Ancient artefacts enlighten us about the world and about past peoples. That is the object of museums and their objects, which is too often forgotten

in these present-day battles over the rights and wrongs of history.(Jenkins Reference Jenkins2018)

A face in an attic

Like other success stories—see the story of Oliver Cromwell’s or Henry IV’s heads—this story also begins in an attic. One summer’s day in 2010, while cleaning the loft of the 1930s building of the Francisc Rainer Institute of Anthropology (Bucharest), some of my colleagues stumbled upon “a mask.”Footnote 1 This space had been used for storage for seventy years, and its contents reflected the history of the Institute’s cultural and physical anthropological research. It was a history in which anthropology was intertwined with biology and anatomy, medical teaching with anthropological field campaigns, and the creation of a craniological collection with archaeological excavations. Thus, in the meanders of this dimly lit place, one could find medieval skeletons and the bones of prehistoric bears, archaeological materials and patients’ interview charts that had long ago lost their context. There were anthropological photographs and instruments from the 1920s that had served a purpose no one could now remember, unused laboratory equipment, tubes and Berzelius glasses, next to skulls and archival documents.

While sorting through these materials, and peeling off the layers of the history of the Institute, in one of the wooden crates, among papers and photographs, my colleagues touched what they thought to be a wax mask. However, close inspection revealed it to have a “curious” texture, and in daylight they were surprised to discover that it was in fact a “real” human face. Upon consulting the published works of the anatomist and anthropologist Francisc I. Rainer (1874-1944), the founder of the Institute, we discovered that this face had been designed to showcase a unique method devised by him at the turn of the century to preserve human tissue (fig. 1).

Figure 1. The face (a) anterior view, (b) posterior view. Collection of the Francisc I. Rainer Institute of Anthropology.

