A range of styles is seen among the metal figurines from Roman Britain including imported, highly classical pieces and figurines exhibiting various provincial features. Little thought has been given to the origins of these stylised figurines and once many were assumed to have been made in Gaul.Footnote 1 However, the presence of figurines depicting a specifically Romano-British subject, such as the horse and rider figurines of eastern central England, implies that figurines were produced within Britain. There is little direct evidence for the production of figurines in Britain, but one example of a mould from Gestingthorpe (Essex), a site where bronze working was taking place in the third and fourth centuries, shows the stomach and thigh of a male and an ivy-leaf wreath, which indicates that this was probably Bacchus, or possibly a character associated with him.Footnote 2 This paper examines the figurines exhibiting a specific range of stylistic traits which indicate the presence of a tradition in South-West England with a particular focus on the Southbroom hoard from Devizes (Wilts.). Some of the figurines in this hoard are in a naturalistic, Graeco-Roman style, while others are in a more native tradition exhibiting idiosyncratic attributes and employing an unusual and distinctive style which suggests that they were the product of the same workshop. Some of the attributes used, such as the ram-horned snake, are commonly associated with Gaul, while the presence of a particularly Gallo-Roman deity — Sucellus — might indicate a Gaulish origin for the pieces. However, a small number of other figurines, largely from sites in the region around Devizes, show similar stylistic traits to those of the Southbroom hoard and suggest that they were produced in this area.

Also among the figurines from the Southbroom hoard is an unusual dog or wolf, which may depict a wolf deity. Once again the origins of this figure type may lie in Gaul, but two figurines from Llys Awel, north Wales, show a development of this theme which may be connected to the particularly British ritual associations with dogs.Footnote 3

A close examination of both the stylistic and symbolic features of these figurines provides interesting insights into artistic and religious influences in early Roman Britain.

THE COMPOSITION OF THE SOUTHBROOM HOARD

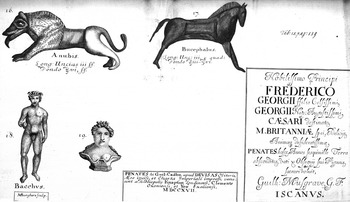

The Southbroom hoard was discovered in 1714 just to the south of Devizes ( fig. 1). It consisted of a Roman pottery vessel containing coins, seventeen figurines (see Appendix), a steelyard weight in the form of a female bust, and a discus from a picture lamp. Eight of the figurines are now in the British Museum while the remainder are lost, as are the weight and lamp.Footnote 4 The only record of the missing objects is the original drawings, first published in 1717 and then again by Musgrave in 1719 ( figs 2–3). The illustrations appear to be fairly accurate — both in direct comparison with the surviving figurines in the British Museum and as noted by Stukeley — although it is clear that a certain amount of interpretation has been undertaken as is often the case in antiquarian drawings.Footnote 5 The illustration of the picture lamp shows that the discus was decorated with the figure of a curled sleeping dog. Roman picture lamps depicting curled dogs, sometimes with a puppy, occur in both bronze and clay and a first-century example is known from Colchester.Footnote 6

FIG. 1. Location of sites mentioned in the text.

FIG. 2. The Southbroom hoard: Musgrave 1719, tables IV–VII. (Courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. Manuscript Gough Somerset 53)

FIG. 3. The Southbroom hoard: Musgrave 1719, table IX. (Courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. Manuscript Gough Somerset 53)

The missing figurines from the hoard are Venus, Vulcan M5, Mars M10, Bacchus, Genius Paterfamilias, an unidentified deity, a three-horned bull, a dog or wolf, and a horse. All of the deities, except the unidentified piece, are typically classical examples of their type and are found on many sites both in Britain and on the Continent, while the three-horned bull and horse are less common. In fact, the three-horned bull is a Romano-Celtic mythological, perhaps divine, creature which originated in Gaul; there are some 40 examples from that region, particularly in the valleys of the upper Rhône, Saône and Seine rivers in eastern Gaul, while there are seven from Britain.Footnote 7 The dog or wolf figurine mentioned above is more unusual and will be discussed further below. A striking aspect of the Southbroom collection is the presence of both highly classical and stylised figures in the same hoard. As George Boon noted, the missing figurines could have been acquired by a collector who valued the classical pieces but rejected the stylised ones.Footnote 8 However, while antiquaries may have considered the more native-looking pieces to be of inferior quality, they obviously were regarded highly enough in Roman times to take their place alongside classical figurines.

