Substance use disorder (SUD) is a pathological cluster of cognitive, behavioural, and physiological symptoms stemming from compulsive use of a substance despite adverse effects on psychosocial functioning (American Psychological Association, 2013). Between 30% and 80% of individuals presenting for the treatment of SUDs experience some form of cognitive impairment (CI; Copersino et al., Reference Copersino, Fals-Stewart, Fitzmaurice, Schretlen, Sokoloff and Weiss2009), with neurophysiological changes occurring as a result of intoxication, withdrawal, or chronic use. Substance users frequently demonstrate deficits in attention, memory, executive functions, and decision-making (Ramey & Regier, 2020), with nature and chronicity of impairment differing between types of substances, quantity, and frequency of use (Bruijnen et al., Reference Bruijnen, Jansen, Dijkstra, Walvoort, Lugtmeijer, Markus and Kessels2019; Chen, Strain, Crum, & Mojtabai, Reference Chen, Strain, Crum and Mojtabai2013).

CI may also result from other comorbid factors. Psychiatric illness is highly prevalent in individuals with SUD (Gould, Reference Gould2010; Kelly & Daley, Reference Kelly and Daley2013) and can increase severity of health issues and complicate recovery (Daley & Moss, 2002; Grella, Hser, Joshi, & Rounds-Bryant, Reference Grella, Hser, Joshi and Rounds-Bryant2001). Other common comorbidities that can impact cognition include physical illness, such as vascular conditions (Volkow, Baler, Compton, & Weiss, Reference Volkow, Baler, Compton and Weiss2014), respiratory problems (Owen, Sutter & Albertson, Reference Owen, Sutter and Albertson2014), and liver damage (Brodersen et al., Reference Brodersen, Koen, Ponte, Sánchez, Segal, Chiapella and Lemberg2014). Between 37% and 66% of individuals with an acquired brain injury (ABI, e.g., due to falls, head trauma, overdose, or chronic substance use; Ridley et al., Reference Ridley, Batchelor, Draper, Demirkol, Lintzeris and Withall2018) misuse alcohol, and 10%–44% use illicit substances (Parry-Jones, Vaughan, & Miles Cox, Reference Parry-Jones, Vaughan and Miles Cox2006), suggesting potential cumulative cognitive dysfunction. Developmental disorders (e.g., intellectual or learning disability, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder) also co-occur with SUDs, with rates varying (between 1% and 45%; Levin, Reference Levin2007; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Balogh, McGarry, Selick, Dobranowski, Wilton and Lunsky2016; Salavert et al., Reference Salavert, Clarabuch, Fernández-Gómez, Barrau, Giráldez and Borràs2018). Many developmental disorders may remain undiagnosed at treatment (Gooden et al., Reference Gooden, Cox, Petersen, Curtis, Manning and Lubman2020), and it is possible that similar factors that form barriers to diagnosis and support for individuals with developmental disorders (i.e., social and environmental disadvantages; Carroll Chapman & Wu, Reference Carroll Chapman and Wu2012) are also risk factors for developing SUDs.

Regardless of aetiology, CI in individuals with SUDs can severely impede everyday functioning. The degree of executive dysfunction could determine how effectively individuals with SUDs are able to cope with day-to-day demands (see Verdejo-Garcia, Garcia-Fernandez, & Dom, Reference Verdejo-Garcia, Garcia-Fernandez and Dom2019). Impaired inhibitory control can contribute to behavioural difficulties, including increased impulsivity and poor decision-making (Ramey & Regier, 2020). CI also has impacts on the ability to engage successfully with SUD treatment (Bates, Bowden, & Barry, Reference Bates, Bowden and Barry2002), with individuals less likely to benefit from the therapeutic process or acquire effective strategies, related to diminished insight and motivation (Aharonovich, Amrhein, Bisaga, Nunes, & Hasin, Reference Aharonovich, Amrhein, Bisaga, Nunes and Hasin2008). CI is also associated with poorer treatment compliance (Copersino et al., Reference Copersino, Schretlen, Fitzmaurice, Lukas, Faberman, Sokoloff and Weiss2012). However, individuals with CI can benefit from treatment, particularly when treatment is appropriately matched to cognitive level (Bates, Buckman, & Nguyen, Reference Bates, Buckman and Nguyen2013). For instance, cognitive-behavioural approaches are geared to enhance higher-order cognitive processes related to self-awareness and decision-making. These cognitive skills may be fundamentally reduced in individuals with CI (Hagen et al., Reference Hagen, Erga, Hagen, Nesvåg, McKay, Lundervold and Walderhaug2016), who may benefit more from interactional programmes with reduced cognitive demands (Secades-Villa, García-Rodríguez, & Fernández-Hermida, Reference Secades-Villa, García-Rodríguez and Fernández-Hermida2015) or increased involvement of social supports (Buckman, Bates, & Cisler, Reference Buckman, Bates and Cisler2007; Buckman, Bates, & Morgenstern, Reference Buckman, Bates and Morgenstern2008).

Given the impact of CI on SUD treatment, accurate and timely detection of CI is essential. The wide range of factors contributing to CI in individuals presenting for SUD treatment, however, results in heterogeneous cognitive profiles that vary in their clinical presentation, making CI difficult to detect (Horner, Harvey, & Denier, Reference Horner, Harvey and Denier1999). Consequently, individuals with CI presenting for SUD treatment might not receive the most appropriate support (Braatveit, Torsheim, & Hove, Reference Braatveit, Torsheim and Hove2018).

While neuropsychological assessment is the gold standard in evaluating cognitive functioning (Roebuck-Spencer et al., Reference Roebuck-Spencer, Glen, Puente, Denney, Ruff, Hostetter and Bianchini2017), this is not always feasible as it is time-consuming (taking up to several hours) and requires extensive training in administration and interpretation (Ridley et al., Reference Ridley, Batchelor, Draper, Demirkol, Lintzeris and Withall2018; Roebuck-Spencer et al., Reference Roebuck-Spencer, Glen, Puente, Denney, Ruff, Hostetter and Bianchini2017). According to the 2014 American Psychological Association Working Group on Screening and Assessment (APA–WGSA) guidelines, cognitive screening tools are used for early identification of individuals at high risk for a specific disorder, are generally brief, monitor treatment progress or change in symptoms over time, can be administered by clinicians with appropriate training, and are not definitively diagnostic (APA–WGSA, 2014). Cognitive screening, therefore, represents a critical preliminary stage of triaging those in need of more comprehensive neuropsychological assessment (Roebuck-Spencer et al., Reference Roebuck-Spencer, Glen, Puente, Denney, Ruff, Hostetter and Bianchini2017).

Cognitive screening is routinely practiced in primary and tertiary settings in the assessment of adults with mild CI, dementia, ABI, and psychiatric illness (Roebuck-Spencer et al., Reference Roebuck-Spencer, Glen, Puente, Denney, Ruff, Hostetter and Bianchini2017); however, it is much less established as a standard clinical process for individuals with SUD. Cognitive screening tools should be chosen carefully, with reference to both clinical utility and psychometric properties for the population in which it will be used (Slater & Young, Reference Slater and Young2013). The measure should have high sensitivity (to correctly detect those with CI) and good specificity (to accurately rule out those without CI; Bunnage, Reference Bunnage and Bowden2017). If specificity is too low, clients may inaccurately be perceived as needing full assessment, with potential for resource overload as well as unnecessary alarm for the individual. Yet, if sensitivity is too low, clients that would benefit from full assessment may not receive this, leading to a potential mismatch in treatment provision.

