1. Introduction: Background, commencement of Arbitration, and site visit

On 7 July 2014, the Arbitral Tribunal rendered its much-awaited Award in the long-standing dispute concerning the determination of the land boundary terminus (LBT) and the establishment of a single maritime boundary delimiting the territorial sea, exclusive economic zone (EEZ), and continental shelf in the north-western Bay of Bengal.Footnote 1 The decision came after nearly five years of written arguments and counter-arguments, a site visit, and six days of oral hearings.

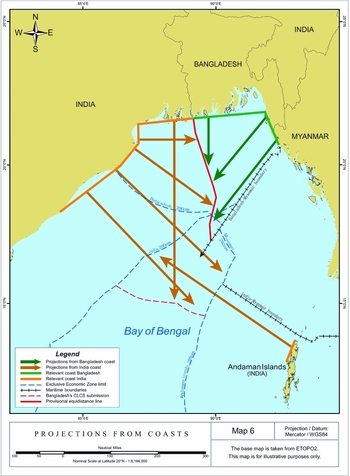

Bangladesh initiated arbitration proceedings under Annex VII of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in October 2009, requesting that the Arbitral Tribunal identify the land boundary terminus between the two states and delimit each state's territorial sea, EEZ, and continental shelf within and beyond 200 nautical miles (nm), where the claims of both states overlapped. The dispute arose as a result of strong prospects for gas in the area subject to overlapping claims in the Bay of Bengal, heightened by the demand for natural gas in the coastal states and the leasing by Bangladesh to US and Irish companies of three hydrocarbon–rich blocks in the Bay of Bengal which were contested by India and Myanmar. Bangladesh decided to settle the maritime disputes with Myanmar and India by procedures entailing a binding decision in accordance with Part XV of UNCLOS. To this end, on 8 October 2009 it initially instituted arbitral proceedings against both Myanmar and India under Article 287 and Annex VII of UNCLOS. In response, on 4 November 2009 Myanmar elected the jurisdiction of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) and Bangladesh confirmed that it too accepted the jurisdiction of the ITLOS on 13 December 2009, purportedly for cost reasons.Footnote 2 The ITLOS delivered its judgment on 14 March 2012.Footnote 3 It recognized the concavity of Bangladesh's coast as a relevant circumstance. ITLOS also delimited the continental shelf beyond 200 nm and dealt with the issue of the so-called grey area. Both Bangladesh and India referred extensively to the ITLOS judgment in presenting their arguments in the Bangladesh v. India case. As will be shown below, the PCA Tribunal also relied on the ITLOS's findings of fact and law (e.g. on base points), even though it underlined the independent character of its case. Note should be taken of the fact that the PCA Tribunal was composed of five arbitrators, three of whom took part in delivering the ITLOS judgment (Judges Wolfrum and Cot, and Judge ad hoc Mensah) and concurred in the Award. Another member of the Tribunal, Dr. P. S. Rao, while agreeing in large part with the majority, dissented on several points, including the selection of relevant coasts, the adjustment of the provisional equidistance line, and the issue of a ‘grey area’.

To discharge its responsibilities properly, the PCA Tribunal decided to conduct a site visit on 22–26 October 2013 to the relevant areas of the Bay of Bengal in order ‘to better establish the facts of the case’, in particular, ‘to observe the mouth of the Hariabanga river in situ’.Footnote 4 Therefore, the purpose of the site inspection was in reality to see the coastline, the Haribhanga (also alternatively Hariabangha) River, and the Raimangal Estuary, as well as the relevant coast of India and the proposed base points. It is worth noting that the Tribunal's in situ visit was a very rare instance where an adjudicating body has actually seen the geographic reality of the area. In fact, it was the first site visit of any international tribunal hearing a maritime delimitation case. It produced for the Tribunal a better picture of the relevant area for determination of the LBT and the proposed base points, including the ‘disappearing island’ of New Moore/South Talpatty.

Against this background, the purpose of this contribution is to analyse the current state of the law of maritime delimitation in light of the Bangladesh v. India case. Moreover, this article explores the determination of the location of the LBT, which delineates internal waters from the territorial sea (section 2). This is followed by a separate section devoted to the delimitation of territorial sea, discussing the method of delimitation and the selection of base points on low-tide elevations. In section 4 this commentary describes the concepts of ‘relevant coast’ and ‘relevant area’. Sections 5 and 6 provide a close analysis of the maritime delimitation with respect to the EEZ and continental shelf within and beyond 200 nm, including the concavity of a coast as relevant circumstance. Sections 7 and 8 discuss the adjustment of the provisional equidistance line and the disproportionality test. A consequence of the delimitation was the creation of a ‘grey area’, i.e., an area with overlapping entitlements claimed by Bangladesh, India, and Myanmar. Section 9 is devoted to an examination of this issue. Finally, a set of concluding observations is presented in Section 10.

2. The land boundary terminus

The India v. Bangladesh case was one of few cases including the selection of the LBT delineating land territory and internal waters from the territorial sea. Thus, the determination of the LBT also plays a role in maritime delimitation. The LBT dispute originated from the dissolution and partition of the British Indian Empire into what are presently the states of Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. In accordance with the Indian Independence Act of 1947 adopted by the United Kingdom Parliament, provisional boundaries were established between East Bengal and West Bengal, which formed respectively a part of India and Pakistan. Section 3(3) of the Act specified which districts of Bengal constituted its Eastern and Western parts, subject to the award of a boundary commission appointed by the then Governor General of India. The Bengal Boundary Commission was established on 30 June 1947 with Sir Cyril Radcliffe as Chairman. It completed its Report, commonly known as the ‘Radcliffe Award’, on 13 August 1947.Footnote 5 On 26 March 1971 Bangladesh declared its independence from Pakistan and it succeeded to the former boundaries of East Bengal, including the LBT with India.Footnote 6

Both parties agreed that the location of the LBT had been authoritatively defined in the Award and that the river boundary meets the Bay of Bengal at the intra fauces closing line across the mouth of the Raimangal Estuary.Footnote 7 Paragraph 10 of the Award states that ‘[t]he demarcation of the boundary line is described in detail in the schedule which forms Annexure A to this award, and in the map attached thereto, Annexure B’. (Figure 1). Paragraph 2 of the Annexure A provides that ‘[a] line shall then be drawn . . . to the point where the boundary between the Districts of 24 Parganas [in the west] and Khulna [in the east] meets the Bay of Bengal’. The Annexure A further specified in paragraph 8 that the final segment of the boundary ‘shall then run southwards along the boundary between the Districts of Khulna and 24 Parganas, to the point where that boundary meets the Bay of Bengal’. The district boundary, to which the Award referred, had been delimited by Notification No. 964 Jur. of the Governor of Bengal dated 24 January 1925, which provides that this part of the boundary was:

Figure 1 Radcliffe Map, Award, at 53.

the midstream of the main channel of the river Ichhamati, then the midstream of the main channel for the time being of the rivers Ichhamati and Kalindi, Raimangal and Haribhanga till it meets the Bay.Footnote 8

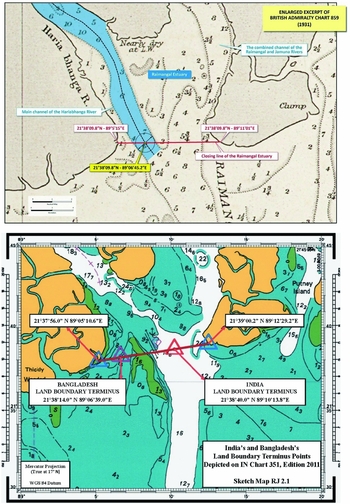

The main point of disagreement between the Parties was the location of the midstream of the main channel (Figure 2). They also differed as to the critical date for the determination of the location of the LBT and the drawing of the boundary. This included the selection of charts to be used to identify the location of the LBT as established by the Award prepared by Sir Cyril Radcliffe. The Tribunal decided that the 1925 Notification had been intended to refer only to the midstream of the main channel of the Haribhanga River as it enters the Bay. All four rivers flow from the north and the rivers Ichhamati and Lakindi flow at separate points into the Raimangal, which in turn flows partly into the Haribhanga. Both rivers then proceed southwards until they reach the Bay at separate points.Footnote 9 Thus, the geographic considerations determined that the Radcliffe Commission had referred to the midstream of the main channel of the Haribhanga River only. Having analysed the Award of the Indo-Pakistan Boundary Dispute Tribunal (the ‘Bagge Tribunal’)Footnote 10 and other documentary evidence, the Tribunal concluded that the critical date for the location of the mainstream of the main channel of the Haribhanga River was in 1947 at the time of the Radcliffe Award. In particular, the Bagge Award established clearly that the determination of the LBT must be made as it was in 1947, and not as it might become at later times.

