Introduction

Citizenship is a core concept of Western political thought. Modern political theories display an “overlapping consensus” that citizens should be treated as “free and equal persons” entitled to roughly equal forms of citizenship (Alejandro Reference Alejandro1993, 223; Rawls Reference Rawls1985, 227; Watson and Hartley Reference Watson and Hartley2018, 1–3; Wilson Reference Wilson2019, 23–25).

There is much less agreement over what constitutes “equal citizenship” and how to achieve it. Many scholars define citizenship as a “legal status with associated rights and duties of those who are full members of a community”—with civic equality defined chiefly by whether citizens all formally “enjoy the same rights” (Heater Reference Heater1999, 82–83; Kallio, Wood, and Häkli Reference Kallio, Wood and Häkli2020, 713). Others think that legal citizenship rules often overstate or understate the meaningful possession of rights, the senses of belonging, and the practical agency of many residents, so they are unreliable indicators of true civic equality (e.g., Dalton Reference Dalton2014, 26; Jašina-Schäfer and Cheskin Reference Jašina-Schäfer and Cheskin2020, 95–97). They focus on the “lived citizenship” of persons as “it is experienced and enacted in various real-life contexts,” and gauge civic equality by whether persons experience “economic, political, and social esteem,” or equal civic “standing,” in their everyday lives (Kallio, Wood, and Häkli Reference Kallio, Wood and Häkli2020, 713; Shklar Reference Shklar1989). Here “equality” does not imply identical wealth, political influence, or social prestige. It means what many call “equity”: secure possession of enough of those things for persons to be widely seen as, and to feel themselves to be, civic equals.

Most scholars of “lived citizenship” concede, however, that while many cultural and economic factors shape citizenship experiences, citizenship laws “have a profound effect” on the “political, economic, and moral resources” of citizens (Kallio, Wood, and Häkli Reference Kallio, Wood and Häkli2020, 714, 724). Most analysts of civic legal provisions agree, in turn, that laws should aid, not impede, equitable forms of lived citizenship. Discerning whether citizenship laws foster unjust inequalities requires both specific knowledge of legal provisions and empirical assessments of civic experiences. It thus makes sense to unite these two views of citizenship within a shared theoretical framework. A useful framework must include, first, a conceptualization of a society’s legal structuring of citizenship and, second, criteria for ascertaining whether lived citizenships are equitable.

Using the example of the United States, this paper lays out such a framework. It conceptualizes how a society legally structures citizenship by designating the entirety of the national, state, and local citizenship laws that exist at any one time as that society’s “civic order.” Pertinent laws include those governing the acquisition and relinquishing of citizenships and, following T. H. Marshall, those establishing civil, political, and social rights (which Marshall hoped might counterbalance inequalities arising from capitalist property rights) (Marshall Reference Marshall1950).

Constitutions of federated societies like the US also grant state and local governments significant discretion in making some citizenship laws. The resulting variations in state and local citizenships are constitutive features of those nations’ federated civic orders (cf. Colbern and Ramakrishnan Reference Colbern and Ramakrishnan2021, 53–54).

Legal civic orders are thus complex. Their effects are often disputed or misapprehended. How can we assess, both empirically and normatively, how far they help people to achieve equitable “economic, political, and social esteem” in lived citizenships? The framework draws on Nancy Fraser’s argument that analysts should examine equality along three dimensions: material resource distributions, political representation, and social recognition (Fraser Reference Fraser2009). Similarly, the framework suggests three criteria for judging whether a civic order contributes to equitable lived citizenships. First, for representation, whether those occupying distinct legal categories of citizenship have had appropriate opportunities for political voice in creating those categories, or exiting from them. Second, for resource distribution, whether civil and social rights, however varied, combine to aid all citizens to gain needed material resources. Third, for recognition, whether a state has acknowledged the effect of its past and present coercive policies on distinct categories of persons by providing them with appropriate forms of aid and accommodations.

To show the value of this theoretical framework, the paper deploys it to make two arguments on major questions of citizenship.

First, addressing normative debates over the propriety of “differentiated citizenships,” the framework demonstrates why societies like the US should not aspire to create civic orders that assign identical bundles of legal rights and duties to most persons (Young Reference Young1990, 25; cf. Barry Reference Barry2000, 9–13). The complexities of civic orders show that only citizenship laws that place differently situated persons into appropriately differentiated categories can hope to foster lived experiences of civic equality. Normative analyses should focus on the demonstrable consequences of civic differentiations, not abstract ideals of uniformity.

Second, social scientists disagree on the concepts and methods suitable for assessing such consequences. The framework supports those who argue for intersectional analyses of human experiences, and for plural, quantitative and qualitative methods of inquiry. Because civic orders like that of the US use categories of race, sex, occupation, religion, age, and more to define the varying rights and duties of different sets of citizens, studies of their effects must consider the effects of multiple intersecting categories. Because experiences of lived citizenships have both subjective and objective dimensions, observational and interpretive research must accompany studies of formal rights and quantitative measures of material conditions. By aiding multimethod inquiries into how intersecting civic provisions contribute to distinct lived citizenships, the framework can help scholars identify both existing and emergent sources of civic inequality, as well as policy changes needed for civic progress.

The Components of a Civic Order

Building on multidisciplinary studies of “institutional orders,” this paper argues that every modern political society has a set of laws governing citizenship that can be seen as that society’s “civic order” (cf. Scott Reference Scott2014). Its components are crafted by competing political coalitions at different levels of governance in order to advance their agendas. Consequently, civic orders often embody conflicting ideas of citizenship, complicating the effects of particular rules and of a civic order as a whole. Even so, in part because states seek to render their populations legible, civic orders generally provide three types of formal legal structuring for their citizenships:

-

1. Legal modes of acquiring and terminating citizenship.

-

2. Legally defined duties and rights of citizenship, civil, political, and social.

-

3. Legally defined relationships of citizenship in one political community to citizenships in others within and beyond its bounds, as in the multilevel relationships among city, state or province, and national citizenships; dual national citizenships; and memberships in international regulatory bodies.

