I think it would not be useless … to recall to mind how and when such spectacles had their origin, which without any doubt, since they were received with much applause … , will at some time or other reach much greater perfection … all the more if the great masters of poetry and music set their hands to it.1

Acknowledging the experimental beginnings of opera and expressing high hopes for its future, Marco da Gagliano (1582–1643) thus reviews the origins of ‘such spectacles’ in the 1608 preface of his own first effort in the new genre, La Dafne, itself a reworking and expansion of the earliest completely sung music drama a decade earlier. He goes on to explain how, after a great deal of discussion concerning the way the ancients had represented their tragedies and about what role music had played in them, the court poet Ottavio Rinuccini (1562–1621) began to write the story (favola) of Dafne, and the learned amateur Jacopo Corsi (1561–1602) composed some airs on part of it. Determined to see what effect a (completely sung) work would have on the stage, they approached the skilled composer and singer Jacopo Peri, who finished the work and probably premièred the role of Apollo ‘on the occasion of an evening entertainment’ during the carnival of 1597/8 and on subsequent occasions. In the invited audience at the first performance were Don Giovanni de’ Medici and ‘some of the principal gentlemen’ of Florence.2

Gagliano, Florentine composer and maestro di cappella to the Medici court from 1609 until his death in 1643, provides a useful and accurate outline – despite the rivalries and counterclaims surrounding the events (about which more will be said) – of the immediate circumstances of opera’s modest beginnings, one that will serve well enough to organise our discussion.

Florentine Origins

His narration infers, first of all, that it was a completely Florentine affair. This is not surprising since Florence had a long tradition of musical theatre in the sixteenth century, manifested principally in the productions known as intermedi that were staged between the acts of spoken plays. These were but one of many different types of festivities mounted by courts all over Europe. But unlike other centres, Medicean Florence also had a particularly rich history of ‘civic humanism’3 – that is, of involvement by its more educated citizens in the rediscovery of and allegiance to Classical culture via a network of formal and informal academies that were engaged in critical inquiry and philological pursuits, which involved studying the Greek and Latin texts of the ancients. Moreover, as Gary Tomlinson and others have suggested, Florence was the centre of a particular Renaissance worldview that accorded music a ‘magical’ role in the cosmos and in man’s interaction with it.4 Before filling in some of the details of Gagliano’s outline, we shall examine each of these three elements – intermedi, humanism, and musical magic – in order to understand how their confluence at the end of the sixteenth century resulted in Florence becoming the birthplace of opera.

Intermedi

Extravagantly staged pageantry involving sumptuous costumes, special effects, music, dance, and song characterised the sixteenth-century Florentine intermedi, which were produced as entr’actes to a theatrical entertainment such as a comedy or pastoral play at court. Sets of intermedi were originally a modest and functional feature of North Italian court entertainments: they served to signal the divisions of the spoken drama, since there was no curtain to be dropped; and they suggested the passage of time by employing allegorical characters and themes unrelated to the main plot. At the court of the Medici rulers, however, intermedi evolved into an elaborately lavish type of spectacle, planned and rehearsed months in advance, whose cost and impact dwarfed that of the main drama and whose raison d’être was to leave no doubt in the minds of the audience – comprised entirely of invited guests gathered to help celebrate a special family event – about their host’s wealth and generosity.

Such an occasion was the marriage in 1589 of Grand Duke Ferdinando de’ Medici of Tuscany to the French Princess Christine of Lorraine, a union that had been in negotiation for nearly a year. The intermedi devised for this event climaxed a month-long sequence of public and courtly pageantry that mobilised the combined intellectual, artistic, and administrative forces of Tuscany at the height of its wealth, power, and cultural prestige. ‘Their splendor cannot be described’, wrote one court chronicler, ‘and anyone who did not see it could not believe it.’5 A huge team of artists, artisans, poets, musicians, architects, and technicians was assembled under the intellectual guidance of the prominent Florentine aristocrat and military leader Giovanni de’ Bardi (1534–1612), who formulated the underlying conception of the intermedi, served as stage director, and coordinated all the thematic and antiquarian aspects of the project.6 As the moving spirit behind the program, Bardi worked closely with the court poets, principally Rinuccini, who wrote most of the text.7 Emilio de’ Cavalieri (c. 1550–1602), the recently appointed superintendent of music at the ducal court who had been in Ferdinando’s retinue while he was still a cardinal resident in Rome, became the show’s musical director. The court architect-engineer Bernardo Buontalenti (c. 1531–1608), who only a few years earlier had constructed for the Medici the first permanent indoor theatre with a modern proscenium arch, remodelled it for the occasion, and designed the sets and costumes.8 The music was largely composed by court organist Cristofano Malvezzi and madrigalist Luca Marenzio, with individual contributions by the young composer-singer Jacopo Peri (1561–1633), by Bardi’s protégé Giulio Caccini (1551–1618), and by Bardi himself, among others. Note that both Rinuccini and Peri also figure in Gagliano’s narration of opera’s origins a decade later.

