I. Introduction

The business and human rights agenda is gaining momentum internationally, perhaps best evidenced through the legislative responses to tackling modern slavery in recent years. Various jurisdictions have tackled the issue through a range of mechanisms, including legislated reporting requirements for business. The California Transparency in Supply Chains Act of 2010 is often credited as leading the charge of business reporting laws, and has been followed in recent years by both international and domestic laws around the world. Given the pace at which these laws have been introduced, there has been little opportunity to critically examine them comparatively. Even less examined is the nebulous question of the effectiveness of these laws.

To contribute to addressing this gap, this article focuses on three recent laws that address the business and human rights agenda. These are the United Kingdom (UK) Modern Slavery Act 2015,Footnote 1 the French ‘duty of vigilance’ law of 2017,Footnote 2 and the Australian Modern Slavery Act 2018 (Cth).Footnote 3 We selected these specific laws for temporal reasons (all were introduced within a three-year period) and because all deal with modern slavery (or human rights more broadly in the case of the French law) in operations and global supply chains. Any corporation that operates across the jurisdictions of these laws, will therefore have to comply with three related, but distinct, legislative attempts to tackle modern slavery.

Comparing these Acts allows for analysis of how the businesses that operate in all three jurisdictions respond to laws that have similar objectives and partially overlapping obligations, but also vary in scope, structure and emphasis. The outcome of the analysis will allow us to scrutinize reporting trends and analyse whether these domestic laws can be mutually reinforcing. In particular, as not all Australian Modern Slavery statements are available at time of writing, this study allows us to examine reporting trends in the UK and France with a view to informing our understanding of reporting under Australia’s Act.

The development of each of these laws can be understood through the lens of reflexive law. Adopting a regulatory approach based on reflexive law assumes that regulation is more acceptable to those to whom it applies if they have been involved in its creation, thus enhancing its effectiveness.Footnote 4 In various ways, the development of the UK, French and Australian laws were influenced by a number of actors, or stakeholders, including civil society and business. Reflexive law-making does not seek to directly regulate behaviour to meet specific objectives. Reflexive regulation aims to improve law’s effectiveness through acceptance of key stakeholders and self-regulation based on reflection. With regard to the three laws examined here, whether reflexive regulation has led to improved effectiveness is questionable as all have been subject to criticism for their limitations in terms of enforcement and therefore effectiveness.Footnote 5 In fact, a recent report by the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC) on the UK Modern Slavery Act concludes that it has ‘failed in its stated intentions’.Footnote 6 The report finds that despite persistent non-compliance by 40 per cent of companies, no injunctions or administrative penalties have been issued to companies failing to report, and that the lack of mandatory reporting areas has led to companies publishing general statements that do not engage with the risks of modern slavery specific to their sectors and regions of operation. Overall, the BHHRC argue that the Act has not driven significant improvement in corporate practices to eliminate modern slavery. Some might argue that the BHRRC critique takes too narrow an approach to assessing effectiveness; for example, it does not purport to measure whether there are increased levels of awareness of the issue of modern slavery within operations and supply chains. Furthermore, there is a strong body of scholarship supporting the related approach of delegating regulatory tasks to businesses and business associations subject to certain conditions and safeguards. Using this ‘meta-regulation’ approach, rather than enforcing, the state becomes more engaged with observing and steering self-regulatory capacity.Footnote 7 Of relevance to multinational enterprises (MNEs) and their global value chain, is the related concept of transnational non-state regulation which sees regulatory arrangements carried out by corporate actors and civil society, in collaboration or separately.Footnote 8 This regulatory pluralism approach may have some merit. Although some are sceptical of the capacity of self-governance to effect ‘responsible business’ practices, others point to the potential for self-regulatory settings, such as multinational corporations, transnational production networks (TPNs), and industry/ non-governmental organization (NGO) partnerships, to fill government regulatory gaps.Footnote 9 Landau draws on meta-regulatory theory to advocate for self-regulatory processes located within a broader framework of accountability, supported by substantive and procedural rights, and with a committed regulator.Footnote 10

The result of the reflexive or meta-regulatory approach is that each of the laws we examine has certain characteristics reflecting the various stakeholders’ involvement, including those within businesses subject to the laws (or likely to be). As discussed in Section II, these characteristics include: the penalties associated with non-compliance, the monetary or other threshold for identifying which companies are subject to the law, the extent of the business covered by the law, and the nature of the modern slavery or other conduct covered by the law. A point of tension between various stakeholders is whether enforcement and compliance mechanisms should be used in business reporting and due diligence laws: civil society often advocate for penalties for non-compliance, and some business stakeholders resist. Braithwaite and Drahos note that coercion is more widely used and more cost-effective than reward for compliance with a global regulatory regime.Footnote 11 They conclude that the main reason for this is that ‘threatening and withdrawing coercion can work well, but promising and reneging on rewards does not’.Footnote 12

Reflexive regulatory theories are also embedded in the most significant international legal development in this area – the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs).Footnote 13 The UNGPs are based on three pillars (Protect, Respect and Remedy): the state duty to protect, the corporate responsibility to respect,Footnote 14 and the state duty to ensure access to remedy. As such, the UNGPs clearly engage state and non-state actors – namely businesses – and as such it has been posited that they promote polycentric governance, a theory of governance premised on the cooperation and interdependence of diverse stakeholders to address a shared problem.Footnote 15 However, as Parker and Howe have argued, the UNGPs are in fact ‘distanced’ from business accountability.Footnote 16 The UNGPs include business within their scope, but do not allow for the participation of other stakeholders, particularly civil society,Footnote 17 and overall provide a diplomatic rather than regulatory solution to conflicts over business violations of human rights.