Though states seek ease of administration, legal modes of acquisition and loss of citizenship are often numerous and rights and duties of citizenship vary greatly among the different categories of citizenship that laws enact and across the interrelated political communities to which persons belong. Legal rules governing citizenship are also frequently contested, and modifications often emerge from compromises among proponents of partly shared, partly contrasting ideas. Sometimes citizenship rules are legacies from past eras that current actors do not favor but cannot agree to alter. Moreover, groups seeking to shape citizenship laws may have as their chief motives economic, partisan, racial, gendered, religious, or other concerns, not the structuring of citizenship per se. So the civic order that a nation has in place rarely reflects the ideal of equal citizenship of any one group or political party. Civic orders are usually elaborate, internally inconsistent, difficult to see whole, and subject to change. That may be why scholars have not taken them as units of analysis.

Nonetheless, we can always identify the past and present legal structuring of citizenship, the civic order, that governing institutions have formally established. Analyses of the effects of both a civic order as a whole and its component provisions are vital for exploring major sources of people’s widely varying lived experiences of citizenship. To be sure, those experiences have other sources, and scholars may reasonably choose to focus particular studies on one citizenship law, level of government, or aspect of lived citizenship. Such studies can benefit, however, from knowing how other elements of the civic order may shape citizenship experiences in diverging ways. The example of the United States shows how many consequential civic provisions may otherwise go unrecognized.

The Twenty-First Century American Civic Order

America’s founders were the first to confront the tasks of constructing citizenship in a large state that was defining itself as a federated republic. They also claimed authority to govern imperially many contiguous and, eventually, overseas peoples and territories. They did so with a sometimes reluctant, too often fervent embrace of existing hierarchical structures of class, race, gender, sexuality, and religion that involved systemic subordinations, exploitation, and exclusions, including inegalitarian structures of citizenship. Many groups contested those hierarchies in the name of equal citizenship from the nation’s start, and the original inegalitarian civic structures have since been altered, though never eradicated. As a result, Americans have inherited elaborate legal specifications of their civic order that they have never ceased to modify.

What different categories of citizens do these provisions governing its legal acquisition and termination create? What are their consequences for lived citizenships?

The Census Bureau’s American Community Survey estimates that in 2018, the residential population of the United States was 327,167,439. As shown in Table 1B, more than 93.2% of those residents, 305,068,455 persons, were citizens, joined by 22,098,984 noncitizen residents, just over 6.7%. Native-born Americans were over 86% of total residents (282,438,718), though a bit under 2% of these native-born citizens (5,318,810) were born outside the US to at least one citizen parent. Another 22,629,737 persons, 7.4% of all citizens, instead gained their citizenships via naturalization (data.census.gov).

Tax data on for-profit and nonprofit corporations suggest that in 2018 the US also had roughly 11.5 million business corporations and 1.6 million nonprofits eligible to be jurisdictional citizens (Duffy Reference Duffy2019; Internal Revenue Service 2019). No one contends that the jurisdictional citizenship of corporations is or should be identical to human legal citizenships. Still, the civic rights and powers granted to corporations matter greatly for many persons’ lived citizenships (Pistor Reference Pistor and Urban2014). Many corporations have more wealth, more political voice, and more social standing than most individuals, who feel their citizenships diminished in comparison.

