Introduction

Background

Burnout is a maladaptive response to chronic emotional distress due to a highly interpersonally-oriented work environment Reference Maslach1 that the World Health Organization (WHO; Geneva, Switzerland) recently recognized as a work-related syndrome and described it as a form of emotional exhaustion, detachment with patients and professional role, and loss of professional satisfaction. 2 Leiter and Maslach Reference Leiter and Maslach3 have recently presented five latent burnout profiles, based on a person-centered analysis, which enriched the traditional dual definition by adding three intermediate steps between burnout and engagement. The authors proposed that having one of the three-factor scores out of the cut-off describes a state of disengagement (high in Depersonalization [DP]), over-extension (high in Emotional Exhaustion [EE]), and ineffectiveness (low in Personal Accomplishment [PA]). This approach could provide a more tailored measurement of the burnout phenomenon in different groups of people, particularly if their professional role has not been studied before.

The available reviewed literature on burnout in emergency medicine detects burnout levels of more than 60% in emergency physicians. Reference Arora, Asha and Chinnappa4 A recent meta-analysis confirmed that approximately 30% of emergency nurses are affected with at least high EE or DP, or low PA. Reference Gómez-Urquiza, la Fuente-Solana and Albendín-García5 Unpredictability, over-crowding, and continuous confrontation with traumatic events in the emergency field could be specific risk factors for burnout in this population. Reference Adriaenssens, Gucht and Maes6

However, emergency staffs also include other technicians that are involved in the rescue operation, sometimes as the first-line or only team. In 1992, the 118-service was instituted in Italy, a cross-national institute of emergency, working on the public health ambulances and in an operating center. The 118-service ambulance driver-rescuers drive the ambulance and furnish first aid to the victims, and they are frequently responsible for quick and crucial decisions; in some pre-selected occasions, a nurse or an emergency physician intervene in a medical ambulance. These driver-rescuers are the non-medical part of the multidisciplinary team, present with different names and training characteristics all around the world (for example, drivers and attendants, or Except Emergency Medical Technicians [EMTs] or EMT-Basic in the United States). In Italy, ambulance driver-rescuers attend a regional course to obtain the license to be a driver and a rescuer of the ambulance. However, they do not constitute a professional category, codified into a professional order, and patients and other emergency operators working with them often misinterpret their role. These characteristics could represent an additional risk factor for unacknowledged and untreated burnout in this group of operators, Reference O’Connor, Muller Neff and Pitman7 which may present specific features.

Even if they are likely to be exposed to witnessing distress and to experiencing higher levels of physical and psychological symptoms, as well as job dissatisfaction, as compared to other professions, Reference Johnson, Cooper and Cartwright8 they have received less attention in research. To date, only two studies examined burnout in driver-rescuer operators in Italy. Argentero and Setti Reference Argentero and Setti9 found higher levels of burnout in 42 operators of the 118-service compared to police operators. Angius and colleagues Reference Angius, Campana and Cattari10 examined 176 health professionals by comparing them with 79 emergency operators (42 of them were the same group of operators of 118-service already tested in the previous study), and this last group showed a lower burnout risk and a condition of well-being as compared to the other.

The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Service Survey (MBI-HSS) Reference Maslach, Jackson and Leiter11 has been widely used to assess burnout. The questionnaire includes three dimensions: EE, DP, and PA. Despite general reliability of the three-factorial structure, this has not been fully replicated in the Italian version of the MBI Reference Sirigatti, Stefanile, Maslach and Jackson12–Reference Pisanti, Lombardo and Lucidi15 as it was in other versions. Reference Loera, Converso and Viotti16 Authors attributed this inconsistency to item redundancy, misplacement in factors, or “lost in translation” phenomena and loss of cross-cultural adaptation. Reference Loera, Converso and Viotti16,Reference Squires, Finlayson and Gerchow17 Not surprisingly, the specific profession of survey responders at MBI accounts for high variance in factorial loading replication; differences in the interpretation of the meaning of the item could be sample-specific and linked to professional history, current context, and goals of the subjects. Reference Vanheule, Rosseel and Vlerick18,Reference Wheeler, Vassar and Worley19

Importance

The lack of research in this context makes it challenging to picture the on-the-job training and psychological surveillance required for these semi-professional figures. Moreover, these operators are the first-line interface with patients, and their well-being and professional satisfaction is an essential factor of success in the multidisciplinary work team and the rescue operations.