As well as being influenced by stakeholders, law develops within its own socio-legal context and culture. There can be attempts to adapt laws from other jurisdictions; as discussed below, the Australian Modern Slavery Act was influenced by the UK Act. The benefit of following in another jurisdiction’s legal footsteps is to benefit from rules that have been successfully used elsewhere.Footnote 18 Strict ‘legal transplants’ though are impossible, as law is inseparable from its social and cultural context and transplanting it may not reproduce its effects.Footnote 19 Legal transplants ‘have to interact with pre-existing local arrangements’,Footnote 20 which makes it easier for Australia to adopt corporate regulation from the UK than from France. The final outcome is that each of the three laws exists on a spectrum of multidimensional stringency, based on (a) penalties; (b) coverage of organizations; (c) forms of modern slavery or other issues covered; and (d) extent of global value chain covered.

The challenge for many MNEs is that they are (or will be) directly or indirectly subject to several similar, overlapping reporting requirements but each with a different emphasis. This can increase reporting costs for businesses and perversely draw resource and attention away from addressing the issues themselves. There have been calls for harmonization of business reporting laws,Footnote 21 yet a risk of harmonization is that what is agreed upon is the ‘lowest common denominator’. An alternative approach to provide consistency to the reporting requirements facing MNEs would be to more closely adhere to existing international soft law in this area, in particular the UNGPs which businesses are familiar with aligning corporate responsibility strategy with.

This article examines the UK Modern Slavery Act (MSA) 2015, the French ‘duty of vigilance’ law of 2017, and the Australian Modern Slavery Act 2018 (Cth) as they apply to selected companies who have already reported under the UK and French laws and are expected to report under the Australian law. At time of writing, the Australian repository of modern slavery statements is not yet available with only some early statements being published and the full tranche of statements being due in mid-2021 – the companies we examine in detail here are not among the first batch of Australian statements. How companies have engaged with the UK and French Acts may give us some indication of their likely responses to the Australian MSA. Businesses could identify strategies that best address all reporting requirements while reducing administration, monitoring and enforcement. A few scenarios here are possible – businesses could select the most stringent requirements from each Act and have a unified approach across all jurisdictions, or they adopt a minimalist approach, aware of the over-arching lack of effective penalties, or they prepare differentiated reports for each jurisdiction.

We begin our analysis in Section II by setting the legislative context for each law; we then discuss our methodology in Section III. The findings from the analysis of the French vigilance plans and UK modern slavery statements are presented in Section IV in the following categories: risk management and due diligence, reporting on effectiveness, and supply chain. The analysis of these findings is discussed in Section V, identifying the most commonly used strategies adopted by the reporting entities analysed and commenting on the differences between French and UK reports, and discussing some evidence of the French law setting a higher standard that ‘creeps’ into UK reports. Concluding comments and opportunities for further research are presented in Section VI.

II. Legislative Context

International law has prohibited slavery for more than two centuries – first in the 1815 Declaration Relative to the Universal Abolition of the Slave Trade, followed by an estimated 300 international agreements to suppress slavery.Footnote 22 International Labor Organization (ILO) and United Nations (UN) human rights treaties prohibit slavery and forced labour, and the prohibition of slavery and slavery-related practices are recognized in customary international law, attaining jus cogens status.Footnote 23 With regard to trafficking, there have also been international legal instruments, most recently the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children. Footnote 24 However, legally binding international instruments specifically targeting the responsibilities of businesses, rather than states, are lacking. There have been several years of deliberations by a UN working group on a new treaty on business and human rights,Footnote 25 which as yet lacks widespread support amongst states and businesses. What is more common in the business and human rights sphere, are non-binding soft law provisions. As noted in the introduction, the UNGPs are the primary soft law instrument on business and human rights and are intended to be implemented at a domestic level by states through national action plans (NAPs) on business and human rights. Of the three states we examine in this research, France and the UK have NAPs,Footnote 26 but Australia does not. It is acknowledged that NAPs are not the panacea to tackling business and human rights regulation, but they have been identified as vehicles for the implementation of international obligations and relevant tools to support states’ duties under international law through awareness-raising, and implementation measures as defined by the UNGPs.Footnote 27 Therefore, Australia’s lack of NAP is a gap in the business and human rights regulatory framework.

Another key soft law instrument is the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises,Footnote 28 which are now aligned with the UNGPs.Footnote 29 The guidelines are voluntary principles and standards for responsible business conduct across a number of areas including the environment, sustainability, bribery and employment. Although these are voluntary guidelines, a complaint can be raised with a national contact point (NCP) in OECD member states if a multinational enterprise is believed to have breached the guidelines. There are also sector-specific OECD guidelines such as those specific to the minerals and extractives industries.Footnote 30 As noted below, some companies explicitly refer to the UNGPs or the OECD Guidelines in their modern slavery reporting, indicating that these international measures are part of the legal context.

