Dance and opera had a much closer relationship in the seventeenth century than most histories of opera convey. It is well known that for the French dance was a fundamental part of the work, integrated into every act, but even across the rest of Europe audiences almost always watched dancing as part of an evening spent at the opera. What audiences saw varied considerably according to genre, time, and place; even in important operatic centres much remains to be learned about the intersections of opera and dance. Nowhere is it possible to fully perceive how dance functioned across an entire work, but there are a surprising number of surviving choreographies for individual dances, all from either the beginning or the end of the century. Moreover, enough accounts of dancing exist, some of them in libretti, to show that both action dances and dancing based on abstract floor patterns co-existed throughout the period. By the end of the century the technique of dance was expressed via terminology in French – a vocabulary still used in classical ballet – but local traditions helped define national and even regional styles that impacted operatic practices.

Pre-Operatic Practices in Italy

Early court operas absorbed practices from the intermedio tradition, which included dance. In fact, several of the genres of court entertainments, such as ballo, balletto, mascherata, or festa, either allude to or imply dancing in their very names. The particularly well-documented festivities for the wedding of Ferdinando de’ Medici and Christine of Lorraine in Florence in 1589 were far from the only instances of interspersing intermedi between the acts of a play but were probably the most splendid – and exceptional, because most of the music survives.1 The play in question, La pellegrina by Girolamo Bargagli, had six spectacularly staged intermedi, two of them embellished with dancing. The texts were written by several eminent poets, including Giovanni de’ Bardi and Ottavio Rinuccini, and the music was composed primarily by Cristofano Malvezzi and Luca Marenzio, with additional contributions by Bardi, Giulio Caccini, Jacopo Peri, Antonio Archilei, and Emilio de’ Cavalieri, the latter of whom supervised the performance of the music. In the third intermedio, pastoral dances by nymphs and shepherds are interrupted by the arrival of a monster, who is vanquished by four expert dancing masters (one of them performing as Apollo). One eyewitness account reveals the mimetic nature of the movement:

In the meantime, the dancers approached the animal, jumped around this animal with great agility, fought with the same, finally pierced the same, so that it fell to the ground, twisting this way and that, and fell dead with a great clatter, back into the hole out of which it had emerged. Thereafter, the dancers performed yet another dance of joy, [and they] exited from the place [stage] again.2

The sixth intermedio had a much grander and more ceremonial character: its twenty-seven dancers, sixty singers, supernumeraries, and twenty-five instrumentalists brought the evening to a spectacular conclusion in a paean to the newly married couple. Remarkably, Cavalieri’s choreography for the concluding dance of this intermedio survives; set to his own chorus ‘O che nuovo miracolo’, it is transmitted in the ninth partbook of Malvezzi’s 1691 publication of the music, in lengthy instructions accompanied by two diagrams.3

The music alternates sections in duple and triple metre, switching between five-voice chorus, doubled by instruments, and trios for three sopranos (probably representing the three Graces); all of the sections were danced. Whereas ambiguities arise in reconstructing this choreography,4 its general outlines can be discerned: of the twenty-seven dancers, seven (four women and three men) were featured; the floorplan positions the twenty group dancers in an upstage arc, with the soloists either in the centre of the arc or downstage in a smaller arc; much of the choreography alternates figures for the men and for the women, with all seven sometimes dancing simultaneously; the remaining twenty dancers join in toward the end. This dance is based on abstract and symmetrical figures, in distinction to the mimed dancing of the fourth intermedio.

The steps prescribed by Cavalieri (seguito scorso, continenze, capriole, tempi di gagliarda, etc.) are familiar from the large dance treatises by Fabritio Caroso – Il ballarino (Venice, 1581) and Nobiltà di dame (Venice, 1600) – and Cesare Negri, whose Le Gratie d’amore (Milan, 1602) was revised as Nuove inventioni di balli in 1604. Moreover, Negri’s treatise provides two additional choreographies from intermedi, ones performed in Milan during the late sixteenth century. The ‘Brando per otto’, which followed the last act of the eclogue in five acts, Arminia by Giambattista Visconte (Milan, 1599), was attributed to four nymphs and four shepherds who danced across seven musical sections. In Negri’s treatise, one of these is labelled a ‘gagliarda’; others appear to include a pavana, saltarello, and alemana.5

