The first Protestant Bible in Chinese was published in the early nineteenth century. In the early history of Chinese Protestant Bible translation, Baptist missionaries played an important role. Before the end of the eighteenth century, English Baptist minister William Carey (1761–1834) from Serampore, a city in the Indian state of West Bengal, was already concerned about the spiritual needs of the nations in the regions of South-East Asia. At the Serampore mission post, the missionaries established a press to publish and distribute translations of the Bible in the languages of the East, including the Chinese Bible. After Baptist missionaries arrived in China, they kept a positive attitude to Chinese Bible translation and carried out different Bible translation projects despite the difficulties they faced.

Before the publication of the Chinese Union Version (CUV), the common Chinese Bible translation project which was initiated by Protestant missionaries from 1890 to 1919, Protestant missionaries had already translated the Bible into classical Chinese (they called it “High Wen-li” 深文理), easy classical Chinese (they called it “Easy Wen-li” 淺文理, the simpler form of the literary style), Mandarin (官話) and more than twenty local dialects in China.Footnote 1 Baptist missionaries in China published several versions of the Bible by themselves in the middle of the nineteenth century, long before the completion of the CUV. However, they took a different approach to Bible translation from others Protestants and it is worthwhile to study this further.

This article mainly focuses on the Baptist missionaries’ efforts in Bible translation in China, especially before the publication of CUV in the early twentieth century. It is important to study this historical period as it is a period in which different versions of the Bible translation were produced and used as evangelistic and equipping tools in the formation of the Chinese churches.Footnote 2 In historical retrospect, it also reviews Baptist translation approaches and practices in comparison to those of other Protestant denominations.

(I) Early History of Chinese Bible Translation

Probably, the largest translation enterprise ever undertaken in China was Bible translation. The Bible translators of Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox churches all had a part to play in this. They had translated parts or the whole Bible into the common language and various Chinese dialects.

The Nestorian missionaries were the first to bring Christianity into China in the early period of the Tang Dynasty (618–907). Existing documents, including the Nestorian Monument, a stone tablet found in the city of Sian, suggest that some of the Scriptures were translated during this time.Footnote 3

Roman Catholic missionary priests from Europe were recorded first entering China in the thirteenth century and then re-entered during the sixteenth century.Footnote 4 Jesuit missionaries were dominant in the second period by the late Ming dynasty (1368–1644). The earliest classical Chinese translation of the Bible still in existence was done by Jean Basset (1662–1707) in the early Qing dynasty (1644–1912). Basset was a Catholic missionary of Missions Étrangères de Paris (MEP). He went to Sichuan (formerly Romanised as Szechuan) province in China in the early eighteenth century. However, Basset's translation was not complete. He only translated the New Testament (NT) up to the Chapter One of Hebrews.Footnote 5 In 1806, ‘Sloane MS#3599,’ one of Basset's manuscripts which was kept in the British Museum, was copied by Protestant missionary Robert Morrison (1782–1834) of London Missionary Society (LMS) and his Chinese assistant Yong Sam-tak. This copy became the basis of Morrison's NT translation after he arrived in China. Through Morrison, this copy was also made available to the English Baptist missionary Joshua Marshman (1768–1837) in Serampore.Footnote 6

