In 1866, Benta and her daughter Benedicta sued Antonio Silva in the Municipal Court of Atibaia, in the province of São Paulo, Brazil (Figure 1)Footnote 1, asking for the legal recognition of their freedom. Although Benta and Benedicta lived as Silva's slaves, their legal status was unclear. Benta's master, Francisca das Chagas, had left in her will one quarter of Benta's value to Benta herself “for the benefit of her own freedom,” and three quarters of the property right in Benta to an heir, who later sold his share to Silva. If the master had left all of the property right in Benta to one of her heirs, or established a division leaving fractions of this right to multiple heirs, Benta's status would have been incontestable. A slave owned by one and a slave owned by many was still a slave. However, Benta had received part of her freedom. Moreover, Benedicta's status depended on the determination of her mother's status.Footnote 2

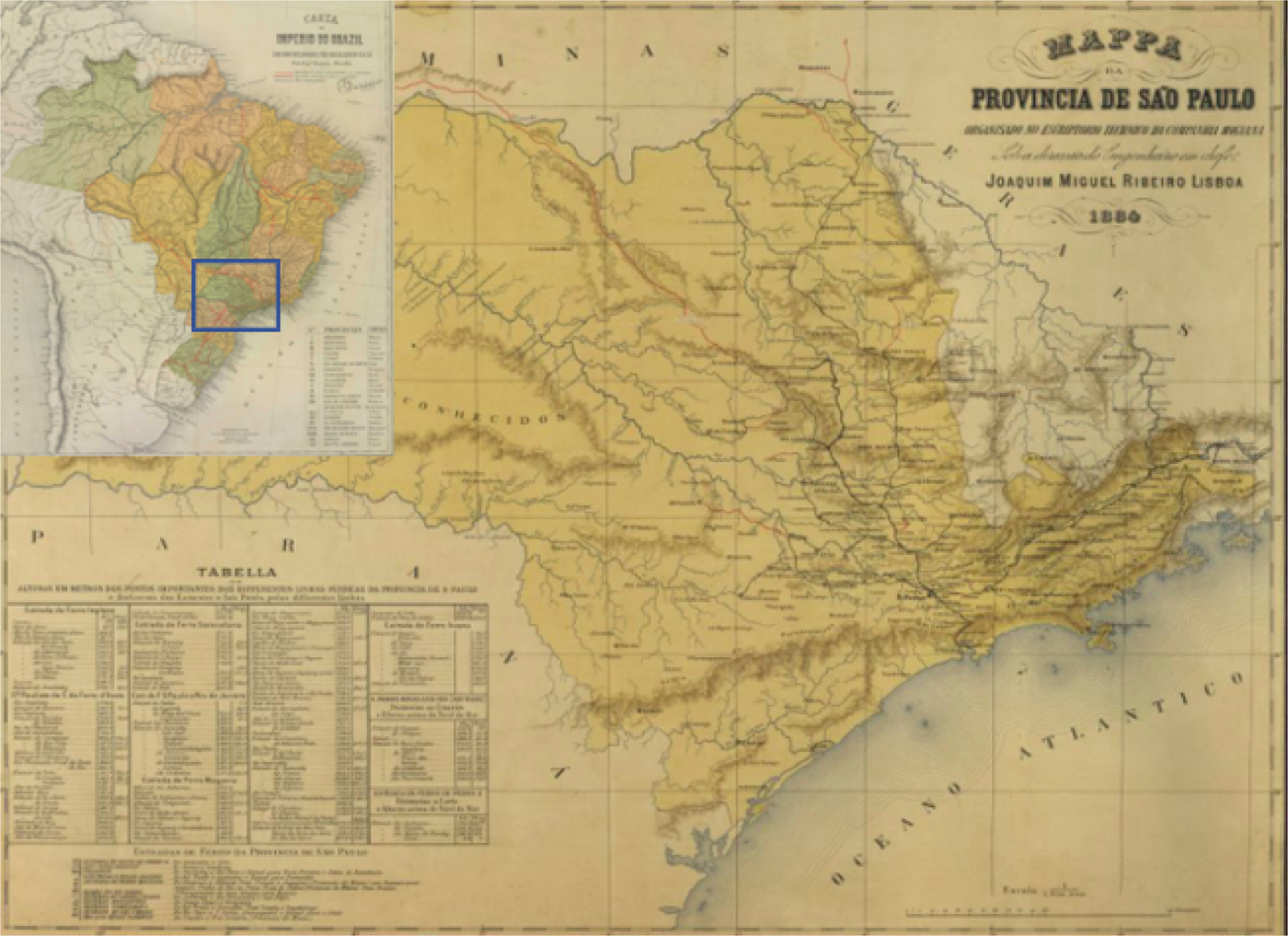

Figure 1. The Province of São Paulo, Brazil, circa 1886.

The Municipal Court's and the court of appeals’ (Tribunal da Relação) trial records, as well as complementary sources such as legislation, nineteenth century legal scholarship, and other similar status determination lawsuits, led us to explore different scales of Brazilian social and legal history. Narrowing the scale of observation reveals the story of a mother and daughter's fight for freedom in court, and how the law operated in practice in the judicial determination of their statuses. Moving up the scale, with the help of complementary sources, opens the possibility of new understandings about the relationship among slavery, law, and politics in postcolonial Brazil.Footnote 3

Atibaia was a small municipality that produced coffee, cotton, and some cattle.Footnote 4 It was located in the Southeastern coffee-growing region between the provinces of São Paulo, Minas Gerais, and Rio de Janeiro, known as the Vale do Paraíba (Figure 2)Footnote 5. In the mid-nineteenth century, the region's coffee plantations led the nation's export-based economy. They were part of the broader process that expanded modern slavery in Brazil, the United Sates, and Cuba, propelled by European industrialization and the consequent increase in global demands for coffee, cotton, and sugar.Footnote 6 In 1872, there were 1,200 slaves registered in Atibaia, out of 160,000 registered in the whole province of São Paulo.Footnote 7 Despite several recent proposals of gradual abolition, along with the international pressure coming from the British since independence in 1822 and boosted by emancipation in the United States in 1863, at the time Benta went to court slavery remained a strong foundation of Brazilian society.Footnote 8 Her judicial struggle against Silva was part of the widespread participation of slaves themselves in the delegitimation of slavery in Brazil.Footnote 9 However, it developed at the heart of a thriving slave-based economy, ruled by the entrenched interests of a small minority of land and slave owners.

Figure 2. The Vale do Paraíba region and the city of Atibaia, circa 1886.

Brazil had been a constitutional monarchy since 1822. The capital, Rio de Janeiro, and the two law schools, in São Paulo and Olinda/Recife, dominated the production of published legal doctrine.Footnote 10 Nonetheless, even in small municipalities, such as Atibaia, located 65 kilometers away from São Paulo, lawyers and judges contributed to the interpretation and development of Brazilian law. This decentralized production of law framed the Municipal Court's intervention in the relationship between Silva and Benta, and therefore in the institution that gave meaning to local social and racial hierarchies, and sustained Brazil's role in the Atlantic economy.

Independent Brazil was emerging as a nation-state ideologically committed to the liberal rule of law.Footnote 11 The 1824 Constitution protected liberty, individual security, and property, and established that judges were in charge of “applying the law.”Footnote 12 This official ideological commitment, efforts of codification, and the technical training and doctrinal production of jurists in numerous treatises and law review articles, indicate that Brazilian law was developing a relative autonomy from social and political structures.Footnote 13 Jurists themselves increasingly portrayed law as an autonomous scientific endeavor. Simultaneously, legislators and jurists translated liberal legal ideas that circulated across the Atlantic according to local political, social, and economic interests, mixing these ideas with colonial theories and principles of law.Footnote 14

In freedom suits, in order to make themselves convincing, instead of raising political claims about the legitimacy of slavery, lawyers had to show analytical skills in applying technical legal tools. The outcome of cases depended on the judges’ political views, but also on the lawyers’ ability to build juridical arguments that appeared to be scientific enough to convince the magistrate.Footnote 15 In Benta and Benedicta's case, the lawyers proposed technical solutions, based on those abovementioned translated and mixed legal ideas that favored each of their clients. Yet they did not ignore the politics of slavery. Instead of openly revealing their political views, lawyers and judges framed political arguments as questions about the court's institutional role, separation of powers, and natural law. Their arguments cast light on how the daily practice of law impacted the elaboration of Brazil's first gradual abolition statute in 1871, and the debates about the codification of national civil law.

