Introduction

There is little doubt that cortisol plays a central role in the onset and course of major depression disorder (MDD) but considerable uncertainty over exactly what that role might be. Diurnal rhythms in cortisol are disturbed in around half the cases of major depression (Sachar et al. Reference Sachar, Hellman, Roffwarg, Halpern, Fukushima and Gallagher1973); there is increased resistance to the feedback action of glucocorticoids on the activity of the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis in a proportion of cases (Carroll et al. Reference Carroll, Martin and Davies1968; Carroll, Reference Carroll1982); the post-awakening surge in cortisol is accentuated in those at risk for MDD (Portella et al. Reference Portella, Harmer, Flint, Cowen and Goodwin2005); prolonged excess corticoids, whether endogenous (as in Cushing's syndrome) or exogenous (therapeutic), may result in depression (Butler & Besser, Reference Butler and Besser1968; Jeffcoate et al. Reference Jeffcoate, Silverstone, Edwards and Besser1979; Lewis & Smith, Reference Lewis and Smith1983); and morning cortisol levels at the higher end of the normal range are a risk factor for subsequent depression (Goodyer et al. Reference Goodyer, Herbert, Tamplin and Altham2000; Harris et al. Reference Harris, Borsanyi, Messari, Stanford, Cleary, Shiers, Brown and Herbert2000). Can we make sense of these disparate findings? Are these changes in cortisol epiphenomena of depression, or do they play a substantial role in the onset, recovery or course of a depressive episode? That is, are they cause or effect? Indeed, should assessment of cortisol play any part in routine clinical management of MDD? Could this be used either diagnostically or therapeutically?

The true meaning of the role of cortisol is only apparent in the context of a schema for the development of MDD. This schema is limited by uncertainties over the definition of MDD, which will remain as long as symptoms are the only means to define it, by doubts about the validity of the psychological concepts used to describe risk patterns, by a lack of physiological attributes of MDD, and by difficulties of combining measures from very different disciplines into a coherent account of the trajectories that lead to MDD. Any schema is therefore certainly incomplete and probably inaccurate. Nevertheless, we need to see how far we can fit cortisol into one. In this review, we address the following questions:

(1) Could information about cortisol levels and their daily variation guide improved understanding of subtypes of MDD and yield additional indicators for optimal treatment?

(2) Could restoration of disturbed cortisol rhythms and/or cortisol receptor blockade form part of the treatment of different forms of MDD?

(3) Could manipulation of cortisol in those at increased risk of MDD form part of a preventive strategy?

Several principles underlie the role of cortisol: (i) there are a number of predisposing factors (including cortisol) for subsequent MDD, and these interact; (ii) these factors may well exert their influence throughout the lifespan; (iii) the way each factor operates, and the influence that it has, will change at different stages of the lifespan; (iv) the effect(s) of each factor will depend not only on their contemporaneous interaction but also on events that have (or have not) occurred previously; and (v) the response of the brain to agents such as cortisol (but also to environmental events) will change with age. Thus there is a chain of probabilistic events that, in sequence, increase or decrease the likelihood of MDD. How are these influenced by cortisol?

Cortisol rhythms and MDD

Alterations in the diurnal rhythms of cortisol are well known to occur in some cases of MDD. About 50% of patients with MDD show elevated evening levels (Claustrat et al. Reference Claustrat, Chazot, Brun, Jordan and Sassolas1984; O'Brien et al. Reference O'Brien, Lloyd, McKeith, Gholkar and Ferrier2004) related to increased pulsatile release of cortisol (Deuschle et al. Reference Deuschle, Schweiger, Weber, Gotthardt, Korner, Schmider, Standhardt, Lammers and Heuser1997). Not all reports agree on this: exceptions include elevated morning cortisol or no change at all (Bridges & Jones, Reference Bridges and Jones1966; Koenigsberg et al. Reference Koenigsberg, Teicher, Mitropoulou, Navalta, New, Trestman and Siever2004). Efforts to relate variations in the clinical symptoms of MDD to cortisol rhythms have not been very successful (Veen et al. Reference Veen, van Vliet, DeRijk, Giltay, van Pelt and Zitman2010; Vreeburg et al. Reference Vreeburg, Hartman, Hoogendijk, van Dyck, Zitman, Ormel and Penninx2010). Depressive symptoms even in very young children are also associated with increased HPA activity (Luby et al. Reference Luby, Heffelfinger, Mrakotsky, Brown, Hessler and Spitznagel2003). Adrenal gland volumes may be increased (Rubin et al. Reference Rubin, Phillips, Sadow and McCracken1995). It is not clear whether these reflect different types of depression or different samples. If we are to assess these changes, we need to consider the implications of altered cortisol rhythms.

Cortisol is secreted as a series of ultradian pulses (shorter than a day, but longer than an hour), and these vary in amplitude and frequency. Altered pulses underlie both diurnal rhythms in cortisol, which are very prominent, and the reaction to stressful events (Lightman & Conway-Campbell, Reference Lightman and Conway-Campbell2010) (Fig. 1). Defining the precise nature of altered cortisol is not straightforward. For example, higher cortisol in the morning will increase the overall (mean) daily value, but also the amplitude of the diurnal rhythm (if levels later in the day do not alter). Either parameter may have specific consequences for brain function. Either pattern can be altered selectively in other ways; for example, both morning and evening levels can increase proportionately, thus increasing mean exposure but not altering the rhythm. Elevated morning levels may be the consequence of increased pulse amplitude, frequency, or both. Each ultradian pulse can result in a corresponding activation of a set of genes, although whether different frequencies of ultradian pulses result in different patterns of gene activation remains uncertain (Hazra et al. Reference Hazra, DuBois, Almon and Jusko2007; Conway-Campbell et al. Reference Conway-Campbell, Sarabdjitsingh, McKenna, Pooley, Kershaw, Meijer, De Kloet and Lightman2010; McMaster et al. Reference McMaster, Jangani, Sommer, Han, Brass, Beesley, Lu, Berry, Loudon, Donn and Ray2011). Finally, the brain's response may also depend on the duration of altered cortisol: whether hours, days or weeks.

Fig. 1. (a) The entrainment of dependent genes by the circadian clock. The diurnal cortisol rhythm is generated by the ‘clock’ genes of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) acting through the pituitary (adrenocorticotrophic hormone, ACTH) and thence the adrenal cortex. (Left) Rhythmic cortisol secretion entrains ‘clock’ genes in target tissues (including the brain) or (centre) acts directly on corticoid-responsive genes. Other peripheral rhythms (right) are entrained independently of cortisol. (b) Ultradian pulses of cortisol underlying the circadian cortisol rhythm in control (Con) and depressed (MDD) subjects (from Young et al. Reference Young, Carlson and Brown2001). (c) The shape of the daily rhythm as it appears from four samples per day. Samples from older depressed subjects have blunted afternoon and evening nadirs compared to controls. * Indicates significant difference between controls (Con) and those with depression (MDD) (Drawn from data in O'Brien et al. Reference O'Brien, Lloyd, McKeith, Gholkar and Ferrier2004.)

