Introduced in Paris in the middle of the seventeenth century, Italian opera took a long time to conquer French audiences. The genre of the spoken tragedy, represented by the works of Pierre Corneille and Jean Racine, had brought French theatre since the 1640s to a point of perfection: the notion of a play being sung throughout was thus met with much scepticism. French desire for cultural hegemony also resisted opera, which was perceived as an Italian import. The fate of this genre was also complicated at the political level: Cardinal Mazarin’s attempt to impose opera in France did not sit well in the hostile climate generated by the Fronde (1648–1653), during which time several members of Parliament and high-ranking nobles vehemently opposed strengthening the absolute monarchy. While Italian influence was considerable in the artistic domain, it was progressively restricted to theatrical architecture, machinery, and décors, all aspects that would nevertheless become paramount for the development of ‘pièces à machines’, that is, spectacular theatrical plays mostly performed on private stages – princely residences, the king’s palaces – and in Parisian public theatres.

As in other European countries, French opera arose from the development of the divertissement de cour in combination with the new expectations of urban audiences, who wanted to enjoy in public theatres the performances usually restricted to the court – thus, the significant imprint left by the ballet de cour on French opera, in which dance is an essential ingredient. All these factors explain the fairly late year – 1671 – of the first public performance of a French opera, Pomone, on a libretto by Pierre Perrin (c. 1620–1675) with music by Robert Cambert (c. 1628–1677). Founded by Perrin and Alexandre de Rieux, Marquis de Sourdéac, in 1669, the Académie d’Opéra (renamed in 1671 Académie Royale de Musique) promptly institutionalised French opera through the suppression of all foreign influences, securing for many decades to come the preservation of a specific French model.

The Ballet de Cour

During the first half of the seventeenth century, the ‘ballet participatif’ (participatory ballet) – today known as ballet de cour – was the prevalent divertissement at the court. It was meant to entertain courtiers, members of the royal family, and the king himself, and offered them the possibility of participating. The practice of hiring commoners as professional dancers and having them mingle on stage with members of the court began in 1630. However, the final grand ballet danced at the end of these spectacles was restricted to courtiers only.1

Dance – in addition to fencing and horse ballet – was part of the formal education of young French aristocrats. The young king had daily lessons with his maître à danser (dance master). During the seventeenth century, dance played an essential social and artistic role in court life, not only during the increasingly codified great balls but also during exceptional performances that would usually take place during the carnival season.2

The origins of the ballet de cour go back to court festivities and divertissements: prime examples are those ordered by Queen Catherine de’ Medici at the end of the sixteenth century.3 In keeping with the legacy of masquerades and large-scale political ballets of the Renaissance, these ballets were conceived by the intendants of princely houses, or, when motivated by less prestigious demands, improvised by the courtiers themselves.4 The content of most of these seventeenth-century spectacles is known to us through their libretti, which remain nevertheless without much detail.5 Only the most important or monumental ballets were preserved thanks to commemorative publications in connection with their political agenda.6

Historically, a ballet consisted of a succession of very brief danced sequences called entrées (entrances). When the number of entrées was extensive, the ballet was divided into parties (parts). These parties were sometimes unified by a single subject (for instance, the Ballet Royal de la Nuit). Generally, however, variety and surprise were favoured. As a collective enterprise, the ballet nevertheless had one author responsible for the general dessein (design) – that is to say, the subject and organisation of the plot. The responsibility for the music and for the poetic text was delegated to others. In parallel with printed occasional poems lauding patrons, printed programmes or booklets detailed the dessein, with an explanation of the décors and the characters. Later, these booklets would also give the text of the narrations sung by the chorus and the soloists, as well as the ‘verses for the characters’, in either a laudatory tone or a comic vein. These printed materials fulfilled a social function that was much appreciated by the audience, who would attempt during performances to identify the masked dancers.

The composers of the Chambre du Roi (the king’s chamber) provided different types of music according to their own specialties: the dancer and composer Louis de Mollier (c. 1615–1688) composed ballet music, Jean de Cambefort (c. 1605–1661) récits, and so on. These scores usually required an ensemble of lutes, violins, or flutes; choirs set for four or five voices; and solo parts. A group of dancers could also include musicians: the leader could sing, often accompanying himself while surrounded by other musicians. In 1673, the French writer Charles Sorel praised the lute, as ‘there is grace when holding it and pinching [its strings]’, stressing that ‘one can dance and walk’ while playing.7

Some ballets were organised around a single plot: Le Ballet comique de la Reine (1581) is about Ulysses being freed by the gods from Circe. Other ballets were based on Italian epics: Le Ballet de Monseigneur le duc de Vandosme ou Ballet d’Alcine (1610), Le Ballet de la délivrance de Renaud (1617),8 and Le Grand Ballet du Roi sur l’aventure de Tancrède en la Forêt enchantée (René Bordier, 1619). Most of the music for these three ballets is attributed to Pierre Guédron (1564–d. 1619–1620). Other ballets were thematic: Le Ballet des Fées des Forêts de Saint-Germain (1625) or Le Grand Bal de la Douairière de Billebahaut (Bordier, Antoine Boësset; 1626). Ballets with a laudatory purpose alternated with more informal divertissements and masquerades: some of them – those related to the carnival season – were grotesque, and their performances were often lengthy.

One such work is the allegorical Ballet Royal de la Nuit (Clément, Cambefort, Mollier, Jean-Baptiste Boësset [1614–1685], Michel Lambert [c. 1610–1696]), which celebrated the end of the Fronde conflicts in 1653: it included no less than forty-three entrées, among which was Ballet en Ballet and two short ballets in several acts each: Les Nopces de Thétis and the Comédie muëtte d’Amphitrion. In 1654, Le nozze di Peleo e di Theti or Les Noces de Pélée et de Thétis (Francesco Buti, Carlo Caproli [1615/20–1692/5]) was commissioned by Mazarin after the Fronde as an ‘Italian comedy in music, mixed with a ballet on the same subject, danced by His Majesty’. The opera is augmented by some ten entrées chosen by François de Beauvilliers, Duke of Saint-Aignan, Premier Gentilhomme de la Chambre du Roi, and set to music by court musicians. The king and his family participated in these danced entrées, in the company of the young Giambattista Lulli.9

Les Amants magnifiques, the divertissement created by Molière and Lully for the carnival in 1670, is sometimes considered to be the last participatory ballet: it is made up of two small poetic and musical units, bookending a comédie-ballet. Each of them is organised around the figure of the king as Neptune (first intermède) and Apollo (‘Les Jeux Pythiens’). The king, however, did not dance.10

The ballet de cour is emblematic of the popularity of dance within the court and, more broadly, among the French aristocracy. This explains why the 1669 status of the newly formed institution, the Académie Royale d’Opéra, allowed the nobility to participate in operas, whether as dancers or as singers, without endangering their privileged social rank. The situation was slightly different outside the court: although four courtiers took part in the première of the first opera performed at the Académie Royale de Musique – Les Fêtes de l’Amour et de Bacchus (1673), a medley of court intermèdes reused by Lully11 – over the years, the separation on stage between amateur dancers (courtiers) and professional ones became increasingly marked. Participatory dance persisted only within colleges, especially those of the Jesuits: pupils who played in Latin tragedies would also dance on stage during intermèdes, often mingling with professional dancers.12

Having taken the reins of the Académie Royale de Musique, Lully attached to it a professional ‘corps de ballet’ (which included several members of the Académie Royale de Danse that had been created in 1660) and a permanent maître de ballet.13 During the academy’s first decades, professional female dancers, such as the celebrated Mlle Verpré, performed at the court; they were dismissed during the 1670s but continued to be hired by the Académie Royale de Musique.14 For the Parisian performance of the ballet Le Triomphe de l’Amour (Philippe Quinault, Lully; Palais-Royal, 6 May 1681), Lully hired new professional female dancers to replace the female courtiers who had created those roles earlier in the year at the court (Saint-Germain-en-Laye, 21 January). From that point on, female dancers came to be among the most celebrated performers of the Académie Royale de Musique’s company.

