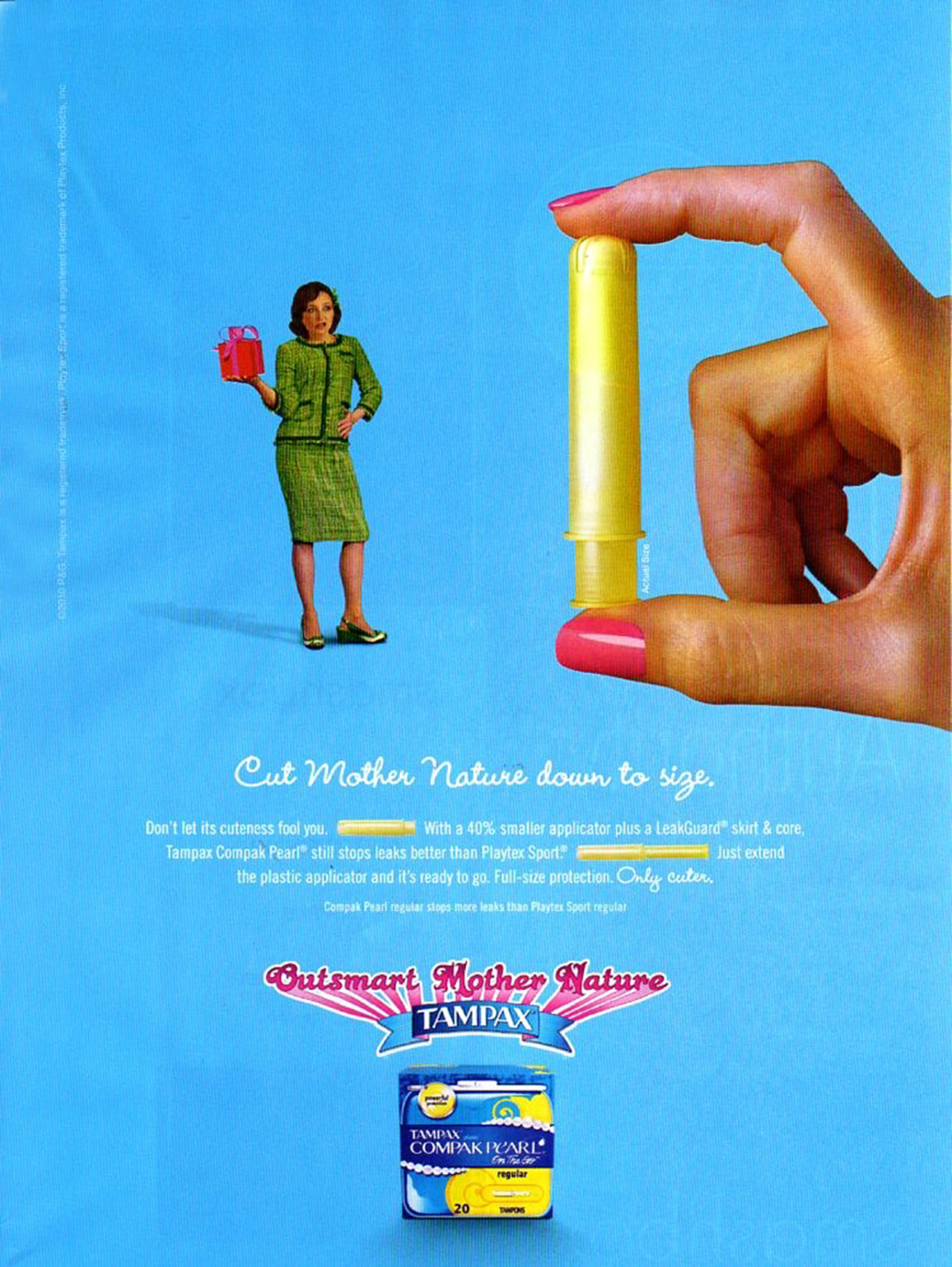

The Mother Nature campaign provides a vivid example of the breakdown between cultural production, activism, and corporate messaging in the 2000s and is explored as it relates to work by Frederick Jameson, Deborah Root, and Nancy Fraser on the blurred boundaries of activism and commerce. This campaign is an early example of the benefits of using humor, ironic gendered narratives, and social media to sell menstrual products, as opposed to previous campaigns, which focused on technical details and traditional media. It also employed celebrity to great effect, through tennis player Serena Williams. Thus, it is justifiable to focus on this single campaign, because it foregrounds the feminist trend, seen in the “femcare” sector ever since, and provides evidence for how gendered narratives still dominate the commercial side of menstruation, despite claims of doing the reverse. A close reading of both the campaign and its behind-the-scenes gestation provides evidence that gender dynamics was at the heart of the branding of Tampax, both internally—in terms of the largely female Leo Burnett team who created the campaign—and externally—in the iconography of the Mother Nature advertisements (Figure 1).

Figure 1 “Cut Mother Nature down to size.”

Methodologically, this article uniquely uses interviews with creative executives from Leo Burnett and the actress involved in the campaign. In contrast to previous histories written about menstrual product branding, this paper adds the voices of the creators to the analysis. This methodological step further complicates perceptions of menstrual product branding, exploring how feminist and capitalist views and aims exist side by side. For scholars of gendered narratives in marketing, this case study provides evidence about how corporations such as Procter & Gamble (P&G) control creative strategies, how brands like Tampax reinvent themselves, and how women in advertising continue to balance their feminist convictions with their work.

The article first discusses the context of the campaign in the decade leading up to its creation and introduces the reader to the relevant sources and historiographical issues. Second, the paper discusses the problems facing Tampax in the 2000s and the creative efforts made by Leo Burnett to capture consumer interest. Third, it surveys case studies from the campaign in order to give the reader a sense of the varied, vast, and, at times, uneven Mother Nature campaign and its many platforms. Finally, the paper examines Mother Nature’s economic and cultural impact, its surprising abrupt cancellation, and its legacy in femcare advertising.

Beyond Corporate Sources

For decades, historians of corporate North America have identified the problem of access to documentation as a methodological problem.Footnote 1 P&G’s archives at the corporation’s headquarters in Cincinnati, Ohio, are no exception.Footnote 2 In lieu of limited access, historians can draw on the official Tampax histories commissioned by the original owners, Tambrands Inc., and the current owners, P&G: Rising Tide and Small Wonder, respectively. Footnote 3 However, these sources focus on the official corporate narratives of success and business advancement. None include interviews with the creators of advertising campaigns.

Information about P&G’s corporate view of Tampax is available in annual reports (published on their website) and via the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval tools.Footnote 4 Annual reports from the 2000s give the impression that Tampax in particular, and femcare generally, has not been a priority for P&G until very recently. Annual reports (and their appendixes) from the years the Mother Nature campaign ran mention Tampax on average two times annually, and in these instances, the brand was linked to larger categories, such as beauty or, later, health and well-being. This makes the task of understanding a P&G brand a challenge, although other sources, in particular market research, provide some insight.

Beginning in the 1920s, the relatively new menstrual product businesses of North America sought advice on how best to communicate the perceived sensitive nature of their goods.Footnote 5 Because of the taboo surrounding menstruation, marketing research provided valuable information to product manufacturers regarding what consumers wanted from advertising. Market research companies such as the World Advertising Research Centre (WARC), Passport, and Mintel have since written several reports about the menstrual product sector.Footnote 6 WARC helpfully provides some analysis of advertising case studies, including the Mother Nature campaign, which is described in detail by the anonymous author and has been a useful, if not entirely reliable, source.Footnote 7 Menstrual product market research provides insight into what sells in the sector and can help sort corporate claims of success from actual financial and cultural impact gains. However, the absence of any input from advertisers, models, or actresses involved in branding means that a crucial component has gone unexplored.

For all of these reasons, it is hard to critically examine the behind-the-scenes creation of P&G branding. This is why the methodology of interviewing non-P&G staff directly involved in the Mother Nature campaign provided revealing data. For this research, interviews were conducted with the two executive creative directors of the Mother Nature campaign, Anna Meneguzzo (Leo Burnett, Europe) and Rebecca Swanson (Leo Burnett, U.S.), and the actress who performed the role of Mother Nature, Catherine Lloyd Burns.Footnote 8 Historians of menstruation have written about advertising, but have not included the individuals who created it, such as creative professionals in advertising agencies or actresses and models in campaigns.Footnote 9 The introduction and analysis of these voices in this article provides a unique insight and reinserts the agency and perspectives of the women behind the campaign. Inclusion of these voices, however, was also challenging. The interviewees were all situated between corporate, professional interests and their own convictions and agencies as women, people who menstruate, and, sometimes, feminists. The dual challenge is to listen to and contextualize their work and experiences, which represent key data in this survey.

