It has become common knowledge by now that the european Union does not have it particularly easy when it comes to democracy. A commensurately difficult task for political science is to analyse the EU in conventional democratic-theoretical categories or to produce generally valid conclusions on the condition and necessity of democracy at the European level. This situation stems from the functional and structural ambivalence of this sui generis political body, the subsequent uncertainty of the criteria to be used for evaluating its democratic quality, the resultant differences in opinion on the appropriate model for democratizing the EU, and the continuing dissent on whether the EU – because of its peculiar nature – can or should be democratized at all. It is precisely this unprecedented character in turn that renders the analysis and assessment of democratic legitimacy in the European Union a difficult, if not hopeless endeavour.Footnote 2

Nonetheless, it would seem evident that politics takes place in the European Communities, that the European Union can be considered a political system and thus a suitable case for study in comparative political science.Footnote 3 Despite this unique political system's frequent classification as sui generis, there is good reason to defy the taboo against subjecting it to comparative analysis. Granted, the EU may be a ‘one-of-a-kind kind of polity’, but then again, all political systems – not unlike people – are in sum unique. Furthermore, even if the EU is not itself a state, it can still be compared with other political systems constituted as states, if for no other reason than that the common or unique (sui generis as it were) aspects of the EU's institutional structure and functioning can only be captured by comparing it with other polities. From the outset, we essentially omit the discussion on the democracy deficit of the EU, taking it as a given, despite the academic and political challenges on this issue and in full awareness of the merits of both sides of the debate.Footnote 4 Nevertheless, we ultimately accept the argument that there is a gap of legitimacy in the EU, rendering inquiry into the possibilities of democratization worthwhile, if not necessary. With this assumption, we attempt in the following analysis to provide answers to two fundamental issues: we will examine which model of government most closely coincides with the European Union, the parliamentary or presidential model, or neither. Building upon that assessment, and in an attempt to catch up on a widely neglected reform option, we explore the opportunities and feasibility of realizing the presidential model as a step towards more democracy in European governance. Admittedly, the multilevel governance system of the European Union could be understood as something altogether different. Still, with regard to inter-institutional relations, separation of powers and linkage between executive and legislative ‘branches’, one should be able to determine some affinity on the part of the EU to a governmental type.

CATEGORIZING THE EUROPEAN SYSTEM OF GOVERNMENT

Based on the dichotomous classification of types of government as parliamentary or presidential, first developed by the British scholar on parliamentarianism, Walter Bagehot,Footnote 5 all political systems can be categorized as one form or the other – including the EU. The core of this typology lies in the relationship between the executive and legislative, that is, the branches that constitute the democratic substance of a governmental system. However, debate abounds on the existence of hybrid forms in addition to the ‘pure’ forms. The extent to which one can identify mixed forms depends on the criteria used.

Typology of Parliamentary vs. Presidential Systems of Government

According to Winfried Steffani,Footnote 6 the typology can be narrowed down to a decisive (single) factor, namely the removability or non-removability of the head of government (the prime minister) for political reasons. Following that approach, the possibility of hybrid systems can be dismissed. If we base the typology on several criteria of equal significance, on the other hand, it becomes possible to identify other types of government in addition to the purely parliamentary and presidential forms.Footnote 7 The intense discussion on possible hybrids was initially triggered by the ‘semi-presidential’ system coined by Maurice Duverger.Footnote 8 This model refers to a system with a parliamentary institutional framework in which there is government headed by a prime minister responsible to parliament, but also a – usually popularly elected – president with governmental powers in addition to the role as head of state. While Steffani sees no reason to remove this type of system from the dualistic typology, a variety of authors argue that it is different enough from the parliamentary form to warrant consideration as a distinct system.Footnote 9

Whatever the case, one must still establish whether it is sufficient to reduce the criteria to the differentiating factor of removability vs. non-removability in order to preclude the possibility of mixed forms. Steffani argues that this criterion essentially implies a certain type of government appointment procedure, rendering the appointment factor secondary in significance. In doing so, however, he overlooks three issues. First, in order to qualify as a presidential system, the president must enter office via democratic means. Thus, the ‘negative’ factor – non-removability of the head of government for political reasons – must be supplemented by a ‘positive’ factor concerning how the president is appointed or selected. Put differently: an absolutist hereditary monarchy, though ‘non-removability’ is given, can hardly be deemed a presidential system. Second, appointment and removability do not necessarily need to coincide with one other. Just as it is possible for a non-removable government to be appointed by parliament (as in Switzerland), it is equally conceivable to have a system with a directly elected head of government still dependent on the confidence of parliament (as in Israel 1996–2001). And third, the criterion of removability vs. non-removability of government for political reasons is indeed much more ambiguous than is often assumed.Footnote 10