A Nineteenth-Century Freedom Suit

Antonio Silva was presumably not surprised when, in February of 1866, he was notified to appear before the municipal judge of Atibaia for a hearing concerning the woman he called his slave, Benta. Silva had purchased three quarters of the property right in Benta from one of Chagas's heirs, and was aware that Benta had received the remaining one quarter of her value for the benefit of her own freedom. Since the 1850s, freedom suits were proliferating in Brazilian courts and Benta's ambiguous status almost called out for judicial settlement.Footnote 16

Once she had decided to challenge Silva, Benta needed someone to represent her and her daughter in court. Although they were often parties to lawsuits in Brazil, slaves had limited rights of action: they could be plaintiffs and defendants in certain kinds of judicial procedures as long as a guardian (curador) represented them in court. This requirement did not mean that slaves lacked standing.Footnote 17 It meant that they needed representation for the exercise of their right of action, as with other “incapable persons” such as children.Footnote 18 The guardian could either also act as the slave's attorney or appoint someone else to do it. The need for representation was a limitation because slaves often had to negotiate or pay someone to represent them; however, Brazilian jurists considered it a way to protect slaves’ rights. As slaves were seen as “incapable” and unable to fully express their will (vontade), they needed someone to speak for them in order to guarantee a proper defense of their interests in court.Footnote 19

The controversial local lawyer Carlos Alvarez da Cruz accepted the challenge of representing Benta and her daughter. Cruz was an active lawyer at the Municipal Court and a personal enemy of local abolitionist Antonio Bento. In 1871, when Bento became the municipal judge, Cruz allegedly tried to kill him. Cruz had been convicted of fraud and Bento revoked his license to practice law, which triggered an exchange of denunciations between them.Footnote 20 Historian Keila Grinberg has shown that throughout the nineteenth century, at the Court of Appeals in Rio de Janeiro, the most active lawyers represented both masters and slaves, making it impossible to assert that they were political militants on either side of the abolitionist debate.Footnote 21 Although Bento openly voiced his abolitionist ideas, and even decided cases explicitly based on his politics, Cruz was probably among those professional lawyers who practiced law independently of their political views.

Cruz's first move was to file a deposit suit (ação de depósito), requesting the removal of Benta and Benedicta from Silva's control. Nineteenth century Brazilian jurists argued that the deposit of an alleged slave involved in a freedom suit should be done “for the sake of his safety, and the liberty of his defense.”Footnote 22 The deposit thus protected slaves from being punished for the boldness of going to court against their masters. This same rationale applied to children and women when they sued their parents or husbands, respectively. In Atibaia, mother and daughter were deposited under the protection of Cruz himself. For Silva's lawyer, José de Medeiros, the deposit created an “abnormal and anarchical state” in which a man was unable to use his own property.Footnote 23 For Benta and Benedicta, it created the practical conditions for confronting the legality of Silva's dominion over their lives.Footnote 24 A status determination lawsuit usually followed the deposit and, although some procedural issues protracted this development, Benta's case went down the usual procedural path. After the deposit, Cruz initiated a freedom suit (ação de liberdade), asking for the legal recognition of his clients’ freedom.

Slaves’ ability to contest their status judicially in freedom suits reveals that the law of slavery simultaneously turned human beings into property while opening paths for freedom.Footnote 25 Slaves were aware of these paths and frequently used the courts to advance their own conceptions of freedom, and eventually to become free.Footnote 26 Status determination lawsuits had existed at least since the eighteenth century, when Brazil was still a colony of Portugal.Footnote 27 Later, during the second half of the nineteenth century, some activist lawyers and judges turned the judicial system into an arena of debates about the legitimacy of slavery. Slave litigation substantially intertwined with abolitionist political ideas and struggles, especially in the 1880s, when lawyers such as Cruz's personal enemy Bento adopted legal mobilization as a strategy against slavery.Footnote 28

Viewed through those procedural and political perspectives, Benta and Benedicta's case resembles other freedom suits that reached Rio de Janeiro's court of appeals during the mid- nineteenth century.Footnote 29 It thus provides evidence for the study of both the ways in which slaves had access to courts and the political significance of their judicial endeavors. When analyzed through a substantive legal perspective, their case provides further insights into the dimensions of slavery law that blurred the lines between the law of persons and property law, into the ways in which freedom could be legally translated, and into the types of arguments available to lawyers in nineteenth-century Brazil. Although the case was simple in procedural terms, it posed a substantial problem to the law of slavery, which was undergoing significant transformations in the nineteenth century.

Slavery and the Transformation of Brazilian Law

Between the end of the eighteenth and throughout the nineteenth century, normative orders based on the European ius commune underwent radical transformations. The ius commune was the amalgam of interpretations of canon and Roman law that had regulated territories under European jurisdiction since approximately the end of the eleventh century.Footnote 30 In a nutshell, the ius commune assumed that there was a natural order to the world, which structured the statuses of persons and things. Legal doctrine supposedly interpreted this natural order and guaranteed its conservation. But with the strengthening of liberal ideas across the Atlantic at the end of the eighteenth century, other conceptions of law had gained space. Law acquired formalistic and subjectivist characters. It was increasingly conceived as a bundle of norms enacted by the state and as a system for the protection of subjective rights.Footnote 31 These transformations impacted the normative systems that regulated persons and things: the two foundations of the law of slavery.

After independence, Brazilian jurists sought to adapt colonial law to this new formalistic and subjectivist normative order. For the law of persons, this transition meant adapting the ius commune theory of status—largely based on interpretations of Roman law—to the liberal ideas of personhood and civil capacity. According to the theory of status, a “person” was someone who had a “status,” which granted him or her a specific set of prerogatives and privileges. The status could be either natural or civil. Natural status originated from the “essential nature of beings” and civil status was rooted in civil law norms. Civil law distinguished people's civil status in relation to freedom, the city, and the family. Regarding freedom, one could be either a slave or a free person. Slaves were, therefore, natural persons who had lost their “freedom status.”Footnote 32

A legal order structured by the idea of subjective rights was not entirely compatible with the theory of status. Whereas liberal legal thinking presupposed the isolated individual as a holder of subjective rights, status was an ascribed position within a particular social group, such as the family. In the transitional years of the nineteenth century, the Brazilian jurists’ compromise solution was to use the theory of status to categorize legal persons and justify the difference in the acquisition of rights among them. They filtered the ius commune theory through the language of civil capacity theory, a modern doctrinal construction. According to this modern theory, civil capacity could be “of law” or “of fact.” Civil capacity of law (capacidade civil de direito) was the ability to acquire rights and to exercise—by oneself or through another person—acts not prohibited by law. Because every human being was capable of acquiring rights, everyone had civil capacity of law. Civil capacity of fact (capacidade civil de fato) was the ability to exercise juridical acts, which could be limited by law. Thus, a person could acquire a right, and yet be lawfully barred from exercising it. This depended on the person's ability to express will. Minors, married women, slaves, and people with mental disabilities did not have full civil capacity of fact, despite having civil capacity of law.Footnote 33

Brazilian jurists combined the old theory of status and the new civil capacity theory in determining slaves’ legal status. They argued that, according to the theory of status, legal persons were divided into slaves and free people. Slaves were legal persons with limited civil capacity to acquire and exercise rights. Jurists thus used the ius commune's classification of people's statuses to justify the unequal distribution of subjective rights in a society in which slavery was deeply rooted as a marker of social and racial hierarchies and as the foundation of economic production.Footnote 34 This process of translating modern legal ideas according to local political, economic, and social interests was characteristic of the coexistence between liberalism and slavery in postcolonial Brazil.

