Toward a ‘nuova maniera di canto’: A New Way of Singing

By the end of the sixteenth century, attempts to recover Greek tragedy led to the new genre of the dramma per musica. For the Florentine Camerata de Bardi, it meant the reinstatement of the antique melopoeia of the Greeks, that is, declamation emphasizing the word and its correct prosody. The Camerata promoted the excellence of monody, echoing the antique doctrine of the ethos proposed by the Pythagoricians, according to which modes could elicit different emotional responses in the listener: viewed as natural to man, monody was thus appropriate for the expression of affect. Later, also, Claudio Monteverdi would emphasise monody alongside polyphony, as he would argue in the preface to the Scherzi musicali of 1607. There, Monteverdi would define ‘Seconda prattica’ as a style that asked the music to amplify the affections already expressed by the poem and, in practice, to serve this latter.

Within the Camerata, Jacopo Peri and Giulio Caccini experimented with the new monody, setting to music some of Ottavio Rinuccini’s dramas: Dafne in 1595 (Peri, Florence; it was set to music in 1608 by Marco da Gagliano as La Dafne in Mantua) and, in 1600, L’Euridice by Peri and Caccini (Florence). It was no mere coincidence that the beginnings of opera privileged the myth of Orpheus, which is at the core of L’Euridice and Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (Alessandro Striggio, Mantua, 1607). Other mythological themes not only confirmed the antique literary heritage that was enjoyed by aristocratic elites but also permitted performances to dodge one of opera’s thornier issues: theatrical verisimilitude. Constantly sung throughout, opera obviously lacks verisimilitude. Thus, exceptions could be made for mythical or superhuman figures who could assume another mode of expression – supposing that these mythological characters could express themselves through song – and for roles viewed as non-normative in relation to the aristocratic milieu: servants and nurses, and other characters of low social origins who provided comic relief to the main plot.

Peri and Caccini knew that the use of monody required aesthetic justifications. In his preface to L’Euridice, Peri explained the use of monody as this ‘new way of singing’ reflecting the Antique manner, to ‘imitate one who speaks through song’ (imitar col canto chi parla).1 Monody reaches for a compromise between true singing and oratorical declamation: hence the expression often used to characterise this style – recitar cantando, which could be translated as ‘recitation in song’, or ‘to recite while singing’, according to Nino Pirrotta.2 The expression recitar cantando appeared for the very first time in the title page of Emilio de’ Cavalieri’s Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo nuovamente posta in musica dal Sig. Emilio del Cavalliere per recitar cantando (Rome, 1600) and in the instructions ‘To Readers’ of the same.3 However, for Cavalieri, its meaning was ‘to stage through song’ (mettere in scena col canto): recitar cantando identified a kind of spectacle instead of a style or a technique.

As a technique, recitar cantando requires vocal flexibility. Its essential feature is the ability to highlight some words through correct pronunciation and diverse techniques of ornamentation. The accompaniment of the voice by the basso continuo should obstruct neither the melody nor the correct perception of the words. Structured by poetic meter, the verbal text allows music to organise itself into a form. The most common verse in Italian poetry is the ‘endecasillabo’, an eleven-syllable verse (hendecasyllable) with its principal accent falling on the tenth syllable: it was already widely used in sixteenth-century pastoral – Tasso’s Aminta or Guarini’s Il Pastor fido, to name only these. Another frequent verse is the heptasyllable (settenario in Italian), a seven-syllable verse with its principal accent on the sixth syllable. Heptasyllables and hendecasyllables are often combined (versi sciolti; blank verses), mostly because both meters have mobile accents: thus they are able to reproduce the different rhythms of spoken language.

Since the Renaissance, versi sciolti were some of the most widespread solutions adopted in poetry, the mobility of their internal accents resembling the delivery of speech and the heightening of expressions. This resemblance is paramount for the foundation of stile rappresentativo – the expression appeared in the title page and the dedication of Caccini’s L’Euridice, published in 1600. In 1699, Andrea Perrucci could still argue that verses ‘of seven and eleven syllables [resemble] prose more than others’.4 In recitar cantando, versi sciolti result in a syllabic style of song in which the melodic embellishments of song are perceived as transgressive elements signalling dramatic tension, just as the few textual repetitions indicate a change in affect and an intensification of said affect. Due to the flexibility of the verse, the rhythm is rather irregular, while the melodic line remains simple and often proceeds stepwise. Stressed syllables coincide with the downbeat of the measure and are often highlighted by values of greater duration. The melodic arc is modelled on the verse, while the cadences function as punctuation, articulating the unity of the text in its more complex poetic periods. What emerges is a mode of expression organised into segments that respect the syntactic trend in a simple linear style, preserving the essential aspect of monody as conveyor of affect through its imitation of speech, here emphasised through musical intonation, and, above all, respecting the prosody. To the elaborated poetic style corresponds a musical treatment characterised by bare simplicity, essentially made on rather elementary sets of melodic and rhythmic patterns. Within this simple melodic outline, the appearance of an unusual rhythmic figure, a specific ornament, or an unusual melodic contour is sufficient to highlight the dramatic intrusion of the affect.

In Caccini’s setting of Rinuccini’s libretto for Euridice, Dafne’s narration of Euridice’s death is treated as a monologue in three parts (see Table 3.1). The first part, A, renders the bucolic setting; the second part, B, introduces the long narration of the snake bite and its fatal consequences; and the third part, C, narrates Euridice’s death.

Table 3.1 Ottavio Rinuccini, L’Euridice, Dafne’s narration ‘Per quel vago boschetto’ (1600). Translation slightly reworked from The Norton Anthology of Western Music, Volume 1: Ancient to Baroque, 7th ed., ed. J. Peter Burkholder and Claude V. Palisca (New York, London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2014), 73

[A] Per quel vago boschetto ove rigando i fiori lento trascorre il fonte degl’allori prendea dolce diletto con le compagne sue la bella sposa, chi violetta o rosa per far ghirlande al crine togliea dal prato e dall’acute spine, e qual posando il fianco su la fiorita sponda dolce cantava al mormorar dell’onda. [B] Ma la bella Euridice movea danzando il piè sul verde prato quando, ria sorte acerba, angue crudo e spietato che celato giacea tra fiori e l’erba punsele il piè con sì maligno dente ch’impallidì repente come raggio di sol che nube adombri, e dal profondo core, con un sospir mortale sì spaventoso ‘ohimè!’ sospinse fore che, quasi avesse l’ale, giunse ogni ninfa al doloroso suono, ed ella in abbandono tutta lasciòssi allor nell’altrui braccia. Spargea il bel volto e le dorate chiome un sudor via più freddo assai che ghiaccio. [C] Indi s’udio il tuo nome tra le labbra sonar fredde e tremanti e, volti gl’occhi al cielo, scolorito il bel viso e i bei sembianti, restò tanta bellezza immobil gelo. | [A] In the beautiful thicket where watering the flowers slowly courses the spring of laurel, she took sweet delight with her companions, the beautiful bride, as some picked violets or roses, to make garlands for their hair in the meadow and among the sharp thorns, while others, lying on their sides on the flowery banks sweetly sang to the murmur of the waves. [B] But the lovely Euridice dancingly moved her feet on the green grass, when, o bitter and angry fate, a snake, cruel and merciless, that lay hidden among flowers and grass, bit her foot with such an evil tooth that she suddenly became pale like a ray of sunshine that a cloud darkens, and from the depths of her heart, a mortal sigh, so frightful, alas, flew forth, that, almost as if they had wings, every nymph rushed to the painful sound, and she, fainting, let herself fall in another’s arms. Then spread over her beautiful face and golden tresses a sweat colder by far than ice. [C] Then your name was heard from her lips, cold and trembling, and, her eyes turned to heaven, her beautiful face and features discolored, this great beauty remained motionless ice. |

