Introduction

It might be said that the study of ancient Mesopotamia owes a great deal to the lavatory (a.k.a. toilet). The many thousands of cuneiform tablets from the royal libraries of Ashurbanipal, excavated in the 1850s on the mound Kuyunjik at Nineveh and now housed in the British Museum, form the foundation stone of the field of Assyriology. Many of them were discovered in Room XLI of the palace of Sennacherib, Ashurbanipal's grandfather, a chamber that was identified by its excavator, Austen Henry Layard, as an archive room (he called it the Chamber of Records). Because different fragments of the same tablets were found scattered on both sides of the wall that separated Room XLI and the unconnected gallery Room XLIX, the pioneer Assyriologist and archaeologist George Smith assumed that Room XLI was not the tablets' place of origin, but that they had fallen into this space from the storey above when the ceiling and floor collapsed during the burning of the citadel of Nineveh in 612 b.c. Because it is now thought unlikely that the building actually had an upper storey, the mound of tablets lying on the floor of Room XLI must have owed its presence there to some other reason; perhaps it was a dump where the Babylonian intelligence agency discarded what it did not need.Footnote 1 The chamber's function can then be determined by its size, location and layout, rather than by its contents. Accordingly John Russell, the modern expert on Sennacherib's palace, considers that the “original use of Room XL, judging from the wall niche, was as a bathroom” (Russell Reference Russell1991: 66–67).Footnote 2 Room XLI lay between this bathroom and a large reception room (XXIX), so Layard's Chamber of Records, the final resting place of much of the Assyrian royal libraries, can now be identified as the anteroom of a royal lavatory.

No one doubts that ancient Mesopotamian palaces were provided with bathrooms and lavatories. But how was it for the common people? Were their dwelling houses also equipped with such amenities? In his book on The Ancient Mesopotamian City, Marc Van De Mieroop called attention to the threat that contaminated water supplies posed to life in ancient urban centres. He wrote (Reference Van De Mieroop1997: 159):

Then there was the problem of human waste. Archaeological evidence of latrines in private houses is lacking, and public toilets do not seem to have existed either. People could defecate in fields and orchards …

When reading this for the first time a disturbing vision arose in which even the grandest of Babylonian ladies, when feeling a little discomforted at night, had to leave her chamber, cross the courtyard, unbolt the front door, hurry along the streets, wake the guard at the city gate, ignore his curses, avoid the attentions of wild dogs and other animals, finally to find relief in a convenient field or date-grove. Since then, in a chapter entitled “Urban form in the first millennium BC”, Heather Baker has made general statements about lavatories in Babylonian houses that help to dispel this troubling picture (Baker Reference Baker and Leick2007: 73):

Bathrooms tend to be found in private houses which are of a larger than average size, and only very few built toilets have been securely identified. Presumably other households made use of portable containers … The built toilets consisted of baked brick fixtures over a deep vertical shaft … [and] tended to be located in the least accessible part of the house.

At the time of reading Van De Mieroop's book, the problem of sewage disposal in urban Mesopotamia struck me as deserving examination, so I began to explore the archaeological and Assyriological evidence for lavatories. The enquiry focused in particular on the Akkadian word asurrû, which the modern dictionaries translate as “foundation structure, lower (damp) course of a wall” (CAD A 350), “Grundmauer” (AHw 77), “‘lower course, footing’ of wall” (CDA 26). A short book review made a preliminary survey of the evidence, concluding that asurrû was “part of the foundation structure that could drain off water from the lavatory and at the same time give shelter to nesting snakes and mongooses” (George Reference George1999: 551). This identification has had some influence,Footnote 3 but has never been properly substantiated. The present paper began as a belated attempt to make good that lack by collecting attestations of asurrû that associate it with drains. It developed into an examination of the Assyriological evidence for lavatories and sewers, concluding with a study of the keyword asurrû. Before tackling the philology, I shall briefly describe some of the archaeological evidence (see further McMahon 2015, unavailable at the time of writing).

Lavatories and sewers in Mesopotamian archaeology

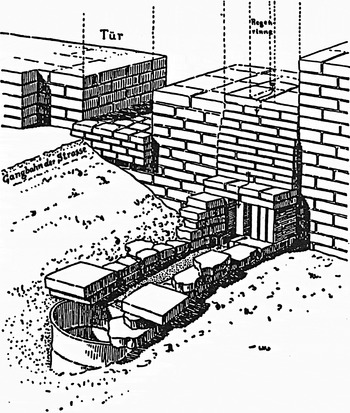

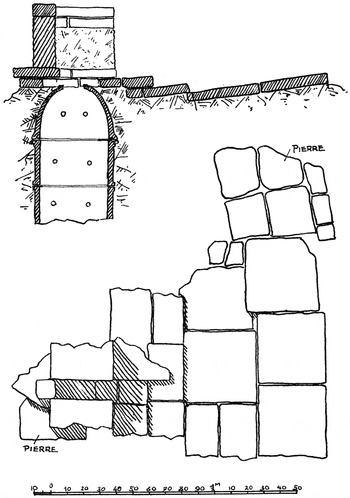

A thorough presentation of the archaeological evidence for ancient Mesopotamian drainage installations has been published by Christiane Hemker as Altorientalische Kanalisation (Reference Hemker1993). Her study makes it clear that already by the middle of the third millennium the technology of urban drainage was highly developed in southern Mesopotamia and her illustrations show a variety of installations that could be used to carry away sewage. One such structure is the ring-drain or seepage-pit (Sickerschacht), a vertical shaft lined with a column of perforated tubular pottery rings, one on top of the other (Fig. 1). Such drains are found in many periods and at many sites, from fourth-millennium Warka to first-millennium Babylon (Hemker Reference Hemker1993: 128–67). The technology first appears in dwelling houses in the third millennium, at Fara and Khafaje. Typically a ring-drain drained waterproofed floors and was sometimes surmounted by a slotted brick structure that could hardly be anything other than a pedestal lavatory. Good examples of these structures already occur in the mid-third millennium: at Tello, in a building of uncertain function dated by Hemker to the Ur I period (p. 132 no. 260c, here Fig. 2), and later at Tell Asmar, in a building contemporary with the Earlier Northern Palace (p. 131 no. 259b with Abb. 433; Lloyd Reference Lloyd, Delougaz, Hill and Lloyd1967: 186 with pl. 41b; here Fig. 3). Neither building was certainly a private house.

Fig. 1 Early Dynastic period ring-drain at Khafaje, Temple Oval M 44:8 (from Delougaz Reference Delougaz1940: 124 fig. 113). The cap is missing, affording a view down inside the drain

Fig. 2 Cross-section and plan of a pedestal lavatory above a ring-drain, Tello (from de Genouillac Reference de Genouillac1936: pl. XXIII). The floor was waterproofed with brick and limestone slabs

Fig. 3 Cross-section of pedestal lavatory above a ring-drain, Tell Asmar, Room D 17:21, drawn by Seton Lloyd (from Lloyd Reference Lloyd, Delougaz, Hill and Lloyd1967: pl. 41b “house contemporary with the Earlier Northern Palace”). The floor was waterproofed with bitumen

The drainage installations studied by Hemker can be contextualised by Maria Krafeld-Daugherty's study of ancient Near Eastern dwelling houses and room usage, Wohnen im Alten Orient (Reference Krafeld-Daugherty1994). Her chapter on “Toiletten und Waschplätze” (pp. 94–124) concludes that lavatories are rare in the archaeological record. Isolated Old Babylonian examples have been excavated at Tello, Kiš, Mari and Tell ed-Der (she ignores the first millennium). Only at Tell Asmar (Ešnunna) in the Akkadian period and at Ur in the Isin-Larsa period were lavatories more plentiful. They fell into two types: the hole in the floor (“Abtritt”) and the pedestal or sit-upon type (“Sitztoilette”). Both types were drained, she maintains, less often by a cesspit (“Senkgrube”) than by a more complex drainage system or sewer (“übergeordnetes Kanalsystem”). The latter technology presupposed the use of rinse-water to carry solids through the system. Bathroom floors had to be waterproofed in baked brick, an expense that was affordable by few.

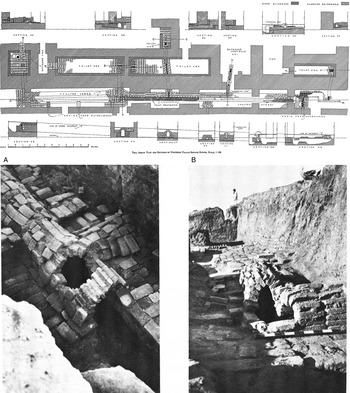

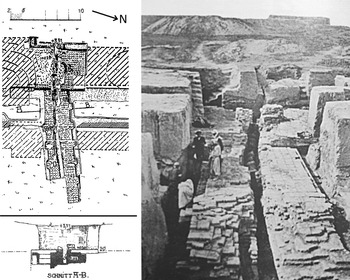

As Krafeld-Daugherty demonstrates, Tell Asmar affords an excellent case-study in third-millennium sewage disposal. It is well known that the Akkadian-period Northern Palace was provided with installations that most interpret as lavatories. Some drained directly into seepage-pits, while others discharged through underfloor drains into a covered sewer that ran under the adjacent street (Lloyd Reference Lloyd, Delougaz, Hill and Lloyd1967: 188, pls. 37, 40, 76D, 78A–B; Fig. 4). If these were lavatories, then, as observed by Ernst Heinrich, they must have been flushed by water.Footnote 4 As we shall see, in the documentary record water occurs in connection with lavatories as musâtu “rinse-water”.

