Among John Cage's most famous and influential works stands his groundbreaking electronic composition Williams Mix (1952–53), so titled to pay homage to the young patron who funded the project, Paul Williams (1925–93). But who was this unheralded and elusive figure who played such a critical role in Cage's life? By exploring the paths of these two men over a period of more than two decades, this article amends a number of long-held biographical narratives and repositions Williams from that of a marginalized and often neglected protagonist to his rightful place alongside a man Richard Taruskin calls “one of the most influential creative figures in the world.”Footnote 1 Inheriting a substantial sum of money after his father died, Williams chose to pledge much of his fortune to support the lives of struggling artists. This he did through no-strings-attached grants and by inviting fellow compatriots to join him in his own utopian vision called the Gatehill Cooperative, often referred to (after an adjacent town) as Stony Point. Established in 1954 and located thirty miles north of Manhattan, on the outskirts of the town of Haverstraw, Cage was among a small but prominent group of former Black Mountain College faculty and students who followed Williams there. The very first Gatehill home designed by Williams was that shared by Cage and the Williams family, their quarters separated only by a rock wall meticulously erected by Cage himself. The experience opened a world of new possibilities for the composer and occupied a place he called home for the next seventeen years (Figure 1).Footnote 2

Figure 1. John Cage in front of his Gatehill Cooperative home, ca. 1960. Photograph by Betsy Williams. Courtesy of the author, Landkidzink Image Collection.

I should add from the outset that my mother, Patsy Lynch (Davenport Wood), attended Black Mountain College from 1942 to 1948 where she also came to know both Cage and Williams.Footnote 3 Our family was among that founding group of artists and musicians at Gatehill, and I spent most of my childhood and early adult life there. My father, LaNoue Davenport, continued to reside in our original family home at Gatehill until his death in 1999.

First Encounters: Black Mountain College

Paul Francis Williams Jr. was born on May 2, 1925, the son of a self-made millionaire and inventor (Paul F. Williams Sr.) who made his fortune in electrical engineering through the G & W Electric Specialty Co. that he founded in Chicago. Paul's mother, Gretchen, was a Christian Scientist and a very “independent thinker,” a farm girl from a poor family who later worked as a secretary at G & W before she and Paul Sr. were married.Footnote 4 From kindergarten through high school Williams attended the prestigious North Shore Country Day School (NSCDS) in the affluent village of Winnetka, Illinois. Williams excelled as a student and became particularly active in athletics, woodworking, and student government (he was elected president during his senior year).