Italian Opera in Paris

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the strengthening of the absolute monarchy was affirmed, justified by the divine-right theory of kingship. Cardinal de Richelieu, Chief Minister of Louis XIII, displayed his artistic patronage through the creation of the Académie Française (1635), the protection of authors, and the development of theatre. Designed on the Italian model by the architect Jacques Lemercier, Richelieu’s own theatre was built in his Palais Cardinal (later Palais-Royal) and inaugurated in January 1641 with a ballet, La Prospérité des armes de la France (Jean Desmarets de Saint-Sorlin, François de Chancy, Mollier, Michel Verpré), which he had himself commissioned.15 It is in this context that Jules Mazarin (Giulio Raimondo Mazarini, 1602–1661) arrived in Paris in December 1643 as the Pope’s extraordinary nuncio. Richelieu designated Mazarin to succeed him as Chief Minister to the king. Pursuing Richelieu’s politics of state interventionism in artistic life, but also seeking to strengthen the ties between France and the Papal states, Mazarin emulated the example of the Barberini family in Rome, who had been among the most important patrons and mentors of his youth.16

In order to foster spectacles in the Roman style, Mazarin, beginning in 1641, invited the composers Marco Marazzoli (c. 1602–1662), Mario Savioni (1606–1685), and Caproli, as well as Italian singers, to the French court.17 The presence of an Italian itinerant company, the Febiarmonici, is documented for the year 1644.18 During the autumn, other musicians arrived at the court, answering the French invitation: the singer Anna Francesca Costa (‘la Checca’; fl. 1640–1654), the castrato Atto Melani (1626–1714), and his brother, the composer and singer Jacopo Melani (1623–1676), were sent by the Médici. The castrato Marc’Antonio Pasqualini (1614–1691) was sent by the Pope; and the tenor Venanzio Leopardi (as Venanzio d’Este), at the service of Cardinal Colonna, was called to Paris by the Duke of Modena. One of the greatest singers of her time, Leonora Baroni (1611–1670), accompanied by her husband, arrived at the French court in 1644 on the invitation, mediated by Mazarin, of Anne of Austria, the queen regent of France. They all participated in the première of Luigi Rossi’s Orfeo at the Palais-Royal in 1647 (more on this later). After that, the company was disbanded, but the habit of bringing Italian musicians to the French court had begun. After the end of the Fronde conflicts, the famous Roman singer Anna Bergerotti arrived in Paris in 1655.

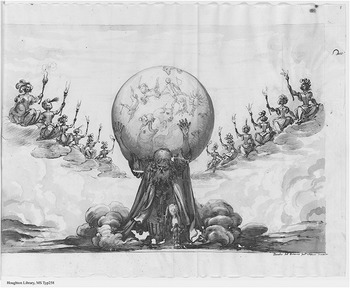

The first attempt to perform musical plays occurred in February 1645 at the Louvre. This was probably an allegorical play, staging the ties between France and Rome: the ‘dramma per musica’ Il Giudizio della ragione tra la Beltà e l’Affetto (Buti, Marazzoli or Marco dell’Arpa; Rome, 1643).19 Complemented with ballets by Giambattista Balbi, La Finta pazza (Giulio Strozzi, Francesco Sacrati; Venice, 1641) was performed a few times in December 1645 at the Petit-Bourbon in the presence of the queen regent and the young Louis XIV, with machines and stage sets by Giacomo Torelli, who had been sent expressly to Paris by his patron, the Duke of Parma.20 According to a contemporary review from the Gazette de France, the audience was as much dazzled by the music and poetry as by Torelli’s décors, his machines, and ‘admirable changes of scenery, so far unknown in France’.21

In February 1646 at the Palais-Royal, several performances were given of the opera Egisto, ovvero, Chi soffre speri (1637), originally written for the Barberini theatre in Rome on a libretto by Giulio Rospigliosi (1600–1669) with music by Virgilio Mazzocchi (1597–1646) and Marazzoli.22 An Italian traveller, Giambattista Barducci, noted the success which greeted the Italian ‘manner of singing’.23 But, apart from this, the concert version did not meet with much enthusiasm: on Fat Tuesday (13 February 1646), ‘only the King, the Queen, the cardinal [Mazarin], and the inner circle of the Court’ attended. In her memoirs, Françoise de Motteville, the première femme de chambre of Anne of Austria (Louis XIV’s mother) lamented the fact that ‘we were only twenty or thirty people in this place, and we thought that we would die of boredom and cold there. Entertainments of this sort require company, and solitude isn’t in keeping with the theater.’24 Such reactions may have discouraged performances of Monteverdi’s L’Incoronazione di Poppea (Venice, 1643) that had been planned ‘only with beautiful costumes’.25 But Mazarin prepared a brilliant première: in June 1646, he brought Rossi, the Roman composer in the service of the Barberinis, to Paris. The machinery of the Palais-Royal was renovated with the help of the French painter and architect Charles Errard in order to accommodate Torelli’s stage settings. Beginning on 2 March 1647, Rossi’s opera Orfeo (Buti) was performed eight times as Le Mariage d’Orphée et d’Euridice, tragi-comédie en musique et vers italiens, avec changement de théâtre et autres inventions jusqu’alors inconnus en France, with machines by Torelli and ballets by Balbi – the music of which was mostly composed by French court musicians.26

Once again, the queen regent and Louis XIV attended these performances. The Gazette de France praises the décors and machines, notably those of Apollo, noting that the spectators did not know ‘what to admire most’ between ‘the variety of scenes, the diverse ornaments of the theater, and the novelty of the machines’, or ‘the grace and the voice of those who recited’.27 The expressive quality of the music remained nevertheless the main object of admiration. While pointing out that a part of the audience was bored due to their ignorance of the Italian language, a reviewer from the Gazette de France stresses that the music ‘could express no less than the verses all the affects of those who did recite these’.28 Nevertheless, this lavish Orfeo became the target of attacks by the Frondeurs against Mazarin.

Triumph of the Machine

Private companies followed this vogue for the spectacular. Considered since 1644 the most beautiful public theatre in Paris, the Théâtre du Marais reopened in 1647; it accommodated theatrical machines designed by Georges Buffequin and staged monumental plays with musical accompaniment. At around the same time, in 1648, Mazarin commissioned Corneille and Charles Coypeau d’Assoucy (1605–1679), the former lute master of Louis XIII, to create a mythological tragedy mixed with music that could reuse the machines from Rossi’s Orfeo. Andromède was finally premièred in February 1650 at the Petit-Bourbon, after some delay caused by the illness of the child king, then by the Fronde. Composed of four airs, a dialogue in music, and nine choruses, Andromède was favourably received and served to strengthen the association between music, machines, and mythology. Thus, opera made its way into the French public through the importation of Italian décors and the insertion of ballets in the French manner, as in Caproli’s Le Nozze di Peleo e di Theti featuring Torelli’s machines. Some French singers appeared for the first time among a cohort dominated by their Italian peers.

This period saw the French monarchy reaffirming its authority: the victory over the Fronde was followed in 1659 by the signing of the Treaty of the Pyrénées. The termination of the long war between France and Spain (1635–1659) culminated in a reconciliatory gesture, the wedding of Louis XIV and the Infanta Maria Theresa of Spain. Festivities lasted for three years: Italian opera was prominently featured. Francesco Cavalli, who travelled from Venice to Paris in the spring of 1660, was commissioned to compose an opera for the occasion, adapted to the greatest indoor theatre ever constructed in France, the salle des machines at the Tuileries, commissioned in 1659 to Gaspare Vigarani, who was employed by the Duke of Modena. As the construction was still in progress, a new performance of Cavalli’s Xerse (Venice, 1655) took place in November 1660 with six ‘entrées de ballet’ set to music by Lully. The young violinist, who had been admitted as musician to the court in 1652, quickly became extremely popular, first as a dancer and then as a comic pantomime in his own ballets, which featured operatic dialogues (sung by the company of Italian singers) in combination with French récits (L’Amor malato, 1657; Ballet royal de l’Impatience, 1661). Lully staged a competition between the two styles in his Ballet de la Raillerie (1659).

Finally completed after the Fronde, Mazarin’s new theatre was inaugurated on 7 February 1662, after his death in March 1661. Cavalli’s opera Ercole amante (Buti) was premièred there, augmented with eighteen entrées de ballet composed by Lully, in which members of the court and the royal family participated. The cast comprised two French singers, Hilaire Dupuis and Anne de la Barre, and an Italian company led by Bergerotti. The audience was impressed by the imposing size of the décors: the Gazette de France noted that the machine in the final scene could carry ‘as many men as the Trojan horse’.29 Italian guests were more critical. Barducci praised the ballet, the magnificent décors, the costumes, and the machines, but he lamented that the music, which should have been the main ‘reason for the celebration, is entirely lost in the middle of the racket’ caused by the greater part of the audience, who did not understand the libretto.30 The Venetian ambassador, Giovanni Grimani, attributed this failure to the theatre’s poor acoustics.31

The Franco-Italian experiment of Ercole amante was abandoned, but the influence of using such vast frescoes in combination with machines remained paramount for the inception of a specifically French form oriented towards the spectacular. Yet the issue of language remained to be addressed, since the majority of French audiences did not understand Italian. This explains the parallel development of the pastorale en musique, a work not only of much smaller proportions but also one that offered the possibility for conveying the passions of the libretto with a typically French musical language.

