INTRODUCTION

Since the discovery of the rich fauna at hydrothermal vents in 1977, about 115 polychaete species from 23 different families have been recorded from this habitat (Aguado & Rouse, Reference Aguado and Rouse2006; Morineaux et al., Reference Morineaux, Baker, Ramirez-Llodra and Desbruyères2010). Terebellidae Malmgren, Reference Malmgren1866, is one of the most speciose polychaete families with more than 550 valid species (Garraffoni & Lana, Reference Garraffoni and Lana2010). No terebellid species had been identified from deep-sea vents prior to this study. The only available evidence of the family was recorded as Terebellidae indet. (Hashimoto et al., Reference Hashimoto, Ohta, Fujikura and Miura1995; Schander et al., Reference Schander, Rapp, Kongsrud, Bakken, Berge, Cochrane, Oug, Byrkjedal, Todt, Cedhagen, Fosshagen, Gebruk, Larsen, Levin, Obst, Pleijel, Stöhr, Warén, Mikkelsen, Hadler-Jacobsen, Keuning, Heggøy Petersen, Thorseth and Pedersen2010). The second largest terebellomorph family, the Ampharetidae, is represented with four species that regularly form dense aggregations at vents in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, respectively. The Alvinellidae, initially described as aberrant representatives of Ampharetidae, seem to be confined to hydrothermal vents in the Pacific Ocean. Eleven species and one subspecies of these ‘Pompeii worms' have been described. Trichobranchids have not been found at vent sites.

Cold seep faunas seem to be less distinct from surrounding non-seep environments than hydrothermal vent faunas. Determining the number of polychaete species from this habitat is therefore less straightforward. Among terebellomorph polychaetes the Ampharetidae show highest species richness. Eleven species have been found; three of them are new records of this study. Three of the four hydrothermal vent species occur at cold seeps as well. Three species of Terebellidae and Trichobranchidae have been found at cold seeps, respectively. Two of the records in each family are new. Alvinellids seem to be absent from cold seeps. The fifth family that is traditionally considered as belonging to Terebellomorpha, the Pectinariidae, has not been recorded from either habitat to date.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The specimens examined in this study have been collected during cruises of the German research vessels RV ‘Meteor' and RV ‘Sonne' to hydrothermal vent sites in the Atlantic, the west, north-east and the south-east Pacific Ocean, i.e. Me 60/3, Hydromar I: Mid-Atlantic Ridge (Kuhn et al., Reference Kuhn, Alexander, Augustin, Birgel, Borowski, de Carvalho, Engemann, Ertl, Franz, Grech, Hekinian, Imhoff, Jellinek, Klar, Koschinsky, Kuever, Kulescha, Lackschewitz, Petersen, Ratmeyer, Renken, Ruhland, Scholten, Schreiber, Seifert, Süling, Türkay, Westernströer and Zielinski2004); Me 64/1, Marsüd 2: Mid-Atlantic Ridge (Haase et al., Reference Haase, Flies, Fretzdorff, Giere, Houk, Klar, Koschinsky, Küver, Marbler, Mason, Nowald, Ostertag-Henning, Paulick, Perner, Petersen, Ratmeyer, Schmidt, Schott, Schröder, Seifert, Seiter, Stecher, Strauss, Süling, Unverricht, Warmuth, Weber and Westernströer2005); Me 64/2, Hydromar II: Mid-Atlantic Ridge (Lackschewitz et al., Reference Lackschewitz, Armini, Augustin, Dubilier, Edge, Engemann, Fabian, Felden, Franke, Gärtner, Garbe-Schönberg, Gennerich, Hüttig, Marbler, Meyerdierks, Pape, Perner, Reuter, Ruhland, Schmidt, Schott, Schroeder, Schroll, Seiter, Stecher, Strauss, Viehweger, Weber, Wenzhöfer and Zielinski2005); So 99, Hyfiflux I: North Fiji Basin (Halbach et al., Reference Halbach, Auzende and Türkay1996); So 109/2, Hydrotrace: Axial Seamount off Oregon (Herzig et al., Reference Herzig, Suess and Linke1997); So 110, So-Ro: So 110/1a: Cascadia Margin off Oregon (Suess & Bohrmann, Reference Suess and Bohrmann1997); So 133, Edison II: Lihir Basin (Bismarck Archipelago) (Herzig et al., Reference Herzig, Hannington, Stoffers, Becker, Drischel, Franz, Gemmell, Höppner, Horn, Horz, Franklin, Jellinek, Jonasson, Kia, Mühlhan, Nickelsen, Percival, Perfit, Petersen, Schmidt, Seifert, Thiessen, Türkay, Tunnicliffe and Winn1998); So 134, Hyfiflux II: North Fiji Basin (Halbach et al., Reference Halbach, Giere, Seifert and Seifert1998); and So 157, Foundation 3: Pacific-Antarctic Ridge (Stoffers et al., Reference Stoffers, Worthington, Petersen, Hannington, Türkay, Ackermand, Borowski, Dankert, Fretzdorff, Haase, Hekinian, Hoppe, Jonasson, Kuhn, Lancaster, Monecke, Renno, Stecher and Weiershäuser2001).

Table 1. List of stations (MAR, Mid-Atlantic Ridge; PAR, Pacific–Antarctic Ridge; Me, RV ‘Meteor’; So, RV ‘Sonne’; TVG, TV-grab; ROV, remotely operated vehicle; HV, hydrothermal vent; CS, cold seep; HV → CS, hydrothermal vent in transition to cold seep).

Samples were taken using Van Veen grabs with integrated TV camera (TVG), and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and sieved on-board. Specimens were fixed in 10% formaldehyde–seawater solution and later transferred to 70% ethanol. Preserved specimens were examined using the stereo microscopes Wild Heerbrugg M5 and Zeiss Stemi 2000-C and the compound microscopes Olympus BH-2 and Zeiss Axiostar. Methylene blue was used in order to enhance contrast and visibility of certain structures.

