How might we define English opera in the seventeenth century? Whole books have been written on this topic, and because of the variable terminology with which seventeenth-century writers labelled their works (‘opera’, ‘dramatick opera’, ‘masque’, ‘comedy’, ‘tragedy’), it is unlikely that absolute clarity will ever be had.1 Indeed, the English had a capacious and fluid notion of what constituted opera during the seventeenth century, and we should adjust our overly narrow definitions if we are to understand English opera as people in the seventeenth century did: as a genre that sometimes was fully sung, but, more often than not, included spoken dialogue.2

Although the English were not enamoured of fully sung opera, they had a long tradition of pairing drama with music and dance – elements that would become the building blocks of English opera. Elizabethan and Jacobean plays included instrumental music cues for entrances and exits and underscoring to accompany stage action, and vocal music was required in a range of conventionalised circumstances.3 Servants sing to their masters and mistresses, the inebriated sing drinking songs, and supernatural creatures or characters hoping to summon supernatural forces through ritual also sing. Fools, passionate lovers, melancholics, and mad people lapse into song as well, musico-dramatic signifiers of their instability.4 Dances also played a role during this early period – many of Shakespeare’s comedies end with them (for example, As You Like It), but dancing was included in the darkest tragedies (Romeo and Juliet) and even in histories (Henry VIII).5

Thus, from quite early on, the English had developed conventional situations for music-making in their drama. Over time, these musical scenes expanded: in a sense, the transition from play to opera was a change of degree, not kind. The transformation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth into an increasingly musical play exemplifies this trend. When it premièred in 1606, the witches probably had no music. At some point in its early performance history, material from Thomas Middleton’s The Witch (1615–1616), a play with substantial music, was interpolated into the Scottish play.6 After the Restoration it was adapted and changed even further – music became central to its popularity and success.

Court Masques

The court masque – a genre that was populated by allegorical characters and combined spoken text, songs, and choruses; dances; and lavish scenic effects – was codified during the Jacobean and Caroline eras, and its form would have a profound influence on the development of English opera. Playwright Ben Jonson (1572–1637) and designer Inigo Jones (c. 1573–1652), created the template for the court masque during the reign of James I. It began with an antimasque, which included unruly, disruptive, and/or low-class characters, usually played by professionals. After declaiming, sometimes singing, and often dancing in grotesque ways (as indicated by the rapidly shifting metres found in this music), these characters would be banished from the stage by the noble characters of the main masque, portrayed by a mix of professionals and aristocrats, sometimes even including the queen herself. Although the aristocrats generally left the singing and acting to the professionals, they were keen dancers, and during the lengthy revels at the end of the evening they demonstrated their terpsichorean prowess.7 The dances for the main masque were more rhythmically regular, and some used French dance types. Indeed, the influence of the French ballet de cour upon the English court masque was considerable and would only increase with the ascension of Charles I and his French wife, Henrietta Maria, to the throne in 1625.8

The composer Nicholas Lanier (bap. 1588–1666) made considerable innovations to the vocal music for the court masque, but we must bear in mind that his experiments with musical declamation were conducted and encouraged by a small group of elites rather than in response to a widespread public thirst for recitative or Italianate opera. Lanier’s ‘Bring away this sacred tree’ from Thomas Campion’s Somerset Masque (1613) is one of the earliest examples of what Ian Spink calls a ‘declamatory ayre’ – the vocal line matches the scansion of the text and is set to a chordal accompaniment.9 Ben Jonson claims in his Works (1640) that The Vision of Delight (1617) and Lovers Made Men (1617) both included music in ‘stylo recitativo’. Lovers Made Men was particularly remarkable, for the ‘whole Masque was sung (after the Italian manner) Stylo recitativo by Master Nicholas Lanier’.10 Scholars have cast doubt upon these claims, believing that Lanier probably would not have composed recitative until after his visits to Italy in 1625 and 1628.11 Whatever the case, Lanier’s 1617 settings do not survive; the first extant example of English recitative is his Hero and Leander (1628 or later), although all the sources date to after 1660, so it is impossible to know when he actually composed it.12

