Unquestionably modern musical America has been influenced by modern musical Europe.

George Gershwin, “The Composer in the Machine Age,” in Revolt in the Arts: A Survey of the Creation, Distribution and Appreciation of Art in America, ed. Oliver M. Sayler (New York: Brentano's, 1930), 264

Why does America continually look to us foreigners for enlightenment and guidance? Our history hardly points to our being fit to lead your blindness anywhere other than into the ditch.

—Maurice Brown, 19302

Maurice Brown, “Suggesting a Dramatic Declaration of Independence,” in Revolt in the Arts, ed. Oliver M. Sayler, 207. Maurice Brown was a British playwright, actor, director, and producer who founded the Chicago Little Theater, which he termed the “grandfather” of the New York Theater Guild.

George Gershwin was the first to admit that he had European models in composing Porgy and Bess. Music critic and librettist Leonard Liebling, who encountered Gershwin on vacation in Saratoga, New York, recalled this racetrack banter:

“How's the opera coming on?” I inquired.

“Too fast! I've got too many ideas and have to keep on scrapping them.”

“What style of music is it?”

“American, of course, in the modern idiom, but just the same, a cross between Meistersinger and Madame Butterfly. Are those models good enough?”3

Leonard Liebling, untitled essay for the memorial volume George Gershwin, ed. Merle Armitage (New York: Longmans, Green & Co., 1938), 125.

However “good” Gershwin's models were, their influence was at least strong enough to be detected by some of the first listeners. As Gershwin's opera premiered in Boston and New York, music critics immediately cited both of these precedents along with numerous others, especially Bizet's Carmen, Gustave Charpentier's Louise, and various other works of Wagner. The cries of the Strawberry Woman and Crab Man in Porgy and Bess reminded several writers of the analogous moment in Louise. A critic in Boston heard “very definite indications that the composer recognized a potent quality in the works of his predecessors. Who could listen to the cries of the vendors in Act 2, for instance, without being reminded of Louise?” Confirming that she thought the resemblance was purposeful, she added, “Mr. Gershwin has evidently profited by study.”4

Grace May Stutsman, “Gershwin's Porgy and Bess Produced,” Musical America, 10 October 1935. This review and others are quoted in John A. Johnson, “Gershwin's ‘American Folk Opera’: The Genesis, Style, and Reputation of ‘Porgy and Bess’ (1935),” Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1996, vol. 1, 144.

This notation is discussed in Johnson, “Gershwin's ‘American Folk Opera’,” I, 126–27. In chap. 2, “Precursors of Porgy and Bess I: European Antecedents,” Johnson gives a comprehensive survey of which European works were cited by critics (102–57). The sketch page is in the Gershwin Collection, Library of Congress, Music Division, Sketch BB.

In arguing that Gershwin's Porgy and Bess is heavily indebted to Berg's Wozzeck, I will primarily explore structural processes, understanding structure not as form—in the sense of ordered tonal centers and thematic repetition in a rondo or sonata-allegro movement—but rather as patterns or a succession of discrete events that are shared by the two operas. Motives and chords play a relatively small role in the discussion, taking their place alongside musical events that range from the large—a fugue or a lullaby—to the small—a pedal, an ostinato, or some detail of counterpoint. For a resemblance to be significant enough to suggest that Gershwin emulated Berg, it needs to occur either in a succession of similar musical events, or in conjunction with a related narrative moment, or preferably both. But unlike the influences quickly heard by critics and other listeners, the structural similarities that I propose are for the most part inaudible, because of the obvious stylistic differences between the two operas. The affinities exist primarily in the background, but are no less meaningful for that. Their frequency is also important, for while isolated resemblances ought to be considered coincidental, I maintain that in Porgy and Bess the number is sufficiently great for coincidence to be implausible.

Gershwin's admiration for Wozzeck and the Lyric Suite has been noted by many. From the time of his 1928 visit to Berg in Vienna, Gershwin clearly held Berg in high esteem. He possessed an autograph excerpt of the Lyric Suite, along with scores of that work and Wozzeck, the latter reputed to be one of his prize possessions.6

According to Oscar Levant, A Smattering of Ignorance (New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1940),“Gershwin treasured the piano score of Wozzeck and was deeply impressed by the opera when he journeyed to Philadelphia for the performance under Stokowski in 1931” (155).

Joan Peyser, The Memory of All That: The Life of George Gershwin (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993), 230. Steven Gilbert does not specify Wozzeck, but he considers Berg's influence strong: “There is another affinity, on the surface less likely but potentially more profound, with a composer [Berg] whose very soul was opera.” This is from the conclusion of his chapter on Porgy and Bess in The Music of Gershwin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 206.

Allen Forte, “Reflections Upon the Gershwin-Berg Connection,” The Musical Quarterly 83 (1999): 159 and 165.

Johnson, “Gershwin's ‘American Folk Opera’,” vol. 1, 152–54.

Raymond Knapp, The American Musical and the Formation of National Identity (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2005), 199.

Private communication from Wayne Shirley, who informed me that in the first production, the band played onstage at the end of Act 2, sc. 1, R107–18, inclusive.

