Introduction

Royal progresses have been observed in various forms throughout world history, from journeys made by Assyrian kings, to the progresses of England's Elizabeth I.Footnote 1 This study uses the concept of the royal progress to re-examine a related phenomenon: that of alternate attendance (sankin kōtai) performed by the elite warriors of Japan's Tokugawa period (1600–1868). Approximately once a year, for two and a half centuries, daimyo lords, their samurai retainers and servants paraded along Japan's highways between their castle towns and the city of Edo in order to attend upon the shogun.Footnote 2 Daimyo wives and heirs lived permanently in Edo as hostages. Alternate attendance has been likened to Louis XIV's court at Versailles in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, and to the medieval German practice of Hoffahrt.Footnote 3 Here, I argue that the ambiguous nature of sovereignty in Tokugawa Japan, with effective rule divided between the shogun and the daimyo, also allows us to consider alternate attendance as a form of ‘royal’ progress in so far as concerns the leg of the journey that took place within the daimyo's own territory (his domain, or han). This approach reveals the localised semiotics of daimyo power, as daimyo lords spent time in villages within their territory, holding audiences, giving out favours and receiving signs of submission from locals, before leaving their domain and embarking on the journey to Edo.

The focus of this article is a case study for which there exists a cache of local history materials detailing the visits made by the lords of Satsuma domain to a village of Korean potters and their descendants, en route to Edo during the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Satsuma was located on the southern Japanese island of Kyushu, its hereditary daimyo rulers belonged to a family called the Shimazu, and the Korean potters in question had settled in the village of Naeshirogawa in Satsuma after being taken there by the Shimazu armies during the Japanese invasions of Korea, which took place between 1592 and 1598 (the Imjin War).Footnote 4 Thanks to records kept by the villagers, fifteen eyewitness accounts of daimyo visits to Naeshirogawa between 1677 and 1714 are extant, including the ceremonies and entertainments that were performed on these occasions; in addition, the Naeshirogawa records depict, albeit in lesser detail, the growing relationship between the daimyo and the village in the first half of the seventeenth century.Footnote 5 Largely unused by historians, the extant manuscripts of these records were compiled in the nineteenth century, from older, as yet unknown, documents kept in the archives of families from Naeshirogawa. However, despite the late compilation period of the extant, nineteenth-century documents, a comparison with the dates of daimyo travel contained in official Satsuma sources reveals that the Naeshirogawa records are highly accurate when it comes to the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century daimyo visits.Footnote 6

Such details would otherwise have been lost to history, since Satsuma officials did not consider this information worthy of inclusion in the domain's official histories, although they did keep a record of the routes taken by the daimyo each year, as well as the protocols for what were considered more important stations along the way. A paucity of similar local historical materials discovered to date for other domains means that we know much more about the better-documented aspects of alternate attendance in the urban gaze, for example in the merchant city of Osaka or the shogunal capital of Edo, for an external audience of the non-domain public, the shogunate and other daimyo. Further reasons for focusing upon a village in Satsuma include the fact that this domain boasted the oldest ruling warrior family in Tokugawa Japan, operated with a high degree of agency in international affairs thanks to its annexation of the Ryukyuan kingdom (modern-day Okinawa) in 1609, and was instrumental in toppling the shogunate in the nineteenth century, thus making for a particularly intriguing case study when it comes to Tokugawa sovereignty and the dynamics of local power.

I contend that, even after being confirmed as daimyo of Satsuma by the new Tokugawa regime in the early seventeenth century, the Shimazu – who had much older links to their territory – simultaneously maintained their own local narratives of legitimacy, and that the Naeshirogawa encounters show how alternate attendance could be used for this internal, domain agenda. This agenda is not unlike that which has been highlighted in the study of royal processions in world history, which the anthropologist Clifford Geertz described as a kind of scent-marking that ‘stamp[s] … a territory with ritual signs of dominance’.Footnote 7

Furthermore, the role of Naeshirogawans in Satsuma alternate attendance practices has echoes of what scholars have already noted concerning the periodic presence of representatives from the Ryukyuan kingdom in the retinue that the Satsuma lords took with them to Edo. It is well known that displays of foreign culture emphasised Satsuma's conquest of Ryukyu and were used to leverage Shimazu power vis-à-vis the shogunate.Footnote 8 Here I argue that the involvement of foreign culture in Satsuma's alternate attendance parades was also a factor in the internal domain significance of the processions, and that the symbolism of subdued foreign subjects from Naeshirogawa and their descendants paying homage to the Shimazu family was intended to legitimise Shimazu's power in their local region. This in turn contributes to a growing body of scholarship which re-evaluates the symbolic importance of foreigners for early modern Japanese rulership.Footnote 9

Royal origins of alternate attendance parades

From the eighth until the fourteenth century, royal progresses (gyokō or miyuki) in Japan were occasional rites that functioned as sites for the display of the emperor (tennō) and his or her entourage, and for the presentation of the ruler's munificence.Footnote 10 These elaborate public excursions were originally the purview of the sovereign, but over time were adopted by the warrior class, as effective rule shifted out of the hands of the court and into the jurisdiction of successive shogunates and local warlords, with the emperor coming to occupy a largely ceremonial role. During the fourteenth century, with the waning of the economic power of the court and the instability brought about by war, Japan's emperors curtailed their visits to locations far from the Kyoto Imperial Palace, and remained within their neighbourhood.Footnote 11 The tradition of the procession was instead adopted by the Ashikaga shoguns (1336–1573), who visited powerful temple complexes, performing ritual gift exchanges in order to demonstrate that the shogun stood at the peak of the temple power hierarchy, ‘in essence holding kingly authority’.Footnote 12

In the mid-seventeenth century, the newly established Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1868) further restrained emperors from travelling beyond the Kyoto Imperial Palace, and with very few exceptions only retired emperors were permitted to travel.Footnote 13 There were, however, numerous other types of parades during the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, such that historians have described Tokugawa Japan as an ‘age of parades’.Footnote 14 There were shogunal excursions, including pilgrimages to the shrine of the Tokugawa house, located in Nikkō to the north of Edo, and there were periodic embassies sent by Choso˘n-dynasty Korea and the Ryukyuan kingdom, which involved large processions and public spectacle.Footnote 15 In addition, there were regular street parades for local festivals celebrated across the archipelago. However, the overwhelming bulk of elaborate public processions each year was performed by Japan's daimyo as part of the alternate attendance system.