Taken together, these sources provide a framework for understanding why the campaign succeeded as a cultural artifact, and how gender and corporate influences intersected with the Mother Nature campaign.

Critical Menstrual Studies

By the early 2000s, a substantial and varied historiography of menstruation was available, some of which was cited by the interviewees. In the beginning of the twentieth century, scholarship about the menstrual cycle was dominated by the fields of medicine, particularly gynecology and obstetrics.Footnote 10 The medical and clinical interest in menstruation has deeper historical roots than the previous century, but for the purposes of this article, it is useful to remind ourselves that it was the critique of these science-based patriarchal treatises that first galvanized a varied set of writers and thinkers to question the menstrual status quo in the mid- to late twentieth century.Footnote 11

During the 1970s, menstruation became one of many topics that concerned the women’s rights movement in the United States (and elsewhere). For example, the publication of the feminist self-care classic Our Bodies, Ourselves provided medical knowledge in laywomen’s terms.Footnote 12 Echoing the authors of Our Bodies, Ourselves, the first critical histories and explorations of menstruation shared a dislike of the menstrual product industry and advertising.Footnote 13 Journalists such as Gloria Steinem and Karen Houppert began writing about menstruation in the same decade. Steinem approached the topic with humor in the Ms. magazine essay “If Men Could Menstruate,” a short essay arguing that in a world where genders were assumed to be stereotypically feminine or masculine, menstruating men would make bleeding a competition about having the largest flow and the cycle would become a status symbol.Footnote 14 Houppert, starting her investigation in the U.S.-based news and cultural paper the Village Voice, approached the topic as a journalist, providing an early interrogation of the industry, including an analysis of advertising and a detailed argument about the shortcomings of tampons.Footnote 15 Historians of tampon advertising have identified how corporations were aware of the sensitive cultural issues associated with tampons, notably the issue of virginity, and how early advertising often presented tampons as an empowering, modern, and moral choice.Footnote 16 As will become evident in the discussion of the Mother Nature campaign, Tampax has a long history of engaging with the women’s rights movement and appropriating its messages.Footnote 17 For example, the first belt-free pad, New Freedom (Kimberly-Clark), used models in clothing reminiscent of the women’s liberation and hippie movements and promised freedom and empowerment. Overall, the 1970s can be seen as a revolutionary time for menstrual activism, culture, and discourse, while the corporations that sold menstrual products emerged from the decade relatively financially unharmed.

In the next decade, the World Health Organization’s survey of international attitudes toward menstruation revealed global dissatisfaction with commercial brands, as well as a pervasive taboo.Footnote 18 Most of the early 1980s, however, were dominated by the debate surrounding toxic shock syndrome (TSS), which was linked to P&G tampon brand Rely, of which more later.Footnote 19 To a lesser degree, debates about the environmental consequences of flushing disposable products, about whether or not premenstrual syndrome (PMS) should be diagnosable, and the link between menstruation and HIV/AIDS continued during the decade.

My interviewees either identified as feminists or expressed clear feminist views, and all were aware of the Second Wave feminist interest in the menstrual taboo. To a lesser extent, environmental and health issues related to the menstrual cycle were also brought up by the interviewees. They were also aware that critique of the manufacturing and advertising of products remains of interest to the wider public, exemplified by the increase in new books aimed at a wide readership and invested in the idea that the industry is problematic and sexist.Footnote 20 The interviewees often reflected on their complicated role as supporters of women’s rights versus advertisers of gendered products and expressed unease as these blurred boundaries became apparent in the Mother Nature campaign.

With this extensive and important critical menstrual historiography in mind, this article introduces the voices of the creators in the analysis of menstrual product advertising and branding, while also showing how the long-standing debates about gender tropes in advertising and corporate culture remain.

A New Time of Crisis

With a history of gendered advertising built around promises of modernity, hygiene, and femininity, Tampax brand managers could have fallen back on tried-and-tested stereotypes that had worked during other public and fiscal crises. The 2000s were by no means the first (or last) time that P&G’s interest in menstruation would be challenged, and a reminder of the challenges facing Tampax at the time can help better contextualize why the Mother Nature campaign was both a departure from old tricks and a reinvention of stereotypes.

Since the 1930s, the “femcare” industry has experienced an astronomical growth as women in North America and Western Europe switched to non-reusable products from washable and reusable options, thus creating a new market and consumer base consisting of women of reproductive age.Footnote 21 Around the millennium, however, the sector was coming to terms with a significant slowing of pace, resulting in a “sluggish tampon market” by 2007, although Tampax never dipped lower than an impressive 49 percent of the market.Footnote 22 At the same time, the popularity of menstrual suppression techniques was on the rise in the Western markets that Tampax relied on most, presenting an existential threat to all menstrual product manufacturers.Footnote 23 P&G was also troubled by advertising displays from its competitor, Playtex. Playtex, originally introduced by the International Latex Corporation in 1960, was owned by Hanes Brands by the 2000s, a company with a smaller brand portfolio and seemingly endless energy directed at attacking Tampax. Campaigns on television and in magazines detailed Playtex’s superior comfort, absorption, and “discreetness.” The plastic applicator was described as more comfortable and modern, and the product was shown to excel in soaking up (blue, as advertising standards forbid red) liquid as compared to Tampax.

For all these reasons, the early 2000s were not a period of growth for the menstrual product industry, which was increasingly stuck in a saturated market. For P&G, however, it was a time of innovation in other ways, as it began to come to terms with new acquisitions such as Tampax. Established in 1837 by William Procter and James Gamble, and focused primarily on cleaning agents, P&G grew into a multinational corporation in the late twentieth century. P&G had a reputation for pioneering branding techniques with great success, with images of the American housewife becoming a symbol for its cleaning brands, for example.Footnote 24 In 2000, a key shift in P&G leadership ushered in a new enthusiasm for branding within the corporation, spearheaded by chief executive officer Alan George Lafley.Footnote 25 Under his leadership, which spanned the 2000s, P&G experienced a growth in sales, cash flow, and annual core earnings per share. The corporation gained a reputation for being consumer driven and externally focused, with an increased interest in innovation and risk-taking, although Lafley and his group of innovators do not seem to have taken much interest in the Tampax brand publicly.Footnote 26

How, then, to update and refresh menstrual product branding strategies for a new millennium? Theorists of the late twentieth century note how culture and economics became ever more entangled at this time. Analyst of postmodernism and late capitalism Frederick Jameson defined the era from the late 1980s onward as one in which imperialist, monopolistic structures gave way to multinational corporations like P&G, which in turn coincided with a turn away from sincerity in popular culture.Footnote 27 Postmodern tropes, such as pastiche, blasé, and irony, seeped into the culture not only via television and the Internet, but also through corporate co-option of this new tone, including within menstrual product advertising.Footnote 28 In what both Jameson and postcolonial theorist Deborah Root discuss as “a cannibalistic turn,” commercial interests collapsed the sincerity and goals of activism, culture, and art and became memes and phenomena in themselves.Footnote 29 Historian of advertising and gender Jean Umiker-Sebeok pointed out that advertising changed slowly in the 1980s, but the pace increased as the millennium approached and went into hyperdrive with social media platforms and their potential for advertising to specific groups in the 2000s.Footnote 30 Soon, it became difficult to see what was real culture and what was advertising, exemplified by the Mother Nature campaign’s sometimes unclear affiliation with the Tampax brand and P&G and its influence on popular culture as well as profit margins.

