Οὐ στάσεως οὖν ἀρχηγέτης ὁ Ἰησοῦς ἀλλὰ πάσης εἰρήνης

Jesus is, then, not the leader of any seditious movement, but the promoter of peace. (Origen, Contra Celsum 8.14)

1. Introduction

In his Contra Celsum, Origen responds to Celsus’ various charges against Christian doctrine and practice. These attacks include Celsus’ claim that the Christians, and their leader Jesus, are fomenters of ‘sedition’ or στάσις. Celsus echoes a charge made by Tertullus in Acts 24.5, where Tertullus accuses Paul of being the ringleader (πρωτοστάτης) of the Nazarenes, one who incites στάσεις across the whole inhabited world. What are we to make of these claims? What does it mean for Jesus or Paul to foment στάσις?

Most scholars translate στάσις as ‘sedition’ or ‘insurrection’ by connecting it with the Latin seditio.Footnote 1 While seditio and στάσις overlap in some respects, scholars who connect στάσις with seditio often look to Roman law to pinpoint the exact charge against the Christians. By doing so, they overlook the rich philosophical reflection on στάσις in Greek political thought.Footnote 2 Indeed, it would not be an exaggeration to say that στάσις in a πόλις was the primary political issue addressed by philosophers such as Plato and AristotleFootnote 3 and historians such as Thucydides and Josephus. And yet nearly no study has examined Luke's use of στάσις against this background.Footnote 4

In this article, I examine the trial of Jesus in Luke 23 – the first place where the word appears in Luke-Acts – against the background of Thucydides’ model of στάσις in his famous Corcyra episode (Thuc. 3.82–3). Thucydides serves as a helpful background to Luke, because Thucydides’ reflections on στάσις had a pervasive influence on Greek political philosophy beyond the genre of historiography, both in his own time and into the first century ce. By examining Luke's use of a political topos with a rich intellectual history in Greek political philosophy, we can situate Luke's ‘politics’ in a context more closely aligned with other writers of his day. Like Thucydides and others after him, Luke employs the topos of στάσις as a violent internal conflict and not an act of rebellion or insurrection. He does this to show how the conflict between Jesus and his opponents is symptomatic of a deeper inversion of social bonds and language within a community. Furthermore, this inversion becomes the first instance of a greater conflict that spreads throughout the whole inhabited world in Acts.

2. Στάσις in Greek Political Philosophy

Most studies of στάσις begin by bemoaning the difficulties of translating the word into English. Kostas Kalimtzis writes, ‘The events that stasis was used to describe were very diverse, from the slaughter of political opponents and their families, to political disputes of every variety and shade of expression. Like so many other words that had profound meaning for Hellenic culture, we have no direct counterpart for the range of experiences to which these Greek terms referred.’Footnote 5

This problem is magnified when we consider how words such as ‘insurrection’ and ‘rebellion’ have taken on meanings from our recent history that are quite distant from their ancient counterparts.Footnote 6 In his now classic study on στάσις in the fifth and fourth centuries bce, Hans-Joachim Gehrke says, ‘Diese Definitionsfrage ist deshalb nicht ganz einfach, weil sie genau auf ein gerade in jüngster Zeit viel traktiertes Thema, den Revolutionsbegriff und die Frage seiner Anwendbarkeit auf die Antike, führt.’Footnote 7 I have joined this chorus and have decided, like most studies on the subject, to retain the Greek to avoid confusion. Nevertheless, to move towards an understanding of στάσις, I will summarise what some philosophers had to say on the subject before turning to Thucydides.

Plato offers a common view of στάσις in his day through the mouth of Socrates in Rep. 5.470b: ‘It seems to me that just as we have two terms: πόλεμος and στάσις, so there are two terms which correspond to differences between the two. I mean the words “own” and “family” on the one hand, and “someone else's” and “foreign” on the other. The word στάσις is applied to one's personal enemy, and πόλεμος to an outsider.’Footnote 8 He continues in 470d: ‘Greeks fighting foreigners and foreigners fighting Greeks both treat each other as enemies and are naturally enemies, and this kind of hostility is to be termed war (πόλεμον). But whenever Greeks do this sort of thing to Greeks, although they are naturally friendly, in such a case Greece is sick and in a state of civil conflict (στασιάζειν), and this kind of hostility is to be termed faction (στάσιν).’

Plato contrasts στάσις with war, and says the main difference is that the former takes place between one's ‘own’ (τὸ οἰκεῖον) or one's ‘family’ (τὸ συγγενές), while the latter is a conflict with an external force. Classicist Jonathan Price writes that this understanding of στάσις as an internal conflict in contrast to ‘war’ (πόλεμος) was a common view in Plato's day.Footnote 9 Στάσις was at its core a violent internal conflict, which by the sixth century became closely associated with the health of a πόλις.Footnote 10 Despite admitting the challenge of defining the word, Gehrke says, ‘Die geläufigste Bedeutung im politischen Kontext war doch die, welche wir als “inneren Krieg” mit der o.a. Definition wiedergeben würden.’Footnote 11

Because στάσις is an internal conflict, translations such as ‘uprising’, ‘rebellion’ or ‘revolution’ can be misleading. Indeed, Price argues that it ‘does not have the meaning “insurrection” in any other historian writing in Greek after Thucydides … until Cassius Dio’.Footnote 12 As an internal conflict, στάσις occurs between competing but related factions within a single πόλις or other political body. When Claudius writes to the Jews and Greeks of Alexandria in 41 ce, he writes to address the στάσις that recently occurred in the city.Footnote 13 The στάσις he has in mind was not an uprising or insurrection by the Jews against Rome, but the violent conflict that took place within the city between Jews and Greeks.

