I think it would not be useless … to recall to mind how and when such spectacles had their origin, which without any doubt, since they were received with much applause … , will at some time or other reach much greater perfection … all the more if the great masters of poetry and music set their hands to it.1

Acknowledging the experimental beginnings of opera and expressing high hopes for its future, Marco da Gagliano (1582–1643) thus reviews the origins of ‘such spectacles’ in the 1608 preface of his own first effort in the new genre, La Dafne, itself a reworking and expansion of the earliest completely sung music drama a decade earlier. He goes on to explain how, after a great deal of discussion concerning the way the ancients had represented their tragedies and about what role music had played in them, the court poet Ottavio Rinuccini (1562–1621) began to write the story (favola) of Dafne, and the learned amateur Jacopo Corsi (1561–1602) composed some airs on part of it. Determined to see what effect a (completely sung) work would have on the stage, they approached the skilled composer and singer Jacopo Peri, who finished the work and probably premièred the role of Apollo ‘on the occasion of an evening entertainment’ during the carnival of 1597/8 and on subsequent occasions. In the invited audience at the first performance were Don Giovanni de’ Medici and ‘some of the principal gentlemen’ of Florence.2

Gagliano, Florentine composer and maestro di cappella to the Medici court from 1609 until his death in 1643, provides a useful and accurate outline – despite the rivalries and counterclaims surrounding the events (about which more will be said) – of the immediate circumstances of opera’s modest beginnings, one that will serve well enough to organise our discussion.

Florentine Origins

His narration infers, first of all, that it was a completely Florentine affair. This is not surprising since Florence had a long tradition of musical theatre in the sixteenth century, manifested principally in the productions known as intermedi that were staged between the acts of spoken plays. These were but one of many different types of festivities mounted by courts all over Europe. But unlike other centres, Medicean Florence also had a particularly rich history of ‘civic humanism’3 – that is, of involvement by its more educated citizens in the rediscovery of and allegiance to Classical culture via a network of formal and informal academies that were engaged in critical inquiry and philological pursuits, which involved studying the Greek and Latin texts of the ancients. Moreover, as Gary Tomlinson and others have suggested, Florence was the centre of a particular Renaissance worldview that accorded music a ‘magical’ role in the cosmos and in man’s interaction with it.4 Before filling in some of the details of Gagliano’s outline, we shall examine each of these three elements – intermedi, humanism, and musical magic – in order to understand how their confluence at the end of the sixteenth century resulted in Florence becoming the birthplace of opera.

Intermedi

Extravagantly staged pageantry involving sumptuous costumes, special effects, music, dance, and song characterised the sixteenth-century Florentine intermedi, which were produced as entr’actes to a theatrical entertainment such as a comedy or pastoral play at court. Sets of intermedi were originally a modest and functional feature of North Italian court entertainments: they served to signal the divisions of the spoken drama, since there was no curtain to be dropped; and they suggested the passage of time by employing allegorical characters and themes unrelated to the main plot. At the court of the Medici rulers, however, intermedi evolved into an elaborately lavish type of spectacle, planned and rehearsed months in advance, whose cost and impact dwarfed that of the main drama and whose raison d’être was to leave no doubt in the minds of the audience – comprised entirely of invited guests gathered to help celebrate a special family event – about their host’s wealth and generosity.

Such an occasion was the marriage in 1589 of Grand Duke Ferdinando de’ Medici of Tuscany to the French Princess Christine of Lorraine, a union that had been in negotiation for nearly a year. The intermedi devised for this event climaxed a month-long sequence of public and courtly pageantry that mobilised the combined intellectual, artistic, and administrative forces of Tuscany at the height of its wealth, power, and cultural prestige. ‘Their splendor cannot be described’, wrote one court chronicler, ‘and anyone who did not see it could not believe it.’5 A huge team of artists, artisans, poets, musicians, architects, and technicians was assembled under the intellectual guidance of the prominent Florentine aristocrat and military leader Giovanni de’ Bardi (1534–1612), who formulated the underlying conception of the intermedi, served as stage director, and coordinated all the thematic and antiquarian aspects of the project.6 As the moving spirit behind the program, Bardi worked closely with the court poets, principally Rinuccini, who wrote most of the text.7 Emilio de’ Cavalieri (c. 1550–1602), the recently appointed superintendent of music at the ducal court who had been in Ferdinando’s retinue while he was still a cardinal resident in Rome, became the show’s musical director. The court architect-engineer Bernardo Buontalenti (c. 1531–1608), who only a few years earlier had constructed for the Medici the first permanent indoor theatre with a modern proscenium arch, remodelled it for the occasion, and designed the sets and costumes.8 The music was largely composed by court organist Cristofano Malvezzi and madrigalist Luca Marenzio, with individual contributions by the young composer-singer Jacopo Peri (1561–1633), by Bardi’s protégé Giulio Caccini (1551–1618), and by Bardi himself, among others. Note that both Rinuccini and Peri also figure in Gagliano’s narration of opera’s origins a decade later.

Bardi conceived the set of six intermedi as ‘a sort of mythological history of music’,9 fitting for a wedding celebration in that it depicts the descent of Harmony as a gift from the gods and predicts a new Golden Age initiated by the royal couple. Moreover, the individual tableaux are loosely unified by the literary theme of the power of music, a topic of longstanding interest to the Florentines (see ‘Musical Magic’). The opening intermedio contemplates the harmony of the spheres. The next, which represents the ancient rivalry between the Muses and the Pierides (nine daughters of King Pierus who challenged the Muses to a song contest), dwells on the virtues and virtuosity of song. The third, by enacting the combat between Apollo and the Pythic serpent, prefigures the opening scene from the Rinuccini-Peri Dafne about which Gagliano wrote. It thus introduces the first operatic hero, Apollo – god of music and of the sun, and some said father of the legendary musician Orpheus, who became in turn the protagonist of several early opera libretti. The fifth intermedio gave a prominent role to Peri, who composed and performed his first piece for solo voice to portray another musician-poet par excellence, Arion; according to myth, Arion was saved from drowning by a dolphin attracted by the dazzling power of his song. In the concluding allegory, harmony and rhythm are bestowed on mortals who, represented by the nymphs and shepherds of Arcadia, are instructed by the gods in the art of dancing during an elaborately choreographed ballo.

The 1589 intermedi had many of the same players and almost all the ingredients of opera – costumes, scenery, stage effects (for example, the life-size fire-spitting dragon slain by Apollo10), enthralling solo singing, colourful instrumental music, large concerted numbers, dance – everything except unified action and the innovative style of dramatic singing yet to be created. It remained for a few pioneering individuals to shape these elements into a new and quite ‘noble style of performance’11 that would, by emulating ancient theatre, revive the power of modern music to move the emotions.

Humanism

The catalyst for their experiments, as Rinuccini explains in his preface to the libretto for the first opera for which the music survives in print (Peri’s Euridice, 160012), was the belief by some scholars that the ancient Greeks and Romans sang their tragedies on the stage in their entirety.13 Although Renaissance scholars disagreed among themselves about the role of music in ancient tragedy, the amount of attention focused on the practices of the ancients was typical of humanism. Rinuccini, it seems, subscribed to a kind of Greek revivalism that Tomlinson has called ‘ordinary-language humanism’ – a view that underlay ‘the whole late-Renaissance exaltation of music’s affective powers’;14 indeed, it had been manifest in one way or another across the breadth of Renaissance musical culture in the degree of importance given to expressing the meaning of the text. While philological humanism promulgated the transmission, translation, and interpretation of ancient texts, and rhetorical humanism was built on the principles of persuasive oratory, this ordinary-language humanism placed greater emphasis on the ability of language itself – the very sound and shape of the words rather than the eloquence with which they were arranged – to communicate meaning and emotion.

