1. Introduction

Geographical indications (GIs), a form of intellectual property under the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement), have been the subject of a long and spirited debate on the international stage.Footnote 1 One of the most controversial issues concerns the imbalance in GI protection created by Articles 22 and 23 of the TRIPS Agreement.Footnote 2 Article 22 prohibits using a GI that would confuse consumers as to the true geographical origin of a product. By contrast, Article 23 provides a higher level of protection to wines and spirits by preventing the use of a GI on products not originating in the place indicated by the GI even if such use would not result in consumer confusion or constitute unfair competition (often referred to as ‘absolute protection’).Footnote 3 The outcome of the imbalance is that the use of the ‘Cognac style’ for a brandy produced in New Zealand is not permissible,Footnote 4 whereas using ‘Roquefort style’ for a cheese made in south California is permissible.Footnote 5 ‘Old World’ countries, represented by the European Union (EU) and its Member States, advocate the extension of the high-level protection currently only available for wines and spirits to all GI products. However, ‘New World’ countries, headed by the United States (US), strongly oppose the extension proposal.Footnote 6 In the face of the deadlock in the WTO Doha Development Round of negotiations, the debate between ‘Old World’ and ‘New World’ countries does not end but enters into free trade agreement negotiations.Footnote 7 It is even more heated as the EU and US compete to pursue their goals of enhancing or restricting GI protection via bilateral negotiations with other WTO Members.Footnote 8

To understand and resolve the debate, the existing literature traces the cultural and legal differences between the two worlds, particularly the domestic legislative traditions of the EU and US. Much attention has focused on the protection mechanisms (sui generis or trademark laws) and general conditions for infringement.Footnote 9 In this context, it is increasingly acknowledged that the global disputation revolves around the concept of terroir as a basis for GI protection.Footnote 10

However, the differences in the defences to, exclusions from, and limitations on the infringement of GIs are largely unexplored. Like other forms of intellectual property (e.g., copyrights, patents, trademarks), GI protection is determined not only by the conditions for infringement but also by the defences and exceptions, namely, matters that lead to the use of a GI, which would otherwise constitute an infringement, being excluded from the scope of infringement. The latter receives less attention but is nevertheless equally important. Therefore, research is needed to analyse whether, and why or why not, defences and exceptions such as ‘fair use’ are provided under WTO Members’ domestic laws on GI protection.

The terminology ‘fair use’ is used in the TRIPS Agreement to refer to the fair use of descriptive terms that serve as an exception to rights conferred by a trademark.Footnote 11 Curiously, although GIs are by definition composed of geographically descriptive terms,Footnote 12 the TRIPS Agreement does not mention whether the certain usage of those descriptive words can be considered to be ‘fair’ and thus constitute an exception to the rights conferred by a GI (this article terms such usage as the ‘fair use of GIs’). WTO Members are divided on whether to allow third parties other than authorized users to use GIs or descriptive terms that form part of GIs to accurately describe third parties’ products or identify authorized users’ products.

Some divergent practices have already been noted in the debate on the protection level of GIs. For instance, the use of GIs on products not originating from the indicated regions (e.g., ‘Roquefort-style cheese’), as opposed by the EU, may qualify as descriptive or nominative fair use depending on the circumstances and therefore be permitted under US law.Footnote 13 A divergence in other aspects has started to emerge with the recent decisions of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) and national courts that have refused to exclude from the scope of infringement the use of GIs on products indeed originating from the indicated regions.Footnote 14

This article joins the GI protection debate by exploring the opposite direction: the fair use of GIs. It first reveals the divergence in approaches on the fair use of GIs by comparing EU and US legislation before investigating the root causes behind different national practices. The final section draws conclusions and provides recommendations. The results show that the contrasting approaches to the fair use of GIs derive from the differences in balancing conflicting interests and in policy goals, which, in turn, arise from a fundamentally different outlook on the freedom of competition (or its antithesis, protectionism), brand owners’ investment, and, consequently, the concept of fairness. Given that the fair use exception is one factor that determines the protection level, the findings of the research challenge the conventional wisdom that the disagreement over terroir essentially accounts for the disagreement between the EU and US over the level of protection for GIs.

2. Divergent National Approaches to the Fair Use of GIs

This section discusses the differences in the treatment of the fair use of GIs by comparing EU and US approaches. French laws and practices are referred to where helpful to analyse the EU's approach. French legislation on Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) is one of the main inspirationsFootnote 15 for creating EU-wide systems of GI protection.Footnote 16 Moreover, although the EU GI Regulations grant the European Commission exclusive power to afford protection to GIs,Footnote 17 EU Member States are not precluded from adopting national provisions that are more detailed to ensure the effectiveness of EU-level provisions.Footnote 18 Therefore, where EU-level rules on fair use are not sufficiently specificFootnote 19 or the EU GI Regulations provide flexibility for Member States to regulate fair use,Footnote 20 French laws and practices may serve as a lens through which to examine the EU's approach and its underlying causes.Footnote 21

2.1 Use for Describing Comparable Products Not Originating from the Indicated Area

When some features of a GI product are imitated or copied by producers outside the region indicated by the GI, should those producers be prevented from using the GI to tell consumers that their products have similar characteristics when they add the true origin of the products (e.g., ‘Spanish Champagne’)Footnote 22 or a corrective expression (e.g., ‘Roquefort style’) to prevent consumer confusion? This question has been the focus of debate in international negotiations.Footnote 23 In our analysis, it can be put another way: can such use be considered to be ‘fair’?

As is well known, the EU GI Regulations stipulate that GIs should be protected against ‘any misuse, imitation or evocation’, even if the true location of origin is made clear or the GI is accompanied by corrective terms such as ‘kind’, ‘type’, ‘imitation’, and the like. This prohibition is traditionally justified by the French idea of terroir. The word terroir is historically linked to the physical features of a place.Footnote 24 It has gradually evolved into a ‘dual concept’Footnote 25 including, in addition to natural conditions, human contributions and, more precisely, ‘a collective knowledge of production based on a system of interactions between a physical and a biological environment’.Footnote 26 Despite variations between understandings, the terroir idea believes that a special connection exists between the quality of products and their geographical origin.Footnote 27 It has been argued as a justification for a high level of protection that producers from other regions are precluded from using a GI because they cannot possibly imitate the features of GI products that are uniquely causally linked to their place of origin.Footnote 28

