1. Introduction

The Palaeozoic evolution of the Palaeo-Pacific Ocean is an enigmatic issue as its temporal and spatial features are controversial. Some researchers believe that the Pacific Ocean did not operate in the late Palaeozoic in central Asia and only affected NE Asia in the Early Mesozoic, while others have proposed that the Palaeo-Pacific Ocean may have already operated in the Palaeozoic or even earlier (Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010, Reference Xiao, Windley, Sun, Li, Huang, Han, Yuan, Sun and Chen2015).

As part of the Palaeo-Pacific Ocean, the Palaeo-Asian Ocean was consumed to form the Altaids (or the Central Asian Orogenic Belt, mainly developed from ~1.0 Ga to 250 Ma), one of the most important sites of juvenile crustal growth (Şengör et al. Reference Şengör, Natal’in and Burtman1993; Şengör & Natal’in, Reference Şengör and Natal’in1996; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004, Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010, Reference Xiao, Windley, Sun, Li, Huang, Han, Yuan, Sun and Chen2015, Reference Xiao, Windley, Han, Liu, Wan, Zhang, Ao, Zhang and Song2018; Windley et al. Reference Windley, Alexeiev, Xiao, Kröner and Badarch2007; Domeier & Torsvik, Reference Domeier and Torsvik2014) (Fig. 1). Therefore, the Altaids serve as an appropriate natural case for determining the systematic anatomy of the Palaeozoic evolution of the Palaeo-Pacific Ocean.

Fig. 1. (a) Schematic tectonic map of central Asia and adjacent regions (Şengör et al. Reference Şengör, Natal’in and Burtman1993; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Windley, Sun, Li, Huang, Han, Yuan, Sun and Chen2015). (b) Schematic geological map of Eastern Tianshan (modified after XBGMR, 1993, and Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004, Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010) showing the locations of the Permian volcanic rocks within the desert of the Turpan Basin. Major faults separate southern Tianshan, central Tianshan, the Yamansu Arc and the Dananhu–Haerlik Arc.

Over decades of study, a consensus has gradually been reached that the Altaids were formed through the successive lateral accretion of small continental blocks, arcs and accretionary complexes (Coleman, Reference Coleman1989; Şengör et al. Reference Şengör, Natal’in and Burtman1993; Dobretsov et al. Reference Dobretsov, Berzin and Buslov1995; Şengör & Natal’in, Reference Şengör and Natal’in1996; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Shu and Sun1997; Gao et al. Reference Gao, Li, Xiao, Tang and He1998; Buchan et al. Reference Buchan, Pfänder, Kröner, Brewer, Tomurtogoo, Tomurhuu, Cunningham and Windley2002; Bazhenov et al. Reference Bazhenov, Collins, Degtyarev, Levashova, Mikolaichuk, Pavlov and Voo2003; Li, Reference Li2004; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004, Reference Xiao, Shu, Gao, Xiong, Wang, Guo, Li and Sun2008b, Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010; JY Li et al. Reference Li, He, Xu, Li, Sun, Yang, Gao and Zhu2006 a; Windley et al. Reference Windley, Alexeiev, Xiao, Kröner and Badarch2007; Shi et al. Reference Shi, Liao, Hu and Yang2010), and through the emplacement of immense volumes of magma in a lateral accretionary, post-collision and/or intraplate extensional setting in the late Palaeozoic and early Mesozoic (Han et al. 1997, 1998, Reference Han, Song, Chen and Li2004; F Chen et al. Reference Jahn, Wu and Chen2000; Jahn et al. Reference Jahn, Wu and Chen2000; Wu et al. 2000, Reference Wu, Sun, Li, Jahn and Wilde2002; Jahn, Reference Jahn2004; ZH Chen et al. 2006; Windley et al. Reference Windley, Alexeiev, Xiao, Kröner and Badarch2007; Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Sun, Xiao, Li, Chen, Lin, Xia and Long2007; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014 c). To date, the architecture and style of orogenic collages is controversial, and there are two general classes of models. One model suggests that the Altaids formed through a prolonged and steady period of subduction–accretion, followed by the oroclinal bending of a single, long-lived giant magmatic arc complex or continental sliver (Şengör et al. Reference Şengör, Natal’in and Burtman1993; Şengör & Natal’in, Reference Şengör and Natal’in1996; Yakubchuk et al. Reference Yakubchuk2004; Johnston et al. Reference Johnston, Weil and Gutierrez-Alonso2013; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Windley, Han, Liu, Wan, Zhang, Ao, Zhang and Song2018). Conversely, another hypothesis suggests that the Altaids may have grown through the subduction and accretion of multiple oceanic basins accompanied by the development of individual magmatic arc terranes and microcontinents (Coleman, Reference Coleman1989; Dobretsov et al. Reference Dobretsov, Berzin and Buslov1995; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Shu and Sun1997; Buchan et al. Reference Buchan, Pfänder, Kröner, Brewer, Tomurtogoo, Tomurhuu, Cunningham and Windley2002; Windley et al. Reference Windley, Alexeiev, Xiao, Kröner and Badarch2007; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004, Reference Xiao, Han, Yuan, Sun, Lin, Chen, Li, Li and Sun2008 a, 2009, Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010, Reference Xiao, Windley, Sun, Li, Huang, Han, Yuan, Sun and Chen2015). Geologists agree that the Altaids underwent an important tectonic transition in the Permian, but it is debated whether the Palaeo-Pacific Ocean had closed (Coleman, Reference Coleman1989; Han et al. Reference Han, He, Wang and Hang1998; Li, Reference Li2004; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004, Reference Xiao, Han, Yuan, Chen, Sun, Lin, Li, Mao, Zhang, Sun and Li2006, Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Lesher, Yang, Li and Sun2004; JY Li et al. Reference Li, He, Xu, Li, Sun, Yang, Gao and Zhu2006 a; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang and He2006; Qin et al. Reference Qin, Su, Sakyi, Tang, Li, Sun, Xiao and Liu2011).

The Chinese East Tianshan is the easternmost segment of the Tianshan mountain range in the southern Altaids; it occupies a key position in the Altaids (Fig. 1). In the early Permian, large volumes of volcanic rock and intrusions developed along regional fault belts and/or extensive basins of the East Tianshan (Fig. 1b; Table 4 further below), creating a unique opportunity to study the geological evolution of the southern Altaids. Geologists have conducted systematic studies of Cu–Ni ore-bearing mafic–ultramafic intrusions (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Shu and Sun1997; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Ma, Guo, Sun, Guo, Xu and Hu2002; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004, Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Lesher, Yang, Li and Sun2004; JY Li et al. Reference Li, Song, Wang, Li, Sun and Qi2006 b; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Han, Sun, Yuan, Yan, Li, Yong and Zhang2006, Reference Mao, Xiao, Han, Yuan and Sun2008, Reference Mao, Xiao, Windley, Han, Qu, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Guo2012, Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014c; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Guo, Han and Wang2006 a; Ao et al. 2010; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Shu and Santosh2011; Qin et al. Reference Qin, Su, Sakyi, Tang, Li, Sun, Xiao and Liu2011), and diverse models have been applied to the Permian geological evolution of the East Tianshan (e.g. the post-collision model (Han et al. Reference Han, He, Wang and Hang1998; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Lesher, Yang, Li and Sun2004; JY Li et al. Reference Li, He, Xu, Li, Sun, Yang, Gao and Zhu2006 a; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang and He2006; Qin et al. Reference Qin, Su, Sakyi, Tang, Li, Sun, Xiao and Liu2011), the oblique subduction model (Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004, Reference Xiao, Han, Yuan, Chen, Sun, Lin, Li, Mao, Zhang, Sun and Li2006, Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Han, Yuan and Sun2008; Ao et al. Reference Ao, Xiao, Han, Mao and Zhang2010) and the mantle plume model (Pirajno et al. Reference Pirajno, Mao, Zhang and Chai2008; Qin et al. Reference Qin, Su, Sakyi, Tang, Li, Sun, Xiao and Liu2011; Su et al. Reference Su, Qin, Sun, Tang, Sakyi, Chu, Liu and Xiao2012; Tang et al. Reference Tang, Qin, Su, Sakyi, Liu, Mao, Santosh and Ma2013). The Permian volcano of the East Tianshan has rarely been reported. Permian volcanic rocks in Turpan Basin contains basalt, andesite, dacite and rhyolite, offering new and detailed information on patterns of magmatism in relation to their regional geology and tectonic settings. This paper provides a detailed account of the occurrence and formation of magma relative to the geodynamic development of the southern margin of the Altaids in the Permian.

2. Geological setting

The Chinese East Tianshan is a 300 km wide and 1500 km long orogenic collage (Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004, 2006, Reference Xiao, Han, Yuan, Sun, Lin, Chen, Li, Li and Sun2008 a, Reference Xiao, Shu, Gao, Xiong, Wang, Guo, Li and Sun b, Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010) consisting of the following tectonic units: South Tianshan, Central Tianshan, the Yamansu Arc and the Dananhu–Haerlik Arc (Fig. 1).

