Is the West in retreat? Is the era of Western liberal dominance led by a preeminent America over? While it may be premature to declare the era of Western ascendancy over, domestic support for liberal internationalism is weakening across the West. On issues ranging from immigration, to international trade, to global governance, political parties on the ultra-left and ultra-right are rejecting core principles of liberal internationalism that have long united Western democracies. Radical-left and radical-right parties are offering alternative, divisive foreign policies and party platforms. Established mainstream political parties—Social Democratic, Christian Democratic, and Conservative and Liberal—long the backbone of the West’s defense against illiberalism from abroad, are now on the political defensive at home. Older parties are groping for answers to challenges to the liberal international order that are home-grown, and that show little sign of easing anytime soon.

Much of the debate over the crisis of the Western liberal international order has focused on recent changes: Donald Trump’s “America First” presidency, Britain’s decision to leave the European Union, and the surge of nationalist sentiment in France, Germany and other Western democracies (e.g., Haass Reference Haass2017; Luce Reference Luce2017). We show that the decline in domestic support for liberal internationalism is not as recent as these examples suggest. An array of cross-national data from 1970 through 2017 for twenty-four OECD countries and some 400 political parties shows clearly that party and voter support for liberal internationalism has been receding in Western democracies for a quarter century. We analyze changes in the level and nature of Western government and party support for liberal internationalism from its Cold War apex in the 1970s through the present era and show that government policy and party politics are now visibly out of alignment. A large and widening gap has opened up between the West’s international ambitions and its domestic political capacity to support them.

We show that during the Cold War mainstream parties were the bedrock of the Western liberal international order. Across the West, political leaders could advance liberal internationalist policies safe in the knowledge that a broad cross-section of political parties representing the vast majority of the electorate would support these policies. This began to change in the 1990s, as Western governments came to rely increasingly on liberalized trade, institutionalized cooperation, and multilateral governance. Mainstream parties that backed and promoted these efforts began to lose electoral ground to anti-globalist parties on the radical-left and increasingly, on the radical-right. The populist backlash against Western governments that we see today represents an intensification of a process that has been visible across the OECD for over two decades.Footnote 1

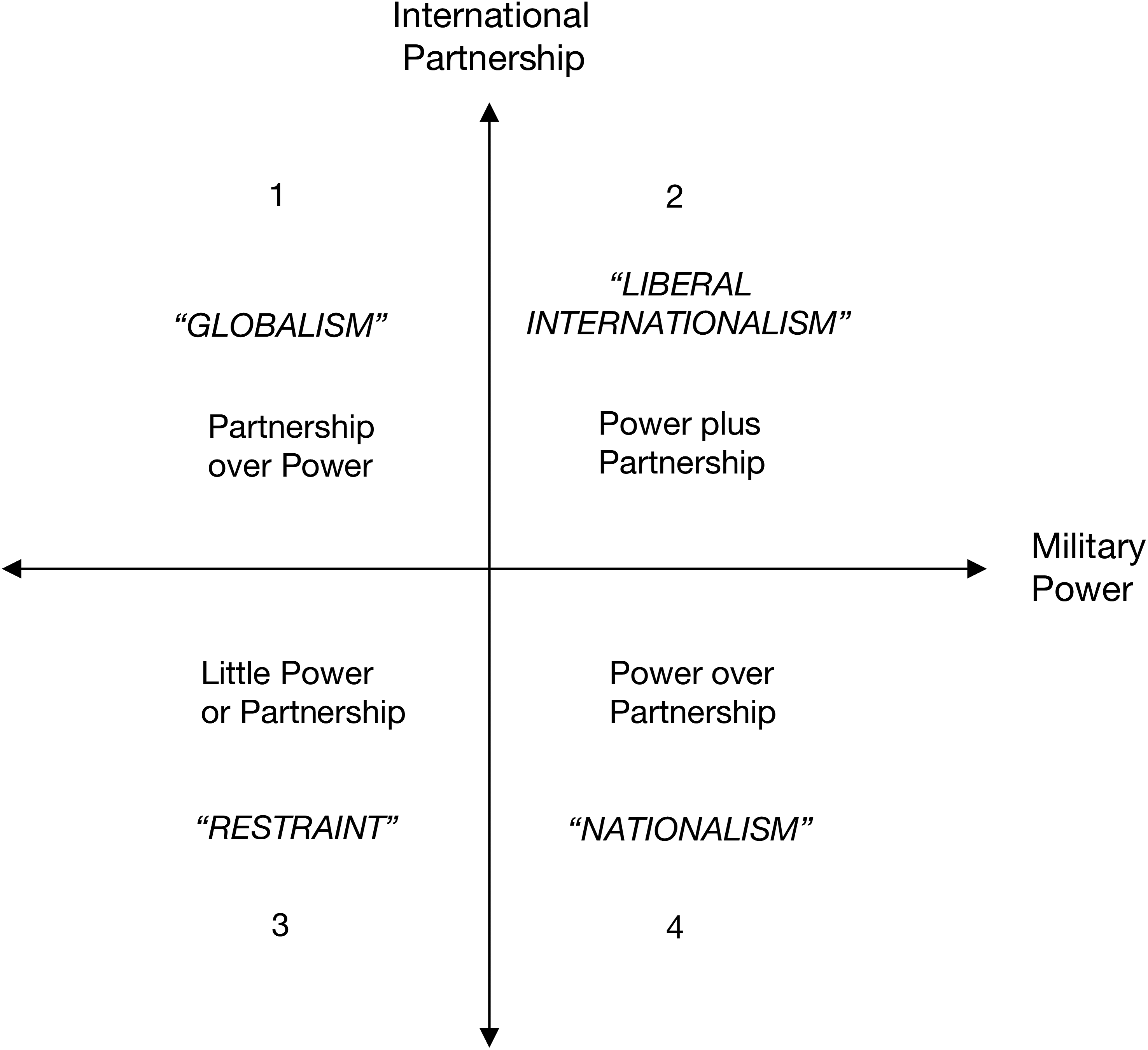

In making this argument about the erosion of liberal internationalism’s domestic foundations, we model government policy and political parties’ commitments to liberal internationalism along two separate but related foreign policy dimensions, which we call “power” and “partnership.” By power, we mean a commitment to invest domestic resources in national militaries and national defense capabilities and maintaining military preparedness. By partnership, we mean a commitment to economic openness, institutionalized cooperation, and multilateral governance. This two-dimensional model yields four combinations of what can be conceptualized as varying levels of investment in power and partnership, each of which corresponds to four recognizable strategies or approaches to international statecraft: globalism; liberal internationalism; “restraint”; and nationalism.