Just as significant as the parties involved in στάσις are its effects. Price says, ‘A stasis is characterized by the radical change and reuse, and eventually the breakdown, of social, political, legal and religious conventions, starting with language and family ties, and encompassing all communal decision-making apparatus and all areas designated inviolable by society's norms.’Footnote 14 While one could win glory and honour through πόλεμος, στάσις led invariably to exile or death.Footnote 15 The disastrous effects of στάσις led to its being universally recognised as an evil by the Greeks. The chorus in Aeschylus’ Eumenides prays, ‘May stasis, insatiate of ill, ne'er raise her loud voice within this city.’Footnote 16 Nearer to Luke's time, Dio Chrysostom says, ‘No one would hesitate to reply that these (πόλεμοι καὶ στάσεις καὶ νόσοι) are classed among the evils and that they not only are so but have been considered and are called evils’ (Discourses 38.13). Arguably no one has offered as thorough an account of the effects of this evil as Thucydides, to whom we now turn.

3. The Reception of Thucydides

As mentioned above, my aim in comparing Luke's use of the στάσις topos with Thucydides is to situate his ‘politics’ in a context more closely aligned with other writers of his day. But Thucydides wrote centuries before Luke about unrelated events. How does this comparison then contribute to a more contextually sensitive reading of Luke?

Though Thucydides predates the writing of Luke-Acts by hundreds of years, his influence in the first few centuries ce is undeniable. Around the time when Luke wrote Luke-Acts, Thucydides had already reached the status of a model historian. In his short treatise On Thucydides, written in the first century bce, Dionysius of Halicarnassus describes Thucydides as ‘the greatest of all historians’ (τὸν ἁπάντων κράτιστον τῶν ἱστοριογράφων, ch. 2). Though Dionysius proceeds to critique aspects of Thucydides’ style, he does so with trepidation, aware that ‘I should not only be going against a prevalent opinion established through a long tradition and firmly entrenched in all men's minds, but should also be making light of the personal testimony of the most distinguished philosophers and rhetoricians, who regard that author as a model historian and the standard of excellence in deliberative oratory’ (Thuc. 2). Lucian, in his satirical work How to Write History, says somewhat sarcastically that by his day in the second century ce it had become ‘quite a fashion just now, to suppose that you're following Thucydides’ style if you reproduce, with some small alterations, his own expressions’ (ch. 15).

Beyond these historiographical comments, various extant histories from this period testify to Thucydides’ far-reaching influence. Historians such as Polybius, Tacitus, Sallust and Appian all drew on Thucydides’ account of the Peloponnesian War to frame their own narratives.Footnote 17 Not only Greek and Roman authors, but even Josephus, a Jewish contemporary of Luke, drew heavily on Thucydides both stylistically and thematically. Indeed, Tessa Rajak says, ‘[The Jewish War] is the only complete surviving example of a Thucydidean history of a war from the early imperial period’.Footnote 18

While the genre of Luke-Acts (or Luke and Acts) is debated, few would deny that it contains at least historiographical elements. Furthermore, recent genre theory has complicated the notion that a text such as Luke-Acts must ‘fit’ into a single genre, whose rules the text then obeys. I agree in this regard with Daniel Smith and Zachary Kostopoulos, who understand Luke-Acts ‘as a text that indeed participates in (and whose author emulates) multiple literary traditions of the ancient Mediterranean world’.Footnote 19 My argument therefore does not require that Luke was writing in a particular historiographical tradition, since Thucydides’ influence extended across genres, particularly with regard to στάσις. There are good reasons to believe that Luke was familiar with Thucydides, the model historian of his day,Footnote 20 but my argument does not depend on this knowledge, since Thucydides’ theorising and the reception of his history became part of the political discourse of this time period.Footnote 21 It is worth asking, then, whether Luke draws from or participates in this discourse in any way, since so many of his predecessors and contemporaries did so.Footnote 22 Before doing so, however, we must trace the broad outlines of Thucydides’ reflections on στάσις before considering their reception.

4. Στάσις in Thucydides

Thucydides begins his work by promising to offer an account of ‘the greatest movement (κίνησις) that had ever stirred the Hellenes, extending also to some of the Barbarians, one might say even to a very large part of mankind’ (1.1). It is clear even from the proem that στάσις plays a major role in his account of the war, for Thucydides continues in the next section by describing how different parts of Greece from its earliest days were ‘ruined’ (ἐφθείροντο) by στάσεις or ‘internal quarrels’ (1.2). Towards the end of the proem, he says concerning the Peloponnesian War, ‘Never had so many human beings been exiled, or so much human blood been shed, whether in the course of the war itself or as the result of civil dissensions’ (διὰ τὸ στασιάζειν, 1.23).