Goals of this Investigation

This survey investigated for the first time the prevalence of and the exact profile for burnout in the Sicilian population of ambulance drivers-rescuers. Firstly, the study aimed to classify subjects according to different burnout profiles. Reference Leiter and Maslach3 As a secondary aim, it wanted to describe how the 22 items of the Italian version of the MBI-HSS cluster in components in this category of workers.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

The study was a descriptive cross-sectional survey, with a census sampling strategy, which included the entire population of ambulance driver-rescuers of 118-service operating in Sicily in the study period (from June 2015 through May 2016). The subjects surveyed were attending an on-the-job training that involved all the Sicilian 118-service operators, aimed to improve emergency management through psychological, legal, and technical training. Each tutor, who followed-up the class along with all the courses, informed participants before the survey distribution, together with the psychologist who was responsible for the general training and supervising inter-reliability of administration mode, in the group setting during the first meeting. They instructed responders to work individually. Those fulfilling the questionnaires were consenting anonymous responders. All data were anonymous and voluntarily furnished; empty questionnaires were accounted as refusers. The tutor-in-chief for each district received the questionnaires that were then recollected in Palermo. Researchers from the Institute of Psychiatry at Department of Biomedicine, Neuroscience, and Advanced Diagnostic (BiND), University of Palermo (Palermo, Sicilia, Italy) checked data for accuracy and internal consistency and performed statistical analyses.

Sicily is the largest region of Italy (25,832.39 km2) and fourth in terms of population (5,026,989 resident people in 2018), with 350,538 annual 118-emergency interventions (2015; on a national mean of 170,594). 20 Thus, these results have a potential external validity for the entire country and can generate hypotheses to test in other geographical areas.

Measurement

It was administered the MBI-HSS because the survey had descriptive aims on the individual well-being (versus burnout), while the Organizational Checkup System (OCS) Reference Borgogni, Galati and Petitta21 had a substantial organizational watch (with a higher number of items dedicated to this part), and it best fits in studies which include hypothesized risk factors.

The Italian Maslach’s version of the MBI-HSS is a self-reported scale constituted by 22 items describing feelings about work and the contact with patients, scored on a seven-point Likert frequency scale from zero (never) to six (every day). The test was validated on an Italian sample of 1,779 subjects. Reference Sirigatti, Stefanile, Maslach and Jackson12 It consisted of three factors: EE – nine items (Cronbach’s Alpha [α] = 0.87) that measure feelings of being emotionally over-extended and exhausted by one’s work; DP – five items (α = 0.68) measuring an unfeeling and impersonal response toward patients; and PA – eight items (α = 0.76) that measure feelings of competence and achievement in the individual’s work. The socio-demographic sheet included age, gender, and years of career in the ambulance service.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of the study were the scores obtained at MBI-HSS, differentiated into the three factors. It was used a cut-off for each summed-scale score to explore the exact profile of burnout Reference Leiter and Maslach3 (S-Table 1; available online only) and to classify subjects according to their level of burnout initially. Burnout syndrome would be classically present when scores at EE and DP are high, and scores at PA are low. High PA and low EE and DP describe a strict definition of “engagement.” Reference Sirigatti, Stefanile, Maslach and Jackson12 Other burnout profiles were “disengagement,” with high scores in DP only; “over-extension,” high in EE; and “inefficacy,” low in PA. Subjects’ characteristics not fulfilling these categories were considered as moderate burnout (broader definition) if two sub-scales at least presented medium or high scores (medium or low for PA). People presenting only one scale with average scores were also included in the “engagement” category. The only exposure variable considered was to be enrolled as a worker in the 118-service. Potential effect modifiers were age, gender, and years of career.

Work overload is related to burnout, Reference Nirel, Goldwag and Feigenberg22 and EE in particular, Reference Consiglio, Borgnoni and Vecchione23,Reference Maslach, Schaufeli and Leiter24 and estimated mean sickness absence was indicated as a frequent consequence of burnout. Reference Duijts, Kant and Swaen25 Thus, it was also estimated the mean workload per operator for each district, in 2015, by dividing the number of emergency interventions completed in that district in this year by the number of operators working there in the same year. Similarly, it was possible to obtain a mean sickness absence rate for each district, in 2015, by dividing the number of the days of sickness-absence by the number of operators working in each district in the same year. Both mean workload and mean sickness absence were then classified in quantiles (S-Table 2 and S-Table 3; available online only).

Statistics

Mean and standard deviation of each sub-scale were examined by three summary independent sample t-tests to compare them with the Italian normative data mean and standard deviation from the MBI-HSS (S-Table 1; available online only). Reference Sirigatti, Stefanile, Maslach and Jackson12 Chi-square test from ordinal regression analysis was used to compare the proportion of responders to refusers among different districts to address any sampling bias. ANOVAs, for continuous variables, and Chi-square tests, for categorical variables from ordinal regression, were used to assess effect modifiers by comparing responders classified in each specific burnout profile in terms of age, gender, years of career, workload, and sickness absence. Bootstrap confidence intervals were bias-corrected and accelerated. To understand and describe the structure of the answers to the items in this specific population, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted on the 22 items with orthogonal rotation (Varimax) to obtain eigenvalues for each component in the data and to explore the existence of independent factors (extraction criteria = eigenvalues > one). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure verified the sampling adequacy for the analysis. Bartlett test of sphericity tested if correlations between items were sufficiently large for PCA. The reliability of the test, both in this original structure and in the new five-components solution, was controlled. Alpha coefficient could be affected under variations of the number of items in a measurement, Reference Cortina26 resulting in more significant values for clusters, including a bigger number of items Reference Streiner27 and vice-versa. Thus, to check the reliability and internal consistency of the components, it was used Cronbach’s Alpha (α acceptable if ≥ 0.65) and average inter-item correlations (r acceptable if ranging between 0.15 and 0.50) to overcome the problem of few items included in some components. Reference Cortina26,Reference Streiner27 As an exploratory analysis, there were calculated percentages of responders who had an average Likert score ≥four (at least once a week) at the items clustering in each sub-factor, to see which of those factors accounted for the highest median response to the original component. Missing data were addressed with the listwise method in all the analyses, apart from PCA, which included a pairwise exclusion method. Statistics were performed by using SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp.; Armonk, New York USA) for Mac. 28