Cortisol as a driver of the circadian system

Cortisol is not only part of the circadian system; it also helps to organize it. There is a more general disturbance in circadian physiology in MDD, including sleep and body temperature rhythms (von Zerssen et al. Reference von Zerssen, Barthelmes, Dirlich, Doerr, Emrich, von Lindern, Lund and Pirke1985; Wirz-Justice, Reference Wirz-Justice2006). Early awakening and altered temperature and melatonin cycles occur in MDD; in recovered patients, they resume a more normal pattern (Hasler et al. Reference Hasler, Buysse, Kupfer and Germain2010). The hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) generates the circadian rhythm through interplay between the phasic expression of several genes, including per1 and per2, bmal1, cry and clock, which are synchronized to the 24-h light–dark cycle by signals from the eyes (Hastings et al. Reference Hastings, Maywood and Reddy2008). Other tissues, including parts of the brain (e.g. the hippocampus), also express these ‘clock’ genes. Some, but not all, of these are synchronized by the daily corticoid rhythm (Maywood et al. Reference Maywood, O'Neill, Wong, Reddy and Hastings2006, Reference Maywood, O'Neill, Reddy, Chesham, Prosser, Kyriacou, Godinho, Nolan and Hastings2007). For example, the phasic expression of per2 in the hippocampus, but not the SCN, is driven by the daily rhythm of corticosterone in rats (Gilhooley et al. Reference Gilhooley, Pinnock and Herbert2011). Other genes, not themselves part of a ‘clock’ mechanism, also respond phasically to corticoids. Thus, disturbances in the corticoid rhythm can have several consequences for gene expression in target organs (including the brain): altered rhythms in dependent clock genes; altered rhythms in genes driven by the daily corticoid rhythm; and desynchronization of those genes that are corticoid dependent from those that are not and that may continue their normal cyclicity (Hasler et al. Reference Hasler, Buysse, Kupfer and Germain2010). Desynchronization and disruption of the normal circadian programme can have behavioural consequences similar to MDD, as in the phenomenon of jetlag, characterized by a lowered sense of well-being, depressed mood and impaired cognitive ability (Srinivasan et al. Reference Srinivasan, Singh, Pandi-Perumal, Brown, Spence and Cardinali2010; Menet & Rosbash, Reference Menet and Rosbash2011).

Cortisol and awakening

For 30–60 min after awakening there is a surge of cortisol secretion (Hucklebridge et al. Reference Hucklebridge, Clow and Evans1998). The awakening response is not itself a rhythmic event because it is linked to wakening, although sleep is part of diurnal rhythmic activity. The significance of the cortisol awakening response (CAR) has been much discussed, and remains unclear (Clow et al. Reference Clow, Thorn, Evans and Hucklebridge2004). This makes any association with MDD difficult to interpret. Moreover, the literature on CAR is not consistent. Poor parenting, a known risk factor for later MDD, is associated with increased CAR (Engert et al. Reference Engert, Efanov, Dedovic, Dagher and Pruessner2011), but lower values were reported in those at high risk for MDD or with subclinical depressive symptoms (Dedovic et al. Reference Dedovic, Engert, Duchesne, Lue, Andrews, Efanov, Beaudry and Pruessner2010). Others report increased CAR both in high-risk subjects and in those with MDD (Bhagwagar et al. Reference Bhagwagar, Hafizi and Cowen2005; Mannie et al. Reference Mannie, Harmer and Cowen2007), and also an association with a history of maternal MDD and low positive emotionality (Dougherty et al. Reference Dougherty, Klein, Olino, Dyson and Rose2009). Claims that the CAR may indicate vulnerability to MDD are limited until its significance is better understood, and its relationship to other genetic, psychological and social measures has been more firmly established.

Cortisol as a risk factor for MDD

Levels of morning cortisol in the higher range of normality are one risk factor for subsequent MDD (Goodyer et al. Reference Goodyer, Herbert, Tamplin and Altham2000; Harris et al. Reference Harris, Borsanyi, Messari, Stanford, Cleary, Shiers, Brown and Herbert2000) and higher cortisol is associated with MDD in cases of myocardial infarction (Otte et al. Reference Otte, Marmar, Pipkin, Moos, Browner and Whooley2004) (Fig. 2). Altered cortisol rhythms may be another (Wichers et al. Reference Wichers, Myin-Germeys, Jacobs, Kenis, Derom, Vlietinck, Delespaul, Mengelers, Peeters, Nicolson and van Os2008). We know from other contexts that excess corticoids can endanger the brain, making it more vulnerable to noxious agents that, in the absence of raised corticoids, would not necessarily be damaging (Masters et al. Reference Masters, Finch and Sapolsky1989; Tombaugh et al. Reference Tombaugh, Yang, Swanson and Sapolsky1992). We can translate this notion to MDD: because we know that adversity (both early in life and more proximally) predisposes to MDD (Parker & Brown, Reference Parker and Brown1982; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Bifulco and Harris1987) (Kendler et al. Reference Kendler, Kuhn and Prescott2004), higher cortisol may potentiate the psychopathological actions of these agents in a similar way (Gubba et al. Reference Gubba, Netherton and Herbert2000). The problem here is a pragmatic one: it has proved very difficult to measure cortisol in the days or weeks following individual life events, and thus predict from this measure whether the probability of subsequent MDD is altered.

Fig. 2. (a) Gender differences in salivary cortisol in non-depressed male (M) and female (F) adolescents (after Netherton et al. Reference Netherton, Goodyer, Tamplin and Herbert2004). (b) Saturation curves for glucocorticoid (GR) and mineralocorticoid receptors (MR), showing that MR is saturated at normal morning (but not evening) cortisol levels, whereas GR is not. This assumes that cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and salivary levels of cortisol are similar (see text). (c) Higher morning cortisol at age 13 in offspring of mothers with postnatal depression (PND), and hence impaired maternal behaviour (from Halligan et al. Reference Halligan, Herbert, Goodyer and Murray2004). (d) Higher morning levels of salivary cortisol in non-depressed adolescents who will develop first-onset major depression disorder (MDD) during a 4-year follow-up (from Goodyer et al. Reference Goodyer, Herbert, Tamplin and Altham2000). * Indicates a significance level of p < 0.05 between the two groups; ** p < 0.01.

Corticoids act on the mineralo- and glucocorticoid receptors (MRs and GRs) and hence downstream genes (Joels & de Kloet, Reference Joels and de Kloet1994). GRs are widely distributed in the brain (including the frontal and cingulate cortices), but particularly highly concentrated in the hippocampus, amygdala and hypothalamus (Rosenfeld et al. Reference Rosenfeld, van Eekelen, Levine and de Kloet1993). MR expression is much more limited to these limbic areas (Reul et al. Reference Reul, Gesing, Droste, Stec, Weber, Bachmann, Bilang-Bleuel, Holsboer and Linthorst2000), but has also been implicated in MDD (Young et al. Reference Young, Lopez, Murphy-Weinberg, Watson and Akil2003). Which area, or receptor type, might be involved in the risk represented by altered morning cortisol is not obvious (de Kloet et al. Reference de Kloet, Derijk and Meijer2007), although because MRs are largely saturated by fairly modest levels of cortisol, excess levels are more likely to be sensed by GRs. (Fig. 2). Neither can we easily follow the trail offered by GR- or MR-responsive downstream genes as there are many that possess glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) (Santos et al. Reference Santos, Fairall and Schwabe2011). GREs have a variety of effects on other genes, including chromatin modifications (e.g. deacetylation) and recruitment of co-factors that may moderate glucocorticoid action (Santos et al. Reference Santos, Fairall and Schwabe2011). Another complication is that some genes that respond to corticoids, such as brain-derived neurotrophic growth factor (BDNF), do not contain a GRE. Action on them must therefore be indirect. Corticoids also act on membrane-bound receptors (e.g. N-methyl-d-aspartate, NMDA), which may have more direct, non-genomic, actions on neuronal function. Both glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which can respond to corticoids, have been implicated in MDD (Gutierrez-Mecinas et al. Reference Gutierrez-Mecinas, Trollope, Collins, Morfett, Hesketh, Kersante and Reul2011).

