1. Introduction

1.1. Two debates: The “Great Divergence” and the “Great Enrichment”

In the past 20 years, quantitative approaches to ancient societies have revealed a massive acceleration of economic growth in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Broadberry Reference Broadberry, Guan and Li2018; Maddison Reference Maddison2007; Morris Reference Morris2013). Although per capita income increased slowly, from $400 per year in early farming societies to $2,000 in early modern Britain (expressed in 1990 international or Geary-Khamis dollars), it has exploded in the past two centuries, reaching $40,000 in North America, Western Europe, and Eastern Asia. This increase is two orders of magnitude greater than any experienced before the Industrial Revolution. As Deirdre McCloskey writes: “in the two centuries after 1800 the … goods and services available to the average person in Sweden or Taiwan rose by a factor of 30 or 100. Not 100%, understand – a mere doubling – but in its highest estimate a factor of 100, nearly 10,000%, and at least a factor of 30, or 2,900%. The Great Enrichment of the past two centuries has dwarfed any of the previous and temporary enrichments” (McCloskey Reference McCloskey2016a, p. 10).

What are the origins of modern growth? Two distinct debates are involved in addressing this question.

The first, traditional debate concerns the localization and the timing of the Industrial Revolution: Why did it occur in England? Why not in Holland, France, or China? What were the advantages of England? This is the debate about the “Great Divergence” (Pomeranz Reference Pomeranz2009) between Europe and Asia, and also about the “Little Divergence” (De Pleijt & Van Zanden Reference de Pleijt and Van Zanden2016) between northwestern Europe and the rest of Europe. A range of solutions has been proposed to explain these two divergences: geography and the abundance of coal (Wrigley Reference Wrigley2013), better institutions (Acemoglu & Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012; North & Weingast Reference North and Weingast1989), an early specialization in the textile sector (Allen Reference Allen2009b), greater human capital (Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Mokyr and Ó Gráda2014), the development of the Atlantic trade (Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2005), and more (for a recent review, see Van Neuss Reference Van Neuss2015).

In recent years, however, a second debate has emerged concerning the very nature of modern growth. This is the debate about the “Great Enrichment” (McCloskey Reference McCloskey2016a). Why was growth limited in ancient societies? And how have modern societies been able to achieve such astonishing growth rates? Here, standard approaches to the Industrial Revolution are of little use (Clark Reference Clark2007; McCloskey Reference McCloskey2016a; Mokyr Reference Mokyr2016). Even if these approaches can account for the temporary superiority of England in terms of institutions or human capital, they do not explain the discontinuity created by the Industrial Revolution, nor its magnitude. As Clark puts it: “What makes the Industrial Revolution so difficult to understand is the need to comprehend why – despite huge variation in the customs, mores, and institutions of preindustrial societies – none of them managed to sustain even moderate rates of productivity growth, by modern standards, over any significant time period. What was different about all preindustrial societies that generated such low and faltering rates of efficiency growth?” (Clark Reference Clark2007, p. 207)

Recent work in economic history points to the central role of technology in modern growth (Mokyr Reference Mokyr2009b; Reference Mokyr2016). And indeed, what made England richer was a wave of inventions and innovations in the clothing industry, the mining industry, and so on. Newcomen and Watt invented the steam engine; Arkwright, Hargreaves, Crompton, and Cartwright revolutionized the textile sector; Darby and Cort found new ways to produce iron and more. To take but one example of the scale of these technological improvements, the amount of work needed to turn a pound of cotton into cloth went from the equivalent of 18 man-hours in the 1760s to 1.5 man-hours in the 1860s, an 1,200% increase in productivity. As Joel Mokyr (Reference Mokyr2009b, p. 5) writes: “The best definition of the Industrial Revolution is the set of events that placed technology in the position of the main engine of economic change.”

One possible explanation for a high rate of innovation is the presence of well-functioning institutions (Acemoglu & Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012; North Reference North1991). Since the work of Douglas North, it has been argued that the rate of innovation increased in England in the eighteenth century because institutions created a better incentive structure for potential innovators. According to the institutionalist approach, the English crown was more constrained by institutional rules and less likely to infringe on the property rights of innovators than its European counterparts (North & Weingast Reference North and Weingast1989). However, although the institutionalist approach may explain the exceptional political climate of eighteenth-century Britain, it is at odds with the history of the Industrial Revolution. The British institutions of the eighteenth century actually offered little to no incentive to innovate. The last significant reform of the patent system was in 1689, more than a hundred years before efficiency gains became common (Clark Reference Clark2007), and, throughout the eighteenth century, innovators rarely made use of the patent system to defend their property rights (Mokyr Reference Mokyr2009a). The invention of the flying shuttle is a case in point: “The flying shuttle was technically illegal because it saved labour, the patent was immediately pirated by competitors to little avail, and Kay was forced to move to France, hounded out of the country by angry weavers who threatened his property and even his life. Kay faced no special incentives – he even innovated despite some formidable social and legal barriers” (Howes Reference Howes2016b).

One of the most puzzling facts about the Industrial Revolution is that many of the innovations did not require any scientific or technological input, and could actually have been made much earlier. Paul's carding machine, Arkwright's water frame, and Cartwright's improvements to textile machinery were not “rocket science” (Allen Reference Allen2009b) and would not have “puzzled Archimedes” (Mokyr Reference Mokyr2009b). Thus, the puzzle of the Industrial Revolution: If these innovations were so simple, why then did it take so long for many of them to emerge? As McCloskey puts it: “If the spinning jenny was such a swell idea in 1764 C.E., why was it not in 1264, or 264, or for that matter in 1264 B.C.E.?” (McCloskey Reference McCloskey2010, p. 377).

1.2. A Life History Theory approach to the puzzle of modern growth

Following a growing number of economic historians (Clark Reference Clark2007; McCloskey Reference McCloskey2006; Reference McCloskey2010; Reference McCloskey2016a; Mokyr Reference Mokyr2009b; Reference Mokyr2016), this paper proposes that the most important change that occurred during the Industrial Revolution may not have been in the incentive structure faced by innovators (e.g., better property rights, higher wages, larger markets), but in the preferences of individuals. Specifically, the sustained acceleration of the rate of innovation might partly be a result of a switch from a “scarcity mindset” to an “affluence mindset,” which rendered people more patient, optimistic, and curious.

Why might there have been such a change in individual preferences at this time, in this place? In many parts of Eurasia, living standards slowly increased during Antiquity and the Middle Ages because of the gradual accumulation of technological knowledge in the industrial sector (Dutta et al. Reference Dutta, Levine, Papageorge and Wu2018). England, in particular, achieved an unprecedented level of affluence in the eighteenth century (Broadberry et al. Reference Broadberry, Campbell, Klein, Overton and van Leeuwen2015). English people at the time (in particular, members of the upper-middle class) were richer, healthier, taller, better nourished, better equipped, and better educated than individuals in any previous society (Allen Reference Allen2001; Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Mokyr and Ó Gráda2014). I hypothesize that this increase in living standards may have triggered a limited and gradual modification in neurocognitive processes such as time discounting, optimism, reward orientation, and trust. This hypothesis is based on Life History Theory (LHT), a branch of evolutionary biology that studies how organisms allocate their resources to different activities (development, reproduction, body maintenance, etc.) across the life span (Roff Reference Roff1993; Stearns Reference Stearns1992). The basic idea of LHT is that organisms have a finite budget of resources and they must optimize the use of this budget across the life span. To do so, organisms must make trade-offs between different activities (growth vs. reproduction) and invest, at each moment in their lives, in the activity with the greatest marginal reproductive benefit. For example, if their risk of dying is high and their time horizon short, they should not invest in growing a large body or in developing a strong immune system but start reproducing as soon as possible (Charnov Reference Charnov1991; Promislow & Harvey Reference Promislow and Harvey1990). LHT thus offers an explanation of why species living in different environments with different levels of resources may display drastically different physiological and behavioral traits (e.g., shorter or longer life spans, smaller or bigger bodies, lower or higher levels of investment in offspring).

Although Life History Theory was first developed to account for differences in life history across species (e.g., between species with shorter and those with longer life spans), it has been extended to account for differences in life history within the same species (Stearns & Koella Reference Stearns and Koella1986). In humans, recent empirical works has demonstrated that individuals tend to adopt different “life strategies” depending on their environment (Ellis et al. Reference Ellis, Figueredo, Brumbach and Schlomer2009; Figueredo et al. Reference Figueredo, Vásquez, Brumbach, Schneider, Sefcek, Tal, Hill, Wenner and Jacobs2006; Frankenhuis et al. Reference Frankenhuis, Panchanathan and Nettle2016; Pepper & Nettle Reference Pepper and Nettle2017). In scarce environments, humans tend to grow faster, reach the age of sexual maturity earlier, reproduce earlier, and have more children. By contrast, in more favorable environments, humans adopt a different strategy, reaching maturity later, debuting sexuality later, and having a smaller number of children. These opposite “life strategies” are often referred to as “fast” and “slow” strategies (also called ‘pace-of-life syndromes’ or ‘behavioral constellation’) (see Fig. 1), although it should be emphasized that time preferences are one among many other preferences involved in life history strategies. Crucially, the environment also affects behavior and cognitive level: Individuals growing and living in scarce environments tend to be more violent (McCullough et al. Reference McCullough, Pedersen, Schroder, Tabak and Carver2013), more mistrustful of others (Petersen & Aarøe Reference Petersen and Aarøe2015), more materialistic (Carver et al. Reference Carver, Johnson, McCullough, Forster and Joormann2014), more likely to vote for an authoritarian leader (Safra et al. Reference Safra, Algan, Tecu, Grèzes, Baumard and Chevallier2017), and more intolerant of deviance (Murray et al. Reference Murray, Trudeau and Schaller2011). Crucially, all of these traits are intercorrelated and indeed appear to be coordinated by a single underlying life history variable (Brumbach et al. Reference Brumbach, Figueredo and Ellis2009; Mell et al. Reference Mell, Safra, Algan, Baumard and Chevallier2018).

