Introduction

Dementia is more of an aggregation of symptoms affecting memory, cognition, and social abilities on a severe magnitude than a disease per se. These adverse effects on the performance of the activities of daily life result from physical changes in the brain. Dementia can further be of several types, depending on the underlying pathological condition and symptoms, as described in Table 1. 1 , 5 - 14 Dementias are progressive in nature. The sufferers may have trouble with short-term memory in the beginning, which evolves into a total loss of memory. While the symptoms of dementia are various, impairment in at least two of the following core mental functions should be there for the condition to be considered as dementia:

▪ memory

▪ language and communication

▪ ability to focus

▪ capability to reason and judge

▪ visual perception 2

Table 1 Various types of dementia

Apart from dementia, cognitive impairment may manifest without any functional impairment. This syndrome is known as mild cognitive impairment.Reference Petersen, Smith, Waring, Ivnik, Tangalos and Kokmen 3 Studies with community samples have revealed that its progression to dementia is about 12–15% annually, on average.Reference Tuokko and Frerichs 4

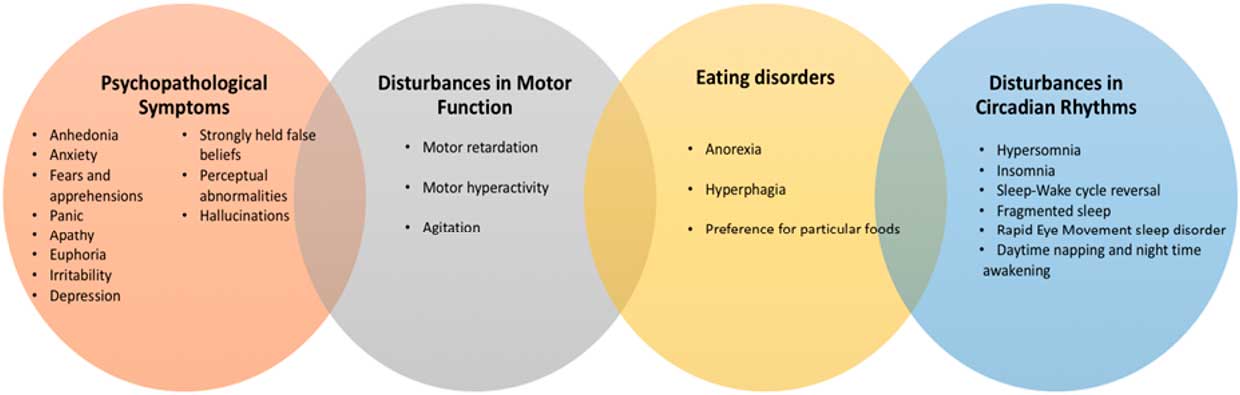

The behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) are a conglomeration of non-cognition-associated symptoms and behavioral problems manifested in patients suffering from dementia. These are also known as “neuropsychiatric symptoms.” BPSD comprise a significant component of dementia independent of subtype. In the beginning stages of cognitive impairment, BPSD appear in about 35–85% of patients with mild cognitive impairment.Reference Cerejeira, Lagarto and Mukaetova-Ladinska 15 These symptoms occur very frequently. About 90% of demented patients clinically present with at least one of the BPSD. These symptoms may fluctuate during the progression of dementia. BPSD may vary in the short term, either via pharmacological and/or nonpharmacological approaches or spontaneously.Reference Colombo, Vitali, Cairati, Vaccaro, Andreoni and Guaita 16 The BPSD concept is rather descriptive and does not encompass any diagnostic entity. Instead, the concept takes into account a crucial clinical paradigm of dementia that has not been considered for research and pharmacotherapeutics with appreciable attention.Reference Finkel, Costa e Silva, Cohen, Miller and Sartorius 17 BPSD can present themselves in various forms, as illustrated in Figure 1.Reference Robert, Onyike and Leentjens 18 – Reference Cohen-Mansfield, Marx, Dakheel-Ali, Regier, Thein and Freedman 23

Figure 1 Different forms in which BPSD can present themselves.

Considering each of the symptoms at an individual level in dementia patients, the most predominant BPSD are depression, apathy, irritability, agitation, and anxiety, while the rarest are disinhibition, hallucinations, and euphoria. Of these, anxiety, apathy, and depression are the most clinically significant symptoms.Reference Cerejeira, Lagarto and Mukaetova-Ladinska 15 Over the years, research in the field of dementia has not yielded any remarkable success in disease-modifying pharmacotherapeutic interventions. Therefore, pharmacological approaches targeting BPSD have emerged as a coveted avenue of research among scientists worldwide.