The paragraphs above presuppose that we know what is meant by an ‘optimal’ level of cortisol but, in truth, this is far from clear (Herbert et al. Reference Herbert, Goodyer, Grossman, Hastings, de Kloet, Lightman, Lupien, Roozendaal and Seckl2006). ‘Normal range’ values may simply reflect individual variations in requirements for cortisol. Optimal levels vary even within an individual according to circumstance: Addisonian patients need different amounts of corticoids and are required to increase their dose if they become ill (Reisch & Arlt, Reference Reisch and Arlt2009). We can suppose, therefore, that there are individual optimal ranges for cortisol, whether defined in absolute terms or as the shape or amplitude of the daily cortisol rhythm. These may vary both between and within individuals according to current circumstances. What determines this optimal range is currently unknown, but deviations from it may predispose the individual to the psychopathological effects discussed here.

Cortisol as a reflection of the interaction between genes and environment

What determines individual differences in cortisol levels? The limited studies on monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twins suggest that genetic factors account for 50–60% of the variance (Hainer et al. Reference Hainer, Kunesova, Stunkard, Parizkova, Stich, Mikulova and Starka2001; Ouellet-Morin et al. Reference Ouellet-Morin, Boivin, Dionne, Lupien, Arseneault, Barr, Perusse and Tremblay2008). The identities of the genes responsible are mostly unknown, although variants in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter (hSERT, 5HTTLPR, SLC6A4) may contribute (‘s’ variants have higher levels) (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Joormann, Hallmayer and Gotlib2009; Goodyer et al. Reference Goodyer, Bacon, Ban, Croudace and Herbert2009). The same gene is held to accentuate reactions to adverse life events (Caspi et al. Reference Caspi, Sugden, Moffitt, Taylor, Craig, Harrington, McClay, Mill, Martin, Braithwaite and Poulton2003), which may, in turn, alter cortisol. Gender is another factor: both female rats and humans have higher levels of glucocorticoids (cortisol or corticosterone) than males (Netherton et al. Reference Netherton, Goodyer, Tamplin and Herbert2004; Lightman et al. Reference Lightman, Wiles, Atkinson, Henley, Russell, Leendertz, McKenna, Spiga, Wood and Conway-Campbell2008) (Fig. 2). Oestrogens have a positive action on cortisol and corticosteroid-binding globulin (CBG) levels (Feldman et al. Reference Feldman, Mondon, Horner and Weiser1979; White et al. Reference White, Ozel, Jain and Stanczyk2006), which may account for the fact that this sex difference is not observed in prepubertal children (Netherton et al. Reference Netherton, Goodyer, Tamplin and Herbert2004). It is noteworthy that there is a marked excess of MDD in post-pubertal females: do their increased cortisol levels contribute to this gender difference? Early adversity, for example impaired parenting resulting from maternal depression, may have lasting consequences for raised morning cortisol and the risk for MDD in later life (Halligan et al. Reference Halligan, Herbert, Goodyer and Murray2004) (Fig. 2). The effect of early adversity on later cortisol levels might well be moderated by genetic variants in the child, such as the Val66Met polymorphism in BDNF (Kaufman et al. Reference Kaufman, Yang, Douglas-Palumberi, Grasso, Lipschitz, Houshyar, Krystal and Gelernter2006), although this has not yet been determined.

Early adversity can also accentuate the HPA response in later life to demand or ‘stress’ (Engert et al. Reference Engert, Efanov, Dedovic, Duchesne, Dagher and Pruessner2010; van der Vegt et al. Reference van der Vegt, van der Ende, Huizink, Verhulst and Tiemeier2010; Hunter et al. Reference Hunter, Minnis and Wilson2011). Additional cortisol may itself represent an added risk for a psychopathological outcome; or cortisol may be simply a proxy for, or indicator of, accentuated stress responses, contributing nothing to the psychological outcome of those events. The evidence strongly points to the first proposition. As mentioned previously, Cushing's disease or prolonged corticosteroid therapy is known to induce MDD, but also mania (Starkman et al. Reference Starkman, Schteingart and Schork1981). Corticosterone accentuates the impact of fear-inducing stimuli in experimental animals (Roozendaal et al. Reference Roozendaal, McEwen and Chattarji2009; Zamudio et al. Reference Zamudio, Quevedo-Corona, Garces and De La Cruz2009), and short-term administration to humans males has a similar effect (Merz et al. Reference Merz, Tabbert, Schweckendiek, Klucken, Vaitl, Stark and Wolf2010) (although we should bear in mind the possible differences on behaviour of long- or short-term raised cortisol, discussed later).

Glucocorticoid feedback and depression

Increased resistance of the HPA axis to the feedback effect of dexamethasone (dexamethasone suppression test, DST) on blood cortisol levels in some cases of MDD was reported 40 years ago (Carroll, Reference Carroll1982, Reference Carroll1986). The high hopes that this might evolve into a laboratory test for MDD have not been realized. Neither has the DST given much insight into the derangement of the HPA axis in MDD. Various modifications, such as measuring the cortisol response to corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF) following suppression by dexamethasone, have not improved the situation markedly, although there have been contrary claims (Holsboer et al. Reference Holsboer, Grasser, Friess and Wiedemann1994). Dexamethasone is a ‘pure’ glucocorticoid (i.e. it has little action on MR) but there are several problems with the DST. It is not specific for MDD (even if the latter is a single disease); for example, food restriction induces a positive DST (Mullen et al. Reference Mullen, Linsell and Parker1986), and only a proportion of MDD cases qualify as non-suppressors (the definition is an arbitrary one) (Brown & Shuey, Reference Brown and Shuey1980). There have also been claims that the DST differentiates different types of MDD (e.g. ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ depression) (Schlesser et al. Reference Schlesser, Winokur and Sherman1980) but this has not been established. Dexamethasone penetrates the blood–brain barrier rather poorly, and is exported by the P-glycoprotein transporter (Uchida et al. Reference Uchida, Ohtsuki, Kamiie and Terasaki2011). Thus the physiological information offered by the DST is unclear. The simple notion that it indicates a high drive state of the HPA axis is not convincing because correlations between the DST and basal levels of cortisol are not consistent (Asnis et al. Reference Asnis, Halbreich, Nathan, Ostrow, Novacenko, Endicott and Sachar1982; Pfohl et al. Reference Pfohl, Sherman, Schlechte and Stone1985; Kathol et al. Reference Kathol, Jaeckle, Lopez and Meller1989; Rush et al. Reference Rush, Giles, Schlesser, Orsulak, Parker, Weissenburger, Crowley, Khatami and Vasavada1996).

Cortisol as a moderator of response to treatment

Elevated cortisol in MDD suggests that blocking GRs (e.g. with mifepristone) might be useful. Some report rapid resolution of symptoms (Belanoff et al. Reference Belanoff, Flores, Kalezhan, Sund and Schatzberg2001; Flores et al. Reference Flores, Kenna, Keller, Solvason and Schatzberg2006), others less dramatic results (Simpson et al. Reference Simpson, El Sheshai, Loza, Kingsbury, Fayek, Rady and Fawzy2005). There has been little attempt to relate response to this treatment with prevailing differences in cortisol secretion, or to consider whether a time-dependent use of drugs such as mifepristone might be required in some cases (for example, to restore the normal cortisol rhythm and sensitize patients to antidepressants). It should be noted that mifepristone also antagonizes progesterone receptors. Of note, a case of Cushing's-induced psychosis responded to mifepristone (Chu et al. Reference Chu, Matthias, Belanoff, Schatzberg, Hoffman and Feldman2001), supporting the notion that corticoid-dependent forms of MDD might respond to GR blockade. Clearly much more information on the contribution of GR antagonists to the treatment of MDD is required; a simple overall blockade might not be the optimal approach in some cases of established MDD (e.g. those with disordered rhythms). There are reports of improved mood in MDD subjects after either a cortisol infusion (Goodwin et al. Reference Goodwin, Muir, Seckl, Bennie, Carroll, Dick and Fink1992) or dexamethasone in a dose that would suppress elevated cortisol (Dinan et al. Reference Dinan, Lavelle, Cooney, Burnett, Scott, Dash, Thakore and Berti1997). Can these results be reinterpreted in the light of the more complex ideas about variations in cortisol in MDD set out above? Behavioural approaches to treatment (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy, CBT) might also be sensitive to either endogenous patterns of cortisol or imposed alterations in corticoid activity: this avenue should no longer be ignored.

