Introduction

In 1958, Guido Calderoli, grandfather of Lega Nord senator Roberto Calderoli, wrote the following message for his own autonomist movement, the Movimento Autonomista Bergamasco (MAB): ‘With our autonomist electoral list we can shout, Lombardy for the Lombards!’ (Calderoli Reference Calderoli1958, 178–180). The most obvious comparison for any scholar of North Italian regionalism is to put this message alongside that of the Lega Autonomista Lombarda (now the Lega Nord) in the early 1980s, which barely 30 years later was formed on the principle of obtaining the ‘integral political, administrative and cultural autonomy of Lombardy’ (Bossi Reference Bossi1983). Reading these two extracts together, one assumes that between the post-war autonomist current in Bergamo and the leghismo which emerged in the 1980s, there was more than just the inter-generational link of the Calderolis. There were indeed, many similarities which went beyond a shared desire for greater regional autonomy, including cross-overs in anti-southern, anti-bureaucratic, anti-centralist and anti-Roman discourse. But many elements and issues raised by the Bergamascans regarding the importance of Italian unity would have been anathema to Lega ideology, let alone the fact that leghismo emerged after the 1970s regional reforms, and therefore stood for a different type of regional autonomy from that for which the Bergamascan autonomists had campaigned.

This article examines whether and to what extent there are continuities and discontinuities between the MAB and the Lega Nord. The fact that there have been two waves of regionalist activism in Bergamo is far from casual, and the salience of the issue of regional autonomy in this province can be attributed to several factors. As well as the influence of a particular Bergamascan Catholic subculture, Bergamo is also one of the most productive, rich and dynamic areas of Italy (Boulliaud and Dematteo Reference Boulliaud and Dematteo2004, 39; Dematteo Reference Dematteo2011, 17). Bergamascans, therefore, tend to define themselves – often in oppositional terms with the rest of Italy – as people who work and produce. This, in combination with Bergamo’s geographic location as a mountain city have helped create a subculture of ‘localism’ through which Bergamascans ‘feel that their town is self-sufficient’ (Dematteo Reference Dematteo2011, 18). All of these factors played a central role to the political message of both the MAB and the Lega and will be examined in greater detail throughout the article.

By analysing and comparing numerous variables present in both waves of regionalist activism, what emerges is a nuanced analysis of the MAB’s role as a precursor to leghismo. In doing so, the article not only contributes to the extensive existing literature on the Lega, but also seeks to widen the field by bringing to the fore a movement that has largely been overlooked in the history of North Italian regional autonomy. My research naturally draws on this literature on the Lega (Bull and Gilbert Reference Bull and Gilbert2001; Diamanti Reference Diamanti1993 and Reference Diamanti1996; Levy Reference Levy1996). Such works have not only provided important historical contextualisation of the movement but have also contributed greatly to our understanding of a constantly changing and evolving political organisation. However, less attention has been paid to earlier movements for regional autonomy such as the MAB of the 1950s. A number of studies on the Lega mention their existence, but generally they do not provide a comparative analysis with contemporary leghismo (Gold Reference Gold2003; Cachafeiro Reference Cachafeiro2002; Toso Reference Toso1996).

More frequently, the existence of historic movements has in the past been seized upon by Lega Nord ideologues such as Gilberto Oneto and Beppe Burzio who, in writing for Quaderni Padani (Padanian Notebooks, a Lega-affiliated journal), have referred to the movements by way of historical legitimisation for the Lega Nord. (Burzio Reference Burzio2000; Oneto Reference Oneto2013) This represents one of the key pitfalls for the historian who, in trying to provide a balanced analysis, is sometimes dealing with the same materials used by those who have clearly partisan political motives.

Perhaps the most important academic contribution to date towards the examination of the links between the Lega Nord and the MAB was the claim by Boulliaud and Dematteo (Reference Boulliaud and Dematteo2004, 33) that Umberto Bossi’s Lega Lombarda, which emerged in the 1980s and 1990s, was nothing more than the latest manifestation of an autonomist current rooted in the Catholic subculture in Bergamo. The authors argued that the autonomist stance in the post-war period found representation through the strong Catholic subculture in Lombardy and the Veneto, which manifested itself through loyalty to the DC. Once these ties began to break in the 1980s, the autonomist current which had existed in the decades following the end of the Second World War could finally find a voice in leghismo. In a subsequent publication, Lynda Dematteo (Reference Dematteo2011) built upon this thesis with part of her book arguing strongly for strong elements of continuity between mabismo and leghismo.

It is my contention, however, that Boulliaud and Dematteo, by insisting that leghismo was ‘an old political programme, new only in appearance’ focus too much on aspects of continuity, neglecting the broader ideas of the post-war Bergamascan autonomists that run counter to their thesis (Boulliaud and Dematteo Reference Boulliaud and Dematteo2004, 33). While the present article builds upon many of the ideas presented in the aforementioned authors’ study, it takes a different approach by focusing on four key variables common to both waves of activism. First, anti-fascism; second, the extent to which the movements provided an alternative to the DC; third, the federalist, republican and (north) European identity of each movement; and finally, the extent to which each wave of activism focused on the notion of The Invasion of the North by the Other. These variables will allow for a more balanced analysis of the continuities and discontinuities between the MAB and the Lega.

In terms of methodology, this article examines a variety of propaganda, ideas and writings of the Bergamascan autonomists which shows not only similarities but also significant differences when compared to leghismo. The analysis will focus principally on the period between 1948 and 1970. The year 1948 saw the approval of the Italy’s new constitution but, crucially, not the full activation of the 20 regions sanctioned by the constitution. It was only with the regional reform in 1968 that electoral laws were adopted to allow a vote for regional councils; the first of these elections were held in 1970. Further analysis in the final section will also focus on the early 1980s, when these reforms were not followed by a dissolution of regionalist movements, but instead saw autonomist ideas continue to circulate in Lombardy.