Where did these ideas come from? Rinuccini belonged to the Alterati Academy – its very name (Academy of the Altered Ones) acknowledged the ability of ideas to effect change in human beings – one of a network of associations of artists and thinkers that flourished in Florence during the sixteenth century. Its membership included the widely read and accomplished Count Giovanni de’ Bardi, who was a member of long standing by the time Rinuccini was initiated in 1586, three years before they collaborated on the wedding festivities discussed above. Another member was the remarkable scholar Girolamo Mei (1519–1594), who, although Florentine by birth, worked in Rome and made known his ideas about Tuscan prose and poetry along with the results of his research into Greek music through correspondence with Bardi and other academicians. An erudite philologist, Mei developed theories about language that were in fact as central to the genesis of the new dramatic style of singing as his convictions about Greek music were to the origins of opera; for not only was it Mei’s belief that poems and plays were always sung in ancient times, whether by soloists or by the chorus, but also that they were sung monophonically so that the words as sounding structures could act on the listeners’ souls. Finally, the Alterati also counted among its members another Florentine nobleman, Jacopo Corsi, the enthusiastic amateur we first encountered in Gagliano’s preface, who partially composed, on Rinuccini’s text, and fully sponsored the production of the first completely sung ‘favola tutta in musica’, La Dafne, in 1597/8. These are some of the reasons that justify Claude Palisca’s having dubbed the Alterati of Florence ‘pioneers in the theory of dramatic music’.15

Now, Count Bardi also had his own circle of friends with similar humanist and musical interests, a more informal academy which met in his palace and came to be known as the Florentine Camerata.16 As the courtier chiefly responsible for organising entertainments for the grand duke, Bardi naturally became interested in theatrical or dramatic music and eagerly cultivated his long-distance relationship with Mei.17 These two, then, were key players in both the Alterati Academy and the Camerata, and it’s easy to see that both groups shared a concern with musical humanism. Bardi’s inner circle also included the singer-lutenist-composer Caccini (whom he involved in the 1589 intermedi) as well as Vincenzo Galilei (c. 1530–1591), another talented singer-lutenist-composer in his employ. Galilei, father of the revolutionary thinker and astronomer Galileo, had studied with the most famous counterpoint teacher of the age, Gioseffo Zarlino, and had already published a text on how to arrange polyphonic music for solo voice and lute (Il Fronimo, 1568), a medium that became increasingly popular during the last quarter of the century.18 Under the influence of Bardi and Mei, Galilei wrote a treatise that became the Camerata’s revolutionary manifesto, for it articulated the principles of ordinary-language humanism in the most radical way imaginable for a sixteenth-century musician: eschew vocal counterpoint altogether and adopt a type of non-polyphonic composition combining (texted) melody and simple accompaniment (which we now call monody).

Galilei published his inflammatory tract in the conventional Renaissance form of a dialogue – a conversation between two friends (one of whom is named after Count Bardi) debating the merits of ancient and modern music (Dialogo della musica antica e della moderna, 1581).19 By ‘modern music’ he meant the ars perfecta, the system of counterpoint he and all the leading composers of his day had learned, directly or indirectly, from Zarlino, whose Istitutione harmoniche (1558) was the foremost textbook for writing both sacred and secular music. Galilei challenged the ultimate perfection of counterpoint and advocated instead restoring through a single melody line the expressive powers of which ancient music was capable, judging by the corpus of literature about the Greek modal system that had been revived by Renaissance humanists and was recently newly interpreted by Mei.20 Why monophony? Because it alone was capable of imitating nature – that is, the ‘natural language’ of speech, through which a person’s character and states of soul are reflected. Mei had contended that ancient music always presented a single affection embodied in un aria sola (a single melody). He reasoned that monophony could convey the message of the text through the natural expressiveness of the voice – via the register, rhythms, and contours of its utterance – far better than the contrived delivery of a polyphonic texture.21 Like Mei, Galilei was persuaded that counterpoint was ineffective because it presented contradictory information to the ear. When several voices simultaneously sang different melodies and words – pitting high pitches against low, slow rhythms against fast, rising intervals against descending ones – the resulting web of sounds was incapable of projecting the semantic meaning or emotional message of the text. Only by returning to an art truly founded on the imitation of human nature rather than on contrapuntal artifice would it be possible for modern composers to approach the acclaimed power of ancient music.

Plato had taught that song (melos) was comprised of words, rhythm, and pitch, in that order. From that followed the humanist ideal of music and poetry as two sides of a single language, as well as the idea that song arose from an innate harmony within the words that was muted in normal speech. For this reason, Galilei advocated the art of oratory as a model for modern musicians, urging them to imitate the manner in which successful actors delivered their lines on stage:

Kindly observe in what manner the actors speak, in what range, high or low, how loudly or softly, how rapidly or slowly they enunciate their words … how one speaks when infuriated or excited; how a married woman speaks, how a girl, how a lover … how one speaks when lamenting, when crying out, when afraid, and when exulting with joy.22

For Galilei, it is clear that ‘how one speaks’ the words reveals their underlying emotion. For the composers of monody and theatrical song, by extension, it then became a question of ‘how one sings’ the words to disclose their innate significance.23

Twenty years Galilei’s junior, Caccini built his long career as a singer, singing teacher, and composer on these precepts, claiming to have learnt more from Bardi’s Camerata than from ‘more than 30 years of counterpoint’. After composing solo madrigals and airs with figured bass accompaniment and performing them for Bardi’s circle, where they were received ‘with warm approval’ in the 1580s, Caccini issued his pathbreaking collection of madrigals and airs in 1602 with the title Le nuove musiche (The New Music – more correctly translated as ‘musical works in a new style’).24 Caccini’s was the first set of composed and published monodies, as opposed to the improvised airs that had been ‘recited’ on formulas suitable for rendering sonnets, epic stanzas, and other fixed poetic forms during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries; in effect, the new pieces were frozen improvisations. The distinction of being composed also separates them from contemporary solo songs that were actually arrangements of polyphonic compositions. In addition to their new texture, Caccini’s works embody Galilei’s precepts in two more ways: they abjure the common manner and excessive use of ornamentation, and in melodic contour and rhythmic profile they approach the nuances of speech. In the first instance, Caccini was adamant about using ornamentation only to enhance the affections inherent in the text and melody. And, to approximate the flexibility of speech, he advocated that the performer apply his concept of sprezzatura – a sort of nonchalance or casualness of delivery – a concept he adapted from Baldassare Castiglione’s Il libro del cortigiano (Book of the Courtier, 1528), a meditation on the qualities necessary for the ideal Renaissance courtier to cultivate.25 Caccini’s innovations had a far-reaching impact on composers of monody in the early seventeenth century. However, once the theatre became the proving ground of the capabilities of modern music in the late 1590s, Caccini staked his claim to primacy in that arena by composing and rushing into print his own first music drama, L’Euridice (1601), in the wake of Peri’s and Rinuccini’s success.26

After Bardi moved to Rome in 1592, having been to some extent unseated at court by Duke Ferdinando’s new favourite, Cavalieri, the field was left open for the wealthy merchant Corsi to become the principal patron of music in Florence (after the Medici) and the standard-bearer of the experimental ‘movement’ in musical theatre.27 With Rinuccini, fellow academician in the Alterati, and Peri, he produced their first offering, La Dafne, in 1597/8.28 In contrast to the 1589 intermedi, performed before several thousand international guests, Dafne was a very modest affair. It first played in Corsi’s home for a comparatively few invited guests, among whom were ‘some of the principal gentlemen’ of Florence.29 It had the distinction, however, of being the first to include the dramatic style of singing now known as recitative. It was soon followed by L’Euridice (by Rinuccini and Peri, with some music by Caccini), performed in October 1600, as a small and fairly inconsequential part of the entertainments for the wedding festivities of Maria de’ Medici and Henry IV of France.30 Because Caccini would not allow the singers under his tutelage to perform Peri’s music, he inserted his own music for some of the roles. Meanwhile, Cavalieri was claiming the distinction of having composed and produced in 1595 the first completely sung ‘pastorals’ on texts by a different poet, Laura Guidiccioni (one with whom he had collaborated in the 1589 intermedi) – a claim which Peri generously acknowledged in his preface to L’Euridice. But Cavalieri’s works are not extant, and, judging by the tuneful style of his later musical play, La Rappresentazione di Anima, et di Corpo, printed in 1600 and first performed in Rome, Cavalieri shared neither the academic perspective nor the humanistic, ordinary-language aesthetic of his Florentine peers.31 Still, such private rivalries among musicians were fuelled by the printers who promptly published their works and by the public competition among princes to garner attention with their patronage. These were some of the factors that fostered the endurance of the first completely sung musical tales and their spread to other urban centres – Mantua, Rome, Venice, and elsewhere, both inside and outside the Italian peninsula. Within a decade, the masterful madrigal composer Claudio Monteverdi (bap. 1567–1643) was to make his debut in the field with two dramatic works of his own: La favola d’Orfeo (1607), the first opera to achieve a place in the modern repertory, and L’Arianna (1608), now lost except for the Lament, which was destined to become the most famous piece of music of the seventeenth century. But Monteverdi’s works owe a great deal to Peri’s score, particularly in the way they build on and amplify the rhetorical strategies of Peri’s innovative style of dramatic singing. However, in order to appreciate fully Peri’s accomplishment in inventing recitative, we first need to explore Neoplatonic notions in Renaissance Florence about Orphic singing and its effects.