The South Tianshan, located between the Central Tianshan Arc and Tarim Craton (Fig. 1), includes various Silurian–Carboniferous rocks, including turbidites, ophiolites (Silurian – late Carboniferous), cherts, volcaniclastic rocks, mélanges and Devonian – early Carboniferous high-pressure metamorphic rocks (eclogite and blueschist) (Windley et al. Reference Windley, Allen, Zhang, Zhao and Wang1990; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Shu and Sun1997; Gao et al. Reference Gao, Li, Xiao, Tang and He1998; Li, Reference Li2004; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004).

The Central Tianshan Arc situated between the Aqikekuduke–Shaquanzi and Kawabulake–Xingxingxia faults (Fig. 1) includes a Precambrian amphibolite facies basement, Palaeozoic plutons and volcanic rocks. The Precambrian basement consists of gneisses, quartz schists, migmatites and marbles dated from 900 to 1900 Ma (Gu et al. Reference Gu, Yang, Tao, Yan, Li, Wang and Liu1990; Xiu et al. Reference Xiu, Yu and Li2002; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Guo, Zhang, Li and Zhen2004; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Gu, Yang, Wu, Wang and Min2004; Hu et al. 2006, Reference Hu, Wei, Jahn, Zhang, Deng and Chen2010; Li et al. Reference Li, Liu, Song, Wang and Chen2009; Shi et al. Reference Shi, Liao, Hu and Yang2010). Palaeozoic arc volcanic rocks, volcanic clastics and intrusions also formed from the Ordovician to early Permian (Li et al. Reference Li, Wang, Li, Kang, Yu, Han and Ma2001; Li, Reference Li2004; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Gu, Yang, Wu, Wang and Min2004; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Li, Wang, Gao and Song2006; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Han, Zhang, Deng and Liu2007; Hu et al. Reference Hu, Wei, Zhang, Deng and Chen2007; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Wang, Xiao, Fang, Wang and Yu2014 a). The Aqikuduke fault belt is marked by Palaeozoic ophiolites, ductile strike-slip faults and mafic–ultramafic intrusions (Windley et al. Reference Windley, Allen, Zhang, Zhao and Wang1990; Shu et al. Reference Shu, Charvert, Guo, Lu and Laurent-Charvet1999; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004, Reference Xiao, Han, Yuan, Sun, Lin, Chen, Li, Li and Sun2008 a; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Li, Mo, Chen, Lu, Mei and Deng2005; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Han, Sun, Yuan, Yan, Li, Yong and Zhang2006).

The Yamansu Arc comprises Devonian–Carboniferous calc-alkaline andesites, basalts, rhyolites, tuffs and volcaniclastic rocks interbedded with fine-grained clastic rocks and carbonates that have undergone sub-greenschist facies metamorphism, together with granitic intrusions (Ji et al. Reference Ji, Tao and Yang1994; Yang et al. 1996, Reference Yang, Ji, Zhang and Zeng1998; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Shu and Sun1997; Gu et al. Reference Gu, Hu, Chu, Yu and Xiao1999; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004).

The Dananhu–Haerlik Ordovician–Carboniferous Island Arc located between the Kalameili and Kangguer faults (Fig. 1b) consists of Ordovician to Permian tholeiites to calc-alkaline mafic–felsic lavas, volcanoclastics, tuffs and clastic sediments (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Shu and Sun1997; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004; Hou et al. Reference Hou, Tang, Liu and Wang2005; Tang et al. Reference Tang, Gu, Zheng, Fang, Zhang, Gao, Wang, Wang and Zhang2006). Abundant arc-related granitic intrusions range in age from the Ordovician to early Permian (Li et al. Reference Li, Chen, Lu, Yang, Guo and Mei2004; FW Chen et al. Reference Chen, Li, Chen, Wang, Wang, Liu, Tang and Zhou2005; Hou et al. Reference Hou, Tang, Liu and Wang2005; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Li, Gao and Yang2005; Chao et al. Reference Chao, Tu, Zhang, Ren, Li and Dong2006; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Zhong and Li2006; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Fang, Wang, Wang and Wang2010). The earlier Permian mafic–ultramafic complex zone is located along the southern margins of the arc and stretches across several hundreds of kilometres (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Shu and Sun1997; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Yang, Qu, Du, Wang and Han2002; Han et al. Reference Han, Song, Chen and Li2004; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Lesher, Yang, Li and Sun2004; Qin et al. Reference Qin, Su, Sakyi, Tang, Li, Sun, Xiao and Liu2011).

Early Permian volcanic rocks occur around the Kalatage and Dananhu Palaeozoic geological inlier in the Turpan Basin (Figs 1b, 2). They are classified as a middle Permian Aerbashayi Formation (XBGMR, 1993; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Ma, Guo, Sun, Guo, Xu and Hu2002; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014 c) composed of basalts and basaltic andesites interbedded with minor rhyolites in the lower formation and with tuffs, rhyolites and dacites in the upper formation. The Aerbashayi Formation unconformably covers the upper Carboniferous Qishan Formation or the Ordovician–Silurian Volcanic Arc Group (or the lower Devonian Kaltage Formation) and is unconformably overlain by the upper Permian Kula Formation, the low Jurassic Sangonghe Formation and the Quaternary.

Fig. 2. Geological map of the Kalatage inlier and of an adjacent area of the Turpan Basin (modified after Mao et al. Reference Mao, Fang, Wang, Wang and Wang2010, Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014c).

A number of early Permian mafic complexes occur along faults of the Kalatage inlier (Mao, Reference Mao2014). Adjacent are Ordovician (Devonian)–Jurassic low-grade volcanic rocks, volcaniclastic rocks and clastic sediments (Tang et al. Reference Tang, Gu, Zheng, Fang, Zhang, Gao, Wang, Wang and Zhang2006; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Fang, Wang, Wang and Wang2010, Reference Mao, Wang, Xiao, Fang, Yu, Ao and Zhang2014b, Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang c, Reference Mao, Wang, Fang, Yu, Zhu, Fu and Huang2015). The Ordovician–Silurian Volcanic Group (or lower Devonian Kaltage Formation) consists of calc-alkaline basic–felsic volcanic and volcaniclastic rocks, including basalts, andesites, dacites, rhyolites and volcaniclastic rocks (Qin et al. Reference Qin, Fang, Wang and Wang2001; WQ Li et al. Reference Li, Wang, Wang and Xia2006; Tang et al. Reference Tang, Gu, Zheng, Fang, Zhang, Gao, Wang, Wang and Zhang2006; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Fang, Wang, Wang and Wang2010, Reference Mao, Wang, Xiao, Fang, Yu, Ao and Zhang2014b, Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang c, Reference Mao, Wang, Fang, Yu, Zhu, Fu and Huang2015). The ages of these rocks are poorly constrained (e.g. the lower Devonian (Qin et al. Reference Qin, Fang, Wang and Wang2001; Tang et al. Reference Tang, Gu, Zheng, Fang, Zhang, Gao, Wang, Wang and Zhang2006), the Ordovician to Devonian (Mao et al. Reference Mao, Fang, Wang, Wang and Wang2010, Reference Mao, Wang, Xiao, Fang, Yu, Ao and Zhang2014b, Reference Mao, Wang, Fang, Yu, Zhu, Fu and Huang2015; Mao, Reference Mao2014) or the Ordovician–Silurian (WQ Li et al. Reference Li, Wang, Wang and Xia2006)). The lower Devonian Dananhu Formation, which unconformably overlies Ordovician–Silurian Arc volcanic sequences, consists of biogenic carbonates, clastic sediments and interbedded volcanic rocks. The Upper Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian) Qishan Formation, unconformably overlying the lower Devonian Dananhu Formation, consists of calc-alkaline basaltic and andesitic volcanic rocks, tuffs and clastic sediments. The lower Permian Aqikebulake Formation (P1a) consists of basic–felsic volcanic rocks and sediments. The upper Permian Kula Formation consists of clastic sediments, and the Triassic is absent in the area. The lower Jurassic Sangonghe Formation contains black shales, shaly sandstones, sandstones, and coalbeds, which lie unconformably on older strata.