At a domestic level, corporate laws and criminal laws have sometimes had provisions that could be used to tackle modern slavery. Australia’s Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth) has been amended several times since 1999 to introduce crimes relating to slavery, forced labour and human trafficking. More recently though, we have seen a trend of business reporting laws. The California Transparency in Supply Chains Act of 2010 is often credited as leading the charge of business reporting laws and the United States Dodd Frank Act in relation to conflict materials was also introduced in 2010.Footnote 31 What is sometimes overlooked is that both are pre-dated by the 2008 Corporate Social Responsibility reporting requirements in Denmark.Footnote 32 The 2014 European Union Non-Financial Reporting Directive is another reporting – rather than due diligence – obligation for businesses.Footnote 33 It requires public-interest entities exceeding an average number of 500 employees to include in their management reports a non-financial statement on its performance and impact relating to environmental, social and employee matters, respect for human rights, anti-corruption and bribery matters.

Some jurisdictions have gone beyond the requirement of reporting on modern slavery and other human rights issues to require that businesses apply human rights due diligence (HRDD). HRDD was first articulated in the UNGPs, but has been developed in greater detail in subsequent international documents, notably the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct. Footnote 34 Principle 17 of the UNGPs states that HRDD ‘should include assessing actual and potential human rights impacts, integrating and acting upon the findings, tracking responses and communicating how impacts are addressed’. Later elaborations of HRDD, such as in the OECD Due Diligence Guidance, add a requirement of remediation. HRDD therefore requires companies to do more than just report on human rights risks, although s 16(1)(d) of the Australian MSA asks businesses to report on actions to address risks of modern slavery, including due diligence.Footnote 35 The Netherlands introduced a Child Labour Due Diligence Law in 2019,Footnote 36 and other European countries are also in the process of developing comparable laws. The European Union is currently consulting on the options for adopting measures on sustainable corporate governance,Footnote 37 which may lead to mandatory human rights due diligence.Footnote 38 In our study, the French law is the only due diligence law of the three.

Within this broader context, we now turn to specifically consider the UK, French and Australian laws in the following sections. Although some stakeholders, particularly businesses, advocated for consistency of reporting laws across jurisdictions,Footnote 39 other stakeholders, particularly civil society, sought to improve on previous laws, and so we see both points of convergence and divergence in the resultant laws.

United Kingdom

The UK’s MSA was introduced in 2015. It has seven parts, including protection for victims, civil and criminal provisions, new maritime enforcement mechanisms, and the establishment of an anti-slavery commissioner, but the business reporting obligations in Section 54 are our primary interest in this research. Section 54 was developed in consultation with stakeholder groups with the intention that the transparency created through regular public reporting regarding the steps businesses were taking to eradicate modern slavery from their operations would ‘create a race to the top’Footnote 40 in responsible business practice.

The MSA was influenced by domestic actors and international anti-slavery activism through new abolitionist discourse.Footnote 41 Broad and Turnbull argue that a UK Home Office review of modern slavery identified wide ranging criminal activity and evinced a strong moral component.Footnote 42 They note that government promotion of a modern slavery discourse was supported by the think tank Centre for Social Justice and activist groups but that ultimately, policymaking was characterized by top-down decision-making, a lack of evidence-base and exclusion of key actors. LeBaron and Rühmkorf note that business opposition towards new legislation to raise public labour standards is to be expected and that this was the case in the UK during the development of the MSA whereby business actors champion weak regulatory initiatives.Footnote 43

In addition to the international abolitionist discourse, the MSA was influenced by international and regional law and is intended to give effect to the UNGPs and to be consistent with EU Directive on Non-Financial Reporting. Section 54 (Transparency in Supply Chains etc.) of the UK’s MSA applies to commercial organizations who supply goods or services in the UK and who have an annual turnover above £36 million. The Act requires such businesses to prepare and publish a slavery and human trafficking statement each financial year. The statement must either explain the steps that the organization has taken to ensure that slavery or human trafficking is not taking place in any of its supply chains or own business, or state that they have ‘taken no such steps’. Slavery and human trafficking statements must be approved and signed off by a senior official of the business (e.g., director, senior partner or equivalent). Organizations with a website must publish their statement on their website and provide a link to the statement in a prominent position on their homepage. Organizations without their own website must make their statement available on request. The Act provides for civil enforcement for non-compliance with Section 54.

Beyond the requirement to prepare a statement annually, to have this approved and signed by a senior executive and to publish this on the corporate website, there is little compulsion regarding what the statements include. Section 54 provides guidance regarding what statements ‘may include’, but there is no minimum requirement regarding level of disclosure or detail, indeed stating that no actions have been undertaken meets the Act’s reporting requirement. The term ‘supply chain’ is loosely defined within the accompanying Home Office guidance, with businesses advised that supply chain is understood by ‘its everyday meaning’,Footnote 44 leaving the definition open to interpretation regarding scope and coverage by organizations.

Businesses and commercial organizations are considered within scope of the Act if they carry out business in any part of the UK and where the business’ total turnover exceeds £36 million. This brings international businesses with turnovers exceeding £36 million but with minor UK operations or local turnover within scope of the MSA’s reporting requirement. This latter point has often not been recognized by organizations with international subsidiaries within the UK.Footnote 45

France

The second of the three Acts we consider is the French ‘Duty of Vigilance Law’ introduced in 2017.Footnote 46 This Act is specifically intended to enshrine relevant sections of the OECD Guidelines and the UNGPs. Businesses are required to produce a vigilance plan which includes ‘reasonable vigilance measures to adequately identify risks and prevent serious violations of human rights and fundamental freedoms, risks to serious harms to health and safety and the environment’.Footnote 47 The law applies within France and extraterritorially and provides for victims to bring civil action for remedies.Footnote 48 The first case was brought in October 2019 against energy company Total by Friends of the Earth and other environmental groups which claim that Total has failed to elaborate and implement its human rights and environmental vigilance plan in Uganda.Footnote 49