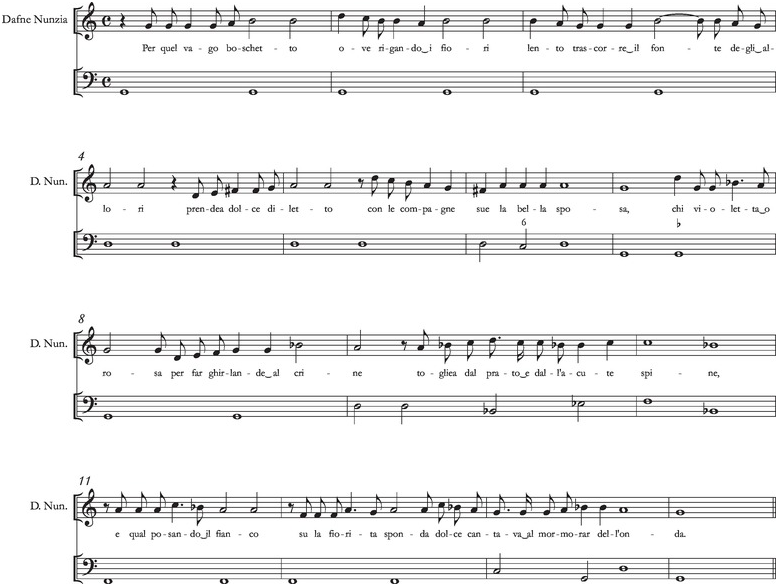

The musical outline of this monologue is modelled along these three thematic areas, but, most of all, the outline of the melodic phrase follows the meaning of the syntactic sentence. From the beginning of the first section, the voice lingers on metric syllables and stretches their duration (see Example 3.1).

Example 3.1 Giulio Caccini, L’Euridice composta in musica in Stile Rappresentativo da Giulio Caccini detto Romano, Dafne’s narration

“A PDF version of this example is available for download on Cambridge Core and via www.cambridge.org/9780521823593”

Shaping the Recitative

In the first half of the seventeenth century, the recitative quickly adapted itself to different needs, as shown for instance with the diffusion of entirely sung dramas in Rome. The use of allegorical figures in the Roman theatre – as in that of Florence – was frequent although here motivated by counter-reformationist propaganda, with historical–hagiographic plots addressing a morally edifying content. In Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo (Agostino Manni and Cavalieri; Rome, Oratorio dei Filippini, 1600), the allegorical figures of Body and Soul are subjected to trials of strength and attempt to resist the snares of worldly life. This allegorical action ‘per recitar cantando’ was intended to be staged, yet with a severe style of recitative in accordance with the nature of the plot. On the other hand, the dramma musicale Sant’Alessio (Giulio Rospigliosi and Stefano Landi, Rome, 1631) relies on a recitative style flexible enough to establish different levels of comedy. In Act II scene 8, the Devil appears to the pageboy Marzio, a simpleton. Mistaking the Devil for a hermit, Marzio begins to mock him. The scene is in two parts, the first with a monologue delivered by the Devil, the second with a dialogue between him and Marzio. The treatment of the recitative differentiates the refined, ironic astuteness of the Devil from the good-natured simplicity of Marzio; during their dialogue, declamation is increasingly treated in a histrionic manner. As for the monologue, the absence of well-defined melodic pattern first evokes a sense of statism. The Devil, however, shows off an unprecedented virtuosity with his canto di sbalzo, a style of singing privileging wide intervals and jumps from one extreme to another of the tessitura. As shown in Example 3.2, Marzio’s intervention causes the mood of the scene to depart from the fearsome gravity of the infernal world, resulting in two different comic tones: on the one hand Marzio’s vulgarity, on the other the refined irony of the Devil’s witty retorts loaded with subtle double-meanings that escape Marzio.

Example 3.2 Stefano Landi, Il Sant’Alessio, Act II, sc. 8, dialogue for Demonio e Marzio

“A PDF version of this example is available for download on Cambridge Core and via www.cambridge.org/9780521823593”

This search for variety in the recitative is symptomatic of a need to renew musical declamation. Commenting on his own opera La catena d’Adone (Ottavio Tronsarelli, Rome, 1626), Domenico Mazzocchi alluded to the negative effects on the audiences of the recitative, which led him to compose mezz’arie as a way to ‘break the tedium of the recitative’.5 This led composers and poets to search for alternative modes of musical declamation, for more varied forms with better defined melodic and rhythmic outlines. Giovanni Battista Doni also evoked in his Trattato della musica scenica (written 1633–1635), a style ‘more vague and adorned than others, and full of varied intervals, which truly requires the scene to avoid tedium and to bring even more delight to the hearers, in order to better express all those different feelings that are subjected to this kind of verse and musical imitation’.6 As we will see, the recitative would be increasingly submitted to periodic interruptions taking the form of brief episodes with a more singable style in which vocal virtuosity and lyricism would prevail: the aria.

‘Like sprouts from the roots’: The Aria, Born from the Recitative

In 1744, Francesco Saverio Quadrio wrote that the aria should follow the recitative and have a ‘relationship with [it], and rise from the same, as sprouting from the root’.7 While this describes a well-established practice in eighteenth-century opera, the consolidation of the relation between recitative and aria was strengthened during the previous century.

The text of a libretto alternates between two main formal models assuming different functions: recitative and aria. A quick glance at any printed page of a libretto reveals the different types of verses chosen either for the recitative or the aria. During the seventeenth century, recitative and aria gave rise to hybrid structures. Brief and compact strophes were usually preferred for an aria. The poetic meters of these strophes were of various sorts but remained regulated by rhymes following a fixed pattern that facilitated the identification of the strophe in the flow of the discourse. The aria ‘Quanto vale e quanto può’ from Antonio Cesti’s Il Tito (Nicolò Beregan, Venice, 1666) is made up of twelve octosyllables (ottonari: x8 a8 a8 x8 a8 x8 | y8 b8 b8 y8 b8 y8) followed by a series of heptasyllables and hendecasyllables (see Table 3.2).

