The export of arms from interwar Czechoslovakia is an interesting and significant phenomenon, whose further research provides a considerable challenge for future researchers—in spite of the fact that this issue has been addressed exhaustively by several authors. Unfortunately, the investigation of this issue is complicated by several factors that may have led to inaccurate data being recorded. Arms manufacturing was naturally a very specific branch of Czechoslovak industry in many aspects and, together with arms exports, also a highly sensitive political issue. Czechoslovakia, like many other countries, was rather reluctant to provide detailed information regarding the results and structure of the Czechoslovak arms industry, its possibilities, and future plans on the world stage. Such an unwillingness to accurately record data, among other things, was manifest in the compilation of official statistical overviews. A similar situation also occurred during the monitoring of Czechoslovak arms exports. Given the extreme political sensitivity of some arms sales or the business strategy of the arms business, these transactions remained essentially concealed and were not included in the statistics that Czechoslovakia submitted to the international community.Footnote 1 The effort at secrecy is clear not only from the absence of some data and the existence of some irregularities in the official statistical overviews, but also from the content of the relevant documents in the archives of the individual arms manufacturers.

As far as the published sources are concerned, an initial consideration must go to the statistical reports focusing on foreign trade that were published by the State Statistical Office in Prague. However, these reports clearly do not include the data for all arms exports—regardless of whether the explanation for this absence is a lack of interest on the part of the individual companies in publicly presenting these transactions, or the fact that they were highly controversial and sensitive from the perspective of foreign relations, or for some other reason. The export of arms and their share of total Czechoslovak exports were obviously many times higher than what was stated in the official statistics. Moreover, the available materials of the State Statistical Office mostly state the total value and not the specific quantity of individual items. Such information has questionable informative value due to changing prices and development of the exchange rate of the Czechoslovak crown, among other things. In the case of Czechoslovak statistics, the figures relating to arms production are often hidden under any of the general categories of iron products. Another problematic area is the export of military vehicles, which, if included at all, appears in the statistics under the general “various vehicles” category. A similar situation also exists in the case of aircraft and aircraft components, where it is necessary to base judgments on the data provided by the manufacturers themselves since the data in the overall Czechoslovak statistics are combined with civil production, particularly sports aircraft, whose export in the 1930s was also significant. The statistics gathered by the State Statistical Office must in any case be compared with and supplemented by data from other sources, particularly documentation from the archives of the individual enterprises. These archives are, however, often incomplete for several reasons—destruction caused by wartime bombing or, for instance, shredding in the post-war period. Moreover, some of the relevant archival records have not been processed yet; their content is unknown and thus they are factually inaccessible to the public. Information about the largest manufacturer of weapons in interwar Czechoslovakia—Škoda Works—can be drawn from the extensive archive of Škoda, or from the personal collection of Vladimír Karlický, who was devoted for a long time to the history of Škoda Works. This collection has yet to be processed to date, however.

At the same time, it is actually the corporate archives, in this case the Škoda archive, which provide the most interesting information about these arms transactions and especially their background, which is usually documented by extensive correspondence between the representative offices in the individual countries and the Czechoslovak manufacturer. It is also possible to discover officially secret reasons for the transactions in the correspondence and, in some cases, to identify the real buyers of the export products.Footnote 2 In addition, the reports from the representative offices often provided information about the procedure for selecting suppliers in the given countries along with some guidance on how to increase Škoda Works’ chances of success in the market. Thus, these documents are an important source of supplementary information to the statistics and contracts.

Škoda Works, whose name was changed several times during the twentieth century, was one of the most significant industrial companies in the history of the independent state of Czechoslovakia. Founded in the era of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the second half of the nineteenth century, Škoda Works gradually expanded production, which in the interwar period included not only arms production but also the production of machinery and means of transport (locomotives, motor vehicles, and aircraft). The company also owned mines that produced the raw materials used in production, as well as other plants related to the manufacture of Škoda Works’ major products. For Germany, Škoda Works was an important member of the Reichswerke Hermann Göring group during the German occupation. At the end of the war, Škoda Works was damaged by the air bombing of Pilsen.

After the war, the former Škoda Works was nationalized and separated into several units according to manufacturing focus. Nevertheless, from a national perspective and within the scope of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, it remained a key heavy engineering firm for the duration of the communist regime in Czechoslovakia (1948–89). In compliance with socialist planning, however, arms manufacturing was relocated from the Pilsen factory primarily to plants in Slovakia.Footnote 3 It was only after the fall of the communist regime in Czechoslovakia that Škoda Works was privatized and divided into a number of smaller companies.Footnote 4 Given these facts, the significance of this firm for business history, within the contexts of both Czechoslovakia and the international economy, is thus indisputable. This study focuses directly on arms exports carried out by the Škoda company arms divisions and excludes the exports of other companies belonging to the Škoda Works group, such as the aircraft manufacturer Avia.

Czechoslovak Arms Export in the Interwar Period

In the interwar period, Czechoslovakia ranked among the most significant exporters of arms and armaments. These were delivered to many countries, where Czechoslovak arms companies usually had permanent representative offices with contacts in political and military circles. The most important importers of Czechoslovak arms were the alliance countries of the Little Entente (Romania and Yugoslavia). With the increasing influence of Germany, including in the Baltic states, Czechoslovak arms enterprises faced increasing competition and rival products from Germany in these countries. The more significant target markets for Czechoslovak arms exports also included the countries of Latin America, the aforementioned Baltic states, and even China. Sales in exotic non-European markets such as China were often a better economic prospect than sales within Europe because the high risk (and costs) related to these transactions was often more than adequately offset by the higher selling prices of the arms. In the second half of the 1930s, trade with the USSR began to develop, however, this was to a large extent focused on the exchange of licences and technologies. The primary territorial focus of arms exports was thus substantially different from the territorial structure of total Czechoslovak exports, most of which in the 1930s continued to be targeted at neighboring countries (Austria, Hungary, Romania, Poland) and Yugoslavia. In this context, arms exports seemed to be a means to the greater territorial diversification of Czechoslovak exports.

