard, Bassi, Bernstein, & Roberts, Reference Fayard, Bassi, Bernstein and Roberts2009). This paper also reported a conceptual replication of the original Experiment 4 by changing the design from one-factor (wipe vs. no wipe) to 2 (wipe vs. no wipe) × 2 (scent vs. no scent) × 2 (rubbing vs. no rubbing). Relevant effect sizes were 0.110 and 0.230, as opposed to the original 0.887 and 0.777.

Non-significant and/or smaller effects of this sort have caused concern about the replicability of cleansing effects, especially considering that the replications typically used larger sample sizes than did the original experiments. Multiple interpretations are plausible. One is that the original effects were statistical flukes. Another is that the original effects were true phenomena limited to specific manipulations, measures, settings, or populations, that is, they had low generalizability. Yet another interpretation requires us to zoom out, situate both the original experiments and the replications in the broader context of all relevant effects, and evaluate the strength of evidence overall. This last interpretive approach is meta-analytic in nature.

1.2. Meta-analytic assessment

A comprehensive meta-analysis (Lee, Chen, Ma, & Hoang, Reference Lee, Chen, Ma and Hoang2020a) has extracted and quantified all identifiable cleansing effects (k effects > 500) from true experiments (k studies > 200) obtained from peer-reviewed journal articles, doctoral dissertations, conference proceedings, and unpublished reports. All effects and experiments were coded on various moderators (e.g., whether the effect pertained to psychological consequences or antecedents of cleansing, what cleansing-related manipulations and measures were used). Full results are beyond the scope of this paper, but a few observations are relevant and summarized qualitatively here.

At the broadest level, the overall effect estimate was in the small-to-medium range (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988) and highly significant (because of a large total sample size, typical in meta-analyses) regardless of whether a fixed-effect model or a multilevel random-effects model was used. Effect sizes were highly heterogeneous, indicating probable moderation.

The overall effect estimates, however, were likely to be overly optimistic because of concerns about researchers' degrees of freedom and publication bias. Researchers' degrees of freedom were addressed in replications, discussed in the next paragraph. Publication bias was addressed using statistical tools such as (1) fail-safe n (Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg2005; Rosenthal, Reference Rosenthal1979), (2) trim-and-fill (Duval & Tweedie, Reference Duval and Tweedie2000a, Reference Duval and Tweedie2000b), and (3) normal-quantile plot. (1) The fail-safe n estimated that several hundred thousand missing null effects would have to exist in file drawers to bring the overall effect estimate from significant to non-significant. If the fail-safe n is larger than (5k effects + 10), the overall effect is considered unlikely to be a mere consequence of publication bias (Rosenthal, Reference Rosenthal1979). Several hundred thousand is larger than 5 × 500 + 10 = 2,510. (2) Applying the most demanding trim-and-fill adjustments, the overall effect estimate would be in the small (fixed-effect model) or small-to-medium range (random-effects model), remaining highly significant. (3) Examination of the normal-quantile plot suggested that positive bias would be minimized by excluding large positive effects and retaining effects that were small, null, or negative (i.e., contrary to hypothesis). After exclusions, the overall effect estimate remained highly significant in the small range (in both fixed-effect and random-effects models). These patterns indicate that publication bias alone was unlikely to account for the existence of cleansing effects.

Turning to replications, each report was coded in terms of whether the authors presented it as an original experiment, a successful replication, or an unsuccessful replication. Unsurprisingly, the three categories differed in their overall fixed-effect estimatesFootnote 1: Medium among original experiments, small-to-medium in successful replications, and null among unsuccessful replications. Consider psychological consequences of cleansing. It is noteworthy that successful replications (k effects = 32, k studies = 9) exist alongside unsuccessful ones (k effects = 21, k studies = 8), sometimes of the same original experiment. For example, Schnall et al.'s (Reference Schnall, Haidt, Clore and Jordan2008) findings were unsuccessfully replicated in three replications (Johnson, Cheung, & Donnellan, Reference Johnson, Cheung and Donnellan2014a, Reference Johnson, Cheung and Donnellan2014b), but successfully replicated in two other direct replications (Arbesfeld, Collins, Baldwin, & Daubman, Reference Arbesfeld, Collins, Baldwin and Daubman2014; Besman, Dubensky, Dunsmore, & Daubman, Reference Besman, Dubensky, Dunsmore and Daubman2013) and three extended replications (Huang, Reference Huang2014). The report of unsuccessful replications has received much more attention (104 citations) than the report of successful extended replications (19 citations), even though the latter had larger sample sizes than the former. Such difference in attention is likely to reflect the zeitgeist of our field as it grapples with replicability issues, but caution is warranted in ensuring balanced coverage of successful and unsuccessful replications.

Beyond replications, how robust are cleansing effects across methods and domains? Cleansing effects have been observed across types of manipulation, measure, population, and publication status of the report. The majority of fixed-effect estimates were in the small range. Within the broad domain of morality, the strongest cleansing effects pertained to the sanctity/degradation foundation, presumably because of the substantive overlap between physical cleansing and moral purity. But many cleansing effects have been observed in other domains that are indirectly related or unrelated to morality, with similar effect sizes to those directly related to morality.

These patterns depict the landscape of cleansing effects as a function of original experiments versus replications and other conceptual or methodological variables. A theoretical understanding of the observed variability will benefit from closer consideration of the processes underlying cleansing effects. How do these effects operate?

2. Existing accounts for cleansing effects

Experimental work on cleansing effects is most commonly interpreted in terms of two highly related, mutually compatible accounts: conceptual metaphor theory and the emotion of disgust. Conceptual metaphor theory (Lakoff & Johnson, Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980, Reference Lakoff and Johnson1999) argues that thought about psychological domains (e.g., morality) is abstract, difficult, and aided by experience with sensorimotor domains (e.g., cleanliness), which is more concrete, easier to comprehend, and older ontogenetically and phylogenetically (Williams, Huang, & Bargh, Reference Williams, Huang and Bargh2009). Because of these differences, sensorimotor domains tend to serve as the source of image schemas and relational/inferential structures, which are mapped onto target psychological domains. A specific sensorimotor domain is linked to a specific psychological domain because of their co-occurrence in early life experience. The resultant cross-domain mappings (e.g., cleanliness ⇒ morality) are known as conceptual metaphors. These cognitive structures have linguistic, affective, and socio-cultural manifestations.