This collapsing of capitalist and activist goals emerges strongly in the story of Mother Nature. As detailed earlier, the industry has always conducted its own research into the behavior and beliefs of its consumers, but the post-millennium decade marks an increased use of external material and research by the industry. In this case, interviewees repeatedly cited critical feminist literature in their answers. The willingness of corporations and advertisers to interact with, process, and use critical literature about themselves became a cornerstone of campaign building for the creative Tampax team. P&G was part of the trend of appropriating feminism for commercial means during these decades, as identified by journalist Andi Zeisler in We Were Feminists Once. Footnote 31 In Cashing in on the Curse, Karen Houppert argued that the industry had been appropriating feminism for a long time and that it continued to do so as feminism changed.Footnote 32 The first decade of the new millennium was rife with examples of this, notably the Dove soap brand (Unilever) Real Beauty campaign featuring women who were not models. Despite later ridicule of such blatant attempts to connect with feminist literate viewers, advertising that interacts with social justice and identity issues continues to “go viral.” Furthermore, social scientists have sometimes also worked for the industry, blurring the lines between independent and market research even further. As recently as 2016, social scientists Timothy de Waal Malefyt and founder of consumer research consultancy Cultural Connections LLC, Maryann McCabe, published their research for pad brand Stayfree (Energizer in North America, Johnson & Johnson internationally) in Consumption, Markets and Culture. Footnote 33 Consumer researchers, anthropologists, historians, and medical professionals have contributed vast amounts of data and analysis to the industry over the years, resulting in a reflexive, culturally literate, and self-aware sector. How, then, to make sense of this intersection of knowledge about and production of stereotypes by the industry?

In her contemporaneous analysis of feminism in late capitalism, cultural theorist Nancy Fraser pointed out that corporations were not shy about offering “empowering scripts,” and that the co-opting of social justice messages, and especially feminism, was speeding up in the decades around the new millennium.Footnote 34 For scholar of gender and work Kathi Weeks, this acceleration caused a mirage for working women, in which the seductive but impossible option of “having it all” resulted in stress, more work, and, fundamentally, benefits for multinational corporations.Footnote 35

In summary, a perfect storm consisting of menstrual suppression, an aging population, and an aggressive competitor, pushed P&G to take action in a time when changes in culture, media, and capitalism meant that P&G branding itself sought rebranding. CEO Lafley later reminisced that those were the days when creativity and branding became important for P&G again, after some decades of playing it safe and family friendly.Footnote 36 How, then, to deal with this new crisis and gain ground in an already saturated market?

Marketing Tampons in Times of Trouble

The options for how to market menstrual products have expanded in the last thirty years, specifically due to the relaxation of advertising standard guidelines and the emergence of new social media platforms.Footnote 37 The basic gender binaries in advertisement have, however, remained visible since sociologist Erving Goffman first conducted his visual review of marketing in the 1970s.Footnote 38 Goffman included a reference to New Freedom (Kimberly-Clark) pad advertising to illustrate how young female models were posed to suggest aspirational youth and liberation. He argued that the “commercial realism” of gendered advertising was simply another ritual that reflected, but never accurately portrayed, society. With their close ties to women and, by extension, whatever represented femininity at the time, menstrual products share many characteristics with other categories of goods that have used gendered stereotypes in order to sell. P&G was itself fundamental to the creation of the female homemaker trope in its advertisement for soap brand Tide, but the campaigns were often created by women in advertising rather than the male-dominated corporation.Footnote 39

The idea that gender tropes were only dreamed up by male executives is neither correct nor helpful, as it erases the work women have done to create representations of womanhood. For example, in this case study of Mother Nature, concepts of gender remain binary and fixed, in stark contrast to contemporary debates about gender as performance and hierarchy and in terms of historical narratives.Footnote 40 The interviewees, however, were wary of historical critiques of gendered advertising and saw themselves as continuing a long battle for equity in advertising and menstrual discourse.Footnote 41 They also described their work as radically different from the P&G team and its corporate interests, explaining that when the creative team tried to challenge gender binaries, P&G protested.Footnote 42 While a surface-level reading of the Mother Nature campaign reflects clear gendered tropes, the experiences of the women behind the scenes show efforts to challenge the status quo and protest against commercial realism.

Another key factor influencing the campaign was timing. Mother Nature launched during the prelude to the international financial crisis in 2008 and ran for the duration of the chaos. CEO Lafley was not particularly worried, commenting in The Independent that “virtually every product that P&G sells is not losing frequency of usage.”Footnote 43 P&G had benefited from a steady increase of disposable consumer income in the 2000s, especially among women.Footnote 44 Tampax was not the cheapest tampon on the market, but its brand recognition and consumer loyalty was so strong that debates about lowering the price were not considered. U.S. consumers in particular preferred the applicator-type tampon, rather than the digital non-applicator form popular in Europe, which had to be inserted using one’s fingers, meaning more direct contact with blood and the body. More importantly, consumers had also forgiven, forgotten, or never heard of the TSS crisis of the 1980s, when P&G’s first tampon venture ended in disgrace after the Rely brand became linked to the lethal disease.Footnote 45 This episode resulted in a recall of Rely and a drop in tampon sales across all (international) brands.Footnote 46 P&G dealt with TSS by briefly abandoning the market and seeking out a more trusted brand.

P&G bought Tambrands Inc. seventeen years after the TSS crisis and has since produced, marketed, and sold Tampax internationally.Footnote 47 After the acquisition, campaigns were rolled out on television and in print, featuring young (usually, but not exclusively, white) models, close-ups of the products, and a voice-over explaining that Tampax was a safe choice. Narratives were built around potentially embarrassing scenarios like wearing white clothing or going camping, with taglines such as “Made to Go Unnoticed.” The marketing formula was thus a combination of information and attempts at connecting with the consumer on an emotional level. Humor was used only if it strengthened the core message of the product’s leak-proof promise, and relied heavily on gendered narratives. For example, in a 2005 television commercial, female students are caught passing items in a classroom.Footnote 48 When the male teacher asks to see what he assumes to be a note, a girl passes him a wrapped tampon. The teacher is confused about the item, as are the boys in the class, whereas the girls grin at each other knowingly. The tone is humorous, and fundamentally underlines the Tampax brand promise of hiding menstruation (and menstrual products) from society, in particular from men and boys, who are portrayed as innocent and unintelligent. Surveying this trope, medical sociologist and nurse Annemarie Jutel argued that the focus on solving the menstrual “debility” problem in such campaigns would not empower women, but rather crystallized social beliefs about female biology further.Footnote 49 In other words, P&G was not choosing creative advertising strategies for Tampax at the beginning of the millennium, and the new leadership did not make the product a focus for innovation. Thus, the brand was both blessed and cursed with a reputation for stability.

P&G’s careful attitude to marketing Tampax in the 2000s was perhaps understandable, as the brand had been a category leader for so long. Furthermore, the corporation’s reputation as a menstrual product manufacturer was still on shaky ground post-TSS, and tampons lagged far behind in the overall menstrual product category, where panty liners and pads dominated the market after TSS.Footnote 50 The P&G pad brand Always had already been facing growing competition from new pad brands, a sign that the overall menstrual product category was diversifying and expanding slightly, notably with the reemergence of the nineteenth-century technology of menstrual cups.Footnote 51 International sales were also slowing, as Asian corporations like Kingdom Marketing Services and the Unicharm Group gained ground.Footnote 52 In addition, Kimberly-Clark had changed the packaging of Kotex products from pastel colors to black in an industry first, signaling that competitors were willing to take risks with packaging, if not advertising. The combination of increased international competition and the market saturation of tampons meant that P&G had little to gain from innovating Tampax, whereas competitors saw options for making a big impact in this stagnant product category. Rebecca Swanson, the Leo Burnett creative executive working on the U.S. side of the Mother Nature launch, recalls this period as a time when she was watching others break boundaries: “We were crushed, we wanted to do that but weren’t allowed.”Footnote 53 The simmering unease already detected by the (largely female) advertising and branding teams involved in Tampax branding reached a boiling point with Playtex’s entrance into the market and would soon be difficult for the P&G leadership to overlook. Setting out to “regain leadership and fight back by differentiating ourselves from the competition,” the Tampax team considered its options in 2007.Footnote 54 P&G decided to listen to the creative team at Leo Burnett first.

