In 1663 Giustiniano Martinoni, in his updating of Francesco Sansovino’s Venezia città nobilissima et singolare, wrote of one of Venice’s most important ornaments, its theatres. As Martinoni explained,

In Venice there have been erected four principal theatres, one of them on the Fondamente nuove (called SS. Giovanni e Paolo, as it is located near there) built by Giovanni Grimani. … He also built another theatre at S. Samuele. The other two theatres are at S. Salvatore, and at S. Cassiano. In the [Theatre] at SS. Giovanni e Paolo during carnival they perform musical operas with marvelous mutations of sets, majestic and most rich costumes, and miraculous flights; one sees on a regular basis resplendent heavens, gods, seas, palaces, forests, and other lovely and delightful images. The music is always exquisite, offering the best voices to be heard in this city, and also bringing singers here from Rome, Germany, and other places, especially women, who with their beauty, the richness of their costumes, and the charm of their voices, and with the interpretation of their roles, bring about stupor and wonder.1

‘Public opera’ famously commenced in Venice in 1637 at the Teatro S. Cassiano, owned by the Tron family, with Andromeda (libretto by Benedetto Ferrari, c. 1603–1681; music by Francesco Manelli, 1595–1667). In this account, that theatre’s foundational role in the history of opera scarcely matters to the author, for the most important opera theatre in Venice in 1663 was SS. Giovanni e Paolo. The other opera theatre, S. Salvatore (also known as S. Luca), had only presented its third season and, quite possibly, its first one of excellence. (The man in charge that year was Vettor Grimani Calergi, cousin to Giovanni Grimani, and a seasoned connoisseur of music, theatre, and singers).

Martinoni’s description speaks of opera as practiced in Venice in 1663, rather than retelling the two-and-a-half decades now past as the opera chronicler and librettist Cristoforo Ivanovich would do two decades later in his Memorie teatrali di Venezia (1681; 2nd edn. 1688; Ivanovich’s book was dedicated to Grimani’s nephews and successors Giovanni Carlo and Vincenzo Grimani).2 Moreover, to the modern scholar the blank spaces between Martinoni’s words reveal something of the fragility of the system, for a number of theatres from the first two decades of public opera were not worthy of mention: S. Moisé (where Monteverdi’s Arianna was performed in 1639), SS. Apostoli, and S. Aponal (also known as S. Apollinare, Aponal in the Venetian dialect), which had operated for seven years in the 1650s. Martinoni’s inclusion of S. Cassiano is, in the end, a nod to its importance in Venice’s theatrical history, as that theatre had ceased to present opera with the departure of impresario Marco Faustini to Giovanni Grimani’s theatre after the 1659/60 season.

Opera at the Grimani theatre began during S. Cassiano’s third year – the 1638/9 season – and Giovanni Grimani’s dedication to Venice’s operatic enterprise was unfailing. His passion for his theatre must have contributed a sense of stability to Venice’s burgeoning but shaky opera industry. Indeed, the family seems to have made a conscious decision that their enterprise would not fail. As far as we know, of all the Venetian theatres operating until the time of Giovanni’s death, only SS. Giovanni e Paolo remained more or less immune from notarial and legal disputes. This is not to suggest that the Grimani theatre did not suffer financial or artistic setbacks: no theatre could have been immune from those difficulties. Rather, Giovanni Grimani must have resolved to settle nearly all claims internally. This level of commitment is suggested by his tax declaration in 1661 for the theatre, two years before Martinoni’s encomium to him:

In calle della Testa, a theatre built by me in these last years so that I might mount operas, with its contiguous house where the theatre custodian lives, and which also serves for the convenience of the musicians. And so that this theatre might render me some profit, I spend significant amounts of money in large salaries to singers that I bring here from foreign lands. And as is well known to Your Excellencies, at times I suffer considerable losses … thus I declare that according to the expenses, when the theatre is in operation I can hope to gain two hundred ducats.3

Giovanni Grimani might be looked upon as one of the heroes of what had become that staple of Venetian entertainment – public, commercial opera. Financing and running these theatres was at best unpredictable: S. Cassiano, for instance, saw many problems during its first decade.4 When Francesco Cavalli (1602–1676) agreed in 1648 to come back to the theatre, then operating under a new management team, he did so with extraordinary perks, a sure sign that he had wavered, given that his librettist, Giovanni Faustini, was by then mounting operas across town at S. Moisé.5 For much of the century, S. Cassiano would present opera only sporadically, and it never again matched the consistency and excellence it boasted during its first decade of operation.

Although publicity such as that provided in libretti would have served to broadcast the allure of public opera, the timing of the opera season during the carnival itself increased the odds of success, as this event occurred when the city teemed with visitors, and at a magical time when masks lent an aura of mystery and excitement to the city: Venice’s tradition of carnival entertainment, and its existing theatres supplied with boxes, made the transition from comedy to the production of opera easier than it might otherwise have been.6 (A secondary season sometimes took place at the time of the Ascension fairs, when the city was filled with merchants from a wide area of Italy).

SS. Giovanni e Paolo, S. Salvatore, S. Cassiano, S. Moisé, and S. Aponal had at one time hosted commedia dell’arte troupes. All of them would eventually be called into service as opera theatres, some of them alternating between comedy and opera. Other occasional opera theatres included the Saloni and the Teatro Cannaregio. Three more theatres, the Novissimo, S. Angelo, and S. Giovanni Grisostomo were built new in order to present opera. What is clear is that each theatre might operate according to a different model and change even from season to season. We have seen how Giovanni Grimani was intimately involved in the running of the theatre (as would be his nephews), though many theatre owners for all intents and purposes removed themselves from the management altogether, relying on impresarios, and sometimes even other noblemen to manage and promote their theatres.

New Theatres

What began at S. Cassiano with the Tron family soon spread to other spaces in Venice. The Grimani family opened SS. Giovanni e Paolo in 1638. In 1640, in advance of the fifth season of public opera in Venice, came the Teatro Novissimo, unique in the history of Venice’s theatrical life: it was built on the grounds of the Dominican monastery of SS. Giovanni e Paolo (so that it was quite near to the theatre that bore that name), not on the property of a private family. The theatre was built, apparently, by Girolamo Lappoli, a Tuscan businessman who had resided in Venice from the early 1630s and formed contacts with Venetian noblemen. In recent decades the theatre has been associated with Giovanni Francesco Loredan’s academy, the Incogniti, to the point that it has been called by some the ‘Incogniti theatre’.7 While it is true that three Incogniti members wrote libretti to be performed there – Giulio Strozzi (1583–1652), the Messinese author Scipione Errico (1592–1670), and Maiolino Bisaccioni (1582–1663) – and that Giacomo Badoaro (1602–1654), one of Monteverdi’s librettists, later had some connection with the theatre, the financial underpinnings of the enterprise are far from clear. Various creditors, from artisans and artists to other ‘benefactors’, deluged the impresario Lappoli with their demands to be repaid. One of Lappoli’s associates was Joseph Camis, a Jewish doctor who had guaranteed the fees of the singer Anna Renzi (c. 1620–d. after 1661) at a time when she might otherwise have gone to sing at a different theatre. Late in the theatre’s life Lappoli attempted to turn it over to Bisaccioni.

For its inauguration in 1641 the Teatro Novissimo presented Francesco Sacrati’s (1605–1650) La finta pazza on a libretto by Giulio Strozzi. This first production was extensively praised (especially in Il canocchiale per la finta pazza published by Surian in 1641). La finta pazza not only made a star out of its prima donna, Renzi, but it became the first Venetian opera to travel not only to various cities in Italy, but also to Paris. The publicity that emanated from the pens of the Incogniti must have helped to increase the viability of the theatre (despite the frequent debts that went unpaid by Lappoli), but it also would have served to augment attendance at the other theatres. Yet, no matter the excellence of its artists and its operas, there was no family to stand behind the theatre: after several years of wrangling between the Dominican friars and the impresario, the Novissimo was torn down, by which time two of its stars, the scenographer Giacomo Torelli (1608–1678) and dancer and choreographer Giovan Battista Balbi (fl. 1636–1654, formerly of S. Cassiano), had moved to Paris.

Also extraordinary was the eventual sharing of personnel between the Novissimo and SS. Giovanni e Paolo. Lappoli later rented the Grimani theatre, and artists such as Torelli and Renzi, who had gained their initial fame at the newer theatre, worked at both, most famously with Renzi’s performance as Ottavia in L’incoronazione di Poppea during the 1642/3 season.

