Opera, ‘as every school boy knows’, started life in the 1590s; and we might well suppose that such a novel phenomenon would cry out for entirely new techniques of staging. But in this we would be wrong. Most of the elements which fused to create opera as a form were already present in other musical and dramatic modes in the later sixteenth century, and that was the case, too, when it came to putting the form on stage.

Precedents and Continuities

To begin with, opera’s most obvious theatrical requirement was the singer-actor. This wasn’t a species that had to be created in 1598. There were already professional singers who made movement, gesture, and facial expression important parts of their projection of the solo songs they performed: for instance, the talented anonymous Italian lady who, coming to the front of the stage during a musical episode in Alidoro, Gabriele Bombasi’s spoken tragedy of 1568, ‘altered the expression in her face and eyes, and her gestures and movements, to accord with the changes in meaning of the words she sang’.1 And among the professional actors whose usual stage-medium was speech, there were some who could act and sing simultaneously, not least those practising that thriving late sixteenth-century form, the commedia dell’arte, which, though it was mainly spoken, often included song. As it happened, versatility of this sort saved the situation when it came to the première of Ottavio Rinuccini and Claudio Monteverdi’s opera Arianna (Mantua, 1608). Some weeks before, there had been a big casting crisis through the death of the opera’s leading lady, but a noted actress from a commedia troupe, Virginia Ramponi (‘la Florinda’, 1583–1629/30), was able to step in to play and sing the heroine, and seems to have done it very well.2

The staging of choruses also grew out of pre-operatic theatrical activity. A couple of late sixteenth-century dates and places exemplify this: 1585 at Vicenza and 1589 at Florence. The ambitious production of a modern Italian translation of Sophocles’ Oedipus the King, which opened Andrea Palladio’s remarkable, still-standing Teatro Olimpico at Vicenza in 1585, was in the main spoken, but it included musical settings by Andrea Gabrieli of four of the Theban Elders’ choric odes, and these were sung and acted in character by a well-drilled chorus of fifteen. Then in 1589, six sung and staged ‘interludes’ or intermedii on the theme of harmony – musical, social, cosmic – were placed between and around the acts of Girolamo Bargagli’s spoken comedy, La Pellegrina, during the lavish celebrations of the wedding of Ferdinando de’ Medici and Christina of Lorraine at the theatre of the Medici in Florence. A versatile singing chorus played a range of parts in the six interludes: the inhabitants of a Greek island, the denizens of Hades, sundry sea-nymphs and pirates, the ‘company of heaven’, and so on. It would have been a short and simple step from that – via the singing huntsmen, cupids, zodiac-signs, and such of the highly intermedio-inflected Florentine opera of Gabriello Chiabrera and Giulio Caccini, Il Rapimento di Cefalo (1600) – to the choric fishermen and soldiers in Arianna.

As with performers, so with décor. Libretti in opera’s first decade called for stage spectacle in the form of scene-changes (e.g., from a rural landscape to the Underworld and back) and special effects (e.g., a god descending from the heavens to sort out a fraught situation); but this didn’t involve the invention of a new technology, rather the adoption of aspects of a tradition. By 1598 the Renaissance fascination with geometric perspective had for several decades been an important impulse behind the development of three-dimensional scenic arrangements in Italian court theatres, supplying apt backings for comedy (modern streets cunningly evoked), for ‘satyric’ drama (woodland glades), and for tragedy (vistas of classical city architecture, as can be seen at the Teatro Olimpico at Vicenza). Though only a few metres deep, these backings gave the illusion of much deeper space through the foreshortening of their perspectives, which looked particularly convincing when viewed from the prince’s or duke’s or cardinal’s seat at the centre of the auditorium. At first it had been a case of one setting per show, but as the sixteenth century wore on, ways were found to change the scene during the performance in full view of the audience and seemingly without the intervention of human hands (bringing the curtain down to cover a scene-change didn’t come in till centuries later).

This was first done by installing periaktoi (from the Greek, ‘periaktos’, turning on a centre): big rotatable triangular columns with elements of three different scenes painted on their three faces, placed symmetrically at the sides of the stage and complemented with a backdrop or a bigger central periaktos. By simultaneously rotating these ‘triangles’ and changing the backdrop, the whole scene would seem to change – from a town, say, to a forest, and then to a garden. The practical need to hide the backstage functionaries operating the periaktoi was one of the things that led to the installation of a ‘proscenium’ arch downstage of them (with the stage itself continuing in front of the arch as a forestage). And once you had created that kind of picture frame, you could put roped ‘flying’ devices behind it: devices developed and elaborated from those which had earlier been used for angels and other celestials in church dramas but which might now fly in a pagan god, an allegorical personage, or a consort of singers perched on a wood-and-canvas cloud. Upstage of the arch you could also install theatrical machinery that would simulate ocean waves – perhaps with mobile boats (on invisible wheels) or creatures rising through stage-traps from the deeps – or even perhaps suggest the flaming gulf of Hades itself. So the way was open, once the operatic time was ripe, for the hero of Alessandro Striggio and Monteverdi’s Favola d’Orfeo at Mantua in 1607 to journey (per a scene-change) to the Underworld, cross the River Styx in Charon’s ferry, meet the King and Queen of the Shades in their palace, return to the fields of Thrace, and finally be led up to the heavens by his vertically mobile father Apollo.

