THE LIE OF THE LAND

The last five centuries BC witnessed rapid urban development in cities throughout the Mediterranean, where grand public spaces and monumental buildings enhanced their essential functioning and their prestige vis-à-vis rival states. Public construction was perceived as the responsibility and the hallmark of local ruling élites, usually monarchs, who gained visibility through architecture's physical presence and used construction to legitimize their status in at least two ways. First, their acts of benefaction improved standards of living for their subjects (as with, for instance, expensive water-distribution projects, like Pergamon's Madradag aqueduct, probably built by Eumenes II [197–159 BC]).Footnote 2 These were especially desirable and powerful in societies without welfare systems and public utility programmes; and in return, they entailed obligation. Second, through building, élites masterminded the spaces that framed daily rituals of life and élite power. Thus the centres of Hellenistic cities, such as Attalid Pergamon or Athens, were overhauled, beautified and made more habitable; in some cases (such as Priene), orthogonal planning lent space a rational air.Footnote 3

In Rome, things were different. In 182, so Livy claimed, a group of Macedonians ‘mocked … the appearance of the city, the public and private spaces of which were not yet embellished’;Footnote 4 even in 61, Cicero could imagine the Capuans' derision as they ‘laughed at and despised Rome, planted in mountains and deep valleys, its garrets hanging up aloft, its roads none of the best, by-ways of the narrowest’.Footnote 5 Lacking the ‘Hippodamian’ plan of some Greek cities and Roman colonies, and the open spaces of contemporaneous cities in Latium and Campania, Rome had no integrated design; characterized instead by isolated buildings and independent nodes, often grouped around the via triumphalis, it was experienced as something of a jumble, and certain categories of architecture (low-income housing, for instance, or sanitation) and measures to curb pollution or implement zoning, received little attention. Livy (and later Tacitus, at the start of the second century AD) ascribed the city's condition to a flurry of rebuilding after a great conflagration during the Gallic occupation of c. 390, though his reasoning gains little traction among scholars.Footnote 6 Indeed, recent assessments of literary and archaeological evidence conclude that the extent of any fire is exaggerated; seeking plunder rather than conquest, the Gauls targeted only private houses for destruction.Footnote 7

Scholarly assessments of Republican urbanism, while compelling and nuanced, tend to come at the issue from a different angle, tracing the diverse factors behind Rome's forward evolution rather than questioning what might have held it back. Filippo Coarelli tackles individual regions of the city, masterfully unpacking their topography and monuments;Footnote 8 Mario Torelli's analysis of the city's growth, meanwhile, offers reasoned explanations for different phases of its development from the Bronze Age to the end of the Republic, from a relative paucity of Republican building until the mid-fourth century due to a commitment to isonomia (equal rights before the law) among the political élite, to an uptick in architectural sponsorship caused by an urge for self-representation, especially at the end of the fourth century and as Rome spread through Italy; after a lull during the First and Second Punic Wars, and as Rome spread its reach through the Mediterranean, a surge of building accompanied the influx of wealth from foreign plunder and taxes, tempered at moments by a nationalistic mood; and in the final phase of the Republic, the self-promotion of outstanding generals led to massive urban initiatives that appealed to an urban populace seeking employment and entertainment.Footnote 9 The present paper does not dispute the importance of these political, imperialistic and social factors, which all fed into the city's growth in great measure; rather, it explores whether additional factors might account for the city's relative lack of large-scale grandeur and overall planning vis-à-vis its Mediterranean peers for most of the Republican era.

To address this question, Diane Favro floats the notion that Republican Romans were content with the city as a concept or, unlike Hellenistic monarchs, who had time and resources to build, lacked the motivation.Footnote 10 Other scholars, following Aristotle, who, in his Politics, argued that urban design and systems of government were interconnected, lay the blame for the city's ramshackle design at the feet of the Republican government;Footnote 11 thus Paul Zanker sees it as the result of élite ambition and ill-defined populism gone awry.Footnote 12 Olivia Robinson, meanwhile, spells out the issue more fully in terms of time constraints:

There was no disaster in the later Republic comparable to the Gallic sack which might have offered an opportunity of large-scale reconstruction. But the fundamental reason why a city planned as an entity could not be considered in Republican Rome was the constitutional arrangement of annual magistracies; even the censors, who had in theory five years in which to exercise their office, normally laid it down after some eighteen months. Such civil servants as there were, even though they seem sufficiently organised to have had some sort of a career structure, were too subordinate, too inferior to their political masters, the magistrates, to be in a position to formulate or sustain policies, even if they did act as guides through the daily routine.Footnote 13

Like Zanker and Favro, she characterizes the city's design as the accidental outcome of Republican government, an unintended corollary to the rapid turnover of magistrates.