The vast majority of sources consulted were produced by activists in the Bergamascan autonomist movement: the analysis is based on primary sources consisting mainly of writings, Lega Nord publications, and interviews.Footnote 1 The interviews were with Piedmontese autonomist and self-declared ‘counter-historian’, Roberto Gremmo, who shed light on the later years of the Bergamascan autonomists, and also with Giuseppe Sala, the son-in-law of Gianfranco Gonella, who became communal councillor for the MAB in 1956. Sala provided an insight into the raison d’être of the MAB and as a life-long resident of Bergamo, he gave his opinion on certain similarities and differences between the MAB and leghismo.

The article is divided into six sections. The first traces the development of the Bergamascan autonomist movement from 1948 until 1970. The following sections carry out a thematic based analysis of the MAB’s political discourse, examining the aforementioned overlapping variables. The final section draws conclusions by comparing the MAB’s programme with that of the Lega, analysing elements of continuity and discontinuity in the political discourse of the two waves of regionalist activism.

Bergamascan autonomy after 1948

Before looking at some specific themes which emerged in the discourse of the Bergamascan autonomists, it is worth tracing a brief history of the origins of the MAB, its membership, and its electoral history from the immediate post-war period until the first regional elections in 1970. As early as June 1947, six months before the republican constitution came into effect, a meeting was organised by lawyer and member of the Republican Party Giulio Bergmann, and was attended by a number of middle-class Bergmascan professionals including teachers, dentists, doctors, accountants, and lawyers (Gruppo Autonomisti Bergamaschi 1955, 59). A few months later, 11 members formed a group based in Bergamo named the ‘Movimento per le Autonomie Locali’ (MAL). The MAL, ‘independent of any political party’, intended ‘to dedicate itself to the democratic principles of Local Autonomy’ (Gruppo Autonomisti Bergamaschi, 1955, 59; Freddi Reference Freddi1963, 5).

As the constitution was being written, the Bergamascan Autonomists were putting their views forward to the Constituent Assembly, advocating the creation of regional government (Freddi Reference Freddi1963, 6). Following 1948, when the approval of the regional statutes on paper did not translate into reality for regions which fell outside the criteria for the special statutes awarded to Sicily, Sardinia, Val D’Aosta and Trentino-Alto Adige, Anselmo Freddi, one of the MAL’s original members, stated that ‘the regional statutes we had desired had now been written into the constitution. It became our duty to ensure they were activated’ (Freddi Reference Freddi1963, 6). Following a period of writing essays, pamphlets and articles on regional autonomy, the Bergamascan autonomists took part in campaigns in regions outside Lombardy. Campaigning in piazzas in Trieste and then Friuli gave many of the Bergamascan activists their first taste of the art of oratory instead of simply putting pen to paper, and the process inspired a desire to stand in elections (Freddi Reference Freddi1963, 14).

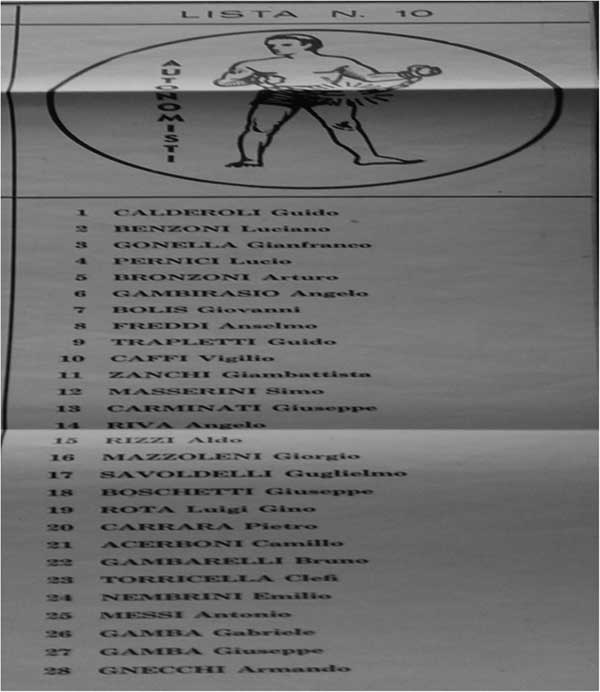

In 1956, these activists renamed themselves as the Movimento Autonomista Bergamasco (MAB), and presented a list of candidates in the administrative elections to the communal and provincial councils. Their symbol was a slave breaking free from the bureaucratic chains of Rome (Fig. 1). The MAB received 1,248 votes (1.98%) of the 63,173 votes in the communal elections.Footnote 2 With the highest number of preference votes, Guido Calderoli was elected as communal councillor. The MAB’s list for the provincial council also received 1,381 votes (2.23%) of the 61,926 votes cast and saw Calderoli’s autonomist colleague Ugo Gavazzeni elected as a provinicial councillor. Although Calderoli stepped down from his post as communal councillor to be replaced by fellow MAB member, Gianfranco Gonella, he continued to play an active role in the movement. In particular, Calderoli put his efforts into establishing, at least on paper, the Movimento per l’Autonomia Regionale Lombarda (MARL 1958). This project, however, was to be superseded by a more ambitious vision of associating the autonomist movement with all the provinces of Piedmont and almost all those of Lombardy and the Veneto, Trentino and Friuli (Freddi Reference Freddi1963, 19).

Figure 1 The MAB’s first electoral list for the 1956 administrative elections. With thanks to Archivio Comunale di Bergamo.