The rather unusual style and attributes of the stylised figurines has led to some confusion over their identities and, before beginning a detailed description of the stylistic attributes of the group as a whole, their identities are briefly reviewed ( fig. 4). Figurine M6 ( fig. 4b) is quite obviously Mercury, with the petasos (winged hat) and money purse which are seen with many Mercury figurines. The helmet and slightly clumsy depiction of a shield and spear identify figurine M8 as Minerva ( fig. 4g), while the tunic and pointed hat indicate that figurine M13 is Vulcan ( fig. 4d); both figurines are in stances that are fairly common for their type.Footnote 9 Rather less common is the pose of the Mother Goddess ( fig. 4h), although a standing woman with her arms across her stomach is represented on other bronze figurines in Roman Britain.Footnote 10 This posture is also shown on a stone figure from near the palace at Fishbourne (Sussex),Footnote 11 which is made of Cotswold oolitic limestone, thus locating its place of origin near the figurines under discussion. Boon does not identify figurine M11 as any particular deity, while Miranda Aldhouse-Green suggests that it could be Hercules,Footnote 12 but the posture, clothing and beard indicate that this is more likely to be Sucellus ( fig. 4c). Figurines from Augst, Switzerland and Chalon-sur-Saône (Saône-et-Loire), France are somewhat similar and both stand with the left hand palm up to hold the pot with which Sucellus is often depicted, while the Augst figurine also holds a fragment of an iron hammer in his right hand ( fig. 5).Footnote 13 Unfortunately the attributes are missing from the clenched hands of the Southbroom Sucellus. Although Boon identified figurine M3 as Jupiter ( fig. 4a), it is interesting to note that Cunnington preferred Neptune.Footnote 14 The figure is certainly holding a trident and although Neptune is not a particularly common subject for small bronzes — this would be the only such figurine from Britain — he does appear in small numbers on the Continent.Footnote 15 Two figurines, M2 ( fig. 4f) and M4 ( fig. 4e), are particularly difficult to identify. Figurine M4 is called ‘uncertain Celtic’ by Boon, but he notes that Anne Ross identified it as Mars and this attribution was also accepted by Aldhouse-Green.Footnote 16 The two attributes which led to the identification of this figure as Mars — the raven-topped helmet and the ram-horned snake which he holds in each hand — are more fully discussed below. It has also been suggested that figurine M2 could be Mars, although this identification is less certain.Footnote 17 The stance and the helmet are typical of many Mars figurines, including the missing classical Mars M10 from the hoard. Although Mars M10 is nude, Mars M2 is clothed in a tunic with pleated skirt, a style of clothing which is seen on other Mars figurines.Footnote 18 Finally, while figurine M14 is part of the stylistic group that forms the basis of this paper, it is now missing, thus only the eighteenth-century illustration can be referred to and since only the head and upper torso remained it was not possible to identify which deity it depicted.

FIG. 4. Figurines from Southbroom: (a) Neptune; (b) Mercury; (c) Sucellus; (d) Vulcan M13; (e) Mars M4; (f) Mars M2; (g) Minerva; (h) Mother Goddess M7. (Reproduced by kind permission of the Trustees of the British Museum)

FIG. 5. Sucellus from Chalon-sur-Saône, France. (After Armand-Calliat Reference Armand-Calliat 1937 , pl. XIII)

THE STYLE OF THE SOUTHBROOM FIGURINES

An initial glance at the Southbroom figurines reveals certain immediate similarities between them: the overall plain, somewhat stylised execution; the stance with the legs parallel and knees slightly bent; small feet with no toes depicted; arms which are held out rather awkwardly from the body; the deeply socketed eyes of some pieces and the deep folds of the clothes. They are also all similar in size, ranging from c. 96–108 mm in height. There are, however, many other details which unite these pieces. While Mercury, Vulcan M13, Sucellus and the unidentified figurine have deeply socketed eyes, the Mother Goddess, Minerva, Mars M2, Mars M4 and Neptune have rather unusual moulded, almond-shaped eyes. All have broad wedge-shaped noses and small mouths which are formed by a short, straight moulding. Male deities Vulcan M13, Mars M4 and Neptune all have a raised moulding around the chin to represent the beard. The bristles are indicated by small dimples over the chin on Vulcan M13 and notches on Mars M4, while the beard on Neptune is not detailed ( fig. 6). Although Sucellus does not have this moulding, he does have dimples representing a beard on his chin.

FIG. 6. The beards on: (a) Vulcan M13; (b) Mars M4; (c) Neptune; (d) the Dragonby Mars. ((a)–(c) Reproduced by kind permission of the Trustees of the British Museum; (d) Reproduced by kind permission of North Lincolnshire Museum Service)

Mercury, Minerva and Mars M2 all wear hats or helmets, the brims of which are moulded as a short ridge directly from the head with no indication of hair underneath. The remaining figurines have a similar moulding at the edge of their hair, which gives them the appearance of wearing a cap. The hair framing the faces of Vulcan M13 and Sucellus is in moulded knobs, while that of Mars M4 is an incised fringe which matches the decoration of his beard. The hair of the Mother Goddess is drawn to the back of her head in deep mouldings, with a flat, round bun at the back which is placed quite high on the head. The smooth top of the head on Sucellus suggests that he is wearing a simple cap. However, the Sucellus from Augst has hair that curls around his face to form a slight corona, while the back of the head is plain and the Southbroom Sucellus could be following that style.Footnote 19 In addition, the figure from Chalon-sur-Saône has rather knobbed curls around his face and a belted waist ( fig. 5), both similar attributes to those on the Southbroom figurine.Footnote 20 Mars M4 wears a headdress or helmet depicted by a moulded strip from the top of the head to the nape of the neck, on top of which is a pedestal mounted by a bird, of which the head is missing. An actual helmet surmounted by a bird comes from a wealthy grave in a cemetery at Çiumeşti, Romania, which was dated c. 240–130 b.c., although the helmet itself is of slightly earlier date.Footnote 21 Raven-topped helmets also appear on a stone pillar from the Mavilly (Côte-d'Or) shrine and birds of prey, possibly ravens, are depicted on the silver Gundestrup cauldron from Denmark.Footnote 22 Two altars from Kings Stanley (Glos.) show Mars with a spear, shield, and sword, and a helmet which Ross suggests is topped by a raven, but others believe it is a plume and this does seem more likely.Footnote 23 Apart from the martial association of the warrior's helmet, the raven in the Gallo-Roman world is associated with Mars the healer and is shown with a priest on the Mavilly relief. Finally, the raven is also depicted on a relief showing three genii cucullati and a fourth male figure from Lower Slaughter (Glos.).Footnote 24 It would, therefore, appear that the raven was associated with various deities, including Mars, in Roman Britain if not before. The importance of the raven in the ritual life of Iron Age and Roman Britain is further evidenced by the inclusion of raven bones in deliberately placed deposits at a number of sites during those periods.Footnote 25