The Leo Burnett Team

P&G had a long-established relationship with the Leo Burnett advertising agency, including collaborations on previous Tampax campaigns.Footnote 55 The company was founded by Leo Burnett in 1935 and remains one of the largest in the world, making international campaigns like Mother Nature possible. Its philosophy is based on creativity and risk-taking, a combination that has resulted in the transformation of brands such as McDonald’s and Kellogg’s into household names, and helped entire industries, for example, cigarettes, thrive despite decades of increased consumer media literacy and skepticism. The rethink of Tampax branding in 2007 also proved beneficial for the agency, as the total media expenditure budget was unusually large at around $15 million, and the campaign involved work for Leo Burnett employees across North America and Europe.Footnote 56

P&G had three clear priorities for the campaign: to increase brand value through “emotional equity with tampon consumers,” to increase volume share by 5 percent, and to create a brand shift from “Playtex loyalists and convert them to the Tampax Pearl franchise.”Footnote 57 This specific focus situates Tampax’s strategy in the late-capitalist corporate zeitgeist that includes aspirational lifestyle messages and a focus on the individual.Footnote 58 The objectives would have sounded strange to earlier tampon advertisers, who sought first and foremost to inform their consumers and dispel myths by creating marketing that rarely mentioned menstruation by name. The new options presented by YouTube and Facebook meant that P&G’s goals could be reached in a direct, cheap, and international way, bypassing the strict advertising standards that Tampax had always been hostage to in traditional media outreach.

Leo Burnett employed its extensive global reach to create an international campaign. The work was led by two creative directors: Anna Meneguzzo in Italy and Rebecca Swanson in Chicago. Together, they led an international team dominated by women. Meneguzzo and Swanson had worked with the Tampax brand and P&G before, and used their experience in the femcare area to push for a more original approach to the new campaign. The Mother Nature concept was presented alongside “Zack,” a campaign idea featuring “a story of a boy with a vagina” who suddenly had to deal with menstruation, but the idea “made P&G nervous as hell.”Footnote 59 The corporation’s response to the proposed Zack campaign video, which would go on to win a Clio Hall of Fame Award, signaled to the Leo Burnett team that P&G wanted creativity only within certain boundaries. This had happened before, when P&G hired the Benenson Group to analyze Leo Burnett’s femcare work. The group was a strategic research consultancy usually involved in advising political leaders, and it had explained that an earlier Tampax idea, “Advertise Your Period” (built around the idea that because Tampax keeps menstruation secret, you would have to announce it if you wanted someone to know), would permanently ruin the equity of the brand.Footnote 60 The issue of getting around the P&G executives (and, at times, the Benenson Group) meant that the creative team was somewhat restricted in their ambitions for the campaign from the start.

Meneguzzo explained in an interview that femcare advertising is challenging because of the general rejection of the category as disgusting and feminine.Footnote 61 She argued that it was difficult to communicate a straightforward campaign about menstruation and that the dominance of men in advertising did not help.Footnote 62 Because male creative directors generally shunned the category, she explained that women were often the only ones willing to work in the “pink ghetto of femcare.”Footnote 63 This created a promotion problem for women in the category, because femcare marketing rarely wins advertising awards (compared with the bigger-budget cars and alcohol ads) and thus prevents women from progressing in their careers.Footnote 64 As historian of business Kathy Peiss has pointed out, business history itself has tended to overlook the corners of the industry dominated by women, and listening to businesswomen and female creative executives challenges us to create a more elaborate narrative.Footnote 65 While starting work on what would become the Mother Nature campaign, Meneguzzo and Swanson were both acutely aware and tired of the professional confines inherent in femcare.

However, Meneguzzo found that working on the topic of menstruation became increasingly fascinating, and she started developing a critical understanding of menstrual discourse based on conversations and reading. Soon, she had a dream of “making menstruation cool” and also contributed to an Italian book about menstrual discourse.Footnote 66 By 2015, her goal would become reality as a flood of popular culture and mainstream media responses to menstruation appeared. But in 2007, Meneguzzo and her colleagues were still working within strict frameworks where creating advertising for menstrual products was considered a challenge. Meneguzzo found a kindred spirit in Swanson, and the two women set out to challenge each other and Tampax, within the confines of the pink ghetto.Footnote 67

The Big Idea

As with most large campaigns, Leo Burnett’s research department began the project by commissioning market research. The core idea for the campaign came from an analysis of how the “tampon mindset” was different from the “pad mindset”: “It takes a conscious decision to insert a tampon into your body.… It’s somehow bolder.”Footnote 68 By focusing only on tampon use, the team was not seeking to reach everyone, and instead “defined the target consumer” based on the archetype of the “Alpha girl.”Footnote 69 This archetype was taken directly from child psychologist Dan Kindlon’s book Alpha Girls: Understanding the New American Girl and How She Is Changing the World. Footnote 70 Kindlon’s influential 2006 research presented young American women as more assertive, bold, and ambitious than previous generations, and was in turn criticized for presenting a postfeminist model of girlhood that did not deal with systematic or historic gendered inequality.Footnote 71 The Leo Burnett team used the Alpha girl as an aspirational goal for their potential consumers, rather than assuming that women would identify with her directly. Meneguzzo and her colleagues sought a “bold attitude” for women who were unapologetic toward menstruation, because first-time tampon users are usually older teens or adult women.Footnote 72 They asked themselves how they could dramatize periods for people who did not care, or did not want to care, about menstruation.

The idea of personifying the monthly cycle as Mother Nature was developed as a way to get consumers to pay attention to menstruation: “The Big Idea [was that] Mother Nature is a b*tch! [sic.]” (Figure 2).Footnote 73 She would be so annoying, abrasive, loud-mouthed, interesting and powerful that even teenagers would have to pay attention. Her enemy would be the Alpha girl, who viewers would aspire to be:

Mother Nature was the perfect enemy. Nature behaves sometimes as a stepmother rather than a mother: it’s an acknowledgement that a more realistic—less romantic?—person like our bold girl could easily get to. More importantly, the life stage when our girls are deciding to use a tampon is exactly the one when you fight with your mother. You know she has good intentions, yet she cannot understand you and your desire for freedom.Footnote 74

Figure 2 “Don’t let Mother Nature interrupt your dreams.”

The core narrative revolved around a duel between Mother Nature and her daughters. The archetype for this duel was “‘deity vs human’ or else ‘David vs Goliath’: a cunning yet insightful way to make a big fuss out of a topic that would’ve gone otherwise neglected.”Footnote 75 Elevating the idea beyond embarrassment and into the realms of epic, godly fights, menstruation would become a battleground fought between a goddess and women.

In addition to the attention-grabbing lead character, the creative team focused on introducing humor into the campaign. Leo Burnett is hardly the first to observe that menstruation offers many opportunities for jokes, puns, creative euphemism, and symbolism. Interviewees referenced Gloria Steinem’s “If Men Could Menstruate” as a particularly successful work that balanced body politics and fun. Since Steinem’s 1970s article, there has been an increase in creative and funny responses to menstruation, including podcasts, zines, rallies and “bleed-ins,” tampon costumes, and art projects.Footnote 76 However, such examples were all fundamentally rooted in political body activism, whereas the Mother Nature campaign largely stripped the reproductive justice aspects away in order to emotionally connect with the consumer group through apolitical humor.

Leo Burnett also responded to the challenges set by P&G by creating a communication plan integrating social media, television and radio spots, magazine print, packaging, a website, in-store merchandising, and samples. The new potential of social media was integrated throughout the campaign via a Facebook page and YouTube videos. In the early 2000s, Facebook and YouTube were booming enterprises, used by millions daily all over the world. The use of commercials on both platforms have since been heavily debated and criticized, but in 2007 most advertisers were not recognizing its full potential. The combination of the strong lead character, humor, non-coded references to menstruation, and social media set the stage for the campaign, but of all these ingredients, Mother Nature herself dominated.

Case Studies from the Campaign

A handful of examples provide useful insights into the typical narrative of the overall campaign. The Mother Nature campaign was tied together across multiple communication channels by the tagline “Outsmart Mother Nature,” a red box carried by Mother Nature symbolizing menstruation, and Mother Nature herself in a green suit. Other than this, the campaign varied greatly in length, message, and scope across platforms. The television advertisements usually started with a young white woman (portrayed by a model) in a high-risk situation for menstruation: at the beach, wearing a short white skirt, dancing, in a romantic situation with a man, and so on. These situations were commonplace in menstrual advertising history, and the Mother Nature campaign made fun of them.Footnote 77 Mother Nature would interrupt the trope, trying to present the red box to the woman while delivering passive-aggressive quips like “It’s time for your monthly gift, dear” or “Did you miss me?” The women, initially surprised, quickly regained control over the situation and responded that they were not worried about her arrival, because “they had Tampax.” The interrupted activity (dancing, photo shoots, tennis, etc.) would resume, and Mother Nature would fade into the background, somewhat disgruntled or unsettled. Apart from the charisma of Mother Nature, there was nothing revolutionary in such portrayals of menstruation.

