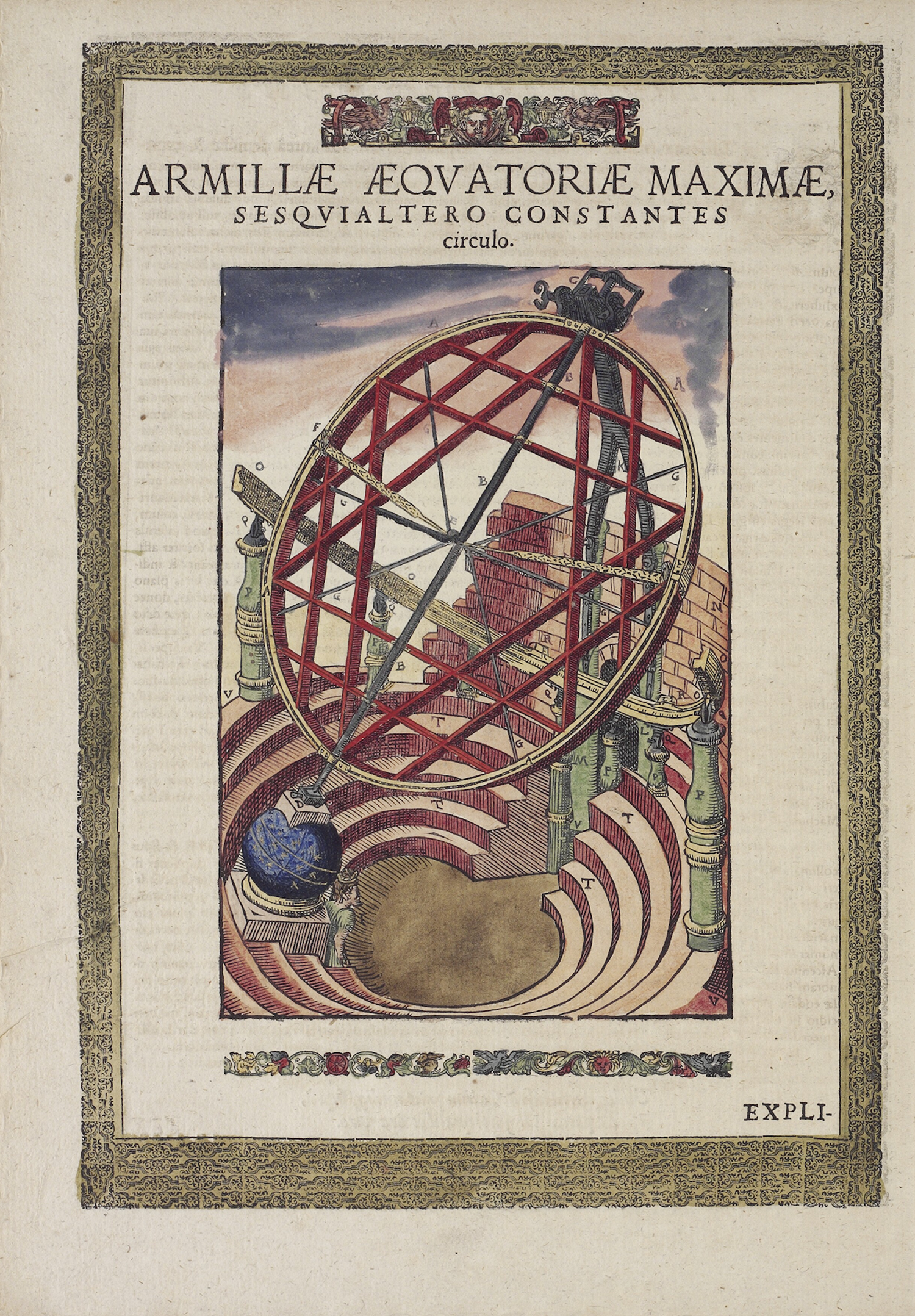

A hand-colored wood-block print from Tycho Brahe's Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Instruments of the renewed astronomy; 1598) prominently features an equatorial armillary depicted outdoors against a fading blue sky (see Figure 1).Footnote 1 The instrument is composed of two distinct parts. Taking up half the image, the gilded head—the upper, perfectly circular portion, which includes the armillae—has a shiny, metallic surface. The lower half is made up of a colorfully painted base with curling ornamental scrolls and two small figures that stand in dark niches. The decorative base, shown from a different perspective, supports the armillae in space. A thick black line outlines the edges of the picture, framing the instrument, which in turn is surmounted by a Latin inscription—“ARMILLAE AEQUATORIAE”—indicating the instrument's name. Below and above the pictured instrument, a decorative polychrome strip of floral and grotesque decoration provides emphasis, while a patterned decorative frame painted green contains the image on the page. The size of the instrument relative to the page, its careful framing, the clear inscription in majuscule script, the illumination, and the clear labeling of various parts lend an air of importance while also beckoning the viewer to inspect the colored print more closely.

Figure 1. Armillae aequatoriae (Equatorial armillary). Copperplate engraving on paper, water-soluble paint and gilt. All images are from Tycho Brahe, Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (Wandsbek, 1598). The National Library of Denmark and the University Library of the University of Copenhagen. Pictures used with permission from the Royal Library of Copenhagen.

The armillary and its description on the facing page is one of twenty-two prints of mathematical instruments featured in the Mechanica, an illuminated presentation treatise that Brahe produced in many copies and conferred upon selected individuals in the hopes of ultimately securing the patronage of Emperor Rudolf II. The treatise introduces the reader to novel instruments designed by the astronomer to observe and record precise cosmological phenomena as part of the instauration, or renewal, of astronomy.Footnote 2 Throughout the text, Brahe highlights his observational methods, which entailed repeated, accurate, and comprehensive planetary observations obtained through the aid of multiple, reliable, and more accurate mathematical instruments—the very same instruments featured in the text. As has been shown by Adam Mosley and others, Brahe's authority in astronomy rested on his instruments, which became central to his endeavor to renew astronomy.Footnote 3 Their unique and prominent presentation in the Mechanica, as woodcuts and engravings that are rendered with artistic forms and visual embellishments, demands an inquiry into their effect on Brahe's observationally driven program.Footnote 4

The centrality of Brahe's instruments to his credibility and to his pursuit of a renewal of astronomy has been studied, as has Brahe's ability to expertly and strategically manipulate the patron network by distributing images of his instruments in print (alongside his cosmological findings) while bringing together influential contacts to secure new patronage for his research.Footnote 5 Although it has been suggested that Brahe circulated images of his instruments in print to persuade readers of their reliability and, ultimately, to garner support for his cosmological findings, insufficient attention has been given to the images. Analyses often subordinate the visual to the textual. For instance, it has been argued that Brahe's extensive use of labeling helped establish his claims of accuracy and dependability by promoting smooth navigation between image and text, ultimately enhancing trust in Brahe's methods and instruments.Footnote 6 Beyond analyzing the images’ iconography and their function as aids to understanding Brahe's written descriptions, scholars have not adequately considered how the illuminated woodcuts and engravings may have functioned as pictures in their own right.Footnote 7 Given the Mechanica's considerable emphasis on illustrations alongside text, and relying on the copy of the Mechanica held by the Royal Library of Copenhagen, I propose that the colored images of Brahe's instruments demonstrated, articulated, and allowed the viewer to experience Brahe's observational methods firsthand.Footnote 8