There exists limited evidence to guide decision-making on which cognitive screening tool is appropriate for use with individuals presenting for the treatment of SUDs. The most widely used cognitive screening tools, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh1975) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA; Nasreddine et al., Reference Nasreddine, Phillips, Bédirian, Charbonneau, Whitehead, Collin and Chertkow2005), have most consistently been used in older adult populations (e.g., for stroke and dementia screening). It remains unclear how well these measures can detect CI in individuals with SUDs, or whether there are more appropriate screening tools for use in this population. Given the impact of CI on SUD treatment outcomes, there is a clear need for evidence-based review and recommendations around the use of cognitive screening tools in adults engaging in SUD treatment.

Objective

The aims of this systematic review were to: (1) describe types of cognitive screening measures used in adults with SUDs; (2) identify specific substance use populations and settings these tools are utilised in; (3) review diagnostic accuracy of these screening measures in detecting CI versus an accepted objective reference standard; and (4) evaluate methodology of these studies for risk of bias. It was hoped this review would yield clinical recommendations for use of cognitive screening in individuals presenting for the treatment of SUDs in clinical settings, as well as identify areas for future research in this field.

METHOD

Search Strategy

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement guided the reporting standards of this review (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & The PRISMA Group, Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009). Results of systematic review registry searches (e.g., PROSPERO) did not reveal similar systematic reviews as of May 2020. The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO on 7 November 2020 (ID: CRD42020185902; www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero).

A systematic search of the Medline, Embase, PsycINFO (OVID), and CINAHL (EBSCO) databases was undertaken in June 2019 and updated in May 2020. The search strategy was constructed around the aims of the review. Subject headings, keywords, and keyword phrases were developed for each of the search concepts, substance use disorder, cognition, and screening or assessment. Subject headings and keywords for each concept were combined using the Boolean operator ‘OR’ before the concepts were bought together using the ‘AND’ operator. The search strategy was developed by a senior research librarian (AS) and was designed in Medline before being translated to the other databases. Searches were limited to adult populations and studies in English. No date limits were applied. Comments, editorials, letters, news, book, and book chapters as well as conference abstracts were excluded (see Supplementary Material 1 for full search strategies). In addition, supplementary searching was undertaken in Google Scholar using a combination of search terms for the first 200 results. The reference lists of all papers that met the final inclusion criteria were screened for any additional relevant citations not captured in the database searches. Screening for articles prepared for publication but not yet in print was performed through a search of above search terms of the Psychology Preprint Archive (psyarxiv.com); an author known to be developing a measure in this field was also contacted for potential preprints. A comprehensive grey literature search was not conducted. Results were exported to EndNote and duplicates removed. Studies were then exported to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation; www.covidence.org) for screening.

Inclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were set: (1) original empirical article, published or prepared for publication (i.e., under review); (2) in English; (3) reported on a tool designed to screen for cognitive functioning, or the tool was used for this purpose (in isolation or embedded as part of a broader screening process); (4) examined or provided data that supported inferences regarding criterion validity of the screening tool compared to an accepted standard criterion of cognitive functioning (e.g., neuropsychological assessment); (5) participants were adults (aged 18 years and above); and (6) participants were reported to have some form of SUD (inclusive of alcohol-use or other specific disorder types). The standards described by the 2014 APA–WGSA statement guided screening tool eligibility, specifying they must: (1) be brief to administer; (2) collect objective test data with an established protocol for scoring; (3) require minimal, non-specialist training; and (4) not used for the purpose of definitive diagnosis. To maximise eligible studies, screening tools were not excluded if they also collected functional or self-report information, or focused on one cognitive domain. No restriction on type of criterion validity analysis was applied (e.g., correlations, regression, receiver operating curve).

Screening, Extraction, and Risk of Bias

Two authors (JK and KK) independently screened titles and abstracts from the database searches for articles meeting inclusion criteria (Phase 1). JK and KK independently reviewed full-text articles for eligibility using the same review criteria (Phase 2). If there was disagreement between authors on eligibility for an article, a third author (NR) was consulted and decisions were resolved by consensus. Additional studies retrieved from correspondence or Google Scholar searches were included if author consensus (JK, KK, and NR) indicated they met inclusion criteria.

Data extraction from articles meeting criteria was conducted by JK and KK, with a check by author NR. Variables of interest included target population, study design, recruitment method, participant demographics, index test, reference standard, and relevant psychometric data (e.g., sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratios, and correlation coefficients).

Included studies were also assessed for risk of bias and applicability (JK and KK) using the revised Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS–2) tool according to scoring guidelines presented in Whiting and colleagues (Reference Whiting, Rutjes, Westwood, Mallett, Deeks and Reitsma2011). Data extraction, risk of bias, and applicability ratings followed the same dual, independent examination and consensus procedures as described for article screening. NR was not involved in reviewing her respective paper (Ridley et al., Reference Ridley, Batchelor, Draper, Demirkol, Lintzeris and Withall2018); instead, SB was consulted for consensus decisions.

Risk of bias assessment using QUADAS–2

The QUADAS–2 assessment tool (Whiting et al., Reference Whiting, Rutjes, Westwood, Mallett, Deeks and Reitsma2011) evaluated risk of bias and applicability of diagnostic accuracy studies (www.quadas.org). Guided by the Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) criteria, this scale was developed to allow more transparency in reporting (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Korevaar, Altman, Bruns, Gatsonis, Hooft and Bossuyt2016; Whiting et al., Reference Whiting, Rutjes, Westwood, Mallett, Deeks and Reitsma2011) and is recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration (www.cochrane.org) and National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE; www.nice.org.uk).

The QUADAS–2 rating process has four phases: (1) summarise review question; (2) tailor the tool to the review; (3) construct a flow diagram for the study; and (4) assess risk of bias and applicability concerns. The tool consists of four key domains: (1) patient selection; (2) index test; (3) reference standard; and (4) flow and timing (i.e., flow of participants through the study, timing of administration of index test and reference standard). Each domain is assessed for risk of bias, the first three also for applicability concerns. Signalling questions guided decision-making on high or low risk of bias (Schueler, Schuetz, & Dewey, Reference Schueler, Schuetz and Dewey2012), rated as ‘Yes’, ‘No’, or ‘Unclear’. Risk of bias is deemed ‘Low’ if all relevant signalling questions are rated ‘Yes’; however, bias may exist if these questions are rated as ‘No’ or ‘Unclear’. If questions relating to concerns regarding applicability are rated as ‘High’ or ‘Unclear’, aspects of the study may not match the review question.

Statistical Interpretation

Sensitivity, the ability of a screening tool to correctly identify individuals with a condition of interest, and specificity, the ability of a screening tool to detect individuals who do not have a condition, are relative to a reference standard. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve can be plotted by using sensitivity against the false-positive rate (1–specificity) for given cut-off points of a screening test. An area under ROC curve (AUC) value summarises overall test diagnostic accuracy (Trevethan, Reference Trevethan2017), ranging from 0 to 1, where 0 and 1 represent perfectly inaccurate or accurate tests, respectively. As a guide, AUC values of 0.5 indicate no meaningful discrimination ability, 0.7 to 0.8 acceptable, 0.8 to 0.9 excellent, and >0.9 outstanding (Mandrekar, Reference Mandrekar2010).

Sensitivity and specificity are used to obtain predictive power and likelihood ratios. Positive predictive power describes the probability that an individual with a positive test result is a true positive; negative predictive power indicates the probability an individual who obtains a negative test result is a true negative. Both are dependent on the prevalence of the target condition in each population sample (Bunnage, Reference Bunnage and Bowden2017; Trevethan, Reference Trevethan2017).