Operatic Experiments during the Civil War and Interregnum

The court masque and plays with music for the public stage were the primary forms of dramatic music until the closure of the public theatres in 1642 and the dissolution of the court musical establishment due to the Civil War, which culminated in the regicide of Charles I in 1649. Despite these disruptions, music and theatre did not completely founder during this difficult period. Oliver Cromwell believed the public theatre to be a hotbed of inequity, but he was not entirely opposed to musical entertainments, and some who had served the previous regime, such as James Shirley and William Davenant, found opportunity in adversity. Shirley wrote the masque Cupid and Death in honour of the visit of the Portuguese ambassador on 26 March 1653, potentially suggesting state sponsorship. The first version featured music by Christopher Gibbons (bap. 1615–1676); his score seems to have been revised by Matthew Locke (1621/3–1677) for a 1659 revival at Leicester Fields.13 Musically, Cupid and Death is an important forerunner to the dramatick operas (i.e., plays with substantial musical scenes, dancing, instrumental music, and spectacle) of Matthew Locke and Henry Purcell (1659–1695).14 Locke’s expressive and florid recitative for the 1659 performance paves the way for Purcell’s later experiments, as does his use of choral responses. Indeed, Cupid and Death is an important intermediary between the Caroline court masque and the Restoration musical forms to come.15 It has an ‘entry’ structure, a holdover from the English court masque as well as the French ballet de cour, spoken dialogue, songs, choruses, dances, and scenic spectacle (i.e., Mercury ‘descending upon a Cloud’).16 The division of labour found in Cupid and Death – main characters tend not to sing – also becomes the norm, with a few exceptions, in dramatick opera.

Locke’s music for the 1659 Cupid and Death revival may provide a window into an earlier Commonwealth experiment whose music has been lost.17 In September 1656 Davenant, a Royalist who had written Caroline court masques, penned the libretto for The Siege of Rhodes, the first fully sung English opera. The score to The Siege of Rhodes was a collaborative affair, written by Henry Cooke (c. 1615–1672; the organiser, who composed entries two and three), Henry Lawes (bap. 1596–1662; first and fifth entries), Locke (fourth entry), Charles Coleman (d. 1664; instrumental music), and George Hudson (d. 1672; instrumental music). The versification of the libretto indicates that much of the work would have been sung in recitative, and the chorus played a significant role (as it did in Cupid and Death), appearing at the end of each scene. Also, like Cupid and Death, Davenant’s opera was organised according to ‘entries’. Scenic display, in this case supplied by Jones’s protégé John Webb, was also tremendously important. Davenant continued his operatic experiments with The Cruelty of the Spaniards in Peru (1658) and The History of Sir Francis Drake (1659), although the precise nature of these entertainments is unclear, as most of the music has been lost. After the Restoration, Davenant appears to have given up on fully sung opera, opting instead for the hybrid approach found in Cupid and Death.18

Various Approaches: Music and/or Drama

After the Restoration, Charles II sought to emulate the elaborate entertainments he had enjoyed in exile at the court of Louis XIV, although he did not have the financial resources to fully support his ambitions. Nevertheless, he restored the court musical establishment, and for many years there was a free flow of personnel between the public stage and the court.19 Locke and John Banister (1624/5–1679), two of the primary composers for Charles’s Twenty-Four Violins, the instrumental ensemble at court modelled on Louis XIV’s group, composed much of the music for the public theatres during this period, because this ensemble was working regularly in the theatres by the king’s command.20 The two patent companies – Davenant’s Duke’s Company and Thomas Killigrew’s King’s Company – benefitted substantially from this arrangement. Killigrew’s company mounted a series of highly musical plays, including Sir Robert Howard and John Dryden’s The Indian Queen (1664) with music by Banister.21 Davenant’s company was granted the rights to some of Shakespeare’s plays by the king, and he reshaped the work of the Bard to suit new tastes, significantly expanding the role of music in two of Shakespeare’s plays: Macbeth (1663 or 1664) and The Tempest, co-written with John Dryden (1667). 22

The structure in Davenant’s revisions of Shakespeare affected English operatic conventions going forward. In fact, they are very similar to what John Dryden would call ‘dramatick opera’, as they combine spoken text with songs, choruses, and dance. For instance, in Act II scene 5 of Davenant’s Macbeth, non-singing characters (the Macduffs) encounter the witches singing and dancing. Also, the witches speak and sing in Macbeth, serving as intermediaries between the two modes of discourse: a convention we will see with other characters in English dramatick operas of the 1670s and onwards.23 Dryden and Davenant’s adaptation of The Tempest functions in a similar way, expanding upon the music in Shakespeare and adding new opportunities for singing that correspond with established conventions. The playwrights amplify Ariel’s singing role, including a new ‘echo song’ for Ariel and Ferdinand, ‘Go thy way’;24 and they add a supernatural musical extravaganza, a ‘Masque of Devils’, which serves a similar musico-dramatic purpose as the witches’ scene in Act II scene 5 in Macbeth.25