Using this two-dimensional framework, we show that the defining feature of liberal internationalism during the Cold War was Western democracies’ commitment to both power and partnership. It is this double commitment that has unraveled since the Cold War ended. As Western governments came to rely increasingly on international partnership. Western voters turned gradually away from mainstream parties promoting liberal internationalism in favor of anti-globalist parties advocating foreign policy strategies of restraint and nationalism. It was only a matter of time until political entrepreneurs like Donald Trump, Boris Johnson, and others found a way to exploit voters’ disillusionment with liberal internationalism for electoral gain. Today, Western democracies are reaping the bitter harvest of years of neglecting voters’ resentment and anger about the rising costs of their governments’ foreign policies in terms of economic security and national sovereignty.

A variety of cross-national data characterizing the foreign policy orientations of Western democracies support these arguments about the growing disconnect between Western governments and their electorates. These include indicators measuring national spending on guns and butter, as well as various indices measuring the degree to which countries’ foreign policies promote international economic openness, membership in international organizations, and the signing of multilateral treaties, among others. We rely on party manifesto and electoral data to measure party and voter support for liberalized trade, military spending and preparedness, and international institutions and multilateral governance. Taken together, these measures allow us to test our arguments about liberal internationalism’s trajectory since the height of the Cold War and the growing gap between the West’s international commitments and its domestic political capacity to support them since the East-West struggle ended.

Our analysis supports three important claims. First, we show that Western governments’ approach to international order-building has changed in important ways in the past quarter-century. During the Cold War era, the United States, Europe, and most of the rest of the OECD shared a vision of liberal international order that rested on a robust commitment by their governments to both military power and international partnership. By contrast, since the end of the Cold War Western governments have invested fewer resources in power (military spending as a percent of GDP declined rapidly in most OECD nations) while investing heavily in partnership through liberalized trade agreements and multilateral treaties and governing arrangements. Western governments shifted from a strategy of liberal internationalism that relied on both partnership and power, to what we call a strategy of globalism that put greater emphasis on partnership. The West’s reliance on international partnership accelerated in the 1990s and continued through the 2008 global financial crisis to the current era.

Second, we show that while Western government investment in economic liberalization and institutionalized cooperation has increased since the end of the Cold War, party support for these foreign policies has not kept pace. We show that the mainstream parties that promoted and sustained liberal internationalism during the long struggle between East and West have been steadily losing electoral and legislative ground to radical-left and, increasingly, radical-right parties pushing anti-globalist platforms and agendas. Our data show that this process began at the pinnacle of American (and Western) triumphalism following the end of the Cold War (Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama1989; Krauthammer Reference Krauthammer1990). Indeed, we show that radical-right parties have directly benefited from running on party platforms that oppose international partnership. Today, the mainstream party foundation of the West’s liberal international order is a pale shadow of what it was during the height of the Cold War.

Third, we show that what is true of Western democracies in general is also true of the West’s preeminent power: America. Its commitment to international partnership also increased, albeit less conspicuously and less fully than European democracies did. The United States has always been less willing to pool sovereignty and sacrifice power for partnership than have many of its allies. Nevertheless, since the end of the Cold War, the United States has also invested more heavily on the partnership side of the power-partnership ledger, its wars in Afghanistan and Iraq notwithstanding. Americans may be from Mars and Europeans may be from Venus, to paraphrase Robert Kagan’s (Reference Kagan2002) famous formulation, but in the thirty years since the collapse of the Soviet empire, what stands out is not how different America’s and Europe’s approaches to liberal international order-building are, but rather their similarities.

This paper is organized into five sections. The first section sketches out our two-dimensional framework for analyzing Western democracies’ foreign policy preferences and the domestic trade-offs that investing in partnership and power involve. In section two, we describe our approach to measuring changes in Western governments’ foreign policies and document their growing reliance on foreign policies of international partnership since the 1990s to strengthen and expand the liberal international order. We show that there has been a clear shift in the balance between Western foreign policies favoring partnership, and policies favoring power. Section three examines Western party support for foreign policy by party type or family. We show that party support for both international partnership and military power tends to be higher among mainstream parties than among parties on the radical-left and radical-right. In section four, we show how relative vote shares for mainstream and radical parties affect their governments’ investment in liberal internationalist policies. We also document the decline in Western voter support for parties favoring international partnership and show how radical-right populist parties are capitalizing on it electorally. We conclude by considering the implications of our findings for the future of the Western liberal international order and strategies now on offer to repair it.

Power, Partnership, and International Order

Nearly twenty years ago, Robert Kagan challenged the widely held notion that the West shared a common view of international order-building (Kagan Reference Kagan2002). Americans, Kagan argued, were more apt to rely on power and coercion to promote international order and stability. By contrast, Europeans preferred diplomacy, negotiation, and partnership to manage international conflict and strengthen the international order. Ever since, international relations scholars and foreign policy analysts have debated the extent of Western differences over foreign policy, how best to characterize them (as a clash of ideas or interests, or as Kagan suggested, of values), and the sources of these differing strategic cultures or perspectives (Anderson, Ikenberry, and Risse Reference Anderson, Ikenberry and Risse2008; Dorman and Kaufman Reference Dorman and Kaufman2011; Lake Reference Lake2018; Lindberg Reference Lindberg2005). Most of these efforts, including Kagan’s own formulation, assume, implicitly or explicitly, that Western approaches to international order can best be represented along a single continuum: power versus diplomacy, unilateralism versus multilateralism, modernity versus post-modernity, among others.

One-dimensional models like Kagan’s are suggestive, but they presuppose high levels of global engagement. In Kagan’s model, what distinguishes Western democracies from one another is not the level of support for international engagement, but the type of engagement and leadership they favor. Americans, Kagan argues, are more likely to invest in military power to manage international problems. Europeans prefer diplomacy and negotiation to power politics. Yet as suggested by Donald Trump’s “America First” credo, Britain’s Brexit vote, and the surge in support for populist parties in Europe, many Western politicians and their followers do not favor international engagement across the board. These politicians see no intrinsic value in policies and institutions that actively promote freer trade, open immigration, common defense, and other features of the liberal international order. The existing models leave little room for leaders, parties, or movements like these that oppose deep international engagement and favor other forms of international order. The nationalist and populist surge today thus exposes the limits of models of Western democracies’ foreign policy strategies like Kagan’s, which focus only on different understandings of and approaches to internationalism, but not support for or opposition to it.

