Opera was produced only rarely in the otherwise vibrant theatrical culture of seventeenth-century Spain and her American dominions, though Italian operas and occasional Spanish ones became a mainstay of public life in the Spanish-held territories in Italy, especially Naples and Milan. At the royal court in Madrid and the principal administrative centres of the overseas colonies (Lima and Mexico), opera was inextricably bound to dynastic politics and constrained by conventions about the gender of onstage singers. Several other kinds of plays with music were produced at theatres both public and private, however, and commercial theatres known as corrales were among the busiest sites of musical performance and cultural transmission. Some 10,000 plays were performed in Madrid in the course of the seventeenth century, although only about 2,000 such texts have been preserved. The principal theatrical genre was the comedia nueva, a three-act play in poly-metric verse in which the tragic and the comic were mingled to recreate the natural balance of human existence with varying degrees of verisimilitude.

From the last decades of the sixteenth century, the Spanish royal court enjoyed spectacle plays with music; partly sung mythological semi-operas and mythological or pastoral zarzuelas were produced beginning in the 1650s. These hybrid genres called for more singing than did the standard comedia, although their incorporation of music was shaped by concerns about the power of musical expression and the ease with which different types of songs could mark the social status, intentions, or nature of the characters onstage.1 The most definitive of the Spanish musical-theatrical conventions separated divine and mortal discourse, so that in the semi-operas and zarzuelas, the gods and goddesses generally sing in the heavens, speak to each other when they are on earth, and sing especially lyrical airs (tonos and tonadas) to influence the mortals. The mortal characters, who do not have supernatural power, also lack the power to sing in the same fashion as the gods. They converse in spoken declamation and sing appropriately mortal songs – common romances, bailes, or musical settings of well-known poems of the day – in verisimilar situations, just as do ordinary characters in the comedias. This necessary distance between gods and mortals both mirrored the rigid social hierarchy of the monarchy and conditioned the Spanish approach to musical theatre, including opera.2

The First Opera in Spanish

The first opera performed in Spain, La Selva sin amor (Filippo Piccinini and Bernardo Monanni [music lost]; poetic text by Félix Lope de Vega Carpio; Madrid, salón grande of the Alcázar, 1627), was put together by Florentine diplomats at the Madrid court of Philip IV who were hoping to gain some political advantage for the Medici while securing a lucrative position for the stage architect and artist Cosimo Lotti, who had been sent to Madrid from Florence. Lotti designed a series of remarkable visual effects for a short pastoral eclogue, with a prologue and seven scenes (some 700 lines) contributed by the esteemed dramatist Lope de Vega. Lope appears to have studied Florentine pastoral libretti by Ottavio Rinuccini that circulated in print; his Spanish libretto, La selva sin amor, is entirely in the Italian poetic metre suitable for recitative (lines of seven and eleven syllables), except for the short ensemble coros in the octosyllabic metre typical of Spanish song-texts. Because none of the Spanish court composers in this early part of Philip IV’s reign were familiar with opera, or even the cantar recitando of Italian accompanied monody, the Florentine diplomats drafted Filippo Piccinini (d. 1648), the Bolognese lute player who was among the king’s favourite chamber musicians, as their composer. Piccinini was reluctant, pointing out his dearth of experience with recitative and begging assistance from a secretary with the Tuscan delegation, an amateur musician named Bernardo Monanni. Indeed, letters to the grand duke’s secretary in Florence describe the whole project as ‘an embassy undertaking’, hardly surprising since Monanni contributed music for the two longest scenes.

La selva sin amor was performed twice behind closed doors for the royal family in December 1627. A few years after its performance, Lope’s text was published in an anthology of his work with a prefatory letter describing the performance. The dramatist reported that he felt ‘rapture’ at hearing his poetry in song, while Lotti’s spectacular visual effects and fast changes of scene triumphed over all else. The opera did not arouse any other recorded praise or criticism. This experiment in fully sung opera after the model of the Florentine pastoral operas did not establish opera in Madrid.3 Further, La selva sin amor seems also to have been Madrid’s only seventeenth-century production of an opera by a non-Spanish composer.

The Marquis del Carpio and Partly Sung Productions

Spectacle plays with ensemble songs had become a feature of private celebrations for the royal family at royal palaces and during their sojourns at the country estates of high-ranking aristocrats such as the Duke of Lerma in the early seventeenth century. But opera did not grow from or evolve out of these. In contrast, the partly sung mythological plays, zarzuelas, and two fully sung operas produced at the royal court in the mid-seventeenth century were a direct response to the challenges that opera presented in the Spanish system of theatrical production. Partly sung entertainments were organised quite deliberately by a young aristocrat, Gaspar de Haro y Guzmán (1629–1687), known as the Marquis de Heliche (also Liche, Eliche, Licce) and later by his title as Marquis del Carpio (see Figure 14.1). Carpio was the son of Luis Méndez de Haro y Guzmán, Philip IV’s valido or first minister, who played a decisive role in European politics as principal representative of the Spanish crown in the negotiations toward the Peace of the Pyrénées and the marriage of Louis XIV to the Infanta María Teresa of Spain. At a relatively young age, Carpio inherited wealth, art, and a large and excellent library. He became the ‘foremost private collector’ of paintings in Europe in his time, if only for the quantity he possessed, and was a patron of contemporary artists.4 He was a zealous producer of musical theatre whose creativity and organisational verve were recognised by his contemporaries, though his contributions to the history of opera in Madrid and Spanish Naples have sometimes been overlooked in modern scholarship.5

Figure 14.1 Gaspar de Haro y Guzmán (1629–1687), Marquis del Carpio. Pencil and ink drawing, unnamed artist, in Mamotreto o Índice para la memoria y uso de Juan Vélez de León, ms. c. 1683, E-Mn, MSS/7526, fol. 1r.