The 1589 interlude-sequence in La Pellegrina with its versatile chorus (and its many spectacular scenic effects, too) was devised and designed by the Florentine poet Giovanni de’ Bardi and scenographer Bernardo Buontalenti (Bernardo delle Girandole, c. 1531–1608). The pair went on to supervise a large part of its practical preparation and rehearsal, but the grand duke eventually put his recently appointed controller of arts and entertainments, Emilio de’ Cavalieri, above them in the hierarchy of control. On the spine of the new controller’s account-book for the show it is described as ‘la commedia diretta da Emilio de’ Cavalieri’: a nice marker of the arrival in secular theatre of a ‘director’.3 This idea of some kind of supervisor or organiser for an elaborate theatre-piece can be traced back to the religious drama of the Middle Ages and High Renaissance.

There are records of the activities of such figures in connection with some of the age’s big annual open-air Passion Plays (the versatile Renward Cysat, for instance, who was the controlling ‘regent’ of the play at Lucerne in the 1580s and 1590s); and the function moved into secular theatre not only in Medici Florence but in other north Italian cities too. At Mantua the highly professional Leone de’ Sommi Portaleone was for decades the hands-on controller of drama at the Gonzaga court and around 1565 wrote a guide to theatrical practice, his Quattro Dialoghi di Rappresentazioni Sceniche (Four Dialogues on Scenic Representation).4 Then there was Angelo Ingegneri, a man of the theatre known to be ‘capable of such things’, 5 who was put in charge of the rehearsals of the already mentioned Italian translation of Sophocles’ Oedipus (Vicenza, 1585), later publishing a little book about staging that made special reference to the Vicenzan show: Della Poesia Rappresentativa e del Modo di Rappresentare le Favole Sceniche (On Dramatic Poetry and the Ways of Performing Stage-Plays, Ferrara, 1598).6 In all, then, there would have been nothing strange or particularly novel about an expert in theatre arts in the line of Sommi, Ingegneri, and Cavalieri taking responsibility for the overall smooth running of one of the new operas in the years that followed – ‘directing’ them, that is to say. In fact, Cavalieri himself did pretty much that. A decade after his work on the Pellegrina interludes in Florence, he was central to the Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo (the quasi-operatic Roman oratorio The Play of the Soul and the Body, 1600), not only composing the music for it but being involved with its première production and writing some memoranda on the staging of ‘the present work, or others like it’, which are added to his colleague Alessandro Guidotti’s introduction to the published score.7

Court Opera: Mantua, Florence, Rome

This is not to say that in the earliest decades of opera such a director-figure was always considered necessary. True, there were people who cared deeply that up-market court and college shows (operas among them) should be done to the best of everyone’s abilities and who felt that this could only be achieved if there was a controller with a distinct job-description: a figure who might sometimes take the Latin name of choragus in Jesuit college theatricals (where Latin was the norm) or corago in Italian-speaking court circles. But there were also situations when the librettist and composer of a new opera along with the whole theatrical team – singer-actors and dancers, chorus and instrumentalists, choreographer, scene-designer and the special-effects people responsible for ‘props’, lighting and stage-machinery – were able to collaborate harmoniously without the need for a specially appointed co-ordinator or dictatorial regent.

As it happens, we have illuminating documents from the period that reflect both ways of arranging things. In Mantua in 1608 there was a new opera on the Daphne myth for which Marco da Gagliano made a fresh setting of Rinuccini’s 1598 Dafne libretto, slightly revised. It seems to have been a happily cooperative production, and one so successful that the composer included a description of how it had been staged in the preface to the score, with the recommendation that, if it were to be performed again, it might well be done in much the same way. About twenty years later an anonymous gentleman, almost certainly at the Medici court in Florence (possibly Pierfrancesco Rinuccini, son of the pioneering librettist), wrote a treatise, not published at the time, on the proper staging of operas and other court shows with a well-informed expert in overall charge. He called it (after the expert) Il Corago, o vero alcune osservazioni per metter bene in scena le composizioni drammatiche. The printed Dafne preface and the Corago manuscript complement each other nicely and give us a good view of operatic staging in the early years.8