3. Sampling and petrography

Figures 1b and 2 show that early Permian volcanic rocks are located in the Turpan Basin and around the Kalatage and Dananhu Palaeozoic geological inlier (Fig. 2). In this study, we mainly research rocks around the Kalatage Palaeozoic geological inlier. Our study reveals a geological section of the southern margins of the Kalatage inlier (Fig. 3). In this section (Fig. 3), early Permian volcanic rocks are mainly composed of clastic sedimentary, amygdaloidal basalts, basalts, basaltic andesites and andesites interbedded with minor rhyolites. From north to south, early Permian volcanic rock formations can be divided into six volcanic–sedimentary sequences. At the bottom are amygdaloidal basaltic andesites and coherent volcaniclastic rocks (11TH01), which unconformably cover the upper Carboniferous Qishan Formation and Ordovician–Silurian volcanic sequences. Next is the sedimentary sequence, which is unconformably covered at the base of volcanic rocks. The third sequence unconformably located on the second sedimentary sequence is composed of sedimentary rocks and interbedded with rhyolites (11TH02 and 13TH01), and a sequence of conglomerates is positioned at the bottom of the sequence. The fourth sequence unconformably covering the third sequence is composed of amygdaloidal basaltic andesites (11TH03 and 13TH03) and coherent volcaniclastic rocks interbedded with a few basalts and rhyolite, which are unconformably covered with a thin layer of rhyolites (11TH04). Thick purple to grey amygdaloidal basalts and volcaniclastic rocks unconformably covering the fourth sequence occur in the upper part of the volcanic formation (11TH05). At the top is a sequence of purple amygdaloidal andesites (11TH06) and volcaniclastic rocks, which are unconformably covered on the fifth sequence and by the low Jurassic Sangonghe Formation. The section suggests a pattern of volcanic eruption varying from basic to intermediate-felsic.

Fig. 3. The geological section for the Permian volcanic rocks in the southern part of the Kalatage inlier.

To determine the magma composition and age of volcanic rocks in the Turpan Basin, different types of volcanic rocks collected from the Kalatage inlier were analysed for whole rock major, rare earth and trace elements; Sr–Nd isotopic compositions; and basaltic andesites and rhyolite for zircon laser ablation – inductively coupled plasma – mass spectormetry (LA-ICP-MS) U–Pb dating. The sampling locations are shown in geological cross-sections presented in Figures 2 and 3.

Basalts include fine-grained, porphyritic and vesicular types that are greyish-green and brown to purple. The rocks present typical quench textures with abundant phenocrysts (5–40 %) embedded within a fine-grained groundmass (Fig. 4a, b, c). Plagioclase (5–15 %) with a composition of An51–An62, clinopyroxene aggregates and subordinate orthopyroxene (2–20 %) with a composition of Wo45–Wo50, En37–En44 and Fs6–Fs16) are of the phenocryst phases along with minor Fe–Ti oxides (1–3 %). The fine-grained groundmass is composed of plagioclase, glass, olivine and Ti-magnetite. Some basalt samples have long plate plagioclase phenocrysts of 0.5–3 cm length and fine-grained olivine phenocrysts (with a composition of Mg# = 65–74 and Cr# = 1–38).

Fig. 4. Microphotographs of volcanic samples around the Kalatage inlier in the Turpan Basin, NW China. (a, b, c) Basalts; (d) basaltic andesites; (e) andesite; (f) rhyolite. Ol – olivine; Px – pyroxene; Pl – plagioclase; Qz – quartz.

The basaltic andesites and andesites, which are brown to purple, are mainly porphyritic and vesicular and exhibit typical quench textures with abundant phenocrysts (30–50 %) embedded within a fine-grained groundmass (Fig. 4d, e). Plagioclase (30–45 %) and clinopyroxene aggregates (2–5 %) are of the phenocryst phases. The fine-grained groundmass is composed of plagioclase, glass, olivine and Ti-magnetite.

The rhyolites include fine-grained, porphyritic and vesicular types that are grey-white, brown or purple. Rhyolites have a typical porphyritic texture with a few quartz and alkali feldspars as phenocrysts in an aphanitic matrix of the same minerals (Fig. 4f). Quartz phenocrysts are euhedral and 1–3 mm in diameter and are associated with euhedral alkali feldspar phenocrysts of 1–5 mm length. Accessory minerals include zircon, apatite and titanite.

4. Analytical techniques

4.a. Geochronology

Zircon grains were separated using conventional heavy liquid and magnetic techniques. Representative zircon grains were handpicked under a binocular microscope and mounted in an epoxy resin disc. We used the Sensitive High-Resolution Ion Microprobe (SHRIMP) and LA-ICP-MS zircon U–Pb dating technique to complete the two samples. To identify internal features of the zircons (zoning, structures, alteration, fractures, etc.), cathodoluminescence (CL) images were collected using a Cameca electron microprobe for SHRIMP based at the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences (Beijing), and LA-ICP-MS dating was conducted at the SEM-EDS-EBSD-CL Laboratory of Peking University (Beijing).

4.a.1. SHRIMP zircon U–Pb dating

The SHRIMP experiments were carried out at the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences (Beijing). U–Th–Pb isotopic analyses were performed using SHRIMP-II. Further details on the analysis of zircons using SHRIMP are described in Song et al. (Reference Song, Zhang, Wan and Jian2002 b). Inter-element fractionation ion emissions of zircon were corrected relative to RSES reference TEMORA 1 (417 Ma; Black et al. Reference Black, Kamo, Allen, Aleinkoff, Davis, Korsch and Foudoulis2003). Data reduction was carried out using the Isoplot/Ex v. 2.49 program (Ludwig, Reference Ludwig2001).

4.a.2. LA-ICP-MS zircon U–Pb dating

Experiments were carried out at the LA-ICP-MS Laboratory of the University of Science and Technology of China. Uranium, Th and Pb concentrations were calibrated using 29Si as an internal standard and NIST SRM 610 as an external standard. 207Pb/206Pb and 206Pb/238U ratios were calculated using GLITTER 4.0 (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Amory, Zinniker, Lamb, Graham, Affolter and Badarch2008) and were then corrected using Harvard zircon 91500 as an external standard. The 207Pb/235U ratio was calculated from the 207Pb/206Pb and 206Pb/238U values. Common Pb was corrected according to the method proposed by Andersen (Reference Andersen2002). Weighted mean U–Pb ages and concordia plots were processed using ISOPLOT 3.0. The procedure is described at length in Xie et al. (Reference Xie, Zhang, Zhang, Sun and Wu2008).

4.b. Geochemistry and isotopic studies

Major oxide and trace element experiments were carried out at the analytical laboratory of the Beijing Research Institute of Uranium Geology. Major elements were determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry with analytical errors of less than 5 %. A loss on ignition (LOI) was determined after igniting the sampled powder at 1000 °C for 1 hour. Trace elements, including rare earth, were identified by ICP techniques, analytical procedures of which are described in Zhou et al. (Reference Zhou, Sun, Zhang and Chen2002). Rb–Sr and Sm–Nd isotopic ratios were measured with a Finnigan MAT262 thermal ionization mass spectrometer (TIMS) housed at the Laboratory for Radiogenic Isotope Geochemistry of the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing. Measurements were carried out following the isotope dilution procedures developed by Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Hagner and Todt2000) and Zhou et al. (Reference Zhou, Sun, Zhang and Chen2002). A static multi-collection mode was used for the measurements. A traditional cation exchange technique was adopted for chemical separation. Mass fractionation corrections for Sr and Nd isotopic ratios were based on 86Sr/88Sr = 0.1194 and 146Nd/144Nd = 0.7219. Repeated measurements of La Jolla Nd standard and NBS987 during the measurement period gave values of 143Nd/144Nd = 0.511861 ± 9 (2σ) and 87Sr/86Sr = 0.710254 ± 10 (2σ), respectively. Total procedural blanks for Sr and Nd are valued at ~10−9 and ~10−11 g, respectively.

5. Results

Two new zircon U–Pb dates for andesite and rhyolite are presented in Figure 4 and Table 1, respectively. Major and trace elements and Sm–Nd and Rb–Sr isotope data for the volcanic rocks are listed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 1. U–Pb SHRIMP and LA-ICP-MS isotopic data of zircon ages for the basaltic andesites and rhyolite from the Kalatage area in the Turpan Basin, NW China

Table 2. Major (wt %) and trace element (ppm) data for the Permian volcanic rocks from the Kalatage area in the Turpan Basin, NW China

Table 3. Sm–Nd and Rb–Sr isotopic analytical results of the Permian volcanic rocks from Kalatage area in the Turpan Basin, NW China

5.a. The age of basaltic andesites and rhyolite

Zircons separated from the basaltic andesite rocks (13TH03) are mostly colourless, transparent and well crystallized, with grain sizes of 100 to 200 μm diameter. CL images show that most of the zircons have a single composition and rhythmic zones typical of basic magmatic rocks, and some grains have dark and bright rims and black to dark cores, indicating that they are xenocrystic (Fig. 5a). SHRIMP U–Pb isotopic analytical results on zircon grains taken from the andesite sample are listed in Table 1 and are presented in Figure 5b. The samples are plotted along the concordant line with three groups of zircon U–Pb isotopic ages (Fig. 5b): 11 analysed zircons yield a 206Pb/238U weighted average age of 285.1 ± 5.9 Ma (MSWD = 2.3, n = 11), which we interpret as the crystallization age of the andesite; six analysed zircons yield a 206Pb/238U weighted average age of 357 ± 13 Ma (MSWD = 2.9, n = 6), and two zircon grains yield a 206Pb/238U age of 427 ± 7 Ma and 453 ± 10 Ma, respectively. These grains present quite complicated CL formations with dark or bright rims and black to dark cores, indicating that they are xenocrystic.