Figure 2 LBT proposed by Bangladesh, Bangladesh's Hearing Folder, Tab. 4.7. LBT proposed by India, India's Rejoinder, Figure RJ 2.1, at 15.

The identification of the location of the LBT was also influenced by a site visit which the Tribunal conducted, to see in person the geographical circumstances of the Haribhanga River and the Raimangal Estuary. This afforded the Tribunal an opportunity to review the documentary and cartographic evidence and make the proper determination on the LBT. In particular, the Tribunal could assess the navigability of the western channel of the Haribhanga River leading to the LBT as proposed by Bangladesh, or its eastern channel proposed by India, to decide which of the proposed channels was the ‘main channel’ of the Haribangha River. To this end, on 24 October 2013 the Tribunal and the party delegations first embarked on the Bangladeshi vessel and departed for the western channel to the LBT proposed by Bangladesh. India argued that this demonstration proved this channel to be non-navigable and blocked by the ‘disappearing island’ of South Talpatty/New Moore.Footnote 11 Next, the Tribunal embarked on an Indian hovercraft and conducted a site inspection of the Haribhanga River, its eastern channel, and the mouth of the Raimangal Estuary.Footnote 12 According to India, the hovercraft proceeded to navigate to the centre of the Haribhanga, north of New Moore/South Talpatty, whereupon the motors were cut so that the craft could drift. At the same time, Indian naval vessels were anchored at India and Bangladesh's respective proposed LBT points to provide visual references for the Tribunal on board the hovercraft. A third Indian vessel was anchored further south in the main channel to provide a visual locator as well as a demonstration of the channel's navigability.Footnote 13 The site inspection seemed to show that the eastern channel is navigable as opposed to the western channel. It may therefore be assumed that it is probably for this reason that the Tribunal selected the eastern channel close to South Talpatty/New Moore which, at the same time, reflects a south-easterly direction of the land boundary depicted on the Radcliffe Map.Footnote 14

Figure 3 LBT, Award, Map 2, at 55.

Referring to the documentary and cartographic evidence, the PCA Tribunal explained that it had to refer to the ‘photograph of the territory’ then existing, as required by the jurisprudence of the International Court of Justice (ICJ).Footnote 15 The Tribunal, however, did not exclude a priori the possibility of using maps, research, or other documents subsequent to the critical date that may be relevant to establish the situation that existed at the time. Therefore, the Tribunal decided to locate the LBT:

as it was decided in 1947 on the basis of the available information at the time and supplemented by more recent information as to the situation at the critical date. The Tribunal considers that determination of this point, including the drawing of a closing line across the entrance to the Bay, requires reference to charts drawn at different times.Footnote 16

The recourse to charts drawn in different times was strengthened by the change of the major geographical features of the estuary over the last century. Thus, it might be said that the creation of the ‘photograph’ of the unstable river from almost 70 years ago, when existing technology did not allow for the precise drawing of maps, is more reliable when one refers to all available evidence, including charts prior to and subsequent to the critical date.

The Tribunal had at its disposal the 1931 Chart, the Radcliffe Map, and the 2011 edition of the 351 Chart. It decided to rely on the Radcliffe Map, as other maps were not deemed reliable since the 2011 Chart was prepared much later than 1947 and there was no evidence that Sir Cyril Radcliffe relied upon the 1931 Chart which, besides, was based on surveys conducted before 1879. Therefore, the Radcliffe Map was the only map suitable for establishing the LBT as it reflected most closely the situation at the critical date. Neither the small scale of the map nor the lack of precision common to most nautical charts rendered the Radcliffe Map susceptible to question. Accordingly, the Tribunal assumed that the end of the black dash-dot-dash line indicated the midstream of the main channel. It thus confirmed that in case of a dispute and ambiguous wording of an instrument (the award), the most reliable maps are those incorporated to those instruments, even though included for illustrative purposes.Footnote 17 Such maps reflect the geographical reality prevailing at the time and were taken under consideration when drafting the delimitation instrument. They were drawn by persons involved in the process of delimitation and are supposed to accurately reflect the wording of relevant clauses. As the Tribunal itself stated, ‘it should not attempt to establish the land boundary terminus on the basis of the wording of the Radcliffe Award without giving due regard to the attached map’.Footnote 18

While the selected location of the LBT does not raise any objections, the decision might have a certain degree of inconsistency, since the Tribunal in principle admitted reference to ‘charts drawn at different times’ but it eventually rejected both the 1931 and 2011 Charts as not reliable for the location of the LBT in the Radcliffe Award. If the determination of the LBT ‘requires’ reference to charts drawn at different times, the Tribunal should have given some value to the charts presented by the parties, or, perhaps, should have asked the parties to look again for more map evidence to submit to the Tribunal. In any case, it may be fairly argued that the general principle remains solid, namely that the LBT needs to be located on the basis of the available information at the time and supplemented by more recent information as to the situation at the critical date.

3. Territorial sea

3.1. The delimitation method and the selection of base points

The delimitation of territorial sea is governed by Article 15 of UNCLOS, which is virtually identical to Article 12 of the 1958 (Geneva) Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone and which reflects customary international law.Footnote 19 It provides that, in the absence of an agreement between the parties, historic title, or other special circumstances, the delimitation line should be drawn according to the equidistance line. It therefore seems that the equidistance line is the regular method for the purposes of delimiting the territorial sea of adjacent states.Footnote 20 Nonetheless, Bangladesh first argued for the angle-bisector methodology. Only subsequent to the decision of the ITLOS did it modify, to a certain extent, its position, adding its own construction of a provisional equidistance line in case the Tribunal would not decide in favour of Bangladesh's principal angle-bisector method.Footnote 21

Maritime delimitation depends upon the identification of a feasible base point. A coastal state has exclusive competence to delimit its maritime areas, but the validity of such delimitation with regard to other states depends upon international law.Footnote 22 The selection of the base points is the first step in drawing equidistance or median lines. Although the states are entitled to propose their own base points, a court or tribunal is not obliged to accept them and may establish its own base points for the purpose of the delimitation.Footnote 23 In this regard, it needs to be noted that there is still a large degree of discretion given to courts and tribunals. It seems, however, that they should at least take into consideration those base points which have been accepted by both parties.Footnote 24 The relevant base points are the most appropriate points on the coasts.Footnote 25 The case law gives preference to physical circumstances over human actions which artificially change the geography of a coast. The selected points should also mark a significant change in the directions of the coast in such a way that the geometrical figure formed by the line connecting all these points reflects the general direction of the coastlines. The point thus selected will reflect the physical geography of the coast and will have an effect on a provisional equidistance line.Footnote 26 To conclude, international case law has established relevant criteria by reference to which the base points are selected with respect to the territorial sea as well as the EZZ and the continental shelf. They are as follows:

- the physical geography of the relevant coasts;Footnote 27

- the most seaward points of the relevant coasts;Footnote 28

- the low-water line of the relevant coasts.Footnote 29

With respect to the territorial sea it should, however, be noted that the Arbitral Tribunal did not find the whole general configuration of the Bay of Bengal as the relevant coasts to the delimitation of the narrow belt of the territorial sea.Footnote 30 It therefore seems that only the immediate coasts should be relevant in selecting the base points for the delimitation of the territorial sea.

3.2. Low-tide elevations as base points

Bangladesh and India considered at length the selection of base points on low-tide elevations as India proposed a base point located on a low-tide elevation referred to as South Talpatty (by Bangladesh) or New Moore Island (by India) (Figure 4).Footnote 31 The Tribunal, relying on Black Sea, underlined that the equidistance and median lines should be constructed from the most appropriate points, with particular attention being paid to protuberant coasts situated nearest to the area to be delimited, which mark a significant change in the direction of the coast, in such a way that the geometrical figure formed by the line connecting the points reflects the general directions of the coastlines. It seems that such ‘most appropriate points’ are situated virtually on the mainland or islands. The use of low-tide elevations in constructing equidistance or median lines could have the potential effect of distorting the line in such a way that it would not reflect the coastline and the physical geography of the nearest area. Therefore, the Arbitral Tribunal concluded that:

Figure 4 India base points, Counter Memorial of India, Sketch-Map No. 5.3, at 107.

