Introduction

Pediatric delirium (PD) results from a variety of illness or toxic metabolic sources (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). PD has become a serious concern of pediatricians, child and adolescent psychiatrists (CAPs), and other members of the team including nursing, physical therapy, occupational therapy, respiratory therapy, and child life specialists (Schieveld & Janssen, Reference Schieveld and Janssen2014). Delirium has been described as a nontraumatic brain injury (Schieveld et al., Reference Schieveld, van Tuijl and Pikhard2013). In traumatic brain injury, outcomes vary depending on severity of trauma. With delirium, outcome seems related to not only incidence, but also duration of exposure (Traube et al., Reference Traube, Silver and Gerber2017a). As such, preventing and treating pediatric delirium is of utmost importance.

With the development of feasible and valid bedside tools to detect delirium in children of all ages (Traube et al., Reference Traube, Silver and Kearney2014), an increasing number of pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) and general pediatric units have begun to routinely recognize delirium, which has been shown to have a prevalence of 20–65% in critically ill children (Meyburg et al. Reference Meyburg, Dill and Traube2017; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Gangopadhyay and Goben2015; Traube et al., Reference Traube, Silver and Kearney2014, Reference Traube, Silver and Reeder2017b). With improved recognition of delirium, a massive culture change has begun in the PICU. In alignment with adult prevention strategies, pediatricians are reconsidering approaches to sedation and management of agitation to limit the exposure of young, vulnerable patients to deliriogenic medications such as benzodiazepines (Barnes & Kudchadkar, Reference Barnes and Kudchadkar2016; Schieveld & Strik, Reference Schieveld and Strik2017). With less sedation, early mobilization has become feasible (Wieczorek et al., Reference Wieczorek, Ascenzi and Kim2016). Because this has proven effective at decreasing delirium rates and post-intensive care unit myopathy in adults (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Fraser and Puntillo2013), pediatric early mobilization initiatives are emerging in PICUs nationwide (Wieczorek et al., Reference Wieczorek, Ascenzi and Kim2016). An awake, interactive, and mobile patient, even while critically ill, has become a goal in the PICU. This presents a unique set of challenges in pediatrics because of the varying developmental abilities and needs of this patient population (Hopkins et al., Reference Hopkins, Choong and Zebuhr2015). One important piece of this puzzle is family involvement (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Aslakson and Long2017).

Our goal for this paper is to describe a feasibility pilot of our Delirium Prevention Toolkit (DPT), and introduce our “My PICU Journal,” as ways to operationalize family involvement to support decreased sedation and early mobilization, and minimize delirium incidence and duration.

Methods

In a feasibility pilot, from March through June 2016, patients and their families were invited to participate in this project. Inclusion criteria were children 2–12 years old, with an expected PICU length of stay >2 days. We specifically targeted children at high risk for delirium (age <5 years, on invasive mechanical ventilation) and/or those children who were already delirious, to assess feasibility of the toolkit in this hard-to-manage population. The child life specialist educated the families on the purpose and proper use of the toolkit. Certified child life specialists help pediatric patients and their families cope with the stresses of the hospital environment through play and working on coping skills. They are an increasingly important part of the PICU team. For this pilot project, we capped enrollment to two families at any given time. Two days after distribution, the family completed a survey to assess use. The Weill Cornell Medical College institutional review board waived the need for approval in this quality improvement initiative.

Toolkit development

We developed a family-centered DPT incorporating two complementary goals: systematic family involvement in the child's care and developmentally appropriate environmental modifications to help minimize incidence and duration of delirium through engaging and keeping the child awake more during the day and consistently guiding the child to fall and remain asleep at night.

Family engagement

Family-centered initiatives look to increase the parents’ involvement as members of the PICU team. CAPs have increasingly voiced the need to include families. As Winnicott stated (Reference Winnicott1960), “there is no such thing as a baby.” This is magnified in the experience of the hospitalized child who is in a regressive position both because of the nature of being ill and because of the nature of being a “patient.” One thing we know from evidence and experience is that children do better when families do better. We also know that no one is better placed than family members to help aid and inspire children to “sit up and play” or “get out of bed.” Unfortunately, many family members report feeling overwhelmed by the severity of their child's illness. As one mother remarked: “I know how to parent him when he's well, but am afraid to even touch him now that he's so sick.” We believe that a family member, when provided with the proper tools, is uniquely positioned to help orient and engage their child in the PICU, potentially preventing delirium.