Court Opera in Early Seventeenth-Century Italy

The works we now identify as the earliest operas, starting with La Dafne (Rinuccini, Peri; Florence, 1598), were created by many of the same people who had contributed to intermedi and other musical entertainments, most notably Rinuccini, Bardi, Peri, Caccini, and Cavalieri. These early works incorporated similar dance practices, in which dancing was strongly associated with pastoral characters and featured in choruses, especially, but not exclusively, those that ended the entire opera. Even Cavalieri’s Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo incorporated dancing, notwithstanding its allegorical subject and performance in a church (the Chiesa Nuova in Rome, February 1600). Moreover, in the preface to his published score, Cavalieri even underlines the contributions dances make to this and similar works, noting that they ‘truly enliven these plays, as, in fact, has been judged by all the spectators’.6 Cavalieri distinguishes between dances that are ‘unusual’ (‘fuori dell’uso commune’), such as battles, and ‘formal dance’ (‘ballo formato’), by which he means ones organised around abstract patterns. He recommends that the concluding dance be ‘sung and also played by the same persons who dance, with good occasion, holding the instruments in their hands’.7 This general advice is, however, modified later in the introduction, where instructions given for the strophic chorus, ‘Chiostri altissimi, e stellati’, that concludes the work imply two groups of dancers: mixed couples who perform during the sung portions and four maestri (that is, highly trained male dancers) who dance the ritornelli in a more technically advanced manner, ‘without singing’. For both sections, the description names some of the steps to be performed:

The dancing begins with a riverenza and continenza, and then other slow steps follow, the couples interweaving and passing with dignity. The ritornellos are performed by four people who dance exquisitely with leaps and capers, and without singing And so in all the strophes [of the chorus] always vary the dance, and the four masters who are dancing should vary them, one time doing a gagliard, then a canario, and then a corrente, which go very well with the ritornellos. If the stage is not large enough for four dancers, two at least should be used. The dance should be choreographed by the very best master that can be found.8

As the separate identification of the maestri suggests, the singing chorus and the dancers associated with it were not necessarily the same people; contemporary evidence suggests the co-existence of both singing-dancers and dancing-dancers. Peri’s Euridice, performed in Florence later the same year, also ends with a strophic chorus, labelled a ballo, which shows the same alternation: the entire chorus sings and dances during the strophes, while the ritornelli are ‘danced by two soloists from the chorus’. Both Cavalieri’s and Peri’s concluding complexes end with a choral strophe that must have been danced as well as sung.9

The score to Monteverdi’s Orfeo (Mantua, 1607) refers to one piece as a balletto – the chorus ‘Lasciati i monti’ in Act I. Like several dances from earlier works, this one takes place within a pastoral realm and, structurally, consists of a strophic chorus with an instrumental ritornello; its first verse and ritornello are repeated later in the act, just before ‘Vieni Imeneo’. The other clear dance comes at the end of the opera, where a strophic chorus is followed by a moresca – a dance that some recent commentators have interpreted as a remnant from the ending of the opera found in the libretto, where Orfeo is killed by Bacchantes. At least one other piece seems a likely candidate for dancing – Orfeo’s strophic song, ‘Vi ricorda o boschi ombrosi’ in Act II; both the song and its ritornello feature an alternating hemiola pattern found in other triple-metre Italian dances from the period.

Francesca Caccini’s La liberazione di Ruggiero, dall’isola d’Alcina (Ferdinando Saracinelli, Florence, 1625), called a balletto in its sources, uses dancing by the sorceress Alcina’s female followers as an enhancement to the seductive attractions in Alcina’s enchanted gardens; this is but one instance among many in operatic history of dancing being used as seduction by women of questionable motives. Toward the end of the work, Alcina’s followers join with Ruggiero’s knights to celebrate his liberation; the whole is followed by a horse ballet.10