Figure 1. Fast and slow strategies. Adapted from Griskevicius (Reference Griskevicius, Ackerman, Cantú, Delton, Robertson, Simpson, Thompson and Tybur2013).

In this paper, I apply insights and results from work in LHT to explain the puzzle of the Great Enrichment. To innovate is inherently costly. It requires time and resources, more so as technological complexity increases (Bloom et al. Reference Bloom, Jones, Van Reenen and Webb2017; Gordon Reference Gordon2012; Jones Reference Jones2009; Mesoudi Reference Mesoudi2011). I argue that it is only in sufficiently affluent and stable environments that humans can afford to invest in activities whose benefits are delayed, unpredictable, or (at least initially) moderate. If this is true, then rising living standards are likely to influence the rate of technological innovation. As more people are able to satisfy their basic needs, they will become more patient, more optimistic, and more interested in exploring new technological solutions or in tweaking existing ones (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2. The causal role of the life history switch.

In what follows, I first present LHT in more detail and explain why becoming more exploratory and patient when resources are more abundant is adaptive (sect. 2). I then review the empirical evidence regarding the effect of affluence on human behavior (sect. 3). In particular, I show that resources can impact the expression of a range of psychological traits related to innovation: time discounting, self-control, optimism, cognitive exploration, and social trust. Finally, I review the evidence demonstrating the unprecedented level of affluence in eighteenth-century England (sect. 4) and discuss whether the English indeed displayed a “slow” psychology (in LHT terms) outside the domains related to innovation (sect. 5). I conclude the paper by discussing the points of convergence and divergence between this approach and other work emphasizing psychological mechanisms, as well as the potential of such a mechanism to explain the broader “civilizing process” (declining violence, declining impulsivity, increasing openness, increasing social trust; Elias Reference Elias1982).

2. Life History Theory and the variability of innovativeness

2.1. The mechanism of adaptive plasticity

One common assumption in the social sciences is that biological mechanisms are fixed and, thus, cannot change. Historical change would thus require exogenous forces such as new ideas or new institutions. But this assumption is based on a common misconception about natural selection, which is wrongly thought to favor mechanisms that produce uniform and unchanging behaviors. In fact, most evolved mechanisms, physiological or psychological, actually come with a certain level of flexibility in response to local contexts. When the environment changes at a rate that is too high relative to generation time, natural selection does not have enough time to produce genetic adaptations for each and every environmental state (Moran Reference Moran1992; Stearns & Koella Reference Stearns and Koella1986). In this case, natural selection instead favors a genotype that can react flexibly to the environment. Individuals are characterized not by a single phenotypic profile (organs, behaviors), but by what is called a “reaction norm”: a range of phenotypes expressed conditionally depending on the current state of the environment. The expression of a variety of locally adapted phenotypes from the same genotype is called adaptive plasticity.

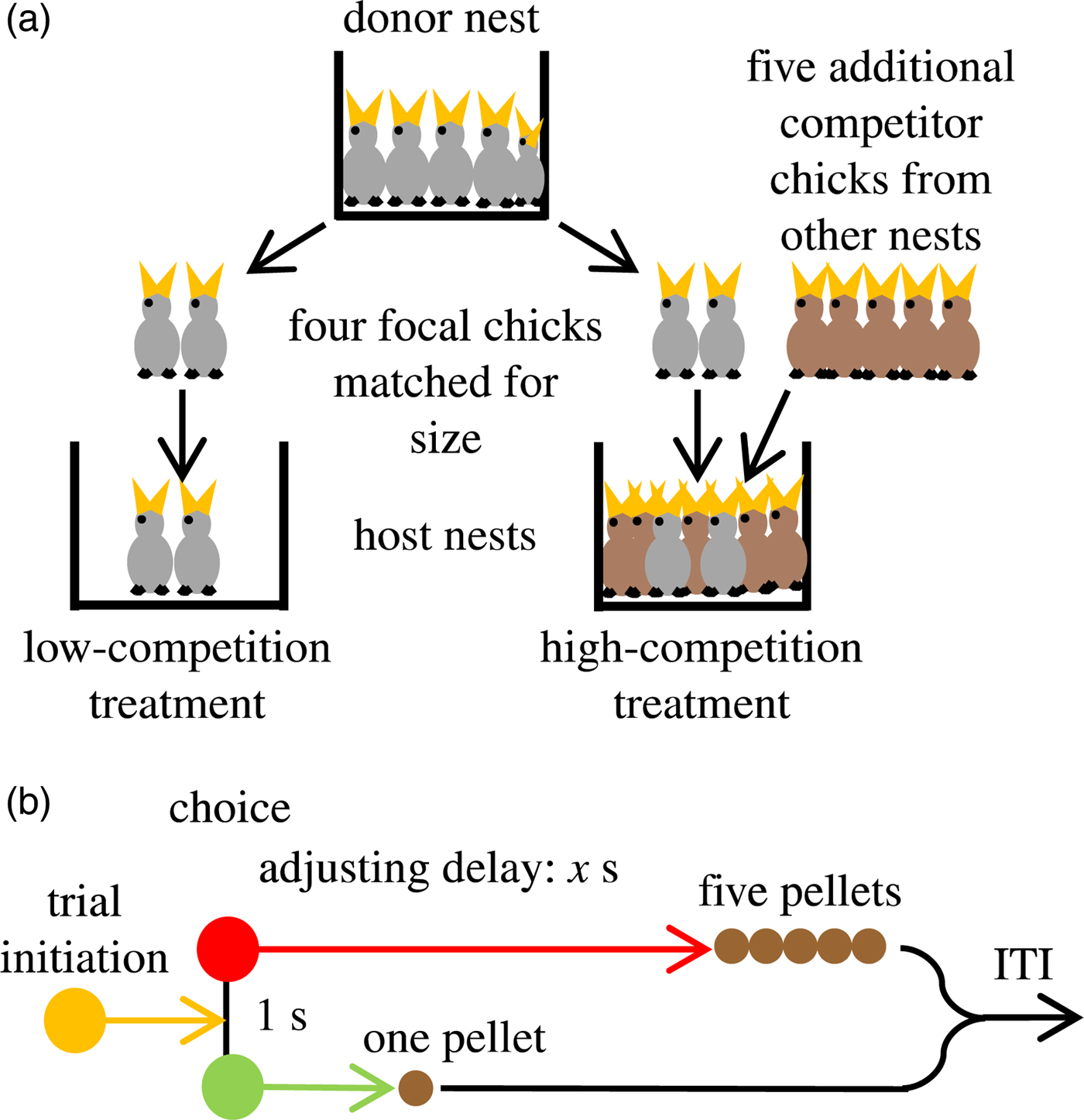

To take but one example, Bateson et al. (Reference Bateson, Brilot, Gillespie, Monaghan and Nettle2015) tested the impact of scarcity on a population of starlings. Pairs of chicks were placed in nests where they faced either a high or low level of competition for 12 days as juveniles (Fig. 2a), after which they were all transferred to the laboratory for hand-rearing under uniform conditions. As expected, this manipulation affected the birds’ telomeres, a biomarker of poor biological state and life expectancy. Birds in the high-competition condition traded their investment in growth and body maintenance for increased competitiveness. Impulsivity was measured when the birds were fully grown (6–12 months later) (Fig. 2b). Birds with greater developmental telomere attrition (those that reacted the most to the high-competition treatment) had a stronger preference for smaller but more immediate food rewards than birds with less developmental attrition or longer telomeres. A subsequent study from the same team found that biological aging in starlings is associated with higher levels of risk aversion (Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Nettle, Reichert, Bedford, Monaghan and Bateson2018).

Bateson et al.’s experiment perfectly illustrates the potential of adaptive plasticity and LHT, in particular, to help us understand historical changes. When impulsivity was measured, the birds in the two groups were living the same life: They were fed the same way, lived in the same aviary, and were being taken care of by the same people. They also had the same kinds of social interactions with the same conspecifics. In other words, they were facing the same incentive structure with the same information about their environment. And yet their preferences regarding time differed according to how much they had been stressed when they were juveniles. Likewise, behavioral changes can occur without any change in political institutions, religious beliefs, or useful knowledge. They can result simply from change in adaptive calibrations.