Drawings of specimens were made using a camera lucida. Drawings were finalized according to the method described by Coleman (Reference Coleman2003). Photographs were taken with a Canon Powershot G7. Adobe Photoshop was used for shadings and assembly of plates.

The condition of the specimens is indicated in the text as: cs (complete specimen) and af (anterior fragment).

Types and additional specimens have been deposited in the following institutions: Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt (SMF) (http://sesam.senckenberg.de), Natural History Museum, London (NHMUK) and Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris (MNHN).

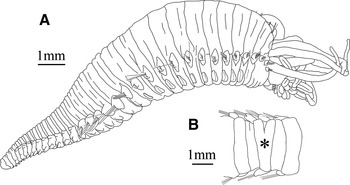

Fig. 1. Amathys lutzi. (A) Complete specimen, lateral view; (B) Y-shaped segment (*), dorsal view.

Amathys lutzi Desbruyères & Laubier, Reference Desbruyères and Laubier1996: 249–254, figures 1–3.—Desbruyères Reference Desbruyères2006d: 295, figures 1–5; Reference Desbruyères, Morineaux, Baker, Ramirez-Llodra and Desbruyères2010a: DVD, 5 figures.

SPECIMENS EXAMINED

15 specimens (12 cs, 3 af) (Me 60/3, Station 35 TVG) [SMF 17782, 17783, 17785, 17787-17790, 17792]. 2 specimens, complete (Me 60/3, Station 56 ROV) [SMF 17791]. 2 specimens, complete (Me 60/3, Station 66 ROV) [SMF 17784]. 78 specimens (76 cs, 2 af) (Me 64/1, Station 109 TVG) [SMF 17864, 17865]. 14 specimens (13 cs, 1 af) (Me 64/1, Station 125 ROV) [SMF 17859-17861, 17863]. 59 specimens (58 cs, 1 af) (Me 64/1, Station 132 TVG) [SMF 17866]. 1 specimen, complete (Me 64/1, Station 200 ROV) [SMF 17862]. 1 specimen, complete (Me 64/2, Station 232 ROV) [SMF 17830]. 15 specimens (14 cs, 1 af) (Me 64/2, Station 244 ROV) [SMF 17825, 17829]. 2 specimens (1 cs, 1 af) (Me 64/2, Station 266 ROV) [SMF 17827]. 2 specimens, complete (Me 64/2, Station 277 ROV) [SMF 17828]. 26 specimens (25 cs, 1 af), (Me 64/2, Station 281 ROV) [SMF 17826].

DIAGNOSIS

Prostomial glandular ridges and eye-spots absent. Buccal tentacles smooth. 4 pairs of cirriform branchiae in segments III and IV (2 + 2). Segment II without chaetae (paleae). 20 thoracic chaetigers. 17 thoracic uncinigers. No modified segment. Abdomen with glandular pads above neuropodia. Up to 18 abdominal segments. Thoracic and abdominal uncini with four teeth in one vertical row. Juvenile uncini with teeth in up to four rows.

REMARKS

While the regular number of notopodia is 20 (Figure 1A), twelve of the 207 complete specimens examined (6%) had an abnormal number of notopodia on one side. Five specimens had only 19 notopodia, six specimens had 21 notopodia, and one specimen 22 notopodia on one side while the opposite side showed the regular number of 20 notopodia. In most of those specimens it is the last thoracic segment or the first abdominal segment that lost or gained one notopodium, respectively. In contrast, two of the specimens had a Y-shaped segment in the mid-thorax that bears two notopodia on one side and only one on the other side (Figure 1B).

DISTRIBUTION

Hydrothermal vent fields along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The species was originally described from the Lucky Strike area and has meanwhile been recorded from the Rainbow, Broken Spur, Snake Pit and Logachev hydrothermal fields. It is here newly recorded from the hydrothermal vent fields Wideawake and Lilliput on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

Fig. 2. Amphisamytha galapagensis. Complete specimen, dorsolateral view.

Amphisamytha galapagensis Zottoli, Reference Zottoli1983: 382–389, figures 1–2.—Desbruyères Reference Desbruyères2006e: 296, figures 1–7; Reference Desbruyères, Morineaux, Baker, Ramirez-Llodra and Desbruyères2010b: DVD, 7 figures.

Amphisamytha fauchaldi Solís-Weiss & Hernández-Alcántara, Reference Solís-Weiss and Hernández-Alcántara1994: 128–133, figure 1.

SPECIMENS EXAMINED

1 specimen, complete (So 110/1a, Station 8 ROV) [SMF 17812]. 4 specimens, complete (So 157, Station 30 TVG) [SMF 17753-17755].

COMPARATIVE MATERIAL EXAMINED

Amphisamytha fauchaldi Solís-Weiss & Hernández-Alcántara, Reference Solís-Weiss and Hernández-Alcántara1994. Holotype, complete (Alvin Dive 1979) Guaymas Basin (Southern Trough), Riftia washings, 2014 m. Collected 18 February 1988 [USNM 168087].

Amphisamytha galapagensis Zottoli, Reference Zottoli1983. Holotype, complete (Alvin Dive N 990 #41) Galapagos Rift (Rose Garden), 2450 m. Collected 7 December 1979 [USNM 81288].

DIAGNOSIS

Prostomial glandular ridges and eye-spots absent. Buccal tentacles smooth. 4 pairs of cirriform branchiae in segments III and IV (2 + 2). Segment II without chaetae (paleae). 17 thoracic chaetigers. 14 thoracic uncinigers. No modified segment. Abdomen with glandular pads above neuropodia. Up to 15 abdominal segments. Thoracic and abdominal uncini with four teeth in one vertical row. Juvenile uncini with teeth in up to four rows.

REMARKS

Amphisamytha fauchaldi Solís-Weiss & Hernández-Alcántara, Reference Solís-Weiss and Hernández-Alcántara1994 is considered a junior synonym (see Reuscher et al. (Reference Reuscher, Fiege and Wehe2009) for a discussion).