Disordered corticoids may contribute to the ineffectiveness of antidepressant treatment. This is illustrated by the action of glucocorticoids on the hippocampus. The granule neurons of the dentate gyrus, the major input zone to the hippocampus from the entorhinal cortex and the site of adult neurogenesis, project to the large pyramidal cells of layer CA3 in the ‘cortical’ hippocampus; these, in turn, project, through the Shaffer collaterals, to the pyramidal cells of CA1 (Fig. 3). There is a complex non-uniform pattern of gene expression throughout CA1 (Dong et al. Reference Dong, Swanson, Chen, Fanselow and Toga2009). Different parts of the hippocampus may be involved in many neural disorders, including MDD (Small et al. Reference Small, Schobel, Buxton, Witter and Barnes2011). Because the hippocampus expresses very high concentrations of both GRs and MRs (de Kloet et al. Reference de Kloet, Van Acker, Sibug, Oitzl, Meijer, Rahmouni and de Jong2000), and is highly sensitive to glucocorticoids, it is essential to consider the consequences of altered cortisol on its structure and function and how they might relate to MDD.

Fig. 3. (a) Neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. The darker cells in the inner layer of the dentate gyrus are dividing progenitor cells. (b) In situ hybridizations showing high levels of brain-derived neurotrophic growth factor (BDNF) and tropomyosin-related kinase B (TrkB) receptor mRNAs in the hippocampus of the rat (from Pinnock et al. Reference Pinnock, Blake, Platt and Herbert2010). (c) Adrenalectomy (ADX) increases the number of dividing progenitor cells in the dentate gyrus whereas excess cortisocosterone (Cort) suppresses it. OIL injected animals are controls. (d) Fluoxetine (Flx) increases progenitor cell division (mitosis) in control rats, but not those in which the daily cortisoterone rhythm has been clamped by subcutaneous implant of a pellet of corticosterone (from Huang & Herbert, Reference Huang and Herbert2006). * Indicates a significance level of p < 0.05 between the two groups; ** p < 0.01.

The formation of new neurons (neurogenesis) in the hippocampus of adult rats is exceedingly sensitive to corticosterone. Giving rats excess corticosterone markedly reduces the mitosis rates of hippocampal progenitor cells and the survival of newly formed neurons (Wong & Herbert, Reference Wong and Herbert2004, Reference Wong and Herbert2006) (Fig. 3). Hippocampal neurogenesis also occurs in man (Eriksson et al. Reference Eriksson, Perfilieva, Bjork-Eriksson, Alborn, Nordborg, Peterson and Gage1998), although it is not known whether it is moderated by cortisol. Serotonin-acting drugs, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs, e.g. fluoxetine) increase progenitor mitosis rates in rats, although only after about 14 days of continuous treatment, and may act on the GR (Malberg et al. Reference Malberg, Eisch, Nestler and Duman2000; Anacker et al. Reference Anacker, Zunszain, Cattaneo, Carvalho, Garabedian, Thuret, Price and Pariante2011). It is this fact, together with reports that some of the behavioural actions of SSRIs are prevented if increased neurogenesis is also blocked, that has encouraged the idea that altered hippocampal neurogenesis is in some way related to either the onset of depression or the therapeutic action of antidepressant drugs (Duman et al. Reference Duman, Malberg and Thome1999; Malberg, Reference Malberg2004). Flattening the daily corticosterone rhythm in rats prevents fluoxetine from stimulating progenitor mitosis, an effect that can be reconstituted by adding a daily injection of corticosterone, thus reinstating the daily rhythm (Huang & Herbert, Reference Huang and Herbert2006; Pinnock et al. Reference Pinnock, Balendra, Chan, Hunt, Turner-Stokes and Herbert2007) (Fig. 3). A considerable proportion of depressed subjects do not respond to antidepressant drugs such as fluoxetine (around 40% in some reports) (Birkenhager et al. Reference Birkenhager, van den Broek, Moleman and Bruijn2006). We do not know whether non-response is related to distorted daily cortisol rhythms, or whether restitution of these rhythms (for example by administration in the morning of a low dose of cortisol) might assist pharmacological responsiveness. Such investigations might be highly informative.

Neurogenesis is not the only way that excess glucocorticoids can alter the adult hippocampus. Repeated stress results in atrophy of the apical dendrites of CA1 neurons (Watanabe et al. Reference Watanabe, Gould and McEwen1992), a result replicated by excess corticosterone in both intact rats and tissue culture (Magarinos & McEwen, Reference Magarinos and McEwen1995; Alfarez et al. Reference Alfarez, De Simoni, Velzing, Bracey, Joels, Edwards and Krugers2009). Both GR blockade and inhibition or knockdown of the NMDA receptor prevents this, by an action on CA3 and on CA1 (Christian et al. Reference Christian, Miracle, Wellman and Nakazawa2010). It seems clear that the whole of the three-neuron hippocampal circuit is extremely sensitive to corticoids. How this translates into an improved understanding of MDD is considered in the following sections.

Cortisol interactions with CRF

Any discussion of the HPA axis cannot ignore the role of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF). Like other peptides, its name underestimates its function, which is to coordinate an adaptive response to stress that includes not only endocrine but also autonomic and behavioural responses (Mayer & Baldi, Reference Mayer and Baldi1991; Herbert, Reference Herbert1993). CRF drives the HPA system (in association with other factors, including arginine vasopressin, AVP) and also responds to alterations in cortisol. This response may differ according to region: corticoids suppress hypothalamic CRF but increase levels in the amygdala (Schulkin, Reference Schulkin2011). Because the amygdala is involved in fear and anxiety reactions, this is of particular interest. Experimentally, CRF increases anxiety (Britton et al. Reference Britton, Koob, Rivier and Vale1982). There are reports of elevated CRF levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of depressed subjects (Arborelius et al. Reference Arborelius, Owens, Plotsky and Nemeroff1999). Although there are those who would ascribe depression itself to CRF (Binder & Nemeroff, Reference Binder and Nemeroff2010), it seems more likely that CRF is related either to co-morbid anxiety, a frequent occurrence in MDD, or to the disordered HPA axis described earlier.

Nevertheless, increased attention should be given to the possibility that altered CRF or its receptors, particularly in the amygdala, may interact with cortisol during episodes of MDD and other stress-related illnesses, or during the run-in to the onset of an episode following an adverse life event (Bao & Swaab, Reference Bao and Swaab2010), and play a role in either disordered cortisol secretion or the development of associated anxiety states. The clinical problem is that direct methods of measuring changes in CRF (unlike cortisol) are not available at present. Genetic variants in its receptor have been studied in the context of MDD without much success (Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Collishaw, Harold, Rice and Thapar2011) and, so far, attempts to develop new drugs for either depression or (more plausibly) anxiety disorders based on CRF have also not been very successful (Steckler, Reference Steckler2010).