Return to the Pastorale en Musique

Such smaller dramatic works sung throughout appeared from the middle of the century: the pastoral comedy Les Charmes de Félicie, tirés de la Diane de Montemayor (Jacques Pousset de Montauban, Cambefort; Hôtel de Bourgogne, 1654) and Le Triomphe de l’Amour sur des bergers et bergères, a pastorale in one act (Charles Beys, Michel de la Guerre, music lost; concert version performed on 21 January 1655; slightly revised staged version on 26 March 1657). In his preface to the pastorale La Muette ingratte (concert version, 1658–1659), Cambert referred to his desire to ‘introduc[e] plays in music as has been done in Italy’:

I began in 1658 to compose an elegy for three different voices in a type of dialogue, as are heard in concerts, and this elegy is entitled La Muette ingratte. M. Perrin, having heard this piece which was successful and did not become tiresome – even though it lasted, with symphonies and solos, a good three-quarters of an hour – became inspired to compose a little pastoral.32

Cambert and Perrin collaborated again with the Pastorale d’Issy (music lost), which premièred in early April 1659 in a private context and was subsequently given, with success, at the court. According to Ménestrier, the work was an attempt to introduce more recitative into French music and render it ‘capable of expressing the most pathetic feelings without losing any of its words’.33 Going back stylistically to earlier court divertissements, if not to narrative models from the beginning of the century, these works failed to rival the tragedies that had been blossoming on the Parisian stage for more than twenty years. Perrin decided to set to music a serious play, La Mort d’Adonis (Antoine Boësset, music lost), which was performed at the ‘petit coucher’ of the king in 1661. This, as well as a comic play – Ariane ou le mariage de Bacchus (Cambert, rehearsed in public, music lost) – met Perrin’s main purpose, which was to prove that ‘it is possible to succeed in all dramatic genres’.34

Comédies Mêlées

Today referred to as comédies-ballets, comédies mêlées (mixed comedies), which featured songs or musical and danced intermèdes that had been first performed at the court and then in Parisian theatres, began to be incorporated into pastoral plays. Considered the first comédie-ballet, Les Fâcheux (Molière, Pierre Beauchamps; July 1661) was given as part of a lavish series of celebrations in honour of Louis XIV organised by Nicolas Fouquet, the Surintendant of Finances, in his own residence, the castle of Vaux-le-Vicomte. Since the dancers had to change their costumes between the different entrées, Molière decided to insert comic scenes within the danced divertissement. In public theatres, the practice of mixing spoken scenes and musical or danced sequences had started to gain momentum, with an increasing number of plays integrating musical scenes. For instance, Le Bourgeois gentilhomme, a comédie-ballet by Molière and Lully first performed at the court in October 1670 and then at the Palais-Royal in November, is a comic play that incorporates intermèdes, the most celebrated of which are ‘La cérémonie turque’ (The Turkish Ceremony), conceived and performed by Lully himself in the manner of his own ballets, and ‘Le Ballet des Nations’, which evokes different European countries and was inspired by the Ballet royal de Flore (Lully, 1669).

The Turning Point: 1671

By the end of the 1660s, the various options available for musical performance, whether at the court or in the city, were ready to converge and fully realise the union of ballet, court entertainment, and plays with machines. Commissioned for the reopening of the salle des machines at the Tuileries Palace, Psyché, a tragedy in vers mêlés (poetry composed of lines featuring different metres) with five musical and danced divertissements, premièred on 17 January 1671. Conceived by Molière, partly versified by Corneille and Quinault (the latter for the sung parts), and choreographed by Beauchamps, Psyché was inspired by Andromède. Its mythological subject justified the use of machines, exemplifying the monumental proportions assumed by the divertissement during Louis XIV’s reign – nevertheless, spectators were particularly sensitive to the suffering of a young girl confronted by the gods’ wrath.

Among Psyché’s highlights, ‘La plainte italienne’ – a scene imitating the Italian lamento – and the final scene – a wedding celebration in the heavens – incorporate both the opulent old tradition of the Florentine divertissement and the French ballet de cour. In a letter relating the event, the Marquis of Saint-Maurice, ambassador of the court of Savoy, counted no less than seventy ‘maîtres à danser’ and more than three hundred violinists, ‘all lavishly dressed’, the singers and musicians suspended by machines, and producing ‘the most beautiful symphony in the world, with violins, theorbos, lutes, harpsichords, oboes, flutes, trumpets and cymbals’.35

In the meantime, a royal privilege dated 28 June 1669 granted to Perrin the authorisation to establish ‘Royal Academies of Opera, or representations in music in French, on the model of those from Italy’. On 3 March 1671, Pomone, his pastorale in five acts, was performed in Paris (Jeu de Paume de la Bouteille; the music by Cambert is mainly lost, except for the overture, Act I, and part of Act II). Presented as an ‘opera or representation in music’, it featured machines built by the Marquis of Sourdéac (who became, later in December, one of the business managers of Perrin’s Académies d’Opéra, with the financier Laurent Bersac, Sieur de Champeron). Entirely sung, its half-pastoral, half-mythological plot narrates in a rather comic vein the loves of Vertumne, the god of the seasons, and Pomone, the goddess of fruitful abundance. Pomone was performed continually over the course of seven to eight months (146 performances), making this work the greatest triumph of its century.

Like Psyché, Pomone offered all the necessary ingredients for the tragédie en musique. It was performed on the Parisian stage at considerable expense, financed by individuals but under the strict control of the royal authority; fully sung and in five acts, it featured dances and machines – the opulence of which recalled the court divertissement – and a prologue praising the king as the protector of the ‘Académie Royale des Opéras’. 36 Nevertheless, the libretto, obviously comic, was generally considered weak and ridiculous, comparing unfavourably with Lullian opera, which, with the help of the librettist Quinault, tended more toward the dignity of Psyché.

In the wake of Pomone’s success, Molière’s company invested generously in a series of new performances of Psyché at his own theatre, the Palais-Royal. The machines were repaired and readjusted for new effects; new musicians, dancers, singers, and acrobats were hired. The intention was clearly to attain a pomp comparable to that of court performances, but also to reaffirm the prestige of the comédies mêlées in response to the triumph of opera. Molière’s attempt was successful, as is shown by the public reception of these new performances of Psyché, as would later be the case for the comedy Le Malade Imaginaire (Molière, 1673), the mythological tragedy Circé (Thomas Corneille, 1675), and, in 1682, Pierre Corneille’s Andromède – all three plays with scores composed by Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643–1704).37 This success can also explain the aggressiveness with which Lully, as leader of the Académie Royale de Musique, defended his privileges against other Parisian stages.

Lully and the New Académie Royale de Musique

Lully arrived in Paris in 1646 as Giambattista Lulli. In 1653, he became composer of the king’s instrumental music. He succeeded Cambefort in 1661 as ‘Surintendant de musique et compositeur de la musique de chambre du Roi’. From his first ballet de cour, Le Ballet du temps (Benserade, 1654), through Psyché, Lully gradually established his control over the royal divertissements. Begun in 1664, Molière and Lully’s fruitful teamwork (Le Mariage forcé) lasted until 1671: the causes of their rupture were the success of Psyché and, above all, Molière’s decision to restage the work, most likely without Lully’s permission. In addition, the success of Pomone led the king to encourage other composers: in November 1671, Les Amours de Diane et d’Endymion (Henry Guichard) on a score by Jean Granoulhiet (Grenouillet) de la Sablières (1627–c. 1700) was performed in Versailles, then repeated with ballets in February 1672 at Fontainebleau with the title Le Triomphe de l’Amour.38 In Paris, Sourdéac and Champeron presented another pastorale, Les Peines et les Plaisirs de l’Amour (Gabriel Gilbert, Cambert). Hoping to maintain control over virtually every musical production given on Parisian stages, Lully bought Perrin’s privilege and received a new patent in March 1672 from the king, which gave a quasi-monopoly to the brand-new Académie Royale de Musique. The Académie could from then on exercise complete control over the amount of music in any given performance as well as the number of musicians. For instance, shortly after the première of Molière’s Le Malade imaginaire, Lully stipulated on 30 April 1673 that the orchestra, which had already been dramatically reduced, would number no more than two singers and six violinists – the usual configuration for musical entr’actes in spoken theatre. Protests from other theatres helped to loosen some of these rigid rules, but the Académie kept the privilege for performances that were entirely sung. After Lully’s death, the privilege authorised his successors to trade with private managers willing to open opera houses in the provinces: Lyons in 1687; Rouen in 1688; Aix-en Provence, Marseilles, and Montpellier in 1689; cities in Brittany, Bordeaux, and Toulouse in 1690; Toul, Metz, and Verdun, and other cities in the French Lorraine in 1699.39