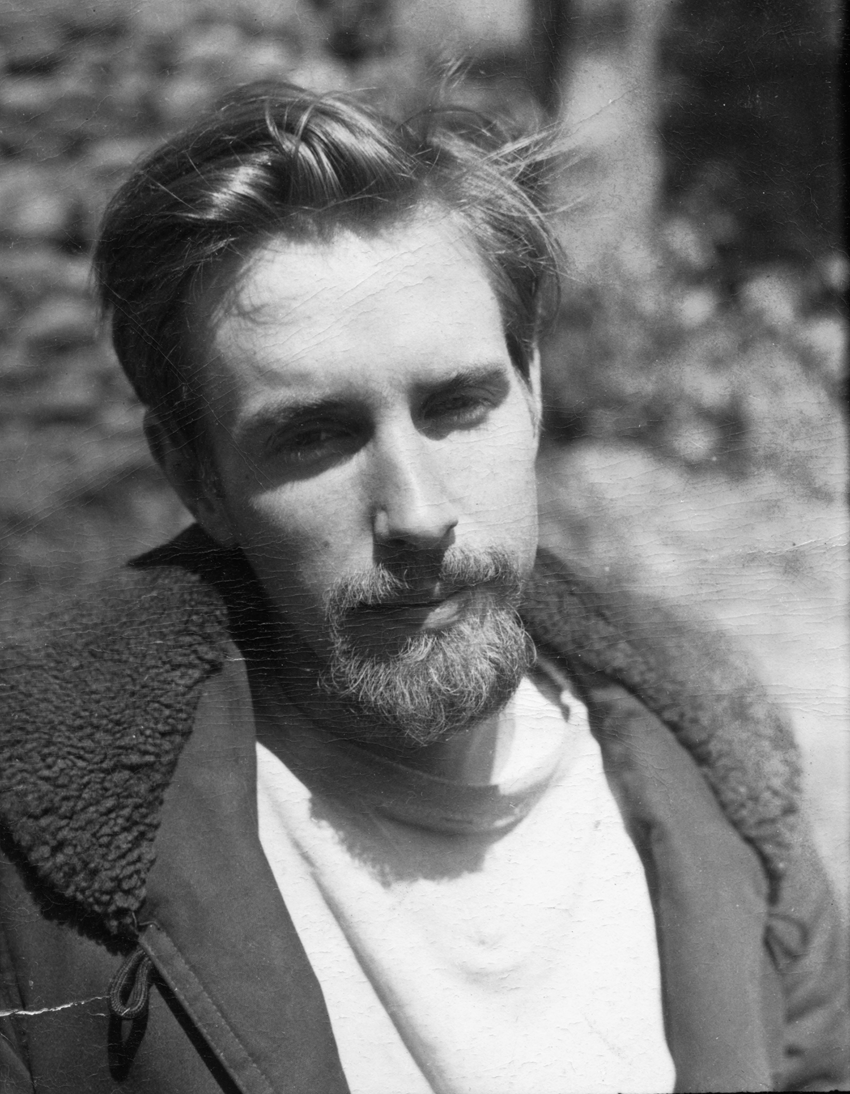

After graduating from NSCDS in the spring of 1943, Williams enlisted in the military eventually serving as a navigator aboard a B-29 bomber during World War II in the European theater of operation.Footnote 5 Almost immediately following his wartime service, Williams found his way to Black Mountain College (BMC), having heard about the college (founded only twelve years earlier) from his former NSCDS history teacher, David Corkran. Corkran joined the faculty at Black Mountain shortly before Williams arrived. The experience was transformative. Despite coming from a family of wealth—or perhaps as a reaction against it—Williams developed a disdain for pretension in all its forms. At Black Mountain, Williams became the quintessential nonconformist (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Paul Williams at Black Mountain College, ca. 1947. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Paul F. Williams Architecture and Design Archive.

With an avid interest in architecture Williams was soon drawn to the German architect Walter Gropius who founded the Bauhaus school in 1919. Gropius fled Germany in the mid-1930s and soon joined the Department of Architecture at the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University, which he chaired from 1938 to 1952. Within months of his arrival in the United States, Gropius visited his old friends and colleagues at Black Mountain, including the renowned painter and former Bauhaus faculty member Josef Albers and his wife Anni Albers, both of whom Williams studied with during his student years there. Gropius remained close to the Alberses and became a member of the BMC Advisory Council from 1940 to 1949. He visited the campus frequently and taught architecture courses for three consecutive summer sessions (1944–46) for the college's Summer Arts Institute. His daughter Ati, who milked cows with my mother Patsy as part of the Work Program duties, attended the college from 1943 to 1946. Williams enrolled in Black Mountain in January 1946 and had the opportunity to study with Gropius who instilled in Williams a distinct Bauhaus aesthetic.Footnote 6

At Black Mountain, Williams met nearly all of the future founders of the Gatehill Cooperative, including fellow students Vera Baker (whom he married at Black Mountain), Patsy Lynch (Vera's college roommate), Stan VanDerBeek, and Betsy Weinrib (Williams's second wife after his breakup with Vera in the mid-1960s). Former Black Mountain College faculty members included the writer, philosopher, educator and poet M. C. Richards; the concert pianist and electronic music composer David Tudor, who began a ten-year-long romantic relationship with Richards there; the married potters Karen and David Weinrib (the older brother of Betsy Weinrib); and of course John Cage and dancer/choreographer Merce Cunningham, Cage's lifelong professional and romantic partner.

During the 1948 spring semester at Black Mountain, Williams had his earliest opportunity to meet Cage whose first invitation to teach there (from Josef Albers) came with the college's 1948 Summer Arts Institute. Prior to the summer session Cage and Cunningham had stopped at the campus for six days in April (a detail seldom mentioned in the Cage literature) during the middle of their first cross-country joint tour. For six weeks the two hopscotched between college campuses in a borrowed car.Footnote 7 Of all their campus visits, Black Mountain gave Cage, according to biographer Kenneth Silverman, “more personal pleasure than any of the others … and aesthetic excitement that once more led his imagination in new directions.”Footnote 8 During Cage's stopover he likely gave the first public performance of his just-completed Sonatas and Interludes,Footnote 9 nine months before its official premier at Carnegie Hall the following year.Footnote 10 Immediately following the concert and “coffee in the community house,”Footnote 11 the enthusiastic Black Mountain audience members (Williams among them) participated in an extended Q&A session. One can only imagine the effect such a fresh and innovative work as Sonatas and Interludes had on its first listeners. Williams was especially captivated and soon became one of Cage's staunchest allies. Cage, in turn, was struck by the powerful sense of community and natural beauty of the College's Lake Eden campus, writing to Anni and Joseph Albers that “Being in New York without leaving it for so long had made me believe that only within each one of us singly can what we require come about, but now at Black Mountain … I see that people can work still together. We have only ‘to imitate nature in her manner of operation’.”Footnote 12 Knowing that less than six years later Cage expressed similar longings for community and nature, with his move to the Gatehill Cooperative, his words are prophetic.

News of a Cage/Cunningham return to Black Mountain for the upcoming eight-week summer session became the topic of campus conversation, and Cage was up for the challenge. For his first BMC faculty appointment Cage directed an impressive festival in honor of the French composer Erik Satie, with whom Cage had become enamored. Satie was both eccentric and relatively unknown at the time, and Cage set out to become one of his leading champions. “I was at that lovely youthful first blush of love of Satie,”Footnote 13 he later reflected on that memorable summer, proudly calling himself a “missionary” for the composer's cause. The ambitious festival schedule included more than two-dozen evening concerts (offered three nights a week) of Satie's music. Preceding each performance Cage provided brief instructive and sometimes provocative remarks, tame by comparison, however, to his stand-alone lecture “In Defense of Satie,” in which he shocked and divided the campus community with his polemic against Beethoven. “This proved to be a totally new experience from the years before,”Footnote 14 my mother observed, who stayed on that summer following her graduation to assist Cage in the festival. “Cage's presence was highly exhilarating, though it created an electricity that tore the community into two musical camps. At mealtime, people stood up and made declarations about the very existence of music! All kinds of feelings were generated and persisted throughout the summer. For me, it was a time of questioning the status quo.”Footnote 15

The Williams Mix

Those early encounters with John Cage so impressed Paul Williams that when he later inherited the small fortune left to him by his father (about $1 million), in early 1952, his first major underwriting was a gift of $5,000 to Cage's magnetic tape project (equivalent to about $48,000 today). Soon to be known as “The Williams Mix,” work on the mammoth composition “for eight tracks of ¼-inch tape that required splicing together more than six hundred recorded sounds to create a work of less than five minutes’ duration”Footnote 16 extended over a period of nine months. The funding not only supported Cage but also his New York City–collaborators David Tudor, composer Earle Brown, and sound engineers Louis and Bebe Barron.