The clothing worn by the various figurines in the group also exhibits stylistic patterns. Mercury and Neptune both wear drapery which extends in angular folds from the left shoulder to the right knee. The drapery finishes in an unusual position very high on the left hip, and in Mercury's case exposes his left buttock ( fig. 7a). The Mother Goddess, Mars M2, Mars M4 and Sucellus all wear a plain tunic above a pleated skirt. The skirt pleats are shown as long, straight mouldings with no indication of movement either in the clothing or the body underneath. The use of deep moulding for pleats can be seen on many other provincial figurines and the use of this patterning, especially for drapery and hair, is a characteristic of Romano-British stone sculpture.Footnote 26 All of the male skirts finish above the knee, while that of the Mother Goddess is rather more modest and extends to mid-calf length. Such a long skirt is also seen on the stone figure from Fishbourne.Footnote 27 The plain upper garment worn by Sucellus unusually opens at the back and his skirt has an overfold decorated with short vertical incisions along the upper edge ( fig. 7b). Many other depictions of Sucellus show him wearing a simple jacket which is closed at the front by a belt, sometimes with a thick fold of fabric over the belt.Footnote 28 Boon suggested that the jacket might represent a protective leather garment worn by an artisan, an item which would be appropriate for the hammer god.Footnote 29 Vulcan M13 wears the attire seen on many other figures of this type: a pleated skirt, topped with a tunic which is fastened on his left shoulder, leaving the right shoulder uncovered. The unidentified figurine also wears a simple tunic on his upper body, but his lower body is missing so it is not possible to say whether he wore a pleated skirt. Minerva appears to be wearing a plain tunic which extends to near her knees ( fig. 4g); the lower part of the figurine is missing, but there is no indication of a pleated skirt. She also wears what appears to be a short cloak across her shoulders, which narrows to its lowest point in the mid-chest and back. Perhaps this was meant to represent the aegis often worn by Minerva.

FIG. 7. The rear of (a) Mercury and (b) Sucellus. (Reproduced by kind permission of the Trustees of the British Museum)

All of the figurines hold, or would have held, attributes, except for the Mother Goddess whose hands are placed on her belly ( fig. 4h). The hands are all simple shapes, resembling mittens when extended or sockets when curled, usually with grooves indicating fingers. The lengths of the arms are not always anatomically correct; for instance the upper arms of Minerva and Mars M2 are too short. While some of the figurines are missing their attributes, others retain theirs. Mercury, as usual, has his purse, but it sits on top of his fist, and in his left hand instead of a caduceus he holds a patera ( fig. 4b). Although not a common attribute of Mercury, the patera is occasionally associated with him and two other examples are known from London and the Isle of Wight.Footnote 30 Mercury is usually depicted holding his purse in one of two ways: on top of his palm or clutched with the bag hanging below the fist. The small pointed knob on top of Mercury's purse, as seen here, is often found at the base of hanging purses, while sometimes a flat knob is depicted at the top of the purse held on the palm.Footnote 31 Of particular relevance here is a Mercury from Orbe (Vaud), Switzerland, which shows Mercury with his hand clasped around the neck of the purse in the same manner as the Southbroom figure, but although the shape is the same, the purse hangs below the fist.Footnote 32 Thus it might be that the craftsman was familiar with both styles of purse, but slightly misinterpreted them here. However, Henig has also suggested that this is not a purse at all but a rattle, citing that from the Felmingham hoard.Footnote 33 While an interesting idea and one that would not be completely out of place in the rather eclectic mix of attributes present in the Southbroom group, it seems more likely that the object is in fact a purse.

Attributes are often used to identify figurines, but they do not always help with the Southbroom figurines owing to the use of unusual objects or the way in which the attributes are depicted. The ram-horned snakes of Mars M4 are not seen accompanying any other figurines in Britain ( fig. 4e), although this creature is associated with both Mars and Mercury in Gaul.Footnote 34 Depictions of ram-horned snakes do occur in Britain, such as the two forming the legs of the god Cernunnos on a stone plaque from Cirencester and the snake that winds its way around an altar from Lypiatt Park (Glos.).Footnote 35 It is interesting to note that the two attributes of Mars M4 — the raven-topped helmet and the ram-horned snakes — are also both found on a pillar at the Mavilly shrine in France.Footnote 36 Finally, Mars M2 holds an unidentified object in his left hand, a small cylinder with a cone-shaped top ( fig. 4f), but while his right arm is raised to hold an attribute, such as a spear, the hand is missing. The figure also wears a curious cap with a long curling tip which is perhaps meant to be a crested helmet, yet it in no way resembles the helmet worn by Minerva. Although the tip could simply be a casting sprue which was not removed, the helmet does appear to have been pointed or crested.