Beyond the presence in both operas of a lullaby, a fugue, a mock sermon, and an out-of-tune upright piano, the greater relevance of these parallels and others is to be found in the ways in which Gershwin situated them in comparable musical contexts. Given the ample evidence that Gershwin was acquainted with Wozzeck, I assume him to have been aware of the dramatic as well as musical points shared by Berg's opera and his. Indications in his music acknowledge this common ground, regardless of the substantial stylistic differences. My comparison is based on the version Gershwin published in the 1935 piano vocal score and thus does not take into account the cuts he made later as a result of rehearsals and performances in Boston and New York.12

On these cuts, see Charles Hamm, “The Theatre Guild Production of Porgy and Bess,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 40/3 (Autumn 1987): 495–532.

Many of the musical resemblances mark elements of drama that are present in both plots (Appendix 1 presents a list of similarities between the two operas). Because the story of Porgy and Bess was based on the novel Porgy, by DuBose Heyward (1925) and the subsequent play that Heyward and his wife, Dorothy, staged in 1927, many of these dramaturgical moments existed before the operatic version. These include such central moments in the stories as the murders, which are accompanied in both operas by lengthy pedals (Appendix 1, no. 5). Likewise, the drownings (Appendix 1, no. 11): as Wozzeck slips into the lake, Berg supplied chromatic rising six-note chords in quintuplets; for Jake's drowning, Gershwin wrote storm music that grows to a climax with chromatic six-note chords in sextuplets. Above the chromaticisms played in the orchestra, the singers onstage speak: Clara cries out, “Oh Jake, Jake,” and the Doctor and Captain (Hauptmann) comments on suspicious sounds coming from the lake. Dramatically the settings have completely opposite characters: in Porgy the storm music is fast and loud, and in Wozzeck the scene is a clear, still moonlit night; thus the dynamics never get above pianissimo. For each of these moments, Gershwin's musical debts to Berg involve significant turns of plot that were already present in Wozzeck and in both the novel and play versions of Porgy.

In some cases, however, Gershwin constructed musical links to Wozzeck at moments of the narrative that had not existed in the Heywards' Porgy, suggesting that Gershwin drew on dramatic as well as musical ideas from Wozzeck. The mock sermon (Appendix 1, no. 8) is one such moment; another is signaled by one of Gershwin's few motivic allusions to Wozzeck, an allusion made despite the vast stylistic gulf between Gershwin's melodic world and Berg's. After Bess has given in to Crown's violent advances, she sings, “I wants to stay here, but I ain't worthy,” to the motive that Berg had assigned Marie, in exactly the same circumstance; namely, remorse after having been forced to have sex with a violent man. As shown in Example 1, Marie sings “Bin ich ein schlecht Mensch” (Am I a bad person?) to four rising thirds that span a major ninth.

Example 1. Examples 1a and 1c from Berg WOZZECK © 1931 by Universal Edition A.G., Vienna. English Translation © 1952 by Alfred A. Kalmus, London, W1. © renewed. All Rights Reserved. Used by permission of European American Music Distributors LLC, U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition A.G. Vienna. Example 1b from Porgy and Bess, by George Gershwin, Dubose and Dorothy Heyward, and Ira Gershwin. © 1935 (Renewed 1962) George Gershwin Music, Ira Gershwin Music, and Dubose & Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund Publishing.

When she returns within moments to answer her own question, “Ich bin doch ein schlecht Mensch” (I am indeed a bad person), she sings the motive in retrograde with the same pitches later used by Gershwin, excepting one chromatic inflection, D-flat in place of C. Motive, text, and context (to which I will return) are all at play in this allusion.13

For this to have been an actual allusion requires that Gershwin had access to a translation (or translator) of the libretto for Wozzeck. The program for the Philadelphia production included a full translation into English by Reginald Allen. See Barry Brisk, “Leopold Stokowski and Wozzeck: An American Premiere in 1931,” Opera Quarterly 5/1 (Spring 1987): 71–82, esp. 76–77.

Aside from individual musical gestures such as these, Porgy and Bess also contains extended passages that combine related dramatic events with a more encompassing indebtedness of musical structure and context. Appendix 1 is a list of the numerous similarities between the two operas, including those between the lullabies, the fugues, the sermons, and the scenes in which Bess and Marie are attacked sexually. To summarize:

- The lullabies each follow music played onstage in fast duple meter and, at their conclusions, a new motive of central importance is briefly introduced, a motive that later accompanies death; further, the lullabies recur multiple times, with analogous variations introduced in their reprises.

- The fugues are preceded by extended music in which the fugal ideas are presented and developed in advance.

- The mock sermons share internal details and occur in the midst of dancing and choral singing.

- Bess and Marie are coerced into having sex in scenes that relate in pacing, pitch, and counterpoint.

Evidence that Gershwin intended these debts to Wozzeck, that he expressed a desire to compose an “American Wozzeck,” will lead in turn to the critical issue of how we are to understand his use of Wozzeck. In what sense did Berg's opera serve Gershwin as a model? It is one thing for Gershwin to use an earlier work as a technical or pedagogical aid to help him in this ambitious and, for him, new undertaking, but quite another to exploit it for a source of allusions that would affect how Porgy and Bess might be understood. The distinction is not simply a matter of deciding whether or not Gershwin sought assistance in matters of compositional technique or allusive sources for his music ideas; the distinction also has implications for speculation about whether Gershwin's intention was that some of his audience would recognize moments of indebtedness.