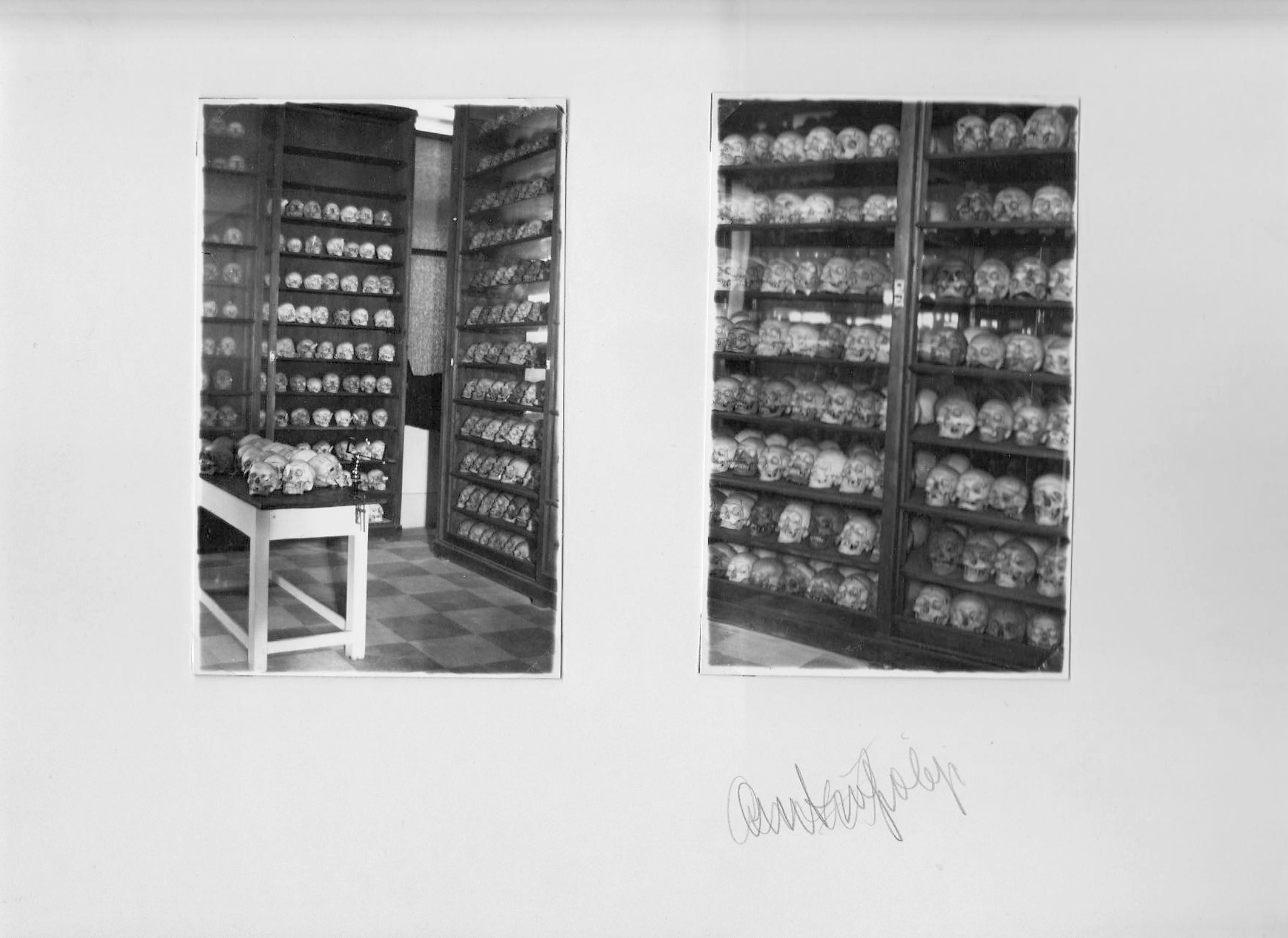

The face itself is part of a larger collection comprising approximately 6000 skulls gathered in the first four decades of the twentieth century, as well as archaeological skeletons, documents, and photographs, all part of a legacy from the early days of anthropology in Romania (see Ion Reference Ion2011, Reference Ion2014, Reference Ion2015 for a history of the collection and the museum) (fig. 2). After Francisc Rainer’s death in 1944, some of the materials were slowly lost, while others found their way to the attic. When the Institute moved in 2016, all of the remaining materials were packed in boxes and placed in storage. This is not a singular story, and it illustrates a wider trend that is bound to affect the way in which future generations will view human remains as scientific and museum objects.

Figure 2. Two photographs of the Francisc I. Rainer collection, interwar period. Collection of the Institute of Anthropology Francisc I. Rainer.

“What should we do with anatomical collections and their specimens, models, jars, vitrines, storage and exhibition spaces? They were once made, and re-made, and remade again. What should we ‘make’ of them now?” asks historian Michael Sappol in a Reference Sappol2016 book review (874). This is precisely the question this article aims to explore. In it, I aim to reflect on the fate of this special kind of scientific object—collections of human remains —and their place in contemporary times. To achieve this, I will take the theme proposed by Jaume Navarro for this special issue, namely the “deaths” of scientific objects, into the territory of anthropology. In spite of the public’s interest in exhibits of human remains, the existence of such collections has come under threat. In the face of financial pressures, new ethical standards, or the loss of specialists, such collections have been “dying”—slowly fading out of the public sphere, and suffering, to quote Mat Paskins, “a loss of meaningful future” (personal comm.). This process has taken several forms, as remains are repatriated, reburied, hidden behind locked doors, or even unceremoniously “downsized” and discarded.

On the other hand, the specimens within these collections continue to puzzle and fascinate us. They confront us with our own mortality, they raise questions and challenge the relationship we have with our own bodies. Like the face from the Rainer collection, they make the interior of the human body visible, while at the same time collapsing the boundary between individual-body-artefact. Thus, we seem to witness a fascinating situation: on the one hand certain types of human remains collections have become dying scientific objects. The world which gave rise and context to them has died and the principles ordering them are being challenged. At the same time, some of the specimens still survive, and continue to be a source of wonder and morbid interest.

In order to capture this complex status of human remains collections, I will begin with the story of the face from the Francisc I. Rainer anatomical-anthropological collection. I will then make the case for approaching human remains collections as modern ruins, which allows us to think of them as places of absence, pointing to unfinished lives, and unfinished scientific projects. This makes them strange and important at the same time; as historian Ewa Domanska wrote about the material presence of the past: “the disappeared body is a paradigm of the past itself, which is both continuous with the present and discontinuous from it, which simultaneously is and is not” (Reference Domanska2006, 337). Lastly, I will discuss more widely the kinds of factors and events that lead to the demise of such collections and create these “ruins,” and propose alternative ways of dealing with these legacies of the past, asking “What do we want to preserve, and why?”

There are, of course, differences between kinds of human remains collections, be they archaeological, anatomical or anthropological. In this text, I will focus on anatomical-anthropological collections comprising the remains of modern Europeans. This is a particular category that took shape in the second part of the nineteenth and early twentieth century, when collectors were both anatomists and anthropologists, and saw a continuity between the two disciplines. For this reason, I choose to include such mixed collections in my story, as it is hard to disentangle specimens into clear-cut categories. Archaeological specimens have found their way into museums, and their status is involved in debates of a slightly different kind, which will not be the topic of this article. Anthropology collections comprising ethnography specimens—such as shrunken heads, Maori heads, and other trophies from colonial empires—also have their particular itineraries, and are currently part of postcolonial debates which will not be discussed here. However, the ultimate aim of this article is to prompt reflection, rather than writing a history of any one category.

The anatomist and the specimen

The story of how this face came to reside in the Rainer Institute’s attic encapsulates various stages of forgetting materialized in flesh, both in the past and in the present. It is a narrative in which memory and history compete over the territory of disciplinary identity. Very little information has survived regarding the history of the face or Francisc Rainer’s interest in it, except for a short article by one of his students and a handful of anecdotes (Rainer Reference Rainer1945). Therefore, it is not easy to contextualize the face, especially when most of Rainer’s scientific ideas that are known to us date from twenty years after the face’s preservation. However, the human body was central to Rainer’s anatomical-anthropological theories—serving as a core around which he constructed a specific research philosophy.