This examination of the Southbroom figurines shows that, although broadly united in a similar style, each of the figurines has unique details which not only make it stand out in this group, but also more generally from all others in Britain. They include elements which are classical, although individual, in style such as the purse and patera of Mercury or the style of the hair with the high bun of the Mother Goddess. However, a more Romano-Celtic style is seen in the raven-topped helmet and ram-horned snakes of Mars M4 or the jacket that fastens at the back of Sucellus. Although both of these figurines are unparalleled elsewhere in Britain, it is worthwhile considering whether there are any other figurines in Britain which exhibit a similar range of features to the Southbroom figures and which may, therefore, have been produced in the same workshop.

OTHER FIGURINES IN THE SOUTHBROOM STYLE

The first figurine to be considered is a Vulcan found by a metal-detectorist in North Bradley (Wilts.) ( fig. 8a).Footnote 37 This figure is rather stockier than the figurines in the Southbroom hoard, but does share some similarities with them, including the position and style of the legs, the straight pleats of the skirt, and the awkward depiction of the arms with simple socketed hands. The use of a raised moulding to depict the beard is perhaps more significant, since this is not a feature commonly seen elsewhere in Britain other than on the Southbroom figurines. The bristles and hair underneath the pileus of the North Bradley Vulcan are depicted by short s-shaped grooves. However, unlike the Southbroom figurines, the pleats of his skirt are decorated with horizontal hatching at the front and his eyes and mouth are more clearly defined. Henig notes the similarities between this figurine and those in the Southbroom hoard, but also points out that the depiction of the beard is similar to that on a Mars from Dragonby ( fig. 6d).Footnote 38 The Dragonby Mars also has a small slit mouth, wedge-shaped nose and almond-shaped raised eyes; he has a full beard which leaves only a small part of the face uncovered and the hair of his beard and on his head is depicted by short, deep stab marks ( fig. 8b). The Dragonby figurine, like the North Bradley Vulcan, is quite stocky, and like the Southbroom figurines has a rather thin and flat profile (see fig. 8c). The stylised depiction of his helmet is not unlike that seen on the Minerva or Mars M4 from Southbroom and like Mars M4 there is a narrow strip down the centre of the head. The Dragonby helmet has a narrow pointed ridge at the front and back and a deep groove along its length indicates the crest. Henig also highlights the belt worn by this figurine, but the belt on the North Bradley Vulcan is less obvious. In fact, all of the Southbroom figurines have a well-defined fold in the fabric between the tunic and skirt, and on two figures (Sucellus and Mars M2) the fold does appear rather like a belt.

FIG. 8. (a) Vulcan from North Bradley (Wilts.); (b) Mars from Dragonby (North Lincs.); (c) Profiles of Mars figurines from Southbroom (M4) and Dragonby. ((a) Reproduced courtesy of Wiltshire Museum, Devizes; (b) and (c right) Reproduced courtesy of North Lincolnshire Museum Service; (c left) Reproduced by kind permission of the Trustees of the British Museum)

Two other figurines from the South-West also show affinities to the Southbroom pieces: a Mother Goddess from Henley Wood temple (Somerset) and a boar from Motcombe (Dorset). The Mother Goddess is a highly stylised figure depicting a nude standing woman with pendulous breasts ( fig. 9a). She stands with her legs together and they are defined by a vertical depression on the front and the back of the piece. Her arms are at her side with the hands clasped across her belly, thus in the same stance as the Mother Goddess from Southbroom. While the Southbroom Mother Goddess has her hair drawn back into a bun, the Henley Wood Goddess has a plaited band around her head. The latter's face is extremely worn, the nose and mouth are just visible, and the only real remaining features are her deeply socketed eyes, the left one of which still contains traces of fill.Footnote 39 Around her neck she wears a rilled torc and it is this last detail in particular that links the Mother Goddess with the boar, or pig, from Motcombe.

FIG. 9. (a) Mother Goddess from Henley Wood temple; (b) Boar from Motcombe; (c) Rider from Ashdown (Oxon.). ((a) © 2013 North Somerset Council and Somerset County Council Heritage Service; (b) Reproduced courtesy of Dorset County Museum; (c) Reproduced by kind permission of the Trustees of the British Museum)