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted following the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and received ethical approval from the Sicilian Emergency and Urgency Society (SEUS; Palermo, Sicilia, Italy) 118-service at the time of administration. Further ethical approval was obtained from the Palermo 1 Ethical Committee (verb. 2/2019 – 18.02.2019) before the data acquisition and analysis.

Results

Characteristics of Study Subjects

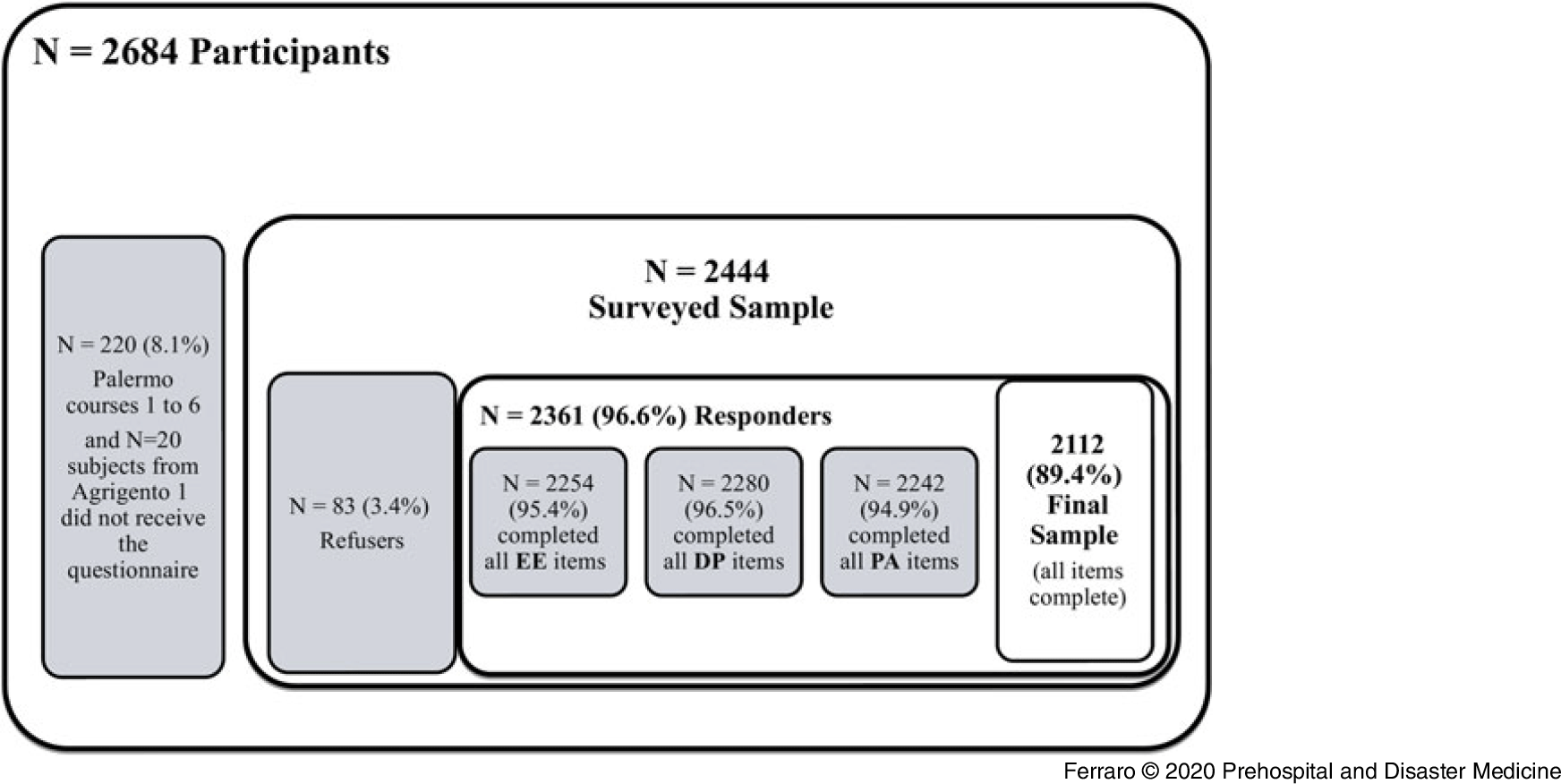

The SEUS 118-service organized 73 courses for a total of 2,684 participants (approximately 36 participants per class) coming from the nine Sicilian districts as part of the National Health Plan (PSN) Action 1.4 Training Projects. The MBI-HSS was proposed to all classes, except Palermo 1 to Palermo 6 (N = 216 subjects) and Agrigento 1 (N = 20 subjects) because they started earlier as the pilot-in-training groups. Thus, a final sample of 2,444 subjects approached the survey (91.0% of the participants). The final sample comprised 2,361 responders, which constituted the 96.6% of the surveyed population, while 83 subjects (3.4%) refused to participate in the survey (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow-Chart of Subjects Included in the Analysis.

Responders were mostly males (77.9%), with a mean age of 44 years (SD = 7.1); they had a mean of 12.2 years of a career (SD = 4.4) in the 118-service. There were no differences in terms of the distribution of responders and refusers’ proportion across the nine Sicilian districts (χ2[2] = 12.3; P = .091; S-Table 4 [available online only]).

Comparison of the Sub-Scales Scores with the Normative Sample and Cut-Off

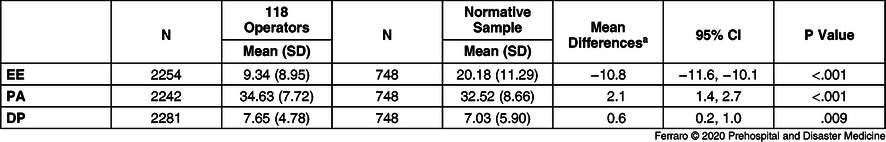

None of the MBI-HSS items and the three sub-scales had missing values >five percent. As compared with the normative sample, mean scores for the EE scale resulted significantly lower than those expected (mean difference [Mdiff] = −10.8; 95% CI, −11.6 to −10.1); the opposite was true for DP (Mdiff = 2.1; 95% CI, 1.4 to 2.7) and PA (Mdiff = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.2 to 1.0), which resulted slightly higher in 118-service operators than in the normative sample (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparisons between the Responders 118-Service Operators and the Italian Normative Sample in Maslach Burnout Inventory Factor Scores

