Introduction

The plant communities in fire-prone ecosystems are largely affected by fire, making the understanding of its effects imperative for the study of the communities (Bond and Keeley, Reference Bond and Keeley2005). In the Brazilian Cerrado, a Neotropical savanna, adaptations to fire date from 9.8 to 0.4 Mya (million years ago) (Simon et al., Reference Simon, Grether, Queiroz, Skema, Pennington and Hughes2009). The vegetation in this biome presents numerous fire adaptations, such as high resprouting capacity, thermal insulation by a thick bark and synchronous flowering after burns (Neves and Damasceno-Junior, Reference Neves and Damasceno-Junior2011; Dantas and Pausas, Reference Dantas and Pausas2013; Pausas et al., Reference Pausas, Lamont, Paula, Appezzato-da-Glória and Fidelis2018; Pilon et al., Reference Pilon, Hoffmann, Abreu and Durigan2018). Despite the possible negative impacts of fire, burned areas represent new establishment opportunities for the surviving organisms and seedling recruitment due to the nutrient input and alleviated interplant competition (Miranda and Klink, Reference Miranda, Klink, Miranda, Saito and Dias1996a,Reference Miranda, Klink, Miranda, Saito and Diasb; Lamont and Downes, Reference Lamont and Downes2011; Musso et al., Reference Musso, Miranda, Aires, Bastos, Soares and Loureiro2015). Although vegetative reproduction is prevalent in the Cerrado, seed reproduction is also important for the persistence of species in fire-prone ecosystems (Pilon et al., Reference Pilon, Cava, Hoffmann, Abreu, Fidelis and Durigan2021). In this context, fire-related cues – such as heat and smoke – may have a high adaptive value for pyrophytic species. Accordingly, fire-related cues have been reported to stimulate germination and seedling growth traits (Lange and Boucher, Reference Lange and Boucher1990; Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Van Staden, Granger and Brown1994; Clarke and French, Reference Clarke and French2005; Sparg et al., Reference Sparg, Kulkarni, Light and Van Staden2005; Light et al., Reference Light, Daws and Van Staden2009; Moreira et al., Reference Moreira, Tormo, Estrelles and Pausas2010; Ghebrehiwot et al., Reference Ghebrehiwot, Kulkarni, Kirkman and Van Staden2012; Mojzes et al., Reference Mojzes, Csontos and Kalapos2015; Tavşanoğlu et al., Reference Tavşanoğlu, Çatav and Özüdoğru2015; Zirondi et al., Reference Zirondi, Silveira and Fidelis2019), which are both common strategies for population maintenance (Labouriau et al., Reference Labouriau, Valio, Salgado-Labouriau and Handro1963; Salazar et al., Reference Salazar, Goldstein, Franco and Miralles-Wilhelm2011; Andrade and Miranda, Reference Andrade and Miranda2014).

In the Cerrado, grasses correspond to the majority of the biomass in the ground layer (Castro and Kauffman, Reference Castro and Kauffman1998), and most of the species present a perennial life cycle, with seed dispersal through the dry season (Sarmiento, Reference Sarmiento1992; Munhoz and Felfili, Reference Munhoz and Felfili2007), when wildfires are frequent (Pivello, Reference Pivello2011). As in other savannas, Cerrado fires are sustained by the ground layer and have a low residence time of high temperatures (Miranda et al., Reference Miranda, Miranda, Dias and Dias1993). Several studies suggest that germination responses are idiosyncratic among grassland species worldwide and report that grass seeds can tolerate heat shocks up to 100°C without detrimental effects (Clarke and French, Reference Clarke and French2005; Overbeck et al., Reference Overbeck, Müller, Pillar and Pfadenhauer2006; Dayamba et al., Reference Dayamba, Tigabu, Sawadogo and Oden2008; Ramos et al., Reference Ramos, Liaffa, Diniz, Munhoz, Ooi, Borghetti and Valls2016; Paredes et al., Reference Paredes, Cunha, Musso, Aires, Sato and Miranda2018; Ramos et al., Reference Ramos, Valls, Borghetti and Ooi2019; Dairel and Fidelis, Reference Dairel and Fidelis2020a; Gorgone-Barbosa et al., Reference Gorgone-Barbosa, Daibes, Novaes, Pivello and Fidelis2020). Likewise, smoke stimuli on germination do not present a clear pattern for grasses (Dayamba et al., Reference Dayamba, Tigabu, Sawadogo and Oden2008; Fernandes et al., Reference Fernandes, Oki, Fernandes and Moreira2021). On the other hand, the effect of smoke on grass seedling development is still scarce and indicates that measurable parameters might be noticeable only in post-germinative phases (Taylor and van Staden, Reference Taylor and van Staden1996; Blank and Young, Reference Blank and Young1998; Daws et al., Reference Daws, Davies, Pritchard, Brown and Van Staden2007; Ghebrehiwot et al., Reference Ghebrehiwot, Kulkarni, Kirkman and Van Staden2012). In addition, early seedling development is a critical phase in the plant life cycle, and previous studies have shown noticeable effects of smoke during this stage (Sparg et al., Reference Sparg, Kulkarni, Light and Van Staden2005).