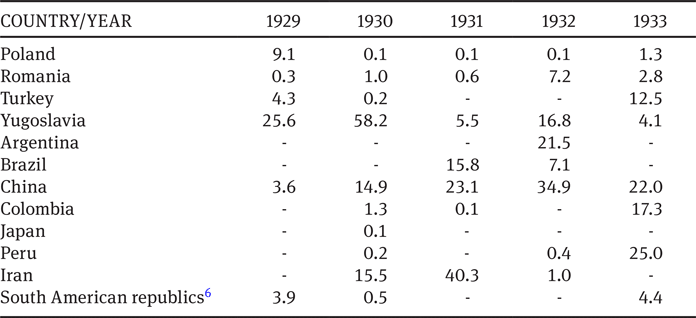

Czechoslovak arms producers, including Škoda Works, started exporting large volumes of arms in the second half of the 1920s. In its statistical reports for the period 1929–33 (with the exception of 1932), the League of Nations valued annual Czechoslovak arms exports at over CSK 100 million and for 1930 at more than CSK 177 million.Footnote 7 Some of the sources present Czechoslovakia as the second largest arms exporter in the world as early as the beginning of the 1930s.Footnote 8 The major expansion in Czechoslovak arms exports came during the period of the “armaments boom” in the second half of the 1930s, when, according to Czechoslovak statistical data, arms exports increased several-fold. The transition from the years of recession to the period of the armaments boom in the mid-1930s was really quite aggressive. While Czechoslovak exports expressed in current prices in 1935 were about 7.5% higher when compared to their value in 1932; the export of arms and ammunition at current prices and the share of arms and ammunition in total Czechoslovak exports in the same period (1932–35) increased more than eight-fold. In 1938, the export of arms and ammunition amounted to almost 7% of total Czechoslovak exports (for details, see Table 1). As already indicated, the real share of arms in Czechoslovak total exports was in fact substantially higher than the data gathered from official Czechoslovak statistics. Exports also ensured the inflow of foreign exchange. In the 1930s, more than 50% of the products of most arms enterprises were usually exported, including those of Škoda Works. The exception was aviation production, where exports amounted to only about 5% of production.Footnote 9 In the difficult period of the 1930s, the manufacturing and export of arms became one of the major factors that positively affected the results of Czechoslovak foreign trade and, in fact, the entire Czechoslovak economy.

Table 1. Arms exports from Czechoslovakia according to statistics of the League of Nations, 1929–1933 by territory (% of total quantity)Footnote 5

According to some estimates, Czechoslovakia's arms exports in the second half of the 1930s amounted to almost a quarter of global exports, and in 1934 and 1935 it was probably the largest arms exporter in the world.Footnote 10 This primacy was due not only to the quality of Czechoslovak arms but also—to a certain extent—to the absence of stronger competition on the world market. Of some significance was also the fact that advanced countries either focused mainly on the militarization of their own armies or did not consider it politically advantageous to become increasingly involved in global arms trading, among other reasons.Footnote 11 Naturally, the phenomenon of growing arms exports must at the same time be evaluated in the broader context of the development of the Czechoslovak arms industry in the 1930s, which was stimulated by the large volume of state orders related to the rearmament of the armies.

Table 2. Czechoslovak export of firearms and ammunition in the period 1921–38 (export in millions of CSK, percentage share).Footnote 12

On the other hand, the export of arms from Czechoslovakia also had its dark, controversial aspects. A naturally disputable issue was the moral aspect of arms exports, as well as the higher risk of potentially unfavorable political affects. The export of arms also de facto saturated the production capacity, which was required at the end of the 1930s for the rearmament of the country's own army. A special chapter was the export of arms to the countries of the Little Entente, which was to a great extent initiated by political-military factors. In principle, these exports did not benefit Czechoslovakia from an economic standpoint. Arms deliveries to the Little Entente countries were thus a highly specific part of Czechoslovak arms exports, and in many respects they differed from arms exports to other significant destinations. The Czechoslovak government had a strong interest in delivering arms to its allies in the Little Entente: they greatly desired that the Romanian and Yugoslav armies should be equipped mainly with Czechoslovak arms.

The successful development of similar transactions was hindered by some obvious obstacles, however. Czechoslovak arms manufacturers were compelled in the interwar period to face increasing competition in the Balkans. Romania and Yugoslavia were repeatedly afflicted by a shortage of foreign exchange for the purchase of arms from abroad. Moreover, it was clear by the 1930s that Romania in particular, with regard to its long-term perspective, would prefer domestic production (for instance, building arms enterprises with the aid of significant foreign arms manufacturers) rather than the import of arms. Among other factors, the issue of agrarian exports from Romania and Yugoslavia to Czechoslovakia also played a role. Romania and Yugoslavia demanded that the larger volume of arms purchases from Czechoslovakia be “offset” by larger agrarian imports from these countries to Czechoslovakia.