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, for his part, concedes that so little of the Republican street plan is in evidence today that any assessment of it is by necessity speculative. Still, he notes that ‘the alternative to the “rationalism” of the grid-design is not irrational chaos, but systems that follow their own logic’.Footnote 14 Citing Spiro Kostof and other historians of urban design, he stresses the relationship between urban layout, on the one hand, and ideology and social structures on the other. Just as the broad boulevards of Renaissance Rome asserted papal authority for Julius II, Paul III and Sixtus V, and aided in riot suppression in Haussmann's post-revolutionary Paris, so labyrinthine urban plans can serve different types of social nucleation, based, for instance, in control by (quasi-)kinship, tribal or ethnic groupings, as evidenced in medieval cities such as Damascus, Mérida or Genoa, or in a need for protection against outsiders, as in squatter-towns in developing nations. ‘If late Republican Rome did not strike its inhabitants as a well-ordered city,’ Wallace-Hadrill concludes, ‘it may be that they had become blind to the earlier logic which underpinned it.’Footnote 15

That there was a logic seems more likely than apathy or accident. Indeed, this article contends that the state of Republican urbanism was the result of a deliberate system of checks and balances designed for the governing élite's self-regulation in the interests of the state's preservation. Unlike a monarchy, within the Republic, the élite struggled constantly to negotiate status with a voting public. Their understanding that visibility enhanced their electability and prestige must have made it all but irresistible to use architecture as a tool for self-advancement. Yet as K. Gast observed, epigraphical and literary evidence suggests that the sponsorship of public architecture, broadly defined here as architecture that served the state, through, for instance, religion, provision of civic amenity, or display of imperialism, was reserved for elected magistrates (the premise for Robinson's assessment), which prevented privati from deploying personal wealth on state construction (though their houses and tombs were their own concern).Footnote 16 Eva Margareta Steinby argues that these magistrates built at the senate's pleasure. The grand arc of Republican development was therefore the result of a senatorial plan, devolved onto censors and the aediles with an appropriate allocation of pecunia from the treasury: first came the construction of a seat for the censors and city fortifications, followed by a broad infrastructure initiative (streets and aqueducts) and development of the Forum and the port area; only with Cn. Pompeius Magnus (Pompey) and C. Julius Caesar was the senate transformed from the principal decision maker to a body that merely granted its consent.Footnote 17 That public building was the sole domain of magistrates is a fundamental premise of the present article; but the notion that these magistrates lacked any freedom in the choice of their initiatives lacks persuasive power. As Seth Bernard notes, ‘A tension between consensus and competition was fundamental to Republican political culture.’Footnote 18 Still despite their likely autonomy, magistrates were heavily constrained by the conditions of their offices and these conditions, explored below, had a direct impact on the city's development.

THE REPUBLIC'S DILEMMA

From the end of the sixth century to around the dissolution of the Latin League in 338, little public architecture was constructed, with the exception of temples (which were, nevertheless, monumental in scale, as evidenced in the Temple of Castor vowed by L. Postumius Albinus during the Battle of Lake Regillus, c. 496),Footnote 19 the Villa Publica on the Campus Martius as a base of operations for the first censors, C. Furius Pacilus and M. Geganius (c. 433),Footnote 20 and an amplification of the fortification walls by the censors of c. 378, Sp. Servilius Priscus and Q. Cloelius Siculus.Footnote 21 Across the board, these early public building initiatives were reactive, answering state crises such as war and famine, and they appear not to have been designed to distinguish their sponsors within their peer group: enclosing the city, the walls defined it as a community; so too did the headquarters for the census; and temples were extraordinarily homogeneous in form (frontal staircase, widely spaced façade columns, a porch leading to a triple or a single cella with solid lateral walls; gabled roofs, open pediments and painted terracottas). In this much, they support Torelli's notion of an ideal of isonomia among the élite. Still, these initiatives did articulate power relations within the city more broadly: where names are known, all public buildings were vowed or commissioned by patricians, who held a near monopoly on magistracies and priesthoods; and they were probably achieved through corvée labour (labour distrained upon the populace as a form of taxation).Footnote 22 With the Villa Publica, censors underscored their authority to stratify society in the census, and temples, in their uniformity, presented patrician solidarity at the top of the hierarchy. Thus public architecture articulated and protected the political élite's vision of an ideal state.