Francisc Rainer was an anatomist and anthropologist who is primarily remembered for introducing the concept of functional anatomy and experimental embryology in Romania (Toma Reference Toma2010, 157). But he was also the head of the Anatomy School at the Faculty of Medicine, and founder of a Museum and Institute of Anthropology in 1940 (Ion Reference Ion2014). He was born in Bucovina, part of the Austrian-Hungarian empire, in a mixed household—his father was Austrian and his mother was Romanian. He came to Bucharest to enroll at Saint Sava high school, where he was particularly interested in ancient Greek and Latin. He then went on to study at the Faculty of Medicine in 1892, and after graduating became a junior teaching assistant at Colțea Hospital, one of the main hospitals in Bucharest, placed right in the heart of a city in full process of modernization.

It is here that the fate of an anonymous young man’s body became intertwined with that of Rainer, at the turn of the twentieth century in Bucharest, when the anatomist was still a young laboratory assistant at Colțea Hospital. The hospital contained approximately 260 beds, installed in twenty-three rooms, outbuildings, and an autopsy room (Galeșescu Reference Galeșescu1900, 597). In 1869, Eforia of the Civil Hospitals founded a pathological museum in the hospital, which included “monstrous bodies that presented medical and scientific interest and were very helpful, with the demonstrations made to serve the students” (Galeșescu Reference Galeșescu1900, 627). Thus, some of the dead bodies in the hospital were repurposed as material for dissection, or museum specimens. Due to Rainer’s own interest in understanding anatomy in its finest details, he combined dissection and the study of anatomical elements with creating embryology preparates, and sought better methods for preserving the human body for these studies. It is probably for this reason that he began experimenting with a technique for preserving the human body, which would allow him to preserve bodies for an indefinite period. So, when the anonymous young man died, around 1900, of pulmonary tuberculosis in the Colțea Hospital, the anatomist had found a good candidate for testing his method.

It was not uncommon for the corpse of a tuberculosis victim to be used for anatomical study. In the Francisc Rainer osteological collection there are over 700 such individuals, 20 per cent of the total number of individuals (Ion Reference Ion2011). Tuberculosis, associated with poor living conditions, was one of the main causes of death from a disease in late nineteenth–early twentieth century Romania. But how was the circumnavigation of this dead body’s death achieved? And how was the identity of this specimen shaped in a process that transformed a “standard” anatomical cadaver into an artefact?

Death marked a change in the status of this young man, shifting his body from the medical sphere to the anatomical one. In this particular case, after dissecting his cadaver, Rainer cut away the anterior part of the skull and subjected it to several material transformations, with the goal of creating a specimen to illustrate a new preservation technique. From an anatomical point of view, Rainer’s method is part of a long history of experimenting with techniques for preserving specimens in as “life-like” a manner as possible (e.g. Sawday Reference Sawday1995; Alberti Reference Alberti2011; Knoeff & Zwijnenberg Reference Knoeff and Zwijnenberg2015), ranging from seventeenth-century European anatomical specimens preserved to resemble Egyptian mummies (Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Boston, Chamberlain, Chaplin, Chauhan, Evans, Fowler, Powers, Walker, Webb and Witkin2011), to wax models (Riva et al. Reference Riva, Conti, Solinas and Loy2010), to the discovery of formaldehyde in 1869 by August Wilhelm von Hofmann. By the late nineteenth century, the use of formaldehyde had become a common practice (Brenner Reference Brenner2014, 324), but Francisc Rainer developed a new technique designed to preserve the integrity of an entire human body (with flesh and hair) in plain air, not the human body as a dissected subject. We are not, however, sure how precisely this would have worked, as we only have the face as a testimony to his experimentation.

To take a small detour, what we do know is that at the turn of the century there existed in Bucharest a wider interest in experimenting with new techniques inside the boundaries of a medical education. A similar case is known at the Mina Minovici National Institute of Legal Medicine, where a preserved body gives testimony to this history:

About our mummy “Costica” circulated all sorts of legends. One of them said that it was the first porter of the Institute. From the research that I’ve done I have learnt that he was a simple man, homeless, whose body was ceded by the municipality to Mina Minovici as he had no family, who turned it into an incredible thing. Thus, the beggar became one of the most famous people of the time. Minovici put this body through an original process through which he managed to transform the ordinary body into a mummy. It is remarkable that he did everything with the organs still intact. (Curca Reference Curca2003)

In the particular case of the face, the information about the process was published by Rainer’s student only about fifty years after the event, which raises some questions about its validity. Even so, it seems that Rainer’s source of inspiration was the infusion of tissue samples with paraffin used in histology. As described in the article (Rainer Reference Rainer1945), the anatomist immersed the front section of the head in a series of ethanol solutions (of 96 and 99-100 degrees) to obtain a complete dehydration. This phase lasted for at least thirty days. He then immersed the dehydrated piece in xylol and left it for an equal period of time. Later, the face was put in a prolonged bath of xylol-paraffin, and finally in a pure paraffin bath. The temperature of these baths was determined according to the melting point of the wax used. After immersion, he exhibited the piece outdoors and removed the debris remaining on the surface with a scalpel and a pad soaked in xylol. What is unknown is whether this was the only specimen Francisc Rainer created, or how he intended to use it.