Carpio took charge of the royal court’s entertainments at a crucial moment, c. 1650, after the reopening of Madrid’s theatres following several years of national mourning for the deaths of Philip IV’s first wife, Isabel (Elisabeth of France), in 1644, and his only male heir, Prince Baltasar Carlos, in 1646. Philip was married by proxy to his fourteen-year-old Austrian niece, Mariana, in 1647. Following her arrival in Madrid, Carpio spared no expense, entertaining her and supplying the court with all manner of diversion, from the nautical serenades performed by boatloads of musicians on the lake of the Buen Retiro, to staged performances of comedias, zarzuelas, and semi-operas at the several royal palaces, to the hunting parties on the grounds surrounding the Pardo and Zarzuela palaces that he arranged to invigorate the king. He supervised the renovation of the Coliseo theatre in the Buen Retiro palace and was an especially demanding producer of musical machine plays with daring effects, such as the semi-operas La fiera, el rayo y la piedra (1652) and Fortunas de Andrómeda y Perseo (1653) with text by the court dramatist Pedro Calderón de la Barca (1600–1681) and music most likely by Juan Hidalgo de Polanco (1614–1685). In the loa (prologue) to this work, the character of La Música outlines the most distinctive convention of the partly sung genre when she explains to Pintura (painting) that ‘the deities that you introduce must have a different harmony in their voice than that of the mortals; for it is better that the gods do not speak as the mortals do.’6 Songs for the zarzuelas and other partly sung plays, especially later ones such as Los celos hacen estrellas (Juan Vélez de Guevara, 1672), are scattered among an array of loose scores, performing parts, and anthologies, generally without notated instrumental parts beyond a bass line or minimal tablature for harp or guitar.7 Many of the songs call for improvised embellishment; most are strophic (easier for the actress-singers to learn quickly) but contain both declamatory coplas and more lyrical, subjectively expressive estribillos. Players of harps and guitars composed, arranged, and directed theatrical music, but seem not to have worked from staff notation. Musicians of all types in the Spanish realms were famous as expert improvisers, but theatrical musicians in particular provided music quickly, with little rehearsal time.

Partly sung genres endured even beyond the lifetimes of those who collaborated during the formative decade of the 1650s, and zarzuelas first organised by Carpio were repeatedly revived after his departure from the court. Many practices established by Calderón and Hidalgo became standard, but a few sources from the final years of the seventeenth century evidence changes in attitude and procedure. Among them, Destinos vencen finezas (1699) – a zarzuela on the story of Dido and Aeneas, with poetry by Lorenzo de las Llamosas and music by Hidalgo’s pupil, Juan de Navas (c. 1650–1719) – is the first printed score of a Spanish theatrical work and the first music issued by the new Imprenta de Música in Madrid.8 This beautiful volume is innovative in several ways, most especially because it includes the spoken verse, in addition to what was sung, and instrumental parts beyond the bass. Navas’s solo vocal pieces register the durability of Hidalgo’s approach to setting the poetry, but notated parts for violins, ‘viola de amor’, viols, oboes, bassoon, and clarines reveal new practices at work. Tradition and modernity are fused in the final chorus of Destinos vencen finezas, ‘Hagan la salva’, an ‘ocho con todos los instrumentos’, calling for five groups above the basso continuo – two vocal choirs, parts for two clarín trumpets, an ensemble of violins, and a group of four oboes. Navas’s vocal writing for the two choirs, one slightly higher than the other, is reminiscent of Hidalgo’s in Celos aun del aire matan (libretto by Calderón; Madrid, Coliseo del Buen Retiro, 6 June 1661). Although it was partly sung, this was a royal ‘fiesta’ performed by a large cast (twenty roles) for the 6 November birthday of Carlos II in 1698 and organised by a ranking aristocrat, the Marquis de Laconi (Juan Francisco de Castellví y Dexart). It may be that Maria Anna of Neuburg, Carlos II’s second wife, to whom the printed score is dedicated, encouraged changes in the court’s theatrical music in the last years of the century. The pan-European musical taste of leading court aristocrats returning from their postings abroad was an essential catalyst for change,9 coinciding with performances by or collaboration with foreign musicians brought to the Madrid court in the last decades of the seventeenth century.10

Fully Sung Opera for Royal Celebrations

Opera was reserved for the most significant court celebrations, though partly sung ‘fiestas’ were usually offered on royal birthdays and onomastic days at the royal court. The extensive rehearsals required for fully sung theatre taxed the system of theatrical production in Madrid, which depended on the rapid preparation of new plays for the public theatres. Singers from the acting companies normally were busy preparing almost daily performances in the corrales (singers from the Spanish royal chapel did not perform onstage). Yet Carpio chose to produce fully sung opera to showcase the court’s elegance in its commemoration of two political and dynastic events of heightened importance, though musical theatre at the mid-century did not somehow ‘evolve’ toward fully sung opera, Italianate vocal styles, or Italianate approaches to setting Spanish texts. Well aware that the French were planning to produce an opera by Francesco Cavalli (1602–1676) and were building a new theatre to house it, Carpio commissioned two operas from Calderón and Hidalgo. In 1659–1661, these operas commemorated a long-desired treaty and the most important dynastic alliance of the century – the signing of the Peace of the Pyrénées, and the marriage of the Infanta María Teresa to Louis XIV of France. Note that the Spaniards did not import an opera (as the French did) or invite a foreign composer to Madrid. Hidalgo’s score for the first of these operas, La púrpura de la rosa (probably 17 January 1660), has not been found, though a few pieces from it appear in other manuscript sources.11 The surviving music for La púrpura de la rosa, composed or compiled in Lima (Peru) by the Spanish composer Tomás de Torrejón y Velasco (1644–1728) in 1701, includes music from Hidalgo’s 1659–1660 setting (see ‘La púrpura de la rosa in Madrid and Lima’).12 The second Hidalgo opera, the three-act Celos aun del aire matan, is the earliest extant Spanish opera for which a complete score is preserved.13 The two manuscripts for Celos, together with the music for La púrpura de la rosa from Lima, and the music copied into the special presentation manuscript of Fortunas de Andrómeda y Perseo, are the only bound manuscript musical scores for individual theatrical works from the period.