Different aspects of smoke may result in a broader ecological significance than heat-shock. First, smoke may influence areas that have not been burned but are adjacent to its occurrence. Curtis (Reference Curtis1998) and Lamont and Downes (Reference Lamont and Downes2011) inferred that an increased blooming in an unburned area resulted from smoke drift from burned adjacent areas (200–1000 m apart). However, few studies address the effects of dry smoke, which surrogates field conditions in the dry season (Sparg et al., Reference Sparg, Kulkarni, Light and Van Staden2005; Dayamba et al., Reference Dayamba, Tigabu, Sawadogo and Oden2008). Second, smoke-stimulated germination is registered in a large number of clades around the world and may be an ancestral feature in plant phylogeny (Keeley and Pausas, Reference Keeley and Pausas2018). Third, the smoke compound credited for triggering the processes (butenolide, karrikinolide-1) acts in small concentrations and can be originated by any cellulose combustion (Flematti et al., Reference Flematti, Ghisalberti, Dixon and Trengove2004; Light et al., Reference Light, Daws and Van Staden2009). Also, the butenolide penetrates the soil, possibly influencing the soil seed bank, which is isolated from high temperatures (Stevens et al., Reference Stevens, Merritt, Flematti, Ghisalberti and Dixon2007; Ghebrehiwot et al., Reference Ghebrehiwot, Kulkarni, Kirkman and Van Staden2012). In this context, the smoke could alter the plant community by affecting native and exotic plants present in the areas.

African grasses represent a threat to Cerrado's biodiversity leading to changes in the local species composition (Pivello et al., Reference Pivello, Carvalho, Lopes, Peccinini and Rosso1999; Zenni and Ziller, Reference Zenni and Ziller2011). For the ground layer vegetation, the threat increases if a positive interaction between smoke and the invasive species is presented. Among the alien grasses, Urochloa decumbens (Stapf) R. D. Webster – a perennial C4 grass – is the most widespread due to pasture formation in the region (Loch, Reference Loch1977; Zenni and Ziller, Reference Zenni and Ziller2011). U. decumbens is a strong competitor in the soil bank by forming a transient soil seed bank larger than native species, also by excluding other invaders (Correia and Martins, Reference Correia and Martins2015; Dairel and Fidelis, Reference Dairel and Fidelis2020b). Although transient, the seed bank is continuously replenished by several flowering episodes throughout the year (Florencio et al., Reference Florencio, Arruda and de Figueiredo2009; Dantas-Junior et al., Reference Dantas-Junior, Musso and Miranda2018; Xavier et al., Reference Xavier, Leite and Matos2019). The U. decumbens invasiveness may also be associated with its high vegetative reproduction rates (Loch, Reference Loch1977). Among the native Cerrado grasses, Echinolaena inflexa (Poir.) Chase – a perennial C3 species – is dominant in the ground layer, with broad distribution through the biome (Klink and Joly, Reference Klink and Joly1989; Pivello et al., Reference Pivello, Carvalho, Lopes, Peccinini and Rosso1999). This species has a set of morphological plasticity traits influenced by environmental conditions, which allow colonization of burned areas through seed dispersal and vegetative resprouts (Miranda and Klink, Reference Miranda, Klink, Miranda, Saito and Dias1996a,Reference Miranda, Klink, Miranda, Saito and Diasb). Also, E. inflexa presents dominance in the soil seed bank in the months after burns (Andrade and Miranda, Reference Andrade and Miranda2014). Both E. inflexa and U. decumbens present a similar seed morphology and seedling emergence, high vegetative reproduction rates, stoloniferous growth habit, and are widely distributed in Brazil. Even though U. decumbens was not able to alter the distribution of E. inflexa in degraded Cerrado areas (Pivello et al., Reference Pivello, Carvalho, Lopes, Peccinini and Rosso1999), due to their similarities, these grasses could compete for similar niches in cases of co-occurrence, therefore comparing both species is a coherent approach for studying their interaction.