Table 3.2 Nicolò Beregan, Il Tito, Act I, sc. 13, Tito’s aria ‘Quanto vale e quanto può’ (1666)

Atto I Scena xiii Galeria con statue. Tito Quanto vale e quanto può [aria] bella bocca di cinabro, s’a goder d’un vago labro Giove in cigno si cangiò. Bella bocca di cinabro quanto vale e quanto può. Che non opra e che non fa il candor di vaga fronte, s’il gran nume d’Acheronte fé prigion di sua beltà. Il candor di vaga fronte che non opra e che non fa. Tito, ma che vaneggi? [recitative] Questi i trofei del tuo valor saranno? Dunque chi di Sion domò l’orgoglio, chi la Siria atterrò, l’Asia distrusse, fia prigionier d’un guardo, e de la fama diràssi in Campidoglio ch’armata di lusinghe, in breve gonna del mondo il vincitor vinto ha una donna? Taci, lingua, che parli? Del bell’idolo mio così ragioni? […] | Act I Scene xiii Hallway with statues. Titus How mighty and how powerful is a beautiful vermilion mouth, if, to enjoy a sweet kiss even Jove turned into a swan. Beautiful vermilion mouth, how mighty and how powerful. What can it not do, what can it not achieve, the candour of a lovely face, if the great god of Acheron was made a prisoner of its beauty. The candour of a sweet face, what can it not do, what can it not achieve. Titus, but what are you raving about? Will these be the trophies of your valour? Thus, he, who tamed the pride of Zion, who brought down Syria and destroyed Asia, should he be made prisoner by a glance, and of his fame should it be said on the Capitol that, armed with charms, in short skirt, a woman overcame the conqueror of the world? Be silent, tongue, what are you saying? Is this how you reason about my beautiful idol? […] |

A syntactically autonomous form, the aria emphasises the dramatic context of specific situations: displays of lyrical effusion, enunciations of paradigmatic sentences, and other instances of rhetorical effects.

During the seventeenth century, strophes could contain from four to ten verses with poetic meters varying between heptasyllables and hendecasyllables. There were also quinari (pentasyllables, i.e., five-syllable verses) and quaternari (tetrasyllables, four-syllable verses), often arranged in polymetric strophes. In general, numeri chiusi (closed numbers) such as arias and choruses were modelled on the forms of the old ballata, the madrigal, and the Anacreontic ode – the latter, popularised in Italy by the poet Gabriello Chiabrera, often used other types of verses than the hendecasyllable usually found in mixed strophes that combined verses of different meters.

Recitative and aria distinguish themselves not only by form and style but also by the varied pace of the plot’s progression. The recitative allows for a dynamic integration of the dialogue into the flow of action; the aria, instead, halts the action, allowing externalisation of affect or a contemplative moment of introspection. The relationship between recitative and aria is regulated by a mechanism that allows the tension accumulated during the recitative to be released during the emotional response of the character in the aria. Such displays of affect (anger, joy, despair, etc.) make the aria the culminating point of the scene.

The affect privileged in the aria is made all the more noticeable by the choice of a melodic line easy to remember and frequently repeated in specific verses. However, the vocal line in the aria does not necessarily model itself on the prosody of the poem, nor does it attempt to emphasise the meaning of each verse. Instead, it privileges the general meaning of the strophe or strophes and their main affect. Thus, each aria possesses an unmistakable physiognomy with a distinctive rhetoric and melodic profile.

With the aria, the recitative creates a ‘system of contrasts’ paramount to the construction and unfolding of the drama. The peripeties of the plot are developed through the contrasting succession of arias along different, if not opposing, moods. The drama unfolds along this succession, so that the spectrum of affects can be ascribable to a paradigmatic system of emotions. A change of meter signals the transition from recitative to aria: the latter is characterised by rhythmic uniformity, the instrumentation is enlivened, and ritornelli are played between each strophe while the basso continuo follows the vocal line with increased animation.

These musical features bring us back to a fundamental issue of verisimilitude on stage, not only complicated by the recitar cantando but also by the textual and melodic repetitions which were also considered to be unnatural. Thus, songs that fulfilled a function of musica di scena (stage music) – and that would also have been sung in spoken theatre – and other situations that elicited song from the character, be it with a prayer or a moment of invocation, were appreciated: exemplary cases are the aria ‘Possente spirto’ in Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (Act III), in which the hero sings to placate Caronte; Arnalta’s ‘Oblivion soave’ in Monteverdi’s Incoronazione (Act II scene 12); or Romilda’s aria ‘O voi che penate’ from Francesco Cavalli’s Xerse (Act I scenes 3–4).

A ‘rounded frame’: The Function of the Intercalare

The first formal models of the aria were borrowed from the traditional forms of Italian poetry – for example, the terzina (a three-verse strophe of hendecasyllables using the chain rhyme aba | bcb | cdc |, etc.) and the ottava rima (a strophe of eight verses usually on the rhyme scheme abababcc). The terzina was also known as terza rima, terzina dantesca, or terzina incatenata (chained terzina), as in the aria ‘Possente spirto’ in Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (see Table 3.3).

Table 3.3 Alessandro Striggio, La favola d’Orfeo, Act III, Orfeo’s aria ‘Possente spirto e formidabil nume’ (1607).

Libretto published in Libretti d’opera italiani dal Seicento al Novecento, Giovanna Gronda and Paolo Fabbri (Milan: Mondadori, 1997), 37

Orfeo Possente spirto e formidabil nume, (a) senza cui far passaggio a l’altra riva (b) alma da corpo sciolta in van presume, (a) non viv’io no, che poi di vita è priva (b) mia cara sposa, il cor non è più meco, (c) e senza cor com’esser può ch’io viva? (b) A lei volt’ho’l camin per l’aër cieco, (c) a l’inferno non già, ch’ovunque stasis (d) tanta bellezza il paradiso ha seco. (c) […] | Almighty spirit, formidable God, without whom to pass onto the other bank a soul, freed from its body, presumes in vain, I do not live, no, since she was deprived of her life, my dear wife, my heart is no longer with me, and without a heart, how could I be alive? For her I have set foot through the dark air, yet not into Hades, since where may be such beauty, only paradise can be. […] |

The rigorous terzina contrasts with more plastic and flexible forms – for example, those addressing a theatrical topos destined to become the object of great emulation: the lamento. Originally a literary topos, the lamento was known through famous instances: Armida’s lament (Tasso, Gerusalemme liberata, Canto XVI), or Olimpia and Fiordiligi’s laments in Orlando furioso (Ariosto, Canto X [lamento di Olimpia]; Canto XLIII [lamento di Fiordiligi]). The only surviving piece from Rinuccini and Monteverdi’s opera L’Arianna (Mantova, 1608) is its celebrated lamento sung by its eponymous heroine. A long monologue divided in several sections, Arianna’s lamento adopts mostly a syllabic style for its sinuous and unpredictable vocal line, obeying the poetic prosody. The recitar cantando of this lamento requires vocal flexibility – the ability to draw attention to the words through emphatic pronunciation and to signal its most poignant moments with diverse vocal techniques. The monologue’s organisation does not feature a pre-established formal model: instead, the piece proceeds by juxtaposed sections greatly contrasting with each other. Each section focuses on the presentation of one main affect exacerbated by rhetorical effects that shape the vocal line: anaphora, repetition, peroration, to name only these. Example 3.3 gives the beginning of this lamento, with the recurrence of some verses fulfilling the role of a refrain. Monteverdi’s later opera, Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria (Giacomo Badoaro, Venice, 1640), also displays a lament for Penelope (‘Di misera regina,’ Act I scene 1), in which repeated verses also function as refrains. Of course, Monteverdi was not the only one to emulate the theatrical topos of the lament: other examples are found in La regina sant’Orsola (Andrea Salvadori, music by Marco da Gagliano; Florence, 1624), La Flora (Andrea Salvadori, music by Marco da Gagliano and Jacopo Peri; Florence, 1628), and L’Andromeda (Benedetto Ferrari, Francesco Manelli; Venice, 1637).