Both writers are concerned that their principal performers should act properly while never forgetting that everything they do has to mesh with the music. It’s interesting to find in that connection that a question still asked today about operatic acting was already being asked in Il Corago: ‘whether one should cast a tolerable musician who is a perfect actor or an excellent musician with little or no talent for acting’.9 Though aware that musical connoisseurs might demur, the author feels that audiences as a whole prefer good actors who can sing tolerably, pointing out that this needn’t wholly exclude fine singers with small acting talent, since they can be given roles involving stage-machines (heavenly chariots, floating clouds, and such) which will, so to speak, do their moving for them. The competent singer-actors permitted by the corago to tread the stage-proper are recommended to follow the rules of ordinary spoken acting – at this period quite a presentational, rhetorical affair – but urged to supplement them with some precepts specific to opera. For example, they should normally stand still while singing, only moving about during instrumental ritornelli, though they might break this rule when the music is ‘specially meant to convey motion’.10 They should keep their gestures quite slow, since sung words don’t move as quickly as spoken ones. And it would be best if they didn’t gesture violently (except when playing infernal gods) – best, too, if, when singing in dialogue with other characters, they only turned half-way towards them, since turning further might render their words inaudible to the audience.

Gagliano in his 1608 Dafne preface has similar feelings about singer-actors delivering their performances clearly and visibly out to the audience and integrating the vocal with the gestural. He stresses that physical movement should correspond both to the music’s emotional contour and to its actual beat. As an example, he gives a detailed, almost step-by-step, account of how the character of Ovid in the opera’s prologue should move while delivering it. He should make his entrance ‘at the fifteenth or twentieth measure’ of the prologue,

taking care to regulate his steps to the sound of the orchestra. … Above all, his singing and gestures should be full of majesty, more or less in accordance with the loftiness of the music. He must take care that every gesture and step follow the beat of the music and singing. When the first four lines are finished, let him take a breath, walking two or three steps during the ritornello, always observing the beat.11

Gagliano also suggests groupings of characters on stage that will make the action easy to ‘read’ – solo singers, for instance, should keep several paces clear of the chorus – and recommends careful rehearsal of difficult scenes involving pairs of characters, especially the energetic dumb-show encounter at the start of Dafne between Apollo and the writhing, fire-breathing Python: ‘The fight’, he says, ‘shall be in time with the music.’12 He’s equally keen that roles requiring more subtle skills should be carefully cast and is eager to praise the young castrato Antonio Brandi, ‘a most exquisite contralto’, who brought great verbal and gestural expressiveness to the role of the opera’s messenger-figure. Indeed, he seems to have considered ‘Il Brandino’ the star of the show – an early example of the star-making that would become a permanent characteristic of opera.

Gagliano is just as concerned with the deportment of the chorus of nymphs and shepherds (about seventeen of them at the première, though the number might vary at a revival, depending on the capacity of the stage). The choristers should, he thinks, be focused, alert, and well synchronised, though they should not have the regimented look of a dance-troupe. Most of the time they should form a half-moon, backing the principal singers, visibly responding with gesture and facial expression to the prevailing emotion, kneeling at appropriate moments, rising in good order, and accompanying sung choral numbers with group movements to left, to right, and back again to upstage centre (which suggests that the dancing master in 1608 had been looking at accounts of choric movements in ancient Greek tragedy). The blend of psychological realism and courtly formality that is characteristic of seventeenth-century opera is nicely reflected in Gagliano’s view that, even when vividly ‘imitating flight and terror’, the chorus should never turn their backs impolitely on the distinguished audience.13 Il Corago’s author agrees; it’s something that a good corago would ensure, as he would that the chorus’s gestures are unanimous and their ‘processings and interlacings’ telling. (One way of guaranteeing that choristers end up in the right stage-positions after such complicated movements, he suggests, is ‘to make marks on the stage floor’ that they can steer by – much as Ingegneri fifty years before had used the coloured marbles patterned on the floor at Vicenza as markers for his Oedipus chorus).14

It’s likely that the stage for a court opera in the early seventeenth century would need to be set up especially for the event. That done – Il Corago advises at length on this – a lot of care was called for to ensure the show’s technical smooth running. For instance, both the Dafne preface and Il Corago are at pains to secure optimum placing for the instrumentalists. The convention that would later be established of a band settled permanently in an orchestra-pit just in front of the stage didn’t apply at the time. Instruments and their players, largely hidden, could be located before or behind or above the action as seemed best for any particular situation – Monteverdi went to some lengths to get this matter right when he made a professional visit to Parma in 1627.15 Il Corago, in a chapter on the rival claims of strings and winds to be the best support for sung drama, stresses that careful placing of either group is essential to achieving good vocal–instrumental balance and ensuring that there are clear lines of communication between players and singers during the performance. (For instance, putting an organo di legno in the wrong place in the wings would not only risk impeding the periaktoi and the work of the stage-machinists but might also mean that the organist, having ‘the inconvenience of not being able to see or hear the actors well, would be constrained to adopt a [regular] beat [sarà forza cantar a battuta], which is something considered improper for the recitative style’.16 Gagliano is keen on this too, and he’s eager to explain a related special effect when his Apollo seems to be playing his lyre exquisitely during his lines in praise of the metamorphosed Daphne, though the sound is actually coming from a consort of viols placed just out of sight behind the scenery.