Pharmacotherapeutic Approaches for Clinically Significant BPSD

Depression

Almost 50% of patients with late-onset depression have been reported to have cognitive impairment. The incidence of depression in sufferers of dementia is between 9 and 68%. Depression has been considered to be both a risk factor and a presentation of dementia.Reference Muliyala and Varghese 24 About 40% of patients suffering from Alzheimer’s-type dementia develop significant depression. However, dementia-linked depression varies in its presentation as compared to depression without dementia. Dementia-associated depression may be less severe, and the symptoms may not be persistent. Also, suicidal thoughts generally do not occur in dementia-related depression. 25 Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors have been prescribed for the treatment of dementia-linked depression.

The Cumbria Partnership National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust—popularly known as the CPFT—lays down treatment regimens for BPSD. For depression in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the prescribed first-line therapy is sertraline and citalopram (SSRIs). However, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency contraindicates citalopram if the patient is on antipsychotic therapy. Mirtazapine constitutes the second-line therapy. It is one of the very few tetracyclic antidepressants approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). It is classified as a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant. In case of Parkinson’s dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies, the CPFT prescribes citalopram as first-line therapy and sertraline as second-line therapy. 26 – Reference Ferguson 28

Randomized controlled trials have studied the efficacy of imipramine, citalopram, and moclobemide with good results.Reference Reifler, Teri and Raskind 29 – Reference Roth, Mountjoy and Amrein 31 Fluoxetine treatment in dementia-linked depression did not prove to be significantly better than placebo.Reference Petracca, Chemerinski and Starkstein 32 Sertraline did not show any beneficial effects, and in fact caused an increased incidence of adverse events.Reference Rosenberg, Martin and Frangakis 33 Therefore, SSRIs are not suitable for use in dementia-linked depression.

Addition of SSRIs to enhance the activity of cholinesterase inhibitors might have some positive effects on performance of daily chores in demented patients.Reference Mowla, Mosavinasab, Haghshenas and Haghighi 34 Cholinesterase inhibitors improve some behavioral symptoms in demented patients. Treatment with donepezil has been reported to slow down the progression of mild cognitive impairment in depressed patients with AD.Reference Lu, Edland and Teng 35

A metaanalysis employed imipramine and clomipramine (TCAs) with sertraline and fluoxetine (SSRIs) in five studies of patients with depression-linked dementia. The response to treatment and remission was greater than that in the placebo control groups in the combined sample, but a remarkable decrease in cognitive scores was reported with the use of TCAs in both studies.Reference Thompson, Herrmann, Rapoport and Lanctôt 36 Newer therapeutic interventions with promising results in the treatment of dementia-linked depression encompass anticholinergics, anticonvulsants, and memantine (a glutamatergic antagonist of NMDA receptors).Reference Gellis, McClive-Reed and Brown 37

Reduction in the levels of acetylcholine (ACh) leads to decreased cholinergic activity in patients with dementia. It has been implicated in increased incidence of BPSD, especially depression.Reference Garcia-Alloza, Gil-Bea and Diez-Ariza 38 Cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine) have been employed successfully to elevate levels of ACh in the brains of mildly to moderately demented patients.Reference Singh, Kaur, Kukreja, Chugh, Silakari and Singh 39 , Reference Mehta, Adem and Sabbagh 40 A recent randomized controlled trial reported improvement in dementia-linked depression (as per the Hamilton Depression Scale) by employing rivastigmine along with fluoxetine with respect to placebo-treated subjects.Reference Mowla, Mosavinasab, Haghshenas and Haghighi 34

The NMDA receptors regulate the plasticity of synapses by playing the role of a coincidence detector. Only synapses that are specific for activation of NMDA receptors, temporally and spatially, experience plastic changes secondary to Ca2+ influx after immediate unblocking of Mg2+. This in turn affects memory and cognitive processes. The voltage dependence of Mg2+ is so pronounced that under pathological conditions it exits the NMDA channel upon even slight depolarization, thereby hindering memory and learning.Reference Koch, Szecsey and Haen 41 Glutamatergic overstimulation results in a phenomenon known as “excitotoxicity,” which results in neuronal damage by increasing neuronal calcium load. Memantine is a noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist that antagonizes the adverse actions of increased levels of glutamate in the brain. Due to this property, it has found a place as a valuable therapeutic agent in patients with dementia. Memantine has been proven to improve cognitive abilities and overall outcomes in individuals suffering from AD. It is currently being marketed for the treatment of moderate to severe AD and has been approved by the FDA.Reference Reisberg, Doody, Stoffler, Schmitt, Ferris and Mobius 42 A recent metaanalysis and reviewReference Maidment, Fox, Boustani, Rodriguez, Brown and Katona 43 for the use of memantine in the treatment of depression associated with dementia showed remarkable improvements on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory, with very few adverse effects.