In the absence of imperial progressions, alternate attendance parades filled a gap left by the court, publicly displaying power on the streets. Unlike imperial progresses, however, these daimyo spectacles drew largely on the format of the military parade, and footmen carried weapons including lances, bows and firearms. The weapons used were highly decorated and primarily designed for display, and were usually carried only at important performance points in the journey such as the departure from the castle town, the arrival at the main camps en route and the arrival in Edo.Footnote 16 The parades thus provided an opportunity to symbolically assert warrior dominance during the ‘Pax Tokugawa’, roughly two and a half centuries of peace during which there were few opportunities to make an actual show of military force in battle.

As well as being a public spectacle in Japan's ‘age of parades’, alternate attendance was a military institution based on the centuries-old warrior practice of the lord requiring the periodic attendance of his retainers by his side.Footnote 17 It was one of the types of service that the daimyo lords owed to the Tokugawa shogunate by virtue of their vassalage, in return for which they received land grants and the right to rule their domains. The system was founded during the first half of the seventeenth century following the battle of Sekigahara in 1600, which established Tokugawa dominance. Many of the daimyo who had fought against the victor, Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), offered close family members to Ieyasu as hostages, following precedents dating back to the Warring States (1467–1568) period of Japanese history.Footnote 18 The Shimazu from Satsuma, who are the subject of this article, had fought against Ieyasu at Sekigahara, and were among the first to offer him family members as hostages, such that some historians of Satsuma suggest the alternate attendance system was institutionalised for the Tokugawa by the actions of the Shimazu.Footnote 19 In subsequent decades, the hostage arrangements were regularised. All daimyo were required to leave their family in Edo, and to divide their time between their home domain and the capital.Footnote 20 The system changed over the course of the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries with regard to the timing and frequency of the daimyo visits to the capital, but in practice they usually made an annual journey, travelling to Edo one year and returning to their domains the next.

This study contributes to scholarly debates about the extent to which alternate attendance was compulsory, and the extent to which it served daimyo or shogunate interests. The vast outlay of resources required to maintain two residences, one in the daimyo's castle town in his domain and one in Edo, as well as the travel expenses associated with regularly moving retinues consisting of hundreds or thousands of people across the country, was a heavy burden.Footnote 21 Until recently, the main school of thought held that the requirement to divide their time between their domains and Edo was forced upon the daimyo by the shogunate, and that it served to reduce the threat of rebellion by keeping the daimyo in a state of permanent financial distress – a theory which dates back at least as far as the Confucian scholar Ogyū Sorai (1666–1728).Footnote 22 Recent research, however, has shown that the system changed over time, and from the mid-eighteenth century onwards the shogunate was unable to enforce set times for attendance, with daimyo choosing to attend when it suited them. Scholars have begun to investigate the mutual benefits of the system for both the daimyo and the shogunate.Footnote 23 In the case of Satsuma, the period during which alternate attendance and the visits to Naeshirogawa were established coincided with what Robert Sakai has dubbed the ‘consolidation of power’ in the domain, which followed several decades of regional instability resulting from late sixteenth-century power struggles in Kyushu, Satsuma's involvement in the Imjin War and the Shimazu defeat at Sekigahara. As we will see, the Shimazu found value in the alternate attendance system due to the opportunity it allowed them to be publicly visible as they travelled through their domain and to regularly assert their sovereignty in their local region.

Sovereignty

The delicate balance of power between the Tokugawa shogunate and the daimyo foregrounds this discussion. Despite being more powerful than any of Japan's rulers since the height of the imperial state in the eighth century, the shoguns who ruled during the first century of the Tokugawa period did not have direct control over commoners who resided outside of Tokugawa landholdings. Instead, the Tokugawa asserted authority over daimyo, requiring them to pay tax, perform public acts of loyalty like alternate attendance, and defer to the shogunate on matters of international diplomacy, trade, coastal defence and limiting contacts with foreigners.Footnote 24 The daimyo, in turn, directly ruled the warriors and commoners of their own domains. Daimyo might thus be considered, in Mark Ravina's words, ‘sovereigns who were subordinate to a superior sovereign’.Footnote 25 Ravina uses the term ‘compound state’ to describe the overlapping sovereignties of Tokugawa Japan, a translation of the term fukugō kokka, coined by Japanese legal historian Mizubayashi Takeshi, who was in turn adapting the European idea of ‘composite monarchies’ as popularised by J. H Elliott.Footnote 26 This approach is not without its controversies in the Japanese case. The alternative position was summarised by Ronald Toby, who points out that daimyo control ‘even in the minds of their most ardent local supporters – remained conditional and was not “sovereign” in any substantive sense’, arguing that identification with the political space of a Japanese proto-nation was never effaced by domain loyalties.Footnote 27

While a definitive answer about the precise nature of sovereignty in early modern Japan remains elusive – particularly when using structural concepts derived from European history – what is clear is that there existed overlapping regimes of power. And these regimes were expressed using parallel linguistic and semiotic registers. By employing the Tokugawa period political concepts of omote (exterior) and naibun (interior), Luke Roberts shows how power was discussed in two parallel vocabularies, depending on whether the context was ‘external’ shogunal business or ‘internal’ domain business. Warrior officials for example, used the term ‘state’ (kokka) when describing their domain for a local audience, but would recognise the superiority of the shogun when addressing documents to Edo.Footnote 28 In practice, such dualities meant that one official event or practice, like an alternate attendance parade, could have polyvalent meanings tailored to fit both ‘internal’ and ‘external’ audiences.