All three issues are exemplified in the case of the European Union. Thus, the following seeks to examine how the appointment and removal of the ‘European government’ are addressed and regulated in the treaties and have been made in practice. In order to be able to classify the EU system of government, the secondary criteria of the parliamentary–presidential typology will be consulted. In a further step, the executive structure will be analysed to determine whether the features of the semi-presidential system of government are fulfilled.

Appointing a European ‘Government’

The European Commission exercises the most important executive powers in the Community and can be viewed, analogously at least, as the European government. The European Commission represents a distinctive combination of both administrative and political aspects of the executive.Footnote 11 In the role of administrative agency, the Commission possesses a much greater scope of authority than administrations in national political systems, which raises serious legitimatory concerns. On the other hand, its political competences do not extend nearly as far as those of national governments. Accordingly, the Commission's limited power coincides in turn with its deficient democratic legitimacy.Footnote 12

Until 1994, the Commission president was appointed ‘by common accord’ of the governments of the member states, assembled as the European Council. Since then, this procedure has undergone six changes, all of them geared towards increasing the democratic legitimacy of this office. First, the investiture vote was introduced by the 1992 Maastricht Treaty on European Union (TEU), on account of which the nomination of the European Council for Commission president was reached by common accord after consultation with the European Parliament (EP), and then the Commission as a body was subject to a vote of approval of the EP (formerly Article 158 TEU Maastricht).Footnote 13 At the same time, an additional provision of the treaty adjusted the term of office of the Commission president, which until then lasted four years, to match the five-year legislative period of the EP. Third, the Treaty of Amsterdam amended the European Council's nomination procedure for Commission president by requiring approval by the EP.Footnote 14 Fourth, the Treaty of Nice (2001) set out that the European Council was to nominate a Commission president by qualified majority, rather than by common accord (i.e. unanimity). This rule was applied for the first time with the installation of the Barroso Commission in 2004. Under the Treaty of Lisbon, when nominating the Commission president, the European Council is to ‘take into account’ the results of the EP elections, while the investiture vote has been advanced to a formal ‘election’ of the Commission president by the Parliament (Article 17 (7) TEU).

The provisions of the Lisbon Treaty have not, however, changed the fundamental character of the appointment process. Taking a closer look, it becomes clear that the EP does not have the power to ‘elect’ the Commission, as the procedure is nominally and misleadingly referred to in the treaty, but instead has a power to confirm. The actual power to nominate remains with the heads of state and government of the EU member states.Footnote 15 The previous voting results in the EP, normally a broad, cross-party majority for the Commission president, illustrate the confirmatory character of the EP's role in the appointment procedure.

Of course, the European Council is well advised to consult the European Parliament early on in the nomination process to ensure EP approval, but the influence of the Strasbourg assembly remains far from that of a positive appointment power. For instance, the rejection of France and Germany's preferred candidate for Commission president, the liberal Belgian prime minister Guy Verhofstadt, in favour of the conservative Portuguese candidate José Manuel Barroso in 2004 reflected to a greater extent the changed political party and majority constellation in the European Council (i.e. the parties in power in the member states), as opposed to the results of the EP elections. To pre-empt the Council, the larger political party groups in the EP could have campaigned with top candidates for the office of Commission president, which, perhaps wisely, none of them has attempted in the past. Thus a prerequisite for true parliamentarization of the appointment procedure would be the Europeanization of the EP elections, meaning that the elections revolve around European issues and candidates. Were that the case, the Council and the Parliament could swap their current roles in the appointment procedure; the treaty text would not even have to be amended.