DISTRIBUTION

Hydrothermal vent fields of the north-east and east Pacific (British Columbia; Guaymas Basin; EPR 21°N; EPR 9°–13°N; Galapagos Rift, type locality). Newly recorded here from hydrothermal vent fields at the Pacific–Antarctic Ridge in the south-east Pacific and from cold seeps sites at the Cascadia Margin off Oregon. This finding represents the first cold seep record since an earlier record from cold seeps at the Florida Escarpment was based on misidentification (McHugh & Tunnicliffe, Reference McHugh and Tunnicliffe1994).

The distribution of A. galapagensis is restricted to the eastern Pacific while records from the western Pacific appear to belong to the recently described species Amphisamytha vanuatuensis Reuscher, Fiege & Wehe, Reference Reuscher, Fiege and Wehe2009.

Amphisamytha galapagensis may be a species complex consisting of cryptic species (Chevaldonné et al., Reference Chevaldonné, Jollivet, Desbruyères, Lutz and Vrijenhoek2002).

Fig. 3. Grassleia hydrothermalis. Complete specimen, ventrolateral view.

Grassleia hydrothermalis Solís-Weiss, Reference Solís-Weiss1993: 662–665, figure 1.

SPECIMENS EXAMINED

1 specimen, complete (So 110/1a, Station 15 ROV) [SMF 17810].

DIAGNOSIS

Prostomial glandular ridges absent. Buccal tentacles smooth. 4 pairs of cirriform branchiae, arranged in one transverse line (presumably in segment IV). Segment II with notochaetae, not shaped as paleae. 15 thoracic chaetigers. 10 thoracic uncinigers. No modified segment. Abdomen without rudimentary notopodia. 7 abdominal segments. Thoracic and abdominal uncini with a multitude of teeth in several rows.

DISTRIBUTION

Hydrothermal vent fields of the north-east Pacific (off Oregon, type locality). Newly recorded here from cold seeps of the same area.

Fig. 4. Paralvinella dela: (A) complete specimen, dorsolateral view; (B) lower lip, ventral view. Paralvinella hessleri: (C) segments V–XIV, ventral view, showing 5 acicular hooks in segment VII (→) and notopodial lobes in segment VIII (*); (D) dissected chaetae of segment VII, showing 8 acicular hooks. Paralvinella unidentata: (E) acicular hooks of segment VII in mature specimen, dorsal view; (F) anterior end, ventrolateral view, showing regular chaetae of segment VII in immature specimen (→).

Paralvinella dela Detinova, Reference Detinova1988: 861–863, figure 2.—Desbruyères & Laubier Reference Desbruyères and Laubier1993: 235.—Desbruyères Reference Desbruyères2006a: 286, figures 1 & 2; Reference Desbruyères, Morineaux, Baker, Ramirez-Llodra and Desbruyères2010c: DVD, 2 figures.

SPECIMENS EXAMINED

2 specimens (1cs, 1 af) (So 134, Station 99 TVG) [SMF 17855].

DIAGNOSIS

Up to 170 chaetigers. 4 pairs of pinnate branchiae. Segment VII with 4 visible acicular hooks. Uncini from chaetigers 40–63. Notopodia without lobes. Uncini with two teeth.

REMARKS

Long and slender, with numerous (cs with 150) short segments (Figure 4A). Peristomium with ventral longitudinal furrows (Figure 4B).

DISTRIBUTION

Hydrothermal vent fields of the north-east Pacific (Juan de Fuca, type locality). Newly recorded here from hydrothermal vent fields of the west Pacific (North Fiji Basin).

Paralvinella hessleri Desbruyères & Laubier, Reference Desbruyères and Laubier1989: 761–767, figures 1–4.—Miura & Ohta Reference Miura and Ohta1991: 383–385, figure 1.—Desbruyères Reference Desbruyères2006b: 287, figures 1–3; Reference Desbruyères, Morineaux, Baker, Ramirez-Llodra and Desbruyères2010d: DVD, 5 figures.

SPECIMENS EXAMINED

11 specimens, complete (So 134, Station 35 TVG) [SMF 17851, 17854]. 10 specimens (8cs, 2af) (So 134, Station 99 TVG) [SMF 17852].

DIAGNOSIS

Up to 73 chaetigers. 4 pairs of pinnate branchiae. Segment VII with 4–5 visible acicular hooks. Uncini from chaetigers 14–21, located in long tori. Notopodia of segment IV through to segments XIII–XVII with dorsal lobes. Uncini with two teeth.

REMARKS

Most conspicuous notopodial lobes located in segment VIII (Figure 4C). We found that segment VII bears eight acicular hooks (Figure 4D). However, only 4–5 hooks penetrate the epidermis. A re-examination of the number of the acicular hooks of each species may be of taxonomic interest.

One specimen bears acicular hooks in segment IX (only on one side).

DISTRIBUTION

Hydrothermal vent fields of the west Pacific (Mariana Back–Arc Basin, type locality; Okinawa Trough; Manus Basin). Newly recorded here from hydrothermal vent fields of the North Fiji Basin.

Paralvinella unidentata Desbruyères & Laubier, Reference Desbruyères and Laubier1993: 226–232, figures 1, 3 & 4.—Desbruyères Reference Desbruyères2006c: 289–290, figures 1–9; Reference Desbruyères, Morineaux, Baker, Ramirez-Llodra and Desbruyères2010e: DVD, 8 figures.

SPECIMENS EXAMINED

30 specimens (26 cs, 4 af) (So 134, Station 35 TVG) [SMF 17853, 17886]. 9 specimens (8cs, 1 af) (So 134, Station 99 TVG) [SMF 17857, 17858].

DIAGNOSIS

Up to 88 chaetigers. 4 pairs of pinnate branchiae with terminal cirriform filament. Segment VII of larger specimens (>10 mm) with 2–3 relatively small and brittle acicular hooks. Uncini from chaetigers 23–31, located in long tori. Notopodia without dorsal lobes. Uncini with only one tooth.

