1. Introduction

A prevailing view about stratarchically organized political parties is that grassroots membership associations are atomized, isolated and autonomous (Eldersveld, Reference Eldersveld1964; Katz and Mair, Reference Katz and Mair1995: 21; Carty, Reference Carty2004; Bolleyer, Reference Bolleyer2012; McGraw, Reference McGraw2018). Although some are beginning to challenge this conceptualization (Cross, Reference Cross2018), party scholars in Anglo parliamentary democracies typically view mutual autonomy between principal levels of the party as a mechanism for “aggregating, rather than articulating” (Carty, Reference Carty2002: 726) a national interest that would otherwise fracture along representational cleavages such as language, religion or region (Carty, Reference Carty2002; Carty and Cross, Reference Carty and Cross2006; McGraw, Reference McGraw2018). R. Kenneth Carty (Reference Carty2002) describes this stratarchical arrangement in his franchise model of party organization. Local party associations embedded inside single-member electoral districts execute essential functions of personnel selection and constituency campaigning, whereas the central party apparatus at the national level—comprising the parliamentary caucus, its leader and their advisers—develops party policy, constructs the party brand and encourages compliance on the ground. Under this stratarchical arrangement, party leadership has a remarkably high degree of control over the national party, while at the same time, grassroots activists have sufficient autonomy to adapt the party to idiosyncratic features of each electoral district (Sayers, Reference Sayers1999; Cross and Young, Reference Cross and Young2011; McGraw, Reference McGraw2018).

An additional factor that encourages local autonomy in Canadian parties is electoral volatility. The majoritarian electoral system and regionalized electorate are notorious for distorting election results (Cairns, Reference Cairns1968; Young and Archer, Reference Young and Archer2002; Johnston, Reference Johnston2017). By concentrating exclusively on campaign tasks in their own riding, local party organizations attempt to withstand (or harness) modest swings in party vote share at the regional or national level in pursuit of electing their own candidate (Sayers, Reference Sayers1999; Cross, Reference Cross2016). Constituency campaigning effectively becomes “a parochial contest managed by local partisans designed to recruit a candidate and mobilize the votes” (Carty, Reference Carty2002: 724). Indeed, evidence from Canada and other single-member district electoral systems demonstrates that when local party organizations require additional support, it originates from the central office at the national level instead of constituency associations in other districts (Denver et al., Reference Denver, Hands, Fisher and McAllister2003; Carty and Eagles, Reference Carty and Eagles2005; Coletto et al., Reference Coletto, Jansen and Young2011).

Scholars have warned that party finance reforms implemented in Canada at the beginning of the twenty-first century may enhance the fiscal power of national party offices, thereby modifying the franchise model supported by semi-autonomous local party organizations (Coletto et al., Reference Coletto, Jansen and Young2011; Young and Jansen, Reference Young and Jansen2011; Carty and Young, Reference Carty and Young2012; Carty, Reference Carty2015). Building on this research, I investigate the financial composition of Canadian political parties during the 2008 and 2011 election years. Elections Canada financial reports reveal that constituency party associations—legally defined as electoral district associations (EDAs) and commonly referred to as riding associations, and referenced by any of these terms throughout this article—were sending money to riding associations and candidates in other ridings. If constituency associations are autonomous from each other and tasked with activities meant to “deliver the votes needed for electoral success” in each district (Carty, Reference Carty2002: 734), then why would one membership association transfer money to another, especially when it does nothing to support the election of the local candidate? In other words, what are the conditions that encourage constituency parties to send a higher percentage of their total spending to EDAs and candidates in other ridings?

I begin to address this question using an original dataset of constituency association financial behaviour for Canada's three largest parties. The findings reveal that riding transfers primarily occur inside the new Conservative Party of Canada. Roughly one-third of Conservative party riding associations sent money to other EDAs or candidates. Furthermore, the money being sent from Conservative riding associations reflects the grassroots organizational capacity of its legacy party, the Canadian Alliance. Nearly half of the money sent in 2008 originated in Alberta alone. Finally, riding transfers do not appear to be a mechanism for funnelling money from the national party, as one might expect following the “In and Out” scandal during the 2006 federal election, nor are they primarily a device for elevating the profile of leadership aspirants. Instead, Tobit regression analysis points toward centralized coordination, as riding associations are most likely to send money to other ridings when they are in uncompetitive districts and have a surplus of cash.