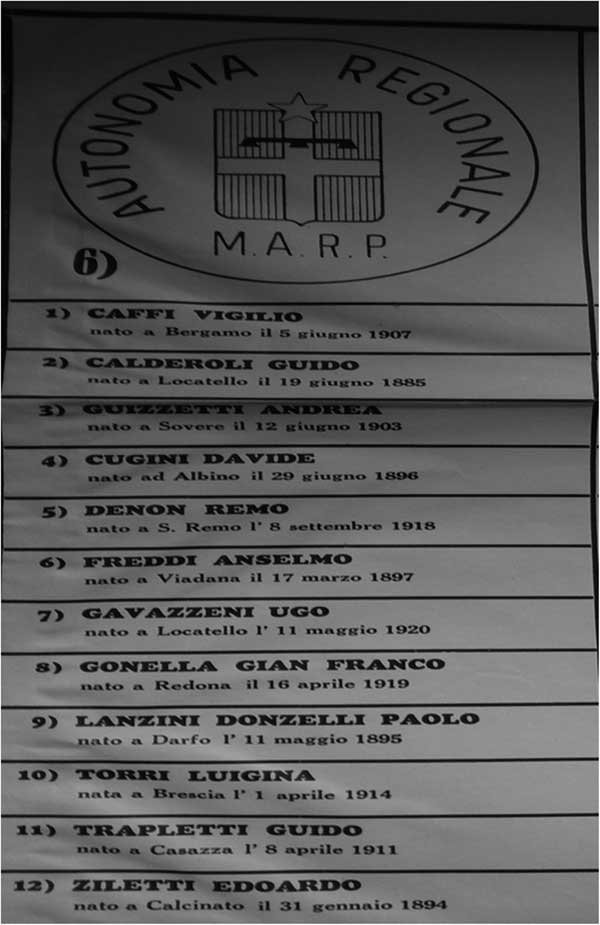

On 23 Feburary 1958, various autonomist movements from the North came together to fight elections under a single list known as the Movimento Autonomie Regionali Padane (MARPadania), an acronym which had previously belonged to the largest of these regionalist movements, the Movimento per l’Autonomia Regionale Piemontese (MARP) (Fig. 2). The announcement of this electoral pact failed to send shock-waves through the nation, or indeed to attract much media attention beyond Turin’s La Stampa. The coalition did not return a single candidate in the election (La Stampa 1958). The MARPadania Bergamascan delegation list received a reduced vote share in the Bergamo-Brescia electoral college with 772 votes (1.11%) of the 69,303 cast for the Chamber of Deputies and 764 votes (1.23%) out of 62,145 for the Senate. This significant drop in the vote for the Bergamascan autonomists led to a meeting in 1960 at which ‘with seven votes against one it was decided to put on the table cordial talks with the DC of Bergamo’; at the root of these talks was an agreement that ‘in exchange for renouncing the autonomist struggle, the MAB’s key exponents would be welcomed into the DC list’ (Freddi Reference Freddi1963, 20).

Figure 2 The 1958 symbol and electoral list for the Bergamascan delegation of The MARPadane (MARPadania) alliance. With thanks to Archivio Comunale di Bergamo.

‘A good four of the seven’ autonomists, after abandoning the title of Mabisti, did not opt to join the DC’s list but instead assumed ‘the new name of Autonomisti’ and changed their symbol to a ‘campanile’.Footnote 3 This rump movement only had sufficient numbers to present a list at the provincial council; however, receiving only 530 (0.81%) of the 65,040 votes cast, the autonomists failed to re-elect any member to the council. Certain members of this rump movement would continue to remain active in politics in the 1960s and in 1968 would form the Unione Autonomisti d’Italia (UAI) under the leadership of former MAB provincial councillor and friend of Guido Calderoli, Ugo Gavazzeni (Freddi Reference Freddi1963, 20).

The message of the UAI was very similar to that of its predecessors, with its leader being keen to ‘underline the logical continuity between the MAB, the MARP and the UAI’ (Gavazzeni Reference Gavazzeni1968). However, during their doomed election campaign of 1968, the candidates of the UAI, in the words of Boulliaud and Dematteo, ‘managed to speak, but without making themselves heard’ (2004, 44). As Roberto Gremmo accurately notes, despite the presence of the MARPadania and later the UAI throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, it was not until 1979, when Bruno Salvadori of the Union Valdotaine put together his autonomist list of Contro Roma, that regional autonomy was to make any significant inroads into Italian politics. That event marked the decisive moment for the autonomist leagues that the Bergamascan autonomists had aspired to over 30 years earlier (Gremmo Reference Gremmo2016).

The Bergamascan autonomists’ modest success in electing a provincial and communal councillor in 1956 pales in comparison to the electoral successes of the Lega Lombarda-Lega Nord which would in 1987 elect Umberto Bossi and Giuseppe Leoni to the Senate and the House of Representatives respectively. The Lega would go on to enjoy a level of electoral success that has seen it survive to the time of writing, albeit with a somewhat changed raison d’être compared to its 1980s incarnation.

If, as has been argued by Boulliaud and Dematteo, leghismo was a continuation of mabismo and was thus ‘an old political programme, new only in appearance’ (2004, 45), a pertinent question remains as to why there was such a difference in the political success of each wave of activism. The authors offer Umberto Bossi’s leadership and the changing socio-economic landscape in the 1980s as explanations for the sudden appeal of this ‘old programme’ (2004, 34). Indeed, it is true that Bossi provided the autonomist movement in Lombardy with a much needed injection of charisma and leadership which had been lacking in the 1950s and 1960s. It is also true that 1980s socio-economic conditions were more favourable for a political grouping like the Lega Lombarda-Lega Nord which promised greater innovation for small and family-owned firms in the North-East. However, it is debatable whether Bossi would have been able to sell his project had it not changed in scope since the formation of the MAL in 1948.

