INTRODUCTION

Despite significant gains in the relative 5-year survival rates for most cancers (Coleman et al., Reference Coleman, Quaresma and Berrino2008; Canadian Cancer Society National Cancer Institute of Canada, 2010; Jemal et al., Reference Jemal, Siegel and Xu2010), public perceptions about the survivability of cancer are less optimistic, often still being equated with death (Donovan et al., Reference Donovan, Jalleh and Jones2002, Reference Donovan, Carter and Byrne2006; Holland et al., Reference Holland, Kelly and Weinberger2010). In fact, existential concerns generally lie latent in the general population (Becker, Reference Becker1973; Neimeyer et al., Reference Neimeyer, Wittkowski and Moser2004), and awareness about the fragility of life and the inevitability of death only heighten when individuals are exposed to cancer-related cues (Benyamini et al., Reference Benyamini, McClain and Leventhal2003; Klein & Stefanek, Reference Klein and Stefanek2007; Lipworth et al., Reference Lipworth, Davey and Carter2010).

Existential concerns are expected to influence behavior at any point of the cancer trajectory from relative adoption of illness-preventive actions, follow-up with cancer screening recommendations, and adherence to treatment modalities, to survivorship care. The purpose of this article is to capture the significance and ramifications of cancer-related existential issues across the cancer control continuum by proposing the Temporal Existential Awareness and Meaning Making (TEAMM) model. This tripartite model draws on key literature to delineate three distinct clinical presentations of existential awareness related to cancer. A discussion highlights the clinical and research implications of the TEAMM model for person-centered cancer care.

Distinguishing Between Existential Awareness and Existential Distress

A cancer diagnosis is often viewed as a pivotal life event, when the inevitability of one's own personal death becomes undeniably clear (Coyle, Reference Coyle2004). “Existential awareness” is the awareness of one's mortality and refers to what has been commonly called “mortality salience” in the literature (Burke et al., Reference Burke, Martens and Faucher2010). Existential awareness triggered by a cancer experience involves the contemplation of personal identity, autonomy, dignity, life meaning and purpose, and connections with others within the context of life and death (Frankl, Reference Frankl1959; Bolmsjo, Reference Bolmsjo2000; Griffiths et al., Reference Griffiths, Norton and Wagstaff2002).

On the other hand, “existential distress” refers to what has been commonly called “death anxiety” (Pyszczynski et al., Reference Pyszczynski, Greenberg and Solomon1997) or “existential suffering” (Schuman-Olivier et al., Reference Schuman-Olivier, Brendel and Forstein2008). The distress evoked by a cancer diagnosis often results from a subjective appraisal of a threat to one's life (Folkman et al., Reference Folkman, Lazarus and Gruen1986) and not necessarily by more objective indices such as disease progression or prognosis (Cella & Tross, Reference Cella and Tross1987; Laubmeier, Reference Laubmeier and Zakowski2004). Existential distress has been shown to be a separate construct from general anxiety, depression, somatic distress, and global psychological distress (Cella & Tross, Reference Cella and Tross1987; Lichtenthal et al., Reference Lichtenthal, Nilsson and Zhang2009) and has been shown to correlate with time since diagnosis and closeness to death (Weisman & Worden, Reference Weisman and Worden1976–77; Cella & Tross, Reference Cella and Tross1987; Lichtenthal et al., Reference Lichtenthal, Nilsson and Zhang2009).

Studies indicate that individuals with advanced cancer who have an accurate prognostic awareness are not necessarily distressed (Blinderman & Cherny, Reference Blinderman and Cherny2005; Barnett, Reference Barnett2006; Lichtenthal et al., Reference Lichtenthal, Nilsson and Zhang2009). Therefore, existential awareness does not necessarily lead to existential distress (Blinderman & Cherny, Reference Blinderman and Cherny2005). The appraisal of life threat from cancer can be construed on a continuum that ranges from a normative acceptance that is not necessarily upsetting to incrementally distressing levels characterized by ruminative thoughts and feelings of demoralization, meaninglessness, and isolation (Lee, Reference Lee2008).