In book 3 of his history, Thucydides recounts the στάσις that erupted in Corcyra between two rival factions, the democrats and oligarchs, and offers a model of στάσις through which the reader can interpret later instances of στάσις at Notion (3.34), Rhegion (4.1.3), Megara (4.66), Leontini (5.4.3), Messene (5.5.1) and elsewhere. My comments on Thucydides’ work as a whole and the Corcyra episode in particular are intentionally general, because Thucydides himself aimed to provide a general model applicable to any situation. Thucydides describes the στάσις thus: ‘And so there fell (ἐπέπεσε) upon the cities on account of revolutions (κατὰ στάσιν) many grievous calamities, such as happen and always will happen while human nature is the same, but which are severer or milder, and different in their manifestations, according as the variations in circumstances present themselves in each case’ (3.82.2).Footnote 23

Thucydides’ unique contribution to the study of στάσις was his application of advances in medical science to his analysis of human conflict. Doctors at the time believed that one could predict the course of a disease because of its essential nature, and Thucydides applied this belief to στάσις (commonly compared to a disease) by analysing certain essential features of human nature.Footnote 24 The long history of interpretation of this passage (3.82–3), both ancient and modern, shows that later writers agreed with Thucydides’ claim regarding the inevitability of future στάσεις.Footnote 25 Much can be said about Thucydides’ model, but I wish to highlight three effects of στάσις relevant for our reading of Luke. In στάσις,

(1) Faction takes precedence over family.

(2) Emotions conquer reason.

(3) The customary values of words are changed.

Thucydides’ model highlights the inversion of values, customs and laws that takes place in στάσις. He says concerning the στάσις in Corcyra: ‘Death in every form ensued, and whatever horrors are wont to be perpetrated at such times all happened then – aye, and even worse. For father slew son, men were dragged from the temples and slain near them, and some were even walled up in the temple of Dionysus and perished there’ (3.81.5, emphasis added).

Thucydides goes on to say that ‘the tie of blood (τὸ ξυγγενές) was weaker than the tie of party’ (3.82.6). Charles Forster Smith's translation softens the shocking language of this passage, for Thucydides says these blood ties ‘became more foreign’ (ἀλλοτριώτερον ἐγένετο) and not just weaker. Price says, ‘Thucydides’ choice of expression indicates that familiar ties became foreign in stasis, and loyalty to the faction created in stasis (as opposed to that created in a healthy polis) can turn family members into the “other”, “(more) foreign”, the enemy.’Footnote 26

Not only does loyalty to one's faction turn family members into foreigners, but just political processes break down as unbridled passions overtake rational deliberation. Thucydides stresses throughout this section that people are blinded by greed, power and personal safety above the well-being of the community. He says, ‘The cause of all these evils was the desire to rule which greed and ambition inspire, and also, springing from them, that ardour which belongs to men who once have become engaged in factious rivalry’ (3.82.8). He continues later, ‘It was in Corcyra, then, that most of these atrocities were first committed … assaults of pitiless cruelty, such as men make, not with a view to gain, but when, being on terms of complete equality with their foe, they are utterly carried away by uncontrollable passion’ (3.84.1–2).Footnote 27 Thucydides calls these στάσεις ‘outbreaks of passion’ (ὀργαῖς, 3.85.1), because, as Kalimtzis says, ‘Thucydides was careful not to reduce stasis to conscious calculation, because all the evidence pointed to an irrational self-destructive process’.Footnote 28

Perhaps the most famous of Thucydides’ statements on στάσις is the effect στάσις has on language. He says, ‘The ordinary acceptation (ἀξίωσιν) of words (ὀνομάτων) in their relation to things (ἔργα) was changed as men thought fit. Reckless audacity came to be regarded as courageous loyalty to party, prudent hesitation as specious cowardice, moderation as a cloak for unmanly weakness, and to be clever in everything was to do naught in anything’ (3.82.4). Smith's translation, while somewhat cumbersome, captures accurately what others obscure – the meanings of words do not change in στάσις, but only their ‘acceptation’ or ‘valuation’ (ἀξίωσιν) in relation to ‘things’ (ἔργα). Price says, ‘Thucydides means that during stasis words retain their agreed-upon meaning but the value assigned to them, that is, how their meanings were enacted in society, changes.’Footnote 29 ‘Reckless audacity’ continues to mean ‘reckless audacity’, but it is valued by some as ‘courageous loyalty’, while acts done in ‘moderation’ (σῶφρον) were viewed by opponents as ‘unmanly weakness’. He is expanding on a common binary between λόγος and ἔργον, word and deed/fact, and says that the claims made by factions did not match the deeds or facts. Thucydides describes a state of linguistic chaos in which factions define the same words opportunistically, so that ‘justice’ for one side may be the greatest evil for another.

