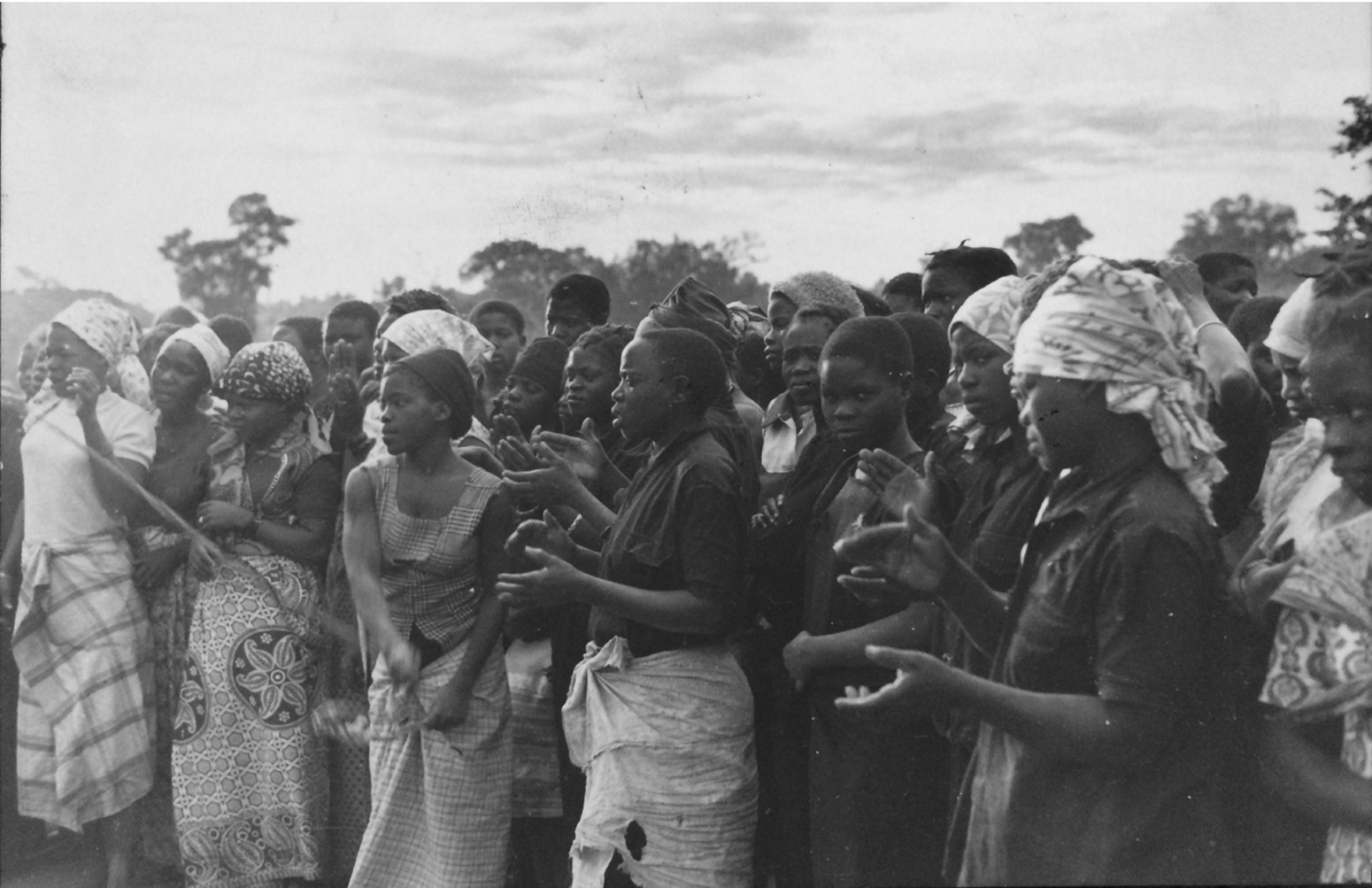

In August 1976, a little more than a year after Mozambique's independence from Portugal, a reporter from the state-run newspaper Notí cias visited the female internment camp of M'sawize in the northern province of Niassa (see Fig. 1).Footnote 1 Housing more than five hundred detainees, M'sawize was one of the twenty-two reeducation camps that the Frelimo regime established in remote areas across the country, immediately upon assuming power in 1974 in a joint transitional government that had mixed Portuguese and Frelimo elements (see Map 1).Footnote 2 The reporter's visit to Niassa was meant to document the progress of women detained for prostitution and to soothe the minds of those who had doubts about the righteousness of the reeducation program in Mozambique. At a time when concerns about human rights abuses were being raised domestically and internationally, the reporter's lengthy article was meant to counter the ‘rumors’ that the camps were sites of macabre punishment.Footnote 3

Fig. 1. Female reeducatees welcoming the Notícias reporter in M'sawize. Their hair was cut short as an attempt to clear off the signs of urban degradation and alienation (wigs and straightened air). August 1976. Courtesy: Arquivo do Jornal Notícias.