Child development

Developmental considerations are of utmost importance in pediatrics (Silver et al., Reference Silver, Kearney and Traube2014) because our goal is to get a child onto a developmental track and optimize the developmental trajectory. This is even more essential when working with medically ill children, especially those in critical condition. The medical team must focus not just on saving the child's life, but also on optimizing the environment for the child's brain to optimize quality of life in survivors (Pollack et al., Reference Pollack, Holubkov and Funai2014). CAPs are an important part of the medical team, providing an understanding of development, family dynamics, family functioning, and as experts in the evaluation of a child's cognitive and emotional state; however, CAPs are in short supply. Other specialists, such as child life therapists, and occupational and physical therapists, are available to provide bedside support with developmentally appropriate therapeutic interventions. Involvement of the family members is essential to this process.

Toolkit

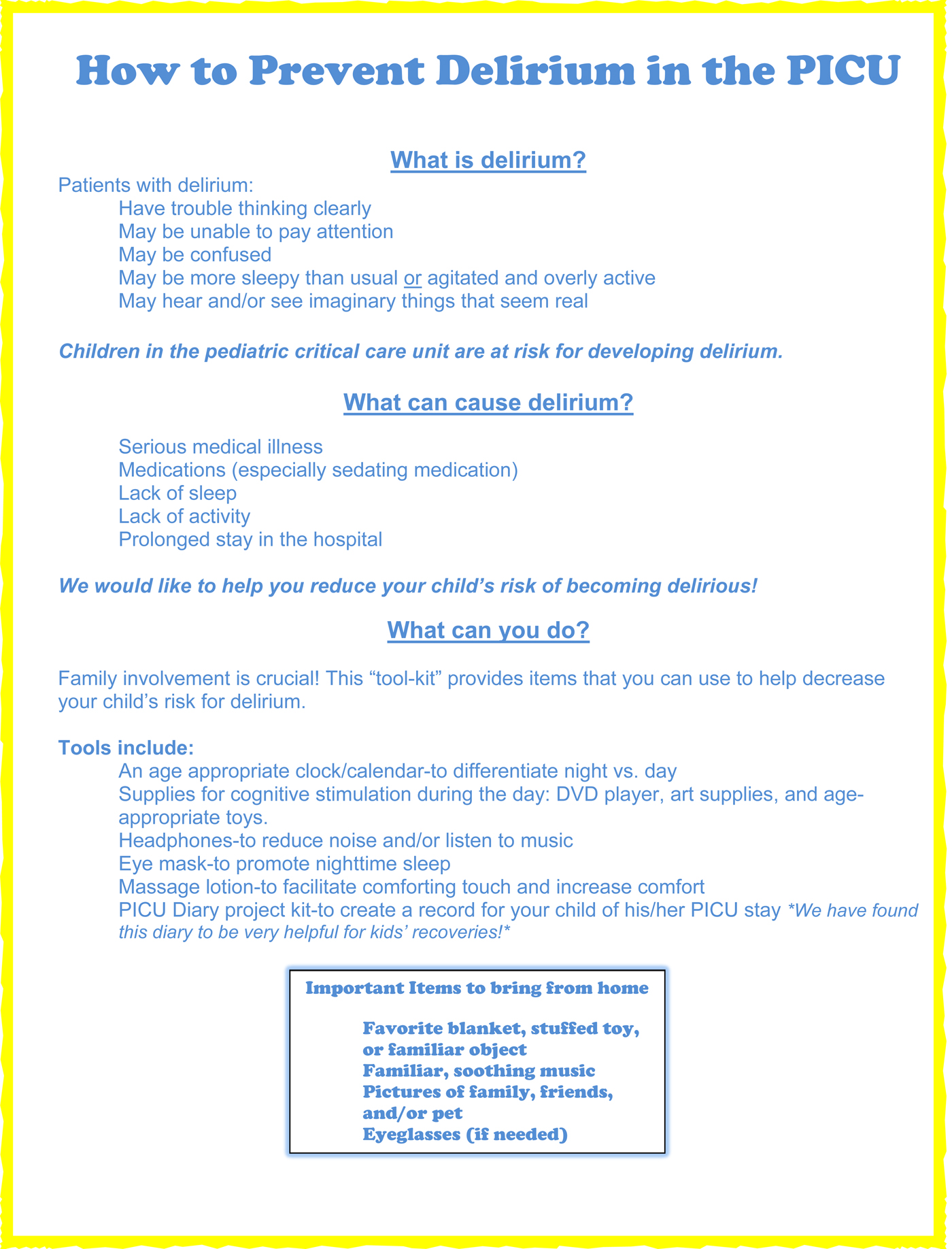

The goal of the DPT is to involve the family in improving orientation and cognitive engagement of children, and decrease need for sedation. Design of the DPT was inspired by the successful implementation of delirium prevention tools in the geriatric literature, as described by Inouye et al. (Reference Inouye, Bogardus and Charpentier1999) and modified for children's developmental needs. The toolkit contains a pamphlet to educate the family about delirium (Figure 1), an age-appropriate “clock” (for our youngest patients, we developed a sun/moon sign that can be hung opposite the bed), and a very basic daily schedule of events to display at the bedside. For daytime use, we include developmentally appropriate toys (with an emphasis on sensory stimulation and cause-and-effect), books, music, a DVD player, and movies. To promote sleep, we include an eye mask to help eliminate ambient light, headphones to reduce noise, and lotion for the family to use for soothing massage. Finally, because there is evidence in the literature that journaling (as a means of developing a true narrative) may help minimize posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety after discharge, we offered a blank notebook and encouraged families to document their stay (Azoulay et al., Reference Azoulay, Pochard and Kentish-Barnes2005; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Backman and Capuzzo2010).

Fig. 1. Delirium education for families

Results

Fifteen families were included in this study. Seventy-one percent of the patients were male. Median age of patient was 10 years and median PICU length of stay was 10 days. Patient descriptives (including admission diagnostic categories) are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient descriptives

The surveys showed that of the 15 families, three did not use the kit at all. Of the 12 remaining families, nearly all used the headphones, DVD player, toys, and games. Most did not use the blank notebook for journaling. Importantly, many families (10/12) responded to the educational material by bringing in familiar items from home such as blankets and pictures, as suggested to help comfort and orient their child. Anecdotally, parents described feeling more engaged and relieved to be able to help their child during their hospitalization.