A positive likelihood ratio (LR+) refers to the ratio between the probability of correctly classifying an individual as having CI and the probability of incorrectly classifying an individual who does not have CI (i.e., sensitivity/100–specificity). A LR+ greater than 10 indicates CI is highly likely when a positive test result is yielded. A negative likelihood ratio (LR–) is the ratio between the probability of incorrectly classifying an individual as having CI and the probability of correctly classifying an individual who does not have CI (i.e., 100–sensitivity/specificity). A LR– below 0.1 indicates that impairment is highly unlikely when a negative test result is obtained (McGee, Reference McGee2002).

For studies that examined correlations between cognitive screening tools and reference tests, coefficients of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 indicated small, medium, and large relationships, respectively (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988).

RESULTS

Search Results

Figure 1 presents a flow diagram of search results. Searches of electronic databases of published articles identified 5,135 candidate studies. Removal of 1,672 duplicates resulted in 3,463 studies. An additional study identified from a Google Scholar search and another through correspondence with an author brought the total to 3,465 studies. A search of the Psychology Preprint Archive yielded no additional studies. After screening the titles and abstracts (Phase 1), the number of studies was reduced to 35. Examination of full-text versions of eligible studies identified 14 relevant papers. Full-text articles were excluded for not meeting the following criteria: not appropriate study design (e.g., did not evaluate screening tool against a standard criterion of cognitive functioning); did not meet 2014 APA–WGSA screening criteria; and did not include participants with SUDs. One duplicate was also removed during this phase.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Study Characteristics

Tables 1–3 present characteristics of the 14 included studies and an overview of the screening measures and reference standards. Studies were conducted in the United States of America (n = 3), France (n = 3), the Netherlands (n = 2), Spain (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), Brazil (n = 1), Belgium (n = 1), and Australia (n = 2). Across all 14 studies, the average clinical sample size was 88.33 (SD = 116.75); however, the range between studies varied widely from 20 to 501 participants. The majority of studies (n = 11; 78.57%) made reference to formal diagnostic criteria (e.g., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) to operationalise SUD. Over a quarter (n = 4) included a sample with a single problematic substance (Ewert et al., Reference Ewert, Pelletier, Alarcon, Nalpas, Donnadieu-Rigole, Trouillet and Perney2018; Pelletier et al., Reference Pelletier, Alarcon, Ewert, Forest, Nalpas and Perney2018; Ritz et al., Reference Ritz, Lannuzel, Boudehent, Vabret, Bordas, Segobin and Beaunieux2015; Wester et al., Reference Wester, Westhoff, Kessels and Egger2013). All studies included participants with alcohol use disorder, nearly two-thirds also included those with cannabis use (n = 9; 64.29%), followed by cocaine use (n = 7; 50.00%), then opioids (n = 6; 42.86%). Only one study failed to report the specific substance of misuse (To et al., Reference To, Vanheule, Vanderplasschen, Audenaert and Vandevelde2015). Over two-thirds (n = 8; 57.14%) required a period of abstinence before engaging in cognitive assessment, while three studies did not require any period of abstinence (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Shores, Nardo, Sedwell, Lunn, Marceau and Batchelor2021; Ridley et al., Reference Ridley, Batchelor, Draper, Demirkol, Lintzeris and Withall2018; Rojo-Mota et al., Reference Rojo-Mota, Pedrero-Pérez, Ruiz-Sánchez de León, León-Frade, Aldea-Poyo, Alonso-Rodríguez and Morales-Alonso2017) and one study did not specify abstinence status (Wester et al., Reference Wester, Westhoff, Kessels and Egger2013). Nearly, half of studies (n = 6; 46.15%) were in an inpatient setting, two (15.38%) outpatient, four (30.77%) residential rehabilitation, and two (14.29%) did not report the setting.

Table 1. Study characteristics of articles included for review

Note: Only clinical sample characteristics are presented here. As Ridley et al. (Reference Ridley, Batchelor, Draper, Demirkol, Lintzeris and Withall2018) and Wester et al. (Reference Wester, Westhoff, Kessels and Egger2013) combined clinical and control data when calculating accuracy statistics, both groups are presented in this table. DSM–III–R, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual–Third Edition–Revised; DSM–IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual–Fourth Edition; DSM–IV–TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual–Fourth Edition–Text-Revised; DSM–5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual–Fifth Edition; ICD–10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems–10th Revision; NR, not reported; SD, standard deviation; WAIS–III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Third Edition; WAIS–IV, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Fourth Edition.

Table 2. Overview of cognitive screening measures

M, mean; SD, standard deviation; SUD, substance use disorder.

Table 3. Overview of screening measures and reference standards for included studies

ACE–R, Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination–Revised; ACLS–5, Allen Cognitive Level Screen–Fifth Edition; BCSE, Brief Cognitive Status Examination; BEARNI, Brief Evaluation of Alcohol-Related Neuropsychological Impairments; BEAT, Brief Executive Function Assessment Tool; CI, cognitive impairment; CST–14, Cognitive Screening Test–14; CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test; CVLT–II, California Verbal Learning Test–Second Edition; DART, Dutch Adult Reading Test; D–KEFS TMT, Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System Trail Making Test; DSB, Digit Span Backward; DSF, Digit Span Forward; DSS, Digit Span Sequencing; FAB, Frontal Assessment Battery; FCSRT, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test; FPT, Five-Point Test; FSIQ, Full Scale Intelligence Quotient; GMI, General Memory Index; HASI, Hayes Ability Screening Index; LNS, letter–number sequencing; LOTCA, Loewenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment; MAE, Multilingual Aphasia Exam; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; NAB–SM, Neuropsychological Assessment Battery–Screening Module; NART, National Adult Reading Test; NCSE, Neurobehavioural Cognitive Status Examination; NPA, neuropsychological assessment; NR, not reported; NSB, Neuropsychological Screening Battery; RAVLT, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; RBMT–3, Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test–Third Edition; RFFT, Ruff Figural Fluency Test; ROCF, Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure; SCWT, Stroop and Colour Word Test; SD, standard deviation; SDMT, Symbol Digit Modalities Test; SUD, substance use disorder; TMT, Trail Making Test; TMT A, Trail Making Test-Part A; TMT B, Trail Making Test-Part B; TMT B–A, Trail Making Test Part A minus Part B; Vineland II, Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales–Second Edition; WAIS–R, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised; WAIS–III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Third Edition; WAIS–IV, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Fourth Edition; WAIS–IV–NL, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Fourth Edition (Dutch version); WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; WMS, Wechsler Memory Scale; WMS–IV, Wechsler Memory Scale–Fourth Edition.

As per inclusion criteria, each study that was included compared an index test (i.e., the cognitive screening measure) to a reference standard (i.e., neuropsychological assessment). In over a quarter of studies (28.57%), a particular syndrome of interest (e.g., Korsakoff’s syndrome, intellectual disability) influenced test selection for the reference standard. The index tests and reference standards are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

The majority of studies (n = 12; 85.57%) examined only one screening tool. Across all 14 studies, 10 different index measures were used, with the most common being the MoCA (n = 6; 46.15%). Most (n = 8; 80.00%) were developed for use within other populations (e.g., dementia, intellectual disability, brain injury); however, two were developed specifically for use within a SUD population (Brief Evaluation of Alcohol-Related Neuropsychological Impairments [BEARNI] and Brief Executive Function Assessment Tool [BEAT]). Length of administration for cognitive screening measures varied between 10 and 45 minutes. Almost all index measures targeted multiple cognitive domains, including: orientation (n = 5; 35.71%), attention (n = 6; 42.86%), language (n = 6; 42.86%), visual-spatial abilities (n = 8; 57.14%), memory (n = 7; 50%), motor ability (n = 3; 21.43%), and executive functions (n = 6; 42.86%). The Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) focused on one cognitive domain (executive functioning).