As mentioned above, theatres such as the Teatro S. Moisé (under the ownership of the Zane family for much of the seventeenth century) and S. Cassiano (the Tron theatre), alternated between comedy and opera. S. Aponal, once a comedy theatre (most likely in the late 1620s and early 1630s), rose to great heights under the direction of Giovanni Faustini, and then his brother Marco. But, as Marco later moved on to other venues, S. Aponal eventually ceased to operate altogether in that capacity.8 It was not until the 1670s that two new theatres were built in Venice – each important in different ways and quite opposite in terms of size, repertoire, and management – and both long lived, unlike the Novissimo. They opened in 1677 and 1678, respectively: S. Angelo (built by Francesco Santurini on land owned by the Marcello and Cappello families), then S. Giovanni Gristomo, built by Giovanni Carlo and Vincenzo Grimani to serve as their second opera theatre, a more luxurious and elite theatrical venue. S. Giovanni Grisostomo was known for its ‘high’ libretti and the excellence of its singers. S. Angelo often served as an entry point for young singers, and it offered a wider range of types of libretti.

The Financing of Operas

Commercial opera in Venice began with musicians who had travelled there from other regions, that is, it had not come into being as a result of a local desire to promote a new sort of carnival entertainment. Many of the artists had earlier mounted the festa teatrale Ermiona in Padua (1636; score by Giovanni Felice Sances, c. 1600–1679, on a libretto by Pio Enea degli Obizzi, 1592–1674).9 The production of opera depended on a theatre (and in the case of Venice, all the theatres were permanent rather than temporary structures), a librettist, a scenographer, carpenters, painters, a composer, dancers, and musicians. To this could be added a dedicated impresario, though, during the first season at S. Cassiano, the artists had no need of one, as they served as a self-contained unit. When they needed capital, one of the singers agreed to make a loan of 100 ducats. Surely the company needed much more.

The dedication of the next opera at S. Cassiano, La maga fulminata (libretto and music once again by Ferrari and Manelli) referred to an overall cost of 3,000 ducats, but the company may have recouped much of their ‘investment’ from box rentals and ticket receipts.10 It is likely, however, that Ferrari and Manelli did at some point seek investors from Venetians of various stripes. During the next few years we see evidence of loans from a variety of noblemen. Often the company had difficulty repaying them, and the interested parties would end up in court. In other cases help came not in a formal loan but through a guarantor, who would promise payment when members of a company were short of funds. These guarantors were essential to the success of the opera business, as, for the most part, liquid cash was not available until the season was underway, through box rentals and the sales of tickets and refreshments.11

Some of the early companies were sustained through investments of a small group of partners, as we see in Marco Faustini’s at S. Aponal and S. Cassiano. Here any profits and losses would be shared by the members, which in Faustini’s case varied between cittadini, noblemen, and artisans. Later companies were sustained through a more general financing system called carati, or carats (the purchasers of these carats were called caratadori), whereby a number of investors supported a business scheme, thus spreading among the group any given individual’s profit or loss. This fundamental practice of business in Venice dated back to at least the fifteenth century. At least in theory, it protected both the investors and those in need of payment (in this case the theatre owner, artisans, and all the musicians), and it resembles the practices of academies who sponsored opera theatres in other parts of Italy.12

The box system provided the surest source of income, whether for the theatre owner or for the impresario. Indeed, the fees for individual boxes came to be the source of funds payable to creditors of all types. In the latter part of the seventeenth century, the Grimani brothers, having hundreds of boxes in three theatres under their control, frequently transferred the box income, sometimes to singers, but also to tradespeople or many others who held credits. Eventually the boxes would become an even greater source of income for the theatre owners when they were put up for sale, in essence becoming the property of a buyer who could transfer the box or pass it down to his or her descendants.

While the ‘orchestra’ (ground-floor seats) would be rented by a wide variety of people, both Venetians and foreigners, the boxes were occupied by Venetian nobles (in the prime locations), and, higher up towards the ceiling, less wealthy nobles and a number of cittadini. Some boxes were rented on a more or less permanent basis by visiting dukes such as the Hanover Brunswicks.13 Others were chosen by lot, by the doge himself, for the benefit of ambassadors serving in Venice.14 The boxes offered a modicum of privacy, especially when the spectators wore masks. They also provided an opportune location from which to launch printed sonnets in honour of favourite singers. They might also prove to be places of violence, whether by means of fists or pistols, or places for amorous assignations. The opera box, then, served as a locus for passions of varying kinds.

At S. Aponal, in the 1650s, impresario Marco Faustini personally held the rights to the box income: even if the company lost money over the season, he, at least (rather than his partners), was guaranteed an income. Naturally, he was free, but not required, to reinvest those funds in order to cover debts. But what, or who, was an impresario? He (or she) ‘ran’ the company, arranged for the musicians, and paid everyone involved with the enterprise.15 Yet the responsibilities might well vary from theatre to theatre. In the case of Faustini, the most well-documented impresario in seventeenth-century Venice, his duties varied according to the theatre. At S. Aponal (1651–1657) and S. Cassiano (1657–1660) he pretty much ran the show. Despite the difference in social rank his importance in the company was greater than that of his noble partners. In both cases the theatre owners had little to do with the company other than to see their rental fees well in hand. At SS. Giovanni e Paolo (1660–1663), though, the situation could not have been more different. Here Faustini was not responsible for the rent, and he would have dealt with the most knowledgeable theatre owner in the city. Giovanni Grimani would have had strong views on the singers to be hired and, most likely, the repertoire. During the end of Faustini’s career as an impresario, the owners were the teenagers Giovanni Carlo and Vincenzo Grimani, so that Faustini would have been the one with far greater experience.

Venice continued to welcome other men who ran theatres over long periods of time, such as Santurini and Giovanni Orsato. Impresarios in Venice included artisans, librettists, noblemen, and businessmen, but, generally, except for Francesco Cavalli around the cusp of 1640, not composers, at least until the time of Antonio Vivaldi in the early 1700s.

Making Opera

Librettists of Venetian Opera

During the seventeenth century in Venice, the librettist was not paid by the company. Rather, he reaped the benefit from ticket sales and (it was to be hoped) from a gift from the person or persons to whom he dedicated the work. Dedicatees might be Venetian or foreign nobles and dukes, ambassadors, or, on occasion, the patrons or owners of the opera theatres. In the case of a revival, where the librettist was deceased, any profits would have gone back to the impresario or the company at large.

The very earliest libretti came from the pen of the poet, composer, and theorbist Benedetto Ferrari (c. 1603–1681). In the third season came the librettist Orazio Persiani, a Florentine who had ties with Venetians dating back to the 1630s, with Le nozze di Teti e di Peleo, 1638/9, set by Cavalli at S. Cassiano. That same year saw Giulio Strozzi’s first libretto (La Delia, 1639, SS. Giovanni e Paolo, music by Manelli); he was also of Florentine heritage, but born in Venice and an active member of the Incogniti. Soon, members of the Venetian nobility and upper classes entered into the fray, chief among them (during the 1640s) Giovanni Francesco Busenello (1598–1659), Giacomo Badoaro (with two libretti), and Giovanni Faustini (1615–1651).

Busenello, also a member of the Incogniti, came from an old Venetian family of the cittadino (citizen) class, many of them high-ranking civil servants. An avid versifier, not just of libretti, but of poems, he practiced not as a secretary, however, but as a lawyer. Of his five libretti, only Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea (Venice, Teatro SS. Giovanni e Paolo, 1643) was set by a composer other than Cavalli. 16

The most prolific librettist of the 1640s came from an entirely different mould. Giovanni Faustini was the younger son of a Venetian cittadino. Though of the same rank as the family of Busenello, the Faustini clan could not claim the same prominence that the Busenellos enjoyed. As far as we know, Giovanni never took up a profession and lived with his brother Marco, a lawyer who encouraged his brother’s activities, and himself became an impresario upon the death of Giovanni.

Giovanni Faustini entered the arena as the fourth librettist at S. Cassiano (after Ferrari, Persiani, and Busenello), with La Virtù de’ strali d’Amore (1641/2), set by Cavalli, and the two continued to work together until the librettist’s premature death in 1651. Within a ten-year span, Giovanni wrote numerous libretti and drafted even more. In 1647 he left S. Cassiano to take up the smaller S. Moisé, which had presented opera only sporadically during the 1640s (with Faustini at S. Moisé, Cavalli’s Giasone, the opera presented at S. Cassiano during the 1648/9 season, was penned by Giacinto Andrea Cicognini, 1606–1649). Eventually the owner of S. Moisé (Almorò Zane) must have tired of the vicissitudes of the opera trade, and the third year of Faustini’s contract went unfulfilled when Zane hired a commedia dell’arte company. His passion for opera undeterred, Faustini soon took over S. Aponal, a theatre that, as we have seen, had been devoted to comedy in earlier years, but had for some indeterminate time served merely to store oil (on the ground floor). There Faustini instituted an ambitious plan in which he would mount two operas per season, each of them with a score by Cavalli – who at this time also supplied some operas for other theatres.