Linguistically, English speakers utter on average six metaphorical expressions per minute in spoken conversation (Gibbs, Reference Gibbs1994). They do so effortlessly and unintentionally. The metaphorical expressions show systematic patterns that reflect underlying conceptual mappings of concrete experience to abstract thought; in other words, they are not random, not merely decorative, not just “language-deep” (Boroditsky, Reference Boroditsky2000, p. 6), but cognition-deep. In fact, “[m]etaphor is so widespread in language that it's hard to find expressions for abstract ideas that are not metaphorical” (Pinker, Reference Pinker2007, p. 6, italics original). The existence of conceptual metaphorical structures can be inferred from coherent systems of linguistic metaphorical expressions. For example, reflecting the conceptual metaphor Morality Is Cleanliness/Purity:

“She's pure as the driven snow. He's a dirty old man. O Lord, create a pure heart within me. Let me be without spot of sin. That was a disgusting thing to do! If elected, I will clean up this town!” (Lakoff & Johnson, Reference Lakoff and Johnson1999, p. 308)

This conceptual metaphor is also apparent in the affective properties of disgust. An experientially powerful, evolutionarily old, and adaptively significant emotion, disgust can be elicited by physically dirty stimuli or morally inappropriate behaviors (Rozin & Fallon, Reference Rozin and Fallon1987; Rozin et al., Reference Rozin, Haidt, McCauley, Lewis, Haviland-Jones and Barrett2008). The extension of disgust from the physical to the moral realm is detectable among kindergarteners and continues to develop with age (Danovitch & Bloom, Reference Danovitch and Bloom2009). The precise nature of disgust does differ somewhat as a function of whether it is elicited by physical stimuli (e.g., pathogens and disease cues) or moral violations (e.g., incest and deception; Oaten, Stevenson, and Case, Reference Oaten, Stevenson and Case2009; Tybur, Lieberman, Kurzban, and DeScioli, Reference Tybur, Lieberman, Kurzban and DeScioli2013). The former is closer to fear, the latter to anger (Lee & Ellsworth, Reference Lee, Ellsworth, Fontaine, Scherer and Soriano2013; Russell & Giner-Sorolla, Reference Russell and Giner-Sorolla2013). Despite its different shades, disgust is a uniquely common reaction to both physical dirtiness and moral transgressions (Chapman & Anderson, Reference Chapman and Anderson2013).

Paralleling its linguistic and affective manifestations, the conceptual metaphor Morality Is Cleanliness/Purity is also embedded in sociocultural customs and beliefs across history and societies (Douglas, Reference Douglas1966). Whether it is baptism in Christianity, achamanam in Hinduism, or corpse-rinsing before burial in ancient Egypt, purification rituals are prevalent and imbue acts of physical cleansing with symbolic renewal of body, soul, and spirit (Blackman, Reference Blackman1918; Eliade, Reference Eliade1958/1996; Michael, Reference Michael1979). Preachers put cleanliness right next to godliness (Wesley, Reference Wesley1778). As a standard part of the Catholic Mass, the priest proclaims, “Wash away all my iniquity and cleanse me of my sin” (Psalm 51:2). Similar ideas and practices are observed across major religions, from Judeo-Christian to Dharmic to indigenous ones. The moral overtones of cleanliness have also been noted in political ideology (e.g., Graham, Haidt, and Nosek, Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009; Herzfeld, Reference Herzfeld, Duschinsky, Schnall and Weiss2017; Williams, Reference Williams, Duschinsky, Schnall and Weiss2017), English literature (Firestone & Lyne, Reference Firestone, Lyne, Duschinsky, Schnall and Weiss2017), and other realms of human endeavor (Duschinsky, Schnall, & Weiss, Reference Duschinsky, Schnall and Weiss2017).

Together, conceptual metaphor theory and the emotion of disgust shed light on the cognitive and affective underpinnings of the psychology of cleansing, evident in systematic patterns of linguistic expressions and sociocultural observations. These accounts offer evolutionary, developmental, and adaptive interpretations. We share their general assumptions, which have inspired our own work. But we also note explanatory gaps.

2.1. Limitations of existing accounts

Both existing accounts focus on the psychology of cleansing within the moral domain. They do not explain or predict cleansing effects in non-moral domains. The emotion of disgust does not explain or predict cleansing effects in non-disgusting situations. Empirically, a variety of cleansing effects have been documented in non-moral, non-disgusting contexts (Lee & Schwarz, Reference Lee, Schwarz, Duschinsky, Schnall and Weiss2016; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Chen, Ma and Hoang2020a). That means the existing accounts capture a subset rather than the full range of cleansing effects.

Another gap is in the level of analysis or category of explanation. An integrative understanding of behavior, as the Nobel-winning ethologist Nikolaas Tinbergen (Reference Tinbergen1963/2010) pointed out, includes four categories of explanation: How it evolves in a species (phylogeny), how it develops in an individual (ontogeny), what adaptive problems it solves (function), and what causal processes drive its operation (mechanism). The existing accounts focus on phylogenetic, ontogenetic, and functional interpretations. Proximate mechanisms remain to be fleshed out. There is the conceptual metaphorical association between morality and cleanliness, and there is the emotion of disgust in response to violations of ethical and sanitary norms, but what are the physical or mental processes that mediate the online operation of these links?

Recognizing these gaps, we seek to complement the existing accounts by offering a mechanistic one. For it to be useful, it has to capture a wider range of cleansing effects across domains. It also has to specify a process that explains prior findings and predicts new ones. Drawing on insights from grounded cognition (Barsalou, Reference Barsalou2008) and information processing (Wyer, Xu, & Shen, Reference Wyer, Xu, Shen, Olson and Zanna2012), we propose the construct grounded procedures of separation.

3. Grounded procedures of separation

3.1. Definitions

What do we mean by grounded, procedure, and separation? Inspired by grounded views on cognitive and social psychological processes (Anderson, Reference Anderson2010; Barsalou, Reference Barsalou1999, Reference Barsalou2008; Glenberg, Reference Glenberg1997; Glenberg & Kaschak, Reference Glenberg and Kaschak2002; Niedenthal, Barsalou, Winkielman, Krauth-Gruber, & Ric, Reference Niedenthal, Barsalou, Winkielman, Krauth-Gruber and Ric2005; Semin & Smith, Reference Semin and Smith2008; Shapiro, Reference Shapiro2011; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Huang and Bargh2009; Wilson, Reference Wilson2002), our guiding assumption is that mental representations and functions are grounded in sensorimotor modalities for experiencing and interacting with physical reality.Footnote 2 In other words, mental processes (e.g., knowledge, language, thought) do not reside in a layer of amodal symbols abstracted and detached from sensorimotor capacities for perception and action. Instead, the mental is grounded in the physical (Harnad, Reference Harnad1990).Footnote 3 Activating one activates the other.

Sensorimotor capacities can be engaged in multiple ways. Engagement is strongest in online sensorimotor experience (e.g., actual physical movement), weaker in offline simulation of it (e.g., deliberate mental imagery), and weaker still in merely partial offline simulation of it (as typically triggered by, e.g., semantic activation). This gradation in strength implies that contrary to a common misperception of grounded perspectives, cognitive activity does not necessitate online bodily states or full-blown offline simulation of them. Instead, cognition can be grounded in partial offline simulation of physical experience as recreated by sensorimotor modalities in the brain (Barsalou, Reference Barsalou2008).

Regardless of the mode of engagement, the influence of a sensorimotor experience depends on its salient attributes in context. Any entity carries multiple attributes, some of which are more salient than others at a given moment. For example, the color and taste of an apple are typically more salient than the fact that it grows on trees. But what is salient is context-dependent (Higgins, Reference Higgins, Higgins and Kruglanski1996). In an agronomy class, the growth history of an apple becomes salient. The principle of context-dependent attribute salience implies that the same sensorimotor experience can be construed differently to highlight different salient attributes, resulting in different effects (Körner & Strack, Reference Körner and Strack2019).

