1. Introduction

Episodic memory allows us to remember objects and people that we have encountered as well as details about events that we have personally experienced. It gives us awareness of our past experience, it is crucial to a smooth functioning in our daily life, and it permits that we mentally project what might subsequently happen on the basis of our past memories (Tulving Reference Tulving, Nilsson and Markowitsch1999). Unfortunately, episodic memory is fragile and can be disrupted by certain conditions. Some people experience memory impairments (amnesia) suddenly after an acute brain damage. Others experience a progressive memory decline because of a neurodegenerative pathology such as Alzheimer's disease (AD).

The understanding of episodic memory mechanisms and how they are implemented in the brain has progressed extensively thanks to research in neuropsychology and neuroimaging. Current theories posit that episodic memories can be retrieved via two processes: recollection, which designates the recall of the specific details from the initial experience of the events, including details about the spatiotemporal context, and familiarity, which refers to knowing that one has experienced something in the past without recalling details about the encoding episode (Mandler Reference Mandler1980; Tulving Reference Tulving1985; Yonelinas Reference Yonelinas1994).

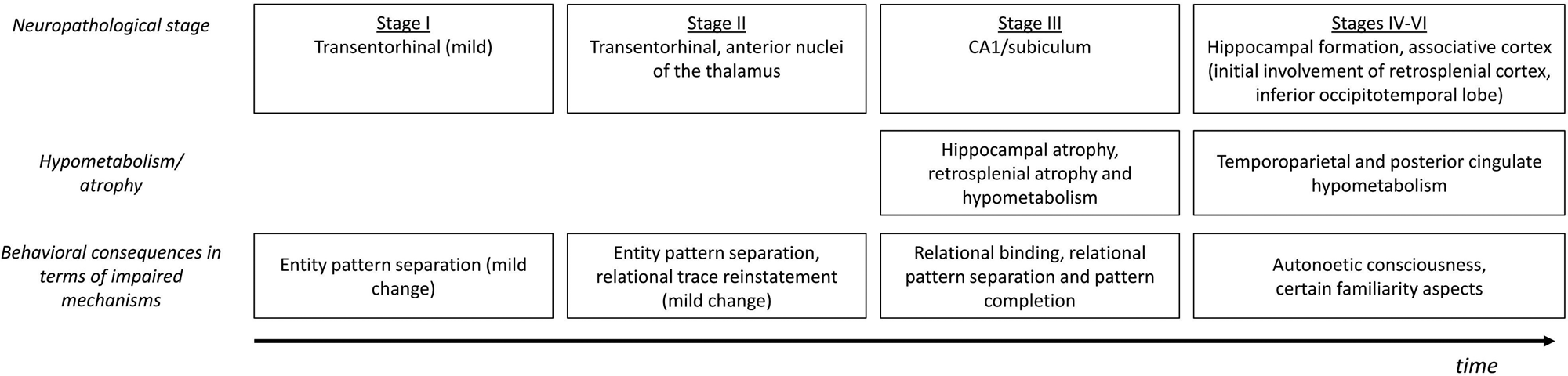

In the following sections of this target article, we first define the processes of recollection and familiarity in psychological terms (sect. 2). Then, we summarize the current most influential frameworks that describe their neural substrates. The existing frameworks differ by their focus on cognitive operations versus type of representations, by the emphasis on a specific brain region versus neural systems, and by the assumption that recollection and familiarity processes are either localized to a brain region or not localized (section 2). Next, we consider how a more complete understanding of recollection and familiarity would benefit from combining different accounts into a unified framework that bridges several cognitive and neural mechanisms (sect. 3). Therefore, we propose an integration of principles, currently pertaining to separate theories, in a neurocognitive architecture of interacting operations and representations within large-scale cerebral networks that allow familiarity and recollection (sects. 4 and 5). Such an integrative perspective allows us to generate new hypotheses about the nature of memory deficits in brain-lesioned populations and neurodegenerative diseases. Section 6 thus presents predictions about recollection and familiarity deficits in memory-impaired populations, with a detailed illustration on AD.

2. Recollection and familiarity

In psychological terms, recollection is defined as a retrieval process whereby individuals recall detailed qualitative information about studied events (Montaldi & Mayes Reference Montaldi and Mayes2010; Yonelinas et al. Reference Yonelinas, Aly, Wang and Koen2010). Some authors consider that there is recollection as soon as one retrieves at least one detail that is not currently perceived, inducing moderate to high confidence that the event actually occurred (Higham & Vokey Reference Higham and Vokey2004; Yonelinas et al. Reference Yonelinas, Aly, Wang and Koen2010), but the amount of details may vary from one trial to the other (Higham & Vokey Reference Higham and Vokey2004; Parks & Yonelinas Reference Parks and Yonelinas2007; Wixted & Mickes Reference Wixted and Mickes2010). These associated details typically represent the context in which an event took place (i.e., place, time, environmental or internal details) (Ranganath Reference Ranganath2010). Recollection can be accompanied by a subjective experience of mentally reliving the prior experience with the event, as if one were mentally traveling back in time to re-experience it (Tulving Reference Tulving1985).

In contrast, familiarity is a feeling of oldness indicating that something has been previously experienced. It is thought to support predominantly recognition of single pieces of information (i.e., items such as objects and people; Ranganath Reference Ranganath2010), but associations between similar types of information could also be recognized as familiar (Mayes et al. Reference Mayes, Montaldi and Migo2007). Subjectively, feelings of familiarity are more or less strong feelings that one knows that something has already been encountered, leading to varying degrees of confidence (Tulving Reference Tulving1985; Yonelinas et al. Reference Yonelinas, Aly, Wang and Koen2010). According to some theories, the feeling of familiarity arises when one interprets enhanced processing fluency of a stimulus as a sign that it was previously encountered (Jacoby et al. Reference Jacoby, Kelley, Dywan, Roediger and Craik1989; Whittlesea et al. Reference Whittlesea, Jacoby and Girard1990). Fluency is typically defined as the speed and ease with which a stimulus is processed and may arise from many sources (e.g., mere repetition, perceptual clarity, rhyme, predictive context, oral-motor sequence), including past occurrences (Oppenheimer Reference Oppenheimer2008; Reber et al. Reference Reber, Schwarz and Winkielman2004a; Topolinski Reference Topolinski2012; Unkelbach & Greifeneder Reference Unkelbach and Greifeneder2013). Because people intuitively know from their earliest years that fluently processed items are more likely to have been encountered previously, a feeling of fluency during a memory task will be likely interpreted as related to prior exposure (Schwarz Reference Schwarz2004). However, several conditions have to be fulfilled for fluency to be used to guide memory. First, fluency has to be judged as a diagnostic cue for memory (Westerman et al. Reference Westerman, Lloyd and Miller2002). Second, the experienced fluency has to be greater than expected in a given context (i.e., individuals have to be surprised by the ease with which they are able to process an item) and should not be attributed to a more plausible source (e.g., the intrinsic perceptual quality of the stimulus) than past occurrence. Thus, if people appraise past encounter as an improbable source of fluency or if a more plausible source is detected, individuals will disregard fluency as a relevant cue for recognition decisions (Kelley & Rhodes Reference Kelley, Rhodes and Ross2002; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Lloyd and Westerman2008; Willems & Van der Linden Reference Willems and Van der Linden2006). This disqualification will prevent fluency to give rise to a feeling of familiarity.

2.1. Existing models of recollection and familiarity

Neuropsychological investigation of recollection and familiarity in memory-impaired populations (e.g., those with normal aging, amnesia, epilepsy, neurodegenerative diseases) as well as neuroimaging studies examining the neural correlates of recall and recognition memory tasks (using mainly functional magnetic resonance imaging [fMRI]) have provided a huge corpus of data that have led to the development of neurocognitive models of episodic memory functioning. Most memory models focus on the role of the medial temporal lobe (MTL) in recollection and familiarity, since seminal neuropsychological work has shown that amnesia arises following MTL damage (Scoville & Milner Reference Scoville and Milner1957). Much controversy still surrounds the precise contributions of the different MTL subregions, most notably the hippocampus and the adjacent perirhinal and entorhinal cortices. With the exception of unitary models suggesting that MTL structures contribute to both recollection and familiarity as a function of memory strength (Squire et al. Reference Squire, Wixted and Clark2007; Wixted & Squire Reference Wixted and Squire2011), the majority of models suggest that there is fractionation of memory processes in the MTL by reference to recollection and familiarity. These MTL models can be distinguished as a function of whether they define the role of the hippocampus and adjacent MTL cortices in terms of putative cognitive operations or according to the nature of representations. Most frameworks target the role of anatomical regions (and their functional network), but a few speak at the scale of individual neurons or populations of neurons within a brain region.

2.1.1. MTL process models

These models propose that the different MTL regions have distinct computational properties (Montaldi & Mayes Reference Montaldi and Mayes2010; Norman & O'Reilly Reference Norman and O'Reilly2003). In particular, only the hippocampus is capable of pattern separation (to create distinct memory representations for similar inputs) and pattern completion (once the hippocampus has bound the elements of an episode into a memory trace, subsequent experience of a subset of the elements causes the remaining elements to be reactivated by association). Thanks to these properties, the hippocampus is specialized for recollection of details. In contrast, the perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices extract statistical regularities in repeated inputs by creating sharper patterns. By contrast with novel inputs that activate weakly a large pattern of units, the sharpness of MTL cortical patterns indexes familiarity (Norman & O'Reilly Reference Norman and O'Reilly2003). The perirhinal cortex would thus encode similarities between events (LaRocque et al. Reference LaRocque, Smith, Carr, Witthoft, Grill-Spector and Wagner2013) and support familiarity. At the scale of neurons, some models describe familiarity signals as resulting from decreased firing of perirhinal neurons for repeated stimuli (Bogacz & Brown Reference Bogacz and Brown2003; Bogacz et al. Reference Bogacz, Brown and Giraud-Carrier2001; Sohal & Hasselmo Reference Sohal and Hasselmo2000). This would arise because the number of active neurons that responded to a novel stimulus reduces as the stimulus becomes familiar.