Example 3.3 Claudio Monteverdi, L’Arianna, Arianna’s lament

“A PDF version of this example is available for download on Cambridge Core and via www.cambridge.org/9780521823593”

The refrain became an essential element of the aria. A privileged model is the aria adopting the form of the ballata, which relies structurally on the refrain. The ballata’s distinctive feature is the repetition of the first verse, or the first couplet at the end of the strophe, and the rhyme between the last verses of the strophe and the first ones of the repeated verse: such repetition is called intercalare or ritornello.8 Arias with intercalare were frequent in Venetian operas: an example is Oronta’s lament in Artemisia (Act III scene 4; Nicolò Minato and Cavalli; Venice, 1657). The aria consists of two strophes separated by an instrumental episode. Its intercalare corresponds to the verse given at the beginning and end of the first strophe (‘Dammi morte o libertà’); it is then repeated in the final verse of the aria (see Example 3.4).

Example 3.4 Francesco Cavalli, Artemisia, Act III, sc. 4, Oronta’s lament

“A PDF version of this example is available for download on Cambridge Core and via www.cambridge.org/9780521823593”

Seemingly simple at first sight, the structure of these arias with intercalare can adopt more complex combinations: the length of the intercalare can be extended when made of more than one verse; also, its recurrences can vary. Some arias can have two different texts for the intercalare, that is, one for each strophe. An essential feature for the melody of the intercalare is its simplicity, making it easily memorable for the listeners and triggering the pleasure of identification.

The aria also took from the sixteenth-century madrigal the epigrammatic character of its final couplet, a very efficient rhetorical expedient. Such epigrammatic verses often appear at the beginning of a strophe as a banner for the displayed affect. In Ceffea’s aria from Scipione Affricano (Act I scene 14; Minato and Cavalli; Venice, 1664), the conclusive couplet functions as the intercalare (mm. 22–31 and 63–73; see Example 3.5). The intercalare also allows for rhetorical and structural emphasis when used within the blank verses of a recitative. Highlighting specific verses, the intercalare creates sections in the textual flow. This can nevertheless lead to some ambiguities, as it may obscure the relationship between recitative and aria. In Scipione Affricano (Act I scene 13), the verse ‘Chiedi, o bella, che vuoi?’ occurs twice during the recitative (see Example 3.6). This osmotic relationship between recitative and aria is one of the most fascinating traits of seventeenth-century opera: it is first of all about poetry – more specifically, about drama structured by poetry.

Example 3.5 Francesco Cavalli, Scipione Affricano, Act I, sc. 14, aria for Ceffea

“A PDF version of this example is available for download on Cambridge Core and via www.cambridge.org/9780521823593”

Example 3.6 Francesco Cavalli, Scipione Affricano, Act I, sc. 13, recitative for Scipione

“A PDF version of this example is available for download on Cambridge Core and via www.cambridge.org/9780521823593”

Another technique consists in the poetic arrangement of aggregates of verses within the fabric of the recitative, out of which the composer can write a mezz’aria (half-aria), also called aria cavata, that is, an aria ‘extracted’ from the recitative. In this case, the declamatory style proper to the blank verses of the recitative is momentarily abandoned. What emerges instead is a strophic passage characterised by rhythmic periodicity similar to that of the aria. In Xerse (Minato and Cavalli; Act I scene 7; Venice, 1655), the king begs for Romilda’s love in a short strophe made of heptasyllables. Cavalli singles out this passage from the recitative by treating it as a brief arioso in the very middle of the scene (see Example 3.7).

Example 3.7 Francesco Cavalli, Il Xerse, Act I, sc. 7, mezz’aria for Xerse

“A PDF version of this example is available for download on Cambridge Core and via www.cambridge.org/9780521823593”

Such a treatment of the poetic text found its origins in the Monteverdian dramatic recitative, itself reflecting the legacy of the madrigalesque tradition in which blank verses were often declaimed not so much in a brisk manner as at a more sustained tempo, allowing, when necessary, some lingering on a word or on an expression isolated through musical and rhetorical effects. Indeed, the versatile uses of the intercalare explain the variety and flexibility of formal models that define the aria during the seventeenth century. Table 3.4 presents the main formal categories determined by the number of strophes in an aria and by the specific uses of the intercalare – including instances of formal structures without any intercalare (the verses carrying the intercalare are underlined in the table).

Table 3.4 Main categories of arias in relation to the use of the intercalare

N. Minato–F. Cavalli, Scipione Affricano, II, 6 (1664) Ericlea Dite, dite, dolci aurette, (a) odorose, placidette, (a) perché mai (b) son penosi i miei respiri, (c) e si cangiano in sospiri? (c) | Ericlea Tell me, tell me, sweet breezes, fragrant, pleasant, why on earth is my breathing so painful, and has changed into sighs? |

N. Minato–F. Cavalli, L’Orimonte, I, 12 (1650) Fleria Com’io t’ami non so. settenario Trovar di te più freddo “ un amante chi può? “ Come io t’ami non so. “ | Fleria How I can love you I do not know. Who could find a lover that is colder than you? How I can love you I do not know. |

B. Ferrari–F. Manelli, La maga fulminata, II, 6 (1638) Pallade [1st strophe] Quand’è in tempesta il mar teme morte il nocchier; quando placido appar ha d’arrichir, non di perir pensier. Se flagello divin non scote il rio, ei non conosce più cielo né dio. [2nd strophe] Ecco femina rea dorme negli error suoi; e dall’impura idea scarcera vizi ed imprigiona eroi. Ma non usa uno stil sempre la sorte, e ogni umano piacer termina in norte. | Pallade When the sea is stormy, the sailor fears death; when it appears calm his thoughts turn to riches, not to peril. If the divine scourge does not stir the wicked, he no longer knows neither heaven nor god. Lo the guilty woman sleeping upon her erroneous ways; and by her impure thought she releases vices and imprisons heroes. But fate does not always work in just one way, and every human pleasure ends in death. |

G. Faustini-F. Cavalli, La Calisto, I, 2 (1651) Calisto Verginella io morir vo’. Stanza e nido per Cupido del mio petto mai farò. Verginella io morir vo’. Scocchi Amor, scocchi se può tutte l’armi per piagarmi, ch’a la fine il vincerò. Verginella io morir vo’. | Calisto I wish to die a young virgin. A bed and nest for Cupid never will my heart be. I want to die a young virgin. Let Love fire, let him fire, if he can, all his weapons to wound me, for in the end I still will defeat him. I wish to die a young virgin.* |