[i]f alternative base points situated on the coastline of the parties are available, they should be preferred to base points located on low-tide elevations.Footnote 32

The Tribunal consequently decided that ‘whatever feature existed could in no way be considered as situated on the coastline’ and that ‘South Talpatty/New Moore Island is not a suitable geographical feature for the location of a base point’.Footnote 33

4. Relevant coasts and relevant area for delimitation beyond territorial sea

Any maritime delimitation of EEZ and continental shelf first requires the determination of both the relevant coasts and the relevant maritime area.Footnote 34 It seems that there are three general principles on the concept of relevant coasts:

1. a coast is relevant for the purpose of delimitation if it generates projections which overlap with projections from a coast of the other state;

2. the land dominates the sea through the projection of the coasts or the coastal fronts. Territorial sovereignty over the land constitutes the legal title to the territorial extensions seawards;

3. the apportionment of maritime areas is to be proportional. Proportionality is measured by the ratios of the coastal length of each state and the maritime areas falling on either side of the delimitation line between adjacent or opposite states.

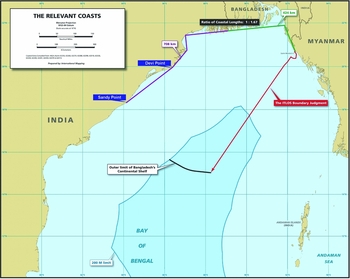

The Arbitral Tribunal concluded that the length of Bangladesh's relevant coast is 418.6 km.Footnote 35 With respect to India, the parties differed significantly as to whether the segment of Indian coastline between Devi Point and Sandy Point, which measured 304 km, was relevant. (Figure 5). In this regard, the Bangladesh v. India Tribunal stated that:

the coast is relevant, irrespective of whether that overlap occurs within 200 nm of both coasts, or within 200 nm of one and beyond 2000 nm of the other. . . . To establish the projection generated by the coast of a State, the Tribunal considers that “what matters is whether [the coastal frontages] abut as a whole upon the disputed area by a radial or directional presence relevant to the delimitation”.Footnote 36

Since the coast between Devi Point and Sandy Point faced directly on the projection of the continental shelf beyond 200 nm claimed by Bangladesh, the Arbitral Tribunal held that this coast was relevant for the purposes of maritime delimitation.Footnote 37 Choosing Devi Point over Sandy Point would have resulted, as argued by India, in non-selecting the segment of the Indian coast which directly faces the projection of the continental shelf beyond 200 nm claimed by Bangladesh and, consequently, it would have significantly reduced the relevant area (Figure 6).Footnote 38 This would run counter to the general rule that a coast is relevant for the purpose of delimitation if it generates projections which overlap with projections from a coast of another state. In this regard, Dr. Rao disagreed with the majority with respect to the selection of Sandy Point (and the Andaman Islands), since ‘the coastal front is neither adjacent nor opposite to the coast of Bangladesh’.Footnote 39 However, bearing in mind the general rule and the fact that the section from Devi Point to Sandy Point produced the projection which directly overlapped that of the coast of Bangladesh, the dissent of Dr. Rao seems to be unfounded. Otherwise, it could have been argued that the PCA Tribunal contested the Black Sea dictum that ‘the coast, in order to be considered as relevant, must generate projections which overlap with projections from the coast of the other Party’.Footnote 40

Figure 5 The relevant coasts proposed by Bangladesh, Reply of Bangladesh, Figure R5.10, at 155. [Devi Point and Sandy Point added].

Figure 6 The relevant coasts and area proposed by India, Counter Memorial of India, Sketch-Map No. 6.7, at 143. [Devi Point added].

The Arbitral Tribunal also hypothetically considered the extension of relevant Indian coast beyond Sandy Point. In this regard, the Tribunal deemed it appropriate to state that a radial line drawn north-east along the Indian coast south of Sandy Point could also generate a projection that would overlap with the projection of the coast of Bangladesh beyond 200 nm. However, each court or tribunal enjoys:

a margin of appreciation in determining the projections generated by a segment of coastline and a point at which a line drawn at an acute angle to the general direction of the coast can no longer be fairly said to represent the seaward projection of that coast.Footnote 41

Although it was not necessary, the Tribunal established that in such cases it had a margin of appreciation in selecting segments of coastlines which form relevant coasts. At the same time, it did not elaborate further on this point and, especially, it did not indicate which factors or criteria would be pertinent for the determination of relevant coasts in such cases. Thus, the statement of the Tribunal introduced an element of subjectivity, which the Tribunal, throughout the Award, had tried to avoid. Although each court and tribunal should have certain discretion in the process of maritime delimitation, it should at same time be guided by transparent and objective criteria properly developed and described, which can be verified and which should not be limited to the obscure concept of ‘unfair angle’. In this regard, it may be regretted that the Tribunal introduced the ‘margin of appreciation’ principle while barely describing the guiding criteria in choosing the relevant coast in such cases, thus introducing a degree of uncertainly, subjectivity, and lack of precision to its decision.

In trying to elaborate more on the concept of an ‘unfair angle’, it should firstly be noted that such an angle did not arise between Devi Point and Sandy Point, as the overlapping projection extended in a line nearly perpendicular from the coast. At the same time, a segment of the coast beyond Sandy Point did not generate such an overlapping projection that could be fairly said to represent the seaward projection of the coast. Having that in mind, the rule would appear to be that the projections generated by a segment of coastline must fairly represent the seaward projection of the coast. The angle must be fair. Such is the case with respect to projections extending in a (nearly) perpendicular line from the coast. In accordance with the Award, an overlapping projection which extends at a certain imprecise acute angle from the coast may not fairly be said to represent the seaward projection of the coast. It therefore seems that a borderline delimiting fair and unfair maritime projections lies somewhere between a perpendicular line and a line drawn at an acute angle to the general direction of a segment of the coast. The borderline may change to some extent from case to case, depending upon geographical circumstances. Still, the Award's lack of further criteria in developing the concept of ‘unfair angle’ contains elements of imprecision and subjectivity.

The Tribunal also noted that the coast of India's Andaman Islands generated overlapping projections, even though they also overlapped with the projection of the mainland coast of India. Accordingly, the relevant coast of mainland India measured 706.4 km and the relevant coast of the Andaman Islands measured 97.3 km, producing a total of 803.7 km of relevant coast of India (Figure 7).Footnote 42 It allowed for the determination of a relevant maritime area which was calculated to be approximately 406,833 square km.Footnote 43

Figure 7 Total relevant area, Award, Map 4, at 89. [Devi Point added].

5. The delimitation of EEZ and continental shelf within 200 NM

5.1. Delimitation methodology

As in the case of the territorial sea, Bangladesh favoured the angle-bisector method while India requested the use of the equidistance/relevant circumstances method (Figure 8).Footnote 44 The question concerning the delimitation methodology was discussed by the ITLOS in Bangladesh/Myanmar, where Bangladesh also argued for application of the angle-bisector method. Both the ITLOS and the PCA Tribunals observed that Articles 74 and 83 of UNCLOS do not specify any particular method to be applied.Footnote 45 Whatever method of delimitation is chosen must produce an equitable result. This means that, in the first place, a court or tribunal needs to take under consideration the prevailing geographic realities and the particular circumstances of a given case.

Figure 8 The Bengal Delta, the angle-bisector method and the equidistance line proposed by Bangladesh, Reply of Bangladesh, Vol. II, Figure R4.28.

Second, in addressing the method of delimitation a court or tribunal should be guided by the international case law on maritime delimitation so as to assure the transparency and predictability of the delimitation process and reduce subjectivity and uncertainty.Footnote 46 The Arbitral Tribunal, for its part, added that:

transparency and the predictability of the delimitation process as a whole are additional objectives to be achieved in the process. The ensuing – and still developing – international case law constitutes, in the view of the Tribunal, an acquis judiciaire, a source of international law under Article 38(1)(d) of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, and should be read into Articles 74 and 83 of the Convention.Footnote 47

According to the Tribunal, the obligation of transparency and the predictability of the delimitation process stems from the law of maritime delimitation. It is impossible to think of assuring the objectivity, transparency, and predictability of the delimitation process without referring to the international case law on maritime delimitation, which in the majority of cases applied the equidistance/relevant circumstances method. Indirectly, both the ITLOS and the PCA Tribunal observed that the requirement to achieve an equitable result is based on the presumption that previous case law will be at least carefully considered and applied, if possible, in any maritime delimitation dispute. It is therefore the function of international courts and tribunals to enhance the objectivity, predictability, and transparency of the delimitation process. However, in this regard it should also be observed that the Tribunal endorsed, to a certain extent, the existence of a margin of appreciation in certain aspects of maritime delimitation (e.g. relevant coasts),Footnote 48 hence emphasising flexibility. Accordingly the Tribunal's attachment to objectivity, predictability, and transparency may therefore be questioned. Yet it is necessary to ensure a degree of flexibility in every legal system and the law of maritime delimitation also needs a carefully drawn balance between predictability and flexibility. In summary, it may be observed that the Tribunal's Award tries to reconcile these elements in various stages of maritime delimitation.