We tie these principles of grounding to the construct of procedure, which refers to “the sequence of steps that can be taken to attain a particular objective” (Wyer et al., Reference Wyer, Xu, Shen, Olson and Zanna2012, p. 241). Procedures can be “cognitive or motor” (p. 239), that is, mental or physical. An important property of procedures is that once a procedure is activated to attain a particular objective in one situation, it becomes more likely to be used in a later, unrelated situation, even if the original objective is no longer relevant (Wyer et al., Reference Wyer, Xu, Shen, Olson and Zanna2012; Xu, Schwarz, & Wyer, Reference Xu, Schwarz and Wyer2015). A procedure is thus not restricted to a single objective, but applicable across objectives and content domains (Janiszewski & Wyer, Reference Janiszewski and Wyer2014), resembling the principle of multifinality (i.e., one means, several ends; Kruglanski et al., Reference Kruglanski, Köpetz, Bélanger, Chun, Orehek and Fishbach2013).

A procedural view on mental activities is itself a scientific metaphor in that it treats the mind as if it were a physical entity, and mental operations as if they were operations on physical objects, thereby drawing researchers' attention to functionalist, process-oriented properties (Kolers & Roediger, Reference Kolers and Roediger1984; Watkins, Reference Watkins1981). Much like cognitive capacities in general are grounded in sensorimotor ones, we argue that mental procedures in particular are grounded in physical procedures, exhibiting known properties of grounding and procedures. For example, a mental procedure can be activated by engaging a physical procedure, and vice versa. Once activated, whether physically or mentally, a procedure can be applied across content domains, even in unrelated situations.

The specific category of grounded procedures relevant to cleansing effects is separation. Sensorimotor experience of cleansing involves separating one physical entity (e.g., dirt) from another (e.g., one's hands). This experiential basis can ground mental separation of one psychological entity (e.g., failure) from another (e.g., one's self). Consistent with principles of mental construal (Bless & Schwarz, Reference Bless and Schwarz2010), this attenuates or eliminates the influence of the separated entity.

3.2. Theoretical differences from existing accounts

Grounded procedures of separation complement rather than challenge the existing accounts. Acknowledging the roles of conceptual metaphor and disgust emotion in cleansing effects, the present account offers additional specificity and generativity in explanation and prediction.

First, a proximate mechanism is specified. Physical separation grounds mental separation, resulting in attenuation or elimination processes. This goes beyond stating that a conceptual metaphorical link exists between morality and cleanliness or that disgust is elicited by both immoral behaviors and dirty stimuli. The mechanistic explanation complements the evolutionary, developmental, and functional explanations.

Second, a procedure is applicable across content domains. The existing accounts are applicable to specific content domains (morality and disgust). They do not explain or predict cleansing effects in non-moral or non-disgusting contexts. A procedural account does.

Third, the procedure of separation generates novel predictions that cannot be derived from the existing accounts (cf. sections 4.1–4.5). For example, separation predicts that the psychological consequences of cleansing are not only domain-general, but also valence-general. Following a negative event, cleansing should separate it from the self to result in positive effects; following a positive event, cleansing should separate it from the self to result in negative effects. In contrast, the existing accounts assume domain-specific links that predict positive but not negative effects of cleansing as it confers a sense of morality or reduces feelings of disgust.

Fourth, separation is compatible with disgust without necessitating it. Disgust involves a powerful avoidance motivation and action tendency, and its signature “ew” facial expression (Ekman, Reference Ekman1993; Ekman & Rosenberg, Reference Ekman and Rosenberg1997; Tassinary, Cacioppo, & Vanman, Reference Tassinary, Cacioppo, Vanman, Cacioppo, Tassinary and Berntson2007; Vrana, Reference Vrana1993) serves “the function of oral-nasal rejection of aversive chemosensory stimuli” (Chapman, Kim, Susskind, & Anderson, Reference Chapman, Kim, Susskind and Anderson2009, p. 1223). Both avoidance and rejection help to separate disgust elicitors from the self. In other words, disgust involves the desire to separate, with downstream consequences (e.g., strengthening the desire to separate a product from oneself in economic decisions; Lerner, Small, and Loewenstein, Reference Lerner, Small and Loewenstein2004). But separation may or may not involve disgust. Non-disgusting things, whether physical (e.g., a piece of paper) or psychological (e.g., a thought), can be separated from the self (Briñol, Gascó, Petty, & Horcajo, Reference Briñol, Gascó, Petty and Horcajo2013a).

Fifth, the principle of grounding predicts methodological nuances different from those highlighted by the existing accounts. For example, sensorimotor capacities can be engaged to varying degrees (e.g., online experience, full-blown offline simulation, partial offline simulation). This predicts a gradation of strength in the effects of cleansing as a function of how fully sensorimotor capacities are engaged in the manipulation.

Overall, grounded procedures of separation serve as a “mid-range” account that allows for unique explanations and predictions. The proximate mechanism of separation has broader applicability than the conceptual metaphor Morality Is Cleanliness and the emotion of disgust. It also offers finer-grained specifications than the broad perspective of grounded cognition that inspired the present account. None of these, however, entails that grounded procedures are the only process at work in any given situation (for a discussion of other mental processes such as affect, accessibility, and validation, see section 6.2).

3.3. Falsifiability

For an account to be scientific, it needs to be falsifiable (Popper, Reference Popper1959/2005). Is the present one falsifiable? Our basic claim is that grounded procedures of separation serve as a proximate mechanism for cleansing effects. As a component of these grounded procedures, separation results in attenuation and elimination processes. All of these specifications can be formulated as falsifiable empirical questions, testable by experiments that sufficiently realize the theoretical independent and dependent variables (Schwarz & Strack, Reference Schwarz and Strack2014) and function as “forks” to generate alternative possible outcomes that afford strong inferences (Platt, Reference Platt1964, p. 347).

Are grounded procedures of separation a proximate mechanism for cleansing effects? It would be falsified if, for example, psychological consequences or antecedents of physical cleansing are not driven by a sense of mental separation. By implication, it would be falsified if physical cleansing does not confer any sense of mental separation, or if a sense of mental separation does not influence cleansing-related outcomes, or both. It would also be falsified if acts of separation, such as cleansing, do not result in any attenuation or elimination of an otherwise observed influence.

Are procedures grounded at all? It would be falsified if, for example, online experience of physical separation does not activate any thought or feeling about mental separation. Activation can be quantified behaviorally (e.g., word completion tasks, reaction time measures) and neuroscientifically (e.g., overlapping activation, repetition suppression). Another possible falsification is if the basic claim fails to generalize as expected. On one end of the equation, if mental separation is an active ingredient, it should be applicable to multiple psychological domains, producing domain-general effects. On the other end of the equation, if physical separation is an active ingredient, it should be instantiable not only by cleansing, but also by other physical acts of separation (e.g., discarding, enclosing). Failure to observe such generalizability would call the construct of grounded procedures into question.

4. Empirical support for grounded procedures of separation

Experimental tests of the falsifiable, unique predictions derived from the present account are reviewed in this section. As already noted, if grounded procedures of separation serve as a proximate mechanism for cleansing effects, cleansing should attenuate or eliminate the otherwise observed influence of a prior event (1) across domains and (2) across valences. Given the nature of grounding, (3) cleansing manipulations that engage sensorimotor capacities more strongly should produce stronger effects.