Bardi conceived the set of six intermedi as ‘a sort of mythological history of music’,9 fitting for a wedding celebration in that it depicts the descent of Harmony as a gift from the gods and predicts a new Golden Age initiated by the royal couple. Moreover, the individual tableaux are loosely unified by the literary theme of the power of music, a topic of longstanding interest to the Florentines (see ‘Musical Magic’). The opening intermedio contemplates the harmony of the spheres. The next, which represents the ancient rivalry between the Muses and the Pierides (nine daughters of King Pierus who challenged the Muses to a song contest), dwells on the virtues and virtuosity of song. The third, by enacting the combat between Apollo and the Pythic serpent, prefigures the opening scene from the Rinuccini-Peri Dafne about which Gagliano wrote. It thus introduces the first operatic hero, Apollo – god of music and of the sun, and some said father of the legendary musician Orpheus, who became in turn the protagonist of several early opera libretti. The fifth intermedio gave a prominent role to Peri, who composed and performed his first piece for solo voice to portray another musician-poet par excellence, Arion; according to myth, Arion was saved from drowning by a dolphin attracted by the dazzling power of his song. In the concluding allegory, harmony and rhythm are bestowed on mortals who, represented by the nymphs and shepherds of Arcadia, are instructed by the gods in the art of dancing during an elaborately choreographed ballo.

The 1589 intermedi had many of the same players and almost all the ingredients of opera – costumes, scenery, stage effects (for example, the life-size fire-spitting dragon slain by Apollo10), enthralling solo singing, colourful instrumental music, large concerted numbers, dance – everything except unified action and the innovative style of dramatic singing yet to be created. It remained for a few pioneering individuals to shape these elements into a new and quite ‘noble style of performance’11 that would, by emulating ancient theatre, revive the power of modern music to move the emotions.

Humanism

The catalyst for their experiments, as Rinuccini explains in his preface to the libretto for the first opera for which the music survives in print (Peri’s Euridice, 160012), was the belief by some scholars that the ancient Greeks and Romans sang their tragedies on the stage in their entirety.13 Although Renaissance scholars disagreed among themselves about the role of music in ancient tragedy, the amount of attention focused on the practices of the ancients was typical of humanism. Rinuccini, it seems, subscribed to a kind of Greek revivalism that Tomlinson has called ‘ordinary-language humanism’ – a view that underlay ‘the whole late-Renaissance exaltation of music’s affective powers’;14 indeed, it had been manifest in one way or another across the breadth of Renaissance musical culture in the degree of importance given to expressing the meaning of the text. While philological humanism promulgated the transmission, translation, and interpretation of ancient texts, and rhetorical humanism was built on the principles of persuasive oratory, this ordinary-language humanism placed greater emphasis on the ability of language itself – the very sound and shape of the words rather than the eloquence with which they were arranged – to communicate meaning and emotion.

Where did these ideas come from? Rinuccini belonged to the Alterati Academy – its very name (Academy of the Altered Ones) acknowledged the ability of ideas to effect change in human beings – one of a network of associations of artists and thinkers that flourished in Florence during the sixteenth century. Its membership included the widely read and accomplished Count Giovanni de’ Bardi, who was a member of long standing by the time Rinuccini was initiated in 1586, three years before they collaborated on the wedding festivities discussed above. Another member was the remarkable scholar Girolamo Mei (1519–1594), who, although Florentine by birth, worked in Rome and made known his ideas about Tuscan prose and poetry along with the results of his research into Greek music through correspondence with Bardi and other academicians. An erudite philologist, Mei developed theories about language that were in fact as central to the genesis of the new dramatic style of singing as his convictions about Greek music were to the origins of opera; for not only was it Mei’s belief that poems and plays were always sung in ancient times, whether by soloists or by the chorus, but also that they were sung monophonically so that the words as sounding structures could act on the listeners’ souls. Finally, the Alterati also counted among its members another Florentine nobleman, Jacopo Corsi, the enthusiastic amateur we first encountered in Gagliano’s preface, who partially composed, on Rinuccini’s text, and fully sponsored the production of the first completely sung ‘favola tutta in musica’, La Dafne, in 1597/8. These are some of the reasons that justify Claude Palisca’s having dubbed the Alterati of Florence ‘pioneers in the theory of dramatic music’.15