The appointment process does not end with the enthronement of the Commission president, however. After the president assembles the team of commissioners in concurrence with the member state governments, the Commission must be approved as a whole by vote of the Parliament before assuming office (Article 17 (7) TEU). A comparison with other constitutions reveals that a power to confirm the government is reserved to parliaments in several parliamentary systems (as in Finland, Ireland, Sweden and Spain, as well as in Germany at the state or Länder level), although it is more the exception than the rule.Footnote 16 Conversely, confirmatory powers belong to the usual ‘checks and balances’ of a presidential system. Such is the case with the US Senate's ‘advice and consent’ (Article II, 2 (2) US Constitution) required for individual appointments by the president, which grants partial but not unreserved control over the executive. In the EU, on the other hand, the parliamentarians' vote of consent vis-à-vis the Commission as a whole apparently compensates the EP for its lack of a positive power of appointment.

Yet, the failed first attempt at confirming the Barroso Commission clearly showed how awkward this rule is, particularly in light of the Commission president's position in the cabinet-building process. It would only be practicable if the Commission president had genuine latitude in selecting the members for the Commission, as provided for in the draft constitution proposed by the Convention.Footnote 17 In that case, the Commission president could consult the Parliament beforehand, take its preferences into consideration and thus be able to ensure EP support for the Commission. Under the current arrangement, the president's hands are tied by the individual member states. Consequently, the first rejection of a Commission by the EP (October 2004) may have been ostensibly directed at the allegedly unsuitable Commission nominees; the real objects of disapproval were the heads of state and government and their disregard of the EP's preferences.

Government Removability: The Vote of Censure Against the Commission

Justifiably, the EP's rebellion has been interpreted as a sign of more parliamentarianism in Europe. That this comment stems from Hans-Gert Pöttering, at that time the chair of the European People's Party (EPP) group in the Parliament, appears remarkably schizophrenic since it was the Christian democrats and conservatives who promised to support Barroso in the first place. Thus, more parliamentarianism in the EU cannot be equated with a transition to a parliamentary-style system of government. The institutional position of the European Parliament can be viewed more aptly as hermaphroditic, combining features of parliamentary and presidential systems, although the relations between the Parliament and the Commission tend to demonstrate a greater affinity towards the separation of powers intrinsic to presidentialism. The latter is reflected in the rules on the censure vote (Article 234 TFEU).

According to the Lisbon Treaty, the Commission ‘as a body, shall be responsible’ to the European Parliament (Article 17 (8) TEU), signifying at a first glance a parliamentary system. One should reject viewing this provision as equivalent to the normal parliamentary power of removability for two reasons: first, to effect resignation of the Commission, the EP vote of censure must be carried by a two-thirds majority, whereas the absolute majority suffices for the Commission investiture.Footnote 18 Such a disparity between appointment and removability of government is unparalleled among parliamentary democracies. Second – and linked to the first point – the removability of the Commission is not contingent upon ‘political’ reasons, but rather serves as a sanction against the Commission or commissioners for legal or ethical misconduct, as demonstrated by the (failed) motion of censure against the Santer Commission in January 1999.Footnote 19 Moreover, the Parliament has tried in vain to extend its power of censure from the Commission as a whole to individual commissioners.Footnote 20 This likewise attests, if only indirectly, how ‘unparliamentary’ the EP's censure vote is. If this power were based on the political principle of removability, the EP would be capable of effecting individual resignations merely by threatening a vote of no confidence.Footnote 21 In the European Union, the rule depicts a legal principle (disguised as a political procedure) that resembles the American impeachment more than the motion of censureFootnote 22 in the parliamentary governmental sense.

Applying the further (secondary) criteria of the parliamentary vs. presidential typology, we get an even more complete picture. For instance, neither the Commission, nor the Council (Council of Ministers or European Council) has the power to dissolve the European Parliament, which is normally the counterpart to the political removability of the government by parliament in parliamentary systems. While not explicitly prohibited, an additional fit with the presidential system is the (de facto) incompatibility between executive office (in the Council and Commission) and seat in Parliament, although it is not a compelling difference as several parliamentary systems likewise require incompatibility.