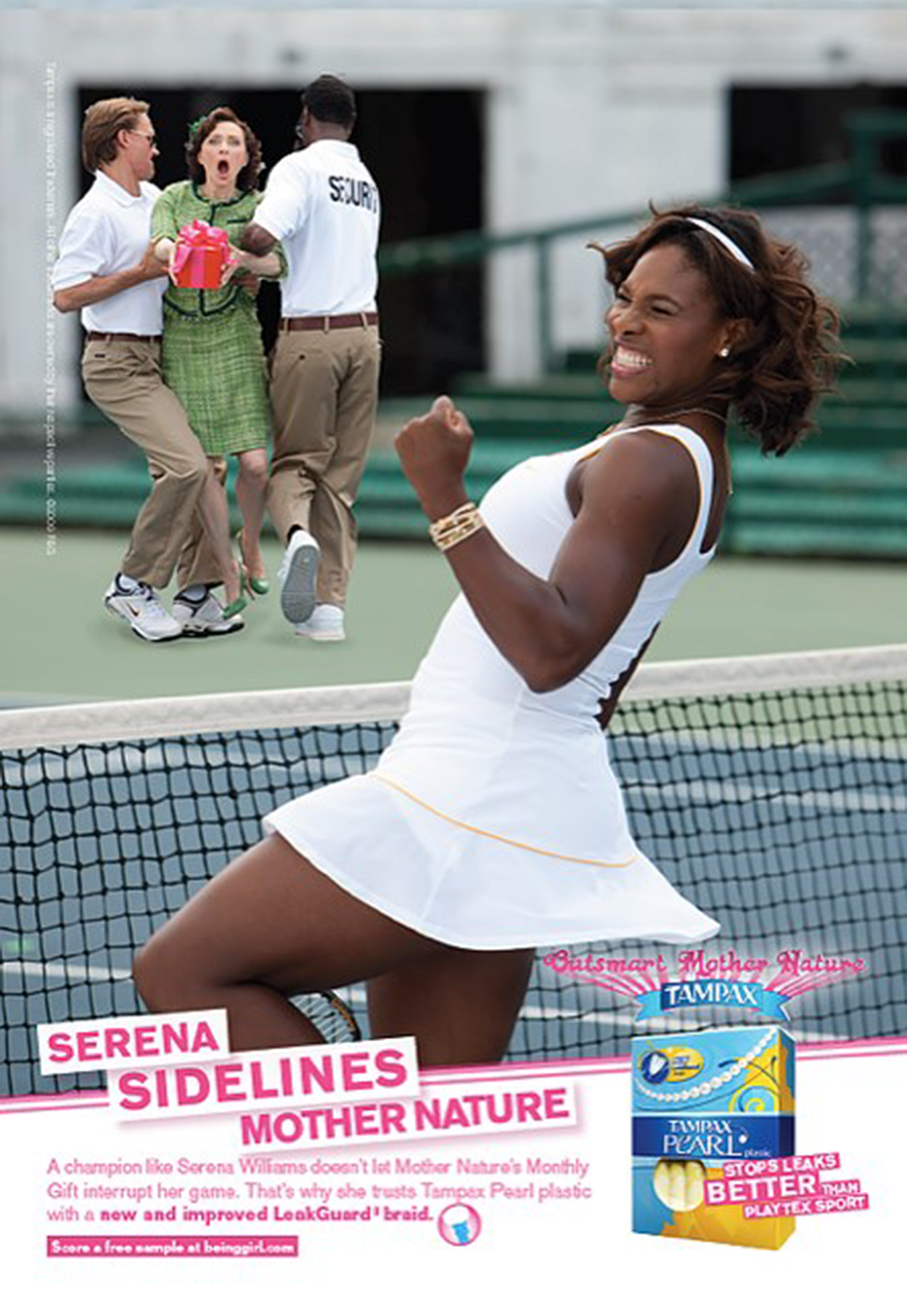

Figure 3 “Serena sidelines Mother Nature.”

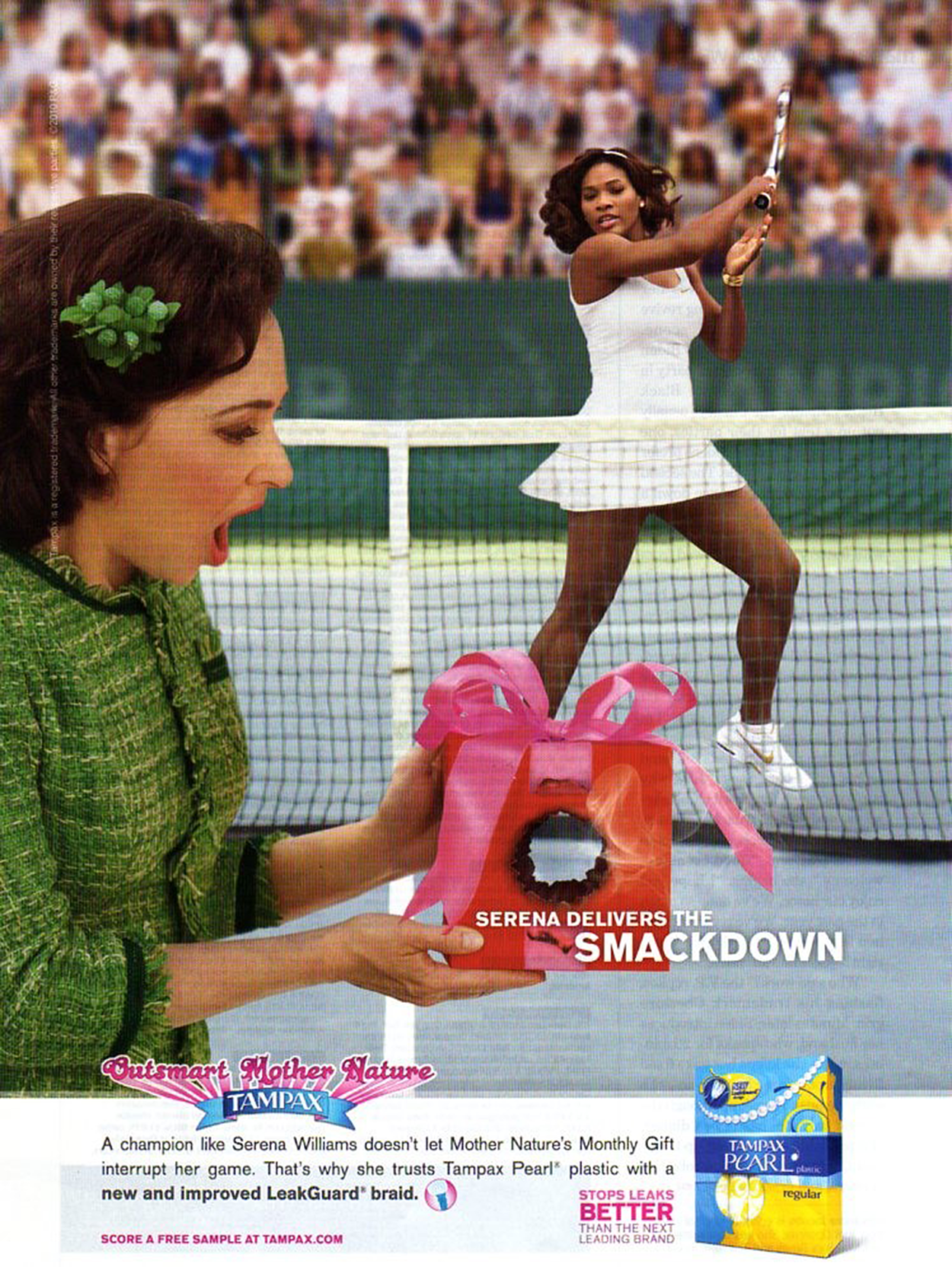

Figure 4 “Serena delivers the smackdown.”