2.2. Life history plasticity in humans

In the past decade, a range of studies has shown that human plasticity obeys the same evolutionary logic employed by other animals (see Fig. 1). When the environment deteriorates, individuals tend to accelerate their life history in every domain of life: reproductive investments, somatic investment, and social investment. In this section, I briefly review this literature.

2.2.1. Somatic investment

It is well documented that individuals growing up in a harsh environment are less likely to invest in their health. People in a lower socioeconomic position smoke more, exercise less, have a poorer diet, comply less well with therapy, use medical services less, and ignore health and safety advice more than their more-affluent peers (Nettle Reference Nettle2011; Smith & Egger Reference Smith and Egger1993; Stringhini et al. Reference Stringhini, Sabia, Shipley, Brunner, Nabi, Kivimaki and Singh-Manoux2010). The evolutionary reason is that health behavior competes for individuals’ time and energy with other activities that contribute to their fitness. When resources are low, individuals invest less in their immune systems and in protecting their bodies (Nettle Reference Nettle2010b; Nettle et al. Reference Nettle, Frankenhuis and Rickard2013) (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3. (a) Brood-size manipulation. The diagram shows the creation of a single family of four focal chicks. (b) Intertemporal choice task. One colored key (here, green) was assigned to the smaller sooner option (a 1-s delay to obtain one 45-mg pellet), and the other color (here, red) was assigned to the larger later option (a longer x-s delay to obtain five 45-mg pellets) (Bateson et al. Reference Bateson, Brilot, Gillespie, Monaghan and Nettle2015).

In line with this reasoning, Nettle (Reference Nettle2014) showed that a lower level of parental support during childhood is associated with accelerated deterioration of health as well as increased levels of the C-reactive protein (an inflammatory biomarker of the somatic damage caused by social and environmental stressors). These associations are robust, persisting after adult socioeconomic position has been controlled for, and do not appear to be a consequence of an accelerated reproductive strategy, smoking, or body mass index. Similarly, Mell et al. (Reference Mell, Safra, Algan, Baumard and Chevallier2018) showed that childhood poverty is associated with lower somatic investment (e.g., effort in looking after health) in a representative sample of French individuals. Crucially, Mell et al. showed that lower investments in health are associated with “faster” behaviors in the reproductive domain, supporting the existence of an overarching general life history strategy explaining both reproductive and health choices.

2.2.2. Reproductive investments

The basic prediction of LHT concerning reproduction is straightforward. As the level of resources decreases, investment in self-repair and bodily systems decreases (Nettle Reference Nettle2010b; Nettle et al. Reference Nettle, Frankenhuis and Rickard2013). This, in turn, accelerates the speed of aging and lowers the optimal age for initiating reproductive effort. These predictions have been confirmed by a large number of studies: Humans living in harsh environments reach sexual maturity earlier (Brumbach et al. Reference Brumbach, Figueredo and Ellis2009; Ellis Reference Ellis2004), reproduce earlier (Belsky et al. Reference Belsky, Steinberg, Houts and Halpern-Felsher2010; Ellis Reference Ellis2004), and have more children (Guégan et al. Reference Guégan, Thomas, Hochberg, de Meeûs and Renaud2001). Further studies have shown that people living in harsh environments also tend to invest less in their children. For example, using data from the British Millennium Cohort Study (N = 8,660 families), Nettle (Reference Nettle2010a) showed that in harsher neighborhoods, breastfeeding duration is shorter, co-residence of a father figure is less common, and contact with maternal grandmothers is less frequent. Similar relations between environmental harshness and parental investment have been observed cross-culturally, with maternal care being inversely associated with famine, warfare, and high levels of pathogens (Quinlan Reference Quinlan2007; Quinlan & Quinlan Reference Quinlan and Quinlan2007).

2.3. Life history and attitude toward innovation

In the preceding sections, I reviewed the core domains studied by behavioral ecologists and evolutionary biologists working on LHT. However, in the last decades, scientists have started to apply the insights of LHT to a range of psychological domains that are likely to affect the rate of innovation.

2.3.1. Time discounting

Innovation takes time to yield benefits. Even where an individual is simply tweaking and adapting an existing invention (as was often the case of English innovators in the eighteenth century), individuals need to be ready to waste years trying to improve a device without knowing whether they will ever succeed. In his British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective, Allen (Reference Allen2009b) discusses in detail the issues involved in inventing mechanical spinning (e.g., how much the speed should increase from one set of rollers to the next, how to arrange the gears to connect the main power shaft to the rollers and coordinate their movements, and the spacing between rollers). His discussion emphasizes that the most difficult part was not to come up with the idea of the roller, but to make the roller work in this application. Wyatt and Paul had spent decades on this problem but never succeeded, and it took several years for Arkwright and the clockmakers to find their solution. As Allen points out, many of the innovations of the eighteenth century involved what we would today call an “R&D program,” in which the innovators constructed prototypes and performed careful experimentation.

How should time discounting be affected by increased living standards? From an LHT perspective, individuals living in a harsh environment cannot allocate resources to activities that have large but delayed benefits, because they cannot afford to wait (Houston & McNamara Reference Houston and McNamara1999). Thus, in a harsh environment, individuals are more likely to postpone investing in innovation and to focus on more pressing needs. By contrast, individuals surrounded by abundance can afford to invest in long-term endeavors such as building prototypes, conducting careful experiments, and trying out new models. Note that time discounting is a very abstract construct. People's time discounting will be visible not only in time-discounting tasks (i.e., $10 now rather than $20 later), but also in tests of psychological characteristics such as self-control and impulsivity. People living in affluent environments should show higher levels of self-control in tasks such as the marshmallow test or on questionnaires concerning impulsive actions.

2.3.2. Optimism

English innovators were particularly optimistic. As Howes (Reference Howes2016a) writes, they had an “improving mentality,” seeing room for improvement everywhere. Henry Dircks, who improved steam engines and designed optical illusions, expressed the new mentality thus: “No work of art appears perfect to an enterprising mind. However simple its purpose, it may possibly be made lighter, stronger, more efficacious, or be done away with altogether. The man whose mind is thus constituted becomes an Inventor” (Dircks 1867, p. 9, cited in Howes Reference Howes2016a, p. 8).

How should optimism be affected by increased living standards? LHT modeling, inspired by optimal foraging theory (Stephens Reference Stephens1981), suggests that individuals with low resources should have a high threshold for responding to reward cues because they have few resources to invest. As a result, they should be reluctant to initiate reward-approach behaviors (Nettle Reference Nettle2009a; Nettle & Bateson Reference Nettle and Bateson2012). At the subjective level, they should feel that taking action will not be pleasurable, that they probably will not succeed, and that they do not have the energy to try. By contrast, individuals with high resources should be ready to initiate reward-approach behavior when given only minimal cues that a reward may be available. In humans, this state is associated with subjective feelings of optimism, with attentional biases toward reward-related stimuli and with willingness to try out novel reward-oriented strategies.

2.3.3. Materialism and intrinsic motivation

Edison famously observed that “invention is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration” (cited in Allen Reference Allen2009b, p. 149). In other words, innovation requires a high level of discipline and conscientiousness. Innovators need to focus on the many little challenges they face rather than on the big material rewards associated with developing a successful innovation. Thus, they need to be intrinsically motivated by the process of inventing, tweaking, and adapting existing technologies.

How should materialism and intrinsic motivation be affected by increased living standards? Individuals living in harsh environments are unlikely to invest in activities with a moderate return on investment because other, more vital activities need more urgently to be performed (Kenrick et al. Reference Kenrick, Griskevicius, Neuberg and Schaller2010). It is only when they have fulfilled their vital and basic needs (food, self-protection, affiliation, social status) that they can afford to pursue activities such as free exploration. The predictions of LHT are somewhat well known, as they correspond to the “pyramid of needs” described by Maslow in the 1940s (Kenrick et al. Reference Kenrick, Griskevicius, Neuberg and Schaller2010). What LHT does is explain why humans’ needs are prioritized as they are. Individuals have all kinds of needs whose return on investment depends on the individual's state. When an individual is poor or young, some needs have a very high return on investment (food, self-protection, affiliation), and others have lower returns on investment (exploration: what Maslow lumped together with other activities under the heading of “self-actualization”). By contrast, when the same individual has fulfilled these needs (growing a body, making some friends), their return on investment diminishes (the marginal benefit of having an extra friend depends on the number of friends). Other activities, with a moderate return on investment, then start to be more advantageous. As a result, these activities become a priority.