The one-act La púrpura de la rosa explored the story of Venus and Adonis to celebrate the treaty between Spain and France (signed on 7 November 1659); some of it may well have been heard during the visit of the Marshal-Duke of Gramont in October 1659 when he visited Madrid to request the hand of María Teresa on behalf of Louis XIV. All of the roles except that of the comic gracioso Chato (most likely a tenor) and the figure of Desengaño (a baritone in the Lima manuscript) were sung by young female actress-singers. Hidalgo’s three-act Celos aun del aire matan was the pendant to La púrpura de la rosa and drew a similar cast from two conjoined acting companies. Both operas pour forth with extraordinary lyricism and sound strikingly concordant, though tragic consequences unfold when amorous harmony is disturbed by neglect, jealousy, and vengeance.14

Carpio produced these operas before he had visited Italy or experienced opera of any kind in performance, though he learned about the genre from his correspondents in Italy. During the years in which the Roman librettist Giulio Rospigliosi (1600–1669; the future pope Clement IX) served as papal legate in Madrid (1644–1653), the Italian stage architect and engineer Baccio del Bianco (Luigi Baccio del Bianco 1604–1657) reported that Rospigliosi was eager to introduce recitative, but had made little progress because the Spaniards were sceptical about the effectiveness of ‘speaking in song’.15 In 1653 Hidalgo had experimented with a Spanish kind of recitative in Fortunas de Andrómeda y Perseo. A few years later, del Bianco, always opinionated concerning the pre-eminence of Italian music, even attempted, unsuccessfully, to teach Hidalgo to compose an Italianate lament for the nymph Canente, the female protagonist in the court pastoral Pico y Canente (text by Luis de Ulloa y Pereira) in 1656. Hidalgo found a more tuneful and concordant vehicle for declamation than mid-century Italian recitative, thus effectively inventing Spanish recitado. In Celos aun del aire matan, Hidalgo did not employ Italianate recitative; instead, together with recitado, soaring melodies caress the ear in the flowing musical textures of strophic tonos and persuasive declamatory tonadas.

Celos aun del aire matan in Madrid and Elsewhere

Celos is not only the first extant Spanish opera, but the most significant musical-theatrical work to survive from the vibrant culture of the Spanish siglo de oro. In Celos, Calderón and Hidalgo transformed the ancient myth of Cephalus and Procris, such that chastity is dethroned by the power of womanly desire. The date and site of performance for the première of Celos aun del aire matan have often been assumed to be December 1660 or January 1661 at the Alcázar palace, but this date may be ruled out due to the fact that three of the actress-singers listed in the opera’s printed cast list (reparto) were in France entertaining María Teresa at this time (their company did not return to Madrid until April 1661).16 As for the location, it is unlikely that Carpio would have chosen to present the opera at the Alcázar palace, where the most visually spectacular scenes would have been difficult to stage in the smaller space and with the limitations of the dismountable theatre. The Coliseo at the Buen Retiro, whose design he had supervised, is the site named in the libretto, and it was fully equipped with the necessary tramoyas (machines for stage effects). The likely date of the Celos première is 6 June 1661, when a ‘fiesta grande’ with stage machines was performed there after a dedicated period of rehearsals. A letter sent from Madrid by an Italian diplomat confirms that this fiesta was Celos aun del aire matan, stating ‘the day before yesterday the performances began for the opera in musica called Procri in the large theatre of the Retiro.’17 Performances of Celos for an enthusiastic public continued until the beginning of the feast of Corpus Christi. The opera was revived in Madrid in 1679, with the involvement of both Hidalgo and Calderón, and again in 1684 and 1697.

Both La púrpura de la rosa and Celos aun del aire matan received private and public performances in Madrid, and both can claim to have been heard in more diverse locations than most Italian operas of the age. Celos travelled beyond Madrid, at least as far as Naples, and probably to Vienna and Mexico, thanks to a web of political and dynastic relationships among Habsburg and Spanish representatives in far-flung diplomatic posts. The score of Celos was sent to Vienna, though it may not have been performed there. The Spanish court regularly sent plays and theatrical songs to Habsburg cousins (the presentation manuscript of Fortunas de Andrómeda y Perseo is just one example). Celos is mentioned several times in letters during the time that the Infanta Margarita was emperor Leopold I’s consort.18 The emperor requested the music of Celos aun del aire matan for Margarita probably because she had appreciated its Madrid première. The first Spanish play performed for her in Vienna was not Celos, however, but Calderón’s play Amado y aborrecido instead, probably because the Spanish opera would have required more Spanish-speaking female actress-singers than were available at the imperial court.

Celos aun del aire matan served as an epithalamium for a very reluctant bride when it was performed in Naples in 1682 to honour an aristocratic marriage between the Roman Princess Lavinia Ludovisi and the Neapolitan Duke of Atri, from the Acquaviva d’Aragona family. This dynastic alliance was designed to fortify the Spanish cause and reinforce Spanish territorial claims in Italy. The bride’s brother, Prince Giovanni Battista Ludovisi, produced the opera in his apartments within the Castel Nuovo.19 The large audience that filled his theatre was delighted by the costumes, staging, and overall quality of the production. The opulent staging was rumoured to have cost ‘an almost royal sum’. But the opera was ‘otherwise not in the best taste because it was done with Spanish music, and, as a consequence, was tedious’. The strophic tonos and tonadas composed by Hidalgo just over twenty years earlier naturally sounded old-fashioned in Naples in early 1682, especially compared to the music of the opera that had just been presented by the viceroy for the queen mother’s birthday in December 1681 – Alessandro Scarlatti’s (1660–1725) Gli equivoce nel sembiante.