We argue that to model the political dynamics driving the current debate over the future of the West, internationalism itself should be conceptualized along two separate dimensions. We call these power and partnership, as in figure 1. Here, the horizontal dimension measures the extent to which Western democracies invest domestic resources in building up national militaries and national defense capabilities and in maintaining military preparedness.Footnote 2 Because states’ resources are limited, political leaders must decide how much military power is enough and whether to rely on strategies that make fewer demands on the government’s resources (Brodie Reference Brodie1965; Oatley Reference Oatley2015; Trubowitz Reference Trubowitz2011). Political economists often describe this trade-off as a choice between guns and butter. States must decide how much to spend on national defense (guns) versus social welfare (butter). Where leaders, parties, and voters stand on this continuum tells us something about the relative weight they attach to international and domestic priorities.

Figure 1 Structure of Western debate over international order

The vertical dimension in figure 1 refers to international partnership. It measures the extent to which Western democracies actively promote international economic openness, institutionalized cooperation, and multilateral governance arrangements. Here, too, political leaders face choices and trade-offs. They must decide how much discretion over national policies to surrender in order to comply with standards set by international institutions, treaties, and agreements (Hafner-Burton, Mansfield, and Pevehouse Reference Hafner-Burton, Mansfield and Pevehouse2015). There is an extensive literature on when and why states elect to voluntarily pay what Moravcsik (Reference Moravcsik2000) aptly calls the “sovereignty costs” of international cooperation (e.g., Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2001; Lake Reference Lake2009; Ruggie Reference Ruggie1982). Motivations can vary from gaining access to larger markets and capital, to bolstering physical security through alliances, to reassuring foreign investors about states’ commitment to private property rights, and so on. The vertical dimension tells us something about how willing states are to pool authority internationally to achieve such valued national goals.

This two-dimensional model yields four permutations of “power and partnership”: “partnership over power” (quadrant 1), “power plus partnership” (quadrant 2), “little power or partnership” (quadrant 3), and “power over partnership” (quadrant 4). These combinations are consistent with four identifiable strategies or foreign policy approaches: globalism (quadrant 1); liberal internationalism (quadrant 2); the strategy known as “selective engagement” in the 1990s and that today is often referred to as “restraint” (quadrant 3);Footnote 3 and nationalism (quadrant 4). We briefly describe each of these general approaches to international order, starting with “globalism” in quadrant 1.

Globalism favors partnership over power. Globalists view power politics, militarism, and nationalism as root causes of international instability and war, and see international openness, institutionalized cooperation, and multilateral governing arrangements that pool sovereignty as means to curb nationalist passions, make borders more porous, and check hegemonic ambitions. Investing in partnership fosters peaceful relations, promotes commerce, and spreads liberal values, or so globalists argue (Angell Reference Angell1912; Held Reference Held1995). Robert Cooper characterizes contemporary Western democracies that subscribe to these liberal principles and Kantian ideals as “postmodern”—postmodern because they rely on “moral consciousness,” the rule of law, and institutionalized cooperation instead of traditional raison d’état, military strength, and balance of power to manage the risks and uncertainties associated with international anarchy (Cooper Reference Cooper2000). States that firmly locate themselves in this quadrant invest fewer resources in military power and are reluctant to use it for purposes other than mutual self-defense and the protection of human rights. Woodrow Wilson’s failed plan for building an open international order of law and institutions was an early attempt at this approach to international order-building. Today’s supranational European Union, which pools sovereignty and guarantees the free movement of goods, capital, services, and people across borders, stands as its greatest achievement (Birchfield, Krige, and Young Reference Birchfield, Krige and Young2017).

If globalists favor partnership over power, liberal internationalists (quadrant 2) seek to fuse the two into one. Liberal internationalists also see international commerce, institutionalized cooperation, and multilateral diplomacy as means to tame national ambition, encourage political moderation, and foster international community. Yet they also think power has its place, and they are not reluctant to use it to defend national borders, balance against foreign threats, or promote democratic values (Kupchan and Trubowitz Reference Kupchan and Trubowitz2007). In a world of sovereign states, liberal internationalists do not think the Hobbesian challenges of preserving security can be solved, but they think those challenges can be managed if partnership is supported by power. As John Ikenberry has persuasively argued, this very intuition lies at the core of the liberal international order that the West built after World War II, and in the thinking of its chief architect, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2009). Scholars and policy-makers who associate liberal internationalism with globalism are thus not wrong. Liberal internationalism does entail a commitment to institutionalized cooperation and multilateral governance, along with international openness (Hoffman Reference Hoffmann1995). But for much of the post-World War II era, liberal internationalism also involved a commitment to invest in national military power as a complement to international partnership. Indeed, this dual commitment to power and partnership is liberal internationalism’s distinguishing feature (Brooks and Wohlforth Reference Brooks and Wohlforth2016; Kupchan and Trubowitz Reference Kupchan and Trubowitz2007; Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann1995).

In contrast to liberal internationalism, the strategy of restraint (quadrant 3) attaches comparatively little weight to international institutions and multilateral governance. At best, proponents of restraint see international institutions as irrelevant; at worst, they consider them a threat to national sovereignty. Advocates of restraint take a dim view of large, expensive armies and the unnecessary risks they pose, whether this be the risk of centralization of power, of stoking imperial ambitions, or of strategic overexpansion. In principle, proponents of restraint oppose or are deeply skeptical of both power and partnership (Gholz and Press Reference Gholz and Press2001; Posen Reference Posen2014; Sapolsky et al. Reference Sapolsky, Friedman, Gholz and Press2009).Footnote 4 However, in the real world, this “ideal point” is nearly impossible to achieve. As a practical matter, restraint’s advocates often find themselves playing defense, arguing for ways to manage international involvement with the least possible risk and cost. In the American context, restraint is most closely identified with Thomas Jefferson and his vision of a national “empire of liberty,” free of standing armies and entangling alliances that were commonplace in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe (Tucker and Hendrickson Reference Tucker and Hendrickson1990). Today, libertarians are its principal champions.

Nationalists (quadrant 4) share restrainers’ aversion to international institutions and multilateral governance. They think first and foremost about national sovereignty. However, unlike restrainers, who worry as much about the dangers of militarism as the risks of pooling sovereignty, nationalists strongly support building and maintaining large armies. They are also not hesitant to use firepower to protect vital national interests: territorial boundaries; spheres-of-influence; core economic interests (e.g., export markets, trade routes, raw materials). As John Mearsheimer points out, in this crucial respect, nationalists are close cousins of realists (Mearsheimer, Reference Mearsheimer2018). Populists like France’s Marine Le Pen belong in this nationalist quadrant. In her run for the French presidency, she vowed to invest more of France’s GDP in defense while liberating it from the “tyrannies” of globalization and the European Union (Henley Reference Henley2017). Donald Trump, whose foreign policy evokes comparisons to the country’s first populist president, Andrew Jackson, belongs here, too (Mead Reference Mead2017). Like Jackson, Trump sees military power the way he sees economic power: as a means to promote narrowly defined national interests.