G. Faustini–F. Cavalli, Euripo, III, 5 (1649) Euripo [1st strophe] Cessate dal piagarmi, occhi omicidi, troppo barbari siete, morto voi mi volete: serbate i dardi a debellar gl’infidi. Cessate dal piagarmi, occhi omicidi. [2nd strophe] Lontananza non giova, io peno, io moro, gran trofeo, gran valore voler estinto un core che trae da’ vostri sguardi il suo ristoro. Lontananza non giova, io peno, io moro. | Euripo Stop wounding me, murderous eyes, you are too barbaric, you want me dead: save your arrows to crush the infidels. Stop wounding me, murderous eyes. Distance does not help, I suffer, I die, it is a great trophy, a great valour indeed to wish death upon a heart that takes its healing from your glances. Distance does not help, I suffer, I die. |

* Translation slightly reworked from Francesco Cavalli, La Calisto, ed. Alvaro Torrente and Nicola Badolato (Kassel, Basel, London, New York: Bärenreiter, 2012), XXXII

Expanding Forms and Structures

In Cavalli’s Xerse, the aria of Romilda, ‘O voi che penate’ (Act I scene 3–4), constitutes a fascinating case of musica di scena. The aria occurs between two scenes and is interrupted on three occasions by passages in recitative, first by Arsamene, then by Elviro, and finally by Xerse. The form of the aria adapts itself to the unfolding of the plot, following the reactions of the three men to the song of the young Romilda (see Table 3.5).

Table 3.5 Nicolò Minato, Il Xerse, Act I, sc. 3–4, Romilda’s aria ‘O voi che penate’ (1654).

Translation slightly reworked from Francesco Cavalli, Il Xerse, ed. Hendrik Schulze and Sara Elisa Stangalino (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2019), LI

[SCENA TERZA] Arsamene Non ti partir. Romilda O voi – ‹Cantando.› Arsamene Quest’è Romilda. Romilda – o voi che penate. Elviro Da voi amata? Arsamene Sì, non parlar più. Romilda O voi che penate per cruda beltà, un Xerse mirate, – SCENA QUARTA Xerse, Arsamene, Elviro, Romilda ‹e› Adelanta su la loggia. ‹Xerse› (Qui si canta il mio nome?) ‹Romilda› – – che di ruvido tronco acceso sta, e pur non corrisponde altro al su’ amor che mormorio di fronde. Di rami frondosi lo sterile Amor, con vezzi dannosi punge i baci sul labbro al baciator. È di Cupido un gioco far che mantenga un verde tronco il foco. | [THIRD SCENE] Arsamene Do not leave. Romilda O you … ‹Singing.› Arsamene This is Romilda. Romilda … O you who suffer … Elviro Your beloved? Arsamene Yes; be quiet. Romilda O you who suffer … for a cruel beauty, look at him, Xerse … FOURTH SCENE Xerse, Arsamene, Elviro, Romilda and Adelanta on a balcony. ‹Xerse› (Someone here is singing my name?) ‹Romilda› … who is in love with a rugged tree although nothing answers to his wooing but the whisper of the leaves. From the leafy branches the cold Amor, with harmful caresses bites with his kisses the lips of the kisser. It is Cupid’s game to maintain a fire from green wood. |

Arsamene’s and Elviro’s recitative interjections are inserted twice during the first verses of Romilda’s aria ‘O voi che penate’. Only later, Xerse enters unexpectedly during the first strophe sung by Romilda. Another aria from the same opera, ‘Ombra mai fu’, sung by Xerse (Act I scene 1), displays an unusual form of extraordinary effectiveness. The aria occupies the entire scene. Made of four quinari, its opening strophe functions as a repeat. The two central strophes, each one made of six verses (abbaCC), evoke a madrigalesque form with their hendecasyllabic and heptasyllabic verses, each strophe ending with a rhyming couplet. The contrast with the repeat is highly significant as regards the form and the meter. The instrumental ritornello provides a frame for the different sections of the text (see Table 3.6).

Table 3.6 Nicolò Minato, Il Xerse, Act I, sc. 1, Xerse’s aria ‘Ombra mai fu’ (1654). Translation slightly reworked from Francesco Cavalli, Il Xerse, ed. Hendrik Schulze and Sara Elisa Stangalino (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2019), XLIX–L

Xerse Instrumental ritornello Ombra mai fu A di vegetabile cara ed amabile, soave più. Instrumental ritornello Bei smeraldi crescenti, B frondi tenere e belle, di turbini o procelle importuni tormenti non v’affligano mai la cara pace, né giunga a profanarvi Austro rapace. Instrumental ritornello Mai con rustica scure B1 bifolco ingiurïoso tronchi ramo frondoso; e se reciso pure fia che ne resti alcuno, in stral cangiato o lo scocchi Dïana o’l dio bendato. Instrumental ritornello Ombra mai fu A di vegetabile cara ed amabile, soave più. Instrumental ritornello | Xerse Never was a shade of any plant more dear and lovely, more sweet. Beautiful green foliage, tender and lovely branches, of whirlwinds and storms the unwelcome tortures shall never afflict your precious peace, nor should ever the predatory Auster defile you. Never shall, with rustic cunning, the harmful yokel cut your delicate twigs; and should they be chopped after all, be it that they are changed, as arrows, to be shot by Diana or the blindfolded god. Never was a shade of any plant so dear and lovely, more sweet. |

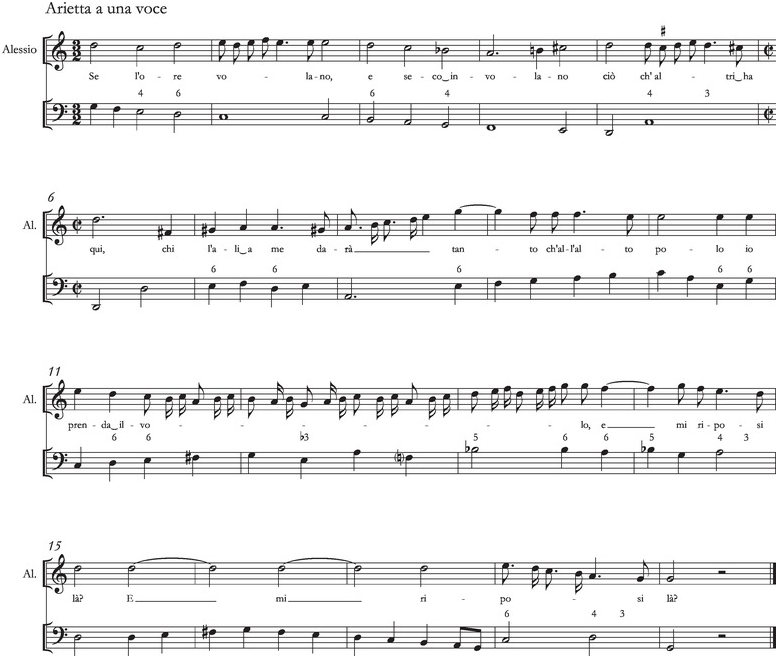

Another sophisticated instance of the use of the ritornello is featured in an aria from Sant’Alessio, ‘Se l’ore volano’ (Act I scene 2). Hiding in the cellar of his home, Alessio sings of his desire to be freed from the chains of worldly life. The aria is divided into three strophes made of seven verses (pentasyllables and heptasyllables), with a ritornello played between each strophe. Each of its three strophes is subdivided into two sections: the first three verses differ for each strophe, while the last four are identical (‘Chi l’ali a me darà | tanto ch’all’alto polo | io prenda il volo, | e mi riposi là?’). The melody is identical for each strophe but undergoes a major change on the fourth verse to signal the return of the repeated verses (see Example 3.8).