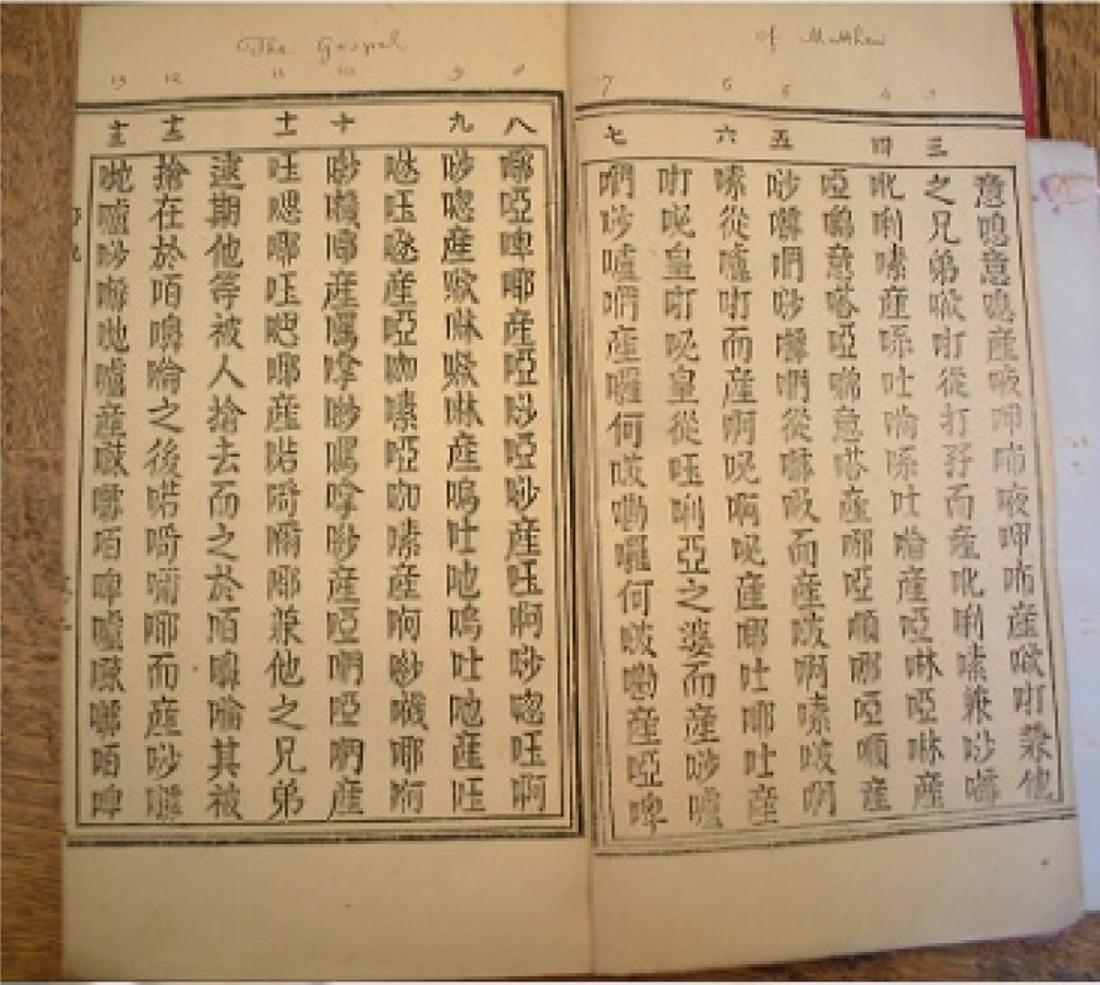

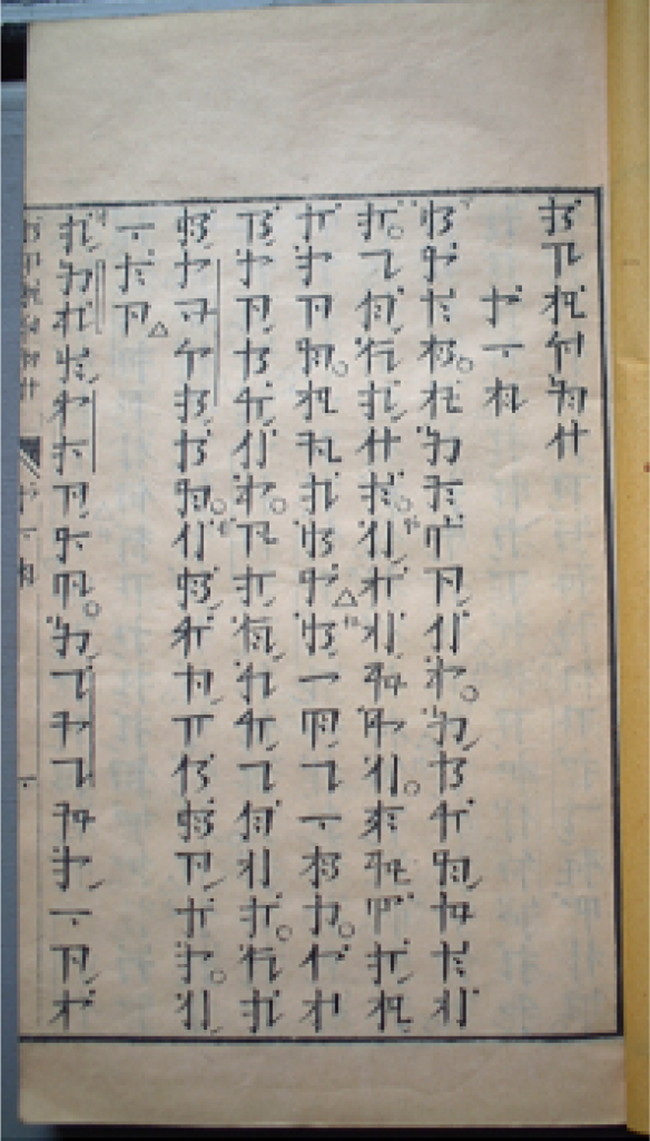

The first complete edition of the Protestant Bible printed in Chinese was published by Marshman. He was a missionary from the Baptist Missionary Society (BMS) and worked with William Carey in Serampore. In the early nineteenth century, BMS missionaries and their colleagues played an important role in starting missionary work among oversea Chinese people. They also translated the Bible into several Indian and Chinese languages.Footnote 7 In Serampore from 1805, Marshman and his son started translating the Bible into Chinese with his Armenian helper Hovhannes Ghazarian (also known as Johannes Lassar, 1781–1835?) who was born in Macao. Lassar was acquainted with the Chinese language. He helped to translate St Matthew's Gospel and St Mark's Gospel into Chinese.Footnote 8 In 1810, these two Gospels were printed by the Serampore Press. The translation of the NT was completed in 1811, and the whole Bible was printed in 1822. This Bible was in traditional classical Chinese, a written form of literary Chinese which was used for almost all formal writing in China until the early twentieth century.

Although Marshman's version was the first complete Bible in Chinese it had limited influence, partly because it was only used by the earliest Baptist missionaries and was mainly circulated among the Chinese outside China. Another version of the Chinese Bible was produced by Robert Morrison and William Milne (1785–1822) of the LMS in China at the same time. In 1810, Morrison started translating the Bible in Canton (now Guangzhou) of China and Milne joined the project later. In 1823, Morrison published a translation of the Holy Bible in twenty-one volumes with the title Shentian Shengshu (神天聖書), which became the basis of various subsequent versions of the Chinese Bible. In the 1830s, there were some other translations done by Walter Henry Medhurst (1796–1857), the LMS missionary in Batavia, and others, such as German Lutheran missionary Karl Friedrich August Gützlaff (1803–1851), but none of these replaced Morrison's.

Fig. 1. The Gospel of St. Matthew by Joshua Marshman and Johannes Lassar in 1810. One of the earliest Bible edition by the Protestant missionaries in Chinese. (Used by Permission of the Bible Society Collection, Cambridge University Library.)

Since the early nineteenth century, Baptist missionaries had worked among the Chinese communities in Southeast Asia. The first Baptist missionaries to China were the Reverend Jehu Lewis Shuck (1812–1863) and his wife Henrietta Hall (1817–1844). Under the auspices of the Baptist Triennial Convention in 1835, they were appointed for missionary service in China and arrived in Macao in 1836.Footnote 9 In 1841, Shuck wrote the Ten Commandments of Exodus on a leaflet.Footnote 10 This translation was only one page long, but it was the beginning of Bible translation by Baptist missionaries in China.

After the signing of the Treaty of Nanking (1842) which ended the First Opium War (1839–1842) in China, the missionaries were allowed to stay in Hong Kong and later five other ports Canton, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo and Shanghai. Until 1852, Shuck cooperated with other Baptist missionaries in China, such as Issachar Jacox Roberts (1802–1871) and William Dean (1807–1895), and went on to serve in Macao, Hong Kong, Canton, and Shanghai. Shuck and some other Baptist missionaries also participated in the project of producing the Chinese Bible version called the Delegates’ Version (DV) in the 1840s. However, all the Baptist members of the translation project, except Shuck, withdrew from it in 1847 and translated the Bible themselves. The reasons for their withdrawal from this project reflected their approach to Bible translation.

(II) The Baptists’ stance on the ‘Term Question’

In 1843, Protestant missionaries from different countries and denominations gathered in Hong Kong, an island which was ceded to the United Kingdom in perpetuity under the Treaty of Nanking. These missionaries decided to translate the Bible into Chinese using standardised terminologies for names and terms. Since the missionaries were called the delegates in the conference, this version was therefore known as the Delegates’ Version (DV) with the NT published in 1852 and the Old Testament (OT) in 1854.Footnote 11 Adopted by many missionaries in China, the DV was reprinted many times and was still in use as late as the early twentieth century.