Opera in Venice

When opera became a public spectacle in Venice in 1637, dance remained one of its components. Ground-breaking work by Irene Alm has allowed us to see how extensive dance was in Venetian opera, and how, as the anonymous librettist for Monteverdi’s Le nozze d’Enea con Lavinia (Venice, 1641) put it, the balli should be ‘derived in some way from the plot’.11 One key figure, dancer and choreographer Giovan Battista Balbi (fl. 1636–1654), was involved from the start, and had already been mentioned in the libretto for the first opera produced there, L’Andromeda (Benedetto Ferrari, Francesco Manelli; 1637). Balbi’s Le nozze di Teti e di Peleo (1639), with music composed by Francesco Cavalli, has a particularly large number of dances – some vocal, some instrumental – across all three of its acts. In one lengthy scene (whose music is extant), ‘Bacco and Sileno praise the virtues of wine, and the choruses [fauns and Bacchantes] dance to their melody.’12 Although subsequent operas by Cavalli and his contemporaries did not approach this degree of sumptuousness, there are indications in more libretti than not that dance was part of the performance: Alm has documented the presence of balli in 297 of the 346 operas performed in Venice up until 1700.13

Whereas the strength of the pastoral tradition meant that nymphs, dryads, shepherds, and fauns remained numerous among the dancing populations, dancers also embodied animals, soldiers, sailors, supernatural beings (demons, spirits, phantoms), comic pages or servants, gardeners, hunters, mad people, and exotic foreigners (Turks, Moors, Spaniards, etc.; see Figure 8.1). In La Calisto (Giovanni Faustini, Cavalli; Venice, 1651), four bears come out of the forest and dance at the end of Act I (foreshadowing the heroine’s transformation into the Great Bear constellation at the end of the opera), and at the end of Act II dancing nymphs with arrows come to the aid of Linfea, who is the object of unwanted sexual attentions by a young satyr and his dancing followers.14

No choreographies survive for any Venetian opera, although occasionally libretti provide tantalising glimpses of the dancers’ movements. As with the intermedi, some of the dance pieces seem abstract, whereas others mime actions: for instance, a battle or an emotional state such as madness. In Mutio Scevola (Nicolò Minato, Cavalli; Venice, 1665) there is a ballo for eight statues who leave their pedestals surrounding a statue of Janus, dance while throwing flames from their mouths, then return to their places. Other stage descriptions call for the dancers to leap and spin, whereas calmer group dances might move in graceful curves, as in the following description from Adriano Morselli’s libretto to Falaride tiranno d’Agrigento (Giovanni Battista Bassini, 1684): ‘The ballo circles through the porticos … . The dance circles around and they exit from the porticos.’15 With the exception of Balbi, choreographers are rarely named in libretti and individual dancers not at all. As for the music, whereas a great deal more dance music survives than has generally been recognised, a significant proportion of it has been lost. Its absence from many of the Venetian opera scores has often been taken to mean that the composer of the vocal music did not write the dances, but Alm argues that the evidence does not support drawing such a categorical conclusion, especially in the face of scores such as Le nozze di Teti e di Peleo (Orazio Persiani, Cavalli; Venice, 1638/9), where the dance music is so interwoven into its surroundings that it must be by Cavalli. She argues further that practices from later periods or from other cities should not be read backwards into mid-seventeenth-century Venice.16

Dances could be set either to instrumental pieces or to vocal ones, most usually choruses. The earlier practice of choruses whose members both sang and danced appears to have given way to greater separation in the functions of the performers; it appears that in Venice, perhaps even as early as Le nozze di Teti e di Peleo, the singers and dancers were different people. Whereas some solo songs or duets may also have been danced, there are clear instances, such as in Cavalli’s Gli amori d’Apollo e di Dafne (Francesco Busenello, Venice, 1640) that a song by Dafne (not danced) alternates with a chorus (danced; Act I scene 4); even when the bodies were different, the association between dancers and a singing chorus remained. The instrumental dances tended to be sectional, in two or three repeatable strains, often with irregular phrase lengths. As the century progressed, the proportion of dances in binary construction increased. Instrumental dances, whatever their form, rarely have generic designations, notwithstanding the few identified as ‘giga’, ‘corrente’, ‘ciaccona’, and the like. More often they are identified by the characters dancing, such as the ‘Ballo d’Eunichi’ in the 1663 Venetian performances from Antonio Cesti’s La Dori (Giovanni Filippo Apolloni; Innsbruck, Hof-Saales, 1657) or the ‘Ballo de Paggi e de Pazzi’ from Carlo Pallavicino’s Diocletiano (Matteo Noris, 1675) – titles suggesting that characterisation was key to the movement style.