The very first première at the Académie Royale de Musique was Quinault and Lully’s Cadmus et Hermione, a tragédie en musique on a mythological plot based on Ovid (Jeu de paume de Béquet, 27 April 1673). It was received with great success, and the king attended the performance. Following Molière’s death in February 1673, Lully was granted royal permission to move the opera house to the Palais-Royal, a venue which had up to that point been occupied by Molière’s company and the Italian comedians. The Palais-Royal could accommodate up to 1300 persons, out of which 700 could be seated in the loges. Although Lully seemed to have wanted at the beginning of his tenure at the Académie to attract a wide audience, the price of admission remained in general much higher than that for spoken theatre.40

After Cadmus and the exceptional performance of Alceste at Versailles on 4 July 1674 (see Figure 8.4), almost all of Lully’s operas were first performed at the court in Saint-Germain-en-Laye.41 The king financed the décors and rehearsals, as well as the exceptional honoraria for his protégé, who usually composed one opera per year, in January, at the beginning of the carnival season: Alceste, ou le Triomphe d’Alcide (1674), Thésée (1675), Atys (1676), Isis (1677), Proserpine (1680), Persée (1682), Phaëton (1683), Amadis (1684), and Roland (1685) were all composed on Quinault’s libretti. Lully also wrote two operas on libretti by Thomas Corneille and Bernard Le Bouyer de Fontenelle: Psyché in 1678 – the score of which reuses the intermèdes Lully had composed for Molière’s Psyché in 1671 – and, in 1679, Bellérophon.

Lully’s masterwork, Armide (Quinault, 1686), was received with unprecedented enthusiasm even though it was not performed at court due to the king’s developing disinterest in opera. A contemporary spectator described the theatre as filled over its maximum capacity and ‘so profusely overcrowded that one could not understand the quantity of people who attended’.42 In the title-role, Marthe Le Rochois eclipsed all the other actresses of the Académie Royale. Her imprint on the role lasted until the second half of the eighteenth century, especially in the most celebrated scene, Armide’s monologue, ‘Enfin, il est en ma puissance’ (Act V scene 2):

In what rapture weren’t we … to see her, dagger in hand, ready to pierce the heart of Renaud, asleep on a bed of grass! Fury animated her; love had just seized her heart; both agitated her alternately; pity and tenderness succeeded them in the end; and love remained victorious. Such beautiful and truthful attitudes! How many different movements and expressions in her eyes and her face, during this monologue.43

This long soliloquy offered singers the possibility of showcasing their vocal and acting talents, and expressing theatrical passions. Until the eighteenth century, Armide’s monologue remained the most emblematic piece in the operatic French repertoire.

Following Lully’s death in March 1687, his son-in-law Jean-Nicolas de Francine (1662–1735) became the director of the Académie Royale de Musique until 1704. In 1714, the Académie required that all of Lully’s operas be inscribed in the repertoire of the theatre. The predominance of Lully’s works had already cast a considerable shadow over those of other composers. David et Jonathas, Charpentier’s first tragédie en musique, was performed in 1688 at the Jesuit college Louis-le-Grand: its acts were performed as intermèdes for a Latin tragedy, Saul (François de Paule Bretonneau). Yet Charpentier would have to wait until after Lully’s death for his opera Médée (Thomas Corneille, 1693) to be brought to the stage of the Académie Royale de Musique. Judged exceedingly difficult, it was poorly received.44 The composer Henri Desmarets (1661–1741) had more success the same year with Didon (Louise-Geneviève Gillot de Saintonge).45

Francine was able to rely on the works of other composers: Lully’s secretary Pascal Collasse (1649–1709) composed the successful Thétis et Pélée (Fontenelle, 1689), which would then be performed over the course of seventy-six years at the Académie Royale. Another major success was Alcyone (Antoine Houdar de Lamotte, 1706) by Marin Marais (1656–1728). Himself a musician of the orchestra of the Académie, Marais solidified the Lullian legacy in Paris before the arrival of a second generation of composers whose works had first been noticed at the court. Such was the case for André Cardinal Destouches (1679–1742) and André Campra (1660–1741), who enjoyed their first successes with ballets and opéras-ballets.46 Nevertheless, the genre that continued to bring artistic recognition was the tragédie en musique.

Tragédie en Musique

Lully’s favourite librettist, Philippe Quinault (1635–1688), was renowned not only as a librettist but also as a playwright – he authored several spoken tragedies and plays in a lighter vein.47 His double competence served French opera well. The product of a synthesis between diverse forms of court entertainments, it adopted as its referential frame the paradigmatic genre of tragedy.48

A paramount requirement of French classical aesthetics was to adapt the theatrical representation to the concepts of vraisemblance (verisimilitude) and bienséance (decorum, implying a general sense of suitability and plausibility).49 The fictional plot must adequately observe moral standards and answer to the cultural expectations of the audience. Yet music poses a major problem with regard to verisimilitude, as it creates a distance between the object and its imitation – an issue that was also discussed in Italian opera. The recourse to themes defined as galant and merveilleux (marvellous), encompassing mythological and supernatural worlds and beings, helped to reduce this distance.

Machines were justified by the presence of supernatural characters and their otherworldly powers, increasing the theatrical illusion – thus, magicians and gods fill the universe of the tragédie en musique.50 As Charles Perrault put it, tragédie en musique is justified because it belongs to an ‘opposed species’ to comedy, which ‘only accepts the vraisemblable [verisimilitude]’. On the other hand, tragédie en musique can accommodate ‘extraordinary and supernatural events, and this is what operas and plays with machines are about, while the tragedy stands in the middle, mixing the marvellous with the vraisemblable’.51

Other commentators pointed to the issue of characters who sing instead of speak. Saint-Evremond criticised the prosaism of specific scenes: for instance, a master asking his valet to run errands, dictating military orders through song, singing while ‘killing by sword and spear’, and so forth.52 Opera should solve this difficulty by adopting mostly ‘gallant’ subjects. Saint-Evremond’s argument is that some passions and actions are better rendered through song than others, as they harm neither the bienséance nor the reason: ‘tender and painful passions are naturally expressed through some sort of song’.53 Thus one must exclude ‘cold’ passions such as ambition or political reasoning. Pierre Perrin criticised Italian operas for being exceedingly narrative, lacking in passion and lyricism – thus the widespread French criticism of Italian operas based on historical figures such as Nero or Alexander the Great. These characters were deemed generally ‘unfit to song’: these operas are rather ‘recited comedies’ characterised by ‘lengthy intrigues, cold and serious reasonings, as they would happen in a spoken play’.54 As late as 1741, Mably declared that tragic heroes, usually cold and sententious with their ‘feelings often locked deep down in their heart’, are unfit as operatic characters.55 All is then better in the marvellous universe of French opera: its characters, because completely imaginary, are also more apt to express themselves through song.

The relatively late surge of opera in France can be explained by a general distrust of the efficacy of music for conveying dramatic interactions and by issues surrounding the intelligibility – or absence thereof – of sung lyrics. With his deep knowledge of court tastes, Lully was perfectly aware of the expectations of French audiences in terms of vocal style. Psyché was not entirely sung, while Pomone presented a succession of airs: the invention of French opera had to wait for Lully’s achievement, in which musical scenes would be coordinated with the help of the recitative. By offering a vocal style that could render all the nuances of affect, whether in monologues or dialogues, Lullian recitative became the most remarkable response to these constraints.56

Tragédies en musique were built on a hybrid succession of musical sequences: recitative scenes;57 ‘airs sérieux’ or ‘petits airs’ – that is, short lyrical airs intertwined within scenes; longer récits for soliloquies imitated from spoken theatre that often privilege the narration of hallucinations, dreams, or laments;58 and symphonies – that is, instrumental pieces, often with a descriptive purpose. The ‘chansons’ – dances and choruses inspired by the former tradition of comédies mêlées, and usually the most alien to the dramatic fabric – were gathered within scenes to provide poetic coherence. These scenes were used to represent ceremonies (religious rituals, weddings, sacrifices); popular or pastoral celebrations, including supernatural manifestations of otherworldly creatures; magical rites; infernal demons; allegorical representations of passions; and so on – in short, any type of situation in which music is diegetically or aesthetically justified.59