Cortisol as a regulator of BDNF

There are numerous growth factors known in the brain, but it is BDNF that has been targeted as playing a special role in MDD. The evidence, still highly incomplete, comes from several sources. The basic assumption is that either MDD is caused by maladaptive plasticity in the brain, or antidepressants act by allowing renewed plasticity that, in some way, restores normal function (Castren & Rantamaki, Reference Castren and Rantamaki2010). Exactly where this occurs, or how it might account for MDD, has not been specified, although the hippocampus is an obvious target: it has high concentrations of both BDNF and its principal receptor, tropomyosin-related kinase B (TrkB) (Fig. 3). BDNF is reduced in the brains of suicide victims, and drugs such as SSRIs increase levels in the hippocampus of both humans and rats (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Dowlatshahi, MacQueen, Wang and Young2001; Karege et al. Reference Karege, Bondolfi, Gervasoni, Schwald, Aubry and Bertschy2005). It is said that BDNF is crucial for the behavioural actions of antidepressants in experimental animals (Shirayama et al. Reference Shirayama, Chen, Nakagawa, Russell and Duman2002) but the current experimental ‘models’ of MDD lack convincing face and construct validity (discussed later). Nevertheless, only chronic treatments with SSRIs increase BDNF expression, consistent with the time-frame of the therapeutic response. Fluoxetine also increases plasticity in other parts of the central nervous system (CNS), such as the visual system (Maya Vetencourt et al. Reference Maya Vetencourt, Sale, Viegi, Baroncelli, De Pasquale, O'Leary, Castren and Maffei2008), supporting the notion that this may be a mode of its action in MDD. BDNF is certainly crucial for the stimulating actions of fluoxetine on hippocampal neurogenesis and on the longer-term survival of new neurons (Sairanen et al. Reference Sairanen, Lucas, Ernfors, Castren and Castren2005; Pinnock et al. Reference Pinnock, Blake, Platt and Herbert2010).

Glucocorticoids have powerful effects on BDNF and on plasticity (Blugeot et al. Reference Blugeot, Rivat, Bouvier, Molet, Mouchard, Zeau, Bernard, Benoliel and Becker2011; Liston & Gan, Reference Liston and Gan2011). Corticosterone reduces BDNF mRNA expression in the rat's hippocampus (Schaaf et al. Reference Schaaf, de Jong, de Kloet and Vreugdenhil1998; Prickaerts et al. Reference Prickaerts, van den Hove, Fierens, Kia, Lenaerts and Steckler2006). The stimulating action of SSRIs such as fluoxetine is prevented by excess corticosterone, probably because of inhibition of BDNF expression (Kunugi et al. Reference Kunugi, Hori, Adachi and Numakawa2010; Pinnock et al. Reference Pinnock, Blake, Platt and Herbert2010). Corticoids also repress the activity of TrkB (i.e. BDNF) receptors (Schaaf et al. Reference Schaaf, Hoetelmans, de Kloet and Vreugdenhil1997; Roskoden et al. Reference Roskoden, Otten and Schwegler2004; Stranahan et al. Reference Stranahan, Arumugam and Mattson2011), thus accentuating and complicating their control of BDNF function.

There is a common polymorphism in the human BDNF gene (Val66Met): about 30% of humans carry at least one copy of the Met allele. This alters the rate of secretion of pro-BDNF and BDNF. Because the two peptides act largely on different receptors (p75 and TrkB respectively), this would be expected to influence the way BDNF regulates neural function. Met carriers have smaller hippocampi and poorer episodic memory (Egan et al. Reference Egan, Kojima, Callicott, Goldberg, Kolachana, Bertolino, Zaitsev, Gold, Goldman, Dean, Lu and Weinberger2003). Attempts to relate this polymorphism to risk for MDD have been inconsistent (Verhagen et al. Reference Verhagen, van der Meij, van Deurzen, Janzing, Arias-Vasquez, Buitelaar and Franke2010). It is now realized that defining the contribution of single gene polymorphisms to complex diseases is more informative if their interactions with specified environmental events (and other genes) are taken into account. The risk of later MDD following early adversity is greatest in those carrying the Met variant of the BDNF Val66Met polymorphisms, but also in association with the ‘s’ allele of hSERT (5HTTLPR) (Kaufman et al. Reference Kaufman, Yang, Douglas-Palumberi, Grasso, Lipschitz, Houshyar, Krystal and Gelernter2006; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Liu, Weidenhammer, Cooksey, McClain, Kim, Aguilera, Abel and Chung2009), although this was not confirmed in adolescents (Nederhof et al. Reference Nederhof, Bouma, Oldehinkel and Ormel2010). They also have smaller hippocampi, prefrontal cortices and amygdalae, and more depressive symptoms (Gatt et al. Reference Gatt, Nemeroff, Dobson-Stone, Paul, Bryant, Schofield, Gordon, Kemp and Williams2009). The Met allele is also associated with MDD following an adverse life event (Bukh et al. Reference Bukh, Bock, Vinberg, Werge, Gether and Vedel Kessing2009). By contrast, the power of morning cortisol to predict later MDD was accentuated in those carrying the Val variant (Goodyer et al. Reference Goodyer, Croudace, Dudbridge, Ban and Herbert2010). To reconcile these reports, which are not necessarily contradictory, we need information from a single, large sample on the way that this BDNF variant interacts with early adversity, proximal life events and the diurnal cortisol pattern, and with other common variants (such as hSERT) that are known to influence cortisol levels. Even though the literature is incomplete, the experimental and clinical evidence points to a powerful role for BDNF in MDD, and one that may be strongly influenced by cortisol, although this is still a subject for debate (Groves, Reference Groves2007).

Cortisol as a moderator of the depressogenic actions of the immune system

Glucocorticoids are major controllers of the immune system (Flammer & Rogatsky, Reference Flammer and Rogatsky2011) (Fig. 4). Despite long-standing indicators that the immune system is implicated in MDD, this area remains under-researched. One reason for this is uncertainty about whether peripheral measures of, say, cytokines tell us very much about what might be happening in the CNS. Even if CSF levels could be measured easily, this might not reflect local changes in regions of the brain.

Fig. 4. (a) The two metabolic pathways of tryptophan (kynurenine and hence quinolinic acid, or 5-OH tryptophan and hence serotonin). (b) The reciprocal interactions between cortisol and the immune system. CNS, Central nervous system; IL-1, interleukin-1; IL-6, interleukin-6; TNF-α, tumour necrosis-α; Th2, T-helper 2.

The induction of MDD-like states following treatment with cytokines, such as interferon-α, offered the first clue (Piser, Reference Piser2010). Stress increases neural cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6 (Gadek-Michalska et al. Reference Gadek-Michalska, Bugajski and Bugajski2008; Garcia-Bueno et al. Reference Garcia-Bueno, Caso and Leza2008). Experimental intracerebral infusions of cytokines such as IL-1β or IL-6 induce a syndrome called ‘sickness behaviour’ (Lenczowski et al. Reference Lenczowski, Bluthe, Roth, Rees, Rushforth, van Dam, Tilders, Dantzer, Rothwell and Luheshi1999; Dantzer et al. Reference Dantzer, O'Connor, Freund, Johnson and Kelley2008), which includes social withdrawal, cognitive impairment, anhedonia and increased activity of the HPA axis, a much more convincing ‘model’ for MDD than other more commonly used procedures such as rats struggling in warm water or mice suspended by the tail, the usual experimental methods of assessing ‘depressive’ behaviour (Dantzer, Reference Dantzer2009) (Fig. 4). IL-1β also reduces neurogenesis (Gemma et al. Reference Gemma, Bachstetter, Cole, Fister, Hudson and Bickford2007; Zunszain et al. Reference Zunszain, Anacker, Cattaneo, Choudhury, Musaelyan, Myint, Thuret, Price and Pariante2012). There are persistent reports of elevated cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IL-6 in the blood, and also C-reactive protein, in MDD (Kahl et al. Reference Kahl, Bens, Ziegler, Rudolf, Dibbelt, Kordon and Schweiger2006; Dowlati et al. Reference Dowlati, Herrmann, Swardfager, Liu, Sham, Reim and Lanctot2010; Copeland et al. Reference Copeland, Shanahan, Worthman, Angold and Costello2012), although we need to know how these are reflected in brain levels or function.