Memento Mori Footnote 1 and the Need for Meaning in the Context of Cancer

Cancer is perhaps one of the most timeless representations of memento mori in health and illness (Donovan et al., Reference Donovan, Jalleh and Jones2002). Research into the existential unrest evoked by cancer was initially treated in the seminal work of Weisman and Worden (1976–77), which described a predominance of life and death concerns in the first 100 days following the diagnosis. Not surprisingly, existential concerns permeate the acute and survivorship stages of cancer. There is a preponderance of articles about the existential concerns at end of life and palliative care phases of the cancer trajectory. However, the literature is also suggesting the important influence of existential issues on cancer screening and preventive behaviors such as breast self-examination and mammography (Goldenberg et al., Reference Goldenberg, Arndt and Hart2008, Reference Goldenberg, Routledge and Arndt2009), smoking cessation (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Winzeler and Topolinski2010), adherence to protective skin cancer behaviors (Cameron, Reference Cameron2008; Garside et al., Reference Garside, Pearson and Moxham2010); uptake of fecal occult blood testing (Chapple et al., Reference Chapple, Ziebland and Hewitson2008), and genetic testing for cancer (Esplen, Reference Esplen2003).

Terror Management Theory (TMT) proposes that individuals have a basic instinctual drive for survival and self-preservation (Greenberg et al., Reference Greenberg, Arndt and Simon2000). When confronted with the idea of one's potentially imminent and inevitable death, individuals commonly rely on the use of proximal defense mechanisms (e.g., denial, distraction, avoidance, and cognitive distortion) or the use of distal defense mechanisms (e.g., efforts to maintain a sense of meaning, purpose, and permanence) to cope with the thought of one's potential nonexistence.

A burgeoning body of evidence exists to support the notion that many individuals search to reconstruct a sense of meaning in the face of life's tragedies (Frankl, Reference Frankl1959; Taylor, Reference Taylor1983; Thomson & Janigian, Reference Thomson and Janigan1988; Park & Folkman, Reference Park and Folkman1997; Breitbart, Reference Breitbart2002; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Cohen and Edgar2004, Reference Lee2008; Park, Reference Park2010). Patients with life-altering cancer diagnoses and treatments often cannot look to a cure to relieve their anxieties and to restore equanimity (i.e., proximal defense mechanisms can be effective only up to a certain point). Instead, individuals with cancer often benefit from a new integration of the meaning of the illness into their lives. Efforts to facilitate this exploration of meaning or “meaning making” has recently been welcomed with a high degree of consensus by theorists, researchers, and clinicians who advocate for the importance of “meaning” in the context of cancer and other highly stressful life experiences including a potential, actual, or recurrent cancer diagnosis that challenges one's existence (Folkman & Greer, 2000; Park, Reference Park2010 for an extensive review). A broader appreciation of the existential issues across the cancer control continuum can inform the targeted development of meaning-oriented approaches to support health-protective lifestyle behaviors and early cancer detection, as well as actual experience with cancer.

METHODS

A literature search pertaining to the existential discourse of the adult patient and cancer was conducted using the databases ISI Web of Knowledge, Medline, and PsychInfo for articles published in the English language between 1975 and 2010. The following search terms were used: “existential” in combination with “cancer,” “meaning making,” “death anxiety,” “terror management,” “risk,” “prevention,” “screening,” “genetics,” “end of life,” and “palliative.” Articles with a focus on children, adolescents, caregivers, family, and health professionals were excluded.

The cancer control continuum (National Cancer Institute, 2007; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Bowen and Croyle2009) was selected to organize the predominant existential themes emerging from the literature search. The cancer control continuum was chosen for its broad definition of the cancer experience that begins earlier than at diagnosis, and for explicitly including the existential domain within the psychosocial issues that cut across different types of cancer diagnoses. The articles retrieved were closely read to identify (1) the foci and the gaps along the cancer control continuum in terms of existential discourse in cancer, and (2) the dominant themes emerging from the existing discourse.