Here, we investigate the effects of smoke on germination and early seedling development of E. inflexa and U. decumbens. By evaluating the changes in germinative parameters, seedling mass and seedling length, we aim to provide an overview of responses of these species to different dry smoke exposure periods. Given the evolutionary history of E. inflexa with fire in the Cerrado, we initially hypothesized that exposure to smoke would result in overall beneficial effects for the native grass, whereas the invasive would present negative or no responses. In addition, considering that smoke is known to affect the germination of a large number of plants (Keeley and Pausas, Reference Keeley and Pausas2018) and invasive grasses may alter the ecosystem's plant community, our study can be valuable for management purposes and provide further insights into the response of E. inflexa to smoke and in the invasion success of U. decumbens in the Cerrado.

Materials and methods

Studied species and seed sorting

The species used in this study were E. inflexa and U. decumbens. Seeds of E. inflexa were collected in the Reserva Ecológica of IBGE (35 km South of Brasília, DF, 15°55′S, 47°52′W) at the end of the rainy season in 2017 (March–April). Seeds of U. decumbens were bought for presenting low quality and quantity in field conditions. The diaspores of both species were manually sorted and tested, selecting only those containing a full caryopsis (Brasil, 2009; Aires et al., Reference Aires, Sato and Miranda2014). The seeds were stored in ambient conditions (~25°C, 50% R.U.) inside paper bags in the laboratory cabinets until the experiment.

Fumigation

The fumigation was carried out in January 2018, with dry smoke derived from the burn of leaf litter collected in an open savanna (cerrado sensu stricto) area at the Reserva Ecológica of IBGE. Before burning, the litter was dried in an oven at 60°C for 48 h and homogenized to ensure a similar smoke composition in all replicates (Light et al., Reference Light, Daws and Van Staden2009). The smoke passed through a chimney, ca 2 m distant from the heat source, avoiding any temperature effect on seeds. Smoke and air temperatures (T s and T a) were attested by two thermocouples (type k: chromel/alumel, 30 swg): the first placed over the fine-mesh (1 mm) metallic support where the seeds were positioned during fumigation, and the second 2 m apart from the heat source in the upwind direction (T s = 1011×T a; r 2 = 0.9852; P = 0.0001). The seeds were arranged on the mesh without overlapping, to ensure a homogeneous exposure to the smoke. The seeds were smoked for 5, 10, 15 or 20 min and a control group (without exposure), waiting for complete smoke dissipation between replicates. For each species and treatment, we used five replicates with 70 seeds each, randomly selected from the previously sorted seeds. To avoid pseudoreplication, each replicate was fumigated separately (Morrison and Morris, Reference Morrison and Morris2000).

The number of seeds per replicate (70) was established by a 48-h viability test under dark conditions, applying a 1% solution of 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (Lakon, Reference Lakon1949), carried out 5 months before the fumigation. The tetrazolium solution was applied to seeds of each species, with no optimization for either. The viability was assessed by cutting all seeds under a dissecting microscope to determine the presence of a coloured embryo.

Germination

After the smoke exposure, the seeds were sown in Petri dishes with filter paper and moistened with distilled water. No chemical or physical treatment was applied to the seeds to prevent contamination by pathogens or fungi (Paredes et al., Reference Paredes, Cunha, Musso, Aires, Sato and Miranda2018). The dishes were placed in a greenhouse under white light (12 h/12 h), ambient temperature and humidity (~27°C; 54%) and kept continually moistened by distilled water. The number of germinated seeds was counted daily for 30 d. The seeds were considered germinated when presenting aerial parts and the geotropic curvature of the radicle (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Verma, Ram and Singh2012). We also registered the initial time of germination (T0) and calculated the mean germination time (MGT). The formula used for the MGT was (Σ(n × d)/N), where n is the number of germinated seeds per day, d is days passed since the beginning of the experiment and N is the total number of germinated seeds (Kochankov et al., Reference Kochankov, Grzesik, Chojnowski and Nowak1998). After the experiment period, the non-germinated seeds were tested for viability as described previously.