Having said this, it needs to be considered whether both methods fulfil the aim of inserting transparency and predictability into the delimitation process. It would seem that there are certain arguments in favour of the equidistance/relevant circumstances method. It has been described as having ‘a certain intrinsic value because of its scientific character and the relative ease with which it can be applied’.Footnote 49 Thus, the scientific character and the relative ease in practical application of the method may underscore the transparency and predictability of the delimitation process. Moreover, the equidistance/relevant circumstances method has been applied in the majority of recent delimitation cases,Footnote 50 while there are only a few cases in which the angle-bisector method has been employed.Footnote 51 ITLOS pointed out that jurisprudence had developed in favour of the equidistance/relevant circumstances method, signalling indirectly that it is the method to be primarily employed by courts and tribunals.Footnote 52 The Bangladesh v. India Tribunal did not even refer to Bangladesh's relevant argument and focused only on the possibility of the identification of equidistance base points.Footnote 53 It described the three stages of the equidistance/relevant circumstances method in order to underline its objectiveness, predictability, and transparency.Footnote 54 The Arbitrators did not explain why the equidistance/relevant circumstances method is more predictable, but it may be assumed that since it has been applied in the majority of maritime cases, it may therefore reasonably be expected that it will be applied in future cases unless extraordinary geographic realities or particular circumstances occur in a given case. According to the case law, the leading factor in not applying the equidistance/relevant circumstances method is the impossibility of identification of base points. Having that in mind, the general rule with respect to the delimitation method appears to be that the equidistance/relevant circumstances method does not automatically have priority over other methods of delimitation, but is preferable unless there are factors which make the application of the equidistance method inappropriate. Nevertheless, it seems that, while agreeing that the equidistance/relevant circumstances method is preferable and more predictable, the PCA Tribunal still acknowledged that courts and tribunals have a certain degree of discretion in selecting the delimitation method.

Figure 9 Comparison of the coastal front in Bangladesh v. India and Guinea v. Guinea Bissau prepared by Bangladesh, Reply of Bangladesh, Vol. II, Figure R4.22.

5.2. The first stage of the equidistance/relevant circumstances method: The establishment of the provisional equidistance line

The application of the equidistance/relevant circumstances method consists of three separate and defined stages.Footnote 55 The delimitation process starts with the determination of a provisional delimitation line, using methods that are geometrically objective and appropriate for the geography of the area concerned. An equidistance line is drawn between adjacent coasts and a median line between opposite coasts.Footnote 56 The initial step is to identify the most appropriate coastal points (base points) from which the equidistance lines are to be constructed. As discussed above,Footnote 57 the selection of base points for the purposes of delimitation of the EEZ and continental shelf are virtually the same as with the delimitation of the territorial sea. In this respect, the Arbitral Tribunal decided that the base points already selected for the purposes of the delimitation of the territorial sea and additional three base points on the coast of Bangladesh, as well as two base points on the coast of India, were appropriate for the construction of the provisional equidistance line.Footnote 58 Consequently, it drew the line with five controlling points until the 200 nm limits of Bangladesh and India were reached (Figure 10).Footnote 59

Figure 10 The provisional equidistance line, Award, Map 5, at 107.

5.3. The second stage: The concavity of a coast as a relevant circumstance

The second stage of the delimitation process consists of considering whether any factors exist which call for the adjustment or shifting of the provisional equidistance line in order to achieve an equitable result. The purpose of this stage is to ensure that geometry does not prevail over equity.Footnote 60 There are two groups of relevant circumstances: geographical and non-geographical categories.Footnote 61 In the current case Bangladesh argued that coastal instability of the Bengal Delta, concavity, and cut-off effects, as well as fisheries, constituted circumstances which called for an adjustment of the provisional equidistance line.

The Arbitral Tribunal dismissed the first and the last circumstances.Footnote 62 The second factor was much more important to the case as it concerned concavity and the cut-off effect. Bangladesh submitted that (i) its entire coast is concave; (ii) the coast has a concavity within a concavity; (iii) coastal concavity can be a relevant circumstance, where the state with a concave coast is pinched between two other states, or otherwise where the concavity causes a cut-off effect; (iv) ITLOS determined that Bangladesh's coastal concavity was a relevant circumstance justifying a departure from equidistance; and (v) this concavity, even after the ITLOS judgment, cuts off Bangladesh from its maritime entitlements.Footnote 63 It relied heavily on the similarities between the present case and the North Sea cases, where the simple application of the equidistance rule to the concave German coastline inserted between the coastlines of Denmark and the Netherlands would have restricted Germany to a small and modest triangle of continental shelf, to the substantial benefit of its neighbours (Figure 11). In such a case, both equidistance lines, operating together and not separately, would have produced a cut-off effect.Footnote 64 Bangladesh also referred extensively to the Bangladesh/Myanmar case, where the ITLOS found the concavity of the coast of Bangladesh to be a relevant circumstance.Footnote 65

Figure 11 Agreed maritime boundaries: Germany-Denmark / Germany-Netherlands, Memorial of Bangladesh, Vol. II, Figure 6.12.

The concavity of a coast has been frequently invoked as a relevant circumstance. It is a common feature of maritime coasts and the coast of Bangladesh is a classic example thereof. In Bangladesh/Myanmar, the ITLOS itself affirmed that the coast is manifestly concave and found the concavity of the coast of Bangladesh to be a relevant circumstance, even though it did not discuss the issue of concavity and a cut-off effect in detail.Footnote 66 In this respect, the Arbitral Tribunal deemed it appropriate to make certain observations. First of all, the Tribunal again underlined its particular attention to the necessity of maintaining objectivity and transparency in the process of maritime delimitation, and to the concept of a single continental shelf, which makes the distinction between the inner and outer continental shelf inappropriate.Footnote 67 To preserve these principles, it seemed to identify the relevant considerations which govern the determination of the existence of a cut-off effect, which may require the adjustment of the provisional line. They are:

1. the examination of the whole area in which competing claims have been made;Footnote 68

2. the configuration and extent of the parties’ entitlements to areas of the continental shelf beyond 200 nm;Footnote 69

3. the manifest concavity of the coast;Footnote 70 and

4. the cut-off effect on the seaward projections of relevant coasts produced by the provisional line.Footnote 71

Next, the Tribunal analysed how the seaward projections of the Bangladesh's coast were affected by the provisional equidistance line. It came to a conclusion that the line produced a cut-off effect due to the concavity of the coast, which may require the adjustment of the provisional line (Figure 12).Footnote 72

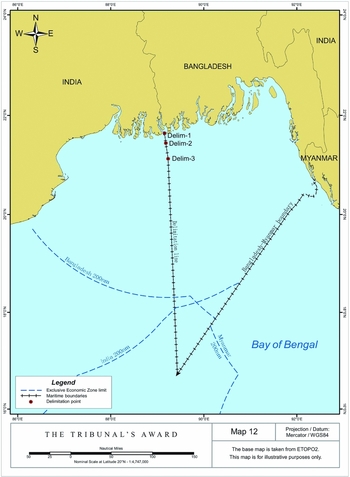

Figure 12 Projections from coasts, Award, Map 6, at 119.

The exact treatment to be given to a cut-off effect that warrants adjustment of the provisional line formed a line of disagreement between the majority and Dr. Rao. Both the Award and the Opinion underscored that the ultimate goal of the maritime delimitation is to achieve an equitable solution.Footnote 73 However, Dr. Rao, while agreeing on the cut-off effect as a relevant circumstance, objected to the drawing of the adjusted line, which the Arbitrator regarded to be flawed. Dr. Rao singled out three objections to the majority's considerations. First, the starting point of the adjustment (Delimitation Point 3) lay well before the significant cut-off effect occurred. Second, the Award did not reason its justification of the azimuth of the adjusted line in a satisfactory manner. Third, the line of 1770 30’ 00’’ azimuth chosen by the majority was similar to the azimuth of the bisector line 1800 proposed by Bangladesh.Footnote 74 Each of these points will be dealt with below, together with the respective parts of the Award.