As Tudor recounts, “The project actually began because our friend Paul Williams gave us some money. He was a godsend. … John and I were impoverished. … I recall that at one point the money was in danger of running out, and so John and I made an assessment of what had to be done so that the funds would last until the completion of Williams Mix.”Footnote 17 In a letter to Paris correspondent and fellow composer Pierre Boulez, Cage explained that the group divided the funds equally between them. The $5,000 given by Paul Williams, he wrote Boulez, “will carry us through Nov. 15 and assures us of 2 full days per wk in the studio.”Footnote 18

So engrossed was Cage in the tape project that when he was asked to return to Black Mountain and teach composition that July, he literally brought the project with him.Footnote 19 “When I announced the classes in composition,” Cage later told BMC historian Martin Duberman, “I announced also … that I would not teach people their work, but rather my work, and that furthermore they would act as apprentices for me and do my work for me. That is to say in this laborious work of making the Williams Mix. As a result, I had not one student.”Footnote 20

The interview conducted by Duberman in 1969, at a time when Cage still lived at Gatehill, informs us in two ways: 1) it provides insightful recollections by Cage; and 2) the transcript of the interview is peppered with Cage's own handwritten “changes and omissions.” An excerpt of that interview with Cage's annotations is revealing:

CAGE: The reason it was called Williams Mix, was because Paul and Vera Williams—who gave so much support to Black Mountain and who had been students there and who had been married there—were also financing my work with magnetic tape. Subsidizing it. And that included subsidizing the work of David Tudor which meant subsidizing MC Richards and—let's see, who else?

DUBERMAN: I didn't know that. Paul Williams was too modest to tell me.

CAGE: Yes. He's very modest. He's done marvelous work and too little is known about his influence. It was so open—everything was done without strings attached. Beautifully.Footnote 21

In the bottom margin of this page in the interview transcript Cage writes, “Don't use this unless Paul Williams agrees” (Figure 3). What a telling statement! Not only was Williams modest to the extreme but also he shunned any part of the limelight to the point that even his closest friends and beneficiaries were hesitant to publicly offer their admiration for fear of offending him. Having that kind of selfless personality says a lot about why so little attention was afforded Williams and consequently, why so little has been written about him.

Figure 3. Handwritten comments by John Cage on transcript of phone interview by Martin Duberman. Martin Duberman Collection, State Archives of North Carolina, Western Regional Archives, Asheville, NC.

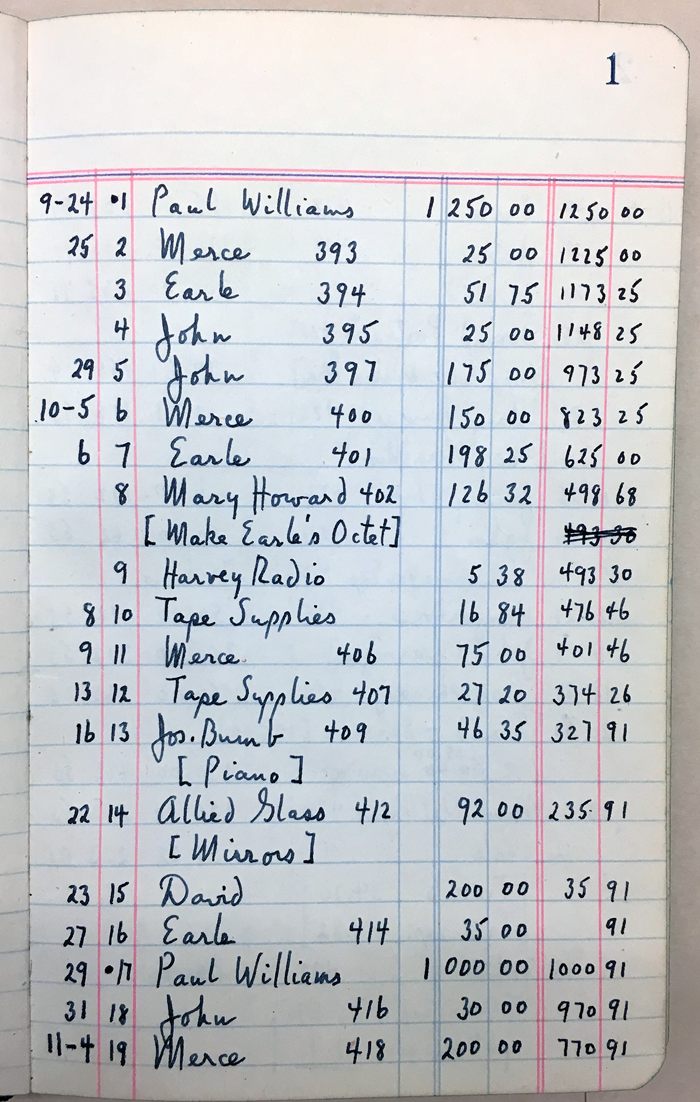

Williams Mix, as it turns out, became just one of several large-scale works that fell under the umbrella rubric “Project for Music for Magnetic Tape.” Fortunately for all, Williams continued to fund the project, some of the details of which are documented in a heretofore-overlooked ledger book housed in the David Tudor Papers at the Getty Research Institute.Footnote 22 Taking a closer look, the five ledger columns are easy enough to follow (Figure 4). Reading left to right, the columns document: 1) the date; 2) the ledger entry number; 3) a brief description of entry (sometimes accompanied by what is likely a corresponding bank check number); 4) the income or expense amount; and 5) the balance. Note that a small black dot appears just to the left of the entry number in column 2 to indicate “income” rather than “expense.”