The polyvalent meaning of parades has been noted in relation to the ritual activities of the Ryukyuan embassies that were despatched to Edo, travelling either with the Satsuma alternate attendance retinue or escorted by Satsuma retainers. Travis Seifman argues that these embassies served to enact on the Tokugawa stage Ryukyu's position as a sovereign kingdom and loyal tributary of the Ming and Qing imperial courts, while at the same time asserting for a Japanese audience that the kingdom was under the banners of the Shimazu family.Footnote 29 Kido Hironari has further shown how this duality was expressed in two parallel terms describing Ryukyu's status: one as a vassal state (fuyō) of the Shimazu, and the other as a foreign state (ikoku) subservient to the Tokugawa. The Shimazu were able to deftly use these two statuses of fuyō and ikoku for different strategies when describing Ryukyu to third parties, and this facilitated the dual meanings that the Ryukyuan processions held.Footnote 30

Such dualities underpin the approach in this article. As noted, alternate attendance has been understood primarily through an external or Edo-centric lens. One of the leading authorities on alternate attendance, Constantine Vaporis, astutely notes that Tokugawa Japan was ‘almost a mirror image’ of countries elsewhere in the world in which the monarch was in motion and his or her lords were stationary points to be visited during royal progresses; in Japan ‘the lords, and not the hegemon, were rendered portable.’Footnote 31 This is undoubtedly true for the external, Edo-facing aspects of alternate attendance which served to reiterate the shogun's position at the top of the Tokugawa warrior hierarchy. Adding to this picture, I argue here that alternate attendance, like many political phenomena in Tokugawa Japan, could also be symbolically used for an ‘internal’, local purpose, with the daimyo behaving like portable sovereigns within their own territories. Even as a daimyo embarked upon a journey to offer obeisance to the shogun, the rituals and spectacle of his procession could simultaneously be used to assert his own power and claims to rulership within his domain. Such was the case with Satsuma.

Alternate attendance in Satsuma

At the southernmost tip of the island of Kyushu, Satsuma was the furthest domain from the shogun's city of Edo. Thus, of all the daimyo, the Shimazu had the longest journey and one of the heaviest financial burdens involved in maintaining the practice of alternate attendance. The trip was approximately 1,400 km one way and took two months, travelling over rough terrain, by land and by sea.Footnote 32 The route to Edo and back again was regulated by the shogunate for the part of the journey between Edo and the merchant city of Osaka. However, between their castle town of Kagoshima and the edge of their territory, the Shimazu were in control. Based on the roads in their domain, they had several options, one of which took them through the village of Naeshirogawa that is the subject of this article (route A in Figure 1). Until the middle of the Tokugawa period, the Shimazu usually took either the Izumi Highway (Izumi suji, route A), or the Ōkuchi Highway (Ōkuchi suji, route B).Footnote 33 Ostensibly, their choice was dictated by the time of year they were required to travel, and the direction and strength of the prevailing winds at sea.Footnote 34 However, as we will see, the opportunity to visit Naeshirogawa, to observe the ceramic industry there, and to receive displays of loyalty from its ‘foreign’ inhabitants, may also have been a factor in which highways they chose to take within their domain.

Figure 1. Three routes taken through Kyushu to Edo by Satsuma daimyo. (Source: Clements, ‘Daimyō Processions and Satsuma's Korean Village’, 227.)

The official records of Satsuma contain details of the elaborate preparations that were made for the beginning and end of their momentous journeys.Footnote 35 Strict protocols were followed as to the manner in which the lord, hidden within his palanquin, was to be transported, including how the castle should be decked out with particular folding screens for his arrival and departure, and precisely what refreshments were to await him. Before leaving for the capital, the Satsuma lord would conduct a ceremony known as yakkō kenbun (an inspection of his troops), and would visit a shrine.Footnote 36 According to Satsuma domain records from 1783, on the day of the daimyo's departure for Edo the streets of Kagoshima were to be swept clean, and proper decorum observed:

… people outside their homes are to go inside … As the procession passes they are to show proper respect, kneeling with their heads on the floor … Most importantly, when the lord is going to and from the capital, people should not disperse in a vulgar manner until the part of his entourage containing his senior officials has passed by.Footnote 37

The Satsuma procession ranged from as few as 500 men to as many as 3,100, including porters and other hired labourers.Footnote 38 All sections of the entourage did not necessarily travel together for the entire journey, and as the instructions above indicate, the greatest respect was reserved for the daimyo and his senior officials.

Similar rituals have been recorded for other domains and were designed to inspire awe and command obedience among the daimyo's subjects.Footnote 39 We do not have direct evidence of the extent to which the rules on decorum were followed by the citizens of Kagoshima. Research suggests that in other parts of Japan the enforcement was patchy.Footnote 40 However, at the very least, the rules prescribed here show an intent to remind the daimyo's subjects of his power in his home town. The example of Naeshirogawa shows how this power was ritually asserted in a village within the daimyo's domain.

The village of Naeshirogawa

Naeshirogawa (now incorporated with another village, and known as Miyama) is located approximately 22 kilometres north-west of Kagoshima, one day's journey for the Shimazu's lords in their palanquins.Footnote 41 The activities that took place during daimyo visits showcased the ceramic industry that flourished there, and the foreign culture of its inhabitants. Naeshirogawa's kilns were among the many that had been founded in Kyushu by Korean potters brought to Japan during the Imjin War.Footnote 42 Most of the Korean potters and their family members (seventy individuals in total) whom the Shimazu armies brought to Satsuma moved to Naeshirogawa early in the Tokugawa period, or were relocated there over the course of the seventeenth century, such that Naeshirogawa became the main site of Korean ceramics in the domain.Footnote 43 The kilns produced the distinctive ‘black Satsuma’ (kurosatsuma) and ‘white Satsuma’ (shirosatsuma) wares for which the area is still famous.Footnote 44