2.3.4. Cognitive investment and cognitive exploration

The history of technology reveals that most macro-innovations came from outside of the field of the industry concerned (Allen Reference Allen2009b, p. 141). They required innovators to ignore existing technological traditions and show little reverence for existing solutions. This was indeed the state of mind of many eighteenth-century innovators who were no experts in their industry and who discarded existing tradition. For example, Henry Bessemer (steelmaking process) explained that he was very aware of his ignorance and that he thought of it as an advantage:

My knowledge of iron metallurgy was at the time very limited … but this was in one sense an advantage to me, for I had nothing to unlearn. My mind was open and free to receive any new impressions, without having to struggle against the bias which a lifelong practice of routine operations cannot fail more or less to create. (cited by Howes Reference Howes2016b, p. 10)

What are the costs and benefits of individual and social learning? In behavioral ecology, social information is usually regarded as cheaper because individuals can piggyback on others’ knowledge, but also as less accurate because individuals may not be in the same situation as others (Boyd & Richerson Reference Boyd and Richerson1985; Laland & Williams Reference Laland and Williams1998; Rieucau & Giraldeau Reference Rieucau and Giraldeau2011; Webster & Hart Reference Webster and Hart2006). There is thus a trade-off between cost and accuracy. When resources are abundant, individuals should favor accuracy, be interested in cognitive investment and cognitive exploration, and thus be curious, independent, and open-minded. On the contrary, when resources are low, individuals should not waste more resources in exploring their environment; they should rather be conservative and conformist (Jacquet et al. Reference Jacquet, Safra, Wyart, Baumard and Chevallier2018).

2.3.5. Social trust

Innovation is likely to be favored by social trust, which promotes open discussions and furthers the circulation of innovation (Mokyr Reference Mokyr2016). As McCloskey notes, one important difference between Renaissance Florence and Early Modern Britain is that “Leonardo da Vinci in 1519 concealed his engineering dreams in secret writing,” whereas “in 1825 James Watt of steam-engine fame was to have a statue set up in Westminster Abbey” (McCloskey Reference McCloskey2016b, p. XXXIV). In line with this idea, Howes (Reference Howes2016a) showed that British innovators were almost all committed in some way to advancing, proselytizing, or disseminating further improvement by contributing to societies, authoring books, funding schools, or abstaining from patenting their inventions. Eighty-three percent shared innovation in some way; only 12% tried to stifle it, and only 5% are known to have been secretive.

From an LHT perspective, cooperation can be seen as an investment. Individuals invest their time and resources in collective action in the hope that these activities will produce bigger benefits than solitary work will (Baumard et al. Reference Baumard, André and Sperber2013; West et al. Reference West, Griffin and Gardner2007). From this perspective, cooperation is intrinsically forward-looking. It is thus expected that individuals should invest less in cooperation, and therefore be less trustful, when they cannot afford to lose their investment or when they discount time at too high a rate to wait for their partners to reciprocate.

2.4. Why innovation is not always the best strategy

LHT runs against the common sense according to which “necessity is the mother of invention.” Common sense suggests that individuals in poverty should innovate more or show greater self-control, because they are in a situation where they would benefit more from innovating and restraining their impulses. And yet, clearly, innovation is more frequent in more affluent societies, those that already perform better. Even in nonhuman animals such as birds and monkeys, a growing body of data suggests that individuals are more innovative in captivity than in the wild (Forss et al. Reference Forss, Schuppli, Haiden, Zweifel and van Schaik2015; Haslam Reference Haslam2013; van Schaik et al. Reference van Schaik, Burkart, Damerius, Forss, Koops, van Noordwijk and Schuppli2016).

The explanation for this paradox is that the opportunity costs of innovation are higher in poorer societies. Individuals living in poverty actually have more pressing needs than the need to innovate: they must find food for tomorrow, rebuild their house before the next rain, watch out for potential dangers, and so on. As counterintuitive as it may be, medieval laborers had better things to do than improve the productivity of their tools. If these laborers had invested in innovation, their fields might have been more productive in the long run. But the time spent on innovation, or the risks associated with tweaking traditional techniques, could also have led to the ruin of their families. Innovation is a luxury that few could afford in pre-industrial societies.

So, a lack of innovativeness should not be seen as suboptimal behavior. Exploration and exploitation are two different strategies with different advantages and drawbacks. Exploration can bring greater rewards in the form of profitable innovations, but it is often more risky in the sense that it requires time and resources and may not automatically lead to successful innovation. By contrast, exploitation brings lower rewards, but these rewards are safer because they require a lower level of investment and are more certain. Consequently, the potential benefits of exploration and exploitation are context-dependent. Exploration is a better strategy under conditions of relative safety, in which individuals can afford to divert some resources and even lose them in the pursuit of an innovation. Exploitation is a better strategy under harsh conditions, where any error can lead to starvation and death.

Importantly, this implies that individuals living in scarcity will not show impaired cognitive or behavioral performance. Instead, according to evolutionary theory, the preferences and behaviors of individuals should be contextually appropriate, and people living in scarcity are simply better adapted to that type of environment. Recall, here, that the stressed starlings were impulsive but not cognitively impaired. In line with this idea, individuals living in an environment of scarcity perform better at tasks related to actual challenges created by scarcity. Recent studies indicate that, compared with individuals living in affluent environments, people living in scarcity exhibit improved detection, learning, and memory in tasks involving stimuli that are ecologically relevant to them (e.g., dangers: Dang et al. Reference Dang, Xiao, Zhang, Liu, Jiang and Mao2016; Frankenhuis & de Weerth Reference Frankenhuis and de Weerth2013; Frankenhuis et al. Reference Frankenhuis, Panchanathan and Nettle2016; Mittal et al. Reference Mittal, Griskevicius, Simpson, Sung and Young2015).

3. The impact of affluence on innovativeness

In section 2, I reviewed the theoretical evidence in favor of the view that an increase in resources is likely to affect a range of attitudes in a way that is conducive to innovation. In this section, I review the empirical evidence in favor of this view. In recent years, a number of scholars have demonstrated that poverty makes individuals more present-oriented, more loss-averse, less exploratory, and more conformist. In behavioral economics, these are often referred under the term “psychology of poverty” (Haushofer & Fehr Reference Haushofer and Fehr2014) or the “scarcity mindset” (Mani et al. Reference Mani, Mullainathan, Shafir and Zhao2013; Mullainathan & Shafir Reference Mullainathan and Shafir2013). In this section, I focus on the other side of the coin, the “psychology of affluence” or the “abundance mindset,” that is, evidence that affluence makes people more future-oriented, less loss-averse, more exploratory, and less conformist.

3.1. Time discounting, self-control, and impulsivity

Affluence has a substantial impact on time discounting. In a recent study, Haushofer and Fehr reviewed the effect of poverty on time discounting and showed that the level of resources has a strong effect on people's relationship to the future (Haushofer & Fehr Reference Haushofer and Fehr2014). For example, the discount rates of poor U.S. households are substantially higher than those of rich households (Lawrance Reference Lawrance1991). Likewise, studies of Ethiopian farm households (Yesuf & Bluffstone Reference Yesuf and Bluffstone2008) and a South Indian sample (Pender Reference Pender1996) have found that poverty is significantly associated with higher (behaviorally measured) discount rates.

People living in harsh environments where unemployment and violence are high also have less self-control and are more impulsive. Carver et al. (Reference Carver, Johnson, McCullough, Forster and Joormann2014) studied the impact of harshness during childhood on self-control in adults. They used validated psychometric scales assessing self-control, urgency, and perseverance. Their results show a consistent association between childhood harshness and lack of self-control. Similarly, Duckworth et al. (Reference Duckworth, Kim and Tsukayama2013) demonstrated that negative life events in the past year (events such as getting fired or laid off from job, “major change in emotional closeness of family,” or divorce) were associated with diminished self-control in children and adolescents. In line with these results, poverty (i.e., inadequate housing, economic insufficiency) is associated with higher resting levels of salivary cortisol during the first four years of life which, in turn, is associated with worse performance on executive function tasks (Blair & Raver Reference Blair and Raver2012; Blair et al. Reference Blair, Granger, Willoughby, Mills-Koonce, Cox, Greenberg, Kivlighan and Fortunato2011).

3.2. Optimism and feeling of internal control

Studies with large cohorts have demonstrated a strong socioeconomic status (SES) gradient in optimism and pessimism, with higher SES being associated with higher optimism scores and lower pessimism scores (Boehm et al. Reference Boehm, Chen, Williams, Ryff and Kubzansky2015; Heinonen et al. Reference Heinonen, Räikkönen, Matthews, Scheier, Raitakari, Pulkki and Keltikangas-Järvinen2006; Robb et al. Reference Robb, Simon and Wardle2009). Importantly, in line with the idea that part of life history is calibrated early in childhood, childhood family SES has been found to be associated with overall optimism and pessimism component scores, even after controlling statistically for SES in adulthood (Heinonen et al. Reference Heinonen, Räikkönen, Matthews, Scheier, Raitakari, Pulkki and Keltikangas-Järvinen2006). A number of other psychological variables are related to optimism, such as “locus of control” and “self-efficacy,” which measure people's confidence in their ability to control their environment. To test the association between poverty and locus of control, Haushofer (Reference Haushofer2013) used questions from the World Values Survey such as: “Some people believe that individuals can decide their own destiny, while others think that it is impossible to escape a predetermined fate. Please tell me which comes closest to your view on this scale on which 1 means ‘everything in life is determined by fate,’ and 10 means that ‘people shape their fate themselves.’” Both within and across countries, affluence is associated with a higher feeling of internal control. This study replicates previous studies in a diversity of populations (e.g., Kiecolt et al. Reference Kiecolt, Hughes and Keith2009; Lundberg et al. Reference Lundberg, Bobak, Malyutina, Kristenson and Pikhart2007; Poortinga et al. Reference Poortinga, Dunstan and Fone2008).

