Antimicrobial resistance is one of the most serious global health threats of the 21st century. Currently carbapenems, β-lactam antibiotics that target and arrest bacterial cell wall synthesis serve as “last resort” therapeutic agents for multidrug-resistant infections caused by bacteria in the Enterobacterales family (formerly called Enterobacteriaceae).1,Reference Sievert, Ricks and Edwards2 Infections with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE), and particularly carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CPE), increased during the first decade of this century with a coincident increase in patient morbidity and mortality due in part to limited treatment options.3,Reference Patel, Huprikar, Factor, Jenkins and Calfee4 In response, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has categorized CRE as an urgent public health threat and recommends aggressive coordinated action to minimize emergence and spread.1

Various mechanisms of carbapenem-resistance in Enterobacterales have been described; however, resistance mediated by production of carbapenemases (enzymes that hydrolyze and inactivate carbapenem antibiotics) are of particular concern.Reference Queenan and Bush5 Carbapenemase genes are generally found on mobile genetic elements that can increase exponentially in a population through the combination of horizontal gene transfer and clonal expansion.Reference Queenan and Bush5 The most commonly reported carbapenemases in Enterobacterales worldwide are Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC), New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM), oxacillin-hydrolyzing β-lactamase-48 (OXA-48), Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase (VIM), and imipenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase (IMP).1 KPC was first identified in the United States in 1996 and is considered endemic in many areas of the world, including parts of the United States.1,Reference Molton, Tambyah, P Ang, Lin Ling and Fisher6,Reference Yigit, Queenan and Anderson7 NDM and OXA-48 have primarily been associated with health care on the Indian subcontinent and in Europe, respectively.Reference Lascols, Hackel and Marshall8 NDM cases reported in the United States have mostly been identified in patients with either international travel or health care.1,Reference Codjoe and Donkor9 IMP and VIM are predominately identified in Asia with sporadic cases identified in the United States.Reference Nordmann, Naas and Poirel10 The epidemiology of CRE indicates that CPE have spread, which in turn has prompted active surveillance to direct targeted actions to prevent transmission.Reference Schwaber, Lev and Israeli11

CPE are increasingly common causes of healthcare-associated infections and are typically seen in patients with prior healthcare exposure.Reference Tängdén and Giske12-Reference Guh, Bulens and Mu14 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has published tool kits for monitoring and preventing spread of CPE.15 These guidance documents stress the importance of understanding the epidemiology of CRE and CPE locally, regionally, and nationally to develop appropriate prevention strategies. Therefore, systematic surveillance of circulating carbapenem-resistance mechanisms is necessary to track prevalence and coordinate public health response.

In October 2012, Washington State Public Health Laboratories (WAPHL) began prospective, statewide surveillance and carbapenemase testing for CRE isolates. The objectives of this work were (1) to quantify prevalence and assess molecular characteristics of carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp circulating in Washington state, (2) to determine broad sources of carbapenemase acquisition including Washington healthcare facility or foreign healthcare exposure/travel, and (3) to compare Washington CPE surveillance to data from other states to guide prevention efforts. We present patient and microbiological characteristics from 5 years of CRE surveillance in Washington.

Methods

Statewide submission of CRE bacterial isolates

The Washington State Department of Health (DOH) solicited CRE clinical isolates from clinical laboratories across Washington state from October 2012 through December 2017 for submission to WAPHL. The CRE surveillance case definition changed twice during the surveillance period. From October 2012 through December 2013, submission criteria included all genera of Enterobacterales resistant to all third-generation cephalosporins tested and nonsusceptible to 1 or more carbapenems. Criteria for submission from January 2014 through April 2015 were E. coli and Klebsiella spp resistant to all third-generation cephalosporins tested and nonsusceptible to 1 or more carbapenems. Starting May 2015 through December 2017, surveillance criteria were all E. coli, Klebsiella spp, and Enterobacter spp resistant to any carbapenem. Various submission criteria are summarized in Supplementary Table 1 (online). Due to variability in submission criteria, only carbapenem-resistant E. coli and Klebsiella spp were included in this study and CR-Enterobacter isolates were excluded.

Information accompanying isolates included date of collection, specimen source, organism identification, and patient demographic data including gender and age.