This change is strongly linked to both a parallel and paradox which emerges from a comparison of mabismo and leghismo, relating to the two critical junctures in Italian history at which each movement emerged. Mabismo was a product of the post-1945 period and the transition between Fascism and the Republic (later to be known as the First Republic). As a result, the post-war autonomists, with ideals of autonomy and decentralisation that would have been complete anathema to fascist ideology, could present themselves as defenders of the newly born Republic. With the new political entity in its early phases and untouched by the scandals that would later shake the post-war consensus to its core, the regionalism promoted by the MAB in the 1940s and 1950s did not share the anti-nation-state message central to the ideology of leghismo.

The Italian nation-state, defended by the MAB in the post-1945 period, was, conversely, attacked by the Lega Lombarda-Lega Nord from the moment of the movement’s inception in 1984. The Lega’s accusations of corruption against the parties of the First Italian Republic appeared to be vindicated following the tangentopoli scandals in 1992 which led to another moment of transition for the Italian state. The electoral reform of 1993 which followed this scandal, shifting from a proportional to a largely majoritarian system, constituted in the words of Donald Sassoon ‘a real electoral earthquake’ in that ‘all the old parties were either wiped out or emerged as much weakened’ (Sassoon Reference Sassoon1995, 128). These differing contexts thus reflect the changing role of the nation-state in Italian regionalist discourse over a 40-year period.

Anti-fascism

Emerging two years after the end of the Second World War, the MAB presented regional autonomy as a new system of government that could help Italy distance itself from Fascism. The MAB was not alone in presenting regional autonomy as an anti-fascist programme during this period and should be understood in the wider context of a number of movements that were seeking regional autonomy as a bulwark against a return to a dictatorship. This has been demonstrated by Lorenzo Baratter, in his comprehensive history of one of the most significant of these movements, the Associazione Studi Autonomistici Regionali (ASAR) from MAB’s neighbouring province of Trentino. Barratter claimed that post-war demands for autonomy should be considered as being ‘closely linked to that of reconstruction’. Regional autonomy was part of drawing a line under the ‘tragic experience of Fascism and the annexation to Germany and the Third Reich’ (Reference Baratter2009, 18). It should be noted that while there are no explicit links between the MAB and the ASAR, the former was in contact with similar movements and held similar goals relating to regional autonomy, including that of anti-fascism.

The MAB put forward the argument that centralist institutional systems, even if democratic on the surface, always had the potential to deteriorate into totalitarian dictatorships. This is evident from an extract from an essay written prior to the 1956 elections, a mere eight years following the establishment of the Republic, which stated that ‘all centralised states are by their very nature totalitarian … just like all autonomist states of a pluralist nature are by their very nature democratic’ (Meli Reference Meli1955, 45). This was echoed by Anselmo Freddi’s assertion that ‘the original sin of bureaucratic centralism was brought to a grotesque conclusion with the Fascist ventennio’ (Freddi Reference Freddi1963, 10). With anti-fascism as the dominant ideology and myth of the post-war Italian Republic, the MAB strategically aligned their regionalist ideology with prevailing ideological currents. This is evident through the autonomists citing the second president of the Italian Republic, Luigi Einaudi’s, argument that ‘the Regional Body was the only bulwark possible against the return of any form of dictatorship’ (Rinaldi Reference Rinaldi1949, 21).

In terms of a genuine commitment to the anti-fascist Resistance movement, whether there were in fact any partisans involved in the MAB itself is doubtful. In a recent interview, Giuseppe Sala, the son-in-law of a leading MAB exponent, stated that ‘there were certainly people (in the movement) who were anti-fascist, but they did not take part in the partisan brigades’ (Sala Reference Sala2016). That the autonomists were not part of the armed anti-fascist struggle, however, did not exclude them from promoting ideals and politics that had previously been promoted by partisans such as Piero Malvestiti, founder and proponent of Movimento Guelfo D’Azione, the Catholic partisan organisation that had been a precursor to the DC. The MAB, through its publication of leaflets and booklets promoting regional autonomy as a guarantor of democracy and freedom, was in many ways continuing Malvestiti’s tradition of ‘the partisan that knows economy and politics’ (Bocca Reference Bocca1972, 181). Malvestiti had stated that the Resistance ‘as much as an armed struggle, was an intellectual struggle to put forward the right future plan for an Italian state’ (Freddi Reference Freddi1963, 17).

Anselmo Freddi, a leading mabista, was keen to present Bergamascan autonomists as carrying on the local and regional values that had formed this part of the Resistance and, in particular, the 12 points of the ‘Programme of Milan’ drawn up by Movimento Guelfo D’Azione partisans. Freddi highlighted that

in this programme, what was laid out was decentralisation, autonomy and the strengthening of the communes and of the regions: the attribution to the Regions of normative functions, especially in administrative and financial areas. (Freddi Reference Freddi1963, 17).

These ideas, relating to greater freedom and democracy for the nation, played a large part in the MAB’s programme leading up to the 1956 elections, during which it presented a challenge to the DC.

An alternative to the DC

In the 1950s, the fact that the MAB supported the political views of Piero Malvestiti was not only relevant in terms of an anti-fascist message, but also to Bergamo’s Catholic subculture. Malvestiti’s partisan organisation evolved into the DC, with Malvestiti himself going on to serve as a government minister. The MAB, meanwhile, presented itself as an opponent to the DC and sought to penetrate the Catholic subculture in Bergamo. The following paragraphs analyse the MAB’s propaganda and writings aimed at DC voters; this analysis will later be used in the concluding section to challenge the extent to which this element of an ‘alternative to the DC’ demonstrates a link between the two waves of activism by taking into account some important contextual differences.