Across all 14 studies, reference standards varied in cognitive domains and specific neuropsychological tests. While the reference standard largely encompassed a range of cognitive domains, two studies (14.28%) utilised a reference standard focusing on one cognitive domain (i.e., executive functioning, memory; Berry et al., Reference Berry, Shores, Nardo, Sedwell, Lunn, Marceau and Batchelor2021; Wester et al., Reference Wester, Westhoff, Kessels and Egger2013). Another study (Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Nicastri, de Andrade and Bolla2010) restricted the reference standard to attention, working memory, and executive function. Other variations across studies included time between administration of index and reference standard (ranging from the same day to three months later), and operationalisation of ‘impairment’ for the reference standard.

Screening Measure Utility

Diagnostic accuracy

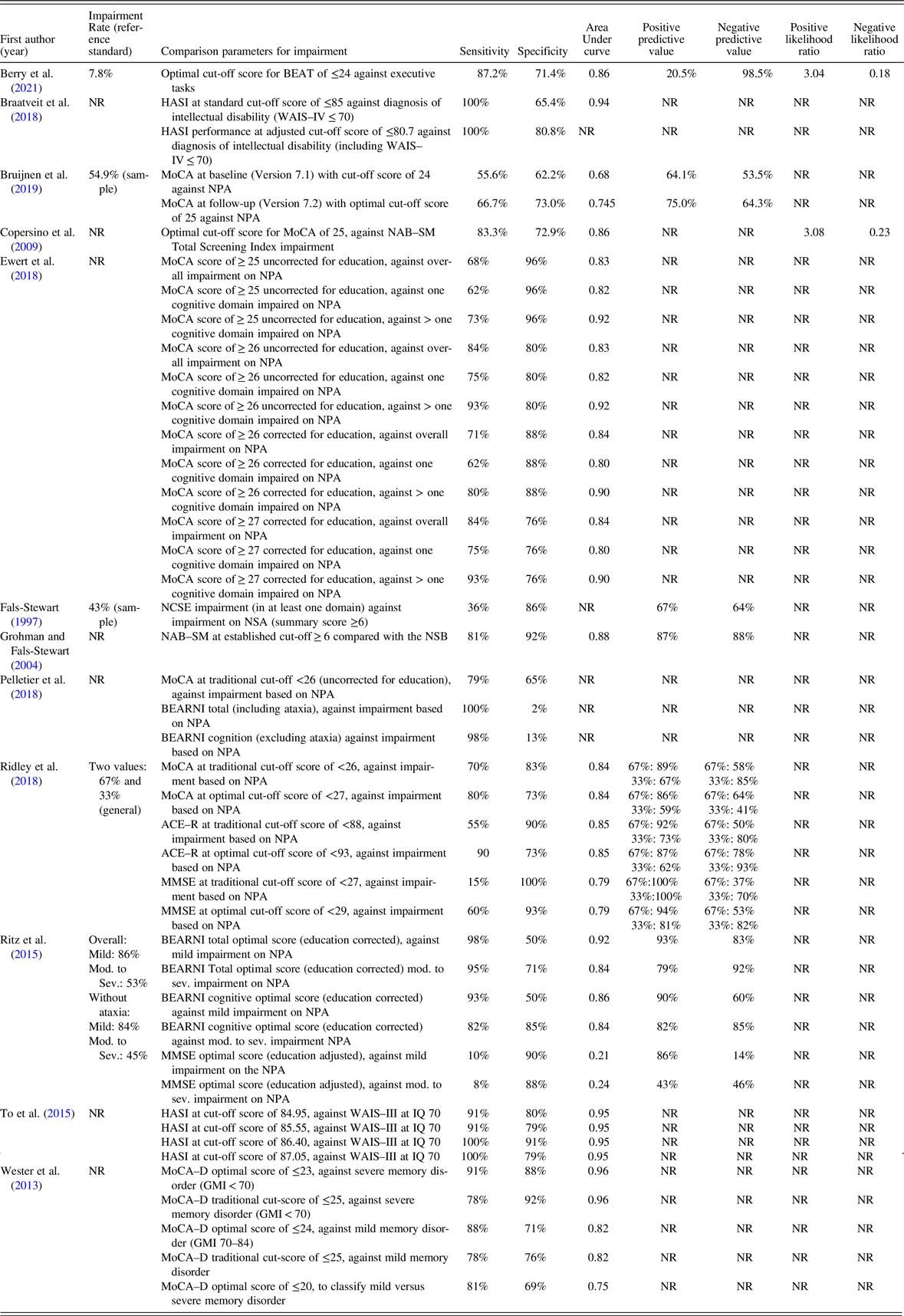

Table 4 displays psychometric data provided by 12 studies that reported classification accuracy (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Shores, Nardo, Sedwell, Lunn, Marceau and Batchelor2021; Braatveit et al., Reference Braatveit, Torsheim and Hove2018; Bruijnen et al., Reference Bruijnen, Jansen, Dijkstra, Walvoort, Lugtmeijer, Markus and Kessels2019; Copersino et al., Reference Copersino, Fals-Stewart, Fitzmaurice, Schretlen, Sokoloff and Weiss2009; Ewert et al., Reference Ewert, Pelletier, Alarcon, Nalpas, Donnadieu-Rigole, Trouillet and Perney2018; Fals-Stewart, Reference Fals-Stewart1997; Grohman & Fals-Stewart, Reference Grohman and Fals-Stewart2004; Pelletier et al., Reference Pelletier, Alarcon, Ewert, Forest, Nalpas and Perney2018; Ridley et al., Reference Ridley, Batchelor, Draper, Demirkol, Lintzeris and Withall2018; Ritz et al., Reference Ritz, Lannuzel, Boudehent, Vabret, Bordas, Segobin and Beaunieux2015; To et al., Reference To, Vanheule, Vanderplasschen, Audenaert and Vandevelde2015; Wester et al., Reference Wester, Westhoff, Kessels and Egger2013). While all of these studies provided sensitivity and specificity data for at least one defined cut-point, two did not provide overall AUC data (Fals-Stewart, Reference Fals-Stewart1997; Pelletier et al., Reference Pelletier, Alarcon, Ewert, Forest, Nalpas and Perney2018). Although several studies included control groups in the overall study, two included control groups in diagnostic accuracy data (Ridley et al., Reference Ridley, Batchelor, Draper, Demirkol, Lintzeris and Withall2018; Wester et al., Reference Wester, Westhoff, Kessels and Egger2013).

Table 4. Psychometric data retrieved from primary classification accuracy studies

ACE–R, Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination–Revised; BEARNI, Brief Evaluation of Alcohol-Related Neuropsychological Impairments; BEAT, Brief Executive Function Assessment Tool; FAB, Frontal Assessment Battery; GMI, General Memory Index; HASI, Hayes Ability Screening Index; IQ, intellectual quotient; LOTCA, Loewenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MoCA–D, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (Dutch version); NAB–SM, Neuropsychological Assessment Battery–Screening Module; NCSE, Neurobehavioural Cognitive Status Examination; NPA, europsychological assessment; NR, not reported; NSB, Neuropsychological Screening Battery; WAIS–III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Third Edition; WAIS–IV, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Fourth Edition.