Turning the focus from psychological consequences to psychological antecedents of cleansing, we note the classic observations that avoidance motivation is typically triggered by negative stimuli and approach motivation by positive ones (e.g., Freud, Reference Freud1920; Kahneman and Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979; Mowrer, Reference Mowrer1960; Thorndike, Reference Thorndike1935; also Festinger, Reference Festinger1957; Heider, Reference Heider1958; Higgins, Reference Higgins1997). Accordingly, (4) motivation for cleansing as a procedure of separation should be triggered more readily by negative than positive entities. That is, although psychological consequences of cleansing should be domain-general and valence-general, psychological antecedents of cleansing should be valence-asymmetric.

Finally, to ascertain the generalizability of grounded procedures of separation, (5) conceptually similar effects should extend from cleansing to other forms of physical separation.

4.1. Psychological consequences of cleansing are domain-general

Psychological consequences of physical cleansing are not restricted to the realms of morality or disgust, but observed in a variety of non-moral, non-disgusting contexts. For example, in the domain of decision-making, after people make a free choice between two similarly attractive alternatives (e.g., music albums), they often wonder if they have made the right decision, experiencing postdecisional dissonance (Brehm, Reference Brehm1956; Festinger, Reference Festinger1957). Dissonance is aversive and instigates dissonance-reducing mental processes that focus on positive features of the chosen alternative and negative features of the rejected alternative. This results in a more positive evaluation of the chosen alternative and a more negative evaluation of the rejected alternative after choice than before choice, a signature effect called spreading of alternatives. A pair of experiments used this classic paradigm and found that the signature effect disappeared if a manipulation of physical cleansing was added right after choice and before evaluation (Lee & Schwarz, Reference Lee and Schwarz2010a). After freely choosing between two similarly desirable music albums, if participants were asked to actually use a bottle of hand soap (under the pretense of product evaluation), they showed no spreading of alternatives, but if they were asked to merely examine the hand soap, they did show the signature effect (Experiment 1). In a conceptual replication, participants freely chose between two similarly desirable fruit jams. Using an antiseptic wipe again eliminated the signature effect; merely examining the wipe did not (Experiment 2).

This finding was replicated with a German sample (Marotta & Bohner, Reference Marotta and Bohner2013). A conceptual replication with an American sample showed the same pattern and also found that it was moderated by individual differences (De Los Reyes, Aldao, Kundey, Lee, & Molina, Reference de Los Reyes, Aldao, Kundey, Lee and Molina2012). Specifically, postdecisional dissonance was “washed away” among participants low on intolerance of uncertainty, ruminative responses, and generalized anxiety, but not among participants high on these variables. A further boundary condition was found in a modified replication, which showed that postdecisional dissonance was not washed away when each participant was given memory cues about their own predecisional evaluation during their postdecisional evaluation (Camerer et al., Reference Camerer, Dreber, Holzmeister, Ho, Huber, Johannesson and Wu2018). A meta-analysis of all replications and original experiments showed a small overall effect (d = 0.204, SE = 0.084, p = 0.015, 95% CI 0.040/0.349) of washing away postdecisional dissonance (Lee & Schwarz, Reference Lee and Schwarz2018).

These results are consistent with our conceptualization of cleansing as a grounded procedure of separation. Cleansing attenuates or eliminates the residual influence of prior experience by separating it from the present. Similarly, having an opportunity to wash one's hands attenuated the residual influence of a recent academic failure on pessimism about one's future performance (Kaspar, Reference Kaspar2012). Similar manipulations of actual or simulated cleansing also attenuated or eliminated the residual influence of recent luck (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Zwick and Schwarz2012; also Moscatiello & Nagel, Reference Moscatiello and Nagel2014), endowment (Florack, Kleber, Busch, & Stöhr, Reference Florack, Kleber, Busch and Stöhr2014), ownership (Lee & Ji, Reference Lee and Ji2015), and stress (Kaspar & Cames, Reference Kaspar and Cames2016), none of which was related to morality or disgust. Instead, cleansing exerts its influence on whatever domain is salient to the person in a given situation.

This context sensitivity of cleansing effects is consistent with situated perspectives on mental processes (Mesquita, Barrett, & Smith, Reference Mesquita, Barrett and Smith2010; Smith & Semin, Reference Smith and Semin2004) and parallels the observation that feelings and metacognitive experiences are brought to bear on what is in the focus of attention at the time of the experience (Schwarz, Reference Schwarz, Mesquita, Barrett and Smith2010, Reference Schwarz, Van Lange, Kruglanski and Higgins2012). One implication is that cleansing prompted by a highly specific concern should have limited influence on unrelated concerns. Writing this paper during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, we expect, for example, that frequent hand washing during a pandemic attenuates concerns about infections and reduces the related stress, but does not leave people feeling less worried about unrelated decisions or less guilty about unrelated moral transgressions.

4.2. Psychological consequences of cleansing are valence-general

If cleansing serves as a grounded procedure of separation, and if procedures are applicable across domains, cleansing should be able to separate not only negative, but also positive experiences from the self. By implication, it should attenuate or eliminate the residual influence of experiences across valences. This can be tested empirically within a single domain or by surveying multiple domains.

Within the domain of luck-based risk-taking, as mentioned earlier, a positive experience like a winning streak tends to increase subsequent amounts of betting, whereas a negative experience like a losing streak tends to decrease them. A hand-washing manipulation eliminated the influence of a recent winning as well as a recent losing streak on subsequent betting (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Zwick and Schwarz2012, Experiment 2). Within the domain of performance-based self-evaluation, a positive experience like successful performance tends to increase optimism, whereas a negative experience like failing performance tends to decrease optimism. Using a product labeled as a hand sanitizer apparently attenuated the influence of a recent successful or failing performance on optimism (Körner & Strack, Reference Körner and Strack2019, Experiment 1).

Surveying multiple domains, cleansing has been shown to attenuate the residual influence of negative experiences such as immoral behavior (for recent reviews, see Lee and Schwarz, Reference Lee, Schwarz, Duschinsky, Schnall and Weiss2016; West and Zhong, Reference West and Zhong2015), postdecisional dissonance (Lee & Schwarz, Reference Lee and Schwarz2010a), academic failure (Kaspar, Reference Kaspar2012), and social and physical threats (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Millet, Grinstein, Pauwels, Johnston, Volkov and van der Wal2020b), as well as positive experiences such as product endowment (Florack et al., Reference Florack, Kleber, Busch and Stöhr2014), object ownership (Lee & Ji, Reference Lee and Ji2015), and successful performance (Körner & Strack, Reference Körner and Strack2019). These valence-general consequences of cleansing are consistent with the separation account. They complement accounts that assume cleansing is exclusively associated with removing negative influences in the form of moral impurities or feelings of disgust.

4.3. Engagement of sensorimotor capacities tracks strength of cleansing effects

Sensorimotor capacities are most strongly engaged in actual sensorimotor experience, less in mental simulation of it (e.g., imagined experience), and even less in partial offline simulation (e.g., semantic activation). Corresponding to these differences in engagement strength, actual cleansing behavior should exert stronger influence than imagined cleansing than merely conceptual activation of cleansing-related ideas. This prediction was addressed directly in the aforementioned meta-analysis (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Chen, Ma and Hoang2020a). It was found that actual cleansing manipulations produced significantly stronger effects than imagined or recalled cleansing manipulations, which still produced significantly stronger effects than manipulations that merely activated the concept of cleansing.