In terms of the post-war autonomists, the Catholic identity of one of the MAB’s leading exponents, Guido Calderoli, was highlighted by Boulliaud and Dematteo, who argued that the minor breakthrough in the 1956 local election of the Bergamascan autonomists depended on the fact that Guido Calderoli ‘was closely linked to the clergy in Bergamo’. A statement from Innocente Calderoli, Guido Calderoli’s son, that in the elections of 1956, rather than voting for the DC, ‘many priests of Val Brembana asked people to vote for my father’ (Boulliaud and Dematteo Reference Boulliaud and Dematteo2004, 38) is further supported by notes left by fellow activist Aldo Rizzi, which reveal that he and Calderoli often distributed materials and propaganda to priests in the hope that they would spread the message (Rizzi Reference Rizzi1959). The MAB also printed on one of its posters, ‘If you vote for our list you will not be betraying the party of which you are a member’, suggesting that regionalism was a new way of bypassing partisan politics and appealing to a province in which a large number of people voted for the DC (MAB 1956).

Giuseppe Sala, when explaining the reason that his father-in-law, Gianfranco Gonella, had participated in the MAB, stated that the movement had originally ‘adopted a characteristic of Christian Democracy i.e. to claim the importance of local autonomy’. He added that ‘historically, the PPI (Partito Popolare Italiano) was born with this purpose’ (Sala Reference Sala2016). This reference to Luigi Sturzo’s Popular Party is significant as the MAB did indeed attempt to attract a protest vote against the DC by labelling the party as illegitimate heirs of the PPI for not having remained loyal to Sturzo’s autonomist ideal. Guido Calderoli, citing the fact that Bergamo had been the ‘most loyal province to Christian Democracy’ claimed that Bergamascans had been betrayed by the DC’s failure to implement regional reform. This betrayal was viewed not only as damaging to the region, but also dangerous to national unity between Italians (Calderoli Reference Calderoli1958, 111).

The MAB even cited the pope in their electoral campaign in 1958, quoting Pius XIII as saying ‘the region is one of the many forms of unity ... which have been instituted in various states. The regional body has its value and must be conserved and encouraged’ (MAB 1958). According to Guido Calderoli, it was as a result of the MAB’s propaganda in the region that the DC became more open to the idea of regional autonomy and in 1960 ‘printed a brochure entitled ‘We want the region’ (Freddi Reference Freddi1963, 19). As a result the DC eventually came to be seen as ‘the most natural environment … to finally pursue actions and activate institutional autonomy, putting an end to the dualism of belonging to two political organisations’ (Freddi Reference Freddi1963, 20).

This Catholic message was also conflated with federalism with passages from a MAB publication Parole Autonomistiche, containing messages such as ‘only those with a degenerate soul can be opposed to an idea of federalism … those averse to this idea are only those who nestle in the heart of Satan’ (Riva Reference Riva1950, 22). The promotion of federalism in the post-war period therefore ran parallel to the aforementioned Catholic and anti-fascist message and forms the focus of the following section.

Federalism and a (Northern) European identity

The promotion of a federalist republic which looked towards a wider European project to safeguard the rights of the region formed a further theme in the MAB’s political message and another apparent connection with leghismo. Giulio Bergmann, founder of the MAB’s predecessor, the Movimento per le Autonomie Locali, was a member of the small Republican Party and, while never displaying any overt anti-monarchical tendencies, the early Bergamascan autonomists saw themselves as defenders of the 1948 republican constitution and the regional body of government as fundamental to the survival of the Republic. This is evident from the statement by one of the MAL autonomists, Guido Santinoli, in 1948 that with ‘the regional statutes on paper’ it was the ‘duty of the Bergamascan autonomists to ensure that they were activated in the most fruitful manner’ (Freddi Reference Freddi1963, 12).

In terms of looking to a European project, the writings of the Bergamascan autonomists in the post-war period represented a desire to find unity within a European federalist framework, stating, for example, that ‘a European federation is the point of departure, not of arrival’. They insisted that ‘we need to start to think in a European way, in a global way’ (Riva Reference Riva1950, 40). It is therefore unsurprising that one of the MAB’s propaganda postcards introduced a new design for the Italian flag. This flag promoted federalism, republicanism and Europeanism respectively in one fell swoop by adopting the symbol of the Republican Party, an E for Europe and 19 stars which – imitating the federalism of the USA – denoted the number of regions in Italy and the MAB’s desire to see them all activated (Fig. 3). The maintenance of the tricolor is of particular importance in associating Italy, and patriotism with these three values. Regionalism and federalism were seen, in particular, as the ‘point of departure for true patriotism’ (Calderoli Reference Calderoli1958, 79). Indeed, the autonomists in the immediate post-war period were keen to emphasise the need for peace and unity in Europe, claiming that ‘the nation is by nature a unitary creature, even if free and unshackled … maximum freedom does not dissolve unity’ (Riva Reference Riva1950, 33).

Figure 3 The United Federal Republic of Italy was one of The MAB’s earliest ideals. With thanks to Giuseppe Sala and Maria Chiara Gonella.

Following the split of the autonomists in 1961, Ugo Gavazzeni’s Unione Autonomisti d’Italia (UAI) also called for a federation of the peoples of a united Europe, including a protection of the minority languages and their teaching in schools. In this sense, the UAI were talking of a Europe of the Regions even before the concept had officially emerged after the evolution of the European Economic Community into the European Union. Gavazzeni also used the concept of a ‘Padanian’ North at the heart of Europe, promoting a list with the title of ‘Libera Padania’ in the first 1970 regional elections (UAI 1970).