Musical Magic

More than a century before the first experiments in opera, Angelo Poliziano had dramatised the myth of Orpheus for the Florentine cultural elite. His Orfeo (1480), the earliest secular play in Italian, received numerous editions during the sixteenth century and became, in effect, a Medici literary classic, popularising through the Orpheus legend the marvels of ancient music and musicians.32 The musician par excellence of antiquity, Orpheus had been able to tame the beasts of nature and charm Hades into allowing him to lead Eurydice out of the Underworld – all by means of the power of his spellbinding incantation. Poliziano himself was a member of the Neoplatonic circle surrounding Lorenzo de’ Medici (known as the ‘Magnificent’ because of his brilliance and erudition). The main intellectual figure in his informal academy was another erudite Florentine, Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499), a humanist well versed in Platonic thought. As early as 1489, Ficino postulated a ‘music-spirit’ theory, which explained the peculiar power of music by the fact that, unlike other sensual stimuli, it is carried by air, which is also the medium of the spiritus.33 This is why Ficino and his fellow Neoplatonists counted among the most prized classical disciplines to have been revived in the Florence of their day the art of singing to the Orphic lyre.

So, in the court culture of Florence during the late fifteenth century and throughout the sixteenth, singing – and especially solo singing – took on very special significance. This derived from Ficino’s conviction that the human voice, through music, provided the link between the earthly world and the cosmos. Because Platonic thought held that the individual was connected to the entire universe through harmony, it followed that the best way to express this connection was by giving voice to song. Moreover, the artful singer had the ability to envoice psychological and moral reality and the power to make that reality present to others.34 This is what underlay the Aristotelian concept of imitation or mimesis. By employing certain patterns of correspondence between micro- and macrocosm, between the motions of the human soul and the hidden harmony of the cosmos, the singer could manipulate the listener’s responses. The composer-singer, then, in the guise of the legendary Orpheus, became the expressive agent of that artistic power. And Florentine Neoplatonism, in the artistic manifestation of Poliziano’s Orfeo – a spoken drama with interpolated song35 – helped to stimulate a century-long fascination with the expressive powers of music.

It is now possible to comprehend how Mei, Bardi, Caccini, Peri, and Rinuccini, being products of a culture steeped in Neoplatonic musical mysteries, were all heirs to these Renaissance ideas about the magical effects of song. Mei shared some of Ficino’s ‘music-spirit’ theories, particularly that which held hearing to be superior to the other senses in its ability to act on the soul’s passions.36 As we have seen above, Bardi’s program for the 1589 intermedi revolved around the power of song, while his protégé, Caccini, revitalised the Renaissance ideal of incantatory solo singing for the Camerata. In creating the first opera libretto, Rinuccini, under the weight of Florentine and Medicean tradition, looked back to Poliziano’s fable of Orfeo. Not only was Orfeo a fitting protagonist for a completely sung music drama aiming to demonstrate the power of song, but also, as Tomlinson points out, its outcome and that of the other earliest tales of opera ‘vindicated the occult harmony of the cosmos … : in the answer of Daphne’s just prayers by her magical transformation [into a laurel tree], in the alleviation of Ariadne’s woes by the miraculous descent of Bacchus, in the transformative power of song in … [the] Orpheus librettos’. Like Ovid’s tales of metamorphoses from which they were drawn, these were fabrications or fables (favole) which, by focusing on timeless myths involving love and loss, sought to dramatise, externalise, or represent human sentiment.37 And what better way was there of realising the transformative power of song and Orfeo’s incantatory magic than through musical speech? This was at the heart of the notion of the representational style (stile rappresentativo). Peri’s invention of the dramatic style of singing known as recitative, then, was rooted in the belief that musical speech was capable of transmitting an inner, emotional reality and could therefore represent human affections on stage.

Peri’s Theory of Recitative

Recitative, the most extreme form of solo song or monody, was without question opera’s most radical innovation. It was also the ultimate product of humanism because it sought not merely to place the music in the service of the words, but to eliminate completely the distinction between words and music, between speaking and singing, between art and nature. It did this by synthesising the two elements into an inseparable whole, creating a language which was sui generis – more than speech but less than song, as Peri described it: a language able to communicate simultaneously both to the mind and the body, the intellect and the emotions.

In the preface to the published score of L’Euridice, Peri recounted his search for a new kind of singing with which to render dramatic dialogue (‘the kind of imitation necessary for these poems [libretti]’).38 Significantly, he recognised this creative effort as an act of imitation – not just emulation of the ancients, which it is also, but imitation of natural speech. The resultant ‘theory’ of recitative was partly adapted from his understanding of the manner of performance of ancient Greek drama and partly based on his quite remarkable analysis of the oral inflections of modern speech, perhaps stimulated in part by Mei’s writings.39 In his preface, Peri reflected on the distinction made by the ancient Greeks between the ‘continuous’ or sliding pitches of speech and the ‘diastematic’ or intervallic motion of song in which discrete pitches are sustained. He noted that the first are usually ‘fluent’ and ‘rapid’ while the others are normally ‘slow’ and ‘sustained’ but ‘could at times be hastened and made to take an intermediate course’, or ‘could be adapted to my purpose’. He went on to explain how he deployed the bass line under the voice, which constitutes the most original aspect of his theory. This involved recognising that ‘in our speech some sounds are pronounced [or intoned with a pitch] in such a way [we would say, “stressed” by a tonic accent] that a harmony can be built upon them, and that in the course of speaking we pass through many other [syllables] that are not so intoned, until we reach another that will support a progression to a new consonance [by virtue of having an identifiable pitch]’. So he placed a consonant harmony in the bass to support the ‘intoned’ notes of the melody and held it firm, allowing the ‘continuous’, rapidly declaimed syllables to be uttered over that same harmony while passing ‘through both dissonances and consonances’ until another ‘intoned’ note in the melody ‘opened the way to a new harmony’.

But Peri also built into his method a device for ensuring that the emotional content of the text was respected and that there would be some degree of variety in the recitative’s delivery. ‘Keeping in mind those inflections and accents that serve us in our grief, in our joy, and in similar states, I made the bass move in time to these, now more, now less [frequently], according to the affections.’

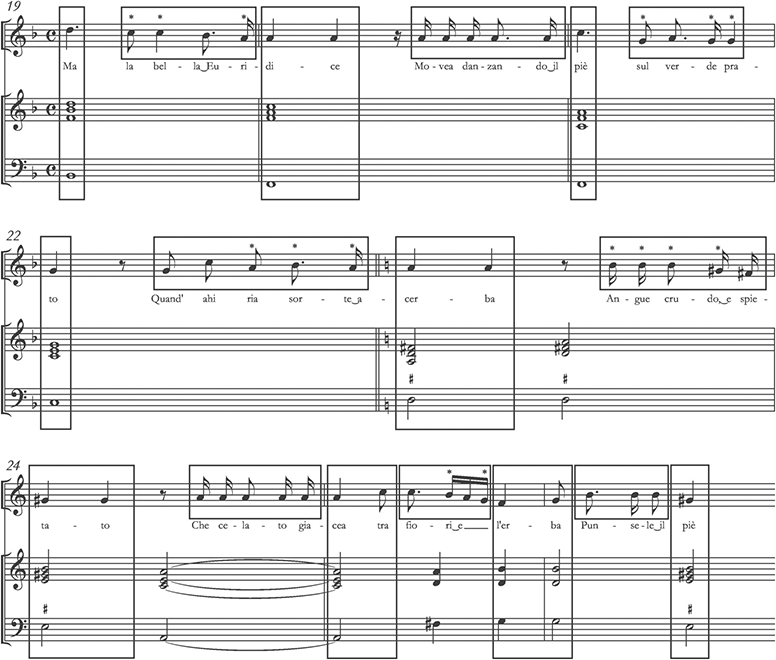

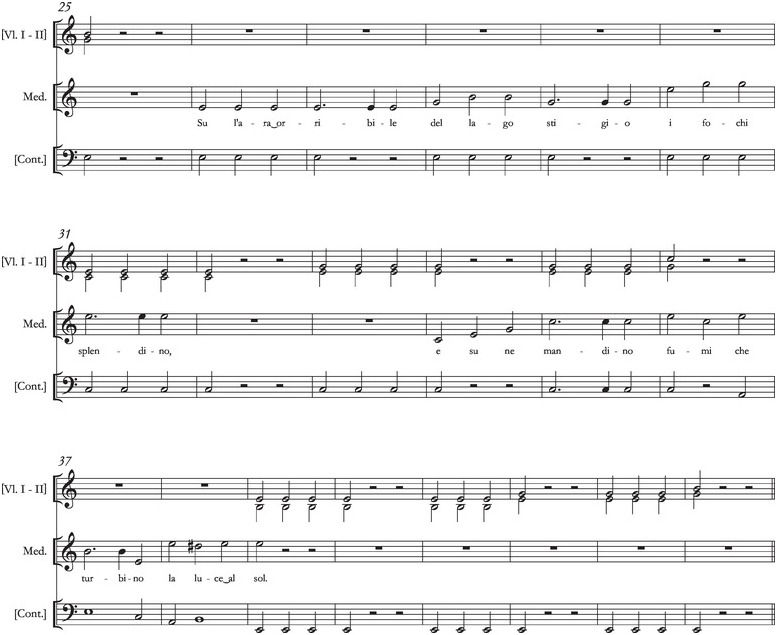

The opening of the speech from L’Euridice in which the messenger brings the news of Euridice’s death to Orfeo shows how Peri followed his own prescription for composing recitative (see Example 1.1).40 The vertical boxes identify the syllables that are sustained or accented in normal Italian pronunciation (usually the third and sixth, or sixth and tenth syllable of a line, depending on its length) and which, because they linger on a discrete pitch, are capable of suggesting a chordal harmony. Depending upon the degree of calm or excitement he wishes to generate, Peri often uses only one chord per line of text, especially for the shorter lines, and almost always places it under the penultimate syllable. The horizontal boxes contain the syllables that are quickly uttered in speech; these may form dissonances (indicated by asterisks) or consonances with the bass, depending on the affections. The way in which the dissonances are introduced and then left was not an issue for Peri because the new speechlike texture freed the voice from the constraints of counterpoint.