2.1.2. MTL representational models

These models emphasize the different kinds of information incorporated in representations formed in the hippocampus versus the parahippocampal region (Aggleton & Brown Reference Aggleton and Brown1999; Davachi Reference Davachi2006; Eichenbaum et al. Reference Eichenbaum, Yonelinas and Ranganath2007; Ranganath Reference Ranganath2010). Whereas the perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices encode specific constituent elements of an event (e.g., objects, spatial layout), the hippocampus encodes representations of the relationships between the elements. According to the binding of item and context model (Diana et al. Reference Diana, Yonelinas and Ranganath2007; Ranganath Reference Ranganath2010), the perirhinal cortex and parahippocampal cortex encode, respectively, item and context information, and the hippocampus encodes representations of item-context associations. Retrieval of item representations in the perirhinal cortex can support familiarity, while context representations and item-context bindings support recollection. As in MTL process models, the hippocampus is important for recollection, but these views consider that the parahippocampal cortex is also important for recollection because it represents contextual information.

2.1.3. The representational-hierarchical models

Recently, there has been accumulating evidence that the MTL mediates processes beyond long-term episodic memory. It is also involved in perception and short-term memory. In this view, the role of the MTL would be best described in terms of how each region represents information rather than in terms of a specific process (Cowell et al. Reference Cowell, Bussey and Saksida2006; Graham et al. Reference Graham, Barense and Lee2010; Saksida & Bussey Reference Saksida and Bussey2010). Actually, the MTL is considered an extension of the representational hierarchy of object processing within the ventral visual stream. The complexity of representations increases from posterior occipital areas to the anterior lateral and medial temporal regions. The perirhinal cortex represents the culmination of this object processing pathway, performing the most complex feature computations required to discriminate objects with a high degree of visual feature overlap. In a memory task, the perirhinal cortex can differentiate between objects that share features. Most recent suggestions also posit that the capacity of the perirhinal cortex to distinguish between overlapping item representations makes it a critical region to disambiguate conceptual entities with shared properties, such as living objects (Clarke & Tyler Reference Clarke and Tyler2015; Inhoff & Ranganath Reference Inhoff and Ranganath2015), in various tasks such as naming or recognition memory. As for the hippocampus, its function goes beyond object processing, as it represents relational configurations and scenes that can support performance in a variety of tasks, such as perceptual discrimination of scenes, navigation, imagination, source memory, and so forth (Clark & Maguire Reference Clark and Maguire2016; Cowell et al. Reference Cowell, Bussey and Saksida2010). So, this theoretical approach does not map recollection and familiarity onto specific regions. The role of MTL subregions are rather defined in terms of the type and complexity of representations they contain and all could generate familiarity and recollection (Cowell et al. Reference Cowell, Bussey and Saksida2010).

In all these models, the role of another region of the MTL, the entorhinal cortex, is poorly specified. The entorhinal cortex receives the inputs and outputs of other MTL regions, but its anterolateral and posteromedial parts appear to belong to different systems. Indeed, it has been suggested that the anterolateral entorhinal cortex may have functional specialization similar to the perirhinal cortex, whereas the posteromedial entorhinal cortex would support the same function as the parahippocampal cortex (Keene et al. Reference Keene, Bladon, McKenzie, Liu, O'Keefe and Eichenbaum2016; Maass et al. Reference Maass, Berron, Libby, Ranganath and Düzel2015; Schultz et al. Reference Schultz, Sommer and Peters2012). Moreover, investigation of connection pathways in the MTL suggests that the hippocampus should not be treated as a unitary region, but has distinct connectivity preference along its anterior-posterior portions and as a function of its subfields (Aggleton Reference Aggleton2012; Libby et al. Reference Libby, Ekstrom, Ragland and Ranganath2012). The perirhinal cortex has preferential connection with anterior CA1 and subiculum, whereas the parahippocampal cortex connects more with the posterior CA1/CA2/CA3/dentate gyrus and subiculum.

2.1.4. Whole-brain network models

However, the MTL is not the only region that contribute to recollection and familiarity. As notably evidenced by neuroimaging studies, recollection also involves the posterior cingulate cortex, the retrosplenial cortex, the inferior parietal cortex, the medial prefrontal cortex, anterior nuclei of the thalamus and mammillary bodies (Aggleton & Brown Reference Aggleton and Brown1999; Ranganath & Ritchey Reference Ranganath and Ritchey2012). This network has been labeled the general recollection network (Rugg & Vilberg Reference Rugg and Vilberg2013). The extended cerebral network for familiarity involves, besides the perirhinal cortex, the ventral temporal pole, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the dorsomedial nuclei of the thalamus, and the intraparietal sulcus (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Suzuki and Rugg2013; Kim Reference Kim2010; Ranganath & Ritchey Reference Ranganath and Ritchey2012). Currently, very few theoretical models of recollection and familiarity have integrated these large-scale cerebral memory networks. Recently, however, Ranganath and colleagues (Ranganath & Ritchey Reference Ranganath and Ritchey2012; Ritchey et al. Reference Ritchey, Libby, Ranganath, O'Mara and Tsanov2015) revised the binding of item and context model to suggest that the MTL regions are actually part of two broad memory systems. The perirhinal cortex is considered as a core component of an extended anterior temporal system that also includes the ventral temporopolar cortex, lateral orbitofrontal cortex, and amygdala. This system may be essential for processing entities (that is, people and things), and would be involved in item familiarity. In contrast, the parahippocampal cortex is considered as core component of an extended posterior medial network that includes the mammillary bodies and anterior thalamic nuclei, presubiculum, the retrosplenial cortex, and the default network (comprising the posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, lateral parietal cortex, and medial prefrontal cortex). It would be involved in tasks that require a mental representation of the relationships between entities, actions, and outcomes, such as recollection-based memory tasks. Such models considering the whole-brain network architecture of memory processes are critical, given the fundamentally interconnected nature of brain structures.

Currently, yet, some aspects of recollection and familiarity have not been fully integrated in memory models. In particular, current models do not encompass the notion that explicit memory judgments and experiences, such as feelings of remembering and familiarity, arise from attribution mechanisms that interpret memory signals, such as fluency cues (Voss et al. Reference Voss, Lucas and Paller2012; Whittlesea Reference Whittlesea2002), and take into account expectations in a particular context (Bodner & Lindsay Reference Bodner and Lindsay2003; McCabe & Balota Reference McCabe and Balota2007; Westerman et al. Reference Westerman, Lloyd and Miller2002). A line of research considers how feelings of familiarity emerge when previous exposure to some information induces a sense of facilitated processing (i.e., fluency feeling) that is attributed to past occurrence of the information (Westerman et al. Reference Westerman, Lloyd and Miller2002; Whittlesea & Williams Reference Whittlesea and Williams2001a; Reference Whittlesea and Williams2001b). Similarly, both fluency signals and attribution mechanisms may also contribute to the experience of recollection (Brown & Bodner Reference Brown and Bodner2011; Li et al. Reference Li, Taylor, Wang, Gao and Guo2017; McCabe & Balota Reference McCabe and Balota2007).

Here, we propose to integrate the current state of knowledge about the neurocognitive bases of recollection and familiarity by incorporating, into a single model, separate lines of research, namely neural models of recollection and familiarity and attributional models of memory experiences. This integrative memory model builds on currently most influential dual-process views of the cognitive and neural bases of recollection and familiarity, and takes into account the highly interconnected nature of the human brain in order to propose a distributed and interactive neurocognitive architecture of representations and operations underlying recollection or familiarity.

