Introduction

Disasters are emergency events that overwhelm the resources of the region or location in which it occurs, resulting in substantial human suffering, loss of life, and severe economic harm. Reference Tucker1 Disaster preparedness and management refer to the measures taken before a disaster, aiming to minimize life loss, critical services disruption, and damage when the disaster occurs. Reference Nekoie-Moghadam, Kurland, Moosazadeh, Ingrassia, Della Corte and Djalali2 Thus, preparedness for disasters should be an integral part of the normal development plan of communities and countries.

Hospitals provide essential primary emergency healthcare to the victims of disasters to ensure their recovery. Reference Khorram-Manesh, Hedelin and Ortenwall3 Extensive research has been focused on the preparedness level of hospitals for disasters. In Switzerland, about 82% of hospitals had a plan for responding to catastrophic events. Reference Dami, Yersin, Hirzel and Hugli4 Another study in Singapore reported that 75.3% of health care workers felt that the institution was ready for a disaster incident. Reference Lim, Lim and Vasu5 In contrast, studies in the USA stated that hospitals were mostly unprepared for disasters. Reference Kaji and Lewis6,Reference Baack and Alfred7

In the Middle East, disaster preparedness of hospitals has been rated as inadequate despite the region experiencing many disasters. Reference Najafbagy8-Reference Morabia and Benjamin11 Improper preparation of hospitals may be due to ambiguity about the roles and duties of individuals or groups, ineffective communication, absence or inadequate planning, deficient training of personnel, and hospitals not aligning with the community disaster response plans. Reference Kaji and Lewis6-Reference Manley, Furbee and Coben12

Saudi Arabia has faced tremendous problems arising from disasters over the last 3 decades, which were linked to floods, building collapse, religious rituals, modernization, water-borne diseases, and technology-induced disasters. Reference Alshehri, Rezgui and Li13,Reference Al-Majed, Adebayo and Hossain14 Evaluation of hospital preparedness for such emergency events is of great importance. According to the Central Board for Accreditation of Healthcare Institutions (CBAHI) in 2015, there were approximately 72 private and government hospitals of which over 80% were not accredited in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Reference Fouad15 As the level of disaster preparedness of the hospitals in Eastern Saudi Arabia is currently not known, there is an urgent need to ascertain the level of preparedness for disasters, which could occur without warning. Identification of the degree of hospitals’ preparedness in this region of Saudi Arabia can be used to develop effective strategies for managing potential catastrophes. Such knowledge can guide policy-makers in the hospital setting to come up with actions towards strengthening the readiness of their hospitals for disasters whenever they occur. Therefore, the current study was conducted to assess disaster preparedness of the hospitals in the Eastern region of Saudi Arabia.

Methods

The STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Statements) guidelines were followed in reporting this cross-sectional study. Reference von Elm, Altman and Egger16

Study Design and Population

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study of all hospitals (n = 72 hospitals) in the Eastern Region of Saudi Arabia between July 2017 and July 2018. The included hospitals were selected using convenience sampling.

Data Collection

Before data collection, ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of New England (HE17-155) and the Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia (IRB00010471). The questionnaire was taken to the targeted hospitals accompanied by a facilitating letter from the Ministry of health in Saudi Arabia as well as a cover letter stating the importance of the study and providing information about the aim and objectives of the study as well as ethical issues guiding their participation in the exercise. Every hospital was required to appoint a department director who would be responsible for organizing the completion of the survey. For those questionnaires with inconsistent and/or incomplete responses, 1 or 2 follow-up visits or telephone calls were made to ensure completeness and consistency as well as the improvement of response rate. Each returned questionnaire was carefully checked for its consistency and completeness. The data from returned questionnaires were then transferred into a database for analysis. A total of 72 hospitals were surveyed and 63 hospitals responded with a response rate of 87.5%.

Study Questionnaire

The survey was adapted according to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) National Health Sector Emergency Preparedness and Response Tool and Hospital Emergency response checklist. 17,18 The questionnaire consists of 12 sections and 93 closed-ended questions. A pilot study tested the questionnaire. External reliability and internal reliability were tested by test-retest and Cronbach’s alpha (α) method, respectively. The data collected focused on the following 12 areas of interest: (1) hospital and physician demographic data; (2) command and control; (3) disaster plan; (4) communication; (5) education and training; (6) triage; (7) surge capacity; (8) hospital logistics, equipment and supplies; (9) monitoring and assessing hospital disaster preparedness; (10) safety and security; (11) post-disaster recovery; and, (12) assessment of hospital’s disaster preparedness indicators.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics of continuous data were generated, including mean and standard deviation (SD). For dichotomous data, frequency counts and percentages, and crosstabs with the χ2 statistic were calculated. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 for all statistical tests. Data analysis was conducted using the statistical analysis software package SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Scientists) version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Results

Demographic Data of the Participants and Hospitals’ General Information

A total of 72 hospitals were surveyed, and 63 hospitals responded with a response rate of 87.5%. This study thus included 63 participants who responded on behalf of 62 hospitals. Of the participants who completed the survey, 90.5% were males and 9.5% females. About 57% of the participants were aged 41 to 50 years. Approximately 29 (46%) of them were heads of disaster units, 25 (39.7%) were hospital managers, and 9 (14.3%) were heads of emergency departments. Most of the participants were well-experienced with about 10 to 20 years of experience (80.9%).