With regard to legislative powers, the EU becomes more difficult to categorize.Footnote 23 On the one hand, the Commission has the power of legislative initiative – even a monopoly of initiative in the ‘first pillar’. On the other hand, the Commission possesses a quasi-veto as it can withdraw or amend its proposals at any time in the legislative process, a right that the Commission retains under the Treaty of Lisbon (Article 293 (2) TFEU). All the same, the Commission's right of withdrawal is linked to the EU provision that all regulations, directives and decisions made by the Council and Parliament must originate from proposals by the Commission (Article 289 (1) TFEU). The Commission monopoly of initiative is a rather unparliamentary idiosyncrasy of the EU that arises out of the institutional linkage between supranational and intergovernmental forms of integration. As a result, the Council cannot make decisions, even by unanimity, independent of the Commission. This serves to prevent future governments from being able to downgrade the achieved level of integration via the normal legislative procedure. One may doubt that the EP could pose a similar threat. Granting it the right of initiative, however, would pose the question of how the Commission should be adequately involved in the legislative procedure when the EP initiates;Footnote 24 a superfluous question in a parliamentary system. The lack of legislative initiative will most probably remain one of the deficits that characterize the Strasbourg assembly and distinguish it from ‘normal’, democratic parliaments – on top of the violation of the principle of equality in the distribution of seats (degressive proportionality), the non-uniform electoral procedure or its lower position vis-à-vis the Council.

The Divided European Executive: A Semi-Presidential Arrangement?

Up to now, we have assumed that the governing function in the EU is primarily carried out by the Commission and the legislative function by the various Council formations and the Parliament. Of course, this provides only a limited picture of the complex reality of European governance. Just as the Commission participates in the legislative process, so does the Council serve as an executive institution, both functionally and structurally. That the Lisbon Treaty will extend its executive powers corresponds with the interdependency between supranational and intergovernmental institution-building characteristic of the EU.Footnote 25 The numerous institutional innovations in the Lisbon Treaty include, first, the formal incorporation of the European Council as an EU institution, now charged explicitly with providing the impetus for future development and defining ‘the general political direction and priorities’ of the Community (Article 15 (1) TEU). Second, the office of a president (of the European Council) was established to be elected by the heads of state and government by qualified majority for two-and-a-half years, renewable once (Article 15 (5) TEU). Third, the office of the high representative for foreign affairs and security policy has been upgraded institutionally, though nominally a step down from the foreign minister as previously envisioned by the Constitutional Treaty. According to the ‘double-hat’ arrangement, the high representative will serve as a member of the Commission (as its vice-president), and also as chair of the Foreign Affairs Council (Article 18 TEU), deviating from the principle of the rotating Council presidency.

In general, the double or dual executive represents a typical feature of the parliamentary form of government. While the roles of head of state and government are merged into one office in presidential systems, they remain institutionally separate in parliamentary ones. But the parliamentary systems of South Africa or Botswana – or at the Länder level in Germany – with their unified executives show that exceptions are possible. Conversely, a dual executive in a presidential system is theoretically imaginable. The difference of dual vs. unified executive is thus not born out of a functional necessity for the respective systems, but is rather explicable in historical terms, based more on where and when the systems developed.

Among the systems with a dual executive, the question posed for political scientists is how power is divided between the two institutions. In most parliamentary systems, the head of government tends to be the more powerful, if not de jure, then de facto, while the president (or monarch) is relegated to the symbolic, ceremonial tasks of head of state. In other cases, the president has significant political powers that make this office a part of the government. Determining who the real chief executive is becomes difficult. It can depend on the constitutional provisions and their interpretation in practice, but also on the party-political situation – who is in the majority and where. Exemplary of this semi-presidential type of system is the French Fifth Republic.

The parallels to the EU polity are fairly obvious. In the area of the executive, the responsibility for governing falls both on the Commission and the Council. Aside from the office of the high representative and how it is structured under the Lisbon Treaty, the heads of both executive institutions are institutionally separated. Within this framework there is a series of functional overlaps that are foreign to other political systems with dual executives. For example, the Commission has a strong leadership instrument through its monopoly of legislative initiative, cutting into the role of the European Council as provider of ‘general political direction and priorities’, and is by no means reduced to monitoring and implementing policy.

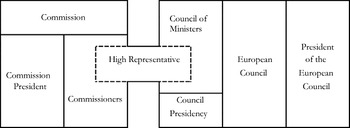

Within the Council, the heads of state and government in turn share leadership with the semi-annually rotating Council presidency. The latter has evolved into an increasingly important agenda-setter whose working programme can make the difference between stagnation and progress in European politics.Footnote 26 If the complexity were not yet high enough, the Treaty of Lisbon bestows executive tasks upon the newly established president of the European Council, rendering the ‘executive branch’ of the EU even more diffuse (as Figure 1 below attempts to illustrate). The president is supposed to promote the cohesion and continuity of the European Council and provide impetus, but also to ensure the representation of the EU in external affairs ‘without prejudice to the powers of the High Representative’ (Article 15 (6) TEU). At the same time, this suggests that the president of the European Council is to grow into the role of a representative head of the European Union that, until now, has been mainly exercised by the Commission president.