A second strand of the campaign featured tennis player Serena Williams (Figures 3 and 4), an unusual front-woman for Tampax for many reasons. It had been decades since any celebrity had been willing to front a menstrual product, but it had remained a goal for Tampax and Leo Burnett. After numerous rejections from celebrity agents, both P&G and the creative team were delighted and surprised when Williams agreed.Footnote 78 For Williams, the campaign fit her goals of empowering girls and speaking about taboo topics like racism and women’s bodies in sports.Footnote 79 In the early 2000s, Williams was also talking about her own problems with menstrual migraines in the media—predating similar debates about Olympic athletes in 2016 by a decade.Footnote 80

Williams was already a superstar, although her stardom was galvanized after her historic winning streak, her appearance in a Beyoncé music video (“Sorry,” Lemonade, 2017), and more public engagement on matters of race and gender discrimination in tennis and beyond. Before Williams, Olympic gymnast Cathy Rigby had featured in print advertising for Stayfree pads (Johnson & Johnson at the time) in the 1980s, but by the 2000s famous celebrities favored gender-neutral brands with more money such as Nike.Footnote 81 Menstrual product advertising and female athletes, especially in tennis, had developed an uneasy relationship ever since the first women’s tennis tournament had declined Tampax sponsorship in favor of the Virginia Slims cigarette brand in the 1970s. Virginia Slims had by then gained a reputation for using feminist messages in its branding (the You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby campaign ran from the 1970s to the 1990s), whereas Tampax was seen as a threat because it linked so closely to an already existing stereotype of women in sports as hormonal and emotional.Footnote 82

Williams was presented as Mother Nature’s enemy in the posters and YouTube videos. She towered over Mother Nature, wearing a professional white outfit and beating the deity at tennis. The combination of these two unusual front-women, the menopausal goddess and the black woman champion, provides a striking collection of images. Each brings a distinct narrative to the campaign, and they were fleshed out as individuals who both respected and annoyed one another. Although the idea of pitching women against each other as competitors in advertising is not new, the combination of two minorities within advertising made the dynamic different from the ads featuring Burns alongside young scantily clad white models. Compared with the models, Williams was represented as being at work and in a non-embarrassing position. As equals and enemies, the two poked fun at each other in the videos and were given equal time to speak. The back-and-forth joking dynamic was thus different from the videos where Mother Nature was simply disrupting an anonymous woman’s life. Here, the woman talked back, while shown working and talking about menstruation. The YouTube videos featuring Williams were also the first in a long line of viral menstrual product advertising featuring women of color, for example Kotex’s collaboration with yoga instructor Jessamyn Stanley (2017), Lunette’s work with Madame Ghandi and Julie Atto (2017), Thinx’s controversial subway campaign (2016), Bodyform’s ongoing partnership with young influencers, and, on a larger scale, P&G’s My Black Is Beautiful campaign (2016). The recurrence of risk-taking in menstrual advertising and collaboration with women of color suggests the double-bind articulated by sociologist Patricia Hill Collins: “Black women remain visible yet silenced, their bodies become written by other texts.”Footnote 83 The advertising industry’s selective inclusion of African American women in particular, defined as “trendsetters” by Nielsen market research in the 2010s, has been extensively critiqued in terms of cultural appropriation and stereotyping.Footnote 84 For all these reasons, it is noteworthy that it was Williams who reached out to P&G, and, because she was part of shaping the videos she appears in, is not ridiculed, sexualized, or belittled in the campaign. At the same time, her cultural currency clearly provided P&G and Tampax with the star power the category had previously lacked, thus elevating the marketing into the realms of viral cultural product.

In addition to Williams’s historic fronting of a tampon, the language used in the videos she featured in is also notable in the history of menstrual advertising. During one of the YouTube videos built around a pre-match press conference with Mother Nature and Williams (currently over 50,000 views on YouTube), Mother Nature quips: “Bad blood? Well, there is plenty of blood, but none of it is bad.”Footnote 85 The mention of blood in a menstrual product campaign was norm-breaking, as the category usually relied on words such as “flow” or “liquid.” Whereas television and print were still governed by strict rules about what advertisers could show and say, social media provided a platform where menstrual reality could be presented. Menstrual product advertising was not allowed on television in the United States and United Kingdom until the late 1970s, and Kimberley-Clark was the first to use the word “period” in the campaign “Kotex fits. Period.” in 2000. Swanson explained that the use of words like “blood” in the Mother Nature campaign was only possible because there were so many women involved in the campaign.Footnote 86 Williams’ openness, personal interest in menstrual health, and her growing star power clearly also helped make the frank use of words and jokes a reality.

The videos and images featuring Williams brought star power to the campaign, whereas other videos broke different boundaries. In a guerrilla-style video (i.e., where only the actor knows about the camera, and participants sign consent forms afterward) filmed in Manchester (UK), Mother Nature stopped women on the street and tried to hand them “their monthly gift” (currently over 32,000 views). This resulted in a series of funny and awkward encounters set to George Thorogood’s rock song “Bad to the Bone” from 1982. Without a script, and dealing with a potentially sensitive topic, Burns had to navigate a series of social interactions while using puns and keeping in character. In one encounter she yells out to a woman who, when she turns around, is revealed to be heavily pregnant; “Never mind, I forgot!” quips Mother Nature and sashays away. When one woman asks what is in the red box, Burns erupts into laughter, arches her back and yells “That’s hilarious, darling!“ In another scene she chases women up escalators and has a conversation about period sex and fidelity with a young couple. While the underlying message was that it was time to Outsmart Mother Nature, Burns remained the focus of the video from start to finish. Despite the corporate messaging, it is difficult not to be amused as Burns chases down and laughs with women (and, to a lesser extent, men) on the street about a supposedly taboo topic. As a form of guerrilla advertising, the resulting video is unusual in its centering on a confident older woman who interacts and, at times, bullies members of the public. It is funny to watch Mother Nature’s wrath and irony, but clearly not to experience it.

Throughout the vast campaign landscape, the figure of Burns as Mother Nature tied everything together into a recognizable brand. As the campaign gained traction in popular culture and media, it was the lead character who caught the public imagination, although Williams and the use of humor was also applauded.

Who Is Mother Nature?

The creation of the Mother Nature character combined several female tropes, sometimes at odds with one another. She was to be “a villain of sorts,” an “opponent for girls,” and “like a mother-in-law!’Footnote 87 She was created to be irritating, but she was someone you “couldn’t entirely hate” because she was a “worthy adversary.”Footnote 88 Crucially, Mother Nature was created as a woman, not a girl. Described to be around the age of forty to fifty, Mother Nature may well have been going through menopause, the typical age at which menstruation stops. This paradox was never directly discussed in the advertisements, but underlines much of the visual humor in the campaign.Footnote 89 Menopausal women are, after all, experienced menstruators. Furthermore, the decision to visualize her at this age, meant that the young women in the campaign tended to look childish, while Burns looked powerful.

The costume, which would become recognizable across the campaign platforms, further underlined Mother Nature’s age and power. She was envisioned as a “sharply dressed she-devil, decked out in green Chanel and high heels.”Footnote 90 P&G sent an image of the costume, which is now housed in its archives (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Mother Nature costume in P&G archives.

The outfit visually referenced several women from popular culture who were making headlines in the 2000s. In 2006, the box-office success The Devil Wears Prada had introduced a similar character in postmenopausal, sharply dressed, unpleasant, smart, and powerful boss Miranda Priestly (Meryl Streep). Meneguzzo also cites the character of Bree Van de Kamp from the television series Desperate Housewives, a neurotic and perfectionist homemaker in turn inspired by the Stepford-wife archetype first conceptualized in Ira Levin’s 1972 satirical thriller about robotic wives.Footnote 91 In addition, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s style was visible in the bright Chanel-style suit. Drawing from this group of different women, the character was developed to gesture at their likeness, while also collapsing the cliché inhabited in their roles. Rather than a housewife or paid worker, Mother Nature was to be obsessed with her God-given duty, symbolized by her dedication to delivering “the monthly gift” on time, despite criticism or adversity. As a goddess, she was beyond the gendered expectations that faced the working women in The Devil Wears Prada and Kennedy Onassis, while also challenging the submissiveness of Bree Van de Kamp and the Stepford wives’ cold inhuman aesthetic. Like the latter’s robotic narrators, Mother Nature was not human, although she exerted human-like personality and opinion. She was ill at ease and angry in the human world, often tugging at her green suit as if it was too small for a goddess. Often patting her hair, and with a dainty performative gait, the character leaned into some feminine tropes, while losing her temper, laughing manically, or chuckling devilishly. Mother Nature soon had more character development than most figures in advertising, and therefore captured viewers’ attention.