Evidence of horizontal linkages between constituency associations reveals that some parties can leverage their regional base of support into a national presence. Other party resources, such as votes and volunteers, are confined within the boundaries of federal electoral districts. Money, however, is a fungible commodity that can be easily raised in one voting district and spent on campaign materials in another. The case of the reunited Conservative party illustrates this point. The pan-Canadian party system collapsed into highly regionalized patterns of inter-party competition, in part due to the emergence of the Reform party in 1993 (Carty et al., Reference Carty, Cross and Young2000: 1; Flanagan, Reference Flanagan2009a). However, Reform never managed to grow beyond its regional stronghold in western Canada. The Canadian Alliance (a rebranded version of Reform) eventually merged with the Progressive Conservative party in 2003 because it could not escape its legacy as a regional protest party (Flanagan, Reference Flanagan2009b). Despite replacing the Liberal government soon after its formation, the new Conservative party experienced ongoing challenges expanding into the same regions that had been an electoral “wasteland” for its predecessor (Carty and Eagles, Reference Carty and Eagles2005: 155, 166); it took five years, two more federal elections and the narrow defeat of an unprecedented coalition agreement for the Conservatives to finally form a majority government in 2011 (Russell and Sossin, Reference Russell and Sossin2009; Young and Jansen, Reference Young and Jansen2011). The money raised by Conservative riding associations in the west, especially Alberta, appears to have been redirected into voting districts across Canada that required additional mobilization support. In this view, the linkages that developed between Conservative riding associations facilitated the national growth of a regional party.

2. Local Party Organizations and the Canadian Party Finance Regime

Local party organizations are composed of two discrete entities that traditionally focus on partisan activities in their own electoral district. Constituency party associations (that is, EDAs) make up the first entity and sustain partisan life between election campaigns. These associations are often managed by long-time members (Koop, Reference Koop2010), have varying organizational capacities (Carty, Reference Carty1991; Coletto and Eagles, Reference Coletto, Eagles, Young and J2011) and nominate the candidates who run under the party banner in general elections. Sayers (Reference Sayers1999) argues that the relative autonomy of constituency associations emerges from the political ecology of each voting district, the size of the association and its ideological distance from the national party. The interaction of these factors influences the openness of the candidate nomination process, which in turn shapes candidate quality and control over the local campaign. Quantitative research has confirmed key aspects of Sayers’ model (Carty et al., Reference Carty, Eagles and Sayers2003; Carty and Eagles, Reference Carty and Eagles2005; Cross and Young, Reference Cross and Young2011; Sayers, Reference Sayers, Bittner and Koop2013; McGraw, Reference McGraw2018). If we carry these findings forward, it is possible that constituency associations develop horizontal linkages to other local associations for similar reasons: mainly, durable party support stability, larger association size and smaller ideological distance from the national party.

Candidates, who are typically nominated by party members through the EDA (Thomas and Bodet, Reference Thomas and Bodet2013; Cross, Reference Cross2016; Tolley, Reference Tolley2019), make up the second entity of local party organizations. Once nominated, candidates take control of electoral district association resources for the constituency campaign. Some constituency associations have withheld support from local candidates, especially in instances when the national office is overly intrusive in the nomination process (Carty and Eagles, Reference Carty and Eagles2005: 50–51), although such instances are rare. Quantitative research demonstrates that candidate quality is positively correlated to constituency association fundraising and volunteer strength (Carty and Eagles, Reference Carty and Eagles2005; Cross and Young, Reference Cross and Young2011). It also shows that local campaign spending is less effective for incumbents than challengers (Johnston and Pattie, Reference Johnston and Pattie2006). Rather than potentially throw good money after bad, riding associations with incumbent candidates could transfer a larger portion of their total spending to challengers where the money will be more effective.

Despite these possible explanations for riding transfers, horizontal linkages between constituency associations are rare. A survey of riding association presidents from 1988 suggests that, at most, one in ten EDAs transferred money to other ridings (Carty, Reference Carty1991: 212). When linkages do develop, it is the form of robust vertical integration between federal and provincial parties at the constituency level. Koop (Reference Koop2011) finds that federal riding associations may rely on their provincial counterparts when the national office is unable to provide material support, as shown in the Liberal party between 2006 and 2009. Similarly, Pruysers (Reference Pruysers2014) documents informal vertical integrationwhen members participate in federal and provincial parties simultaneously. Given that federal and provincial constituency associations may integrate their organizations inside electoral district boundaries, it is also theoretically possible for local associations in the same party to develop linkages across ridings and potentially integrate with other EDAs. The scarcity of such linkages could be attributed to the limited number of safe seats in Canada and the historical absence of larger, ideologically driven parties (see Carty et al., Reference Carty, Cross and Young2000; Carty, Reference Carty, Bittner and Koop2013).