Example 1.1 Jacopo Peri, Le musiche di Jacopo Peri sopra L’Euridice (Florence: Giorgio Marescotti, 1600 [1601, modern style]), Dafne’s recitative, mm. 19–26

| Ma la bel-la Eu-ri-di-ce 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | But the lovely Eurydice |

| Mo-vea dan-zan-do il pie sul ver-de pra-to 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | was prancing around the green meadow |

| Quand’ahi ria sorte a-cer-ba 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | when—O bitter angry fate !— |

| An-gue cru-do, e spie-ta-to 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | a snake, cruel and merciless, |

| Che ge-la-to gia-cea tra fio-ri e l’er-ba 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | that lay motionless among flowers and grass |

| Pun-se-le il pie … 1 2 3 4 | bit her foot … |

“A PDF version of this example is available for download on Cambridge Core and via www.cambridge.org/9780521823593”

Thus, Peri conceived of recitative as a spontaneous-sounding musical language fusing speech and song that was capable of imitating, expressing, and arousing the emotions. It should be noted that neither Peri nor Caccini actually invented basso continuo texture, which had become widespread as a technique for accompanying non-polyphonic music during the last decades of the sixteenth century. However, Peri’s account of the role of the bass in his description of recitative shows that his use of the new texture as a compositional tool was completely revolutionary.41 In this manner of composing, the bass has no rhythmic profile of its own, and the harmonies adhere to no formal plan; they are there merely to support the voice, which is thus liberated from its contrapuntal framework. Another device which Peri understood to be key to the imitation of speech is the use of ametrical rhythms and phrases, carefully separated by rests and following the flow of Rinuccini’s irregularly alternating poetic lines of seven and eleven syllables. But the crucial question must be: how does Peri’s music reflect the emotional content of the words? He employs a number of devices, some of which are illustrated in Example 1.1: skilful dissonance treatment (shown by the asterisks), with greater density of dissonance signalling more painful emotions; sudden and irrational shifts of harmony, as in the motion from a G major chord to an E major one in the last measure, to intensify moments of grief; poignant and harmonically unsupported melodic intervals such as diminished fourths and fifths; and adjusting the pace of the delivery of words, with slower rhythms conveying laments and doleful sentiments. In the end, Peri knew that he had not revived Greek music; but he believed he had created a speech-song that not only resembled what had been used in ancient theatre but was also compatible with modern musical practice.

Of course, the first operas were entirely sung, but not only in recitative; more traditional styles of singing were also employed, including airs (where the action called for ‘singing’ rather than ‘speaking’) and part-songs or many-voiced madrigals for the choruses, sometimes danced, which marked the separation between scenes and delivered sententious pronouncements about the action and fate of the characters. In this respect, all of the early court operas are alike except, as noted, Cavalieri’s Rappresentatione, which, significantly, employed a libretto not by Rinuccini. But Caccini’s Euridice was also different enough from Peri’s to give the lie to Caccini’s claim of having been the first to use the new style of dramatic singing – if by that we mean real recitative and not just the affective, rhetorical kind of solo singing that was indeed his specialty.42 However, even when he was intent on emulating Peri’s recitative, Caccini’s theatrical style resembles his chamber monodies. The dialogue passages in Caccini’s Euridice are more songlike than speechlike: the bass line is more evenly paced, its function closer to that of a contrapuntal line than of a harmonic support; and the melody shows less subtlety and rhythmic variety than Peri’s and uses far less dissonance. Both composers were striving toward the ideal envisaged by Galilei in writing a kind of music that naturalistically reflected ‘how an actor delivers his lines’ so as to convey the character’s emotions. Perhaps the difference between them can be summed up by remembering that Caccini was a singer first and a composer second, whereas Peri was primarily a composer who also sang.43 Moreover, it is clear to anyone who compares the scores of Monteverdi’s Orfeo and Peri’s Euridice that, if Monteverdi can be credited with having brought opera into the future that Gagliano was predicting for it in 1608, he did so by recognising and building on Peri’s accomplishments.

Any attempt to write a history of the libretto is fraught with paradox. Almost without exception, a text is the starting point for any opera. Indeed, before Mozart, and often after, the libretto was normally complete before the composer put pen to paper, for all that it might then be revised according to the musical and other demands made upon it. As we shall see, its poetry usually had quite precise musical implications. Moreover, in early opera the poet was normally the prime mover in the operatic enterprise, not just by devising the subject and fleshing it out with appropriate words, but also given his often standard role as director of the production. The libretto was itself the public face of opera in terms of the artefacts that survive to record a given performance: libretti were usually printed for general consumption inside or outside the theatre, whereas musical scores were, on the whole, regarded as more ephemeral performance materials, to be adopted, adapted, and disposed of at will. Poets also acted as the chief ideologues of opera, promoting and defending the genre against its detractors and inserting it into broader literary and cultural debates. In a very real sense, the history of the libretto is the history of opera tout court.1

Yet as countless librettists have complained, the words rarely come high on any opera audience’s agenda. The music, singers, mise-en-scène, costumes, and choreography vie for the attention of the eye and the ear, while the text, if it is held in any regard at all, is dismissed as a trying necessity or a trifling irrelevance. The beauties of a poet’s verse are as nothing compared with the beauties of a composer’s music, and, in some minds, both pale in comparison to the beauties of a singer’s high C. In this light, the history of the libretto is just one relatively minor branch of opera studies.

The point is confirmed by a platitude: the best poetry can rarely be set to music because it is too self-sufficient, with nothing to be added. While this may or may not be true, the more damaging corollary – that any poetry for music must be second-rate – ignores the fact that libretti should be judged not by the canons of ‘great’ verse (although some are) but, rather, by fitness to purpose. Most theatre poets accepted, gladly or not, that when writing for music, compromises had to be made in terms of plot design and arrangement, and of poetic language, accent, and even vowel sounds (it is hard to sing a melisma on u). The mere fact that it always takes longer to sing something than to say it conditions the nature of poesia per musica, which, in turn, must always expect completion by something beyond itself. Nahum Tate’s verse for his dying Dido (in Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas) is scarcely great, or even good, poetry:2

| Thy hand, Belinda, darkness shades me, | |

| On thy bosom let me rest. | |

| (Cupids appear in the clouds o’er her tomb.) | |

| More I would but Death invades me. | |

| Death is now a welcome guest. | |

| When I am laid in earth, my wrongs create | |

| No trouble in thy breast; | |

| Remember me, but ah! forget my fate. |

However, it serves its purpose well. Why that should be the case is something worth exploring.

‘a Poetical Tale or Fiction’

In 1685, the English poet John Dryden published his Albion and Albanius, set to music by Luis Grabu as a full-length opera (the first in English to survive). His preface begins with the nature of operatic subject matter:

An Opera is a poetical Tale or Fiction, represented by Vocal and Instrumental Musick, adorn’d with Scenes, Machines and Dancing. The suppos’d Persons of this musical Drama, are generally supernatural, as Gods and Goddesses, and Heroes, which at least are descended from them, and are in due time, to be adopted into their Number. The Subject therefore being extended beyond the Limits of Humane Nature, admits of that sort of marvellous and surprizing conduct, which is rejected in other Plays.3

This ‘marvellous and surprizing conduct’ extends beyond the implausible plots and dei ex machina so typical of the genre. Still more ‘surprizing’ is opera’s fundamental premise, that drama can be played out in song. The consequent lack of verisimilitude might best be accepted as just a fact of operatic life, but it remained troubling in an age that still paid at least lip service to precepts drawn from Classical poetics, notably the writings of Aristotle and Horace. This explains the subject matter of the earliest operas in the north Italian courts, drawn chiefly from Graeco-Roman myth, where supernatural gods and goddesses could reasonably be expected to differentiate themselves from mere mortals by way of music. It also explains their standard setting in the pastoral utopia of Arcadia, where poetry and therefore music are natural conditions of an idealised life. For Dryden the presence of gods, goddesses, and heroes

hinders not, but that meaner Persons, may sometimes gracefully be introduc’d, especially if they have relation to those first times, which Poets call the Golden Age: wherein by reason of their Innocence, those happy Mortals, were suppos’d to have had a more familiar intercourse with Superiour Beings: and therefore Shepherds might reasonably be admitted, as of all Callings, the most innocent, the most happy, and who by reason of the spare time they had, in their almost idle Employment, had most leisure to make Verses, and to be in Love; without somewhat of which Passion, no Opera can possibly subsist.