The 1670s saw the further expansion of these operatic impulses. In 1670 the actor and theatre manager Thomas Betterton (1635–1710) visited France to learn more about Continental practices, and in 1671 the Duke’s company moved into the new Dorset Garden Theatre, which was equipped with machinery.26 Henceforth, English opera became increasingly indebted to French models and incorporated more special effects.27 The prompter John Downes recalls a revival of The Tempest at Dorset Garden from 1674:

having all New in it; as Scenes, Machines; particularly, one Scene Painted and Myriads of Ariel Spirits; and another flying away, with a Table Furnisht out with Fruits, Sweet meats and all sorts of Viands; just when Duke Trinculo and his Companions, were going to Dinner; all things perform’d in it so Admirably well, that not any succeeding Opera got more Money.28

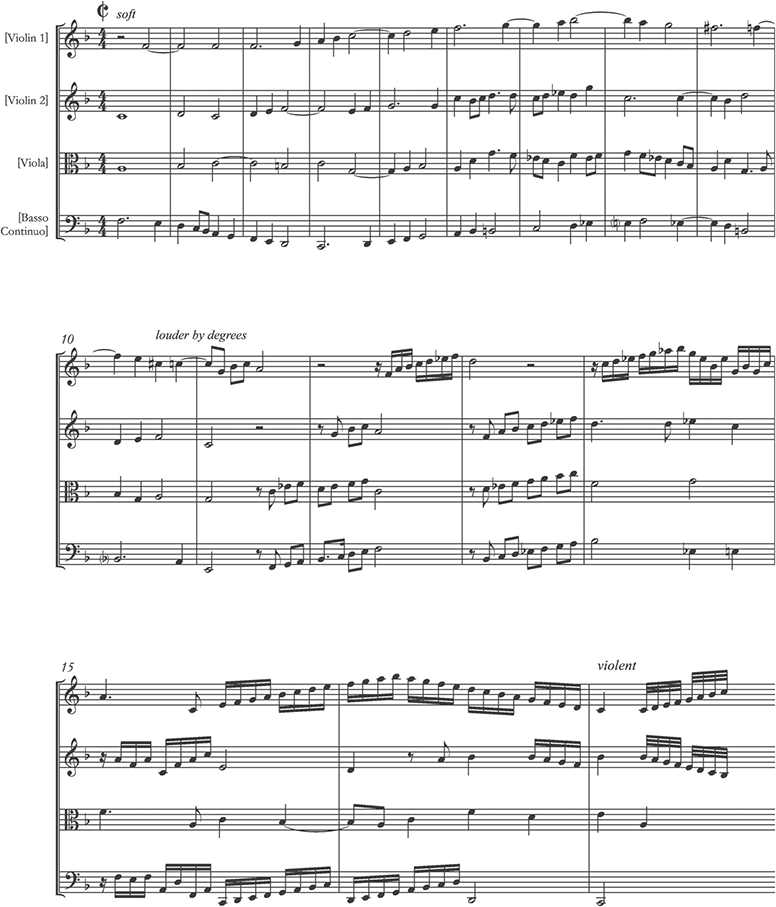

This Tempest was probably revised by Thomas Shadwell (1640 or 1641–1692) and includes songs by Banister, Pelham Humfrey (1647/8–1674), Pietro Reggio (bap. 1632–1685), and James Hart (1647–1718); instrumental music by Locke and possibly Robert Smith;29 and dances by Giovanni Battista Draghi (c. 1640–1708) (lost). The Tempest is also notable for its integration of instrumental music into the dramatic action, with Locke’s ‘Curtain Tune’ being a prime exemplar. In his self-published score he incorporates detailed performance instructions (i.e., soft, louder by degrees, violent, etc.) and this, coupled with running semiquaver and demisemiquaver passages and tortured chromaticism, evokes the flying spirits, sinking ship, blustery winds, and stormy waters described in the opening stage direction of the play (see Example 12.1). In other cases, integration of music and drama is less of a priority. For instance, Humfrey’s Act V ‘Masque of Neptune’ is only tangentially connected to the main plot: Prospero calls forth the entertainment to ‘make amends’ for his misdeeds. We should not presume, though, that masques of this kind were deficient or lacking somehow. These episodes had their own internal logic and were very successful in a dramaturgical sense, as music (instrumental and vocal), dance, and elaborate spectacle worked syncretically to provoke awe and wonder in both the onstage and offstage audience.30