The Mechanica was produced in 1598 to procure patronage after Brahe fell out of favor with Frederick II's successor, Christian IV, who withdrew support of Brahe's astronomical activity on the Island of Hven.Footnote 9 In 1597, in search of a new patron, Brahe departed Denmark along with his entire household. Stopping briefly at the castle of Wandsbek, Brahe quickly orchestrated the printing of the Mechanica at the hands of the Hamburg printer Philip von Ohrs. Brahe already possessed woodblocks of some instruments that had been used in earlier publications and in some of his correspondence, he thus commissioned four additional engravings.Footnote 10 The pages were quickly illuminated and bound, and copies of the Mechanica were selectively conferred on a network of colleagues and influential persons (many of whom were variously connected to the Prague court).Footnote 11 Before the Mechanica, no other astronomer had distributed a presentation copy containing such a complete account of instruments on such a wide scale.Footnote 12 By doing so, Brahe broadcasted a detailed account of his observationally derived astronomy based on instrumentation, thus ensuring that his methods and his instruments—the key tools of his science—would become a coveted addition at Rudolf's court, where the pursuit of knowledge was considered of great import.

Rudolf II was a renowned collector and patron of the arts who was fascinated with novelty and innovation.Footnote 13 The possibility of adding copies of Brahe's instruments to his extensive collection would have been a welcome prospect for the emperor, who already had numerous instrument makers in his employ.Footnote 14 In addition, filling the newly vacant post of imperial mathematician with someone of Brahe's repute and skill—someone who would produce cutting-edge work while under the emperor's protection, and in his name—also appealed to the emperor because it would increase the fame of his already renowned court and its artistic and scientific activity, which he patronized with fervor.Footnote 15 For someone of Rudolf's standing, patronage of astronomy, as a form of court technology, would garner him more social utility and power.Footnote 16 Rudolf likely wondered why the young Danish king had let Brahe slip away.

Although Brahe's authority as Europe's preeminent astronomer was contingent on his instruments, which were central to his observationally driven endeavor to renew astronomy, it was the strategically articulated images presented alongside the text that had initially captured the attention of recipients. Indeed, after receiving the Mechanica, along with two other manuscripts that contained important cosmological findings obtained through the aid of those same instruments, Rudolf II leafed through its pages late into the night.Footnote 17

Astronomiae Instauratae Mechanica

As its dedicatee, what might have impressed Rudolf II the most about the Mechanica? While the copy presented to Rudolf has been lost, we can assume that he received one of the more sumptuous examples. He likely appreciated its luxurious pale silk binding held together by metal clasps. Perhaps he pondered the painted likeness of Tycho Brahe that followed the frontispiece.Footnote 18 While it is unlikely that Rudolf read the entire book in one sitting, he likely read the four-page preface dedicated to him before admiring the twenty-two illuminated instruments and the painted engravings of Brahe's observatories.Footnote 19 Through the preface, the emperor would have been reminded that by promoting the study of astronomy—which in this context implied patronizing Brahe specifically—he would become the instrument through which God's glory on earth would be increased. His name and honor would be praised in perpetuity.Footnote 20

In the preface, Brahe, lays out his agenda for the Mechanica and justifies its focus on instrumentation; he outlines the astronomical practice Rudolf would be supporting. Highlighting the role of instruments in aiding vision, he explains that “in astronomy it is first of all necessary to obtain very many observations, taken over a long period of time by means of instruments that are not liable to error.”Footnote 21 He explains that using multiple, larger, more accurate, more dependable, and “more excellent” instruments will ensure that observations are “free of error.”Footnote 22 Brahe also adds that using several instruments requires the presence of six to eight researchers conducting experiments and taking measurements simultaneously.Footnote 23 Such an object-driven method would have appealed to Rudolf II, whose own collection of art and curiosities functioned as a research center in its own right.Footnote 24

Leafing through the pages of illuminated woodcuts and engravings, Rudolf would have certainly marveled at the unusual focus on images of instruments and their luxurious presentation, each taking up an entire page, with gilded components that would have sparkled in the candlelight. He may have read parts of the accompanying dense text to gain a better understanding of the function of those instruments that caught his eye. The frequent claims of their exclusivity—in terms of size, variety, accuracy, and dependability—likely engaged his interest, and while pondering their representations he may have hoped to witness a demonstration of their accuracy firsthand.

Rudolf was not the only recipient of the luxuriously presented Mechanica. Sources suggest that up to one hundred illuminated copies were distributed among Brahe's network of brokers, friends, and close contacts.Footnote 25 Through the carefully tailored dissemination of the illuminated account of his cutting-edge instruments, Brahe's goal was to impress and garner support in his search for patronage.Footnote 26 Even though the presentation of luxuriously illuminated treatises to potential patrons was by no means unusual, it was the number of presentation copies produced—which Brahe presented not only to patrons but also to colleagues and friends with connections at the imperial court in Prague—that set this presentation treatise apart.Footnote 27 In a culture of collecting, which celebrated material and aesthetic excess, the presentation of such a treatise—attributed to one of Europe's most distinguished astronomers—would have surely intrigued its erudite recipients.

Images of Instruments

Keeping the textual information offered by Brahe in mind, what might the prints of the illuminated instruments have conveyed? In the preface, Brahe explains that using several kinds of instruments to make the same observation improves accuracy, a notion that is emphasized visually through the organized, consistent, and recurrent presentation of his twenty-two instruments—eighteen woodblock prints and four engravings.Footnote 28 Each hand-colored print features a single instrument that occupies a simple space with a minimally articulated background. The majority of the images are oriented vertically within an ornamental green frame, which is thicker at bottom.Footnote 29 The frames and titles are identical to the Armillae aequatoriae, and the denoted function appears in seven prints (see Figure 1). The images also include labels in the form of letters of the alphabet, to which Brahe refers in the text. In the colored edition, depending on the copy of the Mechanica under investigation, the labels are at times obscured by dark illumination.