Nonetheless, what if products produced elsewhere have successfully imitated or even reproduced the product characteristics? Can information on similar or equivalent flavours, smells, and other attributes be conveyed to consumers by the fair use of the GI? This hypothesis is not impossible, especially given that European legislators have added the protected geographical indication (PGI) category to the proposal simply to protect the protected designation of origin (PDO) category.Footnote 29 One major difference that separates the two categories is that reputation alone – based solely on duplicable human factors (i.e., the production process) – satisfies the PGI registration requirement.Footnote 30 Therefore, the hypothesis cannot be ruled out that products not originating from the area indicated by a GI have undergone the same production process and thus possess the same characteristics as those originating therein. However, since the legislators have not created a fair use exception to exclude the products reproduced elsewhere from the scope of infringement, the use of a GI on those products is infringing use rather than fair use. Thus, the PGI ‘Bayerisches Bier’ is not subject to fair use or other legal exemptions despite the spread of the old Bavarian bottom fermentation brewing method to other regions.Footnote 31

The absence of fair use exceptions is not an oversight, but a deliberate decision by European authorities, which can be reflected in their contrasting attitudes towards the use of indications of source. The latter indicates the geographical region in which the product originates but does not guarantee to consumers any particular quality or characteristic of the identified products.Footnote 32 In its notice released in 2020, the European Commission implied that an indication of a geographical place in connection with statements such as ‘kind’, ‘type’, ‘style’, ‘recipe’, ‘inspired by’, and ‘à la’ can be used to describe products not originating from the indicated place as long as such use does not mislead the consumer about those products’ origin. It pointed out that the use could be justified ‘if the food in question possesses specific characteristics or nature, or has undergone a certain production process which determines the claimed link to the geographical place indicated on the label’.Footnote 33 The imbalance of elaborating on the situation under which indications of source can be used on products with another place of provenance, while denying all access to GIs in a similar situation illustrates the EU's unwillingness to exclude this situation from the protection scope of GIs.

By contrast, the US has developed fair use as a limitation on trademark rights, which is applicable to GIs registered as collective or certification marks. Fair use can be subdivided into descriptive and nominative fair use. Descriptive fair use applies in instances in which the trademark is used to describe the defendant's products,Footnote 34 whereas nominative fair use applies where the defendant uses the trademark to describe the plaintiff's products.Footnote 35 The use of GIs registered as trademarks to describe products originating in another place may fall into one of the two categories depending on a broad or narrow reading of each category's scope.Footnote 36 It follows from the US court's established case law that a defendant can use the words ‘style’, ‘flavour’, ‘smell’, ‘like’, and similar along with the plaintiff's trademark to indicate that the defendant's goods are of the same style, type, and other characteristics. The use of ‘WACO style’,Footnote 37 ‘SWEET-TART flavour’,Footnote 38 ‘LOVE POTION fragrance’,Footnote 39 and ‘CHANEL-smell-alike’Footnote 40 was found to be fair use. Since trademark law is applicable, unless otherwise expressly provided, to all types of trademarks, including GIs registered as collective or certification marks, the use of statements such as ‘style’ and ‘like’ along with a mark composed of a GI may also be considered to be fair use.

Admittedly, the fair use defence under US trademark law is conditional upon certain conditions being satisfied, such as ‘use otherwise than as a mark’,Footnote 41 the user's intent,Footnote 42 the degree of consumer confusion,Footnote 43 and truthfulness.Footnote 44 However, considering the absence of fair use exceptions in EU GI law, the gap between EU and US approaches is evident.

2.2 Use for Describing Comparable Products Indeed Originating from the Indicated Area

Even assuming that prohibiting the fair use of a GI on products originating elsewhere could be justified by the terroir idea, namely, that the uniqueness of the combination of natural and human factors in a locality gives to products unique qualities that cannot be exactly duplicated anywhere in the world, the same justification cannot be employed to refuse the fair use of GIs on products that do originate from the same area as the GI products.

It is not disputed that authorized users enjoy the right to use a GI, whether registered as trademarks or under sui generis GI law. However, if a producer has not obtained the authorization, either because its products do not comply with the quality requirements contained in the product specificationFootnote 45 or because it voluntarily chooses not to join the GI quality scheme despite full compliance with the product specification,Footnote 46 is it allowed to use the GI or its main part to describe its products that genuinely originate from the locality indicated by the GI?

The EU applies a complete ban. Before the case of ‘Queso Manchego’, it was unclear whether the use, imitation, or evocation of a GI by a producer established in the geographical area corresponding to the GI but whose products are not protected by the GI was excluded from the application of the infringement provisions. The Supreme Court of Spain referred this question to the CJEU, which was answered in the negative for two reasons. First, the wording of the EU GI Regulations does not provide a ‘fair use’ exception for a producer established inside the protected area. Second, legal exemptions, even if they were provided, would only allow a producer to take an unfair advantage of the reputation of the GI.Footnote 47 Thus, such use has been labelled as an unfair rather than fair. The strict approach was adopted in similar cases in which the use of the terms ‘Morbier’,Footnote 48 ‘Culatello di Parma’,Footnote 49 and ‘Pecorino Sardo’Footnote 50 by a producer established in the area indicated by the GI in question was not exempted from infringement.

French national GI legislation contains more detailed provisions on the use of GIs to indicate the origin of non-GI products. Article L. 643-2 of the French Rural Code is designed specifically to reconcile GI protection with the need to indicate geographical provenances. The first two paragraphs of the article provide:

The use of an indication of origin or provenance must not be liable to mislead the consumer as to the characteristics of the product, to divert or weaken the reputation of a name recognized as an appellation of origin or registered, as a geographical indication, or as a guaranteed traditional speciality, or, more generally, to undermine, in particular by the abusive use of a geographical reference in a trade name, the specific nature of the protection reserved for appellations of origin, geographical indications, and traditional specialities guaranteed.

For products without protected designation of origin or geographical indication, the use of an indication of origin or provenance must be accompanied by information on the nature of the operation linked to this indication, in all cases where this is necessary for the correct information of the consumer.Footnote 51

As noted in the second paragraph above, even when a place name has been registered as a GI,Footnote 52 it may still be used as a simple indication of provenance on products not authorized to bear the GI. However, such use as an indication of provenance differs from use as a GI. Information on the nature of the operation (one of the stages of obtaining the product) linked to the geographical reference must be indicated.Footnote 53 For example, ‘Chicken from Paris’ should instead be called ‘Chicken Plucked in Paris’ and ‘Cider from Mont-Saint-Michel’ should be called ‘Cider Pressed in Mont-Saint-Michel’.Footnote 54 In the same vein, ‘Camembert Made in Normandy’ does not contradict the terms of the second paragraph.