Glucocorticoids decrease the expression of tryptophan hydroxylase type 2 (TPH2), the brain isoform of this enzyme (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Flick, Pai, Szalayova, Key, Conley, Deutch, Hutson and Mezey2008) (Fig. 4). This will both reduce serotonin and increase the activity of the alternative tryptophan pathway products (including the production of quinolinic acid, a neurotoxin), through indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (Capuron & Dantzer, Reference Capuron and Dantzer2003). This enzyme is stimulated by cytokines (Maes, Reference Maes2011) and thus encourages the formation of quinolinic acid. Both processes may therefore contribute in parallel to MDD (Oxenkrug, Reference Oxenkrug2010; Dantzer et al. Reference Dantzer, O'Connor, Lawson and Kelley2011; Maes et al. Reference Maes, Leonard, Myint, Kubera and Verkerk2011); antidepressants increase TPH2 (Heydendael & Jacobson, Reference Heydendael and Jacobson2009).

There is a paradox: if corticoids reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines then higher levels should protect against MDD. However, pro-inflammatory cytokines may also interfere with GR activity, which suggests a more complex interaction (Pace & Miller, Reference Pace and Miller2009). Furthermore, the interaction between cortisol and cytokines is two-way: cytokines stimulate HPA activity but cortisol may dampen the pro-inflammatory actions of cytokines. It may be that the balance between these interactions varies, so that in some cases one or other predominates (van der Meer et al. Reference van der Meer, Hermus, Pesman and Sweep1996).

Cortisol moderation by dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)

DHEA and its sulfate (DHEAS) are the most abundant steroids in the blood. Levels rise rapidly at adrenarche (around 8 years) to peak at about 20 years, and then decline progressively with age at individually variable rates (Orentreich et al. Reference Orentreich, Brind, Rizer and Vogelman1984, Reference Orentreich, Brind, Vogelman, Andres and Baldwin1992). DHEA moderates the potency of cortisol on corticoid-sensitive tissues such as the thymus (May et al. Reference May, Holmes, Rogers and Poth1990) and lymphocytes (Blauer et al. Reference Blauer, Poth, Rogers and Bernton1991; Buford & Willoughby, Reference Buford and Willoughby2008); it prevents the suppressive actions of corticosterone on neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus (Karishma & Herbert, Reference Karishma and Herbert2002); and levels have been reported to be lowered during MDD (Goodyer et al. Reference Goodyer, Herbert, Tamplin and Altham2000; Michael et al. Reference Michael, Jenaway, Paykel and Herbert2000) and in other serious illnesses (Beishuizen et al. Reference Beishuizen, Thijs and Vermes2002). If the cortisol/DHEA ratio increases, then a given level of cortisol will gain potency. DHEA enters the CSF in about the same proportion as cortisol, but DHEAS much less, so that the proportion of the two forms in the CSF are not the same as in the blood (Guazzo et al. Reference Guazzo, Kirkpatrick, Goodyer, Shiers and Herbert1996).

The contribution of cortisol to the risk of MDD, its symptoms or progression may not be assessed accurately if current levels of DHEA are not taken into account. Because DHEA has such powerful actions on the immune system (Khorram et al. Reference Khorram, Vu and Yen1997; Buford & Willoughby, Reference Buford and Willoughby2008), whether it moderates cytokine production in the brain, and hence MDD, needs to be assessed. DHEAS was unable to prevent ‘sickness behaviour’ induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Chen & Johnson, Reference Chen and Johnson2004), but there is no other information. We know nothing about the possible role of DHEA in stress reactions during the prenatal period. Cortisol/DHEA ratios are increased in treatment-resistant MDD (Markopoulou et al. Reference Markopoulou, Papadopoulos, Juruena, Poon, Pariante and Cleare2009). DHEA has been tried as an antidepressant therapy with some success (Wolkowitz et al. Reference Wolkowitz, Reus, Keebler, Nelson, Friedland, Brizendine and Roberts1999; Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Daly, Bloch, Smith, Danaceau, St Clair, Murphy, Haq and Rubinow2005; Rabkin et al. Reference Rabkin, McElhiney, Rabkin, McGrath and Ferrando2006), but has not yet been accepted in clinical practice. There is an arguable case that DHEA therapy might be included together with the manipulations of cortisol described elsewhere in this review in future antidepressive therapies or preventive strategies. Cortisol tends to increase with age as DHEA declines (Lupien et al. Reference Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar and Heim2009), so therapy incorporating DHEA may be particularly relevant in older people. DHEA protects hippocampal neurons against the neurotoxic effects of glutamate (Kimonides et al. Reference Kimonides, Khatibi, Svendsen, Sofroniew and Herbert1998), so DHEA treatment might well diminish the risk of age-related neurodegeneration as well (Kohler et al. Reference Kohler, Thomas, Lloyd, Barber, Almeida and O'Brien2010; Franz et al. Reference Franz, O'Brien, Hauger, Mendoza, Panizzon, Prom-Wormley, Eaves, Jacobson, Lyons, Lupien, Hellhammer, Xian and Kremen2011).

Cortisol and the brain

Can we map these various actions of cortisol onto the brain? Because the symptoms of MDD include both emotional and cognitive components, this implicates potentially a considerable part of the brain. Nevertheless, the current evidence points to several brain regions that seem particularly involved in MDD, including various parts of the frontal lobe (orbital, area 25, anterior cingulate), the amygdala, the hippocampus and, perhaps, the habenula, which have established neural connections with each other (Almeida et al. Reference Almeida, Burton, Ferrier, McKeith and O'Brien2003; Pezawas et al. Reference Pezawas, Meyer-Lindenberg, Drabant, Verchinski, Munoz, Kolachana, Egan, Mattay, Hariri and Weinberger2005; Sartorius & Henn, Reference Sartorius and Henn2007; Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Giacobbe, Rizvi, Placenza, Nishikawa, Mayberg and Lozano2011). It seems likely that MDD, even if it is a single disorder (a dubious assumption), represents a disorder of this network, and manipulations (e.g. electrical stimulation) of part of it may restore more normal function in the whole (Mayberg et al. Reference Mayberg, Lozano, Voon, McNeely, Seminowicz, Hamani, Schwalb and Kennedy2005). Can we envisage cortisol acting as a similar nodal factor in part of this network? There are two caveats: the role of cortisol as a risk factor for MDD seems distinct from alterations that are part of the phenomenon of established MDD, as we have seen; and the widespread distribution of GRs within all the areas listed above, in addition to other equally widespread cellular actions such as those on glutamate, discourages such a conclusion. However, it remains plausible that the risk-enhancing actions of cortisol may be dependent upon effects either on a different cellular pathway or on a different part of the network from those during an episode of MDD. Furthermore, individual changes in regional differences in the sensitivity of the brain to corticoids set up, for example, by differential local epigenetic events may play a role in the way that cortisol influences particular cognitive or emotional functions.