Rather surprisingly, Gagliano doesn’t feel called on to praise the designer of that scenery, but maybe this is because the opera was done against a single pastoral set which had already been used for earlier shows. Il Corago, on the other hand, is full of praise for one scenographer, Bernardo Buontalenti, he of the Pellegrina interludes back in 1589. Though dead for about twenty years by 1630, the treatise reveres him as the father-figure of the whole fashion for changeable perspective-scenes, stressing that proper management of such scenery is one of the two most important responsibilities of a corago (the other being instruction in acting). It discusses the means of maximising illusion in scene-painting and scene-changing, along with effective techniques of illumination with candles and oil lamps, the provision of apt but rich costumes for the cast (peasant roles included: this is court opera after all), and the use of a stage curtain at the very beginning and end of the show. Machines that fly singer-actors down from above are another special concern: their safety (check it regularly), their smooth operation (soap the ropes and pulleys frequently), and the speed of their descents and ascents (keep these slow when a performer is actually singing on one of them).

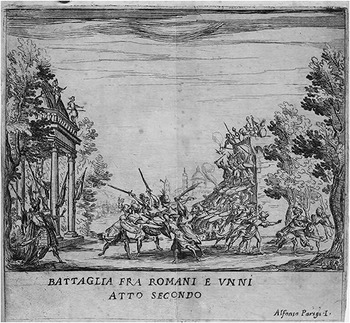

Records from other north Italian princely courts and from the establishments of equally princely cardinals in Rome reveal similar activities and concerns.17 We learn that staging an opera was something that consumed time and ingenuity, though the preparation time could vary widely: about five months were set aside for rehearsals of the Mantuan Arianna after the singers had learned their parts, but a mere forty-four days covered the writing, composing, preparing, and rehearsing of a ‘favola in musica’, the Roman Aretusa (Ottavio Corsini and Filippo Vitali) in 1620. Records of that Aretusa and of Monteverdi’s Orfeo give us glimpses of the care that was taken to recruit properly talented singer-actors and of the appreciation that such people received if they came up to expectation. And away from the soloists and chorus, we see groups of anonymous ‘extras’, the non-singing comparse, being put through their paces effectively. The conflict between the Romans and the Huns in La Regina Sant'Orsola (Andrea Salvadori, Gagliano; Florence, 1624) is an instance. The engraving in Figure 9.1, made for the libretto of the 1625 revival by Alfonso Parigi (son of the show’s designer), shows the battle, staged by the dancing master Agniolo Ricci, raging beneath the walls of Cologne: the Temple of Mars to the left, the Romans defending the city walls to the right. Equally elaborate crowd-work is evident in the remarkable scene of a country fair, the ‘Fiera di Farfa’, designed by one of the greatest artists of the Roman Baroque, the sculptor and architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and staged in Rome as an interlude for the 1639 version of the opera L’Egisto, ovvero, Chi soffre speri (Giulio Rospigliosi, Virgilio Mazzocchi, and Marco Marazzoli; first performance 1637). This featured street-cries, popular songs, dancing, duelling, and a bevy of comparse energetically enjoying all the fun of the fair – the whole rounded off with an impressive sunset.18

The backstage wizards who devised scenic devices in connection with such spectacles could be singled out for praise: for instance, the architect Francesco Guitti (1605–c. 1645), who worked in Ferrara, Parma, and Rome, and whose ‘excellence in inventing, setting up and controlling machines and theatrical effects’, a contemporary said, ‘was attested by universal amazement and applause’.19 Sometimes even the composer was amazed at what his backstage colleagues had done, as at the Roman staging of Rospigliosi and Stefano Landi's Sant’Alessio in the 1630s. (Figure 9.2 represents the final scene of the 1634 version: a ‘tragic street’, possibly designed by Pietro da Cortona, with Religion singing Saint Alexis’ praises as the Virtues dance and a host of heavenly musicians descends on two cloud-machines). ‘What shall I say’, Landi enthused,

of the scenic apparatus? The first appearance of the new Rome, the flight of the angel through the clouds [and] the appearance in the sky of [the Spirit of] Religion were all works of ingenuity and machines, but they rivalled nature herself. The scene was most cunningly wrought: the visions of Heaven and Hell were marvellous; the changes of the wings and the perspective were ever more beautiful.20

Things went best when the stage-hands were properly trained; thus Nicola Sabbattini in his Pratica di Fabricar Scene e Machine ne’ Teatri of 1638 says that the scene-shifters should be ‘familiar with sound and time cues, so that during the playing of the music, they cause the [scenic] frames to be run to their positions all at one time’.21

Figure 9.2 Giulio Rospigliosi and Stefano Landi, Il Sant’Alessio (Rome, 1631), final scene of the 1634 version. Engraving by François Collignon, from Il S. Alessio: dramma musicale: dall eminentissimo, et reverendissimo signore card. Barberino (Rome: Paolo Masotti, 1634).