Figure 4. Page 1 of David Tudor's financial ledger (1953) for the “Project of Music for Magnetic Tape.” David Tudor Papers, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (980039).

The very first entry, indicating income of $1,250 from Paul Williams, is dated September 24, 1953 (“9–24” in Figure 4). What follows is a veritable treasure-trove of documentation about the professional activities, not only for all involved in the extended Project of Music for Magnetic Tape but also for the underwriting of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, founded that fall, for which Paul Williams likewise became the primary benefactor. Also, on the same first page: checks to Merce Cunningham, John Cage, David Tudor, and Earle Brown, with funding for his Octet (one of three other major works to come out of the magnetic tape project besides Williams Mix). Other pages list the donations from Williams going to checks issued to artist Robert Rauschenberg as well as all of the dancers in Cunningham's new company.

Funding from Williams did not seem to arrive on any regularly set date or with any predetermined amount but rather appeared in the nick of time just as the monthly or even weekly account balance dwindled to zero: a second entry for $1,000 deposited on September 29 (Figure 4); then $500 on November 30; $787.63 on December 3; $3,500 on December 11; $1,000 on December 30 (then continuing into 1954); $95.01 on March 10; $785.24 on April 9; $273.63 on May 10; and $930.14 on June 7, 1954, the last page and date of the accounting. Based on the numbers in this ledger book alone, Williams donated $10,121.65 in addition to the initial $5,000 (a total of $15,121.65—about $145,000 if adjusted to 2020's rate of inflation) over the course of some twenty-eight months (February 1952 through June 1954), coming to a close just as Cage, Tudor, and Richards were packing their belongings for their move to “Stony Point” that summer.Footnote 23

From Black Mountain College to the Gatehill Cooperative

During the summer of 1953, Williams was asked by BMC rector and poet Charles Olson to come down to teach a course in architecture and to be the campus's resident architect. Accepting the invitation, Paul and Vera arrived from Boston (where Williams had been studying civil engineering at MIT) with their two young daughters. They quickly became alarmed with the school's state of disarray, the small number of students, and the lack of administrative leadership. Williams contemplated how best to keep the college financially afloat. Perhaps he could coerce the New York faculty group to move down to the campus permanently; Cage, Cunningham, Richards, Tudor, and others, like composer Earle Brown and his wife Carolyn Brown, one of the up-and-coming young dancers in Merce Cunningham's dance troupe (Figure 5), had all been down to the College the prior summer.

Figure 5. Carolyn Brown and Merce Cunningham, Suite for Five, 1956. Photograph by Radford Bascome. Courtesy of the Merce Cunningham Trust.

With Black Mountain's future in such financial jeopardy, few have fully understood that the decision to form Gatehill, the following summer, was a conscious alternative to resuscitating the flailing school. “It all began,” writes Carolyn Brown,

with a phone call to John, Merce, M. C., and David, from Paul Williams at Black Mountain. More than once Paul had bailed the school out of financial disaster. … Black Mountain was in its death throes. Paul wondered if it could be saved. Would the New Yorkers come back as permanent faculty? If not, did they think he should continue to help Black Mountain with financial and moral support, or should he try to start an artist's community elsewhere, and if he did, would they participate, and if they would, where should it be located?Footnote 24

After many dinner gatherings and conversations at Cage's New York City apartment, “there was a general agreement,” Carolyn Brown continues, “that no one wanted to be at Black Mountain year-round and that any community should be located within driving distance of New York.”Footnote 25 Consequently, without the support of the New York group, and particularly without the continued financial backing from Williams at this critical point in the school's history, Black Mountain closed its doors just two years later.

As M. C. Richards later wrote,

So: here we all were, rising up out of the ground of Black Mountain, hopeful, connected, anxious, ignorant, motivated, unfocused. … John, who had always been a city man, and a private man, was ready, he said, to try the country, to discover nature, and to learn to live closely with others.