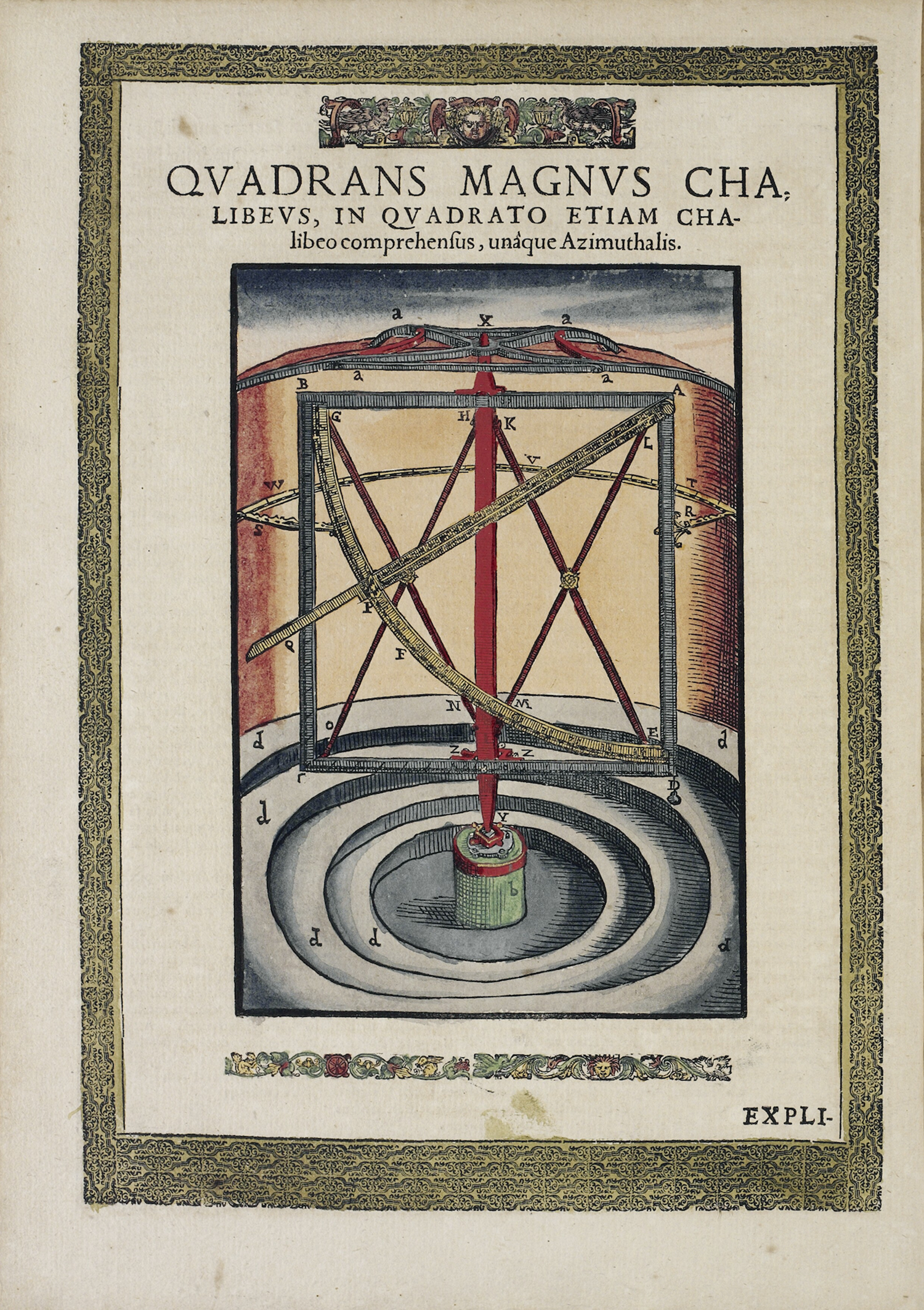

In terms of their context, the majority of the instruments are portrayed outdoors, set against a sky that changes from very light at the horizon to a dark blue in the upper portion of the picture plane. As a decorative function, the colored sky contextualizes the instruments, reminding the viewer of their use for measuring phenomena in the night sky. In the copy held by the Saxon State and University Library in Dresden, this function is emphasized through the addition of small shimmering stars.Footnote 30 In some prints, the outdoor setting is idealized through the addition of a green turf (see Figures 2 and 3, but in most cases the foreground consists of a nonspecific flat platform on which the instrument sits (see Figures 1, 4, 5, and 6).Footnote 31 In other instances, the platform takes on architectural elements that bring to mind the placement of these instruments inside crypts at Stjærneborg (see Figures 7, 8, and 9), where they are set simultaneously indoors and outdoors, giving the viewer full access to both.Footnote 32

Figure 2. Globus magnus orichalcicus (Great brass globe). Woodblock engraving on paper, water-soluble paint and gilt.

Figure 3. Quadrans minor orichalcicus inauratus (Small quadrant of brass). Copperplate engraving on paper, water-soluble paint and gilt.

Figure 4. Arcus bipartitus minoribus siderum distantiis inserviens (Bipartite arc for measuring angular distances). Woodblock engraving on paper, water soluble paint and gilt.

Figure 5. Sextans astronomicus, prout altitudinibus inservit (Astronomical sextant for measuring altitudes). Woodblock engraving on paper, water-soluble paint and gilt.

Figure 6. Quadrans alius orichalcicus etiam azimuthalis (Another azimuth quadrant of brass). Woodblock engraving on paper, water-soluble paint and gilt.

Figure 7. Quadrans magnus chalibeus, in quadrato etiam chalibeo comprehensus, unaquae azimuthalis (Great steel quadrant, inscribed in a square, also of steel, and revolving in azimuth). Woodblock engraving on paper, water-soluble paint and gilt.

Figure 8. Quadrans volubilis azimuthalis (Revolving azimuth quadrant). Woodblock engraving on paper, water-soluble paint and gilt.

Figure 9. Armillae aequatoriae maximae, sesquialtero constantes circulo (Great equatorial armillary instrument with one complete circle and one semicircle). Woodblock engraving on paper, water-soluble paint and gilt.

Embodied Viewing

While engagement with the images is maintained through a variety of minimally articulated settings that encourage the viewer to picture the instruments’ use for the observation of cosmological phenomena, viewer participation in the process of observation is achieved through a particular articulation of the instruments that does not always prioritize a naturalistic rendering.

Although the framing devices organize the viewing experience of the printed instruments, in certain prints a peculiar interplay between the heads and bodies of the instruments seems to disrupt their structured presentation. For instance, in the colored print of the Armillae aequatoriae, the head of the instrument bears the marks of minutes clearly inscribed on arcs that overlap and suggest volume (see Figure 1). Delineated through a balanced and symmetrical rendering, this brings to mind measurement, precision, and clarity—qualities associated with accurate observations, which are also invoked in the text that accompanies the image. Looking closely at the base, or the body of the armillary, note that the two supporting brackets, which are painted green (labeled “b”), appear to be oriented to the right, with the left-hand bracket partly obscuring the decorative edge of the red portion of the base that contains the two figures, effectively ruining the symmetry of the composition and causing a flattening effect. This is likely a design solution because showing the base perfectly perpendicular to the picture plane would have required strong foreshortening of the green brackets, which would have obscured certain labeled parts of the base from view altogether. Brahe reused certain blocks for the publication of the Mechanica, the print of the equatorial armillary being one of them; therefore, one might surmise that in the initial uncolored prints of the armillary, explaining the labeled parts of the instrument through text was favored over a naturalistic representation. In the colored version, that certain labels are nearly impossible to see because of the application of dark paint (such as the two “W”s and the two “X”s near the front of the picture plane) suggests that in the context of the Mechanica appealing to the senses may have been prioritized over fostering a clear understanding of the instruments’ construction and function.