Nevertheless, such use as an indication of provenance is subject to the rigorous requirements laid down by the first paragraph of Article L. 643-2. This rigour can be illustrated by the restrictions on the use of the statement ‘Camembert Made in Normandy’ as an indication of provenance. ‘Camembert Made in Normandy’ was used as an indication of provenance before the protection of the GI ‘Camembert from Normandy’ in 1983. Since then, the regulatory provisions have allowed cheeses authorized to bear the GI to coexist in the market with cheeses bearing ‘Made in Normandy’, which cannot benefit from the GI.Footnote 55 In 2008, the special decree providing for such coexistence was repealed, and the use of the label ‘Made in Normandy’ must now be assessed according to the general rules, particularly Article L. 643-2 of the French Rural Code (formerly Article L. 115-26-4 of the Consumer Code).Footnote 56 To meet the conditions laid down by the general rules, the Syndicat Normand des Fabricants de Camembert, which brings together producers of Camembert produced in Normandy but not covered by the GI, had set strict labelling rules. First, the indications ‘Camembert’ and ‘Made in Normandy’ should be completely disconnected. Second, the size of the indication ‘Camembert’ must not exceed two-thirds of the most important mention (e.g., the trademark) and must not exceed 8 mm in height. Third, the words ‘Made in Normandy’ must be written with the same characters; these characters must not exceed half of the characters of the indication ‘Camembert’.Footnote 57

However, once considered to be sufficient to avoid consumer confusion,Footnote 58 the strict labelling rules now face being embellished by new restrictions. The judgement of 24 December 2020 of the French Council of State upheld the opinion of the French competition authority (DGCCRF) that ‘the highlighting of the words “Made in Normandy” is not possible on a cheese that does not meet the specifications of the GI’.Footnote 59 The prohibition of prominent use was justified on the grounds that such use would be misleading and thus contrary to the requirements of Article L. 643-2.Footnote 60 However, prominent use does not necessarily confuse consumers, especially when precautions have already been taken (e.g., providing a prominent disclaimer emphasizing the true identity of the product).Footnote 61 The literal meaning of Article L. 643-2 forbids confusion as to the product's characteristics, while the application of Article L. 643-2 appears to forbid prominent use without testing the likelihood of confusion,Footnote 62 which has further increased the restrictions on use as an indication of provenance. The new restrictions indicate a move towards the approach taken by the CJEU in the ‘Queso Manchego’ case.

Under US trademark law, a producer without a license using a trademark composed of a GI to indicate the true place of origin may be considered to be fair use.Footnote 63 The conditions for such use are more relaxed than those in France. By way of an illustration, prominent use per se is not prohibited by US trademark law, although it is one of the factors taken into consideration when determining ‘use otherwise than as a trademark’.Footnote 64 Likewise, the likelihood of confusion can coexist with fair use under US law,Footnote 65 whereas finding that confusion is likely precludes any unauthorized use under French law.Footnote 66

2.3 Use of the Defendant's Own Name or Address

When a person's name or address contains a GI, is the GI infringed by using that name or address? Once again, the EU and US are divided on this issue. The EU encourages its Members to limit or completely ban the use of a person's name or address. It offers two options. First, the person's name or address can be allowed to appear on the label, but the characters should not exceed more than half the size of those used for the GI. Second, the person's name or address should be replaced by a code.Footnote 67 France has chosen the second option.Footnote 68 Therefore, the statement ‘Bottled by the SCA La Douzaine at Pomerol–France’ should be replaced by ‘Bottled by the SCA La Douzaine at F–33500’. The statement ‘Bottled by EMB XX XXX–France’ should be used if the person's name consists of a GI.Footnote 69

It is worth noting that France had traditionally reserved the right to use a person's name or address. Article 12 of the Decree of 1921 specified that when a place name constitutes an appellation of origin, the owners, winegrowers, and traders who reside in this locality can use the name to indicate the location if it is preceded by the words ‘owner at’, ‘winegrower at’, ‘merchant at’, or ‘trader at’ and followed by an indication of the département (county) name.Footnote 70 However, this tradition of recognizing the right to use one's name or tell one's address has disappeared as the protection of GIs has increased.

On the contrary, US trademark law recognizes the right to disclose geographical origin as well as use one's name by establishing fair use defences.Footnote 71 Anyone located in a place has the right to use the place name to tell purchasers of its location and anyone has the right to use its own name in business, even if the same or a similar name has been used or registered as a trademark by others. Such fair use defences are analogous to the fair use defence of the right to use a descriptive term only to describe products.Footnote 72

2.4 Use in Comparative Advertising

Can products without a GI be compared with GI products in advertising? Can products be presented as imitations or replicas of products bearing a GI in comparative advertising?

As for the first issue, the EU does not prohibit but restricts such a comparison. Directive 2006/114 on misleading and comparative advertising sets out the conditions that must be met if comparative advertising is to be permitted. As one of the conditions, Article 4(e) requires, for products with a GI, that comparative advertising ‘relates in each case to products with the same designation’. The CJEU narrowly interprets Article 4(e) as meaning that any comparison between products without a GI and products with a GI is ‘not impermissible’.Footnote 73 In other words, under Article 4(3), comparisons between products with different GIs are unlawful (e.g., a comparison between the ‘Gran Padano’ and ‘Parmigiano Reggiano’ cheeses).Footnote 74 By contrast, comparisons between products with a GI and products without a GI may be permitted provided that such comparisons would not unfairly take advantage of the reputation of the GI (e.g., a comparison between the ‘Gran Padano’ cheese and a cheese without a GI).Footnote 75

France adopts a stricter approach. Article L. 122-3 of the Consumer Code provides that ‘concerning products with PDO or PGI, comparison is only allowed between products each with the same designation or the same indication’. This provision has been interpreted as meaning an absolute ban on comparing products with and without a GI status.Footnote 76 However, in light of the CJEU's interpretation of Article 4(e) of Directive 2006/114, there is some doubt about keeping this stricter approach.

Such a comparison is permitted under US trademark law under conditions different from those in the EU. The truthful, non-misleading use of a GI in comparative advertising is not considered to be a trademark infringement under US law. In other words, the comparison must be truthful and unlikely to convey a message of a connection or affiliation with the trademark owner;Footnote 77 however, it does not matter whether the comparison takes advantage of the trademark's reputation.