Seedling parameters and Root:Shoot ratio

Concurrent with germination, we evaluated changes in the mass and length of seedlings after cultivation for 3, 7 or 15 d. All seedlings were cultivated under the same light, temperature and humidity conditions as previously described. For each smoke treatment, the germinated seeds were transferred from the Petri dishes to trays with moistened filter paper. The seedlings were identified by replicate and germination date. After 3 and 7 d of cultivation, five seedlings of each replicate were harvested for mass and length measurements. Also, five seedlings of each replicate were transferred to pots (5 cm diameter × 9 cm depth) in which they were cultivated for 15 d. The pots contained a commercial substrate made with Sphagnum peat moss, coconut fibre, rice husk, Pinus bark, vermiculite, NPK and micronutrients, and pH 6.0–6.5 (Pires et al., Reference Pires, Franco, Piedade, Scudeller, Kruijt and Ferreira2018). To avoid damage to the root system and biomass loss, the seedlings cultivated for 3 and 7 d were carefully removed with tweezers from the filter paper. Seedlings grown for 15 d were carefully rinsed under running water to remove the substrate. The seedlings were cut directly below the cotyledon, at the beginning of the root system, and the aerial and root parts were measured in length, dried for 48 h in an oven (60°C), and then weighted for attaining the dry mass (0.00001 g precision). For the control group, the data collection followed the same procedures described above. With the length and dry mass data, we conducted the Root:Shoot (R:S) analysis to assess the investment in root development.

Data analysis

We applied a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with a binomial error distribution and Logit link function to analyse the differences in the percentages of germination and viability of non-germinated seeds between species for each treatment. In the GLMM analysis, we used the replicates as random effects. For the T0 analysis, we used a generalized linear model (GLM) with a Quasi-Poisson error distribution and Log link function, since it consisted of underdispersed count data. The effects of the treatments on the MGT were evaluated using a GLM with a Gamma error structure and an Identity link function, with species and smoke treatment as predictor variables and the MGT as response variable. To analyse the effects of smoke in the development of seedlings for each cultivation period (3, 7 or 15 d), we used the same method of MGT. After adjustments all models were attained, we tested the interaction between our predictors (species and treatment). Whenever significant, the interactions were compared pairwise utilizing Tukey (P < 0.05), otherwise the effects of treatments were considered similar for both species.

In the analysis of seedling development, we used the average of the parameters (length and mass of the root and shoot systems) of five cultivated seedlings as input for the models, to overcome the lack of independence between seedlings pooled in the same Petri dishes. Whenever necessary, we removed outliers from the models based on Cook's distance method. In order to assure all models’ adjustments, the distribution and variance of residuals was visually assessed and analysed by the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests. All GLM and GLMM analyses were tested for over- and under-dispersion of residuals using a goodness-of-fit ratio (residual deviance/degrees of freedom; Dunn and Smyth, Reference Dunn, Smyth, Dunn and Smyth2018) and the testDispersion() function from the DHARMa package (Hartig, Reference Hartig2022; see also Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Kristensen, Darrigo, Rubim, Uriarte, Bruna and Bolker2019). The analyses were carried out using the R software (version 4.0.0, R Core Team, 2021), the models were constructed with the stats (R Core Team, 2021) and lme4 (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015) packages, and the graphics were built using the ggplot2 package (Wickham, Reference Wickham2016). Our model analyses were overall based on Zuur et al. (Reference Zuur, Ieno, Walker, Saveliev and Smith2009).