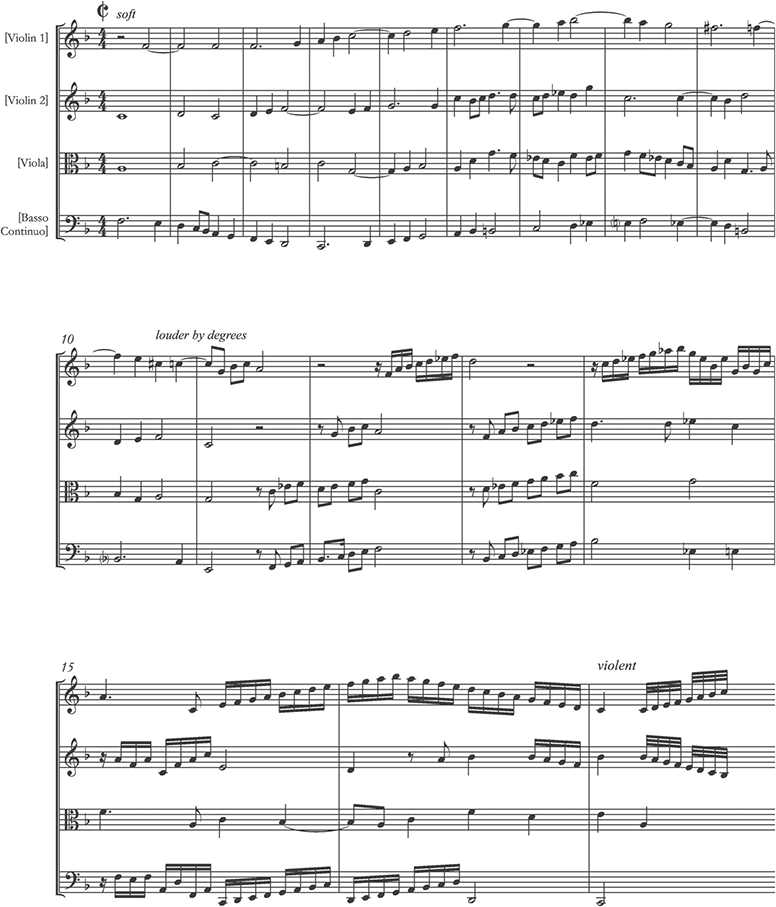

The spectacular dimensions of the tragédie en musique reveal its princely origins. Furetière’s Dictionnaire universel (1690) defines opera as a ‘public spectacle, a magnificently staged representation of some dramatic work, the verses of which are sung and are accompanied by a great symphony, dances, ballets with costumes, lavish decors and surprising machines’.60 Alongside dances and choruses, the presence of machines first required musical preludes, then descriptive symphonies: for instance, the evocation of spectres in Lully’s Amadis, the unleashing of demons in Charpentier’s Médée, the tempests in Collasse’s Thétis et Pélée, and Marin Marais’ Alcyone.61

While Lully enjoyed mixing comic characters with pathetic heroes, the comic became increasingly proscribed in the tragédie en musique. By the end of the seventeenth century, the genre had become perfectly well defined, its dramaturgy remarkably stable until the last decades of the eighteenth century.

A ‘Ballet Moderne’

By the end of the 1680s, as Louis XIV was losing interest in the tragédie en musique, his son, Louis de Bourbon, the Grand Dauphin (1661–1711), became the new arbiter of taste at the court.62 This led to the return of older forms of entertainment: in 1681, for the Grand Dauphin’s wedding, the ballet de cour Le triomphe de l’amour was performed in Saint-Germain-en-Laye. In 1685, the prince commissioned a ballet from Lully, Le Temple de la Paix (Quinault; Fontainebleau), and, in the following year, the pastorale Acis et Galatée (Jean Galbert de Campistron; Château d’Anet). Court residences began to offer representations of ‘petits opéras’ (small operas), works of smaller dimensions, often on a pastoral theme.63 Such works met with great success in Paris, including Issé, a pastorale héroïque in three acts (Antoine Houdar de La Motte and Destouches; Fontainebleau, 1697), which was presented in the capital in 1708.

These shifts also explain the necessity to better define the genre of tragédie en musique at a time when the Académie Royale de Musique was struggling with recurrent financial issues. This led the institution to rationalise its offerings: on the one hand, tragedies reinforcing the spectacular and the pathetic, especially at the beginning of the eighteenth century, and, on the other, the development of a new genre, the modern ballet, today referred to as opéra-ballet. Intended to alternate with tragédies en musique and to fill the slower summer season, the opéra-ballet favoured lighter themes. It also attempted to bring to the Parisian stage the distinctive spirit of courtly festivities.

In 1695, the ballet in three acts Les Amours de Momus (Duché de Vancy, Desmarets) paved the way to comedies in music, such as Le Carnaval et la Folie (La Motte, Destouches, 1703). Similarly, separated acts or ballet entrées, each focused on an independent plot, could be connected through a common theme that had been previously developed in the prologue. This strategy was profitable to the permanent company of singers and dancers: they could fully showcase their talents while offering Parisian audiences a wider range of musical styles.64 Prime instances of these opéra-ballets are Les Saisons (Jean Pic, Collasse, 1695), which was followed by the triumph of L’Europe galante (La Motte, Campra, 1697). In 1754, Louis de Cahusac gave a well-known definition of the genre in which the hierarchy between action and divertissement seems reversed: compared to the five acts of the tragédie en musique, ‘a vast composition, as those by Raphael and Michelangelo’, opéras-ballets feature ‘several different acts, each representing a single action mixed with divertissements, song and dance. These are pretty Watteaus, witty miniatures that require all the precision of the design, the graces of the brushstroke, and the whole brilliance of the color.’65

This taste for lightness goes hand in hand with the revival of the Italian influence, now present inside and outside the court, from the entourage of the Grand Dauphin to Italophile circles in Paris.66 Several Italian composers were settled in Paris at that time: Paolo Lorenzani (1640–1713) beginning in 1678; Theobaldo di Gatti (c. 1650–1727) beginning in c. 1675; and later, around 1705, Jean-Baptiste Stuck [Stück] (Battistin, or Batistin, 1680–1755). Lorenzani received two commissions: the pastorale Nicandro e Fileno (Fontainebleau, 1681) followed by an opera in the Venetian style, Orontée (Chantilly, 1688), modelled after Cesti’s Orontea (1649). Fashionable divertissements granted a substantial space to an Italian imaginary world, as in Campra’s L’Europe galante: one of its acts, entitled ‘L’Italie’, brings Italian music to the stage of the Académie Royale. Campra’s subsequent works, Le Carnaval de Venise (Jean-François Regnard, 1699) and Les Fêtes vénitiennes (Antoine Danchet, 1710), evoke the famous entertainments of the Republic.67 The Italian style is primarily noticeable in the vocal writing, allowing for the increased virtuosity that would soon launch the swift success of the French cantata.68

This Italian vogue explains the controversy provoked by the publication in 1702 of François Raguenet’s text, Parallèle des Italiens et des Français en ce qui regarde la musique et les opéras. Essentially praising Italian music and its musicians, this argument motivated Jean-Laurent Le Cerf de Viéville to publish his Comparaison de la musique italienne et de la musique française (1704), a text considered to be the first to discuss the ‘goût français’ in music, defining the tragédie en musique versus Italian opera and its aesthetic impact on contemporary audiences.69

Beginnings of the Opéra-comique

The comic musical style had been traditionally associated with Italian culture since the end of the sixteenth century. It gained ground at the beginning of the eighteenth century at the Académie Royale de Musique as well as on other stages, affecting the specialisation of theatres that had been carefully decreed by the king at the end of the seventeenth century. In 1680, the reunion of the spoken theatre companies gave birth to the Comédie-Française, which continued to perform comedies featuring divertissements with musical scores composed from 1692–1693 by Nicolas Racot de Grandval (1676–1753) and Jean-Claude Gillier (1667–1737).70 On the other hand, the Comédie-Italienne granted a larger place to music: two-thirds of the plays, including the canevas plays printed in the anthology Le Théâtre italien first published in 1694 by Evariste Gherardi, contain sung airs – serenades, burlesque ceremonies, drinking songs, masquerades, and so forth.71

Following the creation of the Académie Royale de Musique, competition between the different theatres increased: it would lead at the beginning of the eighteenth century to a real war between the different stages. A much favoured tactic was to ridicule the taste for opera. Saint-Évremond’s Les Opéras (around 1676) portrays a young mad girl only able to express herself through song: the theme reappears in the first original play to be staged at the Comédie-Française, Les Fous divertissants (Raymond Poisson, 1680), in which passages from Lully’s tragédies en musique Proserpine and Bellérophon are quoted. Dancourt satirises victims of the opera craze in Angélique et Médor (1685) and in Renaud et Armide (1686). These latter three plays have a score by Charpentier.72

While these practices were a blow to the Lullian hegemony, they also took advantage of the popularity of his works.73 The Comédie-Italienne transposes the intrigues into a lighter setting by presenting comic characters dealing with trivial matters. They sing tragic laments on original music (by Angelo Constantini, known as Mezzetin), but also ‘vaudevilles’ – that is, well-known tunes or famous operatic airs, the lyrics of which are altered following the example of the canevas.74 L’Opéra de campagne by poet and musician Charles Rivière Dufresny transports Quinault’s and Lully’s Armide to a rustic farm: Renaud’s air ‘Plus j’observe ces lieux’ (Act II scene 3), in which he is lulled to sleep, is parodied by Arlequin, who sings in praise of a roasting spit.