Count Nicolò Minato (c. 1620/5–1698) and Aurelio Aureli (fl. 1652–1708) were both lawyers who began to write libretti during the 1650s. Another member of the cittadino class, Matteo Noris (d. 1714), joined them during the 1660s. All three enjoyed remarkably long lives and continued to write libretti through the end of the seventeenth century, two of them into the eighteenth –although after 1669 Minato wrote his libretti for Vienna rather than for Venice, as imperial poet. Aureli remained in Venice and served a wide range of theatres and composers aside from several years spent at the Farnese court of Parma and a year spent in Vienna in 1659.

Noris’s last libretto was produced a year before his death in 1714. He wrote many works for the Grimani brothers, both at SS. Giovanni e Paolo and S. Giovanni Grisostomo, but he served other theatres as well, including S. Salvatore, S. Angelo, and S. Luca (formerly known as S. Salvatore); he also provided Prince Leopoldo de’ Medici with several libretti for his theatre at Pratolino, outside Florence. Especially vibrant was Noris’s collaboration with Carlo Francesco Pollarolo (c. 1653–1723), which persisted well into the eighteenth century. Many other librettists entered the fray, including the reformists Domenico David (d. 1698), Count Girolamo Frigimelica-Roberti (1653–1732), and Apostolo Zeno (1668–1750).

Venice’s Libretti

The earliest libretti set in Venice were based in mythology and ancient history, while making use of comic and lower-class characters added spice to the adventures and dilemmas of their ‘betters’. Giovanni Faustini took a different path, using newly invented characters. His libretti followed what has been called the ‘Faustini formula’, typically two couples at odds finally reunited by the end of the opera. Only in his last libretto, Calisto (Cavalli, S. Aponal, 28 November 1651), did he turn to a mythological plot with stunning results – even if the opera was a financial failure.

One magnificent interloper was Giacinto Andrea Cicognini, who arrived in Venice in 1646 and was soon drawn into the city’s intellectual elite.17 The son of the dramatist Jacopo Cicognini, he was the only librettist active in Venice with profound experience as a playwright. As his father before him, he drew on various Spanish sources in a number of his works, most of them unacknowledged. Giovanni Faustini, Minato, and Aureli would continue in this vein.18

Beginning in the 1653/4 season, Minato formed a close alliance with Cavalli, and, in the late 1660s, when Cavalli retired from Venetian opera, he served Antonio Sartorio (1630–1680). Minato’s Venetian libretti are historically based. Unusually, he set out his dramas in acts of twenty scenes each, something that became his trademark. Generally, he informs the reader of his sources and then sets out the complications that enter into the plot. Minato was known for the lively conversation between characters, his deft use of comedy, and his fine aria texts – which served Handel well when he reset Minato’s Xerse via Silvio Stampiglia’s adaptation for Giovanni Bononcini (Rome, Teatro di Tordinona, 1694).

Aureli’s subjects ranged farther than Minato’s. His Erismena of 1655/6 (Cavalli, Venice, S. Aponal) was fictional in the vein of Faustini’s libretti – and even borrowed from his L’Ormindo (Cavalli, Venice, Teatro S. Cassiano, 1644), but many of his works drew on either mythological or historical subjects, always perverting his sources and adding comic effects. At his most outrageous, Aureli turned opera’s time-honoured hero Orfeo into a jealous husband whose actions provoke the death of Euridice (L’Orfeo, Sartorio; S. Salvatore, December 1672).19 Librettists tended to complain about Venice’s audiences, who prized novelty. L’Orfeo shows Aureli willing to topple audiences’ expectations by serving up the unusual and, in this case, the unthinkable.

Composers

In some theatres a house composer might have a multi-year contract; in that case, the impresario’s task was lessened. Cavalli served as house composer in several theatres, though his loyalties shifted from time to time. In the 1650s he went from S. Cassiano to S. Aponal, then to SS. Giovanni e Paolo, and eventually back to S. Cassiano, now under the direction of Marco Faustini. When Cavalli left SS. Giovanni e Paolo for S. Cassiano, Giovanni Grimani hired Francesco Lucio (c. 1628–1658) and Giovanni Battista Volpe (Rovettino, c. 1620–1691), though not as house composers.

Pietro Andrea Ziani (1616–1684) began to write operas in the mid-1650s and changed theatres according to the activities of Marco Faustini. He served at S. Aponal, S. Cassiano, and SS. Giovanni e Paolo. Cavalli was the most well paid among the composers, much to Ziani’s regret. These two – as well as Giovanni Rovetta (c. 1596–1668), Volpe, Lucio, Sartorio, and Pollarolo – were all either Venetian or had worked there for many years. Others – such as the early composers Manelli, Ferrari, and Marco Marazzoli (c. 1602–1662) – came from other regions, as did Antonio Cesti (1623–1669) and Giovanni Antonio Boretti (c. 1638–1672).

As the decades passed, the music of many more ‘foreigners’ was welcomed onto Venetian stages. Nor did the composer need to be on-site at the time of the opera production. A number of Ziani’s operas were produced in those years he served in Bergamo and Vienna; no evidence yet suggests that Giovanni Domenico Freschi (1634–1710), maestro di cappella at the cathedral in Vicenza, was present when his operas were performed at S. Angelo. When on location in Venice, the composer would attend rehearsals, direct the orchestra, and make necessary additions and adjustments to the opera as required by any number of contingencies. Many composers were paid 150 ducats for their efforts, an amount that remained constant for many decades.

In Venice, as in other cities, opera was a lucrative ‘second job’ for composers: all of them had employment elsewhere, whether in churches or conservatories within Venice, or in any number of institutions outside of Venice, even at the imperial court of Vienna, or various duchies throughout Italy and the German lands. What is certain is that any composer who found himself in Venice would likely aspire to have an opera mounted there: the city eventually saw operas from the pens of Alessandro Scarlatti (1660–1725), German composers such as George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) and Johann David Heinichen (1683–1729), as well as ‘amateur’ composers such as Tomaso Albinoni (1671–1750/1) and Giovanni Maria Ruggieri (fl. c. 1690–1714).

Singers and Competition among the Theatres

Unlike opera in France and some Italian cities, a chorus did not figure into Venetian opera during the seventeenth century. Rather, operas might end with an ensemble featuring the main characters. ‘Extras’ did figure into the opera, but their role was to add grandeur to the stage in scenes where the ‘people’ were present, not to augment the musical forces. Nor did audiences hear ‘big’ orchestras such as that featured in Monteverdi’s Orfeo. Through the 1660s they heard an ensemble of strings (and an occasional brass instrument) accompanied by continuo instruments. Later in the century, winds and brass would routinely find their place in the orchestra.

Every opera needed a corps of singers, often from ten to twelve, so that over the years many singers passed through Venice. Some of them, whether Venetian or from elsewhere, sang both in Saint Mark’s Chapel and on the stage. Although several Venetian women (including Elena Passarelli, Margarita Pia, and, later, Vittoria Tarquini and Faustina Bordoni) sang in the theatres of their native city, most female roles were filled by women from Rome, Bologna, and elsewhere. In Venice, female roles were played by women, whereas in many other locales they would have been played by castrati.

Some singers, both male and female, had careers in Venice that lasted for more than a decade, while others sang there only rarely. As noted by Martinoni in the description that opened this chapter, singers were brought in not only from Italy, but from Germany and Austria (that is, Italian singers employed by various foreign courts). Indeed, impresarios in Venice sought the best they could afford, no matter where they might be found: by the end of the century, especially owing to the growing number of theatres, hundreds of singers had passed through Venice, had built up reputations, and were then available to sing elsewhere. One never knew when the next singer would arrive who would ignite the passions of both listeners and impresarios, as the Roman Anna Renzi had done earlier at the Teatro Novissimo in the 1640s.