4.4. Psychological antecedents of cleansing are valence-asymmetric

If cleansing is a grounded procedure of separation, and if people are more motivated to separate negative than positive entities from themselves, cleansing-related outcomes should be elicited more readily by negative than positive entities.Footnote 4 Supportive evidence comes from experiments that manipulated negative versus positive experiences and measured cleansing behavior, desirability of cleansing products, or willingness to buy them.

For example, smelling a shirt that belonged to an outgroup (vs. ingroup) member increased participants' speed of walking to a hand sanitizer and likelihood of pumping it multiple times (Reicher, Templeton, Neville, Ferrari, & Drury, Reference Reicher, Templeton, Neville, Ferrari and Drury2016, Experiment 2). Telling a lie (vs. telling the truth) with one's mouth by leaving a voicemail message increased the desirability of mouth-cleaning products; similarly, telling a lie (vs. telling the truth) with one's hands by writing a note increased the desirability of hand soap products (Schaefer, Rotte, Heinze, & Denke, Reference Schaefer, Rotte, Heinze and Denke2015). Such evaluative patterns conceptually replicated similar effects in prior studies (Lee & Schwarz, Reference Lee and Schwarz2010b; also Denke, Rotte, Heinze, & Schaefer, Reference Denke, Rotte, Heinze and Schaefer2014) and were paralleled by heightened activation of somatosensory cortices after lying (vs. truth-telling). Beyond active experiences, passive experience such as being socially excluded (vs. included) in cyberspace also increased participants' willingness to buy cleansing products (but not their willingness to buy non-cleansing products; Poon, Reference Poon2019, Experiments 1 and 2). These experimental findings highlight that people have stronger motivation for cleansing after negative than positive experiences.Footnote 5

Dovetailing experimental data, superstitious behaviors abound across cultures where positive entities lead people to actively avoid cleansing. British fishermen, during a period of good catches, abstain from washing their nets, lest the luck would be washed away (Radford & Radford, Reference Radford and Radford2013). Chinese folk beliefs specify lucky days (e.g., lunar new year) on which people had better not wash anything (Fong, Reference Fong2000), or else they would be unlucky throughout the year. Gamblers and athletes keep wearing their unwashed socks and shirts during a winning streak, but do get changed after losses (Gmelch, Reference Gmelch1971; Vyse, Reference Vyse2013). The stink of soiled clothes is more bearable than the jinx of lucky essences, which people are disinclined to separate from themselves.

4.5. Other grounded procedures of separation exist beyond cleansing

Cleansing has been the most extensively investigated form of physical separation. Conceptually similar effects can also result from other grounded procedures of separation, such as movements away from the self or acts of enclosing.

A series of experiments showed that “actions that exert force away from one's representation of self” can reduce perception of misfortune after tempting one's fate (Zhang, Risen, & Hosey, Reference Zhang, Risen and Hosey2014, p. 1171). Participants were prompted to tempt fate by saying that they or their friend would never experience a particular bad outcome (e.g., getting in a horrible car accident during winter, getting sick, getting mugged). This increased participants' estimated likelihood of experiencing the jinxed bad outcome. But the increase was eliminated if participants were prompted to engage in an act of physical separation, whether it carried any cultural meaning (knocking down on a wooden table; Experiment 1) or not (throwing a ball away; Experiments 2a, 2b, 3, and 5). The elimination effect of physical separation was mediated by a reduction in mental image clarity of the bad outcome (Experiment 3). Importantly, the same elimination effect emerged if participants pretended to throw a ball away, which engaged the same motor action and proprioceptive experience as actually throwing a ball away, even though it did not create any spatial distance between the ball and oneself (Experiment 5). Thus, it was the sensorimotor experience of separation, not distance, that drove the effects.

Separation can also be instantiated without trying to throw anything away. Enclosing things in a container is sufficient to separate them from oneself. For example, after recalling and writing about a recent experience of regret, participants who were asked to enclose the written note in an envelope and return it to the experimenter (vs. simply return it to the experimenter without any envelope) felt less negative about the recalled event (Li, Wei, & Soman, Reference Li, Wei and Soman2010, Experiment 1a). The reduction effect of physical enclosure generalized to other negative events, such as an unsatisfied strong desire (Experiment 1b) and a tragic news story (Experiment 2), and was mediated by a sense of psychological closure (Experiment 3).

Similar effects have been found in the context of choice. After choosing a piece of chocolate from a tray of 24 options, participants were (vs. were not) asked to place a transparent lid on the tray (Gu, Botti, & Faro, Reference Gu, Botti and Faro2013, Experiment 1). This act of physical enclosure increased their sense of choice completion and their satisfaction with the chosen chocolate after tasting it, an effect that was mediated by less comparison between the chosen chocolate and the forgone ones. Note that even though the forgone options remained visible under the transparent lid, their influence was attenuated after enclosure. Conceptual replications found similar effects when participants chose a tea (Experiment 2) or biscuit (Experiments 3a and 3b) from a menu of 24 options and then closed (vs. did not close) the menu. Acts of physical enclosure enhance mental separation of the enclosed entities from the self.

In other cases, separation of an entity from the self is not initiated by the actor but signaled by features of the environment. For example, participants perceived lower risks of an earthquake about 200 miles away if they happened to be in a different state (vs. the same state), even though the distance was held constant (Mishra & Mishra, Reference Mishra and Mishra2010, Experiment 1). Similarly, participants perceived lower risks of a radioactive waste facility 165 miles away if they happened to be in a different state (vs. the same state), especially if the state border was salient (Experiment 2). Symbolic borders can cue mental separation of an entity from the self.Footnote 6

Inversely, if a symbolic cue signals to people that they are physically enclosed inside a task environment, the implied separation from the surrounding environment reduces distraction and increases task orientation (Zhao, Lee, & Soman, Reference Zhao, Lee and Soman2012). For example, customers waiting in line to reach an ATM (automated teller machine) were more likely to stay in line and complete the transaction (i.e., higher task persistence) if they were separated from the wider environment by a queue guide (a bright yellow line on the floor) than if they were not (Experiment 1). They also retrieved their ATM card sooner, indicating more immediate action initiation (Experiment 2). Business-class travelers waiting to check in at an airport counter took out their travel documents sooner if they were enclosed by a carpet that separated the queue from the wider environment (Experiment 2 follow-up). Perception of physical enclosure elicited an implemental mindset and its associated mental states of general optimism and action orientation (Experiment 3).

In short, physical enclosure confers a sense of mental separation between what is inside and what is outside. Consistent with the logic of mental inclusion/exclusion (Bless & Schwarz, Reference Bless and Schwarz2010), when an entity is enclosed and separated from where people are, its psychological impact is diminished. When an entity is enclosed in the same space as where people are, its psychological impact is amplified. This raises the question: Is there a broader class of physical experiences that generally amplify an entity's psychological impact?

5. Flipside of separation: Grounded procedures of connection

As a flipside of separation, grounded procedures of connection are observable. Physical connection involves linking one physical entity (e.g., a product) to another (e.g., one's hands). This experiential basis can ground mental connection of one psychological entity (e.g., an idea) to another (e.g., one's self), such that the connected entity becomes more representative of the target entity and relevant to it. As a result, the connected entity's influence on the target entity is amplified (if an influence already existed) or created (if no influence existed before).