Fig. 5. CL images of typical zircons and concordia U–Pb diagram for rhyolites and basaltic andesites from the Kalatage area in the Turpan Basin. (a, b) CL images and LA-ICP-MS analytical data for the basaltic andesite (13TH03); (c, d) CL images and SHRIMP analytical data for the rhyolite (11TH04).

Zircons separated from the rhyolite (11TH04) are mostly colourless, transparent and well crystallized with grain sizes of 100 to 200 μm diameter, and CL images show that all of the zircons include special mottled patches with rhythmic zones (Fig. 5c). LA-ICP-MS U–Pb isotopic analytical data for zircon grains taken from the rhyolite sample are listed in Table 1 and are presented in Figure 5d. The samples concentrate in a small area along the concordia line (Fig. 5d), and 19 analysed zircons yield a 206Pb/238U weighted average age of 275.3 ± 1.8 Ma (MSWD = 1.8, n = 19).

An early Permian volcanism eruption was reported in the Turpan (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Ma, Guo, Sun, Guo, Xu and Hu2002) Basin and Shaerhu area of the Turpan Basin (285 Ma, Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014 c; Table 4). Our analysis results show that the rhyolite erupted after the basaltic andesites, suggesting a c. 10 Ma volcanism eruption range of 285 to 275 Ma occurring in the early Permian.

Table 4. The ages of early Permian volcanic rocks and mafic–ultramafic intrusions from Altai to Beishan in China

SIMS: secondary ice mass spectrometry.

5.b. Geochemical characteristics

Data on the major trace elements Rb–Sr and Sm–Nd are listed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Amygdale basalt, basaltic andesite and andesite show relatively variable high LOI (1.37–3.43 %), as the amygdales fill volatile-water-enriched minerals (e.g. carbonate and chlorite) not completely removed through the crushing process.

5.b.1 Major elements

The basalts present relatively high TiO2 (2.14–2.59 %), CaO (8.01–8.85 %), MgO (5.37–6.53 %) and Mg# (49.5–54.8) levels and lower alkali levels (Na2O + K2O = 3.58–3.93 %, K2O/Na2O = 0.06–0.10) and are classified as tholeiitic magma in a FeOt/MgO–SiO2 diagram (Fig. 6b; Myashiro, Reference Myashiro1974). Compared to the basalt, the basaltic andesites (trachyandesite) present lower TiO2 (1.13–1.45 %), CaO (2.18–3.43 %) and MgO (3.63–4.9 %, Mg# = 48–58) levels and higher alkali levels (Na2O + K2O = 3.85–6.32 %). The andesites (trachyandesites) present SiO2 levels of 58.17 to 60.52 %, CaO levels of 8.01 to 8.85 %, MgO levels of 5.37 to 6.53 %, Mg# levels of 49.5 to 54.8, alkali levels of Na2O + K2O = 5.10–9.13 %, K2O/Na2O = 0.14–0.99 and low TiO2 levels of 0.84 to 0.93 %. They are metaluminous with A/CNK values of between 0.81 and 1.01.

The rhyolites are highly siliceous (SiO2 = 72.61–83.54 %), rich in total alkalis (Na2O + K2O = 4.09–11.02 %), but low in Al and Ti, with Al2O3 = 7.97–13.35 % and TiO2 = 0.06–0.10 %. The rhyolites have relatively low ferromagnesian compositions (MgO = 0.15–0.53 % and Fe2O3t = 0.19–1.89 %). They are metaluminous to weakly peraluminous with A/CNK values ranging from 0.67 to 1.03 and with A/NK values ranging from 1.06 to 1.19 (Table 2). The rhyolites can be divided into low- and high-silica types with apparent geochemical differences between them and with SiO2 levels ranging from 72.61 to 73.94 % (11TH04 and 13KL52) and from 80.98 to 83.54 % (11TH02 and 13TH01), respectively. The high-silica samples present obviously lower K2O and Al2O3 levels than the low-silica samples (K2O = 0.05–0.10 % and 5.99–10.35 % and Al2O3 = 7.97–8.86 % and 5.99–10.35 % respectively), showing that the high-silica rocks underwent an advanced fractionation of K-feldspar. In summary, the different types of volcanic rock are alkaline to subalkaline series magma, and the SiO2 content of the samples ranges from 46.27 % to 83.54 % (Fig. 5). The samples are classified as basalts, basaltic andesites (basaltic trachyandesites), andesites (trachyandesites) and rhyolites in a total alkali–silica (TAS) diagram (Fig. 6a; Le Maitre et al. Reference Le Maitre, Bateman, Dudek, Keller, Lameyre, Bas, Sabine, Schmid, Sorensen, Streckeisen, Woolley and Zanettin1989), and the basalts and basaltic andesites are composed of tholeiitic series magma (Fig. 6b; Myashiro, Reference Myashiro1974). As demonstrated by the binary diagrams (Figs 6, 7), the rocks show positive correlations between SiO2 and TiO2, Al2O3, CaO, MgO, MnO, P2O5, Cr, Ni, Co and Sr levels and negative correlations between SiO2 and K2O, Y and Zr levels.

Fig. 6. Geochemical classification diagrams for the Permian volcanic rocks from the Kalatage area in the Turpan Basin. (a) SiO2 (wt %) vs K2O + Na2O (TAS, wt %) diagram (Le Maitre et al. Reference Le Maitre, Bateman, Dudek, Keller, Lameyre, Bas, Sabine, Schmid, Sorensen, Streckeisen, Woolley and Zanettin1989). The boundary line between alkaline and tholeiitic rocks based on Irvine & Baragar (Reference Irvine and Baragar1971). (b) FeOt/MgO vs SiO2 diagram (Myashiro, Reference Myashiro1974).

Fig. 7. Binary diagrams illustrating SiO2 vs major and trace elements of Permian volcanic rocks from the Kalatage area in the Turpan Basin. Values are given in wt % for oxides and in ppm for trace elements. Symbols used are the same as those used in Figure 6.