REMARKS

While the maximum body length is given with 11 mm in the original description, our specimens measured up to 24 mm. Uncini start in chaetigers 23–31, rather than in chaetigers 26–31 as reported by Desbruyères & Laubier (Reference Desbruyères and Laubier1993). Acicular hooks were only developed in specimens with a body length of 11–24 mm and 80–82 chaetigers (Figure 4E). Specimens with a length of 2–10 mm and 35–80 chaetigers have not yet developed hooks in chaetiger 7. Instead, they bear simple capillary chaetae as in remaining segments (Figure 4F). Thus, Paralvinella unidentata seems to develop acicular hooks in a rather late stage of development. Similarly, Desbruyères & Laubier (Reference Desbruyères and Laubier1986) described the development of acicular hooks in P. pandorae irlandei Desbruyères & Laubier, Reference Desbruyères and Laubier1986 in specimens of >60 segments, i.e. close to the maximum number of segments (at a body length of ~14 mm). In contrast, P. hessleri has developed stout hooks in the 35 chaetiger stages at a body length of 1.5 mm (authors' observations). Desbruyères & Laubier (Reference Desbruyères and Laubier1993) described P. unidentata with acicular hooks, although their specimens measured only 4.8–11 mm.

DISTRIBUTION

Hydrothermal vent fields of the west Pacific (North Fiji Basin, type locality).

TYPE SPECIES

Amphitrite affinis Malmgren, Reference Malmgren1866.

GENERIC DIAGNOSIS (ACCORDING TO: HOLTHE 1986a, EMENDED)

3 pairs of dichotomous branchiae with pronounced stems in segments II–IV. Lateral lobes usually present. Nephridial papillae in segment III only or extending for a variable number of segments. Thorax with 15–39 pairs of notopodia starting in segment IV, and 14–38 uncinigerous neuropodia starting in segment V. Capillary chaetae distally hirsute. Uncini avicular, arranged in double rows in posterior thorax and, occasionally in anterior abdomen.

REMARKS

The generic diagnosis is emended to include Neoamphitrite hydrothermalis sp. nov. and N. glasbyi Londoño-Mesa & Carrera-Parra, Reference Londoño-Mesa and Carrera-Parra2005 whose numbers of notopodia are lower and higher, respectively, than in previously described species of this genus.

The genus Neoamphitrite was erected by Hessle (Reference Hessle1917) for some species formerly described as belonging to Amphitrite O.F. Müller, Reference Müller1771. In contrast to the latter genus, Neoamphitrite has, according to Hessle, dichotomous rather than filiform branchiae, the number of nephridia is higher, and the nephridial tubes are free rather than fused. Fauvel (Reference Fauvel1927) and Hutchings & Glasby (Reference Hutchings and Glasby1988) rejected Neoamphitrite since they considered the number and arrangement of nephridia as inappropriate for taxonomic purposes. The latter authors also regarded the different shapes of branchiae as not useful to delineate these two genera. They argued that the reduction of the branchial stem causes the filiform shape but that this reduction varied gradually among species of both genera. Nevertheless, we consider these characters useful and treat Neoamphitrite as a valid genus, as do a number of other authors (e.g. Hilbig, Reference Hilbig, Blake, Hilbig and Scott2000a; Londoño-Mesa & Carrera-Parra, Reference Londoño-Mesa and Carrera-Parra2005).

Fig. 5. Neoamphitrite hydrothermalis sp. nov. [SMF 17871; holotype]: (A) anterior end, lateral view; (B) capillary chaeta; (C) uncinus from anterior thoracic torus, lateral view.

TYPE MATERIAL

Holotype, anterior fragment (So 133, Station 10 TVG) [SMF 17871]. Paratype, anterior fragment (So 133, Station 10 TVG) [SMF 17870].

ADITIONAL MATERIAL EXAMINED

10 specimens, anterior fragments (So 133, Station 33 TVG) [SMF 17869].

DIAGNOSIS

3 pairs of dichotomous branchiae with pronounced stems in segments II–IV, gradually increasing in size. Lateral lobes present in segments II–IV, gradually decreasing in size. Nephridial papillae in segment III. 15 pairs of notopodia. Notochaetae capillaries with hirsute tips. Uncini avicular, arranged in double rows in last 8 thoracic segments and at least first 3 abdominal segments. Uncini with high number of teeth above main fang.

DESCRIPTION

Body small and delicate. Holotype incomplete, consisting of complete thorax with 15 chaetigers and three abdominal segments. Length about 13 mm. Head region bent at sharp angle. Epidermis of some anterior segments detached on dorsal side, giving anterior end a swollen appearance (Figure 5A). Tentacular lobe short and collar-like. Buccal tentacles filiform with a deep ventral groove. Eyespots absent. Upper lip undulating. Lower lip retracted, covering mouth, cushion-like. Peristomium with a fleshy ridge on ventral side, separated anteriorly from lower lip by groove. 3 pairs of branchiae in segments II–IV, gradually increasing in size. Branchiae dichotomous, with distinct annulated main stem and thick secondary branches with blunt ends. Branchiae arranged along longitudinal line; last pair of branchiae attached closely to notopodia, leaving a wide dorsomedian gap. Segment II with prominent lateral lobes protruding forwards. Lateral lobes of segment III slightly smaller, also protruding forwards. Lobes of segment IV small, only dorsally developed. Segments II and III ventrally thickened, cushion-like. One pair of large nephridial papillae, resembling notopodia; nephridial papillae located in segment III, arranged in line with following notopodia. Glandular pads in segments V–XII, gradually decreasing in width forming a glandular groove from segment XIII. 15 pairs of notopodia from segment IV. Neuropodia from segment V continuing to abdomen. Uncini in single rows from segments V–XI, in double rows, ‘face-to-face', in thoracic segments XII–XIX and in three remaining abdominal segments. Capillary chaetae bilimbate with hirsute tips (Figure 5B). Uncini of thorax and abdomen of same shape, avicular with large main fang, surmounted by 3 rows of numerous teeth, subrostrum with small process (Figure 5C).