Separation and connection share the structural properties of “grounding” and “procedure,” generating parallel predictions. As observed for grounded procedures of separation, different forms of physical connection should result in similar psychological effects. They should exert influence across domains and across valences, consistent with the domain- and valence-general applicability of procedures. Whereas acts of separation are more likely to be triggered by negative entities, acts of connection are more likely to be triggered by positive entities, reflecting the influence of avoidance versus approach motivation. The limited available findings support these predictions.

5.1. Psychological consequences of various grounded procedures of connection are domain- and valence-general

Physical connection can be instantiated in various forms, from visual continuity to motor approach to direct contact. For example, visually connecting several years of college experience into a continuous journey on a physical path accentuated students' sense of mental connection between their current and possible academic identities, thereby enhancing their academic intention, efforts, and final exam performance (Landau, Oyserman, Keefer, & Smith, Reference Landau, Oyserman, Keefer and Smith2014). Moving from the domain of academic motivation to that of health-related attitude, after participants wrote down positive or negative thoughts about the Mediterranean diet on a piece of paper, physically connecting the piece of paper to themselves (e.g., folding it and putting it in their pocket) amplified the influence of the written thoughts on their attitude toward the diet (Briñol et al., Reference Briñol, Gascó, Petty and Horcajo2013a, Experiment 2). Relative to control conditions, positive thoughts resulted in even more positive attitudes, and negative thoughts resulted in even more negative attitudes. Similarly, touching a robot (as opposed to merely looking at it) amplified pre-existing positive or negative attitudes toward robots (Wullenkord, Fraune, Eyssel, & Šabanović, Reference Wullenkord, Fraune, Eyssel and Šabanović2016).

Further attesting to the valence-general consequences of physical connection, consider sympathetic magic effects of contagion. Inspired by anthropological observations (Frazer, Reference Frazer and Frazer1890/1990; Mauss, Reference Mauss1902/2001), contagion is the notion that “people, objects, and so forth that come into contact with each other may influence each other through the transfer of some or all of their properties” (Nemeroff & Rozin, Reference Nemeroff and Rozin1994, p. 159). Physical contact results in psychological transfer of unseen “essence” from one entity to another. Early research on contagion focused on negative entities (e.g., disgusting and contaminating stimuli, immoral people's possessions; Rozin, Millman, and Nemeroff, Reference Rozin, Millman and Nemeroff1986), but contemporary research has also found contagion effects of positive entities (Huang, Ackerman, & Newman, Reference Huang, Ackerman and Newman2017).

In the context of product evaluation, participants evaluated a product less favorably if it had been touched by other shoppers (because of contamination concerns; Argo, Dahl, and Morales, Reference Argo, Dahl and Morales2006), but more favorably if it had been touched by a highly attractive person of the opposite sex (Argo, Dahl, & Morales, Reference Argo, Dahl and Morales2008). Similarly, in the context of object valuation, positive contagion of invisible essences can drive people's willingness to pay a fortune for objects once owned by significant individuals (e.g., celebrities, politicians, religious leaders), an effect that is amplified by prior physical contact between the object and its owner (Bloom & Gelman, Reference Bloom and Gelman2008; Newman & Bloom, Reference Newman and Bloom2014; Newman, Diesendruck, & Bloom, Reference Newman, Diesendruck and Bloom2011).Footnote 7 In the context of self-perception and behavior, touching a ball that had been touched by an outstanding athlete increased participants' perception of their own athleticism (Kramer & Block, Reference Kramer and Block2014), and using a golf club that had been used by a professional golfer increased participants' golf performance (Lee, Linkenauger, Bakdash, Joy-Gaba, & Profitt, Reference Lee, Linkenauger, Bakdash, Joy-Gaba and Profitt2011).

Theorists have typically assumed contagion of positive entities to be driven by the transfer of essence and contagion of negative entities by the behavioral immune system (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Ackerman and Newman2017; Murray & Schaller, Reference Murray, Schaller, Olson and Zanna2016; Schaller & Park, Reference Schaller and Park2011). Although these approaches offer valence-specific accounts, the perspective of grounded procedures interprets positive as well as negative contagion effects as a valence-general influence of the same underlying process. Acts of physical connection such as physical contact can ground mental connection between entities, thereby amplifying the influence of one entity on another, regardless of whether the influence is positive (e.g., the influence of John F. Kennedy on bidders' valuation of his golf clubs) or negative (e.g., the influence of Adolf Hitler on people's reaction to his sweater).

5.2. Psychological antecedents of connection are valence-asymmetric

Whereas the consequences of physical connection are valence-general, its antecedents are valence-asymmetric, paralleling the case of grounded procedures of separation. Reflecting the desire to approach the positive and avoid the negative, people are more motivated to connect with positive than negative entities and to separate from negative than positive ones.

For example, participants responded faster to positive stimuli by pulling a lever toward themselves and faster to negative stimuli by pushing the lever away (Chen & Bargh, Reference Chen and Bargh1999). Participants preferred a choice set in which objects were close to (rather than far apart from) each other if one unidentified object in the set possessed a positive quality, but preferred a choice set with the more distal spatial arrangement if the unidentified object possessed a negative quality (Mishra, Mishra, & Nayakankuppam, Reference Mishra, Mishra and Nayakankuppam2009). Culturally, every lunar new year, many traditional Chinese visit the temple and enact an elaborate routine: They receive a commemorative coin, touch the gold ingot, walk around the incense burner clockwise three times, touch the beard of the god of wealth, and leave the temple blessed with traces of financial luck for the rest of the year (Dai, Reference Dai2018; Wang, Reference Wang2018). They are taught to hold their hands above the incense burner for purification and sanctification prior to touching their favorite god (Liao, Reference Liao2018). In other words, they need to separate the bad luck before connecting the good luck to themselves.

Motivation for connection can also be triggered by a combination of two negatives, as in the desire to connect a negative attribute to a negative target. For example, a voodoo doll gives a non-present hated target a material form, allowing knives and needles to damage his specific organs. Throwing darts at photos of an enemy accomplishes similar goals. So does “villain hitting,” a cultural heritage in Hong Kong (TOPick, 2016), most commonly targeted at detested colleagues and business partners. After putting the name, date of birth, and photo or clothing of the target on what is called the villain paper, a professional villain-hitter is paid to beat the paper with a shoe, incense sticks, or other symbolic weapons, while pronouncing the following (translated into English; “Villain Hitting,” 2018):

“Beat your little hand,

Your good luck comes to the end.

Beat your little eye,

Very soon you die.

Beat your little foot,

Everything is no good.

Beat your little mouth,

You always have bad result.”

5.3. Interplay of physical and mental connection

By conferring a sense of mental connection between two entities, physical connection can amplify a pre-existing influence (as seen above), or it can create an influence where none existed. Because people typically see themselves in a positive light (Baumeister, Reference Baumeister1999), physically connecting a neutral entity to oneself creates positive evaluation of it. Consider examples of motor approach, which can occur in oral, visual, and manual modalities.