As several of these instances have shown, some of the liveliest operatic action in the middle decades of the century took place in Counter-Reformation Rome. Interest in staging there was apparent in the highest circles, both of the Church and of the community of talented artists who served it, especially if they were in the sphere of the powerful Barberini family. The prime instance of ecclesiastical involvement was the copious librettist Rospigliosi, who would be elevated to the Chair of St. Peter as Pope Clement IX in 1667, but he seems earlier to have been very closely involved with the staging of his sophisticated yet highly moral operas.

Extensive records survive of the circumstances of their productions at the Palazzo Barberini, the most revealing perhaps being the marginalia in one manuscript of Dal Male il Bene, the libretto he had written with his nephew Giacomo in 1654. The notes indicate scenic locations, itemise props (right down to a couple of candle-holders and a broom), cue scene-changes, refer to sound-effects, and make clear which of the numbered routes for getting on and off the stage the performers should use for particular entrances and exits.22 If that document embodies the minute concerns with staging of a highly placed librettist, an entry in the diary of the English traveller John Evelyn for 19 November 1644 illustrates the breadth of the operatic interests of the great Bernini:

a little before my Comming to the Citty, [he] gave a Publique Opera (for so they call those Shews of that kind) where in he painted the Seanes, cut the Statues, invented the Engines, composed the Musique, writ the Comedy & built the Theater all himselfe.23

Add to that the information from Filippo Baldinucci’s life of Bernini that at the rehearsals of his theatre pieces, he ‘would himself take all the parts to teach the others how to play them’, and you have an omnicompetent centraliser of opera who out-Wagners Wagner at the Bayreuth of the 1870s.24

Public Opera: Venice, Paris, London, Naples

Such stories of Bernini in Rome may have improved a little in the telling, but we can take Evelyn’s account of the operatic Venice of the 1640s at face value, as he was there to see things for himself. He was witnessing the momentous innovation of opera given not at court as part of the munificence and magnificence of a prince but as a commercial proposition open to all – all anyway who could afford the price of admission. Court opera, of course, didn’t come to an end, and among the vivid accounts of its staging in the decades after the 1640s there are several which stress the numbers of comparse in stately retinues, energetic armies, and the like that rich courts could display, and the grandiose sets that they could display them in. The shop-window example was Il Pomo d’oro of Francesco Sbarra and Antonio Cesti, given at the Viennese court in 1668 on the empress’s birthday, with its fifty named characters, its twenty-three sumptuous sets by the architect Ludovico Burnacini, and an action which found room for a fiery flying dragon, a collapsing temple, a pair of elephants drafted into siege-work, and more besides.

The focus, however, was now on public opera, and Evelyn had an eye for its practicalities when he saw the Ercole in Lidia of Maiolino Bisaccioni and Giovanni Rovetta in Venice at the Teatro Novissimo in Ascension Week 1645 (the year of its première):

That night … we went to the Opera, which are comedies and other plays represented in Recitative Music by the most excellent Musitians vocal & Instrumental, together with variety of Sceanes painted & contrived with no lesse art of Perspective, and Machines, for flying in the aire, & other wonderfull motions. So taken together it is doubtlesse one of the most magnificent & expensefull diversions the Wit of Man can invent: The historie was Hercules in Lydia, the Seanes chang’d 13 times. [Among] the famous Voices [was] Anna Rencia, a Roman, & reputed the best treble of Women; but there was an Eunuch, that in my opinion surpass’d her, also a Genoveze that sang an incomparable Base.25

Although several aspects of Venetian staging were seamless continuations of Roman and north Italian courtly practice, Evelyn here points up three things which were different and which would in time become important over the whole of operatic Europe. The first is the (to us) simple concept of ‘going to the opera’, which implies a choice of performances to see – ‘comedies and other plays represented in recitative music’ – and, if we are lucky, a choice of opera houses to see them in. In the first five years of public opera, four such houses came into existence in Venice, the city having invented the purpose-designed (or at least purpose-adapted) public building devoted to the staging of operatic performances under the management of an impresario who had to think carefully about investments and returns when providing these ‘expensefull diversions’ for a paying audience.