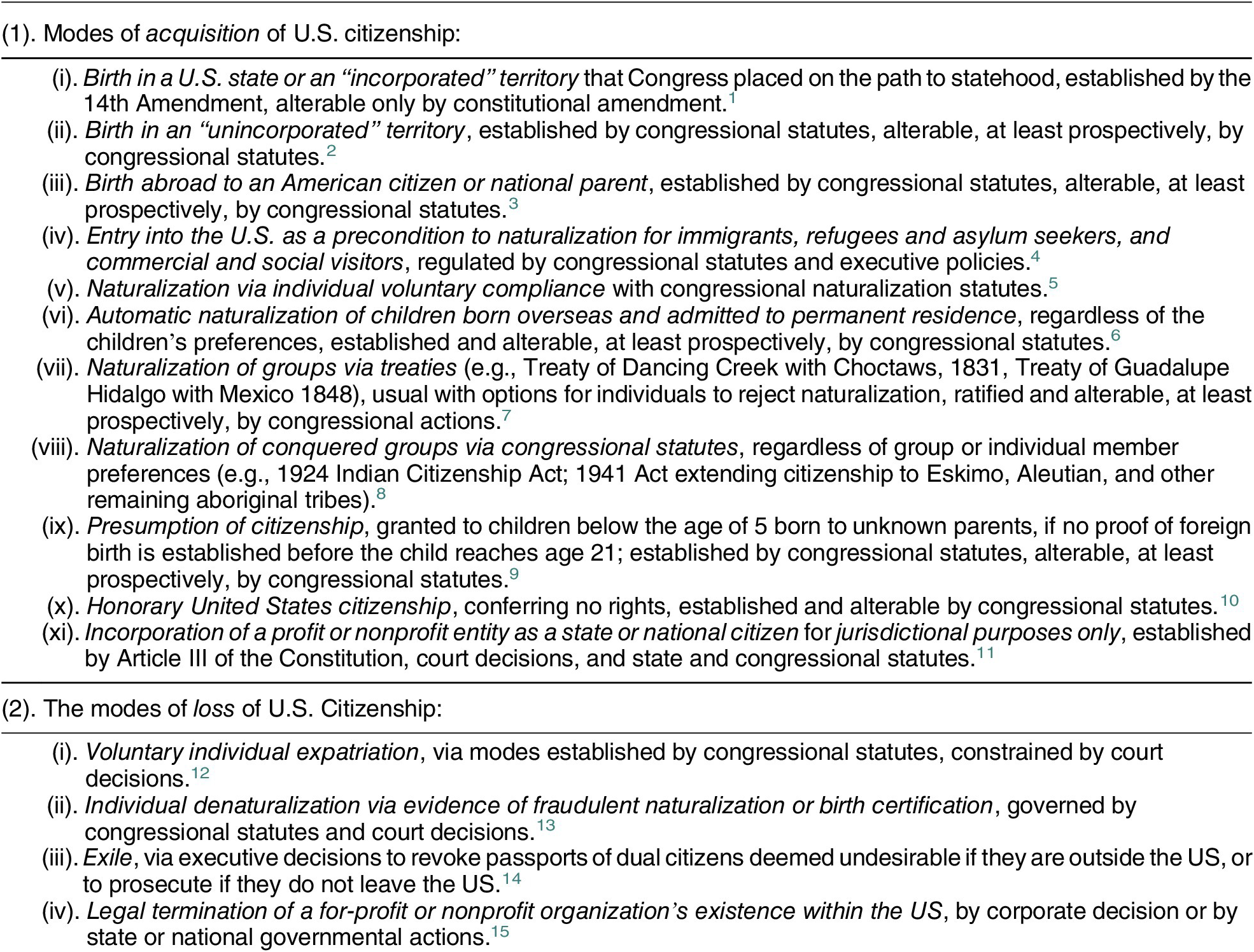

Table 1A. Components of America’s Civic Order: Acquisition and Termination of U.S. Citizenship

Table 1B. U.S. Citizens and Residents by Mode of Acquisition

The different modes through which people acquire citizenship have major consequences. Citizens born in the territories and indigenous tribes have statutory-based citizenships that can be altered more easily than those based on the 14th Amendment, a fact that can render their lived citizenships less secure. Both naturalized citizens and those born to citizen parents outside the US face still greater vulnerabilities. Although naturalized citizens possess most of the same opportunities as birthright citizens, they are constitutionally ineligible for the Presidency, and the eligibility of persons born to citizen parents outside the US is uncertain. For most, this disadvantage is symbolic; but it fueled the Obama “birther” controversy and kept Arnold Schwarzenegger and others from pursuing the nation’s highest office. More significantly, if the government finds even accidental errors in the documents through which citizens obtained naturalizations or in their certificates of birth to a citizen parent abroad, they can lose their citizenship. That danger increased when the Trump Justice Department created a Denaturalization Section to use such powers aggressively (Benner Reference Benner2020).

The U.S. Constitution and many public policies confer rights and benefits on persons, not just citizens. Some may deem such rights and benefits not to be part of the legal civic order. They do mean that even loss of legal citizenship is not always decisive for experiences of lived citizenship. Yet whether or not legal rights and benefits are restricted to citizens, provisions that burden or aid some categories of persons more than others, such as variations in eligibility for health care, often burden or aid some legal citizens more than others. Many feel such policies render their legal citizenships “second-class” (Chen Reference Chen2020, 125–126).

Especially since 1996, moreover, many federal programs that provide social benefits have confined eligibility to citizens or to citizens and permanent residents.Footnote 16 Those restrictions have heightened the importance of loss of citizenship, since it can mean loss of vital health and welfare aid as well as voting rights. Contemporary theorists and policy advocates differ sharply over the legitimacy of these policies (Voss, Silva, and Bloemraad Reference Voss, Silva and Bloemraad2019). In 2018, the number of U.S. citizens bearing these vulnerabilities, 27,948,547, was 9.16% of the citizenry.

At the same time, many naturalized citizens and citizens born abroad to American parents are eligible to hold dual or multiple national citizenships. By inheritance, many of their U.S.-born children can do so as well. The U.S. does not count how many citizens hold dual citizenships, but tens of millions have the potential to do so. On rare occasions, the U.S. government has threatened to revoke the passports of dual citizens who have gone abroad, or to prosecute them if they return, effectively exiling them. More often, analysts criticize dual citizenships for conferring what they call unfair advantages. They contend that dual citizens, especially those who gained naturalization with the aid of wealth or special skills, have opportunities others lack to shift nations and to shirk duties like military and jury service and, less often, taxes—making their citizenships more than equal (Caldwell Reference Caldwell2020; Tanasoca Reference Tanasoca2018).

Turning to laws that embody Marshall’s typology of civil, political, and social rights and duties, Table 2A shows that legal variations among citizens abound. U.S. laws delineate rights and categories of rights bearers far more elaborately than they do civic duties. However, even legal duties are subject to exceptions that create major differences in lived citizenships. As seen in Table 2B, age differentiations are broadly effective. In 2018, just under a quarter of U.S. residents (71,503,164) were under 18 and too young to vote in national elections or do military or jury service. Although this differentiation is one most citizens live to overcome, it still can foster feelings of frustrating inequality, especially during national elections and wartimes. The appropriate age for disfranchising younger citizens has long been disputed, with the age lowered to 18 in 1971. Today some theorists argue for further extending youth voting, though others hold that current legal structures render the lived citizenships of children appropriately different but equal (Peebles Reference Peebles2019; Rehfeld Reference Rehfeld2011, 158–159; cf. Kallio, Wood, and Häkli Reference Kallio, Wood and Häkli2020, 718–719).

Table 2A. Duties and Rights of U.S. Citizenship

Table 2B. Population Categories with Varying Civil, Political, and Social Rights

In 2018, just over 16% of the total residential population, 52,423,114 persons, were 65 years or older. Historically, many senior citizens in America suffered physical and economic hardships that gave them sharply inferior experiences of citizenship. Especially since the New Deal, however, American public policies have granted seniors rights that other categories of citizens do not possess, improving their economic conditions and social standing, and heightening their political participation (Campbell Reference Campbell2005). America’s civic order assigns seniors lesser tax liabilities and makes them eligible for health and welfare benefits and free or reduced-price public services that are not available to those younger, and seniors receive military and, at times, jury service exemptions.Footnote 28 Though most see these privileges as equitable, earned by contributions seniors have made over many years, analysts do contest, for example, why wealthy seniors should receive Social Security benefits, partly subsidized by general taxes (Butler Reference Butler2016). Counting both younger and older residents, roughly 38% of the 2018 population had civil, political, and/or social rights and duties that varied from those of others based on age categories alone.