By the end of the fourth century, when plebeians broke the patrician stranglehold on power, when the nobility expanded and competition for political office intensified, construction began to gain pace, and a general scheme of magistrates' building privileges seems to have fallen into place. As part of a mandate to provide ludi, aediles sponsored entertainment venues, such as (probably) temporary theatres for plays and, in 329, starting gates or carceres at the Circus Maximus;Footnote 23 charged with maintaining the city's infrastructure, they undertook paving initiatives (such as the Clivus Publicius, surfaced by L. and M. Publicius in 238, to make the path up the Aventine cleaner and less arduous),Footnote 24 and they probably supervised minor building restorations from an early date. Though rare, their most ambitious projects were temples, funded using fines on the wealthy; L. Postumius Megellus may have been the pioneer of this practice, with a Temple of Victoria on the Palatine, built (according to Livy) using fines amassed as an aedile (probably before his first consulship in 305), and dedicated when he was consul in 294.Footnote 25 Consuls sponsored buildings as triumphatores, often using income from spoils; thus C. Duilius commemorated Rome's first victory on the seas during the First Punic War with the Temple of Janus of c. 260 (Fig. 1).Footnote 26 Most powerful, in building terms as in many others, but with least to gain in terms of career advancement, were the censors, who were responsible for letting contracts using state funds; they sponsored aqueducts, such as the Aqua Appia and the Anio Vetus (initiated by Appius Claudius in 312 and M. Curius Dentatus in 272, respectively),Footnote 27 and major roads like the via Appia (also by A. Claudius in 312).Footnote 28 Sometimes they turned their energies to public spaces, as C. Flaminius did by defining the Circus Flaminius in the southern Campus Martius in 218;Footnote 29 other significant enterprises, such as a third-century mint on the Capitoline and a prison (the carcer or Tullianum), were probably also censorial initiatives.Footnote 30 Dictators, for their part, engaged in construction only when it helped to resolve the emergency at hand (and thus Fabius Maximus strengthened the walls and towers under Hannibal's threat in 217).Footnote 31 With regard to agency, two additional points are worth stressing: the senate as a body never sponsored public buildings, except when answering the directives of the Sibylline Books, which, by definition, was in times of emergency; and in building as in other things, magistrates did not function as a board or a committee; they acted alone (with the exception of a few pairs of censors). Committees (usually duumviri or decemviri) were sometimes appointed to oversee certain aspects of construction, but only once sponsorship had been established.

Fig. 1. Temple of Janus, vowed in 260, actual state (© Penelope J. E. Davies).

Inherently, the system self-regulated through a set of further constraints. Unlike monarchs of the eastern Mediterranean, who could, as Favro notes, reasonably anticipate the fullness of their reigns to accomplish their goals, and who had the resources of the state at their disposal, magistrates had unusually brief terms of office — one year, or at most 18 months for a censor — and (unlike Pericles of Athens) no successive terms; moreover, the senate seems to have watched over their use of state resources. These conditions informed their building projects: in general plan and inception (though not completion) a single structure (such as a temple) was manageable; vast enterprises, massive orchestrations of urban space and urban programmes for broad popular appeal, of the kind that Hellenistic kings and later emperors could realize, were not. Though magistrates acted alone, in other words, in theory no single individual could be Rome's overarching benefactor or urban designer, and use that privilege to gain visibility or accrue obligation; thus conceived, in theory, the state, embodied in the senatorial élite, controlled public architecture tightly enough to prevent individuals from exploiting it to threaten the state.

Theory notwithstanding, magistrates developed strategies for manoeuvring within these constraints, which grew increasingly sophisticated with the passing of time. These included, inter alia, an emphasis on utilitarian euergetism that played to the plebeian voting bloc (as with Ap. Claudius' Aqua Appia, which conveyed an astounding 75,000 m3 of water a day to Rome's industries on the Aventine), naming privileges (the Aqua Appia again) and novel design and decoration (like Postumius Megellus' Temple of Victoria, possibly the first temple in Rome with a stone entablature).Footnote 32 There were topographical juxtapositions (seen in the series of temples known as Temples A to D in the area sacra at Largo Argentina (Fig. 2), probably augmented by three more temples to the south, and in the Temples of Janus, Juno Sospita and Spes in the Forum Holitorium),Footnote 33 and topographical appropriations and counter-appropriations, evident in efforts to control the via Appia region by, on one side, the Scipiones (with their tomb of c. 298 and a Temple to Tempestas in 259) and the Fabii (with the Temple of Honos, c. 233), and on the other the Claudii (with successive pavings of the road and the Temples of Honos and Virtus, 222–205).Footnote 34 Pervasive, too, were what might be termed architectural inter-texts, where buildings referred to and gained meaning from those that went before. But the most ambitious among these strategizers — Ap. Claudius, for one, or Postumius Megellus — were roundly castigated and obstructed.Footnote 35 And the effect of the state's ideal was that though individual initiatives enhanced the city, Rome was prevented from evolving with the grandeur of contemporaneous cities elsewhere. Such was the system, in fact, that Romans had set themselves up to choose between the security of their state on the one hand and the evolution, beautification and liveability of their city on the other — or at least to try to find a balance.

Fig. 2. Area sacra of Largo Argentina, hypothetical plan. (© John Burge).