Establishing an influential precedent, the auditoria of these Venetian houses tended to be U-shaped, centring on a crowded ‘pit’ for in-the-main male spectators (who might stand for the whole show or perhaps pay to sit on benches), surrounded on three sides by balconies or galleries generally divided into ‘boxes’: an arrangement deriving from earlier Venetian theatres for the commedia dell’arte. Renting a box – sometimes even buying one – implied social stature, though the view from it of the scene-stage behind the proscenium arch could be so bad that a production might sometimes have to be modified out of consideration for such box-holding gentlefolk as wanted to watch the action. Thus Aurelio Aureli reports an emendation to his 1659 libretto for La Costanza di Rosmonda (music by Giovanni Battista Volpe [Rovettino, c. 1620–1691]) which meant that one singer-actress’s delivery of an important monologue would be moved from its rightful place (on a balcony that was part of the scenery) to the stage floor, ‘in order to make her visible to the eyes of everyone, especially those seated in the boxes’.26

Evelyn’s counting the thirteen changes of scene in Ercole in Lidia is a second revealing point. Though it seems that in some places the older triangular periaktoi-method of scenic display and transformation was still in use in the mid-seventeenth century, from the 1610s and 1620s onwards it was being widely replaced – partly under the influence of the architect and designer Giovanni Battista Aleotti – by the new-fangled ‘wing-flats’ (with matching ‘borders’ above): sets of two-dimensional, perspective-painted and profiled units which were set up in grooves to the right and left of the stage behind the proscenium arch so as to complement and frame a backdrop. These were capable of being drawn back – and the backdrop raised – to reveal another set immediately behind them, thereby changing the scene in a few seconds from, say, a meadow to a city street. In the early years, simultaneously drawing back such a set of perhaps eight flats – four each side – was decidedly labour-intensive; but the scenographer and machinist Giacomo Torelli (1608–1678), active in Venice in the late 1630s and early 1640s before moving influentially to Paris, hit on a system related to naval rope-work whereby all the flats in a set were attached to a single counter-weighted capstan-drum beneath the stage, which could be operated by one man. ‘The artifice of this device is amazing’, a contemporary wrote; ‘a fifteen-year-old boy can work it by himself!’27

Torelli was closely connected with the Teatro Novissimo that Evelyn visited, and he may well have had a hand in designing the numerous easily changed scenes the diarist saw in Ercole. Henceforward for many decades, no self-respecting Continental opera house would be without a scene-changing system somewhat in the Torelli style and a collection of Torellian perspective-scenes that could be used for a wide range of shows: a city street or two perhaps, some rooms of state, a dungeon, a temple, an army camp, a cave, a seashore, a wilderness, an arbour, or a grove. Figure 9.3, for instance, shows a design by Torelli for Niccolò Bartolini and Francesco Sacrati’s Venere gelosa (Venice, Teatro Novissimo, 1643): a woodland scene on the island of Naxos (tree-flats with city backdrop) with the goddess Flora appearing in a machine above, supported by Zephyrs.

Figure 9.3 Niccolò Bartolini and Francesco Sacrati, Venere gelosa (Venice, 1643). Anonymous engraving from a libretto published in 1644 to accompany a revival of the opera.

Within and in front of these scenes, lit by candles and oil-lamps, which also lit the auditorium during the performance, were the singer-actors – which brings us to the third significant element in Evelyn’s account of the Novissimo: his concern to rank-order the voices he heard in Rovetta’s opera and his noting the star-status of Anna Renzi (c. 1620–d. after 1661). Singer-actors, as much as or more than libretto, music, or décor, were becoming a principal operatic talking point in Venice, and la Renzi could be rated as the first big star of public opera. Indeed, in 1644, the year before Evelyn’s visit, she had been the subject of the first operatic fan-book, the librettist Giulio Strozzi’s Glorie della Signora Anna Renzi Romana. Strozzi celebrates his heroine’s compound of intellect, imagination, and memory; her versatility; her powers of character-observation; her ability to ‘transform herself completely into the person she represents’ – and her voice.28 Voices were at a premium. A French visitor to Venice in the 1670s, Alexandre-Toussaint Limojon de Saint-Didier, describes the gentlemen who ‘bend themselves out of their Boxes, crying Ah cara! […] expressing after this manner the Raptures of Pleasure which those divine Voices cause to them’, along with the gondoliers in the pit whose earthier acclamations ‘are not always within the bounds of Modesty’.29

The surviving documentation of the financing and management of operatic houses and companies in seventeenth-century Venice is considerable, but very little of it has to do with staging in the sense of training and rehearsing particular casts or making decisions about particular décors. This may be in part because a figure like the courtly corago could have no place in the busy commercial environment of the new impresarios; in part because opera singers and backstage technicians were becoming more experienced, so needing less and less documented instruction; and in part because the librettists were themselves quite often impresarios – there are several known instances in mid-century Venice – and so could include a director-like function as part of their daily work in the theatre without there being any call to put that fact on record. Giovanni Faustini, for instance, the author of eleven libretti for Francesco Cavalli, was at one time or another impresario at three different Venetian houses.30 Even a librettist with no impresa or other opera house job might include in his word-book so many details of moves, asides, and emotional states, along with details of scenery, props, and machine-effects, that almost all the staging-information needed for the rehearsal of his opera was there in the printed text, and the cast and crew needed no further guidance. Thus Matteo Noris’s (d. 1714) libretto for Totila, his fate-of-the-Roman-Empire piece staged in Venice in 1677 to a score by Giovanni Legrenzi, has stage-directions (called in Italian ‘didascalie’) galore, covering movement (‘Attempting to leave, Desbo is waylaid by Publicola’ [Act III scene 15]), mental states (‘Longing to kiss Marcia’ [Act II scene 16]), and scenic spectacle (‘A storm breaks out’ [Act II scene 8]; ‘Slaves drag from a distance a huge gold-covered elephant’ [Act I scene 17]).