While the EU and US share some similarities on the first issue, they have a marked difference on the second. The EU Directive on comparative advertising prohibits an advertiser from stating that its product or service constitutes an imitation or replica of the product or service covered by the trademark or trade name,Footnote 78 although copying the characteristics of the latter product is allowed. In other words, one can copy a competitor's products but cannot tell consumers that its products have the same characteristics as a result of such copying. Advocate General Mengozzi further clarified in L'Oréal v Bellure that formulas such as ‘type’ and ‘style’ appended to a trademark when describing the advertiser's product can communicate the idea of copying (imitation or replica).Footnote 79 Therefore, it can be inferred that statements such as ‘Roquefort style’ should be banned in comparative advertising – even without resorting to the protection afforded by the sui generis GI Regulations. On the contrary, ‘Roquefort style’ is a legitimate comparative advertisement in the US where imitators can use a GI to tell consumers what has been imitated or copied.Footnote 80

2.5 Use of Generic Terms

It is well established in the TRIPS Agreement and WTO Members’ domestic GI legislation that generic terms alone are neither registrable nor protectable.Footnote 81 However, a composite of a generic name and other elements may be protected as a GI or trademark containing a GI if the composite as a whole is registrable or protectable.Footnote 82 The question as to whether the use of a generic component constitutes infringement has attracted attention in EU trade negotiations.Footnote 83 In our analysis, the question is explored from the opposite direction: Does the use of a generic component constitute fair use and should it be excluded from the scope of infringement? Again, the opinions are divided.

Under the EU GI Regulations, the use of a generic component is not entirely excluded from infringement. Admittedly, it has been consistently held by the CJEU that GI protection is not extended to the constituent part that is a generic or common term.Footnote 84 However, the wording of the EU GI Regulations grants only limited exceptions for the use of generic components. The second subparagraph of Article 13(1) of Regulation 1151/2012 provides that ‘the use of that generic name on the appropriate agricultural product or foodstuff shall not be considered to be contrary to points (a) or (b) in the first subparagraph’, whereas the first subparagraph contains four points. Points (a) and (b) refer to any direct or indirect commercial use of a name registered in respect of products not covered by the registration and to their misuse, imitation, or evocation. Points (c) and (d) prohibit ‘any other false or misleading indication’ and ‘any other practice liable to mislead the consumer’. The scope of protection provided by points (c) and (d) cannot be overlooked since they have been interpreted increasingly broadly by the CJEU. In Morbier, the CJEU construed the words ‘any other practice’ broadly enough that one can infringe on rights granted to a GI even without using or evoking the GI.Footnote 85 Hence, these two points can now apply to the reproduction of the shape or appearance of a product covered by a registered name.Footnote 86

However, using a generic name is not exempted from GI protection by points (c) and (d). One can imagine that such use may be considered to be contrary to point (c) or (d) and thus prohibited. This assumption is not impossible. The use of the generic name, in combination with the packaging or appearance of a product, may cause confusion as to the true origin of the product. For instance, if ‘Swiss Army knife’ is found to be generic, the use of ‘Swiss Army knife’ together with the word ‘original’ and a red handle may still confuse the defendant's knives with the pocketknives from Switzerland.Footnote 87 Thus, points (c) and (d) can be relied on for restricting how a new competitor can use the generic name of the product.

On the contrary, US trademark law offers no remedies for the use of generic names, even if such use would be categorized as abusive.Footnote 88 When a composite mark that comprises a generic term and other features is registered as a trademark, the generic term remains free for all competitors to use.Footnote 89 A generic term that forms part of a registrable composite mark must be disclaimed at the request of an Examining Attorney.Footnote 90 Failure to provide the required disclaimer constitutes a ground for refusing registration.Footnote 91 The purpose of the disclaimer is to prevent creating a false impression that the registrant owns exclusive rights to the generic name in isolation.Footnote 92 Even if the disclaimer is not required at the time of registration or part of the trademark becomes a generic name thereafter, the registrant still does not have a monopoly right over the generic name.Footnote 93

Besides the differences in granting exclusive rights to generic names, there is an even sharper divergence in approaches to the assessment of generic status, which has become a contentious issue in bilateral and multilateral trade negotiationsFootnote 94 such as within the context of two mega trade deals: the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)Footnote 95 and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)Footnote 96. The disagreement between the EU and the US is well known. By way of an illustration, registered names ‘shall not become generic’ under EU GI law,Footnote 97 whereas they may become generic over time and subject to cancellation on that basis under US trademark law.Footnote 98 Another illustration is the different standards used for determining the generic status. The EU employs a higher threshold by providing that generic status is achieved ‘only when there is in the relevant territory no significant part of the public concerned that still considers the indication as a geographical indication’.Footnote 99 Thus, a term is not placed in the ‘generic term’ category as long as a significant minority of the relevant public regard it as a GI (even though the majority of consumers regard it as a generic name).Footnote 100 By contrast, the US's test is the ‘primary significance’ of the term: if the majority of consumers regard the term as a generic name, it will lose protection as a trademark.Footnote 101

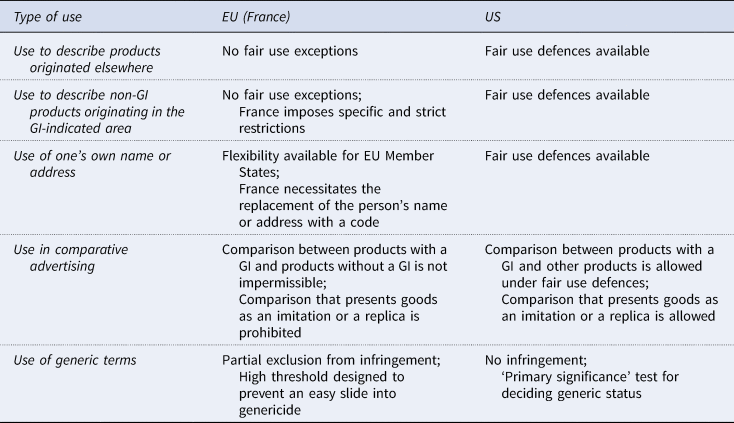

To conclude, this section reveals the contrasting approaches to the fair use of GIs, which are summarized in Table 1. The EU's approach is characterized by a strict restriction on the use of GIs by unauthorized producers and reluctance to create fair use exceptions. By contrast, the US, which ensures GI protection through the enforcement of trademark law, allows for a more relaxed restriction.