In the wake of the Second Punic War, this conundrum grew more apparent. As Rome's status in the Mediterranean was enhanced, to many, Romans and visitors alike, its urban image must have seemed to lag behind.Footnote 36 As interactions with the impressive metropoleis of the Mediterranean intensified in the first half of the second century, moreover, as generals and their armies penetrated deeper into the east, the grandeur of other cities encouraged new models of urbanism. Problematically, Rome lacked the political set-up (and the high-quality stone) to enter the fray. At first, politicians upped the ante on individual buildings in terms of experimentation and monumentalization. Thus, for instance, basilicas erected by M. Fulvius Nobilior and C. Sempronius Gracchus (the Basilica Fulvia of 179 and the Basilica Sempronia of 169), with their elongated, porticoed plans, differed radically (so scholars believe) in form and scale from the domus-like Basilica Porcia of M. Porcius Cato in 184 (Fig. 3);Footnote 37 and in his Temple of Hercules Musarum on the Circus Flaminius of c. 187, Fulvius Nobilior seems to have conflated Greek design (a circular cella) with Roman design (a rectilinear frontal porch), to innovate on the more standard rectangular temple plan (Fig. 4),Footnote 38 while others individualized their buildings with paintings (as early as Iunius Bubulcus Brutus' Temple of Salus, at the end of the fourth century)Footnote 39 or sculpture (e.g. M.′ Acilius Glabrio's Temple of Pietas, dedicated in 181).Footnote 40 To give certain zones the appearance of an integrated urban design, some magistrates channelled energies into what William MacDonald termed ‘urban armatures’;Footnote 41 hence the sudden popularity of arches (first conceived by L. Stertinius at S. Omobono and the Circus Maximus on his return from Hispania Ulterior in 196)Footnote 42 and street-side porticoes, built in the emporium district by aediles in the late 190s, in disparate parts of the city by Fulvius Nobilior in 179, and in the Forum by the censors of 174.Footnote 43 And some achieved a monumental effect through successive initiatives: thus over the course of ten years the Basilicas Fulvia and Sempronia transformed the Forum from an Italic space into a grand public square articulated by majestic colonnades, of the kind that was rapidly becoming a Mediterranean koine,Footnote 44 and the joint initiatives of the same censors overhauled the port area into something resembling a rational scheme, with paved streets, wharves, stairways, bridges and porticoes.Footnote 45 Though conceived in a spirit of one-upmanship, these ventures articulated the state's ideal of collaboration. A compromise of sorts between state and city was achieved.

Fig. 3. Forum Romanum and environs, c. 133, plan. (© Penelope J. E. Davies).

Fig. 4. Temple of Hercules Musarum, as depicted on the Forma Urbis Romae, showing the Temple of Hercules Musarum at the lower left. From Carettoni et al. 1960, plate 29. © Roma, Sovrintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali.

A ‘CONCRETE REVOLUTION’

It was not to last. As political rivalry escalated around the mid-second century, some triumphatores (now consuls and praetors) brought literal reminders of Greece to Rome by importing marble for manubial temples. First to do so, so Velleius Paterculus states, was Q. Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus, conqueror of the Macedonian League in 148, who invited the architect Hermodorus, from Salamis on Cyprus, to design an all-marble temple to Jupiter Stator;Footnote 46 he was followed (probably) by his arch-rival, L. Mummius Achaicus, conqueror of Corinth and the Achaean League in 146, with a Temple of Hercules Victor, probably the Round Temple by the Tiber, built of Pentelic marble (Fig. 5).Footnote 47 The stone's bright luminosity enriched the city, and spoke of foreign lands and luxury, conquest and cultural advance. Alarmed by the threat posed by foreign influence, broadly conceived — the debilitating potential of luxury — the senate responded by striving in various ways to circumscribe Romanitas.Footnote 48

Fig. 5. Round Temple by the Tiber (Temple of Hercules Victor ?), vowed c. 146 (?), actual state (© Penelope J. E. Davies).

It was in an Italian fabric, however, that those who wanted to build on a massive scale found a brilliant way forward despite the state's restrictions. This fabric was opus caementicium, or concrete. Its component elements — aggregate, and mortar strengthened by pozzolana from the Alban hillsFootnote 49 — were inexpensive and easily available, and relatively unskilled labourers could work it faster than masons could cut and dress stone. Scholars recognize that its malleability gradually liberated architects to dream, whence MacDonald's ‘concrete revolution’ in architectural form;Footnote 50 yet as used in Republican Rome, its more radical significance, and the likely reason for its rapid ascent as a material for public architecture, is that, quick and economical, in one sweep it neutralized the primary determinants on magistrates’ construction ambitions: time and money. Other factors, noted by Torelli and others, coincided with its introduction to create the perfect storm: enormous wealth from foreign conquest and a vast unskilled (voting) workforce, whose employment constituted a benefaction in its own right. Its first datable use in Rome, according to Marcello Mogetta, is in the foundation the Porticus of Caecilius Metellus on the edge of the Circus Flaminius, conceived in the context of his bitter rivalry with Mummius and P. Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus Africanus, conqueror of Carthage in 146Footnote 51 — and immediately the advantages of the fabric are evident. Set around an existing Temple of Juno Regina and Caecilius Metellus' own marble Temple of Jupiter Stator, the portico's dimensions were unparalleled in Rome.Footnote 52 It comprised an unprecedented management of public space by a single individual; in the crowded city, it defined a place of peace and tranquillity, in the service of popularity-winning benefaction.