Articulating words that start with a consonant at the front of the mouth (e.g., B, M) and end with a consonant at the rear of the mouth (e.g., G, K) resembles oral muscle movements during deglutition (oral approach), as opposed to expectoration (oral avoidance). Participants preferred such inward words over their outward counterparts (which start with G or K and end with B or M), even though the consonants were neutral on their own and identical in both conditions (Topolinski, Maschmann, Pecher, & Winkielman, Reference Topolinski, Maschmann, Pecher and Winkielman2014). The effect generalized across nonsense words, company names, and person names (Experiments 1–8) and was found among English and German speakers – but not among aphasia patients who lacked subvocalizations (Experiment 9), highlighting the role of oral sensorimotor processes (for a review of further evidence, see Topolinski, Reference Topolinski2017).

Positive effects can result not only from an entity moving toward the self (e.g., inward words), but also from the self moving toward an entity. In the visual modality, cues of forward movement (vs. non-forward movement or no movement) increased participants' implicit positivity toward the concept of achievement (Natanzon & Ferguson, Reference Natanzon and Ferguson2012, Experiment 1) and improved their performance on word puzzles (Experiment 2). In the manual modality, mere flexion (vs. extension) of arm muscles generated proprioceptive feedback of motor approach (vs. avoidance) and increased participants' favorable evaluation of neutral ideographs (Cacioppo, Priester, & Berntson, Reference Cacioppo, Priester and Berntson1993) and neutral nonwords (Priester, Cacioppo, & Petty, Reference Priester, Cacioppo and Petty1996). Actually touching an object (i.e., direct physical connection) or seeing imagery that encouraged touching it (i.e., simulated physical connection) increased both buyers' and sellers' perceived ownership of the object (i.e., psychological connection), which increased its valuation (Peck, Barger, & Webb, Reference Peck, Barger and Webb2013; Peck & Shu, Reference Peck and Shu2009).

Similarly, online shopping on touch-based devices (e.g., tablet), as opposed to non-touch-based devices (e.g., laptop), elicits a higher degree of perceived ownership of products, again increasing their valuation (Brasel & Gips, Reference Brasel and Gips2014). Perceived ownership and valuation also tend to be higher for physical than digital goods (Atasoy & Morewedge, Reference Atasoy and Morewedge2017). Extremely high valuation (e.g., millions of dollars) is ascribed to objects once owned and touched by beloved significant individuals, but not to replicas that look identical but have not been touched by the owner (Bloom, Reference Bloom2010; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Diesendruck and Bloom2011). Valuation decreases if the original object has been cleansed and sterilized (Newman & Bloom, Reference Newman and Bloom2014). In contrast, valuation increases if people have experienced social exclusion (Newman & Smith, Reference Newman and Smith2016), which increases the desire for social connection.

These patterns are compatible with the notion that physical connection between two entities forges mental connection between them. Physical connection can occur in multiple modalities. One entity can be the self or a public figure. The other entity can be a word, an ideograph, or an object. Mental connection can create or amplify the influence of one entity on the other.

6. Some open questions raised by grounded procedures of separation and connection

Grounded procedures of separation and connection constitute a proximate mechanistic account for findings from studies that were motivated by multiple perspectives, such as conceptual metaphor, disgust emotion, sympathetic magic, positive contagion, and embodied attitude. Beyond offering interpretive parsimony and predictive scope, grounded procedures open up conceptual and empirical questions for investigation.

6.1. Do different forms of cleansing differ in their psychological consequences?

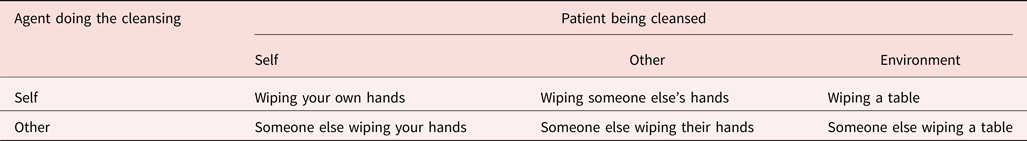

In most experimental manipulations of cleansing (e.g., hand-washing), the self is both the agent and patient of cleansing. In real life, other agent–patient combinations are possible (Table 1). Which combination exerts the most robust effects? Theoretically, effects should be more robust when self (vs. other) is the agent, because self-initiated cleansing directly engages sensorimotor capacities recruited for separation, whereas observing other-initiated cleansing may activate mirror neurons (Rizzolatti & Craighero, Reference Rizzolatti and Craighero2004), with likely weaker effects than taking the action oneself (Barsalou, Reference Barsalou2008). Effects should also be more robust when self (vs. other or the environment) is the patient, because physical entities are saliently separated from one's body.

Table 1. Examples of cleansing involving different agents and patients

These predictions have only been addressed indirectly. For example, wiping one's hands was more effective than watching someone else wipe their hands, which in turn was more effective than a neutral control, in attenuating the influence of one's prior immorality on one's guilt and compensatory prosociality (Xu, Bègue, & Bushman, Reference Xu, Bègue and Bushman2014). Wiping one's hands also eliminated the influence of one's prior success and failure on one's signature size; wiping a board did not (Körner & Strack, Reference Körner and Strack2019, Experiment 2). Comprehensive tests of the agent–patient combinations will add useful data to fill the empirical gaps in Table 1.

Even with the same physical action, however, different construals can highlight different salient attributes, resulting in different effects. For example, when a white emulsion was presented to participants as a hand sanitizer (thus evoking the notion of cleansing), using it attenuated the influence of prior success and failure on present optimism; but when it was presented as a hand lotion (thus lacking cleansing connotations), using it had no psychological effect (Körner & Strack, Reference Körner and Strack2019, Experiment 1). Outside the lab, mental construal of cleansing is manifest in fascinating ways. For example, the Ganga River in Allahabad, India is one of the five most polluted rivers in the world, receiving over a billion liters of raw sewage every day (Zerkel, Reference Zerkel2013). Yet it remains one of the holiest destinations for Hindus, which “plays host every dozen years to the Kumbh Mela, the biggest gathering of humanity on Earth, when tens of millions of pilgrims come to wash away their sins” (Morrison, Reference Morrison2011). The sacred power of a disgusting river cannot be underestimated. Neither can the role of mental construal in physical cleansing.

Closer to home, a cluster of popular beliefs and practices ride on the mental construal of inner cleansing. From tea and capsules for “Detox & Cleanse” (https://amzn.to/2PzThKQ) to recipes of “juice fast” and “clean eating” (https://amzn.to/2Pyb7hm), consumers construe these as whole-body events, flushing toxins out of their biological system.Footnote 8 As a parallel, inner cleansing of the immaterial soul is key to penitence among the religious. A 35-day Bible reading plan called Soul Detox (Life.Church, n.d.) is introduced thus: “While the world rightly teaches us to detox our bodies, sometimes we need to detox our soul…. You will learn from God's Word how you can neutralize these damaging influences and embrace clean living for your soul.”

Do construals of inner cleansing exert stronger effects than outer cleansing, because they separate negative entities from a person's inner essence and offer more thorough purification of the whole being? Are these cultural beliefs and practices more popular among adults and children high on psychological essentialism (Gelman, Reference Gelman2004; Medin & Ortony, Reference Medin, Ortony, Vosniadou and Ortony1989)? Do they predict religiosity, or are they predicted by it? Is inner cleansing more appealing to those who subscribe to an ethics of convictions (“Gesinnungsethik”; Weber, Reference Weber1919), which emphasizes thoughts and intentions, than to those who subscribe to an ethics of responsibility (“Verantwortungsethik”), which emphasizes the consequences of actual behavior? Would these differences be observable as differences between religions that put differential emphasis on thoughts versus acts (Cohen, Siegel, & Rozin, Reference Cohen, Siegel and Rozin2003)? Empirical answers await.