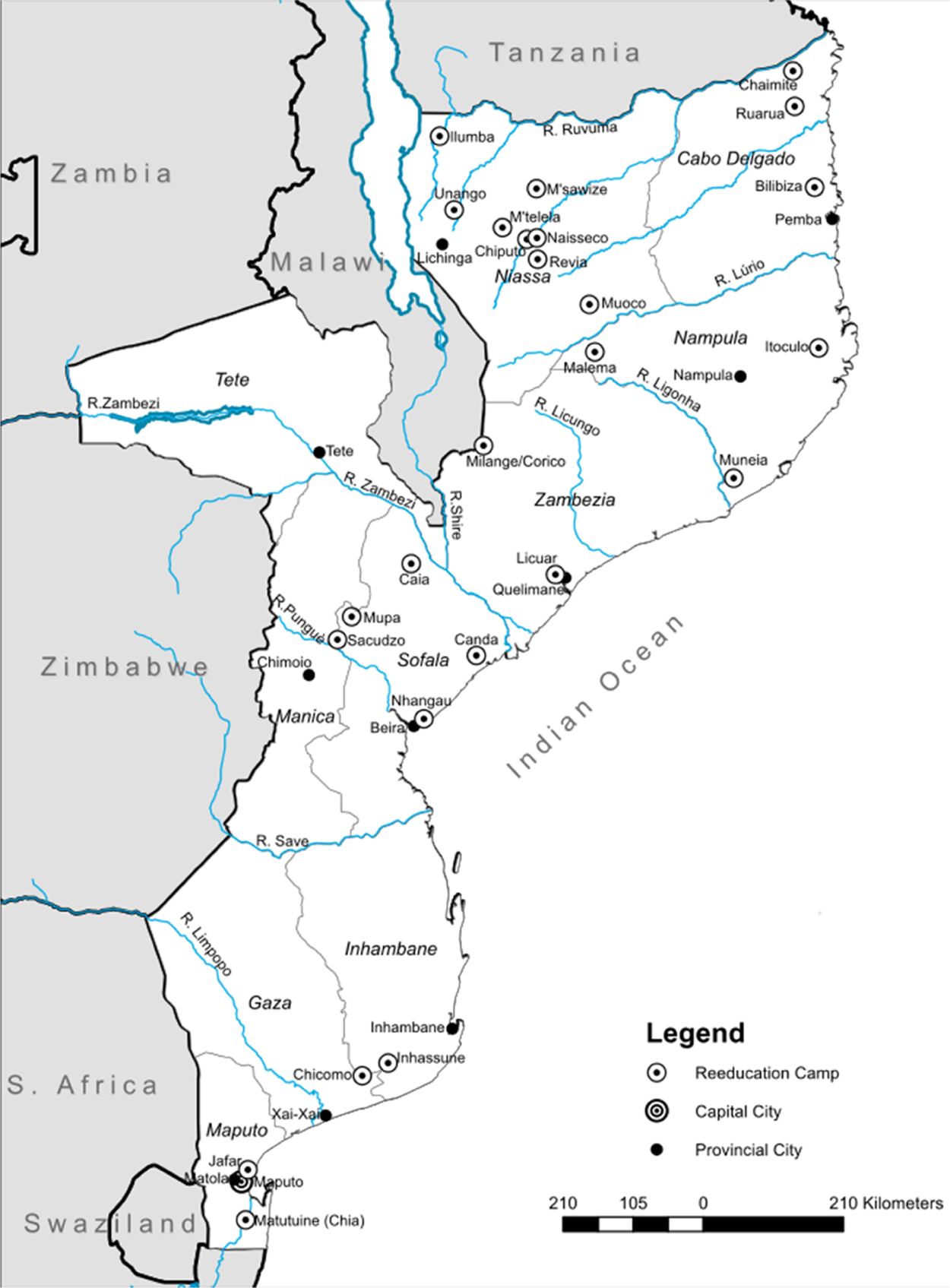

Map 1. Mozambique and the Reeducation Camp complex.

The reporter was impressed with the physical features that distinguished the camp from the thick expanse of forest that surrounded the site. ‘A bamboo stick and thatch mark the entrance’, he wrote. ‘Not far away, the first houses of reasonable dimensions plastered with clay and thatched roof; then a large open field.’ He sketched out the spatial arrangement of the camp, which consisted of two parts. One area was reserved for camp overseers, with housing for warders, a secretariat, a station for radio transmissions, and a refectory. The opposite area contained the detainees’ quarters, a ‘series of sheds arranged length-wise, forming in the background a semi-circle.’ He described the camp's facilities as ‘very rudimentary pole huts, very exposed to cold’. August is the last month of the dry season in southern Africa, and in Niassa's mountainous plateau that means winter. The newsman noted that the huts were ‘built by reeducandas (reeducatees) themselves and by local peasants’.Footnote 4

The reporter observed, with an evident sense of pride, that Mozambique's reeducation camps were deprived of the features commonly associated with modern internment camps. The camps lacked any kind of erected barriers: no fences and no central watch towers. This was a general feature of the reeducation camp complex. In all camps, the number of security personnel was remarkably small in relation to the inmate population, rendering the surveillance regimen very loose indeed. Despite authorities’ attempts to control the movement of people, detainees had considerable leeway inside and outside the camps. This aspect of the reeducation program impressed many people who visited the camps in the 1970s and early 1980s. The visitors were often left with the impression of having visited a typical rural settlement, or an aldeia communal – one of the many communal villages established in the countryside, inspired by Tanzania's ujamaa villagization scheme, as part of Frelimo's strategy for rural development and socialist transformation.Footnote 5 One key difference was that camp detainees wore black uniforms. Another was that some warders were armed with AK-47 rifles. Otherwise, there was little in the camps that resembled a penal institution.

Scholars have assumed that Mozambique's communal villages were part of the biopolitical mechanisms of state surveillance aimed at rendering peasants ‘more legible and, thus, more amenable to state intervention’.Footnote 6 Following Michel Foucault and James Scott, Harry West suggested that ‘in fundamental ways, the communal village worked like Jeremy Bentham's panopticon’.Footnote 7 He argued that ‘the spatial concentration of the village rendered subjects directly susceptible to a monitoring eye – embodied in the Frelimo-appointed village president – that could pass unobstructed through surveillance corridors in a matter of hours’.Footnote 8 If free villagers were subjected to a panopticon, as Harry West (like Christian Geffray before him) claims, what to make, then, of the reporter's observation that the detainees of M'sawize lived in a semi-free regimen in a benevolent place that was supposed to be a detention camp?

What the reporter encountered in M'sawize, I argue, was neither a panoptic institution nor a benevolent carceral regime. The freedoms he observed were the reflection of the austerity – the scarce human and financial resources – that shaped all Frelimo initiatives during Mozambique's fifteen-year socialist experiment. Frelimo authorities wanted the camps to be strict disciplinary institutions. But they were never able to realize their panoptic ambitions of social and spatial legibility, discipline, order, and social transformation because they simply could not afford to do so. The same was true for communal villages. The anatomic sketch of the reeducation camp complex that I draw in this paper illustrates how far apart Frelimo's ambitions were from the material conditions in which the reeducation program was carried out. If we were to accept West's claim, that the communal villages were panoptical, then what the reporter described with awe in M'sawize was an unsighted panopticon.

Building on the archival record of Niassa's Department of Reeducation Services (DPSRN) and interviews with former detainees, this paper illuminates the nature of a carceral regime of mass internment in a context in which the state is materially constrained. Conditions of austerity, argues Laura Bear, create new forms of relationships and engagements between the state, its agents, and society, which are based on altered expectations of performance. One of the main outcomes of austerity is the expectation that those at the bottom of the socio-political and economic hierarchies must do more with fewer resources.Footnote 9 Without material and human resources to run the reeducation program, state officials compelled detainees to build their own detention facilities, to grow their own food, to carry out political education on their own, and, in many ways, to watch over their own carceral regimen. This sense of self-surveillance was not induced by the ever-present monitoring eye endowed with modern, biopolitical technology. Rather, it ensued from the remoteness of the camps and the state's inability to support the reeducation program. Consequently, the reeducation program in Mozambique was a do-it-yourself undertaking that produced a penal regime that was not only distinct from internment camps elsewhere but was also contrary to Frelimo's technocratic moralism and panoptic ambitions.

THE REEDUCATION CAMP COMPLEX

On paper, Frelimo established the camps to ‘mentally decolonize’ and reform ‘wayward’ members of urban society and putative enemies of the socialist revolution. The party leadership envisioned the camps as pedagogical institutions where reeducatees would be transformed into ‘new men’ and ‘new women’ through corrective labor, political education, moral rehabilitation, and cultural enlightenment.Footnote 10 Although some camps interned political prisoners (so-called reactionaries or counter-revolutionaries), the overwhelming majority of detainees were arrested in police roundups for alleged anti-social behavior: prostitution, vagrancy, alcoholism, idleness, and all sorts of petty crimes. The ruling party was convinced that these social ills were obstacles to the modern and morally upstanding social order they envisioned. In this regard, leaders of Mozambique's socialist experiment were not different from other radical reformers in independent Africa for whom moral comportment, decency in dressing styles, temperance, and asceticism in one's personal conduct were key components for building political constituencies, composing civil societies, and upholding a respectable citizenry.Footnote 11 However, as Jocelyn Alexander and Gary Kynoch once observed, Frelimo ‘stands out’ in the continent ‘for the ideological fervor of its early years of rule’.Footnote 12 Mozambique's reeducation camps are a unique case in postcolonial Africa. Despite the relatively modest size of their inmate population – estimated at ten thousand in 1980 – the camps are comparable only with internment camps elsewhere across the communist world, particularly China's Laogai (reeducation-through-labor camps), after whose model they were conceived.Footnote 13