David [Tudor] and I were already looking for a way to move out of our tenement on the Bowery. … We were all poor, and thought of the economic advantages of sharing rent and food. We were close friends and rejoiced at the prospect of living together. … All of us were ready to make a change. We were already a community of friends and interests. … What did we want to do, asked Paul Williams as we sat around John's marble slab in Manhattan. We wanted to be within commuting distance of New York, so that people who needed the city for employment could have it. John and David wanted a theater and electronic music research center.Footnote 26

“Discussions went on week after week,”Footnote 27 recalls Carolyn Brown, with Williams eventually placing a small advertisement in the Merce Cunningham Dance Company concert program (December 29, 1953–January 3, 1954) at the Theater de Lys. It read: “WANTED, about 100 acres, hilly, mostly wooded, with stream or lake and house, up to 50 miles N.Y.C. Call Williams, WA 6-4744.”Footnote 28 And so began their months-long search for the most promising location. Finally, in the spring of 1954, they found an ideal site: three tracts of land, totaling 116 acres, with a stream and an old farmhouse in Haverstraw, New York. “I will never forget the day,” recalls M. C., “I had been sick with pneumonia, a month shut in a fifth-floor tenement off the Bowery. We came out here on a bright morning. Patches of snow still here and there. Only the little white house then. … We sat on a pile of grass in the field where the pot shop is now and marveled at the beauty and our luck”Footnote 29 (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The preexisting nineteenth–century farmhouse at the Gatehill Cooperative, ca. 1960. Photograph by Robert C. Folley. Courtesy of the Robert C. Folley Archive.

With the little white house and acreage purchased by the Williamses for $15,000, Paul and Vera immediately moved nearby, renting a house just a few miles from the new property; the “Land,” as they affectionately called it very early on. Richards and Tudor moved into one of the two bedrooms in that old farmhouse, with Cage occupying the attic. Karen and David Weinrib (then still teaching at Black Mountain) soon joined them, moving into the spare bedroom. All five lived in that small farmhouse for a time, while eagerly assisting with the construction of their new homes and studios.

It may surprise Cage aficionados to learn that he never actually lived in the town of Stony Point. The error stems from members of the community itself who often refer to themselves as residing in Stony Point. And in Cage's case the inaccuracy was broadcast throughout the world in that now ubiquitous 1960-clip as a contestant on the popular TV show “I've Got A Secret,” in which he answers the host's question, “Will you tell our panel please what your name is and where you're from,” and he responds, “My name is John Cage. I'm from Stony Point, New York.” The muddle arising from Cage's understandable but flawed response, and consequently referenced in his numerous letters of correspondence and manuscripts, relates to a somewhat confusing but ordinary US postal practice; Gatehill Co-op members, although living in the most remote north end of the town of Haverstraw, collected their mail on the other side of Willow Grove Road (a.k.a. Gate Hill Road), where our mailboxes were located, just over the town boundary in the “town of Stony Point.”Footnote 30 Accordingly, our mailing addresses say “Stony Point” and it simply became too bothersome to explain the reason why.

This geographical detail may seem insignificant were it not for its perpetuation by current scholars who thus unintentionally add another layer of historical inaccuracy. One recent example is indicative of how a simple fact like geographic location can be so easily misconstrued. In his book on the correspondence between John Cage and David Tudor, Martin Iddon writes, “In August 1954, Cage, along with Tudor and M. C. Richards, departed New York City for rural Stony Point, on the banks of the Hudson River, near to Albany in upstate New York, some 150 miles from New York City itself.”Footnote 31 Here Iddon inserts the footnote, “The town of Stony Point itself was founded in 1865. The attraction for Cage, however, was the foundation of a new artistic community there by the architect Paul Williams, perhaps inspired by Black Mountain College, at which he had taught.”Footnote 32 The brief prefatory sketch at once distorts the distance between the Gatehill Co-op and New York City—the community was just thirty miles (not 150 miles) north of Manhattan and nowhere near the state's capital of Albany—and yes, Gatehill was close to the Hudson River (a short ten-minute drive) but definitely not “on its banks” (Figure 7).

Figure 7. (Color online) Partial map of Rockland County, New York. Google Earth, accessed December 21, 2018. https://www.google.com/maps/@41.2136018,-74.0272061,14z. The irregularly–shaped property of the Gatehill Cooperative is circled. Note the small towns of Stony Point and West Haverstraw to the east. The large surrounding area to the west is the east portion of Harriman State Park.

Perhaps more clarity could have been achieved over the years by simply emphasizing the name “Gatehill Cooperative” rather than the name of the town in which the community was incorporated. But, certainly (and this is the key point being made here), references to the quaint Hudson River town of Stony Point as both home and mushroom hunting ground for Cage, instead of the significantly more expansive 116 acres of secluded mountainous property surrounded on three sides by the second largest park in New York State,Footnote 33 fail to accurately cast the Gatehill community and its environmental haven of natural beauty as the true source of inspiration that so moved Cage and the many figures who visited him there.

From the Bauhaus to Our House

During that exciting and ambitious first year at Gatehill Williams immediately set to work, setting his imagination to pencil and paper as the images literally took living shape (Figure 8). “Paul was interested in the architectural planning of a community,” Richards recalls,

the effect of design on social forms and values, a chance to test out ideas, to experiment and to learn outside the usual requirements of the social and building code. He said he would like to make a place which would have the spirit of one of those hilltop towns along the Mediterranean coast. Thirty or forty families, heterogeneous, maybe some small stores, small industries, a village economy. He was interested in designing houses and groups of houses in such a way that social values would be fostered by the design itself. And so squares developed.

He had been dreaming of the possibility of starting a community someday, using the architect's imagination as a humane force of social vision—he had not yet thought to begin so soon. After all, he was not yet thirty years old, and had expected to wait longer to begin a mature work of such magnitude. But, as he said, you can't always choose your moment. And he bravely entered into the adventure.Footnote 34

Figure 8. Early sketch of the Gatehill Cooperative by Paul Williams from his architectural notebook, ca. 1953–54. Courtesy of the Paul F. Williams Architecture and Design Archive.