The debut of the Roman Vincenza Giulia Masotti in the 1662/3 season was one of these occasions. It occurred at S. Salvatore, newly led by Vettor Grimani Calergi, when Masotti performed in Cesti’s Dori (Giovanni Filippo Apolloni, Innsbruck, Hof-Saales, 1657). Giuseppe Ghini, a member of the cast, wrote to his patron:

The opera is so praised that one can hardly remember a similar circumstance. The evening of the premiere they took in 913 tickets, a number which has never been seen in the entire time that opera has been done in Venice. The Roman girl … receives such applause that they hardly let her finish, for all the shouting. Each night so many sonnets in praise of her fly through the air that they impede the view of the spectators.20

This account emphasises the singing, pure and simple, of a new singer who would change the dynamics of impresarial dealings for years to come, for Masotti was the singer impresarios lusted over. One of Marco Faustini’s colleagues declared that the efforts to hire her in the mid-1660s had driven him mad.21 Masotti sang at S. Salvatore during Grimani Calergi’s years there, and then at SS. Giovanni e Paolo after the death of Giovanni Grimani. Masotti’s ascendance, perforce, upset the status quo at the two opera theatres in Venice: Caterina Porri, prima donna at SS. Giovanni e Paolo since 1653, would find her way to S. Salvatore. Faustini, in his prolonged and fruitless efforts to hire Masotti for SS. Giovanni e Paolo for the 1665/6 season, would have to ‘make do’ without either Porri or Masotti: in the last weeks before the opening of the season, he was forced to settle on women with lesser reputations.22

The Visual Element: Scenery, Costumes, Dancers, and Extras

Spectacle on the Venetian Stage

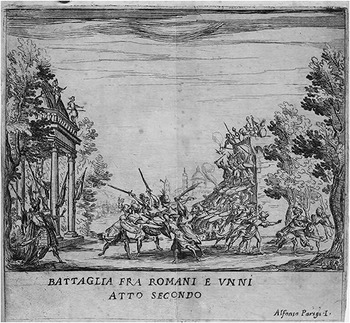

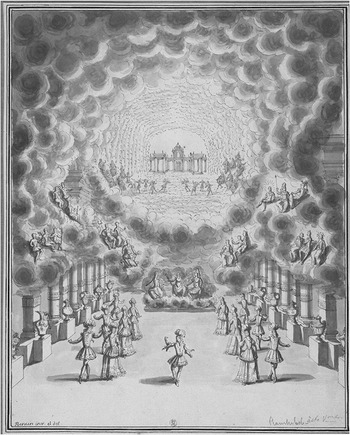

The opera ‘experience’ provided much more than instrumental and vocal music. The visual element was paramount, and it was this aspect that, in part, separated opera from the commedia dell’arte. Working with the scenographer and the costumer, the impresario brought to fruition the librettist’s conception. At least during the years of Marco Faustini’s management, scenery was made new each year, the specific scenes drawn from the various possibilities of exterior and interior views: campgrounds, gardens, city views, sea views, prison scenes, music rooms, and so on.23 This aspect could be rather costly; thus when Venetian operas, such as La finta pazza travelled to other cities, the spectacular elements might well be pared down.

Matteo Noris was remarkable in his ability to conjure up apposite scenes, such as those that presented the varied populace of a locale, including rulers, subjects, and dissidents, and the incorporation of various machines aimed to leave audience members in a state of marvel. Naturally other librettists also suggested such scenes according to the desires of the impresario and theatre owners. With the conception of any opera, the librettist, along with the scenery designer and the costumer, would chose those visual elements they felt best suited their drama, but economics would have played a significant role in the case of the scenery and the ‘extras’ that increased the grandeur seen on stage.

The Grimani theatres were especially known for their desire to include such pomp: for Giovanni Carlo and Vincenzo, the resultant splendour outweighed the costs necessary to realise these creations. An eyewitness account of a scene from Nicola Beregan’s Heraclio (music by Ziani, 1670/1) brings this spectacle to life:

As to the news, it appears in these days of carnival that the world at large revolves around the small world of the theater. No one talks of anything except the opera at S. Zuanepolo [SS. Giovanni e Paolo] … . There’s the first scene with the triumphal carriage drawn by big, life-sized elephants with a structure on it that reaches up to the level of the architrave. And on the structure at the first level there is the emperor Foca with numbers of actual warriors, soldiers, and pages, and on the neck of the elephant an imprisoned king in chains; this carriage is followed by two other large elephants with big turrets on their backs, also filled with armed cavaliers. The theater is surrounded by warriors; and the scenery is laid out so that until the end of the horizon of the perspective, one sees a vast army. And then one hears a great clamor of military sinfonie, trumpets, drums, pifari, cornetti, and artillery, all in music. The warriors, soldiers, pages, with a noble, yet distant military confusion, all sing, as if they were speaking in a hostile camp. All of this brings the greatest magnificence to the eye, and great satisfaction to the mind. The said elephants are so lifelike that one would say they are real; and it seems that this first set is not even one of the best compared to many of the others in this opera, a sign that the Signori Grimani can pride themselves for having spent lavishly … . They say in Venice that such spectacle has never before been seen in the theater … the attendance in the theater is such that not only Venice, but all of the cities of the terra ferma are emptied of the nobles, who run to see the opera.24

In December 1672, the singer Giuseppe Ghini, once again in Venice, wrote about a scene from Boretti’s Domitiano at SS. Giovanni e Paolo (libretto by Noris), mentioning ‘a most beautiful naumachia, a banquet scene with Domitiano as Jove that is incomparable, and the last scene … is esteemed as beautiful as is possible, so much so that they say at the Piazza: to S. Luca to hear, to SS. Giovanni e Paolo to see’.25

Dancers and Costumes

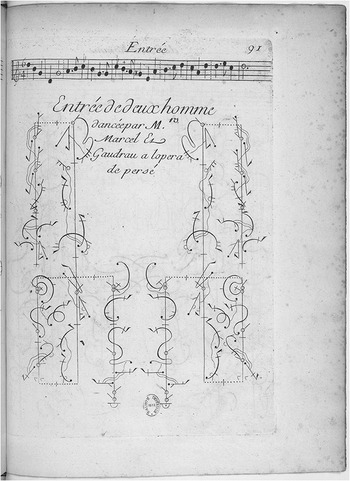

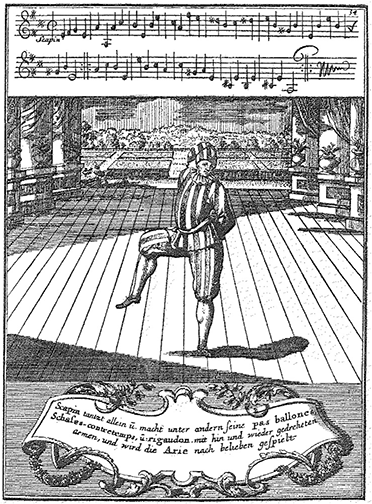

In the first opera at S. Cassiano, the company paid Balbi for several choreographies, and one of the pieces called for twelve dancers. Dances in Venetian opera tended to appear at the end of the first and second acts, rather than occurring more frequently, as would be the case in French opera. Marco Faustini tended to employ several different choreographers, presumably according to their availability (during this period the names of the individual dancers are unknown). In the earliest years of opera in Venice, Balbi was the outstanding dancer and choreographer. His travels to France and other cities in Italy necessitated the presence of other professionals such as Giovanni Battista Martini, Battista Artusi, Olivier Vigasio, and Agostino Ramaccini.26 Regarding costumers, impresarios relied on a number of them, some quite renowned in the field – such as Horatio Franchi at the Grimani theatre – but others little known aside from several pay records. These costumers were most involved with outfitting the major characters, as generic costumes could often be obtained through jobbers at a much lower cost.27

Venetian Opera and the Venetian Republic

Opera in Venice differed from that mounted in other duchies and kingdoms regarding who or what was being honoured or celebrated. If in France, it was designed to reflect the splendour of the Sun King, Louis XIV, and in various duchies that of the reigning duke; in Venice it could be said to celebrate the magnificence of the Most Serene Republic, whether overtly or not. Most likely, the doges would only have known opera in Venice from those years preceding their reign, when they were free to socialise in their families’ boxes: Venice’s power resided not in the doge – practically a prisoner in the Doge’s Palace – but in its governing bodies made up of nobles of ancient lineage, who filled most of the boxes.