Now, Count Bardi also had his own circle of friends with similar humanist and musical interests, a more informal academy which met in his palace and came to be known as the Florentine Camerata.16 As the courtier chiefly responsible for organising entertainments for the grand duke, Bardi naturally became interested in theatrical or dramatic music and eagerly cultivated his long-distance relationship with Mei.17 These two, then, were key players in both the Alterati Academy and the Camerata, and it’s easy to see that both groups shared a concern with musical humanism. Bardi’s inner circle also included the singer-lutenist-composer Caccini (whom he involved in the 1589 intermedi) as well as Vincenzo Galilei (c. 1530–1591), another talented singer-lutenist-composer in his employ. Galilei, father of the revolutionary thinker and astronomer Galileo, had studied with the most famous counterpoint teacher of the age, Gioseffo Zarlino, and had already published a text on how to arrange polyphonic music for solo voice and lute (Il Fronimo, 1568), a medium that became increasingly popular during the last quarter of the century.18 Under the influence of Bardi and Mei, Galilei wrote a treatise that became the Camerata’s revolutionary manifesto, for it articulated the principles of ordinary-language humanism in the most radical way imaginable for a sixteenth-century musician: eschew vocal counterpoint altogether and adopt a type of non-polyphonic composition combining (texted) melody and simple accompaniment (which we now call monody).

Galilei published his inflammatory tract in the conventional Renaissance form of a dialogue – a conversation between two friends (one of whom is named after Count Bardi) debating the merits of ancient and modern music (Dialogo della musica antica e della moderna, 1581).19 By ‘modern music’ he meant the ars perfecta, the system of counterpoint he and all the leading composers of his day had learned, directly or indirectly, from Zarlino, whose Istitutione harmoniche (1558) was the foremost textbook for writing both sacred and secular music. Galilei challenged the ultimate perfection of counterpoint and advocated instead restoring through a single melody line the expressive powers of which ancient music was capable, judging by the corpus of literature about the Greek modal system that had been revived by Renaissance humanists and was recently newly interpreted by Mei.20 Why monophony? Because it alone was capable of imitating nature – that is, the ‘natural language’ of speech, through which a person’s character and states of soul are reflected. Mei had contended that ancient music always presented a single affection embodied in un aria sola (a single melody). He reasoned that monophony could convey the message of the text through the natural expressiveness of the voice – via the register, rhythms, and contours of its utterance – far better than the contrived delivery of a polyphonic texture.21 Like Mei, Galilei was persuaded that counterpoint was ineffective because it presented contradictory information to the ear. When several voices simultaneously sang different melodies and words – pitting high pitches against low, slow rhythms against fast, rising intervals against descending ones – the resulting web of sounds was incapable of projecting the semantic meaning or emotional message of the text. Only by returning to an art truly founded on the imitation of human nature rather than on contrapuntal artifice would it be possible for modern composers to approach the acclaimed power of ancient music.

Plato had taught that song (melos) was comprised of words, rhythm, and pitch, in that order. From that followed the humanist ideal of music and poetry as two sides of a single language, as well as the idea that song arose from an innate harmony within the words that was muted in normal speech. For this reason, Galilei advocated the art of oratory as a model for modern musicians, urging them to imitate the manner in which successful actors delivered their lines on stage:

Kindly observe in what manner the actors speak, in what range, high or low, how loudly or softly, how rapidly or slowly they enunciate their words … how one speaks when infuriated or excited; how a married woman speaks, how a girl, how a lover … how one speaks when lamenting, when crying out, when afraid, and when exulting with joy.22

For Galilei, it is clear that ‘how one speaks’ the words reveals their underlying emotion. For the composers of monody and theatrical song, by extension, it then became a question of ‘how one sings’ the words to disclose their innate significance.23