One of the consequences of these circumstances was the Czechoslovak government's extensive support for domestic arms manufacturers in order to export to the countries of the Little Entente—regardless of whether this concerned the promotion of Czechoslovak arms, export guarantees, or direct grants. Yugoslavia and Romania repeatedly compelled Czechoslovakia to make many concessions and accept trading terms that were highly unfavorable to Czechoslovakia. Despite these concessions, many contracts were not implemented in their initially planned form.Footnote 13

Škoda's Arms Exports in the Interwar Period

Many enterprises exported arms from Czechoslovakia. From the viewpoint of quantitative statistics, however, Czechoslovak arms exports were effectively controlled by two companies: Škoda Works and Zbrojovka Brno (Czechoslovak Arms Factory of Brno).Footnote 14 Škoda, the traditional arms manufacturer in the era of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, faced a lot of problems, which were to a great extent naturally related to the difficult conversion of part of the arms program to “peacetime” production and excessive production capacities originally set for the former Austro-Hungarian market.

The major problems of Škoda constituted one of the main reasons for an ownership change in this most significant Czechoslovak engineering enterprise. In September 1919, the French company Schneider et Cie became the majority owner of Škoda.Footnote 15 The merger with a strong French group and, among other things, a significant link with the Czechoslovak political elite made it possible for Škoda to overcome the consequences of the recession and become a strong and stable enterprise again.Footnote 16

The arms production of Škoda also played a strong role in its strengthening. Škoda Works focused mainly on heavy arms—the manufacture of artillery guns and ammunition. In spite of all the personnel, ownership, and other changes, Škoda successfully maintained its high-quality arms production. It also benefited from the general increase in the importance of artillery in the military thinking of advanced countries.Footnote 17 The Czechoslovak Army was certainly the major buyer of arms from Škoda during the entire interwar period. The requirements of the Czechoslovak Army also had a great influence on the program, as well as the overall concept of arms production at Škoda, which gradually expanded during the interwar period. After the first few years, when the main objective was primarily to stabilize the entire enterprise, Škoda began arms research and development in earnest from the mid-1930s, and this soon resulted in up-to-date products of higher quality. At the beginning of the 1930s, this generally positive development was disrupted by fluctuations caused by the Great Depression, when the share of arms production also fell (to almost one-fifth of the total production in 1932).Footnote 18 As early as 1933 this trend reversed, and in 1934 Škoda experienced a substantial “armaments boom” that lasted until 1938.Footnote 19 The higher profit rate of armaments production, as compared with the other products of the Pilsen company, was an important catalyst behind this development.Footnote 20 Concerning Škoda's extensive product portfolio, it is worth mentioning the high quality anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns, mortars, and the bunker artillery gun. Škoda also manufactured tanks and armored vehicles, and was also partially involved in the manufacture of small firearms.Footnote 21