Figure 1 The Structure of the EU Executive

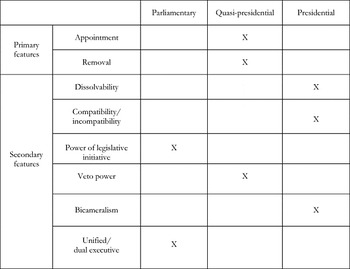

Because the EU – as shown in Figure 1– lacks the central features of a parliamentary system, the analogy should not be overstretched. The comparability is reduced to the distribution of power(s) within the executive, where the Commission and Council or the Commission president and the president of the European Council rival one another. It remains to be seen whether this diffuse structure perpetuated and even intensified by the Treaty of Lisbon will entail additional potential for gridlock and impairment of the EU institutional performance and efficiency.Footnote 27 If such risks are impending, they would most probably be posed by the Council as a whole and less by the newly created offices of the president and high representative. This would be one reason why popular election of the president of the European Council would not bring the EU much further, either politically or democratically. To prevent a further shift of power towards intergovernmentalism, efforts to democratize the EU system of government need to be directed at the supranational institutions: Parliament and Commission. In the next section we discuss whether the direct election of the Commission president offers a suitable approach. Before that, Figure 2 provides a summary of the presidential and parliamentary features of government in the EU, which consequently illustrates the difficulty of placing the EU clearly in one category.

Figure 2 Parliamentary and Presidential Features of the EU System of Government

DIRECT ELECTION AND PRESIDENTIAL FUNCTIONAL LOGIC IN THE EU

Given the affinity of the European institutional system to presidentialism, it is astounding how few supporters there have been for a presidential democratization approach in discussions of EU reform. Among those arguing for an institutional reform path, the supporters of a parliamentary democratization approach are in the overwhelming majority.Footnote 28 In a number of academic overviews on the democracy deficit and reform options the possibility of directly electing the Commission president is not even mentioned,Footnote 29 despite the fact that the presidentialism hypothesis is actually not all that new. Originally postulated by British political scientist and legal scholar Vernon Bogdanor,Footnote 30 the notion was further developed by Simon HixFootnote 31 and continues to be put forward in the reform discussion.Footnote 32 In the context of the debate on a constitution for Europe, a directly elected Commission president was furthermore proposed by then German foreign minister Joschka FischerFootnote 33 and later by former Irish prime minister John Bruton.Footnote 34

Over the course of the convention, however, Fischer, for example, distanced himself from his famous speech at the Humboldt University and sided with the supporters of the parliamentary reform model. Even more remarkable is the about-face by the originator of the EU presidentialism concept, Bogdanor.Footnote 35 Not only does he unequivocally recommend the parliamentary system as the suitable form of government and democratization approach, he also bases his concept on the British model, which – as a strict majoritarian system – could be difficult to impose upon the heavily consensus-oriented structure of the European decision-making system. Nonetheless, Bogdanor seeks to reconcile the two, the EU political system with Westminster democracy. Consequently, his proposal extends further than the mainstream approach for parliamentarizing the EU by suggesting that the partisan composition of the entire Commission reflect the majority party or parties in the EP. Moreover, because the EP is already in a position to push through a more party-political ‘election’ of the Commission, democratizing the EU along the parliamentary path would not even require changes to the existing treaties. This constitutes the main advantage of this model over the presidential direct-election concept.

Even taking the last argument at face value,Footnote 36 the question remains of why the Parliament and the parties represented there should bring themselves to adopt such a strategy, which they could have done at any time in the past. Since they have not done so up to now – for whatever reason – the institutional and political framework would need to have changed in a manner that would now provide the necessary incentives for the EP members to assert themselves in the Commission appointment. Perhaps even more important than the formal prerequisites are the substantive conditions regarding system compatibility or fit; a key factor being the party system. Holzinger and Knill point out appropriately that the suitability of a concept for democratization will ultimately depend on the demands it places upon the political parties and their Europeanization.Footnote 37 A comparison between the two models and their respective functional logics reveals that the level of coherency and consolidation necessary for a parliamentary system to work is significantly higher than in the presidential model. The political linkage or ‘common destiny’ between government and parliamentary majority, upon which the parliamentary system rests, can only be sustained if the political parties have developed a high degree of programmatic and organizational cohesion. The current European party system, on the other hand is, at best, only partially consolidated; the most progress has been achieved on the organizational side.Footnote 38 A presidential system, however, can manage without well-organized, advanced party structures. For one, the head of government possesses legitimacy independent of parliament on account of the popular election and can remain in office regardless of the legislature's support or ‘confidence’. The parliament as an institution as well as the individual members for their part are in a comparatively comfortable position to compete with or confront the executive, as there is no need for (party) political unity between the two governing institutions that obliges MPs to adhere to party discipline.