The Lullabies

Of all the moments that can be compared, the richest is between the lullabies “Summertime” and “Mädel, was fangst Du jetzt an?” that Clara and Marie sing to their infants as they rock them. Allen Forte has examined certain connections in detail, beginning with the observation that the two arias “share certain characteristics. Of these, perhaps the most apparent are the two-chord oscillation and the contour similarity of the opening melodic figures that set ‘Summertime’ and ‘Mädel,’ respectively. Moreover, the voice leading of the oscillating chords is similar: those of Gershwin progress by parallel whole steps. while Berg's are connected by half step, the two upper parts moving in contrary direction to the lower two.”14

Forte, “Reflections,” 153–54.

Ibid.

These resemblances are of limited interest in part because they are themselves limited: clearly, Gershwin did not need assistance writing a lullaby, and the style of a German expressionist lullaby would be of no great relevance to the African American milieu Gershwin wanted to create. But additional traits suggest what Gershwin felt he could learn from Berg. First, both lullabies return more than once in the opera, and because these returns each make analogous adjustments, the ways in which they return are significant (Appendix 2 compares the lullabies and their reprises). Second, the lullabies have comparable musical-dramatic settings. They are preceded by music that ensures maximum contrast: in Porgy, Clara sings the lullaby after the “Jasbo Brown Blues” in cut C, performed with an onstage piano, while in Wozzeck Marie's lullaby follows the military music, a raucous march in 4/4 with an onstage band.16

Although Gershwin referred to “Jazzbo Brown,” I follow the spelling “Jasbo” used in the typescript libretto, the published score, and earlier references by Heyward.

The parallels in approach to the lullabies are followed by others at the conclusion. While Marie and Clara sing their final measures, the orchestra (and in Porgy and Bess, also the choir) descend by half step, either for a fifth or a tritone (Wozzeck, Act 1, mm. 398–403; Porgy, Act 1, R21+2). Following the last cadence, the arias exploit a fragment of the opening melody as the source of an instrumental coda. The melodic fragment appears twice and then quickly twice more in a compressed, elided form pitched an octave lower. Berg and Gershwin then introduce a motive of central importance that eventually becomes associated with death. As Willi Reich described it for Wozzeck, from the instrumental coda “a cadential transition … is developed as an ending, one of the most important motifs of the opera. The open fifths represent the somewhat aimless waiting of Marie, a waiting that is terminated only by her death.”17

Willi Reich, “A Guide to Wozzeck,”The Musical Quarterly 38/2 (1952): 10. This had previously been published in Modern Music, November 1931.

Ibid.

Gilbert, The Music of Gershwin, 194.

Both operas thus have the following events in succession: a dance or march played on stage in loud 4/4 or cut time, followed by a lullaby (with various points in common) and subsequently a brief truncated statement of a central motive. These introductory statements then give way to an extended segment of music without arias, songs, or any of Berg's repetition-based instrumental forms. After Reich describes the interruption of the motive associated with Marie, he continues: “From here on the musical structure abandons all formal schemes of unity and suggests the free, unconstrained technique of composition of the post-Wagnerian style, which was so prone to develop long stretches of the text in this manner, using the leitmotif only as a means of support. I emphasize this particular idiosyncrasy here, because it is the only place in Wozzeck where it occurs.”20

Reich, “A Guide to Wozzeck,” 10–11.

In Porgy and Bess, the next two statements of the lullaby were additions to the opera; that is, in the play Porgy the lullaby had appeared only twice, once each in the first and final acts. The kindred variations between the multiple reprises of the lullabies by Berg and Gershwin thus introduce into Porgy dramatic as well as musical elements from Wozzeck. Although less prolonged, Gershwin's musical shadowing of Berg is nevertheless evident because of some changes that appear in both operas, shown in Appendix 2. At the first return there is only one verse, sung against an active, blatantly intrusive counterpoint (impassioned craps shooters in Porgy and Bess, a fortissimo violin line marked “wild” in Wozzeck), and the lullaby fails utterly; that is, the baby does not fall asleep. Also, in this reprise and the next, the orchestral preparation of the singer's first note is shortened, and shortened comparably: one or two measures for the first reprise, three for the second (Appendix 2, no. 3).

The second reprises also have musical interjections, in this case disconnected outbursts that import sounds from the surrounding musical context: in Porgy, the lullaby follows a musical depiction of wind, gusts of wind then arise every few measures within the lullaby, and the wind resumes momentarily at the end. This device emulates a sequence in Wozzeck in which a polka precedes Wozzeck's parodistic rendition, the pianist repeatedly attempts to play during Wozzeck's singing, and the polka starts anew when Wozzeck breaks off. Lastly, the final reprises of the lullaby are sung not by Clara and Marie but by Bess and Wozzeck. Since this vocal transfer also occurred in the play, it does not by itself indicate anything about Berg's potential influence on Gershwin. But significantly, Gershwin and Berg once again exit the lullaby as they had the first time, by recalling the same portentous motives they had introduced after the first lullabies. Moreover, another detail of Berg's last reprise is taken over literally by Gershwin, namely the segue to the lullaby from an out-of-tune onstage piano playing 2/4 music. This sequence he adopted for the first statement in Porgy, Act 1, sc. 1.

The Fugues

Although the “crap game fugue” has justifiably been compared to the fight fugue in Wagner's Die Meistersinger, it also shares several elements with the fugue in Wozzeck (Appendix 1, no. 3b).21

Johnson, “Gershwin's ‘American Folk Opera’,” vol. 2, 525 n. 145.