3. The integrative memory model: A neurocognitive architecture of recollection and familiarity

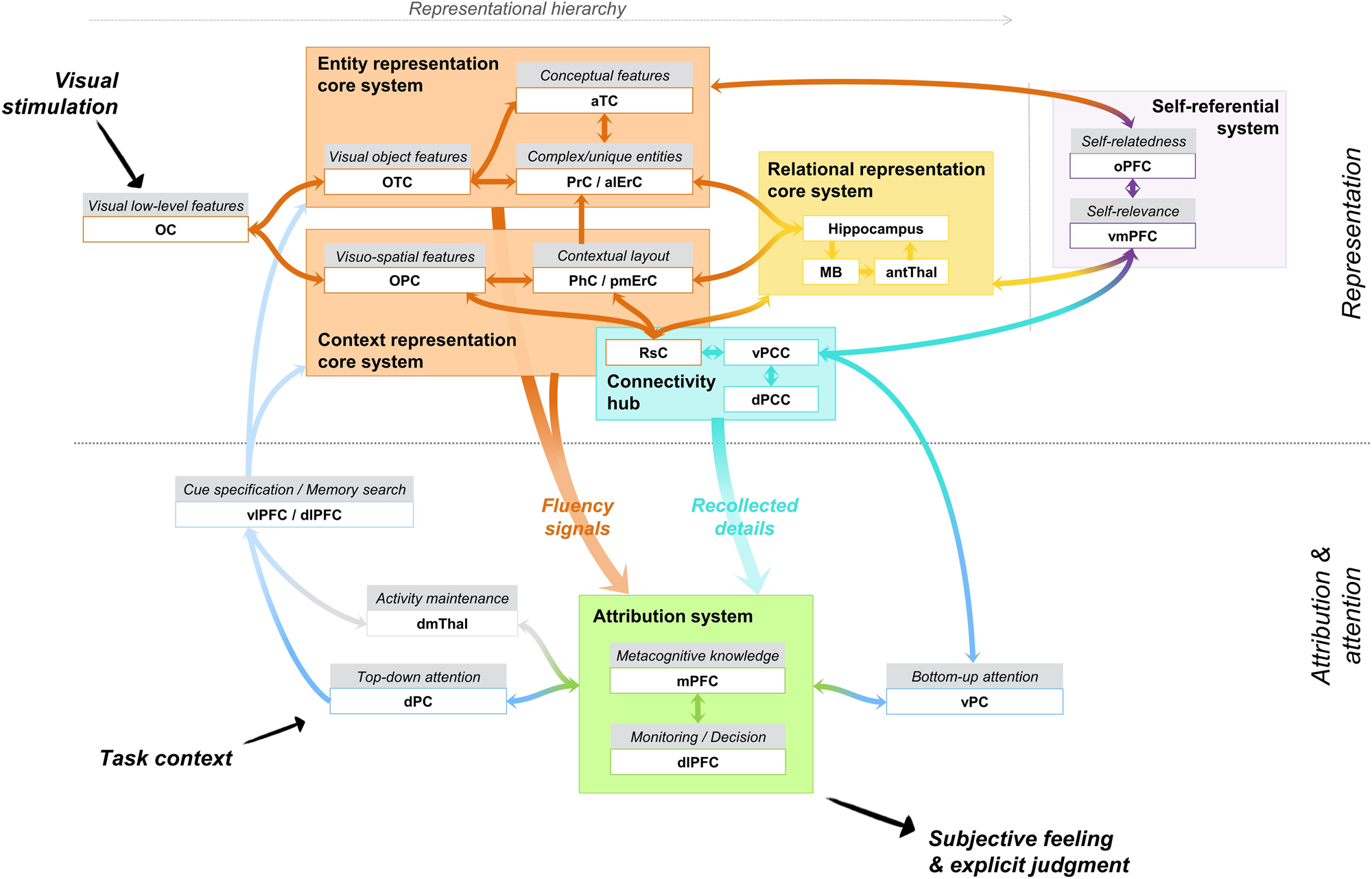

The notion of recollection and familiarity has been used to refer to processes and subjective experiences, leading sometimes to confusion between these aspects. In the integrative memory model (see our Figure 1), we describe recollection and familiarity as the interaction between core systems that store specific types of representations uniquely shaped by specific computational operations and make up the content of the memory and an attribution system framed by the task context that translates content reactivation into a subjective experience. Recollection emerges preferentially from reactivation of traces from a relational representation core system, whereas familiarity emerges mainly from reactivation of traces from the entity representation core system.

Figure 1. Integrative memory model. Key: OC: occipital cortex; OTC: occipito-temporal cortex; PrC: perirhinal cortex; aTC: anterior temporal cortex; alERC: anterolateral entorhinal cortex; PhC: parahippocampal cortex; OPC: occipito-parietal cortex; pmERC: posteromedial entorhinal cortex; antThal: anterior nuclei of the thalamus; MB: mamillary bodies; RsC: restrosplenial cortex; vPCC: ventral posterior cingulate cortex; dPCC: dorsal posterior cingulate cortex; oPFC: orbital prefrontal cortex; (v)mPFC: (ventro)medial prefrontal cortex; vPC: ventral parietal cortex; dlPFC: dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; dPC: dorsal parietal cortex; vlPFC: ventrolateral prefrontal cortex; dmThal: dorsomedial nuclei of the thalamus.

The distinction between core systems and an attribution system has two implications. First, the core systems build the memory trace and damage to these systems induces severe degradation of the content of the memory. In contrast, the attribution system modulates the use of memory traces as a function of expectancies, task context, and goals, leading to subjective experiences and explicit judgments. Lesion of the attribution system affects mainly the quality and adequation of the memory output to the task at hand. Second, although most memory situations generate an explicit output that matches the content of the memory (e.g., recollection follows reactivation of a relational representation), this might not always be the case. This means that the qualitative and subjective experience that one has in a given memory task may dissociate from the memory reconstructed by a core system. For instance, even if the relational representation core system reactivates specific item-context details, one may experience a feeling of familiarity. This is because explicit outputs during a memory task (i.e., old/new decisions, confidence judgments, and subjective experiences of remembering or knowing) follow from processing the outputs of the relational or entity representation core system in an attribution system. We assume that the attribution mechanisms are common down-stream mechanisms that serve both recollection and familiarity. In this framework, recollection and familiarity are considered as independent processes, in the sense that the underlying memory representation can be retrieved via the entity representation core system only, the relational representation core system only, or via both concomitantly (Jacoby et al. Reference Jacoby, Yonelinas, Jennings, Cohen and Schooler1997).

4. Detailed description of the integrative memory model

4.1. Encoding

Core systems are specialized for encoding and storing specific kinds of representations. The nature of the information that is processed in each core system is determined by the computational operations and level of associativity that characterize its constituent brain regions. Although each core system must be viewed as a representation system rather than as harboring recollection or familiarity processes, we suggest that recollection and familiarity are preferentially associated with specific types of representations: relational representations (centered on the hippocampus) for recollection, and entity representations (centered on the perirhinal cortex) for familiarity. Consistently, fMRI studies examining encoding-related activities observed that hippocampal activity is predictive of subsequent source recollection but uncorrelated with item recognition, and that perirhinal activity predicts item familiarity–based recognition, but not subsequent recollection (Davachi et al. Reference Davachi, Mitchell and Wagner2003; Kensinger & Schacter Reference Kensinger and Schacter2006; Ranganath et al. Reference Ranganath, Yonelinas, Cohen, Dy, Tom and D'Esposito2004). Recollection of details from the initial experience of an event also usually relies on contextual information that is stored in a context representation core system, but, as detailed below, some contextual tagging of entities occurs and elements of context (e.g., a building) may be subsequently recognized as familiar. Finally, the notion that these objects, people, and events have been personally experienced is recorded by the interaction between representation core systems and a self-referential system.

In the entity representation core system, encountered entities pertaining to experienced events are encoded. An entity is defined as an exemplar item (i.e., token) from a category (i.e., type) that distinguishes itself from other similar items thanks to its unique configuration of perceptivo-conceptual features. The entity representation core system comprises the perirhinal cortex, anterolateral enthorinal cortex, occipitotemporal cortex, and anterior temporal cortex. Of note, even if the entorhinal cortex has a hierarchically higher level of associativity than the perirhinal cortex (Lavenex & Amaral Reference Lavenex and Amaral2000) and recent data speak for a specific role of the anterolateral entorhinal cortex in object-in-context processing (Yeung et al. Reference Yeung, Olsen, Hong, Mihajlovic, D'Angelo, Kacollja, Ryan and Barense2019), there are currently not sufficient data to clearly distinguish the role of the perirhinal cortex and the anterolateral entorhinal cortex. Based on studies showing a role for the anterolateral entorhinal cortex in disambiguation of similar objects (Yeung et al. Reference Yeung, Olsen, Bild-Enkin, D'Angelo, Kacollja, McQuiggan, Keshabyan, Ryan and Barense2017), we will consider here that the perirhinal cortex and anterolateral entorhinal cortex together form a system specialized for entity representation. This system is dedicated to the processing and encoding of single entities (Ranganath & Ritchey Reference Ranganath and Ritchey2012), with preferential represention of objects and faces (Kafkas et al. Reference Kafkas, Migo, Morris, Kopelman, Montaldi and Mayes2017; Martin et al. Reference Martin, Cowell, Gribble, Wright and Kohler2016), unified associations (Haskins et al. Reference Haskins, Yonelinas, Quamme and Ranganath2008), and pairings of similar entities (e.g., two faces) (Hirabayashi et al. Reference Hirabayashi, Takeuchi, Tamura and Miyashita2013; Mayes et al. Reference Mayes, Montaldi and Migo2007). It has been suggested to additionally represent the association of a written concrete word with its corresponding object concept (Bruffaerts et al. Reference Bruffaerts, Dupont, Peeters, De Deyne, Storms and Vandenberghe2013; Liuzzi et al. Reference Liuzzi, Bruffaerts, Dupont, Adamczuk, Peeters, De Deyne, Storms and Vandenberghe2015).

Critically, the entity representation core system is defined by the nature and complexity of the representations it can process and encode for long-term memory after a single exposure to the stimulus. More specifically, in line with the representational-hierarchial view (Cowell et al. Reference Cowell, Bussey and Saksida2010; Graham et al. Reference Graham, Barense and Lee2010; Saksida & Bussey Reference Saksida and Bussey2010), there is a hierarchy in terms of the complexity of the representation in the entity representation core system. Consider here the example of object processing (Fig. 1). While individual features (e.g., shape, texture, color) are processed in ventral occipitotemporal areas (visual object features), integration of these features into more and more complex entities are achieved as one moves anteriorly along the ventral visual stream. It is at the level of the perirhinal cortex and anterolateral entorhinal that all visual features are integrated in a single complex representation of the object that can be discriminated from other objects with overlapping features. Moreover, the perirhinal cortex may also act as a conceptual binding site. Whereas defining conceptual features such as the category are represented in the anterior temporal areas, the integration of the meaning to object representations will occur in the perirhinal cortex via its interaction with the anterior temporal area (conceptual features) (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Douglas, Newsome, Man and Barense2018; Price et al. Reference Price, Bonner, Peelle and Grossman2017; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Devereux and Tyler2011). Indeed, the perirhinal cortex is notably recruited when concepts with confusable features must be distinguished (Clarke & Tyler Reference Clarke and Tyler2015). For instance, the perirhinal cortex is needed to distinguish between living things during naming (and recognition memory tasks), as living things share a lot of common features and are more easily confusable than non-living things (Kivisaari et al. Reference Kivisaari, Tyler, Monsch and Taylor2012; Wright et al. Reference Wright, Randall, Clarke and Tyler2015). By incorporating features from various sensory and conceptual areas, the perirhinal/anterolateral entorhinal cortex forms unique conjunctive representations of entities allowing the resolution of ambiguity in the face of objects with overlapping features and the identification of objects in a viewpoint-invariant manner (Erez et al. Reference Erez, Cusack, Kendall and Barense2016). These representations rely on a computational property of the perirhinal/anterolateral entorhinal cortex that can be referred to as entity pattern separation, by which similar objects are given separate representations based on specific conjunctions of features, even after a single exposure (Kent et al. Reference Kent, Hvoslef-Eide, Saksida and Bussey2016). This property allows humans to quickly recognize familiar objects in the stream of resembling objects from the environment.