Table 1. Fair use exceptions in the EU (France) and the US

Furthermore, it can be observed that using a GI in a delocalized manner (e.g., ‘Roquefort-style cheese’), which the EU and other ‘Old World’ countries wish to prohibit through trade negotiations, does not constitute fair use under EU law but may qualify as fair use under US law. Therefore, the obstacles to achieving international consensus on the protection level may be explored by asking what causes the divergent national practices of fair use exceptions. Finally, even if all countries adopted the same infringement test (either the likelihood of confusion test embedded in Article 22 of the TRIPS Agreement or the truthfulness test in Article 23), the ultimate scope of protection would still vary due to the varying rules on fair use exceptions. To resolve the debate on the protection level, we need to determine whether the difference in fair use exceptions can be readily harmonized or is deeply rooted.

3. Root Causes Behind the Divergent Approaches

The differences in fair use exceptions are deeply rooted, which can be explored through three interrelated perspectives: the balance of interests, policy goals, and understanding of what is ‘fair’.

3.1 Tipped Balance of Interests

3.1.1 Major Interests Involved in the Balance

As will subsequently be shown, legislators and judges frequently consider six conflicting interests when deciding whether to prohibit an unauthorized party from using a GI or permit fair use. First, authorized GI users and management groups have an interest in preserving the distinctiveness of GIs and preventing a competitor from trading upon their reputation. Second, the consumer has an interest in identifying the geographical source of products and not being deceived about their provenance, characteristics, or true identity. Third, the public has an interest in encouraging the production of quality goods. Producers will continue producing quality products only when they are fairly rewarded. Fourth, those producers not authorized to use the GIs have an interest in enjoying freedom of expression when describing their products accurately. Fifth, the consumer has an interest in accessing accurate information on cheaper substitutes to enable them to make informed decisions. Sixth, the public has an interest in not creating monopolies or barriers to competition by removing place names, product features, and other competitive tools from the public domain.

The first and fourth interests are the interests of producers – the former for authorized producers and the latter for unauthorized producers. The second and fifth interests are the interests of consumers – the former for consumers looking for authentic goods and the latter for those searching for substitutes. The third and sixth interests concern the interests of the general public – the former derived from creating incentives and the latter derived from removing barriers. Conflicts exist not only within pairs but also between pairs. Although fair use exceptions aim to strike a balance between these six competing interests, different countries may tip the balance in favour of different interests. Placing more weight on the first three interests strengthens GI protection and narrows the scope of fair use, whereas attaching more weight to the latter three tends to leave more space for fair use exceptions.

3.1.2 Balance Tilted against Fair Use

On the one hand, the heavy emphasis on the first three interests has led the EU to prohibit certain acts and refuse to create fair use exceptions. The first interest, namely, the interest of authorized GI users in preserving the distinctiveness and reputation of GIs, is the core interest that the EU GI Regulations aim to protect. Specifically, the prohibition of any use of a GI for a product not originating from the indicated place is intended to preserve the distinctiveness of the GI.Footnote 102 Even accompanied by delocalizing terms such as ‘kind’ and ‘type’, such use is perceived as potentially causing the GI to lose its essential function of distinguishing ‘authentic’ GI products from similar products produced elsewhere.Footnote 103 The concern for the first interest has also led the EU to refuse to exclude products that indeed originate in the indicated area from the scope of infringement. Such an exclusion is deemed to allow unauthorized users to take unfair advantage of the reputation of the GI.Footnote 104 Although France allows producers established in the geographical area whose name is part of a GI to use the place name to indicate the provenance of products, such use is subject to the condition that it does not divert or weaken the reputation of that name.Footnote 105 In the same vein, the use of a GI to promote a product without the GI in comparative advertising is allowed only if such use does not take unfair advantage of the GI.Footnote 106 The producer's name or address that contains a GI should be replaced by a code, which again aims to prevent the indication of the producer from damaging the distinctiveness and reputation of the GI.Footnote 107

The concern for the second interest, namely, the interest of consumers in obtaining credible information, is another reason for the EU's reluctance to grant fair use exceptions. Providing consumers with clear information on the origin and attributes of products is a specific protection objective pursued by the EU GI Regulations.Footnote 108 To further guarantee this objective, the CJEU held that evoking a GI through the use of figurative figures should be prohibited and the ban applies equally to products originating from the area corresponding to the GI.Footnote 109 France permits the use of a GI to indicate the origin of products not authorized to bear the GI provided that, among other conditions, consumers are not misled about those products’ characteristics.Footnote 110 The use of a GI on products that originate from the region indicated by the GI but are not protected by the GI is often considered in French case law as misleading.Footnote 111 For instance, the terms ‘Vieux Cahors’,Footnote 112 ‘Gruyère fabriqué en Franche-Comté’,Footnote 113 ‘Cru du Fort Médoc’,Footnote 114 and ‘Chasse du Pape’Footnote 115 have been judged as misleading consumers into believing that an ordinary product is an AOC product whose geographical provenance is the same but whose quality differs. Indications of provenance are prohibited from leading consumers to attribute to the product concerned organoleptic qualities that it does not necessarily have.Footnote 116

Even if the quality is the same and consumers are thus not deceived about that particular attribute, the use of a GI on unauthorized products is still not considered to be fair use because of the concern for the third interest: the public's interest in enhancing the quality of products.Footnote 117 As recognized in the preambles to the EU GI Regulations,Footnote 118 consumers have increasing expectations of quality. and producers can only continue to produce quality products if they are rewarded fairly for their effort. The CJEU has consistently stated that EU GI laws embody not only the objective of protecting the interests of consumers who should not be deceived, but also the objective of securing higher incomes for economic operators who have made a genuine effort and bear higher costs to guarantee or improve the quality of products that lawfully bear GIs.Footnote 119 Thus, where consumers are not misled because the defendant's products indeed have the same geographical origin and quality, the absence of consumer confusion does not preclude a finding of infringement or support a finding of fair use.Footnote 120 The assumption is that when consumers are offered under the same denomination some products that are subject to the control and guarantee of quality and others devoid of any control or guarantee, even if they cannot be confused, the effect of the guarantee of quality will be adversely affected.Footnote 121 Consequently, the interest in encouraging the continuity of guaranteeing or enhancing quality would be reduced.