RESULTS

Temporal Existential Awareness and Meaning Making (TEAMM) Model

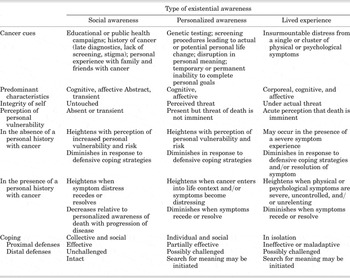

The TEAMM model provides a guide to understanding how cancer-induced existential awareness can affect individuals across all phases of the cancer control continuum (National Cancer Institute, 2007; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Bowen and Croyle2009). Three dominant themes were extrapolated from the literature to represent three types of cancer-related existential awareness: a social awareness, a personalized awareness, and a lived experience of cancer's threat to life (Fig. 1). According to the literature, these three types of existential awareness are found to: (1) extend across any phase of the cancer control continuum (including individuals who are cancer free), (2) co-occur in varying intensities, and (3) be heightened or mitigated by one's repertoire of coping strategies. Table 1 presents a clinical classification system to summarize the unique defining attributes for each type of cancer-related existential awareness. This system proposes that each type of existential awareness is differentially triggered by distinct cues, affects one's sense of personal identity, and is managed differently through proximal or distal defense mechanisms. Figure 2 offers a pictorial representation of how individuals might confront, manage, and alternate among the different types of existential awareness across each phase of the cancer control continuum. The TEAMM model is an extension of the study findings of Little and Sayer (2004), which describes how individuals are rendered “mortality salient” upon initial diagnosis of cancer, “death salient” when in remission, and “dying salient” when close to death.

Fig. 1. Three types of existential awareness from cancer's threat to life.

Fig. 2. Predominant types of existential awareness across phases of the cancer control continuum.

Table 1. The Temporal Existential Awareness and Meaning Making (TEAMM) model

A Social Awareness of Cancer's Threat to Life (“Cancer Signals Death”)

The “cancer equals death” equation is a universal belief that is held even by individuals free of cancer (Borland et al., Reference Borland, Donaghue and Hill1994; Donovan et al., Reference Donovan, Jalleh and Jones2002; Benyamini et al., Reference Benyamini, McClain and Leventhal2003; Peters et al., Reference Peters, McCaul and Stefanek2006). Social awareness of death from cancer is often seen as a transient, unspoken acknowledgement of potential death from cancer described by experts in the field as the “elephant in the room” (Knapp-Oliver & Moyer, Reference Knapp-Oliver and Moyer2009; Holland et al., Reference Holland, Kelly and Weinberger2010; Lipworth et al., Reference Lipworth, Davey and Carter2010). Educational and public health campaigns that aim to eradicate cancer or enhance the quality of life of people affected by cancer are examples of the explicit acknowledgement of cancer's threat to life. Social expressions of cancer fears are also implicit in the stigma and shame that remains with certain types of cancers on the basis of anatomical location (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Fitch and Phillips2000; Madlensky et al., Reference Madlensky, Esplen and Goel2004; Rosman, Reference Rosman2004; Chapple et al., Reference Chapple, Ziebland and Hewitson2008; Else-Quest et al., Reference Else-Quest, LoConte and Schiller2009) or perceived personal responsibility (Chapple et al., Reference Chapple, Ziebland and McPherson2004; Bell et al., Reference Bell, Salmon and Bowers2010; Gulyn & Youssef, Reference Gulyn and Youssef2010).