Fig. 4 Plan and sections (top) and photographs (bottom) of sewer sytem, Tell Asmar, Akkadian-period Northern Palace (from Lloyd Reference Lloyd, Delougaz, Hill and Lloyd1967: pls. 40, 78A–B)

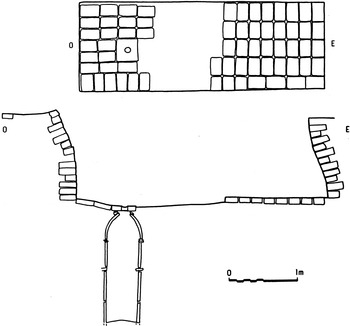

Ruth Mayer-Opificius's article on the roughly contemporaneous Arch House at Tell Asmar briefly discusses the evidence for latrines in private dwelling houses at the site (Reference Mayer-Opificius1979: 51–54; further Krafeld-Daugherty Reference Krafeld-Daugherty1994: 106–08). Slotted brick pedestals, surmounting drains, were found in some houses; they can only be sit-upon lavatories. A fine example occurs in Stratum IVa, House XXXII Room 4 (Fig. 5). It was drained by a vertical seepage-pit, no doubt a ring-drain (Hill Reference Hill, Delougaz, Hill and Lloyd1967: 151). An example of a pedestal lavatory in the Ur III rebuilding of the Arch House demonstrates the continued use of this rare technology at the end of the third millennium (Krafeld-Daugherty Reference Krafeld-Daugherty1994: 108).

Fig. 5 Remains of pedestal lavatory and paved floor in an Akkadian-period dwelling house, Tell Asmar, Stratum IVa, House XXXII Room J 18:4 (from Hill Reference Hill, Delougaz, Hill and Lloyd1967: pl. 70C; Mayer-Opificius Reference Mayer-Opificius1979: 55 Abb. 4)

The situation two hundred years later is revealed by the early second-millennium private dwellings excavated by Leonard Woolley at Ur. Ring-drains were a prominent feature in the excavations (Fig. 6). Some of the grand Old Babylonian houses at Ur were equipped with more than one such drain (Fig. 7). No. 1 Boundary Street is an apparently typical house belonging to a well-off family. It had a bathroom with a ring-drain for waste water. There was also a ring-drain in the courtyard. Not only did this drain prevent the flooding of the courtyard in a downpour, but also it could serve to receive waste water from the kitchen and night soil from chamber pots. Under the stairs was a small chamber that was equipped with the building's third ring-drain. This closet must have been a lavatory. No. 4 Paternoster Row was even better provided: it had similar provision, but with the addition of a fourth ring-drain in the kitchen. Similar facilities were found in the large houses of about the same date excavated in 1987–89 by Jean-Louis Huot at Larsa. The bathroom of House B 59 was equipped with a ring-drain surmounted by a pierced slab laid in a floor of baked brick (Fig. 8).

Fig. 6 Leonard and Katharine Woolley at Ur, with ring-drains in situ (photograph BM-Ur-GN-1592 reproduced by permission of the Trustees of the British Museum). Clearly visible, between the wall of the left-most drain shaft and the ring-drain itself, is the usual packing with potsherds to improve drainage

Fig. 7 Plans of early Old Babylonian houses at Ur, (left) No. 1 Boundary St and (right) No. 4 Paternoster Row, showing locations of ring-drains (adapted from Miglus Reference Miglus and Veenhof1996: 212)

Fig. 8 Floor-plan (top) and cross-section (bottom) of an Old Babylonian bathroom, Larsa, House B 59 Room 21, drawn by J. Suire (after Calvet Reference Calvet and Veenhof1996: 204)

Woolley describes the ring-drain technology of Ur in detail and takes it as self-evident that ring-drains were soak-aways for sewage, i.e. cesspits (Woolley and Mallowan Reference Woolley, Mallowan and Mitchell1976: 22–23):

A circular shaft a metre or so in diameter was dug to a depth of perhaps 10 m . . . , and in this was built up a vertical column of terracotta pipes . . . The rims are widened out as collars to give greater stability . . . and in the sides are small round holes to allow of the escape of moisture . . . The drains are really seepage-pits; any moisture poured down them would run off into the subsoil; the solid sewage would remain and in course of time would fill the pit, when it would be dug out and remade. The same system prevails in innumerable Eastern towns today and is far less injurious to health than might be anticipated.

Woolley's analysis was substantiated by what he found at the bottom of some ring-drains at Ur. He reports of the many examples he excavated in Area EH (which dated from the “Neo-Babylonian to the Plano-convex period”): “occasionally the base of one would be filled with and surrounded by the greenish clayey matter which results from the decay of sewage” (Woolley Reference Woolley1955: 41).

In a study of the social typology of the Ur housing, Paolo Brusasco writes of lavatories (Reference Brusasco1999–2000: 86):

These are normally small and narrow chambers, paved with bricks, and with a regular latrine opening set up towards the far end of the room. Here there is a sort of dais on which lays a drain surrounded by a raised brick stance. The drain itself consists of a slit widening to a circle (Woolley and Mallowan Reference Woolley, Mallowan and Mitchell1976: 25). Such an installation is thus very similar to those that can be seen in the latrines of any Arab town house of today . . . One may note that only 6.2% of the buildings excavated in the neighbourhoods under excavation are provided with such facilities.

What he describes is a refined variety of the hole-in-the-floor lavatory. Simpler holes in the floor, like that in House B 59 Room 21 at Larsa (Fig. 8), would have been more difficult to use cleanly as a lavatory. They may have been fitted with a superstructure made of perishable materials such as reed and clay. Pedestal lavatories of brick are notably absent in the Old Babylonian mansions of Ur and Larsa.

Brusasco uses the rareness of lavatories in the houses at Ur to speculate that “small unroofed latrines at the city's periphery [were] routinely shared by those households who lack[ed] sanitary services. Others may well [have] use[d] nearby orchards or gardens”. As we shall see, in the documentary record there is some suggestion of communal lavatories at city gates.

Krafeld-Daugherty's study of room usage in ancient Mesopotamian houses draws attention to the typical location of lavatories in small closets, especially under the stairs, as at Ur and Tell ed-Der in the early second millennium (Krafeld-Daugherty Reference Krafeld-Daugherty1994: 111). In his review of her book, J. N. Postgate notes that the same preference has been observed much earlier, at Abu Salabikh and perhaps Larsa (Postgate Reference Postgate2000: 251). Postgate also stresses that different arrangements must have obtained in non-urban settings:

The occurrence of latrines is one area where the difference between urban and rural settlements is likely to be very marked; the urban examples were sometimes constructed directly above (or in Old Babylonian times channeled into) vertical shafts made of superimposed ceramic cylinders (pierced at intervals and packed round with sherds to assist drainage), and since the tops of these shafts are rarely preserved, I suspect that they were much commoner as urban sewers than [Krafeld-Daugherty] allows.

Good examples of first-millennium waste-water disposal were found in Babylon, especially in the ruin-mound Merkes excavated by Robert Koldewey's assistant, Oskar Reuther, in 1907–12 (Reuther Reference Reuther1926). House XII had a bathroom with a sloping floor that drained into a ring-drain. House II had at least three ring-drains: one, of uncertain function, in Room 19; another in Room 12, the bathroom; and a third in Room 13, a tiny closet which could only be reached through the bathroom. In this closet was a kind of pedestal made of baked brick, which was certainly a sit-upon lavatory (Hemker Reference Hemker1993: 147; here Fig. 9).Footnote 5 The ring-drain beneath it functioned as a cesspit.

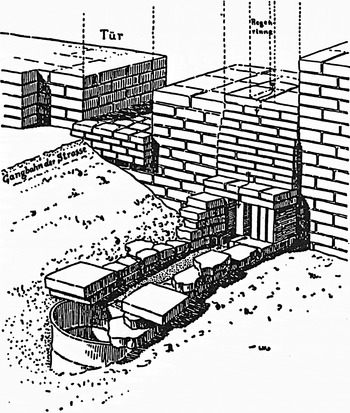

Fig. 9 Dissected drawing of a Neo-Babylonian pedestal lavatory and floor, waterproofed with bitumen, Babylon-Merkes, House II Room 13, drawn by Oskar Reuther (from Hemker Reference Hemker1993: Abb. 501)

The preceding paragraphs (which present only a selection of the evidence) have focused on lavatories serviced by ring-drains constructed directly underneath, but Krafeld-Daugherty is right to observe that many lavatories drained into remote installations through underground sewers. The under-street drain that removed waste from the Akkadian-period Northern Palace at Tell Asmar has already been mentioned. The identity of an installation in the Arch House (House II Room 44, Stratum IVb) that discharged via a drain through the exterior wall is contested (Mayer-Opificius Reference Mayer-Opificius1979: 52). Some assert that the drain emptied on to a street, an unsatisfactory location for the disposal of sewage, but the excavator identified the structure as the “remnants of a toilet” (Hill Reference Hill, Delougaz, Hill and Lloyd1967: 161) and reported that its drain led to an “unused open space” (ibid. pp. 150–51; pl. 67B). In any event, the lavatory and its drain did not survive the house's remodelling in Stratum IVa and were perhaps a failed experiment (Mayer-Opificius Reference Mayer-Opificius1979: 53; Krafeld-Daugherty Reference Krafeld-Daugherty1994: 107). Later lavatories in the same house were also associated with baked-brick drains that ran under floors and walls (Hill Reference Hill, Delougaz, Hill and Lloyd1967: 164, pl. 70A).

Ring-drains in first-millennium Babylon could also be used in combination with indirect drainage systems. In House IV in Merkes a ring-drain collected waste water from two different rooms, using short lengths of tapered clay piping fitted together to make long underfloor drains (Hemker Reference Hemker1993: 148; here Fig. 10). Such tubular drains were undoubtedly what are known in Akkadian as nanṣabu, which were good for removing waste water but too narrow to have functioned well as sewers. Underfloor drains of larger capacity could be constructed from baked brick. One was found at Babylon to take waste water out of a house and into a ring-drain situated under the adjacent street (Hemker Reference Hemker1993: 69–70; here Fig. 11).