Linkages between constituency associations and national party offices are far more prevalent. For much of the twentieth century, national party offices experienced fundraising cycles tied to election years and remained heavily indebted in between (Paltiel, Reference Paltiel1970; Stanbury, Reference Stanbury1991). Election laws implemented in 1974 marginally improved matters by creating (among other things) expense reimbursements for candidates (50 per cent of spending), expense reimbursements for the national office (22.5 per cent of spending) and spending limits for candidates and national campaigns. However, national offices continued to experience large financial shortages. One strategist lamented that under the 1974 party finance regime, “the Liberal Party of Canada is millions of dollars in debt at the national level but has a number of riding [associations] across the country which could finance the next four or five federal elections” (Davey, Reference Davey1986: 197). This anecdote is supported by research that shows local candidates as a group generating a sum of $9.6 million from the expense reimbursement in 1988 (Stanbury, Reference Stanbury1991: 76).

Instead of letting money accumulate on the ground, some parties have required candidates to transfer a portion of the reimbursement back to the national office. The Liberal party, for instance, once required candidates to return 50 per cent of their spending reimbursement before the leader would approve their nomination (Cross, Reference Cross2004: 160). The full extent to which constituency associations were also taxed is difficult to know because they did not become legal entities until 2004, although a survey of riding association presidents suggests that some EDAs also transferred money back to Ottawa (Carty, Reference Carty1991: 77). The upward flow of money is logical not only because local campaigns benefit from a viable national campaign but also because monetary resources might otherwise accumulate in ridings where they are not needed.

The party finance regime was modified in 2004 and 2006, potentially reversing the flow of money between local party organizations and national party offices. The income from corporations and trade union donations that had sustained parties since confederation (Paltiel, Reference Paltiel1970; Stanbury, Reference Stanbury1991) was completely banned by 2006. Parliamentarians replaced this lost income through a generous $1.75 per-vote subsidy paid directly to national party offices. The new subsidy created a predictable source of income for national party offices and improved their operational capacity (Flanagan and Jansen, Reference Flanagan, Jansen and H2009), although no subvention was created for local candidates or constituency associations. At the same time, legislative reforms drastically limited how much money national party offices, constituency associations and local candidates could raise from private sources. The individual contribution limit was set at $5,000 by the Liberal government in 2004 and then lowered to $1,000 by the new Conservative government in 2006 (Young and Jansen, Reference Young and Jansen2011; Young, Reference Young, Gagnon and Tanguay2017).Footnote 1

Party scholars have warned that this type of party finance regime may concentrate power at the centre of political parties (Katz and Mair, Reference Katz and Mair1995; Coletto et al., Reference Coletto, Jansen and Young2011; Young and Jansen, Reference Young and Jansen2011). From a fiscal perspective, local party organizations decline in importance because national offices receive income directly from the state and, in the Canadian case, possess the economies of scale necessary for fundraising millions of dollars from tens of thousands of donors (Young, Reference Young, Gagnon and Tanguay2017). After the 2006 federal election, for instance, Elections Canada discovered that the Conservative party national office transferred money to local candidates in order to circumvent national campaign spending limits. The “In and Out” scandal included 67 candidates who were charged in violation of the Canada Elections Act. The case was dropped when the Conservative party agreed to pay a $52,000 fine (Payton, Reference Payton2011). As this example illustrates, “the election finance regime itself is increasingly advantaging national as opposed to local party activity. . . . [The Conservatives] have pushed the system further by developing institutional mechanisms that allowed its national campaign organization to cannibalize unused local spending space” (Carty and Young, Reference Carty and Young2012: 235).

Concerns about centralization inside Canadian political parties, while credible, overlook the potential for constituency associations to also provide fiscal support to others located in strategically important ridings. Reforms to party finance law in 2004 and 2006 impose low contribution limits, but they also allow unlimited amounts of money to be transferred when not used to circumvent election spending limits (Canada Elections Act, 2000: sec. 364[3][4]). That is, fiscal resources can be freely transferred between the national party, local candidates and constituency associations, once those resources have been donated by individuals or transferred from the state. Excessive cash surpluses are pointless for local associations when election laws set maximum spending limits for candidates in each electoral district. This creates an additional incentive to distribute fiscal resources to other ridings. The next section outlines hypotheses for testing two possible explanations for riding transfers.

3. Hypotheses and Data

The literature on franchise parties, political party financing and constituency campaigning suggests that riding transfers may be the product of two related yet distinct sets of incentives. On the one hand, monetary transfers between constituency associations may be a nationally coordinated mechanism for utilizing fiscal resources most efficiently. According to this view, we should observe constituency associations sending higher amounts of money when they have more cash than is required for the local campaign. We should also expect riding transfers to be greater when the constituency association is situated in an electoral district that is highly supportive of the party. Lastly, riding transfers may be a mechanism for the national office to funnel money to strategically important districts. Given the legal ramifications of the “In and Out” scandal noted in the previous section, riding transfers may help distance the national office from the final recipient.