Research has shown that the strong negative affect elicited by cancer cues are transient because such cues activate protective coping mechanisms, namely, optimistic bias, denial, or avoidance, to suppress a rising awareness of the threats associated with cancer (Arndt et al., Reference Arndt, Greenberg and Simon1998, Reference Arndt, Cook and Goldenberg2007; Benyamini et al., Reference Benyamini, McClain and Leventhal2003; Lipworth et al., Reference Lipworth, Davey and Carter2010). The use of proximal defence mechanisms that minimize risk perception and vulnerability, for example, have been reported even amongst individuals who have a family history of cancer (Benyamini et al., Reference Benyamini, McClain and Leventhal2003; Madlensky et al., Reference Madlensky, Esplen and Goel2004). Other defensive behaviors include social distancing from individuals with cancer (Mosher & Danoff-Burg, Reference Mosher and Danoff-Burg2007) and avoidance or delay in seeking treatment (Tod & Joanne, Reference Tod and Joanne2010). When these coping mechanisms are activated, cancer is not explicitly appraised as personally life threatening. One's worldview remains relatively intact, and there is no perceived need to search for meaning (i.e., distal defense mechanisms are not affected) (Park & Folkman, Reference Park and Folkman1997; Thomson & Janigian, 1988; Park, Reference Park2010).

A Personalized Awareness of Cancer's Threat to Life (“I Could Die from Cancer”)

When cancer cues threaten the sense of order and purpose in one's own life context, cancer can no longer be perceived as an abstract illness that only happens to others. The individual enters into a personalized awareness of death from cancer. This awareness leads to a subjective appraisal of personal threat to one's integrity that does not necessarily correlate with objective signs of disease progression or prognosis (Blinderman & Cherny, Reference Blinderman and Cherny2005; Barnett, Reference Barnett2006; Lichtenthal et al., Reference Lichtenthal, Nilsson and Zhang2009). Individuals attempt to reconcile their own existence with the inevitable state of nonexistence upon death. The awareness of a personal life threat from cancer commonly occurs upon initial confirmation of a cancer diagnosis (Weisman & Worden, 1976–77; Derogatis, Reference Derogatis, Morrow and Fetting1983; Landmark, Reference Landmark, Strandmark and Wahl2001). However, a personalized awareness of death may also be evoked early in the absence of a personal history of cancer if significant distress is triggered by cancer cues related to screening procedures, genetic testing, or vicarious experiences involving others with cancer (Benyamini et al., Reference Benyamini, McClain and Leventhal2003; Peters et al., Reference Peters, McCaul and Stefanek2006; Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Campbell and Donovan2007). For others, the realization of one's own potential death from cancer may only develop later when the individual faces a progression, recurrence, or exacerbation of disease (Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Bergbom and Bosaeus2002; Richer & Ezer, Reference Richer and Ezer2002; Sarenmalm et al., Reference Sarenmalm, Ohlen and Jonsson2007; McClement & Chochinov, Reference McClement and Chochinov2008; Mehnert et al., Reference Mehnert, Berg and Henrich2009). Thus, a personalized awareness of death occurs when a cancer cue is appraised as personally threatening to one's survival.

In the absence of illness, the appraisal of life threat from cancer can be managed through the use of proximal defense mechanisms (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Campbell and Donovan2007; Lipworth et al., Reference Lipworth, Davey and Carter2010). In the presence of actual disease, cancer progression, or debilitating side effects from treatment, it is hypothesized that the effectiveness of proximal or distal defenses may diminish as it becomes increasingly difficult to deny or minimize the impact of cancer on one's sense of integrity (Zimmermann, Reference Zimmermann2004, Reference Zimmermann2007; Zimmermann & Rodin, Reference Zimmermann and Rodin2004). Individuals commonly cope by actively searching for a set of beliefs that can return a sense of order and permanence, as well as self-esteem and personal value, in the face of potential death from cancer (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Lichtman and Wood1984; O'Connor et al., Reference O'Connor, Wicker and Germino1990; Ruff Dirksen, Reference Ruff Dirksen1995; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Cohen and Edgar2004; Quinn, Reference Quinn2005; Kernan & Lepore, Reference Kernan and Lepore2009).