Example 12.1 Matthew Locke, The English opera, or, The vocal musick in Psyche: with the instrumental therein intermix’d: to which is adjoyned the instrumental musick in The tempest (London: Printed by T. Radcliff and N. Thompson for the author, 1675), ‘Curtain Tune’, from The Tempest, 68

“A PDF version of this example is available for download on Cambridge Core and via www.cambridge.org/9780521823593”

Psyche, also with a text by Shadwell (adapted from Lully, Molière, Pierre Corneille, and Philippe Quinault’s tragédie-ballet, Psyché; 1671) and music by Locke, was presented the following year (1675), and its score, along with the instrumental music from The Tempest, was disseminated by Locke in his aforementioned self-published score, THE ENGLISH OPERA, OR, The Vocal Musick IN PSYCHE (1675).31 In Locke’s lively introduction to the volume he makes the case that Psyche, is, in fact, a proper opera, for it possesses all the elements of its Italian counterpart: ‘splendid Scenes and Machines’, as well as varied ‘kinds of Musick as the Subject requires’. He finishes by stating:

And therefore it [Psyche] may justly wear the Title [of opera], though all the Tragedy be not in Musick: for the Author prudently consider’d, that though Italy was, and is the great Academy of the World for that Science and way of Entertainment, England is not: and therefore mixt it with interlocutions, as more proper to our Genius.32

Locke’s approach to music and drama – along with the operatic Shakespearean experiments of the 1660s and 1670s – provides a template for the ways in which music, drama, and spectacle could work together on the public stage. In some cases, encapsulated entertainments are presented for onstage auditors, and, in others, music and drama flow seamlessly into each other, in part because one of the main characters, Venus, sings and speaks. Locke also composed a light-hearted drinking song and chorus for Vulcan, Cyclops, and their followers. The combination of the comic with the tragic carries over into later English opera, probably by commercial design.33

Psyche, like The Tempest, had a multi-national production team behind it. Locke, an English composer, provided the bulk of the music, but the Italian Draghi wrote the instrumental music while the most famous Master of France, Monsieur St. Andrée’ made the dances.34 These collaborations were facilitated by the influx of musicians from the Continent, a result of Charles’s musical tastes and his wife’s need for musicians to staff her Catholic Chapel.35 Other immigrants, such as the Italian Reggio and the librettist and playwright Peter Motteux (1663–1718), a Huguenot refugee, came in the 1660s, 1670s, and 1680s, quickly finding opportunity in the theatre of their adopted land.

French and English Opera

Royal occasions seem to have prompted some of these operatic performances in the public theatre: Betterton may have commissioned Psyche in 1673 for the marriage of the Duke of York (later James II) and Mary of Modena. It is puzzling that it was not performed until 1675, but the delay may have been caused by music politics at court. In 1673 Robert Cambert (c. 1628–1677) – the composer of the first French opera, Pomone (1671) – arrived in England with some French musicians.36 Early in 1674 he presented the Ballet et musique pour le divertissement du roy de la Grande-Bretagne in celebration of the Duke of York and Mary of Modena’s marriage. French music, at least temporarily, had supplanted Locke’s ‘English Opera’. On 30 March, Charles inaugurated a French-style ‘Royall Academy of Musick’ with a revised version of Cambert’s fully sung ‘opera’, Ariane, ou Le marriage de Bacchus, presented at Drury Lane with additional music supplied by French-trained Catalan composer Louis Grabu (fl. 1665–1694).37

Although Cambert’s efforts were not well received, Charles’s Francophilia deeply affected the few court-based entertainments from this period that survive, even if the king balanced his love of French music with the judicious employment of English composers. About some entertainments with music produced at court, such as Rare en tout (1677), performed for Charles II’s birthday, little is known beyond the composer: Jacques [James] Paisible (c. 1656–1721), a French wind player who had come to England with Cambert, provided the score.38 However, there is copious documentary evidence about John Crowne’s Calisto (1675). Almost all of the music is by Nicholas Staggins (d. 1700), Master of the King’s Music, who succeeded Grabu in the post (the Catholic Grabu may have run afoul of the Test Act of 1673, which, although applied inconsistently, required all those at court to take an oath of loyalty to the Church of England).39 Calisto, like Cupid and Death in 1653, is called a ‘masque’ on the title page and has some elements in common with the older English court masque, including amateur performers, in this case the royal princesses, Anne and Mary; the Duke of Monmouth; and other courtiers.40 Calisto was deeply influenced by the comédie-ballet and features a French overture, an allegorical prologue, which, like the prologue of Ariane, features a female singer as the River Thames, and danced entries for different sets of characters (gypsies, satyrs, Basques, etc.), a French feature that had been taken up in earlier English court masques and Shirley’s and Davenant’s operatic experiments of the 1650s.41 With the exception of the sung allegorical prologue, in Calisto, the musical episodes take place at the end of each act. Integration of music and drama is not a high priority. Perhaps this separation was born of necessity; it meant that the youthful performers could practice the musical and dramatic components separately. Indeed, this lack of integration, sometimes seen on the public stage, might have served a practical purpose: to expedite the rehearsal process.42