H1: Riding associations transfer a higher percentage of spending to local organizations in other districts when they have higher amounts of cash on hand.

H2: Riding associations transfer a higher percentage of spending to local organizations in other districts when they are situated in safe ridings that the local candidate is likely to win.

H3: Riding associations transfer a higher percentage of spending to local organizations in other districts when they receive a higher percentage of income from the national party office.

On the other hand, money transfers between constituency associations may be a mechanism for enterprising politicians to enhance their clout inside the party. In this scenario, we should expect constituency associations to transfer a greater share of their total spending when they are represented by a candidate inside the parliamentary caucus (that is, incumbents). Similarly, we should expect to find larger transfers when the candidate is also a member of cabinet. Cabinet ministers have much more to gain by ensuring the party is re-elected to government; it enhances their prospects for remaining in the executive branch and helps build support among party members located in other regions of the country. We should expect to find that constituency associations represented by contestants who ultimately ran for party leadership to have sent larger transfers than those who did not.

H4: Riding associations transfer a higher percentage of spending to local organizations in other districts when they have a candidate who is also an incumbent.

H5: Riding associations transfer a higher percentage of spending to local organizations in other districts when they have a candidate who is also a member of cabinet.

H6: Riding associations transfer a higher percentage of spending to local organizations in other districts when they have a candidate who ran for party leadership.

In order to test these hypotheses, data were collected for the Conservative party (CPC), Liberal party (LPC) and New Democratic party (NDP). Financial data were gathered for the 2008 and 2011 election years in order to extend the period of analysis from existing research (Coletto and Eagles, Reference Coletto, Eagles, Young and J2011; Coletto et al., Reference Coletto, Jansen and Young2011). Data were captured from registered party associationFootnote 2 (that is, EDA) financial reports and candidate campaign returns,Footnote 3 as reviewed by Elections Canada (Reference Elections Canada2019).Footnote 4 Variables were captured for annual contributions to the EDA from individuals, association and candidate spending and intra-party money transfers. The transfers include monetary transfers between riding associations and candidates, as well as the national office.Footnote 5 The final dataset contains the population of constituency party associations for the three largest parties in the 2008 and 2011 election years (N = 1,848).

Non-financial data were assembled from several online sources. Data for incumbency were collected from the Pundits' Guide to Canadian Elections (Funke, Reference Funke2015), and their reliability was verified by comparing them to Sevi and colleagues’ (Reference Sevi, Yoshinaka and Blais2018, Reference Sevi, Arel-Bundock and Blais2019) candidate dataset.Footnote 6 Similarly, data for members of cabinet immediately before the election campaign were gathered from the Parliament of Canada website (Canada, Parliament, 2019) and media reports (CBC News, 2007, 2008, 2011). A variable for contestants who entered the 2017 Conservative party leadership race was captured by pairing Elections Canada contest details with the list of confirmed candidates for the 2008 and 2011 federal elections.

Party competitiveness at the district level is operationalized using Bodet's (Reference Bodet2013) “stronghold” and “battleground” measures. In essence, a stronghold riding is observed when the highest ranking party receives a vote share that is greater than or equal to the smallest winning plurality in any district, has smaller changes in vote from the previous election, and no other party in the riding satisfies these conditions (Bodet, Reference Bodet2013: 584).Footnote 7 Battleground ridings are ones in which any one of these three conditions does not apply. As Thomas and Bodet (Reference Thomas and Bodet2013) show in their study of women being disproportionately nominated as candidates in uncompetitive ridings, the stronghold/battleground classification is more reliable than margin of victory/margin of loss because it captures party support stability over time. We can also use this measure to capture party-specific strongholds in a multiparty system.

Financial variables are calculated to capture their relative importance to other sources of revenue or expenses. The dependent variable is percentage of total spending that one constituency association transfers to associations and candidates in other ridings. Riding transfers are calculated by dividing the sum of money sent to EDAs and candidates in other ridings by the total spending of the sending association.Footnote 8 For example, the Conservative association in Laurier–Sainte-Marie (Montreal, QC) spent $79,466.15 in 2008: of that, $45,091.15 was spent on professional services, office expenses and other incidentals before the election began, while $34,375.00 was transferred to 18 EDAs and candidates in other ridings throughout Quebec. The dependent variable for this case is 43.3 per cent.

Explanatory variables are also calculated to express the relative importance of other sources of income. The percentage of money transferred to local candidates in the same riding is calculated the same way as riding transfers sent outside of the district. The variable measuring the percentage of income received from the national office is calculated by dividing income from party headquarters by total income, a composite variable of the sum of individual contributions, the EDA's opening balance (that is, savings), transfers received from the national party office and transfers received from other EDAs and candidates. The Conservative association in Vancouver Kingsway had a total income of $69,070.93 in 2008, including $11,645 raised from individuals, $16,443.30 in savings, $1,607 received from the national party office and $39,375.63 received from four Conservative riding associations from the greater Vancouver area and interior of British Columbia. The variable “EDA income from Party HQ” is 2.3 per cent for this case. A measure for the percentage of candidate income from the national office is calculated similarly.