In addition to the she-devil trope, the campaign also tapped into long-standing associations of women with nature. The idea of identifying nature as female (and science as male) has been extensively critiqued and explored by feminists and postcolonial scholars for its division of masculine and feminine qualities into strict binaries.Footnote 92 Nevertheless, the trope continues to exist in the personification of nature as a mother or as a feminine entity in advertising. In fact, P&G had success with the same core idea a few years prior, when the campaign for pad brand Naturella (named Always in the United States and United Kingdom) did well in “traditional countries” (Mexico, Russia, Poland).Footnote 93 The Naturella campaign featured women in nature, dressed in long flowing gowns, with a voice-over connecting femininity to the natural world. The product also included chamomile extract in order to be able to make the claim that the pad was “natural,” although P&G recognized that this should not be “overstated,” because the chamomile did not actually do anything and the product was not organic.Footnote 94 Thus, the superficial idea that women and nature are connected had been proven to be profitable for the corporation in other countries.

When Mother Nature was introduced as an idea for Western consumers, the message about femininity was delivered with irony rather than sincerity. The flowing garments from the Naturella campaign were swapped for a modern green business suit, but the underlying trope linking women and nature was nevertheless part of the core campaign idea. In the U.S. Leo Burnett office, Swanson remembers feeling nervous about this because of the many uses of the Mother Nature trope in North American campaigns, notably in the tagline for Chiffon margarine (“It’s Not Nice to Fool Mother Nature”).Footnote 95 Swanson explained that Meneguzzo was also aware of the trope, but that she felt so strongly about the idea that they agreed to develop a more interesting take on the figure.Footnote 96

The team challenged the tropes about a maternal, natural, and feminine goddess by making Mother Nature a character who was not entirely likable or easy to understand. Instead, she was to be a complicated figure. The tagline for the entire campaign underlines this: “Outsmart Mother Nature.” With the help of Tampax, the campaign promised to turn the old adversary of Mother Nature/menstruation into a nonissue. Mother Nature was an enemy to be conquered, and menstruation a problem to be fixed. After P&G agreed to the core ideas of the campaign, the casting process commenced in order to find an actress who would be able to embody and balance all the complicated, often paradoxical, characteristics that Leo Burnett had assigned to Mother Nature in 2007.

Casting Mother Nature

The casting was carried out in Los Angeles, London, and New York during several months in 2007, and involved more than one thousand actresses. Catherine Lloyd Burns won the part by making an early positive impression on Swanson and Meneguzzo. Burns had decided to present the character in a multidimensional way, including all of the personality traits Leo Burnett had described, rather than focusing on some of the characteristics. Burns ad-libbed in her audition, and added a loving tone mixed with a forceful and unpredictable dose of passive-aggressiveness at unexpected moments. She also created a striking voice for Mother Nature, which Meneguzzo recalls as “memorably annoying.”Footnote 97

Burns had previously acted on television series Malcolm in the Middle, as well as in films (Keeping the Faith, Everything Put Together). She had also written for children (The Good, the Bad and the Beagle) and adults (a memoir, It Hit Me Like a Ton of Bricks). At the time of the campaign, she was one of the first leading actresses in a major menstrual advertising campaign who was not a teenager. Apart from the use of athletes, the menstrual industry had hitherto focused on models and characters who were either near the age of menarche (first menstruation) or in their early twenties. The perceived wisdom in the industry was that young consumers were important, because once they had used one brand, they were likely to become loyal lifetime consumers.Footnote 98 The Mother Nature campaign was thus breaking away from tradition in more than one way by focusing on humor rather than information, starring a professional actress and a celebrity, and focusing on a woman over the age of 35.

Because of all of these reasons, Burns approached the campaign from many perspectives “as a woman, a feminist, an environmentalist, an actress, an older women.”Footnote 99 She also recognized that Leo Burnett and Tampax were trying to advertise in a new way and was happy to be part of a different creative approach. Burns shared her feminist perspective on this:

So often women are encouraged to be hairless, odorless, infinitely patient creatures whose job it is to shield the men they want to attract from regularly occurring bodily functions. I think the Mother Nature campaign was an attempt to take the piss out of the shame many of us are taught to feel about being on the rag. Funny commercials about something taboo are empowering.Footnote 100

Despite welcoming the ways in which the campaign broke taboos and incorporated humor, Burns also found the character challenging, especially as a caricature of a conservative and unsexy older woman. Her feminist beliefs were constantly at odds with the corporate interests. Although she valued the campaign, Mother Nature presented a paradox:

She herself was not a very empowering image for women (in my mind). Yes, she could make a hurricane and she was a working woman, that was empowering. But the lengths she went to in order to keep up appearances wasn’t [sic] very empowering (in my mind). Mother Nature was stuck in time. She wanted women in their place and their place was with her once a month. It was as if she thought modern young women had gotten a little too comfortable as women, and Mother Nature arrived once a month to remind them that in the end, a woman’s identity was controlled by shame and ultimately by the shame of getting her period.Footnote 101

Burns also questioned the corporate message inherent in the campaign, especially regarding the ways in which the Tampax product was always the rescuer in the narrative. In order to deal with the ambivalence she felt toward the role, Burns created a backstory for Mother Nature, within the strict confines of the campaign brief:

I did not feel that Mother Nature was a feminist icon. I had to make things up for that. Like I gave myself a very satisfying relationship with Father Time that no one knew about. I decided that contrary to my appearance I was deeply disappointed in the human race for not recognizing the price of their technological and industrial advancements [that] the world of nature was paying for. I also decided that my hair and makeup were done for me every morning by a bunch of bluebirds and fauns in a wooded clearing that was very beautiful. The source of my rage was progress and pollution, not women.Footnote 102

Worried about becoming merely a caricature, Burns added these story lines to justify and better understand her role in the wider menstrual discourse. She prepared for the role by learning more about menstrual history and culture, echoing the interests of the creative team at Leo Burnett. In the literature, she found that menstruation was a topic mired in shame, taboos, and scientific confusion, while also exploring the positive role of tampons. As a part of what Jennifer Scanlon defines as “the promise of consumer culture,” the invention and mass production of tampons had been liberating for many users throughout the world, despite issues of price, pain, and diseases like TSS.Footnote 103 In her reshaping of Mother Nature as a goddess and source of power, Burns echoes surgeon Leonard Schlain’s question: “What would be the result if women instead embraced the power Mother Nature gave them?”Footnote 104 Schlain wondered about this as part of his critique of hormone therapy treatments for menopausal women, but the same query manifested itself in Burns when she started inhabiting the character on a regular basis.

Burns work resulted in Mother Nature becoming an unusually detailed female character in a major advertising campaign of the 2000s, in turn making Burns a recognizable and popular figure. Burns used her voice, body, laugh, and knowledge to ad lib during the campaign, creating memorable moments that were not scripted by Leo Burnett or Tampax. Whereas models in earlier Tampax campaigns mostly smiled, posed, or made scripted statements, Mother Nature seemed like a character from a story, and Burns looked like she was having fun.

Cultural Impact

For P&G, the campaign succeeded in its specific objectives to reconquer the applicator-tampon market. The objective of increasing emotional equity with consumers was also considered to have been achieved, with Tampax experiencing a 27-point equity surge in a six-month period of 2008.Footnote 105 Importantly, it also closed the gap with competitor Playtex. Digital media was seen as an important part of the success (YouTube and Facebook in particular). In addition to reaching the goalposts set by P&G, the creative team at Leo Burnett were also recording a list of cultural impact examples.