Note: Normative sample from Sirigatti and Stefanile (1993).

Abbreviations: DP, Depersonalization; EE, Emotional Exhaustion; PA, Personal Accomplishment.

a Hartley-Test for equal variance <.001.

Based on factor cut-off, 7.8% (95% CI, 6.8% to 9.0%) presented high levels of EE, 36.0% (95% CI, 34.9% to 39.1%) presented high levels of DP, and 41.3% (95% CI, 41.8% to 45.8%) had low PA scores (Table 2).

Table 2. Medium Scores at EE, DP, PA Factors from MBI

Note: Normative sample from Sirigatti and Stefanile (1993).

Abbreviations: DP, Depersonalization; EE, Emotional Exhaustion; PA, Personal Accomplishment.

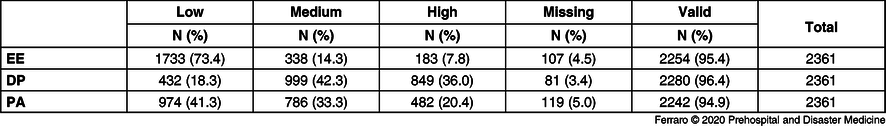

Burnout Prevalence and Profile

Looking at latent burnout profiles, Reference Leiter and Maslach3 1.7% of responders (N = 36; 95% CI, 1.1% to 2.3%) presented severe burnout, based on scale cut-off, while 29.8% (N = 629; 95% CI, 27.8% to 31.8%) were in some intermediate form of burnout. As much as 30.0% (N = 483; 95% CI, 21.0% to 34.8%) were engaged in their work, according to a broader definition, while the strict definition of engagement embraced 7.1% of subjects only (N = 151; 95% CI, 6.1% to 8.3%). The profile of disengagement was present in 24.7% of responders (N = 521; 95% CI, 22.9% to 26.5%), the dimension over-extension enclosed the tiny percentage of 1.2% people (N = 25; 95% CI, 0.8% to 1.7%), and 12.6% felt inefficacy in their work experience (N = 267; 95% CI, 11.3% to 14.1%; Figure 2). Responders with distinctive burnout profiles did not differ regarding gender (χ2[1] = 0.03; P = .845) and years of career (F[6; 2,005] = 0.304; P = .935). A difference among subjects emerged in terms of age (F[6; 2,092] = 2.7; P = .011); responders with good engagement were slightly younger than disengaged (Mdiff = −1.9; 95% CI, −3.9 to −0.008; P = .048). There were no differences in the relationship between sickness absence mean (χ2[2] = 0.26; P = .878) and workload (χ2[2] = 0.61; P = .973] among districts and burnout profiles.

Figure 2. Subjects’ Classification According to their Burnout Profiles.