VARIATIONS IN PARATYPES

No clear distinction between glandular pads and glandular groove.

REMARKS

The species differs from all other species of the genus Neoamphitrite by the number of notopodia. Whereas Neoamphitrite hydrothermalis sp. nov. has 15 pairs of notopodia, the remaining species have between 17 and 39 pairs. Unusual is also the arrangement of uncini in double rows in abdominal segments, a character also found in N. figulus (Dalyell, Reference Dalyell1853) and N. pachyderma (Hutchings & Glasby, Reference Hutchings and Glasby1988) comb. nov. The latter species was originally described as belonging to the genus Amphitrite. The new combination was introduced as the branchial shape of this species fits to the genus Neoamphitrite, rather than Amphitrite.

ETYMOLOGY

The species is named after the hydrothermal vent habitat where it was collected.

DISTRIBUTION

Hydrothermal vent fields of the west Pacific: Lihir Basin (Bismarck Archipelago).

Pista shizugawaensis Nishi & Tanaka Reference Nishi and Tanaka2006: 141–144, figures 2–4.

SPECIMENS EXAMINED

3 specimens (1 cs, 2af) (So 133, Station 44 TVG) [SMF 17868].

DIAGNOSIS

2 pairs of arborescent branchiae with pronounced stems in segments II–III, each pair consisting of equally or unequally sized branchiae. Lateral lobes present in peristomium and segments II–VI; peristomial lobes large, fleshy, conical protrusions, fused dorsally and ventrally; lobes of segment II small, ventrally fused, otherwise mostly covered by lobes of segment III; the latter lobes pronounced semi-circular protrusions; lobes of segment IV distinct protrusions but smaller than lobes of segment III; lobes of segments V and VI small and paddle-like, on ventral side. Nephridial papillae in segments VI and VII. 17 pairs of notopodia with smooth capillary chaetae from segment IV. Uncinigerous neuropodia from segment V. Uncini avicular, with prolonged shaft throughout, however less distinct in posterior thoracic segments.

REMARKS

The specimens from the Lihir Basin differ slightly from the description of Pista shizugawaensis: (1) in the shape of the peristomial lateral lobes which are conical rather than semicircular; and (2) in the shape of the uncini of the posterior thoracic segments with chitinized shafts clearly prolonged, albeit less distinct than in uncini of anterior segments. The first point may be due to preservation artefacts, while the latter is probably dependent on the stage of development (Saphronova, Reference Saphronova1985). Therefore, these differences do not justify the erection of a new species.

DISTRIBUTION

West Pacific: Japan (type locality: Shizugawa Bay, Honshu). Newly recorded here from cold seeps of the Lihir Basin (Bismarck Archipelago).

TYPE SPECIES

Grymaea bairdi Malmgren, Reference Malmgren1866.

GENERIC DIAGNOSIS (ACCORDING TO: KRITZLER, 1971, EMENDED)

Usually 3 pairs of filiform branchiae, some species with 0, 2, 4 or 5 pairs of branchiae; exceptionally, branchiae may be rudimentary. Branchiae from segment II. No lateral lobes. Nephridial papillae present or absent. Notopodia from segment II. Neuropodia from segment V. Notochaetae smooth capillaries. Uncini avicular, usually with well developed sub-terminal button. Uncini in single rows throughout, occasionally arranged in loop.

REMARKS

The generic diagnosis of Kritzler (Reference Kritzler1971) was emended to include Streblosoma kaia sp. nov. characterized by the presence of branchial rudiments.

Fig. 6. Streblosoma kaia sp. nov. [SMF 17820; holotype]: (A) anterior end, lateral view; (B) uncinus from anterior torus, lateral view; (C) uncinus from anterior torus, frontal view; (D) [SMF 17817; paratype] pygidium, dorsal view.

Table 2. Synoptic table for all species of the genus Streblosoma Sars Reference Sars1872. (MF, main fang; n.d., no data).

The number of notopodia given indicates the highest number found in the respective species. Numbers given with ‘ > ’ indicate the lowest number reported, based on the original description or counting on incomplete type specimens. (1) Original description; (2) Day (Reference Day1967); (3) Glasby & Hutchings (Reference Glasby and Hutchings1987); (4) Hartman (Reference Hartman1969); (5) Hessle (Reference Hessle1917); (6) Holthe (Reference Holthe1986a); (7) Hutchings (Reference Hutchings, Hanley, Caswell, Megirian and Larson1997); (8) Hutchings & Glasby (Reference Hutchings and Glasby1986); (9) Hutchings & Glasby (Reference Hutchings and Glasby1987); (10) Hutchings & Glasby (Reference Hutchings, Glasby, Wells, Walker, Kirkman and Lethbridge1990); (11) Londoño-Mesa & Carrera-Parra (Reference Londoño-Mesa and Carrera-Parra2005); (12) Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Wu and Qian1987); (13) authors' observations. According to Santos et al. (Reference Santos, Nogueira, Fukuda and Christoffersen2010), Pseudothelepus nyanganus Augener, Reference Augener1918 belongs to Streblosoma. A re-description of this species from South Africa is in preparation (Nogueira et al., in preparation, cited in Santos et al. (Reference Santos, Nogueira, Fukuda and Christoffersen2010)). *The description of S. pacifica Hilbig, Reference Hilbig, Blake, Hilbig and Scott2000a appears to be based on a misinterpretation of the generic diagnosis of the genus Streblosoma and should be re-examined.