Finally, the explanatory variable “Cash on Hand” is calculated by subtracting EDA cash on hand (individual contributions plus savings) from the Elections Canada district expense limit, then dividing that coefficient by the district expense limit. Values between negative one and zero indicate that the EDA has some cash on hand but not 100 per cent of the district expense limit. Values greater than zero mean that EDAs have more cash than the legal spending limit in their riding, whereas values less than negative one indicate that riding associations were indebted. The next section reports the findings from these data.

4. Results

Riding transfers are not a major expense for the population of constituency associations. Table 1 reports the average riding transfers for each party, and they range from as little as $24.48 in the New Democratic party to as much as $6,479.59 in the Conservative party. However, the Conservative party stands out as a case where monetary transfers between ridings involve more than just sharing costs for barbecues and volunteer events. Instead, riding transfers in the new Conservative party appear to be part of a broader mobilization strategy.

Table 1 Riding-to-Riding Transfers by Party and Year

Note: National/local = central party income received by EDAs divided by inter-riding transfers sent from EDAs. N = 308 for each party during each year.

First, Conservative riding associations spent between 5.9 and 7.9 per cent of their annual spending on riding transfers. The Liberals and New Democrats, in contrast, spent as much as 1.2 and 0.5 per cent, respectively. Second, Conservative riding associations transferred almost as much money to other EDAs as did the national party. In 2011, Conservative associations transferred slightly more money to other EDAs than was distributed from the centre. Liberal and New Democratic party associations, on the other hand, relied much more on transfers from party headquarters. For instance, the New Democrats reached an upper limit of 46 dollars sent from the national office for every dollar sent from constituency associations in 2008. Third, the amount of money that Conservative EDAs sent to other ridings increased to nearly $2 million in 2011 from $1.2 million in 2008.

Riding transfers are unique to the Conservative party because of the astonishing amount of money that its constituency associations accumulated on the ground. Table 2 reports the cash available to constituency party associations. The data show relatively stable EDA income from individual contributions for all three parties across both election years, and Liberal party fundraising was comparable to the Conservatives during election years. Where we observe significant differences are EDA savings. The change is most consequential for the Conservative party when comparing it to district expense limits. Conservative EDAs accumulated 92.7 per cent of the permitted expenses for every riding across Canada by 2011, a stark contrast to the Liberals at 54.3 per cent and the New Democrats at 18.1 per cent. However, these fiscal resources are accumulated inside 308 individual riding associations and likely held in electoral districts where they are not as crucial for electing the local candidate.

Table 2 Riding Association Fundraising and Savings

Note: Cash/expense limit = ratio of contributions plus savings against the Elections Canada permitted expense limit. N = 308 for each party during each year.

Table 3 reports the regional distribution of riding transfers, as well as the number of associations in each province that sent at least one penny. Nearly one-third of the 308 constituency associations transferred money to other ridings. The sum of transfers also grew between election years. Riding transfers increased by $719,000 from the 2008 election year. In fact, the only province where transfers declined between the two periods was New Brunswick, but this was marginal.

Table 3 Riding Transfers in the Conservative Party by Province

Note: Values are reported in dollars for columns Sent and Received. The column Rec/Sent divides the total money received by total money sent for each province. N in parentheses.

Regional patterns of riding transfers correspond with where we would expect to find the largest accumulation of money inside the Conservative party. The bulk of the transfers were sent from constituency associations located in western Canada. In 2008, over 50 per cent of riding transfers originated in Alberta alone. The proportion of grassroots money leaving Alberta diminished in 2011 but only because the amounts transferred by constituency associations in other provinces increased. The largest benefactors of riding transfers were in Atlantic Canada. Apart from Nova Scotia in 2011, constituency associations in the Atlantic provinces received more than five times what they sent. Local associations in Atlantic Canada may have received less money than EDAs in Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia in terms of nominal dollars, but the much larger ratio suggests an infusion of money from outside the region. The regional pattern of riding transfers sent mirrors Flanagan's summary of the Canadian Alliance's grassroots organization: “strong in the West, Middling in Ontario, and very weak east of the Ottawa river” (Reference Flanagan, Thornburn and Whitehorn2001: 285).