Through-Composed Operas and Masques of the 1680s

Determined to enjoy French-style opera at home, in the summer of 1683 Charles II sent Betterton to Paris to commission Jean-Baptiste Lully and his Académie Royale de Musique to produce a tragédie en musique. Betterton was unsuccessful in his quest, and so he brought back Grabu, who since 1679 had been living in exile in Paris, ‘to represent something at least like an Opera in England for his Majestyes diversion’.43 Dryden, who had collaborated with Davenant on the adaptation of The Tempest, and Grabu began work on what would become Albion and Albanius, an opera to be performed at Dorset Garden. Dryden’s planned opera originally had a through-composed allegorical prologue in the same vein as Calisto’s, followed by an English-style opera with spoken dialogue, spectacle, dance, and music for soloists and chorus. By August 1684, possibly because the king preferred French-style opera, Dryden had altered his project; the English opera would later be revised and performed as King Arthur (1691).44 He expanded the allegorical prologue into a three-act opera, Albion and Albanius, which addressed the key moments of Charles’s reign.45 It was completed in 1684 but was shelved because of the unexpected death of Charles in February 1685. Dryden and Grabu worked to accommodate the new political reality, and the opera was finally performed at Dorset Garden in early June, although the run was cut short because Charles’s illegitimate son, the Protestant Duke of Monmouth, attempted to seize the throne from the Catholic James II.

Dryden’s preface to the printed libretto reveals that the battle between French and English music was hardly settled: ‘some English Musicians, and their Scholars’ had objected to Dryden’s collaboration with Grabu, because the ‘imputation of being a French-man’ was enough to prejudice them.46 Although Grabu was actually Catalan, he was French by training, and not surprisingly his musical idiom is entirely French.47 Grabu set the recitative sections of Albion and Albanius accordingly, incorporating frequent changes from duple to triple metre that are typical of the French récit mesuré – a technique not generally used by English composers. In some cases Grabu’s score incorporates French conventions that would become anglicised, in particular, the use of dance as a structural device in opera. Most impressive in this regard is his lengthy C major chaconne at the end of the second act, ‘Ye nymphs, the charge is royal’, which is admirable for its variety of instrumental and vocal writing.48

In 1683, the same year that Betterton departed for France, a native English entertainment was being planned at court. This too would be a through-composed work, but on a mythological topic – Venus and Adonis. One of the earliest manuscripts describes it as ‘A Masque for ye entertainment of ye King’,49 and circumstantial evidence indicates that it was performed on 19 February 1683.50 It may have been associated with Staggins and John Blow’s petition in April 1683 to ‘erect’ an ‘Academy or Opera of Musick’, a possible response to the failed academy associated with Cambert or to the prospect of Grabu’s return to England.51 Based on stylistic evidence, James Winn has posited that the librettist may have been Anne Kingsmill, a lady-in-waiting to Mary of Modena, the Duke of York’s second wife.52 The cast included Mary (Moll) Davis, the king’s former mistress, as Venus, and their illegitimate daughter, Lady Mary Tudor, as Cupid.

Blow’s masque possesses some features seen in previous entertainments: a mythological topic and French-inspired music (a French overture, danced ‘entries’, including a ‘Sarabrand’ [sic] for the Graces, and a chaconne ground), pervasive use of the chorus, a mixture of comedy with tragedy, and a style of florid recitative adapted from Locke.53 In other respects Venus and Adonis was unusual. Musically, the most notable difference between Venus and Adonis and the English-style operas of the 1660s and 1670s was that it was through-composed – Blow was the first English composer to attempt such a thing since the Interregnum. With its comments directed to dissolute courtiers in the prologue (‘At court I find constant and true / Only an aged lord or two’) and its satirical Act II spelling lesson (‘M-E-R-C-E-N-A-R-Y’), the libretto has the quality of a private conversation among a small coterie. Venus and Adonis did eventually find a broader audience, most notably at Josias Priest’s boarding school for girls at Chelsea, where, as noted by John Verney on his souvenir libretto (GB-Cu Sel.2.123 [6]), it was presented on 17 April 1684.54