The gradual expansion of operatic subject matter throughout the seventeenth century attenuated the pastoral argument and called for further special pleading in printed prefaces, as well as in the other standard forum for operatic apologias, the prologue. Even before opera went ‘public’ in Venice in 1637, its subjects were extending beyond the standard mythological–pastoral fare of earlier court entertainment to embrace epic (Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Virgil’s Aeneid, Lodovico Ariosto’s Orlando furioso, Torquato Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata, Giambattista Marino’s Adone), and even Greek and Roman history. Sacred operas likewise made the transition from the representation of allegorical virtues and vices (Emilio de’ Cavalieri’s Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo of 1600) to quasi-historical accounts of saints’ lives (in the operas staged in Rome under the patronage of the powerful Barberini family from the early 1630s onwards).

The appeal of epic is easily explained. Tasso’s Rinaldo and Armida first appeared in a set of intermedi by Ottavio Vernizzi (Bologna, 1623), followed by Benedetto Ferrari’s Armida (Venice, 1639), Lully’s tragédie en musique, Armide (Paris, 1686), and John Eccles’s Rinaldo and Armida (London, 1698). Characters from Ariosto’s Orlando furioso appear in Marco da Gagliano and Jacopo Peri’s Lo sposalizio di Medoro et Angelica (Florence, 1619), Francesca Caccini’s La liberazione di Ruggiero dall’isola d’Alcina (Florence, 1625), Luigi Rossi’s Il palazzo incantato (Rome, 1642), Lully’s Roland (Versailles, 1685), and Agostino Steffani’s Orlando generoso (Hanover, 1691), to name only a few. The trend increased in the eighteenth century, from Handel’s Rinaldo (1711) and Alcina (1735) through Gluck’s Armide (1777) and beyond. The line between myth and epic was thin, and both Alcina and Armida owe a clear debt to the classic femme fatale of Homer’s Odyssey and its mythological forbears Circe, save that in the later case – and no doubt to the gratification of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century censors – these pagan sorceresses could ultimately be redeemed by the love of a Christian hero. The chief difficulty in both cases, however, was how to turn epic narration into dramatic representation, which usually involved the introduction of extraneous characters (divine or mortal) to explain the plot.

Any subject drawn from history might seem to cause greater problems, although these may be more apparent than real. Here, the question of verisimilitude comes most to the fore. As the librettist Francesco Sbarra admitted in the preface to his Alessandro vincitor di se stesso (1651, set by Antonio Cesti), dealing with Alexander the Great:

I know that some people will consider the ariette sung by Alessandro and Aristotile unfit for the dignity of such great characters … nevertheless it is not only permitted but even accepted with praise … If the recitative style were not mingled with such scherzi, it would give more annoyance than pleasure. Pardon me this license, which I have taken only in order to make it less tiresome for you.4

Some ‘historical’ characters inhabit a hinterland between fact and fiction: the heroes of the Trojan Wars (Achilles, Aeneas, Ulysses) may actually have existed, but they also have strong mythical properties, and they occupy a world shaped by divine intervention. Both Ariosto and Tasso drew inspiration from history (respectively, the time of Charlemagne and the First Crusade), and yet they subjected their heroes to trials and tribulations inspired by Classical mythology and by medieval romance. The kings and queens of ancient Mesopotamia and the Middle East that also started to populate operas were probably not significant historical presences. Even Roman dictators and emperors (Julius Caesar, Claudius Nero) were not necessarily to be viewed in the same light as characters in, say, a Shakespeare ‘history play’. Indeed, in all these cases, it is often the exotic otherness of their stories that makes them appropriate for operas, which, in turn, were not to be construed, at least directly, as some kind of lesson in the facts of history, even if they raised important questions about how history might usefully be read.

Much has been made of what has often been called the ‘first’ historical opera, Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea (Venice, 1643; libretto by Giovanni Francesco Busenello), which is based on the erotic antics of Emperor Nero and his mistress, Poppaea Sabina, and the consequent downfalls of Empress Octavia (sent to exile) and the philosopher Seneca (condemned to suicide). In a preface to his own edition of the libretto, Busenello acknowledged the outline of the events treated in the opera as described by Tacitus. ‘But here’, he states, ‘we represent these actions differently.’5 Busenello further tempers any claim for historical veracity by typically relying on the intervention of the god of Love (‘without somewhat of which Passion, no Opera can possibly subsist’, says Dryden). Such treatment might or might not be a case of legitimate poetic license, but it does question the extent to which modern critics should judge this famously immoral plot on the grounds of their own historical knowledge (e.g., that both Poppaea and Nero eventually came to sticky ends).

The problem is not restricted to opera. Contemporary spoken drama runs through a similar gamut of genres, styles, and subjects, and seems equally fluid in terms of potential interpretations. So, too, do commedia dell’arte scenarios – which range far more widely than just the stereotypical characters and plots often viewed as standard in the genre – and likewise a relatively unexplored source of material for Baroque opera, contemporary novellas and related ‘popular’ literature. All these establish a number of plot-types that, in turn, prompt variations on a set of standard themes. For example, two young lovers, one or both in an unhappily arranged engagement or marriage, will staunchly resist social and other pressures applied by a pedantic tutor or a busybody nurse, surmounting all obstacles to find true happiness. The fact that this is the foundation of L’incoronazione di Poppea as much as it is of, say, Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia need not cause too much discomfort. But it suggests that originality of invention is not what matters most. In part, this is blatant commercialism: audience familiarity leads to ‘brand loyalty’ and hence increasing consumption. Furthermore, it permits efficient short-cuts in the re-telling of well-known stories. Finally, it creates a strongly intertextual world where operas are to be compared less with ‘real life’ than with other similar works.

While earlier librettists such as Ottavio Rinuccini, Busenello, and Giovanni Faustini had tended to write one-off libretti for a small circle of composers – a practice that, of course, remained in use – some later libretti seem to have become reified as ‘works’ of and for themselves that could therefore gain wider distribution. Giacinto Andrea Cicognini’s text for Orontea had settings by Francesco Lucio (Venice, 1649), Francesco Cirillo (Naples, 1654), Cesti (Innsbruck, 1656), and Filippo Vismarri (Vienna, 1660). Their complex genealogy has yet to be fully disentangled, and, in general, the mechanisms of libretto transmission have not yet been properly studied: presumably they involved complex networks of personal contacts (among impresarios, poets, composers, and singers) and also, and increasingly, of printed editions whether of single works or of collected opera omnia. One result, however, was that some literate audiences might well have started to identify particular works as belonging to their librettists independent of the different musical clothing offered by a succession of composers and singers. The same is true of, say, the libretti of Pietro Metastasio in the eighteenth century, which had a strong literary presence quite apart from their repeated operatic settings.

The latest catalogue of printed opera (etc.) libretti contains some 5,800 entries covering the years 1600–1699, and 24,000 for 1700–1799.6 It is hard nowadays to conceive the sheer scale of the operatic enterprise in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries – especially given the highly limited repertory of most modern opera houses – as the burgeoning opera ‘industry’ created complex infrastructures of supply and demand. But if the various tendencies towards standardisation identified above are certainly to be viewed in this light, they also reflect a codification of genres for further academic and related reasons. Here the need was to resist, rather than promote, certain trends that were coming to be viewed as deleterious to the notion of opera as some kind of drama; it also played into broader debates, such as the Querelle des Anciens et des Modernes that animated French (and thence European) cultural discourse from the second half of the seventeenth century into the eighteenth.