Microbiology and molecular testing methods

The identification of all CR-E. coli and CR-Klebsiella isolates received from laboratories was confirmed using traditional biochemicals as previously described.Reference Traub, Raymond and Linehan16 Additionally, isolates underwent confirmatory antibiotic susceptibility testing using Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion and/or Etest methods as described by the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Current, available cephalosporin and carbapenem CLSI break points were used based on year tested.17-22 Any isolates that failed identification or antimicrobial susceptibility confirmatory testing were excluded from the study. Depending on the testing protocol in place at the time of submission to WAPHL, some CR-E. coli and CR-Klebsiella isolates underwent phenotypic assay for carbapenemase production in addition to PCR for carbapenemase genes. The modified Hodge test (MHT) was performed from October 2012 through April 2015, and PCR alone without MHT was performed from May 2015 until September 22, 2017, when testing including both the modified carbapenem inactivation test (mCIM) test and PCR began. The MHT and mCIM were performed as previously described.Reference Pierce, Simner and Lonsway23,Reference Ramana, Rao, Sharada, Kareem, Reddy and Ratna Mani24

The identification of carbapenemase-encoding genes was determined using single-plex laboratory developed traditional polymerase chain reactions (PCR) validated to detect the 5 most common carbapenemase genes: bla KPC, bla NDM, bla OXA-48, bla VIM, and bla IMP. The PCR amplification primer sequences were adapted from previous published reportsReference Nordmann, Naas and Poirel10,Reference Mataseje, Boyd and Willey25,Reference Doyle, Peirano, Lascols, Lloyd, Church and Pitouta26 and are listed in Supplementary Table 2 (online). Genomic DNA was extracted from CR-Klebsiella and CR-E. coli isolates using a rapid-boil method. For each bacterial isolate, a 1-µL loopful of colonies was taken from extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) HardyCHROM (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, CA) or blood agar, suspended in 1× TE buffer, boiled at 100°C for 5 minutes. Extracted DNA was amplified using the HotStarTaq Master Mix Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Reactions were carried out under the following conditions: initial denaturation (94°C for 2 minutes), followed by 30 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 30 seconds), annealing (at specified Tann per Supplementary Table 2 for 15 seconds) and extension (72°C for 1 minute). Amplicons and products were analyzed on electrophoresis gels or the TapeStation 2200 genetic analyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and visualized for appropriate band size compared to positive control strains and control DNA ladder.

Surveillance data analysis

To prevent analysis of duplicate isolates, each unique genus/species/carbapenemase combination was counted only once during the surveillance period for each case patient. Additional isolates from case patients were counted if a different carbapenemase or the same carbapenemase in a different genus or species was identified.

To determine risk factors for carbapenemase infection in Washington state, local DOH staff investigated all carbapenemase-positive case patients. Medical record review was completed for all case patients, and an interview with hospital infection prevention staff and/or interview with the patient or proxy was completed when possible. Summary data collected through these investigations were reported to the state using a standardized case report form and included information such as underlying health conditions, healthcare exposures, and international travel in the prior year. Healthcare exposure questions were developed based on healthcare exposure definitions outlined in previous reports,Reference Guh, Bulens and Mu14,Reference Munoz-Price, Poirel and Bonomo27,Reference Guh, Limbago and Kallen28 and they focused on hospitalizations, admissions to a long-term care facility, surgeries, dialysis, and indwelling medical devices in the year prior to date of collection.

We used an online CDC CRE tracking database to compare the number and nature of carbapenemase case reports in Washington to those in other states.29

Statistical analysis

Statistical summaries were performed using Excel version 16.27 software (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) to describe frequency and proportion of carbapenem-resistant E. coli and Klebsiella spp tested, proportion of carbapenemase-positive isolates of the total number of isolates tested, and proportion of each carbapenemase gene detected in respective genera.

Results

Patient demographics and source of carbapenem-resistant E. coli and Klebsiella spp isolates tested

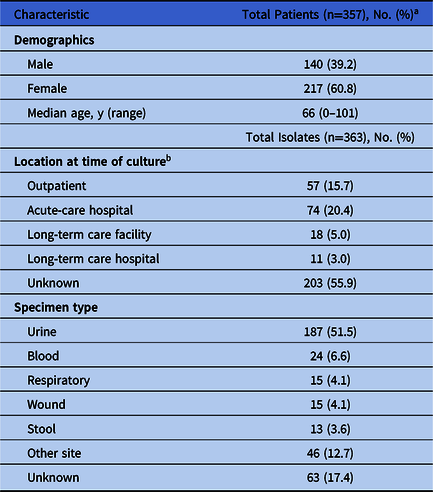

From October 2012 through December 2017, 363 unique CRE isolates from 357 patients were tested at WAPHL. Isolates were submitted by 61 unique clinical laboratories from patients receiving medical care across 21 total counties spanning the geographical area of Washington state. Of these, 239 (66%) isolates were E. coli and 124 (34%) were Klebsiella spp. Patient demographics and source of isolates are summarized in Table 1. Just more than half (51.5%) of the isolates were recovered from urine specimens.