As Venetian opera became more and more an art of solo singing, the number of choruses declined. Dancing, however, retained its place inside the opera – largely via instrumentally accompanied scenes at the ends of Acts I and II; these were connected to the plot, however loosely, although the connections grew more tenuous as time went on. Celebratory choruses that included dancing, generally found at the ends of acts or of the entire work, never entirely disappeared.

Opera in France

When Italian opera made intermittent appearances at the French court, under the patronage and encouragement of the Italian-born prime minister, Cardinal Mazarin, and the regent, Anne of Austria (widow of Louis XIII), the operas adhered to mid-century Venetian practices. Balbi drew upon his own experiences in Venice and Florence in choreographing the dances for two of the operas in Paris: in 1645, Francesco Sacrati’s La finta pazza (Giulio Strozzi, Venice, 1641) and in 1647 the creation of Luigi Rossi’s Orfeo at the Palais-Royal, both of which integrated the dances. Balbi later published eighteen designs for La finta pazza (see Figure 7.1). A vivid description of Balbi’s ballets in Paris was written by Olivier Lefèvre d’Ormesson, who attended a performance of La Découverte d’Achille par les Grecs (1645) that contained three ballets: one for monkeys, another for ostriches and dwarves, and one for parrots and Ethiopians.17

In Rossi’s Orfeo, on the other hand, the dances are mostly pastoral; in Act II, for example, a joyous sarabanda danced by twenty-four dryads sets up the shocking reversal when Euridice is bitten by a viper. But by the time Mazarin induced Cavalli to come to Paris in order to celebrate with due pomp the marriage of Louis XIV to Spanish Princess Maria Theresa, the composition of the dance music had been put into the hands of a local – the young Jean-Baptiste Lully – who, by birth, was Italian. Cavalli’s first opera for Paris, the 1660 Xerse (Minato, Venice, 1654), modified one of his Venetian works to suit French tastes: it was still sung in Italian by Italian singers but acquired a prologue honouring the union of the two countries; three acts became five; and six ballets, performed by French dancers, were inserted between the acts. Xerse was fully professional as to both the dancers and the singers, but Ercole amante (Francesco Buti, Paris, 1662), Cavalli’s new commission for the wedding celebrations, still carried vestiges of the ballet de cour, in that members of the royal family and the upper aristocracy danced alongside professional dancing masters in the purely instrumental ballets that ended the prologue and each of the five acts. The king himself, who was an excellent and enthusiastic dancer, performed four roles (the House of France, Pluton, Mars, and the Sun), his bride one (the House of Austria).

Lully absorbed much from Cavalli, but when, in 1672, he opened the Académie Royale de Musique (the Paris Opéra), he chose to integrate dancing inside each of the five acts of every opera, not to relegate it to between them. In his new model, the plot was carried primarily by the singers, but the divertissements were dramatically and thematically connected to their surroundings, and the dancing was interleaved with vocal music.18 This integration has more structural relationship to the comedy-ballets Lully had earlier developed with Molière – in which danced divertissements are part of the plot – than it does to his court ballets, which were constructed around a series of instrumental entrées interspersed with occasional vocal numbers.

During his lifetime Lully had a monopoly on composing opera in France; his creative team included librettist Philippe Quinault (1635–1688) and dancer Pierre Beauchamps (1631–1705), who had served as choreographer for the king’s ballets de cour. Quinault was responsible for structuring the divertissements into the opera, although Lully must have been the one to design their inner workings. Whereas in dialogue scenes Lully’s musical language is restrained, featuring a kind of heightened speech that operates in something akin to real time, divertissements call attention to their own musicality: ‘Chantons, chantons, faisons entendre / Nos chansons jusques dans les cieux’ (‘Let us sing, let us make our songs be heard all the way up to the heavens’), sings Apollon toward the end of Alceste (Quinault, Paris, 1674). Such an invitation allowed for long choruses, strophic songs, and instrumental dances using the full resources of the orchestra; time relaxes and music takes precedence over words. In order to conform to French principles of theatrical verisimilitude, the character types who appear in divertissements are either defined as beings who by their very nature express themselves through dance and song – Arcadian nymphs and shepherds, demons in the Underworld, and so forth – or, if they are ordinary mortals, find themselves in situations, such as wedding celebrations, that make dancing plausible.