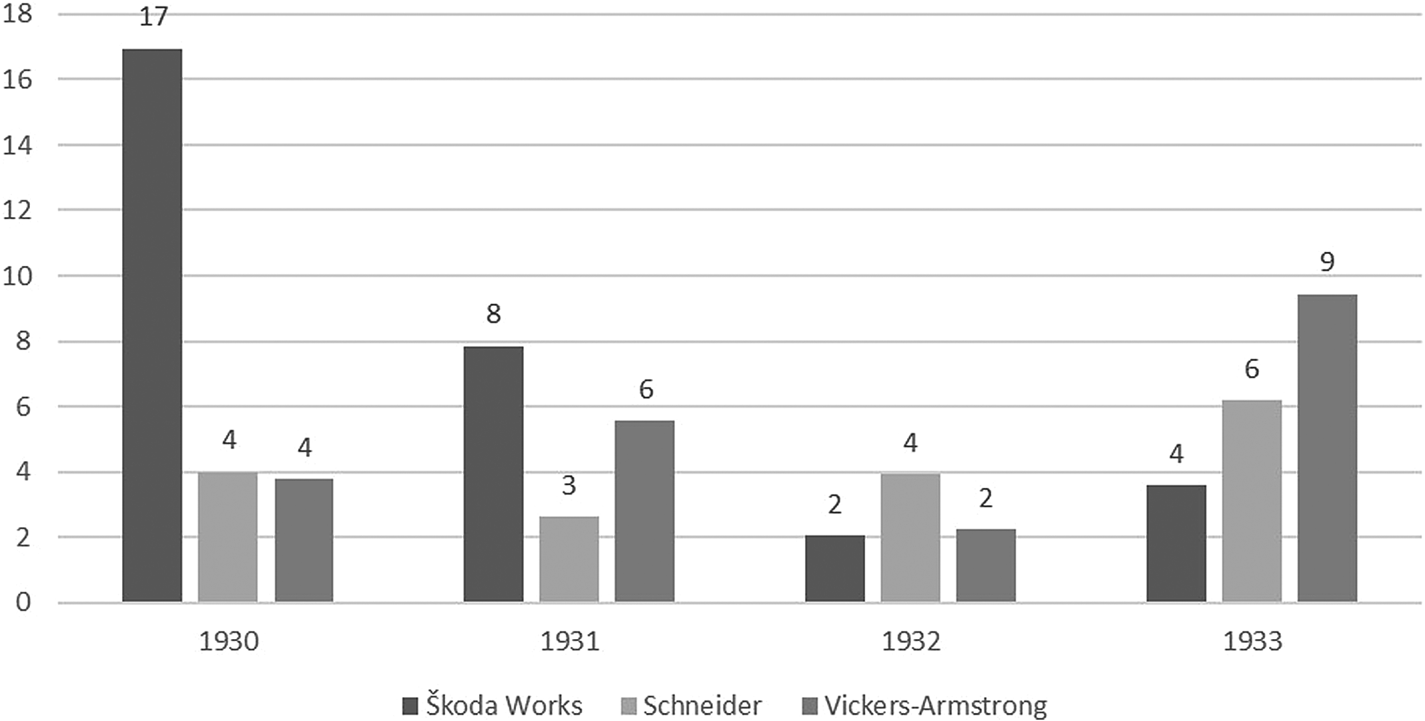

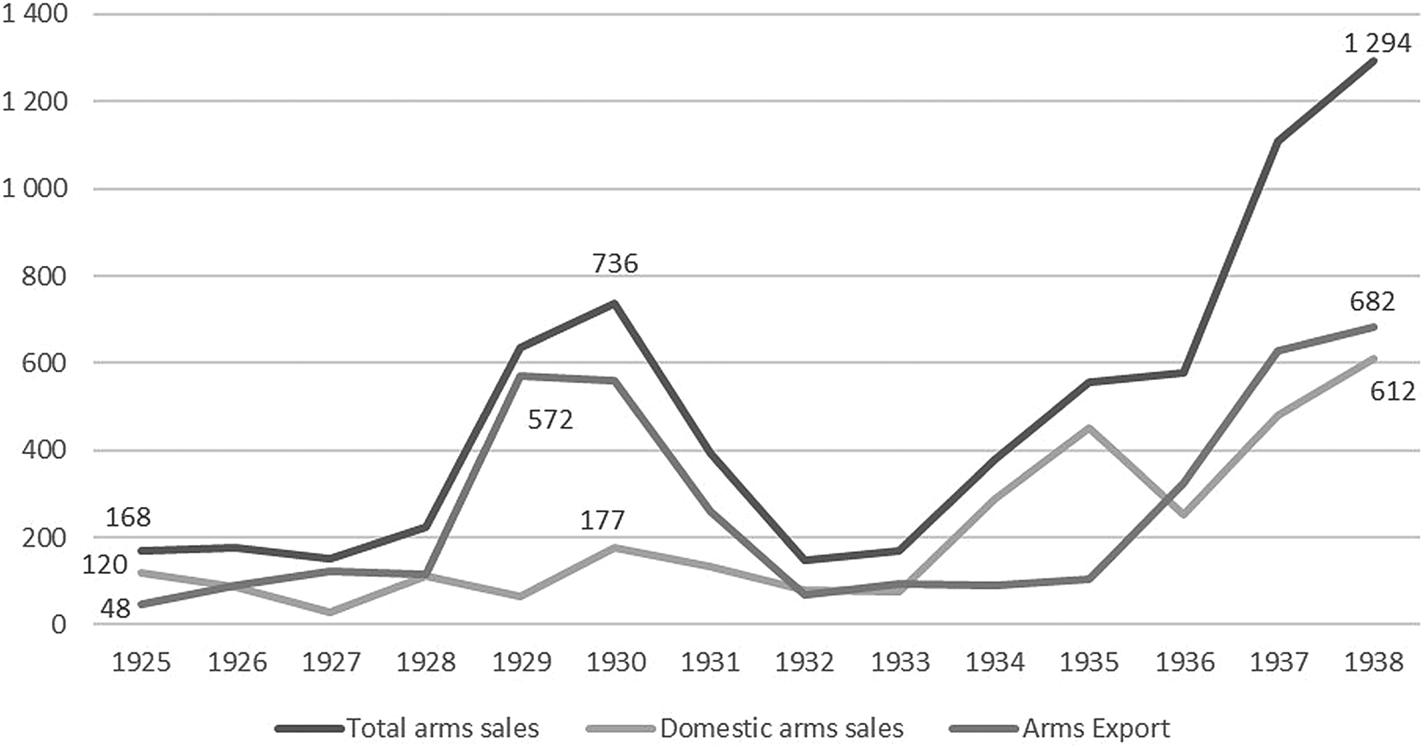

As already stated, in the interwar period Škoda Works focused mainly on deliveries to the Czechoslovak Army. On the other hand, orders from the army could clearly not fully exploit the armaments production capacity of Škoda (which was set for the former Austro-Hungarian market), and the export of armaments was thus an irreplaceable component of sales. Part of the Škoda product range, such as mountain and marine artillery guns, was targeted exclusively at foreign customers since the Czechoslovak Army logically had very little or no interest in these items due to geographic conditions. About half of Škoda's total artillery gun sales in the interwar period accrued to exports. The main buyers were Yugoslavia, Romania, Iran, and Turkey. Although China was one of the markets to which large deliveries of Czechoslovak arms were made in the 1930s (particularly those made by Zbrojovka Brno), Škoda Works failed here. The importance of Škoda's exports is illustrated by a comparison with other large arms companies in Europe—French Schneider et Cie and British Vickers-Armstrong (see Figure 1). At the beginning of the 1930s, Škoda exported more than the above-mentioned arms companies. In 1930, Škoda's exports reached $17 million, while the exports of the other two companies were only about $4 million.Footnote 22 In the following years, there was also a decline in exports of Škoda Works in connection with the economic crisis, but in the second half of the 1930s, exports multiplied as compared to 1930 (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Comparison of the arms exports of Škoda Works, Schneider et Cie and Vickers-Armstrong in the period 1930–1933 (in millions of USD).Footnote 23

Škoda Works exports were restricted by an agreement between Škoda Works and their French shareholder, Schneider et Cie, which defined the territorial distribution of the export market between these two entities (who were in many cases competitors for contracts abroad) along with financial bonuses for exports in favor of the other company.