5. Στάσις in Josephus’ Jewish War

How did later readers receive, reflect on and reinterpret Thucydides’ analysis for their own purposes? While it is not clear to what extent Luke drew specifically from Thucydides (rather than from the broader discourse), scholars generally agree that Josephus modelled his Jewish War on Thucydides’ history. Josephus’ indebtedness to Thucydides is nowhere as clear as in his use of στάσις as a leitmotif throughout his work.Footnote 30 Louis Feldman says that Josephus does this to appeal ‘to his politically-minded audience so familiar with Thucydides’ description (3.82–84) of the disastrous effects of the revolution at Corcyra’.Footnote 31

Josephus begins his Jewish War in a conspicuously Thucydidean fashion by describing the war as ‘the greatest not only of the wars of our own time, but, so far as accounts have reached us, well nigh of all that ever broke out between cities or nations’ (1.1).Footnote 32 He says that this war was an ‘upheaval (κινήματος) … of the greatest magnitude’ (1.4), echoing Thucydides’ description of the war as ‘the greatest movement (κίνησις) that had ever stirred the Hellenes’ (Thucydides 1.1). Thematically, Josephus draws on Thucydides by attributing the cause of the war ultimately to στάσις: ‘For, that [the Jewish nation] owed its ruin to civil strife (στάσις οἰκεία), and that it was the Jewish tyrants who drew down upon the holy temple the unwilling hands of the Romans and the conflagration, is attested by Titus Caesar himself, who sacked the city’ (B.J. 1.4). Steve Mason says that στάσις is a ‘key theme’ in the Jewish War, and that ‘the mere use of such hot-button words conjured up entire worlds of association – all of it bad’.Footnote 33 Immediately after the proem, Josephus begins the narrative proper with στάσις as the first word, a point obscured in most English translations.Footnote 34 Price goes so far as to say that ‘Thucydides wrote so powerfully [about στάσις] that the mere mention of the word [in Josephus] invoked Thucydides’ incisive analysis of internal conflict in Book iii of his History’.Footnote 35

Allusions to the Corcyrean episode specifically appear in book 4 of Josephus’ Jewish War where he describes the στάσις of Jerusalem. Josephus writes, ‘Faction (στάσις) reigned everywhere’ (4.133) and ‘in cruelty and lawlessness the victims saw no difference between the Romans and their own countrymen; in fact those who were plundered thought it a far lighter fate to be captured by the Romans’ (4.134). This is probably an allusion to Thucydides’ description of the breakdown of family relations in στάσις. Furthermore, Josephus also describes how language became distorted and rival factions presented false charges to suit the occasion: ‘Those with whom any had ancient quarrels having been put to death, against those who had given them no umbrage in peace-time accusations suitable to the occasion were invented: the man who never approached them was suspected of pride; he who approached them with freedom, of treating them with contempt; he who courted them, of conspiracy’ (4.354–65).

This section of book 4 summarises what Josephus recounts earlier regarding the rebels’ use of political slogans. Στάσις has created a discrepancy between λόγος and ἔργον, or as Thucydides says, the ‘valuation of words in their relation to things’ (3.82.4) has changed. To give just one example, in B.J. 4.146 Josephus recounts how the Zealots plotted to kill Antipas, Levias, Syphas and others held captive by commissioning John, an assassin. Josephus says, ‘For such a monstrous crime they invented as monstrous an excuse, declaring that their victims [the nobles] had conferred with the Romans concerning the surrender of Jerusalem and had been slain as traitors to the liberty of the state. In short, they boasted of their audacious acts as though they had been the benefactors and saviours of the city.’ The Zealots call themselves ‘benefactors’ and ‘saviours’, though these words do not align with their deeds. Josephus says that they invented an excuse and labelled their victims traitors. The language distortion here is typical of στάσις and points to a broader mundus inversus topos in Thucydides and ancient accounts of civic strife more broadly. Gottfried Mader says, ‘Corcyrean stasis and Athenian plague provide Josephus not only with specific thematic parallels but, more fundamentally, with a broad conceptual frame that he applies to his own analysis of the strife in Jerusalem. Plague and stasis, in the political pathology of Thucydides, are complementary paradigms of civic and social dissolution, analysed as a twofold μεταβολή: an external disaster or convulsion precipitates a correlative inward dislocation, expressed typically in the phenomenon of moral anarchy or “Umwertung der Werte”.’Footnote 36

Like Josephus and Thucydides, Luke too tells the story of an ‘Umwertung der Werte’ or mundus inversus. Especially in Acts, as the gospel spreads throughout the οἰκουμένη, στάσις erupts and the followers of the Way are accused of ‘turning the world upside down’ (Acts 17.6).Footnote 37 In the rest of this article, I will argue that this conflict begins in Jerusalem with the trial of Jesus, when στάσις erupts within the Jewish community.