Williams eventually drafted a very deliberate building plan, essentially adhered to over the course of the next decade. Before a single nail was hammered on the first square, however, it became a top priority to get a working pottery set up as Richards, David Weinrib, and especially Karen Weinrib (later Karnes) counted on their craftwares for income.Footnote 35 That first fall was also spent fixing up the little farmhouse and almost constant work on land development: clearing trees, brush and boulders, creating roadways and parking areas, digging wells and septic fields.

During the winter Williams designed and built a triangular piano studio for Tudor (Figure 9), set between the pot shop and the flat area along the foot of the mountain, near a former pumpkin patch already referred to (with great anticipation by Cage and Cunningham) as “the theater field.” Vera Williams designed and affixed the glass and stone mosaic patterns on the exterior front panels.

Figure 9. David Tudor's piano studio, ca. 1960. Photograph by Betsy Williams. Courtesy of the author, Landkidzink Image Collection.

Finally, in the spring of 1955, work began on the first of four homes to be built in a square near the upper part of the mountain—the “Williams-Cage” house—essentially a duplex. The Williams-Cage floor plan became the only home built with a common wall between two residences; Cage's single-occupancy home (on the west side of the wall) rested on the side of the mountain with the Williams's three-bedroom family home (on the east side of the partition) extending away from the mountain, over a sunken living room, and anchored at the east end onto two long metal poles. Figure 10 shows early construction of the home, the first stage of the rock wall providing part of the foundation that supports the weight of the structure.

Figure 10. (Color online) Construction site: “Williams-Cage” house, 1955. Photograph by Richard Hora. Courtesy of Mies Hora.

The lower supporting section of the rock wall, as well as the upper dividing part, was industriously stacked and mortared by Cage himself (Figure 11) with help from Vera Williams and members of the construction crew who foraged a bit further into the forest each day for appropriately sized and shaped rocks.

Figure 11. (Color online) John Cage applying cement to the base of the rock wall he built with Vera Williams at the Gatehill Cooperative, 1955. Photograph by Richard Hora. Courtesy of Mies Hora.

Figure 12 reveals the completed “Williams-Cage” home. In this photograph one can observe that John and Vera eventually ran out of rocks (or inspiration) before reaching the top of the wall. Consequently, Paul built storage cabinets above them. The original design, shown here but later modified, had an open walkthrough area under the middle of the home. The translucent fiberglass wall of the sunken living room, on the ground level of the Williams side, originally swung open like a garage door.

Figure 12. Construction site of Williams-Cage home, November 1956. Photograph by Valenti Chasin. Courtesy of the Paul F. Williams Architecture and Design Archive.

Interior features included a sunken fireplace in Cage's back room, marked by a large open solid copper chimney (Figure 13).

Figure 13. John Cage's back sitting room with sunken fireplace. Gatehill Cooperative, ca. 1959. Photograph by Betsy Williams. Courtesy of the author, Landkidzink Image Collection.

Cage's westside glass wall, facing up the mountain in the front living area (Figure 14), could be slid open into an extended wood frame.

Figure 14. John Cage's sliding glass living room wall (shown open), ca. 1957. Photographer unknown. David Tudor Papers, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (980039).

It is easy to see how Cage (seen in Figure 15 standing in the open frame of his sliding glass living room wall) was influenced by his new living environment. “I have discovered such a full hunger for nature within me,” he wrote to close friend and fellow composer Lou Harrison that May, that now “nothing is as important as rocks and plants are.”Footnote 36

Figure 15. John Cage standing in the open frame of his sliding glass living room wall, in front of his home at the Gatehill Cooperative, ca. 1960. Photograph by Betsy Williams. Courtesy of the author, Landkidzink Image Collection.

Other homes quickly followed—for the enamellist Paul Hultberg and his family in 1955, the Davenport family in 1956, and Betsy (Weinrib) Epstein and her family in 1958—marking the completion of the Upper Square (Figure 16), and revealing the purposeful and philosophical underpinnings of Williams's plan, the transparent link to the Bauhaus aesthetic (something assimilated by almost all of the ex-Black Mountaineers) finally laid bare:

Flat roofs, smooth façades, and cubic shapes. Colors are white, gray, beige, or black. Floor plans are open and furniture is functional. … Glass curtain walls were used for both residential and commercial architecture. More than any architectural style, however, the Bauhaus Manifesto promoted principles of creative collaboration—planning, designing, drafting, and construction are tasks equal within the building collective. Art and craft should have no difference.Footnote 37

Figure 16. View of the Upper Square (from Cage's front living room) at the Gatehill Cooperative, ca. 1960. Photograph by Walter Rosenblum. Courtesy of Naomi Rosenblum and the Paul F. Williams Architecture and Design Archive.

The simplicity, even minimalism, of the original interiors of the homes at the “Land” are clearly evident in these early photos (Figure 17); the integration of craftsmanship and art, in the ornamental features of each home, among the most obvious and conscious connections to the Bauhaus Manifesto that implored architects, painters, and sculptors to “learn a new way of seeing and understanding the composite character of the building, both as a totality and in terms of its parts.”Footnote 38 Williams conspicuously hired a panoply of workers to raise their mountain homes, including unskilled artist and musician laborers, made up of members of the community itself. In the process, Williams squarely embraced the earliest ideas and aims of the Bauhaus founder, Walter Gropius, who professed that “the wall of conceit that separates the artist from the workman must disappear … for in the last analysis we are all working men. … Away with the snobbery of art—let us all learn to be laborers for the common good in the great democracy of tomorrow.”Footnote 39

Figure 17. Interior of Williams home, ca. 1960. Photograph by Walter Rosenblum. Courtesy of Naomi Rosenblum and the Paul F. Williams Architecture and Design Archive.