Figure 2. Invoiced arms sales of Škoda Works in the period 1925–1938 (in millions of CSK).Footnote 24

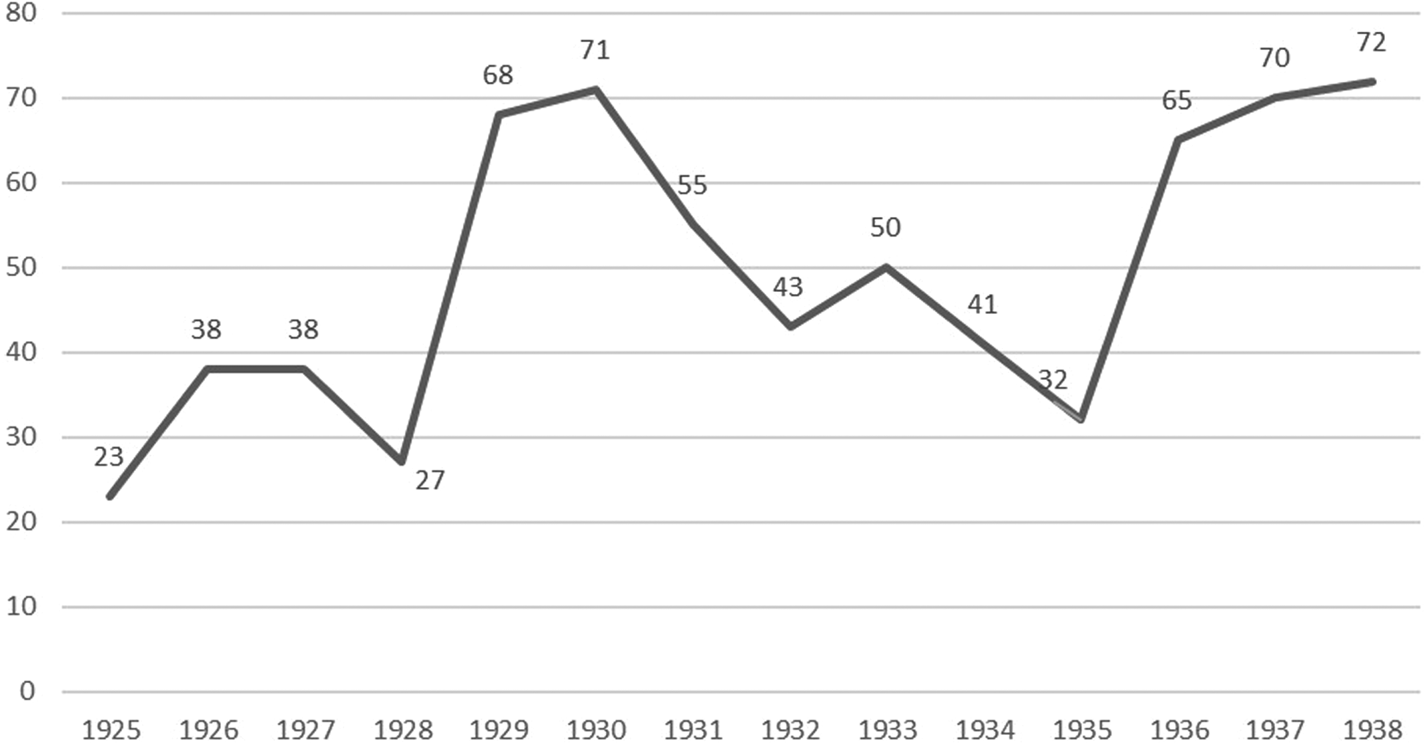

The armaments exports of Škoda enjoyed a boom mainly in the second half of the 1920s and the second half of the 1930s (see Figure 2). This is precisely the period of Škoda's substantial expansion, when the share of armaments production increased discernibly in relation to the Škoda's total invoiced exports (for a detailed ratio of arms production to total invoiced Škoda exports, see Figure 3). In 1929, the armaments share of total invoiced Škoda exports was more than two-thirds, and in the dramatic year of 1938, it was as much as 72%. Arms exports in this period were clearly a stimulus for the overall development of the enterprise, in spite of the fact that the share of arms production in the given period (1929 and 1938) was “only” about one-third of total Škoda sales.Footnote 26 Figure 2 also shows the changing position of the exports of the Pilsen enterprise. From the presented data, it follows among other things that the share of exports in the enterprise's sales performance played the greatest role at the beginning of the 1930s, while in later years the situation changed. For instance, there was a general increase in customs barriers and a real foreign exchange deficiency among the foreign buyers. The second half of the 1930s was a period of obvious growth in both domestic and foreign sales.

Figure 3. The ratio of arms production to the total invoiced exports of Škoda Works (as a percentage).Footnote 25

In January 1936, Škoda Works and another significant Czechoslovak arms manufacturer, Zbrojovka Brno, signed an agreement to share a production program until 1945, which also defined, among other things, the export options of both companies. Zbrojovka Brno undertook not to manufacture artillery material of any caliber larger than 25 mm. On the other hand, Škoda Works promised that for the duration of the agreement they would not manufacture military material up to a caliber of 25 mm. For exports, according to the agreement it thus stipulated that: “For foreign operations, the parties would not hinder each other, where one of them would not benefit from the restriction of freedom of the other party according to the circumstances of a given case.”Footnote 29 In practice, this agreement prevented competition between both parties with regard to similar products.