The translation committee of the DV consisted of Protestant missionaries from different countries and denominations. Several Baptist missionaries, including William Dean, Issachar J. Roberts, Daniel Jerome Magowan (1814–1893) and J. L. Shuck, were members of this committee. Although the Baptist missionaries in China were invited, they never played a major role in the translation work because the committee was dominated by the missionaries of LMS, especially Medhurst.

The DV had remarkable significance in the history of Christianity in China. However, there were heavy hiccups and disputes in the translation process. Their biggest point of contention was how to express “God” in Chinese (or transliterate “Elohim” in Hebrew and “Theos” in Greek). This controversy was the so-called ‘Term Question’.

From the seventeenth to the eighteenth century, the controversy within the Roman Catholic mission on the ‘Term Question’ had to do with competing Chinese terms for ‘God’. In the earlier period, the Catholic missionaries already had several suggestions. For example, Jean Basset translated ‘God’ as Shen (神). However, after the early eighteenth century, the Roman Catholic Church decided to translate ‘Supreme God’ as Tianzhu (天主, which means “Heavenly Lord” or “Lord of Heaven”).Footnote 12 Therefore, ‘Catholicism’ is most commonly rendered as Tianzhu Jiao (天主教, which means ‘religion of Heavenly Lord’) even today.

Joshua Marshman in Serampore often translated ‘God’ as Shen, but he also used Tianzhu in his early Bible translations. Marshman used Shen Hún (神魂, which means ‘Holy Ghost’) to translate ‘Holy Spirit’. However, in his 1822 edition of the Chinese Bible, Marshman finally translated ‘God’ as Shen and ‘Holy Spirit’ as Shèng Shenfēng (聖神風, which means ‘Holy God wind’).

In the earliest edition of the Acts of the Apostles, which was published in 1810, Robert Morrison of LMS took Jean Basset's translation as a point of reference and translated ‘God’ as Shen and ‘Holy Spirit’ as Shèng Fēng (聖風, which means ‘Holy wind’). In the first completed edition of the Holy Bible in 1823, he translated ‘God’ as Shen and ‘Holy Spirit’ as Shen Zhī Fēng (神之風, which means ‘wind of God’).Footnote 13 However, William Milne, the LMS missionary colleague of Morrison, also used Shangdi (上帝, ‘God’, which is the name of God in classical Chinese texts) in his commentary of Ephesians which was published in 1825. Obviously, in Milne's view, these two terms, Shen and Shangdi, were interchangeable. In the 1830s, Medhurst mainly used the term Shangdi for ‘God’ and Shèng Shen (聖神, which means ‘Holy God’) for ‘Holy Spirit’. His co-worker Karl F. A. Gützlaff, a German Lutheran missionary based in Hong Kong, also used the same terms, but he sometimes used Shangdi Zhī Shen (上帝之神, both Shangdi and Shen means ‘God’, this term literally is ‘God of God’) for ‘Holy Spirit’.

Obviously, the missionaries could not reach a conclusion at that time. Unsurprisingly, the Protestant missionaries had a heated argument about the ‘Term Question’ in the translation process of the DV. Shortly after the beginning of DV's translation, the translation committee had to be dissolved as some missionaries from America did not accept the English missionaries’ adoption of the term Shangdi for God in Bible translation. The Americans preferred another term Shen for the Christian God, because they thought Shangdi was understood as the name of a God rather than a generic term.Footnote 14

The choices were narrowed down to Shen or Shangdi, but the agreement on the ‘Term Question’ was never reached. The Baptists strongly supported the term Shen, therefore their Bible editions always used this term for God. For the other Protestant denominations, most, if not all, believed Shen and Shangdi were interchangeable. Nevertheless, they were not able to decide which was the better translation.

A similar problem was encountered in translating “YHWH” (transliteration of Hebrew יהוה, the Tetragrammaton) into Chinese. In the nineteenth century, two different approaches were adopted by different missionaries. One was to translate “YHWH” as Zhu (主, which means ‘Lord’), Shangzhu (上主, which means ‘Highly Lord’) or other alternatives with similar meaning. The other was to have the term transliterated into Chinese.

Some Protestant missionaries in the earlier period usually translated “YHWH” in the OT as Zhu or similar words. For example, Morrison and Milne used Shenzhu (神主, which means ‘God Lord’) or Zhu. Towards the end of the 1830s, Karl F. A. Gützlaff used Huang Shangdi (皇上帝, which means ‘Imperial God’). Later, Gützlaff's translations had influence on the Bible published by the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, an oppositional state in China from 1851 to 1864. The knowledge about Christianity of Hong Xiuquan (洪秀全, 1814–1864), the leader of the Taiping Rebellion against the Qing Dynasty, came from the tract Good Words to Admonish the Age (勸世良言) which was written by a Chinese Pastor Liang Fa (梁發, 1789–1855) and was published in 1832. In this tract, there were more than ten ways to translate the term ‘God’, such as Shentian Shangdi (神天上帝, which means ‘God Heaven God’), Shen Yehuohua (神爺火華, which means ‘God Jehovah’. Yehuohua was an earlier transliteration of Jehovah) and Shangdi, etc. There were over thirty translations for ‘God’ in the other documents of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom.

The Baptist missionaries in China inclined to transliterate “YHWH” because they thought there was no term in Chinese which could fully express the meaning of the Tetragrammaton. In Joshua Marshman's translation of the Bible, the translation of “YHWH” was not consistent. For example, in the earlier part of Genesis, Zhu or Shenzhu was used; but after 9:26, Yehèhua (耶賀華, another earlier transliteration of Jehovah) was used. However, the latter transliteration was not used after Marshman. Another Baptist missionary J. L. Shuck translated “YHWH” as Shangdi in his Ten Commandments in 1841, but this was an exceptional case in the Baptist tradition.

Towards the end of the 1840s, an American Baptist missionary William Dean transliterated “YHWH” as Yaohua (耀華, a transliteration of Jehovah and had a literal meaning of ‘glory China’). Josiah Goddard (1813–1854), another important American Baptist Bible translator, used Zhushen (主神, which means ‘Lord God’) in the earlier edition of Genesis in 1849 (this translation only contained the first six chapters of Genesis). But in his later version of Genesis in 1850, he also transliterated Jehovah as Yaohua. In the end, most Chinese Bibles, including the Baptist's translation, mainly used the transliterated term Yehehua (耶和華, a final transliteration of Jehovah) for “YHWH”.