The pursuit of federalism, republicanism and Europeanism in both the 1950s and the 1980s/1990s was a reaction against a Roman central state which was seen as unfairly biased towards the South of the peninsula. As Boulliaud and Dematteo have correctly pointed out, the Bergamascan autonomists always tried to federate ‘without … going beyond the North’ (2004, 36). The 1956 administrative elections would provide an opportunity for the MAB to employ an ‘orientalist’ strategy to define ‘Northern values’ against the Others of the South and Rome.

The ‘invasion of the North by the Other’ encouraged by Rome

The notion of invasion by the Other is a further element which, while tying together the autonomist movements of the 1950s and 1980s, was also affected by their differing historical contexts. Participating in the electoral campaign of 1956 represented a turning point for the Bergamascan autonomists in that ‘the MAB became more identified with the expression of discontent about the continued arrival of southern bureaucrats (Freddi Reference Freddi1963, 16). Calderoli, in particular, was instrumental in portraying southern migrants as the Other, claiming, for example, that

in Bergamo in these past ten years there has been no Bergamascan judge, not even a Lombard one: all of them have been foreigners, a good part of them terroni [a pejorative term for a southerner]… the same can be said for numerous other key jobs. (Calderoli Reference Calderoli1958, 48)

Calderoli called for Bergamascans to ‘rise up against this bureaucratic invasion’, claiming that not to do so would risk ‘divisions between Italians as Bergamo becomes a colony and land of conquest’ (Calderoli Reference Calderoli1958, 16). The notion of the ‘otherness’ of those from the South was further encouraged by the fact that two leading figures in the MAB, Anselmo Freddi and Aldo Rizzi, were both teachers, and were particularly sensitive to the issue of national concorsi (competitive examinations) in the teaching sector and the idea that teachers from the south of the peninsula were being given preference. The populist and nativist message of Us versus Them became particularly vicious in the MAB’s thinly-veiled attempts to cause divisions between Italians, with one of MAB’s exponents stating that

Sending elementary teachers from the South to our mountain valleys is counter-productive … Differences in needs, in customs and habits and way of life constitute an insurmountable barrier to academic output and to understanding. (Pacati Reference Pacati1955, 22)

This highlights that another key aim of the MAB in standing against a bureaucratic invasion was, according to Guido Calderoli, to ‘protect dialect from the assault of the authorities and foreign bureaucrats’ (Calderoli Reference Calderoli1958, 244). Calderoli focused on the presence of bureaucrats in Bergamo who did not speak Bergamascan, stating that it was a bureaucrat’s duty to learn Bergamascan or at least to employ an interpreter (Calderoli Reference Calderoli1958, 244).

The defence of dialect and reaffirmation of local customs was a way of taking a stance not only against southerners, but also against Rome. For the MAB, the idea that Bergamo received such high levels of migration was exacerbated by a perception of Rome’s exploitation through taxation. Calderoli claimed that Bergamo paid more taxes than anywhere else, disbursing ‘40 times more than what it received in return’ (Calderoli Reference Calderoli1958, 244); these claims were accompanied by the image of a parasitic Roman wolf devouring Lombardy (Fig. 4). This notion of exploitation is also well demonstrated by propaganda which, although made famous by the Lega in the early 1990s, was in fact revealed by Boulliaud and Dematteo to have been the brainchild of the Bergamascan autonomists (Fig. 5).

Figure 4 Parasitic Rome sucking the life from the productive North. With thanks to Giuseppe Sala and Maria Chiara Gonella.

Figure 5 “La Gallina dalle uova d’oro”. An image made famous by the Lega, but previously circulated by the MAB. With thanks to Giuseppe Sala and Maria Chiara Gonella.

However, it is important to note that alongside this anti-southern discourse there was a message which appealed to national unity. The MAB viewed region-to-region migration as a detriment to national unity, as it meant that Italians were not working to strengthen their own region and, thus, were weakening the nation-state. It argued that

When the regional autonomies of the constitution are activated … it will no longer be seen necessary to emigrate to other regions … only then will we all live in Italy without treading on each other’s toes. (Freddi Reference Freddi1955, 11)

This concept of regionalism as a force of Italian unity represents a key dividing line between mabismo and leghismo, which is explored in greater detail in the following section.

Continuity and discontinuity

While the 1950s and 1960s saw the emergence of some of the discourse, images and slogans that would later be used by the Lega, the message has changed considerably since the formation of the first autonomist movement, the MAL, in 1947. The changing context of the 1980s and the 1990s, and in particular the transition to the Second Republic following the tangentopoli scandals, led to the Lega abandoning elements which had previously been present in the MAB’s message.

On the surface, a key element of continuity between the mabismo and leghismo appears to be the dichotomous association of bureaucratic centralism with fascist totalitarianism on one hand and regionalism with freedom and democracy on the other. This is evident in the Lega Lombarda’s protests against the centralism of Jean-Marie Le Pen in France, stating that ‘the Le Pen phenomenon demonstrates that wherever regional autonomy is gagged, fascism triumphs!’ (Bossi Reference Bossi1988). Furthermore, it is undeniable that Bossi has always taken a strong anti-fascist position, reflected in his various collections of essays (Bossi Reference Bossi1992; Bossi and Vimercate Reference Bossi and Vimercate1993; Bossi Reference Bossi1994a).