To assume that a parliament is weak because it lacks the power to appoint the government would be severely erroneous. Though counterintuitive, the example of the US Congress illustrates that the parliaments that are powerful are those that are primarily limited to legislative tasks.Footnote 39 This helps to explain the relatively strong position of the European Parliament, compared to national parliaments. Certainly it is not on an equal footing with the Council in all policy areas, but when it can co-decide, the EP wields considerably more influence than its counterparts at national level, where parliaments over time have fallen behind their respective governments who have come to dominate the legislative process. Because members of the majority are not ‘allowed’ to govern, and members of the minority are not ‘able’ to govern, the parliamentary system of government can prove rather frustrating at times for MPs.Footnote 40 Were they to become responsible for forming and supporting a European government, MPs in Strasbourg and Brussels could end up in a similarly dissatisfying situation. This begs the question of why, then, they should be interested in parliamentarizing the EP.

That the European legislature already behaves like a presidential system can be seen in the MPs' voting patterns. Numerous studies indicate that disciplined party-voting is lower in the EP than in national parliamentary systems.Footnote 41 Cross-party voting coalitions are not uncommon for particular issues such as agriculture or regional policy. At the same time, unified party-voting is considerably higher than in the US Congress. This may reflect the European party traditions and would at least not preclude further development towards a parliamentary system. When it comes to coalition-building, however, the EP fully follows the presidential functional logic, where coalitions are formed ad hoc, on a vote-by-vote basis and with shifting majorities. In the third legislative period (1989–94), over 70 per cent of the recorded decisions were taken in consensus between the two largest party groups (social democrat – PES – and conservative – EPP). Since then a more antagonistic pattern of voting has been developing along the ideological left–right division. In addition to long-established but now diminishing cooperation between the two largest parties, voting in the EP has been increasingly characterized by shifting centre-left and centre-right alliances, usually facilitated by the liberals (ELDR), who are open for voting together with either the PES or the EPP groups.

Both the underpinning and driving force behind the flexible pattern of voting in the EP are provided by the multiparty structure, which has consisted of no fewer than eight party groups since the election in 2004. Thus, from an institutional standpoint, cohesive party voting and flexible, ad hoc coalition-building (as opposed to stable ‘bloc voting’) represent two sides of the same coin. Interestingly, the EU parliamentary practice would remain unaffected by the direct election of the Commission president. The EP could continue to democratize further as the EU popular chamber (for example through a more uniform electoral law with greater respect to the principle of equal representation), expand its legislative competences relative to the Council and still maintain its powers of executive control over the Commission (including the power to confirm nominated commissioners before appointment). The Commission would in fact become more politicized, but its institutional integrity and independence would not even be compromised. That independence is a valuable asset in the Commission's relationships with the member states and with the Parliament since the Commission needs to refrain from taking a party-political bias if it hopes to gain broad approval for its proposals.Footnote 42 Hence, the Commission president is well advised to maintain the necessary balance when building the Commission team.

While the parliamentary model could be pursued within the constitutional provisions of the EU, it would clearly necessitate realignment in the relations between the Parliament and Commission. The introduction of a direct election of the Commission president, on the other hand, could be integrated into the existing institutional system without the need to alter the constitutional practice developed so far. The only formal amendment would entail a necessary provision in the treaties; no other changes would need to be made to the institutional structure. Admittedly, this would call into question the sense of keeping the newly established president of the European Council since a popularly elected Commission president would no doubt take on representative tasks along with the regular executive powers. The overall loss to the EU from rescinding this additional executive office would probably be negligible, if indeed a loss at all.