The U.S. civic order includes many other differentiators in civil, political, and social rights that are far more controversial, though many are efforts to help citizens to whom American governments have long denied equitable opportunities. The Census Bureau collects data using two “sex” categories, biologically male or female, and six “racial” categories—white, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian and Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, and other, with the option of indicating multiple races, as well as two “ethnic” categories—“Hispanic or Latino” and “Not Hispanic or Latino.” The Bureau expressly says it does so because government agencies use these data to structure social rights of citizenship, including education, employment, and health care (U.S. Census Bureau 2017). Those policies seek to provide all citizens with economic, health, and educational resources they need to offset disadvantages, especially those fostered by capitalist dynamics and by discriminatory practices. Because American inequalities are massive, the resulting variations in the rights that different categories of citizens possess are substantial.

For example, the Census Bureau identified 50.8% of all adult Americans in 2018 as women, 166,049,288, and their sex alone made them legally eligible for special treatment through affirmative action programs, often for public-sector jobs confined to citizens, as well as for various social rights.Footnote 29 Women were also not required to register for military service.Footnote 30 Of the 96.6% of American residents who identified themselves as having one race (315,887,408), 19%, or 59,763,631, classified as Hispanic or Latino; 13.2%, or 41,617,764, as African American; just under 1%, or 2,801,587, as Native American; and 0.2%, or 626,054, as Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islanders. All of these groups had federal civil rights, including affirmative action eligibility and in some case property and political rights, distinct from those of the 74.7% of Americans who identified as white (236,173,020), and many, though not all, of the 5.8% who identified as Asian Americans (18,415,198).Footnote 31 Another 3.4% of Americans, 11,280,031, saw themselves as belonging to two or more races, raising ambiguities in their eligibility for employment, education, and health and welfare programs. Debates over the propriety of assigning any benefits or burdens to citizens based on race, ethnicity, or gender have long been fierce (Urofsky Reference Urofsky2020). Most turn on claims about the effect of these policies on lived citizenships, with advocates contending these measures help overcome disadvantages often imposed by public policies and critics insisting that such measures transform nonbeneficiaries into victimized second-class citizens.

Several other differentiators are notable for their legal recognition in America’s civic order. In 2018, 4,917,954 persons were institutionalized in American federal, state, or local correctional, health, or long-term care facilities (data.census.gov). Their civil rights were protected by the Constitution, by the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act of 1980, and other statutes, but they were still legally subject to many punitive and health-related restrictions (U.S. Department of Justice). Moreover, out of a total civilian noninstitutionalized population of 322,249,485 in 2018 (98.5% of the total population), 40,637,764 persons (12.6%) had physical or cognitive disabilities (data.census.gov). Many federal laws provide these persons with rights against discrimination as well as special medical, educational, housing, and insurance assistance to combat their long-standing experiences of legally disadvantaged and stigmatized citizenship.Footnote 32 The forms of aid include accommodations in public education and employment that other citizens cannot claim, so again they sometimes face controversies over whether these “special rights” violate equal citizenship (Simplican Reference Simplican2015).

In 2018, just under 18 million Americans (7%) were military veterans (data.census.gov). They and often their families were eligible for numerous special benefits including life and health insurance and health care, educational, vocational training, and housing assistance, financial and legal counseling, and priority in public employment (U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs 2020). Many Americans see these benefits as appropriate rewards for public service and often as necessary to overcome disadvantages and disabilities incurred during service contributions. Veterans’ benefits have, however, sometimes been controversial, particularly when denials of opportunities for military service have compounded the inequalities in employment and educational opportunities experienced by African Americans, LGBTQ+ Americans, and women or when military benefits have been provided unequally on the basis of sex, policies that the Supreme Court has held unconstitutional (Frontiero v Richardson, 411 U.S. 685 [1973]).

The Census Bureau does not collect data on two other major differentiators, sexuality and religiosity, though the 2020 Census enabled persons to indicate they are in same-sex relationships. The Gallup Poll estimates that 4.5% of Americans are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender, but many believe the percentage is higher (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2019). Through much of American history, the lived citizenship of persons with nonconforming sexualities was highly unequal, marked by felt necessities to remain in the closet or face brutal discrimination (Canaday Reference Canaday2009). In recent years, the Supreme Court has upheld constitutional rights to same-sex intimacy and same-sex marriages and the applicability of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights to LGBTQ persons, protecting against much employment discrimination. However, states vary in other protections against antigay discrimination, with only 21 states having laws covering housing as well as employment and 20 including places of public accommodation (Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2019). Though public opinion has shifted in favor of gay rights, antidiscrimination bans remain hotly contested, especially by religious conservatives (Koppelman Reference Koppelman2020).

As shown in Table 2C, the Pew Research Center’s Religious Landscape Study estimates that 70.6% of American residents identify as Christians, with 25.4% Evangelical Protestants of different sorts, 14.7% identifying with different Mainline Protestant denominations, 6.5% with historically Black Protestant groups, 20.8% as Catholic, 1.6% Mormon, 0.8% Jehovah’s Witnesses, and 0.5% Orthodox Christians. About 5.9% of Americans espouse other faiths. Jews comprise 1.9%, Muslims 0.9%, Buddhists 0.7%, Hindus 0.7%, and 1.8% other world religions or other faiths (Pew Research Center 2020).

Table 2C. Members of Groups Eligible for Legal Religious Benefits

Recognizing how central religions are to millions of people, America’s civic order has long provided such religious groups with many exemptions and accommodations under federal, state, and local laws. Supreme Court decisions also insist that public policies must not make any persons feel like they are not “full members of the community” because of their religious views (Lynch v. Donnelly, 465 U.S. 688 [1984]). Different religious groups claim different forms of special treatment. Some seek exemptions from military service, others from public education. Many want tax-exempt bond financing and rights to receive tax-deductible contributions, and some, exemptions from paying Social Security taxes. Most want exemptions from bans on religious discrimination in employment and from copyright laws in religious performances. Some seek exceptions in regulations governing animal slaughtering and food preparation. All these exemptions and accommodations represent civil rights not shared by nonreligious citizens.Footnote 33 Many spur disputes about whether they help achieve equitable lived citizenships for religious adherents disadvantaged by public policies reflecting different moral traditions or whether they unduly privilege religious believers (Gill Reference Gill2019).