Civil capacity theory also changed how slaves accessed courts. During the eighteenth century, under the ius commune, representation by a guardian was not mandatory. Although guardians existed to protect people considered vulnerable or impoverished they were generally absent in freedom suits.Footnote 35 Under civil capacity theory, guardians were mandatory because people lacking civil capacity of fact were unable to express their will. Instead of an exceptional situation regarding the person's living conditions, inability to express will referred to an internal incapacitating feature, which could be remedied only by representation. In Atibaia, Silva's lawyer, Medeiros, argued that the trial could not continue without a proper guardian, in a failed attempt to undermine the lawsuit. Yet, he also referred to Benta and Benedicta as “miserable persons,” therefore navigating between this colonial vocabulary and the liberal theory of will.Footnote 36

Parallel to the transformations in the law of status, property law also went through profound changes across the Atlantic World during the nineteenth century.Footnote 37 New legal frameworks emerged to define the rights and obligations attached to property, and therefore to human property as well. In Brazil, legislation and legal scholarship pushed property law toward the recognition of an abstract right to individual ownership. The ius commune legal framework did not uphold the idea of property as a subjective right. Because the notions of utility, effectiveness, and the maintenance of a natural order guided the ius commune, the acquisition and protection of rights over things were conditioned on the actual exercise of ownership powers. Owners remained owners as long as they exercised possession over their property. Brazilian jurists sought to turn ownership into an abstract concept without a necessary connection to the concreteness of the exercise of possession. An owner was a legal subject, preferably identified by an individual title deed.Footnote 38 In nineteenth century Brazil, when jurists debated reforms in property law, they had both land and slave property in mind.Footnote 39 It was impossible to disentangle these two forms of ownership. The imperial government implemented land policies considering the availability of slave labor, and the regulation of slavery was tied to the expansion of agrarian frontiers.Footnote 40

By 1866, when Benta went to court, Brazilian politicians and jurists were discussing the new frameworks of the law of persons and property law. Debates took place in Parliament, the State Council (Conselho de Estado), and the Institute of Brazilian Lawyers (IAB), in Rio de Janeiro, and in the São Paulo and Recife law schools.Footnote 41 Ideas produced in those forums circulated in law reviews, legal treatises, and newspapers. In those academic and political forums and media, Brazil's legal-political elites increasingly depicted law as a scientific endeavor and a crucial part of the construction of a national identity.Footnote 42

The regulation of status and property relied on an extensive collection of colonial ordinances, statutes, and decrees, combined with Roman law and the 1824 Constitution. The modernizing impulse of the Marquis of Pombal's eighteenth century colonial reforms had set in motion the systematization of colonial law. Pombal's reforms had aimed at building a modern and rational legal system to strengthen the Portuguese imperial economy. To consolidate Portuguese law, Pombal had established new standards for legal interpretation through the 1769 Law of Good Reason and the Statutes of the University of Coimbra, issued in 1772. The Law of Good Reason defined the sources of Portuguese law as national legislation, higher court decisions, and customs. Roman law was a subsidiary source, enforced only when it was in accordance with “good reason.” The law defined this vague concept based on the principles of divine law, natural law, and the law of nations. The Statutes of the University of Coimbra, in turn, reformed legal education, directing it to the study of national Portuguese law. They also established the appropriate procedures for identifying which Roman law norms were in accordance with “good reason.”Footnote 43

After independence in 1822, the monarchy renewed its efforts of systematization and consolidation as part of an agenda to build national unity. In 1859, the minister of justice hired Augusto Teixeira de Freitas to write a draft civil code to unify, systematize, and legitimize the national regulation of private relations, but the project was frozen after Freitas terminated his contract in 1867.Footnote 44 Despite the absence of a civil code, in judicial and ministerial decisions, legal treatises, law reviews, and debates at the IAB and the law schools, men informally and formally trained in law tried to systematize and clarify what that heterogeneous body of legal sources said about the status of slaves and slave property.Footnote 45

Legal doctrine played an important role as an instrument of identification, selection, and dissemination of law. After independence, jurists took on the task of determining which ius commune norms were compatible with national law and what they considered to be natural law and the principles of “civilized nations.” When the authors of legal treatises, commentaries, and law review articles adapted the pre-existing legal framework to liberal legal principles, they did more than produce academic legal thinking. Nineteenth-century legal doctrine shaped what was considered to be valid law, applied in administrative practice and courts. It was not only informative, but also constitutive of Brazilian law.Footnote 46As some jurists were active participants in political debates about slavery, historians have characteristically portrayed late-nineteenth-century legal arguments and judicial decisions as being largely dependent on political views.Footnote 47 Although this was probably true for many freedom suits, it does not mean that political ideas completely determined all cases and debates. Whereas some of them condemned slavery for being contrary to the advancement of “civilization,” other Brazilian jurists defended a rationalistic conception of law as science, separate from politics.Footnote 48 In 1863, for example, when Agostinho Marques Perdigão Malheiro, an influent jurist very close to Emperor D. Pedro II, spoke to the members of the IAB in defense of gradual emancipation, he also claimed that Brazil should have a code “similar to the modern Codes of civilized nations, and in accordance with the principles of science.”Footnote 49 A few years later, he claimed that the law should be a “harmonic whole,” suggesting that it could be free from internal contradictions.Footnote 50

Nineteenth-century transformations in the law of persons and property law changed the legal bases of Brazilian slavery. In their efforts to translate liberal theories of law to their political and social context, some Brazilian jurists contributed to the legitimation of slavery. The predominant legal thinking, which portrayed law as a scientific endeavor, framed how lawyers presented their cases in freedom suits. Discussing slavery in technical legal terms may have also contributed to its legitimation. Both the translation of liberal theories and the supposedly technical-scientific legal determination of people's statuses inserted slavery into an imagined rational and harmonic normative system that was independent from politics and social hierarchies. However, on the other hand, technical arguments could also play the strategic role of convincing judges that someone who had been living as a slave was in fact legally free. As social historians have argued, the aggregation of litigation aimed at achieving this goal contributed to the delegitimation of slavery in Brazil.

The Meaning of Property: Co-owned Slaves

In her testament, Chagas had left “one quarter of the value of the slave named Benta for the benefit of her own freedom.”Footnote 51 One can speculate as to whether Benta and Chagas had developed some degree of affection in their relationship, or if Chagas decided to clear her conscience and obtain religious redemption by being benevolent to her slave.Footnote 52 Benta could also have acted strategically in adapting to the circumstances of captivity and showing zeal for her master's well-being in order to increase her chances of manumission.Footnote 53 The latter hypothesis suits Benta's strategic behavior in getting a lawyer to represent her in court a few years later. In any case, nonetheless, whereas Chagas’ testament completely and unequivocally manumitted a slave named Antonio, it did not grant Benta the same treatment.