The Tribunal considered several equitable criteria which might be relevant for the purpose of the adjustment of the provisional line due to the cut-off effect, similar to those determining the existence of such a cut-off effect. They can be summarized as follows:

1. the examination of the geographic area as a whole;Footnote 75

2. the maritime boundary with third states, to wit, Myanmar, and the judgment of the ITLOS ameliorating the cut-off effect;Footnote 76

3. the necessity to avoid the creation of a new cut-off as a result of the adjustment;Footnote 77

4. the need to avoid encroaching on the entitlements of third states and the entitlement of the other party to a dispute;Footnote 78

5. the need to avoid the cut-off produced by the provisional line preventing a coastal state from extending its maritime boundaries as far as international law permits, which also encompasses the entitlements to the outer continental shelf;Footnote 79

6. the inequitableness of the non-adjusted provisional line;Footnote 80 and

7. the size of the area already allocated to the parties on the basis of the provisional equidistance line.Footnote 81

The first criterion was only briefly mentioned by the Tribunal and thus seems to be of minor relevance. More fundamental was the question concerning the maritime boundary with Myanmar and the ruling of the ITLOS. In this regard, India argued that no adjustment was needed because the concavity had been ameliorated by the ITLOS ruling.Footnote 82 The PCA Tribunal rejected that argument and emphasized that:

the case before [ITLOS] and the present arbitration are independent of each other. They involve different Parties, separate proceedings, and different fora. Accordingly, the Tribunal must consider the Judgment of [ITLOS] as res inter alios acta.Footnote 83

The Tribunal found its authority in the case of Barbados v. Trinidad and Tobago, where the arbitrators refused to take into consideration a delimitation agreement between Trinidad and Tobago and Venezuela.Footnote 84 Thus, it decided that the criterion of maritime delimitation with Myanmar was not a relevant consideration with respect to the cut-off effect. It may be questioned, however, whether the Tribunal took due regard of the North Sea cases, in which the ICJ observed that:

[a]lthough the proceedings have thus been joined, the cases themselves remain separate, at least in the sense that they relate to different areas of the North Sea continental shelf, and that there is no a priori reason why the Court must reach identical conclusions in regard to them,– if for instance geographical features present in the one case were not present in the other. . . . it must be noted that although two separate delimitations are in question, they involve – indeed actually give rise to – a single situation. The fact that the question of either of these delimitations might have arisen and called for settlement separately in point of time, does not alter the character of the problem with which the Court is actually faced, having regard to the manner in which the Parties themselves have brought the matter before it, as described in the two preceding paragraphs.Footnote 85

An instance of ‘a single situation’ also obviously appeared in the Bay of Bengal, the geographic coastline of which is similar to the geographic situation of the south-eastern North Sea.Footnote 86 The Court also underlined that in the North Sea cases neither of the equidistance lines drawn between the Netherlands and Germany and between Denmark and Germany respectively, would produce the cut-off effect on its own, but they would do so together.Footnote 87 Thus, it might be argued that it is at least difficult to achieve an equitable solution to a ‘single situation’ at the expense of one state only.Footnote 88 The Arbitral Tribunal should have taken under consideration the ITLOS decision with respect to the concavity of the Bangladesh's coast and its cut-off effect, so as to delimit a single situation equitably. Even though both cases concerned two separate delimitations, the Arbitral Tribunal could have invoked the ITLOS decision to confirm that it would at least consider that decision in light of the North Sea decisions. This would certainly ensure increased transparency and predictability in the process of maritime delimitation, aims to which the Arbitral Tribunal seemed to be seriously attached. What is more, although there was no a priori reason why the Tribunal must have reached identical conclusions in regard to a single situation with respect to a cut-off effect, it would also have confirmed its previous general remark that international case law constitutes a source of international law under Article 38(1)(d) and should be read into Articles 73(1) and 84(1) of the Convention.Footnote 89 Thus, there seems to be a contradiction in the reasoning of the Tribunal, which refrained from referring to the relevant part of the North Sea cases and the conclusion reached by the ITLOS as regards a cut-off effect. Eventually it could be argued that the Tribunal made a tacit reference to the Bangladesh/Myanmar case by stating that it would

take into account any compensation Bangladesh claims it is entitled to due to any inequity it suffers in its relation to India as a result of its concave coast and its location in the middle of two other States, sitting on top of the concavity of the Bay of Bengal.Footnote 90

This conclusion might be supported by the further paragraphs of the Award, where the Tribunal quoted North Sea and Bangladesh/Myanmar to outline the drawbacks of equidistance lines between three adjacent states and to note that the ITLOS considered it necessary to adjust its equidistance line on account of the concavity of Bangladesh's coast.Footnote 91 It may have also been the case that the Tribunal wanted to put emphasis on the res inter alios acta principle and referred indirectly to North Sea and Bangladesh/Myanmar, since three arbitrators were sitting on the bench in the Bangladesh/Myanmar case. However, the PCA Tribunal had no hesitations in relying on other findings of fact and law by the ITLOS, for example, on exercising its jurisdiction to decide on the lateral delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nm before its outer limits have been established, on the distinction between the delimitation of the continental shelf and the delineation of its outer limits under Article 76, on base points, relevant area, and transparency and predictability of maritime delimitation, the concavity of the coast, the entitlement of Bangladesh to the continental shelf beyond 200 nm, and the grey area.Footnote 92 This inconsistency in the approach of the Tribunal to the ITLOS judgment seems remarkable. Hence, if the Tribunal relied on the ITLOS's findings with respect to so many aspects of the delimitation process, it should have also referred expressly to the ITLOS judgment with respect to the issue of ‘a single situation’ along the lines of the North Sea cases.

This point in the reasoning of the Tribunal was also contested by Dr. Rao, who referred extensively to the North Sea cases, albeit in a different aspect. According to the Arbitrator, the ICJ had decided in the North Sea cases that when an equidistance method produces ‘extraordinary, unnatural or unreasonable’ results, delimitation methods other than equidistance should be made or adjustments should be made to the provisional line.Footnote 93 The proper application of equitable principles contributes to transparency, certainty, and predictability. In this regard Dr. Rao highlighted one such principle especially relevant in the present case, which rejects the idea that equity could amount to a refashioning of geography or compensating for the inequalities of nature.Footnote 94 He also noted that a cut-off may occur as a result of other factors, including the existence of a maritime boundary with a third state. In this regard, he relied on the observation of the ICJ that ‘[t]he effect of concavity could of course equally be produced for a country with a straight coastline if the coasts of adjacent countries protruded immediately on either side of it’,Footnote 95 to conclude that the cut-off effect could not be entirely attributed to the concavity of the coast, since the maritime boundary with Myanmar is a relevant factor that should have been taken into account while drawing the adjustment line.Footnote 96 In other words, the boundary with Myanmar is a relevant circumstance acting in favour of India, which demanded weakening of the significance attributed to the cut-off effect produced by the concavity of Bangladesh's coast. A careful reading of the North Sea cases, however, does not warrant adopting such a conclusion. Rather, it is the concavity of the coast only, and not the boundary with a neighbouring state, that is a relevant circumstance. In this regard, the Court adopted the view that the concavity of Germany's coast was a relevant circumstance which required adjustment of the maritime boundaries with both Denmark and the Netherlands. The middle state, sitting on top of the concavity and being located between two other states, suffers from its geographical location, preventing it from extending its maritime territory and thus any adjustment of the boundary line on account that the cut-off effect with one state should have no relevance for the adjustment of the maritime boundary with the other state. The cut-off effect is not mitigated by the adjusted maritime boundary with one state, as it is produced by the concavity of the coast in relation to two neighbouring states which cut off the middle state from furthering the area of its continental shelf as far seaward as international law permits.Footnote 97 It is ‘a single situation’, although two separate delimitations are in question. Therefore, adjusting only one equidistance line would not completely improve the situation as only both equidistance lines taken together produce the cut-off effect. It once again demonstrates that the Tribunal could have relied on the ITLOS's findings in light of ‘a single situation’ as described in North Sea. It would have also reinforced the Tribunal's reasoning regarding the concavity of the coast of Bangladesh as a relevant circumstance.