American governments do not legally assign people to different jobs. Social rights have, however, often been differentially distributed by occupation: agricultural and domestic workers were originally excluded from Social Security programs, exacerbating racial, gender, and economic inequalities in lived citizenships (Lieberman Reference Lieberman2001; Mettler Reference Mettler1998). Many economic actors have long fought for public aid to gain resources needed for civic standing. Policy makers have particularly seen farmers as facing special economic challenges that justify subsidies, loans, and crop insurance—measures that some praise as appropriate forms of social welfare and others denounce as inefficient, unjust privileges (Bakst Reference Bakst2018).

Similarly, though criminal justice laws apply to persons, not citizens per se, they do affect citizens’ civil, political, and social rights, both during and after incarceration. Because the Constitution largely leaves qualifications for voting to the states, federal laws do not directly disfranchise those subject to federal, state, and local criminal justice systems, and the Census Bureau does not track the limits on citizenship rights that state and local policies impose. The Sentencing Project estimates, however, that in 2020, 5.17 million American citizens were disfranchised due to a felony conviction, roughly 2.3% of the voting population, with African Americans disfranchised at more than three times the rate of non-African Americans (Uggen et al. Reference Uggen, Larson, Shannon and Pulido-Nava2020). Most states also deny convicted felons the right to serve on juries; they are ineligible for, or compete poorly for, many public and private jobs; if on probation, they face other restrictions; and they may be ineligible for various federal and state grants, public housing aids, and social benefits including SSI, food stamps, and more (Spengler Reference Spengler2020). The number of Americans with felony convictions is hard to estimate, but the major recent study placed it at roughly 8% of the total population, or over 26 million people (Shannon et al. Reference Shannon, Uggen, Schnittker, Thompson, Wakefield and Massoglia2017). Deservedly or not, most of those with felony records experience highly stigmatized lived citizenships along economic, political, and social dimensions.

In sum, the civil, political, and social rights in America’s civic order have profound effects on lived experiences of citizenship that vary greatly according to the legal categories that differently situated citizens occupy.

These variations are further multiplied because the American civic order also creates “multilevel” forms of citizenship (Maas Reference Maas, Schachar, Bauböck, Bloemraad and Vink2017). It recognizes persons as simultaneously citizens of local governments—towns, cities, school districts, and counties; as citizens of states or territories or indigenous tribes; and as citizens of the United States, which in turn has placed its citizens under the limited governance of some international organizations and which now accepts dual national citizenships. Governed by the U.S. Constitution, all these intersecting citizenships form parts of the American civic order, but their diversity further contributes to staggering variances in lived citizenship.

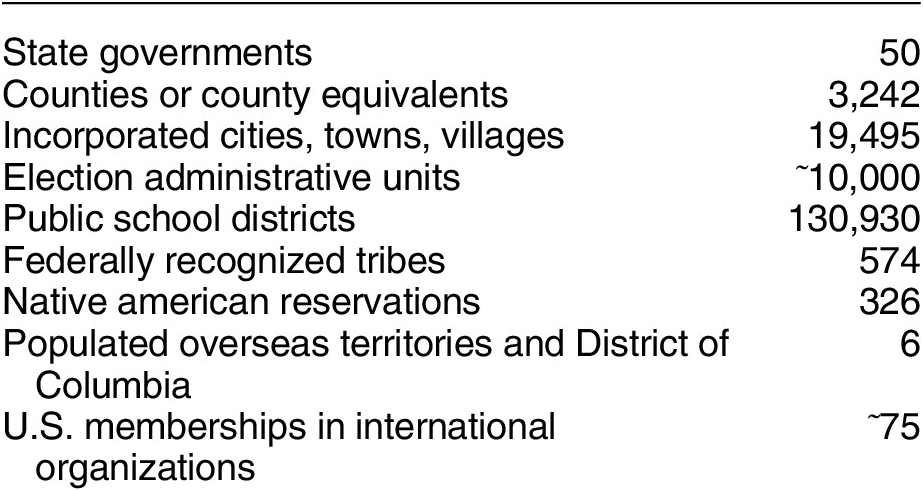

As shown in Table 3B, in 2018, U.S. citizens lived in 50 states; 3,242 counties or county equivalents; 19,495 incorporated cities, towns, and villages; about 10,000 election administration units; 130,930 public school districts; 574 federally recognized Indian tribes, located in 36 states; 326 Indian reservations; and 5 overseas territories, along with the District of Columbia (U.S. Census 2020; World Population Review 2020). The US also participates in over 75 international organizations, some of whom, like the World Trade Organization and the Agreement of the US, Mexico, and Canada (USMCA), include dispute resolution bodies that the US usually treats as having binding governing powers. These organizations form limited but significant transnational political communities to which U.S. citizens belong.

Table 3A. Rules Governing Relationships of U.S. citizenship with other Citizenships

Table 3B. Political Communities within and beyond U.S. Citizenship

These intertwined political communities vary enormously. In 2018, state populations ranged from 39,557,045 for California to 577,737 for Wyoming. States range in size from the 94,743 square miles of Alaska to the 191.3 square miles of West Virginia. Differences abound in their geographies, economies, demographics, historical traditions, and their modern partisanships. Differences within many states are almost as immense. Of the incorporated localities, 14,768 had populations below 5,000. About 40% of U.S. residents lived in cities of 50,000 or more. Of those, 310 cities had populations of 100,000 or more and 10 cities had populations above 1,000,000 (World Population Review Reference Butler2020).

Under the Constitution and federal statutes, states and local governments have wide discretion over the provision of civil, political, and social rights to their residents. Their policies often do more to shape those residents’ everyday civic experiences than national ones, especially since some U.S. cities have issued “municipal identification cards” that help locals get access to a range of institutions and services, including libraries, schools, banks, and supermarket and pharmacy discounts regardless of their national citizenship status (Hirschl Reference Hirschl2020, 166–167). As a result, bearers of municipal IDs can feel they have real local “economic, political, and social esteem” even when they are not legal citizens.