About 58.7% of included hospitals were governmental, while the private hospitals represented 41.3% of the participating hospitals. Most of the hospitals were secondary (76.2%) and non-teaching (96.8%) hospitals. The employee numbers ranged from 1 to 1000 in 73% of the hospitals. The number of beds was 100 to 500 in 50.8% of hospitals. The average number of patient admissions per day was less than 10 in 42.9%, more than 30 in 31.7%, and 11-30 in 25.4% of the hospitals. This study revealed that 60.3% of the hospitals had more than 100 patients in the outpatient centers. About 12.7% of the included hospitals have more than 20 beds in both the ICU and the Emergency department (see Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic data of the participants and hospitals’ general information

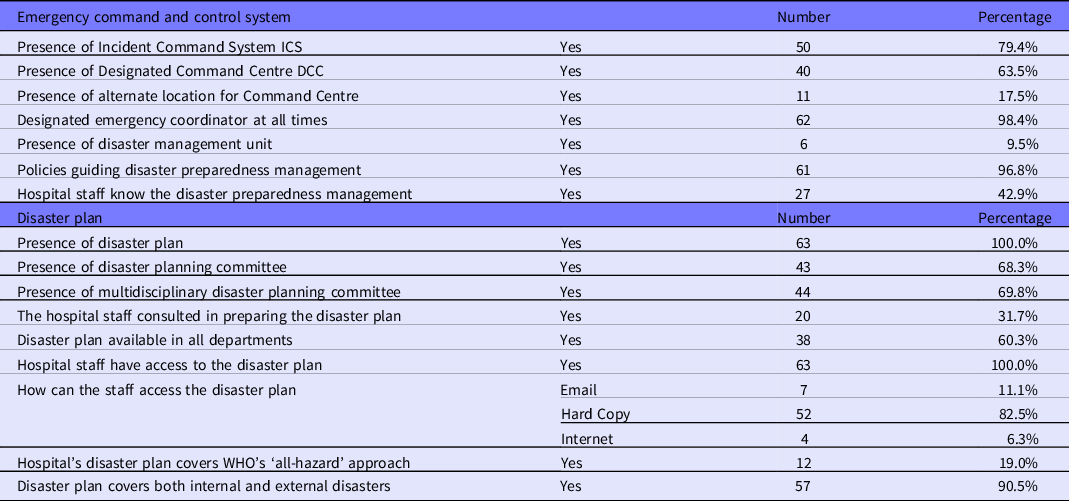

Disaster Plan and Emergency Command and Control

All the included hospitals had a disaster plan that was accessible by all staff members. The disaster plan was available in all departments in only 60.3% of the included hospitals using a hard copy. In total, 69.8% of all hospitals had a multidisciplinary disaster planning committee. WHO’s “all-hazard” approach was covered in the disaster plan of 19% of all included hospitals, and about 90.5% of hospitals covered both external and internal disasters in their plan. About 79.4% and 63.5% of the included hospitals had an Incident Command System (ICS) and Disaster Command Centre (DCC), respectively. However, only 17.5% of the included hospitals had the alternate location for Incident Command Centre. The proportion of designated emergency coordinator was 98.4% of the included hospitals (see Table 2).

Table 2. Disaster plan and emergency command and control

Training and Education, Triage, Drills, and Communication

All hospitals conducted a triage and provided its guidelines and forms. Nurse specialists performed the triage in most hospitals (71.4%). Besides, 96.8% of included hospitals provided training on triage, and 68.3% of them had a triage area for receiving mass casualties. All respondent hospitals established an educational program on the disaster preparedness that occurred once per year in 69.8%, twice per year in 7.9%, and occasionally in 22.2% of the participating hospitals. An assessment action plan was developed to assess staff knowledge either by drilling or formal examination in all included hospitals. Among all the hospitals, 74.6% were considered to have enough new staff orientation about disaster preparedness. The presence of public information officers and back-up communication systems were reported in about 19% and 58.7% of the included hospitals, respectively. Assessing hospital disaster preparedness was done using drills in 62 hospitals. Most of the hospitals (85.7%) performed a yearly hospital disaster drills and most performed an annual review of the disaster preparedness plan (69.8%) (see Table 3).