Although the exact size of Naeshirogawa's contribution to the Satsuma economy is unknown, its ceramic industry was prolific, and this in part accounts for the attention they received from the Shimazu. Initially, the Naeshirogawa kilns produced large everyday domestic items such as storage vessels and mortars. In the latter half of the Tokugawa period, teapots were fired in large numbers and sold not only within the domain but to other parts of Japan, providing a source of income for Satsuma.Footnote 45 Sherds from Naeshirogawa teapots have been excavated at sites across mainland Japan and in Okinawa (formerly Ryukyu). The squat, black teapots exported by Satsuma and produced mainly in Naeshirogawa were so ubiquitous throughout Japan that this particular type came to be known as a ‘Satsuma teapot’ (Satsuma dobin) no matter where it had been produced.Footnote 46

The Shimazu recognised the importance of the Naeshirogawa ceramics industry, and put measures in place to protect the village community. The Naeshirogawa documents record gifts of land rights in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, including cultivation lands and the right to cut wood from local forests for their kilns.Footnote 47 After tensions between locals and the potters over access to firewood led to an outbreak of fighting in 1666, the then daimyo, Shimazu Mitsuhisa, issued a decree that no one was to harm the ‘Koreans’ and that offenders and their families would be punished.Footnote 48 The domain also periodically built wells and constructed houses as the population of Naeshirogawa increased, and provided financial aid in times of difficulty.Footnote 49

In addition, the domain promulgated regulations designed to protect the villagers’ Korean identity, as the original war captives died out over the course of the seventeenth century.Footnote 50 In 1676 it was forbidden for the people from Naeshirogawa to marry outside the village and move away, although people from other villages were permitted to marry into the Naeshirogawa community. In 1695, the villagers were prohibited from using Japanese names, and any who had a Japanese name were ordered to change it to one from their country of origin.Footnote 51 The prohibition of marriage outside the village may be understood as being designed to prevent the loss of specialised knowledge of ceramic production, and was a regulation seen in other Satsuma villages with a specialised occupation, such as mining or fishing.Footnote 52 The order to preserve Korean names may also be seen in this light, but it is likely that a desire to preserve the ‘Korean-ness’ of the village was also at work. Like the representatives of Ryukyu, the villagers were required to present themselves in foreign dress at the daimyo's castle in Kagoshima to offer New Year's greetings, together with Japanese vassals of the Shimazu.Footnote 53 Furthermore, Naeshirogawa provided Korean language interpreters for Satsuma throughout the Tokugawa period, in order to deal with Korean ships that arrived in Satsuma ports or were washed up on the coastline.Footnote 54 The foreign cultural capital and the perceived Korean otherness that the Naeshirogawans possessed was thus clearly valued by the Shimazu family. In the encounters discussed below, the display of Korean culture through dress, dance and displays of writing, as well as their ceramic products, was a key feature of the rituals and entertainments that took place.

Daimyo visits to Naeshirogawa

The earliest recorded daimyo encounters with the Naeshirogawa villagers occurred in the second decade of the seventeenth century. The Naeshirogawa village document, Sennen Chōsen yori meshiwatasare tomechō (‘A record of how we were brought from Choso˘n [Korea] in years gone by’), and its variant manuscripts describe how the daimyo (referred to on this occasion as ‘the counsellor’ or chūnagon) would hold an audience with representatives from Naeshirogawa when he passed through on his travels, in order to receive updates on the production of white stoneware in the village.Footnote 55 Although this entry is undated, other documents from Naeshirogawa note that it was in 1614.Footnote 56 This indicates that the visitor was Shimazu Iehisa (1576–1638), who was daimyo of Satsuma between 1601 and 1638 and who held the honorary court rank of counsellor. Keen to improve the economy of his domain, Iehisa had ordered that a search be made for clay suitable for producing pottery, and had been delighted with the results achieved by the potters in Naeshirogawa.Footnote 57

The village records then describe how Iehisa began to stay regularly at the district headquarters (kariya or kaiya) in nearby Ichiki on his journeys to and from Edo. On such occasions, he would summon the villagers to perform a type of religious dance, known in the Satsuma pronunciation as kanme (‘sacred dance’).Footnote 58 The kanme dances of Naeshirogawa were performed by priests from the village shrine, which was dedicated to Tan'gun, the mythical progenitor of the Korean people.Footnote 59 These dances were performed according to Korean rites and with Korean costumes and were a visible manifestation of the foreignness of Naeshirogawa's inhabitants displayed before their lord. The pride with which they were held by the domain is further indicated by the fact that the dancers, together with Naeshirogawa's kilns, were later depicted in Sappan shōkei hyakuzu (‘A hundred superlative views of Satsuma’), a coloured, hand-illustrated guide promoting the domain, which was commissioned by the daimyo of Satsuma in 1815 and presented to the shogun.Footnote 60