Inasmuch as the Arbitral Tribunal was mindful of the need to avoid the creation of a new cut-off as a result of adjustment, as well as the need to avoid encroaching on the entitlements of third states and the entitlement of India, it held that a cut-off effect produced by a provisional equidistance line must fulfil two criteria to warrant an adjustment of the equidistance line. First, the line must prevent a coastal state from extending its maritime boundary as far seaward as international law permits. Second, the line must be such that it would fail to achieve an equitable solution. This demands ‘an assessment of where the disadvantage of the cut-off materializes and of its seriousness’. Both criteria were deemed met in the present case. The provisional line prevented Bangladesh from extending its maritime boundary as far seaward as international law permits and the area allocated to it formed a triangle typical for the cut-off effect. According to the Tribunal, the cut-off effect ‘is evidently more pronounced from point Prov-3’, where the provisional equidistance line ‘bends markedly eastward to the detriment of Bangladesh’. Consequently, the Tribunal held that the provisional line did not produce an equitable result and must be adjusted in order to avoid an unreasonable cut-off effect for both Bangladesh and India.Footnote 98

The decision on the adjustment again raised certain objections on the part of Dr. Rao. Firstly, the Tribunal did not take into consideration the size of the areas already allocated to Bangladesh and India on the basis of the provisional line. He opined that the Delimitation Point 3 was situated in an area in which the provisional line allocated a greater share of the Bay to Bangladesh than to India (Figure 13).Footnote 99 The point made by the dissenting Arbitrator is at least worth considering and the Tribunal should have discussed whether the size of the areas already allocated to the parties was a relevant criterion. It might be arguable that the size of the allocated areas is considered during the third phase of the delimitation process and therefore it is not relevant at the second stage, which is devoted to the consideration of relevant circumstances. However it is difficult to see why the size of the areas already allocated to the parties should not have influenced the decision on the extent of the cut-off effect that warranted an adjustment. The geographical reality of the area forms the basis of the delimitation process, which demands an equitable solution. Such a solution is not aimed at refashioning the geography. This principle should also be reflected in the adjustment of the provisional line, by taking into consideration the size of the areas already allocated to the Parties. Instead, the Tribunal decided to focus mainly on extending the maritime boundaries of Bangladesh as far as international law permitted, and by doing so, blocked itself from considering the criterion of the size of the areas already allocated to the Parties.

Figure 13 Sketch Map prepared by Dr. Rao, Concurring and Dissenting Opinion of Dr. P. S. Rao, at 11.

Second, Dr. Rao disagreed on the selection of point Prov-3 as the starting point for the adjustment of the delimitation line. In his opinion, in the present case the cut-off occurred at a point anywhere from 240–290 nm, depending on the point chosen along the coast of Bangladesh to measure the distance.Footnote 100 Only in the part of the provisional line closer to the coast and far from the 200 nm limit of Bangladesh was some deflection noticeable. This was supported by the fact that point Prov-3 was situated in an area in which the provisional line allocated a greater share of the Bay to Bangladesh.Footnote 101 In contrast, the equidistance line exhibited ‘a bit more pronounced’ deflection towards the eastern coast of Bangladesh at a point below point Prov-4 and above point Prov-5.Footnote 102 Dr. Rao thus identified point R-1 (Figure 14) as the point at which the line should be adjusted, since from there on:

the provisional equidistance line has an increasingly prominent effect on the seaward projection of the coast of Bangladesh, thanks to the maritime boundary it now has with Myanmar, until it cuts Bangladesh off entirely and terminates at a distance of roughly 250 nm from the coast where it meets that boundary set by the decision of the ITLOS.Footnote 103

The dissenting Arbitrator justified this conclusion by stating that ‘the exercise of a margin of appreciation by the majority may then appear more defensible as an exercise to achieve equity within bounds of law’.Footnote 104 Even then, according to Dr. Rao, from the point R-1 at which the line had an increasingly prominent effect on the seaward projection of the coast of Bangladesh, the cut-off effect did not come any closer to being extraordinary, unnatural, or unreasonable as demanded by the North Sea cases.Footnote 105 This part of the conclusion, however, seems not to be supported by the geographical reality of the area and it should be admitted that the cut-off effect at point R-1 is unreasonable. Between point Prov-4 and point Prov-5 of the equidistance line, the area allocated to Bangladesh narrowed distinctively, which should be remedied by adjusting the equidistance line. Ignoring the seriousness of such a cut-off would have amounted to ignoring the geographic reality and the ultimate goal of the maritime delimitation. On the other hand, the selection of point Prov-3 by the majority as the point at which the disadvantage materialized and the evidently more pronounced cut-off effect occurred may seem to be little supported by the geographic reality of the area (Figures 5 and 10). The Tribunal correctly noted that from point Prov-3 the line bent eastward, but that did not warrant the conclusion that it bent so markedly that the cut-off was unreasonable at this point. Hence it seems that the logic of the majority was influenced by the ‘need’ to extend the maritime projections and boundary of Bangladesh as far seaward as international law permits. Taking into account all the geographic circumstances of the case, as well as the equitable considerations described above, perhaps it seems fair to say that the pronounced cut-off effect occurred south of Maipura Point between point Prov-4 and point R-1. Here, at the point which lies along the parallel at which Maipura Point is situated, an adjustment of the provisional line was necessary to avoid an unreasonable cut-off effect to the detriment of Bangladesh; this would have a prominent effect on the seaward projection of Bangladesh while not encroaching too deeply on the entitlements of the eastern-facing coast of India. Such a hybrid line should have bent westwards with an azimuth which would have reflected all the equitable considerations.

Figure 14 Dr. Rao's maritime boundary, Concurring and Dissenting Opinion of Dr. P. S. Rao, at 23.

6. Delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 NM

The limits of the continental shelf of both states had been established neither in accordance with Article 76 nor Annex II to UNCLOS, which contains the provisions governing the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). Nevertheless, the Arbitral Tribunal confirmed its jurisdiction to decide on the lateral delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nm before its outer limits have been established.Footnote 106 Next, it emphasized that Article 76 embodies the concept of a single continental shelf and that, according to Article 77(1) and (2), a coastal state exercises exclusive sovereign rights over the continental shelf in its entirety. This is confirmed by Article 83 of the Convention concerning the delimitation of the continental shelf between states with opposite or adjacent coasts, which also does not differentiate between inner and outer continental shelves.Footnote 107 Finally, the Tribunal also noted ‘a clear distinction’ between delimitation of the continental shelf under Article 83 and the delineation of its outer limits under Article 76.Footnote 108

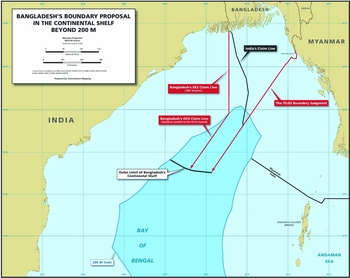

Both Bangladesh and India claimed entitlements to the outer continental shelf and they made submissions accordingly to the CLCS.Footnote 109 Bangladesh submitted that the concavity of the coast continued to constitute a relevant circumstance.Footnote 110 It argued that the equidistance line became more unreasonable as it moved further from the coast, and that India's proposed line would not produce an equitable result.Footnote 111 Therefore, the equitable boundary line, running along the 180° angle-bisector line ‘should bend and run along an azimuth of 214°42 parallel to the Bangladesh-Myanmar delimitation up to the outer limit of Bangladesh's continental shelf’.Footnote 112 This would accord Bangladesh a corridor out to the limits of its continental shelf and the eastern extent of that corridor would extend ‘until it reaches the area where the rights of third States may be affected’.Footnote 113 Bangladesh submitted that such a delimitation would correspond with the ‘maximum reach’ principle and would still retain India's entitlement of the substantial area beyond 200 nm to the south of the outer limit of Bangladesh's claim (Figure 15).Footnote 114

Figure 15 Bangladesh boundary proposal in the outer continental shelf, Reply of Bangladesh, Figure R5.7, at 145.

The Arbitral Tribunal started its delimitation exercise with a general observation that the jurisprudence regarding the delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nm is rather limited.Footnote 115 Second, it interpreted Articles 76 and 83 of UNCLOS and noted the ITLOS decision which ruled that the delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nm through judicial settlement had been in accordance with Article 76.Footnote 116 Third, the Tribunal pointed out that international jurisprudence does not recognize a general right of a coastal state to the maximum reach of their entitlements, irrespective of the geographical situation and the rights of other coastal states.Footnote 117 In this regard, it may be regretted that the Tribunal did not explain why the maximum reach principle should not be recognized in the law of maritime delimitation, especially because no court or tribunal has discussed the principle so far.