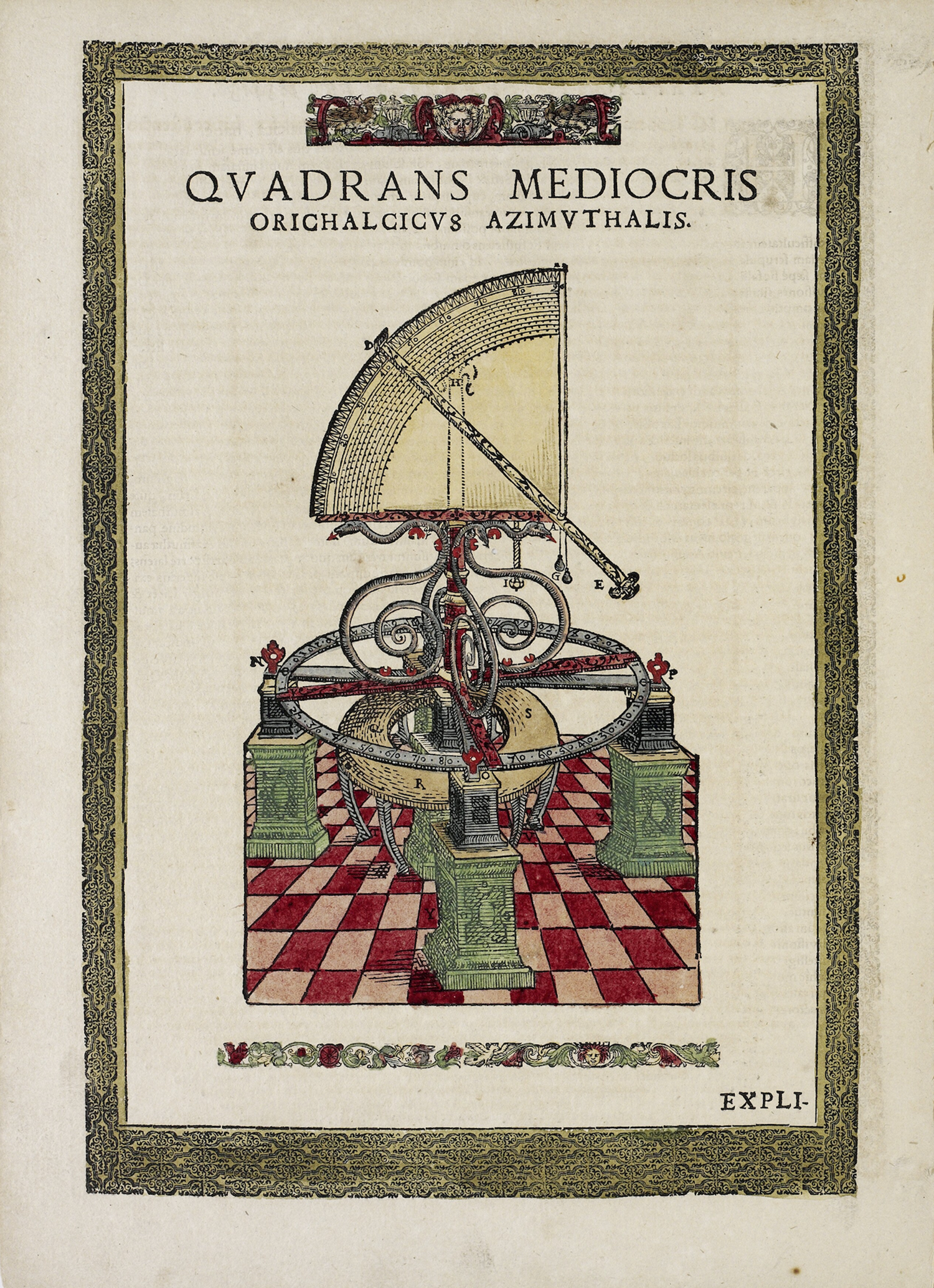

A similar effect of disjointedness seems to be at play in the image of the Quadrans mediocris orichalcicus azimuthalis (see Figure 10). The clearly delineated quadrant (or head of the instrument), painted with gold, is presented from the side and clearly shows carefully spaced out measurements along the circumference, with the alidade DE positioned to divide the quadrant in half. This again points to notions of order and precision that were so central to the use of the instrument. These notions are emphasized in the head and echoed in the text. Viewer access is again prioritized as our gaze is directed toward the bottom half of the instrument, past the scrolling serpents that facilitate the transfer of weight to the base. We can see the surface of the stool but not the top of the green plinths that support the quadrant. If they look closely, observers can see that the two plinths (labeled “Z” and “Y”) seem to be simultaneously parallel to and set at an oblique angle to the picture plane. The sharply receding orthogonals of the checkered floor also give the illusion that the instrument is being pushed toward the space of the observer, inviting close inspection. In both the armillary and quadrant discussed in the preceding text, the instruments encourage the viewer to consider the instruments closely, much as the astronomer would make careful, repetitive observations to obtain reliable measurements of celestial phenomena.

Figure 10. Quadrans mediocris orichalcicus azimuthalis (Medium sized azimuth quadrant of brass). Woodblock engraving on paper, water soluble paint and gilt.