Nevertheless, the Lega’s anti-fascism has always differed from the MAB’s in that it has been employed as a rhetorical device in its portrayal of Rome as an oppressive system linking fascism to the South. Indeed, the Lega takes the view that ‘Fascism was … a Southern product’ whereas ‘the North was the home of the Resistance’ (Levy Reference Levy2015, 52). Additionally, the Lega’s relationship with anti-fascism is much more problematic because of its shift to the right in the early 1990s. This involved the adherence to the Lega of individuals such as Mario Borghezio, who had previously belonged to a number of neo-fascist organisations including Forza Nuova and Ordine Nuovo. More recently, Matteo Salvini’s leadership has led the Lega Nord to lurch even further to the right. Not only has Salvini allied himself closely to Marine Le Pen’s National Front but he has also participated in anti-immigration protests staged by the Italian neo-fascist organisation CasaPound. Additionally, Salvini’s August 2017 electoral campaign for garnering votes in the South of the peninsula, ‘Noi con Salvini’, used an electoral poster which contrasted democracy with fascism, noting that Mussolini and Fascism had ‘made Italy great’ (L’Espresso 2017.) This is a stark contrast with the post-war autonomists, campaigning at a time just after the failed project of Fascism, who portrayed themselves as protectors of the ideal of a new nation to be founded on the basis of local autonomies present during the Resistance.

According to Boulliaud and Dematteo’s study, there were strong links between mabismo and leghismo due to both movements appealing to a localist, anti-statist and anti-unitarian element present in the Catholic subculture in Bergamo (2004, 38–41). Indeed, a conscious appeal of the Lega to former DC voters can be seen in a dedicated section of the Lega Nord publications Lombardia Autonomista and Lega Nord Italia Federale. This section, entitled I Cattolici votano Lega, contained articles which mirrored the message of the MAB as they portrayed the Lega Nord as the natural home for Catholic voters (Grassi Reference Grassi1992; Leoni Reference Leoni1993; Pivetti Reference Pivetti1994). Additionally, the idea of the DC betraying the Bergamascan tradition of autonomy tied into a Catholic subculture, which had been present in Calderoli’s writings, was also echoed by Bossi in his autobiography, when he stated that the autonomist roots of the Popular Party (PPI) had been betrayed by the DC (Bossi Reference Bossi1992, 191). Bossi, like the MAB, also quoted the pope in the Lega’s message in 1984 when he released an article that cited John Paul II’s appeal to protect ‘the general rights of minority populations’ (Bossi Reference Bossi1984).

These similarities, however, are eclipsed by the fact that the MAB failed to penetrate the DC vote in the way that the Lega Nord did in the late 1980s and early 1990s by exploiting the vacuum left by the DC in former ‘white zones’ (traditionally loyal to the DC) and turning them into ‘green zones’ (supportive of the Lega Nord) (Bull Reference Bull2000; Diamanti Reference Diamanti1993; Reference Diamanti1996). While it is true that the DC’s vote in the North was not replaced solely by the Lega Nord, but also by the new political offering of Forza Italia, Bergamo was one particular province which, having previously been a DC stronghold, became one of the key areas of electoral strength of the Lega Nord from 1987 onwards (Agnew Reference Agnew1995, 163–165). The Lega Nord’s appeal to Catholic voters in this province and others was also framed very much in the context of the ‘corruption scandals of the old DC’ (Pivetti Reference Pivetti1994), which sparked the transition from the First to the Second Italian Republic. Bossi portrayed the Lega Nord as the solution to the malaise of the Italian partitocrazia, claiming it had helped a new political fault-line to emerge between liberalist and federalist ideas on the side of the Lega and centralist/statist ideas on the side of the DC (Bossi Reference Bossi1994b). The Bergamascan autonomists of the post-war period, conversely, had never claimed that the role of the DC was defunct in the Lombard region, merely that it needed to adopt regional reform in its political programme.

Closer inspection reveals further discontinuities. The importance of a European identity was present in the early movement’s statute, which shows precocious commitment to a ‘united Europe of the peoples’ (Bossi Reference Bossi1983). As with the MAB, the Lega promoted peace through the European Union and emphasised that ‘European unification is not in contradiction with the Lega’s federalist proposal’ (Bossi Reference Bossi1992; Bossi and Vimercate Reference Bossi and Vimercate1993). Additionally, the Lega’s positioning of Padania’s identity at the heart of Europe seems to reflect a wider link between the Bergamascan autonomists and the Lega, as do parallels between Ugo Gavazzeni’s UAI and the Lega in the 1980s as promoter of ‘the creation of a confederation of European peoples’ (Lombardia Autonomista 1983). This use of Padania at the heart of Europe might be seen as a link between the Bergamascan autonomists and the Lega. However, it should be remembered that Gavazzeni had previously belonged to the same movement that had promoted the Italian tricolour and wished to maintain unity. The Lega Nord’s Padania was a very different concept, promoting its own flag and its own borders, the origins of which lay in a federalism which differed greatly from that promoted in the post-war period.

The statute of the Lega Lombarda, written in 1983, after all the regions had been activated, claimed the objective of ‘transforming the Italian state into a confederation of autonomous regions’, rendering it very different from the aims of mabismo (Bossi Reference Bossi1983). As far as republicanism was concerned, while Bossi claimed in a series of essays in 1994 that he wanted to form a new Federal Italian Republic in 1994, his main interest had always been in a Republic of the North in which Lombardy would form the leading region (Bossi 1994).

This idea of a Northern Republic would evolve into secessionism, forming a key part of the Lega’s hope that, in the event of failing to meet the criteria for the European Monetary Union, Italy would leave northern industry in crisis, thus rendering it more disposed towards the North (Padania) seceding from the South and the central government (Albertazzi and McDonnell Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2005, 955–956). As has been highlighted by Cachafeiro and De Winter, the European identity of the leagues was also due to electoral pragmatism as the advent of the European parliamentary elections acted as a springboard for smaller autonomist movements throughout Europe to promote their programmes (Cachafeiro Reference Cachafeiro2000, 81; De Winter and Cachafeiro Reference De Winter and Cachafeiro2002, 493).