5.b.2. Trace and rare-earth elements

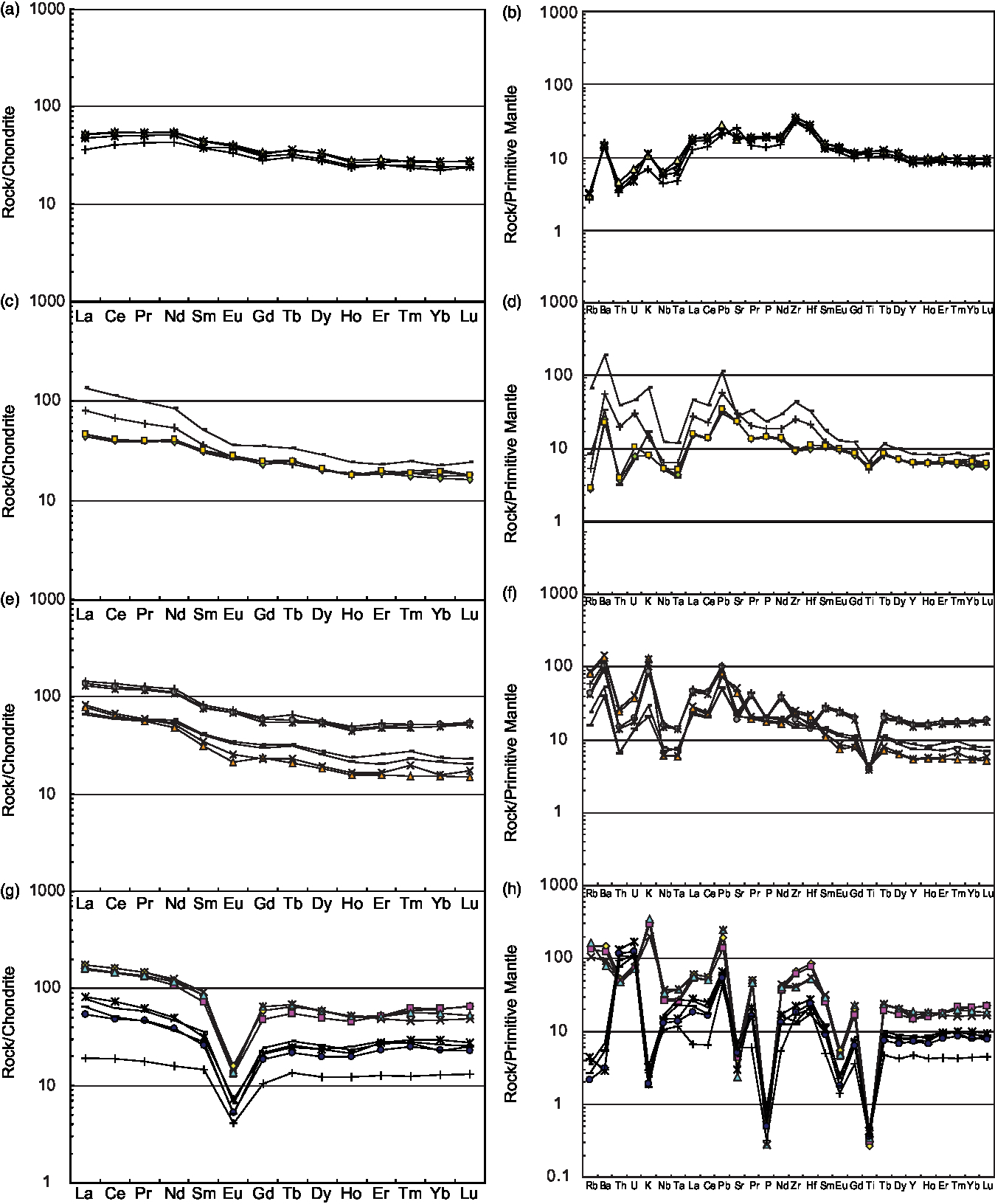

The basalts display uniform enrichment of light rare earth elements (LREEs) across the chondrite-normalized REE plots with (La/Yb)N ratios of 1.65 to 1.99 (Fig. 8a). They show slightly positive Eu anomalies (δEu = 1.03–1.11), suggesting that plagioclase fractionated and accumulated throughout the evolution of the parental magma. In the primitive mantle-normalized spider diagram (Fig. 8b), basalts are characterized by low HFSE (high-field-strength elements)/LREE ratios (Nb/La = 0.35–0.36); an enrichment of Pb, Sr, Zr and Hf; and relatively negative Rb, Th, U, Nb and Ta anomalies. These features are similar to those of continental N-MORB/E-MORB-type basalts (Condie, Reference Condie1989; Wilson, Reference Wilson1989), suggesting that the extension of basins reached maximum levels in middle and late stages of extensional volcanic movement.

Fig. 8. Chondrite-normalized REE and primitive mantle (PM)-normalized multi-element diagrams for Permian volcanic rocks from the Kalatage area of the Turpan Basin. (a, b) Basalt samples, (c, d) basaltic andesite samples, (e, f) andesite samples, and (g, h) rhyolite samples from the Kalatage area of the Turpan Basin. Chondrite values are taken from Boynton (Reference Boynton and Henderson1984). The PM, N-MORB, E-MORB (enriched mid-ocean ridge basalt) and OIB (oceanic island basalt) values are taken from Sun & McDonough (Reference Sun, McDonough, Sauders and Norry1989).

The basaltic andesites display LREE enrichment chondrite-normalized REE patterns ((La/Yb)N = 2.16–6.07) with slightly negative to positive Eu anomalies (δEu = 0.86–1.04) (Fig. 8c). In the primitive mantle-normalized spider diagram, the samples show a moderate enrichment of large-ion lithophile elements (LILE; e.g. Rb, Ba, U, Th, K and Sr), Pb, Zr and Hf elements and negative Nb, Ta and Ti anomalies (Fig. 8d).

The andesites present REE and trace element chemical features similar to those of the basaltic andesites with LREE enrichment chondrite-normalized REE patterns ((La/Yb)N = 2.63–5.31) and slightly negative to positive Eu anomalies (δEu = 0.79–1.07) (Fig. 8e). The samples are characterized by an enrichment of LREE, Rb, Ba, Th, U, K, Pb elements and by relatively negative Nb, Ta and Ti anomalies in the primitive mantle-normalized spider diagram (Fig. 8f).

Rhyolites are highly fractionated magmas with high silica, high alkali, low TiO2 and ferromagnesian compositions. The chondrite-normalized REE plot yields two tightly clustered groups where low-silica rhyolites present higher REE levels and more enriched Rb, Ba, K, Pb, Zr and Hf elements (Fig. 8g, h). The high-silica rhyolites display depleted Rb, Ba and K levels, suggesting that the rocks underwent varying degrees of K-feldspar fractionation. They are characterized by tetrad effect patterns (V and/or M type) (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Masuda and Shabani1992, Reference Zhao, Xiong, Han, Wang, Wang, Bao and Jahn2002; Jahn et al. Reference Jahn, Wu, Capdevila, Martineau, Zhao and Wang2001) (Fig. 8g) with a strong negative Eu anomaly (Eu/Eu* = 0.18–0.33). The samples are characterized by non-CHARAC (charge-and-radius-controlled) trace element behaviours with Rb, K, Pb, Zr and Hf enrichment; relatively high negative Nb anomalies; pronounced negative Ba, Sr and Eu anomalies consistent with feldspar fractionation; and negative Ti anomalies with titanite/ilmenite fractionation (Fig. 8h). These trace features may be attributed to intense interactions between high-fractionation magmas and aqueous hydrothermal fluids (likely rich in F and Cl) (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Masuda and Shabani1992, Reference Zhao, Xiong, Han, Wang, Wang, Bao and Jahn2002; Jahn et al. Reference Jahn, Wu, Capdevila, Martineau, Zhao and Wang2001).

In summary, these volcanic rocks are characterized by variable LREE-enriched patterns ((La/Yb)N = 1.49–6.07), a range of slightly positive to highly negative Eu anomalies (Eu/Eu* = 0.18–1.11) and relatively more depleted Nb, Ta, P and Ti elements from basalt to rhyolite (Fig. 8). These features suggest that plagioclase played an important role in partial melting and subsequent fractional crystallization.

5.b.3. Sr–Nd isotope

The Permian volcanic rocks have 87Rb/86Sr ratios of 0.0106 to 2.616, 87Sr/86Sr ratios of 0.70348 to 0.71652 and a relatively low initial Sr ((87Sr/86Sr) i = 0.70342–0.70591, i = 285 Ma). They have 147Sm/144Nd ratios of 0.1174 to 0.1615, high 143Nd/144Nd ratios of 0.51275 to 0.51296 and relatively high (143Nd/144Nd) i (0.51250–0.51269) and ϵ Nd(t) (4.6–8.2, t = 285 Ma) values (Fig. 9). The basalts are characterized by the highest ϵ Nd(t) (ϵ Nd(t) = 7.1–7.6) values and the lowest (87Sr/86Sr) i ratios ((87Sr/86Sr) i = 0.70342–0.70363) (Fig. 9). Basaltic andesites present the lowest ϵ Nd(t) value of 4.6 and moderate (87Sr/86Sr) i ratios ((87Sr/86Sr) i = 0.70428) (Fig. 9). Andesites present moderate ϵ Nd(t) values of 6.9 to 8.2 and (87Sr/86Sr) i ratios of ((87Sr/86Sr) i = 0.70390–0.70401) (Fig. 9). Rhyolites present moderate ϵ Nd(t) values ranging from 5.1 to 7.5 and the highest (87Sr/86Sr) i ratios ((87Sr/86Sr) i = 0.70522–0.70591) (Fig. 9). In summary, the volcanic rocks display high ϵ Nd(t) values that vary little and strong variations in (87Sr/86Sr) i ratios.

Fig. 9. ϵ Nd(t) vs initial (87Sr/86Sr) i diagram for volcanic rocks from the Kalatage area of the Turpan Basin. DM, Depleted mantle; BSE, bulk silicate earth; EMI and EMII, enriched mantle; HIMU, mantle with high U/Pb ratio; PREMA, frequently observed mantle compositions (Zindler & Hart, Reference Zindler and Hart1986). Symbols used are the same as in Figure 6.