Therefore, civil society groups are key stakeholders in the French law within a reflexive law framework. As well as taking strategic litigation such as the Total case, NGOs have established a publicly available repository of companies covered by the French law,Footnote 50 in the absence of a Government repository. During the development phase of the law, the discourse from France suggests that the law was the result of an active campaign by civil society groups, including trade unions.Footnote 51 Nonetheless, the other key stakeholder group – businesses – did push back when the constitutionality of the law was challenged before the Constitutional Council. The Council upheld the law but did strike down provisions for substantial penalties for failure to publish plans.Footnote 52

Rather than applying to businesses over a specified revenue threshold, the French law applies to businesses with over 5,000 employees in France or 10,000 employees in France and abroad (both include subsidiaries). As well as applying to the activities of subsidiaries, the law also applies to subcontractors and suppliers with whom there is an established business relationship. A criticism has been that the law is estimated to affect only 150 companies, and businesses in some high-risk sectors (such as the extractive or garment industry) are not subject to the law.Footnote 53

Australia

Australia’s MSA (Cth) was introduced in 2018, taking effect in January 2019 and with the first modern slavery statements due in 2020 or 2021 depending on the entity’s reporting period. Key aspects of the law also draw on terminology and concepts used in the UNGPs. Furthermore, the Act was clearly influenced by the UK MSA. The terms of reference of the inquiry by the Joint Standing Committee into establishing an Australian MSA, begin with the statement: ‘With reference to the United Kingdom’s Modern Slavery Act 2015 … the Committee shall examine whether Australia should adopt a comparable Modern Slavery Act’.Footnote 54 Australian businesses with operations in the UK have already published statements under the UK legislation.Footnote 55 As discussed above, although the UK MSA included multiple legal reforms, including with regard to criminal law, Australia had already introduced criminal law amendments,Footnote 56 and so the Australian MSA is predominantly a business reporting statute. Although there are no penalties for non-compliance, failure to lodge statement can result in the Minister requesting the entity to explain its failure and/or undertake remedial action and where the entity fails to comply with the Minister’s request, the Minister may publish details on the modern slavery register. The Australian MSA also provides for annual Ministerial reporting to Parliament on the implementation of the Act and for a three-year review.

From a reflexive law-making perspective, multiple stakeholders including civil society, academics and businesses made submissions during the consultation phase on the MSA. In addition, leading philanthropist Andrew Forrest and his family have been identified as key stakeholders in promoting the Australian MSA.Footnote 57 The Forrest family had previously established international anti-slavery NGO Walk Free.Footnote 58

Unlike the UK and France, Australia lacks a national action plan on business and human rights. This is despite committing to a consultation with a view to adopting a national action plan in its 2015 universal periodic review by the UN Human Rights Council, following recommendations from the Netherlands, Norway and Ecuador.Footnote 59 The Government established an advisory group to consider the matter in 2017,Footnote 60 but later that year, it withdrew its support for this initiative.