Given that entities are typically experienced as part of an event, the perirhinal/anterolateral entorhinal cortex also encodes the significance of entities in a context-dependent manner (Inhoff & Ranganath Reference Inhoff and Ranganath2015; Ranganath & Ritchey Reference Ranganath and Ritchey2012; Yeung et al. Reference Yeung, Olsen, Hong, Mihajlovic, D'Angelo, Kacollja, Ryan and Barense2019). This is possible thanks to the connections between the perirhinal cortex and the parahippocampal/posteromedial entorhinal cortex, which is part of the context representation core system together with the occipitoparietal cortex and retrosplenial cortex. The parahippocampal cortex represents, preferentially, buildings and scenes, which often constitute the contextual setting for an event (Bar et al. Reference Bar, Aminoff and Schacter2008; Kafkas et al. Reference Kafkas, Migo, Morris, Kopelman, Montaldi and Mayes2017; Martin et al. Reference Martin, McLean, O'Neil and Kohler2013; Preston et al. Reference Preston, Bornstein, Hutchinson, Gaare, Glover and Wagner2010), and the posteromedial entorhinal cortex encodes an internally generated grid of the spatial environment (Doeller et al. Reference Doeller, Barry and Burgess2010). The context representation core system would provide a contextual tagging of the entity, which allows us to take into account the background in which the entity occurred and give distinct meanings and values to the entity. In their article, Inhoff and Ranganath (Reference Inhoff and Ranganath2015) give the example of a ticket purchased at a county fair to buy food and rides, whose significance changes beyond the fairgrounds because that same ticket would have little value outside the fair. In addition, we recognize entities that we have personally experienced. Self-reference is also important to define the significance of entities. Via connections of the perirhinal cortex to the orbital prefrontal cortex (Lavenex et al. Reference Lavenex, Suzuki and Amaral2002), the entity representation may also record the self-relatedness of the entity (D'Argembeau et al. Reference D'Argembeau, Collette, Van der Linden, Laureys, Del Fiore, Degueldre, Luxen and Salmon2005; Northoff et al. Reference Northoff, Heinzel, de Greck, Bermpohl, Dobrowolny and Panksepp2006). Like the contextual significance, self-relatedness of entities may modulate our behavior with regard to the entities. For example, a piece of clothing should lead to different behaviors depending on whether it belongs to me or somebody else.

In brief, entities encountered as part of experienced events are stored in long-term memory in a distributed and hierarchical manner in the entity representation core system. While simple perceptual and conceptual features are represented in occipitotemporal and anterior temporal areas, the conjunctions of multimodal features are represented as pattern-separated entities in the perirhinal cortex and the anterolateral entorhinal cortex. Some contextual and self-related tagging via interactions between the entity representation core system and the context representation core system and self-reference system will modulate the significance of entities. The concept of unification is close to the notion of conjunction, with the difference that unification can sometimes be an active encoding strategy whereas conjunction refers to the configurational nature of stimuli. Indeed, unification consists in encoding different pieces of information in a way that integrates them into a single entity (Parks & Yonelinas Reference Parks and Yonelinas2015). Previous fMRI studies have shown that processing object-color associations by mentally integrating color as an object feature activates the perirhinal cortex (Diana et al. Reference Diana, Yonelinas and Ranganath2010), as does the encoding of word pairs as new compound words (Haskins et al. Reference Haskins, Yonelinas, Quamme and Ranganath2008).

The relational representation core system involves the hippocampus, subiculum, mamillary bodies, and the anterior nuclei of the thalamus. It rapidly encodes a detailed representation of the item bound to associated contextual information (Montaldi & Mayes Reference Montaldi and Mayes2010; Ranganath & Ritchey Reference Ranganath and Ritchey2012) or more generally complex high-resolution bindings (Yonelinas Reference Yonelinas2013). In the case of item-context binding, inputs consist in the entity representations from the perirhinal/anterolateral entorhinal cortex entering the hippocampus anteriorly, and context representations (e.g., spatial layout) from the parahippocampal/posteromedial entorhinal cortex entering the hippocampus posteriorly (Ranganath & Ritchey Reference Ranganath and Ritchey2012; Staresina et al. Reference Staresina, Duncan and Davachi2011). The context representation in the parahippocampal cortex is itself fed by inputs from neocortical regions that represent the specific contents of the context in which the item is embedded (e.g., sounds, visual details, and spatial layout), stored in occipitoparietal sites (visuospatial processing; Rissman & Wagner Reference Rissman and Wagner2012), and brought to the parahippocampal cortex via the retrosplenial cortex. The self-referential nature of the experienced episodes is also embedded in the memory trace thanks to connection of the hippocampus and retrosplenial cortex with the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (Andrews-Hanna et al. Reference Andrews-Hanna, Reidler, Sepulcre, Poulin and Buckner2010). The binding of multimodal and qualitatively different pieces of information occurs in the hippocampus (CA3 via the dentate gyrus) where each unique episode is encoded as a separate represention via relational pattern separation (Berron et al. Reference Berron, Schutze, Maass, Cardenas-Blanco, Kuijf, Kumaran and Duzel2016; Leal & Yassa Reference Leal and Yassa2018; Montaldi & Mayes Reference Montaldi and Mayes2010; Norman & O'Reilly Reference Norman and O'Reilly2003), so that two very similar events will have two distinct memory traces. For instance, if we attend two concerts based on the same album of our favorite band, we will still be able to remember the details of each concert as a unique episode.

This pattern-separated representation in the hippocampus constitutes a summary, or an index, of the distributed neocortical representations of the specific details of the episodes (Teyler & Rudy Reference Teyler and Rudy2007). Contrary to the conjunctive representations in the entity representation core system where components are fused in a frozen integrated trace, the hippocampal representation keeps components separate and flexibly bound (Eichenbaum Reference Eichenbaum2017c). This allows the learning of inferences between items that are indirectly related, and subsequent flexible use of representations (Eichenbaum & Cohen Reference Eichenbaum and Cohen2014). So, relational binding and pattern separation are the core computational properties of the relational representation core system.

While the nature of the representations in the entity representation core system makes it specialized for rapidly signaling that objects, faces, and simple combinations of those are known (i.e., familiarity judgments), the bound representations in the relational representation core system makes it specialized for reactivating the specific details of experienced events (i.e., recollection). In other words, familiarity and recollection are processes that emerge naturally from the ways in which different brain regions represent the experienced world. But, as will be detailed next, the final explicit memory output will depend on the attribution system.