La púrpura de la rosa in Madrid and Lima

The performance history of La púrpura de la rosa shows just how closely this opera was associated with dynastic alliances, especially those between Spain and France. Its performances in January 1660 (apparently first at the Zarzuela palace and then at the Buen Retiro) were arranged to honour the Peace of the Pyrénées and the engagement between María Teresa and Louis XIV.20 It was revived in Madrid to commemorate the announcement of the marriage by proxy between Carlos II and Marie-Louise d’Orléans in performances that began on 25 August 1679, following rehearsals that had commenced before 11 August, ‘both mornings and afternoons’ in spite of the heat.21 Carlos II and his bride met near Burgos, on 19 November 1679, but the bride’s public entry at Madrid was delayed due to the official mourning after the unexpected death of Prince Juan José de Austria on 17 September. Rehearsals for another revival of La púrpura de la rosa began on 6 January 1680, and the opera was performed on 18 January, the birthday of the Habsburg Archduchess Maria Antonia, following the new queen’s formal entry on 13 January. These revivals, supervised by Calderón and Hidalgo, included a number of singers and musicians who had participated in the opera’s 1660 première.22 It is significant that this fully sung epithalamium on the overtly erotic mythological story of Venus and Adonis was performed by a nearly all-female cast to welcome the new queen, whereas a number of the spoken plays performed within the court’s celebrations treated chivalric and heroic themes. La púrpura de la rosa was revived yet again at court in 1690 and 1694, presumably with Hidalgo’s music (as was the case with revivals of a number of other plays).

It is remarkable that we know anything at all about opera in the American colonies governed by Spanish viceroys and their ecclesiastical counterparts, because the history of music in colonial Mexico and Latin America has so often focused on the implantation of the music of the Catholic Church, such that the musical ‘history’ of the colonies has been steered by this evangelising project.23 Nevertheless Hispanic opera as shaped by Calderón and Hidalgo travelled to the Spanish territories at the behest of aristocrats with the political power and the financial resources to produce it.24 La púrpura de la rosa was the first opera of the Americas, produced in December 1701 in Lima (Peru) for the eighteenth birthday and first year of the reign of the first Bourbon King of Spain, Philip V.25 Philippe d’Anjou, grandson of Louis XIV, had been proclaimed King of Spain in Madrid on 24 November 1700. The Spanish-French alliance in this case was not a marriage, but the enthroning of a Bourbon king. Official accounts of the coronation and the local celebrations in many cities were published across the geography of the Spanish empire. The news reached Lima on 9 September 1701, and Lima’s official commemoration took place on 5 October 1701, more than two months before the opera performances. The viceroy, Melchor Portocarrero y Lasso de la Vega, third Count of Monclova (1636–1705), was reported to have scheduled Lima’s official acclamation without waiting for the official instructions to arrive; according to the published relación, he recognised the ‘general and public joy’ that the loyal citizens of Lima felt at such ‘happy news’.26 It was essential that the city project a positive description of its punctual acclamation.27 La púrpura de la rosa was not part of the official acclamation, because the time-worn protocols for such demonstrations of fealty had been invented well before the invention of opera. Theatrical performances in Lima (at the public Coliseo and the viceroy’s court) had been suspended during the period of mourning following the death of Carlos II, but the opera rehearsals as well as plans for the reopening of the public Coliseo apparently commenced with the news of Philip V’s accession. Because so many female solo singers were called for, actresses from two of Lima’s acting companies probably were recruited to perform together in 1701.

The manuscript of La púrpura de la rosa is the most extensive single collection of secular vocal music from colonial Peru.28 Its title page characterises the opera as a ‘representación música’ and ‘fiesta’ composed or compiled by (‘compuesta por’) Tomás de Torrejón y Velasco (bap. 23 December 1644–1728), the Spanish-born chapel-master at Lima cathedral. The anonymous poetry of the opera’s 1701 loa proclaims “¡Viva, Felipo, viva!”, voicing Lima’s symbolic reception of the new king in a brilliant chorus. Tunes from the Lima manuscript appear in Spanish sources with attribution to Hidalgo, so it likely contains at least some music from Hidalgo’s now lost La púrpura de la rosa composed in 1659,29 though it is unclear just how Hidalgo’s opera (or sections of it) reached Peru. Both Torrejón and the Count of Monclova received letters and packages from Madrid, so either may have possessed music from La púrpura de la rosa before 1701. Torrejón had lived most of his adult life in Peru after travelling there in 1667 at the age of twenty-two as a gentleman of the chamber in the large retinue of the tenth Count of Lemos when that grandee was appointed nineteenth Viceroy of Peru. Before this journey, he had surely received musical instruction while serving as a page in the house of Lemos and Andrade.30 He may even have accompanied the grandees as their page when they attended the first production of La púrpura de la rosa in Madrid. Given the influence and standing of these patrons, Torrejón’s teacher may well have been Hidalgo.31

The opera’s performances in Lima are described in a printed newsletter offering the first operatic criticism published in the Americas:

The king’s eighteen years, like the flowers of youth, are the first ones to be celebrated by the faithful recognition and truly Spanish loyalty of these dominions. On this day of public rejoicing, the City turned out in full-dress, and the nobility adorned the finery on its breasts with diamonds in gallant respect of its sovereign. His Excellency [the viceroy], in whom the generous flame of adoration for his King burns most brightly, attended all the demonstrations of his most dedicated observance; in the morning, with the Royal Audiencia, Courts, and Cabildo, he attended the solemn Mass that was sung in the Cathedral for the health and life of our King … . That night, in one of the patios of the palace, La púrpura de la rosa was performed, an elegant composition by D. Pedro Calderón, all in music, and performed with excellently skilled voices and rich display in the costumes, stage apparatus, perspective scenery, machines, and flights … . His Excellency paid the greatly swollen expenses of this fiesta, as well as those of the bullfights, with his usual inexhaustible generosity.32

This printed notice conveys the generic quality of an official report, praising the skilful singers, rich costumes, perspective scenery, movable sets, and stage machines – in other words, it conforms to what was typical of such notices about opera elsewhere in this period. The success of the enterprise is attributed largely to the viceroy’s financial investment, but the name of the famous (and by 1701 long deceased) royal court dramatist, Calderón, is offered proudly as a guarantor of the opera’s pedigree. Musicians were rarely acknowledged when their music was heard in Spanish court productions, and even the names of composers were rarely attached to opera libretti and printed notices in seventeenth-century Italy. But it is still somewhat surprising that Torrejón’s name is left off, given his pre-eminence and the circulation of his sacred music (especially his vernacular villancicos) in Latin America. If he actually composed the opera, rather than merely compiling the manuscript, the opera would be his only extant secular composition.