6. Luke 23 as Thucydidean στάσις

Στάσις is an important theme in Luke-Acts, but one that remains understudied. The word is used seven times in Luke-Acts and only twice elsewhere in the New Testament.Footnote 38 It is especially clear from Acts 24.5 that Luke uses the term in its Greek political sense to mean ‘civil strife’ or ‘internal war’. In Acts 24, the Jewish opponents of Paul present charges against him before Felix. Tertullus says,

εὑρόντες γὰρ τὸν ἄνδρα τοῦτον λοιμὸν καὶ κινοῦντα στάσεις πᾶσιν τοῖς Ἰουδαίοις τοῖς κατὰ τὴν οἰκουμένην πρωτοστάτην τε τῆς τῶν Ναζωραίων αἱρέσεως

We have found this man to be a plague and one who incites civil strife among all the Jews throughout the inhabited world as leader of the sect of the Nazarenes.Footnote 39

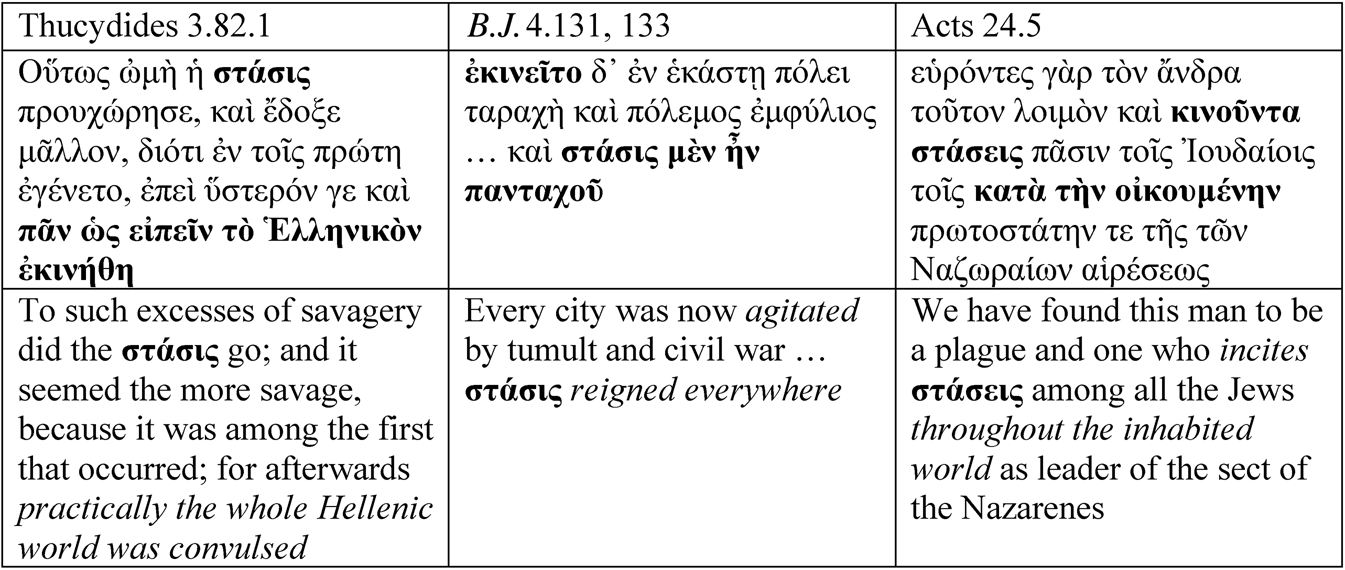

In Thucydides, στάσις is described as a plague that infects a πόλις, and this metaphor predates Thucydides and is common in Greek political philosophy.Footnote 40 By employing this metaphor, Luke places this charge of στάσις within the realm of Greek political thought. A comparison between this charge against Paul and some passages from Josephus and Thucydides reveals further parallels (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Στάσις in Thucydides, Josephus and Acts

Luke employs a wordplay by using the verb κινεῖν (‘to move’) with στάσις, which has the root meaning of ‘standing’ or ‘immobility’.Footnote 41 Most philosophers connected στάσις with immobility or stability, but Thucydides uniquely described the spread of στάσις as a ‘movement’ or κίνησις (1.1), which Josephus also adopts (κίνημα, B.J. 1.4). Like Thucydides and Josephus, Luke has Tertullus accuse Paul of ‘moving’ or inciting στάσεις throughout the whole world. In Thucydides’ narrative, the στάσις in Corcyra is only the beginning of a movement that disturbs the whole Hellenic world, and in Josephus, στάσις spreads throughout Jewish communities in the diaspora.Footnote 42 In the book of Acts, στάσις seems to follow the disciples to Antioch (15.2), Ephesus (19.40) and Jerusalem (23.7). But where does this worldwide conflict begin for Luke? I believe it begins in Luke 23, where he portrays the trial of Jesus as the first στάσις.