A month before the reporter's visit to M'sawize, President Samora Machel instructed his top cabinet officers during a meeting of the Council of Ministers ‘to give further attention’ to the reeducation program. He stated that the camps should be organized in categories, and reeducatees should be classified and interned according to their offenses. According to President Machel's commandment, there should be specific camps for drug addicts, for prostitutes, for drunkards, for vagrants, for the undisciplined, for thieves, and so on. ‘Our general concern’, the President said, ‘is to transform the old man into the new man, to transform society. Now, all we need is to find the adequate means to achieve this goal’.Footnote 14 To succeed in transforming ‘old men’ into ‘new men’, camp overseers were to be diligent knowledge gatherers, observing the behavior of each detainee and recording their improvement.Footnote 15 What Machel was calling for was a disciplinary institution akin to a modern, well-functioning pedagogical penitentiary. The Chinese Laogai functioned exactly in the same way that Machel wanted the camps to operate in Mozambique. He was likely to have seen them during his visits to China or heard about them from Chinese military instructors in Frelimo bases during the liberation struggle.Footnote 16

Initially, the Ministry of the Interior (hereafter MINT) – the state organ in charge of the reeducation program – attempted to concentrate detainees according to criminal categories. For example, in Niassa, the camps of M'sawize and Ilumba were reserved for ‘prostitutes’. Naisseco, also in Niassa, was opened for ‘individuals considered drug addicts’.Footnote 17 Chiputo and M'telela (in Niassa) and Chaimite (Cabo Delgado) were established for Frelimo's dissidents. However, this organizational scheme did not hold, and chaos rapidly descended into the reeducation camp complex. The camp of Sacudzu in Sofala province held more than 1,000 detainees, among them street children, non-convicted thieves, undocumented civilians who failed to produce ID cards during police roundups, as well as sacked civil servants (including teachers, ‘undisciplined’ soldiers, and police officers).Footnote 18 In Ruarua, common criminal offenders shared barracks with Frelimo's guerrillas who had deserted during the liberation war. The Chicomo camp in Gaza province contained a miscellaneous detainee population of 750.Footnote 19 Even M'telela, a camp destined for prominent political prisoners with no more than 130 inmates, received individuals detained for common law offenses. In general, the inmate population at each camp was a wide mixture of people from all over the country detained for all sorts of offenses.

With few personnel available to run the reeducation program, Frelimo vested power to detain and distribute the detainees throughout the camp complex in low-ranking officers at the ground level. These rank and file officers often dispatched suspects to camps without trial and without consulting authorities senior to them in the hierarchy. The lack of a centralized, bureaucratic body within MINT to coordinate the program from the outset created a muddled situation that continued until the end of the socialist experiment. The creation in 1976 of the Direc ção Nacional dos Serviços de Reeducaçã o (National Directorate of Reeducation Services, DNSR) – almost two years after the first camps were established – did little to remedy the situation. The DNSR and its provincial sub-divisions (the DPSRs) were understaffed and largely on the sidelines when it came to deciding where detainees should go.Footnote 20 Given that anybody in the party-state – from the highest-ranking officer to the lowest agent – could condemn anyone to reeducation without reporting to MINT and without producing any kind of documentation, there simply was no way to coordinate the process. In the end, detainees were dispatched to a designated province, and the local DPSR decided where to send them. Since most people had not been formally sentenced and therefore had no written records of their offenses, they were quite randomly distributed in the camps without any objective criteria. Proper interrogation was something that security and DPSR officers had no time for, much less qualification. Even when, in 1980, a more capable officer named José Castiano Zumbire was appointed to head the DNSR, the camps continued to apply no order in the distribution of detainees and no criteria for organizing their classification files.Footnote 21

Although MINT had jurisdiction over the reeducation program, its functions often overlapped with those of the Ministry of Defense and the secret services (Servi ço Nacional de Segurança do Estado, SNASP). It is unclear how decisions to transport detainees to the camps were taken, but each of these institutions operated an eclectic network of military planes, trucks, and buses to carry detainees to the far reaches of the country. Private and public buses were occasionally employed to transport people to the camps. To prevent detainees from having a sense of their geographical position, transportation was often done under cover of night. Not only were detainees uninformed about their offenses, they were also kept in the dark as to their destiny. While most detainees from southern Mozambique, particularly from Maputo, tended to be sent as far away from the capital as possible, people from central and northern Mozambique tended to be distributed locally.

Upon arrival, detainees were dressed in black uniforms. Each person received two pairs of khaki pants, two long- or short-sleeve shirts, a cap, and a pair of canvas boots. The black uniforms seem to have been used by the colonial security forces, most probably for recruits in training. It is possible that MINT found stocks of them in storage and repurposed them for reeducatees. No other color could have been better suited to dress the fallen urbanites sent to the countryside to be purified of their moral sins. Among other things, the black uniform symbolized the state of suspension of citizenship in which detainees were placed (as a reeducatee, one was stripped of all civil rights). At the same time, the uniform made it easy to exert control upon inmates. This was perhaps the only palpable attempt at giving the camps a sense of uniformity and rendering detainees legible. Peasant populations living near the camps were instructed to be vigilant and inform authorities whenever they saw people dressed in black, wandering about without armed guards. The uniform also gave the regimen of camp life the military semblance that Frelimo authorities wanted to see.Footnote 22

However, camp authorities found it difficult to keep all detainees in uniforms (see Fig. 2). The shortage in consumer goods that characterized the Mozambican economy made clothing a luxury, especially in rural areas. When the stock of uniforms ran out in the first two years of the reeducation program, they were simply not replenished. By 1978, in most camps detainees wore whatever they could find. Only on special occasions, such as a visit by a state official to the camp, did authorities demand that detainees wear their black uniforms. On such occasions, authorities made sure that those detainees with better or well-kept uniforms sat in the front row and the more ragged ones took the back row. In the end, uniformity in the camps was a matter of performance for those higher up the state hierarchy to see. Rather than diligent reformers, austerity compelled camp authorities to become managers of the appearance of uniformity.

Fig. 2. Detainees in a meeting at M'sawize. Some still wear the black uniform or what remained of it. 1976. Courtesy: Arquivo da Revista Tempo.

It also became problematic for the government to dress detainees in the extremely impoverished countryside where local populations still lived largely naked or half-naked. Most of my interviewees recalled the shocking encounters with nearly naked peasants in the villages near their camps, and the envy with which they were often met because of their ‘good looks’ in black fatigues. In Niassa and Cabo Delgado, for example, detainees were known as Mkunya Woripa, or ‘white blacks’. As former detainee Ché Mafuane told me, ‘mkunya woripa means that the person is black but at the same time he is white because he was dressed.’Footnote 23 The label white does not stand for race here, but rather for social status. For the Macua-speaking people in the remote corners of northern Mozambique, the detainees were somewhat privileged because they were dressed and ‘looked good’ in their black garments. On the one hand, this is a clear indication of the level of scarcity and neglect in which local populations lived. On the other, it highlights the cultural and social gap between the rural people of the northern provinces where most camps were established and the detainees who were mostly urban people. That these urbanites – who appeared privileged in the eyes of the rural populations – had to be fed and dressed by the state must have caused a great deal of confusion.