More strikingly, the net-recipients of riding transfers do not appear to be correlated with the money that candidates receive directly from the national party. Data reported in Table 4 show that candidates in Atlantic Canada received essentially zero per cent of the transfers sent from party headquarters. These transfers went almost exclusively to candidates running in Quebec. The Conservative war room sent its Quebec candidates 86.5 per cent of the $2.8 million transferred in 2008 and 96 per cent of the $1.8 million transferred in 2011. While Liberal and New Democratic party war rooms distributed money to local candidates more proportionately across regions, the Conservatives appear to have adopted a bifurcated approach to mobilizing constituency campaigns: one for Quebec and another for the Rest of Canada. Mobilization efforts in the Rest of Canada are tied to riding transfers from constituency associations.

Table 4 National Party Transfers to Candidates by Province

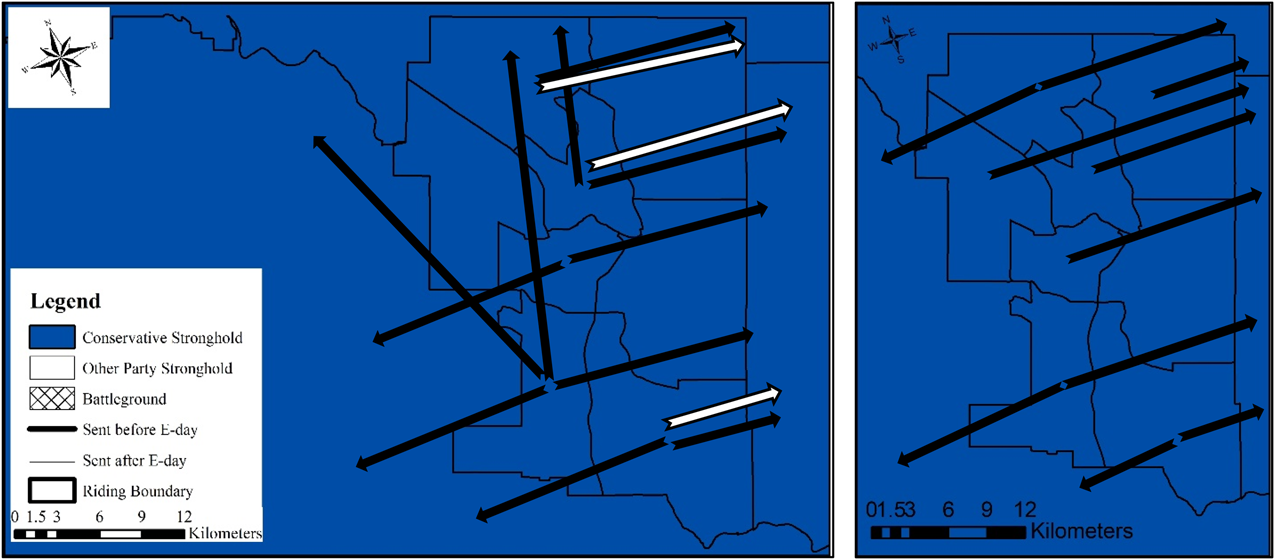

Of the top ten associations sending transfers in nominal dollars, five were located in Calgary, Alberta. The maps reported in Figure 1 illustrate a pattern of diffusion.Footnote 9 The approximately $400,000 transferred from Conservative EDAs in Calgary accounted for 31 per cent of total transfers in 2008 and 21 per cent in 2011. This includes the $200,000 sent from the Conservative association in Calgary Southwest (SW) in 2011, the $165,000 it sent in 2008, the $132,000 sent from Calgary Centre-North (CN) in 2008, the $101,677.22 sent from Calgary Southeast (SE) in 2011 and the $92,583.43 sent from Calgary Centre in 2011. The politicians elected to represent these constituencies include former prime minister Stephen Harper (SW), industry minister Jim Prentice (CN), and immigration minister Jason Kenney (SE). These cases are instructive because Calgary appears to be the epicentre of riding transfers, as if a contagion effect spread from the Conservative party bastion.

Figure 1 Patterns of Diffusion from Calgary, Alberta

The Calgary cases are also instructive because they underscore the potential for local candidates to influence riding transfers. The Calgary Southwest EDA received 60 per cent of what it had sent three riding associations in 2011, as if it was getting an equitable proportion of the recipient's spending reimbursement. In addition, notable declines to riding transfers are observed in only one of these three cases: Calgary Centre-North. Prentice did not seek re-election in 2011, and his former riding association transferred $117,000 less than what is sent in 2008. These examples, while anecdotal, illustrate that enterprising politicians also have incentives to transfer money and potentially expand their influence inside the party.