Benta's lawyer, Cruz, framed the case based on the liberal idea, nonexistent under the ius commune, that an “object” could be divided into multiple fractions of individualized ownership. For him, Chagas's testament had created a situation of co-ownership (copropriedade). Although the document did not make express reference to this concept or to the equivalent notion of condominium (condomínio), it had made Benta co-owner of herself. However, because freedom was indivisible, the co-proprietors could not simultaneously exercise the rights attached to ownership, such as possession and enjoyment. Therefore, Benta should possess and enjoy her freedom, and compensate Silva for his share of ownership. Defending Silva's interests, Medeiros framed the case differently, evoking the colonial notion of dominium of masters over their slaves. He emphasized that Chagas's dominium, her power over Benta, extended beyond the master's death. According to him, “the deceased's will” was not to free Benta. Otherwise, she would have made it clear, as she had done regarding the slave Antonio. Instead, Benta had become a slave in a privileged position, benefited with a quarter of her value.Footnote 54

Almost half a century after independence, parts of the Phillipine Ordinances, a compilation of norms enacted by King Phillipe III of Spain in 1603 during the Iberian Union (1580–1640), were still valid law in Brazil.Footnote 55 Book IV, title 96, §5° of the Ordinances referred to the existence of slaves in condominium. It stated that when heirs inherited indivisible property, they should sell it or rent it and divide the earnings.Footnote 56 Brazilian jurists developed different interpretations for that situation. If one of the owners freed a part of the slave or the slave him- or herself bought part of his or her freedom, Lourenço Trigo de Loureiro, professor at Olinda/Recife Law School, argued that the slave was in a “state of imperfect freedom.”Footnote 57 Perdigão Malheiro believed that if a co-owner freed a slave in his or her share, the slave became free, because it was “absurd for someone to be part free, and part slave.”Footnote 58 The other co-owners, therefore, had to accept reparations equivalent to their quotas of slave property.Footnote 59 Against Malheiro, Freitas, who had been put in charge of writing a draft civil code, defended a tougher regulation of the manumission of slaves in condominium. To him, manumission was valid only when and if the other co-owners also conferred it.Footnote 60

Recent national law also played a role in legally framing the situation of co-owned slaves. The State Council, which assisted the emperor in enacting decrees for the “good execution of laws,” had already acted on the issue. Aligned with Freitas’ position, a March 18, 1854 State Council resolution determined that if any heir disagreed, a co-owned slave could not be manumitted.Footnote 61 In turn, Antonio Joaquim Ribas, a professor at the São Paulo Law School, and Malheiro argued that the best solution was to apply a September 20, 1823 provision, which obligated the heirs to accept the appraised value of a slave to purchase his or her freedom.Footnote 62

Assuming that slaves freed by one co-owner were free, the question remained regarding who should compensate the other co-owners. Malheiro and Ribas did not have clear positions on the matter. The provision they evoked did not provide answers. Civil law regulations indicated that the co-owner who opted for the extinction of the condominium was responsible for compensating the other co-owners.Footnote 63 The Phillipine Ordinances (book IV, title 96, §5°) stated that the burden of the transaction should fall upon the co-owner, not the slave.

In courts, lawyers and judges sought solutions for concrete cases. For example, also in 1866, the general curator of orphans (Curador Geral dos Órfãos) filed a petition before the municipal judge of Itajubá, in the neighboring province of Minas Gerais, arguing that João do Carmo had illegally sold a freedwoman named Francisca. After inheriting Francisca's mother, João, his wife, Maria d'Oliveira, and his mother-in-law, Anna da Silva, together owned Francisca and her siblings in condominium. In January 1866, however, Anna had decided to free Francisca in her share of property. Citing Malheiro, the judge of Itajubá ruled that Francisca was free because it was absurd for a person to be “part free, and part slave.” Nonetheless, the judge ruled that João had the right to sue Anna for the restitution of his share in Francisca.Footnote 64

Benta's case added further complexity to the issue. Whereas property law translated the fiction of a divided body into shares of ownership in condominium, the law of persons did not recognize individuals as one-quarter free and three-quarters slave. Moreover, Benta could be legally portrayed as the owner of part of herself. There was a disjuncture between the frameworks that organized Brazilian slavery law; a tension that national jurists had not anticipated. Although they sought a unified and harmonic legal science that would allow logical deductions to be rationally deployed in the solution of legal problems, it proved impossible to reduce the social world in which they lived to treatises, legislation, and codes.

The Meaning of Freedom I: To Possess Oneself

What did it mean for Benta to receive part of her value? According to her lawyer, Cruz, it meant that she was free, albeit with an obligation to compensate Silva for the three quarters of property right that he owned in her. Cruz asked the judge, first, to recognize Benta's and her daughter's freedom and, second, to order an evaluation of Benta's price and services. As she had been free since Chagas's death, the services she had performed for Silva should count toward the compensation of his property share. For Silva's lawyer, Medeiros, Benta's situation meant that she was a slave with the right to pay for her freedom. He argued that although Benta had a right to become free (direito à liberdade), she did not have a right to be free (direito de liberdade).Footnote 65

Benta's right to become free meant that her manumission was conditioned on the payment of three quarters of her value. The practice of granting conditional manumission (alforria condicional) was common in nineteenth-century Brazil.Footnote 66 Similarly, although not regulated by colonial legislation, the practice of coartação—a kind of manumission conditioned on the payment of previously agreed installments—had developed as a widespread practice during the eighteenth century.Footnote 67 In written law, the 1603 Phillipine Ordinances, which regulated manumission as a form of donation, referred to the existence of conditional freedom.Footnote 68 However, the Ordinances left the question of status unanswered.

Similar problems existed across the Americas. For example, since the sixteenth century, the custom of coartación had generated conflicting interpretations in Cuba. Coartación consisted of the agreement between master and slave on a price to be paid by the latter, in installments, to purchase his or her freedom. After a slave had partially purchased him or herself, it was unclear whether she or he was to be treated primarily as a freedperson, as a slave under his or her master's complete dominium, or as a slave partially in control of his or her time and labor. Even after 1842, when Article 34 of the Reglamento de Esclavos established that masters could not deny coartación to slaves who offered at least 50 pesos more toward their price, discussions about the coartados's status continued to exist.Footnote 69 During the early decades of the United States, conditional manumissions and self-purchases had produced a large population of “term slaves”; people who had acquired the right to become fully free after a certain period of time. This situation was common, for example, in the city of Baltimore. Maryland state laws regulated “term slaves” and even protected them from being sold out of state. Nonetheless, local judges could grant masters the power to rescind the manumission of “term slaves” who misbehaved.Footnote 70

Social historians have provided different analyses of conditional manumission in Brazil. In his study of a nineteenth-century São Paulo plantation, Warren Dean found that only a few manumissions were unconditional, immediate, and free of charge, thus concluding that despite “frequently assumed to be evidence of a liberal tendency in Brazilian slavery,” they were in fact “a very clear expression of paternalistic control.”Footnote 71 Katia Mattoso has focused on how conditionally manumitted slaves acquired certain benefits, such as the exemption from corporal punishments and the ability to own property, therefore constituting an “aristocracy” within slave communities. She argued that because of their bonds of familiarity with masters, their fear of how society would treat them as freedmen and women, and because they “knew that immediate freedom was not in the cards,” this “slave elite” tended to “accept their hybrid status, half-slave and half-free.”Footnote 72 Finally, Sidney Chalhoub has shown that conditional manumission blurred the distinction between slavery and freedom, rendering insecure the condition of free and freedpeople of African descent, and thus contributing to the “structural precariousness of freedom” in nineteenth-century Brazil.Footnote 73

Alongside conditionally manumitted slaves and slaves in condominium, other categories of persons pervaded Brazilian slave society. Between 1830 and 1856, the Mixed Commission Court formed by the British in Rio de Janeiro, as well as decisions by Brazilian authorities, liberated more than 8,000 African victims of the illegal trans-Atlantic slave trade. As the conditionally manumitted people, these “liberated Africans” were not legally slaves. However, they also faced restrictions in the recognition of and ability to exercise rights. For example, they were bound to 14 years of services for the state or individuals who acquired them.Footnote 74 After 1871, children born to slave mothers (ingênuos) and, after 1885, sexagenarian slaves, joined this large group of people living in between slavery and freedom.Footnote 75

Despite this social complexity, Brazilian and Portuguese jurists argued in their treatises that, according to the theory of status, legal persons were either free or slaves. They mentioned all other “categories of persons” only in a marginal way, when they mentioned them at all. This self-imposed “blindness” in legal academia contributed to the invisibility of people such as Benta and Benedicta. The jurists’ intellectual work was constitutive of valid law in Brazil. Therefore, when they chose to reduce society into the free–slave binary, they left everyone in between in a legal gap, which could be easily used as an excuse for illegal enslavement, thus contributing to what Chalhoub has called the “structural precariousness of freedom.”