Dido and Aeneas, performed sometime in the late 1680s, is a similar work to Blow’s Venus and Adonis. The only surviving seventeenth-century documentation about this work is a printed libretto from a performance at Priest’s school (GB-Lcm D144), Thomas D’Urfey’s epilogue issued in New Poems (1690), and the song ‘Ah! Belinda’ in Orpheus Britannicus, book 1 (1698).55 After the discovery of Verney’s annotated libretto from the school performance of Venus and Adonis, many wondered if Dido also had its genesis at court, and Bruce Wood and Andrew Pinnock argued for a first performance date shortly after Venus and Adonis.56 More recently, Bryan White discovered a ‘Letter from Aleppo’ in which a factor of the Levant Company, Rowland Sherman, writes to his friend in London, the merchant James Pigott, and requests that he ask ‘Harry’ to prick down the C minor overture to ‘the mask he made for Preists [sic] Ball’. White’s remarkable discovery has, once again, called into question the date and location of Dido’s first performance.57

Musically, Dido incorporates some of the same French components as Venus and Adonis, with its French overture, incorporation of solos with choral responses, and its French-style dances, whose rhythms infiltrate the vocal music, most famously in ‘Fear no danger’, a rondeau duet with chorus.58 Dido also includes influences beyond the French, including the English court masque (the antimasque-influenced music and dances for the Sorceress and her band of witches) and Italian-style opera, particularly in the two ground bass laments for Dido, ‘Ah, Belinda’ and ‘When I am laid in earth’. Purcell chooses his ground basses carefully – the oscillating figure in Dido’s ‘Ah, Belinda’ perfectly encapsulates the Queen’s indecision – and the descending tetrachord – an ‘emblem of lament’ in Venetian opera – is used to great dramatic effect in Dido’s ‘When I am laid in earth’.59

Purcell’s Dramatick Operas

Purcell’s engagement with theatre music only increased after 1690, as he sought new sources of income due to the reduction of the court musical establishment under William III and Mary.60 In 1682 the rival King’s and Duke’s companies had combined into the United Company, so competition had been eliminated, at least for the time being. From 1690 to his premature death in 1695, Purcell composed a remarkable amount of theatre music, including a series of dramatick operas: Dioclesian (1690), King Arthur (1691), The Fairy-Queen (1692, 1693), and The Indian Queen (1695). Continuing earlier practises, most of these dramatick operas were adaptations of earlier works.

The driving force behind these dramatick operas was a by-now familiar figure: Thomas Betterton. Betterton had played both sides of the fence in the 1660s–1680s, during which time he was involved in through-composed operas in the French style (Albion and Albanius) and English-style opera, works that combined spoken text with song.61 In the 1690s, he took on the role of adaptor as well. His first attempt was John Fletcher and Philip Massinger’s tragicomedy The Prophetess (1622), which he transformed into the dramatick opera The Prophetess: Or, The History of Dioclesian.

Betterton expanded pre-existing musical moments and added music in conventional places (for instance ‘What shall I do to show how much I love her’, which Purcell set as a beautiful minuet, performed in Act III as Maximinian gazes longingly upon Aurelia).62 The prophetess Delphia instigates many other musical episodes in the opera, using her supernatural abilities to call forth songs, dance, and spectacle. Dioclesian also continues the dramatick opera tradition (cf. ‘The Masque for Neptune’ in The Tempest) of having a spectacular entertainment in Act V with a tenuous connection to the plot, in this case a pastoral interlude that concludes with an extended chaconne, ‘Triumph victorious Love’, a possible response to Grabu’s chaconne in Albion and Albanius.63 There are also scenes of ceremonial praise and ritualised rejoicing, such as Act IV’s ‘Sound, Fame, thy Brazen Trumpet sound’ in response to Dioclesian’s military victory.

Dioclesian contained beautiful and varied music (the pastoral masque at the end particularly struck the fancy of audiences well into the early eighteenth century),64 but Purcell’s next dramatick opera, King Arthur, performed by the United Company at Dorset Garden, had a newly written text by the experienced Dryden, and as a result this work achieves an unprecedented integration of music and drama. Employing a strategy found in previous dramatick operas, Dryden included intermediaries between the world of speech and song: the Tempest had Ariel, Psyche had Venus, and King Arthur has the spirits Grimbald and Philidel.