Table 3. Training and education, triage, drills, and communication

Surge Capacity, Logistics, Safety & Security, and Post-disaster Recovery

About 76.2% of the hospitals had designated care areas for patient overflow, while only 46% had additional area to accommodate patient overflow during a disaster. Furthermore, 30.2% had a designated area that can be used as temporary morgues during a disaster. Interestingly, 85.7% of the hospitals had adequate number of HCPs to manage patient overflow. Unfortunately, only 4.8% of the hospitals had the availability of calling staff from other hospitals in case of disasters. More than 70% of the hospitals had 1-5 working ambulances, and 20% of the hospitals had 6-10 working ambulances. All the hospitals had updated inventory of all equipment, supplies and pharmaceuticals and about 94% of them have contingency agreements with vendors to supply resources in case of disaster. Blood banks were found in 82.5% of the hospitals. All the hospitals have backup generators and storage tanks. Regarding hospital safety and security, more than 50% of the hospitals have a fence. Also, about 23.8% had a fire department, and 9.5% reported having an area for radioactive, biological, and chemical decontamination. A total of 62 hospitals reported attempts to capture lessons learned following disaster responses in the form of meetings. Unfortunately, only 9.5% of the hospitals have post-disaster recovery assistance programs like counseling and support services (see Table 4).

Table 4. Surge capacity, logistics, safety & security, and post-disaster recovery

Assessment of Hospitals’ Disaster Preparedness Indicators

The mean score of hospital command and control was 2.92 (± 1.1), 3.13 (± 1.07) for hospital disaster plan effectiveness (moderate effectiveness), 2.65 (± 0.74) for hospital disaster communication, 2.87 (± 0.73) for education and training of staff, and 2.72 (± 0.89) for hospital triage effectiveness (slight effectiveness). The mean of overall hospital disaster preparedness showed a slight to moderate hospital preparedness (mean = 2.99 ± 1.04) (see Table 5).

Table 5. Assessment of hospitals’ disaster preparedness indicators

Discussion

This cross-sectional study was conducted to assess disaster preparedness of hospitals in the Eastern region of Saudi Arabia. Overall, it showed that the majority of hospitals had sufficient resources for disaster management such as specialized staff, triage and surge capacity, specific policies, and staff communication database (although some aspects were defective); However, the overall effectiveness of hospitals’ disaster preparedness was slight to moderate. These results highlight the need for further improvements in the hospitals’ disaster preparedness capacity in the examined area.

In a recent integrative review by Alruwaili, et al., Reference Alruwaili, Islam and Usher19 the authors found 19 studies that reported hospitals’ disaster preparedness in the Middle East. The majority of these studies (13) found the level of preparedness for disasters in the assessed hospitals to be very poor, poor, or moderately effective; only 6 studies ranked their hospitals as well or very well-prepared for disasters. The findings from the literature review therefore support the findings of the study reported here. The studies reported in the literature review cited the lack of contingency plans and inadequate availability of resources as the main factors responsible for impaired disaster preparedness. In addition, the literature review highlighted the lack of published research on hospital disaster preparedness in the Middle East, especially in relation to Saudi Arabia where there were only 2 previous published studies. Reference Alruwaili, Islam and Usher19

In the current study, 79.4 and 63.5% had ICS and DCC, respectively. Moreover, 96.8% of hospitals had policies to guide disaster preparedness management; However, only 42.9% of hospitals had staff awareness about those policies. Another study by Aladhrai et al. in Yemen found the preparedness level of 7 out of the 11 included hospitals was unacceptable based on disaster management guidelines. Reference Aladhrai, Djalali, Della Corte, Alsabri, El-Bakri and Ingrassia20 In Iran, Djalali, et al. found that disaster preparedness was poor, using determinants that included information management, local databases, and disaster handling procedures. These findings highlight the need to improve the education and awareness of hospital staff about disaster preparedness plans and policies. Another related finding was that all hospitals had educational programs on disaster preparedness and an assessment action plan. However, among these hospitals, only 74.6% had enough staff orientation about the disaster preparedness. Reference Djalali, Castren and Khankeh21

The current study showed a moderate level of education and training of staff about disaster preparedness. These results correspond with the findings by Al-Thobaity and colleagues, the authors reported a moderate level of knowledge about disaster preparedness among nurses in Saudi Arabia. The interviewed nurses perceived themselves as not well-prepared for disasters and expressed willingness to improve their knowledge and skills in this regard. Reference Al Thobaity, Plummer, Innes and Copnell22 In another study by Bajow, et al., the authors concluded that the evaluated hospitals suffered from a lack of training and management during disasters, despite the existence of tools and indicators that could be used to assess hospitals. Reference Bajow and Alkhalil23 These studies, along with other studies published from the Middle East, suggest that personnel involved in disaster management (including physicians, nurses, safety officers, and paramedics) should receive more training and testing to enhance their disaster preparedness. Reference Al Khalaileh, Bond and Alasad10,Reference Aladhrai, Djalali, Della Corte, Alsabri, El-Bakri and Ingrassia20,Reference Adini, Laor, Hornik-Lurie, Schwartz and Aharonson-Daniel24