The Motcombe boar is similarly stylised, with a rather cylindrical body which tapers slightly towards the neck ( fig. 9b). The face has a long, slightly tapering snout, and between the ears, now broken, are three grooves which Henig interprets as tufts of hair.Footnote 40 Like the Henley Wood Mother Goddess this boar has deeply socketed eyes which may have held insets and around the neck he wears a decorated torc. Torcs are not often seen on metal figurines in Britain, and while there are two examples, both of Mercury, with a separately cast silver or gold torc,Footnote 41 only one other figurine, a rider from Ashdown (Oxon.), has an integrated torc around the neck ( fig. 9c).Footnote 42 There are also stone images of figures wearing torcs in Britain, such as that from Wellow (Somerset) which depicts a woman dressed in a long pleated tunic, much like that seen on the Southbroom Mother Goddess.Footnote 43 The Ashdown rider is another stylised figurine which exhibits a similar style to that of the Southbroom figurines. In addition to the torc, he has close-set socketed eyes and a rather flat, almost featureless face in which the slit mouth is just visible; similar to the features seen on the Henley Wood Mother Goddess. Like the helmet-wearing Southbroom figurines, the rider has a moulded helmet, with a brim forming a ridge around the head, but unlike the Southbroom figurines, he does have hair showing on his forehead. The helmet also has a crest, which is in the form of a narrow ridge along the back of the head, much like those seen on the Dragonby Mars and the raven-topped helmet of Mars M4. The clothing is very simply depicted, and does not have any deep folds or pleats, but the cloak is shown by a deep moulding, an effect common to the group as a whole and in particular to that on the Southbroom Minerva. The edge of the cloak is decorated with short notches, and similar nicks also decorate the facets of the tunic along the top of the thigh from waist to knee.

THE ‘DOG MONSTER’

Another small group of figurines examined here is that of the ‘dog monster’, canines with fierce features and long protruding tongues. One of the missing figurines from the Southbroom hoard was published as Anubis by Boon,Footnote 44 but is now thought more likely to be another form of dog-like creature. The illustration published by Musgrave shows a powerful standing creature with protruding tongue, a mane from the back of his head to shoulders, and rough bristled coat across the forelegs, neck and shoulders ( fig. 3, no. 16).Footnote 45

The other examples in this group are all seated and include two figurines from Llys Awel (Conwy).Footnote 46 These two creatures have open mouths from which protrude tongues, one of which is particularly long and wavy ( fig. 10). Their bodies are decorated with an incised pattern of cross-hatching and they have a dorsal ridge worked with a herringbone pattern. Their maleness is also emphasised in the depiction of the genitals. Other objects found with these dogs are another highly stylised dog in La Tène style, a Mercury figurine and three plaques, two of which also depict dogs.

FIG. 10. Dogs from Llys Awel, Conwy. (Reproduced by kind permission of Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales)

Another dog with a dorsal ridge, probably from the shrine at Woodeaton (Oxon.), has been described as a wolf-god ( fig. 11a).Footnote 47 This muscular beast has a small human figure protruding feet first from its mouth, rather like the tongues on the Llys Awel dogs, and a patterned mane down its back. Depictions of the androphagous carnivore are found most often in north-eastern Gaul and apart from wolves or dogs can be lions, Cerberus, sphinxes, griffins or wild boars. Many occur in stone, such as the Tarasque of Noves (Bouches-du-Rhône), a seated lion just over 1 m tall with its front paws resting on two bearded, severed heads and an arm protruding from its sharply toothed mouth.Footnote 48 One image which has been compared on various occasions to the Woodeaton figure is the she-wolf on a second-century pediment from Arlon, Belgium.Footnote 49 However, there are also three examples in bronze: one from Fouqueure (Charente) ( fig. 11b) and two from an excavation at Chartres (Eure-et-Loir).Footnote 50 The Chartres examples are interesting, since one is of a naturalistic dog or wolf very like the examples from Woodeaton and Fouqueure, while the other is larger and more stylised, with a roughly depicted mane around its neck. They were recovered from what appears to be a ritual site of first- and second-century date in which deposits of complete pottery vessels, animal and human bones were deposited in wells and pits.Footnote 51 The object protruding from the mouth of the second creature is less obviously a human figure. Similarly, perhaps the Llys Awel dogs represent a development from these man-eating creatures where the body has become a tongue. A further link between the Chartres and Llys Awel figurines is provided by their deposition: the Chartres figurines were ritually deposited in a well, while the Llys Awel dogs were found near the hillfort of Pen-y-Corddyn deposited with other material — including the Mercury figurine and plaques mentioned above, as well as over 500, mainly fourth-century, coins — at a spring.Footnote 52

FIG. 11. (a) The wolf-god from Woodeaton (Oxon.). Scale 1:1; (b) The carnivore from Fouqueure, France. ((a) © Trustees of the British Museum; (b) Chauvet 1901, fig. 10)

The two factors common to these images are the large size of the animal in relation to the small human and the limpness of the human body. These have led to the suggestion that the wolf represents a divine image (either a deity itself or a deity in animal form) associated with the underworld.Footnote 53 Dogs are often associated with healing, but it is their link with the gods of the underworld such as Pluto and Serapis that is perhaps more relevant here, while Cerberus was the hound with multiple heads which guarded the gates to Hades. Their association with death and resurrection is also demonstrated by the deposition of dog figurines in clay or bronze in graves and their appearance on funerary monuments.Footnote 54

DISCUSSION

The figurines in the Southbroom hoard consist of examples in both classical and stylised forms, but how does the hoard composition compare with the totality of figurines from Britain? Table 1 lists the figurines of each style. It is immediately apparent that the majority of the figurines are male. However, the three female figurines comprise 21.4 per cent of the group, which is in fact the same proportion of female figurines for the entire British assemblage.Footnote 55 It is interesting that there is no Mercury or Hercules, the two most common male figurine deities in Britain, among the classical figurines, although there is a Venus, the second most common female deity. On the other hand, there is a Mercury and a Minerva among the stylised figurines — the most common male and female deities in Britain. Considering the Southbroom collection as a whole, it would seem to represent a rather idiosyncratic group. Vulcan is not particularly popular in Britain, and yet there are two here, one in each style. Neptune and Sucellus represent the only examples of their type in Britain. Mars, with two examples and a possible third, is the most common in the group and it is interesting to note that the depictions are extremes of their type: the classical piece showing the nude Mars with crested helmet, while the provincial Mars is depicted with ram-horned snakes.