Fig. 10 Underfloor tubular drains leading to a ring-drain within the house, Babylon-Merkes, House IV, drawn by Oskar Reuther (from Hemker Reference Hemker1993: Abb. 502)

Fig. 11 Baked-brick subterranean drain leading from a house to a ring-drain beneath the street, Babylon-Merkes, House I, drawn by Oskar Reuther (from Hemker Reference Hemker1993: Abb. 265)

The archaeological evidence very clearly shows that ancient Mesopotamian dwelling houses could be equipped with lavatories. These varied from the hole-in-the-floor type to the pedestal type. They sometimes drained directly into their own seepage-pits, but otherwise discharged via underfloor channels into pits in adjacent spaces. The technology, however, was expensive and, even in the late periods, only a minority could afford housing fitted with such a luxury. What, then, of the Assyriological evidence?

Lavatories in cuneiform texts

Quite recently Ariel Bagg published an article with the promising title “Ancient Mesopotamian sewage systems according to cuneiform sources” (Reference Bagg and Wiplinger2006). The article contains a useful survey of the archaeological evidence collected by Hemker for drainage installations, both horizontal and vertical, including the Sickerschacht, which Bagg identifies as a “cesspit”. The promise of the article's title is not fulfilled, however, for Bagg can only cite passages from cuneiform texts mentioning “pipes, gutters and water outlets related to drainage”, including the nan ṣabu. He wonders, as have others, whether ḫabannatu in the mythological narrative poem Ištar's Descent (l. 105) is a sewer pipe, but does not explore further the Sumerian and Akkadian terminology for lavatories and their drains.

The disturbing fantasy that I indulged in earlier, of Babylonian ladies taken short in the night, was an error, of course, because, as Baker noted, those who could not afford houses with lavatories could no doubt make use of what she delicately called “portable containers”. Only if such a thing was not to hand would anyone face an inconvenient nocturnal trip to garden, date-grove or field. For the rest, at the end of the bed there certainly lay a chamber pot.

We know the Babylonian chamber pot well: in Sumerian it was dug-kisi and in Akkadian karpat šināti. Both expressions mean literally “piss-pot”. The terminology is set out in a lexical text that lists different varieties of pot (1):

Probably chamber pots are well attested in the archaeological record, but it is not necessarily easy to distinguish between the sherds of a chamber pot and fragments of other vessels. Possibly the museums of the world hold a selection of Babylonian chamber pots, but that is another research topic. Here I would ask different questions: where did a Babylonian empty his (or her) chamber pot? And where in a Babylonian house might one actually find the residents' waste products? The Standard Babylonian terrestrial-omen series Šumma ālu gives a clue, in an omen where the common denominator between observation and prediction is a mouth doing dirty work (2):

diš kimin min -ma (= šaḫû ana bīt amēli īrubma) zê(šè) amēli(na) : ze-e il-mu-um bītu(é) šū(bi) iltêt(1) šanat(mu) mu-lam-min p[î(ka) irašši]

Šumma ālu XLV 45, from CT 38 47: 45

¶ (If) a pig enters a man's house and consumes faeces (var. the man's faeces): that household [will be the subject of] malicious gossip for one whole year.

Such a thing might well occur when someone had forgotten to empty his chamber pot and left it uncovered in the courtyard. Not all human excrement was eaten by pigs, however. Two passages of text show that the body's waste products could sink into the earth or merge with river water. A Standard Babylonian text intended to dispel evil forces reads thus (3):

mim-ma lem-nu mim-ma là ṭābu(dùg-ga) šá ina zu[mur(su) annanna(nenni)] mār(a) annanna(nenni) bašû(gál) ú itti(ki) mê(a)meš šá zu-um-ri-šú u mu-sa-a-ti šá qātī(šu)min -šú liš-šá-ḫi-iṭ-ma nāru(íd) a-na šap-lu-šá lit-bal

lipšur-litany, ed. Reiner Reference Reiner1956: 138 ll. 101–03

May anything evil and unwholesome that remains in the [body of So-and-So,] son of So-and-So, be sloughed off with the water of his body and the rinse-water of his hands, and may the river take it away into its depths!

A similar idea is expressed in a line of the incantation series Šurpu, a Standard Babylonian text to counter the negative consequences of violation of oaths (4):

it-ti mê(a)meš šá zumri(su)-ka u mu-sa-a-ti šá qātī(šu)min -k[a] liš-šá-ḫi-iṭ-ma erṣetu(ki) tum lit-bal

Šurpu VIII 89–90, ed. Reiner Reference Reiner1958: 44

May (the oath) be sloughed off with the water of your body and the rinse-water of your hands, and may the earth take it away!

It is perhaps unnecessary to explain that the “water of your body” is the water with which the exorcist's client cleaned his backside. As in a modern Middle Eastern lavatory in traditional style, lavatory paper was not available. The practice was to wash the backside with the left hand and then to rinse the hand itself. In Akkadian the water used to rinse the hands was called musâtu. This word otherwise occurs in the expression bīt musâti “house of rinse-water”, self-evidently a room or building in which one could dispose of dirty water. The bīt musâti has long been identified as the Babylonian word for “lavatory”, already by Bezold in his glossary of Akkadian (Reference Bezold1926: 178a) and lately by all the modern dictionaries, s.v. (AHw 677, CAD M/2 234, CDA 219). But it will be useful to review the other evidence for this identification.

The bīt musâti and the demon Šulak

Several post-Old Babylonian texts report that the bīt musâti was the favourite haunt of a demon called Šulak. Hemerologies prescribed correct behaviour on the sixth and seventh days of the seventh month, Tašrītu, as follows (5):

ana bīt(é) mu-sa-a-ti là irrub(ku4)( ub ) d šu-lak imaḫḫaṣ(sìg)-su

Livingstone Reference Livingstone2013: 170 l. 76, 185–87 iii 10–11, 27

One should not visit a bīt musâti, lest Šulak strike one.

An Old Babylonian hemerology from Tell Haddad that lists behaviour to be avoided on an unidentified day contains an ancestor of this proscription in syllabic Sumerian and an Akkadian translation. The bīt musâti is replaced by a less euphemistic term compounded with šè = šittum “fart” (6):Footnote 7

˹e˺-še-ka nam-mu-un-ku-re ša-ni-in-˹tu˺-mu i-gá-al

a-na bīt(é) ši-ti-im ú-ul i-ru-ub li-bu it-ta-na-an-pa-ḫu

Cavigneaux and Al-Rawi Reference Cavigneaux and Al-Rawi1993: 102–03 ll. 16–17

One will not enter a fart-house, lest one get wind (Sum.) // lest (one's) insides keep getting pumped up with air (Akk.).

The connection between proscribed act and consequence is one of cause and effect, with wind as the common denominator. The demon Šulak, who replaces wind in the later version of the proscription, is well attested (Krebernik Reference Krebernik2012). According to another hemerological passage he also lurked in date-groves (Livingstone Reference Livingstone2013: 185 iii 3–4), and the list of demons associates him with deserted settlements: d šu-lak ina ḫur-bat (Livingstone Reference Livingstone1986: 186). No doubt both these places were used for defecation al fresco and so offered Šulak the same opportunities as a bīt musâti.

Šulak was a lion-demon but stood upright like a man: a Neo-Assyrian composition which reports a dream of hell by an Assyrian prince, the so-called Underworld Vision of Kummâ, describes him thus (7):

d šu-lak nēšu(ur-maḫ) ka-a-a-ma-ni-ú ina muḫḫi(ugu) šēpē(gìr)min -šú ár-ka-a-ti ú-šu-[uz]

SAA III 32 rev. 6, ed. Livingstone Reference Livingstone1989: 72

Šulak is a normal lion standing on its hind legs.

The Babylonians and Assyrians believed that Šulak was responsible for dangerous diseases, and the expressions qāt Šulak “hand of Š.” and Šulak i ṣṣabassu “Š. has possessed him” occur in several Standard Babylonian diagnostic-omen apodoses (references in Heeßel Reference Heeßel2000: 304 n. 6). One such instance occurs at the end of a section on stroke (mišittu), and sets out symptoms that a healer might encounter when visiting a victim (8):

diš šumēl(gùb)-šú tab-kát qāt(šu) d šu-lak

diš šumēl(gùb) pagri(ad6(lú.bad))-šú ka-lu-šú-ma tab-kát miḫra(gaba-ri) maḫiṣ(sìg) iṣ qāt(šu) d šu-lak rābiṣ(maškim) mu-sa-a-ti āšipu(maš-maš) ana balāṭi(tin)-šú (or bulluṭi-šú) qibâ(me) a úl išakkan(gar) an

Sakikkū XXVII 11–13 // AMT 77 no. 1: 8–10; cf. Stol Reference Stol1993: 76, Heeßel Reference Heeßel2000: 297

¶ (If) the (patient's) left side hangs limp: (that means) the “Hand of Šulak”.

¶ (If) the whole left side of his body hangs limp: he is stricken at the front(?). “Hand of Šulak”, Lurker in the (bīt) musâti. An exorcist cannot make a prognosis for his recovery (or diagnosis for his cure).

An older version is known from fragments found at Boğazköy (Stol Reference Stol1993: 76). At first sight the recommendation in the first-millennium text not to treat the patient is no surprise, for the prognosis for a stroke victim in ancient Mesopotamia must have been very poor.Footnote 8 However, the immediately preceding lines (Sakikkū XXVII 9–10 // AMT 77 no. 1: 6–7) set out the exact same pair of symptoms as (8), but on the right: the diagnosis of both is mišitti rābiṣi “stroke by the Lurker”, i.e. Šulak, but the prognosis of the first is positive.Footnote 9 The prognosis, for good or bad, was thus determined by the right–left (positive–negative) dichotomy prevalent in divinatory theory as much as by the symptoms themselves.

The connection of stroke with the lavatory demon Šulak in Babylonia probably resided in a common human anxiety, that straining too hard “at stool” is injurious to health and can provoke the onset of stroke and other neurological problems. The sudden death of King George II of England on his commode chair on 25 October 1760 has been attributed to such a cause.