Of the studies that provided overall AUC data, the MoCA ranged from acceptable to outstanding in the detection of CI (range: 0.75–0.96). The single study examining the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination–Revised (ACE–R; Ridley et al., Reference Ridley, Batchelor, Draper, Demirkol, Lintzeris and Withall2018) revealed excellent discriminative ability (AUC = 0.85), as did the Hayes Ability Screening Index (HASI; AUC = 0.94–0.95) across two studies (Braatveit et al., Reference Braatveit, Torsheim and Hove2018; To et al., Reference To, Vanheule, Vanderplasschen, Audenaert and Vandevelde2015), and the Neuropsychological Assessment Battery–Screening Module (NAB–SM; AUC = 0.88; Fals-Stewart, Reference Fals-Stewart1997). The MMSE by comparison had lower accuracy that ranged from no discrimination ability to acceptable (AUC = 0.21–0.79) across two studies (Ridley et al., Reference Ridley, Batchelor, Draper, Demirkol, Lintzeris and Withall2018; Ritz et al., Reference Ritz, Lannuzel, Boudehent, Vabret, Bordas, Segobin and Beaunieux2015). For index measures specifically developed for SUD populations (BEAT and BEARNI), at least excellent accuracy in detecting CI was reported (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Shores, Nardo, Sedwell, Lunn, Marceau and Batchelor2021; Ritz et al., Reference Ritz, Lannuzel, Boudehent, Vabret, Bordas, Segobin and Beaunieux2015).

Half of studies that reported diagnostic accuracy data (n = 6) included Positive Predictive Power and Negative Predictive Power; only two studies reported positive and negative likelihood ratios (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Shores, Nardo, Sedwell, Lunn, Marceau and Batchelor2021; Copersino et al., Reference Copersino, Fals-Stewart, Fitzmaurice, Schretlen, Sokoloff and Weiss2009). Berry and colleagues (Reference Berry, Shores, Nardo, Sedwell, Lunn, Marceau and Batchelor2021) was the sole study that reported classification accuracy as well as predictive power and likelihood ratios. Using a LR+ of ≥10 and LR– of ≤0.1 as threshold (McGee, Reference McGee2002), a score of ≤14 on the BEAT (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Shores, Nardo, Sedwell, Lunn, Marceau and Batchelor2021) was needed to rule in likely impairment, while a score of ≥31 was needed to likely rule out impairment. Copersino et al. (Reference Copersino, Fals-Stewart, Fitzmaurice, Schretlen, Sokoloff and Weiss2009) indicated that a cut-score of ≤22 on the MoCA had strong evidence for ruling in CI and a score of ≥27 had strong evidence.

Correlational data

More than half of the 14 studies (n = 8) examined correlations between index tests and neuropsychological measures, with most (n = 6) presenting this in addition to classification accuracy data. Two studies (Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Nicastri, de Andrade and Bolla2010; Rojo-Mota et al., Reference Rojo-Mota, Pedrero-Pérez, Ruiz-Sánchez de León, León-Frade, Aldea-Poyo, Alonso-Rodríguez and Morales-Alonso2017) provided correlational data only. As outlined in Table 5, various correlations were performed, including: index total summary scores as compared to reference standard total summary score; index domain score as compared to corresponding reference standard domain scores; and total index score versus specific test outcome on the reference standard. One study (Ridley et al., Reference Ridley, Batchelor, Draper, Demirkol, Lintzeris and Withall2018) combined control and clinical groups to produce correlational data, while all others used clinical samples only. The largest correlations reported were between total summary scores derived from a reference standard (i.e., the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; RBANS) and total scores on the MoCA (r = 0.75) and the ACE–R (r = 0.81; Ridley et al., Reference Ridley, Batchelor, Draper, Demirkol, Lintzeris and Withall2018). Similarly, large correlations were observed between HASI total score and Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Third Edition Full Scale IQ (r = 0.69–0.70; To et al., Reference To, Vanheule, Vanderplasschen, Audenaert and Vandevelde2015). For the MoCA, medium to large correlations between MoCA total score and neuropsychological tasks assessing executive function (r = 0.32–0.46), learning and memory (r = 0.45–0.56), working memory (r = 0.27–0.29), and fluency (r = 0.37–0.53) were found (Ewert et al., Reference Ewert, Pelletier, Alarcon, Nalpas, Donnadieu-Rigole, Trouillet and Perney2018). MoCA domain scores also yielded medium to large correlations to corresponding neuropsychological domains (Bruijnen et al., Reference Bruijnen, Jansen, Dijkstra, Walvoort, Lugtmeijer, Markus and Kessels2019; Ridley et al., Reference Ridley, Batchelor, Draper, Demirkol, Lintzeris and Withall2018), with the exception of the domains of language and attention/orientation items (Ridley et al., Reference Ridley, Batchelor, Draper, Demirkol, Lintzeris and Withall2018). For the ACE–R, Ridley and colleagues (Reference Ridley, Batchelor, Draper, Demirkol, Lintzeris and Withall2018) reported medium to large correlations between reference domains and relevant ACE–R subscales, with the exception of language. For the FAB, Cuhna and colleagues (Reference Cunha, Nicastri, de Andrade and Bolla2010) reported medium to large correlations (r = 0.41–0.57) between FAB tasks and performance on specific executive function measures; however, not all correlations were significant (r = 0.03–0.27). For the Loewenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment (LOTCA), medium to large correlations between index and reference tasks were found for measures of visual-perceptual abilities and psychomotor abilities (Rojo-Mota et al., Reference Rojo-Mota, Pedrero-Pérez, Ruiz-Sánchez de León, León-Frade, Aldea-Poyo, Alonso-Rodríguez and Morales-Alonso2017). However, reference measures assessing executive functioning and memory did not correspond consistently with LOTCA subscales. For the BEAT, there were medium to large correlations between overall score and performance on reference tasks measuring executive functioning (r = 0.43–0.57; Berry et al., Reference Berry, Shores, Nardo, Sedwell, Lunn, Marceau and Batchelor2021).

Table 5. Summary of studies examining correlations between cognitive screening tools and comprehensive cognitive assessment

* Included if at least significant at the .05 level or higher.

ACE–R, Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination–Revised; ACLS–5, Allen Cognitive Level Screen–Fifth Edition; BCSE, Brief Cognitive Status Examination; BEAT, Brief Executive Function Assessment Tool; DSF, Digit Span Forward; DSS, Digit Span Sequencing; FAB, Frontal Assessment Battery; FDT, Five-Digit Test; FPT, Five-Point Test; FSIQ, Full Scale Intelligence Quotient; HASI, Hayes Ability Screening Index; LOTCA, Loewenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; NAB–SM, Neuropsychological Assessment Battery–Screening Module; NPA, neuropsychological assessment; PSI, Processing Speed Index; RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; ROCF, Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure; TMT, Trail Making Test; SCWT, Stroop and Colour Word Test; WAIS–III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Third Edition; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; WMS–IV, Wechsler Memory Scale–Fourth Edition.