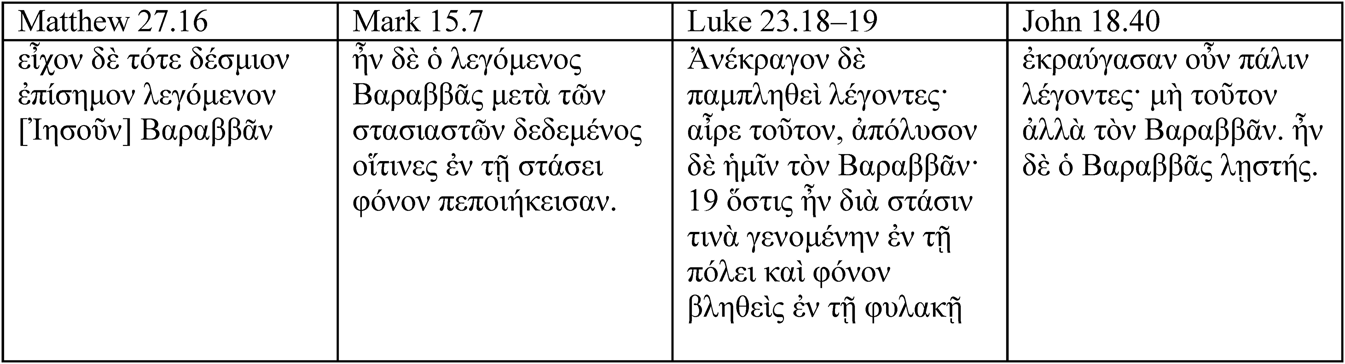

The word στάσις is first used in Luke-Acts in Luke 23.19, where Luke describes Barabbas as someone thrown into prison ‘on account of a στάσις and murder that occurred in the city’. That Luke has in mind the Greek political understanding of στάσις in Luke 23 is clear when we compare Luke's account with the other Gospels (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Barabbas in the Four Gospels

Luke makes some conspicuous edits to Mark that place the charge of στάσις firmly in the realm of Greek political thought. First, Luke says this στάσις took place ‘ἐν τῇ πόλει’. This addition highlights the common understanding that στάσις was always linked with the πόλις. Price says, ‘The self-evident link between stasis and the polis is assumed by every other Ancient Greek author [besides Thucydides] who wrote theoretically about stasis, and even by many of Thucydides’ imitators among the later historians … It is uncertain whether any Ancient Greek writer other than Thucydides imagined stasis in any setting other than the polis.’Footnote 43

Luke also highlights the twin charges of στάσις and φόνος as the reason why Barabbas was imprisoned. In Mark 15.7, Barabbas is imprisoned because he committed murder during the στάσις (ἐν τῇ στάσει), whereas Luke says that he was imprisoned because of both στάσις and φόνος (διὰ στάσιν … καὶ φόνον, Luke 23.19; cf. 23.25). The difference is subtle but important, for it highlights how Luke wishes to portray Barabbas as guilty of both στάσις and murder, whereas Mark's account primarily focuses on the murder charge. Στάσις and φόνος are commonly linked throughout Thucydides’ work.Footnote 44 Loraux argues that classical authors avoided connecting στάσις with any sense of ‘beautiful death’, and instead connected it with φόνος.Footnote 45 In Thucydides’ work, the death of Pericles becomes a model of ἀρετή in book 2, whereas φόνος language dominates when we turn to the στάσις at Corcyra in book 3.Footnote 46

When we turn to examining the actual trial, though Luke does not directly state that the trial is a στάσις, we find that the effects of στάσις described by Thucydides appear here as well. Luke 23 is unique among the trial scenes in the Gospels, for here the Jewish leaders bring specific charges against Jesus. Verse 2 says,

τοῦτον εὕραμεν διαστρέφοντα τὸ ἔθνος ἡμῶν καὶ κωλύοντα φόρους Καίσαρι διδόναι καὶ λέγοντα ἑαυτὸν χριστὸν βασιλέα εἶναι.

We have found this one leading astray our people and preventing [us] from giving taxes to Caesar and calling himself Christ, a king.

It is likely that the main charge in view is that Jesus leads astray or perverts the Jewish people.Footnote 47 The second and third participial phrases (κωλύοντα and λέγοντα) specify this more general charge.Footnote 48 This charge is repeated in verses 5 and 14 (by Pilate):

Verse 2: τοῦτον εὕραμεν διαστρέφοντα τὸ ἔθνος ἡμῶν

Verse 5: οἱ δὲ ἐπίσχυον λέγοντες ὅτι ἀνασείει τὸν λαὸν

Verse 14: προσηνέγκατέ μοι τὸν ἄνθρωπον τοῦτον ὡς ἀποστρέφοντα τὸν λαόν

It is significant that the main charge alleges that Jesus leads astray or perverts ‘our people’ (τὸ ἔθνος ἡμῶν), a reference to the Jewish nation. Thucydides describes how ‘the tie of blood (τὸ ξυγγενές) became more foreign (ἀλλοτριώτερον ἐγένετο) than the tie of party’ (3.82.6) in στάσις, and Josephus says that the Jerusalem στάσις led its victims to see ‘no difference between the Romans and their own countrymen’ (B.J. 4.134). A similar breakdown in family relations occurs in Luke, where Jesus’ opponents accuse him of stirring up ‘the people’ (τὸν λαόν, 23.5) by teaching from Galilee to Jerusalem (ἀπὸ τῆς Γαλιλαίας ἕως ὧδε). This reference to Galilee looks back to Luke 4.16–30, where Jesus preaches in a synagogue in Nazareth, his πατρίς. There, too, his family and relatives reject his message and attempt to kill him. This dissolution of family bonds culminates here in Jerusalem where the Jewish leaders demand the death of Jesus, ‘king of the Jews’ (23.3).