King Arthur incorporates scenic spectacle and dance, as well as stock musical scenes: a sung ritual, a drinking song, a rejoicing song after victory in battle, pastoral entertainments, and a spectacular Act V masque with little connection to the plot. But in other respects, Purcell’s music forges new ground. ‘Hither this way’ in Act II expands upon a dramatic situation seen in the famous action duet ‘Go thy way’ from Davenant and Dryden’s Tempest, where Ariel lures Ferdinand into following him. Philidel and his spirit followers coax Arthur and his men to take the correct path, and Purcell responds to Dryden’s evocative textual cues with vivid text painting: the jagged descending line on ‘down you fall, a furlong sinking’ being a prime example (see Example 12.2). Grimbald gamely echoes the airy sprites, but it is to no avail. As Grimbald explains, ‘I had a Voice in Heav’n, ere Sulph’rous Steams / Had damp’d it to a hoarseness’. He does not give up, but his air ‘Let not a moonborn elf’, with its awkward rhythms and high tessitura, renders his attempt ungainly and ridiculous (see Example 12.3). When the competing spirits chime in with a reprise of ‘Hither this way’, it is all too clear that Philidel and his band will triumph.65

Example 12.2 Henry Purcell, King Arthur, ed. Dennis D. Arundell [1928], rev edn. Margaret Laurie (London: Novello, 1971), Philidel, ‘Hither this way’ (excerpt), mm. 26–9.

“A PDF version of this example is available for download on Cambridge Core and via www.cambridge.org/9780521823593”

Example 12.3 Henry Purcell, King Arthur, Grimbald, ‘Let Not a Moonborn Elf’, mm. 1–25.

“A PDF version of this example is available for download on Cambridge Core and via www.cambridge.org/9780521823593”

In the less fully integrated scenes, Purcell also provides music of remarkable invention and variety. The famous Act III Frost Scene, particularly the song for the Cold Genius, is a prime example. Although Purcell may have taken the idea of using wavy lines to signify shivering from Lully’s Isis (1677), the adventurous chromaticism of the Cold Genius’s ‘What pow’r art thou?’ has very little do with the French idiom;66 it is an extension of the musical language of Locke and Blow.67 And the Act V masque has everything from the rollicking comedy of ‘Your hay it is mow’d’ to the sublime minuet song for Venus, ‘Fairest Isle’.

With The Fairy-Queen of the following year, the anonymous adapter, possibly Betterton, returned to Shakespeare for inspiration. This time the adapter chose A Midsummer Night’s Dream for treatment, but instead of expanding scenes that were musical in the original play, as other revisers had done with Macbeth and The Tempest, he often ignored these opportunities, adding scenes entirely of his own invention. Still, many of these interpolated entertainments tick similar dramaturgical boxes to those we have seen before – not surprisingly most of the music is instigated by the fairies, and these scenes are presented in the style of masques: self-contained entertainments directed toward a specific onstage spectator (or spectators). Only the Act II masque has a direct musical analogue in Shakespearean drama; it takes the place of Shakespeare’s lullaby ‘Ye spotted snakes’, as Titania’s fairies first entertain their queen and then present an allegorical masque of Night, Mystery, Secrecy, and Sleep designed to induce slumber.68

Despite the considerable beauties of Purcell’s music, the opera did not turn a significant profit. It was revived almost immediately in 1693, but the state of the musical and textual sources is such that we cannot conclusively know what alterations were made for the 1693 production. The most substantial musical difference between the 1692 and 1693 quartos is the inclusion in the latter of a comical scene of a Drunken Poet tormented by fairies. It is unclear if this was a late revision to the 1692 production that did not make it into the 1692 quarto, or if it was newly written for the 1693 production.69

Purcell wrote one final dramatick opera before his untimely death in 1695, an adaptation of an earlier play, Dryden and Howard’s The Indian Queen (1664).70 He died before he completed the Act V masque, which was set by his brother or cousin, Daniel Purcell (c. 1664 or later–1717). This dramatick opera was performed by very young performers, as most of the veteran actors, including Betterton and actress-singer Anne Bracegirdle (1671–1748), had left to establish a rival theatre at Lincoln’s Inn Fields.71 This means that Betterton was probably not involved with the adaptation, although a document survives from the patentees of the Theatre Royal asking Betterton to undertake the task; Price has suggested that Dryden may have done the adaptation himself.72 Despite the difficult circumstances, Henry Purcell wrote sublime music, most notably for an incantation scene in Act III in which the eponymous Indian queen Zempoalla consults the magician Ismeron regarding her fate. The bass singer Richard Leveridge (1670–1758) performed the role of the sorcerer Ismeron, and his ominous and chromatic G minor recitative ‘You twice ten hundred deities’ and air ‘By the croaking of the toad’ are justifiably famous; the latter imitates hopping with dotted rhythms and includes some very thorny harmonies, including a rare augmented sixth chord on the word ‘unwilling’.73