Only one association outside of western Canada made the top ten list in terms of nominal dollars sent. In 2011, the Conservative party in Laurier–Sainte-Marie transferred $92,583.43—nearly 80 per cent of its annual spending—to other ridings. Figure 2 reveals a similar pattern of diffusion to the one found in Calgary but on a much more local scale. The maps illustrate transfers greater than $1,000 being sent to the neighbouring ridings, such as Châteauguay, Honoré-Mercier and Westmount–Ville-Marie. What are not shown in the maps are the transfers sent beyond Montreal. The Conservative party in Laurier–Sainte-Marie sent an additional $13,000 to other local organizations inside Quebec in 2008 and over $59,000 in 2011.

Figure 2 Patterns of Diffusion in Montreal, Quebec

In contrast to the Calgary cases, the Conservative party was not viable in Laurier–Sainte-Marie. Conservative candidates in Laurier–Sainte-Marie only spent approximately 5 per cent of the expense limit in both election years, whereas candidates in Calgary spent between 41 and 93 per cent of the limit. The smaller amount of campaign effort reflects the fact that the Conservatives were uncompetitive in Laurier–Sainte-Marie; it was a Bloc Québécois stronghold that was represented by party leader Gilles Duceppe until 2011. Rather than potentially waste fiscal resources in challenging Duceppe, the Conservative association in Laurier–Sainte-Marie sent its money elsewhere.

The patterns of diffusion from uncompetitive districts are mirrored by patterns of infusion to recipient riding associations. When looking at Lower Mainland of British Columbia, for example, we observe an infusion of money into urban districts from the suburban/rural ridings. Figure 3 illustrates this pattern. Conservative associations in Abbotsford, Langley, North Vancouver and South Surrey–White Rock–Cloverdale transferred a portion of their fiscal resources to the mostly urban ridings of Burnaby–Douglas, New Westminster–Coquitlam, Surrey North, Vancouver East and Vancouver Kingsway. This pattern of infusion indicates that riding transfers can also be a component of regional campaign strategies. The fiscal resources being redirected into urban ridings in Vancouver likely helped the associations sending money, given that voters may live in one constituency but work or participate in community organizations in another. Building up the organizational capacity of campaigns in neighbouring ridings may help bolster electoral support at home.

Figure 3 Patterns of Infusion in Vancouver, British Columbia

The final step is to analyze riding transfers using multiple regression analysis. Tobit regression is reported here because the dependent variable—the percentage of total spending that one constituency association transfers to EDAs and candidates in other ridings—contains a disproportionately large number of cases at the lower limit of zero.Footnote 10 The Tobit regression model overcomes this issue by estimating latent values for left-censored cases (McDonald and Moffitt, Reference McDonald and Moffitt1980). The marginal effects are reported alongside the latent regression coefficients in Table 5. Readers can interpret the marginal effects as the conditional means of riding transfers when the observed dependent variable is greater than zero. Riding transfers are modelled in two phases. The first model is restricted to Conservative party strongholds. The second model contains the population of cases. This modelling technique allows us to compare differences between riding associations in districts with durable support stability versus the entire population of cases. The online appendix reports an ordinary least square (OLS) regression model that produces similar findings.

Table 5 Tobit Regression of Riding Transfers in the Conservative Party of Canada

Note: Standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered within province. Conservative stronghold is the reference category for district competitiveness.

*p ≤ .10; **p ≤ .05; ***p ≤ .01

The Tobit model in Table 5 reveals that the single most important factor for sending riding transfers is cash on hand. For a literal interpretation, constituency associations that transfer at least one penny send 3 to 5.7 per cent more for each additional increase of cash on hand standardized to the district expense limit. These marginal effects are significant in the Tobit models during both election years and also replicated by the OLS model (see online appendix). This confirms that (H1) riding associations transfer a higher proportion of their spending when they have a surplus of cash. There is mixed evidence that riding transfers are a mechanism for diverting national party income through local associations. Riding transfers are positively correlated to receiving money from the national office when analysis is restricted to Conservative strongholds; however, this relationship inverts in the full model. Similarly, candidates in ridings where the local association sent money away received a higher proportion of their income from the national office in 2008 but less in 2011. Given the discrepencies between election years, these findings fail to confirm H2 and H3.

Similarly, the Tobit analysis does not support the notion that riding transfers are directly connected to enterprising politicians. In Conservative strongholds, for example, riding transfers are positively correlated to EDAs with cabinet ministers; however, the conditional mean is only significant in 2008. The correlation also reverses in 2011 for the full model. Constituency associations with incumbents, in contrast, transferred less money than those without incumbents in 2008 but more in 2011, a pattern that holds in both models and is statistically significant in 2011. Perhaps most telling, local associations with candidates who entered the 2017 leadership race transferred less money than those without leadership aspirants during both election years. Even though riding associations with high-profile ministers such as Stephen Harper, Jason Kenney and Jim Prentice made sizeable transfers, as reported in Figure 1, it is more likely that they did so because their EDAs had more money than was needed to re-elect their incumbents. These findings, as a whole, do not confirm the expectations (H4, H5, H6) that riding transfers are primarily a mechanism for leadership aspirants to build support inside the party.