4.2. Retrieval

4.2.1. Familiarity-based retrieval

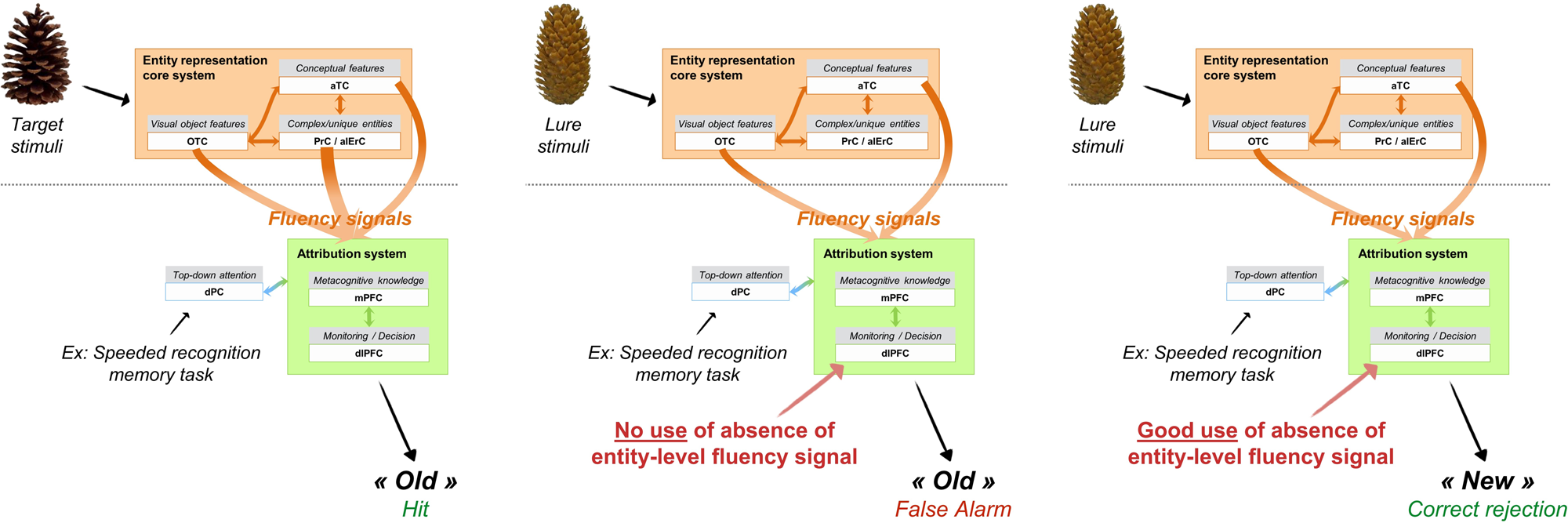

As illustrated in Figure 2, the typical sequence of operations leading to familiarity starts with the repetition of an encoded entity (Montaldi & Mayes Reference Montaldi and Mayes2010; Ranganath Reference Ranganath2010; Voss et al. Reference Voss, Lucas and Paller2012). For instance, during a recognition memory test, target items are the replication of previously studied items. In our example of the processing of an object item, the repetition of the perceptual and/or conceptual features of the item triggers enhanced processing fluency (and reduced activity) in the occipitotemporal and anterior temporal areas where these features were first processed (Reber Reference Reber2013). Several fMRI studies also showed that enhanced processing fluency of items induces a reduction of activity in the perirhinal cortex that predicts familiarity-based memory (Dew & Cabeza Reference Dew and Cabeza2013; Gonsalves et al. Reference Gonsalves, Kahn, Curran, Norman and Wagner2005; Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Mecklinger and Friederici2010). Here, we make the novel hypothesis that the perirhinal and anterolateral entorhinal cortices are sensitive to the repetition of the actual conjunction of features that makes up the specific and viewpoint-invariant representation of the item, associated with a specific meaning, and thus generates enhanced entity-level processing fluency and can lead to familiarity for this entity. In addition, any region representing features of the previously encountered object can reactivate these specific features when re-exposed to them and thus generates familiarity-based memory through fluency. So, perceptual and conceptual fluency for features arising in occipitotemporal and anterior temporal cortices can also generate familiarity for these features. The dominant type of signal that will contribute to familiarity depends on the characteristics of the memory task (Lanska et al. Reference Lanska, Olds and Westerman2014; Lucas & Paller Reference Lucas and Paller2013; Taylor & Henson Reference Taylor and Henson2012b). For instance, in a task where participants have to rapidly discriminate between old pictures of objects and new pictures of completely different objects (e.g., Besson et al. Reference Besson, Ceccaldi, Tramoni, Felician, Didic and Barbeau2015), reactivation of simple perceptual features (e.g., a small grey fluffy object for the picture of a grey kitten) or conceptual features (e.g., a feline) is sufficient to successfully identify the studied stimuli. In contrast, if old objects are mixed with very similar objects from the same category (e.g., Yeung et al. Reference Yeung, Ryan, Cowell and Barense2013), accurate familiarity-based discrimination will rely on the reactivation of the studied conjunctions of features. This implies that familiarity may arise from different regions, depending on the materials (e.g., Kafkas et al. Reference Kafkas, Migo, Morris, Kopelman, Montaldi and Mayes2017) and demands of the task, and that lesions to the perirhinal cortex will not necessarily affect all forms of familiarity.

Figure 2. Main mechanisms supporting familiarity-based retrieval in the example of a lab-based object recognition memory task with resembling targets and lures.

Besides fluency signals, other signals may also operate in recognition memory tasks. We focus here on fluency signals because we wish to model recognition memory decisions that allow the brain to identify a specific stimuli as previously encountered. Item-specific discrimination is a key property of familiarity in everyday life, as we adapt our behavior to familiar unique entities. For instance, we will speak to people we know, we will take our own cup to fetch some coffee, we will pick up our coat among others in a cloakroom, and so forth. For all these situations, we propose that fluency-based familiarity is central. However, feelings of familiarity can arise from many other sources. Some of them are non-memory, such as affective information (Duke et al. Reference Duke, Fiacconi and Köhler2014) or proprioceptive information (Fiacconi et al. Reference Fiacconi, Peter, Owais and Köhler2016) that have been shown to generate a subjective sense of familiarity if manipulated in memory situations. Others are from the memory domain, but support global matching or similarity judgments when a presented stimulus globally maps onto a stored representation (Norman & O'Reilly Reference Norman and O'Reilly2003). But even then, the involvement of fluency in the emergence of a feeling of familiarity through affective information, proprioceptive information, or global matching cannot be ruled out (Duke et al. Reference Duke, Fiacconi and Köhler2014).

Still, whatever its source, enhanced processing fluency in itself is not sufficient to produce familiarity. It has been suggested that fluency only minimally contributes to memory decisions because some patients with amnesia demonstrate chance-level recognition memory (hence, no sign of familiarity), despite successfully completing priming tasks conducted on the same set of stimuli (priming being also driven by fluency) (e.g., Levy et al. Reference Levy, Stark and Squire2004). In the same vein, enhancing the processing fluency of some stimuli had only a small influence on amnesic patients’ memory performance in some studies (Conroy et al. Reference Conroy, Hopkins and Squire2005; Verfaellie & Cermak Reference Verfaellie and Cermak1999), while other studies found reliable improvement of recognition memory performance in amnesia following manipulation that enhanced processing fluency (Keane et al. Reference Keane, Orlando and Verfaellie2006). Such findings can be explained if one considers that the transformation of fluency signals into familiarity-based decisions involves complex cognitive and metacognitive mechanisms (Whittlesea & Williams Reference Whittlesea and Williams2000; Willems et al. Reference Willems, van der Linden and Bastin2007). Accordingly, our integrative memory model argues that one cannot explain familiarity-based memory decisions without considering the role of the attribution system.

Therefore, explicit familiarity judgments and the subjective feeling of familiarity result from attribution of fluency to the prior occurrence of the stimulus (via the attribution system) (Whittlesea & Williams Reference Whittlesea and Williams2000). The fluency heuristic relies on signal flow from the entity representation core system regions to the attribution system, via connections between the perirhinal cortex and the prefrontal cortex (mainly, orbitofrontal, medial, and dorsolateral prefrontal areas; see Aggleton & Brown Reference Aggleton and Brown1999; Lavenex et al. Reference Lavenex, Suzuki and Amaral2002; Libby et al. Reference Libby, Ekstrom, Ragland and Ranganath2012). The mechanisms thought to intervene in the attribution system, such as metacognitive and monitoring operations, have been notably associated with the prefrontal cortex in the context of memory tasks (Chua et al. Reference Chua, Pergolizzi, Weintraub, Fleming and Frith2014; Henson et al. Reference Henson, Rugg, Shallice, Josephs and Dolan1999). Direct involvement in the fluency heuristic comes from electrophysiological studies (i.e., event-related potentials) (Kurilla & Gonsalves Reference Kurilla and Gonsalves2012; Wolk et al. Reference Wolk, Schacter, Berman, Holcomb, Daffner and Budson2004), notably showing that the attribution of fluency to the past versus the disqualification of fluency as a memory cue was associated with late frontal potentials.

The fluency heuristic involves sophisticated monitoring and metacognitive mechanisms. First, the metacognitive knowledge (supported by medial prefrontal areas) that fluent processing is a sign of prior occurrence exists since childhood (Geurten et al. Reference Geurten, Lloyd and Willems2017; Olds & Westerman Reference Olds and Westerman2012; Oppenheimer Reference Oppenheimer2008); but this metacognitive heuristic can be unlearned through regular encounter with memory errors, as this might be the case for patients with severe memory problems (Geurten & Willems Reference Geurten and Willems2017). Second, the characteristics of the specific task at hand will determine the relevance of using fluency signals. This is determined via several monitoring mechanisms, supported by dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and that may happen at a non-conscious level. Fluency cues will be used if they are expected as diagnostic cues for recognition decisions (Westerman et al. Reference Westerman, Lloyd and Miller2002) and if the experienced fluency is salient relative to the context (Jacoby & Dallas Reference Jacoby and Dallas1981; Westerman Reference Westerman2008). People set an internal criterion along the varying dimension of memory strength depending on the task specificities. A feeling of surprise is experienced when the intensity of the fluency signal exceeds this criterion (Yonelinas et al. Reference Yonelinas, Aly, Wang and Koen2010). If no alternative source is detected to explain the intensity of this signal, fluency will be attributed to past occurrence and will give rise to a feeling of familiarity. If not so attributed, fluency will be disregarded and no feeling of familiarity will arise.

Such an explicit judgment of familiarity occurs when top-down attention, supported by the dorsal parietal cortex, is focused on recognition memory decisions. According to the attention-to-memory model (Cabeza et al. Reference Cabeza, Ciaramelli, Olson and Moscovitch2008; Ciaramelli et al. Reference Ciaramelli, Grady and Moscovitch2008), the dorsal parietal cortex allocates attentional resources to memory retrieval according to the goals of the person who remembers, and is often involved in familiarity-based decisions because familiarity may induce low confidence. This is the case in recognition memory paradigms where participants must judge how familiar stimuli are, but this can also occur in daily life (e.g., judging the most familiar brand of an article at the supermarket in order to choose the one usually bought). Yet, this explicit expression of familiarity may be distinguished from the subjective feeling of familiarity. Although both often co-occur in memory tasks – so that a participant can gauge how strong is his or her feeling of familiarity during confidence judgments, for example – a strong feeling of familiarity may sometimes arise outside of any memory task and capture attention in a bottom-up fashion. One typical example is the butcher-on-the-bus phenomenon where one is surprised by the involuntary strong feeling of knowing the person, albeit in the absence of any recollection.

To come back to the cases where amnesic patients failed to use fluency cues in recognition memory tasks despite preserved perceptual or conceptual fluency, a likely interpretation in the framework of the attribution system considers that this is due to changes in metacognitive knowledge and monitoring in amnesic patients compared to controls (Geurten & Willems Reference Geurten and Willems2017). More specifically, because of their continued experience of memory errors in everyday life, amnesic patients may have modified their metacognitive knowledge so as to unlearn the fluency heuristic (Geurten & Willems Reference Geurten and Willems2017; Ozubko & Yonelinas Reference Ozubko and Yonelinas2014). Additionally, their expectations relative to the origin of fluency feelings may have adapted in a way that makes them readier to detect alternative sources to fluency (Geurten & Willems Reference Geurten and Willems2017). Altogether, this will lead them to disqualify fluency as a cue for memory decisions (Conroy et al. Reference Conroy, Hopkins and Squire2005; Ozubko & Yonelinas Reference Ozubko and Yonelinas2014; Verfaellie & Cermak Reference Verfaellie and Cermak1999), unless other fluency sources are very difficult to detect (Keane et al. Reference Keane, Orlando and Verfaellie2006).