Nonetheless, people in these intermediate situations lived in a juridical framework constructed by the daily practice of slavery law in courts and ministerial decisions. The initiatives of slaves like Benta provided visibility to ambiguous statuses. Silva held her and her daughter as slaves despite their dubious legal condition, thus making them victims of the “structural precariousness of freedom.” But Benta did not accept her hybrid status. Far from seeing herself as a privileged slave, she took the dangerous path of bringing their alleged master to court in order to break free from the three-quarters-slave, one-quarter-free status that had left her, and her daughter, subjected to his will. Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, while courts assessed cases such as Benta's, state ministers decided on various situations concerning conditionally manumitted persons. In their decisions, they considered that those persons were not slaves, because they had acquired freedom and only needed to fulfill the stipulated conditions.Footnote 76

Law in action prompted occasional acknowledgments of ambiguous statuses on the books. Trigo de Loureiro, for example, argued that there were two categories of freedpeople: the perfect and the imperfect. Imperfect freedpeople were those who did not yet have the “full enjoyment of natural liberty” because they had to work for their former masters for a period stipulated in the act of manumission.Footnote 77 Malheiro argued that, whereas in ancient Rome, the statu-liber (conditionally manumitted) was considered to be and treated as a slave, in Brazil he or she immediately acquired freedom. Nonetheless, the condition suspended or postponed the full exercise and entire enjoyment of that freedom. Malheiro interpreted this “evolution” as a consequence of “modern customs,” the nineteenth-century “spirit,” and the 1769 Law of Good Reason. Hence, the conditionally manumitted slave was neither slave nor free, but a kind of “intermediate” person. Malheiro often discussed their legal status as if they were freedpeople, enjoying the same rights, despite being subjected to the fulfillment of a condition. According to him, the compulsory services that these persons were bound to execute were compatible with their freedom: a conclusion aligned with the state ministers’ decisions. Furthermore, other legal persons, such as servants and orphans, were likewise subjected to compulsory work.Footnote 78 Advancing a more conservative and restrictive interpretation of Roman law, Freitas argued that conditionally manumitted persons were in a legal state “in between slavery and freedom.” According to him, the statu-liberi were “destined to be free after a certain period of time, or after the fulfillment of a condition.” They had the right to freedom. However, they would be effectively free only after the implementation of the condition.Footnote 79

Finally, conditional manumission made the difference between ownership and possession central to the meaning of freedom. According to property law, one's ownership rights over a slave could coexist with another's possession of that slave. For example, when a master rented his or her slave to someone, the master kept ownership while the renter acquired possession. In cases of conditional manumission, the question was whether possession remained with the owner until the condition was met or whether it was immediately transferred to the slave. Being in possession of oneself meant being free. Doctrine and legislation often referred to freedmen and women as being “in possession of freedom.”Footnote 80

Judicial discussions concerning possession of freedom were common in status determination lawsuits since at least the second half of the eighteenth century. According to legal doctrine, every “thing” could be possessed. “Things” could be material or immaterial. Rights were “immaterial things” and could, therefore, be acquired by exercising possession. Thus, a person could possess a right of freedom. To be in possession of freedom itself meant performing acts of freedom. In other words, if someone lived as a free person, if someone exercised the acts of a free person, he or she was in possession of his or her freedom and could consequently acquire ownership over him or herself.Footnote 81

Because the legal recognition of freedom could depend on the actual exercise of the acts of a free person, conditionally manumitted slaves were potential victims of re-enslavement. During their conditional period, they tended to exercise tasks associated with and be treated as slaves. According to Cruz, in Atibaia, Silva treated Benta and her daughter as slaves. Benta did not earn wages, was frequently punished, and did not exercise her own will. Benedicta had been baptized as a slave herself.Footnote 82 Therefore, the local community probably identified them as slaves. Because of the role that possession and social recognition played in determining legal status, judges could rule that a conditionally manumitted person was a slave, rather than a statu liberi. This happened, for example, to Felisminda from Rio de Janeiro in 1836. Despite producing a deed that proved her conditional manumission, Felisminda lost the lawsuit she had brought against her alleged master after witnesses, including a plantation overseer, testified to the social recognition of her life as a slave.Footnote 83

The Meaning of Freedom II: Born to a Free Womb

Benedicta was born at Villa de Santo Antonio da Cachoeira in July 1864, while Silva held her mother in slavery. A few weeks later, Silva took the newborn to the local church, where Benedicta was baptized as his slave. In a common strategic move, Silva used this religious ceremony to produce a documentary basis for his claim to property over the child.Footnote 84 Nevertheless, Benedicta's status was linked to her mother's status and, 2 years later, when they became plaintiffs in a freedom suit against Silva, her baptism certificate seemed irrelevant. If Benta was free when Benedicta was born, her daughter was also free. Both Medeiros and Cruz were aware of the old Roman dictum partus sequitur ventrem (the birth follows the womb).

The status of children born to conditionally manumitted slaves, or statu-liberi, was the object of controversial debates in Brazil and other parts of the continent. In eighteenth-century Cuba, a governor's decree had supported the principle that the status of children followed the mother's status, hence extending coartación to the children of coartadas. However, in 1789, the Consejo de Indias—the highest administrative council of the Spanish empire—ratified a royal cédula establishing that coartación was a personal benefit not transmissible from mother to child. Cases brought to court by slaves claiming freedom based on their mothers’ coartada status did not prosper.Footnote 85 In the United States, an 1809 Maryland law had established that children born to “term slaves” would be slaves for life, unless specified otherwise in the manumission document. Often, masters added a clause to the document requiring that these children serve a term of slavery until their early 20s.Footnote 86 In Brazil, neither the Portuguese colonial administration nor the independent monarchy passed legislation regulating this issue. Therefore, lacking a clear response from the written sources of law, lawyers had to use their interpretative skills to find an answer.

In October 1857, this controversy had been at the center of an avid debate at the IAB. During the decade that preceded this meeting, the judiciary gave ambiguous answers to the problem. Even the Supreme Court of Justice (Supremo Tribunal de Justiça), the empire's highest court, had published contradictory decisions within less than 10 years. Sensitive to the heterogeneity in judicial interpretations, Judge Caetano Soares proposed that the IAB members discuss whether a child born to a slave manumitted under the condition of performing services for a certain period was free.Footnote 87 The IAB debate provides a useful example of how disputes over ambiguous situations of children, such as Benedicta, were legally framed during the second half of the nineteenth century.

On the one hand, defending a “modern and civilized” interpretation based on the 1769 Law of Good Reason, Soares and Malheiro argued that children born to conditionally free mothers were completely free.Footnote 88 Nine years after the debate at the IAB, Malheiro reinforced his position in his treatise on slavery law, A Escravidão no Brasil (Slavery in Brazil). According to him, as the condition did not in itself affect the mother's freedom, her children were also free.Footnote 89 On the other side, however, stood the IAB's president, Freitas, one of the most influential jurists of his time. Following a supposedly literal interpretation of Roman law, he argued that because the statu liber was still a slave, her children should be considered slaves.Footnote 90 Finally, lawyer Salles Rosa proposed a compromise solution. He argued that, when the condition was fulfilled, the child would follow the mother's status, also acquiring freedom.Footnote 91

The IAB decided, almost unanimously, that because the obligation to perform services was a condition that termporarily suspended the effects of manumission, rather than a burden to the acquisition of freedom, children in this situation were in fact free.Footnote 92 Allegedly, the debate was so contentious that Freitas decided to leave the IAB afterwards.Footnote 93 The IAB controversy eventually influenced legal doctrine and practice. In his 1865 compilation of civil laws (Consolidação das Leis Civis), commissioned by the imperial government, Freitas slightly changed his argument, subscribing to Rosa's position. He wrote that in cases in which a conditionally manumitted mother gave birth to a child before the fulfillment of the condition, the best applicable law would be article 196 of the Louisiana Civil Code of 1825. According to this article, the child would be free when the mother fulfilled the condition.Footnote 94 In the 1869 case of Isabel, Ana, and Hilária against the financial institution Gavião Ribeiro & Gavião, the municipal judge of Guaratinguetá, also in the province of São Paulo, cited the IAB debate to support his decision to free Hilária. She had been born between her mother's conditional manumission and the fulfilment of the condition.Footnote 95