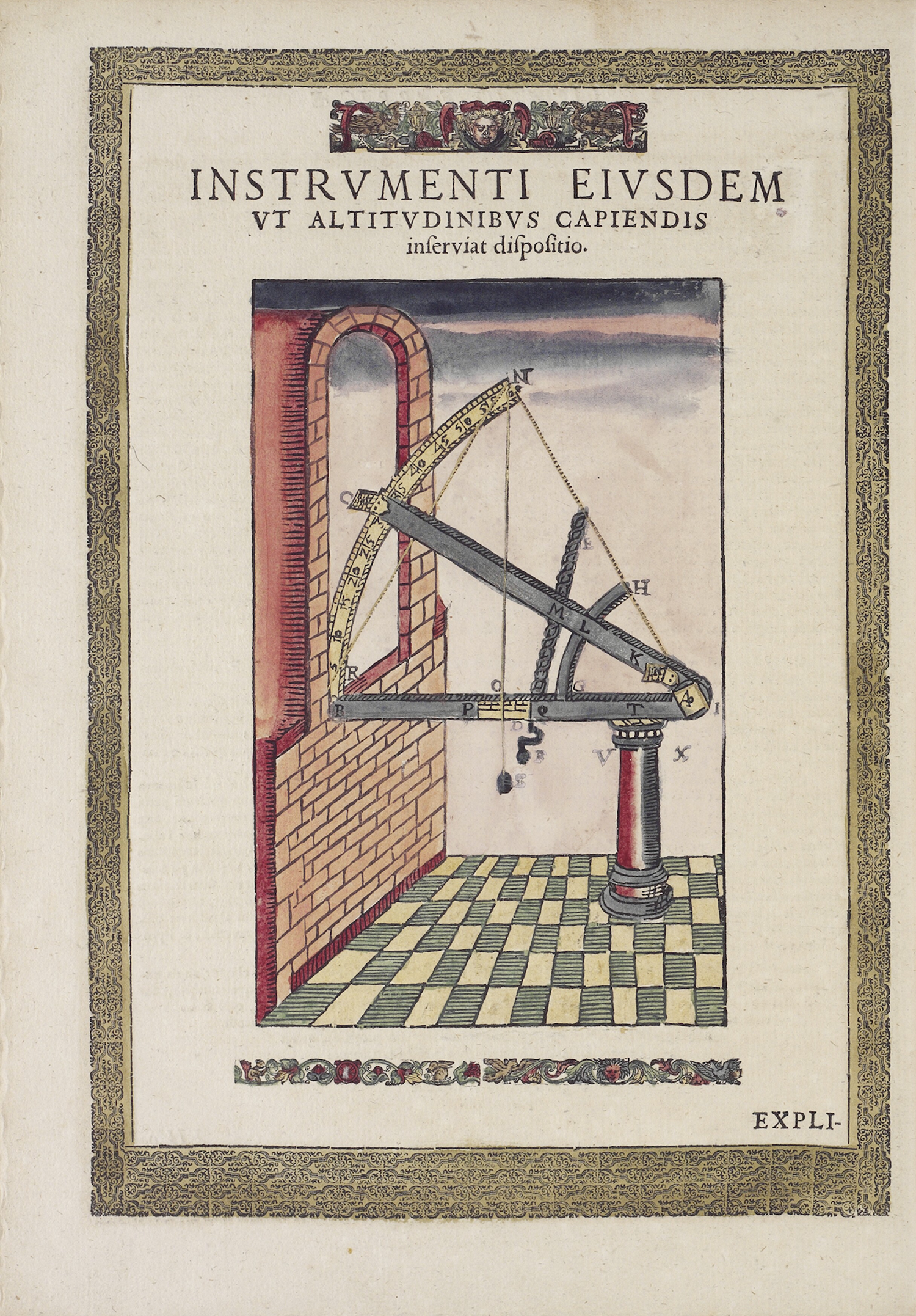

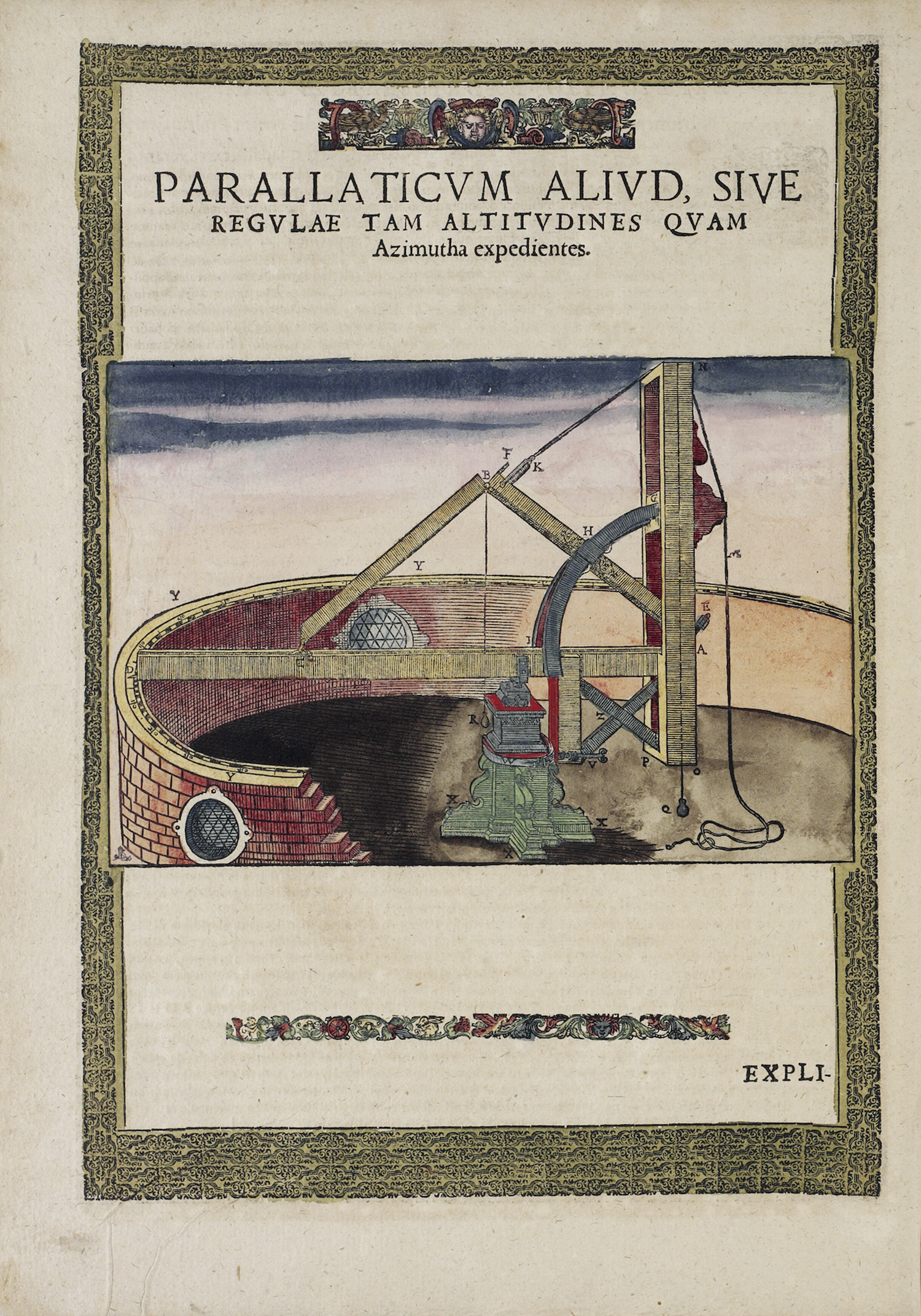

In other prints it is the architectural settings that seem to be awry. For instance, in Figure 11 a sextant for the observation of altitudes appears to be directed toward an arched window, the upper portion of which seems to be pushed toward the viewer. The instruments represented within a series of encircling steps display similar tendencies: see the Quadrans magnus chalibeus, Quadrans volubilas azimuthalis, and the Armilae aequatoriae maximae (Figures 7, 8, and 9). In all three cases, the circular steps appear to be compressed into the picture plane, suggesting that the instrument is bursting out of its enclosure because of its great size. And, indeed, these instruments, located at the Stjærneborg observatory, were very large to give greater resolution of arc in the degree of measurements.Footnote 33 In Figure 12, the enclosing wall around the parallitic or ruler-instrument (which has been partially dismantled in the image to provide access to the observer) appears to be leaning toward the viewer at the point where the bricks are exposed. Even in the print of Brahe's celebrated Globus magnus orichalcicus (see Figure 2), which Brahe commissioned for the Mechanica as a copper-plate engraving, the horizon (labeled “LMN”) appears to be sloping downward. Delineating it more naturalistically likely would have obscured the exact measurements, which are inscribed.

Figure 11. Instrumenti eiusdem ut altitudinibus capiendis inserviat dispositio (Mounting of the same instrument for observations of altitudes). Woodblock engraving on paper, water-soluble paint and gilt.

Figure 12. Parallaticum aliud, sive regulae tam altitudines quam azimutha expedientes (Another parallatic or ruler-instrument that shows the altitudes as well as azimuths). Woodblock engraving on paper, water-soluble paint and gilt.

Considering some of these choices, which to a modern viewer may come across as errors on the part of the draftsman responsible for the design of the woodblocks and copperplates, it is plausible that certain details were designed with less attention, especially because many of the prints were not initially intended for a presentation treatise. However, as discussed in the preceding text, most of the prints are designed to provide clear visual access to as much of the instrument as possible, especially to the parts of the instruments that contain measurements—components that are emphasized through illumination. Having their attention drawn to the instrument proper, viewers are encouraged to consider the instrument carefully, to focus on the part of the instrument that does the measuring, thus mimicking the action of the observer, who would use these instruments to make observations of the night sky.