Results

Germination

The germination of U. decumbens was greater than the germination of E. inflexa (P < 0.0001), and we did not find any effect of smoke on the germination of either species. On average, the germination of the exotic grass was 65 ± 14%, and for E. inflexa was 32 ± 10% (Fig. 1A). From the initial tetrazolium solution tests, the seeds of U. decumbens displayed 78 ± 8% viability, 5.2-fold greater than that of E. inflexa (15 ± 10%; t = −11.172; P < 0.0001). On the other hand, the percentage of non-germinated viable seeds was 3.3-fold greater in E. inflexa (P < 0.0001). After 20 min of smoke exposure, E. inflexa presented a significantly greater percentage of fertile non-germinated seeds (22 ± 5%), whereas in U. decumbens it was reduced to 4 ± 2% (P < 0.05; Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Germinative parameters measured for a native (Echinolaena inflexa) and an invasive (Urochloa decumbens) grass species common in the Cerrado, after different periods of smoke exposure. (A) Germination; (B) percentage of viable non-germinated seed remaining after the experiment; (C) mean germination time; and (D) time necessary to the first germination. Asterisks denote statistical significance between treatments within species. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Compared to the control, there was a reduction in MGT of both species after 5 min of fumigation (P < 0.05; Fig. 1C). However, E. inflexa generally presented a higher MGT (P < 0.0001). Except for 10 min, there was a reduction in T0 for fumigated E. inflexa seeds compared to the control group, reaching 4 ± 0 d after the 5 or 20 min of smoke exposure (P < 0.05; Fig. 1D). On the other hand, T0 of U. decumbens was synchronic, just 1 d after the fumigation of seeds.