Comparison of the Three Laws

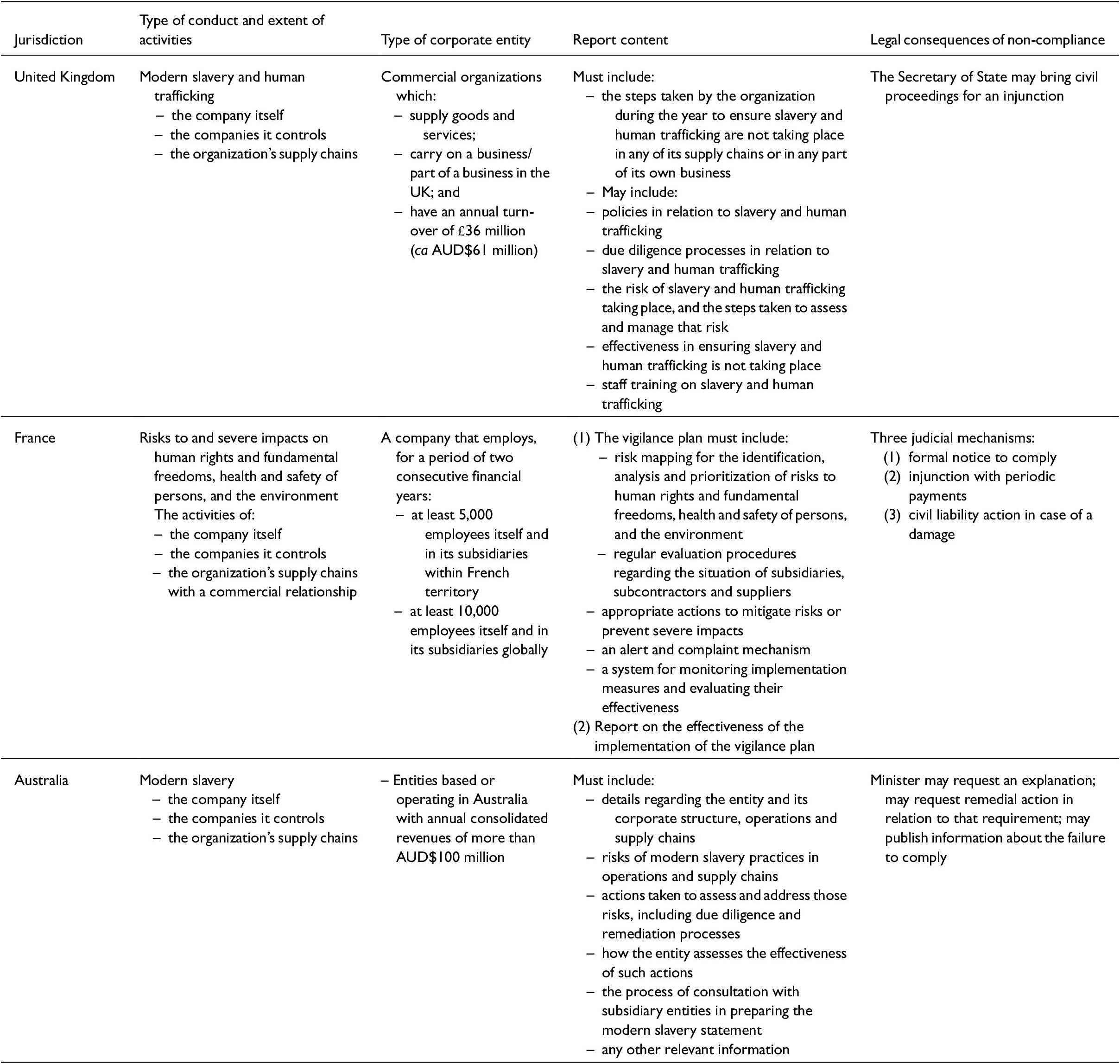

Table 1 provides a summary of the scope of each of the three laws and key differences. The French law has a broader scope of conduct than modern slavery, as it includes human rights and fundamental freedoms, health and safety of persons, and the environment. It is also a due diligence law and therefore asserts more obligation on businesses to take action. In contrast, obligations under the UK and Australian laws are merely to report. Second, the Australian MSA applies also to the Australian Government as a reporting entity. Third, the thresholds differ, with the UK’s £36 million (approximately AUD$61 million, €39 million) being significantly lower than Australia’s AUD$100 million. France’s law is difficult to compare in this regard as it is based on number of employees, rather than a financial threshold, but it also focuses on very large businesses. Fourth, all laws apply to a business operating in any of these jurisdictions as well as their domestic and international suppliers.

Table 1. Scope of Australian, French and British legislation

The three laws share characteristics in terms of reporting requirements – or at least accompanying guidance recommends the following: the supply chain; risk mapping/assessment and management; analysis of subsidiary and supply chain risk; and effectiveness. A few differences are noteworthy. First, the UK MSA states that businesses must report in their annual statements, the steps taken to ensure modern slavery is not taking place, but may include information on policies, due diligence, risk, effectiveness and training. Statements are to be published on the company’s website (if they have one). The only penalty is that the Secretary of State can bring civil proceedings for an injunction. In the French Act, all reporting requirements are mandatory, including risk mapping, evaluation, mitigations, monitoring systems and effectiveness. Vigilance plans are to be included in a company’s annual reports and made publicly available. There are three judicial mechanisms cited in the French Act in the case of non-compliance – formal notice to comply, injunction with periodic payments, and civil liability. The Australian Act’s reporting requirements are also mandatory (‘must’ rather than ‘may’) including structures, risks, effectiveness, and consultation with subsidiaries. The statements must be incorporated into annual reporting and made available on a Government-run public repository. There are no penalties specified. It follows from this comparison that we expect the reporting on modern slavery to change over time as businesses try to emulate the British and the later French legislation in their reporting. That is, in order to comply with the French expectations (and subsequently the Australian), they intentionally ‘over-report’ in the UK.

III. Methodology

Companies which would be required to report under all three laws were identified for comparative analysis. The companies were identified on the basis of having operations in France, the UK and Australia, having prepared and published at least one vigilance plan (under the French legislation) and at least one slavery and human trafficking statement (under the UK legislation), and required to report under the Australian legislation having exceeded the turnover threshold. The companies were initially identified using online repositories of vigilance plans and modern slavery statements hosted by NGOs. Only companies reporting under the French law were chosen from the UK repository; this resulted in 50 companies. As the first reporting cycle in Australia only began in 2020, those expected to be subject to the law were identified on the basis of annual turnover using the IBISWorld database.Footnote 61 The database contained a company record for 24 Australian subsidiaries from the original list of 50 firms, and of these 22 reported a total annual revenue of greater than the reporting threshold under the Australian Act of AUD$100 million for the year ended 31 December 2018. The 22 companies were categorized by industry sector using Standard Industry Classification (SIC) DivisionFootnote 62 (listed in Table 2).

Table 2. Companies Identified as Reporting Under French, UK and Australian Legislation and Able to be Categorized by SIC

Table 3. Nine Companies Selected for Analysis (SIC Division – ‘D. Manufacturing’) from the 22 Companies Deemed Subject to the Australian MSA, French Droit de Vigilance, and UK MSA

In order to narrow the search to identify case study companies for in-depth analysis, the nine companies in the most commonly occurring SIC Division – ‘D. Manufacturing’ – were chosen for further analysis, all of which are headquartered in France. See Table 3 for details of the sample. For these nine companies, copies of all vigilance plans (France) and slavery and human trafficking statements (UK) were analysed. French vigilance plans were found on vigilanceplan.org or on company websites and most were available in both French and English. UK slavery and human trafficking statements were found on modernslaveryregistry.org and company websites.Footnote 63 Where available, all modern slavery reports and vigilance plans were downloaded for analysis. The earliest available reports and statements were produced in relation to the annual reporting period ending in 2016; our sample included available reports and statements up to the annual reporting period ending in 2019 (the last available complete reporting period). This resulted in a total of 16 vigilance plans and 43 slavery and human trafficking statements. Of these, some were published before the French law came into effect in 2017.Footnote 64 These documents were catalogued and analysed with reference to the reporting requirements under the French and UK laws.Footnote 65 Although the content of statements and reports varies depending on the requirement of the laws, some similar themes emerge across the three jurisdictions, allowing for a thematic analysis. Thematic coding of all 59 vigilance plans and modern slavery statements was carried out and collated in Microsoft Excel, which allowed for filtering and analysis.