Illuminated Instruments

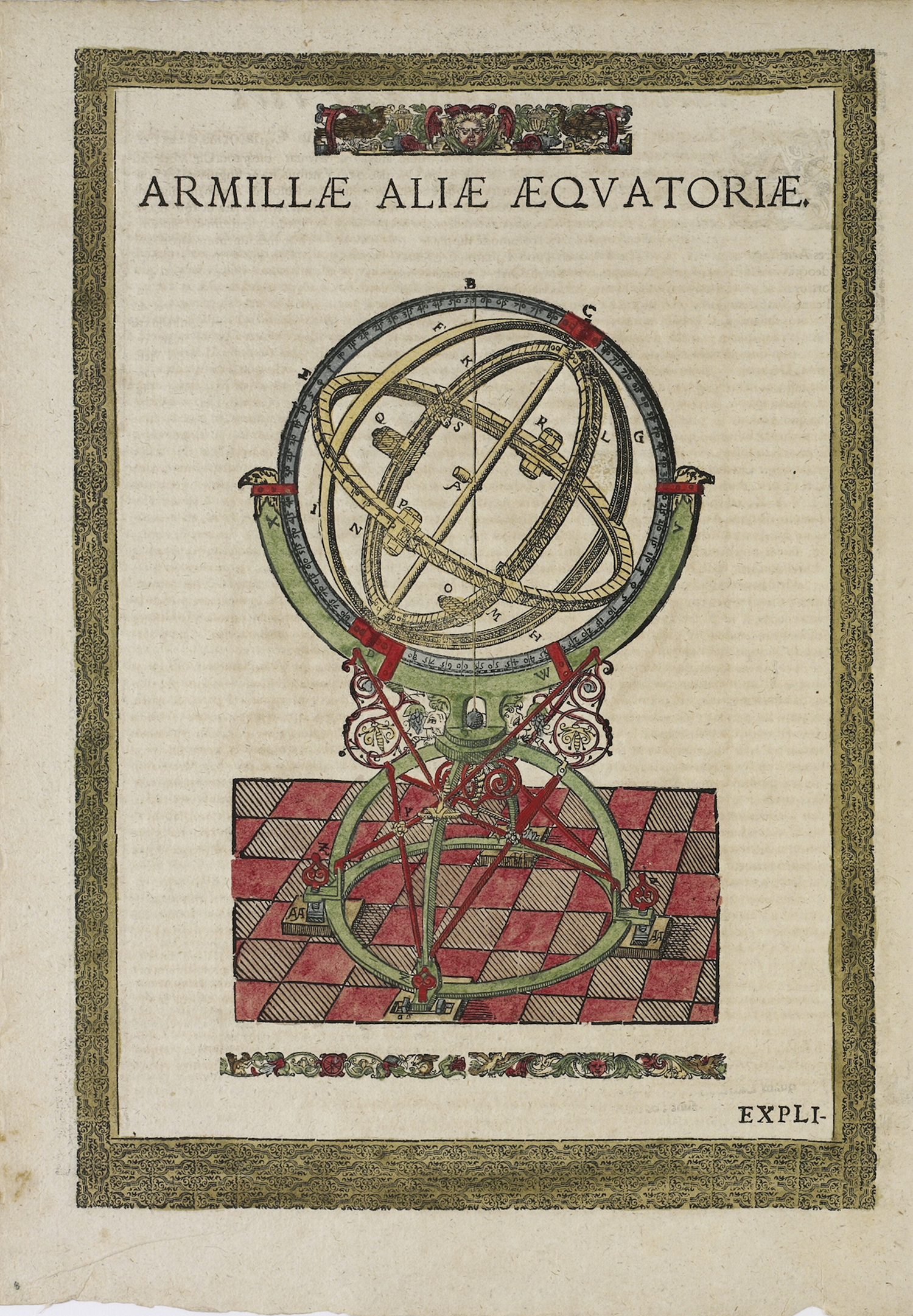

An important feature of these prints is that they are hand-painted using a colorful palate that includes gold. Recent studies on painted prints suggest that the addition of color to the medium of print was not simply a question of aesthetics.Footnote 34 In addition to creating a more luxurious effect, the colorful palate in the case of the Mechanica also creates contrast, which allows the viewer to more clearly visualize the different parts of the instruments. Gilding emphasizes the part of the instrument containing measurements while simultaneously bringing to mind the very materiality of the instrument in question, which, as Brahe explains, was often brass fitted. In many of the pictures, contrasting colors are used to differentiate between the head of the instrument and its base, such as in the print of the Sextans astronomicus, prout altitudinibus inservit, in which the sextant is painted red (with some parts in gold) and the base is painted green (see Figure 5). In Quadrans minor orichalcicus inauratus, the same colors are used not only to distinguish between the base of the instrument (green) and the plinth on which it rests (red) but also to bring out the instrument from the ground—a green mound (see Figure 3). In Quadrans alius orichalcicus etiam azimuthalis, red paint is added to the plinth in a manner that suggests marble veining (see Figure 6). In Armillae aliae aequatoriae, the use of color helps to bring out the base of the instrument (green), which would otherwise be less visible against the checkered ground (see Figure 13).

Figure 13. Armillae aliae aequatoriae (Another equatorial armillary instrument). Woodblock engraving on paper, water-soluble paint and gilt.