Implementation of the toolkit varied based on specific patient indications, as illustrated in the case vignettes presented in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Clinical vignettes

Discussion

Meta-analysis of studies for delirium prevention in adults through “multicomponent nonpharmacologic strategies” has shown clear benefit, with decreased incidence of delirium and fewer falls. There are associated trends toward decreased hospital length of stay and fewer patients discharged to an institutional setting (Hshieh et al., Reference Hshieh, Yue and Oh2015). A similar approach has not yet been described in pediatrics. In this pilot study, we demonstrated the practicality of a multicomponent nonpharmacologic toolkit for use in critically ill children. This pilot demonstrated good feasibility and anecdotal satisfaction from patients and families. Future research is necessary to determine the effect of this toolkit on pediatric delirium rates.

In spite of the fact that there is a broad literature encouraging the use of journaling for various mental illnesses (e.g., PTSD, depression, anxiety), and it is one of the few psychological interventions described in the PICU literature (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Backman and Capuzzo2010), our blank journal was not used by most families in this pilot. Parents described being “at a loss” as to how to begin and too distracted by the child's acute illness to organize the story. To address this problem, members of our research team, including a parent representative, child life specialist, and child psychiatrist, developed a structured template for “My PICU Journal” (copyright in progress), a user-friendly kit with pre-made pages that can be added or subtracted from a patient's story to fit their own journey through the PICU. We expect that, by providing this template, we will better facilitate journaling for our distressed families, improve parent satisfaction, and help with metabolizing the experience for the child and his or her caretakers. Developing meaningful approaches to engage family members and provide resources for them to help their ill children is key to improving hospital care.

Further research is required to systematically assess the effects of the DPT on delirium incidence and duration and quantify family involvement and satisfaction. Future studies will also investigate the role of “My PICU Journal” in decreasing rates of PTSD in children and caregivers.

Conclusion

A targeted nonpharmacologic intervention to help prevent delirium in high-risk children may be able to decrease delirium rates. A family-centered toolkit may provide overwhelmed parents with a structured method for interacting with their critically ill child. This approach has potential to improve short and long-term outcomes of PICU survivors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgments

Alexandra Watson, Child Life specialist, Weill Cornell Medical College, whose work with our families with development of the toolkit, and cocreator of “My PICU Journal” has been central and inspiring. Kimberly LaRose our parent representative and co-creator of “My PICU Journal.” Sydney Feinstein, research assistant. The project was conducted with the support of the Department of Pediatrics and Child Life.