3.3. Materialism and intrinsic motivation

Materialism is typically understood as “the belief that it is important to pursue the culturally sanctioned goals of attaining financial success, having nice possessions, having the right image (produced, in large part, through consumer goods), and having a high status (defined mostly by the size of one's pocketbook and the scope of one's possessions)” (Kasser et al. Reference Kasser, Ryan, Couchman, Sheldon, Kasser and Kanner2004). Using longitudinal data on American twelfth graders between 1976 and 2007 (N = 355,296), Twenge and Kasser (Reference Twenge and Kasser2013) measured materialism (through questions measuring young people's attitudes on “how important it is ‘to have lots of money’” or to have “a job which provides you with a chance to earn a good deal of money”). In line with LHT, they showed that societal instability was associated with higher levels of materialism (for similar results, see Briers et al. Reference Briers, Pandelaere, Dewitte and Warlop2006; Cohen & Cohen Reference Cohen and Cohen1996; Kasser et al. Reference Kasser, Ryan, Zax and Sameroff1995; Sheldon & Kasser Reference Sheldon and Kasser2008). Carver et al. (Reference Carver, Johnson, McCullough, Forster and Joormann2014) studied another kind of extrinsic goal, namely, social success. Using a scale measuring hubristic pride, popular fame, and financial success, they showed that childhood adversity is associated with a greater tendency to set implausibly high goals (“I will be famous,” “I will run a Fortune 500 company”). Finally, sensation seeking is another behavioral construct that is related to intrinsic motivation. Carver et al. (Reference Carver, Johnson, McCullough, Forster and Joormann2014) showed that childhood adversity is associated with higher levels of sensation seeking, as well as greater consumption of illicit drugs and alcohol (Droomers et al. Reference Droomers, Schrijvers, Stronks, van de Mheen and Mackenbach1999; Legleye et al. Reference Legleye, Janssen, Beck, Chau and Khlat2011).

At the other end of the spectrum, affluence has been shown to positively impact intrinsic motivation: As people get richer, they are less interested in immediate material rewards. Using the World Values Survey, Haushofer (Reference Haushofer2013) showed a consistent association between intrinsic motivation and income, both across and within countries (Haushofer approximated intrinsic motivation with two questions: agreement with the statements “Working for a living is a necessity; I wouldn't work if I didn't have to” and “I do the best I can regardless of pay” (Haushofer Reference Haushofer2013). Affluence has also been found to affect personality consciousness (Akee et al. Reference Akee, Copeland, Costello and Simeonova2018). Using the Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth, Akee et al. (Reference Akee, Copeland, Costello and Simeonova2018) demonstrated that cash transfers increased conscientiousness and reduced drug consumption independently of income or education.

3.4. Cognitive investment and cognitive exploration

Individuals with low resources should invest less in cognitive exploration and information gathering, and, consequently, they should rely more on cheaper sources of information such as others’ opinions (Nettle Reference Nettle2019). Jacquet et al. (Reference Jacquet, Safra, Wyart, Baumard and Chevallier2018) studied the calibration of cognitive investment in information gathering through variables such as childhood scarcity and childhood unpredictability (assessed through agreement with statements such as “Things were often chaotic in my house” and “People often moved in and out of my house on a pretty random basis”). The results indicated that, independent of their current situation, participants who experienced scarcity and unpredictability during childhood are more likely to follow the opinion of the group in a standard face evaluation task.

Affluence should also impact cognitive investment in more abstract tasks. In a series of experiments, Mani et al. (Reference Mani, Mullainathan, Shafir and Zhao2013) studied the impact of scarcity on individuals’ performance in Raven's Progressive Matrices and in a spatial compatibility task. They induced richer and poorer participants to think about everyday financial demands. They hypothesized that for the rich, these little financial demands would be of little consequence, whereas for the poor, these demands would trigger persistent and distracting concerns. In line with their hypotheses, poor participants performed worse. Mani et al. (Reference Mani, Mullainathan, Shafir and Zhao2013) also conducted a field study that used a quasi-experimental variation in actual wealth. Indian sugarcane farmers receive income annually at harvest time and find it hard to smooth their consumption. As a result, they experience cycles of poverty: they are poorer before harvest and richer afterward. (On average, farmers had 1.97 more loans before harvest than they did afterward. They were also more likely to answer “Yes” to the question, “Did you have trouble coping with ordinary bills in the last fifteen days?” before harvest than after). This allowed the researchers to compare the cognitive capacities of the same farmer in poorer (preharvest) versus richer (postharvest) circumstances. Again, the farmers’ performance was worse in times of scarcity.

3.5. Trust

Cooperative behaviors have been found to vary with the harshness of the environment (Holland et al. Reference Holland, Silva and Mace2012; Nettle et al. Reference Nettle, Colléony and Cockerill2011; Silva & Mace Reference Silva and Mace2014; Reference Silva and Mace2015; but see Wu et al. Reference Wu, Balliet, Tybur, Arai, Van Lange and Yamagishi2017). Independent of their current level of resources, people who grew up in a deprived environment are more likely to defect (McCullough et al. Reference McCullough, Pedersen, Schroder, Tabak and Carver2013), more likely to steal from others (Schroeder et al. Reference Schroeder, Pepper and Nettle2014), and less likely to forgive others (McCullough et al. Reference McCullough, Pedersen, Schroder, Tabak and Carver2013; Pedersen et al. Reference Pedersen, Forster and McCullough2014), trust them (Mell et al. Reference Mell, Safra, Algan, Baumard and Chevallier2018), and punish cheaters (Schroeder et al. Reference Schroeder, Pepper and Nettle2014). Importantly, life history theory predicts that cooperative behaviors should be part of a more general life history strategy. In line with this prediction, Petersen and Aarøe (Reference Petersen and Aarøe2015) report an association between low birth weight, low self-control in childhood, and lower social trust in adulthood (on the early calibration of prosociality, see also Benenson et al. Reference Benenson, Pascoe and Radmore2007; Safra et al. Reference Safra, Tecu, Lambert, Sheskin, Baumard and Chevallier2016). Similarly, lab studies show a correlation between high time discounting – an indicator of a faster life strategy – and low levels of cooperation in economic games (Curry et al. Reference Curry, Price and Price2008; Espín et al. Reference Espín, Brañas-Garza, Herrmann and Gamella2012; Harris & Madden Reference Harris and Madden2002; Kocher et al. Reference Kocher, Myrseth, Martinsson and Wollbrant2013; Kortenkamp & Moore Reference Kortenkamp and Moore2006). Finally, Mell et al. (Reference Mell, Safra, Algan, Baumard and Chevallier2018) demonstrated that the impact of environmental harshness on social trust is mediated by a latent psychological construct corresponding to life history strategy.

3.6. Assessing the causal impact of affluence

Most studies presented in this section are correlational, and it could be that the association between affluence and a slow life history is driven by other factors (notably genetics). Similarly, experimental studies may reveal real but fleeting effects on human behaviors. However, in recent years an increasing number of studies in econometrics have aimed to assess the causal impact of the environment using natural experiments. There is now a consensus that exogeneous shocks in utero or during early childhood (disease, famine, malnutrition, pollution, war) have dramatic, long-lasting effects on physical and mental health, height, IQ, and income (for a review, see Currie & Vogl Reference Currie and Vogl2013). A growing number of studies show similar effects on psychological traits such as risk attitudes (Moya Reference Moya2018), materialism (Kesternich et al. Reference Kesternich, Siflinger, Smith and Winter2015), and prosociality (Cecchi & Duchoslav Reference Cecchi and Duchoslav2018; Gangadharan et al. Reference Gangadharan, Islam, Ouch and Wang2017). The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth (cited in sect. 3.3) is a case in point. This study takes advantage of the opening of a casino in the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians tribal reservation. Following the opening of the casino, permanent transfers were provided to all adult Cherokees (but not to non-Cherokees living in the same area), regardless of employment conditions, marital status, presence of young children in the household, or residence on the reservation. Comparing Native American children with non-Native American children before and after a casino opened on tribal land, Akee et al. (Reference Akee, Copeland, Costello and Simeonova2018) found that receipt of casino payments reduced criminal behavior, drug use, and behavioral disorders associated with poverty such as depression, anxiety, and oppositional disorders, and it also increased agreeableness (i.e., the tendency to be cooperative and get along well with others) and conscientiousness (i.e., the propensity to be hard-working and organized). Similarly, Hörl et al. (Reference Hörl, Kesternich, Smith and Winter2016) used the hunger episode in occupied Germany after WWII as an instrument to test the effect of an exogenous variation in caloric input in childhood on social trust in adulthood. They found that individuals exposed to lower caloric input in 1944–1945 showed decreased social trust later in life. Twin studies offer another way to disentangle the causal impact of genetic and environmental factors. Using this method, Cronqvist et al. (Reference Cronqvist, Previtero, Siegel and White2015) found that individuals with higher birth weight (within pairs of identical twins) are more likely to participate in the stock market (a proxy of risk-taking preference).