Table 1. Clinical Characteristics and Demographics for Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales (CRE)-Positive Patients

a 6 patients had 2 isolates.

b Patient location was not collected for all isolates without carbapenemase.

The number of carbapenem resistant isolates submitted and tested at WAPHL per year increased steadily from 2012 to 2017, with E. coli remaining the predominant organism throughout (Fig. 1). Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 115) was the primary Klebsiella spp tested, followed by K. oxytoca (n = 8) and K. variicola (n = 1).

Fig. 1. Number of carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp isolates submitted to the Washington State Public Health Laboratories each year from 2012 to 2017. Number of total E. coli and Klebsiella spp isolates tested is shown on the y-axis and the numbers are captured in the table provided below the corresponding year on the x-axis. E. coli and Klebsiella spp. are shown by the black and grey bars respectively.

Carbapenemase genes detected

Of the 363 carbapenem-resistant E. coli and Klebsiella spp isolates tested, 74 isolates (20%) from 70 patients were carbapenemase positive (Fig. 2). These isolates originated in 51 unique healthcare facilities across Washington, most of which (n = 24, 47.1%) were acute-care hospitals (Table 2). Among the Washington isolates, K. pneumoniae were most likely to encode a carbapenemase, with 45 of 115 isolates (39%) testing carbapenemase positive compared to only 28 of 239 E. coli isolates (12%) (Fig. 2). Two-thirds of 45 carbapenemase-positive K. pneumoniae isolates carried the bla KPC gene, and the 28 carbapenemase-positive E. coli isolates were predominately positive for bla NDM (57%) (Fig. 3). Of 8 K. oxytoca isolates, 1 (12%) was positive for the bla KPC gene (Fig. 3) and the single K. variicola isolate submitted was carbapenemase negative. Overall, bla KPC was the most common carbapenemase gene detected (n = 35, 47%), followed by bla NDM (n = 22, 30%), bla OXA-48 (n = 16, 22%), and bla IMP (n = 1, 1%). The bla VIM gene was not detected in any E. coli or Klebsiella spp tested and analyzed during this study. All carbapenemase-positive CR-E. coli and CR-Klebsiella isolates were positive by either MHT or mCIM, depending on the method used at the time, and no isolates positive by MHT or mCIM tested negative for a carbapenemase gene by PCR.

Fig. 2. Portion of carbapenemase-producing, carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates submitted to the Washington State Public Health Laboratories from 2012 to 2017. The number of isolates is shown on the y-axis and bacterial species including E. coli, K. pneumonia, K. oxytoca, and K. variicola on the x-axis. The numbers of carbapenemase-producing and carbapenemase-negative isolates from each species are shown by grey bars and black bars respectively; “n” indicates the total number.

Table 2. Clinical Characteristics and Demographics of Case Patients With Carbapenemase-Positive Escherichia coli or Klebsiella spp

a Exposure included any health care 12 months prior to isolate collection.

b Health care is defined as hospitalization, long-term care admission, surgery, dialysis, indwelling devices. Does not include outpatient care.

c Includes isolates from bone, abdominal fluid, abscess, cerebral spinal fluid, and pleural fluid.

d Included 51 unique healthcare facilities; 24 acute-care hospitals, 2 long-term acute-care hospitals, 9 skilled nursing facilities, and 16 outpatient locations.

Fig. 3. Distribution and number of carbapenemase genes among Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp tested at the Washington State Public Health Laboratories from 2012 to 2017. The different species are shown on the y-axis, and the horizontal bars are sectioned by carbapenemase gene identified. Each gene, including bla KPC (black bars), bla NDM (grey bars), bla IMP (dotted bar), and bla OXA-48 (white bars), are shown for each species if detected. Abbreviations: bla, β-lactamase.