6. Discussion

6.a. Petrogenesis of Permian volcanic rocks

The mafic rocks are tholeiitic in nature. Their relatively high Mg# values (48–58) together with their MgO (5.37–6.53 wt %), Cr (22–65 ppm) and Ni content (51–73 ppm) indicate that mafic magmas of the Turpan Basin were derived from a mantle source and may have been produced from variably fractionated melts and not from primitive magmas. In addition, the basalts are enriched with LREEs, LILEs (e.g. Ba, K and Sr), Pb, Zr, Hf and elements depleted of HFSE (e.g. Nb (Nb/La = 0.35–0.36) and Ta), strongly suggesting a subduction zone origin/arc affinity and resembling primitive arc tholeiites (Pearce & Cann, Reference Pearce and Cann1973). According to the Th/Yb vs Nb/Yb diagram (Fig. 10a; Pearce, Reference Pearce and Thorpe1982, Reference Pearce2008), the samples fall obliquely, crossing the mantle array and showing that the samples evolved from N-MORB (normal mid-ocean ridge basalt)-like sources with a significant degree of fractional crystallization (FC) coupled with assimilation by low radiogenic Sr but high Th levels. Moreover, the basalts display relatively high ϵ Nd(t) (ϵ Nd(t) = 7.1–7.6) values; low (87Sr/86Sr) i ratios ((87Sr/86Sr) i = 0.70342–0.70363); and depleted Rb, Th and U elements (Fig. 8b), suggesting derivation from a depleted mantle source. The Tb (or Sm)/Yb ratio can be used to estimate the depth of melting, as it is insensitive to the effects of fractional crystallization (McKenzie & O’Nions, Reference McKenzie and O’Nions1991; K Wang et al. Reference Wang, Plank, Walker and Smith2002). The basalt to andesite samples have low (Tb/Yb)P (1.12–1.51 < 1.80) ratios, clearly showing that melting occurred in the absence of garnet (K Wang et al. Reference Wang, Plank, Walker and Smith2002). In the (La/Yb)p vs (Tb/Yb)P diagram (Fig. 10b), our data fall below the garnet–spinel transition line for peridotite and present nearly flat to slightly fractionated chondrite-normalized heavy rare earth elements (HREE) patterns ((La/Yb)N = 1.65–6.07), indicating that primitive magma from these rocks may have originated from a garnet-free mantle. In conclusion, it is inferred that the petrogenesis of the mafic rocks was dominated by a process of mixing between basaltic magmas similar to MORBs from asthenospheric (depleted end-member mantle) and arc-like magmas (Wilson, Reference Wilson2001; Condie, Reference Condie2005). Basaltic andesites and andesites have arc-related geochemical characteristics that display moderate TiO2 levels; LREE enrichment; LILE (e.g. Rb, Ba, U, Th, K and Sr), Pb, Zr and Hf elements; negative Nb, Ta and Ti anomalies; negative Nb, Ta and Ti anomalies; slightly negative to positive Eu anomalies (δEu = 0.86–1.04); high ϵ Nd(t) values of 4.6 to 8.2; and moderate (87Sr/86Sr) i ratios ((87Sr/86Sr) i = 0.70390–0.70428). Most of the basalt, basaltic andesite and andesite samples plot from the arc to N-MORB basalt fields in the Hf–Th–Nb discrimination diagrams (Fig. 11a) and in the volcanic arc basalt (VAB) and MORB fields in the Ce/Sr–Cr discrimination diagrams, suggesting that these rocks formed in a supra-subduction zone setting. All of these features indicate that the basalts, basaltic andesites and andesite rocks are mantle-derived and formed at the extensional basin in a supra-subduction zone setting.

Fig. 10. (a) Th/Yb vs Nb/Yb diagram (Pearce, Reference Pearce and Thorpe1982, Reference Pearce2008) and (b) (La/Yb)P vs (Sm/Yb)P plot (modified after K Wang et al. Reference Wang, Plank, Walker and Smith2002) for volcanic rocks from the Kalatage area of the Turpan Basin. SHO – shoshonite; CA – calc-alkaline; TH – tholeiite. All Tb/Yb and Sm/Yb values are normalized to the primitive mantle (Sun & McDonough, Reference Sun, McDonough, Sauders and Norry1989).

Fig. 11. (a) Zr–Zr/Y (Pearce & Norry, Reference Pearce and Norry1979) and (b) Hf–Th–Ta (Wood, Reference Wood1980) discriminant diagrams for volcanic rocks (fields of the Tofua Arc, Lau Basin and Mariana Trough are taken from Hawkins (Reference Hawkins, Dilek and Newcomb2003)); (c) Rb vs Y + Nb diagrams for volcanic rocks (Pearce et al. Reference Pearce, Harris and Tindle1984); (d) Nb–Y–3Ga discriminant diagrams for the subdivision of A-type granites (Eby, Reference Eby1992). Symbols used are the same as in Figure 6.

The rhyolites are highly siliceous and high in total alkali levels. In general, the rocks are variably enriched with HFSE and REE. The geochemical characteristics of rhyolites, including high SiO2, K2O + Na2O, Fe/Mg, Ga, Zr, Nb, Y and REE levels, show an affinity with A-type granites (Loiselle & Wones, Reference Loiselle and Wones1979; Whalen et al. Reference Whalen, Currie and Chappell1987). According to the geochemical subdivision of A-type granites illustrated by Eby (Reference Eby1992), including relatively high Y/Nb ratios (2.84–3.62), the rhyolites belong to the A2 subtype (Fig. 10c). In the discrimination diagrams (Fig. 11d), the rhyolite samples plot from the volcanic arc to the plate granite field, suggesting that the rhyolites formed in a supra-subduction zone setting.

The direct fractionation of mantle-derived tholeiitic magmas constitutes an important source of A-type felsic rock petrogenesis (Bonin et al. Reference Bonin, Grelou-Orsini and Vialette1978; Turner et al. Reference Turner, Foden and Morrison1992; Han et al. Reference Han, Wang, Jahn, Hong, Kagami and Sun1997; Hollings et al. Reference Hollings, Frakuck and Kissin2004; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014 c). The series of volcanic rocks in the Turpan Basin exhibit high ϵ Nd(t) values, and rhyolites present ϵ Nd(t) values of 5.1 to 7.5, suggesting that the rhyolites derived from the mantle. The relatively strong negative Eu anomaly (Eu/Eu* = 0.18–0.33) and spectacular tetrad effects observed from their REE distribution patterns suggest that extensive magmatic differentiation played an important role in magmatic processes, during which intense interactions between the highly evolved magmas and aqueous hydrothermal fluids (likely rich in F and Cl) formed typical trace elements and REE distributions (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Masuda and Shabani1992, Reference Zhao, Xiong, Han, Wang, Wang, Bao and Jahn2002; Jahn et al. Reference Jahn, Wu, Capdevila, Martineau, Zhao and Wang2001). Fractionation trends observed in the magmatic suite are also clearly indicated by the rhyolitic rocks with their striking depletions of Ba, Sr, P, Ti and Eu as shown from the spidergrams and REE patterns (Fig. 8). The rhyolites present low MgO, Cr, Ni and Co levels, consistent with the highly differentiated nature of the magmas, which can be attributed to pyroxene and amphibole fractions. Strong differences in K2O, Al2O3, Zr, Nb and Y content levels of the two groups of rhyolites also suggest that the rocks underwent varying degrees of K-feldspar and zircon fractionation.

Our studies reveal that the studied series of volcanic rocks present SiO2 content levels of 46.27 % to 83.54 % (Fig. 6), containing basalts, basaltic andesites (trachyandesites), andesites (trachyandesites) and rhyolites. Significant degrees of fractionation are recorded from the geochemistry of the volcanic rocks, including those illustrated by the binary diagrams (Fig. 7). The rocks show positive correlations between SiO2 and K2O and Rb levels and negative correlations between SiO2 and CaO, Al2O3, MgO, TiO2, P2O5, Co, Ni, V, Co and Sr levels, indicating that the volcanic rocks originate from the same source and that magmatic differentiation was central to their generation as exemplified by the fractionation of clinopyroxene, amphibole, ilmenite, apatite and plagioclase. Fractionation trends observed in the magmatic suite are also clearly indicated by variable LREE levels; slightly positive to highly negative Eu anomalies (Eu/Eu* = 0.86–1.00); and more depleted Nb, Ta, P and Ti elements originating from basalts to rhyolites observed from the samples. For example, negative Eu depletion requires magmas to undergo extensive feldspar fractionation, and a negative Ti anomaly is often related to ilmenite fractionation while a negative P anomaly is attributed to apatite separation. All of these features and relations indicate that the volcanic rocks derived from the mantle, while their parent magmas may have undergone extensive levels of magmatic fractionation, during which intense interactions between residual melts and aqueous hydrothermal fluids occurred (likely rich in F and Cl).

The basalts, basaltic andesites and andesites show relatively high ϵ Nd(t) levels, revealing that their parent magmas mainly originated from a depleted mantle. The sample presents ϵ Nd(t) values of 4.6 to 8.2 and (87Sr/86Sr) i ratios of 0.70342 to 0.70591. The basalts present the highest ϵ Nd(t) and lowest (87Sr/86Sr) i values, and the basaltic andesites present the lowest ϵ Nd(t) values while rhyolites present the highest (87Sr/86Sr) i ratios. These variations in Sr and Nd isotopes observed between the different rocks suggest that their parent magmas were partly contaminated with arc-crustal components consistent with the Shaerhu complex (Mao et al. Reference Mao2014) and with inherited zircon grains observed in the basaltic andesites.

In summary, the studied rhyolites are the product of the strong fractionation of depleted mantle-derived tholeiitic basic magma, which may serve as a mechanism of A-type granite genesis. The rocks originated from a depleted mantle and formed in a supra-subduction zone setting. These results are consistent with the fact that the Dananhu Arc was an island arc in the early Permian (Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004, Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010; Windley et al. Reference Windley, Alexeiev, Xiao, Kröner and Badarch2007).

6.b. Accretionary tectonics of the southern Altaids

Our geochronology data indicate that the basaltic andesites and rhyolites may have erupted in 286.5 ± 2.1 Ma and 275.3 ± 1.8 Ma, respectively. Our results also reveal that the rhyolites erupted after the andesites in c. 10 Ma, and finally 10 Ma volcanism occurred in the Turpan Basin from 285 Ma to 275 Ma in the early Permian.

The early Permian is the key period for understanding the welding process occurring between the Tarim Block and southern active margins of the Palaeo-Asian Continent to the north (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Shu and Sun1997; Li, Reference Li2004; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004, Reference Xiao, Han, Yuan, Chen, Sun, Lin, Li, Mao, Zhang, Sun and Li2006, Reference Xiao, Han, Yuan, Sun, Lin, Chen, Li, Li and Sun2008 a, b, Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010, Reference Xiao, Windley, Allen and Han2013; Windley et al. Reference Windley, Alexeiev, Xiao, Kröner and Badarch2007).