Meneguzzo points out that she knew that they had succeeded when popular comedy television show Saturday Night Live enquired whether Mother Nature could give away a competition prize and when people started posting images of their homemade Mother Nature Halloween costumes on the campaign’s Facebook page (which currently counts 254, 000 followers, although the page is no longer active). In 2009, journalist Andrew Adam Newman notably reviewed the campaign for the New York Times, describing it favorably as one “that erases a layer of euphemisms.”Footnote 106 The campaign broke category boundaries when it won a prestigious advertising Effie award in 2010, marking one of the first—but not last—times that femcare won.Footnote 107 Swanson explained that after this more people wanted to work on menstrual product brands at Leo Burnett, thus making Meneguzzo’s dream of “making menstruation cool” a reality, at least in the advertising world. It was, as Swanson noted, “a big deal.”Footnote 108 Tampax has remained a sector leader ever since, but has not created any similarly culturally influential campaigns since Mother Nature wrapped in 2009.

The End

As Mother Nature gained popularity, the international aspects of creating a large campaign became more challenging behind the scenes. As the advertisements were rolled out in North America and Europe, Burns quickly realized that different corporate cultures wanted different things from the character. In the United States, she was increasingly asked to play the role as a “comedic oddball.”Footnote 109 However, the European P&G team felt that the U.S. version was “too ditzy.”Footnote 110 In the European market, Mother Nature was meant to be a colder and more powerful figure, someone who was judgmental of younger women and punished them with menstruation. The idea of the she-devil was thus more pronounced in the European campaign, and it was ultimately more successful. Then, just as the European version of Mother Nature began to dominate, the campaign was suddenly dropped entirely by P&G, resulting in confusion for the creative team and for Burns.

Was the frivolity, loudness, and power given to the character of Mother Nature not afforded to the real women involved? Mother Nature shared many characteristics with the people who birthed her: they were middle-aged women at the height of their careers who sometimes felt undervalued. They were also white and Western, passionate about supporting women, and increasingly interested in the sociocultural histories of menstruation. Furthermore, Mother Nature’s humor and inability to be embarrassed about menstruation mirrors the experiences of Swanson and Meneguzzo, who often challenged stereotypes and explained menstrual realities in corporate meetings with P&G.

All the interviewees explained how the cancellation had come as a surprise, because the campaign was so well received and the engagement was increasing.Footnote 111 One can only speculate as to the nature of the sudden end to the campaign, but a shift in top-level P&G corporate leadership resulting in a male-dominated corporate environment (yet again) occurred at the same time. According to the interviewees, squeamishness toward and a lack of understanding about menstruation was common among the P&G male employees involved.Footnote 112 Could it be that the male-dominated P&G team lost interest in the deliberately loud-mouthed, annoying, and abrasive Mother Nature character? Or did the expensive campaign simply wrap up once Leo Burnett’s work had achieved P&G’s stated aims?

Reflecting on the gendered power dynamics of the campaign, Burns noted that many of the videos featured young women in bikinis and that all the videos except one were directed by men. She also recalled that “more often than not those men paid more attention to the girls in bikinis and looked at me as an afterthought.”Footnote 113 By sexualizing the young women, and presenting them as objects for male heterosexual desire by promising to hide their menstruation, the advertisements often began from the perspective of what film historian Laura Mulvey described as “the male gaze” and present a world in which menstruation should be concealed.Footnote 114 This echoes the contemporary popularity of hormonal birth control, which can suppress menstruation, as well as public debates about PMS and women as unreliable hormonal persons. Discussions about menstruation and PMS often circulate around the notion that menstrual and menopausal bodies, which sometimes need rest, are not as productive under capitalism as those that are streamlined by hormonal birth control. There is a meta-echo of the debate about productivity and creativity in what the interviewees explain as the P&G male executives’ decreasing support of the campaign.Footnote 115 Branding, after all, is not supposed to eclipse the paternal corporation.Footnote 116 Mother Nature had outgrown her place and become unpredictable, while the Leo Burnett team was playing with humor and descriptive language, increasingly taking more chances. P&G promptly pulled the funding and switched its branding strategy.

P&G moved the Tampax campaign to the advertising agency Publicis in the early 2010s and has since produced a series of “how-to” guides for young girls on YouTube, abandoning the focus on adult women altogether (although the later introduction of a Tampax menstrual cup and acquisition of organic cotton brand This Is L. signals expansion). Meanwhile, Meneguzzo and Swanson moved on to lead other major international advertising campaigns. Burns has returned to writing. She continues to reflect on her time as a goddess for P&G and the many ways in which complicity and agency became part of her performance:

Personally, I switched from tampons to a menstrual cup years before I got the job. It was cheaper and it was better for the environment and I didn’t like the idea of men getting rich off of charging women money every month for products that were necessities. I am pretty sure that if men got their period there would be a more cost-efficient product on the market. When I did occasionally buy Tampax, I bought the regular cardboard applicator kind, not the plastic applicator Tampax Pearl. I hated the plastic applicator ones. I thought they were sadistic. The supposed flower petals opened up into a bouquet of very sharp, pointed shapes ready to cut you inside. I never got cut, but for some reason, the idea that such an intimately placed product could hurt was a science fiction nightmare I could not forget. So I always opted for the plain old cardboard.Footnote 117

Since the Mother Nature campaign ended, reusable and environmentally friendly menstrual products such as cups and washable pads have become a small but persistent part of the menstrual product market. P&G introduced a Tampax menstrual cup with disposable wipes for the vagina in 2018, and market research is suggesting that traditional corporations need to act fast to prevent a mass evacuation from single-use disposable items to reusable products.Footnote 118 In this way, Mother Nature turned out to be in line with what women want, as she and they increasingly turn away from disposable plastic and back to reusable options. For a figure created by women, this should perhaps not come as a surprise.

Conclusion

The Mother Nature campaign serves as an example of how gender dynamics remain inherent in marketing campaigns for menstrual products, but it also demonstrates the ways in which and reasons why gender use is shifting. The clearest example of this was the abandoned Zack and Advertise Your Period campaigns, which were too radical for P&G but exciting and award-winning for the Leo Burnett team. Mother Nature became a campaign that both emphasized and protested against gendered narratives that are common in Western culture. This was not just a creative choice, but also a move to capture new markets. In the late 2000s, P&G was specifically expanding into the postmenopausal female market and is now heavily marketing urinary pads to this group. In addition, surveys suggest that African American and black consumers are more sceptical toward tampons.Footnote 119 Gesturing to menopausal women and African Americans was useful for the corporation in a time when young white women are increasingly interested in willingly suppressing menstruation through long-acting reversible contraceptives.Footnote 120 Furthermore, as Francesca Sobande has shown, young African American and black women rely heavily on YouTube and social media to find representation, meaning that traditional marketing has followed suit.Footnote 121

Another key finding from this study relates to the work of women in the femcare area. The interviewees all reflected that traditional gender roles still had a stronghold in the corporate atmosphere where they were pitching ideas. To get their ideas heard, the Leo Burnett team had to mold their creativity to P&G’s view of menstruation. As a consequence, radical ideas such as Zack fell by the wayside, and the campaign became more conservative. At the same time, Swanson, Meneguzzo, and Burns expressed feminist beliefs and provided reasons for working in the industry from a social justice perspective. Serena Williams has also shown strong commitment to the advancement of women’s rights, and she continues to work against racism and sexism in tennis and beyond, as shown in her efforts to promote breast cancer awareness and protest discrimination against African American athletes and her support of the #MeToo movement. The predominance of women in the femcare category (both behind and in front of the camera) provides historians of women’s lives with exciting potential for future research, especially as the menstrual product industry continues to evolve.

In terms of impact on femcare branding, the campaign’s success paved the way for more explicitly feminist-branded advertising in the menstrual product sector, notably P&G’s viral and award-winning Like a Girl campaign for Always brand pads in 2014. This campaign, which sought to rebrand the concept of doing things “like a girl” as a positive description, was also created by Leo Burnett. Swanson, who worked on the campaign, recalls how her colleagues in advertising wanted to join the pink ghetto of femcare after Like a Girl became the first menstrual product advertisement to run during the Super Bowl, but she remembers Mother Nature as the critical turning point.Footnote 122 Today, most new menstrual product campaigns revolve around the promise of “breaking taboos.” For example, pad brand Bodyform (Essity) was the first to show blood as a red (rather than blue) liquid and to include boys in educational videos, while menstrual underwear brand THINX included trans men as models, and Kotex has made a viral miniseries about a lesbian vampire. These, and countless more “boundary-breaking” menstrual product ads from established and new brands, also follow in Mother Nature’s footsteps by using social media platforms, humor, and diverse identities.