For example, the ‘Arcadian Academy’ was founded in Rome in 1690 for the reform and ‘purification’ of Italian poetry, in particular the opera libretto. It emerged like many such Roman gatherings from the circles of specific patrons, in this case Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, although its influence spread widely through Italy and abroad. Librettists associated with the Arcadians included Ottoboni himself, Apostolo Zeno, Gian Vincenzo Gravina, Silvio Stampiglia, and Metastasio. Their spokesmen, including Giovanni Maria Crescimbeni (La bellezza della volgar poesia, Rome, 1700) and Ludovico Muratori, ranged widely in their attacks on the abuses of contemporary poetry, advocating a return to Classical simplicity, in part via French models drawn from Corneille and Racine. Giacinto Andrea Cicognini’s libretto for Cavalli’s Giasone (Venice, 1649) came under particularly harsh critique by Crescimbeni:

with it he brought the end of acting, and consequently, of true and good comedy as well as tragedy. Since to stimulate to a greater degree with novelty the jaded taste of the spectators, equally nauseated by the vileness of comic things and the seriousness of tragic ones … [he] united them, mixing kings and heroes and other illustrious personages with buffoons and servants and the lowest men with unheard of monstrousness. This concoction of characters was the reason for the complete ruin of the rules of poetry, which went so far into disuse that not even locution was considered, which, forced to serve music, lost its purity, and became filled with idiocies. The careful deployment of figures that ennobles oratory was neglected, and language was restricted to terms of common speech, which is more appropriate for music; and finally the series of those short metres, commonly called ariette, which with a generous hand are sprinkled over the scenes, and the overwhelming impropriety of having characters speak in song, completely removed from the compositions the power of the affections, and the means of moving them in the listeners.7

Thus the Arcadians sought to restore order by regularising opera’s structures, themes, and affective content. But their appeal for a more ‘moral’ form of art went back to Horace’s dictum that art should not just entertain but also educate. Lip service to the ideal was conventionally paid in operatic prologues that sought to justify, or at least explain away, the action that followed. According to its prologue, L’incoronazione di Poppea is a demonstration of the power of Love over Fortune and Virtue, which, if not ‘moral’ enough in itself, might at least prompt a satirical reading of the work by negative example. Other morals were even clearer in those operas where ancient heroes exhibited the qualities of bravery, virtue, honour, wisdom, and clemency that, in turn, could stand as allegories for modern princely patrons; this provides a basis for reading most of Lully’s tragédies en musique as some form of propaganda for Louis XIV. Yet allegory is always a slippery tool. Stories from the appalling life of Nero might well serve pro-Venetian republican propaganda, so one reading of L’incoronazione di Poppea goes.8 But in Antonio Giannettini’s L’ingresso alla gioventù di Claudio Nerone (Modena, 1692; libretto by Giovanni Battista Neri), the same ‘historical’ character serves to celebrate the wedding of Francesco II d’Este, Duke of Modena. Either contemporary audiences were able to make subtle and sensitive value judgements about the subjects placed before them, or they did not care much about these subjects at all.

Of course, different members of different audiences would no doubt read different works in different ways. Indeed, such polyvalence was surely an essential condition for opera taking Europe by storm. But if one can perhaps find common ground in what opera ‘taught’ its consumers, it was probably not so much at the level of grand historical, political, or ethical sermons as it was in more immediate modes of human emotional behaviour. Those who cried or laughed at the characters and actions represented on the stage received a sentimental education in the nature of human feeling through which to construct their lives. Some might view this as social engineering; others might claim it as what is most uniquely liberating about the operatic experience.

‘softness and variety of Numbers’

Dryden also discusses the requirements of poetry for music:

If the Persons represented were to speak upon the Stage, it wou’d follow of necessity, That the Expressions should be lofty, figurative and majestical: but the nature of an Opera denies the frequent use of those poetical Ornaments: for Vocal Musick, though it often admits a loftiness of sound: yet always exacts an harmonious sweetness; or to distinguish yet more justly, The recitative part of the Opera requires a more masculine Beauty of expression and sound: the other which (for want of a proper English Word) I must call, The Songish Part, must abound in the softness and variety of Numbers: its principal Intention, being to please the Hearing, rather than to gratify the understanding.

Despite the preposterous notion ‘That Rhyme, on any consideration shou’d take place of Reason’, Dryden says, one can only follow the models established by the masters, in this case, the Italians.

Dryden’s ‘softness and variety of Numbers’ refers to the nature of Italian poetry, defined by the number of syllables in a given line and the position of the final accent.9 Poetic lines can be from three to eleven syllables in length (thus ternario, quaternario, quinario, senario, settenario, ottonario, novenario, decasillabo, and endecasillabo): the endecasillabo is the ‘classic’ norm, with its chief component, the settenario, in second place. The verso piano has the final accent on the penultimate syllable. An accent on the final syllable produces a verso tronco, and one on the antepenultimate syllable a verso sdrucciolo. Versi tronchi and sdruccioli are counted as modified versi piani: so, a settenario tronco or sdrucciolo will have, respectively, six and eight actual syllables. Syllable counts are also affected by various treatments of synaloepha and diphthongs.

The verso piano is the standard form, while versi sdruccioli and tronchi are used in special circumstances. For example, in libretti versi sdruccioli often invoke pastoral resonances (on the precedent of Jacopo Sannazaro’s Arcadia of 1504); they also have a long history of association (usually, in quinari) with infernal, demonic, or magic scenes, as in the response of the woodland gods to the summons of the wicked witch Artusia in Benedetto Ferrari and Francesco Manelli’s second Venetian opera, La maga fulminata of 1638 (Act III scene 3: ‘Insana femina’) or Medea’s ‘L’armi apprestatemi’ in Cavalli’s Giasone (Act III scene 9; 1649). The verso tronco can be comic – and it is sometimes associated with nonsense syllables – but, on a structural level, it becomes most significant to articulate closure: the result has strong musical implications, given the greater suitability for musically perfect cadences of versi tronchi (with a masculine ending, weak–strong) over versi piani (with a feminine ending, strong–weak).

Italian opera libretti draw only rarely upon the standard poetic forms of Renaissance Italian (Tuscan) hendecasyllabic verse: for example, Dante’s terza rima (rhyming aba bcb cdc…), Petrarch’s fourteen-line sonnet (with two quatrains – abab abab – and two tercets, e.g., cdc dcd) and the ottava rima stanzas of Ariosto and Tasso (abababcc). When they do, it is often for special (archaic, moralising, etc.) effect, as with Orpheus’s ‘Possente spirto, e formidabil nume’ in terza rima in Act III of Monteverdi’s Orfeo. Instead, the basis of early libretti – as of the late Renaissance pastoral plays that provided their most immediate precedent – was a mixture of free-rhyming endecasillabi and settenari, producing versi sciolti (‘loose’ or ‘free’ verse): more regular rhymes and/or metrical consistency could define structural units within this flow, and lines could be divided between characters to enhance the effect of dialogue. However, one major, and crucial, exception is the strophic canzone/canzonetta, generally in other than seven‑ or eleven-syllable lines, that appears even in the first operas. Rinuccini, for example, introduced strophic groupings mixing ottonari and quaternari in Dafne (1598) and Euridice (1600) specifically for the end-of-‘scene’ choruses. His model was the anacreontic verse introduced (in part, on French precedent) by the poet Gabriello Chiabrera (1552–1638), who said that he was catering specifically for composers of the ‘new music’ and their ‘arias’. In Orfeo, the librettist Alessandro Striggio brought such structures into the acts themselves to produce formal songs – often distinguished as such, whether dramatically (e.g., diegetically) or structurally – that stand apart from the prevailing versi sciolti for the recitative. The opening of Act II, for example, has a series of four-line stanzas for Orfeo and his companions (one in ottonari, six in settenari) separated by instrumental ritornelli, culminating in four quatrains in ottonari for Orfeo, producing an aria both in the technical sense (a strophic setting of strophic verse) and in the musical one:

| Vi ricorda, o boschi ombrosi, | 8 | Do you remember, o shady woods, | |

| de’ miei lunghi aspri tormenti, | 8 | my long, harsh torments, | |

| quando i sassi ai miei lamenti | 8 | when the rocks to my laments | |

| rispondean fatti pietosi? | 8 | responded having been made pitying? | |

| Dite, all’hor non vi sembrai | 8 | Tell me, did I not then seem to you | |

| più d’ogn’altro sconsolato? | 8 | more inconsolable than any other? | |

| Hor fortuna hà stil cangiato, | 8 | Now Fortune has changed her style, | |

| et hà volto in festa i guai. | 8 | and has turned troubles into celebration. | |

| etc. |

Eleven- and seven-syllable versi sciolti remained standard for recitative (and variants thereof) through the nineteenth century and beyond: their fluidity and flexibility were well suited to its dramatic function and musical style. However, the style of arias (choruses, ensembles, etc.) favoured shorter lines in clear-cut patterns with regular metre and rhyme. From early opera onwards, such dramatic and structural shifts were essentially cued by the librettist, whom the composer could ignore only with potential prejudice to the musical outcome. Thus reading a libretto allows one to predict with a fair degree of certainty what the music is meant to do with it, and therefore also encourages us to be surprised when something different occurs.