Last but not least, it considered that:

the appropriate method for delimiting the continental shelf remains the same, irrespective of whether the area to be delimited lies within or beyond 200 nm. Having adopted the equidistance/relevant circumstances method for the delimitation of the continental shelf within 200 nm, the Tribunal will use the same method to delimit the continental shelf beyond 200 nm.Footnote 118

Consequently, it assessed the appropriateness of base points and decided that one additional base point should be constructed on the coast of India. The equidistance line thus constructed continued from the intersection of the inner and outer continental shelf until it reached the maritime boundary between Bangladesh and Myanmar.Footnote 119 In this regard, the Arbitral Tribunal relied on the decision of the ITLOS considering the concavity of the coast as a relevant circumstance, and on the fact that the ITLOS-adjusted equidistance line delimiting the EEZ and the inner continental shelf continued in the same direction beyond the 200 nm limit.Footnote 120 It therefore indirectly confirmed that the Bay of Bengal constitutes a ‘single situation case’ and that the reasoning of North Sea is applicable to the present case.

7. Adjustment of the provisional equidistance line within and beyond 200 NM

The Arbitral Tribunal decided that, on account of the concept of a single continental shelf, any adjustment of the provisional line should be made cumulatively for the line both within and beyond 200 nm. In adjusting the line, the Tribunal was guided by the need ‘to ameliorate excessive negative consequences the provisional equidistance line would have for Bangladesh in the areas within and beyond 200 nm, but it must not do so in a way that unreasonably encroaches on the entitlement of India in that area’.Footnote 121

It further underlined that this exercise was to be performed in a reasonable and mutually balanced manner.Footnote 122 This standard is firmly entrenched in international courts and tribunals.Footnote 123 It reflects the obligation of a court or tribunal to draw such a delimitation line which would not excessively restrict the entitlements of adjacent or opposite states, generated by their coasts, to maritime areas. The standard preserves the maritime interests of adjacent or opposite states and is an equitable principle, since it realizes the primary objective, which is to reach an equitable solution.

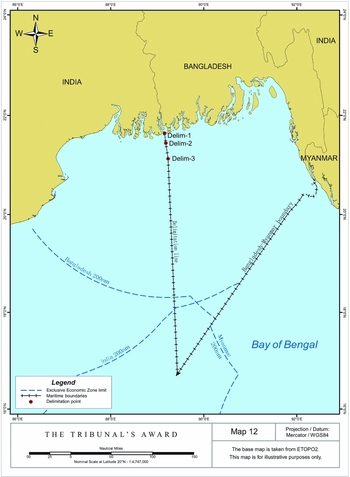

International case law shows that the process of shifting and adjusting the provisional equidistance line can be a long, complex, and also creative process.Footnote 124 However, in the present case the PCA Tribunal decided to apply a simple solution which, in its opinion, demanded little justification. It held that the provisional equidistance line should be deflected at point Prov-3 (Figure 16). Then it drew a geodetic line with an initial azimuth of 177° 30’ 00” until the line met with the maritime boundary established by ITLOS between Bangladesh and Myanmar,Footnote 125 which – as Dr. Rao prudently pointed out, ‘nearly matches a geodetic line connecting Delimitation Point 3 with the intersection of the ITLOS delimitation line and India's submission to the CLCS’.Footnote 126 In the Tribunal's view, such an adjusted line ameliorated the ‘excessive negative impact’ of the provisional equidistance line on the entitlement of Bangladesh to its maritime areas (Figure 17). At the same time, ‘the adjusted delimitation line does not unreasonably limit the entitlement of India’.Footnote 127 The Tribunal offered virtually no explanation for choosing the azimuth of 177° 30’ 00”. It only pointed out that its line avoided turning points and was thus simpler to implement and administer by the parties.Footnote 128 A similar straight line was also drawn by the ITLOS. It therefore seems that the simplicity of a delimitation line, which would enhance its implementation and administration, constitutes an element which has been considered by international courts and tribunals in adjusting a provisional line.

Figure 16 Adjustment of the provisional equidistance line, Award, Map 9, at 149.

Figure 17 The cut off of the projections from Bangladesh, Award, Map 8, at 145.

The selection of the azimuth of 177° 30’ 00” and the lack of sufficient explanation for this, as well as the proximity of the adjusted line to the bisector line, were both criticized by Dr. Rao. Referring to the first issue he opined that:

the simplistic explanation offered for this azimuth in the Award is highly unsatisfactory. This will be left, in the absence of any verifiable factors or criteria of what the Tribunal did, to one's imagination. This difficulty is compounded . . . by the fact that this azimuth effectively directs from Delimitation Point 3 the rest of the course of the final boundary line. If an azimuth of 177° 30’ 00” could achieve an equitable solution in the present case, why cannot an azimuth of 177° 20’ 00” or 177° 40’ 00” achieve the same objective?Footnote 129

A possible answer to Dr. Rao's questions may be the Tribunal's explanation, stemming from the relevant text of the Award, that the adjusted line with 1770 30’ 00” azimuth did not encroach unreasonably upon the entitlements of India, but it matched a geodetic line connecting Delimitation Point 3 with the intersection of the ITLOS delimitation line and India's submission to the CLCS, and therefore the maritime boundary thus drawn was simpler to implement and administer by the parties. Moreover, the majority was attached to the idea of extending the maritime boundary of Bangladesh as far seaward as international law permitted. Still it should be admitted that such an answer remains vague and unpersuasive. One may question whether the criteria applied by the Tribunal form a part of equitable principles governing the adjustment of a provisional line. They perhaps fulfil the ultimate objective of reaching an equitable solution, but the Tribunal should have reasoned and explained why and how the azimuth of 177° 30’ 00” negated the excessive negative impact and reflected such an equitable solution. As the Tribunal itself noted, transparency is also dependent on the reasoning given for any particular decision.Footnote 130 Therefore, the lack of explanation in choosing the above azimuth implies subjectivity and contributes to a lack of transparency. It cannot be justified merely by the margin of appreciation enjoyed by the delimitation tribunals. It seems that the Tribunal's aim to extend the prolongation of Bangladesh's coast as far seaward as international law permitted prevented it from considering other equitable principles which demanded application in the present case. The priority given to the extension of Bangladesh's coast overshadowed the discussion of other possibly relevant equitable considerations. Thus, Dr. Rao may have been correct when he noted that any simple wish to allocate to Bangladesh a reasonable and workable area for the purpose of exploring and exploiting the resources of its maritime zones must be justified by the general principles aimed at achieving an equitable solution. Otherwise the decision given may appear purely arbitrary and subjective.Footnote 131

The second point of criticism concerned the proximity of the 177° 30’ 00” azimuth to the 180° bisector line. In the view of Dr. Rao, it was unacceptable for the Tribunal to adopt an adjusted line that so closely approximated the 180° bisector. Therefore, the dissenting Arbitrator rejected the Tribunal's method of delimitation, considering it flawed.Footnote 132 To justify his point, he relied on the Separate Opinion of his co-arbitrator (Judge Cot) in Myanmar/Bangladesh, condemning ‘the re-introduction of the azimuth method deriving from the angle-bisector theory which results in mixing disparate concepts and reinforces the elements of subjectivity and unpredictability that the equidistance/relevant circumstances method is aimed at reducing’.Footnote 133

However, save for the argument of Judge Cot, who seemingly accepted the 177° 30’ 00” azimuth, Dr. Rao did not present any compelling reasons for regarding the adjusted line as flawed due to its proximity with the bisector line. In fact it is difficult to see why the proximity of the results generated by the two methods make the equidistance/relevant circumstances method flawed. Both methods usually produce similar results, causing the ICJ to refer to the angle-bisector method as ‘an approximation of the equidistance method’.Footnote 134 Thus, the mere proximity of results should not be regarded as a valid argument for the rejection of an adjusted equidistance line which approximates a bisector line proposed by one of the parties.