After the Nazi occupation of the Czechoslovak border in the autumn of 1938, there were efforts to negotiate new exports (for example deliveries to Germany or Italy).Footnote 30 Due to rapid political developments, in principle these issues remained inconsequential for Czechoslovak representatives, and further development was based on the decision of the German administration. In March 1939, this administration supported exports based on orders to approved countries, as well as new orders mainly for the purpose of obtaining foreign exchange.

Škoda's Exports to Romania and Yugoslavia

The major target markets for Škoda Works armaments exports in the 1930s included the Little Entente countries. Škoda Works mainly supplied artillery to Romania and Yugoslavia. A strong competitor, not only for Škoda Works but for Czechoslovak companies in the Little Entente countries in general, was Germany, which unlike Czechoslovakia purchased enough agricultural products to realistically “cover exports.” Part of Germany's exports to Romania and Yugoslavia also consisted of reparations (in 1930 it was almost 41% of exports to Yugoslavia and 21% to Romania), but this part of exports created additional trade opportunities.Footnote 31 In its plans, the German government took into account the effects of the economic crisis on these countries and provided them with grain preferences to ensure continued trade and increase their dependence on Germany.Footnote 32 Moreover, Germany wanted to replace the influence of France and Italy, which were also interested in the region.Footnote 33 On the other hand, Czechoslovak companies accumulated claims against Romania and Yugoslavia, whose payment proved to be substantially problematic. Germany benefited from this situation, as Romania and Yugoslavia were compelled to compensate it for these high exports by importing German products, and this interdependence gradually increased.Footnote 34 Germany was increasingly more successful in the Balkan states and in central Europe. In 1924, German exports to these regions, including Austria, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and Greece, were 26.4% lower than Czechoslovak exports, but by 1939 German exports were 25% higher.Footnote 35 For political reasons, support for German exports in the form of loans was even more generous than in Czechoslovakia. The successes of Germany in Romania and Yugoslavia were moreover supported by price dumping, free convertibility of the Reichsmark in both countries, and a broad network of representative offices.Footnote 36

In the 1920s, in both cited markets, namely Romania and Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia was the leader in terms of arms supplies, which was due in part to efforts to unify the armaments of the Little Entente's armies. The deliveries were made on a loan basis, but the negotiation of these loans was challenging. Subsequently, that is for most of the 1930s, Czechoslovak arms producers successfully maintained their significant role in the arms imports of Yugoslavia and Romania. Czechoslovak enterprises did not show much interest in the establishment of plants in Yugoslavia and Romania, due to their workload as well as to better alternative export options. In spite of this, they made an effort to intervene in construction tenders in order to maintain Czechoslovakia's position, usually unsuccessfully. At the same time, German influence in the area of constructing arms plants was no more significantly established. For Czechoslovak enterprises, however, the overall industrialization of Yugoslavia and Romania with the aid of Germany was a situation that interfered with their business interests, serving as a complication with broader implications.Footnote 37

Competition for tenders with other Czechoslovak arms companies, however, was not a rarity. Based on a December 1934 cartel agreement between ČKD and Škoda Works, under which the companies shared the supply of tanks to the Czechoslovak Army, a 1936 amendment added the objective of sharing deliveries to Romania and Yugoslavia. The amendment established the deliveries in the ratio 60% of the total volume for Škoda Works and 40% for ČKD.Footnote 38

Exports to Romania were restricted from April 6, 1934 by the regulation of payments between Czechoslovakia and Romania, which stipulated that payment for all exports would be carried out through private payment compensation.Footnote 39 In the preceding period, payments for exports had been realized through a clearing account.Footnote 40 In October of the same year, imports and payments into and out of Romania were again re-regulated, such that imports into Romania were carried out only if the supplier had obtained import certificates in an amount equivalent to the value of the goods (these certificates were issued on the basis of imports from Romania).Footnote 41

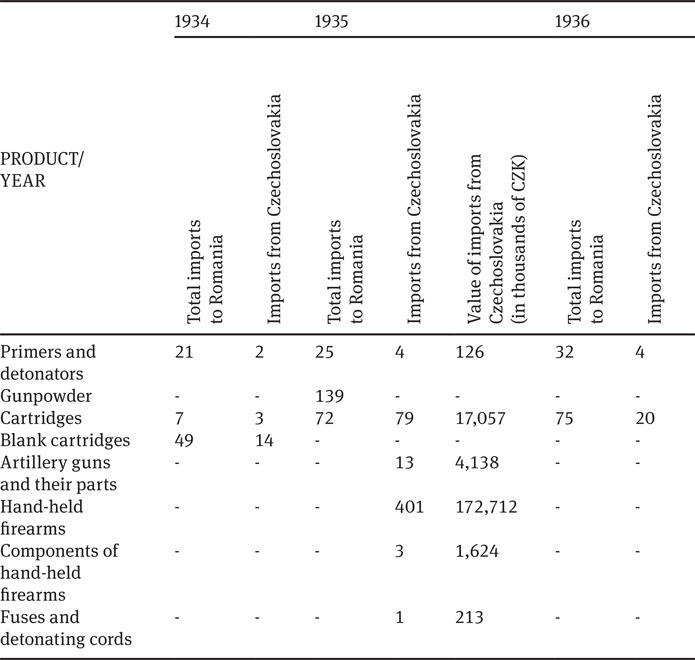

Table 3. Imports of arms into Romania in the period 1934–1936 according to the individual products (in tons).Footnote 27