Eventually, such practices led to full-blown parodies that tweaked the plots of tragédies en musique staged at the Académie Royale de Musique, and, in so doing, opened the path to the genre of the opéra-comique.75 Following the expulsion of Italian actors from Paris in 1697, the Parisian fairs (the Foire Saint-Laurent and the Foire Saint-Germain) attempted to take their place. The Académie Royale responded by banning the use of song in works performed at such fair theatres; similarly, the Comédie-Française forbade them to use speech. The fair theatres were obliged to come up with imaginative alternatives to compensate for the loss of spoken and sung dialogues: they required that the audience sing well-known operatic airs (‘timbres’) and vaudevilles.76 This type of interaction between the public and the actors was itself viewed as desirable by the Académie Royale, since its audience enjoyed singing along with the actors, especially during the divertissements. Attending a performance of Campra’s L’Europe galante in 1698, the English physician Martin Lister could thus marvel at the large audience and at the ‘great numbers of the nobility that come daily to [the operas], and some that can sing them all’.77 This in turn explained the enduring success of the fair theatres where this practice continued, even after they had regained the right to use song and speech.

Eventually, after strenuous negotiations between the Académie Royale and the fair theatres, two directors of the latter, Charles Alard and the widow Maurice (Jeanne Godefroy), obtained in 1709 the authorisation to hire singers and dancers, and to change the décors, the sole condition being that they would not present plays with continuous musical accompaniment.78 The convention signed later in December 1714 marked the birth of the opéra-comique, perpetuating in its own terms the legacy and specificities of the French tragédie en musique.

Translated from the French by Jacqueline Waeber and Laura Williams

The French versus Italian Problem

In his Memoirs, the Italian playwright Carlo Goldoni describes the performance of a French opera he attended in Paris at the Académie Royale de Musique in 1763. There is much to admire in this unnamed work, from the technical ability of the dancers to the sumptuous décors, machines, and costumes. But soon, all this spectacle wears him out:

I patiently waited for the airs, in the expectation that I should at least be amused with the music. The dancers made their appearance, and I imagined the act finished, but heard not a single air. I spoke of this to my neighbor, who laughed at me, and assured me that we had had six in the different scenes which I had heard. “What!” said I, “I am not deaf; the instruments never ceased accompanying the voices, sometimes more loudly, and sometimes more slowly than usual, but I took the whole for recitative … Everything was beautiful, everything was grand, everything was magnificent, except for the music … It is a paradise for the eyes, and a hell for the ears.1

This passage has often been quoted to pinpoint the strangeness of French opera, even its absurdity, at least when judged alongside the expectations of eighteenth-century audiences to whom opera seria provided the normative model. At the time of Goldoni’s description, the tragédie en musique had been weakened by the vogue for opéra-comique and by the absence of a leading composer: Rameau had died in 1764, and his most recent tragédie en musique, Zoroastre, had been premièred in 1749.2

Goldoni perceived French opera primarily as a visual spectacle – the privileged place of ballet and the use of machines had been an essential feature of the tragédie en musique since its inception. His description sheds light on the clichés attached to French opera that had existed since the time of Lully. Goldoni’s argument implies that the French conception of song is problematic, at least for Italian(ate) ears. That Goldoni refers to the French vocal style as nothing other than ‘récitatif’ was not an isolated claim at that time. Discussions about the relevant merits and flaws of French and Italian vocal styles had been going on since the birth of opera in France. These had culminated with the Querelle des Bouffons (end 1752–1754) and were provoked when the Académie Royale de Musique invited Felice Bambini’s Italian company to perform a series of intermezzi comici, among which was Pergolesi’s La Serva padrona.3

The confrontation on the Parisian stage between the tragédie en musique and the repertoire of Italian comic opera triggered the polemical discussions of the Querelle, but this was also much more than the collision of two antagonistic conceptions of vocality as exhibited by French and Italian opera. The Querelle was the culmination of tensions that had accompanied the tragédie en musique since its inception, including the question of its attachment to the tradition of French tragédie classique, the spoken classical tragedy. Moreover, the Querelle led to radical reconsiderations regarding the musicality of French versus Italian – a debate that had been brewing throughout the seventeenth century, well before the publication of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Lettre sur la musique française in November 1753.

Prior to the eighteenth century, the development of the tragédie en musique and other related dramatic genres, such as the opéra-ballet, provided secure outlets for French musicians and their librettists. The absence of real competition with the Italian operatic model helped them promote and preserve their own style. Still, to speak of a complete French rejection of Italian music and its lyric style would be excessive. Since the early seventeenth century, the fashion of ‘Italianisme’ had been encouraged by the presence at the court of the Marquise de Rambouillet, who was of Roman origin, and the marriage of Henry IV of France with Maria de’ Medici in 1600.

Certainly, the French did not come naturally to opera, at least when we conflate the term ‘opera’ with the Italian dramma per musica. Understanding the complex history of the assimilation of Italian opera by the French stage cannot neglect the importance of non-musical factors, such as the political relationships between the kingdom of France and several powerful Italian states. Various attempts to graft the Italian operatic model on the French tradition of court entertainment ended with the advent of the tragédie en musique, which was inaugurated with Jean-Baptiste Lully and Philippe Quinault’s Cadmus et Hermione (1673), a genre intended more as a departure from the Italian opera than a reappropriation of it. After Lully’s death (1687) and throughout the eighteenth century (that is, until Gluck arrived in Paris in 1773), French opera continued to be contrasted with the Italian model. This was primarily due to the centralised system implemented through royal institutions that ruled the arts: it remained crucial for France, home to the second major operatic tradition in Europe, to preserve its own paradigmatic model.

The Persistence of the Tragédie Classique in the Tragédie en Musique

Other factors were paramount for explaining the physiognomy of French opera and its antithetical perception of Italian opera. Assessing the emergence of the French model for opera must first consider the ground on which this model originated: the classical tragedy, France’s most illustrious theatrical tradition. The tragédie en musique was organically tied to theoretical and aesthetic conceptions that defined the genre of spoken tragedy, itself a reaction against the dramatic excesses of the sixteenth-century humanist tragedy. The blossoming of French tragedy was encouraged by improvements to Parisian theatrical locations – such as the reopening in 1644 of the renovated Théâtre du Marais – which better equipped them for the display of spectacular stage settings and machines. Another crucial factor was the emergence of a new generation of playwrights, among whom were the genre’s two most prominent figures, Pierre Corneille (1606–1684) and Jean Racine (1639–1699).

French classical tragedy is defined by a series of paradigmatic features: division into five acts and a plot taken from Classical antiquity – be it history or mythology, as shown in Racine’s plays – or from ancient or early history (for instance, Corneille’s Le Cid). The genre also excluded lowly characters, privileging instead aristocratic, regal figures. This can be understood as an extension of the rule of bienséance (decorum), which prohibited the representation on stage of actions involving physical violence or death. Moreover, anything tending towards an excessive eroticisation of the body or any other physical activity that would have been deemed trivial was banned.

All these aspects transited easily from spoken tragedy to tragédie en musique. However, the crux of the problem originated with the adjunction of music and its entanglement in the requirements of the art of declamation expected for the performance of spoken tragedy. ‘Musicalising’ or not the spoken model of tragedy had been a consubstantial debate in the history of French opera since its inception. At the end of the seventeenth century, the tragédie en musique was a prominent topic among the debates propelled by the Querelle des Anciens et des Modernes. The writer Charles Perrault keenly defended the new genre of French opera, demonstrating its validity against the arguments in favour of the Ancients in his Critique de l’opéra, ou Examen de la tragédie intitulée Alceste (1674). This opened an enduring tradition of controversies that traversed the entire eighteenth century—the Querelle des Lullistes et des Ramistes (ignited by Rameau’s first tragédie en musique, Hippolyte et Aricie, premièred in 1733), the Querelle des Bouffons, and the Querelle des Gluckistes et des Piccinnistes (1775–1779).