Often, there is a decrease in concentrations of GABA in the cortical regions of the brain of demented patients. Pharmacotherapeutic measures that elevate levels of GABA have been reported to ameliorate mood disorders.Reference Buhr and White 44 Clinical studies employing carbamazepine (anticonvulsant; voltage-gated Na+ channel blocker) have shown contradictory results for treatment of BPSD, or data on dementia-linked depression have not been reported.Reference Sink, Holden and Yaffe 45 Preliminary clinical trials of lamotrigine (an anticonvulsant) in demented elderly patients also demonstrated betterment of symptoms of depression and agitation.Reference Sajatovic, Ramsay, Nanry and Thompson 46

Apathy

Apathy is a neuropsychiatric symptom of dementia that is characterized by loss of interest, general demotivation, and a lack of persistence. In other words, the patient becomes apathetic. Apathy may present itself either as a symptom of depression or as a separate entity. 47 Over the years, apathy has gotten less research attention with regard to other BPSD. Although the awareness about this condition is increasing among researchers, its treatment protocol still remains deficient.

A recent four-year study associated apathy with a rapid decline in cognitive abilities in sufferers of AD.Reference Starkstein, Jorge, Mizrahi and Robinson 48 Another recent study reported that patients with mild cognitive impairment were more susceptible to progress to AD after a year if they also presented with apathy.Reference Robert, Berr and Volteau 49

Increasing our knowledge of physical alterations in the brain has gathered research focus in the field of apathy. One postmortem study revealed that patients with AD who had prolonged apathy were more prone to have more neurofibrillary tangles than patients without apathy.Reference Marshall, Fairbanks, Tekin, Vinters and Cummings 50 Clinically, apathetic sufferers of dementia may even have genetic differences from demented patients who do not present with apathy. A recent studyReference Monastero, Mariani and Camarda 51 reported that Alzheimer’s patients were more likely to bear the ApoE e4 allele if they were also apathetic. Although the neurobiology of apathy is yet to be fully described, abnormal functioning of frontal systems is considered to be crucial. The medial (anterior cingulate) circuit is linked with motivation disorders, including apathy.Reference Cummings 52 The underlying cause of apathy in dementia has also been attributed to deficits in the medial frontal and limbic cholinergic systems. Dopaminergic pathways that affect frontal-subcortical activation have also been suggested as being important in the development of apathy.Reference Cummings and Back 53

The CPFT prescribes sertraline and citalopram as first-line therapy for apathy in Alzheimer’s-linked dementia, Parkinson’s dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies. Donepezil, rivastigmine (cholinesterase inhibitors), and galantamine (cholinesterase inhibitor and allosteric modulator of nicotinic cholinergic receptors) have been put forward as second-line drugs for treatment of apathy related to dementia. 26 , Reference Birks 54 , Reference Lilienfeld 55

There is less evidence suggesting the suitability of pharmacotherapeutic interventions for treatment of the dementia-linked apathetic state. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors have shown the best results. Some evidence suggesting the efficacy of memantine has been reported, but there is relatively little evidence for the efficacy of cholinergic stimulants, calcium antagonists, or antipsychotics. However, an evidence base exists to support the prescription of anticonvulsants or antidepressants.Reference Berman, Brodaty, Withall and Seeher 56

A randomized controlled clinical trialReference Herrmann, Rothenburg and Black 57 has reported that methylphenidate (CNS stimulant; norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor) was related to a small but significant improvement on the Apathy Evaluation Scale compared to the placebo control group, though the treatment did elicit some adverse effects (e.g., cough, elevated blood pressure, and osteoarticular pain).Reference Rea, Carotenuto, Fasanaro, Traini and Amenta 58 However, modafinil, another monoaminergic compound, did not demonstrate any marked improvement with respect to apathy.Reference Frakey, Salloway, Buelow and Malloy 59

A multicenter, placebo-controlled, crossover trial involving bupropion (norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor) for the treatment of apathy in Huntington’s-associated dementia was conducted, and it revealed that there was no significant difference in treatment response between the drug-treated and placebo groups at baseline or endpoint. 60 , Reference Gelderblom, Wüstenberg and McLean 61 A 12-week, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial was begun in 2010 using bupropion for the treatment of Alzheimer’s-type dementia. 62 This study has been completed, but the results have not been made available as of yet.