Without change to the state's restrictions on architectural sponsorship, with concrete magistrates' aspirations could adapt to new possibilities, and in relatively short order they built on a whole new scale. Outside the walls, for instance, a vast building was constructed at the foot of the Aventine, downstream of the commercial port. Inside, a forest of piers bore 200 barrel vaults set perpendicular to its long sides, defining a series of long narrow rooms that sloped towards the river.Footnote 53 Surviving tracts of wall (Fig. 6) correspond to a building shown on the Severan marble plan (fragments 23 and 24a–c: Fig. 7), with the partial label —LIA, long reconstructed as ‘Porticus Aemilia’, but a compelling hypothesis by Lucos Cozza and Pier Luigi Tucci, recognizing similarities to ship-sheds (neosoikoi) at various Mediterranean sites, identifies it instead as navalia.Footnote 54 Measuring, in its entirety, an extraordinary 487 m × 60 m, covering about 30,000 m2, it was far and away the largest covered structure in the city. If its identification as navalia is correct, it was most likely a public building and the work of a censor, perhaps M. Antonius, who, as praetor in 102–100, won a triumph against the pirates to secure the seas and the grain supply.Footnote 55

Fig. 6. Navalia (?), late second century, actual state. (© Penelope J. E. Davies).

Fig. 7. Forma Urbis Romae, from Carettoni et al. 1960, plate 24. © Roma, Sovrintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali.

More significantly, perhaps, magistrates could shape urban space more ambitiously, with complexes such as the late second-century restoration of the Sanctuary of Magna Mater on the Palatine, instigated by another member of the Caecilius Metellus family.Footnote 56 At the time of rebuilding, the sanctuary's platform was expanded and raised on a massive concrete barrel-vaulted substructure, which supported it beyond the natural contour of the hill to enlarge the setting for scenic games in honour of Magna Mater. In the process, the access path — the clivus Victoriae from the Forum Boarium — was radically altered: lowered and paved with silex, it was enclosed as a via tecta, with a walkway on the south. At the east end it met the Scalae Caci and veered north to ascend to the platform (Fig. 8). Thus reconceived, this magnificent sanctuary effected a scenographic reconfiguration of the landscape, where the whole was far greater than the sum of its parts;Footnote 57 like the contemporaneous Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia at Praeneste, it indulged an innovative vision for sanctuary planning, drawing on a Mediterranean design koine that favoured kinetic schemes, as seen at the sanctuaries of Asclepios at Kos and Athena Lindaia at Lindos, and in urban planning as evidenced at Pergamon.Footnote 58 These eastern sites impressed from afar; through changes of elevation, form and volumetric space, they controlled movement, framed vistas and, at times, offered sudden visual revelations; through their form, experience was masterfully stage-crafted.

Fig. 8. Sanctuary of Magna Mater, as restored in c. 102, hypothetical reconstruction. (© John Burge).

The restoration at the sanctuary of Magna Mater allowed the Caecilii Metelli to claim credit for victory against the Gauls at Vercellae in 102, a victory Cybele's chief priest, the Battakes, had attributed to Magna Mater; thus they shouldered out Marius, the populist hero who had really won the war.Footnote 59 But more than that, movement to and within the sanctuary was newly circumscribed, which served a broader agenda. Introduced to Rome from Phrygia in 205, the cult of Magna Mater sat at the far edge of élite self-identity, and by the time of the reconstruction its principal — and fervent — devotees seem to have belonged to Marius' constituency, the lower orders of society.Footnote 60 Raucous processions characterized the cult: priests in bright, luxurious robes, brandishing knives to symbolize their castrated state, begging for alms, and playing loud music to a strange metre; Phrygian Corybantes leaping about, shaking crested helmets and clashing armour; crowds of plebeians showering their path with money and roses.Footnote 61 With the restoration, these processions were contained; through concrete, the Caecilii Metelli imposed symbolic and physical authority on two forces embodied in the cult that threatened the mos maiorum: the non-Roman, and the escalating non-élite population. Born as competition — and chaos — in politics reached a crescendo, as tribunes explored the potential of their power as representatives of the non-élite, culminating in the aborted careers of the Gracchi, as the political consciousness of the people grew and the senate awoke to its possible weakness,Footnote 62 this new type of architecture staged experience; it manipulated, it persuaded.

The most overpowering early example of concrete construction, perhaps, and the most innovative, is the vast substructure bridging the Capitoline saddle (often known as the Tabularium), which transformed the landscape of the Capitol and the Arx and irrevocably altered an experience of the Forum below. Probably the commission of Q. Lutatius Catulus, consul of 78, and designed by the architect L. Cornelius, it was likely the base for a temple (to Juno Moneta?) or even three temples (Figs 9, 10).Footnote 63 Trapezoidal in plan, with an inset at the southwest corner for the Temple of Veiovis, it incorporates at least four distinct components. At the lowest level a corridor runs the length of the east flank, with a series of small chambers facing the Forum; at the south end, a staircase leads down to a doorway opening into an upper storey in the Southwest Building in the Forum, and another at the north end leads up to a suite of interconnected, travertine-paved rooms on the short side of the substructure.Footnote 64 Second, above the lower corridor, a monumental via tecta links the Capitol and the Arx, with massive arches framing views across the Forum and five rooms, probably shops, lining the west side.Footnote 65 Third, a large niche on the south side of the substructure contained remnants of a mud-brick hut, likely preserved as the house of Titus Tatius or Romulus;Footnote 66 and finally, a staircase runs through the substructure from the Forum to the Temple of Veiovis, and on to the temple terrace or to a second gallery and finally to the temple.Footnote 67

Fig. 9. Substructure on the Capitoline saddle, 78, actual state (© Penelope J. E. Davies).