THE SPATIAL ANATOMY AND THE FUNCTIONING OF REEDUCATION CAMPS

The location of the camps, often in the middle of remote forests, was a key feature of Mozambique's mass internment regime. All the camps were established and run after the image of Frelimo camps during the liberation struggle. With very few exceptions, detainees had to build the camps’ infrastructures themselves. They collected the reeds and wooden poles from nearby forests to erect their huts. In Niassa and Cabo Delgado, the huts were then plastered with mud to fill in the open sides as local villagers would have done. But this labor-intensive task took longer to complete. In the two female camps, it seems to have never been actually completed until the camps were closed in the early 1980s. In southern and central Mozambique, the huts were simply built with reeds. Such hastily and unskillfully built huts hardly protected the detainees from nature's elements (cold in the winter nights, snake bites on hot days, and other life-threatening hazards).Footnote 24

Detainees slept on bare, sandy ground. Those who were skilled enough built wooden bedframes. Although the frames were rougher than the floor, at least the detainees avoided the bites of worms, insects, or snakes. In Niassa the great nightmare was the cold. Even in male camps, where walls were plastered, the mud often dissolved with rain and then dried hard and fell off. Since detainees were not compelled to repair their lodgings – left to their own devices as they often were – few people had the will and strength to do the painstaking work of re-plastering the huts. The permanent struggle to find food in the hunger-stricken camps left little room for such work. Consequently, most lodgings were unprotected on the sides (see Fig. 3). Malarial mosquitoes and tsetse flies (responsible for sleeping sickness or trypanosomiasis) found easy ways into the huts and plenty of blood on which to feast.

Fig. 3. Dormitories for female detainees and their children in M'sawize. Note the unprotected walls, which left detainees exposed to cold and nature's other elements. August 1976. Courtesy: Arquivo do Jornal Notícias

The arrangement of camp lodgings was in accordance with Frelimo's high-modernist ideal of how rural settlements should look in socialist Mozambique. Geometrically aligned, rectangular or square-shaped houses replaced the traditional round huts. The aldeias comunais or communal villages were arranged after the Tanzanian ujamaa villages, with straight lines and a large central square reserved for the revolutionary activities of the people.Footnote 25 Reeducation camps followed the same layout, with rectangular huts aligned around an open square area known as the rassemblement. Footnote 26 Like a village's square, the rassemblement was the center of the camp's collective life. Meetings, roll calls, parades, cultural performances, and public punishment took place here. However, where scholars see biopolitical mechanisms of power in the orthogonal shape of Frelimo's rural settlements (from which the arrangement of reeducation camps derived its form), I see Christian missionary architectural and aesthetic ideals.Footnote 27 Like their Protestant missionary instructors, Frelimo revolutionaries saw the non-rectilinear shape of African dwellings – the ‘circular kraal of huts’ as Swiss-Presbyterian missionary Henri Junod once described them – as physical expressions of spiritual and moral damnation and backwardness.Footnote 28 Enlightenment, self-awareness, moral regeneration, and salvation were strictly related to the orderliness and modern shape of square houses and regular lines.Footnote 29 As primary locations for moral purification of ‘anti-socials’, reeducation camps had to be organized according to this orderly form, not so much for legibility or surveillance considerations. The orthogonal shape of the camp was to express human conquest of nature according to scientific methods (an important component of reeducation). Circles were primitive, while squares were modern and rational.

As the aerial photograph of Chiputo illustrates (Fig. 4), the camp had no erected barriers, and many unguarded paths led freely to the working fields and into the forest. As most of my interviewees told me, warders had little concern with keeping watch in the camp and were often interested in hunting ventures or playing games among themselves.Footnote 30 The small number of warders and camp overseers compared to the size of the inmate population gave the impression that detainees lived as semi-free peasants. But this shortage of personnel was often the cause of long-lasting headaches for camp authorities. In his monthly reports in 1977, André Trabuco, the head of the DPSRN, lamented that the number of detainees in most camps in Niassa, particularly M'sawize, Ilumba, and Naisseco, was too high, while camp wardens were few.Footnote 31

Fig. 4. Aerial view of Chiputo. Note the river at the upper corner, the orthogonal shape of the lodgings, the square rassemblement in the middle of the camp, the absence of fences or a watchtower, and the various unpatrolled paths leading into the bush. Source: Tempo, 1979.

According to MINT directives, each camp was supposed to have five responsá veis (camp overseers), each with a deputy in charge of specific tasks.Footnote 32 These include a chief of the camp (the highest position in the camp hierarchy); a military camp commander; a political commissar (who oversaw political education and ideological indoctrination); a responsá vel for agricultural production; and a responsá vel for cultural activities. The camps were also meant to have a secretariat with at least one or two typists to produce the required monthly reports.Footnote 33 Generally, the chief of the camp and his deputy were police officers on the MINT payroll, as were the typists. The rest of the responsá veis and warders were former Frelimo guerrillas and veterans of the liberation struggle who had had very little academic instruction. The number of warders for each camp was never specified. But it was a consensus – even among top members of the central government – that the camps were alarmingly short of guards and qualified overseers. For example, in July 1976, the Council of Ministers proposed the training of at least one hundred professional camp overseers. This number was indicated as an initial, urgent necessity, but in the long run the camps would need more cadres.Footnote 34 During the First National Seminar on Reeducation held in Maputo in November 1976, MINT proposed a two- to three-month training program for camp overseers. The training package was to include political education, sociology, psychology, administration and book-keeping, mathematics, geography, and constitutional law. The program was to be supplemented with talks by high-ranking party officers and guided visits to productive units. Camp overseers were to be versed in farming techniques (including the husbandry of small animals), production planning, techniques of storage and conservation of food, notions of hygiene and first aid, and sports and cultural activities.Footnote 35

However, between intentions and actions there was a very wide gap. Austerity often had the final word, and no training program for camp overseers was actually carried out. With priorities defined elsewhere, no new professional camp supervisors were recruited. Frelimo ran short of cadres to run the massive bureaucracy left in a shambles by the fleeing Portuguese.Footnote 36 With illiteracy well over 90 per cent at the time of independence, the few educated people had to be employed in the most important positions in the government.Footnote 37 This situation was even more critical in the field of security. After the rebellion of conservative settlers on 7 September 1974 – which Frelimo saw as a coup attempt against their incoming government – and the violent riots of 21 October, the capital city needed extensive security.Footnote 38 The fear of an invasion by apartheid South Africa was very real, especially after South Africa's failed but bloody invasion of Angola.Footnote 39 All of these developments led Frelimo to concentrate most of its guerrilla troops in Lourenço Marques and on the southern border with South Africa. In addition, the ransacking and destruction of property undertaken by angry settlers on their exit also increased the demand for security personnel. Factories and economic enterprises had to be protected to avoid further sabotage. The nationalized clinics and schools also needed security. The departure in June 1975 of the last company of Portuguese troops that had helped Frelimo secure the transition made the security situation more critical. The start of the war with Rhodesia in 1976 squeezed the army even more. As Rhodesia's aggression evolved into a civil war led by Renamo in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, the war effort consumed almost all the newly recruited cadres.Footnote 40

There were few human resources left for the reeducation camps. In M'sawize, the chief commander Silência David and her deputy, Judite Florêncio, commanded a platoon of seventeen female guards. This small group was tasked with guarding and re-educating about five hundred inmates. This was the case in almost all camps, where a handful of soldiers guarded hundreds of detainees (see Fig. 5). In the Chicomo camp in Gaza province, commander Jaime Rebich had only fifteen soldiers under his command to guard 750 inmates.Footnote 41 Yet, it was not only guards that were in very short supply. The camps also ran very short on responsá veis. In Niassa, only one camp (Chiputo) had filled the five required positions. In the rest of the camps, overseers had to combine two or more positions, often serving as commanders, political commissars, and responsá veis for production.Footnote 42 Whereas the political leadership in the capital dreamed of specialized and professional reeducators, austerity forced camp authorities to improvise. This not only meant that people had to combine various responsibilities, but also that the very hierarchical structure of the camp was erratic.