At least two published incantations are targeted at Šulak. In the first, known from two Late Babylonian copies, Šulak occurs among a horde of miscellaneous malign forces and has the particular epithet ša mu-un-ze-e-ti (CT 51 142: 14 // CBS 11304: 14, Ellis Reference Ellis1979: 218). This is probably a variant of the expression ša musâti “the one from the (house of) rinse-water”, but contaminated with the root √nzʾ (nezû “to urinate”). The second incantation is published by Irving Finkel as No. 37 in a Late Babylonian archive of medical tablets. In it Šulak is addressed as “the one who struck the young man and took away his life” (9. Finkel Reference Finkel, George and Finkel2000: 194 l. 1: ma-ḫi-[ṣu eṭ-lu le-qu-ú] napišti(zi)-šu). It and two other spells against Šulak (ibid. p. 194 n. 44) were recited during exorcistic fumigation rituals for victims of stroke (mišittu). Šulak's lethal touch arises from this association with stroke, already encountered in passage (8).

Another disease that was linked with Šulak was šimmatu, as in a medical text from Late Babylonian Uruk (10):

DIŠ amēlu(na) īnā(igi)meš -šú kišād(gú)-su u šapat(nundum)-su šim-mat irtanaššâ(tuk)meš-a ù ki-ma išāti(izi) i-ḫa-am-ma-ṭa-šú amēlu(na) šū(bi) rābiṣ(maškim) mu-sa-a-ti iṣbat(dab)-su Footnote 10

Uruk I 46: 6–8, ed. Hunger Reference Hunger1976: 56

When a man's eyes, neck and lips keep getting šimmatu and scorch him like fire, that man has been possessed by the Lurker in the (bīt) musâti.

The remedy is salving with a special preparation of oil three times daily. As an additional measure the patient must wear around the neck a leather pouch, probably containing some of the same magic salve. The next remedy is for paralysis (mišittu) of the face, reinforcing the connection between Šulak and stroke. More important for our purpose is a second tablet from Uruk, which contains a commentary on passage (10). The commentary explains the diagnosis (11):

rābiṣ(maškim) mu-sa-a-ti : d šu-lak / a-na bīt(é) mu-sa-a-tú là irrub(ku4) ub : d šu-lak imaḫḫaṣ(sìg)-su / d šu-lak šá iqbû(e) ú : šu : qa-tum : la : la-a : kù : el-lu / ana bīt(é) mu-sa-a-tú ku4 ub qātā(šu)min -šú úl ellā(kù) ana muḫḫi(ugu) qa-bi

Uruk I 47: 2–5, ed. Hunger Reference Hunger1976: 57

The Lurker in the (bīt) musâti (means) Šulak. (Compare the passage) “One should not visit a bīt musâti, lest Šulak strike one”. According to the oral instruction of the teacher (lit. as he said), Šulak (is to be understood thus): šu means “hand”, la means “not”, kù means “pure”. (The passage) ana bīt musâti irrub (or īrub) qātāšu ul ellā was cited in connection.

The first task of this passage of commentary is to identify the rābi ṣ musâti as Šulak. We have already encountered this epithet alongside his name in the diagnostic-omen passage (8); name and epithet also occur together in an unpublished incantation prayer (K 6928+Sm 1896 obv. 19′–20′; Lambert Folio 1189). The commentary continues by quoting the warning given in the hemerology passages (5), that to visit a bīt musâti risks falling prey to Šulak. It then quotes from a source that has not yet been identified; ana bīt musâti irrub/īrub qātāšu ul ellā means “he visits (or visited) the bīt musâti, (so) his hands are impure”. Probably the context of this statement was cultic, for qātā ellētu “a pair of pure hands” was a fundamental requirement of all who held temple offices, as exemplified by the case of the mythical Adapa, who in his capacity as archetypal servant of the gods (“priest”) bore the epithet ella-qātī “Pure-Hands” (Adapa A 1′–14′, ed. Izre'el Reference Izre'el2001: 92). Guidance must certainly have existed as to how to achieve clean hands and what activities (like visiting the bīt musâti) might have the opposite effect.

Whatever its original context, the quotation is deployed here in order to demonstrate a logical connection between Šulak, etymologized as “Dirty-Hands” in an oral tradition also quoted by the commentary, and his customary haunt, the bīt musâti. In short, the commentator asserts that Šulak's dirty hands can be attributed to his propensity for lurking therein. With it comes certain confirmation that the bīt musâti was not a bathroom in the sense of a place to wash in. In a bathroom hands do not become dirty, they become clean. This place that you leave with dirty hands is, as the dictionaries assert, but here more crudely put, the Babylonian shithouse. As in many languages, the expression widely employed for this place is a polite euphemism: bīt musâti “house of rinse-water”, deriving from mesû “to wash, rinse”, can be compared with, inter alia, British “lavatory”, American “washroom” and “bathroom”, and Japanese otearai “hand washing”.

Once we are sure that bīt musâti was a lavatory, then it is no surprise that it was the haunt of a demon whose hands were always dirty. Squatting in the dark in a Near Eastern lavatory is seldom a pleasant experience, even for those who are not in fear of a lion-demon springing out of the depths of a filthy pit to bite their bare behind and take their life.Footnote 11 The diagnostic texts hold that this unsavoury character could attack the human body by striking it, but could also enter and possess its victim. Presumably it did this by taking advantage of people at their most vulnerable, while squatting to defecate ano aperto.

Later cultures of the Near East and Europe perpetuated this ancient anxiety of a demon in the lavatory (Stol Reference Stol1993: 76). Joann Scurlock even proposes to find a far-eastern “equivalent (with sex change) for the Mesopotamian Šulak, rābiṣu of the lavatory, in the Korean ‘toilet maiden’” (Reference Scurlock2003: 106). The similarity lies only in place of residence, however, for in Korea the Toilet Maiden's function is protective, “guarding against the predations of evil spirits” (Grayson Reference Grayson2002: 224). Her role finds a closer parallel in the benign demon enlisted to oppose Šulak, who now makes his entrance.

Unsurprisingly the Babylonians sought, by magic means, to drive Šulak and other demons out of the lavatory, and prevent their return. Among the various apotropaic figurines that could be buried in the foundations of a house, in order to keep wicked and evil powers outside, were lion centaurs. A passage of a Standard Babylonian prescriptive text describes how this benign monster could be enlisted to guard the lavatory (12):

ṣalmī(nu)meš ur-maḫ-lú-u18-lu ṭīdi(im) ina idi(á)-šú-nu ta-par-ri-ik mukīl-rēš-lemutti(sag-ḫul-ḫa-za) tašaṭṭar(sar) ár ina bāb(ká) mu-sa-a-te imna(15) u šumēla(150) te-te-mer

KAR 298 rev. ii 15–16, ed. Gurney Reference Gurney1935: 72

Clay figurines of Lion Centaurs: you write on their sides: “You shall bar the way of the Upholder-of-Evil”. You bury them at the doorway of the lavatory, left and right.

Here the expression Upholder-of-Evil probably covers any malignant magic power. But, as has been noted before (e.g. Wiggermann Reference Wiggermann1992: 98), a pictorial record survives of the mythical battle between the forces of good and evil that took place daily in the Babylonian lavatory. A Middle Assyrian cylinder-seal now in Berlin depicts a Lion Centaur and a rampant lion fighting (Fig. 12). Passage (8) has described Šulak as a rampant lion, so the scene on the seal is ur-maḫ-lú-u18-lu and Šulak in mid-struggle.Footnote 12

Fig. 12 Middle Assyrian cylinder-seal depicting a Lion Centaur and the demon Šulak in combat: (top) photograph of modern impression (from Moortgat Reference Moortgat1942: 67 Abb. 30); (bottom) drawing by Tessa Rickards (from Black and Green Reference Black and Green1992: 119). Vorderasiatisches Museum, VA 2667

The asurrû

One last passage of Babylonian exorcistic literature that mentions a bīt musâti brings us finally to the keyword asurrû. The passage comes from the Standard Babylonian incantation and ritual series Maqlû, and thus from a context of sorcery and black magic. In order to undo the magic that binds his client, the exorcist asserts his power to counter a witch's spells by declaring how he will dispose of them. Just one of the many such methods of disposal is (13):

ki-ma mê(a)meš mu-sa-a-ti a-sur-ra-a ú-ma-al-la-šú-nu-ti

Maqlû II 178, ed. Meier Reference Meier1937: 19

I shall fill the asurrû with them (her spells) like water from the lavatory.

According to this and parallel passages of the same series (II 167, VIII 80, ed. Meier Reference Meier1966: 80), the asurrû was a place where one could dispose of waste water from the lavatory. Thus one might propose that an asurrû should be a type of sewer, or part of a sewer. The evidence for this word will be examined next.

The word asurrû is well attested. The dictionaries' position (set out in the introduction), that asurrû is part of a wall, was long ago taken by Baumgartner in his study of architectural terms in Akkadian (Reference Baumgartner1925: 253) and soon thereafter reiterated by Ungnad in his glossary of Neo-Babylonian legal documents (Reference Ungnad1937: 32). Modern lexicographers usually defer to their ancient counterparts and base their understanding on entries in Sumero-Akkadian lexical lists and glossaries. This is what has happened in the case of the Akkadian word asurrû. Three bilingual lexical lists and a handbook of Sumerian legalese make a connection between asurrû and Sumerian úr, which means “root”, “base” or similar, while two versions of a monolingual synonym list equate it with išdu “base”, which is the normal Akkadian counterpart of úr:

Entry (14), in an exhaustive glossary of Sumerian organised by cuneiform signs, asserts that asurrû is only one of many Akkadian equivalences of a Sumerian word written with the sign úr and pronounced ur. The entries in the group vocabularies Nabnītu and Antagal should not be considered in isolation, for these texts were organised by groups of Akkadian words that were associated in some way. Passage (15) of Nabnītu is the second entry in a section on the verb sêru “to plaster”; the neighbouring lines cite ūru “roof” and igaru “wall”, from which we learn only that asurrû must also have been part of a built structure. In entry (16) from Antagal, asurrû is grouped with takkapu “peephole”, išdī bīti “base of house” and indu asurrê “support of a.” (below, 57). This group reinforces the association of asurrû with išdu “base” but also raises the comparison with a new idea, takkapu, to which I shall return later.