8. The third stage: The disproportionality test

The final step in the delimitation process is to conduct a disproportionality test in order to confirm that the provisionally determined delimitation line does not yield a disproportionate result. This test is conducted by comparing the ratio of the relevant maritime areas accorded to each state, to the ratio of the states’ relevant coastal lengths. The purpose of the third phase is ‘to ensure that there is not a disproportion so gross as to “taint” the result and render it inequitable’.Footnote 135 The PCA Tribunal adopted the same reasoning, thus confirming the previous case law. Having made these general remarks, the Tribunal reiterated that the length of the relevant coasts of Bangladesh and India were 418.6 and 803.7 kilometres respectively, producing a ratio of 1:1.92 in favour of India. The size of the relevant area amounted to 406,833 square kilometres. The relevant area allocated to Bangladesh was approximately 106,613 square kilometres, while that of India was 300,220 square kilometres, producing a ratio of 1:2.81 in favour of India.Footnote 136 The Tribunal then concluded that this ratio did not produce any significant disproportion in the allocation of maritime areas to Bangladesh and India that would require alteration of the adjusted equidistance line to ensure an equitable solution.Footnote 137

9. The grey area

The delimitation of maritime areas beyond 200 nm and the adjustment of the equidistance line may create a so-called grey area’. Such a grey area may appear only in an area of overlapping entitlements, and consequently there is no grey area problem if there are no such entitlements. Until the Award, the only instance of a grey area had occurred in the Bangladesh/Myanmar case. ITLOS explained that a grey area is created ‘when a delimitation line which is not an equidistance line reaches the outer limit of one State's EEZ and continues beyond it in the same direction, until it reaches the outer limit of the other State's EEZ’.Footnote 138 In the Bangladesh/Myanmar case, the grey area occurred where the adjusted equidistance line used for delimitation of the continental shelf went beyond 200 nm off Bangladesh and continued until it reached 200 nm off Myanmar (Figure 18). ITLOS indicated that the rights over the EEZ and the rights over the continental shelf are separable and that they can coexist.Footnote 139 For its part, the Arbitral Tribunal added that:

the resulting “grey area” is a practical consequence of the delimitation process. Such an area will arise whenever the entitlements of two States to the continental shelf extend beyond 200 nm and relevant circumstances call for a boundary at other than the equidistance line at or beyond the 200 nm limit in order to provide an equitable delimitation.Footnote 140

Accordingly, beyond 200 nm from its coast, Bangladesh has an entitlement only to the seabed and its subsoil pursuant to the legal regime governing the continental shelf. Within the grey area, Bangladesh has no entitlement to an EEZ.Footnote 141 Moreover, as the PCA Tribunal itself noted, its grey area overlapped in part with the ITLOS grey area, thus creating a ‘double grey area’, which potentially contains competing sovereign rights of three different states, in that Bangladesh has an entitlement to the continental shelf and both Myanmar and India have entitlements to their respective EEZs (Figure 19).Footnote 142

Figure 18 – The grey area in Bangladesh/Myanmar, supra Footnote note 5, at 138.

Figure 19 The ‘double grey area’, Award, Map 9, at 159.

Thus, the approach of ITLOS was substantially followed by the PCA Tribunal, which in fact contained three members who had adjudicated in the Bangladesh/Myanmar case. However, it met with the strong disagreement of Dr. Rao who labelled the creation of a grey area as ‘entirely contrary to the law and the policies underlying the decision taken in UNCLOS to create the EEZ as one single, common maritime zone within 200 nm which effectively incorporates the regime of the continental shelf within it’.Footnote 143 In a nutshell, the dissenting Arbitrator regarded the decision on the grey area issue as ill-conceived, since it created a ‘double grey area’, in which concurrent sovereign rights to the EEZ are to be exercised by Bangladesh and Myanmar. Within 200 nm, the legal regime of the EEZ and the continental shelf are united and the concept of EEZ refers both to the resources of the seas and to the natural resources on or in the seabed. It controls overlapping entitlements.Footnote 144 To this end, Dr. Rao rejected each argument developed by the ITLOS and, consequently, by the Arbitral Tribunal.

Dr. Rao's Opinion relied heavily on the authority of the Dissenting Opinion of Judge Evensen in the Continental Shelf case,Footnote 145 to conclude that ‘the sovereign rights of a coastal State over the water column and the seabed and its subsoil are considered as two indispensable and inseparable parts of the coastal State's rights in the EEZ’.Footnote 146 Moreover, within 200 nm the entitlement of coastal states rests solely on the distance criterion. Therefore, there is a unity of the legal regimes of the EEZ and the continental shelf within 200 nm.Footnote 147 Dr. Rao found support for this contention in the Libya/Malta case, in which the Court stated as follows:

[a]lthough the institutions of the continental shelf and the exclusive economic zone are different and distinct, the rights which the exclusive economic zone entails over the sea-bed of the zone are defined by reference to the régime laid down for the continental shelf. Although there can be a continental shelf where there is no exclusive economic zone, there cannot be an exclusive economic zone without a corresponding continental shelf. It follows that, for juridical and practical reasons, the distance criterion must now apply to the continental shelf as well as to the exclusive economic zone.Footnote 148

Thus, in the opinion of Dr. Rao the above statement negated any conclusions in the Award that the continental shelf is a single unit and that no distinct inner continental shelf and outer continental shelf exists.Footnote 149 However, a careful reading of the Libya/Malta case might suggest otherwise.

First, the Court later in the same paragraph noted that its previous observation did not suggest that:

the idea of natural prolongation is now superseded by that of distance. What it does mean is that where the continental margin does not extend as far as 200 miles from the shore, natural prolongation . . . is in part defined by distance from the shore, irrespective of the physical nature of the intervening sea-bed and subsoil. The concepts of natural prolongation and distance are therefore not opposed but complementary; and both remain essential elements in the juridical concept of the continental shelf.Footnote 150

This statement contradicts the conclusion arrived at by Dr. Rao that the entitlement of a coastal state is solely dependent on the 200 nm distance criterion. The Court emphasized that both criteria are equal and remain essential in the juridical concept of the continental shelf. Therefore, it may be fairly said that the legal regimes/basis of the EEZ and the continental shelf are not united. Moreover, the legal regimes of the EEZ and the continental shelf are governed by different parts of UNCLOS, which suggests that they are independent and separable, as confirmed by the Court in the Libya/Malta case.

Second, the Libya/Malta paragraph quoted in the Opinion of Dr. Rao does not necessarily mean that that there is no single continental shelf. The Court observed that the EEZ and the continental shelf are different and distinct, and at same time it also admitted that they are invariably connected in the sense that one cannot define and explain the concept of the EEZ and rights of coastal states therein without reference to the regime laid down for the continental shelf. This is supported by a reading of the relevant provisions of UNCLOS. According to Article 56(1)(a) of the Convention, in the EEZ a coastal state has rights to seabed and subsoil that also fall within the regime for the continental shelf.Footnote 151 Article 56(3) provides that the rights with respect to the seabed and subsoil of the EEZ are to be exercised in accordance with Part VI concerning the continental shelf, which includes Article 83. Moreover, Article 68 provides that Part V of UNCLOS concerning the EEZ does not apply to sedentary species of the continental shelf.Footnote 152 Pursuant to Article 77, the coastal state exercises its sovereign rights over the continental shelf for the purpose of exploring it and exploiting its natural resources, which consist of the mineral and other non-living resources of the seabed and subsoil, together with living organisms belonging to sedentary species. This proves that in practice the Convention distinguishes between the rights that arise under multiple regimes and those that pertain only to the EEZ.Footnote 153 Therefore, the adjusted line drawn by the Tribunal creating the grey area delimits only those rights of India and Bangladesh as specified in Article 77. Other rights under the regime laid down for the EEZ are not affected by the boundary line in the grey area and are enjoyed solely by its coastal state, as these rights pertain only to the EEZ.

ITLOS added that the legal regime of the continental shelf has always coexisted with the legal regime of the high seas, and it underlined that this is also possible with respect to its coexistence with the legal regime of the EEZ.Footnote 154 According to Articles 58 and 78 of UNCLOS, each coastal state must exercise its rights and perform its duties with due regard for the rights and duties of the other coastal state(s) and may not infringe or engage in any unjustifiable interference with navigation and other rights and freedoms of other states as provided for in UNCLOS.Footnote 155 To support these contentions, the ITLOS went on to indicate that:

[t]here are many ways in which the Parties may ensure the discharge of their obligations in this respect, including the conclusion of specific agreements or the establishment of appropriate cooperative arrangements. It is for the Parties to determine the measures that they consider appropriate for this purpose.Footnote 156