Example 3.8 Stefano Landi, Il Sant’Alessio, Act I, sc. 2, aria for Alessio

“A PDF version of this example is available for download on Cambridge Core and via www.cambridge.org/9780521823593”

During the second half of the century, itinerant theatrical companies and cosmopolitan composers disseminated the model of the Venetian opera in Europe, allowing for the development of its forms and vocal styles. In Cesti’s operas, the separation between recitative and aria is fully realised, the aria being the culmination of the scene. In Venice, Rome, and Naples, the aria became the privileged locus for lyric effusion, asserting its melodic profile. The expansion of its dimensions went hand in hand with new developments in its formal models. The short intercalare of the early Venetian opera, often made of one or two verses, could be extended to the size of a whole strophe and become the focal point of the aria. For instance, Armidoro’s aria ‘Deh rendetemi, ombre care’ (Act III scene 15) from Difendere l’offensore o vero la Stellidaura vendicante (Perrucci, Francesco Provenzale; Naples, 1674) is made of two strophes, A and B, the strophe A (repeated after the strophe B) playing the role of an expanded intercalare (see Table 3.7).

Table 3.7 Andrea Perrucci, Difendere l’offensore, ovvero La Stellidaura vendicante, Act III, sc. 15, Armidoro’s aria ‘Deh rendetemi, ombre care’ (1685)

Armidoro Instrumental introduction Deh rendetemi, ombre care, Episode A il mio ben che mi rapiste; o bellezze uniche e rare, ahi da me come spariste? Instrumental interlude Rispondetemi, larve cortesi: Episode B chi l’estinta mia rubbò? Deh qual nume, ch’io forse offesi, da’ miei lumi me l’involò? Instrumental interlude [Repeat of the first strophe] Episode A1 | Please return to me, o dear shadows, the loved one that you have taken from me; o beautiful features, unique and rare, woe, how did you vanish from me? Answer me, gentle spirits, who has robbed me of my deceased? Please, which god that I might have offended, took her away from my sight? |

Both poetic and musical structures are simple: first, the instruments enunciate the melody that will be repeated during the first strophe, section A. Repetition plays a structural role: the instrumental episode that follows the first strophe is based on the melody of the introduction, closing section A and introducing section B. A new melodic material is presented, not so much contrasting with the one presented in strophe A as elaborating the last section of A. The second occurrence of the instrumental interlude is followed by the reappearance of the entire strophe A, now subjected to variations and alterations to the original melodic line. The whole results in a tripartite form: A-B-A’, the foundation of the so-called aria col da capo, which would become the dominant form of the aria in the eighteenth century.

During the seventeenth century, an increasing number of formal possibilities and stylistic features allowed arias to become privileged vehicles for the display of affect and emotions: scenes of lament, of madness, of sleep (aria del sonno), invocations, and prayers. An important category is the comic aria. In Venetian operas, these arias were integrated within comic episodes, often located at the end of an act or near a change of scenery or action, thus creating an entertaining intermission between the serious episodes of the dramma per musica. Comic arias were intended for characters frequently embroiled in quid pro quos or involved in degrading situations, and whose low origin – servants, buffoons, nurses, and the like – originated with stock figures of the commedia dell’arte. The verses of comic arias often rely on linguistic manglings, colloquial phonetics, or stuttering, enabling mockeries against the simple-minded or those affected by physical deformities, old bachelors unable to control their lustful desires, and so on.

In Giasone (Giacinto Andrea Cicognini and Cavalli, Venice, 1649; Act I scene 7), the servant Demo sings an aria (see Table 3.8), the comic effect of which is ensured by syllables issued in fits and starts – ‘so-so-’, for example – but also (in dialogue with Oreste) from an obscene allusion: Demo’s stuttering prevents him from completing words starting with ‘ca-’, implying an obscene rhyme with ‘strapazzo’.

Table 3.8 Giacinto Andrea Cicognini, Giasone, Act I, sc. 7, Demo’s aria ‘Son gobbo, son Demo’ (1649).

Libretto published in Libretti d’opera italiani dal Seicento al Novecento, Giovanna Gronda and Paolo Fabbri (Milan: Mondadori, 1997), 129–30

[ritornello] Demo Son gobbo, son Demo, son bello, son bravo, il mondo m’è schiavo, del diavol non temo, [ritornello] son vago, grazioso, lascivo, amoroso; [ritornello] s’io ballo, s’io canto, s’io suono la lira, ogni dama per me arde, e so- so- so- so- arde, e so- so- so- Oreste E sospira. Demo So- so- so- so- so- so- Demo e Oreste Arde e sospira. [ritornello] Oreste Linguaggio curioso. Demo Sei troppo, troppo, troppo frettoloso, e se farai del mio parlar strapazzo, la mia forte bravura saprà spezzarti il ca- Oreste Oibò. Demo Il ca - po in queste mura. | I am a hunchback, I am Demo, I am handsome, I am great, the world is my servant, I don’t fear the devil, I am attractive, graceful, lascivious, loving; when I dance, when I sing, when I play the lyre, every woman will burn for me and he- he- he- burn for me and he- he- he- and heave a sigh. He- he- he- he- he- he- burn and heave a sigh. Odd language. You are too, too, too hasty, and if you mock my speech within these walls, my tough bravery will know to kick you in your ba- oh my! … backside. |

The ‘Epilogue’ of the Passion

Demonstrated by their formal variety and their increasing number in operas, arias became from the middle of the seventeenth century the focal point for the musical expression of emotions. Their placement within a scene was also motivated by their dramatic function. An aria could be performed at the opening, at the end, or in the middle of a scene. In the first case, it was called aria di sortita; the second case was referred to as aria d’entrata or aria di congedo; and the third case was aria mediana. Presenting the character, the aria di sortita possessed a signaletic function. The affect was represented through specific repetitions (intercalare, repetition of the first strophe) and rhetorical effects intended to impress the memory of the listener. The aria d’entrata (or di congedo) reasserted the scene’s dominant affect and constituted its climax. Located at the end of the scene, it allowed the singer to gather applause without interrupting the action. Such risk of interruption was much higher with the aria mediana: thus, its frequency diminished by the end of the century while the aria d’entrata became predominant; by singing the aria before leaving the stage, the character did not interrupt the action but rather put it on ‘stand-by’. Furthermore, the aria d’entrata could ideally represent an affect as a universal, absolute quality. As a result, the more the aria focused on such universal truths, the more it could be recontextualisable in another operatic work: thus, arias could be removed from the original dramma per musica and reused in another opera. It could also happen that a singer might favour a specific aria particularly apt to showcase his or her vocal abilities; singers would integrate such arias in their own repertoire, with the possibility of performing these on different occasions: this introduced the concept of the aria di baule, which gained popularity during the eighteenth century.9

Indeed, the aria d’entrata became the prevalent type during the eighteenth century, but it was also the object of criticism. Emblematic is the case of Ludovico Antonio Muratori (Della perfetta poesia italiana; Modena, Soliani, 1706), who described the aria as a ‘ridiculous thing’, since it entailed the repetition of verses even when the action required a character’s immediate departure from the scene. Muratori’s objection is exemplary of the issues surrounding the nature of inverosimiglianza raised by the defenders of Italian poetry, who considered these poetic repetitions an obstacle to the unfolding of the dramatic action.