Along with artillery materials, Romania also purchased tanks and other military vehicles from Škoda Works. One of the critical moments in their business relations was a dispute about the validity of a delivery contract from 1930 that Škoda Works concluded with the Romanian Ministry of War, and on which the Romanian side stopped paying instalments. Attempts aimed towards a diplomatic resolution of the dispute in 1935 led to the determination of new business cooperation conditions. Škoda Works was to have supplied goods to Romania, which were mainly supposed to be military materials worth about 600 million CSK.Footnote 42 The new cooperation also successfully calmed the situation after the so-called Seletzki Affair.Footnote 43

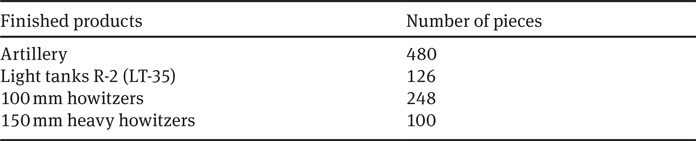

During the 1930s, Škoda Works and Romania concluded many arms supply contracts. In the case of arms, this mainly concerned large orders from 1930, 1931, 1935, and 1937. In the first mentioned years, there were orders for ammunition, detonators, or adaption of field artillery guns.Footnote 44 A further order was received by Škoda Works in April 1935, when a contract was signed for the delivery of 20 batteries of 100 mm howitzers (M.30) and 42 batteries of 100 mm howitzers (M.34), both including ammunition, along with 45 batteries of 150 mm howitzers, including ammunition. The total price for the delivery including the license was 608,710,052 CSK.

Apart from the military administration, the Romanian Aviation and Naval Ministry also placed orders with Škoda Works, which also supplied machinery for arms factories to Romania, and smaller orders that also came in through Schneider et Cie, the French shareholder in Škoda Works.Footnote 45

In addition to the above-stated items (especially the artillery materials), Škoda Works successfully sold a light tank in Romania, which was designated in Czechoslovakia as the LT-35. It became a major component of the armaments of the Romanian Army in battles against the USSR and worked alongside a broad range of military vehicles. In 1936, the Romanian Ministry of Armaments ordered 126 light LT-35 tanks in two versions, worth a total of 96,732,090 CSK.Footnote 46 Military vehicles were also an important export item: in 1937 an order for these vehicles exceeding 300 million CSK was concluded with Romania.Footnote 47

Table 4. Export of major Škoda Works products to Romania in the 1930s (up to March 15, 1939).Footnote 28

Just as in the case of Romania, the major Czechoslovak arms supplier to Yugoslavia was Škoda Works. From 1918, they supplied almost all the artillery and ammunition to Yugoslavia. In the period 1929–1930, the value of these deliveries was 1,488,665,000 CSK, which was more than 70% of all Škoda Works exports in the period 1918–1930. The export of Škoda Works arms to Yugoslavia did not appear in the official foreign trade statistics because the products were supplied under hidden state loans, within which the claims of the Czechoslovak state were paid through tobacco supplies.Footnote 48 In the 1930s, the export situation of Škoda Works began to be significantly affected by the foreign policy and internal political events in Yugoslavia. Škoda Works, which until then had maintained its position through a representative of the group and the many rewards, commissions, and gifts provided for government officials in Yugoslavia, started losing its position.Footnote 49 A further reason was the already cited convergence of Yugoslavia and Germany, which de facto had an interest in the disintegration of the Little Entente. Of the orders made by the Yugoslav military administration to Škoda Works, the most interesting in terms of financial aspects were those that were implemented in the second half of the 1930s. Nevertheless, in the first half of this decade, brisk trade (mainly air bombs and military vehicles) was already in progress between Škoda Works and Yugoslavia of value in millions of CSK.Footnote 50

In June 1935, under a new decree the Ministry of National Defense took over the guarantee for the delivery of military materials from Škoda Works to the Yugoslav military administration, up to a limit of 700 million CSK.Footnote 51 Thus, a credit facility of 700 million CSK could be agreed upon between Škoda Works and the Yugoslav side for a period of nine years.Footnote 52

Two large orders from the Yugoslav administration followed in the same year. The contracts for these orders were signed on December 15, 1935. The first contract covered the delivery of nine batteries of 75 mm artillery guns, six batteries of 80 mm Flak artillery guns, and a large amount of ammunition and accessories.Footnote 53 The total value of the contract was 108,667,480 CSK.Footnote 54 The second contract signed on the same day was for war materials worth 337,150,961 CSK.Footnote 55 This specifically concerned the delivery of twelve batteries of 150 mm field artillery guns, including motor vehicles, six batteries of 105 mm artillery guns also with motor vehicles, fifty batteries of 47 mm anti-tank guns, and another large amount of ammunition and accessories.Footnote 56 A further contract of similar value followed in March 1936, when Yugoslavia agreed with Škoda Works on the supply of two batteries of 80 mm Flak guns and ammunition. The value of this order was 57,684,510 CSK.Footnote 57 Škoda Works again received a larger order in July 1936 when the company signed a contract with Yugoslavia for the supply of eight tanks with 37.2 mm guns and armor-piercing and impact-type grenades, nineteen batteries of 47 mm guns with armor-piercing and impact grenades, test ammunition and accessories. Under this contract, the total amount paid by Yugoslavia was 55,348,836 CSK.Footnote 58 Apart from the supply of the above-stated tanks, in 1936 Škoda Works received an order for various military vehicles in the amount of 71,703,958.50 CSK.Footnote 59 In the following years, orders for military vehicles were low, only in the millions of CSK.Footnote 60 In the case of Yugoslavia, a further business partner for Škoda Works was the Navy, whose orders amounted to tens of millions of CSK.Footnote 61