The bilingual passage (17) was translated by Benno Landsberger as “den Keller wird er ausbessern” (Reference Landsberger1937: 65), although Babylonian houses did not have cellars. It is from an academic manual of terms in legal documents, specifically from a passage on phrases that could theoretically be used in house-rental contracts. There it occurs among other expressions stipulating that a tenant should maintain a house's roof, ceiling beams and walls for as long as he occupies it. The Sumerian version of clause (17) seems to have had currency only in the academic legal tradition. However, the Akkadian expression asurrâ kašāru also occurs in a set of curses in a building inscription of Kudurmabug, excoriating the person “who does not repair its a.” (20. RIM E4.2.13a.2: 29–30, ed. Frayne Reference Frayne1990: 268: ša … a-sú-ur-ra-šu la i-ka-aš-ša-ru). Yaḫdun-Līm's building inscription from the temple of Šamaš at Mari similarly curses any future person “who does not keep its asurrû strong” (21. RIM E4.6.8.2: 122, ed. Frayne Reference Frayne1990: 607: ša … a-su-ra-šu la ù-da-na-nu). These Old Babylonian curses draw on the academic language of house-rental contracts.

Synonymous phrases occur in real legal documents setting out terms for renting houses (Oppenheim Reference Oppenheim1936: 70–80). In the Old Babylonian period the key contractual phrases are (22) ūram isêr asurrâm udannan “he (the tenant) shall plaster the roof and keep the a. strong”. Neo- and Late Babylonian contracts have instead two synonymous phrases, (23) ūru išanni, batqu ša asurrê iṣabbat (often transposed) “he (the tenant) shall plaster the roof and keep the a. in good repair”. These stipulations show that the maintenance of the asurrû was an important contractual obligation of tenants. Old Babylonian house-rental contracts rarely include the phrases, and most instances are post-Samsuiluna;Footnote 13 Neo- and Late Babylonian contracts usually include them.Footnote 14

Nothing so far suggests that the dictionaries' definitions of asurrû are inadequate. One might baulk at CAD's “damp course” (A 350, repeated in S 228, Š/1 237, 408, Š/3 324, T 466 etc.) on the grounds that Babylonian houses did not ordinarily have damp courses.Footnote 15 When it was necessary to seal brickwork against rising damp, such work was referred to in terms of laying baked bricks (agurru) in bitumen mortar (kupru). But the evidence presented so far unequivocally suggests that an asurrû was an important part of a building's structure, as the dictionaries assert.

Other evidence will be less easy to reconcile with the dictionaries' definitions. It falls into three parts. First of all, an asurrû could be wet. The passage of Maqlû in which an asurrû receives waste water from the lavatory has already been quoted (13). The second key datum in this regard is the lexical entry (24) A I/2 151: pu-upú = a-sur-rum. Sumerian pú means “well”, “cistern”, “pool”, and asurrû is the fourth Akkadian equivalence in A I/2, following būrtu “well”, šitpu “excavation” and issû “clay-pit”. The common ideas in these words are pit and water; they are inextricably linked because holes in the ground in Babylonia quickly fill with groundwater. The equation pú = asurrû (available since 1901) must have been what led Carl Bezold in his glossary of Akkadian to go beyond Baumgartner's position with his third (and tentative) definition of asurrû (Bezold Reference Bezold1926: 53): “Wände; (einschließendes) Mauerwerk; Zisterne (?)”.

Second, an asurrû could provide snakes, mongooses and vermin with a habitat. The following two passages are entries in the great Standard Babylonian series of terrestrial omens. The first places the asurrû in a private dwelling (25):

DIŠ ṣēru(muš) ina a-sur-re-e bīt(é) amēli(na) ú-lid …

DIŠ ṣēru(muš) ina a-sur-re-e bīt(é) amēli(na) irbiṣ(ná) iṣ …

DIŠ ṣēra(muš) sinništu(munus) ina a-sur-re-e ina la mu-de-e iṣbat(dab)-su-ma umaššir(bar)-šú …

Šumma ālu XXIII 102–4, cf. Freedman Reference Freedman2006a: 46

¶ (If) a snake gives birth in the a. of a man's house: … (negative apodosis)

¶ (If) a snake nests in the a. of a man's house: … (negative apodosis)

¶ (If) a woman catches a snake unawares in the a. and lets it go:Footnote 16 … (positive apodosis)

The second locates it in the gate of a town wall (26):

[DIŠ dnin-ki]lim ina a-su-re-e abulli([ká]-gal) ūlid(ù-tu) …

Šumma ālu XXXIV 1, ed. Freedman Reference Freedman2006a: 224

[¶ (If) a] mongoose gives birth in an a. at the city-gate: … (negative apodosis)

Another passage that associates snake and asurrû occurs in a Standard Babylonian incantation against fever, in a line that commands the demonic force behind the fever to depart the sufferer's body (27):

ṣi-i ki-ma ṣēri(muš) ina a-sur-re-ki ki-ma iṣṣūr-ḫurri(bur5-ḫabrud-da)mušen ina nar-ba-ṣi-ki

Lambert Reference Lambert1970: 40 l. 11

Go out, like a snake from your a., like a hole-(nesting) bird from your nest!”

The asurrû of these passages was not solid, like a wall, but hollow, affording a refuge for creatures whose normal habitat was a hole in the earth or a cavity in a building. Other creatures lived there too. In an Old Babylonian letter from Mari, the writer abases himself before the king by referring to himself deprecatingly as a “worm/maggot/leech from the a.” (28. Veenhof Reference Veenhof1989: tu-il-ta-am ša li-ib-bi a-su-re-em).Footnote 17 Two related Old Babylonian spells say of the scorpion that “the a. gave birth to it” (29. George Reference George2010b: ú-ul-da-šu-ma a-sú-ru-um // ul-da-aš-šu a-su-ru-um).

A third body of evidence shows that an asurrû could stink. This is clear from several passages, especially the following Old Babylonian spell, known in two versions (30–31):

[ṣi]-it er-ṣe-tim ṭà-ab

[ṣ]i-it a-sú-re-em na-pi-ša-am i-šu

it-ta-ṣi-a-ku-um tu-ú ša a-wi-lu-tim du-up-pi-ir

YOS XI 16: 1–3

[ṣi-it er]-ṣe-tim ṭa-ab

[ṣi-i]t ˹a˺-sú-re-x-pi(sup. ras.)-ša-am

[i]-šu-ú

[a]t-ta-di-ku ta-a ša a-wi-lú-ti

du-up-pi-ir

tu-ú en-nu-ri

YOS XI 77: 10–15

That which comes out of the earth is pleasant, that which comes out of an a. has a stench. The spell of a human being has gone forth against you (var. I have cast against you). Be gone! Tu-Ennuri spell.

The spell was probably to be uttered when encountering a snake or scorpion coming out from its hiding place in the asurrû.

The presence in the asurrû of mongooses has already been noted (26). The bilingual version of an old incantation likens other demons to mongooses, whom it supposes to be attracted by the asurrû's smell (32):

dnin-kilim-gin7 úr é-gar8-ra-ke4 ir-si-im in-na-ak-e-ne

ki-ma šik-ke-e a-sur-ra-a uṣ-ṣa-nu šu-nu

Udug-ḫul VI 175′, ed. Geller Reference Geller2007: 134

Like mongooses they sniff at the a. (Akk.) // base of the wall (Sum.).

The demons were evidently intent on entering the house unobserved and to that end were trying to locate the asurrû by its characteristic odour.

What then was an asurrû? The contexts assembled above demonstrate that it could be hollow, wet and malodorous, and confirm the proposal briefly advanced in 1999, that it was some kind of foul-water drain or sewer. Here it can be recalled that in the group vocabulary Antagal D 117–20 (16) asurrû was associated with takkapu “peephole”. If asurrû is understood as “sewer”, the idea shared by the two words emerges clearly. They were both apertures in a built structure: the takkapu was an opening in a wall's superstructure, the asurrû an opening in a building's infrastructure. Probably the association was strengthened by the tradition that both also afforded nesting places to small animals: the asurrû as documented above, the takkapu to owls (e.g. Šumma ālu II 1).

Further instances of asurrû “sewer”

The identification of asurrû as a foul-water drain or sewer, rather than a solid structure, adds nuance to several other attestations:

In the lists of omens that exemplified the academic theory of Babylonian divination, omen (protasis) was often matched with outcome (apodosis) through analogy. An Old Babylonian omen of this kind uses asurrû in juxtaposing by analogy a pierced feature on a lamb's liver with pierced defences (33):

[DIŠ da-na]-nu i-na qá-ab-li-šu pa-li-iš a-sú-ra-k[a na-ak-rum] ú-ša-ap-la-aš

Nougayrol Reference Nougayrol1941: 81 rev. 5–6, ed. Winitzer Reference Winitzer2011: 92 n. 60

[¶ (If) the] “strength” has a hole bored in its centre: [the enemy] will tunnel through your sewer.

The prediction belongs in a context of siege warfare. Here asurrû was evidently an installation that passed under the city wall. Monumental walls were obvious hindrances to good drainage of water from a town to the surrounding land, and provision had to be made to allow the passage of storm run-off and other waste water through the city wall. The excavations of the first-millennium double city wall at Babylon uncovered several water channels, of varying size, that passed through both parts of the wall and discharged into the moat; one is illustrated here (Fig. 13).Footnote 18 Such drains made a town vulnerable to siege by affording the enemy hidden opportunities for mining operations. The omen capitalizes on this anxiety. It also reminds us that, according to the incipit of Šumma ālu XXXIV (26), an asurrû was a typical feature of a city gate. Perhaps there were public latrines at some city gates which discharged effluent outside the wall.