TABLE 1 Figure TYPES IN THE SOUTHBROOM HOARD

Total = the number of figurines of that type recorded in Durham Reference Durham2012 from Roman Britain.

The deities making up the Southbroom hoard invite questions regarding the origin of the figurines. Depictions of Sucellus, the hammer-god, are fairly common in stone and bronze in Gaul, but not in Britain. In fact the only other object from Britain definitely associated with Sucellus is a silver finger-ring from York engraved with a dedication to the god,Footnote 56 although a sceptre-binding from Farley Heath (Surrey) is thought to show the god along with a raven, dog and stag.Footnote 57 However, it should be noted that Sucellus is the only Gallo-Roman deity regularly depicted in bronze, and only Epona — a Gaulish fertility deity often depicted riding or accompanied by horses — appears with similar frequency but on stone.Footnote 58 The homogeneity of Sucellus' image as a mature man, with long curly hair, beard, belted short tunic and breeches and carrying his two attributes — the hammer and small pot — is noted by various authors and this image remains largely fixed in the bronze figurines, although it is less conservative on stone depictions.Footnote 59 Stephanie Boucher, in her various discussions of Sucellus figurines, notes that it is more common for figures to have the left arm raised and the right holding the vessel, and that sometimes this stance is reversed, but she does not mention the stance of the Southbroom, Augst and Chalon figures (apart from in her catalogue description of the Chalon figurine). However, she does illustrate a figure holding the pot in his left hand, like the Augst and Chalon figurines, and with his right hand only very slightly raised.Footnote 60

Paul-Marie Duval notes that in his tunic and breeches Sucellus is dressed in clothes suitable to the climate in which he is found, unlike the Mediterranean dress of the classical deities.Footnote 61 Yet Boucher points out that the Gallo-Roman Sucellus conforms to the conventions of the Roman pantheon in his stance and attributes. The pot, like Jupiter's thunderbolt or Mercury's purse, symbolises direct divine power in their relations with the human world, while the hammer, like the sceptre or caduceus, is a symbol of the god's power over his domain.Footnote 62 Sucellus is a god with various guises, as a sky god, god of prosperity, war and the underworld, and it is in this last guise that he has been linked to Dispater.Footnote 63 On stone reliefs Sucellus is sometimes depicted together with a dog, an animal which often accompanies Silvanus, with whom Sucellus is also at times joined.Footnote 64 Ernest Black associates the ritual deposition of dogs in South-East England with the worship of the god Sucellus in his role as god of the underworld, thus linking them not to healing cults but to the ‘devouring and transforming nature of the god’.Footnote 65

It is not just Sucellus who provides a link with Gallo-Roman beliefs in the Southbroom hoard: the ram-horned snake, raven-topped helmet and carnivorous dog are also found there. The earliest appearance of the ram-horned snake is on the silver Gundestrup cauldron where it is seen on several panels, including leading a band of warriors and being held by a seated Cernunnos. Although the place of origin of the cauldron has been much debated, it has often been argued that some of the symbols, including the ram-horned snake, have a Gaulish origin.Footnote 66 The creature also appears in association with Cernunnos on several Gaulish statues from Sommerécourt (Haute Marne), Yzeures-sur-Creuse (Indre-et-Loire) and Crêt Chatelard (Loire).Footnote 67 Garrett Olmsted calls the ram-horned snake ‘the Gaulish mythical animal “par excellence”’, since it is most common in central and north-east France, but is rarely seen outside that region.Footnote 68 It is also on the Gundestrup cauldron that we find early depictions of bird-topped helmets like that adorning the head of Mars M4.Footnote 69 Finally, there is the carnivorous beast, found predominantly in Gaul but also in Britain, and perhaps serving as the inspiration for the dogs found at Llys Awel and in the Southbroom hoard.

This wealth of Gaulish inspired images might indicate an origin in that province for the figurines of the Southbroom hoard, but it must be noted that all of these images also occur in Britain, often on sites not far from Southbroom itself. The similarities between the Southbroom, North Bradley, Henley Wood and Motcombe figurines in particular suggest the presence of an artistic tradition based in South-West Britain. However, one must always take care when comparing pieces on stylistic grounds, particularly when they are based on simple or stylised features. As Catherine Johns has pointed out, many features such as large eyes and a wedge-shaped nose are characteristic of naïve art more generally.Footnote 70 For instance, one might consider other figures which bear some similarities to the South-Western group, in particular two figures of Mars from London and Tiel in the Netherlands.Footnote 71 Both wear a helmet, tunic and cuirass with simply depicted pleats on the skirt and basic modelling of the body. Although, like the South-West group, they fall within the slightly stylised form common to Britain and Gaul, the specific details of the body and clothing do not belong to those characterising the South-West figurines. The fact that this small group is based primarily within a limited geographical area ( fig. 1) does suggest that it represents the work of a limited number of artisans operating within a particular tradition. Jennifer Foster has suggested that metalsmiths producing high quality goods in Iron Age Britain may well have been itinerant and that they would have produced a group of pieces in a single episode at a site, such as at Gussage All Saints (Dorset).Footnote 72 The large number of unique pieces within the Southbroom hoard might well represent such an episode. The single outlying figure of the Dragonby Mars, which displays a number of the features characterising this group, could be the result of trade or the product of an itinerant metalsmith working within this tradition.