If it could be said in the late 1630s that in Venice one could see such splendour as was normally seen in the palaces of kings, comparisons were no longer necessary as opera became firmly established. An overview of opera libretti published both in and outside of Venice is revealing. A libretto dedication served multiple functions, one of which was to enrich the purse of either the librettist or the opera company. But with one early exception (written by Benedetto Ferrari, a native of Reggio, in 1639, for L’Armida) no libretto was dedicated to a doge. Rather, most were dedicated either to visiting princes and dukes and their families, or to Venetian nobles. In both cases Venice’s reputation was enhanced: theatres were graced by the ‘patronage’ of important personages, and, moreover, dedications to nobles often pointed to the service of their families to the Republic. Just as a libretto such as Busenello’s L’incoronazione di Poppea might celebrate the superiority of the ‘republic’ over a corrupt emperor, so too could Venice’s opera industry serve to shine light on a republic which, despite a loss of power compared to the supremacy of earlier centuries, still emanated an aura of independence and wealth.28

‘Public’ Opera outside of Venice

Opera began at Italy’s courts, and private entertainments of various stripes would continue throughout the century. The Barberini family’s dedication to opera started during the reign of Urban VIII in the 1620s and continued after the pope’s death29. Other families (such as the Colonna and the Chigi) and institutions such as embassies would continue the practice, given that public opera was generally discouraged in Rome. Gradually theatres offered up opera in other cities and towns. Often they were ‘sponsored’ by a local ruler, who might supply some, but not necessarily all of the funds. In Florence, several theatres operated under the sponsorship of academies, whereby the costs were borne by their members, but various Medici princes were active in their support of them.30 In times of civic celebration, such as during the marriage of the future Grand Duke Cosimo III to Margherita Luisa d’Orléans in 1661, the celebratory opera was Ercole in Tebe by Giovanni Andrea Moniglia (1624–1700) and Jacopo Melani (1623–1676). Also presented that year was the Venetian Erismena by Aureli and Cavalli. Then, in turn, Moniglia’s libretto travelled to Venice ten years later for the 1670/1 season, revised by Aureli in order to please Venetian audiences, and newly set by Boretti.31 Whether travelling from or to Venice, both the libretto and the score were malleable, adapted to the occasion and the strengths of the performers.32

The establishment and growth of the opera industry in Venice either directly or indirectly led to an expansion of the entertainment. As more and more singers were recruited to sing there, they would have been available for hire in other locales during other seasons; as these singers’ popularity waned, they could be hired to sing during the carnival season outside of Venice. In some cases the spread of certain operas seems to have been promoted by singers. Aureli and Ziani’s Le fortune di Rodope e Damira (Venice, S. Aponal, 1657) circulated widely throughout Italy until the last known performance in Reggio in 1674. In a number of the early performances (Bologna, Milan, Bergamo, and Turin), though not in the original, the role of Rodope was performed by Anna Felicita Chiusi (c. 1635–1664), who also signed the libretto dedication in Milan in 1660 (as well as the dedication for Aureli and Volpe’s Costanza di Rosmonda in Milan the next year). Yet Chiusi was one of the prima donnas in the opera performed the previous year in Venice at S. Aponal, Erismena, by Aureli and Cavalli. Given that Erismena was also performed in Milan around the same time (1661), it is likely that she performed in it as well.

Chiusi is one example of a new breed of female singers who would help to mount opera in cities across Italy – as she was living in Venice at the time of her death (1664), she would have maintained numerous contacts with the musicians of that city. The Roman Anna Francesca Costa (fl. 1640–1654), under the protection of Cardinal Giovanni Carlo de’ Medici, brought Moniglia’s Ergirodo (composer unknown) to Bologna in 1652.33 Another was Elena Passarelli, a Venetian who had performed at S. Cassiano in the 1650s. Having already appeared in Siena in Cesti’s Argia in 1669 to great popularity, she signed a dedication for a performance of the same composer’s Dori in Florence in 1670. She had been prepared to have Dori mounted in Siena, where she would have served as ‘impresaria’, but the performance had to be cancelled, and she took it ‘elsewhere’.34 Much of the history of these travelling productions remains to be written.

Public opera, or rather opera that was in part commercial and in part subsidised, spread to many cities and towns throughout Italy. In the seventeenth century, Bologna had two theatres, the Formagliari and the Malvezzi: both presented operas previously performed in Venice, along with others.35 Opera in Milan flourished at the Teatro Ducale, with a mix of Venetian revivals and works by local composers and librettists, including Carlo Maria Maggi (1630–1699). The types of operas presented throughout Italy, and the interactions between theatre and city, changed from town to town. The next section looks briefly at two examples, Siena and Naples.

Siena

As recently shown by Colleen Reardon, the nature of operatic production in a particular locale could change over time. In Siena – a city with a rich theatrical tradition – it went from being a product of the patronage of a reigning government (as represented by Prince Mattias de’ Medici) to an entertainment in part sponsored by an important local family (the Chigi), and then to a more typical impresarial and commercial model.36

Datira, a work by Pietro Salvetti and the Medicean singer Michele Grasseschi, was sponsored by Mattias at enormous cost in a theatre renovated by him; the opera was performed in 1647. This type of enterprise was not to be repeated: the more permanent establishment of opera in Siena came about later and arose through a more organic and more local motivation.

Not until 1669 was another opera presented there. Cesti’s Argia (Giovanni Filippo Apolloni, Innsbruck, 1655), was mounted in a theatre restored with the help of funds from the Roman Chigi, as well as many other Sienese families. Related to Pope Alexander VII who reigned 1655–1667, this branch of the Chigi (principally Cardinal Flavio Chigi and the younger Cardinal Sigismondo) were noted sponsors of music both in Rome and at their villa at Arriccia, just outside the Holy City. Although they helped to choose the opera, the whole production was very much a communal effort, with financial support coming from many of the city’s noble families. Argia’s prima donna was Passarelli, whose enthusiastic reception, replete with generous gifts, must have encouraged her to return to Siena the next year.37

Perhaps the pinnacle of opera production in Siena occurred in 1672, when three works were presented to celebrate the visit of Princess Maria Virginia Borghese Chigi. They were Cesti’s Dori, the same composer’s Tito (Nicola Beregan, SS. Giovanni e Paolo, 1666), and Melani’s Girello (Filippo Acciaiuoli, Rome, Palazzo Colonna, 1668), all of them connected in some way with Rome and some with the Contestabile Lorenzo Onofrio Colonna, a frequent ally of the Chigi regarding issues of musical patronage. The whole enterprise was pulled together by the librettist and impresario (at the Roman theatre the Tordinona) Filippo Acciaiuoli (1637–1700), in Siena for the duration of the productions.

The next decade brought a number of operas, most of them pastoral in nature and often mounted in connection with Chigi visits to Siena. One of them, Bernardo Pasquini's La sincerità con la sincerità, overo Il Tirinto (1673), had previously been mounted at the Chigi villa in Ariccia at great expense. The production of these Sienese operas was always facilitated through the assistance and support of a number of local academies, and, in the case of Il Tirinto, by the ad hoc ‘L’Accademia del Tirinto’, who signed the dedication of the libretto to Virginia and Olimpia Chigi, two of the nieces of Pope Alexander who had remained in Siena.

By the end of the century, Chigi involvement lessened and that of one of the Sienese academies, the ‘Rozzi’, increased, beginning with a revival of Scarlatti’s L’honestà negli amori (Rome, 1680) in 1690. Then in 1695 came the noted playwright and historian Girolamo Gigli, born in Siena in 1660. As impresario, he would guide Sienese opera into the next century.38

Seventeenth-century Siena embraced opera, supremely conscious of how it operated within what Reardon has called the city’s ‘sociable’ network, which would fade after Gigli’s time, when opera would become a more occasional entertainment with less involvement by the Sienese populace and more reliance on travelling companies.

Naples

Opera in Spanish-ruled Naples often took place at the pleasure of the Viceroy of Naples, a Spanish representative of the King of Spain. As in Milan, also under Spanish rule, the same entertainments were frequently presented in two venues, first at the royal palace and then in the public theatre, the most prominent of them S. Bartolomeo. One important way in which opera production in Naples (and Milan) differed from that in the rest of Italy was the result of a Spanish law dating from 1583, by which a percentage of the box income went to a charitable institution: in the case of Naples, the Ospedale degli Incurabili (which had, in 1621, played a part in the building of the theatre). Moreover, no tickets could be sold to public performances without the permission of that institution.39 In this way, Neapolitan opera could not have been more different from that of Venice.

Lorenzo Bianconi and Thomas Walker examined the early history of public opera in Naples and explored how opera flourished under the auspices of Count Oñate, who, rather than relying purely on local artists, made use of a travelling company of musicians, the Febiarmonici. A number of operas performed there came by way of Venice, including La finta pazza, L’incoronazione di Poppea, and Cavalli’s La Veremonda (often, in the 1650s, through the direct intervention of the dancer and choreographer Balbi).40 But viceroys came and went (eleven of them during the second half of the seventeenth century), and the fortunes of opera in Naples were in large part dependent on the interest of the viceroy. The repertory mixed the music of local talents such as Francesco Provenzale (c. 1626; d. Naples, 6 September 1704) with Venetian scores such as those by Cavalli. In the 1670s, S. Bartolomeo largely specialised in operas from Venice by Ziani, Cesti, Boretti, and Carlo Pallavicino (c. 1640–1688). This theatre enjoyed some notoriety as a result of its impresaria, the former prostitute Giulia De Caro, who had first appeared there as a singer. Here was another difference from Venice, where singers were not impresarios, nor were women.