Such matters remained fluid throughout most of the seventeenth century as the canons of opera were forged by developing social, political, and even literary contexts. Lodovico Zuccolo (Discorso delle ragioni del numero del verso italiano, Venice, 1623) showed clear contempt for the new canzonetta, claiming it to be a mere sop to musicians. More sympathetic theorists of the second quarter of the century, such as the anonymous author of Il corago (c. 1630), still felt ambivalent about shifts away from versi sciolti: they approved the variety thereby achieved but warned against anti‑Classical improprieties. But as opera entered the public domain, the rising fortunes of the aria could scarce be resisted. Thus at the beginning of Act I scene 2 of Cavalli’s Giasone (1649), Cicognini gives the lovesick hero two stanzas of senari (with a refrain and cadential versi tronchi) before Ercole interrupts his amorous babble. The strong amphibrachs (weak–strong–weak, two per line) almost force a setting in triple time.

| Giasone: | |||

| Delizie, contenti, | 6 | Delights, raptures | |

| che l’alma beate, | 6 | that ravish the soul, | |

| fermate, fermate: | 6 | stay, stay: | |

| su questo mio core, | 6 | on this my heart | |

| deh più non stillate | 6 | pour no more | |

| le gioie d’amore. | 6 | the joys of love. | |

| Delizie mie care, | 6 | My dear delights, | |

| fermatevi qui! | 6t | stop now! | |

| Non so più bramare, | 6 | I can desire no more, | |

| mi basta così. | 6t | this is enough for me. | |

| In grembo agl’amori | 6 | In the lap of Cupids | |

| fra dolci catene | 6 | among sweet chains | |

| morir mi conviene. | 6 | am I fit to die. | |

| Dolcezza omicida | 6 | Murdering sweetness | |

| a morte mi guida | 6 | leads me to death | |

| in braccio al mio bene. | 6 | in the arms of my beloved. | |

| Dolcezze mie care, | 6 | My dear sweetnesses, | |

| fermatevi qui! | 6t | stop now! | |

| Non so più bramare, | 6 | I can desire no more, | |

| mi basta così. | 6t | this is enough for me. | |

| Ercole: | |||

| E così ti prepari | 7 | And is this how you prepare | |

| alla pugna, Giasone? | 7 | for battle, Jason? | |

| Né temi a far passaggio | 7 | Do you not fear to pass | |

| dall’amoroso al marziale agone. | 11 | from amorous to martial struggle? |

The structures adopted for ‘aria’ poetry through the seventeenth century are strikingly varied, at least until the rationalisations prompted by the Arcadians and followed by Metastasio. Here the pattern becomes relatively standard: two isometric stanzas, usually of four or three lines each (settenari – sometimes with concluding quinari – or ottonari tend to be preferred), with regular (and generally parallel) rhyme-schemes, and each often ending with a verso tronco rhyming with its counterpart. This then meshed with the musical structure that was emerging to dominate opera in the early eighteenth century, the da capo aria, with one stanza each for the A and B sections and a subsequent return to A, therefore ending with the first part of the text.

A representative example of what one might call an intermediate stage in this long process of development is provided by a scene from Antonio Sartorio’s Giulio Cesare in Egitto, to a libretto by Francesco Bussani, first performed in Venice in the 1676–1677 season (although the main score that survives comes from a performance in Naples in 1680).10 Cesare (Julius Caesar) has arrived triumphant in Egypt and is pursued by Cleopatra, who has disguised herself as the maid, Lidia; her servant, Nireno, is also in on the game. In Act I scene 4, Cesare is alone on stage musing on his amorous state – observed by Nireno in hiding – but then is suddenly surprised to hear a voice singing in the distance:

| Cesare: | ||

| Son prigioniero | 5 | I am a prisoner |

| del nudo arciero | 5 | of the blind archer |

| in laccio d’or. | 5t | in a golden trap. |

| Ma non so come | 5 | But I do not know how |

| m’hanno due chiome | 5 | two locks of hairs |

| legato il cor. | 5t | have bound my heart. |

| Vaga Lidia, ove sei? Se un sol tuo sguardo | 11 | Beautiful Lidia, where are you? If just a single glance |

| trasse quest’alma ad abitarti in fronte, | 11 | led this soul to fix upon your brow, |

| fu in sì bel ciel d’amore aquila un occhio, | 11 | then under such a beautiful sky of love, an eagle’s was the eye, |

| e Ganimede un core… | 7 | and Ganymede’s the heart… |

| Nireno (hidden): | ||

| (Ora è il tempo opportuno.) | 7 | (Now the time is right.) |

| Cleopatra (offstage, singing): | ||

| V’adoro, pupille, | 6 | I adore you, o eyes, |

| saette d’amore… | 6 | arrows of love… |

| Cesare: | ||

| Qual voce ascolto mai? | → | What voice do I hear? |

| Nireno (to himself): | ||

| Questa è Cleopatra. | 11 | This is Cleopatra. |

| Intendo, del suo amor son arti e frodi. | 11 | I understand: these are the arts and deceits of her love. |

| Femina inamorata | 7 | A woman enamoured |

| per discoprirsi amante ha mille modi. | 11 | has a thousand ways of revealing herself as a lover. |

| Cleopatra: | ||

| … le vostre faville | 6 | … your sparks |

| son faci del core. | 6 | are torches of the heart. |

| Nireno: | ||

| Signor… | → | My lord. |

| Cesare: | ||

| Nireno, udisti | 7 | Nireno, did you hear |

| questa angelica voce? | 7 | this angelic voice? |

Cesare begins with two stanzas in quinari – which Sartorio sets in ABA′ form, repeating the first stanza after the second – and then moves into versi sciolti (recitative). Cleopatra’s offstage song (‘V’adoro pupille’) is a single four-line stanza (senari) that is interrupted (after line 2) by a brief question in recitative from Cesare (‘What voice do I hear?’); Nireno then takes over this poetic line (indicated by the arrow), identifying the owner of the voice for the benefit of the audience (‘This is Cleopatra’) and then commenting on feminine wiles. The song resumes, and, at its end, Nireno reveals himself (recitative), allowing Cesare to wax rhapsodical over the ‘angelic voice’ he has just heard.

There are several typical games in play here. Cleopatra’s aria is diegetic (performed as a ‘real’ song meant to be heard as such by the other characters onstage), whereas Cesare’s is not (he is just in love); we also have the typically meta-operatic strategy of commenting on the act of singing and on the ‘angelic’ qualities of the singer. It is a scene that invites a mixture of arousal and wry humour; it also merits comparison with Handel’s handling of this same moment in his own Giulio Cesare in Egitto (London, 1724).11

‘they labour at Impossibilities’

Dryden greatly admired the Italian language, ‘the softest, the sweetest, the most harmonious, not only of any modern Tongue, but even beyond any of the Learned’, one that ‘seems indeed to have been invented for the sake of Poetry and Musick’, rich in vowels and with a pronunciation that is ‘manly’ and ‘sonorous’. Other nations, however, can only envy the Italians:

the French, who now cast a longing Eye to their Country, are not less ambitious to possess their Elegance in Poetry and Musick: in both which they labour at Impossibilities. ’Tis true indeed, they have reform’d their Tongue, and brought both their Prose and Poetry to a Standard: the Sweetness as well as the Purity is much improv’d, by throwing off the unnecessary Consonants, which made their Spelling tedious, and their pronunciation harsh: But after all, as nothing can be improv’d beyond its own Species, or farther than its original Nature will allow: as an ill Voice, though never so thoroughly instructed in the Rules of Musick, can never be brought to sing harmoniously, nor many an honest Critick, ever arrive to be a good Poet, so neither can the natural harshness of the French, or their perpetual ill Accent, be ever refin’d into perfect Harmony like the Italian.

Dryden’s reference to French’s ‘natural harshness’ presumably refers to its consonants, and the ‘perpetual ill Accent’ to the final es left mute in speech but articulated in song. Of course, a seventeenth-century French académicien would not have agreed.