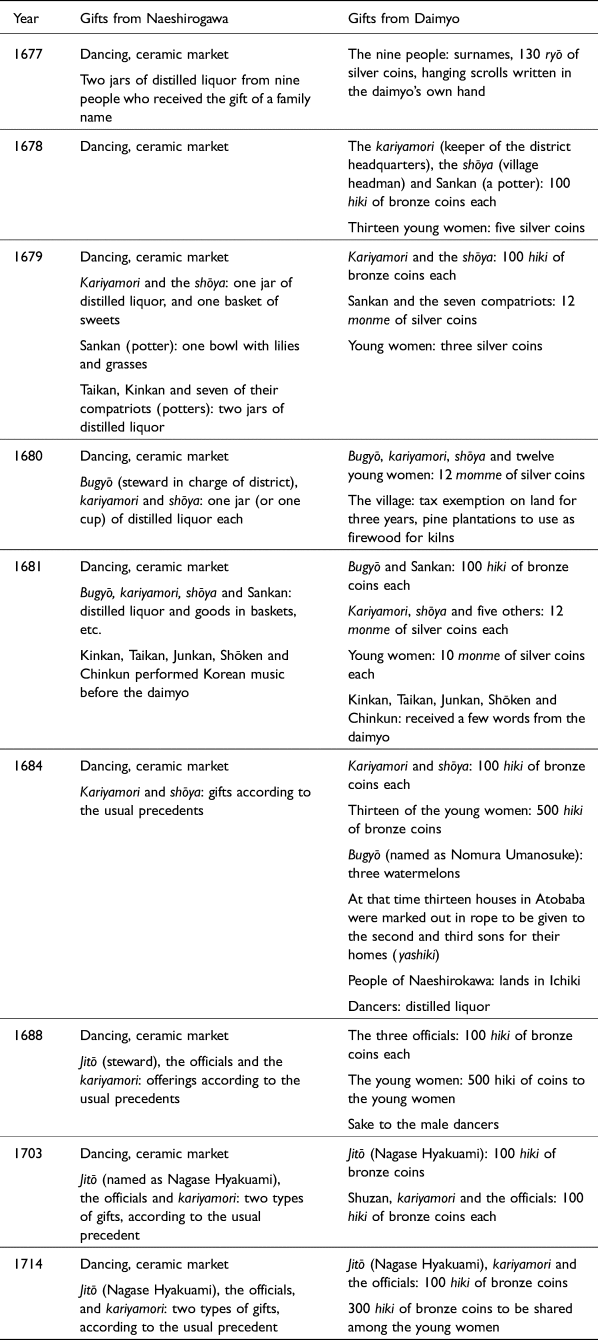

Not long after Iehisa began interacting with the Naoshirogawa villagers, an official rest house (chaya, lit. tea house) was built in Naeshirogawa near the kilns.Footnote 61 The early records of the rest-house encounters offer the first glimpse of the nature of the hospitality arrangements between the village and the daimyo entourage: rice was brought out from the official storehouse, there would be displays of dancing and the villagers would receive gifts of silver from the daimyo.Footnote 62 We see an expansion of the detail in which each of these visits was recorded in the Naeshirogawa documents from 1677 onwards, providing more information with which to interpret the meaning of such interactions (see Table 1). The district headquarters, where the daimyo stayed overnight when travelling through his domain, was moved to Naeshirogawa in 1675, and the records report fifteen overnight visits by the daimyo to Naeshirogawa between 1677 and 1714.Footnote 63

Table 1. Examples of gifts exchanged between Naeshirogawa villagers and the Satsuma, 1677–1714

Source: Sennen Chōsen yori meshiwatasare tomechō, and its variant manuscripts reprinted in Fukaminato, ‘Satsumayaki o meguru Naeshirogawa kankei monjō ni tsuite’.

As the following extract from 1679 serves to illustrate, visits usually revolved around displays of dancing, a ceramic market displaying the villagers’ wares, and gift exchange ceremonies between the villagers and the daimyo:

In the seventh year of the same era, Kan'yōin (Shimazu Mitsuhisa) was going up to the capital. On the nineteenth day of the fourth month he arrived at Naeshirogawa. On the twentieth day he viewed the [ceramic] market and the dancing. On the twenty-first day of the same month, he commanded further dancing. The Keeper of the District Headquarters (kariyamori) and the Village Headman (shōya) offered up the usual gifts of one jar of distilled liquor and one basket of sweets. [The potter named] Sankan offered up one bowl with lilies and grasses on it. Seven people, including Taikan and Kinkan, offered up two jars of distilled liquor. On the twenty-second day of the same month … the Keeper of the District Headquarters and the Village Headman were each given 100 hiki [3.75 kg] of bronze coins. Sankan and the previously mentioned seven people were given 12 monme [45 g] of silver coins. The young women were given three silver coins. The lord departed at the hour of the sheep [approx. 2 p.m.] that same day.Footnote 64

As Table 1 shows, the gifts offered by the villagers usually took the form of jars of distilled liquor and baskets of sweets. The gifts most commonly given by the daimyo to the villagers were currency, followed closely by the bestowal of honours such as the right to a family name and a sword, which signified a rise in status for the recipient from commoner (hyakushō) to the warrior (shi) class. On occasion, there were unusual gifts such as the ceramic bowl with an illustrated design given by one of the senior potters as a symbol of the industry they had founded, or the three watermelons given by the daimyo to the magistrate (bugyō, i.e. the vassal responsible for the outer castle district to which Naeshirogawa belonged), Nomura Umanosuke, in 1684, which were elite gifts popular at the time and a fitting reinforcement of Umanosuke's status.Footnote 65

The meaning of gifts

For reasons of space, a detailed, anthropological study of the gifts exchanged between the Naeshirogawans and the daimyo will have to await another occasion. Instead, this article will examine the meaning of the most commonly exchanged gifts, as they relate to the role of alternate attendance in the domain. Gift exchange was fundamental to the workings of medieval and early modern Japanese society and remains so today, to the extent that Japan has been described as having a gift economy.Footnote 66 This has been explored through the theory of gifts founded by Marcel Mauss, who, although working on primitive societies, identified two main facets of gift-giving that proved to be particularly relevant to later studies of the Japanese case. Where gift-giving is part of the rituals of a society, Mauss argued, the appearance of a gift freely offered often belies the fact that at heart there is some obligation or economic interest at stake.Footnote 67 Japanese warrior society has been shown to be underpinned by principles of reciprocity between lord and retainer, as well as between lord and commoner.Footnote 68 Exchanges of goods, allegiances and patronage within this system were often couched in terms of gifts despite being transactional in nature.Footnote 69

In the encounters between Naeshirogawa villagers and the Satsuma daimyo, the regular gifts of money from the daimyo may be understood as a kind of payment clothed in the form of a gift so as to make a public display of the lord's generosity. Although we do not have direct evidence of how the money was used in the Naeshirogawa case, earlier and contemporary precedents suggest that this currency was intended to cover at least some of the costs of hosting the daimyo and his entourage.Footnote 70 This money, together with less tangible gifts from the daimyo, such as the honour of his presence, or the right to bear a surname, furthermore went towards supporting the people responsible for the ceramic industry in Naeshirogawa, which in return provided an important source of income for the domain. The transactional ‘gift’ of a surname was also awarded to residents of other communities in Satsuma with special skills, such as the gold miners of Yamagano and tin miners of Taniyama.Footnote 71