We recognize limitations to our methodology. The databases used are incomplete and corporate websites are inconsistent. For example, some databases contain plans or statements for prior financial years and some only provide for the current financial year, although company websites often provided the required documents. Financial reporting periods differ within and between jurisdictions, and the disclosure of reports and statements often lag behind the periods to which they relate; yet, the period they cover is not always clearly stated.Footnote 66 Another limitation is the use of third-party translated materials with regard to the French duty of vigilance laws. We compensated for this by triangulating across multiple sources to verify the content. Using a small sample of reports for nine companies allowed in-depth analysis of the 59 vigilance plans and modern slavery statements for manufacturing companies but did not provide a representative sample of the overall implementation of the laws.

IV. Findings

Risk Management and Due Diligence

As indicated in Table 4, companies address risk management and/or due diligence with reference to several types of initiatives. The most common initiative is the use of corporate policies such as code of ethics, conduct, human rights policies, modern slavery policies and whistleblowing policies. References to policies were found in all UK statements and French plans. The use of supplier screening processes and corporate training for staff – and sometimes suppliers – was also common, particularly in the UK.

Table 4. Risk Management and Due Diligence Strategies

In what we have called ‘governance’, there was quite prolific reference to governance but a lack of specificity or quality information. Of the 33 statements that referred to governance and oversight mechanisms, only 13 mentioned a dedicated working group or committee. The best quality information on governance was found in French statements from Kering and L’Oréal, including a list of multiple departments that were included in the committees.

Identifying risks is key to responding to and preventing human rights abuses and modern slavery and is required by the French law, including at the level of subcontractors and suppliers:

The plan shall include the reasonable vigilance measures to allow for risk identification and for the prevention of severe violations of human rights and fundamental freedoms, serious bodily injury or environmental damage or health risks resulting directly or indirectly from the operations of the company and of the companies it controls within the meaning of Article L.233-16, II, as well as from the operations of the subcontractors or suppliers with whom it maintains an established commercial relationship, when such operations derive from this relationship.

Although not mandatory, the UK MSA recommends that statements include: ‘due diligence processes in relation to slavery and human trafficking in its business and supply chains; the parts of its business and supply chains where there is a risk of slavery and human trafficking taking place, and the steps it has taken to assess and manage that risk’.

Some companies excelled in this area, providing high-quality information. Kering, for example, provides excellent information on plans for risk assessment and a detailed methodology for risk mapping, including information on the risk management system they use. L’Oréal also provides good information including risk mapping within subsidiaries broken down by site type and activity type. They also focus on suppliers, broken down by vulnerability of the country and supplier’s industry.

We observed that audits were less commonly used than might be expected or anticipated (see Table 4), and self-evaluation was more common than third-party audits. Audits can be a useful way of engaging stakeholders on the ground and there is some evidence that targeted audits can be effective in detecting modern slavery.Footnote 67 Others caution against a reliance on auditsFootnote 68 – we have not examined their effectiveness in practice as part of this study.

Reporting on Effectiveness

The French Act requires companies to report on their ‘monitoring scheme to follow up on the measures implemented and assess their efficiency’; and the UK MSA recommends reporting on ‘effectiveness in ensuring that slavery and human trafficking is not taking place in its business or supply chains, measured against such performance indicators as it considers appropriate’. Overall, statements were quite weak on the topic of the effectiveness of their risk assessment, with very few identifying targets and few discussing results. Twelve of the 16 French vigilance plans discussed performance indicators and only 10 of the 43 UK statements. Similarly, half of all French plans discussed results, whereas only 10 of the 43 UK statements included a discussion of results. This finding is in line with the findings of FTSE 100, which noted that evaluation of effectiveness ‘was the lowest scoring category’.Footnote 69

The lack of effectiveness measures was particularly the case in the UK, suggesting that due diligence laws that place a higher burden on reporting entities may be more likely to drive effectiveness. Pernod Ricard’s 2018–19 UK Modern Slavery Statement did provide performance indicators and targets (training incorporated in all staff inductions, assessment of policy breaches within one week, etc.), but did not provide any numerical results, or the extent to which they had reached their target. Of all the statements in either jurisdiction, only two used the number of incidents of modern slavery as an indicator (the L’Oreal statements). The lack of quantitative measurement may be a result of reputation management, with the reluctance to share data that could enable direct comparisons between firms, mitigating the risk of being identified for poor performance.