Reliability of the Original Test

The reliability of the test resulted acceptable (α = 0.689; α Based on Standardized Items = 0.701). The EE sub-scale was the most reliable (α = 0.825; α Based on Standardized Items = 0.827; r = 0.34). The PA sub-scale was reliable, but less than that expected from Maslach Reference Maslach, Jackson and Leiter11 (α = 0.612; α Based on Standardized Items = 0.639; r = 0.18). The DP sub-scale did not present acceptable levels of reliability (α = 0.354; if item 22 is deleted α = 0.384; α Based on Standardized Items = 0.388; r = 0.11).

PCA on MBI-HSS Items

The sample was adequate for the analysis (KMO = 0.874), and all KMO values for individual items were >.5. The correlations between items were sufficiently large for PCA (X2 [231] = 9223.212; P < .001).

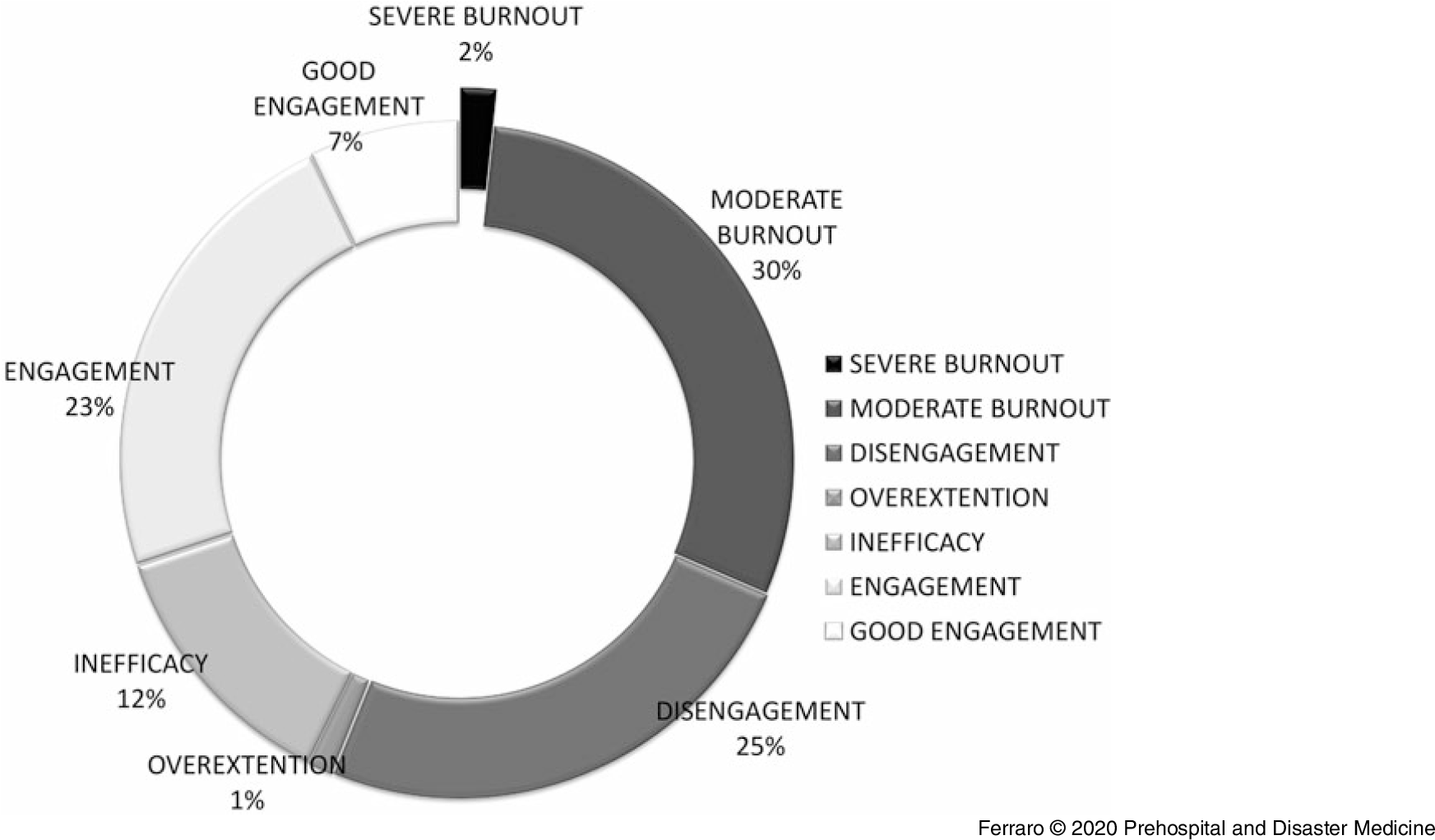

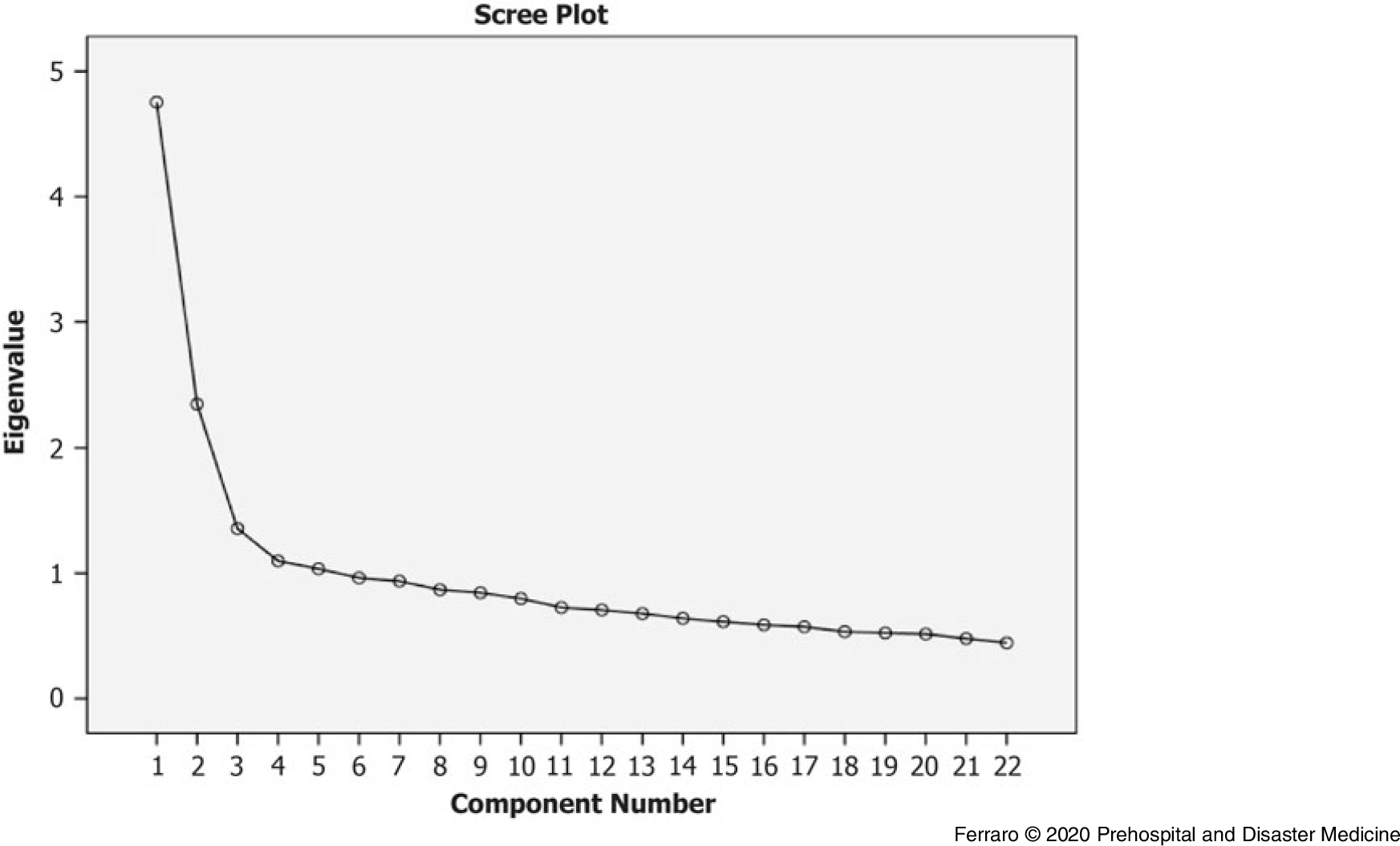

Five components had eigenvalues over one and, in combination, explained 48.1% of the variance. The scree plot was slightly ambiguous and showed inflexions that would justify retaining both Component 3 and Component 5 (Figure 3). Given the large sample size and the convergence of the scree plot and the Kaiser’s criterion on five components, this is the number of components that were retained in the final analysis.

Figure 3. Scree Plot of the Eigenvalues for Components’ Retention in PCA.