Gershwin's less pervasive counterpoint is difficult to compare to Berg's, but in addition to presenting Crown's leitmotive in inversion, Gershwin's crap game theme includes a melodic palindrome that compares to the retrograde figures heard in Wozzeck. Indeed, this idea loosely echoes Berg's Hauptmann motive, especially in the rhythms and pitches of the last notes, shown in Example 2. Wayne Shirley, who has noticed the resemblance between these two themes, concluded that this motivic debt was highlighted by Gershwin, by virtue of how he emulated Berg's orchestration. While Berg assigned the motive to an English horn, Gershwin scored it for several instruments, but almost always assigned the English horn “one dynamic level higher than the other instruments” (a shading no recorded performance has achieved).22

Letter from Wayne Shirley to the author, 18 January 2005. I am very grateful to Shirley for sharing with me his thoughts and also several pages from his yet unpublished edition of the opera. Shirley also has compared the retrograde use of this theme to Berg's retrograde techniques in the third movement of the Lyric Suite. In his “‘Rotating’ Porgy and Bess,” in The Gershwin Style: New Looks at the Music of George Gershwin, ed. Wayne Schneider (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 34 n. 30, Shirley noted his first impressions of seeing Gershwin's sketches: “When I first saw sketch B I immediately thought of this section of the Lyric Suite.”

Example 2. Example 2a from Porgy and Bess, by George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and Ira Gershwin. © 1935 (Renewed 1962) George Gershwin Music, Ira Gershwin Music, and Dubose & Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund Publishing. Example 2b from Berg WOZZECK © 1931 by Universal Edition A.G., Vienna. English Translation © 1952 by Alfred A. Kalmus, London, W1. © renewed. All Rights Reserved. Used by permission of European American Music Distributors LLC, U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition A.G. Vienna.

Example 3. Example 3a from Porgy and Bess, by George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and Ira Gershwin. © 1935 (Renewed 1962) George Gershwin Music, Ira Gershwin Music, and Dubose & Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund Publishing. Example 3b from Berg WOZZECK © 1931 by Universal Edition A.G., Vienna. English Translation © 1952 by Alfred A. Kalmus, London, W1. © renewed. All Rights Reserved. Used by permission of European American Music Distributors LLC, U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition A.G. Vienna.

Sermons and Abductions

Like the fugue, the mock sermon “It ain't necessarily so” is an addition to the opera that had not existed in the novel or in the play, and is one of the Broadwayesque song texts that Ira Gershwin wrote, evidently with little or no input from Heyward. Wozzeck seems musically and textually a model. Gershwin's marking that this sermon should be sung “Happily, with humour” may have been influenced by Reich's description of Berg's setting as a “good-natured parody of a sermon,”23

Reich, “A Guide to Wozzeck,” 16.

The poetic structure of the mock sermons is in both cases a succession of examples that illustrate an initial thesis. In the sermon that George Gershwin commissioned from his brother Ira, Sporting Life presents five improbable stories from the Bible as evidence of why “it ain't necessarily so.” In Wozzeck, the First Apprentice asks rhetorically “Why, then is man?” and answers, “It is good so.” He then lists occupations that depend on other human beings: the farmer, the caskmaker, the tailor, the doctor, etc. The sermons are both in 4/4 time and include quarter-note triplet motion, Gershwin pervasively, Berg twice. Berg and Gershwin also create duple syncopations within triplets by adding grace notes to a line that in any case already oscillates between two notes. After listening to the sermon the dancers resume. This event leads in Wozzeck to the idiot's omen of death and in Porgy and Bess, to Serena shaming the dancers while the orchestra plays an additive rhythmic motive (in the right hand of the piano vocal score) that is related to the rhythmic-chordal motive that accompanies the deaths of Crown and Robbins.

The scenes in which Crown forces sex on Bess and the Drum Major does the same to Marie have some of the closest dramatic parallels between the two operas (Appendix 1, no. 9). Reich's description of this scene's significance in Wozzeck befits the situation in Porgy: “It is the most important in the development of the plot, for here Marie is seduced by the Drum-Major, an event that is the immediate cause of the conflict and tragic catastrophe.”24

Ibid., 12.

Example 4. Example 4a from Berg WOZZECK © 1931 by Universal Edition A.G., Vienna. English Translation © 1952 by Alfred A. Kalmus, London, W1. © renewed. All Rights Reserved. Used by permission of European American Music Distributors LLC, U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition A.G. Vienna. Example 4b from Porgy and Bess, by George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and Ira Gershwin. © 1935 (Renewed 1962) George Gershwin Music, Ira Gershwin Music, and Dubose & Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund Publishing.

By the end of this section, Berg has arrived at the turning point when Marie tries to defend herself, a pivotal moment that takes longer to reach in Porgy and Bess. Thus whereas each segment of Berg's setting has a counterpart in Gershwin's, Porgy and Bess also contains a lengthy middle section that has no model in Wozzeck. Berg's influence resumes as Bess sings, “Take yo' hands off me,” and Marie “Lass mich!” Both women enter on high F-sharp, and the intense brief struggles commence. Doubtless symbolic of the women's resistance, Berg and Gershwin follow these exclamations with imitative counterpoint at the third, both writing motives essentially on scale degrees 5 and 1, with four entries over rhythmic chordal pedals. At the moment the women yield, the thirds come together and the texture shifts to a scale of parallel triads accompanied by triplets moving in the same direction. Throughout this section, the musical dimensions are virtually identical: the matching stage directions “Her arms close around him” and “sie stürzt in seine Arme” lead rapidly to exit, curtain fall, and scene end. Gershwin's studious attention to Berg's handling of this dramatic encounter extends, as Example 1 shows, to the arias that follow, where Bess and Marie sing nearly identical motives to express unworthiness and remorse.