Fig. 10. Substructure on the Capitoline saddle, begun in 78, plan. (© John Burge).

If Lutatius Catulus' complex responded to the Palatine structure, it was more daring in scale and in its transformation of the landscape: with its construction, political and sacred topography was radically reshaped.Footnote 68 Where a gentle valley had dipped between the Capitoline's peaks, the substructure blocked the way with a soaring vertical wall. Visually, it resumed the process of defining the Forum, which, highly politicized, was being lavishly repaved just as the substructure rose to completion.Footnote 69 On the north and south sides of the piazza, the colonnades and porticoes of the Basilicas Sempronia and Fulvia had earlier established permeable boundaries of light travertine and stuccoed tufo, a language of openness and access that had subsequently been appropriated for the Temple of Concordia and the Basilica Opimia of 121 now, on the west, the new substructure's solid surface, sheathed with unreflective Gabine and Alban stone, made an uncompromising backdrop for these icons of optimate triumph over the Gracchans. Its height and massiveness dignified the surmounting temple, but also marked a formal, authoritative separation of the Forum from a fortress-like Capitoline, as if to set religious space beyond popular grasp, a built expression of the return of priesthoods to co-optation during Sulla's dictatorship.Footnote 70

Within the substructure, in turn, where the Capitoline's natural contour receded to the west between the Capitol and the Arx,Footnote 71 an ancient path or staircase had probably led to the forecourt of the Temple of Veiovis, the entrance to the area Capitolina opposite and the Asylum beyond. The sights and sounds of the Forum and Capitoline would have encouraged lingering on this open-air climb, drenched in natural light. With the construction of the substructio, a steep staircase replaced the path, encased by concrete, dark and deafeningly silent (Fig. 11): access to the Capitoline was arduous and controlled, another architectural analogy for popular access to the gods. The via tecta, in turn, was a passage of a different order (Fig. 12). Roofed with soaring pavilion vaults, it formed a magnificent processional way for the final leg of the triumphal procession, and a link between the Arx and the Capitoline, two stages for the senate's self-presentation: the Auguraculum on the Arx, where augurs took the auspices with which state processes began, and the area Capitolina, the site of the capstone rituals of Republican government.Footnote 72 The grand arcade framed the pontiffs and augurs as they advanced in their regalia between functions on these two peaks, among them the most powerful senators of the day.Footnote 73 In the gallery, they stood above the fray, overseers with a privileged vantage point, and if the architecture's open form instilled in them a sense of responsibility and accountability, it must also have engendered a feeling of control. From the Forum where crowds assembled, meanwhile, the arcade drew the eye with its engaged half-columns and decorative entablature, outlining the actors in space (Fig. 9); the gallery embodied the notion of surveillance. In its totality, the complex projected an ideal vision of society and its hierarchies as conceived by Lutatius Catulus and his conservative peers, in which the senate held authority over all religious and political processes; into that vision, viewers were drawn.

Fig. 11. Substructure on the Capitoline saddle, 78, stairs from the Forum Romanum to the Temple of Veiovis, and from the Temple of Veiovis to the summit. (© Penelope J. E. Davies).

Fig. 12. Substructure on the Capitoline saddle, 78, via tecta (© Penelope J. E. Davies).