The Lived Experience of Cancer's Threat to Life (“It Feels Like I Am Dying from Cancer”)

The lived experience of death from cancer is posited as a corporeal, cognitive, and affective awareness of one's proximity to death. This transient sense of “living while dying” is theorized to occur when the perceived severity of a single or a cluster of physical or psychological symptoms exceed one's resources and are considered insurmountable by the individual (Kissane & Clarke, Reference Kissane and Clarke2001; Armstrong, Reference Armstrong2003). The perception of proximity to death is theorized to diminish when patients experience symptom relief from treatment or when they receive effective palliative care (Knuti et al., Reference Knuti, Wharton and Wharton2003; Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom, Furst and Friedrichsen2009). Therefore, the lived experience of death can occur at any point along the cancer continuum depending upon the appraised severity and cause of the symptoms. For example, when patients experience fatigue, anorexia, and weight loss, they may appraise this symptom cluster as worrisome in the pre-treatment phase but normalize it as an expected side effect in the active treatment phase. If the symptom cluster continues to be unrelenting and uncontrolled, the patient may interpret it as a sign that the disease is progressing and that death is approaching in the post-treatment phase (Poole & Froggatt, Reference Poole and Froggatt2002; Lindqvist et al., Reference Lindqvist, Widmark and Rasmussen2004; Potter, Reference Potter2004; McClement, Reference McClement2005; Wainwright et al., Reference Wainwright, Donovan and Kavadas2007).

Individuals who are living cancer's threat to life cope by isolation and social withdrawal, and a characteristic “turning inwards” (Little & Sayers, Reference Little and Sayers2004). For some, the “lived experience” may be the final impetus to begin the process of meaning-making as a coping strategy to alleviate the distress generated by awareness of one's imminent death. Past research has demonstrated that the use of avoidant-type coping styles may be associated with greater anxiety and distress (Watson et al., Reference Watson, Greer and Blake1984; Carver, et al., Reference Carver, Pozo and Harris1993). Current therapeutic approaches with a strong existential orientation such as meaning-centered interventions are yielding significant benefits on standardized measures of psychosocial well-being, particularly for individuals at the end of life (Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Bloch and Smith2003; Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005a; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Cohen and Edgar2006; Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Gibson2010; Henry et al., Reference Henry, Cohen and Lee2010). Therefore, therapeutic interventions that facilitate the process of meaning-making during the cancer experience are providing early evidence that the reformulation of distal defense mechanisms protects against death anxiety.

DISCUSSION

Balancing the Will to Live and the Fear of Death

The struggle to understand how one can continue to live knowing that death is imminent from cancer is a common paradox reported by many individuals with cancer (Halstead & Hull, 2001) and can be explained by the co-occurrence of the three types of awareness. When different states of death awareness occur simultaneously, the focus on self-preservation and self-integrity is expected to predominate. Therefore, as depicted in the different scenarios in Figure 2, the “lived experience” of cancer's threat to life is hypothesized to trump a “personalized awareness” of death from cancer. Similarly, in the absence of a corporeal experience of cancer, a “personalized” awareness of death from cancer is likely to compete with or overshadow a “social awareness” of cancer's threat to life. Alternatively, the “social awareness” of cancer's threat to life is hypothesized to regain strength and importance as symptoms resolve and individuals refocus their efforts on goals other than their own survival. These experiences do not necessarily follow a straightforward trajectory, as illustrated in Figure 2. The notion of relative intensity depicted by the three types of awareness is corroborated by a number of rich, descriptive studies in which people may feel as if they are swinging back and forth on a pendulum (Halstead & Hull, 2001; Giske & Artinian, Reference Giske and Artinian2008; Sand et al., Reference Sand, Olsson and Strang2009).

Impact on Cancer Control Efforts

The TEAMM model outlines how existential concerns (conscious or unconscious) can influence the cancer symptom experience, and shape behaviors related to the perception of cancer risk and adjustment to the cancer experience. The ability to manage one's existential concerns related to the fear of cancer directly influences how patients make treatment decisions, including whether to adopt, adhere, delay, or forego uncomfortable or invasive procedures for cancer control (de Nooijer et al., Reference de Nooijer, Lechner and de Vries2003). Existential concerns influence and are influenced by the interpretation of symptoms (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong2003; Lindqvist et al., Reference Lindqvist, Widmark and Rasmussen2004; Lundstrom et al., Reference Lundstrom, Furst and Friedrichsen2009).