The Erosion of Liberal Internationalism

We use this conceptual framework to map out Western democracies’ foreign policy preferences and consider whether they have changed over time, and if so, along which two underlying dimensions. In this section, we focus on Western governments’ policies.Footnote 5 We constructed government policy output indicators for power and partnership for twenty-four OECD countries.Footnote 6 For power, we rely on total national defense expenditure (share of GDP) published by Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI 2018). Military spending as a share of GDP is a widely used indicator by international relations scholars, diplomatic historians, and foreign policy analysts to assess states’ willingness to invest in military power (e.g., Gaddis Reference Gaddis2005; Oatley Reference Oatley2015; Mearsheimer Reference Mearsheimer2001).Footnote 7 This metric is deeply woven into the fabric of public discourse in Western democracies and figures prominently in national election campaigns and public debates like the current one over “burden sharing” within NATO (e.g., Cordesman Reference Cordesman2018).Footnote 8 While it does not directly measure Western democracies’ propensity to use military force, previous research shows that public support for military spending is highly correlated with public support for the actual use of force (Eichenberg and Stoll Reference Eichenberg and Stoll2017).Footnote 9

For partnership, we rely on KOF Swiss Economic Institute indices measuring government policies to promote and regulate economic and political globalization (Dreher Reference Dreher2006; Gygli et al. Reference Gygli, Haelg, Potrafke and Sturm2019).Footnote 10 KOF’s economic globalization policy index monitors variations in tariff rates, trade regulations and taxes, capital account openness, and international trade and investment agreements—policy tools that governments use to stimulate or restrict cross-border flows of goods, capital, services. KOF’s political globalization policy index measures country membership in international organizations, signed international treaties, and how multilateral its treaties are.Footnote 11 Together, they capture the extent to which a country’s government invests in institutionalized cooperation and multilateral governance. Our partnership measure is a composite index of these two KOF indices from 1970 through 2016.Footnote 12

Figure 2 summarizes the results of our aggregated and longitudinal analysis of Western democracies’ support for power and partnership. The horizontal axis represents the level of Western government investment in military strength and preparedness (military power). The vertical axis represents the level of Western government policy support for economic and political globalization (international partnership). To provide reference points, we set the axes in figure 2 using the full-sample country-year medians with respect to the spatial distribution of countries (110 countries total in the sample) and time period (1970–2016). These yield rough approximations of the four quadrants discussed in figure 1. For ease of visual interpretation, we label the four combinations of power and partnership in the corners of their respective quadrants in figure 2. While the KOF data does not cover the entire post-World War II era, it does span enough of that era to enable us to compare and contrast Western democracies’ support for liberal internationalist policies during and after the Cold War.Footnote 13

Figure 2 Western support for international partnership and military power, 1970–2016

Figure 2 broadly conforms to expectations. During the 1970s and 1980s, the West as a whole clearly favored an approach to international order-building that relied equally on military power and international partnership. It is located in the top right quadrant. Forged in the shadow of the Cold War, the West’s liberal internationalist strategy was organized around two regional axes, with the United States at the center of each. One was an Atlantic axis binding North America and Western Europe; the other, a Pacific axis tying Japan and other non-communist Asian nations to the United States. Similar economic, political, and military means were used to develop and expand both halves of the system, albeit in different combinations and at different rates. Often described as Pax Americana, the Western system was dominated by the United States. However, it was not a distinctively American system, or unilaterally imposed by Washington. European and Japanese leaders saw geopolitical benefits in a system that combined power with partnership (Forsberg Reference Forsberg2000; Lunderstad Reference Lunderstad1986).

Of course, geopolitical imperatives were not the only reason Western democracies favored liberal internationalism. As John Ruggie (Reference Ruggie1982) and others have argued, Western support for liberal internationalism also rested on a crucial domestic bargain—the so-called compromise of “embedded liberalism.” In the 1930s, Western democracies’ commitment to full employment, social insurance, and the welfare state expanded. At Bretton Woods, Western policy-makers looking to rebuild the postwar world economy agreed to preserve those domestic commitments, and the peace between capital and labor they bought. Western policymakers struck a balance between international openness and national autonomy that kept globalization within manageable bounds during the Cold War (Rodrik Reference Rodrik2011). Despite considerable variation in institutional make-up, Western democracies each found ways to harmonize economic openness with social protection at a time of East-West rivalry.

Liberal internationalism allowed the West to achieve a level of integration and coherence that set it apart from the rest. Yet even before the Soviet empire collapsed in the early 1990s, the West’s commitment to liberal internationalism’s distinctive combination of power and partnership had weakened. While Western governments continued to invest in military power, the economic slowdown of the 1970s led them to do so at a lower and declining rate.Footnote 14 Meanwhile, Western governments in the 1980s began moving increasingly away from the managed globalization of the postwar era toward a more market-based “neo-liberal” approach. In the trade realm, for example, Western leaders launched the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations that led to lower global tariffs and the strengthening of international authorities’ hands to settle trade disputes through the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Western governments also deepened their commitment to regional integration. In Europe, the European Community was expanded. The 1986 “Single European Act” created a single market in goods and services and transformed the European Commission into a powerful agent for market liberalization. In North America, the 1983 Caribbean Basin Initiative was followed in 1988 by the U.S.-Canadian free trade agreement. In Asia, an Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum was created to promote freer trade in the region.

In the 1990s, the West’s reliance on international partnership accelerated. As figure 2 indicates, over the course of the 1980s the center of gravity in the West shifted from a strategy relying on both international partnership and military power to one privileging partnership at the expense of power. Between 1990 and 2016, the average level of defense spending as a percentage of GDP in Western democracies continued to drop, falling from 2.5% to 1.4%. Less power on average did not mean less partnership, however. During this period, Western capitals’ willingness to pool authority internationally increased across a wide range of issues (Blyth Reference Blyth2002; Gygli et al. Reference Gygli, Haelg, Potrafke and Sturm2019, 562; Pevehouse, Nordstrom, and Warnke Reference Pevehouse, Nordstrom and Warnke2004).Footnote 15 The West’s security architecture was also reshaped and updated. In Europe, this involved the unification of Germany and the integration of the former Warsaw Pact states and Soviet Baltic republics into NATO (and the European Union). In Asia, Washington and Tokyo reaffirmed their alliance commitments. Meanwhile, regional integration in Europe, North America, and Asia-Pacific continued apace on a wide range of economic and political issues.Footnote 16