Seedling parameters and R:S ratio

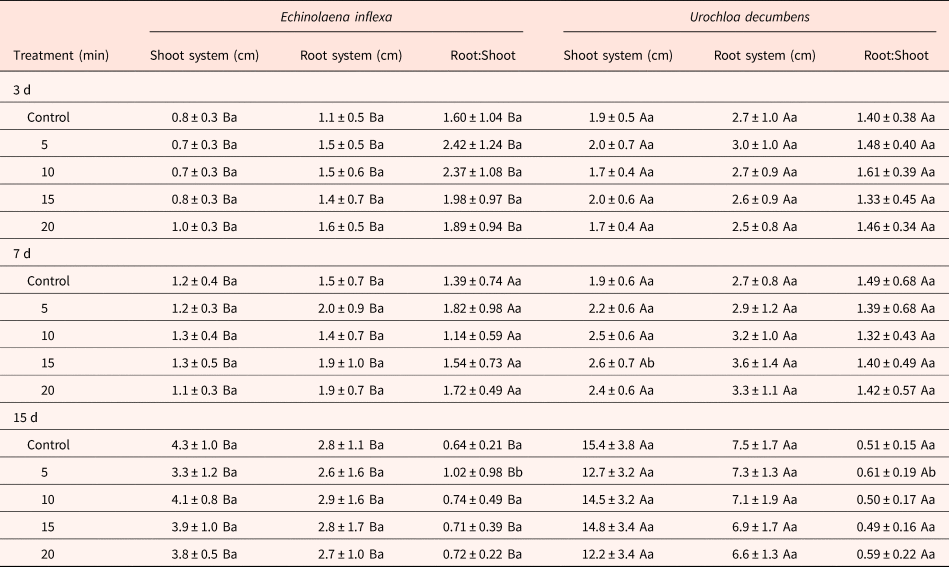

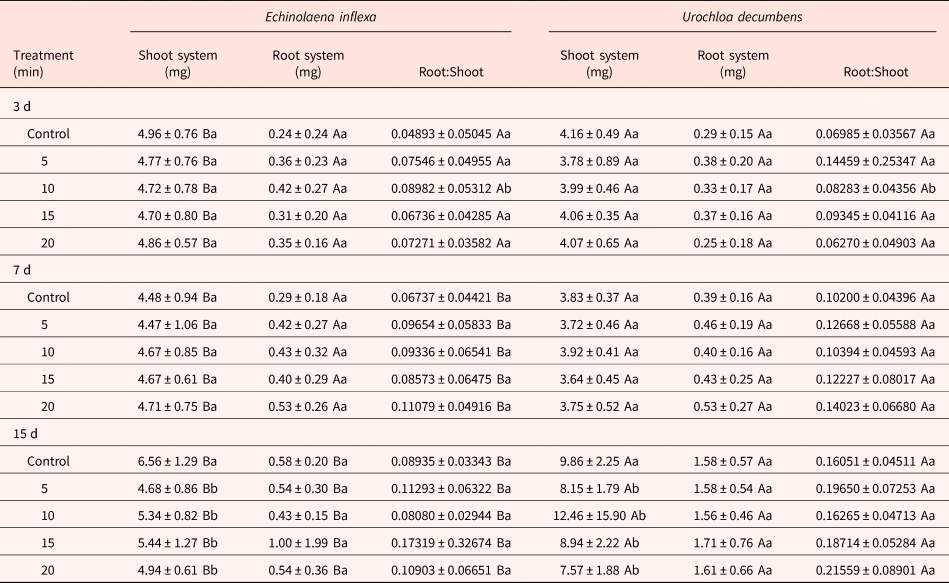

After 3 d of development, the length of the shoot and root systems of seedlings of U. decumbens were 2.3-fold and 1.9-fold greater than seedlings of E. inflexa. However, E. inflexa's seedlings presented greater aboveground mass (1.2-fold; P < 0.0001) than U. decumbens’, with no difference in the root system mass. The smoke treatment did not affect any of these parameters (Table 1). After 7 d, the same pattern was maintained when comparing the species (P < 0.0001). However, seeds of U. decumbens fumigated for 15 min increased the aboveground length from 1.9 ± 0.6 cm in the control to 2.6 ± 0.7 cm (P < 0.01; Table 1). After 15 d, U. decumbens had higher mass and length values than E. inflexa for both shoot and root systems (P < 0.0001; Tables 1 and 2). Also, smoke treatment affected the shoot system in both species, reducing the mass in all treatments, reaching a maximum reduction (1.3-fold) after 20 min of treatment (P < 0.0001; Table 2). The fumigation altered the aboveground length as well, resulting in a reduction after 5 min in both species (P < 0.001; Table 1). There was no significant alteration in the root system of the species.

Table 1. Effects of different smoke exposure periods on the length of shoot and root systems, and the Root:Shoot ratio of Echinolaena inflexa and Urochloa decumbens

Upper case letters represent statistical differences between species when analysing the same treatment, whereas lower case letters represent statistical differences between treatments within the same species.

Table 2. Effects of different smoke exposure periods on mass of aerial and root systems, and the Root:Shoot ratio of Echinolaena inflexa and Urochloa decumbens

Upper case letters represent statistical differences between species when analysing the same treatment, whereas lower case letters represent statistical differences between treatments within the same species.

When the R:S ratio was calculated with length values (length-R:S), after 3 d of development, the length-R:S of E. inflexa was 1.4-fold greater than U. decumbens (P < 0.001), with no significant differences between treatments. After 7 d, the length-R:S did not present significant differences comparing species or treatments. For 15 d of development, the E. inflexa's length-R:S (0.76 ± 0.54) remained higher than that of U. decumbens (0.54 ± 0.18; P < 0.0001), and was increased in both species after 5 min of exposure to smoke (P < 0.05; Table 1). When calculated with the mass data (mass-R:S), the R:S after 3 d increased after 10 min of exposure to smoke in both species (U. decumbens: 1.2-fold; E. inflexa: 1.8-fold; P < 0.05), but there was no significant difference between species. After 7 d, the mass-R:S of U. decumbens was 1.3-fold higher (P < 0.01), with no significant differences between treatments (Table 2). For 15 d of development, the mass-R:S of U. decumbens remained higher than E. inflexa (P < 0.0001), however none showed treatment effects (Table 2).

Discussion

In summary, U. decumbens showed higher values for all studied germinative parameters than E. inflexa. The invasive species showed higher and faster germination rates, a smaller number of dormant seeds, and did not show smoke effects in the germination percentages. Accordingly, the low occurrence of such responses in grasses has been previously shown (Pérez-Fernández and Rodríguez-Echeverría, Reference Pérez-Fernández and Rodríguez-Echeverría2003; Clarke and French, Reference Clarke and French2005; Daws et al., Reference Daws, Davies, Pritchard, Brown and Van Staden2007; Dayamba et al., Reference Dayamba, Tigabu, Sawadogo and Oden2008) including for both species addressed here (Le Stradic et al., Reference Le Stradic, Silveira, Buisson, Cazelles, Carvalho and Fernandes2015; Gorgone-Barbosa et al., Reference Gorgone-Barbosa, Daibes, Novaes, Pivello and Fidelis2020; Fernandes et al., Reference Fernandes, Oki, Fernandes and Moreira2021). For the Cerrado, smoke-enhanced germination is only reported for Aristida spp. (Le Stradic et al., Reference Le Stradic, Silveira, Buisson, Cazelles, Carvalho and Fernandes2015; Ramos et al., Reference Ramos, Valls, Borghetti and Ooi2019). In addition, Andropogon gayanus, another African invasive species in Cerrado, showed slower germination rates after being treated with aerosol smoke (Dayamba et al., Reference Dayamba, Tigabu, Sawadogo and Oden2008). In contrast, the MGT of U. decumbens was not affected by smoke in our experiment. Such an outcome may be a consequence of the capacity of species for overcoming environmental stresses (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Martins, Souza and Martins2012; Dantas-Junior et al., Reference Dantas-Junior, Musso and Miranda2018; Xavier et al., Reference Xavier, Leite and Matos2019). Despite not presenting tangible responses to smoke, the germination rate of U. decumbens seeds also depicted the invasive potential of the species, as all replicates germinated 3 d earlier than the first E. inflexa seed.