Quality

Ratings of risk of bias, applicability, and quality of study design are presented in Table 6. Almost all studies were judged to have a high or unclear risk of bias in terms of patient selection (QUADAS–2 Domain 1;92.86%) due to convenience or unclear sampling methods (57.14%; Braatveit et al., Reference Braatveit, Torsheim and Hove2018; Bruijnen et al., Reference Bruijnen, Jansen, Dijkstra, Walvoort, Lugtmeijer, Markus and Kessels2019; Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Nicastri, de Andrade and Bolla2010; Copersino et al., Reference Copersino, Fals-Stewart, Fitzmaurice, Schretlen, Sokoloff and Weiss2009; Pelletier et al., Reference Pelletier, Alarcon, Ewert, Forest, Nalpas and Perney2018; Ritz et al., Reference Ritz, Lannuzel, Boudehent, Vabret, Bordas, Segobin and Beaunieux2015, To et al., Reference To, Vanheule, Vanderplasschen, Audenaert and Vandevelde2015; Wester et al., Reference Wester, Westhoff, Kessels and Egger2013); inappropriate or unclear exclusions (57.14%; Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Nicastri, de Andrade and Bolla2010; Ewert et al., Reference Ewert, Pelletier, Alarcon, Nalpas, Donnadieu-Rigole, Trouillet and Perney2018; Fals-Stewart, Reference Fals-Stewart1997; Grohman & Fals-Stewart, Reference Grohman and Fals-Stewart2004; Pelletier et al., Reference Pelletier, Alarcon, Ewert, Forest, Nalpas and Perney2018; Ritz et al., Reference Ritz, Lannuzel, Boudehent, Vabret, Bordas, Segobin and Beaunieux2015; Rojo-Mota et al., Reference Rojo-Mota, Pedrero-Pérez, Ruiz-Sánchez de León, León-Frade, Aldea-Poyo, Alonso-Rodríguez and Morales-Alonso2017, Wester et al., Reference Wester, Westhoff, Kessels and Egger2013); inclusion of a control group in analyses (14.29%; Ridley et al., Reference Ridley, Batchelor, Draper, Demirkol, Lintzeris and Withall2018; Ritz et al., Reference Ritz, Lannuzel, Boudehent, Vabret, Bordas, Segobin and Beaunieux2015); or a combination of these factors. Nearly half of the included studies (n = 6;42.86%) had the main aim of validating the index measure within a SUD population (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Shores, Nardo, Sedwell, Lunn, Marceau and Batchelor2021; Braatveit et al., Reference Braatveit, Torsheim and Hove2018; Copersino et al., Reference Copersino, Fals-Stewart, Fitzmaurice, Schretlen, Sokoloff and Weiss2009; Ritz et al., Reference Ritz, Lannuzel, Boudehent, Vabret, Bordas, Segobin and Beaunieux2015; Rojo-Mota et al., Reference Rojo-Mota, Pedrero-Pérez, Ruiz-Sánchez de León, León-Frade, Aldea-Poyo, Alonso-Rodríguez and Morales-Alonso2017; To et al., Reference To, Vanheule, Vanderplasschen, Audenaert and Vandevelde2015). Half of the studies had high or unclear risk of bias for the index test (QUADAS–2 Domain 2; 50.00%), while a greater number had a high or unclear risk of bias for the reference standard (QUADAS–2 Domain 3; 71.43%). The high risk was largely due to the non-blinding of index or reference test results; only four studies (Ewert et al., Reference Ewert, Pelletier, Alarcon, Nalpas, Donnadieu-Rigole, Trouillet and Perney2018; Pelletier et al., Reference Pelletier, Alarcon, Ewert, Forest, Nalpas and Perney2018; Rojo-Mota et al., Reference Rojo-Mota, Pedrero-Pérez, Ruiz-Sánchez de León, León-Frade, Aldea-Poyo, Alonso-Rodríguez and Morales-Alonso2017; Wester et al., Reference Wester, Westhoff, Kessels and Egger2013) used different individuals to administer the index and reference measures, while in another seven the order of administration or prior knowledge of test results by the tester was unclear (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Shores, Nardo, Sedwell, Lunn, Marceau and Batchelor2021; Braatveit et al., Reference Braatveit, Torsheim and Hove2018; Bruijnen et al., Reference Bruijnen, Jansen, Dijkstra, Walvoort, Lugtmeijer, Markus and Kessels2019; Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Nicastri, de Andrade and Bolla2010; Fals-Stewart, Reference Fals-Stewart1997; Grohman & Fals-Stewart, Reference Grohman and Fals-Stewart2004; Ritz et al., Reference Ritz, Lannuzel, Boudehent, Vabret, Bordas, Segobin and Beaunieux2015). For participant flow and timing (QUADAS–2 Domain 4), nearly half of included studies had either high or unclear risk of bias (42.86%) due to inappropriate or unclear time interval between the administration of the index test and the reference standard (n = 2), participants not all receiving the reference standard (n = 3), or not accounting for missing participant data, either clinically or statistically. Overall, quality rating results based on QUADAS–2 indicated generally poor adherence to STARD criteria across the included studies. Two studies (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Shores, Nardo, Sedwell, Lunn, Marceau and Batchelor2021; Bruijnen et al., Reference Bruijnen, Jansen, Dijkstra, Walvoort, Lugtmeijer, Markus and Kessels2019) were not rated as high risk across any domains; however, unclear ratings meant that risk was unable to be fully assessed.

Table 6. QUADAS–2 ratings for studies included in the review

QUADAS–2, Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies – Version 2; HR, high risk; LR, low risk; ? = unclear risk.

By contrast, the majority of studies met applicability criteria for the current review. The exception was in relation to the reference standard (QUADAS–2 Domain 3) across two studies (Braatveit et al., Reference Braatveit, Torsheim and Hove2018; To et al., Reference To, Vanheule, Vanderplasschen, Audenaert and Vandevelde2015). These studies sought to evaluate presence of intellectual disability within SUD populations, and consequently, it is possible the reference standards could fail to detect CI specifically related to SUD, or CI more broadly in this population.

DISCUSSION

This review had four primary aims: (1) describe types of cognitive screening measures used in adults with SUDs; (2) identify specific SUD population and settings in which these tools are utilised; (3) review diagnostic accuracy of these screening measures in relation to detecting CI versus an accepted objective reference standard; and (4) evaluate methodology of these studies to determine risk of bias.

Aims 1 and 2: Overview of Cognitive Screening Measures in Adults with SUDs

The current review, to the authors’ knowledge, is the first systematic overview of cognitive screening tools utilised in adult SUD populations as compared to a reference standard (e.g., neuropsychological assessment). Overall, 14 studies were identified which broadly aligned with definitions of cognitive screening as proposed by Roebuck-Spencer and colleagues (Reference Roebuck-Spencer, Glen, Puente, Denney, Ruff, Hostetter and Bianchini2017). In summary, more than three-quarters of studies made reference to specific SUD diagnostic criteria. The majority included individuals with poly-substance use, while the remaining specifically examined alcohol use. Alcohol was the most common substance used by participants, with a period of abstinence also frequently endorsed, and nearly half of studies were conducted in an inpatient setting. However, a number of studies failed to report key study details including study setting, specific substance of misuse, and abstinence status. Sample sizes were generally small, with the exception of Berry and colleagues (Reference Berry, Shores, Nardo, Sedwell, Lunn, Marceau and Batchelor2021), who commendably captured a large sample.

Across the 14 included studies, 10 different cognitive screening tools were evaluated. The majority of studies examined only one measure, and all were paper and pen tasks. The range of cognitive domains and tasks assessed by the screening tool and length of administration varied widely across studies. Most studies sought to validate existing cognitive screening tools in this new population, primarily the MoCA, with two seeking to validate new measures for specific use in SUD populations (BEAT and BEARNI). In over a quarter of studies, a particular syndrome of interest was evaluated within a SUD sample, with all other studies seeking to identify CI more generally.

Aim 3: Classification Accuracy

Out of the 14 retrieved studies, 12 reported on classification accuracy data. All reported sensitivity and specificity that varied widely (range: 36%–100%, 2%–100%, respectively). A further two used correlational data to assess associations between screening tools and reference measures. Of the 10 studies that provided overall AUC data, the six that related to the MoCA indicated an acceptable to outstanding ability to detect CI versus respective reference standards. By contrast, the MMSE, another well-known cognitive screening measure, yielded much lower accuracy that ranged from no discrimination to acceptable across two studies.

Although the HASI exhibited excellent discriminant ability (Braatveit et al., Reference Braatveit, Torsheim and Hove2018; To et al., Reference To, Vanheule, Vanderplasschen, Audenaert and Vandevelde2015), this measure was designed to screen specifically for intellectual disability and the reference standards in both instances were restricted to an intellectual disability diagnosis or intellectual cognitive domains. Therefore, classification accuracy of the HASI for detecting CI more broadly in individuals with SUDs remains unknown.