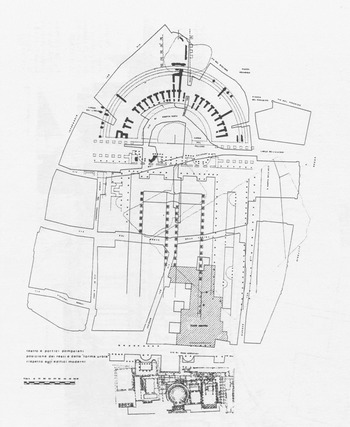

This, now, was the new language of political architecture. Though conceivable, architectonically, using cut stone, any of these monuments would have been prohibitively time-consuming and expensive for a Republican magistrate, working with the time and money constraints imposed by the senate. With concrete, scale shifted; simultaneously, agendas were proportionately re-dimensioned; and the persuasive, even theatrical, power of built form both to control and to promote became more manifest. Concrete, one might say, enabled transgression against the state. The implications of the shift, and its momentousness, become most apparent in Pompey's magnificent manubial initiative on the Campus Martius, begun in the aftermath of his spectacular triumph over Mithridates and dedicated in 55 and 52.Footnote 74 Combined within it were a theatre and a temple to Venus Victrix (Figs 13, 14); a portico framing a garden with formal plantings, shaded walkways and a sculpted fountain, and a senate house, all embellished with a multitude of art-works: not for Pompey to choose between different types of manubial monument as others had before him, but to build them all. At about 33,950 m2, in footprint the complex surpassed the city's largest buildings; and at about 45 m high — the altitude of the Arx — in vertical mass it rivalled the very hills of Rome.Footnote 75 Unlike Greek theatres, which nestled into hillsides, the cavea stood free of natural buttressing on the marshy plain; a concrete metaphor for Pompey's tendency to challenge norms throughout his meteoric rise through extraordinary commands, it was a miracle of construction. That he could think on such a scale and with such daring — understanding that completion was feasible within a limited time-frame (for though his commands were extraordinary, they were also finite) — was thanks, to be sure, to a wealth of manubiae and a vast, ready workforce; but neither would have sufficed to overcome the constraints of sponsorship norms without concrete.

Fig. 13. Forma Urbis Romae, from Carettoni et al. 1960, plate 32. © Roma, Sovrintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali.

Fig. 14. Theatre of Pompey, c. 62–52, hypothetical reconstruction. (© John Burge and James Packer).

That this project enhanced the city was undeniable. As a whole, it embodied the concept of luxury, as such complexes did in the East; and the permanent theatre placed Rome on a par with other cities of Italy and the Mediterranean, such as Pompeii and Mytilene, where Pompey reputedly found his model.Footnote 76 Yet the enhancement came at a price. The multitude of buildings assembled within it made it Rome in microcosm, built in Pompey's name, imbued with his presence, under his control. The complex was, unequivocally, a grand act of euergetism on the part of a single man. By now, theatres and porticoes were recognized as such, thanks to centuries of public entertainment and the Portico of Caecilius Metellus, but the public garden was a new contribution to the genre, drawing inspiration from places like Pergamon, where porticoed gardens, with formal plantings, water features and art displays were adjoined to theatres, gymnasia, palaistrai, philosophical schools and palaces. Inspired by regal paradeisoi of the Near East, first introduced to Greece by Alexander, the grandest, like the most magnificent theatres and porticoes of Greek lands, were royal benefactions.Footnote 77 In a city overcrowded with people — three-quarters of a million according to one estimate — most of whom lived in poverty, packed into squalid, noisy accommodations or lacking housing altogether, where private gardens were the privilege of the wealthy few, and buildings were encroaching on sacred groves, Pompey's gardens were a place of refuge, with shady promenades, the peaceful sound of running water and a museum of art-works people could call their own.Footnote 78 This grand benefaction embodied the popular benefit derived from Pompey's extraordinary talents to evoke a termless abstract authority that approached kingship.

In this vision, the theatre played a critical role. In 154, when the censors C. Cassius Longinus and M. Valerius Messalla had sponsored a permanent stone theatre, the senate had ordered it demolished and the parts sold at auction,Footnote 79 fearing, probably, for their authority in the running of state: a permanent place of assembly would empower the people to debate their own concerns, as they did in a Greek bouleuterion but not at the Roman Comitium;Footnote 80 and in Greek lands, it was in theatres, more than any other kind of building, that monarchs and strategoi — such as Demetrius Poliorcetes or Aratos, and later Mithridates — conflated drama and reality to frame and perform their leadership before their seated subjects.Footnote 81 With the people and the patron thus exalted, the senate risked a debilitating diminution of its prestige and influence.

At the theatre's opening ceremonies Pompey staged this new order. Throughout the city, in stalls of his providing, was his vast audience, ready to speak in favour of anyone who pleased them.Footnote 82 For their delectation there were musical and gymnastic contests, a horse race and five days of wild beast hunts in the Circus. Rare animals were imported, some for the first time, others in unprecedented numbers: sources record 500–600 lions, 410 leopards and Rome's first rhinoceros; there were rare monkeys too, and lynx, and vicious Gallic wolves. A hunt with eighteen elephants backfired when the audience sympathized with the beasts, but it was ‘a most terrifying spectacle’ nonetheless.Footnote 83 The scenic games to inaugurate the theatre featured plays in Latin, Greek and Oscan, and Pompey led popular actors out of retirement, one so old that his voice failed. The props were astounding: ‘a train of six hundred mules, … three thousand bowls, … [and] brightly-coloured armour of infantry and cavalry in some battle’, according to Cicero, which dazzled and delighted the crowd and vividly recalled the trappings of a triumph.Footnote 84 At the front of the cavea sat Pompey; before his assembled audience, in a building tailored to reflect his glory, the man who styled himself Alexander the Great staged a performance of the triumphal homecoming of Agamemnon to Argos in Accius' Clytemnestra, to evoke and re-enact the glory of his magnificent triumph of 61.Footnote 85 Through his theatre, he framed himself as king.