In the early Permian, large volumes of volcanic rocks and intrusions formed in NE Xinjiang, NW China (Fig. 1b; Table 4). For example, large volumes of mantle-derived basic–acidic volcanic rock formed in the Turpan Basin (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Shu and Sun1997; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Ma, Guo, Sun, Guo, Xu and Hu2002; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Liu, Xing, Hao, Dong and Ouyang2006; Mao, Reference Mao2014; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014 c), mantle-derived bimodal volcanism occurred from 296 Ma to 293 Ma in the southern Bogda and Haerlik Mountains (Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Liu, Xing, Hao, Dong and Ouyang2006; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Shu and Santosh2011; Shu et al. Reference Shu, Wang, Zhu, Guo, Charvet and Zhang2011), and basalt formed rocks in the Santanghu Basin (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Guo, Han and Wang2006 a; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Liu, Xing, Hao, Dong and Ouyang2006; Wang, Reference Wang2013). Early Permian alkali granitic intrusions occurred in the Balikun–Harlik, Bogda and Dananhu areas (Gu et al. Reference Gu, Hu, Chu, Yu and Xiao1999; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Han, Yuan and Sun2008; Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Sun, Wilde, Xiao, Xu, Long and Zhao2010; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Yuan, Zhang, Fan, Liu, Peng and Zhang2010). Numerous Alaskan-type mafic–ultramafic intrusions of 269–285 Ma also occurred along large strike-slip shearing faults in the East Tianshan (Table 4; Han et al. Reference Han, Song, Chen and Li2004; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004, Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Lesher, Yang, Li and Sun2004; JY Li et al. Reference Li, Song, Wang, Li, Sun and Qi2006 b; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Han, Sun, Yuan, Yan, Li, Yong and Zhang2006; Ao et al. Reference Ao, Xiao, Han, Mao and Zhang2010; Han et al. Reference Han, Xiao, Zhao, Ao, Zhang, Qu and Du2010; Qin et al. Reference Qin, Su, Sakyi, Tang, Li, Sun, Xiao and Liu2011). Finally, early Permian adakites of 274 Ma have been found in the Sanchakou and Huangshan areas (Li et al. Reference Li, Chen, Lu, Yang, Guo and Mei2004; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Wang, Xiong, Zhang, Niu, Xu Jf and Qiao2006 b; Qin et al. Reference Qin, Zhang, Ding, Xu, Tang, Xu, Ma and Li2009).

This form of magmatism is always connected to strike-slip tectonics occurring at the same time. For example, Laurent-Charvet et al. (Reference Laurent-Charvet, Shu, Ma and Lu2002, Reference Laurent-Charvet, Monie, Charvet and Shu2003) show that strike-slip shearing in the Chinese Tianshan and Altai mainly took place from 290 to 245 Ma. Other studies show that the ductile deformation of the Kangguer–Huangshan ductile zone formed from c. 260 to 247 Ma (Y Wang et al. Reference Wang, Plank, Walker and Smith2002; YT Wang et al. Reference Wang, Mao, Li and Yang2004; W Chen et al. Reference Chen, Sun, Zhang, Xiao, Wang, Jiang and Yang2005) and/or from 267 to 275 Ma (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Cluzel, Jajn, Shu, Chen, Zhai, Branquet, Barbanson and Sizaret2014).

This form of mantle-derived magmatism, which occurs along extensional basins and strike-slip faults, has been widely reported and discussed (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Sengor and Natalin1995, Reference Allen and Vimcent1997; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004, Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Cluzel, Shu, Faure, Charvet, Chen, Meddre and Jong2009; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014 c). First, volcanic rocks occur along dextral strike-slip faults and related extensive basins, examples of which include the Shaerhu Complex within a NW-trending dextral strike-slip fault of the Dannanhu Arc of the early Permian (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Shu and Santosh2011; Mao, Reference Mao2014; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014 c); basaltic rocks located along a NW-trending strike-slip fault within the Santanghu Basin (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Guo, Han and Wang2006 a); and extensional volcanic rocks positioned along NW-trending strike-slip faults of the Turpan Basin (illustrated in this work). In addition, Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Sengor and Natalin1995, Reference Allen and Vimcent1997) have reported that the studied basins are connected to strike-slip faults of the region dating to the late Permian to Triassic. Second, many alkaline intrusions and mafic–ultramafic complexes intruded along regional faults of NE Xinjiang. For example, Dajiashan alkaline granites are exposed along the Kalameili fault (Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Han, Yuan and Sun2008), mafic–ultramafic intrusions developed in the Haibaotan Area (JY Li et al. Reference Li, Song, Wang, Li, Sun and Qi2006 b), the Kalatongke mafic–ultramafic complex is positioned in the Erqis fault zone (Han et al. Reference Han, Song, Chen and Li2004), and Huangshan mafic–ultramafic belts are positioned in the Kangguer–Huangshan ductile zone (Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004; Qin et al. Reference Qin, Su, Sakyi, Tang, Li, Sun, Xiao and Liu2011). Third, many syn-kinematic intrusions formed along major shear zones of the Tianshan Belt (e.g. in the Kangguer shear zones) (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Cluzel, Shu, Faure, Charvet, Chen, Meddre and Jong2009, Reference Wang, Cluzel, Jajn, Shu, Chen, Zhai, Branquet, Barbanson and Sizaret2014; Branquet et al. Reference Branquet, Guniaux, Sizaret, Barbanson, Wang, Cluzel, Li and Delaunay2012). In summary, early Permian subduction-related magmatism was correlated both in space and time with Permian strike-slip faults and extensional structures. This geological phenomenon has been widely studied and discussed. To date, a number of geological models have been proposed, most notably the mantle plume model (Pirajno et al. Reference Pirajno, Mao, Zhang and Chai2008; Qin et al. Reference Qin, Su, Sakyi, Tang, Li, Sun, Xiao and Liu2011; Su et al. Reference Su, Qin, Sun, Tang, Sakyi, Chu, Liu and Xiao2012; Tang et al. Reference Tang, Qin, Su, Sakyi, Liu, Mao, Santosh and Ma2013), the oblique subduction and oblique collision model (Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Han, Sun, Yuan, Yan, Li, Yong and Zhang2006; Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014 c; Ao et al. Reference Ao, Xiao, Han, Mao and Zhang2010; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010), the post-collisional transtensional model (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Sengor and Natalin1995, Reference Allen and Vimcent1997; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Cluzel, Shu, Faure, Charvet, Chen, Meddre and Jong2009, Reference Wang, Cluzel, Jajn, Shu, Chen, Zhai, Branquet, Barbanson and Sizaret2014; Branquet et al. Reference Branquet, Guniaux, Sizaret, Barbanson, Wang, Cluzel, Li and Delaunay2012), the post-collisional slab break-off model (Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Sun, Wilde, Xiao, Xu, Long and Zhao2010; Song et al. Reference Song, Xie, Deng, Crawford, Zheng, Zhou, Deng, Cheng and Li2011; Deng et al. Reference Deng, Song, Hollings, Zhou, Yuan, Chen and Zhang2015; Du et al. Reference Du, Long, Yuan, Zhang, Huang, Sun and Xiao2018) and the post-collisional extension model (Han et al. Reference Han, Wang, Jahn, Hong, Kagami and Sun1997; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Yang, Qu, Du, Wang and Han2002; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Ma, Guo, Sun, Guo, Xu and Hu2002; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Lesher, Yang, Li and Sun2004; JY Li et al. Reference Li, Song, Wang, Li, Sun and Qi2006 b; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang and He2006; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Guo, Han and Wang2006 a; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Shu and Santosh2011). Combining all of the data, it can therefore be considered to represent an oblique subduction of the Palaeo-Asian Ocean north of the Tarim Block (Ao et al. Reference Ao, Xiao, Han, Mao and Zhang2010; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014 c), which may lead to transtension, tectonic extrusion and plate tearing in the East Tianshan. We conclude that early Permian magmatism was mantle-derived and formed in a forearc transtensional setting.

From the above data, other arguments and regional geological data, we propose a new tectonic scenario illustrated in Figure 12 that explains the emplacement of magmas along fault zones of different directions.

Fig. 12. Schematic tectonic diagrams illustrating the development of Permian volcanic rocks and intrusions in the East Tianshan (modified after Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014 c). (a) Tectonic cross-section of the Queershan Arc, Mazongshan–Huaniushan Arc accretionary system and Shibanshan Arc; (b) tectonic cross-section of the eastern part of the Kanggur shear zone and Dananhu–Haerlik Arc; (c) tectonic cross-section of the western part of the Kanggur shear zone, Dananhu–Haerlik Arc and Turpan Basin; (d) tectonic cross-section of the Yili – Central Tienshan Arc, Tarim Craton and Junggar Basin.