Twenty years Galilei’s junior, Caccini built his long career as a singer, singing teacher, and composer on these precepts, claiming to have learnt more from Bardi’s Camerata than from ‘more than 30 years of counterpoint’. After composing solo madrigals and airs with figured bass accompaniment and performing them for Bardi’s circle, where they were received ‘with warm approval’ in the 1580s, Caccini issued his pathbreaking collection of madrigals and airs in 1602 with the title Le nuove musiche (The New Music – more correctly translated as ‘musical works in a new style’).24 Caccini’s was the first set of composed and published monodies, as opposed to the improvised airs that had been ‘recited’ on formulas suitable for rendering sonnets, epic stanzas, and other fixed poetic forms during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries; in effect, the new pieces were frozen improvisations. The distinction of being composed also separates them from contemporary solo songs that were actually arrangements of polyphonic compositions. In addition to their new texture, Caccini’s works embody Galilei’s precepts in two more ways: they abjure the common manner and excessive use of ornamentation, and in melodic contour and rhythmic profile they approach the nuances of speech. In the first instance, Caccini was adamant about using ornamentation only to enhance the affections inherent in the text and melody. And, to approximate the flexibility of speech, he advocated that the performer apply his concept of sprezzatura – a sort of nonchalance or casualness of delivery – a concept he adapted from Baldassare Castiglione’s Il libro del cortigiano (Book of the Courtier, 1528), a meditation on the qualities necessary for the ideal Renaissance courtier to cultivate.25 Caccini’s innovations had a far-reaching impact on composers of monody in the early seventeenth century. However, once the theatre became the proving ground of the capabilities of modern music in the late 1590s, Caccini staked his claim to primacy in that arena by composing and rushing into print his own first music drama, L’Euridice (1601), in the wake of Peri’s and Rinuccini’s success.26

After Bardi moved to Rome in 1592, having been to some extent unseated at court by Duke Ferdinando’s new favourite, Cavalieri, the field was left open for the wealthy merchant Corsi to become the principal patron of music in Florence (after the Medici) and the standard-bearer of the experimental ‘movement’ in musical theatre.27 With Rinuccini, fellow academician in the Alterati, and Peri, he produced their first offering, La Dafne, in 1597/8.28 In contrast to the 1589 intermedi, performed before several thousand international guests, Dafne was a very modest affair. It first played in Corsi’s home for a comparatively few invited guests, among whom were ‘some of the principal gentlemen’ of Florence.29 It had the distinction, however, of being the first to include the dramatic style of singing now known as recitative. It was soon followed by L’Euridice (by Rinuccini and Peri, with some music by Caccini), performed in October 1600, as a small and fairly inconsequential part of the entertainments for the wedding festivities of Maria de’ Medici and Henry IV of France.30 Because Caccini would not allow the singers under his tutelage to perform Peri’s music, he inserted his own music for some of the roles. Meanwhile, Cavalieri was claiming the distinction of having composed and produced in 1595 the first completely sung ‘pastorals’ on texts by a different poet, Laura Guidiccioni (one with whom he had collaborated in the 1589 intermedi) – a claim which Peri generously acknowledged in his preface to L’Euridice. But Cavalieri’s works are not extant, and, judging by the tuneful style of his later musical play, La Rappresentazione di Anima, et di Corpo, printed in 1600 and first performed in Rome, Cavalieri shared neither the academic perspective nor the humanistic, ordinary-language aesthetic of his Florentine peers.31 Still, such private rivalries among musicians were fuelled by the printers who promptly published their works and by the public competition among princes to garner attention with their patronage. These were some of the factors that fostered the endurance of the first completely sung musical tales and their spread to other urban centres – Mantua, Rome, Venice, and elsewhere, both inside and outside the Italian peninsula. Within a decade, the masterful madrigal composer Claudio Monteverdi (bap. 1567–1643) was to make his debut in the field with two dramatic works of his own: La favola d’Orfeo (1607), the first opera to achieve a place in the modern repertory, and L’Arianna (1608), now lost except for the Lament, which was destined to become the most famous piece of music of the seventeenth century. But Monteverdi’s works owe a great deal to Peri’s score, particularly in the way they build on and amplify the rhetorical strategies of Peri’s innovative style of dramatic singing. However, in order to appreciate fully Peri’s accomplishment in inventing recitative, we first need to explore Neoplatonic notions in Renaissance Florence about Orphic singing and its effects.