Supply Chain

The French Act refers to ‘reasonable vigilance measures to allow for risk identification and for the prevention of severe violations of human rights and fundamental freedoms, serious bodily injury or environmental damage or health risks resulting directly or indirectly from the operations of the company and of the companies it controls … as well as from the operations of the subcontractors or suppliers’. It also provides for ‘Procedures to regularly assess, in accordance with the risk mapping, the situation of subsidiaries, subcontractors or suppliers’.Footnote 70

The UK Act recommends including information about ‘the organization’s structure, its business and its supply chains’ and ‘its due diligence processes in relation to slavery and human trafficking in its business and supply chains’ and ‘the parts of its business and supply chains where there is a risk of slavery and human trafficking taking place, and the steps it has taken to assess and manage that risk’ and finally, ‘its effectiveness in ensuring that slavery and human trafficking is not taking place in its business or supply chains’.Footnote 71

With regard to supply chains, it appeared that most companies were building these considerations into their contracts with suppliers. The most common types of information provided related to supplier selection or screening policies (42 out of 59 statements) and supplier codes of conduct (37 out of 59). These two were interlinked in many cases, as many companies stated they selected suppliers based on their compliance with the company’s supplier code of conduct. This was the case in statements such as those provided by LVMH Loro Piana that required suppliers to sign and acknowledge their supplier code of conduct prior to engaging them in a business relationship.

A common query with regard to business reporting laws, is how far down the supply chain companies are expected to go. Most of the statements were silent on this issue – only four statements specified what tier of the supply chain they limited their risk assessment to. A few statements provided information about tier two (or below) suppliers and only one statement recorded requiring suppliers to disclose their subcontractors as part of the selection/screening process.Footnote 72 A few reports, such as Essilor Luxottica’s French Duty of Vigilance Plan 2018, mentioned that they restricted risk assessment to tier one suppliers and subcontractors.

V. Discussion

This preliminary analysis of the three laws and a sample of statements submitted under the French and UK Acts provides some indications of how the laws have influenced reporting entities in different ways. Multinational enterprises will be required to report under multiple domestic modern slavery related laws – nonetheless, only 22 of the companies reporting in the UK and in France were found to also be likely to be subject to the Australian MSA – so the fear of widespread ‘red-tape’ implications of thousands of companies being required to report under multiple laws is not yet borne out. It is anticipated that the numbers will increase as new laws are introduced – an area of significant legislative activity across the world at present.

Modern slavery and human rights laws are developing within a reflexive law framework and as such, the companies subject to multiple laws are likely to continue to advocate for a common approach to business reporting. A risk is that the shared format that might be deemed acceptable might be the least onerous option, and therefore potentially less effective. The fact that the UK Act in Section 54(5) suggests but does not require particular content in modern slavery reports, whereas s16(1) of the Australian Act mandates content, might incentivize companies that have reported under the UK Act to add minimal content when reporting in Australia. Early statements submitted in Australia at time of writing show some evidence of reporting entities preparing one report designed to cover more than one jurisdiction – most notably the UK and Australia – despite the differences in the two Acts’ requirements.Footnote 73 Infor Global Solutions’ report, one of the reports covering the UK and Australia, seems to follow the structure of Section 54(5) of the UK Act more closely than that of s16(1) of the Australian Act, and omits one of the suggested elements from the UK Act, namely training.Footnote 74 This would appear to be an example of following the least demanding legislation. Two key questions for all stakeholders – policy makers, researchers, businesses and civil society – are whether the more onerous requirements of a due diligence law, such as the French law, lead to a more thorough and rigorous analysis of risks; and, if so, whether this more rigorous approach might then be used to report under Acts with less onerous requirements, such as the UK and Australian MSAs. To the extent that we can tell from the statements, the French statements typically reported more engaged and ‘on the ground’ activities such as audits. Seven out of 16 French statements reported use of self-evaluation audits and six out of 16 reported third-party audits, compared with only five out of 43 and two out of 43, respectively, for the UK statements (Table 4). For example, Legrand discusses audits in some detail in its French vigilance plans but not in its UK modern slavery statements. There was also a marked difference in discussion of ‘governance’. Fourteen out of 16 French statements discussed governance structures within the organization, compared with 19 out of 43 UK statements. Risk mapping and assessment featured strongly in the French statements (15 out of 16) but was less prevalent in the UK statements (13 out of 43; Table 3). French plans were also more engaged with the question of the effectiveness of their efforts, with 12 of the 16 French vigilance plans including performance indicators, compared with 10 of the 43 UK statements.

When thinking about modern slavery report regimes as legal transplants, it is important to look beyond state legislation. One recent book has analysed the difficulties that states experience translating international definitions of human trafficking into domestic criminal law.Footnote 75 Literature on legal transplants in the broad area of corporate social responsibility has examined how businesses themselves can participate in the transplantation by using international or home country norms in their behaviour abroad, including in disclosure regimes, for example on conflict minerals.Footnote 76 Despite these differences between reporting under the two laws, there are also some indications that the French Act might drive strategies that are used broadly by the entity and reported under the UK MSA. For example, the ‘alert mechanism’ in the French Act,Footnote 77 commonly referred to as a ‘whistleblower’ provision, is specific to the French law and not required under the UK MSA. Nonetheless, 26 out of 42 UK MSA statements referred to whistleblowers or alert mechanisms. For example, Legrand’s Modern Slavery Statements and Vigilance Plans all refer to dispositif d’alerte/whistleblowing. This might be because it is a requirement of the French law and so is adopted by the company more broadly, or it may be because the official guidance document on the UK MSA does contain several references to complaint mechanisms and whistleblowers,Footnote 78 and the UNGPs discuss grievance mechanisms. There was some evidence of text being re-used across French and UK statements/vigilance plans but as the French Act has a broader remit (human rights and environment) and the UK is related only to modern slavery, there typically remained significant differences in the documents.