Other Parallels

The influence of Willi Reich's commentary is evident in two other Bergian aspects of Porgy and Bess: harmony and relative balance of the three acts. Many writers have noted the complexity of Gershwin's harmonic vocabulary in Porgy and Bess and in works written in the preceding years. The thickening of dissonance has been attributed to Joseph Schillinger's teachings, but it had begun before then, in the 1920s, about the time Gershwin discovered the music of Stravinsky, Debussy, and Ravel. I agree with David Schiff that in Porgy and Bess “the harmony often sounds like Berg's,” an assessment that need not be limited to Wozzeck but could encompass other works such as the Lyric Suite, which Gershwin knew well.25

David Schiff, Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 38.

George Perle, The Operas of Alban Berg, vol. 1, Wozzeck (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980), 133; and Forte, “Reflections upon the Gershwin-Berg Connection,” 159.

Reich, “A Guide to Wozzeck,” 4.

Example 5. From Berg WOZZECK © 1931 by Universal Edition A.G., Vienna. English Translation © 1952 by Alfred A. Kalmus, London, W1. © renewed. All Rights Reserved. Used by permission of European American Music Distributors LLC, U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition A.G. Vienna.

This chord is also prominent in Porgy and Bess, where it often appears spelled on G with a C-sharp or D-flat. Occurring first in the Jasbo Brown Blues that begin Act 1 (Example 6a, Act 1, R11), it returns frequently as the first chord of the motive associated with Crown and death (Example 6b, Act 1, R83+2; Act 2, R169; and Act 2, R255+2).

Example 6. From Porgy and Bess, by George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and Ira Gershwin. © 1935 (Renewed 1962) George Gershwin Music, Ira Gershwin Music, and Dubose & Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund Publishing.

When this motive accompanies Crown's murdering Robbins and later Porgy's killing Crown, Gershwin transposes the chord to E-flat and A, emphasizing its tritone symmetries. Granted, Gershwin and other composers had discovered this chord before Porgy and Bess, and it can also be related to the Petrushka chord, which Gershwin had used years earlier in An American in Paris (1928).28

On Gershwin's use of the Petrushka chord, see Forte, “Reflections Upon the Gershwin-Berg Connection,” 161–62.

Reich also discussed the relative length of the acts and something of their ABA formal relationship to each other: “The first and third acts reveal definite structural parallels. [They are] shorter by far than the weightier middle act…. While the second act … is a completely integrated musical structure from the last to the first measure, the form of the first and third is much freer.”29

Reich, “A Guide to Wozzeck,” 4.

Lawrence Starr, “Toward a Reevaluation of Gershwin's Porgy and Bess,” American Music 2/1 (Spring 1984): 32.

The model of Berg may have extended beyond the actual writing of the opera. Once the performances had begun, Gershwin pursued two promotional steps that Berg had taken before him: a public written statement of his goals in composing Porgy and Bess, and an orchestral suite of excerpts from the opera. Berg had written a brief account of what he had hoped to achieve with Wozzeck, an essay published in English as “A Word about Wozzeck.”31

Alban Berg, “A Word about Wozzeck, Modern Music (1927); repr. as a postscript to Reich, “A Guide to Wozzeck,” 20–21.

Ibid., 20.

“Rhapsody in Catfish Row: Mr. Gershwin Tells the Origin and Scheme for His Music in That New Folk Opera Called ‘Porgy and Bess’,” New York Times, 20 October 1935; repr. in Armitage, George Gershwin, 72–77.

Berg: “The appearance of these forms in opera was to some degree unusual, even new. Nevertheless novelty, pathbreaking, was not my conscious intention.”

Gershwin: “[Porgy and Bess] brings to the operatic form elements that have never appeared in opera…. If, in doing this, I have created a new form, which combines opera with theatre, this new form has come quite naturally out of the material.”

Berg: “I simply wanted to compose good music …. Other than that … my only intention … was to give to the theater what belongs to the theater.”

Gershwin: “I am not ashamed of writing songs at any time so long as they are good songs. In Porgy and Bess I realized I was writing an opera for the theatre.”

Berg's precedent is important as well for the orchestral suite based on the opera. As Berg assembled three concert excerpts from Wozzeck, the Drei Bruchstücke aus “Wozzeck,” so Gershwin also extracted several numbers as an orchestral composition, which he never published, however. He titled this five-movement composition “Suite from Porgy and Bess,” incorporating many of the segments he had cut from the Boston and New York performances, such as the “Jasbo Brown Blues” leading in to “Summertime,” portions of the fugue and hurricane music, and the children's chorus.34

See Johnson, “Gershwin's ‘American Folk Opera’,” vol. 2, 597–99. This work has been known as the “Catfish Row Suite” since Ira Gershwin gave it that name in 1958.

Ibid., 598.