With Pompey's complex, a line was crossed. Not only had the scale of construction changed, but so, on the part of patrons, had expectations for how architecture might serve their goals and ambitions and, on the part of a growing electorate, for how politicians might craft the city to the people's advantage and enjoyment. So categorically was Pompey's complex a marker of power and a euergistic appeal for popular favour, and so overwhelmingly was it associated with a single authoritative individual, that it demanded a response, and the face-off between Pompey and C. Julius Caesar played itself out in architectural benefactions to the city well before it reached the battlefield. It was precisely through massive public works projects, inspired by the scale achievable through concrete construction, that, though removed from the city for fear of prosecution, Caesar established a surrogate presence before the people of Rome, with a magnificent rebuilding of the archaic ovile or voting precinct in marble as the Saepta Iulia that, at roughly 37,200 m2, would outsize Pompey's portico, only hundreds of metres away.Footnote 86 And he embarked on a Forum Iulium that, once completed, Pliny would compare to the pyramids of Egypt (Fig. 15).Footnote 87 A boon to the city and its inhabitants, his behaviour was deeply transgressive in a new way that reflects the urgency of the situation: he commissioned manubial buildings without any normative authority, before being granted a triumph, as what might be termed a presumptive triumphator. Where Pompey built with travertine-faced concrete, Caesar upstaged him: Rome's transformation into a city of marble had begun, a match for the dazzling cities of the east, and the material, from quarries close to his headquarters in Liguria, was the mark of a single man. Like Pompey's oeuvre, these magnificent enhancements to the city and the lived experience therein served Caesar's growing authority; and through the distinctions between their projects Caesar manipulated public perception of Pompey to secure his own position. Benefactions all, their buildings addressed chronic discontents with life in the city, but where Pompey aimed to seduce the crowd with spaces devoted to otium, Caesar's Forum, built for judicial negotium and the ovile, where the assembly met to vote for consuls, functioned at the heart of political business.Footnote 88 They exalted and expanded precisely the structures — the law, elections — that could help to provide solutions. They cast Caesar as an agent of change.Footnote 89

Fig. 15. Forum Iulium, begun c. 54, hypothetical reconstruction. (© John Burge).

When, in 46, Caesar was appointed dictator for ten years and then, in 45, for life,Footnote 90 he ascended to the very post that these massive urban initiatives had come to imply. In turn, the office removed all customary constraints, allowing him to usurp and conflate magistracies, to plan beyond time limits; and thus he gained the latitude to think in terms of a broad policy for the betterment of the city as no one had before. Many of his reforms addressed social issues, ‘to better the condition of the poor’, as Appian put it, and were particularly resonant in a city where residents paid no taxes and harboured low expectations of the state.Footnote 91 His reforms were not directed at quick solutions and instant favour but at long-term practical objectives: securing the corn supply, dealing with widespread debt, and reducing urban violence.Footnote 92 For his architectural plans, the assured longevity of his rule obviated the need for rapid concrete construction; even without it, his intentions could, and did, approach the programmatic: he paid homage to the gods (planning a temple to Mars, as well as his temple to Venus Genetrix),Footnote 93 provided entertainment venues, such as a refurbished Circus Maximus, the first known artificial lake in Rome for mock sea-battles, and two theatres in the planning, one on the east slope of the Arx, the other near the Circus Flaminius, west of the Capitoline, which would be completed eventually as the Theatre of Marcellus;Footnote 94 and he overhauled the spaces of politics, relocating the Rostra to give the Forum a logical axis (and to sideline the senate).Footnote 95 Inspired, presumably, by his sojourn in Alexandria, he also intended ‘the greatest possible libraries of Greek and Latin books' (as Suetonius put it), where public recitals would likely have occurred, giving the plebs access to information and luxuries hitherto reserved for the élite, and making the city a centre of culture and learning.Footnote 96 And he addressed the root causes of the problems plaguing the non-élite: for some he remitted exorbitant rents; and to make more land available, he auctioned public properties, extended the pomerium (possibly), and even planned to divert the Tiber west of the Vatican Hills, more than doubling the Campus Martius area with land assigned to housing.Footnote 97 His compilation of regulations for municipal administration prescribed street maintenance and traffic control, and banned construction in public areas. In short, he aspired to aggressive changes that would strike at the heart of the urban experience, to make the city more ‘liveable’, and at the same time, increase its grandeur and appeal as a cultural centre. At last a politician approached the city with a policy, as its mastermind; and this, precisely, underlined the a-constitutionality of his role in a republic.

During the Republic, architecture and politics were inextricably intertwined. A necessary corollary of controlling exploitation of urban development by individual politicians to protect the state was a city lacking the monumental quality of contemporaneous Mediterranean kingdoms. Initial strategies to push the limits in architectural sponsorship enriched Rome in beauty and scale, while causing little threat to the delicate balance that Polybius so admired. But concrete, which neutralized the primary determinants on magistrates’ construction ambitions — time and money — released them from state control; when politicians realized its potential, and the city, as an architectural and urbanistic entity, could finally flourish, the Republic, as an ideal state, existed no more.