To conclude, levels of resources shape individual preferences in a predictable way. Individuals living in conditions of affluence tend to have lower rates of time discounting, to be more optimistic, and to be more conscientious and trustful. But why should this set of preferences be found in eighteenth-century England more than in another place and time? Why were the English the first people to lose the “scarcity mindset” and embrace the “affluence mindset”?

4. The unprecedented affluence of eighteenth-century England

It has long been thought that living standards and GDP per capita were more or less stagnant before the Industrial Revolution (Clark Reference Clark2007). This was based on the Malthusian assumption that any per capita income above some subsistence level would lead to population increases and, consequently, to a decrease in per capita income. However, the Malthusian reasoning is based on the false premise that all innovations should occur in the agricultural sector and should translate into an increased quantity of calories. This is sometimes true – as, for example, during the Neolithic Revolution – but not always. In many cases, in sectors such as clothing, construction, and luxury goods, innovations do not automatically increase the quantity of available calories but instead increase some other aspect of living standards (Dutta et al. Reference Dutta, Levine, Papageorge and Wu2018).

Recent work in historical economics and quantitative history confirms this conclusion and demonstrates that some societies – Classical Greece, Roman Italy, Song China, Medieval Italy – experienced some period of growth (Allen Reference Allen2001; Maddison Reference Maddison2007; Morris Reference Morris2013; Ober Reference Ober2015). Here, I review the evidence concerning the growth of purchasing power, GDP per capita, urbanization, and health. The evidence leads to three conclusions: (1) England enjoyed a long period of growth in living standards from the fifteenth century on; (2) England was richer than any other country, in Europe or elsewhere, on the eve of the Industrial Revolution; and (3) England was richer than any previous society in the history of humanity, including Classical Greece, Roman Italy, Song China, and Medieval Italy.

4.1. Purchasing power

Allen's (Reference Allen2001) seminal work on pre-modern European wages clearly demonstrated that English (and Dutch) workers were much richer than their European counterparts. There was little difference in 1400, but over the following centuries welfare ratios increased in England and The Netherlands and decreased in the rest of Europe. (The welfare ratio is the average annual earnings divided by the cost of a basket of goods necessary for the minimal subsistence of a family of four. A welfare ratio greater than one indicates an income above the poverty line, whereas a ratio less than one means the family is in poverty.) In 1750, the welfare ratio of English craftsmen was 2.21, compared with 1.20 in Paris and 0.97 in Florence. Similarly, the welfare ratio of English laborers was 1.58, versus 0.80 in Paris and 0.90 in Florence (Allen Reference Allen2001; but see Malanima Reference Malanima2013; Stephenson Reference Stephenson2017). Later studies have found that the welfare ratios of Chinese, Indian, and Japanese workers were similar to continental European welfare ratios and much lower than those of the English and the Dutch (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Bassino, Ma, Moll-Murata and Van Zanden2011; Deng & O'Brien Reference Deng and O'Brien2016). Using Diocletian's Price Edict (301 AD), Allen (Reference Allen, Bowman and Wilson2009a) reconstructed the welfare ratio of Roman workers. His estimation points toward a very low welfare ratio, lower than eighteenth-century European and Asian welfare ratios (see Fig. 4). Similar work confirms that workers in ancient economies, even at the peak of the Roman Empire, were probably much poorer than their eighteenth-century English counterparts (Scheidel Reference Scheidel2010).

Figure 4. Welfare ratios of laborers in Europe, Asia, and the Roman Empire (Allen Reference Allen, Bowman and Wilson2009a).

English purchasing power at that time has probably been underestimated, partly because it is difficult to compare luxury goods (furniture, sweets, etc.) across countries and across time. However, it is likely that luxury goods played an important but hidden role in increasing the living standards of the English (De Vries Reference de Vries1994; Hersh & Voth Reference Hersh and Voth2009; Morris Reference Morris2013). For example, Hersch and Voth (Reference Hersh and Voth2009) estimated in a recent paper that the introduction of sugar and tea transformed the English diet in the eighteenth century and increased the welfare of the English by 15%, a gain much larger than those associated with the introduction of the Internet (2%–3%) or mobile phones (0.46%–0.9%). Including tomatoes, potatoes, exotic spices, polenta, and tobacco would show an even larger increase in living standards in eighteenth-century England. During the same period, technological products became much more widely available in England. Nordhaus (Reference Nordhaus, Bresnahan and Gordon1996) famously examined the history of lighting to show that previous studies on the evolution of living costs had vastly underestimated the decline in the cost of many goods. For example, in a recent paper Kelly and Ó Gráda (Reference Kelly and Ó Gráda2016) showed that, during the eighteenth century, the real price of watches fell by an average of 1.3% a year, equivalent to a fall of 75% over a century (Kelly & Ó Gráda Reference Kelly and Ó Gráda2016). Peter King's study on a small number of English paupers’ inventories shows that, in 1700, they rarely possessed clocks, books, candlesticks, lanterns, fire jacks, or fenders. A century later, paupers were materially better provided for than the middle class of a century earlier (King Reference King, Hitchcock, King and Sharpe1997). Just as in the case of the colonial goods referred to above, the impact of these new products on people's welfare is probably underestimated. Dittmar (Reference Dittmar2011) found that the welfare impact of the printed book was equivalent to 3%–7% of income by the 1630s (again exceeding similarly measured welfare effects associated with the Internet or mobile phones).

Including luxury goods thus increases the estimate of growth in living standards in eighteenth-century England (Clark Reference Clark2007, p. 255). It also increases the gap between England and the rest of the world. For example, in 1800, the average English individual consumed 10 times as much sugar as the average French individual and 20 times as much as individuals living elsewhere in Europe (De Vries Reference de Vries1994; Hersh & Voth Reference Hersh and Voth2009). In a recent paper, Lindert (Reference Lindert2016) argued that because of a range of biases in previous estimates, including the difficulty of including luxury goods, the difference between England and the rest of the world was even bigger. His new estimates suggest that purchasing power per capita in England was already higher than in Italy by the beginning of the sixteenth century. At the onset of the Industrial Revolution (in 1775), it was 75% higher than in Italy and 100% higher than in France (in 1820, the earliest year for the England/France comparison). Differences with respect to non-European economies were even larger: In 1750, purchasing power per capita in England was 300% that of Japan; in 1595, it was 280% that of India (the only year for which data are available before the Industrial Revolution); and in 1840 (the earliest year for the England/China comparison), it was 280% that of China. Book consumption confirms this pattern: In 1750, Chinese, Japanese, and Indian book consumption was one-tenth to one one-hundredth of British consumption (Buringh & Van Zanden Reference Buringh and Van Zanden2009; Xu Reference Xu2017).

Finally, recent work by Humphries and Weisdorf (Reference Humphries and Weisdorf2016) suggests that the rise in English wages has been underestimated because of the use of daily wages instead of annual wages. Using income series of workers employed on annual rather than daily contracts shows that incomes rose continuously from 1650, that is, a century before the onset of the Industrial Revolution.

4.2. GDP per capita

In an influential study, Stephen Broadberry and colleagues reconstructed the British economy over the past 800 years. Their work suggests that England experienced a continuous period of growth from the thirteenth century ($711 per capita in 1280) to the eighteenth ($2,097 in 1800). This continuous growth contrasts with the absolute decline of other affluent societies of the time such as China (from $1,032 in 1400 to $597 in 1800) and Italy ($1,477 in 1500 to $1,243 in 1800). More important, English GDP per capita in 1800 was higher than those of all European countries (with the exception of The Netherlands) and much higher than those of non-European countries such as China ($723), Japan ($640), and India ($573) (see Fig. 5). Although Pomeranz (Reference Pomeranz2009) famously argued that there is little sense in comparing China as a whole with England, a small part of Europe, recent studies show that even the wealthiest parts of China, such as the Yangtze Delta, were much poorer than England at the time of the Industrial Revolution ($988 in 1840 vs. $2,718 for Britain in 1850; Li & Luiten van Zanden Reference Li and Luiten van Zanden2012). Reconstructions of ancient economies also suggest that English GDP at the time was higher than that of Roman Italy at its peak (estimates range from $820 to $1,400), Abbasid Iraq ($940), Song China ($1,006 in 1020 under the Songs), or medieval Italy ($1,596) (Broadberry et al. Reference Broadberry, Guan and Li2018; Cascio & Malanima Reference Cascio and Malanima2009; Malanima Reference Malanima2011; Pamuk & Shatzmiller Reference Pamuk and Shatzmiller2014; Scheidel & Friesen Reference Scheidel and Friesen2009).

Figure 5. GDP per capita in 1990 international dollars. Adapted from Broadberry (Reference Broadberry, Guan and Li2018) for China, Japan, Italy, Great Britain and the Low countries, from Pfister (Reference Pfister2011) for Germany, and from Ridolfi (Reference Ridolfi2017) for France.