Cortisol as a component of a schema for depression

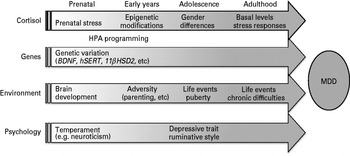

How can the information on cortisol be integrated into an improved understanding of the processes leading to MDD? (Fig. 5). A simple schema for events immediately proximal to an episode of MDD would be: a severe life event occurs; and the response to this is moderated by the subject's temperament (reactivity), current levels of depressive symptoms (including self-esteem) and the cognitive response to the life event, such a ruminative thinking style (McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, Reference McLaughlin and Nolen-Hoeksema2011). These, of course, are not necessarily independent but depend upon antecedent factors. The precipitating event (such as a severe loss) triggers either a progressive process or an iterative one (e.g. ruminative thinking) that is represented by the latent period preceding the onset of MDD (several weeks or months). What these might be or where in the brain they happen is still obscure. Does cortisol play a role in these proximal or more distal events?

Fig. 5. Diagrammatic representation of the role of cortisol in the lifespan trajectories that predispose to the onset of major depression disorder (MDD). Each arrow represents the lifelong (but variable) influence of four major factors determining the risk for MDD. There are mutliple interactions (often bidirectional) between these four factors that vary according to stage of maturation and upon the presence or absence of preceding interactions. These are not shown in the figure but may be inferred, and are discussed in the text. HPA, Hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal.

The process begins prenatally (Fig. 5). Genetic factors play a major part in determining risks for MDD. However, even in the protected environment of the uterus, prenatal events can influence later HPA function in ways that can influence the likelihood of subsequent MDD. The offspring of stressed pregnant rats show heightened corticosterone levels and increased levels of anxiety, fear and HPA responses to stress (Nishi et al. Reference Nishi, Noriko and Kawata2011). This can be replicated by treating dams with corticosterone, and prevented by removal of their adrenals, thus implicating exposure to increased prenatal corticoids (Salomon et al. Reference Salomon, Bejar, Schorer-Apelbaum and Weinstock2011). Similar results follow reduction of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11βHSD2), which acts as a foetal barrier to maternal corticosterone (Seckl & Holmes, Reference Seckl and Holmes2007). Prenatal dexamethasone treatment increases both basal and stress-induced cortisol levels in infant monkeys, and decreases the size of the hippocampus (Uno et al. Reference Uno, Eisele, Sakai, Shelton, Baker, DeJesus and Holden1994). Prenatal corticoids therefore contribute to postnatal behavioural traits (e.g. anxiety) and to HPA activity (‘programming’) in rats, although, as expected, they can be moderated by genetic variations such as those in the serotonin transporter (Belay et al. Reference Belay, Burton, Lovic, Meaney, Sokolowski and Fleming2011). Other components of the HPA axis, including variations in CRF or its receptors, may also play a significant part in shaping the pre- and postnatal brain (Ivy et al. Reference Ivy, Rex, Chen, Dube, Maras, Grigoriadis, Gall, Lynch and Baram2010). Do comparable events occur in humans? There are parallels (O'Regan et al. Reference O'Regan, Welberg, Holmes and Seckl2001) but the evidence is less complete. Although prenatal maternal stress can influence the child's later emotional and cognitive behaviour, whether corticoids are implicated remains unproven (Glover et al. Reference Glover, O'Connor and O'Donnell2010), although the weight of evidence from other species, including primates, makes it likely.

Alterations in corticoid receptor function are as important as those in the agonist (van Rossum & van den Akker, Reference van Rossum and van den Akker2011). It is noteworthy that exonic polymorphisms (single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) in GR and MR and also in the 11βHSD genes are rare, suggesting that they are tightly conserved, unlike, for example, other genes associated with MDD such as hSERT or BDNF. It may be that any change in GR is deleterious (van Rossum et al. Reference van Rossum, Russcher and Lamberts2005), whereas a given variation in hSERT and BDNF may be either disadvantageous or even advantageous according to context (Homberg & Lesch, Reference Homberg and Lesch2011). Variations in other genes that modulate GR function, such as FKBP5, or downstream variations in, for example, transcription factors, may contribute to individual risk (Zimmermann et al. Reference Zimmermann, Bruckl, Nocon, Pfister, Binder, Uhr, Lieb, Moffitt, Caspi, Holsboer and Ising2011). We should also note that the contribution of MR and aldosterone, its principal agonist, to MDD have hardly been studied despite experimental evidence for the importance of MR/GR interactions (Joels & de Kloet, Reference Joels and de Kloet1994; de Kloet et al. Reference de Kloet, Van Acker, Sibug, Oitzl, Meijer, Rahmouni and de Jong2000) and evidence that MR variants may contribute to human emotionality (DeRijk et al. Reference DeRijk, de Kloet, Zitman and van Leeuwen2011).

Poor parenting may alter glucocorticoid-related genes (e.g. GR) in rodents by epigenetic modifications such as methylation (Alikhani-Koopaei et al. Reference Alikhani-Koopaei, Fouladkou, Frey and Frey2004; Meaney & Szyf, Reference Meaney and Szyf2005; Szyf et al. Reference Szyf, Weaver, Champagne, Diorio and Meaney2005; McGowan et al. Reference McGowan, Suderman, Sasaki, Huang, Hallett, Meaney and Szyf2011). Methylation (or acetylation) of DNA alters a gene's expression for prolonged, even lifetime, periods (Fig. 5). Comparisons between rodents and humans must be tempered by the knowledge that rodents are born highly immature (altricial) compared to humans. Hence some of the postnatal processes described in rodents may occur prenatally in man. There was no alteration in GR methylation in the brains of suicide victims (Alt et al. Reference Alt, Turner, Klok, Meijer, Lakke, Derijk and Muller2010); however, methylation of GR in the blood was increased in infants with depressed mothers (Oberlander et al. Reference Oberlander, Weinberg, Papsdorf, Grunau, Misri and Devlin2008). Measuring methylation patterns in blood may not give an accurate representation of those in the CNS (Turner et al. Reference Turner, Alt, Cao, Vernocchi, Trifonova, Battello and Muller2010; Cao-Lei et al. Reference Cao-Lei, Leija, Kumsta, Wust, Meyer, Turner and Muller2011; Wiench et al. Reference Wiench, John, Baek, Johnson, Sung, Escobar, Simmons, Pearce, Biddie, Sabo, Thurman, Stamatoyannopoulos and Hager2011). This area of research is only at its beginning.

The surge of MDD that occurs during adolescence and in subsequent years thus occurs on the back of pre- and postnatal events (Fig. 5), both influenced by cortisol. The contribution of gonadal steroids to the marked sex difference in the incidence of adolescent MDD needs further study. Oestrogens markedly increase total cortisol levels in the blood, but also those of CBG (Qureshi et al. Reference Qureshi, Bahri, Breen, Barnes, Powrie, Thomas and Carroll2007). There is a range of psychological variables that represent risks for MDD. They include: neuroticism, a component of ‘personality’ or ‘temperament’; levels of subclinical depressive symptoms, which includes self-esteem, an appraisal of self-worth or value; and rumination, a cognitive style for dealing with adversity (Goodyer et al. Reference Goodyer, Herbert and Tamplin2003; Nolen-Hoeksema et al. Reference Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco and Lynubomirsky2011). Some are ‘traits’ and have thus been largely established by a variety of genetic and environmental interactions, many of them modulated by cortisol. The occurrence of an adverse life event is held to trigger an episode of MDD in many cases (Brown, Reference Brown1986; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Denniston, Gabrielson, Khan, Khanani and Desai2010). As we have seen, an essential piece missing from the overall puzzle is whether this activates the HPA axis in particular ways that may contribute to the risk of MDD. Because basal (pre-morbid) levels of cortisol are a risk factor, we can conclude that any early agent setting these levels (e.g. poor parenting) will act as a distally derived but proximally active adjuvant for MDD. Thus cortisol, in whatever configuration (absolute levels, diurnal variation, etc.), plays a substantial (but variable) role at all points of the lifetime trajectory that may predispose to MDD. This also applies to the interaction between cortisol and common genetic variants such as those in the serotonin transporter and BDNF.