In initial network models (Aggleton & Brown Reference Aggleton and Brown1999), the dorsomedial nucleus of the thalamus has been considered as a node within the familiarity system. However, its critical involvement remains unclear because of the divergence of findings relative to a selective impairment of familiarity following lesion to the dorsomedial thalamus (Danet et al. Reference Danet, Pariente, Eustache, Raposo, Sibon, Albucher, Bonneville, Péran and Barbeau2017; Edelstyn et al. Reference Edelstyn, Grange, Ellis and Mayes2016). Theoretical positions about the role of this region currently diverge. On the one hand, the dorsomedial thalamus could support familiarity, but the loss of inputs to the prefrontal cortex following damage to this region would have wider consequences on cognition, with possible impact on recollection (Aggleton et al. Reference Aggleton, Dumont and Warburton2011). On the other hand, it could have a general role in several cognitive domains by virtue of its regulatory function over the prefrontal cortex, allowing the maintenance of frontal activity over delays necessary to perform complex reflections and decisions (Pergola et al. Reference Pergola, Danet, Pitel, Carlesimo, Segobin, Pariente, Suchan, Mitchell and Barbeau2018). In a recognition memory task, the dorsomedial thalamus was found to become critical when interference between stimuli increased (Newsome et al. Reference Newsome, Trelle, Fidalgo, Hong, Smith, Jacob, Ryan, Rosenbaum, Cowell and Barense2018). Following on this latter view (Pergola et al. Reference Pergola, Danet, Pitel, Carlesimo, Segobin, Pariente, Suchan, Mitchell and Barbeau2018), in the integrative memory model we have positioned the dorsomedial thalamus as a modulator of prefrontal activity, such that it would support the maintenance of prefrontal activities during tasks that are demanding in terms of attribution processes (e.g., discrimination between similar interfering stimuli).

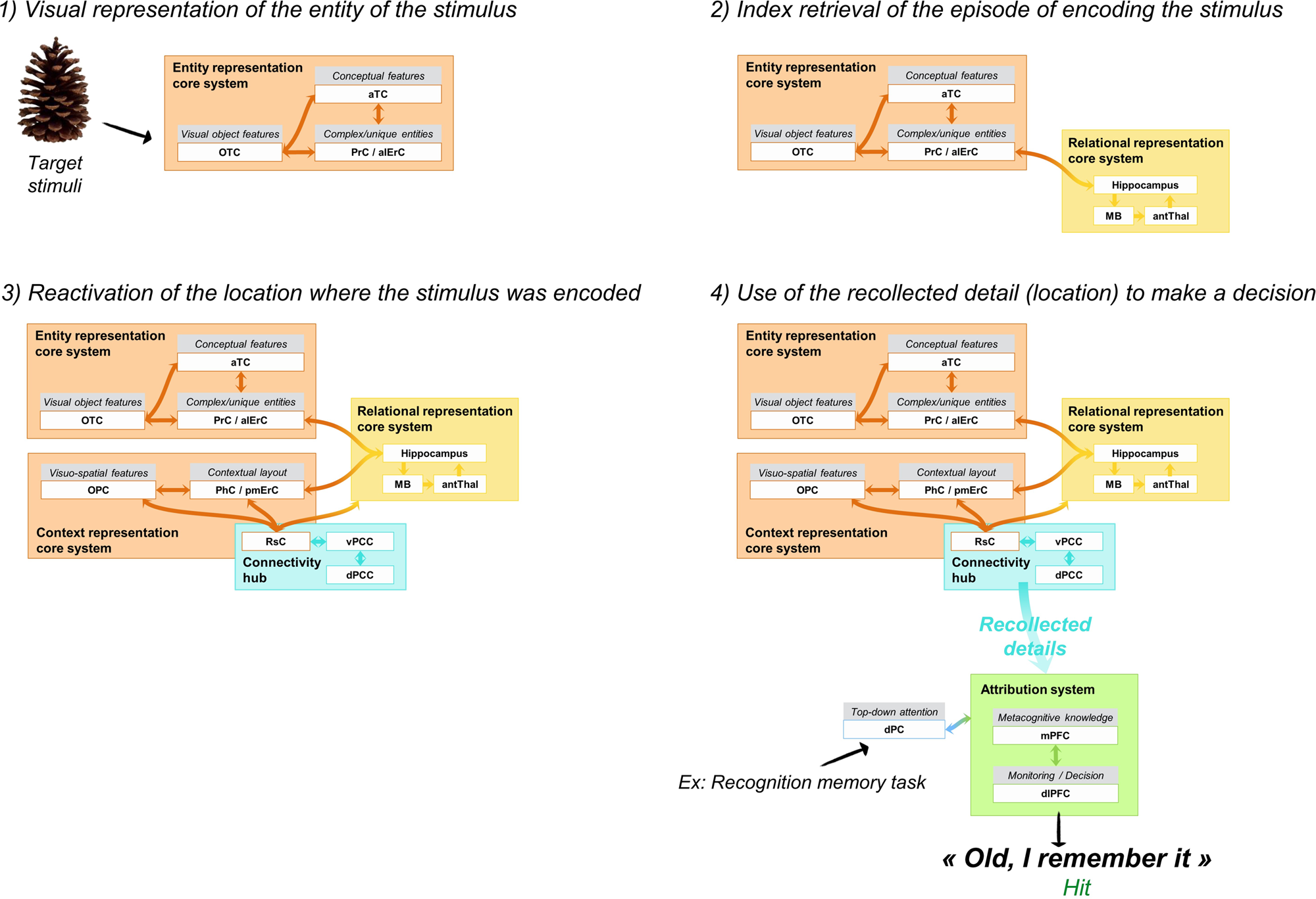

4.2.2. Recollection-based retrieval

Figure 3 illustrates the mechanisms involved in recollection-based retrieval. Typically, recollection-based retrieval starts with exposition to partial information from a past episode (either an entity or elements of the context). The partial information cue triggers the reactivation of the complete pattern via pattern completion within the hippocampus (CA3/CA1) (Norman & O'Reilly Reference Norman and O'Reilly2003; Staresina et al. Reference Staresina, Cooper and Henson2013). As the pattern stored in the hippocampus is an index of distributed contents in the neocortex, its reactivation induces the reinstatement of stimulus-specific neocortical representations (Rissman & Wagner Reference Rissman and Wagner2012; Staresina et al. Reference Staresina, Cooper and Henson2013) in such a way that the contents that were processed when the event was initially experienced and encoded are reactivated at retrieval. Thus, the sensory-perceptual and visuo-spatial details of the memory (e.g., object features, persons’ characteristics, spatial configuration, sounds) stored in posterior cerebral areas are brought back. The signal from the hippocampal index is transferred to distributed neocortical sites via the mammillary bodies (connected to the hippocampus by the fornix), the anterior nuclei of the thalamus, and the retrosplenial cortex (Brodmann areas BA29 and BA30). In other words, Papez's circuit is the core pathway for recollecting the content of past experienced episodes (Aggleton & Brown Reference Aggleton and Brown1999).

Figure 3. Illustration of the main steps for a recollection-based memory judgment in the example of an object recognition memory task (following encoding of objects in various spatial locations).

In addition to strong connections with the hippocampus and anterior thalamus, the retrosplenial cortex is linked to the parahippocampal cortex, occipital areas, and adjacent posterior cingulate cortex (BA23 and BA31) (Kobayashi & Amaral Reference Kobayashi and Amaral2003; Parvizi et al. Reference Parvizi, Van Hoesen, Buckwalter and Damasio2006; Suzuki & Amaral Reference Suzuki and Amaral1994; Vogt & Pandya Reference Vogt and Pandya1987; Vogt et al. Reference Vogt, Pandya and Rosene1987). The posterior cingulate cortex and the retrosplenial cortex appear to play a pivotal role as interfaces between the hippocampus and the neocortex, thanks to their highly connected nature. Indeed, they have been identified as hubs of connectivity (Hagmann et al. Reference Hagmann, Cammoun, Gigandet, Meuli, Honey, Wedeen and Sporns2008; van den Heuvel & Sporns Reference van den Heuvel and Sporns2013). However, the different patterns of connection of the retrosplenial cortex and posterior cingulate cortex suggest different contributions (Greicius et al. Reference Greicius, Supekar, Menon and Dougherty2009). As a gateway between the hippocampus and regions storing the sensory-perceptual details of the memory (especially, visuo-spatial information in the parahippocampal cortex and occipitoparietal cortex), the retrosplenial is a key region for enabling cortical reinstatement of the content of memories. It is part of the context representation core system, and its damage will likely prevent content reactivation and lead to amnesia (Aggleton Reference Aggleton2010; Valenstein et al. Reference Valenstein, Bowers, Verfaellie, Heilman, Day and Watson1987; Vann et al. Reference Vann, Aggleton and Maguire2009a).

In contrast, the posterior cingulate cortex sits outside the context and relational representation core systems because it does not contribute to recollecting the content of episodes like the retrosplenial cortex does. Intracranial recordings from posterior cingulate sites in epileptic patients show enhanced gamma band activity specific to autobiographical remembering (Foster et al. Reference Foster, Dastjerdi and Parvizi2012), but perturbation of posterior cingulate neurons by electric brain stimulation in the intracranial electrodes do not produce any observable behavioral responses, nor any subjective experience in the participants (Foster & Parvizi Reference Foster and Parvizi2017). By contrast, electrical stimulation of the MTL evokes a subjective experience of déjà vu/déjà vécu, reminiscence of scenes or of visual details of known objects (Barbeau et al. Reference Barbeau, Wendling, Regis, Duncan, Poncet, Chauvel and Bartolomei2005; Bartolomei et al. Reference Bartolomei, Barbeau, Gavaret, Guye, McGonigal, Regis and Chauvel2004). This suggests that the posterior cingulate cortex does not store any content related to experienced memories, but rather plays a supportive role during recollection. More specifically, the posterior cingulate cortex contributes to the quality of recollection and the subjective experience of remembering due to its central position as hub of connectivity. A distinction is made between the ventral and dorsal posterior cingulate cortex (Vogt et al. Reference Vogt, Vogt and Laureys2006). While the ventral posterior cingulate cortex connects notably with the inferior parietal cortex and ventromedial prefrontal cortex, the dorsal posterior cingulate cortex has main connections with the superior parietal cortex and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Bzdok et al. Reference Bzdok, Heeger, Langner, Laird, Fox, Palomero-Gallagher, Vogt, Zilles and Eickhoff2015; Leech et al. Reference Leech, Kamourieh, Beckmann and Sharp2011; Parvizi et al. Reference Parvizi, Van Hoesen, Buckwalter and Damasio2006; Vogt et al. Reference Vogt, Vogt and Laureys2006).