Invalid species (according to Holthe Reference Holthe1986b):

- S. cochleatum Sars, 1872

Synonym of Streblosoma bairdi Malmgren, Reference Malmgren1866

- S. crassibranchiata Monro, Reference Monro1933

Error for Streblosoma crassibranchia Treadwell, Reference Treadwell1914

- S. magna Treadwell, Reference Treadwell1937

Synonym of Thelepus crispus Johnson, Reference Johnson1901

- S. verrilli Treadwell, Reference Treadwell1911

Synonym of Thelepus setosus (Quatrefages, Reference de Quatrefages1866)

TYPE MATERIAL

Holotype, anterior fragment (So 134, Station 66 TVG) [SMF 17820]. Paratypes (1 cs, 1 af) (So 134, Station 35 TVG) [SMF 17817]. Paratypes (1 cs, 2 af) (So 134, Station 35 TVG) [SMF 17832]. Paratypes (1 cs) (So 134, Station 35 TVG) [MNHN-POLY TYPE 1526]. Paratypes (3 af) (So 134, Station 35 TVG) [NHMUK: 2011. 13–15]. Paratypes (1cs, 1 af) (So 134, Station 99 TVG) [SMF 17818].

ADDITIONAL MATERIAL EXAMINED

8 specimens, anterior fragments (So 99, Station 115 TVG) [SMF 17824]. 49 specimens (1cs, 48 af) (So 134, Station 35 TVG) [SMF 17821, 17874]. 21 specimens, anterior fragments (So 134, Station 66 TVG) [SMF 17873]. 51 specimens, anterior fragments (So 134, Station 99 TVG) [SMF 17875].

DIAGNOSIS

Branchiae reduced to small papilliform rudiments in segments II and III, or entirely lacking. Four pairs of nephridial papillae from segments IV–VII. Up to 82 pairs of notopodia with smooth capillary chaetae from segment II continuing almost to posterior end. Neuropodia with uncini from segment V to posterior end. Uncini avicular, with broad and blunt sub-terminal button.

DESCRIPTION

Length of holotype about 80 mm for 57 thoracic chaetigers. Posterior end missing. Tentacular lobe collar-like. Numerous long tentacles with deep median groove. Eye-spots absent. Upper lip folded. Lower lip crenulated (Figure 6A). Two pairs of small papilliform branchial rudiments in segments II and III. First pair with two papillae on each side, second pair with one big papilla on each side, situated immediately dorsally to notopodia, leaving a wide dorsomedian gap. Lateral lobes absent. Glandular pads, in anterior segments hardly discernible because of highly rugose epidermis, continuing to segment XXVII. Central ventral groove from segment XXVIII. Four pairs of nephridial papillae in segments IV–VII, gradually increasing in size. Papillae situated below notopodia or between notopodia and neuropodia, respectively. Notopodia with smooth capillary chaetae from segment II, first pair slightly shifted dorsally. Neuropodia with uncini from segment V, becoming more erect in posterior segments. Uncini avicular, with 2 horizontally arranged teeth above main fang and three uppermost teeth. Basal prow moderately developed. Sub-terminal button well developed, broad and blunt, separated from prow by distinct notch (Figure 6B, C). Uncini with same shape throughout, gradually decreasing in size towards posterior end. Pygidium missing in holotype.

VARIATIONS IN PARATYPES AND ADDITIONAL MATERIAL

Complete specimens without distinct separation of thorax and abdomen. Notopodia and notochaetae present almost to pygidium, notopodia becoming gradually smaller and hardly visible in posterior segments. Up to 82 chaetigers with notochaetae and 18 posterior segments with uncini only. Number of branchial rudiments of all specimens studied varies between 0 and 4 in segment II and 0 and 2 in segment III. Rudiments of some specimens are arranged on a more or less distinct transverse ridge. Pygidium surrounded by a circle of about 9–14 broad, blunt papillae (Figure 6D). Tubes stiff, yellow-brown.

REMARKS

The strong reduction of branchiae is one of the remarkable characters of the new species described here. A similar phenomenon is described for S. oligobranchiatum Nogueira & Amaral, Reference Nogueira and Amaral2001 and for two species in the genus Thelepus Leuckart, Reference Leuckart1849: T. praecox Hutchings & Glasby, Reference Hutchings and Glasby1987 with minute papillae and T. microbranchiatus Caullery, Reference Caullery1944 with very short, rudimentary filaments. Nephridial papillae are hardly visible in some specimens, especially smaller ones. In some specimens, notopodia in segment II are completely absent or present only on one side. Because there are no visible scars, an intra-specific variation regarding the presence of the first notopodia may be possible. This would, however, question the distinction between the genera Streblosoma (segment II with notopodia) and Thelepus (segment II without notopodia). We rather consider those specimens as aberrant.

The only species with a complete branchial reduction in the genus Streblosoma is S. abranchiata Day, Reference Day1963. It differs from S. kaia sp. nov. in having a lower number of notopodia, a considerable number of abdominal segments without notopodia and a different shape of uncini. The morphologically most similar species to S. kaia sp. nov. regarding reduced number and length of branchiae is S. oligobranchiatum. It differs from S. kaia sp. nov. in the shape of the uncini and the possession of eyes, whereas the small number of segments described for S. oligobranchiatum may be correlated to the small body size of the type material. The following species have a reduced number of branchial filaments: S. antarctica (Monro, Reference Monro1936), S. atlanticus (Hartman & Fauchald, Reference Hartman and Fauchald1971), S. chilensis (McIntosh, Reference McIntosh1885), S. duplicata Hutchings, Reference Hutchings and Morton1990, S. intestinalis Sars, Reference Sars1872 and S. minutum Hutchings & Glasby, Reference Hutchings and Glasby1987. In contrast to the new species described here, only the number but not the size of branchial filaments is reduced. Table 2 shows the distinguishing characters for all valid species of the genus Streblosoma.

ETYMOLOGY

The species name refers to the Melanesian demons Kaia that inhabit volcanoes and metamorphose into different animals.

DISTRIBUTION

Hydrothermal vent fields of the west Pacific: North Fiji Basin.