6.2. What further mental processes can result from cleansing as a procedure of separation?

The studies we reviewed indicate that physical cleansing can attenuate or eliminate – that is, partially or fully reduce – the otherwise observed influence of a prior experience. Such effects have been observed across diverse domains (section 4.1) and for influences of positive and negative valence (section 4.2). Many authors assume that cleansing reduces the intensity of an affective response, such as the intensity of one's guilt in response to recalling a moral transgression (e.g., Zhong and Liljenquist, Reference Zhong and Liljenquist2006), one's doubts after a decision (Lee & Schwarz, Reference Lee and Schwarz2010a), or one's concern after performing poorly on an academic test (Kaspar, Reference Kaspar2012). Reduction in affective intensity can occur by separating the eliciting event from the psychological present. This predicts that cleansing should reduce transfer of affective value from the separated entity to the judgment target (cf. Clore and Schnall, Reference Clore, Schnall, Albarracín, Johnson and Zanna2005), reduce cognitive accessibility of the separated entity (cf. Higgins, Reference Higgins, Higgins and Kruglanski1996), reduce concreteness or vividness of its mental representation (cf. Kross, Ayduk, and Mischel, Reference Kross, Ayduk and Mischel2005; Libby and Eibach, Reference Libby, Eibach, Olson and Zanna2011; Trope and Liberman, Reference Trope and Liberman2010), and reduce feelings of certainty (cf. Clore and Parrott, Reference Clore and Parrott1994) or confidence/validity (Briñol et al., Reference Briñol, Petty and Wagner2011, Reference Briñol, Petty, Santos and Mello2017b) about the separated entity. It should also help people move on with a fresh start (Dai, Milkman, & Riis, Reference Dai, Milkman and Riis2014; Price, Coulter, Strizhakova, & Schultz, Reference Price, Coulter, Strizhakova and Schultz2017).

In most examples of attenuation and elimination effects, both the eliciting event before cleansing and the outcome variable after cleansing are closely related to each other and to an important facet of the self (e.g., guilt about one's unethical act is related to the moral self, concern about one's poor performance is related to the competent self). When the eliciting event and outcome variable are less closely related to each other and to an important facet of the self, separating them by cleansing can result in contrast effects. For example, recalling a past episode of personal financial bad (as opposed to good) luck decreased MBA students' subsequent tendency to choose a risky option in a vicarious managerial investment decision. However, a hand-wiping manipulation reversed this influence, resulting in more risky choices on the vicarious managerial task after recalling previous bad luck on a personal task (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Zwick and Schwarz2012, Experiment 1; for a conceptual replication, see Moscatiello & Nagel, Reference Moscatiello and Nagel2014, Experiment 2).

Cleansing experiments thus far have demonstrated many more attenuation and elimination than contrast effects. From the perspective of mental inclusion/exclusion (Bless & Schwarz, Reference Bless and Schwarz2010; Schwarz & Bless, Reference Schwarz, Bless, Martin and Tesser1992), contrast effects are particularly likely to emerge when the eliciting event is used as a standard of comparison (“that was just bad luck, but this is good investment”). Progress in understanding the process conditions under which cleansing facilitates comparisons and reverses (rather than attenuates or eliminates) the influence of a prior experience will also enhance our general understanding of assimilation and comparison effects in judgment.

6.3. What are the psychological antecedents of various forms of physical separation?

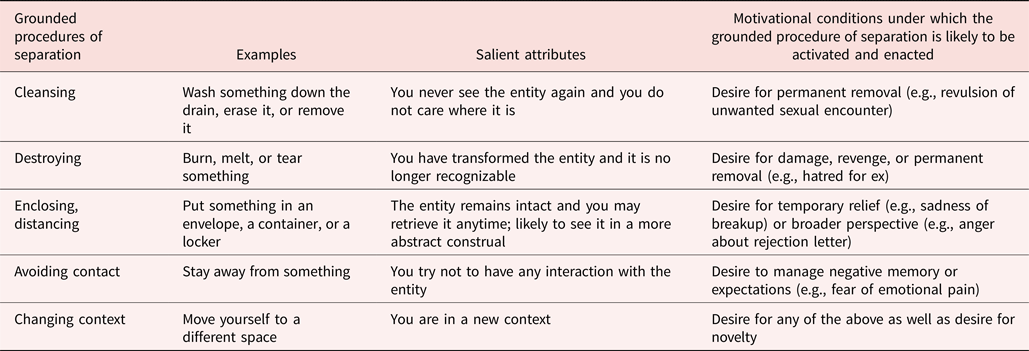

Separation can take different physical forms. Little is known about what variables favor the selection of some grounded procedures of separation over others. In other words, what antecedents determine which procedure comes to mind and is turned into action in a particular context? We offer some conjectures.

Different physical procedures involve different salient attributes that lend themselves to different shades of meaning and function (Table 2, column 3). We expect that a particular physical procedure is most likely to be activated and enacted when its salient attributes fit the person's current motivational condition (Table 2, column 4). Different physical procedures also differ in the extent to which they hinge on visible representation of the separated entity. For example, people can cleanse themselves of invisible germs (e.g., taking a shower), but can only destroy or enclose something with a material form (e.g., burning a letter, shattering a memento). Accordingly, mental separation of invisible psychological entities (e.g., painful memory) is likely accomplished either by cleansing or by first visualizing them as tangible representations (as in the popular pseudoscience “neuro-linguistic programming”; Bandler and Grinder, Reference Bandler and Grinder1975) before enclosing or destroying them.

Table 2. Different grounded procedures of separation, their examples, salient attributes, and motivational conditions for activation and enactment

Furthermore, some physical procedures have strong content associations with specific emotions. For example, cleansing is closely related to disgust (Landau, Reference Landau2017; Lee & Schwarz, Reference Lee, Schwarz, Duschinsky, Schnall and Weiss2016; Rozin et al., Reference Rozin, Millman and Nemeroff1986; West & Zhong, Reference West and Zhong2015). Destroying may be seen as a form of aggression, which is linked to anger (Averill, Reference Averill1983; Berkowitz, Reference Berkowitz1990). Situational and individual differences in these emotions (e.g., anger proneness, disgust sensitivity, obsessive concerns with contamination) are likely to predict the activation and enactment of the corresponding grounded procedures of separation.

6.4. Does separation contribute to religious and political associations with cleanliness?

If separation plays a key role in cleansing effects, it may contribute to associations of cleanliness with morality and related sociocultural phenomena such as religiosity and politics. For example, the apostle Paul exhorted Christ-followers to “cleanse ourselves from all defilement of flesh and spirit, perfecting holiness in the fear of God” (2 Corinthians 7:1, NASB). To be holy, tellingly, is to be “set apart” (Hebrew 10:10, GW) – to be separate – from failing ways of the world, for pursuing higher orders of God's kingdom. The sense of separation is also reflected in other biblical characterizations of religious purity (e.g., “put off your old self” and “put on the new self”; Ephesians 4:22 and 4:24, NIV).