Berry and colleagues (Reference Berry, Shores, Nardo, Sedwell, Lunn, Marceau and Batchelor2021) reported the most extensive psychometric data on the BEAT, a measure specifically developed for use in those with SUDs. The BEAT demonstrated excellent discriminative ability and good sensitivity and specificity at the recommended cut-score of ≤24. However, low prevalence of CI in this group (7.8%) contributed to a low positive predictive power (Abu-Akel, Bousman, Skafidas, & Pantelis, Reference Abu-Akel, Bousman, Skafidas and Pantelis2018). The authors suggest this was due to using a conservative reference standard (i.e., impairment across three tests); however, it is also possible that this relates to sample characteristics (residential participants only), as well as choice of the reference battery (executive tasks only). Given that the prevalence rate in this study is much lower than that in other treatment groups and the SUD literature more broadly (e.g., Copersino et al., Reference Copersino, Fals-Stewart, Fitzmaurice, Schretlen, Sokoloff and Weiss2009), further evaluation of the psychometric properties of the BEAT in broader SUD populations is necessary.

Another cognitive screening tool specifically designed for SUDs, the BEARNI, exhibited good discriminative abilities in the original study but a follow-up analysis demonstrated that despite good sensitivity, the specificity of the tool was poor (Pelletier et al., Reference Pelletier, Alarcon, Ewert, Forest, Nalpas and Perney2018). To this end and given superior MoCA data, Pelletier and colleagues (Reference Pelletier, Alarcon, Ewert, Forest, Nalpas and Perney2018) suggest that the MoCA may be a more suitable choice for routine use.

Less than half of studies provided predictive value data for their screening tools. These data take into account the prevalence of CI in the population of interest. Including this information is crucial as in the event of a mismatch between the prevalence of CI in the screening sample and in individuals attending SUD treatment, classification data may misrepresent a tool’s screening ability (Slater & Young, Reference Slater and Young2013). Of the studies that provided predictive data, the rate of CI across samples varied widely (8%–86%), which is unsurprising given the broad range of study settings and samples. Clinicians must be mindful of the expected prevalence of CI in their particular cohort, as screening tools examined in groups with different prevalence rates may differentially capture CI in their cohort (Molinaro, Reference Molinaro2015).

Two studies relied on correlational data to examine screening measures in individuals with SUD. Medium to large correlations were reported between index and reference measures on the FAB (Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Nicastri, de Andrade and Bolla2010) and LOTCA (Rojo-Mota et al., Reference Rojo-Mota, Pedrero-Pérez, Ruiz-Sánchez de León, León-Frade, Aldea-Poyo, Alonso-Rodríguez and Morales-Alonso2017). However, not all domains corresponded, and no further classification data were provided to support these associations, resulting in only indirect inferences regarding criterion validity. As such, further evaluation of these screening measures is required. There were more consistent medium to large correlations between MoCA scores (total and domain) and reference measures, providing initial evidence for construct validity. The ACE–R, BEAT, and HASI also had promising correlational data between index and reference measures; however, these findings need to be replicated.

Aim 4: Risk of Bias

This review represents the first time that the methodological quality of studies evaluating cognitive screening tools in SUDs have been systematically reviewed. The studies included in this review were assessed overall to have high or unclear risk of bias according to the QUADAS–2, suggesting significant methodological limitations or insufficient reporting. Patient selection represented the most problematic domain with high or unclear risk of bias occurring in 85.71% of studies. This was primarily due to the use of convenience sampling methods and overly stringent exclusion criteria. This included exclusion of individuals who had a history of psychiatric illness, had head injuries, or were on opioid treatment programmes. As individuals with SUDs present clinically with a range of comorbid and co-occurring conditions (see Gooden et al., Reference Gooden, Cox, Petersen, Curtis, Manning and Lubman2020), excluding participants based on these factors has the potential to significantly limit translation of study findings to applied clinical settings.

An additional source of high or unclear risk of bias related to whether index measures were interpreted without the knowledge of the reference standard (i.e., blind ratings), or vice versa, an issue in almost three-quarters of studies. Administration of both measures by the same individual is problematic, as it can inadvertently lead to bias in administration and scoring of measures. This is a clear area in need of improvement in future studies. There were also issues with flow and timing, with nearly half of studies classified as having high or unclear risk of bias. This was primarily due to inappropriate or unclear time intervals between the administration of the index test and reference standard. In a SUD population, administration of both the index and reference standard at a close time interval is critical given the potential of ongoing cognitive recovery with continued abstinence (Stavro, Pelletier, & Potvin, Reference Stavro, Pelletier and Potvin2013). Other issues with flow and timing included not all participants receiving the reference standard, or not accounting for missing participant data, creating an unknown amount of potential bias. It is possible that participants who are more cognitively impaired may drop out more readily due to increased complexity of tasks. It is essential that all aspects of participant flow are tracked, including those invited, those that accept, and those that complete the study, in order to establish whether the population sample reflects the population at large.

The selection of the reference standard was also a source of discrepancy across studies. Given the aim of the study was to include all studies examining CI in general amongst individuals with SUD, three studies focused on specific sub-populations (intellectual disability, Korsakoff syndrome; Braatveit et al., Reference Braatveit, Torsheim and Hove2018; Wester et al., Reference Wester, Westhoff, Kessels and Egger2013; To et al., Reference To, Vanheule, Vanderplasschen, Audenaert and Vandevelde2015). For this reason, the reference standard used for classification was specific and focused, raising concerns on the applicability of identifying CI more broadly in individuals with SUDs.

Another concern regarding reference standards was inconsistency in impairment ratings. Some studies operationalised impairment as ranging from −1 to −2 standard deviations below normative data (the equivalent to a difference of 15th percentile versus 2nd percentile). Other studies required impairment on a certain number of tasks, by domain, or an average overall score. What constitutes psychometric impairment is a source of debate in the neuropsychological community (Schoenberg & Rum, Reference Schoenberg and Rum2017), and this inconsistency is reflected in the studies included. Interestingly, Godefroy et al. (Reference Godefroy, Gibbons, Diouf, Nyenhuis, Roussel, Black and Bugnicourt2014) analysed various methods of classifying impairment and suggested that a cut-off of the 5th percentile is most appropriate. A consensus on how to characterise impairment is needed if analyses of screening measures are to be accurately compared.

Two studies (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Shores, Nardo, Sedwell, Lunn, Marceau and Batchelor2021; Wester et al., Reference Wester, Westhoff, Kessels and Egger2013) presented a unique methodological challenge that was not captured via the QUADAS–2. In both studies the reference standard focused on a limited area of cognitive functioning (executive functioning and memory, respectively), while the index measures evaluated cognitive function more broadly. In both instances, despite the apparent differences in screening and reference tasks, screening measures were able to detect individuals impaired on the reference standard at an acceptable level (AUC ≥75). This suggests that the BEAT and MoCA were able to adequately detect executive functioning and memory impairments, respectively, despite assessing a broader range of skills. It remains unclear how accurately these screening measures detect impairment in other domains. Use of a comprehensive reference standard that includes a range of cognitive domains would allow evaluation of both how well these screens pick up on a range of impairments other than the domain of interest and establish further construct validity.