Analysts of American citizenship must therefore explore how state and local governments structure many rights—including voting rights and educational, financial, nutritional, housing, and medical programs—in startlingly different ways. Although the federal government provides roughly 65% of the funds for public welfare expenditures, state and local decisions shape whether and which citizens get these funds and how much. In 2017, for example, Massachusetts spent the most per low-income resident on welfare programs, $14,346, while Georgia spent the least, $3,310. Under the Affordable Care Act, 36 states and the District of Columbia accepted Medicaid expansion, but 14 states did not, acting as veto points on this national health initiative, as on many other policies (Buettgens Reference Buettgens2020). There are also 130,930 public school districts in the US that structure civic education in markedly different ways (Riser-Kositsky Reference Riser-Kositsky2020). Educational funding levels, sources, and formulas vary sharply. New York has the highest per-pupil expenditures, more than $12,400 greater than Idaho, the lowest (Baker, Farrie, and Sciarra Reference Baker, Farrie and Sciarra2018, iv).

Differences are just as great with respect to political rights. There are over 10,000 “election administrative units” in the US, usually counties but sometimes cities or townships, often led by elected partisan officials (National Conference of State Legislatures 2020). They authorize registration rules, polling locations and hours, voting equipment, and vote counting, with limited state or federal oversight, even in national elections. Citizens in one county can fail to get votes cast and counted that would be recorded in another (Hale, Montjoy, and Brown Reference Hale, Montjoy and Brown2015, 38–43). Again, every state except Maine and Vermont restricts felon voting, leaving between five and six million U.S. citizens disenfranchised (Hale, Montjoy, and Brown Reference Hale, Montjoy and Brown2015, 161–6). Requirements for jury service also differ widely, as do state and municipal tax policies. Corporate jurisdictional citizens cannot vote but have standing to litigate and rights of political expression.

Variations are even more extensive for citizens who live in the District of Columbia or America’s overseas territories, or who belong to indigenous tribes. DC citizens can vote for president and vice president but have no voting representation in Congress. Territorial citizens cannot vote for any national office; they have distinctive tax, trade, and civil rights and duties, and they vary in their eligibility for federal social programs. Treaty provisions can give Native American tribes special rights to natural resources, business opportunities, social benefits, and self-governing powers, but like the District and the territories, they are more subject to congressional governance than the 50 states (Aleinikoff Reference Aleinikoff2002). All these variances greatly affect persons’ lived citizenships, including many that seem inconsistent with civic equality (Stahl Reference Stahl2020). Recently, litigation efforts have intensified to persuade courts to overturn what territorial advocates denounce as the “second-class status” of citizens of “so-called unincorporated territories like Puerto Rico, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands,” as well as American Samoa and the Northern Mariana Islands (Fitisemanu v. US., U.S. D.Ct. Utah, 1:18-cv-36 [2019]; Knight Reference Knight2019).

Criteria for Appropriate Differentiations

The effect of some citizenship provisions, like racial and gender categories, on equal lived citizenships have long been disputed. The effects of others, like disability disqualifications and corporate jurisdictional citizenships, have often been overlooked. To advance understanding, analysts need some general criteria to guide empirical investigations and normative judgments of when citizenships are unduly unequal. Existing legal and political theories suggest partial answers, but the realities of civic orders show more is needed. The preeminent U.S. legal requirements for equality are the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment and the equal protection component the Supreme Court discerns in the due process clause of the 5th Amendment. Constitutional equal protection applies to both citizens and persons, but it does not demand that all be treated identically. Instead, Section 5 of the 14th Amendment empowers Congress to enforce equal protection through “appropriate legislation.”

Current Approaches to Legal Equality

Public law scholarship displays a sharp clash over how to decide what legal differentiations are “appropriate” (Hutchinson Reference Hutchinson2017). The two main camps are, first, “antidiscrimination” or “anticlassification” approaches, which focus on whether officials have intentionally used legal classifications that make invidious distinctions between groups (Dworkin Reference Dworkin1986, 381–97). Examples include the use of racial, sex, or religious classifications to restrict, especially, rights deemed fundamental. The rival camp is “antisubordination” or “antidomination” approaches, which focus on whether officials have acted in ways that perpetuate, rather than alleviate, unjust hierarchies, whatever their intentions or the classifications used (Coker Reference Coker1986). Examples include employment and criminal justice policies that disproportionately disadvantage people of color, whether or not they are meant to do so.

Both these approaches are valuable, but they are not sufficient to answer all questions of when and why differentiated citizenship categories are appropriate. Antidiscrimination advocates are right to reject the intentional use of legal classifications to create second-class citizenships. Antisubordination advocates are right that this rejection is not enough to reform many policies and practices that have severe inegalitarian effects, purposeful or not, on the lived citizenships of many persons.

Antidiscrimination theorists focus, however, on those legal differentiations in citizenship they suspect are intentionally invidious. Antisubordination theorists focus on those that operate either to reinforce or to resist systems of subordination and domination. Civic orders contain many legal differentiations whose objectives and effects are not captured by either focus. They are instead efforts to further individual and social goals widely seen as legitimate. Small children are exempt from jury duty chiefly because they would impede the civic work to be done. Seniors receive discounts out of regard for the civic contributions they are thought to have made. Religious pacifists are relieved of military service due to respect for morally conscientious lives. The granting of citizenship for jurisdictional purposes to nonprofit corporations like children’s theaters partly reflects desires to foster socially valuable activities. Variations in county election systems often arise from experiments with new technologies for convenient, accurate elections, not partisan ploys.

More broadly, American federalism generates many differences, especially in social rights to programs like Medicaid, which make many feel they have “second-class citizenship” (Michener Reference Michener2018, 3). Analysts of civic orders must question how desirable federal systems are from the standpoint of equitable lived citizenships. Yet variations in state and local social policies can arise from legitimately diverse democratic decisions in different communities. However, even when differentiated rights and duties do not reflect invidious intentions, even when they are not parts of systems of subordination, even when they target salutary goals, we must still ask whether they are ineffective or costly in ways that impede equitable citizenships for all.