Thelepus extensus Hutchings & Glasby, Reference Hutchings and Glasby1987: 233–236, figure 9.

SPECIMEN EXAMINED

1 specimen, complete (So 109/2, Station 121 TVG) [SMF 17872].

DIAGNOSIS

3 pairs of filiform branchiae in segments II–IV with distinct dorsomedian gap. About 80 pairs of notopodia with smooth capillary chaetae from segment III. Neuropodia with uncini from segment V to posterior end. Number of abdominal segments about 110. Uncini avicular, with sub-terminal button.

REMARKS

Thelepus extensus is similar to Thelepus setosus Quatrefages, Reference de Quatrefages1866. The latter is described as a cosmopolitan species, which also occurs in north-east Pacific waters. The specimen examined here belongs to T. extensus since it has a distinct dorsomedian gap between the branchial filaments and more abdominal than thoracic segments, which are the distinguishing characters, according to Hutchings & Glasby (Reference Hutchings and Glasby1987).

DISTRIBUTION

Western Pacific: Australia (type locality: West Island, South Australia). Newly recorded here from cold seeps of the north-east Pacific off Oregon.

Terebellides horikoshii Imajima & Williams, Reference Imajima and Williams1985: 15–16, figure 4d–f.—Hilbig, Reference Hilbig, Blake, Hilbig and Scott2000b: 303–304, figure 10.4.—Hutchings & Peart, Reference Hutchings and Peart2000: table 3a & b.

SPECIMENS EXAMINED

2 specimens (1cs, 1 af) (So 110/1a, Station 9 TVG) [SMF 17838].

DIAGNOSIS

Branchial lobes fused for half of their length. First pair of notopodia well developed. Lateral lappets of chaetigers 1–3 well developed, those of chaetigers 4 and 5 inconspicuous. Notopodia of segment 2 somewhat elevated. Acicular neurochaetae of chaetiger 6 gently curved, their tip not covered by sheath. Following thoracic chaetigers with about 40 long-handled uncini per neuropodium.

DISTRIBUTION

West Pacific: Japan (type locality: Suruga Bay, Honshu), off Kamchatka. East Pacific: California. Newly recorded here from cold seeps of the north-east Pacific off Oregon.

Terebellides stroemii kerguelensis McIntosh, Reference McIntosh1885: 480–481, plate 19A, figures 7 & 8, plate 38A, figure 4.—Hutchings & Peart, Reference Hutchings and Peart2000: tables 3a & 3b.

Terebellides kerguelensis Parapar & Moreira, Reference Parapar and Moreira2008: 145–148, figures 1–5.

SPECIMEN EXAMINED

1 specimen, complete (So 110/1a, Station 4 ROV) [SMF 17836].

DIAGNOSIS

Branchial lobes fused for half of their length. First pair of notopodia well developed. Lateral lappets weakly developed, only distinguishable in chaetigers 1 and 2. Acicular neurochaetae of chaetiger 6 bent at right angle. Following thoracic chaetigers with about 10 long-handled uncini per neuropodium.

DISTRIBUTION

Antarctic: Kerguelen Islands (type locality: off London River and Christmas Harbour), South Shetland Islands, Bellingshausen Sea. Newly recorded here from cold seeps of the north-east Pacific off Oregon.

KEY TO TEREBELLOMORPH POLYCHAETES FROM HYDROTHERMAL VENTS:

1. No acicular hooks in anterior segments………2

– Acicular hooks in one or two anterior segments present………Alvinellidae Desbruyères & Laubier, Reference Desbruyères and Laubier1980 3

2. Buccal tentacles retractable. Branchiae cirriform………Ampharetidae Malmgren, Reference Malmgren1866 14

– Buccal tentacles not retractable. Branchiae dichotomous, filiform, or reduced…Terebellidae Malmgren, Reference Malmgren1866 17

Alvinellidae

3. Chaetigers 4 and 5 with acicular hooks………Alvinella Desbruyères & Laubier, Reference Desbruyères and Laubier1980 4

– Chaetiger 7 with acicular hooks………Paralvinella Desbruyères & Laubier, Reference Desbruyères and Laubier1982 5

4. Body divided into two parts. Posterior part tail-like. Notopodia of posterior part with digitiform lobes. Up to 200 chaetigers………Alvinella caudata Desbruyères & Laubier, 1986

– Body uniform. Posterior part not tail-like. Notopodia of posterior part without digitiform lobes. Less than 100 chaetigers………Alvinella pompejana Desbruyères & Laubier, Reference Desbruyères and Laubier1980

5. First uncinigerous tori in chaetiger 5 or 6………6

– First uncinigerous tori in more posterior chaetiger…7

6. First uncinigerous tori in chaetiger 5………Paralvinella pandorae pandorae Desbruyères & Laubier, 1986

– First uncinigerous tori in chaetiger 6………Paralvinella pandorae irlandei Desbruyères & Laubier, Reference Desbruyères and Laubier1986

7. First uncinigerous tori in chaetiger 31 or more anterior chaetiger………8

– First uncinigerous tori in chaetiger 35 or more posterior chaetiger………13

8. Less than 70 chaetigers………9

– More than 70 chaetigers………11

9. First uncinigerous tori in chaetigers 25–31………Paralvinella sulfincola Desbruyères & Laubier, 1993

– First uncinigerous tori in more anterior chaetiger…10

10. First uncinigerous tori in chaetigers 16–21. 4–5 acicular hooks. Notopodial lobes from chaetigers 4 to 13–17………Paralvinella hessleri Desbruyères & Laubier, 1989

– First uncinigerous tori in chaetigers 12–19. 3–4 acicular hooks. Notopodial lobes from chaetigers…9 to 30 Paralvinella fijiensis Desbruyères & Laubier, Reference Desbruyères and Laubier1993

11. Up to 88 chaetigers. Branchiae with terminal filament. 2–3 acicular hooks. No notopodial lobes. Uncini with 1 tooth………Paralvinella unidentata Desbruyères & Laubier, 1993