After the professor’s death, the face eventually found its way to the Institute’s attic, in a box along with other documents belonging to Rainer, where it was forgotten until 2010. The only other account of this face appears in Mihail Sevastos’ account of Rainer’s work (Reference Sevastos1946, 55), where philosopher Mircea Vulcănescu remembers how Rainer once showed some visitors at the Institute of Anthropology “a mummified mask,” as he describes it, which the professor dropped on the floor so that the students could note how its features remained unaltered. This incident is particularly interesting as it raises the question: why would it be relevant to preserve, unaltered, the features of an individual? Was the choice of the body part that Rainer decided to preserve relevant? Was the created artefact a mere sample of his conservation method, which could then be applied to other body parts, or was it more than that?

How bodies become artefacts

What is certain is that in order to understand this specimen, we need to understand the context of the transformation through which Rainer turned individuals’ bodies into specimens. This “processing” of bodies took place in a wider world of new technologies and administrative-institutional organization in turn of the century Bucharest: the creation of a modern anatomical museum and a reorganization of anatomical teaching. It was a world populated by a diverse array of materialities, which are now forgotten when we approach specimens or collections, but which once imbued those specimens with meaning. In Rainer’s case, the transformations took place in the spatial context of a “cadaver service,” where the anatomist intervened upon the materiality of the deceased’s body, exposing what was important for anatomical teaching and research, either muscles, bones etc.

Additional information regarding the transformation process can be extrapolated from what we know of the cadaver service Rainer built and used starting with the late 1920s. By that time, Rainer had become professor of anatomy at the Faculty of Medicine, and was already making plans for the establishment of an Institute of Anthropology where he could dedicate his research to the study of humans in all their forms. The Institute’s building shared a courtyard with the Faculty of Medicine and housed the cadaver service in its basement. Once a dead body entered the space he had imagined, it started a journey of transformation through four rooms: a cleaning room, an embalming and preserving room, rooms for maceration and the crematorium (Tudor Reference Tudor1947, 56). In this space, anatomists broke the boundaries between artefact and body by mixing organic matter with a world of artificial materialities: they brought flesh and skin into the universe of metal instruments, wooden laboratory tables, ceramic tiles, fridges, and the metal of the crematorium. From that space, these bodies-as-dissection-materials would emerge, when needed, for use in the dissection laboratories of the Faculty of Medicine. Following this, some of them returned to the maceration room to become anthropological specimens, while others ended their biography in the crematorium.

The types of specimens that Francisc Rainer and his students prepared are reflected, for instance, in an inventory published in 1947 (Tudor Reference Tudor1947)—a list of fragmentary and defleshed bodies, with their circulatory system, glands or organs being brought into view. In this period, the boundary between the disciplines of anatomy and anthropology was rather blurred, and the inventory comprises elements of both. If materials were deemed interesting for anthropological research, the scientists enforced their status as archival objects by marking them in ink and on paper before they made their way to the upper floors of the Institute’s building where the craniological collection was on display. Each skull or bone sample had a paper index card that contained their “identification” details, all of the data deemed relevant for anthropological studies: the age, sex, cause of death, profession, and ethnicity of the deceased. Thus, social identity was inscribed on the bone and written on paper, creating complementary records, one embedded in the bodies’ materiality, and the other stored in filing cabinets. The pathologically interesting specimens, like the elements of the vertebral column or skull fragments, were fixed with metal rods and threads, attached to wooden bases and displayed in glass cabinets, or placed in neatly ordered shallow wooden boxes. Alongside the x-rays, charts, photographs and recording sheets, they comprised an anthropological-anatomical archive of the Romanian people in particular.

Further up in the building, Rainer assigned each specimen to a certain display case and room, depending on the scientific idea they illustrated: the route through the building, the architecture of which was specially adapted to the scientific universe it housed, took one from the craniological collection room, to a mixed-specimens (casts and skeletons) archival room, past a cabinet of photography and then an x-ray room, and finally towards the morphology variation, pathology and micro-biology displays (see Ion Reference Ion2014). Thus, the face gains meaning as part of a visual archive of human morphological variation, structured in space. It is also part of a world in which the preservation of cadavers, their study and display all happen under the same roof, and the boundary between laboratory and museum is absent.

Why, then, was it put away? After Francisc Rainer’s death in 1944, which almost coincided with the beginning of the communist regime, the Institute, along with his legacy, went through several reorganizations. The most important of these was a change in paradigm which witnessed the separation between anthropology and anatomy. In this new world, focused either on cultural anthropology field campaigns, the study of historical skeletons or of living people, the face could not find its place and ended up in the attic of the Institute, amongst Rainer’s old papers and notes. Most probably the preservation technique that it exemplified was no longer recognized as such. When, in 2010, anthropologists stumbled upon it, long divorced from the epistemic universe which gave it birth, its ambiguous materiality made it strange and hard to look at.