Lully’s divertissements serve to expand the world of the opera beyond the main characters to the societies that surround them. One of their functions is to uncover power relationships among individual characters: a hero such as Renaud in Armide (Quinault, Paris, 1686), who is acted upon during divertissements but does not control a single one of them, is revealed as weak. Often the anonymous characters in divertissements represent words or actions that the principals cannot or will not express for themselves: Cadmus arranges a divertissement as a subterfuge for communicating with the captive Hermione; the goddess Cybèle cannot bring herself to admit her love to Atys, so she sends dreams. Such reciprocities between the main characters and the worlds they inhabit are a fundamental feature of the operatic style that Quinault and Lully created together.

The members of the dance troupe, like all their colleagues, were salaried employees of the Académie Royale de Musique. Their numbers are not known for Lully’s era, but in 1704 there were eleven men and ten women. As a practical matter, the functions of singing and dancing were supplied by different people; libretti show that a chorus consisted of group characters, ‘some of whom sing, the others of whom dance’. In other words, every role inside a divertissement is assigned two sets of bodies, although the number of singers and dancers need not be equal. The members of the singing chorus generally stood around the perimeter of the stage, leaving the downstage area free for the solo singers and the dancers, who entered and left the space as appropriate. Quinault’s libretti scrupulously distinguish between male and female roles (e.g., Bergers and Bergères), even though all of the dancers were men until 1681. Even after four women joined the troupe, starting with the ballet Le Triomphe de l’Amour (Isaac de Benserade, Quinault; Saint-Germain-en-Laye, 1681), men still danced some female roles. Their training prepared them to dance in many different styles, and their versatility can be seen in the role assignments shown in libretti; ballet remained a male-dominated art until well into the eighteenth century. Nonetheless, it is clear that the availability of women to dance on the stage changed the character of the divertissements Lully and Quinault wrote into their operas.

The internal structures of Lully’s divertissements are enormously varied, but almost all of them reveal close connections between instrumental and vocal music.19 Often a chorus or an instrumental march brings all the group characters on stage, to be followed by dance-songs, other choruses, and instrumental dances – almost never more than two of the latter in a row. Generic dance types – bourrée, menuet, sarabande, and so on – account for approximately one-third of the dances in any opera. Many more are called ‘entrées’ or ‘airs’ followed by the name of the characters performing them, a musical choice in line with contemporary theorists such as Michel de Pure, who wrote that ‘the first and most essential beauty of an air de ballet is appropriateness – that is, the correct relation that the air must have to the thing represented’.20 Dance pieces are either musically related to adjacent vocal pieces (this accounts for approximately two-thirds of them) or, if they are musically independent, are in close proximity to vocal pieces to which they have dramatic connections. Strophic dance-songs, which can be for solo voice, duet, or chorus, are usually performed in the following order: instrumental dance, the first strophe of the song, a repeat of the instrumental dance, and the second strophe. This means that the audience receives the visual sign before the texted one, since the norm was for the dancers to stop moving during the singing, even when the vocal music was identical to their dance. Choruses could sometimes be danced, if their texts invited movement or if they occurred at the end of a celebratory divertissement, but not solo songs, no matter how danceable the music. Thanks to the integrated structures that Lully and Quinault designed, dance in his operas is presented not as an interruption or as a parenthesis within the action, but as part of a natural continuum that incorporates multiple modes of expression.