In Atibaia, Cruz's petition followed the logical conclusion derived from his understanding of Benta's status. If Benta was free, in spite of the obligation to compensate Silva for his three quarters of property, Benedicta should also be free. “No slave can be born to a free womb,” wrote the lawyer.Footnote 96 In turn, Medeiros argued that as Benta had not become free, her daughter was also a slave. He left unanswered the question of what would happen to Benedicta when her mother purchased the remaining three quarters to become free. Despite Rosa's compromise solution and Freitas’ revised position, it is reasonable to suppose that if Benedicta was born a slave, with an unchanged baptismal register to prove it, her status would remain the same even after Benta's acquisition of freedom, unless explicit proceedings for her manumission took place. Following Medeiros’ rationale, Benedicta would be Silva's property unless he personally agreed to manumit her.

Before Atibaia's municipal judge, the dispute over Benta's and Benedicta's statuses was initially framed with technical arguments grounded in institutions of civil law. In short, lawyers deployed the difference between ownership and possession, the idea of multiple ownership, and the concept of conditional manumission to draw different lines between slavery and freedom. Both Cruz and Medeiros defended their clients’ interests without reference to philosophical principles, political ideas, or natural law. Their sources were the Phillipine Ordinances, the Law of Good Reason, Roman law, and doctrinal studies that interpreted this heterogeneous body of legal sources. Their method was the deduction of case solutions from general legal rules, which was compatible with the nineteenth-century ideal of the development of an abstract legal science autonomous from society and politics.

Nonetheless, in Cruz's and Medeiros's final briefs to the municipal judge, and later at Rio de Janeiro's Court of Appeals, where different lawyers represented both parties, another layer of arguments entered the case. Technical discussions about the application of civil law rules were complemented by broader debates about values and institutions. This second argumentative layer translated the politics of slavery into philosophical ideas about law, property, and freedom, institutional arguments based on separation of powers, and the 1824 Constitution.

Courts, Politics, and Society

Article 179, section 22 of the 1824 Constitution guaranteed the right to property “in all its plenitude.”Footnote 97 The same article established that the inviolability of the rights of Brazilian citizens was based on their liberty and individual security. Because slaves were subjected to the powers attached to the right of ownership and were not Brazilian citizens—despite being legal persons—it was strategically challenging for lawyers to defend slaves’ rights by invoking the Constitution. The document was cited in only 4% of the freedom suits at Rio de Janeiro's Court of Appeals between 1850 and 1870.Footnote 98 Nonetheless, there were attempts to question the Constitution's absolute protection of property based on the clause that allowed expropriations for the “public good.” Judge Soares, for example, argued that the safest path to gradual abolition—which, for him, was a matter of “public utility”—was to expropriate slave owners, paying them a just price that was impartially arbitrated.Footnote 99 However, the clause's enforcement was conditioned on the existence of legislation regulating the specific cases in which expropriation was possible, and such a law did not exist with regard to slave property.Footnote 100

In his final arguments before the municipal judge, Cruz invoked the Constitution in a different way. The constitutional text was not useful in determining Benta's status and, even if she were a freedwoman (liberta), it did not grant her more than freedom from a master's sovereign will. Although freedmen (libertos) born in Brazil had the right to participate in local elections, women were generally excluded from constitutional protection. They were legally incapable of exercising certain civil rights, and categorically denied political participation.Footnote 101 Nonetheless, ignoring this general exclusion, Cruz argued that certain constitutional rights denied to slaves accompanied Benta's freedom.Footnote 102 It remains unclear what kinds of rights the lawyer had in mind. Article 179, I of the 1824 Constitution established that nobody could be obliged to do or not do something unless by virtue of legal command. With freedom, Benta and Benedicta would certainly leave Silva's dominium. Yet, despite what their lawyer suggested, they would remain substantially disenfranchised. Even as freedwomen, neither the Constitution nor social hierarchies would be on their side.

Although the 1824 Constitution did not support Benta's case, earlier colonial legislation did. Book 4, title 11, paragraph 4 of the Phillipine Ordinances indicated that “in favor of liberty, many things are declared against the general rules of law.”Footnote 103 Nineteenth-century jurists who wrote law review articles and legal treatises made widespread use of this passage to argue that, in ambiguous cases, the law favored freedom over slavery.Footnote 104 In his treatise, A Escravidão no Brasil, for example, Malheiro argued that this principle had its origins in Roman law, and stood as an interpretative rule in Brazil.Footnote 105 According to Cruz, the 1769 Law of Good Reason also supported Benta's freedom. The situation of part slave and part free person was unsustainable and, similarly to the Ordinances, “good reason” favored freedom over slavery. Like Malheiro, Cruz interpreted the vague concept of “good reason” in light of the late-nineteenth-century context of increasing abolitionist ideas. The lawyer argued that “any atom of freedom acquired by a slave irradiates itself all over him.”Footnote 106 In his interpretation of the law, freedom was not only indivisible, but also a powerful force that always trumped slavery when the situation was unclear.

The Constitution was, in fact, an obstacle to Benta's cause. Article 179's protection of property rights was almost absolute, and the exception of expropriation did not apply to slaves. One way to surpass this obstacle was to argue that human property was a special type of property, contrary to natural law but tolerated by positive law. This was the rationale attributed by many interpreters to the words of Lord Mansfield in the famous 1772 Somerset v. Stewart decision in England and to those of Justice Lemuel Shaw of the Supreme Court of Massachusetts in the 1836 case Commonwealth v. Aves.Footnote 107 In Brazil, Malheiro used this argument in 1863, and again in his treatise a few years later, citing Lord Mansfield.Footnote 108 Yet, in Atibaia, Cruz did not invoke natural law, nor did he contest the legality of human property. He did not have Mansfield's and Shaw's advantage of arguing on what could be constructed as free soil territory.Footnote 109 Working within a constitutional framework and a slave society that privileged property “in all its plenitude,” he sought a solution that assured Benta's freedom without violating Silva's property rights. Cruz reasoned that the collision between property and liberty was merely apparent in the case. If Benta were granted freedom with an obligation to compensate Silva for his property both rights would be guaranteed. This was possible because, whereas freedom was something indivisible, “compensated property [was] always property.”Footnote 110

The indivisibility of freedom did not necessarily favor Benta's claim. Silva's lawyer argued that if freedom was indivisible then it had to be unequivocally granted, as in the case of Chagas's other slave, Antonio. Unlike Antonio, who had been freed, Benta was granted the right to purchase her freedom by paying three quarters of her value. She remained a slave, albeit in a “modified position.” Perhaps because he recognized Cruz's strong rationale about the pecuniary character of property and the apparent collision of rights, Medeiros did not cite the constitutional right to property. Nonetheless, he applied the distinction between property ownership and exclusive use in his client's favor. This distinction was implicit in Medeiros's request that the judge put an end to the “abnormal and anarchical state”—the slaves’ placement in deposit—that had left his client unable to use his own property. The ability to directly or indirectly exploit a slave's labor was central to the idea of slave property. Precluded from “using” Benta and Benedicta, Silva had had his property rights allegedly violated.

The 1824 Constitution divided power into four branches. The legislative power was in charge of making, interpreting, suspending, and revoking laws; the executive power enacted decrees for the proper execution of those laws; and the judicial power was authorized to apply the law.Footnote 111 The moderating power, held by the monarch, who was also executive chief, was empowered to directly intervene in the other branches in order to maintain “harmony” among them.Footnote 112 In Benta's freedom suit, lawyers assessed the Parliament's, the monarch's, and the courts’ institutional roles in the conflictive politics of slavery.