1695 and Beyond

Although Purcell died in 1695, English opera did not die with him. Post-Purcellian dramatick opera took two tracks: one in which music and drama were consistently integrated, and one in which musico-dramatic cohesion was not as pressing a concern. During the theatre season of 1698–9, two competing visions of dramatick opera went head-to-head. The theatre at Lincoln’s Inn Fields offered John Dennis’s Rinaldo and Armida, with a score by John Eccles (c. 1668–1735) in 1698.74 Although it has some elements in common with Lully’s Armide, Dennis’s text, like that of King Arthur, was newly written. Dennis makes clear in his preface to The Musical Entertainments in the Tragedy of Rinaldo and Armida (1699) that he is deeply interested in providing a rational, coherent entertainment in which music, even the act tunes, play a part in the drama. In 1699 Christopher Rich’s company at the rival theatre at Drury Lane presented their own dramatick opera, Motteux’s adaptation of Fletcher’s The Island Princess (ca. 1621).75 The Island Princess was a collaborative affair, with music provided by Jeremiah Clarke (c. 1674–1707), Leveridge (the Ismeron of The Indian Queen), and Daniel Purcell, as well as Robert King (c. 1660–c. 1726), Thomas Morgan (fl. 1691–9), and William Williams (1765–1701).76 The Island Princess was a massive success; only the 1674 version of The Tempest was revived more often in the first few decades of the eighteenth century.77 Although the music in Acts II, III, and IV works in conjunction with the plot (particularly the ‘Enthusiastick Song’ written by Leveridge for his own performance as a superannuated Brahmin), elsewhere the music’s connection with the drama is tenuous (the Act IV rustic dialogue and the Act V ‘The Four Seasons or Love in every Age’).78

The other predominant operatic form, the through-composed miniature, was transferred to the public stage, interpolated into otherwise spoken plays, or used as an afterpiece. Most of these miniatures were given at Lincoln’s Inn Fields; as Robert Hume observes, these through-composed works, which prioritise musical pleasures over scenic display, were ‘what an under-capitalised company in a minimal theater could afford’.79 Frequently called ‘masques’ on their title pages, these works are akin to Venus and Adonis and Dido and Aeneas – other small-scale operatic works on an intimate scale. Notable examples include Eccles and Gottfried [Godfrey] Finger’s (c. 1660–1730) setting of Motteux’s The Loves of Mars and Venus (1696); Daniel Purcell and Finger’s setting of Dryden’s The Secular Masque (1700); Eccles’s setting of Motteux’s Acis and Galatea (1701); and William Congreve’s (1670–1729) The Judgment of Paris (1701) – set by Eccles, Daniel Purcell, John Weldon (1676–1736), and Finger as part of a ‘song contest’ to encourage music.80

Around the turn of the century, native English composers also began to compose full-length, fully sung operas in an attempt to compete with the fashionable Italian opera. In these works, one sees the continuation of older English and French traditions together with an increased engagement with the Italian style. They include Eccles and Congreve’s unstaged Semele (1706) and Thomas Clayton’s (1673–1725) Rosamond (1707; libretto by Joseph Addison, [1672–1719]), performed at Drury Lane. Semele fell afoul of the tumultuous theatre politics of the time, and the failure of Rosamond in March 1707 did not help to make the case that audiences craved fully sung English opera.81

Conclusions

So why did full-length, through-composed opera in English fail to take hold? Lurking behind such a question is the modern assumption that through-composed opera is superior to opera with spoken dialogue, a sentiment not shared by the majority in seventeenth-century England. It was not until the 1690s that through-composed works were successfully performed on the public stage, and usually only as afterpieces or interpolations into spoken plays, as was famously the case with the masques cited above or Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas, inserted into Charles Gildon’s 1700 adaptation of Measure for Measure. Clearly, the English preferred their opera with spoken dialogue – an expansion of the aesthetic found in earlier seventeenth-century plays as well as the court masque. Although some contemporaries bemoaned their compatriots’ lack of appetite for fully sung English opera or critiqued the lack of dramatic coherence in dramatick operas, most audience members seem to have had no such qualms. Dramatick operas by Purcell and others were performed well into the eighteenth century and beyond, demonstrating the genre’s longstanding popularity. As Motteux opined in The Gentleman’s Journal: ‘Other Nations bestow the name Opera only on such Plays whereof every word is sung … experience hath taught us that our English genius will not rellish that perpetual Singing.’82