Fig. 5. Detainees and a warder posing for a photograph in Unango. This photo was taken during the construction of one the camp's barracks. The detainees wear fodder sacks during work to avoid damaging their uniforms – the only clothes they had. The fact that only one warder posed for the photo indicates that there were in fact very few armed warders in the camp. Undated. Courtesy: Arquivo da Revista Tempo.

In many camps, to alleviate the shortage of guards, the overseers appointed detainees to serve as auxiliaries of patrol units. These detainee-guards were pejoratively called Gatos Vermelhos or red cats by their fellow reeducatees.Footnote 43 Other fortunate detainees were appointed to positions as camp administration assistants, teachers, and heads of working platoons.Footnote 44 Therefore, the environment that the Notí cias newsman found so reassuring in M'sawize – with detainees moving in and out of the camp at will – was a reflection of the shortages that shaped and conditioned the organic functioning of Mozambique's reeducation camps, not the magnanimous nature of Frelimo and its government.

However, this does not mean that detainees were under no kind of control. There were other forms of authority to keep the internees within the vicinities of the camps and to prevent escape attempts. The semi-free women that the Notí cias reporter saw along the road linking M'sawize with the nearby village could only travel in that open stretch of Mavago district. The remote location of the camps, to which detainees were transported in the dark, managed to keep them in line. Like most camps in Niassa, Cabo Delgado, Nampula, and Sofala provinces, M'sawize was established in an unmarked forest within the perimeter of the country's largest hunting reserve (Reserva de Caç a do Niassa). The reserve is well known for its man-eating lions and other wild animals.Footnote 45 The camp was some three hours’ walking distance from the nearest village. Walking to the provincial city of Lichinga generally took two to three days. The area had been one of Frelimo's zonas libertadas during the armed struggle, and a military base (Base Central) was maintained hundreds of miles away from the camp. Local communities were often instructed to report to authorities if detainees showed up in their villages.

Many detainees attempted to escape, and some successfully navigated the wild forests and met the freedom they longed for. Generally, the leading escapees were locals who were somewhat familiar with the area. With their fluency in local vernaculars, they could convince villagers to let them go or even alleviate their thirst and hunger along the perilous journey.Footnote 46 But these were exceptional cases. Most detainees did not dare brave the unknown wilderness, for they had no sense of geography and could not speak local languages. The dangers of the forest and the fear of predators often kept detainees in line. In 1976, the administrator of the district of Majune in Niassa informed the DPSRN that on 17 June, eight detainees fled from Naisseco. One of them, João Manhiça, was ‘eaten by a lion and we do not know about the other seven’.Footnote 47 Camp overseers publicized these chilling cases among detainees to prevent further attempts. Sometimes they forced detainees to bury the incomplete and disfigured remains of their devoured companions to stir more fear of the bush.Footnote 48

‘Full lighting and the eye of a supervisor capture better than darkness, which ultimately protected. Visibility is a trap.’ This is how Michel Foucault described the necessary elements in the working of a panoptic institution.Footnote 49 In Mozambique's reeducation camps, the features of a modern penal institution were upside down. This was a blind panopticon that relied on the remote location of the camps, their wild surroundings, and the terrifying dark of the bush night to keep its subjects in line. The roaring of lions, the growling fights of hyenas, and the singing of owls in the bush night was something that few urbanites would dare confront. The camps’ geographical location was largely enough of an obstacle to curb escapes. Therefore, the range of control in the camp did not rest on the ‘monitoring eye’ of the representatives of the state, nor did it lie on the ‘architectural apparatus’ of the camp with its square-shaped huts and the wide open rassemblement. It did not even rely on armed guards. Rather, it rested on the remoteness of the camps’ locations and the state of ignorance about the geographic location of the camp in which detainees were kept. This was why it was crucial that detainees not be informed about their destiny when they were transported. This was why, inside the camps, geographical maps were kept out of sight. In most cases, they were simply forbidden, even among wardens. As one former detainee in Sacudzo recalled, even lectures on Mozambique's geography were delivered without a map.Footnote 50 Here was another layer of the combined effect of austerity and a fragile carceral regime. Hiding, concealing, and darkness: these were the techniques of surveillance at work in Mozambique's reeducation camps. In the context of extreme austerity, the dangers of the wilderness did the work of surveillance.

WORK AND THE CAMPS’ DAILY ROUTINE

Despite several attempts to produce a centrally-coordinated program for the camps, MINT was never able to pass any regulations with detailed rules on how the camps ought to operate on a daily basis. The ministry was short of capable people to elaborate such rules, and the administrative capacity of the ministry was overstretched, given its ample responsibilities. Consequently, camp supervisors had to come up with their own plans on how to keep the detainees busy. Although a tentative program was introduced later in 1980, when José Zumbire was appointed director for the DNSR, the program still left much of the daily camp routine up to supervisors to decide.Footnote 51 The consensus was that detainees had to work in the fields (machambas), which was supposed to be the source of their food. But unlike penal labor camps elsewhere, where productivity and outputs were often prioritized over other activities, in Mozambique the camps had no economic relevance whatsoever.Footnote 52 There were no production quotas and no defined number of hectares for the fields. The produce from machambas was entirely destined for the inmates’ subsistence – and even here they often fell very short. Not only did the camps lack appropriate implements for agriculture (hoes and axes were the only tools available), but they also had no qualified experts in this field. Therefore, the camps were not self-sufficient. They depended almost entirely on rations from respective DPSRs, which often failed to arrive. Hunger was a permanent condition in the camps. As M'sawize chief commander told the Notí cias visitor, food shortage was the main problem in the camp. ‘We go very hungry here’, she said. ‘Rations hardly reach us. Trucks break down in the rough roads and the food rots and never reaches us here. Many people have anemia. Even now, we only have rations for just one meal in the barn. In addition, the food quality is very poor. Usually we only have beans and maize flour.’Footnote 53

Decrepit infrastructures, rough roads, and shortage of spare parts to keep the few vehicles running meant that camps were isolated for months without rations. Although austerity meant that the entire country faced chronic shortages in food and other basic consumer goods, the remote locations of the camps amplified the crisis. In his report to MINT in May 1976, Francisco Taibo noted that the Naisseco camp ‘is full of malnourished and weak people due to insufficient food’.Footnote 54 Nevertheless, every weekday, detainees were marched in working brigades to the fields, where they grew a few rain-dependent crops that provided the camps’ staple food: corn, manioc, and beans. Small vegetable gardens, which could only be worked on the banks of nearby rivers, were often left to individual initiative. Although in some camps detainees collected timber and produced charcoal, subsistence agriculture was the most serious work in which they were engaged. With no established production quotas, the work regime was relatively mild.

Despite the hardship of farming, detainees were subjected to very little regimentation in reeducation camps. The daily routine in most camps began very early in the morning. ‘Dawn at 4:30 in the morning. Cleaning and breakfast. Then farm. Lunch. Farm again.’ This is how Silência David summarized the daily program of M'sawize as she guided the Notí cias visitor around the camp. ‘In the evening, they eat again’, she continued, ‘however, we do not always have enough food, so sometimes nobody eats at night’.Footnote 55 As in Frelimo's former training camps, the day often started with a whistle, at which sound detainees had to form a line in the rassemblement. The chief commander called the roll and gave the instructions of the day. Organized as brigades of twenty-five to forty people, some groups would work the machamba, others would cut and collect wood, and still others would fetch drinking and cooking water from nearby rivers. Others would build the huts and, in the case of M'sawize, continue working on the opening of the road linking the camp with the nearby village (to allow trucks to deliver rations and bring more detainees).