The ventral posterior cingulate cortex is part of the default mode network (Leech & Sharp Reference Leech and Sharp2014; Margulies et al. Reference Margulies, Vincent, Kelly, Lohmann, Uddin, Biswal, Villringer, Castellanos, Milham and Petrides2009), which has been associated with various internally-directed cognitive functions, such as episodic memory retrieval, self-referential processing, and mentalizing (Buckner et al. Reference Buckner, Andrews-Hanna and Schacter2008). During recollection, the ventral posterior cingulate cortex will support pattern completion by allowing the reactivation of the self-referential character of memories for personally experienced events via its connection to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (D'Argembeau Reference D'Argembeau2013). It should be noted that recollection can occur in the absense of self-referential feeling, as illustrated by the case of a patient who remembered personally experienced events with contextual details, but who had the feeling that these events did not belong to him (Klein & Nichols Reference Klein and Nichols2012). However, the lack of self-referential character in recollected memories would prevent them from inducing the subjective feeling of travelling back in time to re-experience one's past (Tulving Reference Tulving1985). Then, the sudden recovery of the whole memory trace on the basis of a simple cue (i.e., ecphory) captures bottom-up attention and engages the ventral attention network, more specifically the ventral parietal cortex (supramarginal gyrus and angular gyrus [attention-to-memory model, Cabeza et al. Reference Cabeza, Ciaramelli and Moscovitch2012]), via the ventral posterior cingulate cortex connection.

As for the dorsal posterior cingulate cortex, it is thought to be a transitional zone of connectivity, linking the default mode network and a frontoparietal network involved in executive control (Leech & Sharp Reference Leech and Sharp2014). In our integrative memory model, this frontoparietal network corresponds to the attribution system interacting with attention. Of note, the retrosplenial cortex also has direct connections with the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Kobayashi & Amaral Reference Kobayashi and Amaral2003; Vann et al. Reference Vann, Aggleton and Maguire2009a), suggesting that the posterior cingulate gyrus as a whole acts as a gateway between the hippocampally centered relational representation core system and the frontoparietal attribution and attention system. Therefore, we propose that the posterior cingulate gyrus hub of connectivity, comprising the retrosplenial cortex and posterior cingulate cortex, has a pivotal role in the integration of all the recollection-related operations and contents. It would act as a relay node allowing activation to spread from the relational representation core system throughout the entity representation core system, context representation core system, self-referential system, and the attribution system. Dysfunction of this node would disintegrate the network, preventing the full reinstatement of the memory. Consistently, Bird et al. (Reference Bird, Keidel, Ing, Horner and Burgess2015) have shown that the posterior cingulate gyrus allows the reinstatement of episodic details and the strength of the posterior cingulate reinstatement activity correlated with the amount of details that the participants could subsequently recall.

Finally, in order for the individual to report an “old” judgment based on a recollective experience, attribution mechanisms should come into play, taking into account the task context and memorability expectations (metacognitive knowledge and monitoring; McCabe & Balota Reference McCabe and Balota2007). We assume that the fundamental cognitive operations are the same as in the case of familiarity, but the nature of representations on which this applies differs. Here, the attribution system will assess, notably, the amount of recollected details (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, McDuff, Rugg and Norman2009) and their relevance (Bodner & Lindsay Reference Bodner and Lindsay2003). This implies that, even if an individual recollects qualitative details about an event, he or she may report a familiarity-based recognition decision if the retrieved information is judged irrelevant or insufficient to succeed at the task and to be qualified as recollection (e.g., “Remember” response; Bodner & Lindsay Reference Bodner and Lindsay2003). In addition, the criterion for recollection will depend on task context. For instance, in McCabe and Balota's (Reference McCabe and Balota2007) study, medium-frequency words were intermixed with high-frequency or low-frequency words at test. Remember responses were greater for medium-frequency targets when they were tested among high-frequency, as compared with low-frequency words. This suggests that participants are more likely to experience recollection when targets exceed an expected level of memorability in the context of words that were relatively less distinctive.

In line with the hypothesis that the posterior cingulate gyrus contributes to consciousness (Vogt & Laureys Reference Vogt and Laureys2005), an additional hypothesis of the integrative memory model is that the spread of activation throughout distributed brain regions via the posterior cingulate gyrus hub, the catching-up of attention related to ecphory, and the high diagnosticity of such signal in terms of evidence of past experience is equivalent to a mobilisation of a global neuronal workspace (Dehaene & Naccache Reference Dehaene and Naccache2001; Vatansever et al. Reference Vatansever, Menon, Manktelow, Sahakian and Stamatakis2015) that conveys consciousness of remembering and a feeling of re-experiencing (i.e., autonoetic consciousness). In this view, autoneotic consciousness would thus be an emerging property of integrated reactivation of the representation core systems together with the attribution system, where the posterior cingulate gyrus plays a central role.

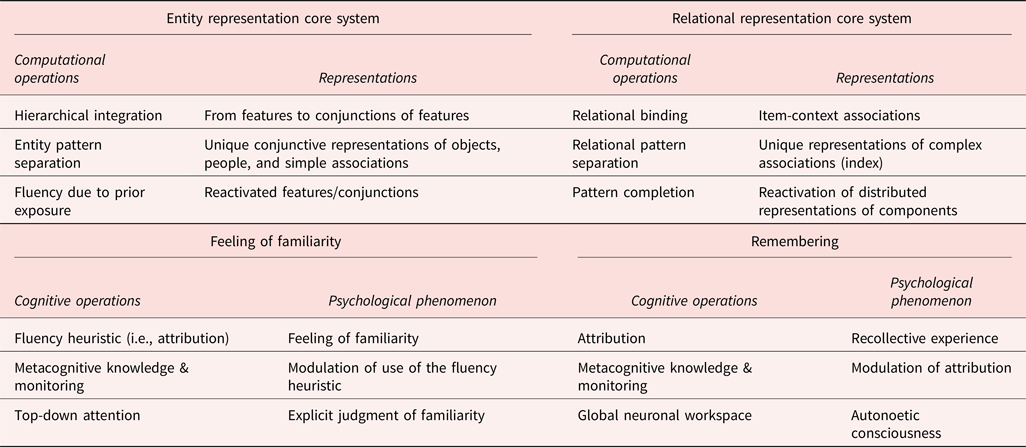

Table 1 summarizes the key computational operations and the corresponding types of content that can be represented thanks to these properties, according to the integrative memory model. We distinguish the core systems that create the memory trace, that will become available for familiarity- and recollection-based memory decisions (as well as other cognitive functions, as described in sect. 5.3 below), and the subjective experience of remembering and knowing which are emerging psychological phenomena arising from the interaction between the core systems representations and the cognitive operations of the attribution system.

Table 1. Main computational/cognitive operations and associated representations/psychological consequences in the integrative memory model.

5. Further characteristics of the integrative memory model

5.1. Interactions within the integrative memory model

Although the core systems that represent the memory traces generating recollection and familiarity are independent, it is important to consider how these systems interact. Interaction will occur when the representations from the entity and context representation core systems are used to create relational associations in the relational representation core system, which are subsequently reinstated during pattern completion. For instance, fMRI studies have shown that covert retrieval of the context previously associated with an item activated the parahippocampal cortex when probed with the item alone, whereas perirhinal-related representations of the item were activated by presenting the associated context, with the hippocampus coordinating the reinstatement (Diana et al. Reference Diana, Yonelinas and Ranganath2013; Staresina et al. Reference Staresina, Henson, Kriegeskorte and Alink2012; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Yonelinas and Ranganath2013).

Moreover, at the level of memory outputs from the attribution system, familiarity and recollection can interact (Kurilla & Westerman Reference Kurilla and Westerman2008; Reference Kurilla and Westerman2010; Mandler et al. Reference Mandler, Pearlstone and Koopmans1969; Whittlesea Reference Whittlesea and Medin1997). Notably, a feeling of familiarity can trigger an active search in memory to recollect specific details about some event. For instance, when seeing a familiar face in the crowd, one often wishes to remember one's past interactions with that person. Typically, we will elaborate retrieval cues, with the support of the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (i.e., cue specification, Figure 1), trying to specify contextual information associated with the face until we find an appropriate cue that will trigger pattern completion in the hippocampus (Ciaramelli et al. Reference Ciaramelli, Grady and Moscovitch2008). Alternatively, recollection acts as a control over familiarity. For instance, when some aspects of a stimulus feels familiar, remembering that they were actually part of another memory allows us to correctly reject the current stimulus (e.g., recombined pairs in associative memory tasks, exclusion trials in the Process Dissociation Procedure).

Also, expectancies induced by the task characteristics can shift the balance between recollection and familiarity as outputs. For instance, some materials such as pictures induce high expectations in terms of memorability compared to other kinds of materials (i.e., the distinctiveness heuristic). In this case, participants think that they will recollect many perceptual details. If they do not for a given stimulus, they will consider it is new even if they experience fluency feelings. As recollection was anticipated but not familiarity, fluency cues are disregarded because of the absence of recollection (Dodson & Schacter Reference Dodson and Schacter2001; Ghetti Reference Ghetti2003).