Nevertheless, the aria performed at the end of the scene became the most appreciated formula: in 1715, Jacopo Martello writes that ‘a musician ought never depart without a trill of roundelay. Whether plausible or not is of little concern’.10 As summarised in 1783 by Stefano Arteaga, such an aria was ‘the climax or epilogue of the passion’,11 and should therefore not be placed at the beginning of the scene nor in the middle: the aria had to be placed at the end of the scene, for it would not be acceptable (verosimile) to have at the beginning of a scene a character already at the height of their passion. The affect should increase during the scene, through the use of dialogues, for instance; thus its climax should be reached with the aria at the end of the scene.

The Verse as Index of Affect

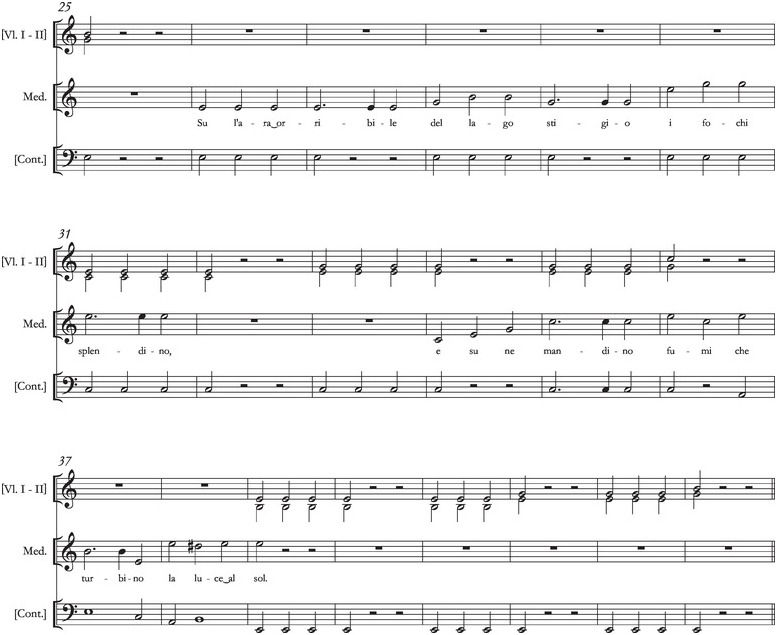

Specific dramatic situations or roles such as otherworldly spirits, satirical or pastoral figures, or comic characters can be efficiently emphasised through the poetic means of proparoxytone verse (verso sdrucciolo in Italian), in which the antepenultimate syllable is stressed. The verso sdrucciolo is also used in structural scenes, such as prologues or finales of acts. In the prologue of L’Orimonte (Minato and Cavalli, 1650), infernal allegorical characters sing a duet of proparoxytone verses (see Table 3.9), heightening a sense of terror.Medea’s scene in Cavalli’s Giasone (Act I scene 15) is another instance that relies on the verso sdrucciolo for the invocation of spirits (see Example 3.9). Comic situations also benefit from the expressive power of proparoxytone verse. In Cavalli’s Artemisia (Act I scene 16), Alindo sings an aria expressing his great delight in receiving a flower from Artemisia, since he hopes that she will return his love. Four scenes later (Act I scene 20), in the same garden, the servant Niso sings the very same intercalare previously sung by Alindo (see Table 3.10). Old Erisbe then sings the strophes, while Niso, snatching some flowers, mocks the woman, alluding to her withered face. Bitter disillusionment at the loss of youth emerges from the sententious couplet that closes both stanzas, while the intercalare is sung by Niso in an obviously mocking fashion.

Table 3.9 Nicolò Minato, L’Orimonte, Prologue, Confusione and Volturio Spirito’s duet ‘Saprò confondere’ (1650)

| Confusione | Confusion |

| Saprò confondere | I shall confuse |

| gl’arbitri e l’anime, | free will and souls, |

| il mostro essanime | the bloodless monster |

| non caderà. | shall not fall. |

| Volturio Spirito | Spirit of Greed |

| Saprò diffondere | I shall spread |

| tempesta orribile, | horrible storms, |

| l’angue terribile | the terrible snake |

| non perirà. | shall not perish. |

| […] | […] |

Example 3.9 Francesco Cavalli, Il Giasone, Act I, sc. 15, aria for Medea

“A PDF version of this example is available for download on Cambridge Core and via www.cambridge.org/9780521823593”

Table 3.10 Nicolò Minato, Artemisia, Act I, sc. 16, Alindoro’s aria ‘Cari, cari vegetabili’, and Act I, sc. 20, Niso and Erisbe, ‘Cari, cari vegetabili’ (1657). Translation slightly reworked from Francesco Cavalli, Artemisia, ed. Hendrik Schulze and Sara Elisa Stangalino (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2013), XLIX–L, LX–LXIV

Act I, scene 16 Alindo Cari, cari vegetabili, se ben rigida è colei ch’a me vi diè, pur da me séte adorabili. Cari, cari vegetabili. […] Vezzi amabili di chi fa col suo rigor nel mio cor piaghe insanabili. Cari, cari vegetabili. | Alindo Dear, dear plants, though unyielding is she who gave you to me you still are adorable to me. Dear, dear plants. […] Lovable instruments of her who, with her hardness, causes in my heart incurable wounds. Dear, dear plants. |

Act I, scene 20 Niso Cari, cari vegetabili. Erisbe I danni degl’anni sono, o belle, irreparabili: le beltà non son durabili. Pur liete godete pria che fuggan gl’anni labili: le beltà non son durabili. Niso Cari, cari vegetabili. | Niso Dear, dear plants. Erisbe The damage caused by the years is, oh beauties, irreversible: beauty is not durable. Yet happily let’s enjoy before the fleeting years go past: beauty is not durable. Niso Dear, dear plants. |

Back to the Greeks: Prologues and Choruses

At least until the middle of the century, the dramma per musica was introduced by a prologue populated by allegorical or mythological figures. Its strophic structure attests to its derivation from spoken theatre, where prologues were also sung, at least originally. In the prologue of Peri’s Euridice, the allegorical figure Tragedy declares in seven quatrains of hendecasyllables in rima crociata (ABBA) her wish to ban the retelling of the cruellest events and to arouse instead ‘sweeter emotions in the heart’ by tempering the singing on ‘happier chords’ (see Table 3.11). As is typical in allegorical prologues, homogeneity characterises poetry and music: in Euridice’s prologue, the first verse of each quatrain enunciates a well-defined melodic line, which proceeds with regularity if not placidity; indeed, the allure of the prologue must be adapted to the solemnity of the occasion. An instrumental ritornello separates strophes sung on the same melodic line; only the use of some improvised variations, such as melismas affecting the dynamics and melodic turns, enliven these otherwise identical strophes. While not notated in the score, these improvised melismas function not only as ornamentation but also as signals: they are strategically located at the end of each quatrain on the stressed syllable, highlighting the ending of the strophe and the beginning of the instrumental ritornello.