Musical Magic

More than a century before the first experiments in opera, Angelo Poliziano had dramatised the myth of Orpheus for the Florentine cultural elite. His Orfeo (1480), the earliest secular play in Italian, received numerous editions during the sixteenth century and became, in effect, a Medici literary classic, popularising through the Orpheus legend the marvels of ancient music and musicians.32 The musician par excellence of antiquity, Orpheus had been able to tame the beasts of nature and charm Hades into allowing him to lead Eurydice out of the Underworld – all by means of the power of his spellbinding incantation. Poliziano himself was a member of the Neoplatonic circle surrounding Lorenzo de’ Medici (known as the ‘Magnificent’ because of his brilliance and erudition). The main intellectual figure in his informal academy was another erudite Florentine, Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499), a humanist well versed in Platonic thought. As early as 1489, Ficino postulated a ‘music-spirit’ theory, which explained the peculiar power of music by the fact that, unlike other sensual stimuli, it is carried by air, which is also the medium of the spiritus.33 This is why Ficino and his fellow Neoplatonists counted among the most prized classical disciplines to have been revived in the Florence of their day the art of singing to the Orphic lyre.

So, in the court culture of Florence during the late fifteenth century and throughout the sixteenth, singing – and especially solo singing – took on very special significance. This derived from Ficino’s conviction that the human voice, through music, provided the link between the earthly world and the cosmos. Because Platonic thought held that the individual was connected to the entire universe through harmony, it followed that the best way to express this connection was by giving voice to song. Moreover, the artful singer had the ability to envoice psychological and moral reality and the power to make that reality present to others.34 This is what underlay the Aristotelian concept of imitation or mimesis. By employing certain patterns of correspondence between micro- and macrocosm, between the motions of the human soul and the hidden harmony of the cosmos, the singer could manipulate the listener’s responses. The composer-singer, then, in the guise of the legendary Orpheus, became the expressive agent of that artistic power. And Florentine Neoplatonism, in the artistic manifestation of Poliziano’s Orfeo – a spoken drama with interpolated song35 – helped to stimulate a century-long fascination with the expressive powers of music.

It is now possible to comprehend how Mei, Bardi, Caccini, Peri, and Rinuccini, being products of a culture steeped in Neoplatonic musical mysteries, were all heirs to these Renaissance ideas about the magical effects of song. Mei shared some of Ficino’s ‘music-spirit’ theories, particularly that which held hearing to be superior to the other senses in its ability to act on the soul’s passions.36 As we have seen above, Bardi’s program for the 1589 intermedi revolved around the power of song, while his protégé, Caccini, revitalised the Renaissance ideal of incantatory solo singing for the Camerata. In creating the first opera libretto, Rinuccini, under the weight of Florentine and Medicean tradition, looked back to Poliziano’s fable of Orfeo. Not only was Orfeo a fitting protagonist for a completely sung music drama aiming to demonstrate the power of song, but also, as Tomlinson points out, its outcome and that of the other earliest tales of opera ‘vindicated the occult harmony of the cosmos … : in the answer of Daphne’s just prayers by her magical transformation [into a laurel tree], in the alleviation of Ariadne’s woes by the miraculous descent of Bacchus, in the transformative power of song in … [the] Orpheus librettos’. Like Ovid’s tales of metamorphoses from which they were drawn, these were fabrications or fables (favole) which, by focusing on timeless myths involving love and loss, sought to dramatise, externalise, or represent human sentiment.37 And what better way was there of realising the transformative power of song and Orfeo’s incantatory magic than through musical speech? This was at the heart of the notion of the representational style (stile rappresentativo). Peri’s invention of the dramatic style of singing known as recitative, then, was rooted in the belief that musical speech was capable of transmitting an inner, emotional reality and could therefore represent human affections on stage.

Peri’s Theory of Recitative

Recitative, the most extreme form of solo song or monody, was without question opera’s most radical innovation. It was also the ultimate product of humanism because it sought not merely to place the music in the service of the words, but to eliminate completely the distinction between words and music, between speaking and singing, between art and nature. It did this by synthesising the two elements into an inseparable whole, creating a language which was sui generis – more than speech but less than song, as Peri described it: a language able to communicate simultaneously both to the mind and the body, the intellect and the emotions.