Western investment in international partnership reached its apex in the early 2000s before leveling-off and even modestly dropping. As figure 2 indicates, Western government support for international openness and international cooperation was not shaken by the Iraq War or by the 2008 global financial crisis. As we show later, the war did not drive the West apart. Nor did the Great Recession lead to “deglobalization.” After the initial shock, global trade, investment, and output rebounded. One important reason is that the existing international institutional architecture proved to be far more robust than expected (Drezner Reference Drezner2014). In the area of international trade, the WTO was able to prevent or at least limit many forms of trade policy backsliding. Whatever tariff and non-tariff barriers Western governments adopted in the short term were offset by increased participation in multilateral institutions and treaties and growing enthusiasm for regional and bilateral Free Trade Agreements (FTAs).Footnote 17 As figure 2 indicates, ten years after the 2008 crash, Western government policies promoting trade, institutionalized cooperation, and multilateral governance continued to dwarf levels reached in the 1970s and 1980s.

What is true of the West as a whole is also true of its two most influential actors: the European Union and the United States. Figure 3 reports the results for the EU and the United States. We also include Japan for comparative purposes, given that the Japanese Constitution inhibits military investment comparable to most Western powers.Footnote 18 We see in figure 3 that over the entire time period, there is very little distance between the EU-15 and the United States over international partnership (vertical dimension) and that as EU support for international openness and cooperation increases, so does U.S. support.Footnote 19 On the horizontal dimension (military power), the distance between the EU-15 and the United States narrows over time.Footnote 20 Overall, though, the EU and United States follow the general pattern we see in figure 2. In the 1980s, Western governments move away from a strategy that relies heavily on both power and partnership (liberal internationalism) to one that relies increasingly on partnership (globalism), and this process accelerates in the 1990s and early 2000s. While Washington never fully embraces globalism, it does follow a path that is strikingly similar to the EU’s.

Figure 3 Western support for international partnership and military power by major power, 1970–2016

Japan’s trajectory is clearly different than America’s and Europe’s. Not surprisingly, Japanese investment in power is extremely low by Western standards. Japanese defense spending averaged less than one percent (0.96%) during the 1990s through 2000s. This is not significantly different than Japan’s defense burden during the 1970s and 1980s, when it averaged 0.89% of GDP. Yet like the EU-15 and the United States, Japan’s investment in international partnership increases over time, and substantially so during the 1990s and especially, the 2000s. This was a very active period of Japanese diplomacy. In the 2000s, Japan signed free trade agreements with Singapore (2002) and Mexico (2005). Similar trade negotiations were launched with the Philippines, Thailand, and Malaysia, among other countries in the region (Urata Reference Urata2009). Tokyo also expanded its level of participation in multilateral peacekeeping and non-lethal international security missions (Liff Reference Liff2015). In short, as Japan invested more heavily in international partnership, its foreign policy priorities more closely aligned with America’s and Europe’s.

Taken together, the patterns in figures 2 and 3 tell us two important things. First, with few exceptions Western democracies have followed a similar foreign policy path from Cold War to the present. Once deeply committed to liberal internationalism, Western governments turned increasingly toward a strategy of globalism and foreign policies that relied more on partnership than on power. In the aftermath of the Cold War, this realignment gathered speed in the 1990s and then slowed and leveled off in the 2000s where it has continued to the present. Second, contra early post-Cold War predictions that the West would quickly divide and splinter over economic and security issues in the absence of geopolitical imperatives, the West became more integrated (and larger geographically).Footnote 21 The September 11 attacks, the Iraq War, and the Great Recession did not fundamentally alter the path Western governments followed for the next quarter century. Yet as we will show, Western governments’ commitment to ever-greater internationalization was not matched by a corresponding increase in domestic political support. As Western democracies’ international ambitions expanded, they became increasingly detached from what their parties and voters were willing to support.

The West’s “Vital Center”

In 1949, the historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. published The Vital Center, a best-selling call to arms (Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger1949). Often remembered as an appeal for bipartisanship, the term “vital center” actually referred to a middle point on the political spectrum, lying between radical-left politics and radical right-wing parties. Schlesinger saw mainstream parties of the late 1940s as Cold War liberalism’s best defense against the spread of Soviet-style communism or a possible resurgence of the laissez-faire capitalism that resulted in depression and war. Though writing principally for an American audience, Schlesinger’s view that mainstream parties offered the best hope for guaranteeing security and prosperity echoed public sentiment in Britain, France, Germany, and other Western democracies. As we show in this section, mainstream parties—Christian Democratic and Social Democratic, Conservative and Liberal—have in fact been liberal internationalism’s staunchest advocates, opposing the pacifism and “one-worldism” of the extreme left and the narrow nationalism and xenophobia of the extreme right.

Our analysis here draws on the Manifesto Project database. This is a widely-used database of political manifestos (party platforms) for individual political parties, by country and by election year (c.f. Benoit, Mikhaylov, and Laver Reference Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2009; Budge et al. Reference Budge, Klingemann, Volkens, Bara and Tannenbaum2001; Klingemann et al. Reference Klingemann, Volkens, Bara, Budge and McDonald2006).Footnote 22 The Manifesto Project database includes all OECD countries and over 455 political parties from our sample years 1970 to 2017. The coding unit in the Manifesto Project database is the number of sentences or sentence fragments (quasi-sentences) in party platforms that give attention to or take a position on a particular issue (e.g., trade, military preparedness, European Union). Here we focus on the variables that include a pro- and an anti-position taken on issues relevant to military power or international partnership (Burgoon Reference Burgoon2009; Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018). This allows us to measure the broad salience of a given issue in a party’s platform, as well as to gauge the level of support for or opposition to a given position (e.g., for or against more open trade) by individual party and more importantly for our purposes, by party family.

Our Manifesto measure of “military power” refers to the percentage of total sentences or quasi-sentences in favor of military spending, preparedness, security, and defense generally minus the percentage of statements expressing doubt and criticism of defense spending, military conscription, and the use of military power to solve conflict.Footnote 23 Our “international partnership” support measure is equally broad and inclusive. It refers to the percentage of total sentences or quasi-sentences (single statements) expressing support for general internationalism, free trade (low trade protectionism) and the European Union minus the percentage of (quasi-) sentences expressing opposition to each.Footnote 24 This net measure includes every reference to open markets, international cooperation, and global governance in the Manifesto database.