After the roll call, detainees had a cup of sweet tea (if there was sugar) and a piece of manioc or cornmeal porridge for breakfast. They then joined their working platoons and marched to the fields (see Fig. 6). Other work consisted of felling trees for local construction, firewood, and the production of charcoal, which was then sold in the local markets. In some camps, such as M'telela and Chiputo, there were groups of artisans who were excused from the hard labor of tilling the land. These artisans produced woodwork (such as benches, doors, and bedframes) and carried out minor carpentry and masonry maintenance work inside the camp. Other artisans produced utensils such as baskets and mats. In camps such as M'telela and Chiputo, some of these utensils were sold in the local markets. As with charcoal production, artisanal products were only destined for the market. Yet this often depended on the enthusiasm and organizational skill of the responsá vel for production (who might also be a detainee), as well as the support of camp overseers who sold the products and used the money to buy food.Footnote 56

Fig. 6. Detainees at work in Inhassune, 1976. Courtesy: Arquivo do Jornal Notícias.

After work, detainees returned to the camp for lunch. A team of selected detainees prepared the food. These teams seem to have been rotated daily or weekly, but detainees renowned for being good cooks often held their positions permanently. Cooking was the most sought-after job in the camp because it allowed detainees to be closer to the source of food and guaranteed more generous portions compared to the meager ones that the majority received.Footnote 57 The staple food was cornmeal pap or chima (in other places in Africa it is known as ugali, sadza, or uswa), and beans. Generally, the food was poorly cooked and unseasoned. The beans – which grow everywhere in Niassa – were only prepared with water, salt, and cooking oil (sometimes it was only water and salt, because oil was often unavailable). For urbanites used to a more refined diet, the roughness of the camps’ rations was trying. As Carlos Fumo recalled of Ruarua, ‘we practically lived like savages, we had no food.’Footnote 58 Occasionally, on good days, game meat was served. But this only happened in certain camps near hunting reserves such as M'sawize and Sacudzo. (In Sacudzo, detainees were also served dried fish, as the camp was located along the main corridor of the dried fish trade between Beira and Zimbabwe).Footnote 59 Skilled and resolute detainees often supplemented their meager meals with a piece of fresh fish from nearby rivers. However, given the lack of fishing hooks and nets, catching fish in the camps took great skill and patience. For those with access to vegetable gardens, the unpalatable taste of chima and beans could be improved by the addition of some green leaves.

There was no order to eating time. As soon as their rusty iron dishes were filled, the reeducatees sat wherever they found appropriate in the vast open camp in the company of close inmates or friends (see Fig. 7). In his Kafka-esque novel Campo de Tr â nsito, Mozambican fiction writer and historian João Paulo Borges Coelho captured the eating time in the reeducation camp with satirical yet very informative detail.Footnote 60 Most detainees were modern urbanites who had assimilated the Portuguese colonial notion that cutlery was a symbol of civilization. For most urban southerners, eating with at least a fork or a spoon was the norm, whereas eating by hand was tantamount to backwardness. In the camps, detainees had to learn how to eat by hand, for cutlery was a luxury that only few – often senior detainees – could afford. Like other metal tools (such as knives), forks and spoons were markers of hierarchy inside the camp. Those who obstinately maintained their ‘civilized’ ways of eating used bark or hardened leaves in place of spoons.Footnote 61

Fig. 7. Detainees sharing a meal inside their hut in Unango. Note that one detainee (front right) has a spoon, while others eat with their hands. In some camps, cutlery was a symbol of status. Undated. Courtesy: Arquivo do Jornal Notícias.

Camp overseers ate the same unpalatable food, but theirs was often prepared in separate, smaller pots by relatively better-skilled detainees acting as cooks. At times, they ate in the open, like their captives. At others, they concealed themselves in a less visible spot which detainees were not allowed to approach.Footnote 62 As much as some camp overseers attempted to keep a kind of hierarchical and statutory distance from detainees, the camp offered few options. The differentiation was in the uniforms, the firearms that warders bore, and the undisputed reality that some were captors and others were captives. The camps were so resource-poor that overseers had to go to certain lengths to distinguish themselves from the captives.

In most camps, where farming was only done in the morning, lunch marked the end of daily work for most detainees. They spent the remainder of the day very much on their own. With their hungry bellies appeased (at least for the time being), most detainees spent the afternoons chatting or daydreaming under the cool shade of a tree during the hot summers, or warming up in the sun in the open rassemblement during the chilly dry season. Some detainees spent the free time patching up their ragged uniforms or sewing their worn shoes. Others, the most industrious, tended their small vegetable gardens or fixed their lodgings, which needed permanent repair, given their rudimentary features. Except for the female camps of Ilumba and M'sawize-1, where political education seemed to have been mandatory from the outset, in most camps it was optional (at least until the late 1970s). Therefore, those thirsty for knowledge spent the two hours after lunch attending the political commissar's lectures. Those allowed to hunt braved the forest with a couple of guards on their heels. The less sober found a shady spot to smoke hemp or to gulp cajulima, a locally distilled and highly intoxicating brandy. In many cases, affluent detainees sneaked to the nearby villages for alcohol or to alleviate the urge for a smoke, even at the risk of being caught and punished. However, punishment for smoking hemp or drinking only happened in cases where a mean guard decided to enforce a camp rule that was often overlooked, particularly if camp warders were themselves frequent visitors of the village for the same reason – and this was the case in most camps.Footnote 63

The most creative detainees joined the folklore groups knows as Grupo Cultural Polivalente or Multipurpose Cultural Group. These were highly selective groups, and membership was a free pass to the elite class of detainees excused from the heaviest labor. These groups were responsible for cultural production and entertainment of all sorts, including plays, choirs, dancing, and poetry. They spent most of the day rehearsing the numbers to be presented on Saturday and Sunday afternoons, or during one of the many revolutionary holidays on the calendar. Occasionally they rehearsed to perform for the reception of an important visitor.Footnote 64

There was no strict time to return to the camp in the afternoon. Hunger led everyone to the kitchen line for supper as the falling sun cast its last reddish rays from above the trees surrounding the camp. The meal was invariably the same one eaten at lunch. Sunset marked the end of the day. With no electricity and no lights, at night the dense darkness of the camp was often dotted with sparks of fire where detainees gathered for a last chat, trying to warm up before bedtime during the cold months. Smaller lights could be seen shining inside the lodgings of camp overseers, the only privileged camp dwellers to have a candle or a paraffin lamp – some of the few luxuries that differentiated detainees from their captors. If there was a permanent ‘monitoring eye’ in the camp, surely it went totally blind at night.

THE ‘FAÇADE’ OF POLITICAL EDUCATION

Despite the elegant rhetoric around political and ideological (Marxist-Leninist) education, which Frelimo leaders frequently claimed was at the heart of the rehabilitation of Mozambique's anti-social elements, there was little in the camps’ educational program worthy of such designation. In Niassa, for example, DPRSN officers saw the education program as a façade, or at most a meaningless activity.Footnote 65 The camps were deprived of basic didactic materials, classrooms, and qualified cadres to carry out the program. Political commissars were responsible for the educational program. However, not all camps had a political commissar. Camp overseers were often forced to take up this task, combining the responsibilities of camp commander and political commissar. Yet, very few overseers had the qualifications necessary to instruct detainees in politics or any other academic matters. In many reports, DPSRN directors lamented the shortage of cadres to run the camps in Niassa and the lack of a clear program for reeducation other than compulsory manual labor and the ‘pointless’ sessions of political education.