In Torrejón’s lifetime, a certain tension separated music that was defined as cultivated, correct, clean, and appropriate (contrapuntal polyphony setting religious texts) from a profane music associated with or suspected of low habits, dubious morality, and confusing looseness. This separation between correct music copied onto paper and preserved by the Church and music that was conspicuously not preserved in written form must be acknowledged as having shaped the context into which opera was introduced in Lima. Profane music of whatever species, but especially street music and dances (given their capacity to communicate by gestures, without texts or the mediation of an ‘authorised’ translation), was excluded early on from what might be termed the record of official culture, most likely because it could slip past and flourish outside ecclesiastical control. Festive public musical activity typically was generated within or around religious spaces in Lima, a city replete with churches and convents. But the central musical practices that infused performance with identity at all social levels were largely unwritten – rhythmic and timbric conventions, stylistic gestures, bass patterns, modes of embellishment, and vocal production all passed along via oral tradition. The tunes and rhythms of secular songs and dances also brought their associated meanings into pieces such as La púrpura de la rosa and the many vernacular sacred pieces whose manuscripts now lie collected in ecclesiastical archives.

Barely any comment about musical interpretation and technique has been transmitted to us from colonial Peru, with the exception of a few references in treatises and instruction books written by Spanish musicians and published in Spain.33 Many performers in the Americas, especially the indispensable players of guitar and harp, did not read mensural or staff notation fluently, though Torrejón surely did. The notation of the Church’s contrapuntal polyphony (canto de órgano) was the notation of learned musicians. Seventeenth-century theatrical musicians did not need it because they improvised, and, in most cases, harpists, guitarists, and even keyboard players worked from tablature or cifra when they used written music at all. Profane songs and bailes – the very stuff of Hispanic opera – resided in musicians’ memories and bodies, and in the tunes, patterns, and gestures upon which they improvised. Thus, although the project of fully sung opera was without precedent in colonial Lima, it was possible thanks to the ability of Lima’s improvising theatrical musicians and actress-singers. The music (whether by Torrejón, Hidalgo, or some admixture of the two) incorporates familiar, conventional gestures and patterns from a common Hispanic practice. The actress-singers learned their roles by rote; the opera’s unfolding in reiterative sections of tuneful strophes made it easier to fashion affective shadings and ornamentation expressive of Calderón’s elaborately Baroque poetry. Musicians in Lima shared well-known tunes, skills, and practices very similar to those Hidalgo’s ensemble had deployed a half-century earlier in Madrid.

La púrpura de la rosa was a royal opera revived in the far distant locations of Madrid and Lima to celebrate dynastic alliances. Given his long service to the Habsburg cause, Monclova’s choice of opera in Lima was extraordinary because he had already supported the requisite public acclamation of the Bourbon Philip V. By 1701 he had served in the colonies for twenty-two years, most of them in a Lima he termed ‘la contera del mundo’ (the furthest edge of the world). His official correspondence concentrates on military and administrative matters, the funds needed to restore the city, and the zealous pursuit of pirates, but private letters express nostalgic longing for the culture of the Madrid court of his youth. He surely remembered the many entertainments that Carpio had organised, and he might have attended the first productions of both the Calderón–Hidalgo operas in 1660–1661. It is extremely likely that he had heard the 1679–1680 revival performances of La púrpura de la rosa in Madrid because the nobility were called to court for the celebrations following the marriage of Carlos II and in honour of the new queen. Monclova followed Carpio’s example in producing this fully sung opera for a dynastic occasion. Moreover, just as the public entered the Coliseo theatre in the Buen Retiro palace and the theatre installed in the Palazzo Reale in Naples (see ‘Italian Opera in Spanish Naples’), so Monclova opened the temporary theatre in his palace courtyard to the populace for La púrpura de la rosa.

Italian Opera in Spanish Naples

Naples was the administrative centre of the Spanish territories in Italy and, like Lima, was ruled by successive viceroys whose terms varied in duration. These representatives of a far-away sovereign changed so frequently that ‘it was very difficult or even impossible to establish consistent patterns of patronage’, as Fabris has noted,34 and, with few exceptions, the interests and investments of individual viceroys have not yet been studied carefully. Some Spanish operas were performed in Naples before the eighteenth century, but the first thirty years of opera’s history in this crowded musical metropolis unfold as the story of how interested patrons, producers, composers, and performers worked to create stable practical, financial, and political conditions for Italian opera. Italian opera is rightly understood as an instrumentum regni in Naples – though, with so many viceroys and shifting relationships within Neapolitan society, it is often unclear how individual operas or productions served or were exempt from the exigencies of the Spanish imperial program.