Demographics of carbapenemase-positive case patients and molecular epidemiology of carbapenemase genes

In total, 70 case patients had a carbapenemase-positive E. coli or Klebsiella spp isolate. Four patients had 2 carbapenemase-positive isolates, each with a unique genus-species-carbapenemase combination (Supplementary Table 3 online). Most patients (58%) were between the ages of 18 and 64 years old and were male, and most carbapenemase-positive isolates (45 of 74, 61%) were cultured from urine (Table 2). From 2012 to 2014 and in 2017, bla KPC was the most common carbapenemase gene detected; however other years varied, with bla OXA-48 and bla NDM being the most common detected in 2015 and 2016 respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Molecular epidemiology of carbapenemase genes detected each year from 2012 to 2017. The number of carbapenemase genes is depicted on the y-axis and year on the x-axis; bla KPC (black bars), bla NDM (grey bars), bla OXA-48 (white bars), and bla IMP (dotted bar) are shown. Abbreviations: bla, β-lactamase.

Characteristics associated with carbapenemase positivity and suspected source of carbapenemase acquisition

As determined by epidemiologic investigations, of 70 case patients with carbapenemase-producing E. coli or Klebsiella spp, 42 (60%) had healthcare exposure in Washington, 18 (26%) had international healthcare or travel exposure, and 10 (14%) had only international travel but no health care in the 12 months prior to isolate collection (Table 2). Of the 28 case patients that had international health care or travel, country of exposure was identified for 27 (97%). Most had traveled to India (n = 14) or the surrounding area: Bangladesh (n = 1), Sri Lanka (n = 1), and the United Arab Emirates (n = 1). Other locations of travel were China and Southeast Asia (n = 5), Ghana (n = 1), Ethiopia (n = 1), Cameroon (n = 1), Italy (n = 1), and Russia (n = 1). Washington healthcare exposures were assessed as the likely sources of acquisition of bla KPC, whereas international health care or travel were probable sources of non-bla KPC carbapenemases (Fig. 5). Furthermore, patient data for specific dates and length of stay acquired through epidemiological investigations indicated that patients with international exposure positive for non-bla KPC carbapenemases did not receive overlapping care from any of our submitting facilities.

Fig. 5. Total number and percentage of carbapenemase genes from patients with either exposure to US health care or international travel or health care. (A) Proportion and percentages of carbapenemase genes linked to US healthcare exposure. (B) Proportion and percentages of carbapenemase genes linked to international travel or healthcare exposure: bla KPC (black), bla NDM (grey), bla IMP (dotted), and bla OXA-48 (white). Abbreviations: bla, β-lactamase.

Comparison to other state and national CRE data

Based on publicly available CDC surveillance CRE data (as of December 2017), all 50 states have reported bla KPC.29 Washington is among the 34 states that have reported bla NDM, 27 states that have reported bla OXA-48, and 13 states that have reported bla IMP. Based on these national surveillance data, Washington has the third-highest number of case reports for bla NDM and the second-highest number of case reports for bla OXA-48 in the United States.

Discussion

The CRE are of significant concern to clinicians and public health officials. Carbapenemases in CPE are typically found on plasmids or transposons, which can be shared and therefore spread rapidly among different species of bacteria.Reference Queenan and Bush5,Reference Frieden, Harold Jaffe and Cardo30 These infections have few treatment options, and they are associated with poorer clinical outcomes.Reference Patel, Huprikar, Factor, Jenkins and Calfee4,Reference Patel and Nagel31 Estimating prevalence and surveillance of CRE within an institution, state, and/or region is an important step in understanding the burden and distribution of carbapenem resistance caused by carbapenemases, leading to implementation of appropriate prevention measures.