In 1937 Škoda Works experienced escalating competition in the battle for the Yugoslav market. The Consortium of Czechoslovak Banks objected to a loan for Yugoslavia, and German pressure in Yugoslavia also increased, which was obvious, for instance, from the recommendation to assign orders to Italian companies affiliated with the German I.G. Farben concern.Footnote 62 In September 1938, supplies were temporarily suspended due to the events in Czechoslovakia; nevertheless, they were renewed later after establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, this time under the influence of German capital.Footnote 63 Prior to the establishment of the Protectorate, the payment terms complicated trade not only for Škoda Works but also for Zbrojovka Brno. For example, there was an offer for the anti-aircraft gun Škoda R3, for which the Yugoslavs demanded a long-term loan but the Czechoslovaks proposed payment in foreign exchange over a shorter period. The situation was similar in the case of a Zbrojovka Brno contract valued at about 200 million dinars. Moreover, both companies faced the above-mentioned German competition, which was capable of offering better supply conditions.Footnote 64

Further trading was disrupted by the break-up of Czechoslovakia and the declaration of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in mid-March 1939. Based on Germany's relations with Škoda Works’ individual trading partners, arms trading was either renewed or terminated after the establishment of the Protectorate. Škoda Works, along with all industry in the Protectorate, was integrated into the German war economy (Škoda Works was specifically integrated into the Reichswerke Hermann Göring group) and fully used as one of the most important manufacturers of military hardware for Germany and its allies until the end of the Second World War.

The development of Czechoslovak arms production and export in the interwar period was influenced by many political, military, and economic circumstances. The boom in the second half of the 1920s was slowed by the economic crisis at the beginning of the 1930s; these impacts, however, obviously differed from the development in most other industrial branches. The political situation in central Europe ensured the quick recovery of the arms industry, and not just in Czechoslovakia. On a global scale, arms production recovered more quickly from the Great Depression as compared to peacetime production.Footnote 65 The positive development of arms production helped Czechoslovakia overcome the economic crisis and also partially improved the results of Czechoslovak exports, which were very negatively affected by the crisis. From 1934, one can again talk about an arms boom, which ended only upon occupation of the borderlands in autumn 1938.

Škoda Works, one of the two largest manufacturers and exporters of military materials in Czechoslovakia, also benefited from the armaments boom. Škoda Works maintained the strong position it held during the Austro-Hungarian empire and successfully built on it in the 1920s with new technologies, which ensured the sale of Škoda Works products from the end of the 1920s through the entire period of the 1930s. The economic crisis resulted in a decline in the ratio of arms production to total production; nevertheless, as early as 1934 Škoda Works again experienced a boom in arms production. The original focus of Škoda Works on the larger Austro-Hungarian market meant that the Czechoslovak Army could not absorb all the production and therefore a large part was set for export. The strong export position of Škoda Works in the early 1930s was also shown by comparisons with other large European arms producers (Schneider et Cie, Vickers-Armstrong), with which Škoda Works could compare in terms of exports in the early 1930s, even surpassing them some years.

The most significant foreign trading partners of Škoda Works were the Little Entente countries—Yugoslavia and Romania, followed by Turkey and Iran, though there were others. Škoda Works achieved success in the export of artillery materials (field artillery guns, anti-aircraft guns, howitzers), along with the light tank LT-35, military vehicles, and other products.

The position of Škoda Works in the buyers’ countries and their trade with those countries were influenced by political as well as economic factors. In the Little Entente countries, for example, political interests were preferred over economic ones. The above-mentioned factors need to be taken into account when evaluating the arms trade at any time. It is not possible to look only at the figures given by statistics (whether national or international), but it is necessary to consider the political environment, including political support for exports to selected countries (such as the support of Škoda Works’ exports to the states of the Little Entente or the support of the export of Germany to these states in order to gain influence) and the impact of international relations on trade.

The arms boom of the second half of the 1930s in Czechoslovakia should not be perceived as an exclusively positive phenomenon for the economy. It is also necessary to realize the controversial aspects of this phenomenon. Given the provision of direct state support for arms manufacturers, and also other circumstances, it is necessary to analyze the development of the arms industry within the broader context of the issue of military expenditures. Rising military expenditures in the second half of the 1930s naturally affected many sectors that were not directly linked to the manufacturing of military materials and the construction of military objects. On a broader scale, high military expenditures logically had impact on the entire Czechoslovak economy. Although the positive effects of high military expenditures on the Czechoslovak economy were obviously predominant in the second half of the 1930s, there also existed a real risk that over the long term this exceptional burden would instead become the cause of many economic problems. In light of later events (the Munich Agreement, the disintegration of Czechoslovakia, the establishment of the Protectorate, the outbreak of World War II) one can only debate the potential consequences for the peacetime Czechoslovak economy over a longer-term perspective.Footnote 66

Due to the significance of arms production and the importance of Škoda Works, not only nationally but internationally, research in this field is an important component of the economic and business history of Czechoslovakia and central Europe. For interested foreign parties, access to research has added value because most of the materials concerning the issue, particularly those in the Škoda archive, are in the Czech language and have not yet been digitized. Given the size of the archive, this will not change in the near future.

Moreover, Škoda Works is not a firm of marginal historical significance. Since its establishment in the nineteenth century, it has built a reputation as the biggest arms and engineering products manufacturer, first in the Austro-Hungarian empire and later in the independent state of Czechoslovakia.