Across the Alps to the northwest, however, a powerful director – a near-dictator indeed – was alive and well and working in Paris, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, and Versailles: Jean Baptiste Lully (1632–1687). When French opera truly got under way in the early 1670s with his Cadmus et Hermione and Alceste, it was formed by combining things imported from Italy (continuous music, a narrative conducted entirely in song) with something that had been characteristically north-European for generations: an enthusiasm for dramatic dance, fanciful costumes, and spectacular sets in allegorically themed court entertainments. In the earlier years of the century, the French manifestation of this enthusiasm, the ballet de cour, had had a tradition of determined directors: sometimes the aristocratic devisers of the ballets themselves and sometimes their subaltern maîtres de l’ordre – gentlemen who worked closely with dancing masters, costume and mask designers, and latterly set designers to produce a successful show. Regarding such a maître’s responsibilities – involving not only such preparatory matters but also stage-managing ‘on the night’ as well – there is a lively chapter in a little treatise of 1641 by one M. de Saint Hubert, La Manière de Composer et Faire Réussir les Ballets. Ballets ‘mastered’ in that way may have flowed the more easily into the early development of operatic tragédie en musique because the new form’s creative organiser had been born Giovanni Battista Lulli in Florence in 1632: almost certainly the place, and very close to the time, of our treatise on the idea of a corago.

Along with his Florentine background and his contracting into the ballet de cour tradition, Lully had a third reason for taking a dictatorial approach to the staging of his works: the direct responsibility he had from 1672 onward to the absolutist grand monarque Louis XIV for making a success of a uniquely French style of opera. (Figure 9.4, an engraving by Jean Le Pautre, shows an open-air, scenery-less performance of Philippe Quinault and Lully’s Alceste as staged on 4 July 1674 at Versailles before the king some months after the opera’s indoor première in Paris. Having defied the Fury Alecto, the hero Hercules, right of the central group, is claiming Alceste from the King and Queen of the Underworld, who stand on either side of her). Things went on the more swimmingly for Lully because he was working at a time when the procedures and achievements of French spoken and danced theatre were of a remarkably high standard, and when gifted theatre-artists – librettists like Quinault (bap. 1635–1688), designers like Jean Berain (1640–1711), choreographers like Pierre Beauchamps (1631–1705) – were available for co-option or conscription. Further, before he began his operatic career, Lully had collaborated on comédie-ballets with the great playwright, actor, and company manager Molière (Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, bap. 1622–1673), perhaps studying the method of rehearsal by instruction, demonstration, and energetic, sharp-tongued good humour that Molière sketches in his rehearsal-play of 1663, L’Impromptu de Versailles. Beyond that he could recommend to his leading ladies that they study the art of the heroines in Jean Racine’s newly written spoken tragedies. With all this in the background, Lully was able to be a highly effective autocrat. In 1705, eighteen years after his death, his admirer the critic Jean Laurent Le Cerf de la Viéville recalled that the brilliant Florentine had ‘an extraordinary talent for everything connected with things theatrical’. Lully, he said, knew as well how to have an opera performed and how to govern

its performers as he did how to compose one. From the moment a singer, male or female, fell into his hands, he applied himself to their training with marvellous affection. He himself taught them to make an entrance, to walk on stage, to achieve grace in gesture and movement. … Eventually the rehearsals came. To these he only admitted essential people (the librettist, the machinist etc.), [so] he had the liberty to instruct and correct his actors and actresses. … When he needed to, he would set about dancing before his dancers so that they could the better understand his ideas.31

Across the English Channel, there’s a finely farcical demonstration of how such shows of omnicompetence do not work if the would-be autocrat has neither the personality nor the skills to bring them off. It’s in the Duke of Buckingham’s burlesque comedy The Rehearsal, staged in London in 1671 around the time of the first stirrings of what would become the characteristically English form of ‘semi-opera’. Buckingham’s Mr Bayes – probably a satiric amalgam of the poet-dramatists William Davenant and John Dryden – is a thoroughgoing coxcomb who has written a grotesque hybrid of a ‘heroic’ play which features songs (including a ‘battel in Recitativo’), much scenic spectacle, and dances to music of his own composition ‘apted for the business’. But the poor performers can’t understand it in rehearsal; Mr Bayes’ attempts at explanation only make matters worse; his music resists being danced to (‘Sir, ’tis impossible to do any thing in time, to this Tune’); and when he tries practical demonstration, he ‘puts ’em out with teaching ’em’, at one point tripping and falling flat on his face when attempting to show off a particular move (‘Ah, gadsookers, I have broke my Nose’).