To do so, empirical and normative inquiries must focus on whether a civic order’s civil, political, and social rights, as structured and constrained by laws governing acquisition and loss of citizenship and multiple intersecting citizenships, provide real opportunities for all citizens to gain the “political, economic, and moral resources” that scholars of lived citizenship rightly deem essential to “economic, political, and social esteem.” Fraser’s typology of equality’s dimensions as “redistribution, recognition, and representation” is a useful starting point, but a grasp of civic orders suggests further specifications of how to assess whether these goals are being met for different categories of citizens (Fraser Reference Fraser2009, 6, 104–5). As examples:

(i). Representation: Voice and Exit. Political representation via participation in elections and office holding is crucial for full citizenship. Awareness of how civic orders place groups of citizens in distinct categories indicates, however, that people need opportunities for what Albert Hirschman termed voice or exit not only within state institutions but also within all groups and associations that claim to represent them in debates over citizenship policies (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1970).

Ascertaining whether people have real opportunities for voice is essential both when policies subject a category of citizens to special treatment that most in the category do not desire, as in the case of rules allowing denaturalizations with limited due process, and when policies deny sought-after special treatment to a category of citizens, as when religious groups seek to use controlled substances in religious ceremonies. If all persons affected have had genuine chances to be heard in state policy making and adjudication processes and within groups seeking special treatment, then complaints about differentiated treatment lose some (not all) weight. Most people, however, justly feel demeaned by legal citizenship rules when they have had no practical options in their groups or in state processes to shape policies to which they object.

Consequently, the first step in assessing the political-representation dimension of lived citizenships is to discern whether different categories of citizens have, in law and in practice, opportunities for voice in pertinent decision-making processes. Formal rights to voice are vital but not determinative (Wilson Reference Wilson2019, 96–171). Analysts have shown how systems of representation can pose almost insuperable barriers to effective voice, especially for minority and poorer voters (Castiglione and Pollak Reference Castiglione and Pollak2018). Citizens of color, for example, can rightly claim not to experience equal political esteem when legislatures chosen through electoral systems that overrepresent white voters then adopt policies reinforcing those voters’ advantages. It is equally important to ask whether all within a group whose leaders seek special legal treatment have had opportunities to influence the positions advanced by those who claim to speak for them. Privileged members of advocacy organizations and cultural communities too often suppress the concerns of “minorities within minorities” (Okin Reference Okin, Eisenberg and Spinner-Halev2004; Strolovitch Reference Strolovitch2007).

Because people can shape their personal choices more readily than collective ones, exit options sometimes do more than voice to enable people to have the lived citizenships they seek. It therefore matters whether citizens have practical opportunities to exit from a city, state, or nation when those in power ignore their voices. It sometimes matters more whether dissenters have means to exit from churches, ethnic communities, or employers that advance civic demands, such as exemptions from antidiscrimination laws, they oppose (Kukathas Reference Kukathas2003). Exit options are, however, often not what dissidents desire. Many want more responsiveness from their communities to their concerns. In any case, the costs of exit are often too high to make a formal option meaningful (Shachar Reference Shachar2001; Weinstock Reference Weinstock, Eisenberg and Spinner-Halev2004). That is why empirical assessments of the realities of opportunities for both voice and exit are needed to judge whether a civic order’s formal rights of representation are advancing experiences of equal lived citizenships.

(ii). Resources and Redistribution. Though political rights help secure all rights, most people’s everyday lived citizenships are most shaped by their access to material resources and opportunities. Assessments of whether people have “appropriate” resources form part of deep disputes over whether capitalist inequities simply cannot be overcome, so that collectivist systems of worker or social ownership are needed, or whether people can benefit enough from redistributive policies to make citizenships in capitalist societies equitable, or whether aid policies intended to combat inequalities only generate “moral hazards,” incentivizing unproductive conduct that limits resources for all (Forbath Reference Forbath1999; Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2020). Views on many civil rights, including economic liberties and social rights to financial aid, education, health, and more often rest on contrasting economic ideologies.

Precisely because civic orders as well as other policies structure access to material resources needed for respectable standing, governments committed to goals of equitable lived citizenships must accept responsibility for empirically assessing the economic consequences of alternative policies, at both the micro and the macro levels. At the micro level, for example, they have a duty to determine whether or not a person’s hearing disability impedes completing a state employment exam in the standard time and whether special accommodations might make job opportunities more equal. At the macro level, they must monitor how near or far the employment, income, health, and wealth conditions of different categories of citizens are to a society’s medians and whether inequalities are heightening (e.g., Piketty Reference Piketty2017). Such data must inform debates over whether material inequalities are so great as to contribute to unduly unequal lived citizenships. Large-n studies must be joined with qualitative analyses to determine whether people experience resource policies as enabling material well-being and civic respectability.

As economies change, moreover, constant attention must be paid to empirical evidence of how both particular provisions and the civic order as a whole are affecting people’s economic experiences. When they spur escalating material inequalities, the case for new civic rights and institutions strengthens. These might include forms of special political representation for poorer citizens, as class-conscious theorists urge, in order to insure that inequalities are redressed (e.g., Green Reference Green2016; McCormick Reference McCormick2011).

(iii). Recognition and Special Treatment. The subjective perceptions of people that they are being denied equal civic recognition and esteem by the officials and institutions of their society may be hardest to assess. Public policies receive wildly different interpretations, and benefits to some can be seen as harms to others. Still, perceptions of unequal recognition are usually greatest on the part of groups whom a state’s coercively enforced policies have harmed, whether intentionally or through indifference and neglect. Public acknowledgment of those harms and adoption of policies that are directed at alleviating them may help all such citizens to feel they are now being seen and treated appropriately.

Consequently, hard choices on citizenship laws should often be resolved by prioritizing those whom states have hindered, purposefully or not. Some argue that persons acquire claims to citizenship itself because they deserve voice in policies that a state coercively enforces against them (Honohan Reference Honohan and Bauböck2018, 148–150; Smith Reference Smith2015, 219–246). Similarly, it is appropriate to consider whether categories of citizens whom governments have subjected to coercively enforced policies have claims to distinctive forms of recognition that may include targeted aid and special political rights. Long-subjected indigenous tribes, for example, have claims to broad rights of self-governance and to control of land and other resources vital to their tribal existences. Racial and ethnic minorities, women, and LGBTQ+ citizens long denied access to many forms of public employment, education, and political office have claims to special opportunities for publicly funded positions for which they qualify. When governments have financed public transportation and communication systems designed only for citizens with conventional abilities, disabled citizens have a claim to suitable modifications, such as making mass transit vehicles wheelchair accessible and providing Braille instructions, so that the lived citizenships of all are more equal.