This aspect of “hands-on” community labor did not end with the completion of our homes. Weekly “Brush Days,” in the spirit of the Work Program at Black Mountain College, were attended by everyone in the community for the continued maintenance of the property and residences. In Figure 18, community members David Weinrib (on the left) and Cage (on the right) are gazed upon by little “mini-me” in restoration work on the retainer wall of the Epstein home in the Upper Square (a partial view of the unusual arched-shaped Davenport home can be seen in the background).

Figure 18. “Brush Day” in the Upper Square at the Gatehill Cooperative. From left to right: Mark Davenport (sitting), David Weinrib and John Cage, Summer, 1959. Photograph by Betsy Williams. Courtesy of the author, Landkidzink Image Collection.

Community as Art

Although openly referring to the community as “Black Mountain of the North,” Gatehill was never meant to be a college, per se. As like-minded intellectuals, artists, educators, and social activists, the founders shared many similar philosophies of living and imagined creativity, learning and education happening on a more organic and all-encompassing scale. Both Paul and Vera had studied social planning at Black Mountain with the controversial social critic, novelist and poet Paul Goodman, who defines small intentional communities as “progressive schools.” “In the theory of progressive education,” Goodman writes, “integral community life is of the essence: one learns by doing.”Footnote 40

In this sense, the early founders believed that life itself was “best understood and practiced as an art, the way that art is understood and practiced.”Footnote 41 The interconnectedness of creative energy with the daily activities of the community are self-evident. As the community grew in size, adding a second “Lower Square,” including a studio home for the Hungarian-born American artist Sari Dienes and a collaborative building project between Williams and experimental filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek, Williams expected that each member contribute to the planning and building of their own homes, a vital and central force during those first years. In turn, Williams designed and built the homes totally cost-free and laid out the capital for the purchase of the land and materials through long-term interest-free loans. All members were expected to serve terms on the executive board (Cage was, in fact, elected the community's first secretary and later served as president), and everyone took part in regular co-op meetings where ideas of how the community ought to operate were considered, articulated and argued. Decisions were made by unanimous vote. Communal ownership of the land and houses represented one of the more radical bylaws reached by the founders.

Very early on, the community openly embraced interracial relationships and marriage, and supported the rights of gays and lesbians. There was a period of collective child rearing for the youngest children, allowing more freedom, particularly for the women, to follow their own artistic and career paths. Many members (including us children) took part in local civil disobedience, some of which resulted in jail time. Seeking an alternative to the public school system, some community members sought to establish an experimental school on the property, settling instead on a large home in the town of Stony Point. The Bob Barker School (that became Collaberg School), modeled on the British Summerhill Schools founded by A. S. Neill, became the first school of its kind on the east coast (1961) and the third of its kind in the country.Footnote 42 Subsidized in large part by Paul and Vera Williams, many Gatehill community members constituted the first faculty members and their own children are recorded among the first students of the school. Paul Goodman sat on its board of directors.

Others were active with a “little magazine” called Liberation that became one of the most outspoken voices for humanitarian issues, civil rights, and the anti-war movement during the 1950s to the mid-1960s. Community members contributed poems and essays alongside the writings of Paul Goodman, Bayard Rustin, David Dellinger, and Martin Luther King, Jr. The Williamses provided substantial and sustained funding for its publication. Working at her kitchen table, Vera designed a remarkable series of illustrations for the magazine's covers; at the same time, sitting literally feet away (on the other side of the rock wall she and John had only recently completed), Cage immersed himself in mycology, letter writing, and equally radical musical compositions.

Concurrently, Paul Williams actively supported the innovative New York-based theater company called the Living Theatre, founded in 1947 by Julian Beck and Judith Malina. With the aim of presenting unconventional staging of poetic drama by underexposed writers (e.g. Gertrude Stein, William Carlos Williams, Paul Goodman, Bertolt Brecht, Jean Cocteau, and others) this “little theater” almost single-handedly pioneered the off-Broadway movement. Proclaimed as “the most radical, uncompromising, and experimental group in American theatrical history,” the Living Theatre “profoundly affected theatre in Europe and America while moving on the edges of society and violating many of the taboos of culture and government.”Footnote 43 Consequently, their activities naturally overlapped with other figures of the New York avant-garde, including many former Black Mountain faculty: Lou Harrison, Richard Lippold, Paul Goodman, and especially John Cage, Merce Cunningham, David Tudor, and M. C. Richards.