MINT made the poor state of political education the main subject of its First National Seminar on Reeducation, which was held in in Maputo in November 1976. The seminar concluded that while manual labor was undoubtedly a crucial component of reeducation, a meaningful political program had to be created, one informed by scientific socialism. ‘For example’, it was stated, ‘production has to be studied’ and detainees had to learn that it was ‘through production that humanity evolved’; they had to learn the ‘role of the surplus and the emergence of class division in society’. They also had to study the ‘current revolutionary process in Mozambique’ and the pursuit of a ‘classless society’.Footnote 66 Learning the history of Mozambique's colonial domination, the rise of Frelimo, and the struggle for liberation were key steps in the transformation of detainees into awakened, conscious new women and new men. It was determined that the ‘implementation of a meaningful political program implied the organization of reeducatees according to a military structure’. Camps ought to have a monthly plan that dictated all activities. Each Saturday afternoon, camp overseers were to meet and meticulously study the execution of the plan and establish new programs. The daily program mandated two hours for political study.

Political education was supposed to include lectures, the production of a camp journal, and the collective study of newspapers. There were detailed instructions on how the two hours of political education had to be spent. One hour was to be dedicated to lectures; half an hour for debate and clarification of doubts; and the remaining half hour for commentaries on daily news and such issues as ‘the definition of the enemy, the behavior and erroneous ideas among reeducatees, exposition of new initiatives’, and so on. For the program to be successful, a designated group of detainees had to listen to the 12:30 p.m. news from a battery-powered radio set, then explain it to all detainees in the general parade. Austerity meant that only one radio set could be allocated to each camp for this purpose. The size of the radio set also meant that only a few detainees could listen to the news. In the absence of loudspeakers, the few listeners were to serve as amplifiers and broadcast the news to others. In addition, camps were instructed to introduce gymnastics, sports, and cultural activities. Professional training was to be implemented in crafts such as carpentry, mechanics, and arts. In their capacity as chief political instructors, political commissars had to create a group of aides among exemplary detainees, who were to prepare – under their supervision – the materials for the lectures. Each class was supposed to have twenty to forty students. Political commissars were to inform detainees that participation in these activities was a ‘decisive step towards their freedom’.Footnote 67

Austerity limited the party's ability to realize its reformist ambitions. These detailed instructions were part of a wider culture of wishful governmentality that characterized Frelimo's socialist regime, in which policies were decided upon and implemented first. Planning and calculations, which were often ambitious and unrealistic, came later.Footnote 68 In the end, the high-minded instructions on reeducation remained a dead letter. Little if anything changed in the educational program inside the camps. DPSRN officers continued to be greatly concerned about the level of education of many camp overseers in Niassa. In April 1977 – six months after the Seminar on Reeducation recommended special training for camp supervisors – the new director of the DPSRN, André Trabuco, noted that the ‘political and technical capabilities’ of Niassa's camp officers ‘are minute’.Footnote 69 He sadly informed his superiors that in Ilumba, for example, ‘the various programs are being implemented with much difficulty due to lack of personnel in quantity and quality to materialize the instructions.’ The main deficiencies were noted in literacy and political education. ‘The camp lacks personnel capable of understanding the instructions through political documents, Tempo magazine and newspapers, and interpreting them’, he wrote.Footnote 70

In fact, the only didactic materials that camp overseers had to work with were newspapers (especially the weekly magazine Tempo and the daily Notí cias). Speeches by Frelimo authorities (President Machel's in particular) were the primary and often the only guiding tools for political education. Often, these ‘precious’ materials arrived in the camps several months after they had been published. School books were in short supply in the country and none could be sent to camps. Oriented by people with ‘minute’ education, it is not difficult to imagine the theatrical nature of lectures on political and ideological education that reeducatees were compelled to attend every day after returning from the fields. Seated under the shade of a tree, as was often the case because there were no huts to serve as classrooms, detainees listened as their political instructors read aloud a section of a speech by the president or a piece of news. A discussion of the content of a months-old news article would then follow. If the commissar happened to be versed in Frelimo's socialist maxims or had a certain knowledge of the history of the armed struggle, she or he would throw in some ready-made slogans about the virtues of collective labor, the class struggle, the heroic saga of the liberation war, or the actions of global imperialism and internal enemies seeking to undermine the revolution. Instructors kept no records as to who attended the lectures and made no assessment of inmates’ pedagogical progress. With no training for instructors and no didactic materials, political education amounted to nothing more than propaganda, ‘mobilization’, and moral exhortation. This is how Silência David, the chief of the women's camp in M'sawize, explained her political work among putative prostitutes:

Political education is part of our working methods. At first, if we said ‘Viva Frelimo’, nobody responded. Nobody understood why they were brought here, why they had to suffer this much and endure these life conditions. To explain what the lives of these women represented in the colonial society, to explain the kind of society we want to build in Mozambique, to explain why they are in this isolated place, a political explanation was necessary.Footnote 71

Like her colleagues in other camps, Silência David measured the success of her political work by the unison shouts of Viva Frelimo with hundreds of arms in raised fists, as well as the military discipline that detainees seemed to show in the roll calls and parades. For most camp authorities, all that reeducation aimed for was that detainees should understand why they had to endure isolation and suffering in such remote places. Obedience to camp commandments and military orderliness in parades was often the only measure of detainees’ submission to the reeducation program. Ana Maria, who was detained in a dance club in Maputo at the age of eighteen and spent two years in M'sawize, told me sarcastically: ‘I learned to be a soldier. I did not need any reeducation, but I was re-educated, I did not dance anymore, for example.’Footnote 72Another former detainee, who was seventeen when he was sent to Sacudzo, said to me in anger: ‘I don't think I was re-educated. Quite the opposite, I cultivated hatred and resentment.’Footnote 73

Four years after the first seminar on reeducation, the government recognized that little had been done to implement an effective educational program in the camps. During the Second Seminar, which was also held in Maputo in January 1980, the new interior minister, Mariano Matsinhe, urged participants to find solutions to improve the situation by listing the same tasks defined in 1976. Nevertheless, he lauded the ‘successes achieved’, and claimed that they ‘attest to the righteousness of Frelimo's political line and the measures taken by the government for the reeducation of thousands of vagrants and delinquents who swarmed the urban areas of the country’.Footnote 74 The minister's statement reveals not only the inability of the state to accept its shortcomings, but also the blind belief in the idea of reeducation. Other aspects of everyday life in the camp reflected the contradictions produced by a carceral regime functioning under extreme conditions of scarcity and the gap between high-minded ideals and reality.