Anxiety and agitation

Anxiety is a very common presentation among BPSD. It is associated with behavioral disturbances and poor quality of life. Its incidence is generally higher in cases of vascular dementia as compared to Alzheimer’s-type dementia. Its intensity reduces as the dementia progresses to a severe stage. Anxiety as a behavioral symptom of dementia is seen in 5–21% of demented patients, while 8–71% of patients present with symptoms related to anxiety. It is seen more in demented patients than in those who do not have dementia.Reference Seignourel, Kunik, Snow, Wilson and Stanley 63

The anxiety symptoms in AD have been believed to constitute either a psychological response to the progressive decline in cognitive abilities or were considered to be generally caused by other symptoms of the illness (e.g., concentration problems, agitation, or paranoia). Alternatively, they may be due to the stress caused by progressive loss of cognition in susceptible individuals with such premorbid risk factors as personal or familial psychiatric abnormalities.Reference Chemerinski, Petracca, Manes, Leiguarda and Starkstein 64 Agitation may also be seen in demented patients as the disease progresses, but it is generally absent during the advanced stages of dementia. It is predominantly seen in AD. It is characterized by general emotional distress, restlessness, physical or verbal outbursts, pacing, and shredding of paper or tissues. 65

The CPFT prescribes citalopram as a first-line therapy for moderate agitation/anxiety in Alzheimer’s dementia. The second-line drugs include trazodone (serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor), lorazepam (benzodiazepine, with positive allosteric modulatory effect on GABA–A receptors), mirtazapine, and memantine. The first-line therapy for severe agitation/anxiety is risperidone (antipsychotic; dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT2A antagonism). The starting dose of risperidone is 500 µg od (British National Formulary dose is 250 µg bid), and the maximum dose is 1 mg bid. The second-line agents include aripiprazole (atypical antipsychotic; partial dopaminergic D2 agonist, partial 5-HT1A agonist, 5-HT2A antagonist, 5-HT7 antagonist, partial 5-HT2C agonist); olanazapine (atypical antipsychotic; dopaminergic D2 antagonist, serotoninergic 5-HT2A antagonist); memantine, and lorazepam. The starting dose for olanzapine is 2.5 mg od, while the maximum dose is 1 mg bid. The starting dose for aripiprazole is 5 mg od, and the maximum dose is 10 mg/day. 26 , Reference Frecska 66 – Reference Seeman 72

For dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease, the CPFT prescribes citalopram and sertraline as first-line therapeutic agents for moderate agitation/anxiety. The second-line therapy is based on the use of rivastigmine, donepezil, galantamine, and lorazepam. For severe agitation/anxiety, the first-line medications include quetiapine (atypical antipsychotic; dopaminergic D2 antagonist, serotoninergic 5-HT2A antagonist). The second-line agents are rivastigmine, donepezil, galantamine, and lorazepam. The starting dose for quetiapine is 25 mg od, and the maximum dose is 10 mg/day. The starting dose for lorazepam is 0.5–1 mg bid (oral/im), while the maximum dose is 1 mg bid (oral/im). 26 , Reference Seeman 72

There are several new entities that have been registered in clinical trials worldwide for treatment of agitation in Alzheimer’s-type dementia, as presented in Table 2. 73 - 79

Table 2 Entities currently in clinical trials for treatment of agitation associated with Alzheimer’s-type dementia

Analgesics in the treatment of agitation associated with dementia

Another one of-a-kind study reported that systematic management of pain remarkably diminished agitation in moderately to severely demented patients. This 8-week study demonstrated a significant reduction in agitation in the drug-treated group compared to controls. Analgesia was also shown to be advantageous in decreasing the overall severity of BPSD. These results offered the hope that effectively managing pain could do away with the extensive prescriptions of psychotropic drugs. Four different analgesic interventions were employed in that study: 1 g of paracetamol (tid, orally), 20 mg/day of morphine (orally), 10 µg/h of buprenorphine (transdermal patch), and 300 mg/day of pregabaline (orally). 80 , Reference Husebo, Ballard, Sandvik, Nilsen and Aarsland 81