We use these measures to determine whether mainstream political parties are significantly more supportive of liberal internationalism than political parties located on the far-left or far-right of the political spectrum.Footnote 25 Following many others, we define mainstream parties as those that are considered center-left to center-right ideologically (Huber and Inglehart Reference Huber and Inglehart1995; Mair Reference Mair1997). These include Social Democratic, Liberal, Christian Democratic, and Conservative parties. We classify parties whose ideological positions fall to the extreme left or extreme right as non-mainstream parties or “radical-left” and “radical-right,” respectively (Mudde Reference Mudde2009; Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, Burgoon and van Elsas2017). On the left, these include political parties usually associated with communist or post-communist ideologies (e.g., Spain’s Podemos; Germany’s The Left; Italy’s Five Star Movement). On the right, it includes parties associated with nationalist or populist appeals to nativism, traditionalism, and statism (e.g., France’s National Front; Austria’s Freedom Party; Denmark’s People’s Party).

Figure 4 summarizes the policy preferences of these party families for partnership (left-side) and power (right-side). Summary box plots capture the distribution in support for partnership and power by party type and over time. The sample median for each party type is denoted by white horizontal lines. The dark-shaded boxes represent the bottom twenty-fifth and top seventy-fifth percentile of the interquartile distribution. The “whiskers” in the box plots reflect the smallest and greatest adjacent values, respectively.Footnote 26 The first row of box plots in figure 4 shows the pattern for our core sample of Western countries over the entire period under examination (1970 to 2017). To determine whether the cross-sectional pattern shifted over the decades, figure 4 also breaks the party-type distributions down by sub-period: 1970–1990 (second row of box plots); 1991–2017 (third row of box plots). The patterns revealed in figure 4 are borne out in a fuller regression analysis of all parties (refer to online appendix table A1).

Figure 4 Party platform support for international partnership and military power by party family, 1970– 2017

With respect to international partnership (left-side panels), we see a clear and consistent curvilinear, inverted-U pattern, where radical-left and radical-right parties tend to be less supportive of partnership than are mainstream parties. This is especially true of radical-right parties, which consistently oppose partnership: the sample median party-year is below 0 in all three box plots in figure 4. Radical-right manifestos contain proportionately more anti-trade, anti-EU, anti-internationalism and anti-multilateralism statements than statements in support. By contrast, mainstream parties are more supportive of partnership. As figure 4 indicates, their party platforms are proportionately more positive than negative about free trade, international institutions, and multilateral governance. Moreover, despite many differences over economic and social policy, the mainstream parties disagree only modestly among themselves over whether to invest in international partnership. The key pattern in figure 4 is the inverted-U shape. Significantly, this pattern is stable over time—that is, across the three box plots (from top to bottom). While radical-left parties become more supportive of international partnership after the Cold War, and radical-right parties become more hostile, mainstream parties (Social Democrats, Christian Democrats, Liberals and Conservatives) barely shift.Footnote 27

The story of party support for military power (support for military spending, modernization, or preparedness, minus opposition to each) is simpler. We see a more “monotonic” (rather than curvilinear) distribution as we move from the radical-left, through the mainstream parties, to the radical-right. Radical-left parties’ platforms reveal that they are significantly less inclined to support investing in military power than are mainstream parties. By contrast, radical-right parties are more likely to support investing in military power than most mainstream parties. The only exception are mainstream Conservative parties, which are as bullish on military spending as radical-right parties. As figure 4 indicates, this pattern has not changed much over time. While there is some increase in support for military power expressed in the full-sample averages of each party family, radical-right parties are consistently the most supportive of investing in military power. Conversely, radical-left parties are the parties most strongly opposed to military spending and preparedness.Footnote 28

Our analysis of Western party support for liberal internationalism indicates that the Western consensus in favor of liberal internationalism during the Cold War existed at the level of party politics as well as at the level of government policy. Mainstream parties that made up the West’s “vital center” strongly favored investing in both power and partnership. This pattern has continued during the post-Cold War era. Mainstream parties remain liberal internationalism’s staunchest supporters; radical-left and radical-right parties, dedicated foes. This pattern suggests that Western foreign policies that we associate with liberal internationalism have long rested on the electoral fortunes of mainstream parties. During the Cold War, Western governments and liberal internationalism did, in fact, benefit greatly from this electoral connection. As we show in the next section, this is no longer the case. Liberal internationalism’s vital center is waning.

The Hollowing Out of the Center

During the Cold War, mainstream parties dominated the electoral landscape (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967; Budge and Laver Reference Budge and Laver1992). Even in Europe, where communist parties were competitive, mainstream parties captured, on average, 70% to 75% of the vote during the 1970s and 1980s. The leaders of mainstream parties were well placed in the highest reaches of national government to frame public debate, influence foreign policymaking, and keep nationalist and populist pressures in check (Martill Reference Martill2019). Their dominance all but guaranteed broad and consistent domestic support for Western governments’ foreign policies. At the same time, Western governments’ commitment to liberal internationalism was a source of consensus within Western democracies. Western leaders could advance liberal internationalist policies confident that they would garner the support of a broad cross-section of political parties representing the vast majority of voters. This type of cross-party consensus no longer holds.

In this section, we show that domestic support for liberal internationalism has weakened considerably since the Cold War. Mainstream parties are losing electoral market share to parties on the far-right and far-left that are opposed to liberal internationalism. While many factors have contributed to the decline of mainstream parties, the following analysis indicates that their strong and consistent support of liberal internationalism has become costly to them. In particular, we show that as Western governments’ investment in international partnership deepened, mainstream parties’ hold on voters weakened. The resulting gap between Western governments and mainstream parties’ international commitments and voters’ willingness to support those commitments created opportunities for anti-globalist parties to exploit. This is especially true of parties on the radical-right that have used anti-globalist nationalist rhetoric and platforms to penetrate Western electorates and significantly boost their share of the vote.

We develop these arguments about the decline of the West’s vital center in two steps. The first step focuses on descriptive and aggregated over-time averages for our full sample of Western countries between 1970 and 2017 in terms of our government policy measures of partnership and power, measures of electoral vote shares for mainstream parties relative to radical parties, and measures of voter support for party platforms for and against partnership and power. The second step takes a more inferential approach, focusing on the effects of parties’ electoral strength and voters’ support of partnership and power on Western governments’ foreign policies. We show that at the level of country-years and party-years, changes in the relative electoral strength of mainstream and radical parties affect the level of government support for power and especially partnership. The analysis also indicates that voters are abandoning parties that are most supportive of international partnership and flocking to those parties that are most opposed.