As early as 1956, when it became apparent that Cunningham wanted to keep his apartment in New York City rather than attempt to build a theater in the large field at Gatehill, Cage suggested to Beck and Malina that Williams might be interested in financing their theater which, in turn, “would have a stage large enough for John and Merce's concerts.”Footnote 44 Not only did Williams end up financing a new space for them, he laid out architectural blueprints for the theater, a plan that involved a substantial renovation of the former Hecht's Department Store along Sixth Avenue on West Fourteenth Street. In typical Williams fashion much of the work was carried out through volunteer labor. Vera Williams and Judith Malina scraped and painted 160 chairs donated from the old Orpheum movie house on Eighth Street and Second Avenue, painting them “in gray and lavender pastels, reupholstering the seats with striped awning fabric and drawing oversized circus numbers on the seat backs in bright magenta or orange.”Footnote 45

Paul Williams commissioned several Gatehill community members to design ornamental installations for the lobby; Paul Hultberg made enamel panels to adorn the lobby doors.Footnote 46 David Weinrib built a fountain for the lobby, for which he constructed an elaborate system of brass piping.Footnote 47 Inside the theater itself, narrower and narrower stripes converged from the back of the theater toward the stage “concentrating the focus, as if one were in an old-fashioned Kodak, looking out through the lens, the eye of the dreamer in a dark room. … We had talked … with Paul Williams, who designed the Fourteenth Street theatre for us,” Julian Beck would later write, “about the theatre being like a dream in which the spectator is the dreamer and from which he emerges remembering it with partial understanding. … That is why the lobby was painted so brightly, the brick walls exposed, like the walls of a courtyard, the ceiling painted sky blue, a fountain running as in a public square.”Footnote 48 These ideas were all Williams's attempt, Beck recognized, “to achieve an atmosphere for the dreamers and their waking-up when they walked out into the lobby.”Footnote 49

With its official opening in January 1959 until its closure in 1963, the Living Theatre's Fourteenth Street Theater became a sanctuary for experimental dramatic art. In between such groundbreaking productions as Jack Gelber's harrowing “The Connection,” which depicts a den of heroin addicts, the theater became home to numerous poetry readings and musical performances. These events included influential talks on Antonin Artaud by M. C. Richards, who published the first English translation of Artaud's The Theater and its Double (1958); a concert venue for my parents’ early music ensemble, the Manhattan Consort (directed by LaNoue Davenport) for their 1959 concert series; and in January 1960, the featured location for a three-hour performance of Cage's one-minute Zen parables in which he manipulated “five tape recorders while David Tudor played the piano.”Footnote 50

Conclusion

For many of the artists at the Gatehill Cooperative, that early period—building their homes, collaborating and living together in a communal way, and developing their art—stands among the most productive and innovative of their careers. Indeed, despite the onslaught of new and substantial publications on Black Mountain College and major exhibitions of its famous faculty and students, it is significant to note that such luminaries as John Cage, M. C. Richards, Stan VanDerBeek, Karen Karnes, and David Tudor all reached the zenith of their careers not at Black Mountain but at Gatehill. Cage penned many of his best-known works there, including Winter Music (1957), Concert for Piano and Orchestra (1957–58), Fontana Mix (1958), Water Walk (1959), and Atlas Eclipticalis (1961), for which Paul Williams designed the mechanical conductor that replaced Leonard Bernstein in its premiere with the New York Philharmonic. Cage also attained a new level of fame with the publication of Silence (1961), which includes many Gatehill community members in its series of humorous anecdotes. Richards published her most famous book Centering (1964), which represents a culmination of her involvement with pottery and communal living at Gatehill. In 1965 VanDerBeek collaborated with Cage and Tudor on their interactive multi-media event Variations V, for which VanDerBeek provided an experimental film collage that included processed television images by Nam June Paik. The following year VanDerBeek drew international attention from the film world with the completion of his “Movie-Drome” at the Land, including a scheduled visit from participants of the 1966 New York Film Festival that included filmmakers Shirley Clarke and Andy Warhol. Living and working at her pottery at Gatehill over an astonishing twenty-five-year period (1954–79), Karnes gained commercial success with the development of flameproof clay and later achieved notoriety with her non-traditional approach to the centuries-old salt-glazing technique, producing “the most extraordinary body of saltwares since the pots of the magical Martin Brothers in Victorian London nearly a century earlier.”Footnote 51 And, finally, Tudor, who remained at the community until just before his death in 1996 (over forty years), produced practically his entire compositional oeuvre at Gatehill, for which he continues to garner international acclaim.

In retrospect, those first years at the Land were its most cohesive: the 1960s bringing difficult family breakups that led to the departure of many of the original Black Mountain members.Footnote 52 Yet, despite the impermanent nature of many of Gatehill's founders, the community itself continued to evolve with each generation of new members. Indeed, the Gatehill Cooperative, with all its many incarnations, still exists. “Perhaps,” as Paul Goodman reflects, in direct reference to Gatehill,

the very transitoriness of such intensely motivated intentional communities is part of their perfection. Disintegrating, they irradiate society with people who have been profoundly touched by the excitement of community life, who do not forget the advantages but try to realize them in new ways. People trained at defunct Black Mountain, North Carolina, now make a remarkable little village of craftsmen in Haverstraw, N.Y. (that houses some famous names in contemporary art). Perhaps these communities are like those “little magazines” and “little theaters” that do not outlive their first few performances, yet from them comes all the vitality of the next generation of everybody's literature.Footnote 53

Certainly, John Cage had been deeply affected by his experience there, continuing to hold a special place for Gatehill long after he moved away in 1972. In a way, he did finally return, as he chose to have his ashes scattered at the Land, joining with his own mother's ashes, among the trees, mushrooms, and woodland paths. All of this, of course, only made possible through the genuine good nature, vision, and quiet generosity of Paul Williams (Figure 19).

Figure 19. Paul Williams in his home at the Gatehill Cooperative, ca. 1960. Photograph by Betsy Williams. Courtesy of the author, Landkidzink Image Collection.