Is cortisol associated with individual differences in psychological measures? Some report no association between cortisol and temperamental characteristics such as ‘emotionality’ (neuroticism) (Schommer et al. Reference Schommer, Kudielka, Hellhammer and Kirschbaum1999; van Santen et al. Reference van Santen, Vreeburg, Van der Does, Spinhoven, Zitman and Penninx2011). Others find positive associations between neuroticism and current cortisol levels (Nater et al. Reference Nater, Hoppmann and Klumb2010) but these can be in either direction and are not consistent (Gerritsen et al. Reference Gerritsen, Geerlings, Bremmer, Beekman, Deeg, Penninx and Comijs2009). There are positive results for other characteristics, such as internalizing behaviour (Tyrka et al. Reference Tyrka, Kelly, Graber, DeRose, Lee, Warren and Brooks-Gunn2010). Does cortisol affect current mood? Giving an acute dose of cortisol had no effect on mood (Wachtel & de Wit, Reference Wachtel and de Wit2001; Het & Wolf, Reference Het and Wolf2007) but increased negative mood and response to unpleasant pictures, although only after repeated showings (Wirth et al. Reference Wirth, Scherer, Hoks and Abercrombie2011). Cortisol may thus exert its actions on emotions in a situation-dependent manner. However, other studies show that cortisol did not reduce subjective fear responses in a socially demanding situation in normal subjects, but did reduce phobic fear (Soravia et al. Reference Soravia, Heinrichs, Aerni, Maroni, Schelling, Ehlert, Roozendaal and de Quervain2006, Reference Soravia, de Quervain and Heinrichs2009). Increased sensitivity to arousal occurred after neutral (not aversive) stimuli (Abercrombie et al. Reference Abercrombie, Kalin and Davidson2005), but negative mood following the Trier stress test was in fact reduced in healthy volunteers; those prone to develop MDD reacted differently (Het & Wolf, Reference Het and Wolf2007).

The actions of cortisol on the brain may be very rapid (Strelzyk et al. Reference Strelzyk, Hermes, Naumann, Oitzl, Walter, Busch, Richter and Schachinger2012). Many studies have focused on memory, rather than mood. Cortisol decreased verbal (but not non-verbal) memory, without effects on executive function (Newcomer et al. Reference Newcomer, Selke, Melson, Hershey, Craft, Richards and Alderson1999; Wolf et al. Reference Wolf, Convit, McHugh, Kandil, Thorn, De Santi, McEwen and de Leon2001). In subjects with MDD, dexamethasone in fact improved declarative memory (but not in controls) (Bremner et al. Reference Bremner, Vythilingam, Vermetten, Anderson, Newcomer and Charney2004). There is disagreement about whether cortisol enhances memory for emotionally arousing stimuli or for any stimulus irrespective of emotional valence (Buchanan & Lovallo, Reference Buchanan and Lovallo2001; Abercrombie et al. Reference Abercrombie, Kalin, Thurow, Rosenkranz and Davidson2003). Although there is some literature on the relationship between cortisol responses and ruminative style (Young & Nolen-Hoeksema, Reference Young and Nolen-Hoeksema2001; Zoccola et al. Reference Zoccola, Quas and Yim2010), there is no information on whether induced elevations in cortisol can influence that style.

These short-term studies have limited value in the context of MDD because the period of exposure to increased levels is likely to be much more prolonged in the latter. Cushing's disease offers one opportunity to study the results of protracted excess cortisol on psychological processes such as self-esteem or ruminative style. However, nearly all studies compare Cushing's patients with controls, and there is no doubt that the former show affective disturbances (depression) and cognitive deficits (such as impaired emotional recognition) (Langenecker et al. Reference Langenecker, Weisenbach, Giordani, Briceno, Guidotti Breting, Schallmo, Leon, Noll, Zubieta, Schteingart and Starkman2012). Re-examining recovered Cushing's patients in the expectation that they return to a basal, pre-morbid state is vitiated by knowledge that recovery is often incomplete and the effects of hypercortisolaemia are prolonged (Pereira et al. Reference Pereira, Tiemensma and Romijn2010; Tiemensma et al. Reference Tiemensma, Biermasz, Middelkoop, van der Mast, Romijn and Pereira2010). Prednisone therapy is associated with both depressive and antidepressive actions (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Denniston, Gabrielson, Khan, Khanani and Desai2010; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Francisco, Baker, Weisdorf, Forman and Bhatia2011) in addition to impaired cognitive abilities (Brown, Reference Brown2009), but pharmacological differences from cortisol and the presence of an underlying disease render conclusions relevant to MDD difficult.

Three questions about cortisol for psychiatry

What does current knowledge about the role of cortisol in MDD suggest for clinical investigation or application? We need to take into account the multiple interactions between cortisol and other risk factors for MDD, and the way these change as one phenomenon of the disorder itself. Cortisol exerts its influence across two dimensions: a time-related one based on phases of the lifespan that regulate levels of risk, and a more proximal one during the processes leading to the onset and course of an episode of MDD (Fig. 5). Cortisol plays a central role in the genetic contribution to MDD, as one expression of genetic variation, and on the way that environmental events predispose to MDD, as a response to that environment; that is, it plays a pervasive part in both sides of the G × E interaction. It is evident, both from this review and the literature at large, that consideration of the role of cortisol in isolation from other factors known to be concerned with either the risk of MDD or its course is not profitable. We can, however, address the three questions posed at the start of this review:

(1) Careful assessment of cortisol, genes and the symptoms in MDD will help us differentiate distinct categories of this complex disorder, and thus stratify subjects for selective treatment regimes. We should anticipate adequate cortisol measures (saliva, several time points, several days) as part of the routine management of MDD.

(2) Patients with disturbed cortisol rhythms might benefit from restitution of those rhythms; they may be distinct from those with more generally elevated levels, who might benefit from cortisol blockade. Selective manipulations of cortisol, based on adequate assessment of individual cortisol rhythms, should play a role in treatment (in combination with antidepressants or behavioural therapy). DHEA treatment might well play an adjunctive role, particularly in older patients with MDD.

(3) A careful assessment of the contribution of various risk factors for MDD might indicate the effect size of excess cortisol in individual cases as the risk for subsequent MDD. Manipulation of cortisol, its receptors or related molecules (to reduce the action of cortisol on the brain) should be considered as a preventive measure for some of those at very high risk of future MDD in which cortisol plays a significant role, in addition to preventing other cortisol-related consequences such as long-term cognitive decline.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to J. Bancroft, P. Cowen, I. Goodyer, A. Grossman, B. Keverne, S. Lightman and J. Schulkin, and also three anonymous referees, who made many valuable suggestions, nearly all of which I have adopted. I thank the Cambridge Centre for Brain Repair and its chairman, James Fawcett, for its hospitality. My work has been supported principally by grants from the Wellcome Trust and the UK Medical Research Council.

Declaration of Interest

None.