Aggregated Descriptive Trends

The descriptive results for the West as a whole are summarized in figures 5 and 6.Footnote 29 We plot three indicators in the figures. A first indicator (darkest of the lines) measures the level of government support (government policy support) for international partnership (figure 5) and military power (in figure 6), the same measures displayed in figure 2. A second indicator (the broken lines) measures the national electoral vote share for mainstream parties minus the national electoral vote share for radical-left and for radical-right parties (we call this net mainstream vote share).Footnote 30 And a third indicator (in the grey lines) measures party manifesto scores for international partnership and military power weighted by parties’ actual electoral vote share (what we call here weighted manifesto score). We treat this as a country-level proxy for the voting public’s support for liberal internationalism.Footnote 31 In most Western democracies, the larger mainstream parties’ relative vote share, the more legislative backing or capacity we can expect political leaders to have for liberal internationalist policies and positions. Reciprocally, higher levels of voter support for parties advancing liberal internationalist policies should result in stronger government support for those policies.Footnote 32

Figure 5 Western support for international partnership by government and voter, 1970–2017

Figure 6 Western support for military power by government and voter, 1970–2017

The aggregated descriptive patterns for international partnership in figure 5 conform to our expectations. We see that during the Cold War net mainstream-vote share and especially, weighted manifesto score for partnership were leading indicators of Western government policy support for international partnership. That pattern continued until the end of the Cold War. Western governments’ support for partnership continued to rise through the 1990s and into the 2000s. However, during the same period mainstream political parties began to lose electoral market share to radical-right and radical-left parties. This process accelerated in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, as mainstream parties’ share of the electoral vote declined rapidly from one election to the next. Notably, this has not led Western democracies to retreat wholesale from policies promoting greater economic interdependence and institutionalized cooperation, though government support for international partnership has cooled since its peak in the early 2000s. This pattern contrasts sharply with the Cold War era, when Western government support for international partnership increased during most years.

Most striking is the hefty price political parties promoting international partnership have paid with voters. As figure 5 shows, since the early 1990s those parties advocating international partnership (indicated by their weighted manifesto score) have lost significant electoral ground to radical-left and radical-right parties. Indeed, the decline in voter support for international partnership outpaces the dramatic downward trend in electoral support for mainstream parties (relative to radical parties). It also helps us understand the sizeable and growing gap in support for international partnership between Western governments and their voting publics. Government support for policies of globalization, international institutions, and multilateral governance has continued, as has mainstream party support for those policies (refer to figure 4 and also to figure A2 in the online appendix, which tracks party platform support for partnership and power by party family). Yet public support for parties advocating those policies has fallen off sharply since the 1990s, and especially since the 2008 global economic crisis.

The story is quite different when it comes to the West’s commitment to military power, at least since the early 1990s. As figure 6 makes clear, during the Cold War, Western political leaders who invested GDP in military power could do so knowing that they had the support of mainstream parties (though not always their voting publics). This lasted until the collapse of the Soviet empire. Since then, Western investment in military power as a share of GDP has fallen. The decline in Western government support for military spending has been so steady that since 2000, public support for military spending (weighted manifesto score) has eclipsed actual government spending on defense in Western democracies as a share of GDP.Footnote 33 In contrast to international partnership, where Western governments have overreached (exceeded what their voting publics support), the reverse is true when it comes to investing in military power.

Detailed and Inferential Patterns

To assess how systematic these relationships between policy, parties, and voters are we also ran a series of regression analyses.Footnote 34 The key findings are summarized in figure 7, with full results of the regression analyses detailed in the online appendix (table A2). The left-side panels in the figure display the results for Western government policy support for international partnership; the figure’s right-side panels summarize the results for Western government support for military power. The upper panels describe the main results for mainstream parties (net mainstream party vote), while the lower panels describe the results for voters (weighted manifesto score). Each panel displays the counterfactual predicted levels of government policy support for partnership and for power.Footnote 35

Figure 7 Effect of mainstream party strength and voter foreign policy preferences on Western government policy, 1970–2017

We see that the correlation between mainstream parties’ electoral strength and our two policy measures for partnership and power is positive and statistically significant. The stronger mainstream parties are electorally, the more likely Western governments are to invest in both partnership and power—that is, in liberal internationalism.Footnote 36 The bottom half of figure 7 displays the effects of voter support for party manifestos advocating liberal internationalism on Western government policy. Here too we see that Western governments’ support of international partnership has been generally responsive to public support.Footnote 37 By contrast, voter support for increasing military power has no discernible effect at the level of government policy.Footnote 38

The inferential analysis summarized in figure 7 makes clear that the West’s commitment to liberal internationalism rested on broad cross-partisan political foundations—foundations that have long since fractured. Mainstream political parties have weakened considerably, as has Western voter support for mainstream parties’ liberal internationalist platforms and agendas.Footnote 39 This is especially evident in the case of voter support for international partnership. Figure 5 shows that it is here, in the government policies and mainstream-party platform positions aimed at promoting greater international openness, institutionalized cooperation, and multilateral governance, that the gap between Western leaders and their citizens is most acute. It would also appear to be where Western political leaders have so consistently and profoundly misjudged the depth of voters’ alarm and anger over the economic and sovereignty costs of liberal internationalism.

To get analytic leverage on this question, we used a more fine-grained level of analysis, relying on party-year as opposed to country-year (as in figure 7). We wanted to see whether a given party’s platform position on international partnership and military power before a national election improves or hurts its performance (vote share) in the election. On the basis of the aggregated descriptive trends in figure 5, we expected that all things being equal, political parties that were more supportive of international partnership would be punished at the ballot box, while parties more opposed to partnership would be rewarded. This is, in fact, what we find in simple models pooling all parties, countries, and years in the available Manifesto data (1970–2017).Footnote 40 While a given party’s support for military spending and preparedness tends to correlate insignificantly with that party’s share of the national vote in the subsequent election, a party’s support for freer trade, international cooperation, and multilateralism correlates significantly and negatively with its subsequent electoral performance. In general, parties supporting international partnership lose votes; by contrast, opposing partnership increases vote share. This pattern also applies for the entire 1950–2017 time period, and the electoral rewards for parties opposing partnership have only increased since the end of the Cold War.

Figure 8 breaks down the results of the same estimates for how platforms correlate with subsequent vote shares by party family (interacting party platforms by party-family dummies).Footnote 41 The black dots in the figure represent the coefficients for the predicted effect of net party support for partnership and power on party vote share. In the case of international partnership (left-side panel), we see that the predicted effect is negative for all five party families. However, with exception of radical-right parties, the negative effect is not statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.Footnote 42 Simply put, Western voters are not rewarding political parties that favor international partnership, but they are rewarding parties that oppose it. By contrast, we do not see the same pattern between mainstream and radical-right parties in the case of military power (right-side panel). While we see variation across party families, the correlations between party platforms and vote share in the left-side panel are not statistically significant.