On the other hand, the EU's emphasis on the first three interests is accompanied by its neglect of the latter three interests. European authorities are not unaware of the fourth interest, namely, the interest of producers established in the area corresponding to a GI but not authorized to use it. In drafting the original text of Article L. 643-2 of the Rural Code, which governs the conflict between indications of origin and GIs, French legislators confirmed that the use of a geographical name without any technical constraints or control (authorization) constitutes a right.Footnote 122 When the Agricultural Orientation Law of 1999 modified the original text, legislators reaffirmed that a producer in a given region has the right to use the name of that region to communicate the geographical origin of its products accurately.Footnote 123 However, the application of Article L. 643-2 emphasizes restricting the use of place names rather than defending the right to indicate provenance by referring to those names.Footnote 124 Now, the right to use as an indication of provenance is confined to ‘non-prominent use’. An early example is affixing the words ‘Reblochon’ and ‘Tome de Savoy’ prominently in large characters to catch the consumer's eye, which has been found to infringe on GIs.Footnote 125 The recent decision by the French State of Council supported the ban on prominently displaying the name ‘Camembert made in Normandy’ on cheeses that do not comply with the requirement of the GI ‘Camembert de Normandy’.Footnote 126 French scholar Joanna Schmidt-Szalewski noted the strict nature of the conditions for using indications of provenance when commenting on the case of ‘Fleurs des Vosges’.Footnote 127 Schmidt-Szalewski suggested that a producer not authorized to use the GI should designate its products under a trademark rather than under an indication of provenance.Footnote 128 Such producers are advised to replace references to their products’ geographical origin with references to other qualities.Footnote 129 Schmidt-Szalewski's suggestion becomes an actual obligation for indications of producers’ name or address, which has to be replaced with a code if it contains a GI.Footnote 130 The interest in preventing damage to GIs appears to prevail over the interest in indicating products’ provenance and producers’ name or address.

There is also a continuing disregard for the fifth interest, namely, consumers’ interest in receiving information about competing products and cheaper substitutes. The prohibition of using a GI in a non-misleading, delocalized manner (such as ‘X type’) poses a danger for efficient communication to consumers.Footnote 131 Since the GI and quality or characteristics of the products covered by it are closely linked,Footnote 132 phrases such as ‘X type’ used to market products with similar qualities or characteristics are deemed more efficient at conveying quality information to consumers, unless the products lawfully bearing ‘X’ have truly unique qualities that cannot be imitated.Footnote 133 The latter situation does not occur in all cases, especially for the PGI category, whose registration does not require a uniqueness of the objective qualities and can rather be based on subjective reputation only.Footnote 134 Consumer knowledge reduces without using such ‘informative’ phrases. Likewise, the prohibition of presenting products as imitations or replicas restrains producers from telling consumers what has been copied or imitated.Footnote 135 In addition, the prohibition laid down by French law on advertising that compares products with a GI with products without a GI appears to disregard the interest of consumers in having effective comparative advertising. Without advertising that objectively highlights the differences between products, consumers cannot make an informed choice between ‘authentic’ quality products and alternatives.

Lastly, the sixth interest, namely, the interest in not creating monopolies or barriers to competition, is given insufficient importance. The alarming tendency of removing place names, product features, and other competitive tools from general use has come to light. Early in Windsurfing Chiemsee, the CJEU underlined that because place names may influence consumer tastes in various ways, it is in the public interest that they remain available to competitors equally and cannot be monopolized.Footnote 136 In discussing the proposal for the Agricultural Orientation Law of 1999, French legislators pointed out the danger associated with removing geographical names from competitors’ use: it distorts competition because it puts producers prohibited from using the place name at a competitive disadvantage when other producers can use the name on their labelling or in their mark.Footnote 137 Nevertheless, the implementation of European GI laws is taking place names away from competitors for the benefit of authorized GI users. The recent decision by the French Council of State may have the effect of depriving the right to use the place name ‘Normandy’. It held that manufacturers of Camembert cheese not authorized to use the GI may still associate their products with an indication of geographical origin ‘as long as it does not mention Normandy’.Footnote 138 This opinion reinforced the approach adopted in the case of ‘Gruyère fabriqué en Franche-Comté’ in which the defendant additionally invoked the obligation to respect Article 9 of the Decree of 1988, which required the compulsory indication of the region of manufacture, to justify the use of the place name ‘Franche-Comté’ on its packaging. The French Supreme Court did not accept the justification, holding that the name of the département (county) ‘Doubs’ could have been added to the labelling instead of ‘Franche-Comté’ (Franche-Comté is a historical region composed of the modern départements Doubs, Jura, and so onFootnote 139). These decisions suggest a removal of the valuable place names (e.g., ‘Franche-Comté’, ‘Normandy’) by defendants and thus a monopolization of those names that are otherwise a ‘common thing’ or belong to the public domain.Footnote 140 Furthermore, desirable public domain features of products are now subject to the monopolies granted by EU GI law. Although the wording of the provisions on GI protection concerns the registered names rather than the products covered by the names,Footnote 141 with the recent decision in Morbier, the reproduction of the shape or appearance of a product covered by a registered name could constitute an infringement.Footnote 142 The final illustration of the EU's low priority for the sixth interest concerns the partial exclusion of the use of generic terms from infringement.Footnote 143 Competitors may be restricted in the free use of generic terms if consumer confusion would likely arise.Footnote 144 It appears that when consumers’ interest in not being deceived is weighed against the public interest in assuring generic terms in the public domain, the EU tips the balance in favour of the former.

3.1.3 Balance Tilted in Favour of Fair Use

Contrary to the EU, the US leans towards the latter three interests, allowing what would be considered to be infringement in the EU to constitute fair use. US courts have a tradition of regarding the right to do business under one's personal name as an absolute or ‘sacred’ right.Footnote 145 Similarly, early decisions raised the right to inform consumers of a producer's location to great heights.Footnote 146 Although later decisions limited those rights, all parties still enjoy them as long as reasonable precautions are taken in the manner of use to avoid consumer confusion.Footnote 147

The US ensures that consumers are informed about competing products and cheaper substitutes. ‘X style’ or ‘X fragrance’ can be used to describe competitors’ products with similar features.Footnote 148 Using a registered name to truthfully inform consumers of the defendant's cheaper versions of protected products would be legal under the US law governing comparative advertising.Footnote 149 It is believed that if a seller has the right to copy the features of a competitor's goods accessible in the public domain, then it should also have the competitive right to inform consumers of this fact.Footnote 150 Indeed, ‘[t]he underlying rationale is that an imitator is entitled to truthfully inform the public that it has produced a product equivalent to the original and that the public may benefit through lower prices by buying the imitator.’Footnote 151