Mauss also argued that gift-giving strengthens the bonds of a society. During daimyo visits, a relationship of mutual benefit and fealty between the Shimazu and the villagers was thus articulated through elaborate ceremonies of gift-giving, banqueting, dance and displays of local wares. These exchanges symbolised the relationship of dependency that the Naeshirogawa village had with the Shimazu lords, as well as the importance of Naeshirogawa to the domain and the patronage to which they were entitled as a result. The villagers’ offerings of symbolic gifts with low monetary value, such as wine and sweets, together with displays of their ceramic wares and foreign culture, were outward expressions of their dependency, ‘offered up’ (shinjō) to their lord for his enjoyment. This in turn placed an obligation on the daimyo to offer the villagers his protection and support. The gift exchanges, furthermore, reinforced social hierarchies, with district officials such as the steward, Umanosuke, receiving high-status gifts, officials from the village receiving the largest amounts of money, and so on, down to those who are listed last in the sources – usually the young women, whose role is unidentified, but were probably serving as wait staff during the festivities, and who usually received a few coins.

We have little information on the ritual exchanges that took place in other villages within Shimazu territory as they passed through on their way to Edo. This is particularly true of the early period that the Naeshirogawa records describe. However, there are later clues, which suggest that similar festivities were held elsewhere, although not with the same duration and regularity as in Naeshirogawa. A Satsuma protocol document from 1751, for example, includes a brief list of reception ceremonies that were to be conducted at rest stops in Satsuma – including Naeshirogawa – upon the occasion of the daimyo entering his domain for the first time.Footnote 72 In this document, one village is required to perform a dance, and for the other reception points, including Naeshirogawa, the requirement is to present ‘offerings according to the usual precedents’ (shinjōbutsu, senrei no tōri).Footnote 73 The wording of this latter requirement is identical to that which appears in the Naeshirogawa records in relation to the presentation of sweets and alcohol, suggesting that the presentation of these or similar items was standard practice in the domain. Further clues are to be found in nineteenth-century diaries of retainers who travelled in the Shimazu entourage. Yamada Tamemasa, a retainer of Shimazu Nariakira (1809–1858), recorded in 1854 that the daimyo viewed displays of fishing on the river in Mukoda, and received a visit from Satsuma's representative in Nagasaki, who offered him sweets.Footnote 74 These patterns, including displays of local industries or entertainments and the offering of sweets, suggest that the broad framework for the Naeshirogawa ceremonies was couched in semiotic terms that would have been readily understood in Satsuma as conveying the relationship of daimyo and subject.

However, it should be noted that Naeshirogawa seems to have received particular attention, and more of the daimyo's time, than other villages. The daimyo sojourns in Naeshirogawa usually lasted at least two, sometimes three days, whereas retainer diaries show that less time was spent in other villages.Footnote 75 Furthermore, the Naeshirogawans were subject to the special regulations and appearances at the Shimazu's castle in Kagoshima discussed above, which they undertook together with senior Shimazu retainers and the Ryukyuan representatives living in Kagoshima. The Naeshirogawa village receptions thus occupied a special role in the Shimazu alternate attendance system, the reasons for which are discussed below.

Foreigners and the consolidation of power in Satsuma

The material and symbolic benefits of alternate attendance visits for the village of Naeshirogawa are clear. But why did benefits accrue to the domain from this particular village's displays of loyalty and submission? An explanation may be found in the localised power dynamics of Satsuma and its regional economy. The ritual activities of the Naeshirogawa visits were designed to publicly shore up the Shimazu's local claims to power, which rested not only on their investiture as daimyo by the Tokugawa, but on their long history of rulership in Kyushu, their ability to command obedience from foreigners in their region and to bring foreign resources, goods and trade into Satsuma for the benefit of the local economy.

Although invested by the Tokugawa with the right to rule their domain, the Shimazu continued to draw upon local claims to power that predated that investiture by over 400 years. Of all the families who ruled Japan's approximately 300 domains, the Shimazu had the longest continuous history of daimyo status, claiming to trace their origins to Koremune Tadahisa (1179–1227), who was supposedly the son of Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147–1199), the founder of Japan's first shogunate.Footnote 76 In 1197 Tadahisa's putative father made him governor (shugo) of Satsuma and Ōsumi provinces. Hyūga province was later added, and Tadahisa's descendants ruled in the region for the next 700 years, until they played a deciding role in the Meiji revolution of 1868, which overthrew the Tokugawa shogunate and established Japan's modern constitutional monarchy.Footnote 77 Powerful governors like Tadahisa became daimyo lords, exercising military and economic power in their provinces under the often nominal overarching power of the shogun. The precise nature of the daimyo–shogunate relationship evolved between the twelfth and the sixteenth centuries, from the twelfth-century ‘shugo daimyo’ like Tadahisa, through the largely autonomous daimyo of the civil war period (‘sengoku daimyo’), to the daimyo of the Tokugawa period (‘kinsei daimyo’), who ruled their domains but with stricter requirements of vassalage to the shogun.Footnote 78 The Shimazu were the only daimyo family of the Tokugawa period to rule continuously throughout the development of the daimyo institution from its origins in the twelfth century.Footnote 79 The size and geographical spread of their holdings fluctuated as the family's political fortunes rose and fell; however, the Shimazu retained constant control over Satsuma province, and by the period covered by this article, once again controlled all three provinces, Satsuma, Ōsumi and Hyūga (collectively known as Satsuma domain or Kagoshima domain at the time).