Apparently, in the second half of the nineteenth century, translators failed to reach a consensus on the best way to translate ‘God’ and “YHWH.” In 1904, the missionaries from the north of China proposed that a ‘Union Term’ should be used. They suggested translating ‘God’ as Shangdi and ‘Spirit’ as Ling (靈, which means ‘Spirit’). They sent out letters along with questionnaires to all the mission organisations in China, expressing their wish to use an ‘Union Term’ in the Chinese Bibles and getting feedback from the mission organisations.Footnote 15 This last attempt in solving the translation dispute was in vain. From then till now, the Chinese Bibles used in the Protestant churches have two renderings of God's name: Shen and Shangdi. Meanwhile, Tianzhu is used in the Bible of the Catholic churches. As for the term ‘Holy Spirit’, the Protestant churches referred to it as Shèngling (聖靈, which means ‘Holy Spirit’) whereas the Catholic churches used Shèngshen (聖神, which means ‘Holy Ghost’) instead. For “YHWH,” most of the Chinese Bible use the transliteration Yehehua, but some recent translations use Shangzhu.

(III) Controversy on the translation of ‘baptism’

Around the same time of the controversy on the ‘Term Question’, the Baptist missionaries had heated argument about how to translate ‘baptizō’ (transliteration of the Greek verb βαπτίζω, which means ‘baptise’).Footnote 16 The controversy was never settled. The Baptist missionaries withdrew from the committee of DV translation in June of 1847.Footnote 17

In Martin Luther's Small Catechism, a definition of ‘baptise’ was given: “What is the meaning of the word ‘baptize’? ‘Baptize’ means to apply water by washing, pouring, sprinkling, or immersing”.Footnote 18 Most denominations said that there were several acceptable choices regarding the action involved in baptism. Some churches only sprinkle or pour water on the person's head. Therefore, most of the missionaries in China inclined to translate ‘baptizō’ with a general meaning in Chinese. For instance, Robert Morrison translated ‘baptizō’ as Xi (洗, which means ‘wash’). He explained that Xi meant “to wash the feet; to wash physically or morally; to cleanse”Footnote 19 and used Xili (洗禮, which means ‘rite of washing’) in his translation. Xi is a word with a general meaning in Chinese and can be used to refer to the action of washing somebody, or only sprinkling or pouring water on one's head and face.

The Baptist missionaries preferred Shen for God on the ‘Term Question’ and agreed with some other missionaries. However, in their religious tradition, they were more concerned about term ‘baptism’ and insisted on translating this term with the meaning of immersion. The churches from the Baptist tradition believed that baptism was only for those who had put their faith in Jesus Christ and accepted Him as their Lord and Saviour. Therefore, the churches insisted on “baptism of adults by immersion”. Since the term Xi could only denote the meaning of washing parts of the body, such as the head and the face, and failed to express the full-fledged meaning of ‘baptizō’, the Baptists found the translation unacceptable. They insisted on the term ‘immersion’ which had the implication of submerging the whole body beneath the surface of the water. The question remained was how this term should be translated into Chinese.

The Baptists suggested several Chinese terms at different points of time, implying that it was not easy to find a suitable term to translate “baptism of adults by immersion”. Joshua Marshman preferred using Zhán (蘸) or Cuì (淬), both meant “dip into water” or the verb compound Zháncuì (蘸淬, which also meant “dip into water”) to denote ‘baptizō’. However, the terms were unpopular in the Chinese context and were not accepted by other missionaries.

In the 1830s, after the publication of Marshman's Bible, the American Baptist missions began to insist on translating ‘baptizō’ according to the meaning of ‘immerse/immersion’. Adoniram Judson (1788–1850), an American Baptist missionary who served in Burma, translated ‘baptizō’ according to the meaning of ‘immerse/immersion’ in the Burmese Bible and this translation became the first Asian Bible sponsored by the American Bible Society (ABS). However, until 1835, the ABS refused to publish the Bengalese NT which was based on the translation principle of ‘immerse/immersion’.Footnote 20 As a result, the American Baptist missionaries decided to break away from the ABS and found the American and Foreign Bible Society (AFBS), an organisation with Baptist background, in 1837.Footnote 21 In 1841, William H. Wyckoff (1807–1877), the Baptist scholar of the AFBS, published a paper to discuss the translation of ‘baptizō’. Footnote 22 He reviewed thirty-eight translations in seventeen different languages, excluding Chinese, and insisted that many languages used the words with the meaning of ‘immerse’ to translate ‘baptizō’.Footnote 23

By 1847 the AFBS was dissatisfied with approaches to Bible translation, which was dominated by the LMS missionaries. Their 1847 report mentioned that “the Baptist missionaries in China, although they have been invited, cannot consistently unite in the enterprise, as the history of bible operations within the last few years leaves no room to hope, that the simple principle of strictly translating the sacred scriptures from their originals, would be uniformly observed”.Footnote 24 They were disappointed that the first translation of the Protestant Bible into Chinese was finished by a Baptist missionary, i.e. Joshua Marshman, but his work was not succeeded by the other Baptist translators.

During the translation of DV, the Baptist missionaries did not accept Xi as a suitable word to denote ‘baptizō’. However, they could only suggest Zhán, which had been used by Marshman or other words of the same meaning. Although they insisted on using another term Jin (浸, meaning ‘immerse’ or ‘soak’) later, the committee still could not reach a consensus during 1847. The DV translation committee allowed the missions to translate this word according to their tradition, but in the end no edition was published with the term ‘immerse’.

Before the committee met in June of 1847, the Baptist missionaries, except J. L. Shuck, withdrew from the DV translation committee under the permission of their missions. However, the ‘baptizō’ controversy between the Baptist and Pædobaptist missionaries caused discord from this point in time until the translation of the CUV.

(IV) Baptists’ Translations Thereafter

After the Baptist missionaries withdrew from the DV translation committee, they still needed to find a suitable term to translate ‘baptizō’. The first suggestion came from American Baptist missionary William Dean. He was the chief translator of a team of missionaries, including Josiah Goddard and Edward C. Lord (1817–1887), who was to revise Marshman's translation of the Bible.Footnote 25 In St Matthew's Gospel of 1848, William Dean used the term Wèn (搵) as the translation of ‘baptizō’.Footnote 26 In the exegetical notes of Matthew 28:19, he mentioned that there were several terms which could be used to translate ‘baptizō’, including Wèn (搵), Jìn (浸), Chén (沉), Xǐ (洗) and Chén Yù (沉浴). However, within these five terms, only Xǐ had a general meaning of ‘wash’, other terms had the meaning of ‘dip into water’. In other words, the missionaries from other denominations could not accept any suggestions other than Xǐ.