It would be a mistake to imply that the French resisted the novelty of opera because they were ‘less musical’ than Italians. The model of the tragédie en musique, a consequence of French misgivings regarding Italian opera, was embedded in a paradigmatic conception of lyric poetry. Thus theatrical declamation was perceived as being as musical as it was poetic. To summarise the arguments of French contemporary commentators opposed to opera, why would the French need tragedies set to music when their art of theatrical declamation was already musical?

The Reign of the Alexandrine

The French strongly believed in the musicality of their poetic language, which could be revealed by an adequate observation of accents, quantity, and rules of versification. As Claude Jamain puts it, ‘to bring back song to the spoken text had always been the natural inclination of [French] classicism’, an attitude viewed as antithetical to the vocalic sensibility of Italian opera.4

Lyric poetry of that period relied to a great extent on the alexandrin, or alexandrine verse. Popularised during the sixteenth century by the poets Pierre Ronsard and Joachim du Bellay, the alexandrine remained until the nineteenth century the main verse in French poetry. The alexandrine line consists of twelve syllables and is divided by two hemistichs of equal length, separated by a caesura falling after the sixth syllable. When ending on a masculine rhyme, that is to say, any syllable ending with a consonant (as in the words sommeil, fracas, vainqueur, soupir, etc.), the alexandrine counts exactly twelve syllables. When the ending rhyme is feminine, it counts twelve syllables, plus a final one, the mute “e” (as in heure, larmes, venge, soupire, etc.). Both alexandrine lines given here, from Armide’s famous monologue in Quinault’s tragédie en musique, Armide (Lully, 1686), respectively end with a masculine and a feminine rhyme:

In the first line, the caesura of the first hemistich is marked by the tonic accent on ‘ennemi’ and in the second on ‘frémis’. A defining prosodic feature of the classical alexandrine is to echo the caesura on the accented sixth syllable by the syllable of the final rhyme. To this can be added the possibility of other accents within each hemistich. For instance, in the line, ‘Achevons, je frémis; vengeons-nous, je soupire’, the natural rules of French prosody, aided by punctuation and, as indicated here, by the accent falling on the underlined syllables, tend to create within each hemistich an anapestic rhythm (BBL), a frequent one in the French language.

This tendency to create the repetition of rhythmic patterns, added to the length of the alexandrine line, encouraged a restrained declamation that was viewed as ideally suited to the solemn genre of tragedy. But the alexandrine was also frequent in comedies, as, for instance, in Molière’s plays Les Femmes savantes or Tartuffe. Indeed, the declamation of tragedy was defined by a ‘general tempo characterized by a certain slowness’,5 what Grimarest had already praised in 1707, stating that the proper use of the French language is to be spoken aloud ‘in a grave and noble manner’.6

These declamatory standards and their poetic style were maintained in the tragédie en musique. While a libretto may give less prominence to the alexandrine by mixing it more frequently with other lines, such as octosyllables and decasyllables, the musical setting also tends to enhance the slowness of prosody, at this tempo creating something akin to a magnifying glass effect. In his Réflexions critiques sur la poésie et la peinture (1719), Jean-Baptiste Dubos evoked the art of French opera singers as ‘the art of declamation proper for the realization of a recitation slowed down by song’.7

If theatrical declamation possessed an inherently musical quality, attempting to outline its rhythm and melodic inflexions through musical notation was the obvious task of the musician. By the end of the seventeenth century, the most emblematic example was the one provided by the actress Marie Champmeslé (1642–1698). As one contemporary commentator put it, ‘the delivery of the actors is a kind of song, and you would well admit that La Champmeslé would not please us so much, had her voice been less agreeable’.8 After La Champmeslé’s death, Le Cerf de la Viéville gave a slightly modified retelling of this anecdote in his Comparaison de la musique italienne, et de la musique françoise (1704), according to which Lully was said to have fashioned many of his recitatives on La Champmeslé’s declamation, an enduring tale that continued to be perpetuated well after the eighteenth century.9

What appeared to be a porous line between declamation and song was in France an ongoing issue made all the more significant by the rise of the tragédie en musique. But this trope originated before the late seventeenth century and culminated by the end of the sixteenth century with the experiments of the Pléiade, an academy founded in 1570 by the poet Jean Antoine de Baïf. Using the technique of vers mesurés à l’antique, Baïf attempted to recover the Greco-Latin poetic metre by following French rules of prosodic quantity.10 Baïf and his circle were influential among French composers of the early seventeenth century, who adopted the style of the musique mesurée à l’antique in which the melody must adhere as much as possible to the scansion of the verses. Understanding the style of musique mesurée is essential to understanding both the melodic style of the French air de cour – which would later be incorporated into ballets and tragédies en musique – and the characteristic style of French musical recitative.

The Air de Cour and the Italian Model of Monody

In seventeenth-century French vocal music, the most important genre was the air de cour, which developed by the end of the sixteenth century. The expression ‘air de cour’ appeared in 1571 in the first printed collection of these pieces, which indicates that the form was originally meant for the entertainment of the king and court. Aided by the large number of airs available in collections published by royal printers, it quickly gained popularity beyond those venues.

The air de cour could be either polyphonic (mostly four to five voices) or monodic with a lute accompaniment, as shown in the compositions of Pierre Guédron (1564–around 1619–1620). As its popularity grew, the air de cour made its way into the ballet de cour, where it often had an introductory function by appearing at the beginning of an entrée, usually in a monodic form with lute accompaniment. Guédron himself, as well as Antoine Boësset (1586–1643), composed several airs for these staged works: both composers had a major impact on the incorporation of the air de cour into the ballet de cour.

It would be tempting to view the air de cour as the French equivalent to the new genre of the monody, as heralded by Caccini’s Nuove Musiche (1602). Yet, the treatment of prosody and rhythm and the musical setting of the air de cour continued to be indebted to the French tradition of musique mesurée, with its musical accompaniment carefully supporting the standard accents and syllable counts. The vocal range, usually within one octave, tended to be much narrower than that of the Italian monody. Vocal ornamentation was also much less common, the emphasis being instead on the syllabic setting of the text.

The French did not judge the Italian monody by hearsay only: Caccini came to the French court in 1604 at the invitation of Henry IV. In comparing the two styles, contemporary commentators noted that French song appeared much more restrained than the Italian monody, a feature that could be construed as a flaw or, by those who disliked the excesses of the Italian manner, a quality. In his Harmonie universelle (1636), Marin Mersenne pondered the respective merits of French and Italian song: he described the Italians as ‘more vehement than us when it comes to expressing the strongest passions of anger with their accents, especially when they sing their verses on the theatre to imitate the staged music of the Ancients’.11

As shown by his correspondence with Caccini, Mersenne had a good knowledge of the Nuove Musiche and the Italian manner of ornamentation. He adopted a compromise position, since he was aware of the negative perception that French musicians had of the Italian penchant to embellish melody with extended melismas, ‘exclamations and accents’.12 French singers rejected this manner, as it smacked too much of the genres of tragedy and comedy. Mersenne offered that it would be entirely possible to find a middle ground by softening these Italian ‘excesses’ of ornamentation and adapting them to the idiosyncratic ‘French sweetness’.13

Mersenne also stressed the novelty of the Italian stile recitativo: he mentioned ‘Giacomo [sic] Peri’ as the one who ‘had started to introduce in 1600, in Florence, during the wedding of the Queen Mother, the manner of reciting Music verses on the theatre’.14 Mersenne’s description suggested the superiority of the Italians, at least when it came to their capacity for representing ‘as much as they can the passions and the affections of the soul and the mind, for instance, anger, fury, spite, rage, heartbreaks … with such an uncanny violence, that one thinks they are being affected by the very affections they represent through their song’. French singers, on the other hand, remained in a state of ‘perpetual sweetness’ that accomplished little else besides ‘flattering the ears’. More importantly, such sweetness lacked ‘energy’, which Mersenne used in the sense of enargeia, the rhetorical manner of offering listeners a description so vivid that they seem to experience it.15

For Mersenne these differences seemed more of degree than of kind: limited by its ‘sweet’ nature, French music was considered improper for the display of violent passions. Mersenne invited French musicians to unbridle their style – advice he may have gotten from his correspondence with Giovanni Battista Doni, who recommended that French musicians take ‘the opportunity to perfect [their musical style] and change it. … I am assured that if your princes would go to the expense, and time permitted it, this would succeed enormously.’16 A similar argument was offered by the French musician Pierre Maugars, who spent time in Rome during the 1620s and considered the manner of the Italian song ‘more animated, ornamented’ than that of the French, exhorting his countrymen to travel to Italy and free themselves of the rigidity of their rules.17

Yet the comparison between French and Italian was unfair, as it took place at a time before the French had devised their own operatic genre. Epitomised by the air de cour that originated outside the world of the stage, the French vocal style was not entirely comparable to the Italian monody nor to the stile recitativo motivated by the expression of passions consubstantial to the dramma per musica. To this must be added the weight of French tragedy, which provided a normative model not only for the dramaturgy of opera but also for the varieties of its vocal style of delivery as first shaped by Lully and Quinault.