Claims for special treatment of those disadvantaged by past and present state policies should not automatically trump all other considerations. Targeted measures may prove insufficient or unnecessary to address inequities. They may impose costs that outweigh their benefits. Governing officials should also not ignore those who face difficulties not directly traceable to state policies, such as, perhaps, workers laid off because their skills have become obsolete. Yet given the long history of inegalitarian American policies, the priorities of decision makers should reflect awareness that measures tailored to aid those thus harmed may be required to make all feel they are truly recognized as equal citizens.

Lessons of Civic Orders: Uniformity or Differentiation?

The first lesson implied by this framework for mapping and assessing “civic orders” is that it is not fruitful to argue over whether the rights and duties of citizenship should be, in general, uniform or not. Once we discern the 29 provisions of the American civic order listed in Tables 1 – 3, the often bitter debate over whether categories of citizens should ever have differentiated rights and responsibilities becomes starkly one-sided. Differentiation is, always has been, and always will be the rule, not the exception. Indeed, unless two individuals share the same mode of acquiring U.S. citizenship; the same dual-citizenship eligibility; the same local residency; the same biological sex, gender identity, and sexuality; the same age group; the same disabilities; the same race and ethnicity; the same religion; the same criminal and military records; the same employments; and the same stock ownerships, their legal citizenships vary in ways that greatly affect their lived citizenships.

The intense disputes over some variations create the impression that departures from civic uniformity are always suspect. Yet many differentiations, including many age distinctions, disability and veteran benefits, and some religious exemptions, have long been incorporated into citizenship laws with little controversy. Although much American political discourse has professed to reject variations in legal citizenship, as in the slogan of “Equal Rights to All and Special Privileges to None” advanced by Populists, Jacksonians, and Jeffersonians, those rejections have addressed only a few sets of rights and privilege, while their proponents have happily accepted many others (Beeby Reference Beeby2001, 161–162).

The serious questions for citizenship theorists, activists, and policy makers concern what forms of legal differentiation help to contribute to more equal experiences of lived citizenship for all and what forms instead make lived citizenships more inequitable, often by contributing to unjust forms of discrimination, subordination, and exploitation. Civic differentiations should not be presumed illegitimate. Instead, differentiated provisions must be studied to see whether evidence shows them to be forms of “targeted universalism”: measures that help meet “the needs of both dominant and marginalized groups,” with “particular attention” to the often-unequal lived citizenships of the marginalized (Powell Reference Powell2012, 24). Those examinations must be recurrent, because changing material conditions and values may diminish some forms of marginalization, such as discrimination against Catholics in America, while distinctions long taken for granted may be increasingly seen as invidious, as has been true of sexuality and disability.

Intersectionality and Methodological Pluralism

These imperatives raise the issue of how best to discern the effects of legal civic orders on experiences of lived citizenship. Mapping legal rights is necessary but not sufficient. Multimethod empirical studies of how citizenship laws affect civic experiences are vital. Impacts on employment, income and wealth, housing, education, and health, as well as electoral participation and office holding, require large-n data analyses. Because experiences of lived citizenship cannot be deemed equitable if people do not see them as such, people’s perceptions must also be explored. Surveys can help, but in-depth interviews and observational research are also needed. It is otherwise hard to discover how and why many of those whom the law provides with formal citizenship rights still feel they suffer denials of the esteem and material opportunities accorded to civic equals. It is also hard to see the many kinds of meaningful, sometimes counterbalancing civic agency that persons can exercise even absent legal citizenship status (Alejandro Reference Alejandro1993; Isin and Nielsen Reference Isin and Nielson2013).

It is vital, moreover, to examine both the effect of particular laws and the synergistic effects of a civic order taken as a whole. The key insight of intersectional scholarship, that persons’ experiences reflect their positioning within multiple social structures, including those of class, race, gender, and sexuality, must guide investigations on how civic orders, which reflect and affect all these evolving structures, shape experiences of lived citizenship (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989). Intersectional analyses can, in turn, gain force by documenting the inegalitarian effect of interacting provisions of civic orders. As examples, jurisdictional citizenship rules that enable corporations to limit taxes by venue shopping can add to the tax burdens of low-paid workers and limit public resources for social rights. Denaturalizations for minor errors can place less educated Muslim young men in special jeopardy. Religious accommodations for medical providers may particularly bar poorer trans persons from health services. Once we accept that civic orders inevitably create differentiated categories of citizenship, we must accept that the resulting different experiences of lived citizenships have to be assessed through multiple methods that recognize the many intersectional positions that laws partly create.

Conclusion

Neither attention to legal civic orders nor to persons’ lived experiences of citizenship can alone enable normative theorists, empirical analysts, activists, and policy makers to see how equal citizenship can best be pursued. A framework that maps the complexities of a society’s civic order and uses them to guide empirical and normative assessments of the relationship of that order to lived citizenships is required. If we know better how the laws that structure the acquisition and loss of citizenship, the rights and duties of citizenship, and the interconnections of civic communities affect persons’ access to political representation, material resources, and social recognition, we can better discover what effects both uniform and differentiated civic laws have had and whether different laws might better advance more equitable lived citizenships for all.

Acknowledgments

The author gives profound thanks to Jeffrey Green, Nancy Hirschmann, Desmond King, Anne Norton, Nora Reikosky, Ayelet Shachar, Ian Shapiro, Peter Spiro, Mary Summers, and the editors and reviewers of the APSR for invaluable comments and criticisms of earlier versions of this paper. Benjamin Banker, Qi Haotian, Kate Lindenburg, Nora Reikosky, Chloe Ricks, and Nicholas Vicoli all provided helpful research assistance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

Ethical Standards

The author affirms this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.