Gershwin's numerous debts to Berg's music necessitate a reevaluation of what Gershwin might have learned at the hands of New York City's composition guru, Joseph Schillinger. Many stylistic details that have been presumed to originate in study sessions with Schillinger can now also be attributed to the example of Berg, not only the music of Wozzeck but also that of the Lyric Suite. In an article reviewing the claims of Schillinger's influence on Porgy and Bess, Paul Nauert concludes that the evidence for Gershwin's debt to Schillinger was strongest “in the cyclic harmony of ‘Gone, Gone, Gone’ and the elaborate rhythmic patterning of ‘Leavin’ for the Promise' Lan'.”' Other moments, such as the fugue, the additive chords leading up to “Summertime,” and various rhythmic devices also have possible sources in Schillinger's method.36

Paul Nauert, “Theory and Practice in Porgy and Bess: The Gershwin-Schillinger Connection,” The Musical Quarterly 78/1 (Spring 1994): 9–33. See also Warren Brodsky, “Joseph Schillinger (1895–1943): Music Science Promethean,” American Music 21 (2003): 45–73.

Among these are the following: the additive fourth chords preceding “Summertime” appear in Wozzeck (I, mm. 621–23) over a similar syncopated rhythm; chromatic wedges with outer voices spreading outward by half step are common in both, but the first instances in each opera share numerous pitches (Porgy and Bess, I, sc. 1, beginning at R7+1; and Wozzeck, I, mm. 252–56); also occurring frequently, rhythmic deceleration (or acceleration) in which note values increase (or decrease) incrementally, as when triplet sixteenths slow to triplet eighths and then to a pair of eighth notes (e.g., Porgy and Bess, I, sc. 2, R187–2; and Wozzeck, I, m. 711); what Schillinger calls “interference between melodic grouping and attack rhythm,” a technique present in both operas in a variety of disjunct patterns, as when a four-note melodic figure repeats within a rhythmic sextuplet pattern, so that the attack-point continually shifts within the pattern (e.g., Porgy and Bess, II, sc. 4, R238+5; and Wozzeck, III, mm. 278–79); and complex metric textures, as triplet sixteenths against thirty-second notes grouped in fours (e.g., Porgy and Bess, I, sc. 1, beginning at R108–1; and Wozzeck, III, beginning at m. 90. In this case there are other links of motive and pattern, including their graphic representation on three staves in the piano-vocal score).

Forte, “Reflections,” 164.

For much of Porgy, Gershwin had no need to ask what Berg had done before him. Because he was setting English rather than German, because he needed to draw on American popular and folk musical forms rather than on German forms, Gershwin had nothing to learn from Berg about melody and text setting. In these areas he was already an acknowledged master. The examples that I have presented here suggest that Gershwin carefully studied Berg's approach to scene construction (i.e., how to integrate a song into an evolving, ongoing musical context), and his techniques of unification across great stretches of time (i.e., how to repeat ideas, whether motives or larger units). He turned to Wozzeck for musical guidance at several dramatically significant moments of the opera. The murder of Robbins, the drowning of Jake, the lullaby and its reprises, the abductions of Bess and Marie, the fugue and crap game music, and several other events all derive details of structure from Wozzeck. That some of these moments had not existed in either Heyward's novel Porgy or the subsequent play further suggests that Gershwin considered these elements to have been particularly effective. The mock sermon in Porgy and Bess has no precedent in the Heyward play Porgy, nor do the multiple repetitions of the lullaby or the importance of children (and children's chorus) at the end. For these and for numerous musical details, Berg was Gershwin's model.

Corroboration for this conclusion comes from two previously uncited sources: a recollection by William Rosar and an interview with Gershwin. First, a secondhand report from Rosar, a scholar of film music and an acquaintance of Edward B. “Eddie” Powell, a Hollywood orchestrator who was a confidant of Gershwin's during the period in which Gershwin began to compose Porgy and Bess. In the 1930s Powell, along with Gershwin, was a student of Joseph Schillinger, and also according to Rosar, the person Gershwin hired to orchestrate his musical Let 'Em Eat Cake.39

Powell's own interest in Berg at the time (communicated to me by William Rosar) may explain an observation about the orchestration of Let 'Em Eat Cake made by Robert Kimball and Alfred Simon in The Gershwins (New York: Atheneum, 1973), 155: “The Let 'Em Eat Cake overture [1933] is particularly adventurous, recalling in its opening some of the orchestral color and near-atonal harmonies of Alban Berg's Wozzeck.” My thanks to Richard Crawford for calling this to my attention.

Going over my notes just now, I finally remembered Powell's exact words with respect to Porgy: “He [Gershwin] wanted to write it like Wozzeck, an American Wozzeck.” I remember how perplexed I was by that. In fact, I didn't believe him, because I remembered reading how Gershwin boasted that he was influenced by Ravel and Debussy in writing An American in Paris, but, as someone commented, for all intents and purposes the influence was imperceptible, and it just seemed like Gershwin was name-dropping.40

William Rosar to the author, 24 November 2004. I am indebted to Rosar for a series of e-mails about Powell and Gershwin. Rosar has already written about what Powell and Gershwin may have learned from Joseph Schillinger; see his letter to the editor of The Musical Quarterly 80/1 (Spring 1996): 182–84.

Second, buttressing our knowledge of Gershwin's high regard for Berg in general and Wozzeck in particular is an overlooked interview with Gershwin that took place on 19 June 1928, immediately upon Gershwin's return from Europe. The interview was reported the very next day in the New York Morning Telegraph, under a headline that is extraordinary because it already refers to Berg as an opera composer: “Gershwin Finds Great Opera Artist,” and, in smaller print, “Returning on Majestic Composer Tells of Thrills Abroad.”41

Morning Telegraph, 20 June 1928, 1. My thanks to Lawrence Stewart for his transcription of this 1928 article.