Finally, the individual may set specific goals for a given memory situation, that will generate a retrieval mode orientating attention towards the search for particular types of information. This will rely on the interaction between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and dorsal parietal cortex (Cabeza et al. Reference Cabeza, Ciaramelli, Olson and Moscovitch2008; Lepage et al. Reference Lepage, Ghaffar, Nyberg and Tulving2000). For instance, an individual may favor global processing of information leading to familiarity versus analytic processing leading to recollection of details (Whittlesea & Price Reference Whittlesea and Price2001; Willems et al. Reference Willems, Salmon and Van der Linden2008), or may even search for specific types of details (Bodner & Lindsay Reference Bodner and Lindsay2003; Bodner & Richardson-Champion Reference Bodner and Richardson-Champion2007).

5.2. Beyond recollection and familiarity

In the integrative memory model, similarly to models emphasizing the nature of representations used for memory, core systems store specific contents that serve in memory tasks to retrieve the objects, people, actions, settings, and so forth, that have been experienced. But the same representations can also be used to perform other tasks. Indeed, perceptual discrimination between entities with overlapping features and their maintenance in short-term memory have been found to involve the perirhinal/anterolateral entorhinal cortex (Barense et al. Reference Barense, Warren, Bussey, Saksida, Husain and Schott2016; Graham et al. Reference Graham, Barense and Lee2010). Naming and conceptual discrimination of such entities also rely on perirhinal integrity (Clarke & Tyler Reference Clarke and Tyler2015). Similarly, the hippocampus uses relational representations in navigation, short-term memory, perceptual discrimination, imagination, and so forth (Clark & Maguire Reference Clark and Maguire2016; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Yeung and Barense2012; Yonelinas Reference Yonelinas2013). Hence, even if recollection and familiarity recruit relational and entity representations, they are not the only functions to do so. This has implications for the pattern of deficits arising from damage to these core systems (see sect. 6.1).

Actually, the whole architecture described in the integrative memory model may not be uniquely mnemonic in nature. For instance, the interaction between fluent processing of repeated items in the entity representation core system and the attribution system may lead to affective judgments. This is well illustrated by the mere repetition effect in which repeated items are judged more pleasant and prefered over non-repeated items (Willems et al. Reference Willems, van der Linden and Bastin2007). Moreover, the default network, that overlaps partly with the relational representation core system, self-reference system, posterior cingulate gyrus hub of connectivity, ventral parietal cortex, and regions from the attribution system involved in metacognition, is also recruited during imagination of future events, mind wandering, and reflection about one's and others’ mental states (Andrews-Hanna et al. Reference Andrews-Hanna, Reidler, Sepulcre, Poulin and Buckner2010). This network may have an adaptive role by which the brain uses past experiences to simulate possible future scenarios in order to prepare humans to react to upcoming events (Buckner et al. Reference Buckner, Andrews-Hanna and Schacter2008). Additionally, the combined use of the default network and the frontoparietal network (corresponding to interacting core and attribution systems here) supports creative thinking (Madore et al. Reference Madore, Thakral, Beaty, Addis and Schacter2019). Thus, the core systems provide the building blocks that are reconstructed and recombined, depending on the individual's goals, with the help of the attribution system.

The very facts that consistent impairments are observed following brain damage and that the same brain regions are activated when different individuals perform a given task, suggest that the neural networks underlying cognitive functions are common to all individuals. The purpose of theoretical models, like the integrative memory model and others, is precisely to reveal the universal neurocognitive architecture of memory. Beyond anatomical similarity of memory functioning, one may wonder about the social role of such organization. Regarding memory, it appears that, when individuals recall a given event (e.g., a TV show episode) with their own words, the pattern of cerebral activation is more similar between people recalling the same event than between recall and actual perception (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Leong, Honey, Yong, Norman and Hasson2017). This suggests that perceived events are transformed when entering memory in a systematic way that is shared across humans. If true, this would mean that the main purpose of our memory-related neurocognitive scafolding is not only to allow each individual to remember the events that he or she experienced, but more widely to communicate and share beliefs about the past with other people (Mahr & Csibra Reference Mahr and Csibra2018) and to facilitate the creation of collective memories that build the social identity of human groups (Halbwachs Reference Halbwachs1980; Hirst et al. Reference Hirst, Yamashiro and Coman2018).

5.3. Novelty of the integrative memory model compared to other current models of recollection and familiarity

As indicated by its name, the integrative memory model does not have the ambition to propose a novel framework, but rather to integrate some principles from currently most-influential theories. There are therefore a lot of similarities with existing models, although some differences exist. The integrative memory model borrows from representational models the idea that memory processes arise from the use of particular types of representations. The entity representation core system relies on hypotheses from the representational hierarchical view (Cowell et al. Reference Cowell, Bussey and Saksida2006; Reference Cowell, Bussey and Saksida2010; Saksida & Bussey Reference Saksida and Bussey2010) and the emergent memory account (Graham et al. Reference Graham, Barense and Lee2010). Like the emergent memory account, we consider that memory emerges from hierarchically organized representations distributed throughout the brain. The consequence of this is that familiarity can arise from the reactivation of any of these representations (including outside the MTL). In turn, the relational representation core system builds on relational theories about the role of the hippocampus, by suggesting that the hippocampus flexibly binds disparate pieces of information (Aggleton & Brown Reference Aggleton and Brown1999; Eichenbaum & Cohen Reference Eichenbaum and Cohen2014; Eichenbaum et al. Reference Eichenbaum, Yonelinas and Ranganath2007). However, our view departs slightly from another representation-based model, Binding of Item and Context (Diana et al. Reference Diana, Yonelinas and Ranganath2007; Ranganath Reference Ranganath2010), which posits that the perirhinal cortex supports familiarity for items in general, whereas recollection will rely on context representation in the parahippocampal cortex and item-context binding in the hippocampus. We instead propose that the perirhinal cortex is specifically tuned for the representation of complex conjunctive entities, but not items of lower levels of complexity. Moreover, the context representation core system can support familiarity for scene and buildings.

Contrary to process-based models, the integrative memory model does not localize the recollection and familiarity processes themselves to certain regions, but conceptualizes them as processes emerging from the interaction between specific kinds of representation and attribution mechanisms. However, in line with process models like the convergence, recollection, and familiarity theory and the complementary learning systems (Montaldi & Mayes Reference Montaldi and Mayes2010; Norman & O'Reilly Reference Norman and O'Reilly2003), we consider that the core systems have unique computational properties (e.g., entity versus relational pattern separation) that contribute to shaping the content of stored information. The combination of computational properties and the associated representations makes the relational and entity representation core systems more tuned to recollection and familiarity, respectively. But the ultimate memory output will depend on attribution mechanisms.

The network organization of the integrative memory model clearly resonates with the posterior medial anterior temporal (PMAT) framework (Ranganath & Ritchey Reference Ranganath and Ritchey2012; Ritchey et al. Reference Ritchey, Libby, Ranganath, O'Mara and Tsanov2015), but here we separate the network into several subsystems rather than in two systems. The two views share the idea that this neurocognitive architecture not only supports episodic memory, but also other functions like perception, navigation, and semantic processing. In the PMAT framework, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex is a site of convergence between prefrontal and MTL components of the anterior temporal and posterior medial systems. This region would provide the value of item and bound representations, and exercise some control over the representations – notably, to select the relevant content as a function of the situation, and to help with the integration of new information within existing representations. Similar ideas figure in the integrative memory model, notably by suggesting that the self-representation system (involving the orbitofrontal and ventromedial prefrontal cortex) interacts with the core systems to provide some self-referential tagging, thus modulating the value of the representations in core systems. Close to the idea of control over mnemonic traces, we also include the prefrontal cortex in the attribution system. Although both the PMAT framework and the integrative memory model include the retrospenial cortex and posterior cingulate cortex, their role is conceived slightly differently. In the PMAT framework, both the retrosplenial cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex form parts of the posterior medial system that allows individuals to orient in time, space, and situation. In our model, we suggest that the retrosplenial cortex is an integral part of a core system dedicated to storing visuo-spatial and contextual information. In contrast, the posterior cingulate cortex acts as a relay node during cortical reinstatement of the memory trace and, by connecting all systems within the network, including the attribution system, it would contribute to the subjective experience of mentally reliving the episode. This is an original hypothesis of the integrative memory model suggesting a key role of the posterior cingulate gyrus in autonoetic consciousness.

Finally, the articulation of the model around the interaction between core systems and the attribution system is probably the most novel aspect of the integrative memory model. Currently, no recollection/familiarity neurocognitive framework has taken into account the principles from attribution theories. A first proposal relating the fluency heuristic to the perirhinal cortex has however been formulated by Dew and Cabeza (Reference Dew and Cabeza2013). We expand it by suggesting that reactivation of any component of the hierarchically represented item (i.e., object, face, building, word, simple association) will generate a fluency signal which is interpreted by the attribution system in the light of metacognitive knowledge. Similarly, reactivated patterns of complex representations via the hippocampus are also evaluated through the glasses of metacognitive knowledge before being attributed to the past. Because the mapping of attribution processes with cerebral regions is still to be confirmed, a lot remains to be learned about the exact neurocognitive mechanisms involved in the attribution system. For now, we have integrated theories about control mechanisms over memory to propose a mechanistic account of the attribution system. Notably, the attention-to-memory model (Cabeza et al. Reference Cabeza, Ciaramelli, Olson and Moscovitch2008; Reference Cabeza, Ciaramelli and Moscovitch2012; Ciaramelli et al. Reference Ciaramelli, Grady and Moscovitch2008) is key in describing the role of the parietal and prefrontal regions in attention and monitoring mechanisms.

6. The integrative memory model to understand recollection and familiarity deficits

6.1. Damage to core systems versus attribution system