The French equivalent of the Italian endecasillabo is the alexandrine, with twelve or thirteen syllables, depending on whether the rhyme is masculine (accent on the final syllable) or feminine (accent on the penultimate syllable, followed by a mute e). Alexandrines may be subdivided into six-syllable hemistichs by medial caesuras (thus offering the possibility of two parallel musical phrases for a single line of verse). Line-endings tend to alternate between masculine and feminine, often in rimes croisées (abab), although one can also find rimes plates (aabb) and rimes embrassées (abba). But the alexandrine is not always amenable to fluid musical setting given the internal caesura and the strong end-accents; it also seems too long, save where sententiousness or grandeur is required. Accordingly, the French librettist Philippe Quinault tended to opt for freer vers libre, mixing lines of different length. The argument between the flirtatious Céphise and her suitor Straton in Act I scene 4 of Lully’s Alceste (1674) is typical enough (syllable counts ignore feminine endings):12

| Céphise: | |||

| Dans ce beau jour, quelle humeur sombre | 8 | On this fine day, why so dark a humour | |

| Fais-tu voir à contre-temps? | 7 | do you display so contrarily? | |

| Straton: | |||

| C’est que je ne suis pas du nombre | 8 | It is because I am not among the number | |

| Des amants qui sont contents. | 7 | of lovers who are happy. | |

| Céphise: | |||

| Un ton grondeur et sévère | 7 | A grumbling and severe tone | |

| N’est pas un grand agrément; | 7 | is no great ornament; | |

| Le chagrin n’avance guère | 7 | anger scarcely advances | |

| Les affaires d’un amant. | 7 | the cause of a lover. | |

| Straton: | |||

| Lychas vient de me faire entendre | 8 | Lychas has just told me | |

| Que je n’ai plus ton cœur, qu’il doit seul y prétendre, | 12 | that I no longer have your heart, that he alone can claim it, | |

| Et que tu ne vois plus mon amour qu’à regret. | 12 | and that now you look upon my love only with regret. | |

| Céphise: | |||

| Lychas est peu discret… | 6 | Lychas is indiscreet… | |

| Straton: | |||

| Ah, je m’en doutais bien qu’il voulait me surprendre. | 12 | Ah, I did not doubt that he wanted to deceive me. | |

| Céphise: | |||

| Lychas est peu discret | 6 | Lychas is indiscreet | |

| D’avoir dit mon secret. | 6 | to have told my secret. |

Straton is given alexandrines when it comes to voicing his complaint and when he jumps to the (wrong) conclusion that Lychas has lied to him. The opening couplets are nicely balanced, and Céphise’s final comment wittily plays off two hemistichs to deflate her importunate lover. Her four seven-syllable lines (‘Un ton grondeur et sévère … d’un amant’) also mark a generalised moral that Lully sets apart from the prevailing recitative in the manner of a duple-time aria. However, and in general, French verse has fewer clear structural implications for music than Italian, often making it harder to predict from the text what the composer would do with it. This might have been seen as an advantage, given the French preference for more ‘natural’ and fluid forms of declamation drawing upon (as Lully himself is reported to have done) the rhetorical strategies of spoken drama.

Dryden was equally doubtful about his native tongue:

The English has yet more natural disadvantage than the French; our original Teutonique consisting most in Monosyllables, and those incumber’d with Consonants, cannot possibly be freed from those Inconveniences. The rest of our Words, which are deriv’d from the Latin chiefly, and the French, with some small sprinklings of Greek, Italian and Spanish, are some relief in Poetry; and help us to soften our uncouth Numbers, which together with our English Genius, incomparably beyond the triffling of the French, in all the nobler Parts of Verse, will justly give us the Preheminence. But, on the other hand, the Effeminacy of our pronunciation, (a defect common to us, and to the Danes) and our scarcity of female Rhymes, have left the advantage of musical composition for Songs, though not for recitative, to our neighbors.

The suggestion that ‘female Rhymes’ (i.e., based on words with strong–weak endings) are important for song is interesting, while Dryden’s sense of the ‘Effeminacy of our pronunciation’ perhaps relates to the lack in English of strong stresses, equally necessary for good melodic writing.

The standard form of ‘noble’ English verse, the (usually iambic) pentameter, had similar problems to the alexandrine in terms of its length and its tendency to fall into repetitive patterns.13 As a result, English librettists of the mid-seventeenth century such as Richard Fleckno (Ariadne Deserted by Theseus and Found and Courted by Bacchus, 1654) and William Davenant (The Siege of Rhodes, 1656) tended to adopt an equivalent of vers libre with two-, three-, four- or five-foot lines: Davenant claimed that such variety was ‘necessary to recitative music’, although the tendency towards rhyming couplets produces a certain sameness. The techniques remained similar in later works. Thus Tate’s libretto for Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas is predominantly in rhyming iambic (weak–strong) and trochaic (strong–weak) tetrameters that become rather plodding (this is typical of German verse, too). Take, for example, Dido’s first speech in Act I as presented in Purcell’s score (the 1689 libretto has some differences):

Purcell’s best option is often to treat this almost as prose, with word repetitions and also a tendency to favour enjambments (thus weakening the rhyme) even at the expense of sense: ‘Ah, ah, ah, Belinda, I am prest with torment, / Ah, ah, ah, Belinda, I am prest with torment not to be confest.’ In more dance-like sections, however, Purcell seems to enjoy piquant mismatches between textual and musical metre and stress (as in the duet ‘Fear no danger to ensue / The hero loves as well as you.’)

Given the regularity of much of Tate’s libretto, his ending (given towards the beginning of this chapter) is rather strange. Like any good librettist, he provides an appropriate number of key words to prompt the composer (‘darkness’, ‘Death’, ‘remember me’, ‘ah!’). But the metre is odd. ‘Thy hand, Belinda’ is in tetrameters, although the feminine line-endings (‘… shades me’, ‘… invades me’) maintain a flow. However, after a reasonably regular quatrain, the metre shifts to a pentameter (‘When I am laid in earth, my wrongs create’), a trimeter, and a final pentameter. Tate seems to want to set apart this portion of Dido’s final speech, as indeed does Purcell: ‘When I am laid in earth’ is, of course, Dido’s lament, over a ground bass typically based on a descending chromatic tetrachord. However, Purcell does also offer one further intervention that must be his. Tate’s syntax is somewhat elliptical, and Purcell seems (consciously or not) to have wanted to clarify the subjunctive, leading to the a-metrical ‘When I am laid in earth, may my wrongs create’.

* * *

‘Prima la musica, e poi le parole’ (‘First the music, and then the words’) was a catchphrase enshrined in the title of a satirical divertimento teatrale by Antonio Salieri (1786; libretto by Giambattista Casti). For all that it is a procedural illogicality, it reflects a common aesthetic presumption about the nature of opera. My aim here, however, has been to demonstrate the benefits of taking libretti seriously in terms of their poetic structures, and also, one might add (though I have not covered it here), for what they tell us about staging. Nor are these benefits limited just to early opera. Poetry was the standard format of opera libretti at least until the late nineteenth century and the rise both of Literaturoper and of a preference for more ‘naturalistic’ dramatic and musical prose. Thus the principles established here operated through the Classical and Romantic periods and had no less impact on, say, a Mozart or a Verdi. Ottavio Rinuccini’s legacy was powerful indeed.

Toward a ‘nuova maniera di canto’: A New Way of Singing

By the end of the sixteenth century, attempts to recover Greek tragedy led to the new genre of the dramma per musica. For the Florentine Camerata de Bardi, it meant the reinstatement of the antique melopoeia of the Greeks, that is, declamation emphasizing the word and its correct prosody. The Camerata promoted the excellence of monody, echoing the antique doctrine of the ethos proposed by the Pythagoricians, according to which modes could elicit different emotional responses in the listener: viewed as natural to man, monody was thus appropriate for the expression of affect. Later, also, Claudio Monteverdi would emphasise monody alongside polyphony, as he would argue in the preface to the Scherzi musicali of 1607. There, Monteverdi would define ‘Seconda prattica’ as a style that asked the music to amplify the affections already expressed by the poem and, in practice, to serve this latter.

Within the Camerata, Jacopo Peri and Giulio Caccini experimented with the new monody, setting to music some of Ottavio Rinuccini’s dramas: Dafne in 1595 (Peri, Florence; it was set to music in 1608 by Marco da Gagliano as La Dafne in Mantua) and, in 1600, L’Euridice by Peri and Caccini (Florence). It was no mere coincidence that the beginnings of opera privileged the myth of Orpheus, which is at the core of L’Euridice and Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (Alessandro Striggio, Mantua, 1607). Other mythological themes not only confirmed the antique literary heritage that was enjoyed by aristocratic elites but also permitted performances to dodge one of opera’s thornier issues: theatrical verisimilitude. Constantly sung throughout, opera obviously lacks verisimilitude. Thus, exceptions could be made for mythical or superhuman figures who could assume another mode of expression – supposing that these mythological characters could express themselves through song – and for roles viewed as non-normative in relation to the aristocratic milieu: servants and nurses, and other characters of low social origins who provided comic relief to the main plot.

Peri and Caccini knew that the use of monody required aesthetic justifications. In his preface to L’Euridice, Peri explained the use of monody as this ‘new way of singing’ reflecting the Antique manner, to ‘imitate one who speaks through song’ (imitar col canto chi parla).1 Monody reaches for a compromise between true singing and oratorical declamation: hence the expression often used to characterise this style – recitar cantando, which could be translated as ‘recitation in song’, or ‘to recite while singing’, according to Nino Pirrotta.2 The expression recitar cantando appeared for the very first time in the title page of Emilio de’ Cavalieri’s Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo nuovamente posta in musica dal Sig. Emilio del Cavalliere per recitar cantando (Rome, 1600) and in the instructions ‘To Readers’ of the same.3 However, for Cavalieri, its meaning was ‘to stage through song’ (mettere in scena col canto): recitar cantando identified a kind of spectacle instead of a style or a technique.