Table 3.11 Ottavio Rinuccini, L’Euridice, Prologue, La Tragedia, ‘Io, che d’alti sospir vaga’ (1600)

LA TRAGEDIA Io, che d’alti sospir vaga e di pianti, (A) spars’or di doglia, or di minacce il volto, (B) fei negl’ampi teatri al popol folto (B) scolorir di pietà volti e sembianti, (A) non sangue sparso d’innocenti vene, non ciglia spente di tiranno insano, spettacolo infelice al guardo umano, canto su meste e lagrimose scene. Lungi via, lungi pur da’ regi tetti, simolacri funesti, ombre d’affanni: ecco i mesti coturni e i foschi panni cangio, e desto nei cor più dolci affetti. Or s’avverrà che le cangiate forme non senza alto stupor la terra ammiri, tal ch’ogni alma gentil ch’Apollo inspiri del mio novo cammin calpesti l’orme, Vostro, Regina, fia cotanto alloro qual forse anco non colse Atene o Roma, fregio non vil su l’onorata chioma, fronda febea fra due corone d’oro. Tal per voi torno, e con sereno aspetto ne’ reali imenei m’adorno anch’io, e su corde più liete il canto mio tempro, al nobile cor dolce diletto. Mentre Senna real prepara intanto alto diadema onde il bel crin si fregi, e i manti e seggi degl’antichi regi, del tracio Orfeo date l’orecchia al canto. | TRAGEDY I, who, eager for loud sighs and tears, my face now filled with sorrow, now with threats, once made the faces of the crowd in great theatres turn pale with pity, no longer of blood shed by innocent veins, nor of eyes put out by the insane Tyrant, unhappy spectacle to human sight, do I sing now on a gloomy and tear-filled stage. Away, away from this royal house, funereal images, shades of sorrow: behold, I change my gloomy buskins and dark robes to awaken in the heart sweeter emotions. Should it now come to pass that these great forms in the world admired with great amazement, so that each gentle spirit that Apollo inspires will thread in the tracks of my new path, Yours, Queen, will be so much laurel, that perhaps not even Athens or Rome gathered more, an ornament worthy of those honoured tresses, a frond of Phoebus between two crowns of gold. Thus, changed, I return, and with a serene countenance I, too, adorn myself for the royal wedding, and temper my song with happier notes, sweet delight to the noble heart. While the royal Seine is preparing a lofty crown to adorn your lovely hair, and the mantles and thrones of ancient kings, lend an ear to the song of the Thracian Orpheus. |

Interspersed with instrumental ritornelli, this strophic structure was a frequent arrangement during the first half of the seventeenth century. Later, the prologue would assume more flexible and elaborate forms, often incorporating the dialogue. In the 1660s, the prologue would begin to disappear, while the opening scene’s significance would increase. Altercations and squabbles between divinities would be abandoned in favour of opening scenes featuring a civil community with a chorus celebrating the actions of the hero.

Commentative Voices

Choruses organised in strophes with well-defined melodies are usually favoured for entrance scenes and finales of acts or demarcative scenes, that is, scenes which separate individual episodes. When interpolated within the dramatic action, the chorus assumes a generic function of commentary, following the tradition of antique tragedy but with more restraint than in its original model.

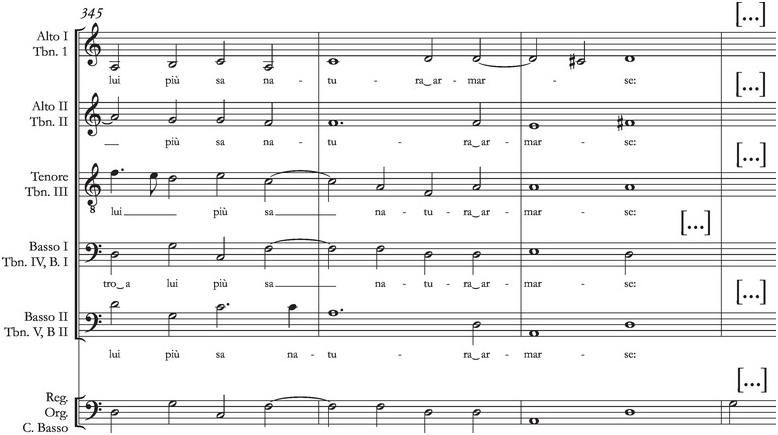

In one of the choruses of L’Orfeo, Monteverdi avoided declamation and favoured instead a moment of pure spectacle: it occurs at the end of the third act as an intermede between two episodes (Orfeo’s dialogue with Caronte and the dialogue between Proserpina and Plutone). After having made Caronte fall asleep, Orfeo descends into the Underworld where the chorus of spirits comments on the virtues of mankind. Setting the first strophe to a five-voice imitative polyphony characteristic of the late Renaissance madrigal with its dense interweaving of voices, Monteverdi creates a grandiose aural effect. The second section of the chorus brings a new musical texture, its sixth verse split in the typical manner of the Venetian coro battente or spezzato, before all voices reunite again in the seventh verse with some concession to vocal virtuosity (see Example 3.10).

Example 3.10 Claudio Monteverdi, L’Orfeo, Act III, chorus for the Spirits

“A PDF version of this example is available for download on Cambridge Core and via www.cambridge.org/9780521823593”

Venetian opera of the second half of the century provides instances of the chorus in opening scenes being assigned to a collective entity or to conflict episodes such as battles, which justify the presence of people or armed men, respectively, rather than otherworldly figures. In these instances, the function of the chorus contextualises and exalts historical events. Devoid of a prologue, Muzio Scevola (Minato and Cavalli; Venice, 1665) starts in medias res with an entrance scene (Act I scene 1) depicting the battle near the Tiber: ‘Tiber at the Sublician bridge. Melvio, Horatius Cocles fighting on the bridge. Publicola, Roman soldiers and sapers cut the bridge from one side. Porsenna, Tarquinius Superbus and the army of Tuscany from the other.’ A chorus delivers a series of senari (six-syllable verses with the main accent on the fifth syllable): ‘Si rompa, si franga, | reciso dall’onda | a l’oste ch’innonda | il varco rimanga. | Si rompa, si franga … ’.

Finally, one may wonder at the horizon offered by the complex spirit of experimentation proper to the seventeenth century and its legacy at the dawn of the Arcadian reform. Setting aside all considerations regarding the ‘purification’ of Italian poetry and its forms, I believe that the answer lies in attempts to conceive musical forms aimed at the expression of human affections in an increasingly universal and standardised sense. This resulted in a reduction of the variety of poetic and musical forms, and in the consolidation of a paramount structural dichotomy: the clear-cut distinction between recitative and aria, and the rise of the aria col da capo as the imitation of affect able to provide for the audience an edifying purpose and a cathartic effect: indeed, in order to be able to recognise the passions in ourselves, it helps to observe them on stage. Which was, after all, the very raison d’être of Greek theatre.