A CRITIQUE OF THE PRESIDENTIAL APPROACH

Opponents of presidential democratization argue that direct election would unduly strain the legitimating basis of European politics, which is grounded in consensus-oriented decision-making among the member states. One of the main concerns is the structural majority: that the smaller member states' fear of being ‘overruled’ would be realized as a consequence of the direct election of the EU executive. Certainly, direct election would introduce an additional majoritarian element into the consociational system of the EU and thus shift it somewhat towards majoritarian democracy. However, precisely this sort of shift can hardly be avoided if the EU political system is to become more democratic on the whole. It would be a gross misunderstanding of Lijphart's dichotomous typology of majoritarian (‘Westminster’) vs. consensus democracy,Footnote 43 for example, to assume that one form of democracy excludes the other. To be sure, a generally majoritarian-style democracy without a minimum of consensus-promoting structures or practices would prove just as ineffectual as a purely consensus democracy without any majoritarian elements. This is clearly reflected in the fact that, even in consensus democracies such as Switzerland, the Benelux and Nordic countries, the procedures for passing laws as well as appointing and (excluding Switzerland) removing the government are all taken by simple or absolute majority. In the supranational European Union, on the other hand, the majority principle now applies only to the investiture of the Commission and the regular voting procedure in the EP. In order to carry a motion of censure against the Commission, a two-thirds majority vote is needed in the EP, while the nomination of the Commission president in the European Council and legal acts in the Council of Ministers require a qualified majority, in many cases even unanimity.

Consequently, the direct election of the Commission president would not change the overall consensual quality of the European polity. The risk posed by a Commission president voted into office by a majority who then only governs in the interests of those voters is tremendously low, not least because the Commission depends on the broad support of both the Council of Ministers, who can safeguard member state interests, and the European Parliament in pushing through legislative proposals. Especially in the process of negotiating on legal acts, the EP would continue to benefit from its institutional independence. Also, the claim that direct election would lead to a marginalization of the smaller states is unfounded (albeit plausible), judging by European political practice. Simon Hix, for example, raises the concern that candidates for the presidency would resort to the vote-maximizing strategy of focusing on the larger, highly populous member states in their campaigns.Footnote 44 Yet Europe's extraordinary linguistic diversity alone would make an election campaign impossible without the help of the national party organizations to present candidates to their respective publics. Indeed, European elections and campaigns will maintain their decentralized character, guaranteeing for all member states, big and small, a say in the electoral matter.

Moreover, what applies to the election applies to the nomination of candidates by the European parties. Their primary goal would naturally be to present candidates who are well known and respected across Europe and thus capable of uniting a majority in the European electorate. It would be anything but safe to assume that such candidates from larger member states would automatically fare better in the electoral race. Obviously, smaller states can generate renowned candidates, as demonstrated in politicians such as Guy Verhofstadt (Belgium), Wolfgang Schüssel (Austria) or Jean-Claude Juncker (Luxembourg), all of whom have been repeatedly sought after as candidates for the highest European offices. Not even the nominating procedure would necessarily put the bigger member states at an advantage. Quite the opposite could just as easily be the case when party organizations from larger states, in insisting on their ‘own’ candidates, mutually block one another, leaving room for a tertius gaudens from one of the smaller states to win out in the internal party nomination process.

Aside from whether one subscribes to these feared drawbacks of the presidential concept or tries to dispel them, one thing can be deemed certain. The same issues related to the challenges for nominating and electing candidates in a very diverse Europe would be posed just as much by the parliamentary model as the presidential one. In this respect, there is no significant difference between establishing a direct election or making the EP election an indirect vote for a prime-minister type of Commission president; both forms of government appointment are majoritarian in character. However, the differences between the two models become rather salient when considering the aspect of governing that at the European level, as much as at the national level, takes place primarily through lawmaking. In this respect, a Commission president voted by and responsible to the EP would coincide with majoritarian democracy to a much greater extent than a separate and popularly elected president.

A parliamentarized president of the Commission and the parliamentary majority would need to enter into a long-term voting coalition, which takes a polarizing effect on account of the functional logic inherent to the fused relationship between executive and legislative and could even provoke conflict with the Council of Ministers. By contrast, the structural, power-separating design of presidentialism necessitates consensualism. Instead of a lasting coalition between the government and its majority, short-term voting majorities are formed, changed and re-formed, not only between various parties and on a cross-party basis, but also between institutions. The lack of a solid majority in parliament certainly makes ‘governing’ more difficult for the Commission. In the triangular relationship between Commission, Council and Parliament, the presidential structure provides the advantage of requiring compromise, which is exceptionally vital for decision-making in the intergovernmental and supranational polity of the EU. As opposed to the power-fusing design of a parliamentary system, the presidential structure, along with the corresponding functional logic, conforms to the heterogeneity of European politics.