Albeit lower than U. decumbens’ germination, E. inflexa's germination was more responsive to smoke, as the fumigation anticipated the onset of germination of the native species. Although higher than some values reported for the species in previous studies (e.g. Le Stradic et al., Reference Le Stradic, Silveira, Buisson, Cazelles, Carvalho and Fernandes2015; Musso et al., Reference Musso, Miranda, Aires, Bastos, Soares and Loureiro2015), the germination values of E. inflexa showed no difference after fumigation. Such behaviour may be due to dormancy of E. inflexa's seeds (Aires et al., Reference Aires, Sato and Miranda2014; Le Stradic et al., Reference Le Stradic, Silveira, Buisson, Cazelles, Carvalho and Fernandes2015; Ramos et al., Reference Ramos, Liaffa, Diniz, Munhoz, Ooi, Borghetti and Valls2016) and an inability of the smoke to alleviate it. Nevertheless, the anticipation in T0 may represent an opportunity for earlier establishment and competitive advantage. It is also noteworthy that the MGT of E. inflexa corresponds to the lowest values measured among other native grasses (Aires et al., Reference Aires, Sato and Miranda2014). Therefore, E. inflexa should have an advantage in colonizing recently burned areas in the Cerrado or competing with other native species for establishment opportunities. However, all U. decumbens replicates presented faster initial germination and overall lower MGT, which suggests it would be a better competitor than E. inflexa.

Seed viability of U. decumbens was also significantly higher (5.2-fold) than that of E. inflexa, determined by the initial tetrazolium solution test. Nevertheless, the germination percentage of the invasive species was only twice the value of the native. Also, the number of non-germinated viable seeds, assessed by viability tests after the experiment period, was 3.3-fold larger for E. inflexa. These results suggest that the viability of the fumigated E. inflexa seeds was higher than previously calculated by the initial tetrazolium solution test, 5 months prior. It is worth mentioning that Aires et al. (Reference Aires, Sato and Miranda2014) also reported an increase in the viability of E. inflexa seeds after 1-year of storage, which supports this inference. In addition, despite the low initial viability, the germination results were consistent with the varied values reported by previous studies on E. inflexa (Musso et al., Reference Musso, Miranda, Aires, Bastos, Soares and Loureiro2015 (8–19%); Paredes et al., Reference Paredes, Cunha, Musso, Aires, Sato and Miranda2018 (52%); Fontenele et al., Reference Fontenele, Figueirôa, Pereira, Nascimento, Musso and Miranda2020 (20%)). We did not reassess seed viability closer to the fumigation, leading to germination values larger than predicted by the tetrazolium results for the native species. Nevertheless, the gemination results show that the comparison between the species was fairer than the initial viability suggested.

Although U. decumbens showed higher length values of root and shoot systems in all periods of cultivation, the mass values only surpassed E. inflexa's after 15 d. A possible explanation is cellular elongation in the early days of U. decumbens’ seedlings development (Kutschera, Reference Kutschera2000). Meanwhile, considering length-R:S, E. inflexa presented a higher root investment, whereas U. decumbens had a longer aerial part. Moreover, smoke effects were recorded in the endmost periods of cultivation, with 5 min of exposure increasing the root investment. Furthermore, analysing the root and shoot system length could indicate eventual detrimental effects of smoke, since these post-germinative parameters have shown sensitivity in response to stressors, such as herbicides and allelopathic substances (Sparg et al., Reference Sparg, Kulkarni, Light and Van Staden2005; Navas and Pereira, Reference Navas and Pereira2016; Muniz et al., Reference Muniz, Garcia, Braga, Fátima and Modolo2019). Nonetheless, when calculated with mass, U. decumbens presented a higher root investment than E. inflexa. Also, 10 min of smoke exposure led to higher values in the early stages of development in both species.