In the preface to the published score of L’Euridice, Peri recounted his search for a new kind of singing with which to render dramatic dialogue (‘the kind of imitation necessary for these poems [libretti]’).38 Significantly, he recognised this creative effort as an act of imitation – not just emulation of the ancients, which it is also, but imitation of natural speech. The resultant ‘theory’ of recitative was partly adapted from his understanding of the manner of performance of ancient Greek drama and partly based on his quite remarkable analysis of the oral inflections of modern speech, perhaps stimulated in part by Mei’s writings.39 In his preface, Peri reflected on the distinction made by the ancient Greeks between the ‘continuous’ or sliding pitches of speech and the ‘diastematic’ or intervallic motion of song in which discrete pitches are sustained. He noted that the first are usually ‘fluent’ and ‘rapid’ while the others are normally ‘slow’ and ‘sustained’ but ‘could at times be hastened and made to take an intermediate course’, or ‘could be adapted to my purpose’. He went on to explain how he deployed the bass line under the voice, which constitutes the most original aspect of his theory. This involved recognising that ‘in our speech some sounds are pronounced [or intoned with a pitch] in such a way [we would say, “stressed” by a tonic accent] that a harmony can be built upon them, and that in the course of speaking we pass through many other [syllables] that are not so intoned, until we reach another that will support a progression to a new consonance [by virtue of having an identifiable pitch]’. So he placed a consonant harmony in the bass to support the ‘intoned’ notes of the melody and held it firm, allowing the ‘continuous’, rapidly declaimed syllables to be uttered over that same harmony while passing ‘through both dissonances and consonances’ until another ‘intoned’ note in the melody ‘opened the way to a new harmony’.

But Peri also built into his method a device for ensuring that the emotional content of the text was respected and that there would be some degree of variety in the recitative’s delivery. ‘Keeping in mind those inflections and accents that serve us in our grief, in our joy, and in similar states, I made the bass move in time to these, now more, now less [frequently], according to the affections.’

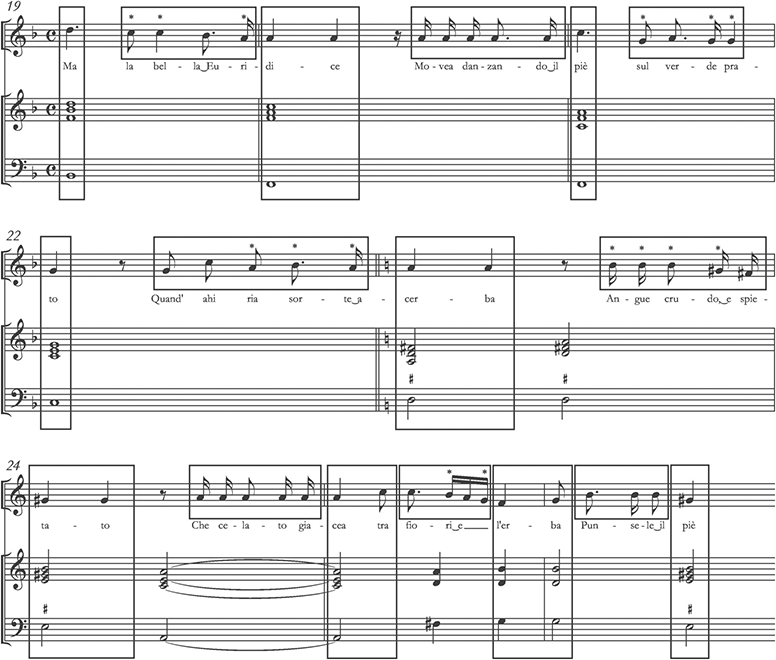

The opening of the speech from L’Euridice in which the messenger brings the news of Euridice’s death to Orfeo shows how Peri followed his own prescription for composing recitative (see Example 1.1).40 The vertical boxes identify the syllables that are sustained or accented in normal Italian pronunciation (usually the third and sixth, or sixth and tenth syllable of a line, depending on its length) and which, because they linger on a discrete pitch, are capable of suggesting a chordal harmony. Depending upon the degree of calm or excitement he wishes to generate, Peri often uses only one chord per line of text, especially for the shorter lines, and almost always places it under the penultimate syllable. The horizontal boxes contain the syllables that are quickly uttered in speech; these may form dissonances (indicated by asterisks) or consonances with the bass, depending on the affections. The way in which the dissonances are introduced and then left was not an issue for Peri because the new speechlike texture freed the voice from the constraints of counterpoint.