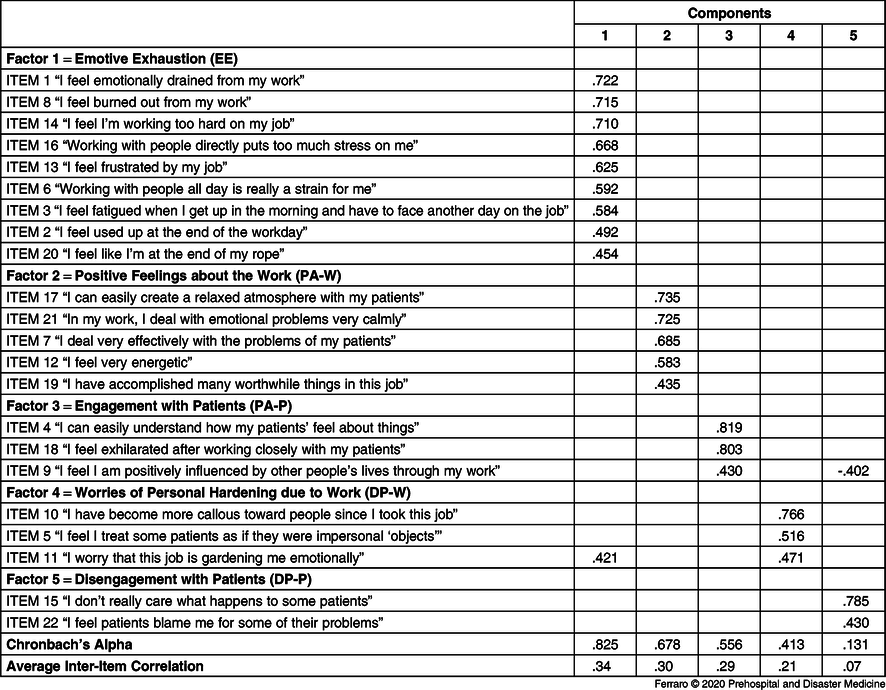

Table 3 shows the factor loadings after rotation. The items that cluster on the same components suggest that Component 1 (EE) represents emotive exhaustion, and it corresponds with the EE original sub-scale. Component 2 and Component 3 represent two aspects of PA: Component 2 (PA-W) collects items describing positive feelings about the work and Component 3 describes a positive emotional engagement with patients (PA-P). Finally, Component 4 and Component 5 define two aspects of DP: Component 4 (DP-W) expresses worries about personal hardening due to work and Component 5 (DP-P) describes the feeling not to be positively engaged with patients and their problems (Item 15 and 22).

Table 3. Rotated Component Matrix a for PCA

Note: Extraction Method = Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method = Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. Suppression of values <.4.

Abbreviations: DP, Depersonalization; EE, Emotional Exhaustion; PA, Personal Accomplishment; PCA, Principal Component Analysis.

a Rotation converged in six iterations.

The first two components had acceptable reliability (EE: α = 0.825; r = 0.34 and PA-W: α = 0.678; r = 0.3). Average inter-item correlation, but not Cronbach’s Alpha, resulted into the acceptable range for PA-P (α = 0.556; r = 0.29) and DP-W (α = 0.413; r = 0.21) components. The DP-P did not present sufficient reliability and internal consistency (α = 0.131; r = 0.07).

Exploratory Analyses

A large 83.3% (95% CI, 81.7% to 84.8%) of responders had positive feelings about their work, but only 42.7% (95% CI, 40.6% to 44.7%) felt engaged with patients during a week. While a small percentage of 2.5% (95% CI, 1.8% to 3.0%) of responders presented worries of personal hardening due to work, 11.5% (95% CI,10.1% to 12.8%) declared to feel disengaged with patients at least once a week.

Discussion

This sample was mainly constituted by males, in the middle age of 44 years, and with a mean of 12 years of career, in line with the sample analyzed by Argentero and Setti. Reference Argentero and Setti9

Some authors have recently shown differences in percentages of burnout detectable in emergency in-training doctors by applying a broad (80.9%) or a strict (18.2%) definition of burnout, Reference Lin, Battaglioli and Melamed29 as it was the case in this study. According to cut-off at the three factors, only 1.7% of the sample stayed in the classical and severe definition of burnout, in line with Angius. Reference Angius, Campana and Cattari10 The most in-depth look to latent burnout profiles Reference Leiter and Maslach3 revealed that more than two-thirds of the responders were struggling with some burnout patterns, similarly to percentages revealed on emergency nurses in an Italian sample Reference Cicchitti, Cannizzaro and Rosi30 and the meta-analysis by Gómez-Urquiza and colleagues. Reference Gómez-Urquiza, la Fuente-Solana and Albendín-García5 The latent burnout profile emerged was mostly disengagement, that was indicated as the minimum early phase of burnout; Reference Golembiewski and Munzenrider31 the most negative dimension among the burnout continuum and a more distinctive and central aspect of burnout than EE alone, according to Leither and Maslach. Reference Leiter and Maslach3 A negative perception of the teamwork was suggested as a variable highly associated to a disengaged and cynic burnout profile in nurses, Reference Duijts, Kant and Swaen25 as it was probably the case in this sample. During the psychological training, people referred highly conflictual relationship with nurses and physicians when working together, which they attributed to the under-consideration of their work experience from their colleagues; this is probably a consequence of the lack of a professional profile for this group of operators.

Additionally, 12.0% of the sample refers to a negative work experience of inefficacy, which could predict a future disengagement. Reference Leiter and Maslach3 The role of young age in a better engagement confirms previous studies. Reference Camerino, Conway and Heijden32,Reference Tomietto, Paro and Sartori33 The recodification of districts according to mean workload, and with sickness absence, did not influence the subjects’ classification in different burnout profiles differently from the previous researches. Reference Duijts, Kant and Swaen25,Reference Streiner27,Reference Crowe, Bower and Cash34

However, there were not specific data for each subject, so these modifiers had a different significance in this research than in previous studies.