Emotions, fears, beliefs, and other personally relevant factors often come into play during the illness experience (Bekker, Reference Bekker2010). Research shows that individuals respond selectively to cancer cues: some may be fatalistic in their interpretation of perceived personal risk, whereas others are not (Hurley et al., Reference Hurley, Du Hamel and Vickberg2002). Individuals with a high fear of cancer may interpret ambiguous symptoms with a negative bias (Miles et al., Reference Miles, Voorwinden and Mathews2009). They may be more motivated to engage in behaviors to protect one's integrity and survival, whether by adhering to cancer screening practices or by actively searching for meaning (Andersen & Cacioppo, Reference Andersen and Cacioppo1995). For example, researchers (Audrain et al., Reference Audrain, Lerman and Rimer1995; Lerman et al., Reference Lerman, Seay and Balshem1995) have demonstrated that women were more motivated to undergo mammography when they held inaccurate and biased views of cancer risk that heightened their fear of death. For other individuals, new and unexpected symptoms are tempered by an optimistic bias to block the unpleasant thought of one's potential for death by minimizing individual risk perceptions or reframing them as transient, self-correcting conditions (Andersen & Cacioppo, Reference Andersen and Cacioppo1995). Aversion and low adherence rates to certain cancer screening procedures or behaviors that involve deliberate and explicit bodily manipulation and /or physical discomfort such as breast self examinations, mammography, fecal occult blood testing, or sigmoidoscopy have been linked to reminders of one's “creatureliness” (Madlensky et al., Reference Madlensky, Esplen and Goel2004; Chapple et al., Reference Chapple, Ziebland and Hewitson2008; Goldenberg et al., Reference Goldenberg, Arndt and Hart2008, Reference Goldenberg, Routledge and Arndt2009; Garside et al., Reference Garside, Pearson and Moxham2010). Of particular interest is the work of researchers who document that explicit messages warning of the link between cancer and death may have the unintended opposite effect of increasing willingness to continue smoking particularly among individuals whose self-esteem is enhanced by smoking (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Winzeler and Topolinski2010). Clearly, individuals' motivations to comply, delay, or reject cancer prevention practices is complex and related to existential concerns. The challenge for clinicians and public health professionals lies in marketing cancer control information in ways that invoke optimal levels of existential awareness so that individuals are motivated to undergo screening tests and behavior change (Klein & Stefanek, Reference Klein and Stefanek2007).

Promotion of Existential Awareness

The evidence thus far indicates that once initiated, existential awareness persists over time. However, this awareness may vary in intensity, depending upon symptom severity, disease progression, and the experience of hope and meaning in life. For some, the salience of one's own mortality coupled with symptom distress and an uncertain view of the future, can be distressing and immobilizing, and can even influence the desire for hastened death (Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Pessin2000; McClain et al., Reference McClain, Rosenfeld and Breitbart2003; Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005b). For others, awareness of one's mortality may have adaptive value by dramatically changing one's life priorities to initiate the phenomenon of post-traumatic growth (Cordova et al., Reference Cordova, Cunningham and Carlson2001; Tedeschi & Calhoun, Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun2004; Bellizzi & Blank, Reference Bellizzi and Blank2006; Holland & Weiss, Reference Holland and Weiss2008; Jim & Jacobsen, Reference Jim and Jacobsen2008; Park, Reference Park2008; Park et al., Reference Park, Blank and Edmondson2008). Thus, the paradox of death awareness lies in its potential to be both psychologically paralyzing and instrumental in mobilizing a tenacious will to live. Several studies demonstrate that individuals with cancer have unmet existential needs, are not distressed by existentially oriented discussions, and would like to have more existential discussions with their treating team (Moadel et al., Reference Moadel, Morgan and Fatone1999; Blinderman & Cherny, Reference Blinderman and Cherny2005; Lichtenthal, 2009).