As Louise K. Stein has shown, during the last quarter of the seventeenth century the patronage and support for opera at the palace and at S. Bartolomeo emanated in large part from the coffers of the viceroy himself, and some of the funds came from the Spanish government.41 The financing behind Neapolitan opera, then, was inevitably a mix of private and public support, with the management of the ‘public’ theatre undertaken by an independent impresario.

Some viceroys arrived in Naples with little knowledge of Italian opera, and their support varied widely. However, Gaspar de Haro y Guzmán, Marquis del Carpio (1629–1687), had been an important patron of drama in Spain and had seen opera in Venice. He came to Naples from his ambassadorship in Rome, where he had come to know the music of the young Scarlatti. Carpio placed his stamp on opera in Naples, and he saw personally to many aspects of the operas mounted during his tenure; he also helped to bring Scarlatti to Naples, where his fame and importance would grow. A link between Carpio’s activities as a patron in Spain and then in Naples lies in three of the operas presented there, based on the same Spanish plays by Pedro Calderón de la Barca that he had had produced in Spain and then in Rome. Nine years after Carpio’s residence in Naples came Luis Francisco de la Cerda y Aragón, Duke of Medinaceli, who also had previously been the Spanish ambassador in Rome and was able to use contacts from the Holy City, Venice, and Florence in order to recruit top musicians to Naples. As in the case of Carpio, Medinaceli’s patronage of Scarlatti was particularly significant for the history of opera there.42

A Night at the Opera

In Venice as elsewhere in Italy, months of preparation culminated in the première and subsequent performances of an opera. In the end, the audience dictated the success or failure of a production. Was the music pleasing? Did the singers live up to their reputations? Would hisses and boos force the librettist and composer back to their desks, or would the management decide, after nights of cheering audiences, to add new arias to delight the listeners? Anything was possible. In Venice there were those operas that closed after one night, and others whose success defied the odds. Some listeners would even move from theatre to theatre in one night to catch their favourite singer or aria. Indeed, the diversity of the city’s offerings not only made such nocturnal wanderings possible but also added to the richness of the carnival season, to the sense of competition, and to questions of which theatre would mount the best show, whatever that might mean. The experience differed in other cities, where, generally, only one opera could be seen at any one time. Yet the spread of public opera – however that might be defined – in all its myriad manifestations meant that, all across and down the Italian peninsula, this expensive and multi-layered entertainment could be enjoyed. Listeners could experience astonishment and wonder, or they could just enjoy a night out with friends and watch the others who made up the audience. And, despite the passage of more than three hundred years, little has changed.

The birth of opera around 1600 is intimately tied to singers. Jacopo Peri and Giulio Caccini are known not only as composers of the first complete published operas but also as superb vocalists. In October 1600, as part of the Florentine celebrations for the wedding of Maria de’ Medici to Henry IV of France, Peri starred as Orfeo in his own setting of Ottavio Rinuccini’s Euridice.1 On stage with him were Caccini’s daughters, Francesca (1587–after 1641) and Settimia (1591–c. 1660), who, instead of performing Peri’s music, sang the settings their father had insisted upon inserting. In future years, Francesca would go on to be celebrated for both her vocal prowess and her compositional acumen: she was the first woman to compose an opera, La liberazione di Ruggiero dall’Isola di Alcina (1625).2 The spread of opera thus cannot be separated from the talented performers who brought the works to light on the stages of courts and public theatres over the course of the century.

That said, Sergio Durante has noted that the career of opera singer was ‘a professional role that really came into being only gradually’.3 Such a change could happen only after opera had vaulted to the public stage in Venice in the late 1630s and after cities all over Italy began to mount such works on a regular basis throughout the year (and not just in carnival season). The careers of Peri and Caccini played out before this sea change. They were both initially employed at the Medici court in Florence for their skill as singers and instrumentalists, but their duties also comprised the composition of many different kinds of works, including instrumental pieces, songs, and court entertainments. After 1600, Peri worked mostly as a composer, collaborating with Marco da Gagliano (1582–1643) on both operas and sacre rappresentazioni. Caccini was a sought-after voice teacher – he had a hand in training both of his daughters – and later in life he dedicated himself to gardening. Singing in opera was but one small facet of their storied careers.

It was only in the last decades of the seventeenth century that it was possible for a singer to devote a career to opera; some well-known vocal stars, however, chose not to do so. The castrato Matteo Sassani (or Sassano, c. 1667–1737), for example, began and ended his professional life singing in serenatas and religious services; he mounted the operatic stage for about ten years of his long career, more rarely than other great singers of the time.4 Pier Francesco Tosi (1654–1732), who sang perhaps once on the operatic stage in the 1680s and who went on to write a highly regarded treatise on the voice, noted that all singers should be able to sing recitative in three styles: one for church, one for chamber, and one for opera.5 Even in the late seventeenth century, then, singing opera was sometimes just one part of a larger professional life that arose out of a confluence of talent, training, and patronage.

Training

The institutions that offered musical instruction were already well established in Italy by the time opera rose to importance and included churches, conservatories, and seminaries (especially the national colleges in Rome).6 Boys entered or were recruited to those organisations at very young ages and learned their foundational skills there. Pedagogical programs doubtless taught them the techniques that are the basis of any vocal training, even today: how to produce a healthy tone, how to sing in tune, how to develop vocal flexibility, how to enunciate clearly, and how to avoid grimacing. Since the ability to decorate a vocal line was so important in the seventeenth century, students needed to practice how to apply and sing various ornaments, such as trills.7 Boys also received instruction on the keyboard and learned basic theory and counterpoint as well.

The need for male sopranos in church choirs was so great that the administrators at some cathedrals began to recommend talented young boys with beautiful voices as candidates for castration and either to pay directly for the procedure or to reimburse parents who had already had it done. The attraction of the operatic stage was so powerful that churches issued contracts specifying a standard length of service before the boy could leave the choir and seek his fortune as an opera singer. In Siena, for example, boys had to serve the cathedral choir for six years before they could leave the employ of the institution; otherwise, they had to repay half of the cost of the operation and half of the salary they had earned.8 As long as the boys remained on the payroll most of the year, however, the administrators at Siena Cathedral did allow them to take short leaves of absence to sing on the stage; in this, they were much less severe than their peers at San Francesco in Assisi, whose rules forbade castrati to perform in opera until the tenth year of their service.9

Talented girls in Italy could not avail themselves of this kind of comprehensive, institutional education unless they were placed in convents with active and lively traditions for musical performance. Nuns were some of the most highly regarded singers on the Italian peninsula during the seventeenth century, and some sang theatrical works in the convent.10 In 1670, for example, the Grand Duchess of Florence consigned to a Sienese nunnery a young girl ‘highly predisposed’ to music, perhaps in the hope that she would blossom into an excellent performer.11 The Duke of Savoy adopted a similar strategy in 1688 when he sent the singer Diana Aureli (fl. 1691–1696) to a Milanese convent to perfect her vocal technique.12 Since the majority of convents in Italian urban centres during this period were, however, intended for ‘surplus’ women of aristocratic birth whose status would not permit them to sing on stage, not many professional opera singers came out of this environment.

Most girls had to receive their training privately, and, in this, some were more fortunate than others. The Caccini sisters, for example, were raised in a musical household (both Giulio and his wife Lucia di Filippo Gagnolanti were singers) and probably began their musical apprenticeship at a very young age. Other parents made different decisions. Silvia Galiarti (c. 1629–c. 1677), whose mother was a talented opera singer unattached to a court, entrusted her daughter’s musical education to a private tutor, whose seduction of the young woman sparked a legal case.13 The gifted Caterina Martinelli (1589 or 1590–1608), on the other hand, found a good home away from home. She came to Mantua from Rome as a thirteen-year-old and boarded with Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643), who took on the responsibility of teaching her and subsequently wrote the title role in Arianna for her.14 Her unfortunate death from smallpox at the age of eighteen forced the composer to look elsewhere, and he turned to a woman best described as an actress with an excellent voice, Virginia Ramponi Andreini (1583–1629 or 1630). The trend of using actress-singers in opera did not, however, persist into the mid- to late-seventeenth century, as the musical skills required became more specialised.