Body parts as liminal “objects”

After its discovery in 2010, my colleagues placed the mask on a shelf, in the furthest corner of the room that housed the crania collection in the Institute. This was due to the fact that it was, after all, a human head, and a legacy from Rainer’s original collection. From the start, though, its status was ambiguous due to its morphology. What had made it collectable in the early twentieth century was the technique it showcased, so what was actually on display at the time was not the face itself but the technique by which it had been preserved. Today, however, in light of the extensive literature that has since been published concerning the ethics of displaying human remains, it is no longer “just” a technique, and certainly not quite like the rest of the specimens. It is a human being, and a recognizable one in that it still has skin and hair. To further complicate things, it looks more like a funerary mask than a cranium like the rest.

At the time of rediscovery, the fleshed face of a dead man made death manifest in the space of the Institute, prompting an emotional reaction which is not usually triggered by bare bones. The face did not seem to call for as anonymized a reading as one might give a bare skull. The anatomist had not “sanitized” it by framing, encasing or labelling it—as if to say “this is a specimen you can look at.” By touching and handling it, one almost felt intimate with a dead body, something which is improper. At the same time, the fact that it looked like a sample and a fragmented body part did call for a somewhat “detached” reading of the face as an example of a unique and original preservation method. Irrespective of the two readings, we could not find a place for it. On the one hand, it could not be put on display, as this felt somehow unethical (not to mention creepy). On the other hand, it could not be left with the written archive, as it was a human being.

This liminal status led to an interesting “journey” for the artefact as it travelled around the Institute after its discovery. Initially, my colleagues placed it in a recycled cardboard box with a lid, and the box was put at the back of the room where the craniological collection was displayed. From there I took it into the laboratory, in order to start writing about it, and there it remained even after I changed departments a year later. It eventually followed me to the new office space, kept hidden from my cultural anthropologist colleagues, who are not that keen on the dead. At this point, it became a body as an academic curiosity: I photographed it, wrote about it, talked about it. Images and words constituted a new phase in its biography, as they made it visible to the eyes of contemporary academics. Removed from its origins as an object to be touched or handled, the face started a new life in the pages of a manuscript and then a journal article, where its biography unfolded. The face could now be gazed upon, moved around and multiplied in a virtual world, its story becoming detached from the actual encounter with the physicality of the artefact—the very aspect which marked its creation. Ultimately, in the context of the large-scale packing involved in the Institute moving to a new building, the box holding the face ended up once again with the whole paper archive left by Rainer, reunited with plaster casts, lamellae with human tissue and photographs of embryos, waiting on the racks in the attic to be moved into the new space. In essence, the cutting and processing of bodies at the turn of the century, which in this particular case had reduced one of those bodies to a “mask,” led to a paradoxical situation: the loss of an individual’s persona, through his transformation into a scientific specimen and integration into the anonymous mass of dissected bodies, had nevertheless retained his face, the most diagnostic feature of individual identity. This paradox remained attached to the specimen, and informed its subsequent trajectory in the years to come.

But the postponed destruction of this person’s face is part of a larger story: the face was discovered during the first part of a wider cleaning process, in which the materialities of the past were confronted and evaluated to determine what would be deemed as part of an institute of anthropology and what would not. Medical instruments, “garbage”—such as used/unused utensils, papers, cardboard boxes, fridges, things that we were not even able to identify—were photographed, inventoried, and became debris. This reorganization was mirrored by a subtler transition: the skulls were cleaned and inventoried, with the information written in a database, the paper tickets that accompanied them were divorced from them, the card index was digitized, as were the articles that had been written about the artefacts. This made the accompanying materials obsolete, as were old furniture pieces, and other objects that were due to follow soon (the actual papers in the archive are covered in mold and dust after all) (fig. 3).

Figure 3. The deserted top floor of the Francisc I. Rainer Institute of Anthropology. Photograph taken after the move to a new building. Photographer: Mircea Ciuhuta (published with permission).

The implicit assumption is that these specimens are data—data that can be collected, digitized and preserved, without losing anything from the initial information. The skulls were kept, since they were considered useful anthropological material which can still provide new data. They are the only part of the initial collection that still elicits scientific interest. The archaeological bodies and body parts with no remaining information or context were buried. This face, however, remained in an epistemic limbo, as it seemed to be unique in some way. It is a one of a kind piece of a lost preservation method, which itself is quite extraordinary. We know of bodies preserved in fluids or mummified, and even petrified bodies, but in this case a different recipe was applied, one which seems to have made the piece oblivious to the passage of time. It has also, however, left it as a specimen in want of a narrative.

Human remains collections as modern ruins

The story of the face illustrates the challenges of finding a narrative that “stitches down the ragged line between object and process,” and “lets the dust and detritus into the interpretative frame” (Desilvey Reference DeSilvey2017, 7). One of the main challenges in finding a place for this specimen is that it has lost its context. It has become a ruin. In other cases, specimens become ruins in more ways than one. Through their preservation, either as skeletal elements, or fleshed bodies that have undergone different chemical processes, bodies in collections seem immortal, as though their materiality allows them to escape the passage of time. However, as anyone dealing with them knows, their immortality is an illusion: in the absence of an infrastructure and network to care for them, dust, mold or even wall paint settle in, wet specimens deteriorate or become obscured by dirty glass jars, colors change, labels become illegible and stories are lost, which ultimately speeds these objects’ transformation into “useless” things.