In his brief, Cruz used vague expressions, such as “good reason” and “in favor of liberty,” which allowed substantial judicial discretion in their application to concrete cases. Although the Ordinances and the Law of Good Reason provided textual basis for his arguments, for Medeiros and Antonio Barbosa da Cunha—the lawyer who represented Silva at the appeals level—if the judges deferred to the interpretations proposed by Cruz they would betray their institutional role. Medeiros and Cunha did not explicitly invoke the constitutional separation of powers, but they argued that the judges were in charge of a “rigorous application of the law,” thus advancing a particular conception of the judiciary's role in the monarchical government.Footnote 113 In the eighteenth century, some European jurists criticized the ius commune regulations because they were insufficiently “clear,” “secure,” “rational,” and “unambiguous.”Footnote 114 In this context, the Portuguese colonial state adopted measures to restrict judicial discretion. The 1769 Law of Good Reason itself, despite introducing a vague concept, was part of a first attempt to unify national law and constrain judicial interpretation. Debates over this matter flourished during the nineteenth century. European and Brazilian law schools staged intellectual contests among the advocates of natural law, and of principles such as justice and equity, and those who thought that judges should apply positive law through a series of logical operations that left almost no room for discretion. The latter were proponents of codification, modeled after the 1804 French Civil Code.Footnote 115 In mid-nineteenth century Brazil, the controversy reached the highest levels of the recently created national government. Congress, the minister of justice, and the State Council discussed this issue.Footnote 116 Freitas’ 1850s project was supposed to produce a civil code: a national law intended to close legal gaps and interpretative openings.

Although the civil code was not yet completed in 1866, the space for interpretative discretion in Brazilian courts was narrowing.Footnote 117 Lawyers and judges worked within a more restrictive universe of legal sources and hermeneutic possibilities.Footnote 118 According to publicist José Antônio Pimenta Bueno, judges should decide “using as a norm nothing but the statute [lei], and just the statute, or the law [direito].” Whether drawing on “lei,” meaning statutes and decrees, or “direito,” meaning the legal order, the judges’ task should be technical, not political, and the judiciary's function was to maintain public order.Footnote 119 Yet slavery was an extremely controversial political topic, and its legitimacy was being contested in political forums. According to Silva's lawyer, Medeiros, the judiciary must not follow “the imprudent cry for emancipation” that was being considered in political branches.Footnote 120 In fact, in 1866, simultaneous with Benta's case, Bueno and others would submit projects of gradual emancipation for the State Council's evaluation.Footnote 121 For Medeiros, the judiciary's institutional role was to guarantee “public order” by ignoring these projects and respecting the fact that slavery, although perhaps otherwise illegitimate, was still legal in Brazil.

At Rio de Janeiro's Court of Appeals, where the case was finally decided, Silva's new lawyer Antonio da Cunha also emphasized the judiciary's role in protecting the legal order, and therefore slavery, despite its increasing illegitimacy. For him, judges should remain neutral regarding the ongoing “wave of humanitarian ideas” that attacked the institution of slavery. In a clever rhetorical move, Cunha claimed to be the “most sincere abolitionist” himself, but argued that while slavery was still a “legal fact” it ought to be respected by the courts.Footnote 122

Medeiros and Cunha used a formalistic approach to law, which restricted judicial discretion, in order to defend their client's property. In their view, by granting Benta and Benedicta freedom, the judicial power would be going beyond its institutional role of applying whatever written law prescribed. For sociolegal historians, formalism usually gains space when a dominant group attempts to “freeze” political goals already achieved.Footnote 123 In mid-nineteenth century Brazil, the case for formalism stood as a reaction to the increasing delegitimation of slavery as a legal institution.Footnote 124 Nonetheless, the arguments on the other side, sustaining Benta's claim, were also grounded in written sources of law, such as the Ordinances and the Law of Good Reason. These sources had established that “in favor of liberty, many things are ratified against the general rules of law,” and had made “good reason” an interpretative key of Brazilian law. This vague language required interpretation. Although old colonial sources such as the Ordinances and the Law of Good Reason were being gradually replaced by “modern” legislation, codes, and regulations, they were still considered valid law in Brazil.Footnote 125

In his last argument against Benta's freedom, Medeiros invoked the consequences of judicial decisions pertaining to slavery. He argued that the matter adjudicated was a “dangerous question,” thus engaging in a type of argument commonly used in cases that involved slavery across the Americas. In late-eighteenth-century Saint-Domingue, for example, slaves were portrayed as “domestic enemies” in courts and political theory, and by the colonial administration.Footnote 126 This portrait eventually gained life when the island's slaves rebelled against their masters in the 1790s, triggering a slave revolution that would create fear among slave owners in Brazil and other parts of the continent.Footnote 127 In his critique of slavery, jurist Malheiro wrote, in 1866, that slaves had been considered “domestic” and “public” enemies in all slave societies since Roman times.Footnote 128 According to Silva's lawyer, Medeiros, governmental interference made the “slave class” believe that the Brazilian monarch protected them. Precisely because the legislative and executive powers conveyed such a dangerous message, the judiciary's role was to preserve “public order” through “rigor and reflection in its decisions.”Footnote 129 Although manumissions and their judicial confirmation could be seen as instruments of social control, the judiciary's intervention in the masters’ private sovereignty over their slaves could also generate insidious consequences.

In Medeiros's brief, the “slave class” represented a dangerous enemy, which “always waited for the moment to revolt.”Footnote 130 Yet, by 1866, an effective slave revolt was unlikely to take place in the province of São Paulo. The Criminal Code severely punished insurrections, slaves were prohibited access to guns, and the government rewarded those willing to provide information about rebellious plans.Footnote 131 The most famous Brazilian slave revolt occurred in Bahia, far from São Paulo, in 1835, and barely lasted a day.Footnote 132 Nevertheless, with rumors about rebellion continuing to circulate, the terror remained alive among slave owners, thus opening space for Medeiros to argue, perhaps invoking a late version of the fear of a “new Saint-Domingue,”Footnote 133 that São Paulo presented a higher risk of insurrection than other provinces by virtue of its massive slave population.Footnote 134 That risk, wrote the lawyer, required the judge to be prudent in considering the kinds of hazardous consequences his decision could trigger. In this sense, although he called for a formalistic application of the law, Medeiros urged the judge to consider extralegal factors such as the risk of sociopolitical unrest in his decision-making.

A “More Holy and Natural Right”

Twenty months after Benta and her daughter made their way into the judicial system, on October 3, 1867, the municipal judge of Atibaia reached a decision. He first tried to make sense of the complex technical problem posed by Benta's status. On the one hand, Silva's lawyer claimed that if Francisca das Chagas had intended to free Benta, she would have explicitly done so, as she did with regard to the slave Antonio. Instead, Benta was left with a right to purchase her freedom (direito à liberdade), but not a right to be free (direito de liberdade). On the other hand, Cruz defended the idea that, as one of Francisca's heirs, Benta had become co-proprietor of herself. As the slave was indivisible property, one of the heirs should possess her and compensate the other for his or her share. In this case, because the Law of 1769 and the Phillipine Ordinances required a decision based on “good reason” and “in favor of liberty,” Benta should be the one in possession of herself. In nineteenth-century Brazil, being in possession of oneself could mean being free.