– More than 88 chaetigers. Branchiae without terminal filament. 3–5 acicular hooks. Some anterior notopodia with lobes. Uncini with 2 teeth………12

12. First uncinigerous tori in chaetigers 13–17. 3–4 acicular hooks………Paralvinella grasslei Desbruyères & Laubier, 1982

– First uncinigerous tori in chaetigers 20–31. 5 acicular hooks………Paralvinella palmiformis Desbruyères & Laubier, Reference Desbruyères and Laubier1986

13. First uncinigerous tori in chaetigers 35–37. 4–6 acicular hooks. Notopodial lobes present in chaetigers 8–32………Paralvinella bactericola Desbruyères & Laubier, Reference Desbruyères and Laubier1991

– First uncinigerous tori in chaetigers 40–63. 4 acicular hooks. Notopodial lobes absent………Paralvinella dela Detinova, Reference Detinova1988

Ampharetidae

14. 10 thoracic uncinigers………Grassleia hydrothermalis Solís-Weiss, 1993

– 14 or 17 thoracic uncinigers………15

15. 17 thoracic uncinigers………Amathys lutzi Desbruyères & Laubier, 1996

– 14 thoracic uncinigers………16

16. Up to 25 abdominal segments. Abdominal glandular ridges with papilliform cirri………Amphisamytha vanuatuensis Reuscher, Fiege & Wehe, 2009

– Up to 15 abdominal segments. Abdominal glandular ridges without papilliform cirri………Amphisamytha galapagensis Zottoli, Reference Zottoli1983

Terebellidae

17. 3 pairs of dichotomous branchiae. 15 pairs of notopodia. Uncini in posterior thorax arranged in double rows………Neoamphitrite hydrothermalis sp. nov.

– 0–2 pairs of papilliform branchial rudiments. More than 50 pairs of notopodia. Uncini never arranged in double rows………Streblosoma kaia sp. nov.

KEY TO TEREBELLOMORPH POLYCHAETES FROM COLD SEEPS:

1. Neurochaetae of first unciniger not formed as acicular hooks………2

–First neurochaetae formed as acicular hooks………Trichobranchidae Malmgren, Reference Malmgren1866 3

2. Buccal tentacles retractable. Branchiae cirriform………Ampharetidae Malmgren, Reference Malmgren1866 5

– Buccal tentacles not retractable. Branchiae dichotomous,………filiform or, reduced Terebellidae Malmgren, Reference Malmgren1866 15

Trichobranchidae (genusTerebellides)

3. Thoracic uncini arranged in at least two rows………Terebellides horikoshii Imajima & Williams, 1985

– Thoracic uncini arranged in single row………4

4. Lateral lappets in chaetigers 1–3. Acicular hooks gently curved………Terebellides stroemii Sars, 1835

– Lateral lappets in chaetigers 1–5. Acicular hooks bent at right angle……Terebellides kerguelensis (McIntosh, Reference McIntosh1885)

Ampharetidae

5. 3 pairs of branchiae………6

– 4 pairs of branchiae………8

6. 12 thoracic uncinigers. Notopodia of unciniger 8 elevated………Anobothrus laubieri (Desbruyères, Reference Desbruyères1978)

– 11 thoracic uncinigers. Notopodia of unciniger 8 not elevated………7

7. No gap between left and right group of branchiae………Glyphanostomum holthei Reuscher, Fiege & Wehe, 2009

– Wide median gap between groups of branchiae………Glyphanostomum pallescens (Théel, Reference Théel1879)

8. 10 thoracic uncinigers………Grassleia hydrothermalis Solís-Weiss, 1993

– 11, 12 or 14 thoracic uncinigers………9

9. 11 thoracic uncinigers………Amagopsis klugei Pergament & Khlebovich in Klebovich Reference Klebovich1964

– 12 or 14 thoracic uncinigers………10

10. 12 thoracic uncinigers………11

– 14 thoracic uncinigers………13

11. Notopodia of uncinigEr 8 elevated………Anobothrus apaleatus Reuscher, Fiege & Wehe, 2009

– Notopodia of unciniger 8 not elevated………12

12. Notochaetae of segment II present………Pavelius ushakovius Kuznetsov & Levenstein, Reference Kuznetsov and Levenstein1988

– Notochaetae of segment II absent … Amage benhami Reuscher, Fiege & Wehe, Reference Reuscher, Fiege and Wehe2009

13. Notochaetae of segment II present………Amphicteis gunneri (Sars, Reference Sars1835)

– Notochaetae of segment II absent………14

14. Up to 25 abdominal segments. Abdominal glandular ridges with papilliform cirri………Amphisamytha vanuatuensis Reuscher, Fiege & Wehe, 2009

– Up to 15 abdominal segments. Abdominal glandular ridges without papilliform cirri………Amphisamytha galapagensis Zottoli, Reference Zottoli1983

Terebellidae

15. Branchiae dichotomous. Uncini of anterior thorax with long shafts. Uncini of posterior thorax arranged in double rows………Pista shizugawaensis Nishi & Tanaka, 2006

– Branchiae filiform. Uncini of anterior thorax without long shafts. Uncini arranged in single rows throughout………16

16. 2 pairs of branchiae………Thelepus cincinnatus (Fabricius, Reference Fabricius1780)

– 3 pairs of branchiae………Thelepus extensus Hutchings & Glasby, Reference Hutchings and Glasby1987

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank our colleagues Michael Türkay and Jens Stecher (both Senckenberg Forschungsinstitut und Naturmuseum), Thomas Jellinek (University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, formerly Senckenberg Forschungsinstitut und Naturmuseum), and Heiko Sahling (Marum, University of Bremen) for collecting and making the material available to us. Kristian Fauchald (Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC) is thanked for the loan of type specimens, and Julio Parapar (Universidade da Coruña) for providing us with a then unpublished manuscript.