In any discussion of figurines one must consider their portability. As small personal objects, they could be transported easily with their owner, thus their place of deposition need not relate closely to their place of origin. In addition, their small size means that figurines could have easily been held in a hand, and the wear on some figures, in particular that on the Henley Wood Mother Goddess, is seen as evidence for the repeated handling of a much-loved or respected object.Footnote 73 Aldhouse-Green emphasises the link between the image depicted in the figurine and the context and use of the piece, which may have changed with time, location and owner.Footnote 74 However, these factors need not be limited to small objects that can be transported in a pocket, but equally apply to larger pieces such as the Silchester eagle, that also had a long and changing life history and, like the Henley Wood figurine, may have been deliberately deposited.Footnote 75

Unfortunately, the majority of the pieces under discussion come with little contextual information which might help to determine whether they are linked chronologically as well as spatially. The Henley Wood Mother Goddess was excavated from a fourth-century layer of metalling in the temple precinct, although Henig would assign the piece an earlier date, perhaps in the first century a.d. Footnote 76 The Motcombe boar was found by chance on the site of Duncliffe Hill with a figurine of Fortuna.Footnote 77 Henig offers a date in the second century for the Fortuna, while he believes that the boar is somewhat earlier, probably dating towards the end of the Iron Age.Footnote 78 He also notes that the location, on the spur of a hill with views across a valley and a spring on the lower slopes of the hill, is typical of many Roman temple sites in this area, although there is as yet no evidence for such a structure other than, perhaps, these figurines.

The Southbroom figurines are also without context details, but it is interesting to note that like the Motcombe boar, the figurines considered in detail here were found with figurines of classical, Graeco-Roman style and a coin of Severus Alexander dated to a.d. 222–35. Footnote 79 However, as Henig notes, the presence of the coin does not necessarily date the figurines, which he believes are likely to be earlier. On stylistic grounds Henig dates the North Bradley Vulcan before the end of the second century.Footnote 80 Many of the objects from Gaul displaying the same imagery are also dated to the early Roman period and the Gundestrup cauldron slightly earlier, perhaps in the first century b.c. Footnote 81 Thus at the moment the best date one can give for this group is some time in the early Roman period. The Southbroom figurines in particular represent a time when native traditions from the Late Iron Age were merging with the ideas introduced by the Romans, in this case to produce a new local style. However, the use of style in both the dating and analysis of Romano-British art is highly debated.Footnote 82 Henig, in attributing the figurines under discussion here to the early Roman period, is equating the simple and ‘Celtic’ style with that early date. However, one should perhaps place as much, if not more, emphasis on the themes depicted both in individual objects and groups in which the use of Late Iron Age and Gallo-Roman motifs might signal deliberate choices influenced, in part, by both the various artistic styles to which Romano-British artists would have been exposed and their attitudes towards their Roman conquerors.Footnote 83 As objects associated with ritual and religion, the motifs used on figurines are also important indicators of the adoption of the Graeco-Roman pantheon and practices associated with Roman religion. Here also there has been much debate over the nature of syncretism between Celtic and Roman religion, with some seeing it as a largely benign process in which the similarities between Celtic and Roman traditions allowed change and growth within native religious practice.Footnote 84 Jane Webster in particular has questioned this idea and, while she agrees that Romano-British religion saw an adaptation of introduced religious ideas, she feels that the changes were conducted within the context of an imperial situation in which the native population were involved in a power struggle with the dominant Roman incomers and she uses the term creolisation — the relationship between material hybridity and power inequality — to describe the process.Footnote 85 The fact that the arguments presented by authors such as Aldhouse-Green and Webster are in fact centred on evidence from Gaul not only indicates the scarcity of evidence from Britain, but also serves to highlight the regional nature of Romano-Celtic beliefs. This is the focus of recent work by Martin Goldberg who thinks that the local character of much of the evidence is bypassed in order to create a widespread syncretistic model of Romano-Celtic religion. Instead he prefers to use the term vernacular to indicate the essentially local and non-élite character of native Romano-British beliefs.Footnote 86 The figurines of the Southbroom hoard and the Llys Awel dogs could certainly fit within a regional group in which motifs such as the ram-horned snake, raven and carnivorous beast are being utilised.