The viceroy who first brought opera to Naples, Iñigo Vélez de Guevara, eighth Count of Oñate (1597–1658), arrived from Rome in 1648 and encountered a Naples partly in ruins and with a starving populace after the ten-month Revolt of Masaniello against his tyrannical predecessor. Oñate was genuinely interested in theatre, but his highest priorities were the rebuilding of the city and renovation of the Palazzo Reale. Propagandistic festivities he ordered in summer 1649 culminated in a partly sung but elaborately staged series of tableaux, the Trionfo di Partenope Liberata, Recitato in Musica nel Palazzo Reale, ostensibly offered to celebrate the passage through Italy of Mariana de Austria, the young bride of Philip IV.35 Of course, inviting the nobility to his palace allowed Oñate to shift their focus of interaction, diverting the nobles from their ingrained practice of staging theatricals independently and behind closed doors. Most of the operas in the first series he financed, beginning with Didone, ovvero L’incendio di Troia (between September and November 1650), were by Cavalli and performed by a company led by the Venetian theatrical engineer Giovan Battista Balbi (fl. 1636–1657). Oñate invited Balbi and his Febiarmonici to Naples in order to produce operas as elaborately as possible with innovations that might draw the nobility to his palace.36

Oñate imported opera to Naples as a complete package performed by a company from elsewhere (‘comici forastieri italiani, chiamati Febi armonici, che rappresentano in musica’) that stayed on after their first season with his direct financial support.37 Their December 1652 production of Cavalli’s Veremonda ‘per ordine di Sua Eccellenza’ in the Sala Grande of the Palazzo Reale had clear political intent.38 First planned as a dynastic celebration for the Queen of Spain’s birthday, it took on deeper shades of political meaning after the victory of the royal troops at Barcelona, though the victory could not have been foreseen when the opera was composed and rehearsed.

The calendar of opera productions in Naples was variable in the early years, but, after the death of Philip IV in 1665, opera increasingly responded to a closer association with dynastic celebration, the same association that motivated musical plays and operas elsewhere in the Spanish empire. Opera production was funded to honour the Spanish monarchy and encourage its fecundity. But the genre’s fortunes were not guaranteed in Naples before the 1680s precisely because opera did not appeal to every Spanish viceroy. Many other kinds of public and private entertainment (the cabalgata, fireworks and maritime displays, equestrian games, carnival processions, processions on saints’ days, Spanish comedias, and the Neapolitan commedia) were already institutionalised by protocol, religious observance, taste, or tradition. For example, the Count of Peñaranda (Gaspar de Bracamonte y Guzmán 1595–1676) preferred Spanish plays, so ‘comedias ‘all’uso di Spagna’ were performed frequently during his time as viceroy by a Spanish company he paid to retain at the palace.39 When the traditional ‘gala’ ceremony for the nobility was held on Prince Felipe Próspero’s birthday at the palace in November 1659 (during Peñaranda’s reign), no opera seems to have followed it. Likewise, when the nobility rode in a torch-lit procession with over one hundred riders to celebrate the Peace of the Pyrénées in the first week of December 1659, they were treated afterward to a traditional ‘festino a ballo’, not an opera. A Venetian opera, L’Eritrea, was staged a few weeks later on 26 December at the viceroy’s palace for the invited nobility, but its Neapolitan libretto carries a dedication signed by ‘Gli Armonici’ to Antonio Fonseca, Count and Marquis del Vasto, Captain of the Guards, perhaps implying that it had already been performed at the public theatre with his sponsorship.40

Some degree of collaboration between the royal palace, site and symbol of the monarchy, and the public theatre was essential to opera’s survival in Naples, but reliable mechanisms of production did not develop immediately. As was characteristic elsewhere in the Spanish dominions, theatrical impresarios were obliged to serve the palace, though they mostly did so with financial and material contributions from the viceroys who sponsored opera on two royal birthdays. The season began with the 6 November birthday of Carlos II (b. 1661, prince and later king); a second opera was designed for the 22 December birthday of Mariana de Austria (queen and later queen mother). The December opera most often continued into January at the public theatre, but in some years it did not even receive its première until early January, despite the 22 December dedication date printed in the libretto. Prior to 1696, the first performance or two of each opera was a protocoled event for the nobility and invited officials at the palace. Sometimes public performances continued at the palace, but most productions instead began at the palace and then were moved to the public Teatro di San Bartolomeo following their premières. During the short Neapolitan carnival, one or two operas were staged, but, before 1696, nearly all of them opened with a protocoled performance at the palace. Premières sponsored by the viceroy were the scaffold each season in an enduring political and financial relationship between Italian opera and representatives of the Spanish monarchy.

Opera in Naples was at once private and public, available to the invited nobility and then to anyone who could pay for a seat at subsequent performances. Prior to 1668, for example, performances were offered to the paying public in the Gioco della Pilotta attached to the palace (also known as the teatro del Reale Parco or the Pallonetto), a space that may have reminded Spaniards of their corrales.41 Later on, operas produced inside the palace were sometimes public. During the 1680 carnival, for example, the Naples revival of Giovanni Legrenzi’s (1626–1690) Eteocle e Polinice at the palace drew such crowds that second and third performances were added. The palace was opened to the public in this way because the opera was among the events celebrating a royal marriage, a ‘festivity celebrating His Majesty, the King and should thus be enjoyed by all of his subjects’.42 A similar sentiment had inspired the public revivals of La púrpura de la rosa in Madrid and Lima. A few years later, in a shrewd but typically generous move, Carpio allowed Alessandro Scarlatti’s L’Aldimiro an expanded series of palace performances in November 1683 because the theatre at the palace première had been overflowing. People crowded in, hungry for novelty and with high expectations because L’Aldimiro was a new opera and the first of Carpio’s first season; it would feature music by Scarlatti with special effects designed by Filippo Schor, and its cast included newly recruited singers.43

Beyond the palace, opera as a commercial venture was tested with varying degrees of financial and artistic success. The Santa Casa degli Incurabili (which ran the hospital for the mentally ill) held a monopoly on public commercial theatre, so its permission was required before tickets to any public performance could be offered for sale.44 The Teatro di San Bartolomeo had been built in 1621 as a venue for spoken plays but reconditioned on Oñate’s orders in 1652 with the investment of the Santa Casa. Following the Spanish model, a portion of the proceeds from the rental of theatre boxes supported this charity. Carnival was the most lucrative period in the Venetian operatic schedule, but the carnival in Naples was shorter, so carnival operas at the Teatro di San Bartolomeo had limited runs and thus could be more costly to produce. Drawing singers to Naples was another challenge, given the city’s location at some distance from the operatic circuit in Northern Italy (Venice, Modena, Mantua, Bologna, Florence, etc.) where it was easier and less expensive for singers to travel.