As demonstrated by Xiao et al. (Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010) and Mao et al. (Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014 c), the Palaeo-Asian Ocean and Tarim Block were obliquely subducted to the southern active margins of the Palaeo-Asian continent (Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Shu, Gao, Xiong, Wang, Guo, Li and Sun2008 b, Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014 c), which predictably led to the formation of extrusion tectonic, slab break-off (Tang et al. Reference Tang, Qin, Li, Qi, Su and Qu2011), strike-slip faults and to transtension in the forearc of the East Tianshan (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Shu and Santosh2011; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014 c).

Forearc transtension may have occurred as a result of oblique subduction in the East Tianshan, possibly with slab break-off processes (Tang et al. Reference Tang, Qin, Li, Qi, Su and Qu2011). The depleted mantle rose along the faults and spurred partial decompression melting to form volcanic rocks and intrusions along regional faults. The associated strike-slip faults cut the continental and/or arc blocks, carrying various forearc slices extruded outward (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Shu and Santosh2011; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014 c).

The described transtensional events were characterized by strike-slip faults and extensional basin formation, by the upwelling of magmas into the faults, and by the emplacement of intrusive and eruptive rocks into these basins and along deep strike-slip faults, e.g. large volumes of volcanic rocks and intrusions in the Turpan, Santanghu, Hongliuhe and Xiaoriquanzi basins and in the Haibotan–Kalatage, Kalatongke, Huangshan–Jingerquan, Lubei, Pobei–Cihai and Baishiquan mafic–ultramafic complexes (Table 4). Furthermore, N-MORB-like basalts erupted in a heavily extensional basin (e.g. the Turpan and Hongliuhe basins) (Fig. 12; Table 4). The described geological processes echo those of the Tanlu Fault in eastern China and those of the San Andreas Fault in North America. These strike-slip fault systems developed in the active continental margin, leading to the formation of continental extensions and mantle-derived magmas and even shaping the oceanic crust, e.g. the California Gulf. This system may echo the Jinsha River – Ailaoshan – Red River large strike-slip fault system extending through Yunnan Province from SW China to northern Vietnam and the Sagaing fault of SE Asia as well as large volumes of ultra-basic, basic, intermediate and felsic volcanic rocks formed along the Jinsha River – Ailaoshan – Red River strike-slip fault system of the late Oligocene to early Miocene (c. 27–22 Ma, Chung et al. Reference Chung, Lee, Lo, Wang and Genyao1997; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Yin, Harrison, Grove, Zhang and Xie2001).

6.c. Implications for Palaeo-Pacific evolution

As noted above, interactions of the Palaeo-Pacific and Palaeo-Asian Oceans are an enigmatic issue due to their controversial temporal and spatial features, spurring contrasting views (either the Pacific Ocean only affected NE Asia in the Early Mesozoic, or the Palaeo-Pacific Ocean already operated in the Palaeozoic or even earlier (see Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010, Reference Xiao, Windley, Han, Liu, Wan, Zhang, Ao, Zhang and Song2018)). The real cause of the observed divergence is the mutual translation of the Palaeo-Asian and Palaeo-Pacific Oceans in terms of temporal and spatial features.

The Palaeo-Asian Ocean constituted the main oceanic body, and its major branches extended from southern Mongolia to the north and from the Tarim and North China blocks to the south (Fig. 1). When the southern limb (southern Mongolia) of the Tuva Orocline rotated clockwise to collide with the Tarim and North China blocks, the Palaeo-Pacific Ocean closed. Therefore, the Palaeo-Asian Ocean formed part of the Palaeo-Pacific Ocean called the Panthalassic Ocean (Domeier & Torsvik, Reference Domeier and Torsvik2014; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Windley, Sun, Li, Huang, Han, Yuan, Sun and Chen2015, Reference Xiao, Windley, Han, Liu, Wan, Zhang, Ao, Zhang and Song2018), and the timing of the closure of the Palaeo-Asian Ocean is key to developing a stronger understanding of the above-described process.

Located within the southernmost Altaids, the East Tianshan records the final phase of the closure of the Palaeo-Asian Ocean (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Windley and Zhang1993, Reference Allen, Sengor and Natalin1995; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Shu and Sun1997; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Ma, Guo, Sun, Guo, Xu and Hu2002; Laurent-Charvet et al. Reference Laurent-Charvet, Monie, Charvet and Shu2003; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004, Reference Xiao, Mao, Windley, Qu, Zhang, Ao, Guo, Cleven, Lin, Shan and Li2010, Reference Xiao, Windley, Sun, Li, Huang, Han, Yuan, Sun and Chen2015, Reference Xiao, Windley, Han, Liu, Wan, Zhang, Ao, Zhang and Song2018; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Lesher, Yang, Li and Sun2004; JY Li et al. Reference Li, Song, Wang, Li, Sun and Qi2006 b; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Han, Sun, Yuan, Yan, Li, Yong and Zhang2006, Reference Mao, Xiao, Han, Yuan and Sun2008, Reference Mao, Xiao, Windley, Han, Qu, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Guo2012, Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014c; JB Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang and He2006; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Wang, Xiong, Zhang, Niu, Xu Jf and Qiao2006 b; B Wang et al. Reference Wang, Cluzel, Shu, Faure, Charvet, Chen, Meddre and Jong2009, Reference Wang, Cluzel, Jajn, Shu, Chen, Zhai, Branquet, Barbanson and Sizaret2014; Ao et al. Reference Ao, Xiao, Han, Mao and Zhang2010; Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Sun, Wilde, Xiao, Xu, Long and Zhao2010; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Shu and Santosh2011; Qin et al. Reference Qin, Su, Sakyi, Tang, Li, Sun, Xiao and Liu2011; Song et al. Reference Song, Xie, Deng, Crawford, Zheng, Zhou, Deng, Cheng and Li2011; Branquet et al. Reference Branquet, Guniaux, Sizaret, Barbanson, Wang, Cluzel, Li and Delaunay2012; Deng et al. Reference Deng, Song, Hollings, Zhou, Yuan, Chen and Zhang2015; Du et al. Reference Du, Long, Yuan, Zhang, Huang, Sun and Xiao2018). However, there has been no consensus on the closure of the Palaeo-Asian Ocean in the East Tianshan. Some researchers have argued that the closure of the Palaeo-Asian Ocean in the East Tianshan occurred in the Carboniferous (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Windley and Zhang1993, Reference Allen, Sengor and Natalin1995; Laurent-Charvet et al. Reference Laurent-Charvet, Monie, Charvet and Shu2003; JB Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang and He2006; B Wang et al. Reference Wang, Cluzel, Shu, Faure, Charvet, Chen, Meddre and Jong2009, Reference Wang, Cluzel, Jajn, Shu, Chen, Zhai, Branquet, Barbanson and Sizaret2014), while others have proposed a much later closure period occurring in the Permian or even in the Triassic (Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004, Reference Xiao, Windley, Sun, Li, Huang, Han, Yuan, Sun and Chen2015, Reference Xiao, Windley, Han, Liu, Wan, Zhang, Ao, Zhang and Song2018; Mao et al. Reference Mao, Xiao, Han, Sun, Yuan, Yan, Li, Yong and Zhang2006, Reference Mao, Xiao, Fang, Windley, Sun, Ao, Zhang and Huang2014c; Ao et al. Reference Ao, Xiao, Han, Mao and Zhang2010; Domeier & Torsvik, Reference Domeier and Torsvik2014).

The former view is based on the fact that Devonian–Carboniferous tholeiitic basalts and calc-alkaline andesites in this region have been interpreted as island arc volcanic rocks (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Shu and Sun1997; Rui et al. Reference Rui, Wang and Wang2002; Song et al. Reference Song, Li, Li, Wang and Wang2002 a; Xiao et al. Reference Xiao, Zhang, Qin, Sun and Li2004; Tang et al. Reference Tang, Gu, Zheng, Fang, Zhang, Gao, Wang, Wang and Zhang2006; Wan et al. Reference Wan, Zhang, Xu and Sun2006; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wan, Jiao and Zhang2006; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wyman, Zhao, Xu, Zheng, Xiong, Dai, Li and Chu2007). However, this verifies the fact that subduction occurred in the Carboniferous and does not serve as diagnostic evidence that subduction ended in the Carboniferous. The data presented in this paper provide solid evidence dating subduction processes later to the Permian. Therefore, the subduction of the Palaeo-Pacific Ocean may have been active in the Permian in the southern Altaids.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Journal editors, Susie Bloor and Yildirim Dilek, the journal formal reviewer Yalcin Ersoy and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments that enhanced the presentation of the manuscript. This study was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFC0601201), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41888101), the Strategic Priority Research Program (B) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB18020203), the Chinese Geological Survey Project (DD20190815), the Chinese Ministry of Land and Resources for the Public Welfare Industry Research (201411026-1), the Chinese State 305 Project (2011BAB06B04-03) and the Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, CAS (QYZDJ-SSW-SYS012). This is a contribution to IGCP 622.