When faced with such specimens, touched by a post-mortem “decay” and marked by signs of time, one feels emotions that are akin to nostalgia, loneliness, strangeness, or anachronism. Why do they elicit such responses? Why, on the other hand, are they not strong enough to keep such collections from dying?

In trying to reflect on the complicated afterlives of such dead bodies, to bring together a reflection on their materiality, but also to capture the “anachronistic” feeling associated with them, I argue, we should approach them as ruins. This captures their liminal status, the nostalgia and emotions they evoke in us, as well as their historical testimony. To quote Svetlana Boym: “Ruins make us think of the past that could have been and the future that never took place, tantalizing us with utopian dreams of escaping the irreversibility of time” (Reference Boym2011).

The strength of their effect is due to the emotive quality made manifest through their materiality, which elicits strong sensory responses: they mostly evoke mortality, trauma, but also a strange fascination with the unknown, grotesque, or hidden—a confrontation of the depths of one’s body. They unsettle us because the human body is not an object that can be collected like any other. In life, persons exist through their bodies. In death, cultural norms dictate that bodies should undergo certain rites of passage through funerary rituals. Therefore, when a body is taken out of this prescribed ritual and becomes something else—an object of scientific interest—something stirs in us. Those prescriptions are put in place to keep death and the dead away from the living.

So far, not many studies have delved into the materiality of museum specimens (with the notable exception of the research into the materiality of the dead body by Sofaer Reference Sofaer2006 and Reference Sofaer2012; Hendriksen Reference Hendriksen2015; Knoeff Reference Knoeff2015). These biospecimens are an archive in themselves; inscribed in their materiality are specific philosophical world views and scientific understandings of the value of a body. Their liminal status between death and everlasting life (preservation), between persons and artefacts, between historical archives and de-contextualized “stuff” is that which challenges us. To paraphrase archaeologists Biornar Olsen and Tora Petursdotir, poignantly write on modern ruins that “Their hybrid or uncanny state made them hard to negotiate within established cultural categories of waste and heritage, failure and progress” (Reference Olsen and Pétursdóttir2014, 6). A similar thing can be said about human remains caught in collections, that their current status of liminal objects -both artefact and human body – leaves them caught between past and present, fascination and strangeness.

As they age, collections become matter out of place and out of time (image inspired by Mavrokordopoulou Reference Mavrokordopoulou2018), and the specimens meet different fates depending on how “exotic” or unique they are to a contemporary eye, how much background information is left or how much perceived prestige they bring (see an interesting discussion on the fate of the Albinus Collection in Leiden in Huistra Reference Huistra2018). For example, collections where the dead are anonymous and have no context are more readily dismantled. Even so, in the case where institutes, museums or universities elect to keep these collections, they do so based on the idea of their being of some scientific importance. What this importance might be is not always clear, but seems to be rather more a promise for the future. As Kevin Hetherington, quoted in Biornar Olsen and Tora Petursdotir (Reference Olsen and Pétursdóttir2014, 7) rightly highlights, what elicits emotional response from modern ruins such as these is their liminality between states of being, the fact that “they are caught in a state of ‘unfinished disposal’” (Hetherington 2004).

Collections are first and foremost relations among bodies and the material setup of instruments and space, a world of materialiaties which gave them initial meaning. Thus, if we are to truly learn something from the past, I think we must ask ourselves: what is it that we want to keep: specimens, practices, or research philosophies? The answer directly influences the kinds of materials we choose to keep, and the stories we tell about them. When we moved buildings at the Rainer Institute, part of the old building was demolished, and the display cases and other materials, which were not considered of scientific relevance, were thrown away (fig. 4). A similar story is told by Eva Ahren (Reference Ahren, Alberti and Hallam2013) about the Karolinska Institute’s collection. Contemporaneity likes neat, clean, sanitized things, and these specimens do not conform to that expectation. Consequently, collections often lose their original integrity as a bounded scientific object, and their parts become entangled in new and different agendas.

Figure 4. The attic of the old building of the Francisc I. Rainer Institute of Anthropology after a final clearing. Photographer: Alexandra Ion.

Non-biological materials, like furniture, instruments, or papers, are thrown away. Organic materials are not far behind. In 2017, during the “How Collections End” workshop in Cambridge (howcollectionsend.wordpress.com), participants heard about the fate of a local blood samples collection, where some of the materials were deemed safety hazards and discarded.