In addition, both length-R:S and mass-R:S results indicate cellular elongation in seedlings of U. decumbens, as an effort to develop the aerial part and photosynthetic surface and later allocating the resources to the root system. The development of the root system in the seedlings is essential for the recruitment, since it increases seedling fixation to the soil and favours water and nutrient accessibility (Ries and Svejcar, Reference Ries and Svejcar1991; Leskovar and Stoffella, Reference Leskovar and Stoffella1995; Lynch, Reference Lynch1995). Also, investment in the root system enables the storage of soluble carbohydrates, which are important for protection of tissues to stresses, sustenance during periods of photosynthesis limitation (e.g. drought, post-fire), and play a role in the osmotic adjustment (Souza et al., Reference Souza, Sandrin, Calió, Meirelles, Pivello and Figueiredo-Ribeiro2010; Moraes et al., Reference Moraes, Carvalho, Franco, Pollock and Figueiredo-Ribeiro2016). Therefore, well-developed underground organs are essential for Cerrado grasses survival and resprout (Pilon et al., Reference Pilon, Cava, Hoffmann, Abreu, Fidelis and Durigan2021). A heavier root system, thus denser, suggests a larger carbon allocation and cellular development by the native species in the early days. On the other hand, photosynthetic areas represent independence of the seed's reserves and carbon fixation by the seedling (Wright and Westoby, Reference Wright and Westoby2000), which would later provide more resources for the root system development. In this context, the reduction in aboveground mass of 15-d seedlings of both species in all fumigation periods suggests detrimental effects of smoke on the early development of these grasses.

As shown by a lower T0 and MGT, dry smoke exposure hastens the germination process of E. inflexa, a native grass of Cerrado. On the one hand, this result is not enough to overcome the invasive U. decumbens, which shares several functional traits. On the other hand, when considering post-germinative parameters, E. inflexa presents a greater seedling development in its early days, contributing to the native's success in an eventual competition. Since Keeley and Pausas (Reference Keeley and Pausas2018) argued that responses to smoke might be an exaptation present in several groups of plants, such effects could likely comprise different life stages and appear erratically in related species, as evidenced here. Therefore, analysing post-germinative parameters and seedling development may bring elucidating answers on the smoke effects.

Due to the expansion of U. decumbens’ invasion in the Cerrado (Macedo, Reference Macedo2005), the interaction between the studied species has become more frequent, leading to a possible scenario of competitive exclusion. In this context, the invasion success should be lower due to the shared functional traits of exotic species with natives (MacArthur and Levins, Reference MacArthur and Levins1967; Symstad, Reference Symstad2000; Diez et al., Reference Diez, Sullivan, Hulme, Edwards and Duncan2008). Nevertheless, the values of T0, MGT and R:S suggest that the niche similarity between native and invasive grasses may not ensure resistance to the U. decumbens invasion in the Cerrado (see also Damasceno et al., Reference Damasceno, Souza, Pivello, Gorgone-Barbosa, Giroldo and Fidelis2018). However, Klink (Reference Klink1996) reports that seedlings of E. inflexa showed a continual survival rate in the field, while the seedlings of the invasive A. gayanus were largely threatened by predation. In this context, high seedbank occupancy (Dairel and Fidelis, Reference Dairel and Fidelis2020b), greater and faster germination rates, and enhanced root investment of U. decumbens may not be fully reflected in the seedling recruitment. Such considerations reinforce that different traits should also be taken in consideration for management purposes (Assis et al., Reference Assis, Pilon, Siqueira and Durigan2021) and for assessing the competition between native and alien grasses.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the staff of the Reserva Ecológica of IBGE for authorizing seed and litter collection; the Department of Ecology and the Department of Cellular Biology of the Universidade de Brasília for providing technical support and infrastructure; and ProiC/UnB/CNPq for the scholarships granted to A.B.D.-J. We also thank Murilo S. Dias and Micael F.R. Lima for their valuable assistance with data analysis.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.