Prior to 1996, CPE was not reported in the United States, but recent studies have shown that CPE has been reported in all US states.1,29 Our Washington surveillance results align with national data showing that bla KPC is the most prevalent carbapenemase. KPC is considered endemic in some parts of the United States and is so prevalent that the CDC and some states do not track individual case reports.29,Reference Lazarovitch, Amity and Coyle32 A prospective multicenter study of hospitals in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Michigan completed by Duin et alReference Van Duin, Perez and Rudin33 highlighted the endemicity of KPC-producing CPE in these states with primary focus on K. pneumoniae; they reported only a single NDM positive isolate. Furthermore, a large population- and laboratory-based active surveillance study including data from Colorado, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, and Oregon by Guh et alReference Guh, Bulens and Mu14 showed that CP-CRE account for a small subset of infections when compared to the total number of infections caused by Enterobacterales. Across these 7 states, they only identified KPC and no other carbapenemases. Interestingly, NDM-producing CPE outbreaks have been identified in both Colorado and Illinois,Reference van Duin and Doi34 and a previous multistate study characterizing NDM-positive Enterobacterales encompassed only 8 isolates from Massachusetts, California, Illinois, Virginia, and Maryland.Reference Rasheed, Kitchel and Zhu35 Washington state is among the small subset of states that have reported the presence of other carbapenemase types, including IMP. Compared to other antibiotic-resistant pathogens, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) or Clostridium difficile, the CRE incidence is lower.Reference Livorsi, Chorazy and Schweizer36 However, limited treatment options and poor clinical outcomes associated with CRE infections demand interventions to prevent emergence and for controlling further spread of CPE.Reference Livorsi, Chorazy and Schweizer36 The epidemiologic investigations for CPE cases in Washington state suggest that most non-KPC carbapenemases, such as NDM and OXA-48, were potentially acquired outside of the United States via international exposure. These findings support previous published literature that NDM is often associated with travel in highly endemic countries.Reference Van der Bij and Pitout37,Reference Bush38 Furthermore, non–KPC-positive patients who had international exposure did not receive overlapping care from any submitting facilities, indicating that the NDM and/or OXA-48 detected in this group were likely not transmitted within Washington state healthcare facilities. Notably, Washington state began CRE surveillance and performed PCR testing of CR-isolates for 5 carbapenemases earlier than many other states, which may in part explain the larger diversity and higher number of carbapenemase cases found relative to other states. Taken together, these data show that Washington state has a higher number of NDM and OXA-48 carbapenemases than most other states, but it is not clear whether this is due to more widely available detection or to increased prevalence.

During this surveillance period, some patients showed evidence of persistent CPE colonization, based on recurrent positive cultures for the same species/carbapenemase combination on different days. In total, 15 of the 70 carbapenemase-positive patients (21.4%) tested positive more than once with a carbapenemase-positive E. coli or Klebsiella isolate. We documented persistent colonization for longer than 3 months in 7 (47%) of these cases (6 KPC and 1 NDM), with 2 (13%) having recurrent infections multiple times >2 years after first identification (1 KPC and 1 NDM). These data suggest that persistent colonization may occur and that special screening and infection prevention interventions are required to prevent transmission.

Our study has several limitations. CRE surveillance definitions and isolate submission criteria changed between October 2012 and December 2017. Our results did not capture other carbapenem-resistant pathogens that could have potentially harbored carbapenemases, such as other genera of Enterobacterales, Pseudomonas spp, and Acinetobacter spp. From October 2012 through April 2015, antibiotic resistance criteria for isolate submission were more exclusive (Supplementary Table 1 online) and required resistance to all third-generation cephalosporins tested, which may have resulted in nonsubmission of carbapenem-resistant isolates that would have been accepted starting in May 2015. Due to the variability in submission criteria, we only included carbapenem-resistant E. coli and Klebsiella spp in this report as the 2 genera collected throughout the entire surveillance period. The CRE definition has evolved over time in an effort to maximize detection and reporting of carbapenemase genes. Notably, K. variicola has a history of being misidentified by microbiology laboratories, and this could explain why we identified only 1 K. variicola in our isolate cohort.Reference Fontana, Bonura, Lyski and Messer39 Another important factor to consider is that interviews with patient, proxy, and/or infection preventionists were only completed when possible; therefore, epidemiological investigations may have missed some health care and/or travel exposures in our carbapenemase-positive case patients. However, an extensive medical record review was conducted for each case patient, which informed the vast majority of the analysis presented here. Lastly, our surveillance system design only detected infections confirmed by the submitting laboratories; therefore, infections for which cultures were not obtained were missed.

This study highlights the prevalence of carbapenem-resistant E. coli and Klebsiella isolates with the overarching goal to determine the distribution of carbapenem-resistance resulting from the presence of carbapenemase genes circulating in patients in Washington state. CRE and CPE prevalence data are critical components of more comprehensive national CRE and CPE data that ultimately help to elucidate the burden, prevalence, and type of carbapenemase genes and in response provide a framework for potential infection and outbreak response measures.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2020.26

Acknowledgments

We thank the many people who assisted with this project including submitting facilities and laboratory personnel. We would like to thank Maryanne Watkins, Terry DuBravac, and Keri Robinson for their contributions performing laboratory testing.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Washington State Department of Health and National Institute of Health.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.