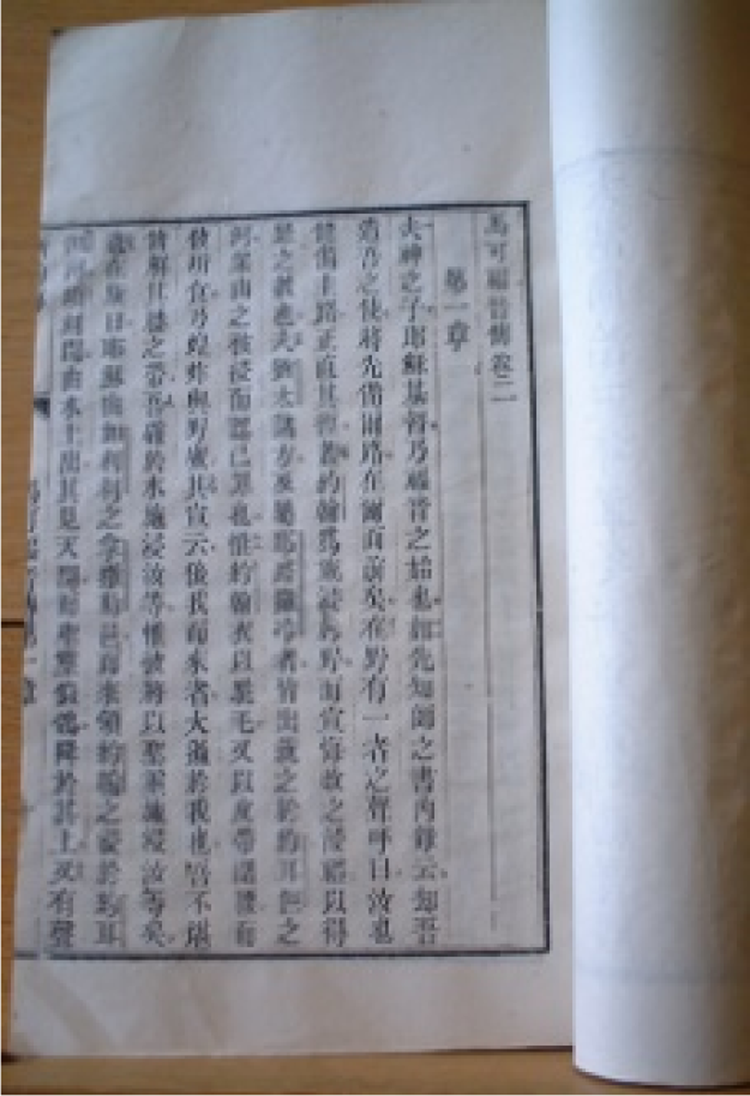

The final decision was suggested by Josiah Goddard in the NT of 1853 as Jìnli (浸禮, meaning ‘rite of immersion’).Footnote 27 Jin as a term then passed into common use in the Baptist churches of China.

Josiah Goddard was an American Baptist missionary and had worked among the Chinese in Siam (Thailand), Singapore and Bangkok since 1838. In the early 1840s, Goddard started to revise Joshua Marshman's version in Bangkok.Footnote 28 When Goddard moved to Ningpo (now Ningbo) in China in 1848, the Baptist missionaries had already withdrawn from the DV translation committee. However, the DV translation committee still wanted to invite Goddard to participate in the project. He accepted the invitation and attended the meeting in Shanghai several times between 1848 and 1849 after going to China.

After Goddard moved to Ningpo, he continued to revise Marshman’s translation and published his NT in 1853.Footnote 29 Since he died in the following year, his labours were continued by William Dean and Edward C. Lord from the same mission.Footnote 30 In 1868, the OT translation work was completed and the whole Bible was published. In 1873, another American Baptist missionary Horace Jenkins (1832–1908) added reference details in the translation and published this Bible in Shanghai.

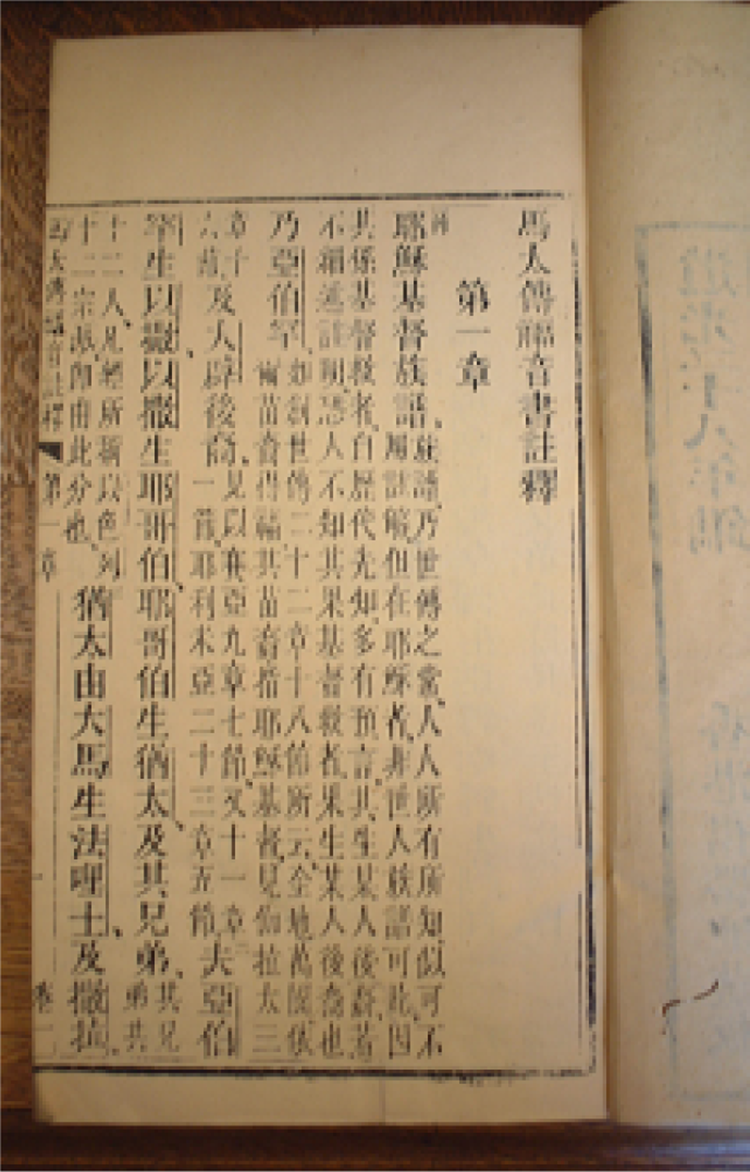

In general, the above-mentioned versions were translated in classical Chinese according to the translation principles of Baptists. Striking a balance between remaining faithful to the original (Hebrew and Greek) texts and fulfilling the needs of creating acceptable and understandable translation for the Chinese readers was particularly important. The Bible text of the Baptist version was usually printed with detailed commentary. For example, St Matthew's Gospel of 1848, translated by William Dean, was the first Bible edition published by the Baptists after they withdrew from the DV translation committee, and there was detailed commentary printed with the Bible text. In the earlier edition published before 1853, Goddard's version did not include the commentary, but in the latter editions which were revised by others, there were detailed commentary alongside the biblical text. However, since one of the founding principles of the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS) was to exclude any doctrinal and theological note or comment so as to solicit support from all Protestant denominations and avoid any sectarian rifts, the efforts of Baptist missionaries were not accepted by the BFBS. Therefore, the Baptists usually needed to publish their translations by themselves.Footnote 31