But more accomplished stagings could be expected in England when towards the end of the century the actor–manager Thomas Betterton was in charge of the fairly rare manifestations of public opera in London.32 They were mainly works in the ‘semi-operatic’ mode that combined spoken dialogue with very extensive and picturesque masque-like sung and danced passages, music often by Henry Purcell (1658 or 1659–1695) and choreography by Josias Priest (c. 1645–bur. 3 January, 1735). Where their special scenic effects are concerned, these formed something of a summa of the Baroque tradition. Thus one can see the surfacing from the stage-ocean of Britannia’s island in the last act of King Arthur (Dryden and Purcell; London, 1691) as reflecting the surfacing of the pearl-rich island of beautiful princesses in the first intermède of Molière’s Les Amants magnifiques of 1670 (its music by Lully) and that of the American coral reef in the Amerigo Vespucci interlude of the Florentine multi-media show Il Giudizio di Paride of 160833 – which itself derives technically from the thrusting-up of the Mountain of the Wood Nymphs in the second intermedio of La Pellegrina in 1589. And the scene of the sun rising after the mistakes of the night in the Shakespeare-Betterton-Purcell Fairy Queen (London, 1692) – Purcell writes a big orchestral ‘sonata’ for it – recalls the sunset Bernini had devised for the ‘Fieri di Farfa’ in Chi Soffre Speri at Rome in 1639, which itself could be traced back to the radiant dawn that had come up at the beginning of La Pellegrina’s final intermedio fifty years before.

Late in the same decade as King Arthur and The Fairy Queen, but a thousand miles away in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, the Naples-based Andrea Perrucci wrote his Dell’Arte Rappresentativa (1699), stressing the desirability of someone who will take care and pains to monitor the preparation and performance of spoken-scripted plays and commedia dell’arte improvisations, and of operas as well. This corago – Perrucci reverts to the word – will act as construction-supervisor, troubleshooter, props master, stage manager, and general cast co-ordinator: a central figure who ‘guides, plans and trains, for […] in this sort of business it is better to go for a monarchy than a republic’.34 And it is doubtless this corago who will insist on Perrucci’s behalf that the singer-actors in his operas should act just as well as speaking actors do and who will ensure that there are no occasions for confusion among – let alone collisions between – performers over entrances and exits. His recommendation for avoiding such things is the posting of a list behind the proscenium arch detailing who comes on, who goes off, and when they do it at entrances numbered 1–6 or lettered A–F, though for opera he also suggests another way of ensuring good stage-traffic, one clearly in line with growing practice in opera seria where the ‘exit aria’ was concerned: a matter of entering the scene as far upstage and exiting as far downstage as possible.35

Meanwhile, opera in Paris and at Louis XIV’s court was coping with the aftermath of Lully’s death in 1687. His royally authorised monopolies over tragédie en musique and the long shadow they threw forward helped to ensure that the staging of French opera, like its composition, stayed broadly Lullian for years to come. Significantly, when the structure, management, and running of his Académie Royale de Musique at the Palais-Royal theatre were overhauled and rationalised by two royal ordinances in 1713 and 1714,36 the company was required to keep a production of a Lully opera permanently ‘in readiness’ in case it was needed, and also to appoint two Syndics responsible to the company’s court-connected Inspector General. One of these was ‘the official responsible for theatrical control’ (le syndic chargé de la régie du théâtre). He was to see to artistic planning and casting (along with the composer, if contactable) and to oversee all rehearsals and performances, during which everyone connected to the production – front-of-house, onstage, and back-stage – was answerable to him.

Lully’s ghost would have been pleased, as it would have been by the continuing didactic influence of the singer-actors he had trained, the fiery-eyed Marie Le Rochois (c. 1658–1728) especially, who had created the role of the lovelorn sorceress in his Armide and held audiences breathless with it. However high the style of her performances, there was clearly a level of close psychological identification involved in their preparation. The story is told of her instructing a younger singer in the correct approach to role-play in lyric tragedies like Armide and asking her at one point what she would do if, like the character she was playing, she were abandoned by the man she passionately adored. ‘Get another one’, said the pupil. ‘In that case, mademoiselle, we are both wasting our time’, said Le Rochois and ended the lesson abruptly.37 It was an involvement with the role in hand which would doubtless have appealed to Renzi, creator of Ottavia in L’Incoronazione di Poppea (Giovanni Francesco Busenello, Claudio Monteverdi; Venice, 1643), and to Ramponi, whose performance as the despairing Ariadne at Mantua in 1608 had, in Marco da Gagliano’s words, ‘visibly moved the whole theatre to tears’.