The Southbroom hoard stands out from others containing figurines in Britain, not only because of its size (it contains the largest number of figurines), but also its mix of highly classical and idiosyncratic pieces.Footnote 87 Figurines have been found in four other hoards from Willingham Fen (Cambs.), Felmingham Hall (Norfolk), Ashwell (Herts.), and Barkway (Herts.) (Table 2). There is no indication of a settlement or temple site in the vicinity of the Southbroom hoard, or the hoards from Willingham Fen, Felmingham Hall and Barkway. The Ashwell hoard, however, was found on a Romano-British settlement that also has substantial evidence for ritual activity.Footnote 88 Although, unlike the Southbroom hoard, the figurines form only a small part of these other hoards, the one factor common to them all is the presence of a mixture of objects associated with both Romano-Celtic and Romano-British religion. The hoard from Willingham Fen includes two horse and rider figurines, a Mars figurine, a raven, an owl and three masks, while that from Felmingham Hall contains a ceramic vessel in the shape of a bronze cauldron, a Lar figurine, a bronze head of a possible Celtic deity, a head of a sun god, a miniature wheel, three masks and two possible raven attachments.Footnote 89 Although the objects from Ashwell are themselves typically Romano-British, the use of a Fortuna figurine and plaques depicting Minerva in veneration of Senuna — who was presumably a local Romano-Celtic deity — links the pieces to those under discussion here.Footnote 90 Finally, from Barkway the Mars figurine and plaques are again more typically Roman in style, but one plaque is dedicated to the Romano-Celtic deity Mars Toutatis.Footnote 91 Since the horse and rider — which is particularly common in eastern central England — is thought to represent a local version of Mars,Footnote 92 all of these hoards, except for that from Ashwell, have associations with Mars (including figurines of the deity himself) and/or birds and animals with chthonic attributes — in particular the raven and the dog. It is only at Llys Awel that the dogs may take on a healing role rather than a chthonic one.

TABLE 2 FINDS FROM HOARDS

The Southbroom hoard is also unusual in comparison with other hoards from elsewhere in Europe. Kaufmann-Heinimann surveyed hoards containing figurines and there are numerous examples containing provincially produced figurines, but only a few contain figurines of deities who do not belong to the Graeco-Roman pantheon and these are Epona, Rosmerta (a Gaulish deity often associated with Mercury), Naria (a local goddess from western Switzerland, probably associated with fertility), and Artio (a local goddess of agriculture and the forest from the Rhine-Moselle area who is associated with the bear).Footnote 93 Like the Southbroom hoard, the composition of the hoards containing these regional deities is slightly unusual. Epona and Rosmerta were found together in a hoard from Champoulet (Loiret), which also included an Apollo, a less common deity in bronze, and a bull. At Reims (Marne) Epona was found with Aesculapius, who is rarely depicted in bronze, and an unusual figurine group consisting of Venus accompanied by two miniature figurines of Cupid and Priapus. Finally Naria and Artio were found together with a Jupiter, Juno, Minerva and Lar at Muri, Switzerland. Thus these Continental groups also manifest a rather unusual combination of Graeco-Roman deities in association with regional deities, but stylistically all of the figurines follow a classical form in their depiction, rather than using the individual style and attributes seen in the Southbroom figurines. Only a hoard from Neuvy-en-Sullias (Loiret) departs from this norm and contains a group of highly individual figurines in combination with others in a classical style.Footnote 94 This hoard was found during quarrying in a pit lined with brick. The figurines in classical style include Mars and Aesculapius and a carriage fitting with a figurine of a child Hercules under an arch of vines. There are also animal figurines — two bulls, two boars, a stag and a horse — as well as three saucepans and three votive leaves. However, the figurines of particular interest here are the five men and four women depicted in a unique style. Most are naked, with long torsos, large hips, short legs and tiny feet in comparison to their overly large hands. They appear to be dancing or, with their waving arms and tilted heads, perhaps in a state of religious fervour. The combination of the poses and anatomical oddness give the pieces an effective other-worldly quality. If the large figure clothed in a long-sleeved tunic, with his arms held out in front of him were a priest, then this would leave four dancing couples in the group.Footnote 95 Thus this hoard compares well with the Southbroom group in terms of its use of both classical and native pieces. The Gallo-Roman deities in these Continental hoards include both those with an international reach (Epona and Rosmerta) and those with only a local range (Naria and Artio). Similarly, the Sucellus from Southbroom shows allegiance to a well-known Gallo-Roman deity, while perhaps the putative Mars M2 and M4 could represent a local deity or deities. In addition, the local deities in the Continental hoards show stylistic uniformity and those in the Neuvy-en-Sullias group are almost certainly the product of a single workshop, while the Naria and Artio figurines from Muri also show stylistic details which suggest they are the product of a single workshop.Footnote 96

To conclude, the figurines of the Southbroom group include both Roman and Romano-Celtic deities, as well as a Romano-British style which combines the use of Late Iron Age trends, such as stylisation and the torc, with the Roman tendency towards naturalism and attributes such as the patera. The variety of deity types, but consistency of style, exhibited by the South-West group indicates a distribution which is limited to production by one or two artisans or workshops. As such, production by a single bronzesmith would necessitate a narrow chronological range for the pieces, and the Iron Age influences would suggest a date earlier in the Roman period. Finally, the fact that the figurines of this South-West group and the carnivorous dogs are often found in association with typically classical pieces, suggests a certain inclusivity in their use, and one in which worshippers took on a variety of religious influences, both local and imported.

APPENDIX. DETAILS OF THE FIGURINES DISCUSSED IN THE TEXT