Fig. 2. The Gospel of St Matthew with commentary by William Dean in 1848. (Used by Permission of the Bible Society Collection, Cambridge University Library.)

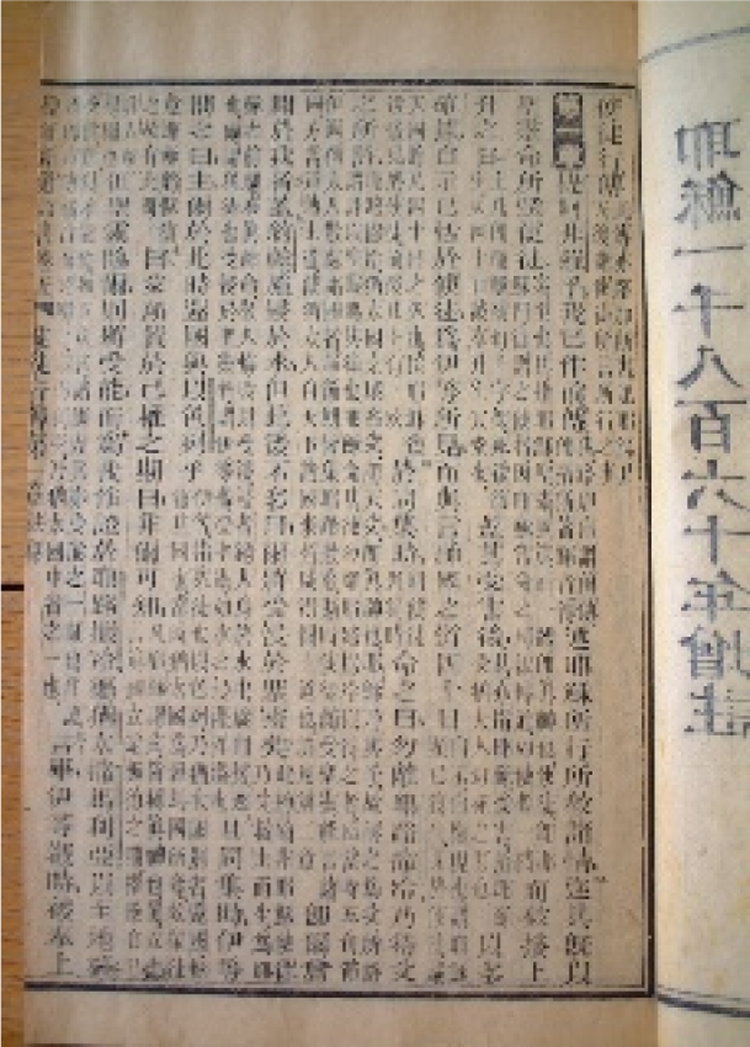

Another revision of Marshman's NT was made by English Baptist missionary Thomas H. Hudson (1800–1876) and published in 1867.Footnote 32 Hudson was a missionary from the English General Baptist Mission and arrived in China in 1845. He left his mission in 1855 and stayed in Ningpo as an independent missionary thereafter. Hudson used Marshman's version as the basis of his revision of the Chinese NT and published the Gospel of Mark in 1850 firstly. His version of NT was completed in 1866. In Hudson's NT, particular attention was given to literal faithfulness to the original text. However, unlike other Baptist translations, it did not provide any commentary, headings or footnotes.Footnote 33

Fig. 3. The New Testament with the map of Judah Kingdom by Joshua Goddard in 1853. (Used by Permission of the Bible Society Collection, Cambridge University Library.)

In the mid-nineteenth century, Baptist missionaries also translated and published several books of Bible in classical Chinese. In 1860, Issachar J. Roberts, a missionary of Southern Baptist Convention's Foreign Mission Board until 1852, had translated the Gospel of Luke and provided commentary alongside the translation.Footnote 34 In the same year, Acts of the Apostles with commentary was published by Charles Washington Gaillard (?-1862) from American Southern Baptist Mission.Footnote 35 Another American Baptist missionary Roswell Hobart Graves (1833–1912) also published a commentary on the Epistle to the Romans in Canton.Footnote 36

The above translations were solely completed by Baptist missionaries. However, Baptist missionaries also cooperated with some other missionaries in Bible translation. For instance, the English Baptist missionary Joseph Percy Bruce (1861–1934) joined with others to form a “Committee on Mandarin Romanisation” and translated the Gospel of St Mark in the Standard System of Mandarin Romanisation with the Chinese Text in 1903. In this version, the transliteration was made with the system adopted by the Educational Association of China. This was the last edition of the Bible in China's common language translated and published by Baptists before the CUV.

Fig. 4. The New Testament edition by Thomas H. Hudson in 1867. (Used by Permission of the Bible Society Collection, Cambridge University Library.)

The CUV's appearance coincided with the May Fourth Movement in 1919, so the Mandarin version of this Bible was regarded as having played a special role to the radical changes in language style at that time. Mandarin has been the official language of China since the early twentieth century. There were many Baptist achievements in the history of Chinese Bible translation, but there are no records to suggest that the Baptist missionaries had taken an important role in the translation of Bible into Mandarin before the publication of the CUV. There should be further studies to clarify the reason for this. For example, Baptist missionaries might not have been able to participate in the translation of the Bible in the second half of the nineteenth century. As more treaty ports were opened to the west after the Second Opium War in 1860, the Baptist missionaries were prepared to leave the treaty ports and serve inland. Usually, these missionaries worked alone with little support and would not have had enough space or time to translate the Bible.

Fig. 5. The Gospel of Luke with commentary by Issachar J. Roberts in 1860. (Used by Permission of the Bible Society Collection, Cambridge University Library.)