SOCIAL LIFE INSIDE THE CAMPS

Apart from the harsh labor conditions, poor diet, and the pretense of reform, life in Mozambique's reeducation camps was also governed by unwritten rules about temperance and abstinence. Detainees were expected to cultivate austere moral habits, to stay away from inebriating drinks and drugs, and to remain chaste. For the architects of the reeducation program, life in the camps had to be close to monastic. However, much of the social life inside the camps revolved around drinking, hemp smoking, and sex. The dormant panopticon of Mozambique's penal colonies could not tame these idiosyncrasies of nature. Under conditions of extreme want, both detainees and warders created new forms of sociability inside and outside the camps. Drugs, alcohol, sex, and all kinds of illicit trades subverted the monastic ambitions of Frelimo leaders. As Ana Maria told me in our interview, ‘If you did not smoke you had to learn to smoke. If you did not drink, there you had to drink. Otherwise you would go crazy and die alone’. And she added: ‘many people began smoking in the camps’.Footnote 75

Throughout Mozambique, rural populations had always planted hemp in their gardens. The distillation of cajulima from sugar cane or other fruit-based spirits was also a centuries-old tradition.Footnote 76 The presence of detainees near rural villages provided a market – incipient as it was – for the intoxicating and inebriating produce that was never wanting in most rural homesteads. Generally, detainees exchanged with villagers the few but very precious goods that they received as part of their rations – mainly soap and clothing – for alcohol and hemp. As Felizardo Chaguala recalled, in Sacudzo, a small group of detainees often combined to go to the village during or immediately after work in the fields, entrusted with goods collected from several detainees, such as bars of soap, pieces of cloth, and occasionally money. Although the drinks were consumed in the villages, since bottles were harder to conceal, the group would bring the hemp back to the camp and distribute it to their comrades.Footnote 77 Although smoking and drinking were forbidden, and one could be flogged if caught red-handed, camp warders often ignored this unwritten rule. Some warders and camp commanders had a taste for cajulima and hemp as well. Sometimes detainees and warders ventured together to purchase hemp and cajulima in nearby villages. It was common for warders to send detainees to procure the goods for them, or for detainees to bribe warders with hemp to avoid punishment.Footnote 78 As Ana Maria and Ché Mafuinane pointed out in our conversation about M'sawize and Chaimite, these schemes between detainees and warders put all camp dwellers on the same plane. ‘We did not sit at the same table with the camp commander’, Ana Maria told me, ‘but I can say that we smoked with them’.Footnote 79 In fact, some camp warders were not simple smokers. They were also engaged in the hemp trade inside and outside the camps. As former SNASP operative Silva Santana told me, many soldiers bought the hemp from rural villagers and transported it to urban areas in Soviet-made airplanes, which were rarely inspected at airports. Austerity could also provide camp authorities and security officers connected to the reeducation program with an opportunity for accumulation. Silva Santana was himself a prosperous hemp trader in the 1970s and 1980s. As he boasted to me, ‘I built a very nice house with the sale of hemp’.Footnote 80

This was one of the many contradictions of the reeducation program. For people detained for smoking, drinking, or ‘sexual corruption’, the reality of life inside the camps was a bitter irony. For those who never smoked and did not drink, the camps initiated them. Although not all detainees led unrestrained lives, few – captives and captors alike – lived up to the monastic aspirations that political authorities envisioned in the high seat of power in the capital. President Machel was incensed when he first visited the camps of Niassa in 1979 and Cabo Delgado in 1981. In Naisseco (Niassa) and Ruarua (Cabo Delgado), the President recognized that, among many other things, drunkenness and recklessness were the order of the day. Reeducatees and reeducators all lived in the most ‘disgusting’ of conditions and unruliness. Although the supreme leader attributed the chaos in those two camps to an internal enemy deliberately seeking to undermine a revolutionary program, he acknowledged that reeducation was ripe with contradictions that reproduced the very social ills that the program was meant to eliminate.Footnote 81

The President's findings could not be truer in the two female camps of Ilumba and M'sawize. Here there was little that the female camp supervisors could do to prevent the frequent visits of soldiers and paramedics stationed in the military garrisons several miles away from the camps. The lists produced by the DPSRN in 1976 of pregnant detainees in the two camps illustrate the extent to which the situation was out of control. In May 1976, forty-six children were born in M'sawize, and thirty-one in Ilumba. Although some women were already pregnant when they arrived in the camps, most must have gotten pregnant while they were there.Footnote 82 The archival record is largely silent about how detainees got pregnant. But one case was recorded in August 1977 because of the shocking castigation that the offenders met. The case involved an employee of Niassa's reeducation services contracted to build a brick house in M'sawize. The unnamed fellow was caught having sex with an unnamed reeducatee. According to the report, it was the fourth time that the couple were caught, and this time they were punished. The camp commander forced the offending couple to repeat the act in the rassemblement in front of everyone in broad daylight. Although the couple refused, they were forced to push a barrel of oil round the rassemblement completely naked, as all the detainees sang a revolutionary anthem and clapped.Footnote 83 Although this was a case of a civilian who could be subjected to such chastisement, most soldiers who visited the camps were powerful commanders, and women in the camps recalled how they compelled detainees and also female warders to have sex with them. As Ana Maria told me about M'sawize, female warders were also involved with soldiers. Pregnant warders were immediately removed from the camp and replaced.Footnote 84

But this was not simply a story of men forcing women into unwanted affairs. As one paramedic put it in an application letter to Niassa's Governor Aurélio Manave, ‘love happened’.Footnote 85 In September 1976, a twenty-four-year-old nurse named António Muianga wrote to Governor Manave to ask for his permission to marry Filomena Matangue, a reeducatee at Ilumba. The two had met in Base Central Ngungunhana, a military garrison near the camp, where António had been temporarily stationed. In Niassa and Cabo Delgado, these military garrisons were often used as distribution points for rations destined for various camps. Given the terrible state of the roads leading to the camps, the vehicles from the provincial reeducation services often unloaded the rations at a military garrison, and detainees were then marched to carry them on their heads back to their respective camps. A walking trip from Ilumba to Base Central could take two or more days.Footnote 86 It was most likely on one of these trips that António met and fell in love with Filomena, who was in detention for smoking hemp. In his petition, António promised the authorities that if she continued with her vice after their marriage he would send her back to the camp himself.Footnote 87 The archival record is silent on the verdict regarding António's heartfelt request. Other requests to wed female detainees were less poignant.Footnote 88 But they all reveal how complex the world inside Mozambique's reeducation camps was. Here the elusive power of a modern ‘seeing machine’ and technicians of behavior was almost nonexistent. Romantic affairs, sexual licentiousness, drinking, and smoking characterized the carceral regime. In the context of extreme scarcity in which the reeducation camps functioned, an unintended and peculiar form of carcerality emerged beyond the control of the ruling party and its reformist ambitions.

CONCLUSION

Life inside Mozambique's reeducation camps was anything but orderly and regimentally strict. The conditions of austerity in which Frelimo implemented its revolutionary program produced a particular mode of carceral regime that was not dictated by technologies of disciplinary surveillance. Camp supervisors and detainees themselves defined the kind of internment regimen that prevailed in ways that subverted the aspirations of Frelimo leaders. Rather than being secluded institutions where supposed wayward misfits were reformed, reeducation camps were porous, indulgent, and lacked any kind of social hygiene. Although they were located in remote sites, there was no complete separation of ‘anti-socials’ or enemies of the revolution from society. In the rural areas where the camps were established, detainees were often in contact with local communities, where they exchanged their meager belongings for food, alcoholic drinks, hemp, and sex. Despite the panoptic ambitions of Frelimo authorities, it was not the ‘architectural apparatus’ and the unfailing eye of camp supervisors that ‘induced in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power’ in reeducation camps.Footnote 89 Here that role was played by something else: the remote location of the camps and the wilderness that surrounded them. Rather than the backlighting effect of a watchtower or armed guards with dogs, it was the roar of lions and other wild beasts that kept detainees in line. This was a different kind of panopticon, one that was regulated not by a modern ‘seeing machine’ with its abstract mechanisms of biopolitical power, but by the very untamed nature that defied modernity. This was a panopticon that had no regard for bodily legibility, not because the regime was uninterested in controlling people, but because the regime had little capacity to do so, given the conditions of austerity in which it had to operate. Surveillance, discipline, order, and social reform require resources that the Mozambican government did not possess.