When the public interest in free and open competition is weighed against the interest of rewarding producers of quality products that would otherwise suffer market failure, the competitive interest trumps.Footnote 152 Thus, US trademark law is reluctant to protect product features to avoid creating monopolies over product characteristics.Footnote 153 Even if consumers associate a particular feature with its original producer (i.e., when the reproduction of the feature would create consumer confusion, just as in the CJEU case of Morbier), US trademark law does not prevent others from copying that feature if it is functional.Footnote 154 The high value placed on the competitive interest is also the underlying reason for the refusal to register generic terms, even if they have acquired secondary meaning through use.Footnote 155 Although a valid trademark may contain a generic term as one component, a disclaimer may be required to avoid creating the false impression that the term has been taken out of the public domain.Footnote 156 By contrast, no such disclaimer is required in the GI registration in the EU.Footnote 157

On the other hand, the US places less weight on the first three interests, particularly the interest in preserving the distinctiveness of GIs and preventing competitors from trading upon GI products’ reputation. Under the Lanham Act, a third party can use a place name registered as a trademark, provided that it is used in a non-trademark, geographical sense.Footnote 158 The ‘use otherwise than as a trademark’ enquiry is unconcerned whether using the place name is likely to give consumers the impression that the products bearing that name have a quality attributed to its place of origin. However, if all the products produced in a place can bear the place name regardless of the land–quality nexus, the place name that currently constitutes a GI will eventually degenerate into a simple indication of provenance, which only informs the location but no longer guarantees to consumers any origin-related quality. Thus, US trademark law is not designed to preserve the distinctiveness of GIs. Moreover, under the Lanham Act, free riding is not prohibited per se.Footnote 159 If third parties have taken a free ride on the reputation of the plaintiff's name without causing confusion or deception, it is believed that ‘they have taken that to which they were legally entitled’.Footnote 160

The above discussion shows that the EU and US's different approaches towards the fair use of GIs may be explained by the value placed on these different interests. Hence, a further question needs to be asked: why do the interests matter differently for the EU and US?

3.2 Divergent Policy Goals

The EU and US's preferences for the different interests can be explained by their divergent policy goals, which, in turn, depend on historical, economic, and cultural factors.

3.2.1 Economic and Trade Policy

European traders have a tradition of making their products using methods adapted to local conditions and marketing those products under the name of the place in which the products were made. As reputations grew for such products, the place name under which they were marketed became valuable.Footnote 161 In the worldwide market, most commercially valuable GI products originate from the EU due to the long history of production and promotion. The sales value of GI products was estimated to be EUR 74.8 billion in 2017, representing 15.4% of all EU food and beverage exports, which is ‘far from being a niche market’.Footnote 162 Besides generating economic value, traditional ways of production, which are practised in particular geographical areas and passed from one generation to another, now form part of Europe's traditional knowledgeFootnote 163 and common cultural heritageFootnote 164. Given the significant economic and cultural value, it is not difficult to understand why, for the EU, the interest of authorized GI users and producer groups outweighs other interests such as free trade and competition.Footnote 165 This preference is consistent with the EU's economic and trade policy that aims to ensure the exclusive rights of European geographical names in the EU market as well as in the markets of third countries and to prevent ‘any misuse, imitation and evocation’ that may otherwise be subject to fair use exceptions.Footnote 166

By contrast, the US lacks a long history of producing traditional products based on the probe of the relationship between the characteristics of products and their origin. When European immigrants to the US started to make substitute versions of the products initially produced in Europe, they placed European geographical names on their products just as they did in their country of origin.Footnote 167 Thus, it is in the best interests of the US to limit GI protection and incorporate GIs into US trademark law, which permits the fair use of descriptive names and free use of generic denominations,Footnote 168 since otherwise a large number of US products sold under European geographical names may need to be renamed. Furthermore, without sufficient fair use defences, the market access of US products in the international market would be constrained.Footnote 169 Thus, as a countermeasure to the EU's efforts to enhance GI protection through bilateral agreements with trade partners, the US has oriented its trade policy towards ensuring the market access of US products identified by ‘common food names’ and individual trademarks that may contain European place names.Footnote 170

3.2.2 Agricultural Policy

The divide on whether to value the interest in ensuring a fair return for producers of quality products may be understandable from the perspective of agricultural policy.Footnote 171 The EU believes that GI schemes contribute to the social, environmental, and economic sustainability of the rural economyFootnote 172 and thus incorporates them under its Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). In the 1990s, the CAP was reformed into a more integrated rural development policyFootnote 173 emphasizing quality competition and shifting the burden of agricultural subsidies from governments to the market.Footnote 174 Oriented by the objectives of agricultural and rural policy, including encouraging the diversification of agricultural production, achieving a better balance between supply and demand, and promoting products for the development of remote and less-favoured regions,Footnote 175 the first EU-wide GI Regulation was established for the registration and protection of GIs for agricultural products and foodstuffs. GIs, as ‘rural intellectual property rights’, were advocated as a quality policy to achieve those agricultural policy goals.Footnote 176 The great emphasis on fairness in agricultural and rural sector will continue to act as a foundation, as it is expressed in the new CAP (2023–2027).Footnote 177

‘New World’ countries deem EU agricultural policy to be ‘interventionist’.Footnote 178 In comparison with agricultural sectors in the EU, agricultural sectors in ‘New World’ countries such as the US have some or all of the following characteristics: ‘lower levels of agricultural subsidization; export orientation; economies of scale in agri-industries; higher levels of corporate control of production; and common adoption of European geographical terms’.Footnote 179 To bring prosperity to rural communities, the US relies on mass production through production technology advancements in the farming sector and sells its abundant primary commodities on the world market.Footnote 180 It prefers flexibility in agricultural production than fixed production practices involving traditional know-how.Footnote 181 Accordingly, US agricultural policy does not aim to encourage quality agricultural products based on terroir by securing higher incomes for their producers.