What seems to get lost in most of the debates about the proper fate of human remains collections and the policies they inform is precisely the specimens themselves: at the end of the day we are puzzled by the problem of finding a place for them in the present. Thousands, even tens of thousands of such specimens are to be found in museums and collections throughout the world, mostly gathered between the eighteenth and early twentieth century. They can be found, to name but a few, in the Hunterian Museum in London, the Museum of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, or the Leiden University Medical Centre’s Anatomical Museum, in the Samuel Morton collection in the USA, or in the more recent Morbid Anatomy Museum in New York (for a list of some of these collections see highfantastical.com/skeletal-collections/). However, in recent times, the contents of these collections, or of other, smaller ones, are slowly becoming dead scientific objects: the ties between specimens are being broken, some are discarded, and/or the accompanying materials are lost.

There are three main factors which cause the decay or demise of collections and the specimens within them: (1) market logic, (2) natural events/time, or (3) a death by theory—postcolonial critique and a re-evaluation of how we view collections. In the first case, the absence of funding leads to downsizing and reorganization, lack of storage or of paid curators. What is causing the underfunding and lack of interest is that decision-makers no longer perceive such material legacies of the past as particularly valuable. In other instances, lack of funding has had indirect consequences by exposing collections to various risk factors, as was the case during the fire at Brazil’s National Museum in 2018. Among the exhibits affected were human remains, including the oldest fossil in Latin America, known as “Luiza’s skull,” which, though damaged, was mostly recovered (Rea Reference Rea2018). Collections are also lost in events that could not be foreseen, such as bombings (about the 38000 specimens lost after an air raid in 1941 at the Hunterian Museum see Hallam Reference Hallam, Hallam and Ingold2013), floods, or through neglect, when they lose their context in storage. This especially affects archaeology specimens, where the containers, usually paper bags or boxes, decay over time, so bones become mixed, and the writing on them fades away. This makes contextual attributions impossible.

The third type of demise arises from a change in the cultural perceptions of academics and researchers, who have come to think of bodies as dark and troubled legacies of past colonial practices or as dehumanized medical experiments. Such collections often have stained histories, riddled with colonialist inheritance, objectifying medical gazes or social issues. In the last two decades, a significant critical literature has arisen to engage with the material legacies of anatomy and anthropology in the past centuries, when the quest for dead bodies made them valuable commodities, sought for their value in generating knowledge about human beings (Richardson Reference Richardson2001; Fforde Reference Fforde2004; Cassman et al. Reference Cassman, Odegaard and Powell2007; Alberti Reference Alberti2011; Alberti and Hallam Reference Alberti and Hallam2013; Hallam Reference Hallam2016). Many authors have responded to the challenging material presence of the long dead by tackling issues of race, deviance, gender and colonialism, which shaped the creation of many such collections where the normal and the “deviant” coexisted (e.g., see discussions in Jenkins Reference Jenkins2011; Conklin Reference Conklin2013; Teslow Reference Teslow2014; Redman Reference Redman2016). Implicitly, they framed ethics in terms of legal duties towards these once living beings, implying concepts such as “consent,” or “the rights of the living”—a political way of framing the relationship with the past (Scarre Reference Scarre2003; Alberti et al. Reference Alberti, Drew, Bienkowski and Chapman2009). This move has had a significant impact on the management of collections.

Consequently, some collections are kept behind closed doors due to troubled histories of racism or colonialism. In these instances, the specimens are neither discarded—after all these are human remains—nor reburied, by virtue of their potential scientific and historical value, but at the same time they are not actively put on display either. Upon visiting such collections, I am always surprised when I discover historical specimens in innocuous cupboards in some laboratory’s corner, or truly modern ossuaries, skulls lined up in glass cases behind closed doors in quiet rooms, kept just as they had been a century ago.

In an attempt to atone for our disciplinary past, we devote a great deal of time to questioning the existence of more and more of such objects and displays. However, and paradoxically, what seems to become lost in these debates and policies is precisely the ways in which these bodies’ presence still captures our imagination—as any curator or visitor could confirm. As Bruno Latour writes, through its material remains, the past objects to how it is spoken of by the experts, and does so through its very presence (Reference Latour2000). A similar point is made by Tiffany Jenkins in a 2018 piece in the Guardian, where she writes:

Turning the past into a morality play, in which grandstanding politicians and academics act as saviours, can have deleterious consequences for the way we understand it. … [A]s the accusations about the sins of the past grow louder, we hear less about the objects that are at the heart of the disputes and of those people that once created and so admired them. (Jenkins Reference Jenkins2018)

She further sees this as a symptom of a crisis of cultural authority of the role of museums: scientists are seen as the villains of the story, and they see their authority replaced with a “therapy culture.”

It is not the goal of this text to delve into a critical analysis of repatriation narratives, which, among other things, have certainly brought a number of very important issues into the light. Instead, I am interested in how the very definition of what we mean by a collection in a general sense is currently undergoing a change. Repatriation discussions, alongside other trends such as the mystique of new gadgets and technologies, and even health and safety discourse, make us think of collections as composed of individual bodies, which can be divorced from other materialities. The most common result is a slow but sure fading of the past, of a material history which has no other record left behind.

At a small scale, an example that illustrates this is Flavio Haner’s (Reference Häner, Knoeff and Zwijnenberg2015) study of a skull at the Anatomy Museum at the University of Basel. After curators restored the skull, they erased the markings on the skull which had provided additional information, and in the end this restoration contributed to the skull losing its historicity. Impact on a larger scale has been made by curators who decide on the digitization of the original labels and catalogues, which in some instances are then thrown away, leaving bodies “on their own.”