Fig. 13 Plan (top left), cross-section (bottom left), and photograph (right), looking west, of a water channel passing under the double city wall of Babylon at Tower 14 on the wall's east stretch (from Wetzel Reference Wetzel1930, details of pls. 33, 34 and 70)

Post-Old Babylonian texts add to the picture. Among materia medica used in healing, Babylonian medical texts cite two substances compounded with asurrû. One is (34) eper asurrê “dirt from the a.” According to the Standard Babylonian pharmacological list Uruanna (II 257 and III 103), this expression was a secret name for the plant kurkānu (Köcher Reference Köcher, Boehmer, Pedde and Salje1995: 204b). It could also be used instead of abukkatu-sap (Worthington Reference Worthington2006: 37 on iii 2). “Dirt from the a.” is not unquestionably muck from a sewer (cf. Šumma ālu VI 35 at 45 below) but, as I am advised by Mark Geller, it bears comparison with Aramaic ʿprʾ mṭwlʾ dbyt hksʾ “dirt from the shadow of the toilet”. This was an ingredient in medical recipes in the time of the Babylonian Talmud (Geller Reference Geller, Kottek and Horstmanshoff2000: 23). A rarer ingredient of Babylonian medical recipes was (35) piqanni(a.gar.gar) asurrê “turdlet from the a.” (BAM 115 rev. 11, ed. Geller Reference Geller2005: 78 with n. 1), no doubt also a secret name. Such secret names fall into the category of materia medica known as “Dreckapotheke” (Geller Reference Geller2004: 27; Reference Geller2005: 7). The two pharmacological expressions compounded with asurrû reveal in passing that it contained eperu “soil, earth, dust” and faeces; the latter, at least, certainly alludes to a sewer's contents. The asurrû's evil smell was occasioned by what it contained.

An Akkadian spell, probably against stomach-ache, presents the sequence “ox in the pen, sheep in the fold, pig in the sewer” (36. STT 252: 23–25, ed. Reiner Reference Reiner1967: 192, Veldhuis Reference Veldhuis1990: 39: libbi(šà) alpi(gu4) a-na tar-ba-ṣu lìb-bi immeri(udu-níta) a-na su-pu-ru lìb-bi šaḫî(šaḫ) a-na asurrê(a-˹sur˺) e ). It thereby identifies the asurrû as a place where one would typically encounter a pig. The proverbial English vulgarism “happy as a pig in muck (var. shit)” comes to mind. If it could be occupied by a pig, the asurrû was not a drain with a closed end, such as a ring-drain, but a sewer that discharged into an open space accessible to animals. Indeed, one might imagine that Babylonian pigs were encouraged to feed at sewage outlets, in order to minimize the risk to human health that raw sewage poses.

A Standard Babylonian terrestrial-omen text, associated at Uruk with Šumma ālu, contains a section on places where a man might wash. After irrigation ditch, well and river comes ina a-˹su˺-u[r-re-e] “in a sewer” (37. Uruk II 34 obv. 37).Footnote 19 This asurrû is evidently again a drain that discharged in the open.

The Standard Babylonian incantation series known today as Marduk's Address to the Demons contains many lines on the behaviour of demons. This passage makes telling associations between entry into houses, an asurrû and garbage (38):

lu-u šá bītāti(é)meš te-te-né-er-ru-ba

lu-u šá as-kup-pa-a-ti teš-te-né-ʾ-i-ia!(tablet: ra)

lu-u šá a-sur-re-e ta-at-ta-na-al-la-ka

lu-u šá ina tub-kin-na-a-ti ta-at-ta-na-aš-šá-ba

Marduk's Address II 17–21, cf. Lambert Reference Lambert1956: 314

(May Asalluḫe get rid of you,) whether you are (demons) who keep going into houses, or who keep visiting(!) thresholds, or who come and go through sewers, or who lie in ambush in rubbish dumps …

Extrapolating from passages (36–38) in combination, one could further identify asurrû with the sort of subterranean drain that has been discovered at Tell Asmar, already noted in connection with the lavatories of the Akkadian-period Northern Palace. This very elaborate example of foul-water drainage received effluent from many installations, passed through the walls of the palace, under the street and away to a remote location (Fig. 4). Such a sewer, whether on the grand scale of this example or of more modest dimensions, would easily have been the site of the various activities, real and imaginary, associated in the texts with asurrû. Waste water from inside a building could be disposed of through it (13). Hole-nesting creatures like mongooses, snakes and scorpions might easily use it as means of entry into houses (25–27, 29). Suspicion would arise that demons could use the same route (38). A similar anxiety might attend the city wall in time of siege, lest the enemy use waste-water outlets to gain entry to the town (33). At the sewer's outflow (37), where no doubt a stinking pool might form (24, 30–32), pigs and other scavengers could feed (36), and other unlovely sights fall into view (28, 35). The association of Sumerian úr-é-gar8 “base of wall” and asurrû in the late Old Babylonian legal tradition (17), and later in Udug-ḫul VI (32) and Antagal D 118 (16), would then be more understandable, for when such a drain was constructed, it necessarily passed through the base of a wall in order to discharge somewhere outside.

A figurative sewer: asurrû in liver omens

Omen texts relating to divination by extispicy sometimes refer to part of the lamb's gall-bladder as an asurrû, written syllabically or a-sur (39).Footnote 20 R.D. Biggs' suggestion that this was “another possible term” (Reference Biggs1969: 166 n. 2) for the cystic duct, which drains bile from the gall-bladder, is strengthened by the function of its architectural analogue as a sewer or drain. The more common term for this duct was ma ṣraḫu, occasionally written in Sumerian, sur (ibid. p. 164). Abbreviation was a common feature of divinatory terminology and this sur is surely an abbreviation for a-sur-(ra).

Another asurrû (40) was situated to the right of the base of the liver's caudate lobe, ubānu, according to a Middle Babylonian omen text from Susa (MDP 57 no. 4 rev. 19–21, ed. Labat Reference Labat1974: 95) and first-millennium scholia (Šumma pān takālti IX 163, ed. Koch-Westenholz Reference Koch-Westenholz2000: 372; Koch Reference Koch2005: 504 l. 256). This must be the common hepatic duct, which forms a T-junction with the cystic and bile ducts to the left (i.e. Babylonian right) of the caudate lobe (Leiderer Reference Leiderer1990: 158 fig. 2 ductus hepaticus). Thus Babylonian hepatomancer-anatomists borrowed the word for sewer when they wanted to refer to the ducts on the lamb's liver that drained away noxious liquid.

Etymology of asurrû

Given the function of asurrû as a sewer, and its incontestable origin as a loanword from Sumerian, it is evident that the word is based on a compound of the Sumerian noun a “water”. Another nominal compound a-sur-ra is a literary term for the deep waters where fish dwell (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1998: 310–15). The Akkadian loanword in that case is asurrakku, not asurrû, which thus discounts it as unrelated. Two early versions of the lexical list Kagal present an a-sur-ra in the following passages (41a–b):

The first entry was evidently understood in antiquity as a nominal compound of water and ditch (usually sùr) and translated into Akkadian accordingly. It might belong to the technical terminology of drainage, but if this is our sewer it has been badly mistranslated. The passage is not useful here.

The Sumerian compound verb a––sur “to urinate” has been encountered already, in one of the terms for a chamber pot, dug.a-sur-ra (1). According to Miguel Civil, the verb sur “means simply ‘to perform an action from which a liquid product results’” (Civil Reference Civil, Biggs and Brinkman1964: 81). Among expressions compounded with this verb he included “a—sur ‘to urinate’”. We can now add to his evidence two other processes in which liquid is discharged from the body with force: šà––sur “to have diarrhoea (Sjöberg Reference Sjöberg1960: 160), and zé––sur “to puke bile”, i.e. vomit (George Reference George, Baker, Robson and Zólyomi2010a: 112). It is clear from this set of analogous physical processes that the literal meaning of the compound a—sur is “to squirt out water”.Footnote 21

A Late Babylonian commentary from Uruk shows that the meaning sur “to discharge (fluid)” was still known in the Persian period. The passage is an exegesis of a teratomantic omen about a deformed lamb in Šumma izbu XVII (42):

sursu-ur : ši-tin-nu : sur : ta-ba-ku šá ši-na-a-tú ina ṣa-a-tú qa-bi

Uruk II 38: 10–11, ed. von Weiher Reference von Weiher1983: 164; De Zorzi Reference De Zorzi2014: 746–48

sur = “to keep urinating” (because) sur means “to discharge, of urine”, as recorded in a commentary.

Another commentary on Šumma izbu concurs and may even have been the cited reference (Leichty Reference Leichty1970: 227 l. 531; De Zorzi Reference De Zorzi2014: 857 B.1 9): sur = ta-ba-ku “to discharge”, again of urine.

Other first-millennium texts offer instances of sur as a verb describing the motion of liquids. The lexical text Antagal is one (C 267): sur-sur = za-a-[bu] “to drip, melt”. Another is a late litany that describes a god's attack on a hostile land in terms of a cloudburst and pairs two clauses (Reisner Reference Reisner1896: 39 no. 19 rev. 7–8, ed. Cohen Reference Cohen1988: 444 l. 85): im-gin7 ba-an-da-šèg “he poured down like rain” and im-gin7 ba-an-da-sur, which must be almost synonymous, perhaps “he drenched it like rain”. The clauses' synonymity and the meaning of sur in this context are substantiated by the Akkadian translation: ki-ma ra-a-du iz!-nun ki-ma šá-mu-ti uš-tal-li (CAD Š/1 272 contra Cohen uš-pe-le) “he rained like a downpour, he showered down like rain”. The verb šalû is elsewhere used to describe spraying fluids from the mouth (spittle, blood, vomit), so makes a good match for Sumerian sur “to squirt” fluid from the body.