3.2.3 Competition Policy

Another reason for the divide on whether to ensure a fair return for producers of quality products is the disagreement over the impact of such a policy on competition. Although both the EU and the US share the same competition policy objective of preventing anti-competitive behaviours,Footnote 182 the EU promotes an incentive model that relates directly to the objectives of agricultural policy and protection of common cultural heritage and that differs from that oriented towards competitive innovation.Footnote 183 The EU defends that, by encouraging the production of high quality products and securing higher incomes for EU farmers, GI schemes can be used as an ideal device to maintain and strengthen competitiveness in the global economy.Footnote 184 However, the US sees the EU's policy as a form of protectionism, a mere pretext hiding the anti-competitive goal of monopolizing of the names of certain food and drink products.Footnote 185

In addition, although both the EU and the US include the promotion of consumer welfare within their competition policy,Footnote 186 they are divided on how they see the exact needs of consumers and how they respond to those needs. Considering that European consumers care more about the origin-based quality of products and look for certification and assurance on product origin and production method,Footnote 187 the EU is committed to providing clear and reliable information about the products with specific characteristics linked to geographical origin and helping consumers make informed purchases.Footnote 188 This policy goal explains why consumers’ interest in receiving credible information weighs heavily in the balance of infringement against fair use. In the newly launched Single Market Programme designed to support a well-functioning and sustainable internal market, enhanced consumer protection is still listed as a goal to achieve.Footnote 189 In contrast to heightened consumer protection, the US rests on the competition policy of protecting consumers from being deceived or confused by unlawful competitive conducts.Footnote 190 Such a policy is influenced by the US legal tradition that free competition is highly valued and public authorities only intervene in extreme circumstances such as fraud and deception.Footnote 191

In light of the foregoing, it can be contended that the EU and US's preferences for the different interests are deeply influenced by their policy objectives, which are, in turn, based on their respective national conditions. However, it is still too early to draw conclusions because even if the US had the same amount of valuable GI products as the EU, the divergence in the fair use of GIs would remain. The last root cause concerns the epistemology of ‘fairness’.

3.3 Fairness Gap

The EU and US are divided on the most fundamental issue of fair use, namely, the understanding of what is fair. This ‘fairness gap’Footnote 192 exists not only in the area of GIs but also in areas of other intellectual properties. Concerning the fairness of free riding in trademark law, for example, the EU and US draw the line differently between justified and unfair free riding. Free riding without any harm to a trademark's distinctiveness or reputation cannot serve as a basis for anti-dilution protection under US trademark law,Footnote 193 whereas in the EU it may constitute an independent actionable wrong: ‘tak[ing] unfair advantage of … the distinctive character or the repute of the earlier trade mark’.Footnote 194 Another example is the use of a competitor's trademark to truthfully inform consumers of a cheaper version of its product, which would be considered by European countries as ‘going beyond the limits of commercial fairness’Footnote 195 but would be legal under US law. As one commentator noted:

The US approach places a higher value on free markets, and thus leaves competition as unencumbered as possible, exposing consumers to a larger amount of information and opinion. The EU approach places a higher value on encouraging trademark owners to invest in the reputation of their brands, by protecting that investment against free riding or disparagement by competitors who may be unwilling to make the same investment. Both approaches seek to achieve fairness, but they are based on different understandings of what is fair.Footnote 196

Thus, when GIs or terroir products are not involved, the concept of fairness still has a much broader meaning in the US than it does in the EU: a broader group of activities are identified as fair in the US (e.g., free riding without deception and truthful comparative advertising). This divergence can be explained by a cultural difference. Common law countries place a high value on the freedom of competition, while civil law countries prioritize the protection of brand owners’ investment.Footnote 197 One cornerstone of the continental approach is that ‘economic freedom and free competition should be held limited to those competitive efforts which are the result of a person's own labor and merit and should not be extended to give undeserved sanction to any commercial benefits which are derived from usurpation of the fruits of a competitor's labor’.Footnote 198 However, for those who privilege the freedom of competition, the continental approach to limit competition is derived from traditional proprietary, protectionist bias, and is based on an erroneous idea that goodwill is a property belonging to the firm that invested in it.Footnote 199 Those different priorities influence how fairness is measured significantly. It seems that the more emphasis is placed on the freedom of competition and the less emphasis is placed on safeguarding the ‘proprietary aspect’ of brand owners’ investment, the more activities are determined as fair. Then, how can we expect the EU and US to reach a consensus on the fair use of GIs when the underlying meaning of fairness is a matter of disagreement?

4. Concluding Remarks and Recommendations

Why, despite many years of multilateral negotiation since the TRIPS Agreement was signed in 1994, does the tension surrounding the protection level for GIs remain unresolved? Unauthorized uses of GIs for describing and comparing competitors’ non-GI products, which the EU seeks to prohibit by negotiating a higher protection level, are not granted a fair use exception under EU domestic law but are permissible under the fair use defence in the US. Therefore, this article explores the obstacles to reaching an international consensus on the protection level by examining the divergent national practices on fair use exceptions and underlying causes. The research findings challenge the conventional wisdom that the prolonged tension is deeply rooted in a disagreement over terroir as a sound basis for protective regulations. On the contrary, even if countries such as the US had the same amount of valuable terroir products as the EU and equally embraced the terroir concept, they would not provide the same level of protection as the EU does. The reasons can be summarized in three aspects. First, different countries tip the balance towards different interests when choosing between granting fair use exceptions and imposing prohibitions or restrictions. Second, countries have different policy considerations for the economy, trade, agricultural development, and market competition. Finally, and most fundamentally, the understanding of what is fair is different.

It can be deduced from the findings that the recent bilateral agreements cannot resolve the tension left by the WTO multilateral talks. In light of the deadlock of further negotiations in the WTO arena, it has become common to resort to free trade agreements to pursue a higher level of protection for GIs. However, the lack of provisions on the fair use of GIs in those bilateral agreements undermines the effort to enhance GI protection because different countries will show different attitudes towards the fair use of GIs. The unauthorized use of GIs could be judged as an infringement in one jurisdiction but recognized as fair use in another, ultimately affecting the protection level. Moreover, this neglect creates opportunities to counter the effort for enhanced protection by securing a broad scope of fair use through bilateral agreements.Footnote 200 In short, owing to the absence of provisions on the fair use of GIs, what cannot be achieved on the WTO negotiation table still cannot be achieved by free trade agreements.

Given this unresolvable tension, WTO Members are faced with the difficult choice between stronger GI protection (as promoted by the EU) and weaker GI protection (as advocated by the US). Another principal result of our study is the recommendation that before the choices are made, considerations should include not only the terroir concept and the economic value of terroir products for their respective jurisdictions, but also the status quo of the balance of interests, policy goals, and understanding of what is ‘fair’. Only in this way would it be possible to prevent GI protection from turning against the consistent preference for certain interests; the very idea of how trade, economy, and competition should be regulated; and the well-established concept of ‘fairness’.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. The support of the China National Social Science Foundation (21CFX080) is gratefully acknowledged. Assistance provided by Ning Li and Yinger Shang is greatly appreciated.