The advantages of the presidentialization approach to democratizing the EU also stem from the majoritarian-democratic dimension. For one thing, a popularly legitimated Commission would find itself in a stronger position to assert its initiatives. At the same time, a substantial increase in the legitimacy of European politics would emanate from presidential democratization. By granting citizens the opportunity to vote for a person and a political direction at the same time, the popular election of the Commission president would fundamentally improve the institutional dimension of the democratic deficit that has long afflicted the Community.

As it currently stands, the institutional system of the EU is only partially capable of bringing forth broader policy alternatives within the governing process. From the perspective of the citizen, it seems much more like an arena for intergovernmental conflict. Here lies the crux of a democratic election: something has to be at stake in the election in order for it to be worth the voters' while, meaning that their decision has to have observable consequences.Footnote 45 Direct election would be able to offer precisely that. An EU head of government voted popularly into office would bear the prerogative and burden of political initiative, and thus could not (easily) shirk or deflect responsibility to the bureaucracy or the Council of Ministers. The president's position as an institutional embodiment of European unity and a representative of the Community both at home and abroad would also be duly enhanced.

What is more, a direct election would put a stop to the previous ‘second-order’ quality of European elections. Not only would the election take place as a truly Europe-wide procedure, which is still not the case with EP elections,Footnote 46 the competition for votes would itself have a Europeanizing effect as well: parties would be compelled, after uniting behind a single candidate and a single programme, to lead a cross-border joint campaign. Possible candidates, for example, could be incumbent or former heads of government, statespersons or other political figures well known beyond the boundaries of their home countries. As a result, a face could finally be attached to European politics, while the position of Commission president itself would require a campaign held on European issues, and not under the umbrella of national politics. The consequence would be increased pressure for European political mobilization, which in turn could strengthen the sense of community among citizens of the Union, promote the development of a Europe-wide party system and, last but not least, have a spillover effect on the elections to the European Parliament.

CONCLUSION

Despite its advantages and institutional fit, little attention was paid in the constitutional debate to direct election as an alternative proposal to democratizing the EU. As to why it was disregarded, one possible explanation lies in the parliamentary traditions of the member states, which are mostly unfamiliar with the presidential model. Another factor is the general suspicion that a popular election of the Commission president would place a heavier burden on the consensual structure of the EU than an election by the Parliament. Although both objections can be refuted upon closer inspection, they have proved to have the most influence on the political and academic debate. Given that, the idea of direct election barely stood a chance of getting adopted, even if notable politicians sympathized with it at one point or another.

The finalité of Europe is by no means final, nor does the further development of the EU system of government along the presidential path have to be deemed an impossibility. After the signing of the Lisbon Treaty, the EU missed another opportunity truly to democratize its decision-making system. In concrete terms, democracy in Europe boils down to a European government that is responsible and accountable before the European voters, which cannot be said of the Commission or the Council. With regard to the Council, the population of a member state will be considered more proportionally on account of the Lisbon Treaty, which constitutes a step forward, but this does not change the fact that its members are, and will continue to be, only indirectly legitimated. As for the Commission, its appointment will remain problematic, in the sense that it can hardly be conceived of as a democratic act of election, even if the treaty refers to it as such.

The time when Europe could focus on output legitimacy and rely on ‘permissive consensus’ has passed. The European leaders were reminded of this when the people of Ireland rejected the Lisbon Treaty in a referendum, making it all too clear that the small amount of more democracy they promised will not close the legitimacy gap. From the historical perspective on democratization, elites in most cases have only been prepared to take reforms when under pressure. Why then should that be any different in the European Union? The main problem that the Community faces is that it is an elite-centred structure that plays, from the perspective of the European citizen, a supporting role at best. The unfinished state of European democracy thus requires us to contemplate and deliberate further on how to democratize the institutions of the EU. When the window of opportunity for reform opens again, political science can contribute by providing an appropriate blueprint, one that addresses, among other things, the question of ‘parliamentary or presidential’.