Figure 8 Effect of party support for international partnership and military power on vote share by party family, 1970–2017

The results in figure 8 and the underlying estimates are suggestive. Mainstream parties appear to be losing market share because they favor international partnership; radical-right parties appear to be gaining votes by running on anti-globalist platforms. The basic statistical patterns we see in the Manifesto data do not allow for strong causal claims, however. Moreover, there is no shortage of alternative explanations for the dramatic rise of radical-right parties in recent years (e.g., Kitschelt and McGann Reference Kitschelt and McGann1997; Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Bolleyer Reference Bolleyer2013). What the patterns revealed in figure 8 do suggest is that international partnership no longer affords mainstream parties the electoral advantages it once did, and that for their part, radical-right parties have found a powerful weapon in anti-globalism to attack Western democracies’ vital center.

Conclusion

The West has overreached. A large and widening gap has opened between the West’s international ambitions and its domestic political capacity to support them. Contra much current public discourse, this process did not begin in 2016 with Donald Trump’s election and the British vote to leave the EU. It took shape a quarter-century ago in the aftermath of the Cold War and at the height of Western triumphalism. In the ensuing years, as Western leaders invested in ever-greater internationalization, domestic support for international openness, institutionalized cooperation, and multilateral governance steadily weakened in Western party systems and electorates. Mainstream parties lost ground to globalization’s opponents on the political left and right. The gap between the West’s foreign policy agenda and domestic support widened. Political entrepreneurs like Trump, Boris Johnson, and others found a way to exploit this gap for electoral gain.

In retracing the Western liberal international order’s trajectory from the height of the Cold War in the 1970s through the 2008 global economic crash to the current crisis, we have shown several things. The first is that for decades mainstream political parties were the bedrock of the Western liberal international order. As the vital center, they were not only a bulwark against political extremism from the political left and political right during the Cold War. Mainstream parties were also the building blocks upon which the West’s shared commitment to liberal internationalism rested. Western leaders could advance liberal internationalist policies knowing that those policies enjoyed the backing of a broad cross-section of political parties representing the majority of voters. As we have shown here, Western political leaders can no longer assume such levels of domestic support. The center has not held.

We have also shown that the populist backlash against liberal internationalism we see across the West today has deep roots. Anti-globalist domestic pressures have been steadily rising in Western democracies since the 1990s. While many factors have contributed to anti-globalism, Western governments bear their fair share of responsibility. As Western governments invested in ever greater international openness and pooled more and more authority in multilateral institutions and governance arrangements, increasing numbers of Western voters grew resentful of the costs in economic security and national sovereignty. The chickens have now come home to roost. This has proved costly, and not only for Western mainstream parties. China and Russia have been quick to seize on the erosion of domestic support for Western international leadership to promote alternative illiberal visions of politics and society and to expand their spheres of influence (Snyder Reference Snyder2018).

In tracing the roots of the backlash against liberal internationalism, we have also shown that today’s anti-globalist pressures in the West owes more to the breakdown of embedded liberalism than the headlong pursuit of “liberal hegemony,” as some have argued (Mearsheimer Reference Mearsheimer2018; Walt Reference Walt2018). While the West’s pursuit of expansive liberal goals like democracy promotion have undoubtedly contributed to voter disillusionment with liberal internationalism, we have shown that domestic disenchantment set in well before Western efforts to expand the liberal international order to the Middle East, former republics of the Soviet Union, and elsewhere. As the steady rise in domestic opposition to trade liberalization, institutionalized cooperation, and multilateral governance since the 1990s indicates, the overreliance on these foreign policy tools has been the principal source of the widening gap between Western governments and their publics over foreign policy.

These developments did not occur in a geopolitical vacuum, however. Our analysis underscores the critical role that the Cold War, the Soviet collapse, and geopolitics more generally, has played in shaping party politics across the West. The disappearance of a common geopolitical threat after the Cold War opened up the domestic political space for political parties on the political left and right that were marginalized during the Cold War, and that refused to subordinate local grievances and claims to wider post-Cold War international geopolitical logics. Mainstream parties, for their part, became less responsive to mass publics. There is substantial literature documenting the toll that economic globalization in particular has taken on Western party systems and especially, mainstream parties (e.g., Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Rommel and Walter Reference Rommel and Walter2018). Comparable systematic empirical research on how geopolitical imperatives or their absence contributed to party dynamics in Western democracies is clearly needed. Our analysis offers support for explanations of anti-globalism and populism that stress the breakdown of the compromise of embedded liberalism that kept economic security and sovereignty costs in check (Burgoon Reference Burgoon2009; Rodrik Reference Rodrik2011). But the timing of the West’s turn from liberal internationalism to globalism also suggests that during the Cold War, bipolar superpower rivalry did have a disciplining effect on party politics in the West (Kupchan and Trubowitz Reference Kupchan and Trubowitz2007).

The West now faces a conundrum. The liberal world order hinges on the ability of the United States, Germany, France, and other advanced democracies to lead and support it. However, the more these democracies invest in liberal-order building, the more divided and polarized they risk becoming. Two strategies for resolving this tension are likely to dominate the coming foreign policy debate in Western capitals. One option is for Western democracies to adopt more limited expectations about what can be achieved internationally and to rely on more efficient and less costly means (e.g., Allison Reference Allison2020; Lind and Wohlforth Reference Lind and Wohlforth2019; Posen Reference Posen2014). An alternative strategy is for Western democracies to return to the principles of embedded liberalism by making international markets and multilateral institutions more responsive to the desires of national electorates and more supportive of policies aimed at national cohesion (e.g., Colgan and Keohane Reference Colgan and Keohane2017; Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2018; Snyder Reference Snyder2019).

Given the intensity of the domestic pressures now confronting Western democracies, the problem must be attacked from both sides simultaneously. Internationally, Western leaders need to find ways to reduce sovereignty costs by making multilateral governance structures more democratic and flexible (DeVries and McNamara Reference De Vries and McNamara2018). However, a strategy that relies solely on restructuring international commitments will not be sufficient to restore domestic consensus and legitimacy. It will also be necessary for Western governments to renew and update their commitment to inclusive growth and economic security for their citizens. This will require innovation in domestic growth regimes centering on strategic localization of productive activities, investment in human capital, quality-of-life supports, and environmental sustainability. Some of these processes are already underway in some progressive internationalist policy initiatives within the OECD. Yet given the depth of the anti-globalist backlash, far more is needed if Western democracies hope to close the gap between their international ambitions and what their citizens will support.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720001218.