Generally, the hospitals in this study reported sufficient resources for triage and surge capacity. For example, all hospitals performed triage with clear guidelines. In addition, 96.8% of the included hospitals provided training on triage, and 68.3% had a triage area for receiving mass casualties. These numbers reflect adequate triage preparedness, but there is still room for improvement. A similar study in Tanzania reported that only 10 of 25 hospitals had a designated triage area, and only 8 (32%) provided routine training for triage personnel. Reference Koka, Sawe and Mbaya25 Another study in Iran showed that the triage system was used in all included studies. Reference Shojaei, Maleki and Bagherzadeh26 The current study showed that 76.2% of the hospitals had designated care areas for patient overflow, and 30.2% had designated areas that can be used as temporary morgues during a disaster. The aforementioned Tanzanian study cited that 80% of their hospitals had a contingency area to provide care in emergency situations, while only 8.3% had a temporary morgue to accommodate patient overflow. Reference Koka, Sawe and Mbaya25

A striking finding of this study is the lack of post-disaster recovery assistance programs like counselling and support services; only 9.5% of the evaluated hospitals had similar programs. In all 63 hospitals, the method used to capture lessons learned following disaster response was meetings. Generally, the disaster recovery phase is rarely addressed in hospitals’ disaster plans. Reference Richter27 This study highlights the need to develop clear post-disaster recovery plans that are well-integrated within the hospital disaster preparedness policies.

Other weak spots were detected in the disaster preparedness systems in the evaluated studies. For example, only 19% of hospitals covered the WHO All Hazard approach, which is beneficial to have a holistic approach to disaster management. Reference Lindell28 Moreover, public information officers and back-up communication systems were present in about 19%, and 58.7% of the included hospitals, respectively. In terms of safety preparations, only 23.8% of the evaluated had a fire department, and only 9.5% had an area for radioactive, biological, and chemical decontamination.

Only 12.7% of hospitals had beds exceeding 20 for both the ICU and emergency departments. Such lack of sufficient beds may be an indication that in most of the hospitals, a disaster event may be overwhelmed. Enough facilities are vital to ensure all the patients would have the best quality of care during surges associated with disaster events. Reference Tang29 It is shown those disaster preparedness capacities depending on the ownership as well as their respective levels. For instance, public hospitals were demonstrated to have more resources; from higher numbers of staff to adequate medical equipment compared to private hospitals. Reference Shojaei, Maleki and Bagherzadeh26 Unsurprisingly, this was due to the access to funds from the government compared to private hospitals that relied on owners’ funding. Reference Adini, Laor, Hornik-Lurie, Schwartz and Aharonson-Daniel24 Similarly, the different level hospitals, i.e., primary, secondary and tertiary were shown to differ in their capabilities, with the secondary and tertiary levels being more equipped for handling diverse health issues including having more qualified and highly experienced medical professionals. Reference Adini, Goldberg, Laor, Cohen and Bar-Dayan30

Based on the findings of the present analysis, as well as previous studies published from Middle Eastern countries, some recommendations can be drawn. These recommendations include (1) routine training for personnel involved in hospital disaster management, (2) using drills and practical exercises to assess staff preparedness, Reference Al Khalaileh, Bond and Alasad10,Reference Alruwaili, Islam and Usher19,Reference Aladhrai, Djalali, Della Corte, Alsabri, El-Bakri and Ingrassia20,Reference Adini, Laor, Hornik-Lurie, Schwartz and Aharonson-Daniel24 (3) developing highly functional ICS to improve response timeline and accountability, Reference Yarmohammadian, Atighechian, Shams and Haghshenas9,Reference Sobhani, Khammarnia, Hayati, Ravangard, Heydari and Heydarvand31 , (4) engagement of external stakeholders and the communities in developing disaster preparedness programs, Reference Bajow and Alkhalil23,Reference Fares, Femino and Sayah32 and (5) improvement of the communication system between administrative and clinical staff. Reference Aladhrai, Djalali, Della Corte, Alsabri, El-Bakri and Ingrassia20

In conclusion, the majority of hospitals had sufficient resources for disaster management; however, the overall effectiveness of hospitals’ disaster preparedness was slight to moderate. Some recommendations to improve hospitals’ disaster preparedness should be proposed, including improved staff training and testing, better communications and safety procedures, and adoption of a holistic approach for disaster management.