The case of Lucrezia d’Andrè (fl. 1694–1704) is illustrative in this regard. In 1694, the Roman noblewoman Lucrezia Colonna Conti wrote to Cardinal Francesco Maria de’ Medici in Florence, seeking to induce him to hire d’Andrè for an opera. Her letter briefly describes the background and character of the young woman (she was the daughter of one of Colonna Conti’s servants and was modest and hard working) but is most effusive as to her musical training. The young woman had learned her vocal technique from Giuseppe Fede (1639 or 1640–1700), an accomplished castrato singer in the papal choir, a veteran of operatic performances, and an admired teacher. She had studied harpsichord with Bernardo Pasquini (1637–1710), a keyboard virtuoso and a renowned composer of oratorio and opera. Colonna Conti also notes that another famous opera composer, Giovanni Bononcini (1670–1747), and a singer under the protection of the Medici, Giuseppe Canavese (fl. 1684–1707), had heard her perform, undoubtedly at the Colonna household. By the late seventeenth century, it appears that (with some exceptions) a high level of musical training, as well as a good stage presence, was necessary to be able to sustain a career on the operatic stage.15

Beyond her training, a woman who wanted to perform in opera could unleash another weapon in her arsenal, if she possessed it: the ‘lovely letter of recommendation’ in her face.16 John Rosselli quotes a 1663 document concerning the requirements for female singers at the Venetian theatre of SS. Giovanni e Paolo: ‘beauty’ and ‘rich clothes’ were the first items on the list and only then was ‘attractive singing’ mentioned.17 In her plea to Francesco Maria, Colonna Conti made sure that the cardinal knew of d’Andrè’s physical charms in addition to her good character and first-rate musical education. When the Bolognese singer Angela Cocchi (‘la Linarola’, d. 1703) arrived in Parma in late 1697 to perform a role in L’Atalanta, the castrato Giovanni Battista Tamburini (1669–after 1719) observed that if her voice were equal to her beauty, she would be marvellous.18 That said, beauty went only so far. A Sienese correspondent once described Vincenza Giulia Masotti (c. 1651–1701) as an extremely ugly woman (‘una gran brutta figliola’), but audiences went into raptures during her performances, and she was one of the most highly regarded singers of her time.19

Many singers made their débuts on the operatic stage at a relatively young age: Masotti first appeared in Venice when she was probably eleven or twelve years old, and Vittoria Tarquini (‘la Bombace’, 1670–1746) made her première at age fourteen.20 The alto castrato Francesco Bernardi (1686–1758), the singer for whom Handel would write some of his most celebrated works, was thirteen when he first mounted the stage in his native Siena. Girolamo Gigli, the impresario for the production, was probably responsible for adding the part tailored just for him in the libretto, and the local chapel master, Giuseppe Fabbrini, doubtless set those new additions with music suited to his young voice. Bernardi then continued his instruction at Siena Cathedral under Fabbrini for another eight years before going off to seek his fame and fortune.21 Anna Renzi (c. 1620–after 1661), on the other hand, was probably near twenty when she first sang in opera; nonetheless, her voice teacher, Filiberto Laurenzi, accompanied her to Venice for her début.22 Voice lessons thus could continue after singers were launched in opera, especially if they were young; at times, however, such training could extend into adulthood.

Tamburini provides an interesting example of a singer whose schooling we can follow for many years. He was one of the numerous boys for whom the religious authorities at Siena Cathedral paid the expenses of castration and provided a foundational education in music. His tenure at the institution lasted from 1683 to 1695, that is, from the age of fourteen to the age of twenty-six. He came under Cardinal Francesco Maria de’ Medici’s protection sometime in his early twenties and mounted the stage in minor roles for productions in Florence and Siena from 1690 to 1695. Then the cardinal packed him off, first to Rome and then to Parma, to study under the composer Bernardo Sabadini (d. 1718). Tamburini sang in several operas during this further period of study. When Sabadini left for Madrid in 1700, Francesco Maria sent his protégé to the composer Carlo Antonio Benati in Bologna, despite the fact that Tamburini was nearly thirty-one years old and had already performed in sixteen operas. It is true that the lessons in Parma probably consisted primarily of Sabadini coaching the singer on the music he had written especially for him and perhaps also refining his acting skills. Tamburini did, however, tell his patron that ‘sometimes my teacher will have me sing scales to make sure my technique is secure’. Although we have some insight into singers’ basic training during the seventeenth century, we still know little about how they continued to perfect their craft once they were established on the operatic circuit.23

One additional category of singer deserves mention here: the talented dilettante. In small cities with strong academic traditions, noblemen sometimes took the stage for local performances. In Siena, for instance, we know of at least two productions featuring a mix of professional and amateur performers: L’Adalinda (Apolloni, Agostini, 1677) and L’innocenza riconosciuta (1698). In the latter opera, three members of the Sienese patrician class mounted the stage alongside Pietro Mozzi (fl. 1686–1729) and his son, the young castrato Giuseppe Mozzi. One of them, Tolomei, perhaps less skilled than the others, lost his voice during the last act of the second performance and accused the elder Mozzi of instructing the instrumentalists to play so loudly as to drown him out.24 Such were the perils of the lack of professional training.

Patronage

Opera singers depended on powerful patrons for protection. Italian rulers in numerous urban centres hired and maintained salaried singers to use in operas performed under their aegis. The ecclesiastical courts in Rome also patronised singers. But if Peri’s Euridice was mounted in Florence using singers on the Medici payroll, the performance of Monteverdi’s Orfeo only seven years later depended on the talents of at least one performer who was not part of the musical establishment at Mantua. The Florentine court loaned one of Caccini’s pupils, the castrato Giovanni Gualberto Magli (d. 1625), to the Mantuan court for the opera; he sang at least two and probably three roles in Orfeo.25 When public operas began to be staged in Venice starting in the late 1630s, it was paramount that singers be able to move from one city to another to take advantage of the opportunities to sing. This was especially true for female singers in Rome, who were forbidden from taking the stage in that city.

Several solutions to the problem presented themselves. In the first half of the seventeenth century, self-financing touring companies, sometimes called Febiarmonici, travelled from city to city to put on operatic performances. Ellen Rosand has noted that such troupes (often with Roman singers) were responsible for the first operatic performances in Venice; after carnival season, they then took their shows on the road.26 By the 1680s or so, when opera was well established as a feature of cultural life all over the Italian peninsula, performers were the star attractions. Impresarios wanted to hire the best, and a number of rulers with singers under their protection often responded to requests to send them to perform elsewhere. Thus was the ducal or gentlemen’s circuit born – with the enthusiastic participation of courts in Florence, Mantua, Ferrara, Parma, and Rome (to name but a few), whose rulers loaned out musicians to one another as well as to impresarios in the public theatres of Venice. The system benefitted everyone. Rulers who loaned out one of ‘their’ coveted singers symbolised their social rank through a display of ‘good taste and knowledge’, thus earning honour for themselves as well as the more prosaic right to borrow a singer from another member on the circuit for their own productions. The singer had the protection of the ruler as a guarantee against ill treatment, an opportunity to perform in a new setting with new colleagues, and the chance to earn more than he or she ever could as a court employee.27

Some patrons kept a tight rein on their protégés. Rosand describes how Pietro Dolfin, a librettist and composer in Venice, exercised his power over the singer Lucretia, a young woman who came to live in his house in the late 1660s. Dolfin controlled all the young woman’s contracts, refusing to allow her to sing when he thought the part too small or the cast mediocre.28 Francesco Maria de’ Medici did the same with Tamburini, arranging for his début in Florence in 1690, informing him (through a proxy) that he was to turn down a role in a ‘dreadful, feeble work’ in Rome in 1697, and instructing Sabadini on the operatic environment in which his protégé was likely to shine: as the singer of a secondary role (parte di mezzo) in an opera with a cast of excellent singers.29

Tamburini’s situation was not unlike that of many singers in the later seventeenth century. Francesco Maria paid Sabadini for his role as Tamburini’s teacher and for the expenses of housing and feeding the singer in Parma; he also gave his protégé a modest yearly annuity until about 1705. Tamburini was, however, never resident in Florence as a court employee; instead, he spent his life on the road.30 The same was true for other singers of the time, such as the contralto Francesca Vanini (or Venini; d. 1744), Maria Maddalena Musi (‘la Mignatta’, 1669–1751), and Barbara Riccioni (fl. 1684–1707), who received small stipends as court musicians in Mantua but spent most of their time travelling the Italian peninsula to perform in opera.31 Although some dukes and princes served as agents, many functioned simply as clearinghouses for their singers. It is thus ironic that during the last years of the century, libretti start to emblazon the names of not only the singers in operatic productions but also those of their patrons: ‘Elena Garofalini, Bolognese, virtuosa of the Most Serene Duke of Mantua’, ‘Diana Caterina Luppi of Ferrara, virtuosa of Count Ercole Estense Mosti’, and ‘Signora Diamante Scarabelli, virtuosa del Sereniss. Di Mantova’ (see Figure 6.1), and so on.