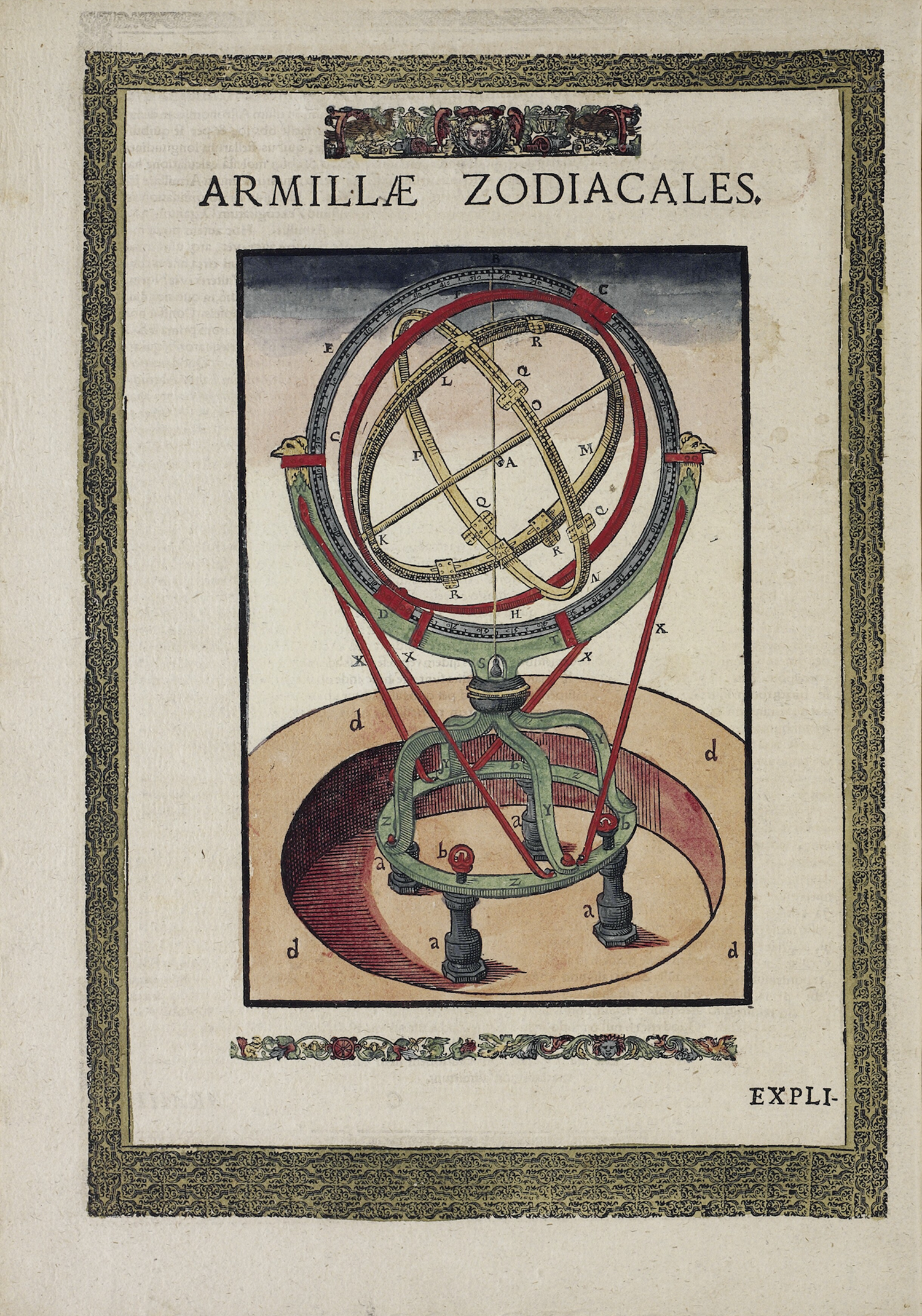

Color is also used to differentiate the finer details of the instruments, such as the armillary rings of the Armillae zodiacales, where one ring is painted red and the other gilt, while the meridian is grayish-blue (see Figure 14). Here, small rectangular shapes along the meridian are also painted a bright red, such as at points “C” and “D” (similar to what may be seen at points “F,” “S,” “R,” and “E” on the meridian of the Armillae aequatoriae , Figure 1).Footnote 35 In the copy held at the British Museum in London, illumination makes certain details more discernable, such as the small circular image labeled “K” and “L” in the Quadrans minor orichalcicus inauratus; however, this is not followed consistently because the same detail is not illuminated in the copy held at the Royal Library in Copenhagen.Footnote 36 In some cases the use of color in the background and foreground serves to situate the instruments indoors or outdoors, connecting them to the ground with a horizon. For instance, the Armillae aequatoriae and the Arcus bipartitus minoribus siderum distantiis inserviens stand on a darkly colored ground, painted brown (see Figures 1 and 4).Footnote 37 Color is also used to draw attention to certain decorative details and iconographic elements that would be hard to see otherwise and that are not discernible without Brahe's explanatory text.Footnote 38

Figure 14. Armillae zodiacales (Zodiacal armillary). Woodblock engraving on paper, water soluble-paint and gilt.

However, the illumination among the copies of the Mechanica is not uniform in terms of the colors used or in the attention paid to their application. For instance, the decorative borders around the prints vary: the copy held at Ludwig Maximilians-Universität in Munich and the London copy have green frames, while the Copenhagen copy is yellow.Footnote 39 There are also notable differences in the sky. For instance, in the London copy, the Globus magnus orichalcicus boasts a sky that is mostly blue, but swirls indicate clouds that turn light gray at the horizon, suggesting a stormy sky. In the Dresden copy, the blue of the sky is mixed with pink; it becomes lighter at the horizon, like a sky at dawn. In the Munich copy, the dark blue and pink above the instrument gradually turn to a light yellow that brightens at the horizon, like a sky at dawn on a summer's day. In the Copenhagen copy, the sky at the top of the image is the darkest of the four, with a suggestion of pink clouds that turn a pale yellow at the horizon (see Figure 2). Although this association of the color of the painted sky with the times of the day is subjective, the use of color nonetheless contributes to the overall experience of the images in a significant way. It reminds viewers of the instruments’ function as tools used for the observation of the heavens while making the pictures more interesting and visually pleasing.

Depending on the copy, there is significant range in the use of illumination. For example, in the Globus magnus orichalcicus, the illumination in the London copy includes yellow to emphasize a small plant that grows on a mound, whereas in the Dresden copy the plant is subsumed by the green of the foreground. Similarly, the signs of the zodiac on the globe are not differentiated in the latter as they are in the Copenhagen copy, the London copy, or the Munich copy. As pointed out earlier, the absolute legibility of the labels was not of key import: some labels are barely visible because of the application of dark illumination—another inconsistent detail among the copies of the Mechanica. In addition, the same instrument is often painted in different colors or shades. All these variations contribute to making each copy of the treatise unique.Footnote 40

Much could be said about the illumination, its process, and what it can tell us about the recipient of each copy. There is no doubt that illumination added to the Mechanica's overall aesthetic effect, making it more attractive to royal and noble collectors by giving the impression that each copy was luxurious and one of a kind.Footnote 41 But what is important here is that the hand-coloring had other, possibly unintended, consequences. The illumination creates contrast that clarifies parts of the instruments, allowing the viewer to more easily differentiate between components. The illuminated grounds, which augment the utopian character of the images, may also serve to remind viewers of the instruments’ ultimate function: to measure natural phenomena. The use of gilt on key parts alludes to and emphasizes the materiality of the prints’ referents, and more so than the suggested outdoor or indoor context of the instrument, it also augments the reality effect of the images, bringing to mind the metallic surface of the brass-plated instruments.