Faced with two plausible interpretations of Brazilian slavery law, judge Joaquim Augusto Ferreira Alves could have decided either way. In contrast to Cruz, he saw in the case a real collision between the right to liberty and the right to property. In his final decision, he stepped outside of the formalistic contest that had been staged by the two lawyers to claim that between liberty and property there was a “more holy and natural right.”Footnote 135 Perhaps incorporating an abolitionist spirit in his opinion, or perhaps for philosophical or even religious convictions, the magistrate decided that this right was liberty. Despite the monarchical government's efforts to codify civil law, and the increasingly narrow space of discretion in judicial decision making, the spectrum of natural law remained as a philosophical foundation, available each time that the system contradicted itself. Abolitionists made political use of it, referring to a natural right to freedom.Footnote 136 Some jurists, such as Malheiro, subscribed to the idea that liberty was a natural state of human beings that preceded the right to property. Invoking this idea, the judge ruled that Benta and Benedicta were free, with an obligation to compensate Silva. In order to guarantee the effectiveness of his ruling, he ordered an assessment of the values of Silva's property—three quarters of Benta—and of the services that Benta had performed for Silva during the years since the death of her former master. It was possible, according to him, that Benta had already compensated the defendant through her labor.Footnote 137

Benta's and Benedicta's struggle for freedom did not, however, come to an end in Atibaia. Silva appealed to Rio de Janeiro's Court of Appeals, where new lawyers represented both plaintiff and defendant. Cunha, Silva's representative, and João Francisco Diogo, who defended Benta and her daughter, were not among the most active lawyers at the Court of Appeals. Nonetheless, it is likely that they were part of a professionalized class of university-educated attorneys licensed to practice law at the appeals level. As for Diogo, it is uncertain whether he was part of the group of militant lawyers who were beginning to strategically use freedom suits for abolitionist purposes, and would intensively use litigation to undermine the institution of slavery during the 1880s.Footnote 138

At the higher court, the arguments did not differ much from those of Atibaia. Representing Silva, Cunha continued to emphasize a formalistic approach to legal interpretation, arguing that the judge's decision departed from a “rigorous application of the law.” Diogo, representing Benta and Benedicta, believed that the decision appealed was “in full harmony with the principles of science,” thus conforming to that nineteenth-century idea of a harmonious and logical legal science.Footnote 139 In both briefs, there was a sense that “humanitarian ideas,” or “sentiments of humanity,” were pushing Brazilian society away from slavery. However, whereas Cunha argued that the judicial task was precisely to contain these sentiments and ideas for the preservation of order, Diogo claimed that applying the law was a way of fulfilling humanitarian aspirations. More than 4 years had passed since Benta and her daughter first stepped into court. On April 12, 1870, without publishing their reasons, and therefore leaving them for us to imagine, the appeals judges confirmed the municipal ruling, finally liberating Benta and her daughter from what was now deemed to be an illegal condition of slavery created by the fiction of divided freedom.

Conclusion

Seventeen months after the court of appeals decided Benta's case, on September 28, 1871, the Brazilian Parliament enacted the Free Womb Law (Lei do Ventre Livre), which freed all children henceforth born to slave mothers. This statute was part of a gradual abolition process, which would include the emancipation of all slaves who were 60 years of age or older, in 1885, and the broad emancipation law of 1888. Discussions about the legislative projects that would become the Free Womb Law began in 1866, the year Benta went to court, but were paralyzed because of Brazil's involvement in the Paraguayan War (1864–70). When the law was eventually approved in 1871, it also addressed an extensive range of legal issues concerning slavery, including that of co-owned slaves. It guaranteed freedom when one of the co-owners manumitted the slave, making the law clearer and safer for slaves. Ironically, however, the same law that contributed to gradual abolition, gave with one hand and took away with the other. It also made it clear that it was the slave who should compensate the remaining co-owners for his or her freedom, which could be done with up to 7 years of services.Footnote 140 Therefore, slaves were bound to either find the resources to pay for their freedom or remain in a form of debt servitude. Because of provisions such as this, radical abolitionists portrayed the Free Womb Law as a conservative attempt to create clearer and more secure rules for slave owners, closing interpretative gaps that had allowed people like Benta to contest their statuses in court.Footnote 141

Cases such as Benta and Benedicta's likely had influence in the 1871 law's final text, which may have closed the gap that had opened space for judicial contest in Atibaia. In 1866, working to fill that gap, the lawyers had evoked civil law institutions, such as conditional manumission, possession, and co-ownership. Their arguments were textual interpretations of the Phillipine Ordinances and the Law of Good Reason, both enacted during the colonial period. This level of argumentation reveals the working of an autonomous legal rationale based on the fiction of property without possession, which grounded, for example, Cruz's simultaneous defense of Benta's and Benedicta's freedom and of the necessity of providing compensation that recognized Silva's property rights. Moreover, it reveals interpretative efforts to adapt liberal ideas about subjective rights to old colonial laws and theories based on status. In their initial petitions, lawyers used legal reasoning without reference to the politics or legitimacy of slavery. The law's autonomous operation was compatible with the Brazilian state's efforts to close legal gaps and inconsistencies through national civil law, and with the spirit of nineteenth-century legal thinking, which aspired to the development of a harmonious legal science based on a closed system of logical deductions.

As part of the official effort to systematize law in Brazil, between 1850 and 1881, the monarchical government commissioned three projects for the creation of a civil code. None of them addressed legal questions regarding slavery. In preparation for his civil code project, Freitas published his compilation of civil laws (Consolidação das Leis Civis) in 1857, which also excluded slavery. After a government commission in charge of reviewing his compilation pointed out that the laws and decrees that regulated slavery were missing, Freitas replied that slavery was a transitory institution and therefore should not be a part of the civil code. In the following editions of the compilation, however, Freitas added notes that addressed virtually all areas of the law of slavery. According to his notes, solving a case of slave property and solving a case of land property required the application of the same general rules and theories of civil law. Slavery was, therefore, not exceptional within the Brazilian legal system; it could have been part of a national civil code.Footnote 142 When Cruz framed Benta's situation as one of co-ownership and possession, he deployed the same vocabulary as that applied to land and other “things.” The “thing” owned, and after the court's decision, possessed by Benta, was her freedom.

Despite the rhetorical insistence of Brazilian jurists that the law of slavery was “confusing,” “obscure,” and “unclear,” norms that regulated slavery were not exceptional. Jurists made similar arguments for almost all areas of Brazilian law. These criticisms were part of a conscious strategy to advance codification as the ultimate stage in the systematization and harmonization of civil law, which would supposedly guarantee secure and stable private transactions and relationships. In Benta and Benedicta's case, the lawyers did what they would have done in any other civil law case. They interpreted an allegedly convoluted system of rules, combining colonial, national, and foreign legal theories and principles, to defend logical answers that favored each of their clients.

On a second level of argumentation, nonetheless, the politics of slavery permeated the Municipal Court and the Court of Appeals. First, the lawyers attacked political-constitutional questions, such as the collision of rights between property and liberty, and the separation of powers within the context of a growing abolitionist movement. Additionally, they engaged in sociolegal considerations, such as the role of the judiciary in a society in which the institution of slavery was increasingly losing its legitimacy, and the consequences of judicial decisions that interfered with masters’ sovereignty over their slaves. These problems were consistent with the issues raised by the consolidation of a liberal nation-state in a context of persistence of slavery. They also show that, during the midnineteenth century, despite Brazilian jurists’ efforts to advance an autonomous legal science, slavery necessarily raised political and social questions. These questions were not only about equality, labor, and humanity—themes that historians have extensively studied—but also about separation of powers, and the judiciary's interference with master–slave relationships.

Trial records are usually silent regarding the effectiveness of final judicial decisions. Therefore, Benta's and Benedicta's lives after 1870 are for the moment inaccessible to us. Nonetheless, we can imagine that mother and daughter lived as freedwomen (libertas), subjected to all the legal and social constraints that the “freed” status implied, as well as to all restrictions of rights imposed on women. Legally, freedpeople owed their former masters the respect of a “grateful son,” but Benta was probably not bound to this obligation because her last legal master, considering the court's decision, had been Francisca das Chagas, who was now long dead.Footnote 143 Nevertheless, she and her daughter still had to face the hardships of living in a hierarchical and patriarchal society, in which the possibility of re-enslavement was a constant menace. Poor black freedwomen, such as Benta and Benedicta, likely struggled with merely ensuring their material survival.Footnote 144 At least now, however, they were no longer under the rule of a master.