Special considerations for treatment of BPSD

The CPFT reports that the involvement of anticonvulsants and/or mood stabilizers is limited by a lack of substantial evidence to support their efficacy. However, they can be prescribed in patients for whom other treatment approaches have been ineffective or are contraindicated. Antipsychotic therapy, if needed, should be strictly based on the use of atypical antipsychotics. Atypical antipsychotics in high doses or typical antipsychotics in normal doses worsen cognition, elevate the risk of cerebrovascular events threefold, and may also cause a twofold rise in the rate of mortality. The use of haloperidol (first-line treatment for aggression) and/or risperidone is contraindicated in established or suspected Parkinson’s dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies, as these patients are susceptible to their sensitivity to antipsychotic therapy. Additionally, significant extrapyramidal side effects have also been observed. In BPSD associated with vascular (stroke-related) dementia, cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine are not approved, and should therefore not be used. Apart from this, there is lack of significant evidence related to vascular dementia-related BPSD. The treatment strategies for other types of dementia (except for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and dementia with Lewy bodies) are not yet fully elucidated due to the lack of an evidence base. 26

The ABC Approach for Management of BPSD

The CPFT has proposed an integrative ABC approach for managing neuropsychiatric symptoms in demented patients.

A (primary care responsibility)

If the patient has BPSD associated with a steady decline in cognitive abilities for a period of more than 6 months along with a short history (less than 1 week) of delirium, the treatment for acute underlying medical problems is sought. These acute problems may be urinary tract infections, chest infections, and effects of withdrawal from certain drugs or alcohol. If the patient does not present with a short history of delirium, then approach B is initiated.

B (optional primary care responsibility with secondary care support, if needed)

The PAAID approach is employed, which aims at treatment of:

▪ P: physical problems (pain, infection)

▪ A: activity abnormalities (impaired performance of daily chores)

▪ A: anticholinergic burden is estimated

▪ I: intrinsic behaviors of dementia (wandering aimlessly)

▪ D: depression, psychosis, and anxiety

If the behavioral problems still remain unresolved, then nonpharmacological interventions are put in place (e.g., one-to-one care, aromatherapy, distraction). If the symptoms still persist, drug intervention is instituted. Pharmacological treatment is employed only if there is marked depression, psychosis, or significant distress. Treatment can also be administered if the patient’s condition is putting those in his/her vicinity at risk of harm. However, pharmacological approaches are not used in mild to moderate conditions. Identification of the target group of symptoms is very crucial at this stage. If the symptoms are still not alleviated, it could mean that the underlying cause is Parkinson’s dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies. If these conditions are diagnosed, then the related appropriate treatment is started. If the caregiver is unsure about it, approach C (get advice from a specialist) is then initiated. 26

Conclusions

Dementia is a major cause of depreciation in quality of life among geriatric patients. It leads to progressive loss of cognitive abilities and memory. Due to the lack of a knowledge of the involved biological targets and diversification of dementia into several subtypes, its disease-modifying therapy has still not been elucidated. The current pharmacotherapeutic approaches provide only symptomatic relief. As dementia advances, it gets augmented with other troubling symptoms—that is, BPSD. About 90% of sufferers of dementia present with at least one of these symptoms, regardless of their dementia subtype. These include a wide array of symptoms: psychopathological symptoms, motor function abnormalities, eating disorders, and unbalanced circadian rhythms. These contribute further to decreasing the quality of life in demented patients. The pharmacotherapeutic interventions for the clinically significant BPSD have been given in Figure 2.

Due to the lack of disease-modifying pharmacological interventions, the treatment of BPSD has been taken up as a viable approach for betterment of quality of life pertaining to demented patients. Amid the plethora of BPSD, apathy, depression, anxiety, and agitation are relatively more prevalent than the others. Before beginning treatment for BPSD, the subtype of dementia and the target group of neuropsychiatric symptoms should be established. Also, nonpharmacological interventions should be applied whenever necessary. The current therapeutics for BPSD include independent and/or combination prescription of existing antidepressants, antipsychotics, and cholinergic agents. These drugs are not successful at completely alleviating symptoms, and they may cause many adverse effects. In addition, extra care should be taken when prescribing these agents to geriatric patients.

Research in the treatment of BPSD has undergone remarkable growth over the past few years. However, most studies are based on the use of existing drugs. There is a strong need to develop newer agents that would effectively tackle these symptoms. BPSD provide bright avenues for research, both in terms of drug discovery as well as development and clinical trials.