French recitative was theoretically rooted in the theatrical and musical practices of the Ancients – another point of comparison with the Italian tradition. The argument was clearly articulated in Dubos’s influential treatise Réflexions critiques sur la poésie et la peinture. Originally published in 1719, Dubos’ text was augmented by a third part in the new edition of 1733. Entitled ‘Dissertation sur les représentations théâtrales des Anciens’, this new part scrutinises the conception of music and declamation among the Ancients. Dubos defines the art of declamation as primarily an art of melopeia, a Greek term referring to the art of composing the modulation, thus melody. If melody belongs as much to ‘music’ as it does to the oratory of the Ancients, one can push the syllogism further by affirming that this oratory is a sort of music. Of course, when reading Dubos today we should ask ourselves what the term ‘music’ meant to him and his contemporaries, for whom the minimal separation between music and declamation was being constantly renegotiated. Dubos warns his readers that the art of melopeia should not be considered ‘music’ (in its modern sense); the musical art of the Ancients should be viewed as the crafting of an instrumental accompaniment to sustain tragic declamation.

This is why Dubos argues that ‘the Ancients had a composed declamation that was written in notes, without being a musical song [chant musical]’.18 Granted, in several instances he describes this declamation as ‘musical’, implying a double meaning to the term. The beauty of melopeia or declamation, which can be described in musical terms, is a consequence of the poetic art. On the other hand, the beauty of music, as in the instrumental accompaniment to a tragic declamation, results from the principles of harmony.19

In any case, Dubos does not denigrate the art of declamation in comparison to the art of music: they were complementary in ancient tragedies. This is what he finds to have gone awry in modern operas, that is, those departing from the Lullian norm:

Let’s admit that we do not fully understand how music could ever be considered as being part of the tragedy, so to speak; if there is anything in the world that seems alien and contrary to a tragic action, it is song, which is, whether the inventors of tragédies en musique like it or not, poetry as ridiculous as it is new.… Because operas are, if I may say so, the grotesques of poetry.20

The French mistrust of Italian vocality lies essentially in the potential of the latter to supplant the virtues of French theatrical declamation, which they viewed as the most appropriate medium for the rendering of passions in their tragedies.

Experiencing the first Italian operas performed in Paris and at the court, the French perceived in Italian song a problematic mixture in which music appears as an added element to the text, endangering the primacy of the latter. Operatic vocality, for the French, should be a sublimation of declamation without ever becoming full song, and as such it runs the risk of detaching itself from its original textual substratum. The typical French concern for textual intelligibility is anchored in the necessity of finding as close a correspondence as possible between music and text – its syntax and prosodic qualities. The recitative is then viewed as the privileged vocal locus of the tragédie en musique – the pièce de résistance of the operatic spectacle – as long it does not become full song and lose its ties to the theatrical model of declamation (hence the enduring fame of the apocryphal anecdote on Lully modelling his recitative on La Champmeslé’s declamation).

Récit and Air as Paradigmatic Categories

The vocal style of the tragédie en musique is divided into two categories, known as ‘récit’ and ‘air’ in late seventeenth-century terminology. The first referred to a syllabic, recitative-like manner, and the second to a more tuneful style.21 In practice, however, the categories could overlap: the delivery of the récit could take the character of an air, while the air could also be referred to as a récit – this can be seen in scores and other sources. In its common usage, ‘air’ refers to a closed form, most frequently a vocal piece following the model of the air de cour, with which it also shares its brevity, especially when compared to the Italian aria. ‘Air’ could also be the name given to an instrumental piece (sometimes the instrumental adaptation of an air de cour), one often used for a specific dance in a ballet or a divertissement: for instance an air de ballet or, more specifically, a dance related to its performance (e.g., air pour les matelots, etc.). Whether instrumental or vocal, the air is defined by its recurrent melodic pattern and its regular metre, which is often matched with a dance rhythm: the 1694 edition of Dictionnaire de l’Académie française defines the air as ‘a succession of agreeable tones that make a regular song’.22

‘Récit’ has a more varied meaning. When translating it as ‘recitative’, one should keep in mind that its original French meaning is ‘narration’, a relation of some action that occurred. The Dictionnaire de Furetière (1690) gives two entries for the term: ‘narration’ and ‘what is sung by a solo voice and especially by a dessus. A beautiful music should be intermixed with récits and choirs’.23 The 1694 edition of the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française gives only one entry but addresses both meanings. As a musical term, a récit is ‘what is sung by a solo voice, and that begins a ballet, an opera, or another divertissement by exposing its subject’ and as ‘everything sung by a solo voice detached from a great choir of music’.24 Tellingly, neither definition elaborates on its musical peculiarities, except to mention that it is sung by a solo voice. What prevails is a rhetorical conception of the récit and its function to reveal and develop the tenets of the plot, or the ‘sujet’, to use the seventeenth-century French term.

The musical texture of a récit requires a basse continue written in a harmonic language generally simpler than the Italian recitative (all these features of Lullian opera were going to change dramatically in Rameau’s works, leading many of his contemporaries to label his musical style exceedingly Italianate during the Querelle des Lullistes et des Ramistes). The French récit is easy to notice in a score, due to the changes of time signature and alternations between binary and ternary measures. Since the intention is to follow and emphasise the poetic rhythm of the lines by marking their caesuras and tonic accents, the récit is devoid of any regular beat, a feature that highlights the legacy of musique mesurée.

We tend nowadays to call this French recitative ‘unmeasured recitative’. It was paradigmatic of the style idealised by the Lullian model of sung declamation, but its metrical idiosyncrasies were not systematically observed. Here, establishing a parallel with the Italian practice can be helpful to a certain point. (Italian) recitative is routinely viewed as the primary vehicle for dialogue and for conveying information. As for the aria, it should focus on a more effusive exploration of one or two affects, which is why an Italian libretto easily reveals which verses are intended for the aria: they tend to be shorter than those for the recitative and are gathered in more compact strophes. For that reason, the aria is often said to create a pause in the dramatic unfolding of the action. To this must be added the case of impassioned monologues signalling extreme displays of passion (e.g., mad scenes). These would often be carried by the recitativo accompagnato, that is, a recitative with a more complex instrumental accompaniment, usually strings reinforcing the continuo. While this division of labour is mostly typical of eighteenth-century opera seria, it was already well under way by the end of the seventeenth century.

The function of the recitative in late seventeenth-century French opera could also be used both for conveying information and for rendering climactic moments of passion: but these different degrees of expression did not seem much to alter the style of the recitative itself, when compared with the Italian simple recitative and its accompanied counterpart. A typical instance of such a climactic use of the unmeasured recitative is Armide’s celebrated scene in Lully’s eponymous opera (1686; Act II scene 5). An extended monologue, the scene starts with an instrumental ritornello introducing Armide’s unmeasured recitative, ‘Enfin, il est en ma puissance’, followed by a brief conclusion on a strophe of six lines (starting on ‘Venez, venez, secondez mes désirs’). This conclusion is itself introduced by another instrumental ritornello on a 34 time signature, the melody of which is repeated twice in the vocal part. Departing from the preceding unmeasured recitative, this conclusion is written entirely in the 34 time signature: the new ternary measure and its recurrent melodic pattern lend the passage the aura of an air. Yet, it would be a stretch to suppose, just by looking at the disposition and length of verses in a French libretto as compared to those of an Italian libretto, that this is where the closed form of an air should take place. Here, the dramatic emphasis of the entire monologue is carried by the unmeasured recitative, not by the concluding and much shorter air-like section.

During and after Lully’s time, it was this section in unmeasured recitative (‘Enfin, il est en ma puissance’) that was regarded as the climax of the scene. Its fame as a model of impassioned monologue continued throughout the eighteenth century.25 An Italian conception along the lines of opera seria would have predicted the contrary: a rather brief recitative, possibly with an accompanied recitative in the middle to emphasise Armide’s trouble (starting at ‘Quel trouble me saisit’). Then, as the climax of the scene, Armide’s ‘aria’ (‘Venez, secondez mes désirs’).