Moreover, although the Shimazu were on the losing side at the epoch-making battle of Sekigahara in 1600, they retained control of their territory afterwards. In the post-Sekigahara period, Tokugawa Ieyasu stripped many daimyo of their lands entirely or moved them to new territories. The practice of regularly moving daimyo around in order to break ties with their traditional power bases, reduce the size of their agricultural incomes or surround the shogunal lands with friendly allies continued throughout the Tokugawa period. It was so common that the term ‘potted plant daimyo’ (hachiue daimyō) was coined to describe the situation.Footnote 80 However, the Shimazu retained their historical territories in Kyushu and were not moved throughout the entirety of the Tokugawa period.

The Shimazu used their long lineage as a source of local legitimacy in tandem with their confirmation as rulers by the Tokugawa shogunate. In 1641, in response to a request from the shogunate that all daimyo submit copies of their family trees, the Satsuma Office of Records compiled a family tree for the Shimazu, which claimed their ancestry could be traced to Tadahisa, and submitted this to the shogunate together with a list of the honours bestowed upon them by successive Tokugawa shoguns, from Ieyasu onwards.Footnote 81 Together, these two documents effectively laid out two sources of Shimazu legitimacy: their history of rulership, and the contemporary favour of the Tokugawa shoguns. These parallel sources of legitimacy are reflected in the parallel semiotics of Satsuma's alternate attendance parades: on the one hand, as previous scholars have noted, the journeys were undertaken in order to show obedience to the shogun and to cement the Shimazu's external position in Japan's warrior hierarchy, while on the other, as I argue, within the domain they were used to assert Shimazu's own localised claims to sovereignty.

Such public assertions of power were necessary since, despite their long history of rulership and their investiture by the Tokugawa, Shimazu power in their region was not absolute, nor was it unchallenged. They were particularly vulnerable to local challenges to their authority due to Satsuma's system of ‘outer castles’ (tojō), an institution unique to the domain, that shored up their regime but also necessitated the careful management of local perceptions of Shimazu authority to counteract rebellion. In the late sixteenth century, the hegemon Toyotomi Hideyoshi had begun the process of disarming the peasantry and moving samurai off the land into castle towns where they were more easily controlled through being dependent on a stipend from their lord.Footnote 82 This process was consolidated by Tokugawa Ieyasu, who issued an edict in 1615 commanding ‘one domain, one castle’ (ikkoku ichijō), under which, as the name suggests, all domains were permitted to maintain only one castle, where the samurai were required to reside, and the other fortifications had to be destroyed.Footnote 83 Satsuma, however, was the exception to this rule. The domain was permitted to have 113 district seats, literally ‘outside castles’ (tojō, known as gō or ‘villages’ from 1784), in which rural samurai lived and which had a fortified dwelling (though not a castle after 1615) at their centre.Footnote 84 When tallies were taken in the nineteenth century, the ratio of samurai to commoner in Satsuma in 1871 was one to three, whereas in other areas of Japan the average ratio for the year 1873 was one to seventeen.Footnote 85 The outer castle system also meant that, rather than being concentrated in the castle town and thus more easily monitored as was the case in other domains, all the samurai in Satsuma except for around 5,000 who were clustered in the castle town of Kagoshima were dispersed across even the remotest parts of Satsuma.

The Shimazu undertook various strategies to mitigate the risk posed by having so many armed warriors dispersed throughout their territory, and the Naeshirogawa visits may be understood in this context. Like Japan's daimyo, who were required to divide their time between their domains and Edo, where their families resided under the watch of the shogunate, the stewards (jitō) of Satsuma's outer castle districts were required to reside with their families in the Satsuma castle town of Kagoshima and to visit their district seats periodically, while rural samurai and village elders administered the districts on their behalf. Like daimyo, who were moved between domains, the Satsuma stewards were moved between districts by the Satsuma administration, a tactic used to reduce threats to Shimazu authority by severing old local military ties between stewards and their traditional power bases.Footnote 86 The stewards responsible for the district in which Naeshirogawa was located, such as Umanosuke, the recipient of the watermelons noted above, were required to be present in the village when the daimyo visited, and to offer signs of submission in the form of gifts, which reinforced the steward's local authority, but also his vassalage under the ruling branch of the Shimazu family.

The late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, when the Naeshirogawa visits were established, was a particularly critical point for the Shimazu's hold on power. The period followed a series of events that had weakened the Shimazu regime financially and politically: a resounding military defeat at the hands of Toyotomi Hideyoshi and his allies in 1586–7, curtailing Shimazu territorial expansion in Kyushu; involvement and eventual defeat in the devastating Imjin War campaign against Choso˘n Korea between 1592 and 1598; and defeat at the battle of Sekigahara in 1600, during which the Shimazu had opposed the victor, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who went on to found the Tokugawa shogunate. The period during which alternate attendance visits to Naeshirogawa were established thus coincides with what Robert Sakai has dubbed the ‘consolidation of power’ in Satsuma domain between 1602 and 1638, during Shimazu Iehisa's tenure as daimyo.Footnote 87 Sakai showed how Iehisa exerted greater control over his territory through land surveys, reduction of debts within the domain finances, greater administrative control over the populace and the removal of threats to the Shimazu's reputation as wise and benevolent rulers. The public ritual activities that took place during Naeshirogawa visits may be understood as part of this process of consolidating Shimazu rule by stamping their territory with signs of dominance.

The foreign origins of Naeshirogawa's inhabitants and the successful importation of economically profitable industry that their ceramic production represented made the village particularly suitable for such articulations of authority. This was because, despite being one of the largest domains in Tokugawa Japan, Satsuma was agriculturally poor. The magnitude of domains during the Tokugawa period was calculated by reference to their official putative rice yield (omotedaka), which was measured using the unit of the koku (roughly equivalent to 5 bushels or 180 litres). With a value of 729,563 koku in 1634, Satsuma was the second largest domain. However, unlike other domains, the official rice yield of Satsuma lands was calculated in unhulled rather than hulled rice, meaning that the actual rice yield (jitsudaka) of Satsuma was comparatively low, reducing to about one-half of the official putative rice yield.Footnote 88 The reason for this low productivity was that the domain's territory was located within a pyroclastic plateau underlain by agglomerates, tephra and volcanic ashes that made the soil less productive than that of other parts of Japan. The region was also subject to typhoons, and was highly mountainous, both of which made it less agriculturally productive.Footnote 89 This meant the domain authorities had to maintain other sources of income, from piracy, trade, mining, fishing, and manual industries like Naeshirogawa ceramics, in order to ensure the prosperity of their territory and their security as rulers.