With respect to district competitiveness, riding associations in other party strongholds sent less money than those in safe districts in 2008. Again, this relationship inverts in 2011, as there is a positive (albeit marginal and insignificant) relationship. The exception to this was for local associations in Bloc Québécois strongholds in 2011. As suggested by Figure 2, a significant amount of money exited local associations in some of these other party strongholds. The higher proportion of spending from Bloc strongholds suggests that constituency party associations can independently recognize that spending their money at home will do little to transform votes into an additional parliamentary seat. They may field a candidate and potentially give them some money, but as the example of the Conservative party in Laurier–Sainte-Marie suggests, the riding executive can choose to provide substantially more financial support to candidates in other voting districts. Although the data do not distinguish transfers sent before or after the election day, it is also possible that EDAs in other party strongholds were returning money that was loaned.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Evidence of horizontal linkages between constituency associations demonstrates that local party associations are not always atomized or isolated within the geographic boundaries of their electoral districts. While not prevalent in all parties, linkages between constituency associations contribute to the emerging literature on party stratarchy that portrays a much more complex power-sharing arrangement than the traditional notion of mutual autonomy (see Cross, Reference Cross2018). The Conservative Party of Canada has similar organizational arrangements to an archetypal franchise party, the Liberal Party of Canada (Carty, Reference Carty2015), including centralized control over policy development and decentralized control over personnel selection (Flanagan, Reference Flanagan2009b: 153–54; Reference Flanagan, Farney and Rayside2013). However, the Conservative party maintains an ideological coherence that the Liberal party does not. Rooted in the Reform party's opposition to elite-brokerage (Flanagan, Reference Flanagan2009a), traces of the Conservative party's ideological distinction are found in voter attitudes (Sayers and Denemark, Reference Sayers and Denemark2014; Stewart and Sayers, Reference Stewart, Sayers, Johnston and Sharman2015) and, presumably, the ideologically driven members that were grandfathered in from the Canadian Alliance (see Cross and Young, Reference Cross and Young2002).

The relatively stronger ideological coherence of the new Conservative party gives the impression that it is more centralized than franchise parties practising elite-brokerage politics (see Carty, Reference Carty, Bittner and Koop2013: 18). Data reported in this article support this view. Conservative riding associations located in uncompetitive electoral districts and endowed with excessive amounts of cash participated in a national effort to build the capacity of local party organizations in other regions of the country. The data suggest that riding transfers originated via party leadership in Calgary, Alberta. It is difficult to accept an alternative explanation, given that riding associations represented by party leadership were among the top ten sending associations, 31 per cent of $1.2 million sent in 2008 originated in Calgary alone, and only 13.5 to 4 per cent of the money sent from the Conservative war room went to local candidates outside of Quebec. These data points support the explanation that riding transfers are a centrally coordinated mechanism for mobilizing party resources otherwise siloed off in one region.

At the same time, transferring money directly between constituency associations is consistent with Reform's membership-driven organizational model. Instead of taxing local associations and then distributing money from the centre, as the Liberal party has done in the past, the Conservative party moves money directly between grassroots membership associations. These linkages are undoutably less robust than formal or informal measures of integration, yet they demonstrate the ability for local associations in one constituency to provide material support to other partisans on the ground. The localized patterns of diffusion and infusion, along with the possibility of sending money as loans, suggest that control over fiscal resources is not a zero-sum game. Local party organizations benefit when neighbouring campaigns appear viable, or when the national party forms government, and may ultimately decide where money is sent. While beyond the scope of this article, future research should specify the mechanism of riding transfers and attempt to capture other types of linkages between constituency associations.

Concerns that campaign finance reforms made in 2004 and 2006 would centralize Canadian political parties were somewhat justified. In addition to the linkages that formed between constituency associations in the Conservative party, financial data show that income from the national party was increasingly important for other major parties in 2008 and 2011. This reached a pinnacle in the Liberal party, which transferred $4.9 million to local party organizations in 2011. However, this article demonstrates that legislative reforms are moderated through party organizations. Subsequent amendments to party finance laws in 2014 have constrained the amount of money within parties further by ending the per-vote subsidy paid to national offices (Young, Reference Young, Gagnon and Tanguay2017). Riding transfers may become an important source of income for constituency associations as all parties respond to new legal constraints.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423920000360.

Acknowledgments

Research for this article began as a Master of Arts thesis at the University of Calgary. Special thanks to Anthony Sayers, David Stewart and Melanee Thomas for their feedback and guidance. I also wish to thank Bill Cross, Steve White, Scott Pruysers, Paul Thomas, Derek Mikola and the journal's three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.