4.3. Urbanization rate

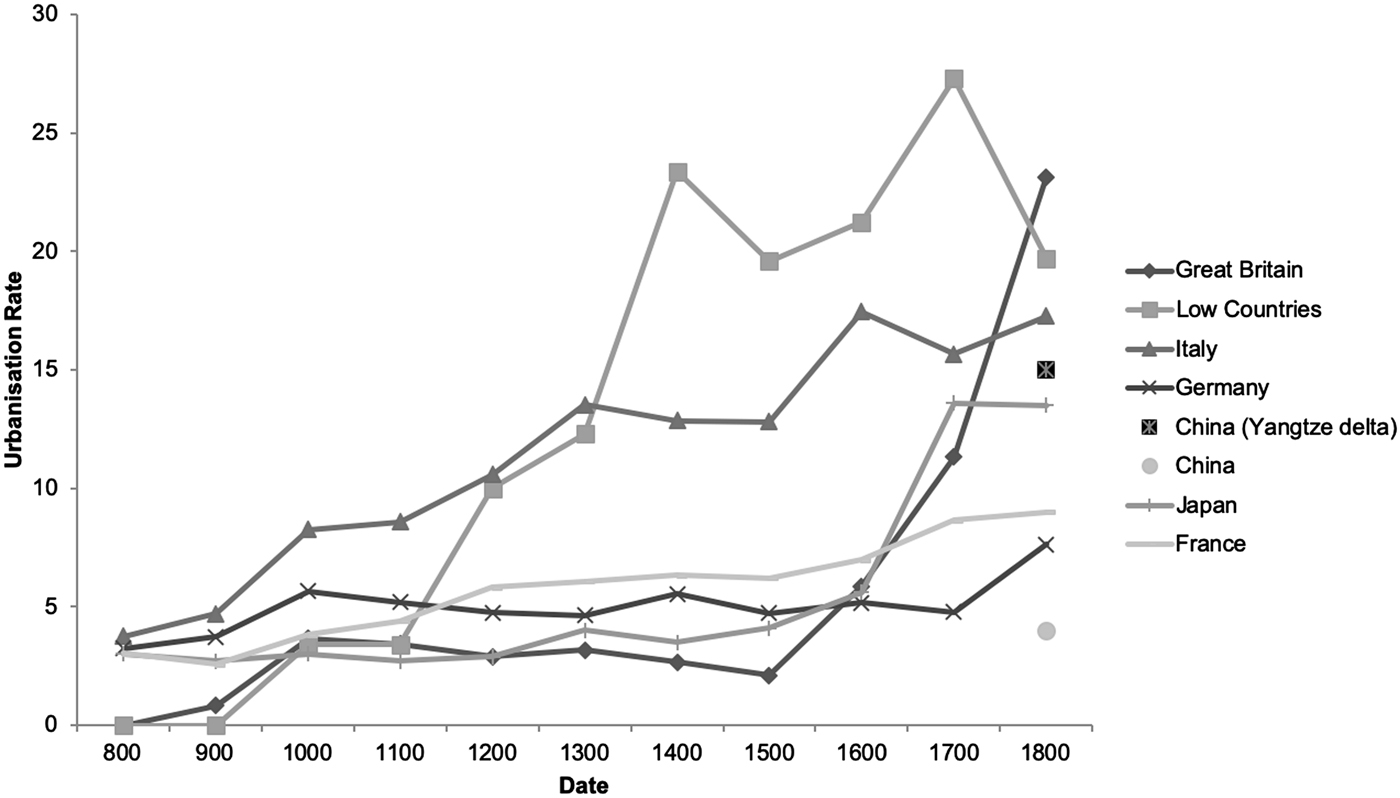

The rate of urbanization is also a good indicator of economic development (Jedwab & Vollrath Reference Jedwab and Vollrath2015). Using Bairoch's database with a threshold of 10,000 inhabitants, Bosker et al. (Reference Bosker, Buringh and van Zanden2013) showed that England was urbanizing at a high rate in the early modern period, going from 2.1% of its population living in urban settlements in 1500 to 23.14% in 1800. Similarly, Scotland went from 3.6% in 1500 to 17.3% in 1800 (see Fig. 6). In the same period, the urbanization of China or Italy was rather stagnant (Xu et al. Reference Xu, van Leeuwen and van Zanden2015). More important, the urbanization rate of England in 1800 (23%) was much higher than in all other societies in 1800, with 4% in China (but 15% in the Yangtze Delta), 9% in France, 13% in Japan, and 17% in Italy and Iraq (Bassino et al. Reference Bassino, Broadberry, Fukao, Gupta and Takashima2015; Bosker et al. Reference Bosker, Buringh and van Zanden2013; Xu et al. Reference Xu, van Leeuwen and van Zanden2015). From a historical perspective, few societies had ever been as urban as England was at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Although the rate of urbanization in ancient Greece and Rome was extremely high for ancient societies, it is estimated that it was about 16% in Classical Greece and 20% in Roman Italy (the latter mostly because of the size of Rome; Bowman & Wilson Reference Bowman and Wilson2011; Ober Reference Ober2015).

Figure 6. Urbanization rate. Sources: Bassino et al. (Reference Bassino, Broadberry, Fukao, Gupta and Takashima2015), Bosker et al. (Reference Bosker, Buringh and van Zanden2013), Xu et al. (Reference Xu, van Leeuwen and van Zanden2015).

4.4. Health

Biological indicators also suggest that England enjoyed steady growth in living standards before the Industrial Revolution. A range of approaches, using the genealogy of the British royal family (David et al. Reference David, Johansson and Pozzi2010), the genealogy of European nobility (121,524 individuals between 800 and 1800; Cummins Reference Cummins2017), the Index Bio-Bibliographicus Notorum Hominum (300,000 individuals before 1879; De la Croix & Licandro Reference de la Croix and Licandro2015), and Wikipedia (Gergaud et al. Reference Gergaud, Laouenan and Wasmer2017) point toward the same result: Life expectancy was on the rise in Europe from 1650 onward. More important, life expectancy in northwestern Europe was higher than in the rest of Europe from 1000 AD onward, and it continued to rise at a higher rate than in the rest of Europe from 1450 onward (Cummins Reference Cummins2017). As a result, life expectancy on the eve of the Industrial Revolution was 42.1 years in England and Wales, compared with 24.8 years in France, for example (Wrigley Reference Wrigley1997). In line with these data, Kelly and Ó Gráda (Reference Kelly and Ó Gráda2014) show that although the positive check – in the sense of the short response of mortality to price and real wage shocks – was powerful in the Middle Ages, it had weakened considerably in England by 1650, unlike in France. Similarly, the last widespread, killing famine occurred in 1597 in southern England and in northern England in 1623. By contrast, the last famine occurred much later in the rest of Europe: in 1710 in France, in 1770 in Germany, Scandinavia, in 1770–1772 in Switzerland and in 1866–1868 in Finland (McCloskey Reference McCloskey2016a). Even bigger contrasts can be observed when comparing England with Asian countries (Clark Reference Clark2007).

Other biological indicators, such as nutrition and height, confirm this difference. In a recent study, Kelly and Ó Gráda (Reference Kelly and Ó Gráda2013) estimated that the English in 1750 consumed an average of 2,900 kcal per day, whereas the French consumed only 1,700 to 2,000 (Fogel Reference Fogel1964; Kelly & Ó Gráda Reference Kelly and Ó Gráda2013). The effects of better nutrition are most obviously noticeable in the differences in the height of adult males. For cohorts born between 1780 and 1815, comparisons suggest that the gap between French and English heights on the eve of the Industrial Revolution was more than 5 cm (Nicholas & Steckel Reference Nicholas and Steckel1991; Weir Reference Weir, Steckel and Floud1997).

4.5. The impact of affluence on upper tail human capital

So far, I have discussed the living standards of the average individual in England, but a growing literature has been documenting the role of an elite of skilled artisans and merchants – the “upper tail of human capital” – in driving technological progress and economic development (Mokyr Reference Mokyr2016; Squicciarini & Voigtländer Reference Squicciarini and Voigtländer2015). In seventeenth- and eighteenth-century England, for example, merchants, lawyers, and capitalists were overrepresented among innovators. They made up 4.6% of the population but accounted for 32.8% of inventors (Allen Reference Allen2009b). This suggests that what matters for economic development is the emergence of a dynamic urban upper middle class.

Of course, skilled elites had existed for a long time before the Industrial Revolution, in Athens, Rome, and Florence. So, what set eighteenth-century England apart from previous societies? The data reviewed below suggest that eighteenth-century English society was simply more affluent than any of those previous societies. This greater affluence had two consequences. First, it increased the absolute number of individuals displaying a slower strategy and, thus, the pool of potential innovators. In other words, the upper tail of human capital was bigger, and it ran further than in previous societies. Not only were the English elites richer, but also all social classes were comparatively more affluent than in any previous society (see Milanovic et al. Reference Milanovic, Lindert and Williamson2011 on pre-industrial inequality). As we have seen, bad harvests ceased to increase mortality rates, first for the elite and then for everyone; life expectancy increased, again first in the elite but soon in the middle class as well; and data on literacy suggest that lower-class English individuals were actually more educated than upper-class Romans (see sect. 4.2).