There was a partial replication of the three dimensions of the MBI-HSS; the EE component was a more reliable sub-scale compared with DP and PA, as in the previous literature. Reference Sirigatti and Stefanile14,Reference Wheeler, Vassar and Worley19

However, the answers of this specific sample provided a better fit of the test by clustering in two sub-components for the PA and the DP factors, as compared to the original sub-scales.

The DP factor was particularly unreliable (also in Sirigatti and Stefanile Reference Sirigatti and Stefanile14 ), and it could have suffered from translation and wording issues or defensive responses, which drive to inconsistent answers, as already suggested in previous researches. Reference Loera, Converso and Viotti16,Reference Squires, Finlayson and Gerchow17,Reference Chao, McCallion and Nickle35

The analysis proposed a little increase of reliability if item 22 was deleted (also in Squires and colleagues Reference Squires, Finlayson and Gerchow17 ), but this did not raise reliability to the level of acceptability. Patient care stress is a primary source of daily stress for EMT workers. Reference Boudreaux, Jones and Mandry36 However, an extensive survey that included EMT American workers found a lower patient-related burnout in these subjects than in other Emergency Medical Services professions (5.0% versus 14.4%). Reference Crowe, Bower and Cash34 The DP-P component was analogously detected in a previous study by Chao and collaborators Reference Chao, McCallion and Nickle35 as a form of indifference for patients in a sample of American workers in a care staff of people with intellectual disability. Analogously to what measured in this latter study, a two-item solution is not likely to be reliable in itself and did not reach acceptable reliability in this sample. However, according to exploratory analysis, these two items were highly responsible for the elevation at the DP sub-scale (ie, a higher percentage of responders felt more disengaged with patients than presenting worries of personal hardening due to work). The PA-W component was very similar to the self-competence component, identified by Gil-Monte in a Spanish sample of different professional roles, Reference Gil-Monte37 and according to exploratory analyses, the majority of the present sample scored high these items, while subjects suffering from low PA presented a scarce engagement with patients (ie, low PA-P scores). Thus, these particular components’ loading could alternatively suggest a specific difficulty for driver-rescuers in interacting with patients.

An explicit focus on the emotional regulation and empathy skills in emergency physicians has been proposed, given its close influence on patients’ satisfaction Reference Holmes and Wang38,Reference Ali, Shayne and Ross39 and burnout prevention, Reference Carney, Mongelluzzo and Foster40 and this solution is probably highly auspicial also for the non-medical part of an emergency-staff during their first preparation and on-the-job training.

Limitations

The group administration could have biased some results; however, the district in which the information was collected did not influence the presence of different burnout profiles. The sampling strategy did not allow to collect data on gender and age for refusers that, in retrospect, should have been included; however, these responders’ characteristics were representative of the whole population, as compared with data from SEUS 118-service Human Resources office. The survey did not include the collection of variables which could have predicted different levels of burnout, such as sleep habits Reference Barger, Runyon and Renn41,Reference Patterson, Weaver and Frank42 and coping strategies, Reference Holland43 or psychiatric disorders and personality characteristics. Reference Adriaenssens, Gucht and Maes6,Reference Chng and Eaddy44,Reference Palmer and Spaid45 Additionally, there was not the opportunity to collect their exposure to traumatic work experiences, such as critical incidents, disasters, or patients’ death, which could have increased their stress levels Reference Ricciardi, Valsavoia and Russo46,Reference Donnelly47 and risk of burnout. Reference Crowe, Bower and Cash34,Reference Boerner, Gleason and Jopp48

To ensure anonymity, it was not possible to differentiate between single levels of leadership and responsibility (for example, in the specialization in the use of defibrillator) achieved by different driver-rescuers, since this could have affected stress levels. Nonetheless, this was a descriptive cross-sectional design, which did not include hypotheses on putative risk factors for the disease, but only some correlational post hoc explorative analyses.

Conclusions

Among responders, less than one-third appeared engaged in their work. However, the remaining part presented some form of burnout, particularly a disengagement profile, with a small 1.7% suffering from severe burnout. The three dimensions of the MBI were partially replicated, but it presented higher reliability in a final five-component loading. The EE scale loaded in an independent component. The PA factor resulted in five items concerning positive feelings about the work and three items about empathy with patients, which resulted in low scores in 60% of responders. The DP clustered in three items expressing hardening due to work, and two items about disengagement with patients. This last dimension appeared not reliable, but these two items registered more high-frequency answers than the other items.

These results endorse the importance of screening and psychological interventions for this population of emergency workers, where burnout could manifest itself more insidiously. It is also possible to speculate that sub-optimal empathy skills could be related to the disengagement and work-inefficacy feelings registered. Future research in this population could be focused on self-awareness of emotions rather than on broad burnout measurements and, consequently, specific psychological training should be pre-disposed to ensure better work experience and satisfaction.

Conflicts of interest

none

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X20000059