Furthermore, Luke characterises Jesus’ opponents as those who rely on emotion over reason to get their way, another symptom of στάσις. Despite Pilate's repeated declaration that Jesus is ‘innocent’ (23.4, 14, 15), the Jewish leaders and crowds intensify their accusations, but not with any new charges. Instead, their voices crescendo until they finally overpower Pilate (κατίσχυον αἱ φωναὶ αὐτῶν, 23.23). Luke's careful choice of words highlights their reliance on emotion over reason:

Verse 5: οἱ δὲ ἐπίσχυον λέγοντες …

Verse 10: εὐτόνως κατηγοροῦντες αὐτοῦ …

Verse 18: Ἀνέκραγον δὲ παμπληθεὶ …

Verse 21: οἱ δὲ ἐπεφώνουν λέγοντες …

Verse 23: οἱ δὲ ἐπέκειντο φωναῖς μεγάλαις / κατίσχυον αἱ φωναὶ αὐτῶν

François Bovon notes that Luke intentionally uses ‘voice’ (φωνή) twice in verse 23 to emphasise that this conflict is ‘a battle of words’.Footnote 49 C. F. Evans says, ‘The language here is strongly expressive of the power of mob clamour to pervert justice.’Footnote 50 As we saw above, a reliance on passion over reason is a symptom of στάσις, whereby a group's ability to reason matters less than their ability to overpower their opponents. When Pilate acquiesces to the mob's demand to crucify Jesus, he agrees to do so not because he is convinced of the justice of such a penalty, but, as Joel Green says, ‘in order to assuage a riotous mob, to preserve peace rather than to promote justice’.Footnote 51

Finally, the false charges brought against Jesus point to the kind of language distortion that is symptomatic of στάσις. The Jewish leaders specify their main charge against Jesus by saying that he prevents them from paying taxes to Caesar and calls himself Christ, a king (23.2). If one has followed the narrative up to this point, it is clear that the first charge is blatantly false. In Luke 20.25, Jesus responds to a question concerning whether taxes should be given to the emperor and says, ‘Give to Caesar the things that are Caesar's, and to God the things that are God's.’ Regarding the second charge, that Jesus calls himself a king, while the crowds admittedly call Jesus ‘king’ (βασιλεύς, 19.38) when he enters Jerusalem, his kingdom is nevertheless not a political rival to Rome. Certainly, Jesus’ role as a Davidic king is foreshadowed from the very beginning of Luke's Gospel (1.31), but it is made equally clear, as Bovon says, that ‘his kingship, which comes from the resurrection beyond the cross, is of a different order than the political’.Footnote 52 This is not to deny that Jesus is the βασιλεύς of the βασιλεία τοῦ θεοῦ, a fact which Acts makes abundantly clear (Acts 1.3; 28.30–1). Rather, the charge is false from Luke's perspective insofar as Jesus is not a king who seeks the throne of Caesar. This is not to say that Jesus is merely a ‘spiritual’ king or that his kingdom is merely in ‘heaven’, as later Christians would argue. Rather, as Kavin Rowe has argued, there is a ‘tension’ evident in the charge that Jesus is a king that makes the claim both true and false. The claim is false when ‘they attempt to place Jesus in competitive relation to Caesar’.Footnote 53 The claim is true in that Jesus has a kingdom, though not one that would rival Rome in the same political sphere.

The main charge, that Jesus is perverting the people, appears to be not only false, but also ironic when we consider the actions of those bringing this charge. In Luke 23.5, the Jewish leaders and crowds say that Jesus ‘stirs up’ (ἀνασείει, 23.5) the people, and the verb ἀνασείω implies ‘shock, agitation, insurrection’.Footnote 54 This charge against Jesus parallels the charge brought against Paul in Acts 24.5; in effect, they accuse Jesus of inciting στάσεις ‘throughout all Judea’ (καθ᾿ ὅλης τῆς Ἰουδαίας), just as Paul is accused of inciting στάσεις ‘throughout the inhabited world’ (κατὰ τὴν οἰκουμένην, Acts 24.5).Footnote 55 As the trial scene progresses, it becomes increasingly clear that it is in fact the Jewish leaders and crowds who incite στάσις, and not Jesus.Footnote 56

As we saw above, the rising voices of the Jewish leaders and crowds become the clamour of a riotous mob inciting the people to crucify Jesus. By presenting Jesus’ opponents as a mob, Luke not only adds to the irony of their accusations, but also points to the deeper inversion taking place because of στάσις. In Thucydides and Josephus, στάσις results in a disruption between language and reality when opposing parties change the valuation of words (λόγοι) in relation to things (ἔργα). Thucydides presents the speeches of both parties so the reader can witness this taking place and Josephus offers his own commentary to highlight this inversion. As a follower of Jesus and member of the Way (Luke 1.1–2), Luke gives us the reality (ἔργον) with which to compare the Jewish leaders’ speech (λόγος) primarily through the narrative itself, and sometimes through his narratorial comments. We have already seen how the narrative falsifies their charges, but Luke gives a further clue in his parenthetical statement on Barabbas in verses 19 and 25, the first places where στάσις is used in Luke-Acts.