It is difficult to assert with conviction that the etymology of the word for sewer lies in the bodily function a––sur “to urinate”, for a sewer carries away much that is not urine. However, the use of the verb sur for the discharge of liquid generally is very suggestive. The conclusion here is that Akkadian asurrû “sewer” derives from Sumerian a-sur-ra, a nominalized verbal compound meaning “water-discharger”. The term seems fitting for a facility which carried off human waste flushed with water, mê musâti, and foul water generally, and discharged it outside in a remote location.

Equivocal contexts

There are instances of asurrû that are less obviously related to drainage. Further passages of the terrestrial-omen series make it the habitat of other creeping things, apart from the snakes, mongooses and leeches that were encountered earlier (43–44):

[DIŠ na]p-pil-lu šá a-sur-re-e šá kap-pi šaknū(gar) nu ina bīt(é) amēli(na) innamrū(igi)meš -ma …

Šumma ālu XXXVIII 39′, ed. Freedman Reference Freedman2006a: 276

[¶ (If)] grubs of the a., (the kind) that have wings, appear in a man's house and … (apodosis lost)

DIŠ ina bīt(é) amēli(na) ḫal-lu-la-a-a ina ap-ti bīt(é) amēli(na) (var. ina apti(ab) bīti(é)) a-sur-re-e ú-šá-az-na-an …

DIŠ ina bīt(é) amēli(na) ḫal-lu-la-a-a ina mūši(gi6) a-sur-re-e ú-šá-az-na-an …

DIŠ ina bīt(é) amēli(na) ḫal-lu-la-a-a ina kal u 4 -mi a-sur-re-e ú-šá-az-na-an …

Šumma ālu XIX 30′–32′, ed. Freedman Reference Freedman1998: 278;

var. from Heeßel Reference Heeßel2007: 24 no. 5 ii 15′

¶ (If) in a man's house a centipedeFootnote 22 makes the a. drip at/from the window of a man's house (var. window of a house): … (negative apodosis)

¶ (If) in a man's house a centipede makes the a. drip at night, resp. all day: … (negative apodoses)

Similar omens occur earlier in the series Šumma ālu, at I 163–64 (ed. Freedman Reference Freedman1998: 38). It is uncertain how we are to understand šuznunu, literally “to make rain down” in the omens of passage (44), but the verb occurs with built structures like walls and does not presume a naturally wet environment like a sewer.

Other omens in Šumma ālu that mention asurrû work tolerably well if it was a sewer, but also lack any certain reference to drainage. A passage of four lines reads (45):

DIŠ bītu(é) a-sur-ru-šu ša-lim …

DIŠ bītu(é) a-sur-ru-šu še-eḫ-ḫa-tú i-šu …

DIŠ bītu(é) a-sur-ru-šu epra(saḫar) ittaddâ(šub-šub) a …

DIŠ bītu(é) a-sur-ru-šu imtaqqut(šub-šub) ut …

Šumma ālu VI 33–36, ed. Freedman Reference Freedman1998: 112

¶ (If) a house's a. is in good repair: … (positive apodosis)

¶ (If) a house's a. is crumbling: … (negative apodosis)

¶ (If) a house's a. keeps producing dirt: … (negative apodosis)

¶ (If) a house's a. keeps collapsing: … (negative apodosis)

The symbolic value of the house's asurrû in regard to the well-being of its residents is obvious, but the location of the asurrû is not. The same is true in a later passage of the same text (46):

DIŠ kamūnu(uzu-diri) ina išid(suḫuš) bīt(é) amēli(na) innamir(igi) …

DIŠ kamūnu(uzu-diri) ina a-sur-re-e bīti(é) amēli(na) innamir(igi) …

DIŠ kamūnu(uzu-diri) ina ušši(uš8) bīti(é) amēli(na) innamir(igi) …

Šumma ālu XIII 21–23, ed. Freedman Reference Freedman1998: 208

¶ (If) lichen appears at the base of a man's house: … (negative apodosis)

¶ (If) lichen appears at the a. of a man's house: … [(negative apodosis)]

¶ (If) lichen appears at the foundations of a man's house: … (negative apodosis)

This passage is immediately preceded by a set of omens organised on the pattern front–middle–rear. It displays a similar spatial progression, but vertical instead of horizontal: from the bottom of the walls, through the infrastructure, to the footings at the very bottom. This suggests that the asurrû was part of the subterranean structure of a house, but not the very lowest part of the building.

The construction of a house, from the bottom up, is a notion that underlies a line of a Standard Babylonian incantation-prayer to Ištar (47. Ebeling Reference Ebeling1953: 60 and duplicates, l. 9): e-ma ba-áš-mu-u-ma a-sur-ru-ú nadât(šub) at (var. in-na-du-ú) libittu(sig4) “wherever a. is constructed and brickwork laid”. This is a literary expression for “in the society of human beings”, but from it we can infer that making an asurrû was an activity in house-construction that preceded the laying of brick walls. It is not clear, however, that this asurrû is necessarily a drain. Similarly inconclusive is a Standard Babylonian dream omen in which the dreamer sees himself carrying ṭābta(mun) a-sur-re bīti(é)-šú “salt from the a. of his house” (48. Oppenheim Reference Oppenheim1956: 331 x+17).

Contrary contexts

Other attestations of asurrû certainly have nothing to do with drains. Prominent examples occur in passages of mid-first-millennium building inscriptions, from Sargon II of Assyria to Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon. Three Assyrian rulers deploy the identical expression asurrû šus ḫuru “to surround the asurrû (sing.)”. Sargon reports on his inscribed bull-colossi and parallel texts that he decorated the monumental buildings of his new capital, Dūr-Šarrukīn, with bas-reliefs (49):

as-kup-pi na4 pi-li rabbâti(gal)meš da-ád-me ki-šit-ti qa-ti-ia ṣe-ru-uš-ši-in ab-šim-ma a-sur-ru-ši-in ú-šá-as-ḫi-ra a-na tab-ra-a-ti ú-šá-lik

Fuchs Reference Fuchs1994: 70 ll. 77–79

I depicted the towns that I had conquered on large slabs of limestone and surrounded their a. with them, I made them a wondrous sight.

In the cylinders that commemorate the completion of his palace at Nineveh, Sennacherib describes doing likewise in that building. Three passages using asurrû šus ḫuru occur repeatedly in the various versions of the building reports. One is almost identical to Sargon's (50):

as-kup-pat na4 pi-i-li rab-ba-a-ti da-ád-me na-ki-ri ki-šit-ti qātī(šu)min -ia qé-re-eb-ši-in es-si-ḫa (i.e. ēsiqa) a-sur-ru-ši-in ú-šá-as-ḫi-ra a-na tab-ra-a-ti ú-šá-lik

e.g. Senn. 1: 86, ed. Grayson and Novotny Reference Grayson and Novotny2012: 39

I engraved the enemy towns that I had conquered in large slabs of limestone and surrounded their a. with them, I made them a wondrous sight.

The second passage mentions a greater variety of raw materials but omits the detail about the conquered towns (51):

askuppāt(kun4)meš na4 dúr-mi-na-bàn-da na4 giš-nu11-gal ù askuppāt(kun4)meš na4 pi-li rabbâti(gal)meš a-sur-ru-šin ú-šá-as-ḫi-ra a-na tab-ra-a-te ú-šá-lik

e.g. Senn. 17 vii 41–44, ed. Grayson and Novotny Reference Grayson and Novotny2012: 142

I surrounded their (= the palace chambers') a. with slabs of breccia and alabaster and large slabs of limestone, I made them a wondrous sight.

The third passage reveals a motivation for the practice (52):

la-ba-riš ūmī(u4)meš i-na mīl(illu) kiš-šá-ti tem-me-en-šú la e-né-še as-kup-pat na4 pi-i-li rab-ba-a-ti a-sur-ru-šu ú-šá-as-ḫi-ra ú-dan-nin šu-pu-uk-šú

e.g. Senn. 3: 52, ed. Grayson and Novotny Reference Grayson and Novotny2012: 54

So that in time to come its (the palace terrace's) foundation platform should not grow weak through (any) abnormally high flood, I surrounded its a. with large slabs of limestone (and so) reinforced its fabric.

Almost the same passage occurs in other inscriptions of Sennacherib, but with ki-su-ú-šu “its retaining wall” written instead of asurrūšu (e.g. Senn. 17 vi 7–10, ed. Grayson and Novotny Reference Grayson and Novotny2012: 138). Esarhaddon carries on the tradition in his long prism inscription (53):

na4 askuppāt(kun4)meš na4 giš-nu11-gal a-sur-ru-šú ú-šá-as-ḫir-ma gušūrī(giš-ùr)meš giš erēni(eren) ṣīrūti(maḫ)meš ú-šat-ri-ṣa eli(ugu)-šú

Esarh. 1 vi 7–8, ed. Leichty Reference Leichty2011: 24

I surrounded its a. with slabs of alabaster and stretched lofty (ceiling)-beams of cedar over it.

The inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar II, especially, make it certain that a kisû is a retaining wall that abuts the lower part of a mud-brick wall to reinforce it (Baumgartner Reference Baumgartner1925: 132–38). If asurrû in the passages quoted in the preceding paragraphs is a synonym of kisû, as variants of (52) suggest, it is clear that these late kings employed the term to mean the lower part of a wall. This was a visible structure suitable for decoration with limestone slabs whose scenes in bas-relief were intended to awe those who passed by.

For Ashurbanipal, however, the asurrû was perhaps a structure too deep to be visible. He uses the word in the context of clearing away the ruined superstructure of the citadel wall of Nineveh (54):

dūru(bàd) šu-a-tú ša la-ba-riš illiku(du) ku e-na-ḫu uššû(uš8)-šú mi-qit-ta-šú ad-ke ak-šu-da a-sur-ru-šu ina eš-qí aban(na4) šadî(kur) i tem-me-en-šú ú-dan-nin

Prism D viii 69–71, ed. Millard Reference Millard1968: 103, Borger Reference Borger1996: 118

That wall, which had grown old and whose footings had grown weak, I cleared away its ruins and reached its a. I strengthened its foundation platform with solid rock.