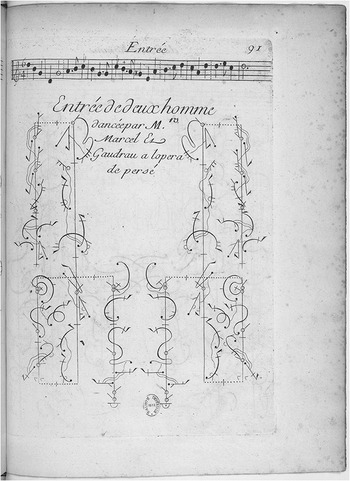

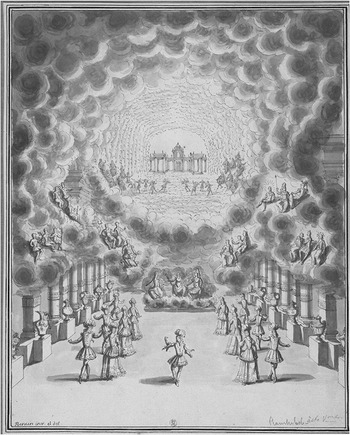

During the 1680s three systems of dance notation came into existence in France.21 The best known among them was developed by Beauchamps but exploited commercially by Raoul Anger Feuillet, author of the 106-page book Chorégraphie and a choreographer in his own right. Although Chorégraphie was not published until 1700, the sophistication of the system and the enormous movement vocabulary it records demonstrate that this style of dance had existed for many years. Moreover, a number of basic stylistic principles – not to mention dance terms – have been handed down over the generations as part of the technique of classical ballet. Beauchamps-Feuillet notation preserves over 350 individual choreographies, among which may be found forty-seven that originated on the stage of the Paris Opéra. Figure 8.2, for example, representing a choreography by Guillaume Pécour for two divinités infernales, can be dated to the revival of Persée in 1710. All of this group post-dates Lully’s lifetime and was choreographed between 1690 and 1713 by Pécour, Beauchamps’s successor as ballet master at the Académie Royale de Musique.22 These choreographies, all of them for one or two dancers, show that the dancing space is oriented around an invisible axis running from front to back through the centre of the stage; when one couple dances, whether same sex or mixed, the two dancers do the same steps and patterns in mirror image. Even in group dances, the patterns are symmetrical (see Figure 8.3).

Figure 8.2 Guillaume Pécour, ‘Entrée for two men danced by Messieurs Marcel and Gaudrau in [Lully’s] Persée’. Michel Gaudrau, Nouveau recüeil de dance de bal et celle de ballet (Paris: Chez le Sieur Gaudrau et Pierre Ribou, [1715]), 91.

Figure 8.3 Jean Berain, a symmetrical grouping of six couples dancing with a soloist. Ink drawing, s.d., c. 1700.

After Lully’s death in 1687, Beauchamps retired, yet the templates they had established for constructing divertissements remained in place, even in the new genre of opera-ballet, which was introduced in 1697 by André Campra’s L’Europe galante. The lean Lullian divertissement only gradually put on more weight through the addition of more instrumental dances and elaborate ariettes. The introduction of contemporary Italian themes onto the stage of the Opéra, which reached its apogee with Campra’s Les Fêtes vénitiennes (1710), expanded the range of dancing roles and allowed the dancing body to become a site for humour, via characters borrowed from the commedia dell’arte. But the dance styles, however comic, remained French; it was not until 1739 when the first Italian dancers made guest appearances at the Opéra that the more athletic Italian dance style began to make serious inroads in Paris.

Operatic Dancing outside of Italy and France

Opera houses outside of Italy and France often borrowed musical and choreographic practices from one or both of the dominant styles, either by importing works, composers, or performers, or through imitation, generally tempered by local practices. Opera in Italian had the greater geographic spread but did not necessarily include Italian dance practices. In fact, France exported dancers and choreographers, and, to a lesser degree, composers of dance music; it was not rare for French-style divertissements to be taken up into diverse types of opera.

German-Speaking Areas

The court operas performed upon occasion before the advent of public opera houses tended to adopt Italian models, although the same German courts might perform ballets de cour and not infrequently employ French dancing masters. Jacques Rodier and his son François choreographed both ballets and operas at the court in Munich; another major French dancer, Jean-Pierre Dubreuil, worked there later. The most sumptuous court opera, however – Cesti’s Il pomo d’oro (Vienna, 1668), commissioned for the wedding of Leopold I and Margherita of Spain – not only had an Italian librettist and Italian composer, it had an Italian choreographer, Santo Ventura; only the stylistically mixed ballet music was local, composed by Johann Heinrich Schmelzer, who between 1665 and 1680 supplied ballet music for most of the theatrical works at the Habsburg court. A ballet connected to the plot ended each of the five acts.