The second consequence of this English affluence is that the proportion of people displaying a slower strategy was also higher. This means that the levels of social trust, tolerance, and optimism expressed by the average English citizen were higher than elsewhere. This is likely to have had consequences at the global level in terms of interpersonal violence, governance, and even public health, for the simple reason that better-fed people invest more in their immune system and are less likely to transmit pathogens, including to the upper classes (for a discussion about the consequences of poverty on the psychology of the upper class, see Wilkinson & Pickett Reference Wilkinson and Pickett2010; Nettle Reference Nettle2017). Even the circulation of information is likely to be affected, because anxious people tend to focus on, believe, remember, and spread negative information to a greater extent (Fessler et al. Reference Fessler, Pisor and Navarrete2014; Rudaizky et al. Reference Rudaizky, Basanovic and MacLeod2014). This means that, with the same absolute level of material resources, upper-class English individuals in the eighteenth century lived in a better social, political, and biological environment than their fifteenth-century Florentine or first-century Roman counterparts, just because the individuals around them were better fed, healthier, better educated, less violent, and more tolerant.

5. Life History Strategy of the eighteenth-century English

As we saw in section 1, LHT suggests that the environment triggers a set of coordinated behaviors, a global life history strategy. In a recent article, Pepper and Nettle (Reference Pepper and Nettle2017) coined the term “behavioral constellation of deprivation” to refer to the set of behaviors associated with poverty (e.g., early reproduction, low investment in health, present orientation). In the same way, people living in affluent environments should display a “behavioral constellation of affluence”: late reproduction, higher investment in health and cognitive skills, higher levels of trust and cooperation, and a more future-oriented attitude. This last section will examine whether the eighteenth-century English indeed displayed this “behavioral constellation of affluence.”

Obviously, direct measurement of individual behaviors and preferences in the eighteenth century is impossible (at least given current technology, scientists are starting to measure stress through cortisol analysis in archaeological hairs; see, e.g., Webb et al. Reference Webb, Thomson, Nelson, White, Koren, Rieder and Van Uum2010). But a range of indirect evidence is available concerning violence, self-discipline, and long-term investment in human capital. In fact, Norbert Elias had already shown in The Civilizing Process (1982) that from the late Middle Ages on, Europeans, and in particular northwestern Europeans, displayed lower levels of violence, decreasing impulsivity, higher literacy levels, and greater sensitivity to the psychological states of others – in short, a slower life strategy.

5.1. Reproduction and fertility rates

Although the demographic transition has been thought to have occurred quite late in England (at the end of the nineteenth century), long after the Industrial Revolution (Wrigley & Schofield Reference Wrigley and Schofield1983), new studies show that, starting with the generation that married in the 1780s, there was a significant decline in net fertility among the middle and upper classes in England (Clark & Cummins Reference Clark and Cummins2015). Although rich men tended to have more children than poor men before 1780, at this point, they switched from a net fertility of more than four children to one of three or fewer, no different than the general population. This large change in behavior had been hidden in aggregate English data, because at the same time the net fertility of poorer groups (the majority of the population) increased to equal that of the rich. This rapid transition from a fast reproductive strategy to a slow reproductive strategy seems to have started as early as 1780, in parallel to the Industrial Revolution. Crucially, and in line with LHT, it does not seem to have been driven by economic factors such as an increase in returns on investment in education or in children's wages (Clark & Cummins Reference Clark and Cummins2015), but rather by changes in attitudes in the wealthiest part of English society.

5.2. Somatic investment and human capital

LHT holds that individuals living in an affluent environment should invest more in their soma, that is, in both their body and their skills (see sect. 2.2.1). I already noted in section 4 that the English were taller than their European counterparts, a clear cue that they indeed invested more in their soma (on muscular strength; see Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Mokyr and Ó Gráda2014). Regarding investment in cognitive skills, English literacy clearly increased greatly between 1500 and 1750, as England shifted from a society of illiterates to one where half of all individuals could at least sign their names (Stephens Reference Stephens1990). Although England was behind The Netherlands and Scandinavia, it was clearly ahead of other continental countries on the eve of the Industrial Revolution. For example, although only 39% of men and 19% of women were literate in France in 1750, the figures in England were 61% of men and 37% of women (Henry & Houdaille Reference Henry and Houdaille1979; Schofield Reference Schofield1973).

The study of numeracy through age heaping shows similar patterns: English numeracy increased from 1500 onward, and it was higher in 1750 than in most European countries, with the exception of Germany and Scandinavia (A'Hearn et al. Reference A'Hearn, Baten and Crayen2009) (age heaping is the tendency of innumerate people to round their age to the nearest 5 or 10 and is a convenient sign of numeracy in historical documents). Indirect evidence suggests that levels of numeracy in England were also much higher than in India, China, or Japan (Baten et al. Reference Baten, Ma, Morgan and Wang2010; Clark Reference Clark2007), as well as in ancient Rome (Clark Reference Clark2007). For example, the study of age heaping in English, Italian, and Roman censuses reveals that the poor in England around 1800 had more age awareness than officeholders in the Roman Empire (Clark Reference Clark2007). Another indicator of literacy and investment in human capital is the consumption of books, again much higher in England than in other European countries (Baten & Van Zanden Reference Baten and Van Zanden2008; Buringh & Van Zanden Reference Buringh and Van Zanden2009).

What is striking about this high level of investment in human capital is that it cannot be explained by direct incentives. As Clark (Reference Clark2007) notes: “We find absolutely no evidence as we approach 1800 of any market signal to parents that they need to invest more in the education or training of their children” (p. 225). The skill premium in the earnings of building craftsmen relative to unskilled building laborers and assistants was actually lower in eighteenth-century England than in fourteenth-century England, and it was lower than in other European and non-European countries (Van Zanden Reference van Zanden2009). Clark concludes: “If there was ever an incentive to accumulate skills it was in the early economy” (Clark Reference Clark2007, p. 181).

5.3. Prosociality and violence

From a life-history perspective, as the environment improves, individuals should invest increasingly in cooperation (see sect. 2.3.5). The behavior of the English in the eighteenth century seems to have fit this prediction. Data on homicide rates show that the worldwide decline in violence started in England. In the sixteenth century, the homicide rate in England was about 7 per 100,000 inhabitants, versus 25 in the Netherlands, 21 in Scandinavia, 11 in Germany, and 45 in Italy. On the eve of the Industrial Revolution, although the gap had decreased, England was still ahead of the rest of Europe, and indeed the world (Eisner Reference Eisner2003; Pinker Reference Pinker2011a).

Although it must be tempting to think that this decline of violence resulted from the development of the police force and the penal system, evidence shows that they are uncorrelated (Eisner Reference Eisner2003; Pinker Reference Pinker2011a). One reason is that official authorities long treated homicide leniently, as the result of passion or a defense of honor (Eisner Reference Eisner2003). Another relevant fact is that the decline of violence occurred in the same way both in the absolutist regime of Tudor England and in the decentralized Dutch Republic. Similarly, although the police forces in medieval and early modern Italy were particularly large compared with those in England, Sweden, and The Netherlands, levels of violence remained very high in Italy until the end of the nineteenth century (Eisner Reference Eisner2003).

Therefore, people did not stop killing each other for fear of an increasing level of punishment. They rather stopped killing each other because their reaction to offenses and insults became less violent (Eisner Reference Eisner2001), that is, because their psychology became more and more cooperation-oriented. In line with this idea, attitudes toward capital punishment, slavery, judicial torture, and dueling also changed at the same time in Europe. Slavery is a case in point here; it has been shown that slavery was not abolished in response to economic (selfish) incentives, but rather as a result of intense public campaigns based on moral and emotional arguments (see Wedgewood's famous “Am I not a man and a brother?” plate; Carey Reference Carey2005; Davis Reference Davis1999). It is noteworthy that on all of these moral issues, England led the trends throughout the eighteenth century (Eisner Reference Eisner2003; McCloskey Reference McCloskey2016a; Pinker Reference Pinker2011a). More generally, eighteenth-century Europe was clearly ahead of non-European societies as well as ancient societies such as Athens and Rome, which tolerated or even celebrated much higher levels of violence (Pinker Reference Pinker2011a).

Other indicators, such as the flourishing of societies and associations (Clark Reference Clark2000; Sunderland Reference Sunderland2007), suggest that the English were more prosocial and more trusting than other populations in the eighteenth century. Thus, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, England was the first state to implement a system of poor relief. By the end of the seventeenth century, Poor Law expenditure was about 1% of GDP, and it was sufficient to provide complete subsistence for 5% of the population. By the end of the eighteenth century, it further increased to about 2% of GDP (Kelly & Ó Gráda Reference Kelly and Ó Gráda2014). Kelly and Ó Gráda (Reference Kelly and Ó Gráda2014) argue that the system was effectively able to minimize outright starvation. In line with this idea, the link between harvest failure and crisis mortality progressively vanished after the midseventeenth century. Other European countries took much longer to implement such a large-scale system of poor relief.

5.4. Preferences involved in innovativeness

So far, we have explored the standard predictions of LHT. But LHT also predicts that the eighteenth-century English should also have been more patient and optimistic, and less materialistic. These behaviors are obviously harder to observe and quantify than reproduction and somatic investment. But does the evidence point in the right direction?

5.4.1. Time discounting