Like a chap who first has seen the wonders of Paris and its mysteries came George Gershwin yesterday on the steamer Majestic. He said he had the time of his life, meeting everybody in music.

When he was asked about how he felt at Paris, when the concerto [in F] was played with orchestra, he said that Dimetri [sic] Tiomkin had been wonderful, first in arranging for the performance with Goltschmann conducting, and then in the way he had played it. In the second movement, he said that he had a thrill when he heard how beautifully the woodwinds and brasses played.

In other words, Gershwin was more excited by the way Tiomkin had played and the orchestra had worked than he was about George Gershwin being heard at the Paris Opera.

There was no affectation about this. It was the real artist.

Then he glowingly told of the discovery he had made abroad. He had found a great composer! Alban Berg is his name, a pupil of Schoenberg, and the composer of an opera, but more particularly of a new string “Lyric Quartette.” He went all over Europe talking about Berg and he will continue to do so in America. Already he has interested Stokowski, conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra, to play some works of Berg.

But he was not the last. Barry Brisk reports that Stokowski's assistant conductor Sylvan Levin claims credit for suggesting to Stokowski that he stage Wozzeck. It is easy enough to imagine that both Gershwin and Levin, and perhaps others as well, independently lobbied Stokowski on behalf of Berg. See Brisk, “Leopold Stokowski and Wozzeck,” 71.

What does Gershwin's desire to compose an “American Wozzeck” mean for how we interpret the many points of correspondence? A few years before beginning Porgy and Bess, Gershwin described how he learned to compose songs, and his remarks from 1930 suggest that his emulation of Wozzeck was primarily pedagogical: “I learned to write music by studying the most successful songs published. At nineteen I could write a song that sounded so much like Jerome Kern that he wouldn't know whether he or I had written it. But imitation can only go so far. The young songwriter may start by imitating a successful composer he admires, but he must break away as soon as he has learned the maestro's strong points and technique.”43

Gershwin, “Making Music,” in the New York Sunday World Magazine, 4 May 1930; repr. in Gershwin in His Time: A Biographical Scrapbook, 1919–1937, ed. Gregory R. Suriano (New York: Gramercy Books, 1998), 77.

See Christopher Reynolds, Motives for Allusion: Context and Content in Nineteenth-Century Music (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2003). I elaborate on this definition on pp. 5–7.

There are other instances of influence and indebtedness in Porgy and Bess that can be brought to bear on this question. Two non-motivic debts have already been mentioned: the cries of the Strawberry Woman that many recognized early on as influenced by an analogous moment in Charpentier's Louise; and the crap game fugue, which Johnson has compared to Wagner's fight fugue in Die Meistersinger. That neither involves motives or themes is irrelevant for the question of allusion, because motives are but one means of marking a resemblance; similarities of musical structure and dramatic moment convey enough information for listeners to note the resemblance and to assess the significance of that resemblance for their interpretation. It is reasonable to conclude in both of these cases that Gershwin makes assimilative allusions to the earlier works, that he accepts the meanings and the authority of Charpentier's cries and Wagner's fugue and creates moments similar enough for others to make the connection.

Two additional references have not been recognized previously. Both, like these just discussed, are strongly assimilative, one of them close enough in motive to be considered a quotation. Among Eastwood Lane's Five American Dances for Piano is one titled “The Crap Shooters: A Negro Dance.”45

Eastwood Lane, Five American Dances for Piano (New York: J. Fischer & Bro., 1919).

Don Rayno, Paul Whiteman: Pioneer in American Music, 1890–1930, vol. 1 (Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 2003), 100, 103, and 398. See Olin Downes's choleric review in the New York Times, 16 November 1924, 30. Much of this review is quoted in Rayno, Paul Whiteman,103.

Example 7. Example 7a from Five American Dances, by Eastwood Lane. © 1919 J. Fischer, New York. Example 7b from Porgy & Bess, by George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and Ira Gershwin. © 1935 (Renewed 1962) George Gershwin Music, Ira Gershwin Music, and DuBose & Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund Publishing.

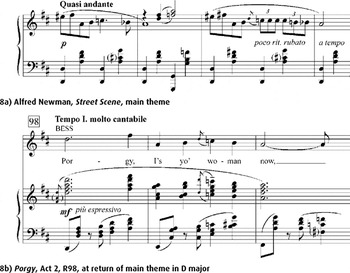

The other motivic debt, almost a quotation, is to Alfred Newman's film score for the King Vidor film Street Scene (1931). A faithful rendition of Elmer Rice's Pulitzer Prize–winning play from 1929, Street Scene takes place in a run-down Manhattan brownstone during the heat of summer. It depicts working-class life in New York City in the kind of unglamorous, unsentimentalized light that ten years later came to typify film noir. A woman's affair leads to a bloody end when her alcoholic husband returns home unexpectedly and shoots her and her lover dead. After directing several Gershwin shows on Broadway during the 1920s, Newman composed the Gershwinesque score for Street Scene soon after he moved to Hollywood in 1930 to become director of music for United Artists. His score became as successful as the film itself, appearing soon in an arrangement for piano,47

Alfred Newman, Street Scene (New York: Robbins Music Corporation, 1933).