(V) Baptist Editions of the Chinese Union Version

In the late nineteenth century, many different Bible versions, produced with various approaches to translation, were circulating in China. Not a few Protestant missionaries in China shared the view that a common version for all Protestant churches in China was need.

The most important common Bible translation project of the Protestant Churches in China was initiated in the late nineteenth century. At the General Conference of Protestant Missionaries held in Shanghai in 1890, plans were made for the CUV in three styles: high classical Chinese, easy classical Chinese and Mandarin. The three Bible Societies in China, i.e. BFBS, ABS and National Bible Society of Scotland (NBSS), agreed to meet the expenses of the revision. After the publication of several tentative editions of the NT, people started to realize that it was not necessary to have two classical Chinese versions and the future lay with Mandarin. At the Centenary Conference of 1907 in Shanghai, a decision was made to stop further work in easy classical Chinese and to proceed with one version in the classical language only. The complete translations of the Bible in classical Chinese and Mandarin were finally made available in 1919 with both the Shen edition and the Shangdi edition.Footnote 37

Fig. 6. Acts of the Apostles with commentary by Charles Washington Gaillard in 1860. (Used by Permission of the Bible Society Collection, Cambridge University Library.)

Although the Baptists had been engaged in Chinese Bible translations for several decades before the project of the CUV was launched, they had only played an insignificant role in the project of the CUV. In the translation work of the CUV, only a few Baptist missionaries were involved. For example, American Baptist missionary R. H. Graves was a member of the translation committee for the easy classical edition of the CUV. However, in general, their achievement in the CUV project was insignificant.

Owing to their religious tradition, Baptist missionaries requested that their translation for ‘baptism’ (Jìn), must be adopted for the CUV. The agreement at the 1890 general conference granted each Bible Society “the right to publish such editions as it may choose, and with such terms for God, Spirit and baptize, as may be called for”. The Baptist missionaries therefore requested permission to publish their own CUV edition with their translations of the following terms: Shen for ‘God’, Shèngling for ‘Holy Spirit’ and Jin for ‘baptizō’.Footnote 38

In 1902, the China Baptist Publication Society which opened its Shanghai branch in 1899 published its own edition of easy classical NT without permission from other Bible societies. This was the first Baptist edition of CUV. After several years of discussions between the Baptists and all three Bible societies, they agreed that the China Baptist Publication Society had the rights to publish its own editions of the CUV. However, the Baptist edition should not contain any changes to the text, “except the terms for Baptize and its cognates and the other changes in particles rendered necessary by this”.Footnote 39 After the final publication of the CUV in 1919, the China Baptist Publication Society could freely publish their own edition of the CUV. Because of the “Term Question”, the CUV is divided into the Shen version and the Shangdi version. The Baptist churches in China mainly used the Shen version for ‘God’. The Jin version was only used by the Baptist churches, while others used Xi as the translation of ‘baptizō’.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, Chinese churches started to believe that the principle of translating the Bible should not only be remaining faithful to the original text, but also fulfilling the needs of making a readable and comprehensible translation for the people in China, whether they were in or out of the church. Over the years, the CUV has gained wide acceptance in the Chinese Protestant church.Footnote 40 However, it was basically the work of western missionaries and the Chinese translators only played a less important role. At the same time, the Chinese language has undergone tremendous changes over the past decades. Certain words and expressions in the CUV that formerly sounded smooth and natural have since become unnatural and unintelligible in the second half of the twentieth century. Except the issue of faithfulness and accuracy, there were also the concerns about naturalness and fluency. In view of this, the United Bible Societies (UBS) started a revision project for the CUV in 1983. In 2010, the Revised Chinese Union Version (RCUV), which was a revision of the CUV, was published by the UBS and the Hong Kong Bible Society (HKBS).Footnote 41 There was also a Baptist edition of RCUV with Xǐ changed to Jin for the term ‘baptizō’. This edition circulated in the Chinese Baptist churches.

(VI) Baptist Biblical Translations in Chinese Local Dialects

Since China has a large population spreading over a vast geographical area, the Chinese language consists of several dialect continuums. Many Protestant missionaries, particularly those working on the south-east coast of China, dedicated themselves to translate the Bible into various Chinese dialects from the end of the nineteenth century to the early twentieth century. According to existing records the Bible was translated into more than twenty dialects. These translations were mostly single books but some of them were NT or the whole Bible. Some of the versions in these dialects were printed with Chinese characters, others in Romanised script (Pinyin), National Phonetic script or Wang-Peill Phonetic script and some in both scripts.Footnote 42 Baptists contributed to this work.

However, after the publication of CUV as the common version in the early twentieth century, most of the dialect versions Bibles had disappeared. It was the same with the Baptist editions.

The following is a description of the Bible translations in different dialects by the Baptist missionaries in the chronological order of their publication.

(1) Shanghai Colloquial

Shanghai colloquial belongs to the Wu group of languages which are spoken in the provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang, and the municipality of Shanghai. In 1842, the Treaty of Nanking allowed the British to open treaty ports for international trade. Shanghai was one of these ports. It was a magnet for missionaries who came to Shanghai and the first translation into this Chinese dialect was published several years later.Footnote 43 The first one was the Gospel of St John by Medhurst in 1847 and it was also the earliest Bible version in a Chinese dialect.

In 1859, Cleveland Keith (1827–1862), a missionary from American Protestant Episcopal Mission (APEM), translated and published The Gospel of Luke in Romanised script. In the same year, A. B. Cabaniss (1853–1859 in China), a missionary from American Southern Baptist Mission (ASBM), transcribed this version into a special phonetic system and gave it the title Loo Ka Zen Foh Yung Zu (路加真福音書; Lù Jiā Zhēn Fú Yīn Shū).Footnote 44 This phonetic system was designed by another ASBM missionary Tarleton Perry Crawford (1821–1902) and named Shàng Hǎi Tǔ Yīn Zì (上海土音字; which literally means “Local accent word of Shanghai”). It was the only Baptist translation published in Shanghai colloquial.