The challenge in cancer control efforts lies in developing theory-based approaches to capitalize on the potential functional value of existential awareness. A number of novel evidence-based interventions that buffer against existential distress are available from the literature in the fields of mental health and palliative care (Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Bloch and Smith2003; Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005a; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Cohen and Edgar2006; Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Gibson2010; Henry et al., Reference Henry, Cohen and Lee2010). Innovative interventions can evolve from these existing approaches to promote clinically appealing cancer control interventions. Clinicians can use the TEAMM model to understand when each type of existential awareness is most salient and facilitate the use of coping strategies most appropriate to that specific type of awareness (Little & Sayers, Reference Little and Sayers2004; Klein & Stefanek, Reference Klein and Stefanek2007). The literature suggests that most individuals have the psychological resilience to cope with the awareness of death that cancer evokes. This means that existential discussions need not be delayed until the advanced stages of cancer or at end of life, but should take place when the need arises.

Existential discussions in the context of cancer control and cancer care need not be intense, philosophical, or time consuming (Blinderman & Cherny, Reference Blinderman and Cherny2005; Kvåle, Reference Kvåle2007). When these discussions are introduced in a non-threatening, secular manner, they can become an integral part of many comprehensive cancer control interventions. Existential exchanges communicate a sense of value and respect for the individual, and can build trusting relationships that can influence subsequent critical health decisions. Timely referrals for assessment and services can be provided when the patient's needs exceed the clinician's resources, capability, or personal comfort (Holland & Reznik, Reference Holland and Reznik2005; Surbone et al., Reference Surbone, Baider and Weitzman2010).

The proposed TEAMM model offers a starting point to broaden our understanding of how patients respond to the threat to life across the pre-disease and disease phases of the cancer control continuum. We raise four areas amenable to further research: (1) further validation of the three types of existential awareness proposed in the model through in-depth qualitative exploration with case series or longitudinal designs, (2) further exploration of the temporal relationship between existential awareness and symptom distress (i.e., how do existential issues influence and how are they influenced by the symptoms experience?), (3) exploration of the cross-cultural relevance of the TEAMM model, and (4) development and evaluation of novel meaning-oriented interventions aimed at encouraging uptake of cancer screening and preventive practices.

CONCLUSIONS

The TEAMM model relies on a broad spectrum of scientific knowledge to propose an evolving understanding of existential issues as they apply to person-centered care, and lays the foundation for further exploration, research, and discussion. Models of cancer control pertaining to existential distress have not previously included the pre-disease or early disease phases (Nolan & Mock, Reference Nolan and Mock2004; Knight & Emanuel, Reference Knight and Emanuel2007; Schuman-Olivier et al., Reference Schuman-Olivier, Brendel and Forstein2008). Existential discussions are pertinent across the entire cancer control spectrum and do not need to be deferred until the advanced stages of cancer or at end of life. The TEAMM model contributes to the notion of the cancer control continuum by furthering understanding about the role of existential awareness even in the earlier, disease-free, phases of the cancer control continuum.

Rowland and Baker (Reference Rowland and Baker2005) eloquently state that “Being disease free does not mean being free of the disease.” This idea captures the long-lasting and pervasive impact of cancer (potential or actual) and its diverse effects on affected individuals and families across the life span. This article extends this proposition to suggest that existential issues evoked by cancer, an illness that epitomizes death, can be as powerful and pervasive in the pre-disease and early disease phases as they are in the survivorship and end-of-life phases. It is our hope that if the existential fear of dying from cancer is directly and sensitively addressed with knowledge, compassion, and care, that this, in turn, will help improve patient–provider relationships, enhance psychosocial adjustment, and reduce the distress underlying cancer and related communication problems, to optimize cancer control and cancer care interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Virginia Lee was supported by a postdoctoral research fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)-Psychosocial Oncology Research Training Program. The authors gratefully acknowledge Janet Childerhose for her helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript and the Neuromedia Services at the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital for formatting the figures.