Thanks again to Wayne Shirley for information about the full score. Gershwin's text, which was not present in the Heyward play or novel and was written primarily by his brother Ira, may also allude to Street Scene. The phrase “Mornin' time an' ev'nin' time,” is set to a falling fifth with repetitions on the lower note, a motive that Newman uses as his first contrasting theme; moreover, the film is also organized around different times of day, an organization reflected in the piano arrangement by the parenthetical designations “Morning,” “Afternoon,” and “Night.” For an analysis of the duet, see Lawrence Starr, “Gershwin's ‘Bess, You Is My Woman Now’: The Sophistication and Subtlety of a Great Tune,” The Musical Quarterly 72/4 (1986): 429–48.

Among other potential sources of influence, the African American dialect songs of Lily Strickland, a South Carolinian, seem particularly close to Gershwin's style, particularly in the recitative-like sections.

Example 8. Example 8a from Street Scene, by Alfred Newman. © 1933 Robbins Music Corporation. Example 8b from Porgy and Bess, by George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and Ira Gershwin. © 1935 (Renewed 1962) George Gershwin Music, Ira Gershwin Music, and Dubose & Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund Publishing.

In contrast to these few assimilative allusions, most of the structural debts listed in Appendix 1 show no indication of being designed to affect how a sensitive listener might interpret individual scenes in Porgy and Bess. On the contrary, evidence of Gershwin's attempts to obscure his indebtedness abounds, but lies chiefly in his avoidance of motivic or thematic references. When Robert Schumann devised allusions that distanced themselves from the original by careful variation of dynamics, tempo, meter, character, and the like, he did so to create contrastive allusions, allusions that allowed for an ironic or other oppositional reading.50

See Reynolds, Motives for Allusion, chap. 4, “Contrastive Allusions.”

But on a global level, the effect of scene after indebted scene creates a different impression. The allusive sum is greater than that of its component parts. Although Carolyn Abbate's analysis of Debussy's debt to Tristan und Isolde addresses a different degree of dependence, it is still relevant: “It [Tristan] was manipulated by the composer to become a sort of hidden commentary on Pelléas, and thereby became more than merely an obvious model for the later opera.”51

Carolyn Abbate, “Tristan in the Composition of Pelléas,” 19th-Century Music 5/2 (1981): 141.

George Gershwin, “Rhapsody in Catfish Row,” New York Times, 20 October 1935; repr. in Armitage, George Gershwin, 73.

This translation is by Eric Blackall and Vida Harford, from Alban Berg, Wozzeck, English National Opera Guide 42 (London: J. Calder, 1990), 62–63.

It is no surprise that Gershwin created a work billed as an American folk opera by lifting ideas from a quintessentially Germanic opera: first because by the 1930s the lines of artistic influence had long been crossing the Atlantic in both directions; and second because Gershwin had from the beginning of his education been schooled in European traditions. Louis Gruenberg, among others, was also attempting to mix black music with musical innovations from Europe (The Daniel Jazz and The Creation are both written for a modified Pierrot ensemble in the immediate aftermath of Gruenberg conducting the New York premiere of Pierrot Lunaire). Gershwin's friend Isaac Goldberg broached this issue when he described Gershwin's special musical position in this country. “As Gershwin does not ‘condescend’ to popular music, neither does he ‘aspire’ to the higher forms; music, to him, is music.”54

Isaac Goldberg, George Gershwin and American Music: From Tin Pan Alley to Opera House and Symphony Hall (Girard, Kans.: Haldeman-Julius Publications, 1936), 27.

Knapp, The American Musical, 196. David Metzler discusses representations of race in Gruenberg's opera in “‘A Wall of Darkness Dividing the World’: Blackness and Whiteness in Louis Gruenberg's The Emperor Jones,” Cambridge Opera Journal 7/1 (March 1995): 55–72.

Gershwin aimed to write music that would survive, as he stated unambiguously in his 1935 New York Times essay on Porgy and Bess. “I chose the form I have used for Porgy and Bess because I believe that music lives only when it is in serious form. When I wrote the Rhapsody in Blue I took ‘blues’ and put them in a larger and more serious form. That was twelve years ago and the Rhapsody in Blue is still very much alive, whereas if I had taken the same themes and put them in songs they would have been gone years ago.”56

George Gershwin, “Rhapsody in Catfish Row,” New York Times, 20 October 1935; repr. in Armitage, George Gershwin, 74.

Gershwin, “The Composer in the Machine Age,” 267 and 266.

Here in one sentence is Gershwin's explanation of why Porgy and Bess can be at once an American folk opera and an American Wozzeck. Only by combining American folk content with “form in the universal sense” could he create a music that he felt would endure. Charles Hamm, discussing the problems of creating an image of Gershwin that goes beyond the protective biographical accounts of family friends and acquaintances, also cited Gershwin's New York Times article on Porgy as well as his essay on “The Composer in the Mechanical Age,” concluding that “nothing more than these tantalizing scraps of information are available to help us reconstruct Gershwin's ideology.”58

Hamm, “Towards a New Reading of Gershwin,” in The Gershwin Style: New Looks at the Music of George Gershwin, 10.

Appendix 1

Comparison of Musical Parallels Between Porgy and Bess and Wozzeck

The events are ordered according to their appearance in Porgy and Bess. Locations within the piano-vocal scores are specified by rehearsal number in Porgy and by measure number in Wozzeck.

Appendix 2

Comparison of the Lullabies and Their Reprises