Luke is the only gospel writer to mention Barabbas’ crime twice. In Luke 23.25, he says,

ἀπέλυσεν δὲ [Πιλᾶτος]

-

τὸν διὰ στάσιν καὶ φόνον βεβλημένον εἰς φυλακὴν ὃν ᾐτοῦντο,

-

τὸν δὲ Ἰησοῦν παρέδωκεν τῷ θελήματι αὐτῶν

And [Pilate] released

-

the one thrown into prison on account of στάσις and murder, whom they requested

-

but he handed Jesus over to their will. (my translation)

By repeating Barabbas’ crime and juxtaposing it here with Pilate's handing Jesus over to their will, Luke concludes the trial scene the way it began. In Luke 23.2, the Jewish leaders accuse Jesus of στάσις, and here in verse 25 the ones who actually incite στάσις demand the release of the one imprisoned for στάσις and murder, so they can murder the one they accuse of στάσις. The point here is not only irony, but disruption. By accusing Jesus of στάσις and ultimately prevailing through inciting the crowds, the Jewish leaders and crowds have changed the valuation of the word στάσις. In Luke's view, Barabbas and the Jewish leaders are the ones guilty of στάσις, and their false charge of στάσις is meant to highlight the anarchy that erupts when faction takes precedence over family, emotions conquer reason, and the customary values of words are changed – that is to say, when στάσις erupts in a city.

7. Conclusion

Thucydides has influenced historians and philosophers from Tacitus to Thomas Hobbes, from Josephus to Friedrich Nietzsche. But has he influenced Luke? I believe he has, whether directly through Luke's acquaintance with Thucydides or indirectly through Thucydides’ general influence on discussions of στάσις in the Greek-speaking world. Regardless of the extent to which Luke was acquainted with Thucydides, there is much to be gained from exploring the concept of στάσις in Luke-Acts in light of the rich philosophical reflection on στάσις in Greek political thought.

Greek philosophers and historians reflected at great length on the occurrence of conflict in a πόλις and how best to avoid it. As a political thinker in his own right, Luke narrates the spread of this conflict from Jerusalem through the cities of the Roman Empire. In Acts, the gospel message is met with hostility as the opponents of the Way accuse the disciples of ‘agitating our city’ (ἐκταράσσουσιν ἡμῶν τὴν πόλιν, 16.20) and ‘turning the world upside down’ (τὴν οἰκουμένην ἀναστατώσαντες, 17.6). In Acts 19.23–40, a στάσις erupts in Ephesus when Paul's preaching threatens the business of local artisans. The silversmiths incite the crowds by saying that Paul threatens ‘almost all of Asia’ (σχεδὸν πάσης τῆς Ἀσίας, 19.26; cf. Luke 23.5 καθ᾿ ὅλης τῆς Ἰουδαίας), and they become filled with ‘rage’ (γενόμενοι πλήρεις θυμοῦ, Acts 19.28). Emotion conquers reason as the city is ‘filled with confusion’ (ἐπλήσθη ἡ πόλις τῆς συγχύσεως, 19.29) and they do not even know why they have gathered (οὐκ ᾔδεισαν τίνος ἕνεκα συνεληλύθεισαν, 19.32). They shout ‘for about two hours’ (ὡς ἐπὶ ὥρας δύο κραζόντων, 19.34) and admit that they are in danger of being charged with στάσις (κινδυνεύομεν ἐγκαλεῖσθαι στάσεως, 19.40). The στάσις of Ephesus looks very much like the στάσις of Jerusalem in Luke 23. Like Thucydides, who saw the Corcyrean στάσις as the first stage in a great upheaval that shook the entire Hellenic world, Luke sees the στάσις of Jesus’ trial as a model for the στάσεις that erupt throughout the Roman Empire in Acts.

What might this tell us about Luke's politics? The story of Acts is not only (or primarily) a story of conflict, but also a story of harmony; even as στάσεις erupt throughout the Empire, new communities are formed whose members are of one accord (ὁμοθυμαδόν, 2.46) and have everything in common (ἅπαντα κοινά, 2.44).Footnote 57 In his Precepts of Statecraft, Plutarch says, ‘But the best thing is to see to it in advance that factional discord shall never arise (μηδέποτε στασιάζωσι) among [competing factions in a city] and to regard this as the greatest and noblest function of what may be called the art of statesmanship’ (824c). He goes on to say, ‘There remains, then, for the statesman, of those activities which fall within his province, only this – and it is the equal of any of the other blessings: – always to instil concord (ὁμόνοιαν) and friendship (φιλίαν) in those who dwell together with him and to remove strifes, discords, and all enmity’ (824d). Plutarch is echoing what philosophers before him held to be true of στάσις: if στάσις is a disease, its cure is harmony or friendship.

Like Plutarch, Luke is primarily concerned with the nature of a healthy community, and his narrative depicts the construction of new communities of friendship and harmony even as the πόλεις of the Empire are torn asunder. As Plutarch says, preventing στάσις is ‘the greatest and noblest function’ of the statesman. It is surprising, then, that such an important concept has received so little attention in studies of Luke's politics. To ask instead whether one community (the church) is ‘guilty’ or ‘innocent’ before an external governing body (Rome) is to ask a question quite distant from the main concerns of most first-century political thinkers, whether Plutarch or Josephus or, I would argue, Luke himself. By considering the nature of these communities and the conflicts that erupt within them in Luke-Acts, we can gain a more full-orbed and contextually appropriate picture of Luke's politics.