(2) Ningpo colloquial

Another dialect belonging to the Wu languages group was Ningpo colloquial (now known as Ningbo colloquial), which was spoken in and around Ningpo, northeastern Chekiang Province in China. Editions in this dialect were generally in Romanised script,Footnote 45 but there was also a Chinese character edition which was mainly prepared by ABMU missionary Horace Jenkins. Horace Jenkins and his wife arrived in Ningpo in 1860. They worked there until 1869 before they were transferred to the station at Shaohsing (now Shaoxing). From 1894 to 1903, Horace Jenkins translated and published almost every NT books in this dialect.Footnote 46

(3) Kinhwa colloquial

Kinkwa colloquial was also a Wu dialect used in the Kinhwa area of central Chekiang province. There was only one book of the Bible translated in this dialect.Footnote 47 In 1866, Horace Jenkins from ABMU translated St John Gospel in Romanised script into this dialect and published in Ningpo.Footnote 48

Fig. 7. The Gospel of Luke by A. B. Cabaniss in 1859. This was the Bible in Shanghai colloquial with the phonetics system by the Baptists. (Used by Permission of the Bible Society Collection, Cambridge University Library.)

(4) Cantonese

Cantonese is the chief dialect of Kwangtung (now Guangdong) in China, Hong Kong, Macau, parts of Southeast Asia and by overseas Chinese whose ancestry can be traced to the Guangdong region. There were no translations into Cantonese by the Baptist missionaries.Footnote 49 However, there was a tentative edition from Galatians to Philemon in 1872 which was translated by George Piercy (1829–1913), a missionary from English Wesleyan Mission, while Timothy I of this version was based on a translation made by R. H. Graves, a Baptist missionary from the ASBM since 1855.

(5) Swatow colloquial

Swatow colloquial is the Min dialect spoken in and around Swatow (now Shantou) in East Kwangtung (now Guangdong) province. The Bible in Swatow colloquial had different versions in both Romanised script and Chinese characters.Footnote 50 The latter one was mainly done by the American Baptist missionaries and was based on the translation by Josiah Goddard and Edward C. Lord. In 1875, a Baptist medical missionary S. B. Partridge (1837–1912) translated the Book of Ruth. It was the first edition in Chinese characters. In the following twenty years, other editions were published by Partridge, Adele M. Fielde (1839–1916) and other ABMU missionaries, such as William Ashmore (1824–1909) and his son William Ashmore Jr. (1851–1937). In 1898, the NT was finally published.Footnote 51 This NT edition was revised by William Ashmore Jr. in 1922 as his final work in China.

Fig. 8. The Gospel of John in Ningpo colloquial by Horace Jenkins in 1897. (Used by Permission of the Bible Society Collection, Cambridge University Library.)

(6) Hakka colloquial

In the Chinese language ‘Hakka’ means strangers or guests. Unlike other Han Chinese groups, the Hakkas are not named after a geographical region. ‘Hakka’ usually refers to people who are from the cultural group of the Han Chinese in several provinces across southern China, mostly in Kwangtung (now Guangdong) province and Taiwan.Footnote 52

Only two known translations in Hakka were prepared by the Baptist missionaries. The first one was Gospels and Acts, both in Chinese characters, which was published by the China Baptist Publication Society in 1905. This version was based on the Cantonese Colloquial version by E. Z. Simmons (1846–1912), an ASBM missionary in Canton, with the help from Chinese helper Hoh Kap-shu. It was used by the Baptist mission in the district north of Canton between the north and east rivers. Another Baptist edition in Hakka colloquial was an NT version with colored illustrations published in 1917.

Fig. 9. The Gospel of John in Kinhwa colloquial by Horace Jenkins in 1866. (Used by Permission of the Bible Society Collection, Cambridge University Library.)

(7) Kiaotung colloquial

Kiaotung is the North Mandarin dialect spoken in eastern Shantung Province, the southeast of Beijing. Mandarin, also known as Putonghua or Guoyu in Chinese, is the group of dialects spoken in northern and southwestern China and is the most commonly spoken language in China. There were several Mandarin dialects which the Bible was translated into, but Kaiotung colloquial version was the only one done by the Baptist missionaries.Footnote 53

Two books of the Bible were translated at the request of the American Presbyterian and Baptist missions (North China Baptist Mission of the Southern Baptist Convention). The first one was St Mark's Gospel translated by the Baptist missionaries in 1918.Footnote 54 The other was St Matthew's Gospel in 1920 by both Presbyterian and Baptist missionaries in cooperation. Both used phonetic system but were in different scripts. St Mark's Gospel was written in the Wang-Peill Phonetic script while St Matthew's Gospel was written in Pinyin.

Fig. 10. The New Testament edition in Swatow colloquial by the Baptist missionaries in 1898. (Used by Permission of the Bible Society Collection, Cambridge University Library.)

(VII) Conclusion

Protestant missionaries in China repeatedly stressed the importance of Bible translation and Christian literature in their missionary endeavours. However, what was the purpose of translating Bible into Chinese? At a conference reviewing Bible translation in China, John C. Gibson (1849–1919), an English Presbyterian Mission (EPM) missionary from Swatow, pointed out the purpose of translation to the General Conference of Protestant Missionaries (GCPM) of 1890:Footnote 55

A translation may be for either one of two purposes:

Either (1) To give a substantially faith presentation of the thoughts of Scripture to non-Christian readers, either with a direct view to their enlightenment and conversion, or for general apologetic purposes.

Or (2) To supply Christian readers with as faithful a text as can possibly be given, to form the basis for a minute and loving study of the niceties of expression, and the minutiæ of distinctively Christian thought.

Gibson mentioned that the translation of Bible had two purposes: evangelical preaching and educational equipping. Obviously, Baptists’ translations of the Bible were concerned more about the second purpose. The Baptists placed their focuses on expressing the original source language faithfully. At the same time, their Bible translations included commentaries alongside the biblical texts. These commentaries explained the meaning of Scripture so as to make the Bible texts understandable to non-Christians.

Fig. 11. St Mark's Gospel in Kiaotung colloquial by the Baptist missionaries in 1918. This edition was prepared in the Peill Phonetic script. (Used by Permission of the Bible Society Collection, Cambridge University Library.)

In the principle of Bible translation, the Baptists particularly emphasised faithfulness to the original (Hebrew and Greek) texts, especially according to their religious tradition. For example, they inclined to translate “YHWH” on the principle of transliteration because they thought that this Tetragrammaton could not be translated in Chinese perfectly. Another more controversial argument was the translation of ‘baptizō’. The Baptists insisted on using a translation which could clearly express the meaning of ‘immersion baptism’. It can be estimated that their translation was not accepted by other denominations.

After the 1870s, there was no more Baptist translation of the Bible in classical Chinese or Mandarin. Baptist translations only appeared in some dialects. Few translators with a Baptist background were involved in the translation work of CUV at the end of the nineteenth century and there was no more significant achievement. However, the Baptists’ contribution to the Chinese Bible translation, even for a short time, is still worth remembering.

Appendix

Overview of Protestant Chinese Bible Versions in Common Languages and Local Dialects