The Venetian operas brought to Naples before the reign of the Marquis del Carpio were performed either by previously contracted itinerant companies or by a group of performers dubbed ‘Febi Armonici’ or just ‘Armonici’ but collected in Naples under the auspices of a performer or theatre manager. The series of libretto dedications signed by the stage architect and impresario Gennaro delle Chiave might indicate that the ‘musici del teatro publico’ worked as a stable company under his management. But notices about the performers are scarce, except for those about the infamous singer and prostitute Giulia De Caro, who had managed the company in 1673–1675, thanks to protection from the corrupt and gluttonous Viceroy Astorga and other lovers.45 Most of the evidence suggests that operas by local composers were performed by local singers. But the frequent mention of ‘musici forastieri’ recruited by the viceroys or their agents points back to the plan devised by Oñate with Balbi. Little is known about contacts or agreements with agents or performers in Rome, Genoa, and Palermo, for example, probably because musicians, singers, and actors earned little and held such low social status. Naples was full of busy musicians and singers, thanks to its numerous noble palaces and churches, and the training offered in its conservatories, but the rule that singers in the Neapolitan royal chapel (a Spanish royal chapel) were prohibited from performing onstage proved an impediment to the organisation of opera productions for much of the viceregal period. Chapel singers, whether in Madrid or Naples, were not trained to sing onstage and were not encouraged to rub elbows with the likes of those who did, given the anti-theatrical prejudice. Nevertheless, three castrati from the chapel were forced to sing in La Dori, the first opera production sponsored by Viceroy Marquis de los Vélez in November 1675, in observance of the king’s birthday. ‘One or another of the castrati’ (‘Ogn’altro virtuoso eunuco’) joined the cast, alongside singers from the ‘teatro mercenario’ because the chapel singers reportedly could not shrug off the viceroy’s order.46 Significantly, for carnival 1676, the viceroy instead paid travel expenses and a subsidy to import an opera troupe from Rome.47 Musicians from the royal chapel performed in Il Teodosio for the royal birthday the following November in the Sala dei Vicerè at the palace, and, if the diarist Fuidoro’s report is accurate, their performance was open to both the nobility and other social strata.48

Operas designed originally for Venetian theatres and publics were subject to revision in Naples, but titles alone do not reveal the extent to which libretti and scores were reshaped and recomposed for the theatres, casts, and public in Naples, or how local musicians such as Filippo Coppola (1628–1680), Francesco Provenzale (1624–1704), and Severo de Luca (fl. 1684–1734); the chapel master Pietro Andrea Ziani (1616–1684); or visiting composers such as Giovanni Buonaventura Viviani (1638–1692) intervened. Provenzale is named as the composer and praised in the preface to the libretto to Il Theseo (Naples, 1658, with a dedication to the viceroy García de Haro [y Sotomayor] de Avellaneda, count of Castrillo), which also names him as the composer of ‘Ciro, Xerse, and Artemisia’, three previous operas that had ‘enticed’ the Neapolitan audience. It is likely that these titles represent three operas by Cavalli revised by Provenzale for Neapolitan production; much of Il Ciro was composed by Provenzale and ready for performance by Balbi’s company before the end of Oñate’s reign.49 Even several years after the hurried departure of Balbi’s company, Provenzale collaborated with a company constituted in Naples but called Febi Armonici (L’Artemisia and Il Xerse were staged at the palace in November and December 1657). A later maestro of the Royal Chapel, Ziani, may have revised his own Le fatiche d’Ercole per Deianira (Venice, 1662) when it was revived in 1679 to open the Neapolitan carnival. As seventeen years separated the Venetian and Neapolitan productions, and Ziani was already in failing health, it seems likely that Provenzale again contributed new music. The opera was extensively revised, according to Andrea Perrucci (1651–1704), dramaturge of the Teatro di San Bartolomeo, whose note to the reader explains that he had responded to local taste and modernised the Naples libretto, replacing aria texts from Venice with his new ones.50

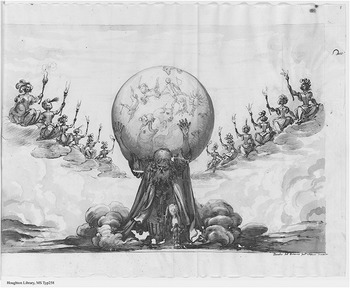

Scarlatti’s revisions to Legrenzi’ssss Il Giustino, carried out in collaboration with an unnamed poet (probably Perrucci or Giuseppe Domenico De Totis) for its 1684 Neapolitan production, point to a Spanish viceroy behind the scenes. First performed in Venice in 1683, Il Giustino was chosen for the king’s birthday and start of the opera season in Naples in November 1684.51 The opera began with a spectacular and lengthy new allegorical loa praising the Spanish monarchy, in which Atlas presides over the glorification of monarchy with arias and ensembles sung by four ancient rulers. The huge globe perched on Atlas’s shoulders is suddenly shaken by an earthquake and breaks into four pieces representing the four regions of the Spanish empire – Europe, Asia, Africa, and America. While a giant statue of Carlos II is thrust outward, Monarchy (a soprano) sings to praise the king and the Habsburg cause. Every visual and musical element of this prologue had obvious significance in the positive representation of Spain’s dominance. The allegory was absolutely typical of the Spanish stage, and Atlas was often associated with Carlos II. More striking is that all of these allegorical figures had appeared years before in loas that Viceroy del Carpio had produced in Madrid – Atlas in the loa to the semi-opera Fortunas de Andrómeda y Perseo (1653; see Figure 14.2), and the four festive choirs for the four parts of the empire in the loa to the zarzuela El laurel de Apolo that he produced in early 1658, for example. Beyond this loa, Il Giustino was given an enhanced staging with machines, effects, and sets designed by the viceroy’s hand-picked production team (Schor, Nicolo Vaccaro, and Francesco della Torre). Conforming to both the Spanish and Neapolitan comic traditions, brand-new scenes for two hilarious comic characters were added as well. Overall, Scarlatti tightened up the opera’s dramatic rhythm, strengthened the role of the female protagonist, and composed new arias and substitute arias for his cast, while retaining some of Legrenzi’s music. Il Giustino shows how an opera designed for Venice was revised for Naples to assert a viceroy’s personal and political agenda, raise the local standard of production, and delight local audiences. Not surprisingly, its long run of public performances at the Teatro di San Bartolomeo extended until mid-December.