The public opera house that opened in Hamburg in 1678 presented most of its operas in German, whether they were original to Hamburg or translations, although Lully’s Acis et Galatée was performed in French in 1689. (It was performed again in 1695, this time in German; six operas by Agostino Steffani were presented in German translation between 1696 and 1699). Johann Georg Conradi’s Die schöne und getreue Ariadne (1691) adopted both Venetian and French dance practices: the end of the first act unexpectedly ushers ribald scissor-sharpeners onto the stage, whereas Act III features an integrated divertissement for the singing and dancing followers of Bacchus, and the opera ends with a passacaille, both instrumental and vocal, followed by a celebratory chorus. Subsequent operas performed in Hamburg by composers such as Reinhard Keiser, the young Handel, and Telemann reveal a similar mixture of styles that leans towards Italy in the vocal music and France for the overture and the dances, although the stylistic boundaries are porous.

Another measure of the penetration of French dance styles into Germany is the large number of books published there on the topic – no fewer than nine between 1703 and 1717.23 Most of these concentrate on ballroom dancing, but Die neueste Art zur galanten und theatralischen Tantz-Kunst (Frankfurt, 1711), written by the French dancer Louis Bonin, who had moved to Iena after a career at the Paris Opéra, focuses primarily on theatrical styles.

The Low Countries

Operas performed were initially French, riding in part on the wave of émigré Huguenot musicians and printers from France. The first two operas performed in Antwerp, both in 1682, were Lully’s Bellérophon and Proserpine. The company was, however, very small and included only four dancers.24 In The Hague the first opera performed was Lully’s Armide (1701); Atys, Thésée, and Campra’s L’Europe galante were next in line. One of this troupe’s most highly remunerated employees was Pierre de La Montagne, who was imported from Paris. His duties required him to train the dancers, to choreograph, and to dance; the operatic divertissements he oversaw appear to have been performed in full.25

Sweden

Despite a few scattered attempts to import Italian opera, it was not until 1699 – when the Francophile Swedish architect Nicodemus Tessin the Younger promoted the formation of a troupe of French actors to come to Stockholm – that dancing in a semi-operatic context can be documented. At first the troupe, headed by Claude de Rosidor and including twelve actors, four singers, and four dancers, mostly performed comedy-ballets by Molière, plus a few operatic extracts by Lully. In 1701, however, the troupe mounted what has come to be called the Ballet de Narva, a ‘Ballet meslé de chants héroïques’, with a text in French by Charles Louis Sevigny, in honour of King Charles XII’s victory at Narva over the Russians. The vocal music was composed by Anders von Düben the Younger, but the dance pieces and the final chorus were borrowed from the pastorale Le Désespoir de Tircis by Jean Desfontaines, with two additional dances from Lully’s Cadmus et Hermione.26 By 1706 all of the members of Rosidor’s troupe had departed, and opera did not become firmly established in Sweden until well into the eighteenth century.

Spain

The plays written by Lope de Vega for public theatres and, later, by Pedro Calderón de la Barca for the court, were punctuated by music and dance, although the instrumental music rarely survives. Two operas were written in 1660–1661 for the wedding of the Infanta María Teresa with Louis XIV of France: La púrpura de la rosa (text by Calderón, music by Juan Hidalgo, lost) and Celos aun del aire matan (text by Calderón, music by Hidalgo).27 The stage directions in the latter do not explicitly call for dancing, but the loa (prologue) that probably existed at the time could well have incorporated dances.28 Although no other fully sung operas were composed in Spain during the seventeenth century, zarzuelas and other theatrical genres continued to incorporate dances such as jácaras, seguidillas, zarabandas, and chaconas.

England

When English theatres reopened after Charles II returned from exile in France, the musical entertainments put on between the acts of plays included dancing among the songs and acrobatics. Sometimes dances were integrated into the plot – in a scene of celebration, for instance – but most were individual set pieces that had little or no connection with their surroundings. Intermittent visits to London by dancers from the Paris Opéra kept English audiences aware of French styles.29 The earliest operas – for example, John Blow’s Venus and Adonis (c. 1683) and Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas (1689) – followed Lullian models in incorporating dances into the storyline; Dido and Aeneas, short as it is, calls for no fewer than ten. All the dances appear in scenes involving the chorus, such as ‘Fear no danger to ensue’ in Act I, where the libretto says ‘Dance this Cho.’, or the Sailors’ Dance at the start of Act III, which precedes a musically related song by a solo sailor that the chorus joins. The duet in Act I sung by Belinda and the Second Woman, ‘Fear no danger to ensue’, may also have been performed instrumentally, in alternation with the chorus, by simply leaving out the choral parts: not only is it in binary form but it adopts the rhythm of a seventeenth-century French minuet step ![]() .30 The opera closed with a dance by Cupids mourning the death of Dido, although the music for it, as for some of the other dances, does not survive.