Over the centuries, the Shimazu had established trade and piratical networks within their local region, receiving cargo ships from China, Korea, the Ryukyu Islands, and further afield in Southeast Asia, functioning, in Tokunaga Kazunobu's words, as a ‘maritime nation’ (kaiyō kokka).Footnote 90 In addition, as Robert Hellyer has argued, Satsuma was one of two domains of Tokugawa Japan that were officially allowed significant leeway to conduct relations with foreign nations, in its case via control of the Ryukyuan kingdom (the other such domain, Tsushima, was responsible for trade with Korea), so that Satsuma could be described as an ‘independent partner’ of the Tokugawa when it came to international affairs.Footnote 91 This ability to command foreign peoples and to bring wealth into the domain from overseas was arguably one means by which the Shimazu family demonstrated locally its fitness to rule, and alternate attendance processions provided an opportunity to demonstrate this for the public gaze within their domain. In the first decade of the seventeenth century the domain was faced with financial losses caused by the Tokugawa crackdown on piracy in the Kyushu region, and in 1609 it annexed the Ryukyuan kingdom in order to regain an income from the Ryukyuan trade, which had links with China and Southeast Asia.Footnote 92 After pledging allegiance to the Shimazu, the defeated Ryukyuan monarch was permitted to return to Ryukyu in 1611, but from then on all Ryukyuan kings were required to leave high-ranking hostages, usually imperial princes, behind in a newly built facility in the Kagoshima castle town, the Ryūkyū kariya (Ryukyuan administrative headquarters), later known as the Ryūkyū kan (Ryukyuan compound), and to send representatives to Edo under Shimazu escort.Footnote 93 The Naeshirogawa potters provided another, albeit smaller, source of revenue and prestige, likewise drawn from Shimazu military exploits in their region, having been captured during the Imjin War, and on one occasion even travelled to Edo in the Satsuma alternate attendance entourage.Footnote 94 This enabled the Shimazu to extract value from what had actually been a military defeat in Korea, and is consistent with the fact that, during the mid-seventeenth century, the Shimazu's military defeat in the Imjin campaign was recast as a series of bold exploits, in war memoirs of surviving soldiers that had been commissioned by Satsuma domain authorities.Footnote 95 Thus, both the Ryukyuans and the Naeshirogawans were incorporated into Satsuma's domestic rituals, including alternate attendance, as a sign of their submission and Shimazu power in their region.

Concluding remarks

Alternate attendance, as practised within Satsuma domain, shares many characteristics with royal progresses elsewhere in world history. In the same manner that Geertz noted for the processions of Elizabeth I, Javanese sovereigns and Moroccan kings, alternate attendance travel in Satsuma clearly ‘located society's center’ in the daimyo ‘by stamping a territory with ritual signs of dominance’.Footnote 96 Moreover, as has been shown in studies of the progresses of Elizabeth I, and the royal entries by the monarchs of Valois France, alternate attendance visits not only functioned as a way to express daimyo authority, but also provided moments of negotiation and exchange between the daimyo and Naeshirogawa elites: the ceremonies of gift-giving, banqueting, dance and displays of local wares that took place during the visits made manifest Satsuma's reliance on the Naeshirogawa pottery industry, and the honours, financial and status-based, that were due to the village officials, and the village, as a result. Other points of comparison with royal progresses are deserving of further investigation.Footnote 97 The role of religion and cosmology in the Satsuma processions, for example, seems to have been a factor in the shrine visits on the first day of travel in Satsuma, as well as in the sacred Korean dances performed for the daimyo; however, in the absence of more detailed source material, it is difficult to ascertain if religion occupied as central a role in the ritual statements made by the Satsuma processions as it did in the more classic cases of royal progress in world history.

Nevertheless, understanding how daimyo acted as rulers with power akin to sovereigns in their own territories when it came to alternate attendance allows us to examine the ways in which – in the case of Satsuma, at least – they laid claim to local legitimacy, not through having been invested as rulers by the shogun, but by virtue of other claims to power that lay with themselves. The daimyo journeys add further evidence to the complicated picture of sovereignty in early modern Japan, in which a delicate balance of power between the shogun and his daimyo was expressed in dual regimes of meaning that operated interchangeably, depending on whether the context was external or internal matters. Just as the alternate attendance parades could function as markers of domain status in the eyes of observers outside the domain en route and in Edo, so too, as the processions passed through the domain of Satsuma, they were a visible reminder of local Shimazu claims to power, and were orchestrated to inspire awe, exert control and display the Shimazu ability to command ‘foreign’ captives and resources. Thus, although by the mid-seventeenth century most of the Naeshirogawa potters had been born in Japan, they were required to perform Korean-ness (or ‘Chosōn-ness’) and to show their loyalty to the descendants of those who had taken their parents and grandparents to the domain during the Imjin War.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the anonymous Transactions reviewers for their comments.

Financial support / Funding statement

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 758347).

Competing interests

None.

Author biography

Rebekah Clements is an ICREA research professor at the Department of Translation, Interpreting, and East Asian Studies at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. Her previous publications include A Cultural History of Translation in Early Modern Japan (Cambridge University Press, 2015); ‘Brush Talk as the “Lingua Franca” of East Asian Diplomacy in Japanese–Korean Encounters, c.1600–1868’, Historical Journal, vol. 62, issue 2, June 2019, pp. 289–309; and ‘Speaking in Tongues? Daimyo, Zen Monks, and Spoken Chinese in Japan, 1661–1711’, Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 76, issue 3, August 2017, pp. 603–26.