As discussed above (Section II.C), the French Act is unique among the three in providing that any party with standing can seek a periodic penalty payment for failure to comply with the law. Brabant and Savourey argue that these periodic penalty payments are the primary tool available for civil society to ensure the existence and effectiveness of vigilance plans; they also argue that businesses may be wary of the potential reputational damage related to the publication of a decision, thereby strengthening the preventative objective of the law.Footnote 79 This aligns with Braithwaite and Drahos’ finding that in global business regulation, coercion is more widely used and more cost-effective than reward for compliance.Footnote 80 Brabant and Savourey argue: ‘The quest for an effective implementation of the plan is thus one of the characteristics of the Law’.Footnote 81

Therefore, the penalties available under the French law and the higher engagement with risk discussed in our sample suggests that there is potential for the French law to drive more robust risk analysis and response. However, the question remains – does this lead to improved human rights and environmental outcomes on the ground? And how might we assess this? Our analysis has shown that reporting of quantitative measures of effectiveness by businesses are lacking. Given the strong focus globally on new laws related to modern slavery, business and human rights, sustainability and other related forms of business reporting, more research is required to develop a robust framework for assessing the effectiveness of such laws.

Overall, we note that more onerous forms of due diligence and risk assessment activities such as audits are less commonly used than the somewhat less demanding measures such as introducing policies and delivering training. At this stage, it appears that companies are analysing only the first tier of their supply chains, although the topic of tiers is not discussed in much detail in many of the statements and plans. It is possible that the reporting will be more of an iterative process where over time companies will dig deeper into their supply chains having ‘tested the water’ with these early statements.

The question of whether companies were influenced by international (soft) law in their reports is also of interest and many companies did refer to international law and/or membership of relevant international networks. Several of the companies mentioned membership of the UN Global Compact and/or referenced the UNGPs, and several referred to the OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises (OECD Guidelines). It was commonly stated by these companies that the UNGPs and OECD Guidelines were used in developing their policies, codes of conduct, codes of ethics, or in their overall approach to sustainable business and supply chains. For example, the Schneider 2016 UK Modern Slavery statement noted that the CEO of Schneider Electric was President of the UN Global Compact in France. This observation supports our assertion that leveraging soft law that firms are already familiar with may provide an approach to drive consistency in the reporting by MNEs.

There were references to other international legal instruments or regulatory frameworks and memberships. These were less frequent but included: the ILO Convention No. 29 on Forced Labour, the Kimberley Process for diamonds, the Better Cotton Initiative, ISO 14001 certification of sites, membership of Transparency International and the Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply. From a reflexive law perspective, our data suggest that an influential international stakeholder in this regulatory area is the UN Global Compact.

VI. Conclusion

This study of the French Droit de Vigilance, the UK Modern Slavery Act and the Australian Modern Slavery Act found that only 22 companies globally will be required to report under all three laws. Therefore, due to thresholds and other eligibility criteria, such human rights and modern slavery related laws do not yet have widespread coverage. Using a subset of this dataset of 22 companies, we analysed 59 French vigilance plans and UK modern slavery statements published by nine manufacturing companies. This provided some preliminary analysis of how businesses have reported under the French Droit de Vigilance and the UK Modern Slavery Act. Reports under the Australian Modern Slavery Act for these companies were not yet published at time of writing.

The three laws share characteristics in terms of reporting requirements – or at least accompanying guidance recommends the following: the supply chain; risk mapping/assessment and management; analysis of subsidiary and supply chain risk; and effectiveness. The French Act has a broader scope as it is a due diligence, rather than simply a reporting law. It also includes obligations to exercise due diligence with regard to human rights and fundamental freedoms, health and safety, and the environment. It is the only Act of the three with substantive penalty provisions. All reporting requirements in the French and Australian Acts are mandatory, but the UK Act has limited mandatory reporting requirements.

Overall, the more onerous requirements of the French law were reflected in the content and level of detail in the vigilance plans, compared with the UK modern slavery statements. However, for some companies, there were strong similarities between the UK and French publications, indicating ‘creep’ from the French Act into UK reports or a ‘race to the top’. Given the very different requirements and scope of the French and UK Acts, similarity between reports was more limited than we might expect to see between UK and Australian modern slavery statements. Although outside of our dataset, early statements submitted in Australia at time of writing show some evidence of reporting entities preparing one report to meet the requirements of both the UK and Australian MSAs.

Internationally, new laws are developing at domestic, regional and international levels to address modern slavery, business and human rights, sustainability and related issues. As such, further research is required to develop a robust framework for assessing the nebulous question of the effectiveness of such laws. More systematic analysis of business reports could be facilitated through automated text analysis supported by machine learning.Footnote 82 The motivation and drivers behind differing levels of engagement by businesses in reporting under these laws should be explored. In particular, do the reflexive or transplanted nature of the legal norms influence a firm’s behaviour? The laws have been developed within a reflexive law framework, drawing on stakeholder inputs. The relative weakness of the laws and the current lack of enforcement mechanisms and penalties, particularly in the UK and Australia MSAs, probably reflect opposition from some businesses towards such measures. As such, researchers and civil society remain critical stakeholders and effective oversight and analysis of business reports is germane to effectively tackling human rights abuses and modern slavery around the globe. As transnational businesses become subject to numerous modern slavery reporting obligations, what we may see the kind of non-state means of legal transplantation described by Frost and by Tsai and Wu, although it is too early to say whether this will lead to a race to the top or to the bottom in the robustness of reporting.Footnote 83

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge research assistance from Peta-Jane Hogg, Elise Milroy and Michelle Lam.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.