.30 The opera closed with a dance by Cupids mourning the death of Dido, although the music for it, as for some of the other dances, does not survive.

Purcell’s four semi-operas (1690–1695), performed publicly by the Theatre Royal company, also drew upon conventions established by Lully in constructing the masques performed between acts; the Frost Scene in King Arthur, for example, uses the same musical figure to evoke shivering as do Lully’s Trembleurs in Isis. On the other hand, some of the dances Purcell inserted into his scores – such as country dances and hornpipes – are purely English. The semi-operas were choreographed by Jo. Priest (Josias or Joseph, who may have been the same person31), but none of his choreographies survive. Handel’s first opera in London, Rinaldo (1710), has a single danced scene, and dancing is found intermittently in other operas; in some later works, such as Alcina (1725), Handel took advantage of the visiting French dancers to build in elaborate ballet sequences.32 That the dancing technique and style were French can be seen by the frequent performances by French and English dancers together, the two almost simultaneous translations into English of Feuillet’s Chorégraphie (by Siris and Weaver, both in 1706), the numerous choreographies in Feuillet notation published in England, and the French dance types that appeared on the English stage (minuets, rigaudons, sarabandes, chaconnes, etc.).33

* * *

By the end of the seventeenth century, French dance practices had penetrated even into Italy, albeit unevenly. Some Venetian operas dating from the 1680s and 1690s incorporate minuets, bourrées (borea), or rigaudons, and composers such as Carlo Francesco Pollarolo sometimes structured divertissements in a French manner, with instrumental dances related to and interwoven with solo songs and choruses.34 However, these tendencies were in the minority; more and more the danced sequences were independent, done as intermezzi after Acts I and II of a three-act opera; by the time Metastasian opera seria arrived, the transformation was complete.35 But even as French and Italian approaches to the relationship between dance and opera grew farther apart, the technical bases of dancing grew closer. The dearth of choreographic sources from the middle of the seventeenth century in both Italy and France makes tracking actual dance practices almost impossible, but it is clear that by the early eighteenth century French and Italian dancing shared a common technique whose lingua franca was French.

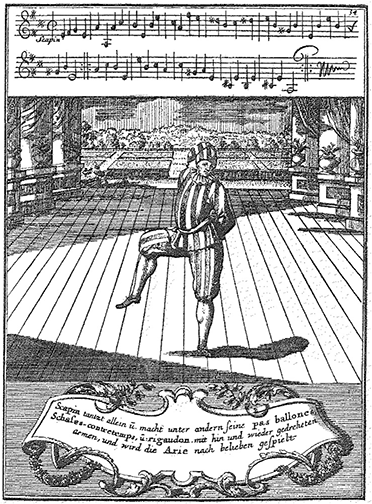

One important testimonial is Gregorio Lambranzi’s Neue und curieuse theatralische Tantz-Schul (Nuremberg, 1716), an illustrated book of theatrical – mostly comic – dances in the Italian style, which uses French names when it mentions steps, as can be seen in Figure 8.4: ‘Scapino dances alone, executing, among other pas, his ballonnés, chassés, contretemps, and [pas de] rigaudon, with his arms twisted from side to side. The air is played at will.’ Yet Lambranzi’s book also underscores differences between the two styles that transcended the steps: Italian athleticism that contrasted with French refinement, the greater latitude given to comic dancing and to mime in Italy, and greater allowance in Italy for choreographic improvisation.36 When Italian dancers first appeared at the Paris Opéra in 1739, they created a sensation; their appearances were but one step in a process of greater hybridisation of the two styles.

Figure 8.4 Gregorio Lambranzi, Neue und curieuse theatralische Tantz-Schul (Nuremberg, 1716), book I, plate 34.