Of course, not all collections have the same fate. It is also the case that curators and owners have, throughout their history, rearranged the specimens in collections, or have merged, moved and even discarded them. The critical points of this text are not meant as generalizing claims. Nevertheless, what seems to define the present times is a questioning of the legacies of historical human remains collections in general, and of anatomy collections in particular.

Epilogue: A new life for collections?

After exploring the dilemmas surrounding one single specimen, in the wider context of the fate of human remains collections in present times, the question is: what to do next? My own reflection is informed by the modern uneasiness with seeing this process of discard, forgetting and the creation of ruins. From a more general point of view, this uneasiness is prompted by what Gavin Lucas (Reference Lucas2018) rightly summarizes as a double epistemic responsibility that we have as historians, curators or scientists: one towards our object, and another towards our colleagues and other people. Both of these responsibilities, though, can sometimes clash, or be neglected. I think that now more than ever a question that has bearing on both of these dimensions is being asked, and the ways in which we choose to answer it will have important consequences for the future: why and how should we continue to keep human remains collections? The issue at hand is how to deal with human remains collections in a way that is meaningful for scientists and curators, but also for the individuals in the collections.

Karin Tybjerg makes the important point that “epistemic objects [such as these] afford particular display possibilities that draw on their potential to generate knowledge” (Reference Tybjerg2017, 270). What affordances would we like to explore, so that we might hopefully keep these collections and specimens? One of the reasons that I think these collections are important is that they prompt us to reflect beyond the comfort of our own world, to learn about the past, to be confronted by differences. Such collections store memories, and together, the documents, materials, and bodies elicit emotions which offer a window into our past scientific worlds.

While there is certainly not one single answer or solution, it is important to acknowledge that the current loss of collections is ultimately a symptom of an uncertainty in respect to the proper handling of bodies, of death and of Others. This is accompanied by certain methodological errors, in which general statements and decisions, i.e. reburial or discard, replace case by case evaluation. On the one hand, we break relations between objects and bodies, when it is the relations that bound them together which imbued them with meaning and historicity. On the other hand, beyond the narratives focused on race, types etc., we should try and recover the stories of individuals, including both the dead who provided the specimens and the scientists who collected and studied them.

It is not easy to propose a new way of dealing with collections, so that we both capture the nostalgia of these ruins and bring into view the stories of the individuals involved. But one interesting model is Orhan Pamuk’s Museum Manifesto (Reference Pamuk2012a), and its embodiment, the Museum of Innocence. Pamuk pushes for experimenting with display strategies, so that we bring into view the feelings elicited by these ruins of the past, arguing that exhibits that “make you feel and think” are better suited to exploring humanity. Others, like Sarah Davies et al. (Reference Davies, Tybjerg, Whiteley and Söderqvist2015), propose co-curation strategies that bring the laboratory and the museum together once again, and provide the contemporary audience with a space for reflection.

These human remains collections are uneasy legacies, but it is precisely this feeling that should be captured and made manifest in new ways, to recover some of the lives contained within. In the process, we could learn important lessons about where our own understanding of bodies and peoples comes from—with all that this entails. For this, we might need to go outside the history of science, into other ways of thinking. Pamuk wrote that the “loneliness” of displays that had been “uprooted from the places they used to belong to and separated from the people whose lives they were once part of…aroused in [him] a shamanic belief that objects too have spirits” (Reference Pamuk2012b, 52). I would add to this that they have a certain quality that can help us find ourselves.

Acknowledgments

I am thankful to Andrei-Dorian Soficaru for allowing me access to the face specimen from the Institute of Anthropology’s “Francisc I. Rainer” collection. I also thank my colleague Mircea Ciuhuta for his evocative photograph of the Institute’s empty building. I am grateful to Jaume Navarro for inviting me to the “Dead Scientific Objects” Workshop in Cambridge, and to the other participants who made valuable comments on the initial draft presented at the workshop. The text has benefitted greatly from suggestions on previous drafts from John Barrett, Arda Antonescu, Oana Mateescu, Miruna Vasiliţă, Adam Gutteridge, Artur Ribeiro, from two anonymous reviewers and the editor of Science in Context.

Alexandra Ion is an osteoarchaeologist and anthropologist, telling stories about old human remains and the scientists who study them. She is interested in the study of cultural practices which deal with fragmented bodies with dynamic postmortem itineraries: from Neolithic multi-stage funerary practices to the curation and exhibition of human remains in museums. Alexandra has a PhD in History at the University of Bucharest (2014), has been a Marie Skłodowska-Curie postdoctoral fellow at the University of Cambridge (2016-2018) and has been a member of national and international research projects. She published the volume ‘Regi, sfinți si anonimi. Cercetători și oseminte umane în arheologia din România’ [Kings, saints and the anonymous dead. Researchers and human remains in the archaeology from Romania] (Cetatea de Scaun, 2019).