Figure 14.2 Atlas in the loa to the semi-opera Fortunas de Andrómeda y Perseo, ink drawing, Luigi Baccio del Bianco, from Pedro Calderón de la Barca, Andrómeda y Perseo: fábula representada en el Coliseo del Real Palacio de Buen Retiro a obediencia de la Serenissima Señora Doña Maria Teresa de Austria Infanta de Castilla en festibo parabién que felices años goze la siempre Augusta Magestad de la Reyna Nuestra señora Doña Mariana de Austria, ms. c. 1653, US-CAh, MS Typ 258, fol. 8.

In the final decades of the century, the investment of two viceroys – Carpio and his nephew Luis de la Cerda y Aragón, ninth Duke of Medinaceli (1660–1711) – transformed Naples ‘from a way-post on the operatic itinerary into an operatic proving ground with high standards’.52 Before moving to Naples, both Carpio and Medinaceli had come to appreciate Italian singing and skilled operatic voices in Rome, and both understood how opera might enhance personal elegance while supporting the Spanish cause. Carpio, the same zealous aristocrat who had produced zarzuelas, semi-opera, and the two Hidalgo operas in Madrid, was the first Spanish viceroy to arrive in Naples with prior experience as an opera producer, though the genre of Italian opera had been new to him before his arrival in Italy and visit to Venice during carnival 1677. He was immediately decisive in Naples, folding opera into his plan for the modernisation of public life and changing the mechanisms for opera production there. Intent on showcasing the best performers available for his first season (1683–1684), he borrowed the famous alto castrato Giovanni Francesco Grossi (‘Siface’, 1653–1697) from the Duke of Modena and financed the recruitment of other singers from Rome and Bologna, some of whom he had heard in Rome. He assigned several opera singers to salaried chapel positions and brought Scarlatti to Naples as the new maestro of the chapel and composer for the operas. Scarlatti, the most fluent aria composer of the age, was born in Palermo and thus already a Spanish subject, so it is unsurprising that Carpio had been among his early patrons in Rome. Three of the new operas by Scarlatti for Naples – L’Aldimiro (1683), La Psiche (1684), and Il Fetonte (1685) – reflected Carpio’s personal history and were based on comedias by Calderón. Their allegorical loas revived favourite stage effects Carpio had featured in his Madrid productions years before. Both Carpio and later Medinaceli renovated or embellished theatres, installed their own productions teams and impresarios, recruited quality singers, and financed operas whose staging was innovative and exciting. It may not be coincidental that their productions occurred just as new urban guidebooks to the city’s attractions were issued; perhaps opera became one more reason for opera-loving tourists to visit Naples.

* * *

Two operatic paradigms – one formed in Madrid, the other in Naples – retained their vitality among musicians, audiences, and patrons in the Spanish dominions beyond the close of the Habsburg era. Opera in Spanish and the conventions of the partly sung zarzuela, invented through the collaboration of Calderón and Hidalgo, proved durable in revival, even if sometimes with newly composed music. The second operatic model, Italian opera as energised in Naples by Scarlatti with support from the last Spanish viceroys, brought Naples to operatic prominence. Both of these very different models seem to have travelled to the Americas in the early eighteenth century. The older paradigm, Hispanic opera, not only reached Lima when La púrpura de la rosa distinguished the celebration of Philip V’s birthday in 1701, but also was heard in New Spain when, apparently, Celos aun del aire matan was performed in Mexico to commemorate the same monarch’s birthday in 1728. According to a notice in the December 1728 Gaceta de México, the news of Philip V’s good health was carried over land and sea from Madrid via Havana and Veracruz before reaching Viceroy Juan de Acuña y Bejarano, Marquis de Casafuerte (1658–1734), in Mexico. The official birthday celebration began with the requisite pealing bells throughout the city, a mass of thanksgiving, and a Te Deum. Then royal, ecclesiastical, and municipal authorities gathered to attend three nights of protocoled performances of Celos aun del aire matan in the ‘sumptuous theatre of [the viceroy’s] royal palace’.53

Nothing is known about this production beyond what is stated in the Gaceta. It is possible that Celos was performed with Hidalgo’s music on this occasion since his tonos and villancicos circulated in New Spain. Italian opera also reached Mexico, when Silvio Stampiglia’s (1664–1725) La Partenope, drama in musica was performed there for Philip V’s birthday, according to the title page of an undated bilingual La Partenope libretto printed in Mexico sometime early in the eighteenth century with the Italian text and a Spanish translation on facing pages.54 A nineteenth-century bibliophile suggested 1711 as its date and listed an undocumented attribution to Manuel de Zumaya (also Sumaya; c. 1678–1755), a criollo composer and scholar who served as a singer, organist, and later chapel master at the cathedral in Mexico City.55 If Zumaya composed or compiled the opera’s music, no trace of his work has been recovered. Among the versions of Stampiglia’s libretto in circulation in the early eighteenth century, the text of the Mexico City libretto is closest to that of La Partenope set by Neapolitan composer Luigi Mancia for Naples in 1699, though with small variations.56 In New Spain during the early decades of the eighteenth century, theatrical singers were surely familiar with fashionable Neapolitan music, just as were their counterparts in nearly every European musical centre.57 Italian sonatas and Neapolitan arias were performed, absorbed, emulated, transmitted, and refashioned in the Atlantic world. The mellifluous siren queen Partenope was omnipresent as a symbol of Naples throughout the years of Spanish domination.58 With uncanny buoyancy, the Neapolitan siren reached the Atlantic world and Mexico through a network of Spanish aristocrats enamoured of opera.