In this passage the asurrû seems to be part of the wall's subterranean foundations. There is further evidence for subterranean asurrû under a city wall. One of Nebuchadnezzar II's cylinders reporting his construction of the eastern city wall at Babylon reads (55):

i-ta-at dūri(bàd) a-na du-un-nu-nim ú-ša-al-li-iš-ma in-du a-sur-ra-a ra-bí-a-am iš-di dūr(bàd) a-gur-ri e-mi-id-ma in i-ra-at ⟨…⟩ ab-ni-ma ú-ša-ar-ši-id te-me-en-šu

VAS I 40 ii 3–8, ed. Langdon Reference Langdon and Zehnpfund1912: 82

In order to strengthen the area outside the (double inner) wall I made a third (wall): I built as a support a large a. up against the base of a baked-brick wall. I built it on the breast of (the underworld) and made its foundation platform solid.

The associated brick inscription omits indu (56):

i-ta-at dūri(bàd) a-na du-un-nu-nim ú-ša-al-li-iš-ma a-sur-ra-a ra-ba-a i-na kupri(esir-è-a) ù agurri(sig4-al-ùr-ra) iš-di dūri(bàd) e-mi-id

VAS I 46: 6–7, ed. Langdon Reference Langdon and Zehnpfund1912: 196

In order to strengthen the area outside the (double inner) wall I made a third (wall): I built a large a. in bitumen and baked brick up against the wall's base.

Here the asurrû seems to be a subterranean structure that functions like a kisû, giving strength to the wall's superstructure, and waterproofed against groundwater and floods. The term indu asurrê is not immediately clear, but it occurs again in the lexical text Antagal (57. D 120): [x]x-šu úr = in-du a-sur “support of a.”, and in the terrestrial-omen series Šumma ālu (58. V 112, ed. Freedman Reference Freedman1998: 96): DIŠ bītu(é) in-di a-sur-re-e um-mu-ud … “¶ (If) a house is held up by the support (stanchion?) of an a.: … (positive apodosis).” In both passages indu asurrê is part of the foundations of a building.

These passages of first-millennium building inscriptions all attest the use of the word asurrû with reference not to a drain or sewer but to a solid structure at the foot of a wall or below it. In the light of this usage it may well be that some, or all, of the instances of asurrû in Standard Babylonian texts identified above as not certainly to do with sewers (34, 43–48), might also refer to the base of a wall.

Here it is necessary to revisit the terminology of house-rental contracts. As mentioned above, Old Babylonian house-rental contracts from the mid-second millennium and Neo- and Late Babylonian contracts from the mid-first millennium know asurrû as one of the two parts of a house—the other was the roof—that a tenant could be explicitly obliged by contractual agreement to keep in good shape. The pertinent clauses have already been introduced: (22) asurrâm udannan “he shall keep the a. strong” in Old Babylonian and (23) batqu ša asurrê i ṣabbat “he shall keep the a. in good repair” in the first millennium. As observed above, the former is quite rare, the latter much more common. The later expression, batqu ṣabātu, could denote the maintenance of various facilities, for example irrigation ditches in a date plantation (VAS V 26: 7), and can reasonably suit the maintenance of walls as well as sewers. Its Old Babylonian counterpart, dunnunum “to strengthen, keep strong”, is less obviously applicable to the maintenance of sewers than it is to the upkeep of walls. The base of a mud-brick wall is highly vulnerable to erosion by rain splash if a good coat of mud plaster is not applied and kept in good repair. A wall whose lower part is not protected in this way will eventually weaken and topple over.Footnote 23 Thus the regular reinforcement of the wall's base by plastering was of particular importance to the landlord. The Old Babylonian use of the verb dunnunum suggests that the meaning of asurrû observed in first-millennium building inscriptions already obtained in the Old Babylonian house-rental contracts: a tenant bound by the clause asurrâm udannan was obliged to maintain the mud plaster that protected the base of the house's exterior walls.

That being so, the expectation would be that the first-millennium rental contracts deployed asurrû in the same meaning, with reference to the lower part of exposed walls. Such a conclusion is supported by a quantitative contrast between the documentary and archaeological evidence.Footnote 24 I do not know exactly what proportion of extant Neo- and Late Babylonian house-rental contracts contains references to the asurrû, but it seems that such clauses are more common than not (n. 14), while the proportion of excavated dwelling houses equipped with foul-water drainage was, even in the first millennium, very small. This discrepancy in itself makes it improbable that asurrû in first-millennium house-rental contracts was a sewer.

The evidence presented above indicates that the word asurrû had two meanings: (a) sewer and (b) wall footing or similar. The question arises, how did that come about?

The semantic evolution of asurrû

The etymology of the Akkadian word asurrû, from Sumerian a-sur-ra “water-discharger”, suits its application to a sewer that discharges in the open, which is thus identified as its primary meaning. Its semantic evolution, to mean also “wall footings”, is accordingly a secondary development arising from their shared location in a building's infrastructure. This analysis is supported by the documentary evidence. The majority of Old Babylonian attestations of asurrû noted above fit a meaning “sewer” and, importantly, they come from a variety of genres: a letter (28), magic spells (29–31), and an omen text (33). The only exception is the house-lease clause (22) and the royal inscriptions that adapt it (20–21). It would appear from the available evidence that the secondary development was confined at first to the legal tradition.

The lexical equation of úr and asurrû is reported in the passages quoted above (14–17). The oldest of them is the bilingual legal handbook Ana ittīšu, which is only extant in first-millennium copies but on internal evidence certainly of Old Babylonian origin (Landsberger Reference Landsberger1937: ii–iii, Cavigneaux Reference Cavigneaux1983: 631). The juxtaposition of úr and asurrû seen there was perhaps actually first asserted in the Old Babylonian academic legal tradition from which Ana ittīšu arose. That asurrûm gained a new meaning, in addition to its etymological meaning, was probably a consequence of that very juxtaposition. Lexical lists and other pedagogical texts existed in a dynamic intellectual environment: they recorded meaning but also created and perpetuated it. The later lexical evidence shows that in explaining the word asurrû, the academic tradition privileged the usage of Old Babylonian house-rental contracts, in which asurrû was adopted to refer to the lower parts of a building's walls (14–19), over the etymological meaning “sewer” (24). In this they could cite the authority of Ana ittīšu (17).

Academic texts, including pedagogical tools such as lexical lists, existed not in isolation but as an intellectual community of texts. The lexical entries quoted here occur in post-Old Babylonian lexical texts, especially in those that can be characterised as Akkado-Sumerian glossaries that were “designed as word indexes to earlier Sumerian-oriented lexica” (Finkel Reference Finkel1982: 38). These highly eclectic texts incorporate in their lists, among more routine material, synonyms, near synonyms, literary (non-literal) translations and academic speculation. Some entries rest on traditional lexical equations; others derive from the exegesis of literary texts (Michalowski Reference Michalowski and Braun1998). What was of interest was not only precise semantic correspondence, but also the near association of Sumerian and Akkadian words in the traditional corpus of written texts. One such near association was úr // asurrû in Ana ittīšu.

Against this background the entry úr = asurrû in the lexical list A (14) can be explained as derivative of the juxtaposition of úr-re ki-in ab-ak-e and asurrâ ikaššir in Ana ittīšu (17). The literary translation of úr é-gar-ra as asurrâ in Udug- ḫul (32) probably arose from knowledge of (14) and itself gave rise to the equivalence úr é-gar = asurrû in Antagal (16). Similarly, a lost bilingual text could be the source of the entry úr é-a = asurrû in Nabnītu (15). The equation išdi bīti = asurrû in Malku (18–19) is the same entry as (15) but with the Sumerian úr é-a more mechanically translated in the left-hand column. Thus a dialectical network of creative interactions connects our sources.

The same dynamic intertextual relationships came into play in reading and transmission. Pedagogical texts such as the lexical lists had considerable influence on how the traditional texts were understood and passed down. The Standard Babylonian academic texts in which asurrû occurs are known mainly from first-millennium copies but their date of composition (or compilation from older sources) lies near the end of the second millennium. In these texts, mostly technical literature such as omens, incantations and medical recipes, asurrû usually means “sewer” (13, 25–27, 35–40), but there are attestations where it is not clear whether to take it as “sewer” or “base of wall” (34, 43–44, 48), and then there are contexts that probably favour “base of a wall” (45–47, 58). The secondary meaning that in the Old Babylonian period had been confined to the legal tradition was beginning to enter other academic genres, no doubt because that was the meaning which was more prominent in the lexical texts.

In the eighth century one may suppose that the highly educated Sargonid chancellery scribes lighted upon asurrû in the lexical texts and used it in building inscriptions as an exotic literary synonym of common kisû “retaining wall” (49–54). This they would hardly have done if they had any knowledge of its unsavoury etymological meaning. When Nebuchadnezzar II's scribes used the word in similar contexts in his building inscriptions relating to the reinforcement of the city walls of Babylon (55–56), at a time when asurrû was commonly so deployed in Babylonian legal terminology (23), it is a sure indication that the original meaning of asurrû had disappeared even among the learned scholars of Babylonia.

With the knowledge that asurrû once meant “sewer” forgotten even in the academy, Assyrian and Babylonian scholars of the mid- and late first millennium must have found many passages of the old traditional literature puzzling, and wondered, for example, why those texts associated snakes, mongooses and pigs with the asurrû. Commentary texts demonstrate that the literary and academic legacy of the preceding ages posed many other difficulties of comprehension to later scholars, and that much intellectual energy was expended on explicating them. Opportunities must have arisen in reading these passages both for confusion and for the hermeneutic reinterpretation of which Babylonian scholarship was fond. In time, perhaps, there will come to light a piece of learned commentary devoted to explaining the word asurrû.

Conclusions