Overall, findings suggest that clear adherence to STARD criteria was generally poor in studies evaluating the utility of cognitive screening tools in adults with SUDs (Bossuyt et al., Reference Bossuyt, Reitsma, Bruns, Gatsonis, Glasziou, Irwig and Cohen2015; Bossuyt et al., Reference Bossuyt, Reitsma, Bruns, Gatsonis, Glasziou, Irwig and Lijmer2003; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Korevaar, Altman, Bruns, Gatsonis, Hooft and Bossuyt2016). The current results reflect the methodological limitations of the studies in this area to date; not one study was classified as low risk across all domains. This primarily relates to insufficient reporting of study procedure and data as in many cases domains were rated unclear, resulting in risk being unable to be determined. This is a novel and important finding. Not only does it provide direction for further research, but it highlights caution that should be taken in interpretation of the findings to date, given that studies with risk of bias are likely to over- or under-estimate diagnostic accuracy.

Limitations

The current study intentionally set broad limits on search strategy and inclusion criteria to capture as many studies as possible. A key limitation of applying the QUADAS–2 to evaluate risk of bias in captured studies includes dealing with studies that omit key methodological details versus those which report on these more comprehensively and which may be disproportionately penalised as a result. For example, a number of studies did not report how many individuals were approached versus declined to participate, and the reasons for refusal. This could have potentially introduced bias in the recruitment and exclusion of participants in some studies; however, with omission of this information, it cannot be evaluated.

Another limitation is that a comprehensive grey literature search was not incorporated in the search strategy. This was partially mitigated by searching the Psychology Preprint Archive, as well as through inclusion of a publication that was under review and subsequently published (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Shores, Nardo, Sedwell, Lunn, Marceau and Batchelor2021). A more comprehensive grey literature search would have enriched the evidence base for this review by including findings from a broader range of sources, as well as reduce potential publication bias (Paez, Reference Paez2017).

Research Recommendations

While in a research context a homogeneous sample may be useful for interpreting study findings, this does not reflect the rich diversity and heterogeneity of individuals presenting for SUD treatment in health settings. To maximise ecological validity and translation of study findings to applied clinical practice, future studies seeking to validate cognitive screening tools in adults with SUDs should seek to adhere to STARD criteria (Bossuyt et al., Reference Bossuyt, Reitsma, Bruns, Gatsonis, Glasziou, Irwig and Cohen2015; Bossuyt et al., Reference Bossuyt, Reitsma, Bruns, Gatsonis, Glasziou, Irwig and Lijmer2003), while also maximising ecological validity. This includes keeping exclusion criteria to a minimum, such as instances where reduced capacity to provide fully informed consent is evident, or there are acute medical, psychiatric, or other risks that warrant priority treatment. This ensures the study sample is more representative of individuals presenting for the treatment of SUD and captures the potential wide range of co-occurring conditions that may impact cognition in a real-world setting. Studies should also clearly report on sample characteristics (including study setting, substances of misuse, abstinence status) to assist the clinician in understanding whether the cognitive screening tool may be useful for a particular client group. Additionally, including comprehensive classification accuracy statistics supports a greater understanding of the utility of the particular cognitive screening measure. Future studies should: use blinding to ensure objectivity of results; not integrate control with clinical data (as this can conflate results); and provide a clear description of study flow; accounting for any missing data. Future systematic reviews should also adhere to the recently updated PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow and Shamseer2020), which were not available at the time of the current review. Given the wide number of cognitive screening tools available and critiqued in this review, some of which show good promise in use in a drug and alcohol clinical setting (e.g., the MoCA), comprehensively validating existing tools should be an initial first step.

Clinical Recommendations

CI is frequent in individuals with substance use and, given the negative impact on treatment outcomes, should be screened for on treatment entry and periodically over treatment engagement (Bates, Buckman, & Nguyen, Reference Bates, Buckman and Nguyen2013). A cognitive screen used in this context must also be able to capture a range of cognitive disorders, given that the heterogeneity of contributing factors (e.g., ABI, learning or intellectual disability) forms part of a typical client’s presentation. Of the tools reviewed, the MoCA was the most studied and demonstrated the most consistently adequate diagnostic classification accuracy in this population. Practically, the MoCA is brief to administer, evaluates a broad range of cognitive domains, and is used widely across healthcare settings, which may aid in effective communication of health information. It also has alternate versions available, which facilitate re-testing over short periods of time (e.g., at the beginning and end of a detoxification stay, and then entry into outpatient clinics). While the MMSE is another well-known cognitive screening measure, it failed to demonstrate adequate classification accuracy in SUD populations and therefore cannot be recommended for clinical use in this setting. Other measures (e.g., ACE–R and BEAT) have initial promise for use in this area but require further empirical validation before they can be recommended for wide clinical use.

Regardless of the specific screening tool, a key consideration is the risk of over-reliance on a cut-off score alone to determine presence or absence of CI. A cognitive screen is not diagnostic and can only flag clients who may be in need of further assessment, and understanding the context in which the screen was administered is essential in an applied clinical setting. For example, capturing whether a client who performed below the cut-off score on a particular cognitive screen was acutely intoxicated, distracted, or in an uncharacteristically high state of distress is not an uncommon dilemma, and are all relevant details when deciding on clinical recommendations. Incorporating this information can reduce excessive use of resources but is also heavily reliant on clinical acumen. Given the complexities of clinical presentation and subtlety in interpreting cognitive screening results in adults with SUDs, it is recommended that a clinician skilled in the cognitive field provides oversight of cognitive screening processes within this setting, with clinical neuropsychologists ideally situated to perform such a role. Additionally, the development of clear clinical pathways within a service that provide further assessment and comprehensive support for clients identified as at risk of CI is also essential.

Conclusions

The current review provides the first systematic overview of cognitive screening tools utilised in adult SUD populations as compared to an accepted standard criterion of cognitive functioning (e.g., neuropsychological assessment). A strength of this review was the broad inclusion criteria; that is, that CI from a range of aetiologies and client populations was included. The MoCA was the most frequently reported cognitive screening tool, and it exhibited promising classification accuracy data across studies, suggesting the potential for use within this population. However, based on our search strategy and inclusion criteria, studies examining cognitive screening in adults with SUDs were significantly limited in number and quality. Other tools indicate initial promising classification data (ACE–R and BEAT); however, these also require further validation. Overall, given the very small number of studies, diverse sample characteristics, wide range of index measures and reference standards used, as well as high risk of bias identified amongst studies, further evaluation with stronger and more transparent methodological design and reporting is required. Without a clearly established tool to screen for CI, there is the potential that CI may not be systematically evaluated within SUD services, and this may negatively impact individual treatment outcomes. Crucially, future studies need to focus on adhering to the STARD criteria (Bossuyt et al., Reference Bossuyt, Reitsma, Bruns, Gatsonis, Glasziou, Irwig and Cohen2015; Bossuyt et al., Reference Bossuyt, Reitsma, Bruns, Gatsonis, Glasziou, Irwig and Lijmer2003), while also seeking to maximise ecological validity. Positively, there remains promise in the measures utilised to date such as the MoCA, and it is pleasing to see the development of measures specifically designed for use in the SUD population (e.g., Berry et al., Reference Berry, Shores, Nardo, Sedwell, Lunn, Marceau and Batchelor2021; Ritz et al., Reference Ritz, Lannuzel, Boudehent, Vabret, Bordas, Segobin and Beaunieux2015). Future studies should continue to build on the learnings of existing studies to ensure evidence-based measures are available to direct treatment and care of individuals who have comorbid substance use and cognitive needs.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S135561772100103X

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Hunter New England and South East Sydney Local Health District Drug and Alcohol Services for their support in producing this review.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JK and NR contributed equally to conception, design, interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. KK was involved in analysis, interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. AS designed and conducted the systematic search strategy. SB and KA contributed to design and revisions of the manuscript. All authors contributed to final manuscript review.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

KA is supported by a Career Development Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC; APP1141207). KK, NR, SB, AS, and JK have no financial support to disclose.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have nothing to disclose.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

This study did not involve human subject participation.