The Rise of the Prima Donna

At opera’s birth, Rosand notes, singers were ‘merely the mouthpiece[s] of the librettist and composer’.32 That began to change by mid-century, with the woman who has been called the first prima donna of opera, Anna Renzi. Renzi came from Rome to Venice to create the role of Deidamia in the Giulio Strozzi/Francesco Sacrati opera La finta pazza (1641). Later, she would première the role of Ottavia in Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea (1643). A book was issued in her honour in 1644, praising her voice, her acting, and her ability to embody a character through gesture and spontaneity of expression. Her fame and popularity meant that during the 1643–1644 season, she was able to command a far higher salary than any other woman who had sung on the Venetian stage up until that point.33

The control singers had over the very fabric of opera began to be audible by the 1660s and into the following decades with the proliferation of arias.34 By this time, singers could request that the composer make changes and additions to their parts, and were able to reject arias they did not like and substitute them with works of their choosing – even if not by the composer of the opera – that they felt showed off their voices to greater advantage. The practice of performers repeating arias on stage when an enthusiastic audience demanded it also became a commonplace.

As singers’ fame and influence grew, so did their power to negotiate all manner of things relating to the production. Masotti offers a good case study of a singer who knew her worth and knew how to work the patronage system to her best advantage.35 She was obviously a talented young woman; in Rome, Margherita Branciforte, Princess of Butera, had taken her under her wing and Masotti had received her musical training in the princess’s home from Giacomo Carissimi (1605–1674), one of Rome’s most celebrated composers and maestro di cappella at S. Apollinare. A Tuscan resident in Rome, Torquato Montauto, became her protector and probably helped arrange her début in Venice at the Teatro San Luca for the 1662–1663 season. Despite the fact that Giulia was no older than twelve, she made a huge splash in the title role of La Dori, an opera with a libretto by Giovanni Filippo Apolloni (c. 1635–1688) and music by Antonio Cesti (1623–1669). She reluctantly returned in 1663–1664 to perform in two operas, one of them Francesco Cavalli’s Scipione affricano. Around this time, she gained new patrons: the Contestabile Lorenzo Onofrio Colonna and his wife, Maria Mancini.

Masotti refused to go back to Venice in the 1664–1665 and 1665–1666 seasons, but the impresario Marco Faustini (1606–1676) insistently requested her presence for 1666–1667. Using the Contestabile Colonna and the Venetian nobleman Girolamo Loredan as intermediaries, Masotti dug in her heels and once again refused to go until promised a salary that was twice as much as she had been offered (and had turned down) in 1665. She also received travelling expenses and was given lodging with the Grimani family. She was similarly shrewd in her negotiations for the 1668–1669 opera season in Venice, using both the Colonna and her new patrons, members of the Chigi family, to guarantee herself a large salary and other concessions. She must have been gratified that the opera chosen that season was a revival of L’Argia, a work by her preferred librettist, Apolloni, with music by her favourite composer, Cesti. In 1671, in fact, she tried to persuade Cardinal Sigismondo Chigi to ask Apolloni for a new libretto with a ‘part that does me honor above everyone else’. This was one of her few requests that came to nothing. Throughout her career, she managed to convince impresarios to mount operas that she liked and to cast her in the roles she wanted to sing. In other words, although she depended upon patrons to protect and help her, she was in charge of her own professional life.

Other singers sometimes took hold of the reins in an even more authoritative manner. Elena Passarelli (‘la Tiepola’, fl. 1658–1673) was not only a well-respected singer, but also cast herself at least once in the role of impresario, perhaps in tandem with her husband, Galeazzo. In 1670, she signed the libretto issued for a Florentine revival of Cesti’s La Dori, dedicating the work to Margherita Luisa d’Orléans, the Grand Princess of Tuscany, whose marriage to Cosimo III was then in a final period of reconciliation. Passarelli and her company mounted the opera in Florence and then were scheduled to go on to Siena, where the singer had performed the previous year in a revival of L’Argia. She astutely supposed that an opera by the same librettist–composer team that had triumphed in Siena a year previously with her in the lead role would be sure to please the Sienese, who were indeed waiting with impatience for the performances. Unfortunately, the show was cancelled due to the death of Grand Duke Ferdinando II in 1670. A correspondent in Siena observed that Passarelli was responsible for the company and since the show could not be staged there, she would pay the salaries and take the cast on to the next performance.36 In 1704, in Siena, the singers Maria Anna Garberini Benti (‘la Romanina’, c. 1684–1734) and Vittoria Costa (fl. 1701–1719), aided by the Florentine chapel master Giuseppe Maria Orlandini (1676–1760), decided to serve as impresarios for a little pastoral opera, taking the lead roles, establishing the ticket prices, and hoping to make a profit from the enterprise.37 Their plans may not have come to fruition, but they show that more than one female singer was unafraid to venture into new realms to direct her own career.38

Payment and the Gift Culture

The first singers of opera performed those works as part of their normal court duties. That changed once an operatic circuit was established and it was necessary for singers (or their agents) to negotiate salaries. As is clear from the discussion of Masotti above, singers who had to journey to foreign cities also often asked for travelling expenses and requested free lodging with the impresario or with a nobleman; otherwise, they might not have taken much money home after a long season. No one formula determined how much a singer could make, and salaries varied according to the locale and the size or importance of the role, as well as the reputation of the singer. Women were the most coveted performers during this period and generally earned higher salaries than men, an imbalance that would change in the eighteenth century when the castrato rose to great prominence. One thing appears to be true for opera productions throughout the Italian peninsula in the late seventeenth century: the costliest items on the budget were the salaries paid to the singers.39

Although private agreements between an impresario and a singer were by far the most common throughout Italy, a few publicly registered contracts for singers in Venice survive and help clarify some of the details of payment and the expectations placed on singers and impresarios. A contract for Renzi from the 1643–1644 season, for example, establishes a payment schedule, which seems to have been the normal one for that city: the singer was to receive the honorarium divided into three portions and distributed at the beginning, middle, and end of the opera’s run. If she were to fall ill, she would collect only a portion of her salary. She also received the use of a box in the theatre at the expense of the impresario and all the costumes she would need (although these remained with the impresario at the end of the run). In return, she agreed to attend all rehearsals and performances.40 What may be the first printed contract for singers, issued in Siena in 1703, lays out basically the same expectations, although it specifically excludes payments for travel and food.41 Even with a contract in place, if a show did not succeed as planned, singers might receive only a portion of the contracted fee and have to lodge complaints or initiate legal cases to collect what was owed them.42

Payment in cash was, however, only one form of remuneration that performers acquired during the run of an opera. Both men and women (but especially women) expected to receive gifts, including rings; bracelets; necklaces; watches; earrings made of gold and silver and often encrusted with precious jewels; and items of clothing comprising hats, gloves, ribbons, and stockings. The cash portion of the payment to a singer, especially a beautiful female singer, sometimes paled in comparison to the presents she received from admirers. When Passarelli performed the title role in the Sienese revival of L’Argia (1669), the women of the town ordered culinary delicacies from Florence for her on a continual basis, and over thirty gentlemen contributed money to buy her a gift worth 700 lire. She left town at the end of the opera’s run with 2,800 lire in cash and gifts, probably more than she had earned in Venice in the early 1660s. From accounts of the revival of Bononcini’s setting of Silvio Stampiglia’s Camilla, regina de’ Volsci in Siena in 1700, we know that the star performer, Maria Domenica Pini (‘la Tilla’, 1670 or 1671–1746), carried away about 1,400 lire in cash and almost 600 lire in gifts. Her colleague, Maria Maddalena Vittori (‘la Marsoppina’, fl. 1699–1704), went home with about 400 lire in cash and perhaps as much as 600 lire in gifts.43

Critical Assessment

It is difficult to find true critical assessments of an opera singer’s voice in the seventeenth century; most comments tend to the generic, comparing singers to swans or sirens, or waxing lyrical about how divinely or magnificently or wonderfully they perform.44 The quotation given in the title of this essay – ‘una bella voce, un bel trillo, ed un bel passaggio’ – comes from a letter penned by Leonardo Marsili about the singer ‘Aloisia’, and it begins in typical fashion: she had a ‘beautiful voice, a beautiful trill, and beautiful ornamentation’. He does go on to note that the singer was able to modulate her voice depending on the size of the room; that is, she knew to sing more softly in a chamber setting than on the operatic stage. Sometimes observers commented on the strength of the voice; Caterina Galerati (fl. 1701–1721), for instance, apparently had a small instrument but compensated for its size through the use of trills and other musical ornaments.45