Example 1.1 Jacopo Peri, Le musiche di Jacopo Peri sopra L’Euridice (Florence: Giorgio Marescotti, 1600 [1601, modern style]), Dafne’s recitative, mm. 19–26

| Ma la bel-la Eu-ri-di-ce 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | But the lovely Eurydice |

| Mo-vea dan-zan-do il pie sul ver-de pra-to 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | was prancing around the green meadow |

| Quand’ahi ria sorte a-cer-ba 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | when—O bitter angry fate !— |

| An-gue cru-do, e spie-ta-to 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | a snake, cruel and merciless, |

| Che ge-la-to gia-cea tra fio-ri e l’er-ba 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | that lay motionless among flowers and grass |

| Pun-se-le il pie … 1 2 3 4 | bit her foot … |

“A PDF version of this example is available for download on Cambridge Core and via www.cambridge.org/9780521823593”

Thus, Peri conceived of recitative as a spontaneous-sounding musical language fusing speech and song that was capable of imitating, expressing, and arousing the emotions. It should be noted that neither Peri nor Caccini actually invented basso continuo texture, which had become widespread as a technique for accompanying non-polyphonic music during the last decades of the sixteenth century. However, Peri’s account of the role of the bass in his description of recitative shows that his use of the new texture as a compositional tool was completely revolutionary.41 In this manner of composing, the bass has no rhythmic profile of its own, and the harmonies adhere to no formal plan; they are there merely to support the voice, which is thus liberated from its contrapuntal framework. Another device which Peri understood to be key to the imitation of speech is the use of ametrical rhythms and phrases, carefully separated by rests and following the flow of Rinuccini’s irregularly alternating poetic lines of seven and eleven syllables. But the crucial question must be: how does Peri’s music reflect the emotional content of the words? He employs a number of devices, some of which are illustrated in Example 1.1: skilful dissonance treatment (shown by the asterisks), with greater density of dissonance signalling more painful emotions; sudden and irrational shifts of harmony, as in the motion from a G major chord to an E major one in the last measure, to intensify moments of grief; poignant and harmonically unsupported melodic intervals such as diminished fourths and fifths; and adjusting the pace of the delivery of words, with slower rhythms conveying laments and doleful sentiments. In the end, Peri knew that he had not revived Greek music; but he believed he had created a speech-song that not only resembled what had been used in ancient theatre but was also compatible with modern musical practice.

Of course, the first operas were entirely sung, but not only in recitative; more traditional styles of singing were also employed, including airs (where the action called for ‘singing’ rather than ‘speaking’) and part-songs or many-voiced madrigals for the choruses, sometimes danced, which marked the separation between scenes and delivered sententious pronouncements about the action and fate of the characters. In this respect, all of the early court operas are alike except, as noted, Cavalieri’s Rappresentatione, which, significantly, employed a libretto not by Rinuccini. But Caccini’s Euridice was also different enough from Peri’s to give the lie to Caccini’s claim of having been the first to use the new style of dramatic singing – if by that we mean real recitative and not just the affective, rhetorical kind of solo singing that was indeed his specialty.42 However, even when he was intent on emulating Peri’s recitative, Caccini’s theatrical style resembles his chamber monodies. The dialogue passages in Caccini’s Euridice are more songlike than speechlike: the bass line is more evenly paced, its function closer to that of a contrapuntal line than of a harmonic support; and the melody shows less subtlety and rhythmic variety than Peri’s and uses far less dissonance. Both composers were striving toward the ideal envisaged by Galilei in writing a kind of music that naturalistically reflected ‘how an actor delivers his lines’ so as to convey the character’s emotions. Perhaps the difference between them can be summed up by remembering that Caccini was a singer first and a composer second, whereas Peri was primarily a composer who also sang.43 Moreover, it is clear to anyone who compares the scores of Monteverdi’s Orfeo and Peri’s Euridice that, if Monteverdi can be credited with having brought opera into the future that Gagliano was predicting for it in 1608, he did so by recognising and building on Peri’s accomplishments.