Picturing Methods: The Mural Quadrant

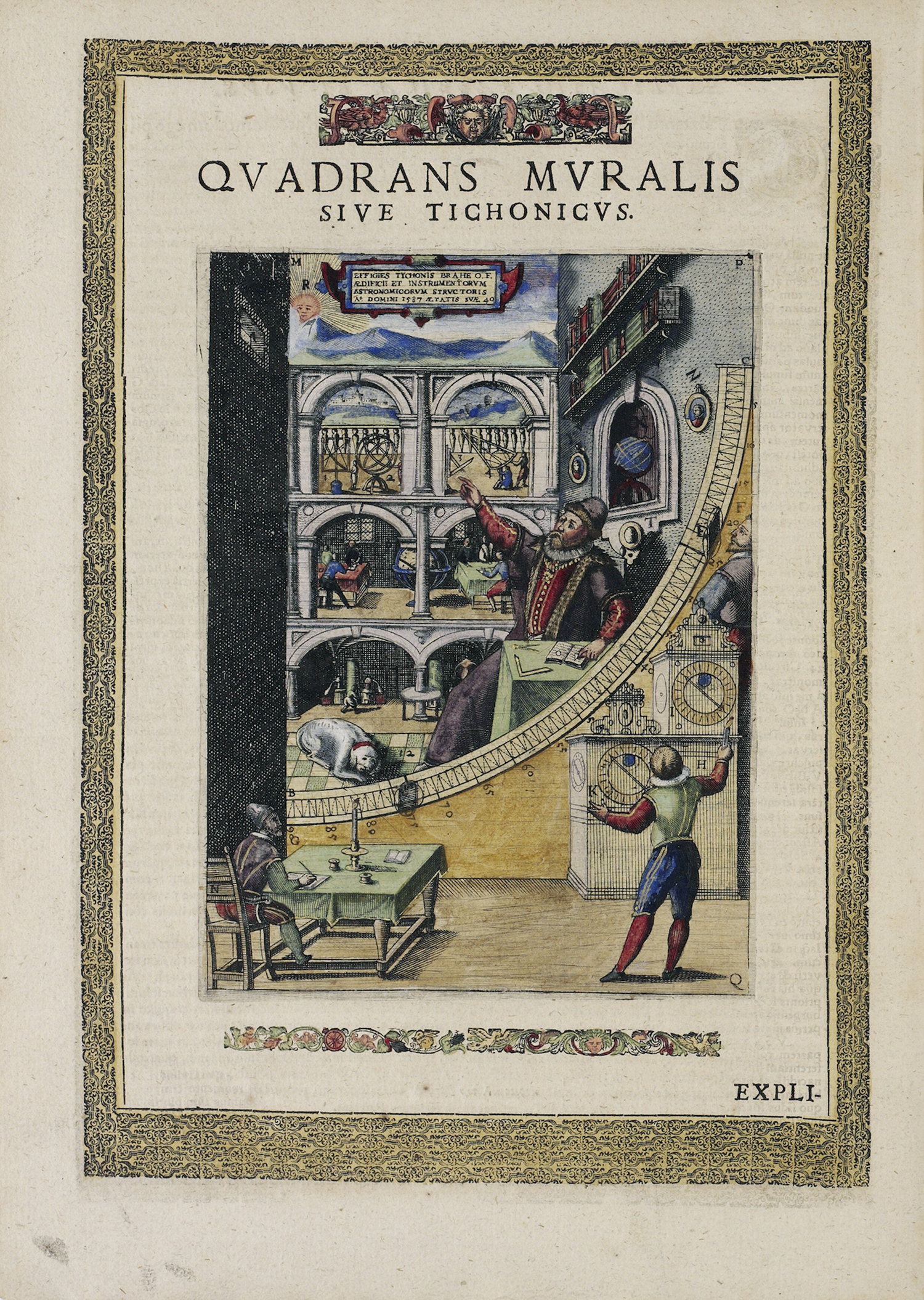

The majority of the illustrations direct viewers’ attention to the part of the instrument that does the measuring while also encouraging them to study the illustrated instruments attentively and repeatedly, like an astronomer who would observe the night sky. However, the engraving of the Quadrans muralis sive tichonicus (see Figure 15) offers something else: a visually narrated account of Brahe's observational method. It is the only print in the Mechanica to do so.

Figure 15. Quadrans muralis sive tichonicus (The mural, or tychonian quadrant). Copperplate engraving on paper, water-soluble paint and gilt.

As Brahe describes in the text, the engraving depicts the instrument as it once stood, fastened to a wall at the Uraniborg observatory on which was painted a mural that featured the astronomer himself.Footnote 42 In the print, the quadrant acts as a threshold that separates the foreground from the middle and background. In the foreground, three figures use the quadrant to obtain the longitude of stars as they pass the meridian: the observer on the right calls out the moment this happens, the timekeeper calls out the exact time, and the person at the desk writes it down.Footnote 43 Depicted from a higher vantage point, the picture behind the quadrant creates the illusion of extending the room, which culminates in tiered architectural views, a distant landscape, and an inscription.Footnote 44 Although Brahe notes in the accompanying text that the mural is “not quite relevant,” he goes to some lengths to describe it; clearly, it was an important component of the whole, and its representation in the Mechanica should be considered.Footnote 45

For Christianson, the mural demonstrates “that Tycho Brahe had created a research institute to probe the secrets of heaven and earth, and that the institute itself comprised a microcosm in harmony with the cosmos.”Footnote 46 Indeed, moving past the foreground, the viewer meets the the imposing likeness of Brahe. Attired in courtly dress, with partially gilded sleeves and buttons, and seated at a desk, his looming figure presiding over the space. The wall behind Brahe supports two shelves stacked with books, framed on either side by an oval portrait medallion. Beneath is a shallow niche containing a globe. Brahe tells us that the two medallions contain the portraits of King Fredrick II of Denmark and Queen Sophie and that the globe in the niche was a gift Brahe gave to their son and successor, Christian IV, when they visited Hven years ago.Footnote 47 The dog at his feet is, as Brahe mentions in the accompanying text, his most loyal dog.Footnote 48 Moving to the background, to the upper architectural level, which portrays an outdoor patio with a stone railing, we can see some of Brahe's instruments in the process of being used by observers. In the middle tier, we can see an indoor space separated by his great globe that includes a table on either side and Brahe's assistants working in collaboration. In the lowest tier is an underground laboratory that includes flasks, furnaces, and a single figure; it serves as a visual reminder of another of Brahe's interests: alchemy.Footnote 49 Much could be said about this image and its iconography in relation to the patron-client relationship, but what matters here is that Brahe hoped to convey that loyalty and patronage were key requisites for—and thus important components of—the instauration of astronomy.

But what of the action suggested by Brahe? Looking closely at the open book beneath Brahe's left hand we can see a gilt triangle and sphere, which represent the importance of mathematics. Beside the book lie two small gilded instruments, a compass and a ruler—typical instruments associated with astronomy. Brahe's gesture thus underlines the necessity of knowledge as presented in books by mathematicians and philosophers of the past. However, Brahe's simultaneous action of looking and pointing upward with his right index finger, toward the opening in the wall where measurements of the celestial bodies are being taken by the figures in the foreground, both parallels and supersedes the action of his left hand, suggesting that it is through the doing of it that astronomy will be made anew. Overall, the print articulates that under the direction of Tycho Brahe, and under royal patronage, an instauration of astronomy will be brought about through active observational work by multiple observers working together in collaboration—and using Brahe's many accurate instruments.

Conclusion

Intended as a presentation book for an elite clientele, the Mechanica set a new precedent for the publication of independent treatises devoted to a comprehensive description and illustration of mathematical instruments.Footnote 50 The textual component of the treatise offered a direct account of the instruments of Brahe's renewed and observationally grounded astronomy (based on the use of multiple accurate instruments and repeated observation and collaboration), while the printed and painted images of instruments embodied some of these very ideas.

For Brahe, repeated observation was the key requisite of astronomy, and the recipients of the Mechanica were asked to participate in the act of observation as they beheld its twenty-two woodblocks and engravings. Although one engraving, the Quadrans muralis, offered a didactic demonstration of Brahe's methods, the majority involve the viewer by asking them to observe the instruments carefully. By offering expanded access to the instruments and by juxtaposing colors and using gold to highlight the metallic nature of the most salient parts, the images draw the viewer to the main component of the instrument: the part that generates measurements. The illuminated prints of Brahe's instruments do not declare their purpose but instead ask the viewer to observe, to inspect closely and repeatedly, much like an astronomer noting measurements of the heavenly bodies.