Additionally, the early UAI’s Padania was seen, at most, as a macro-region acting within Italy’s frontiers, not as a separate state. The shift of the Lega to a position of Euro-scepticism following Italy’s entry into the EMU in 1998 represented a significant difference to the pro-European message of the MAB. From the Lega’s point of view, Italy’s accession to the EU represented the EU’s rejection of Padania. Subsequently, the Lega viewed the EU ‘like the Italian state, as a centralist institution and an antagonist of the aspiration for self-government of the Padanian and other European peoples’ (Huysseune Reference Huysseune2010, 69). This anti-European position has intensified under Salvini, who has over the past three years advocated Italy’s exit from the Eurozone and single currency and has used his position as MEP to denounce the EU’s ‘ruining of the European dream’ by impinging on the sovereignty of European nation-states (Lega Nord 2017; Salvini Reference Salvini2017).

Finally, regarding the notion of the invasion of the North, the defence of dialect, local jobs for the local population and the notion of Lombardy as a land of conquest were all present in the discourse of the Lega Lombarda-Lega Nord in the 1980s, as was the use of pejorative language such as terroni to define southerners. For example, Passalacqua’s research (Reference Passalacqua2009) focuses on some of the sentiments present in the Brescian and Bergamascan heartlands of the Lega where the state bureaucracy was often associated with the South.

The Lega recycled the MAB’s discourse surrounding the ‘invasion of the North’ from the South. Indeed, two of the manifestations of anti-southernism revealed by Antonio Moioli’s in-depth study of leghismo in Lombardy, were ‘intolerance towards “terroni” in the public offices of the regions of the North’ and ‘the insistent request to block all financial assistance to the South of Italy’ which had been previously part of the MAB’s political discourse (Moioli Reference Moioli1991, 288). Furthermore, the idea that the state was ‘responsible for an iniquitous fiscal policy that was harmful to the “productive” North and advantageous to the “parasitic” South’ was common to both the MAB and the Lega, as was the idea of the South as ‘a metaphor summing up all that is wrong with Italian society and politics’ (Sales Reference Sales1993, 35–37; Allum and Diamanti Reference Allum and Diamanti1996, 153).

However, the contextual particularities that influenced the anti-southern discourse differed considerably. For example, references to the Mafia in the Lega Nord’s mouthpiece Lombardia Autonomista and Bossi’s early writings are not found in the MAB’s publications. The Lega conflated all southern migration with the measure of state-sanctioned protection afforded to Mafia turncoats who had been relocated to the North (the so-called ‘soggiorni obbligati’). Bossi included in the Lega’s statute that the movement wished to ‘prevent the use of Lombardy’ as a destination of ‘immigrants who had committed crimes’. (Bossi Reference Bossi1992).

Additionally, while many of the arguments used by the Lega against migration from abroad also echo those used by the MAB during the campaign against migration from the South during the 1950s, a changing notion of the Other also marks a significant discontinuity between the two waves of activism. Biorcio (Reference Biorcio1991, 63) highlighted that ‘from 1989, the protest against southerners was for the most part replaced by propaganda hostile towards foreign migration’. Garau (Reference Garau2015, 111) has more recently stated that ‘southerners seem to have now been replaced by non-Italian immigrants’. They are no longer ‘the main concern of the Lega Nord today’, representing a departure from the focus on southern migration which had been one of the key issues for the MAB.

Indeed, an article released as early as 1992 shows how the focus on the Other was shifting from the South towards Islam. Attempting to fan the flames of Islamophobia in Italy, the Lega exploited the news of the expulsion of Islamic Front extremists from Algeria in the early 1990s to conflate extremist Islamism with Islam in general, portraying radical Islamists such as the Islamic Front as the ‘purest’ form of the religion (Lombardia Autonomista 1992). This identification of Islam as a dangerous other, marked an early sign of a nativist and fierce anti-immigration stance which has continued to play a significant role in Lega Nord discourse to this day.

Conclusion

This article has shed light on a previously under-researched autonomist movement, the MAB, and clarified its relationship with the much more familiar contours of the Lega Nord. It is important, as Boulliaud and Dematteo (Reference Boulliaud and Dematteo2004) have shown, to highlight the precedents to the Lega Lombarda-Lega Nord because the Lega can be considered as the revival of the MAB’s previous upsurge of activism during the 1950s, albeit reframed to suit the political context of the 1980s and 1990s. On the other hand, focusing only on the similarities in the regional discourse between the post-war autonomists and the Lega can prove more of a hindrance than a help when trying to understand the success of leghismo in the 1980s and 1990s. The article has shown how two waves of North Italian regionalist activist held very different objectives with regard to the Italian nation-state: in essence, the first wave of activism represented by the MAB used regionalism and federalism to argue for national unity, while the Lega pursued a programme of national fragmentation and secessionism.

The MAB presented itself as a defender of the 1948 republican constitution, arguing that regional government was fundamental to the survival of a democratic, anti-fascist and regionalist Republic during an unstable period of transition for the nation-state. Drawing upon autonomist ideas central to both the Catholic subculture in Bergamo and the anti-fascist Resistance, the Bergamascan autonomists argued that bureaucratic centralism threatened national unity and endangered the democratic principles on which the Republic had been founded. Thirty years later, the Lega reframed anti-fascist discourse to present Fascism as a predominantly southern phenomenon and freedom, liberty, and anti-fascism as essentially Northern qualities. Most recently, as the Lega has lurched to the right under Salvini, the movement has taken a more revisionist view of the Fascist era.

Presenting itself as an alternative to the DC, the MAB argued that the mainstream party’s centralist stance represented a betrayal of Bergamo’s Catholic-autonomist roots and a danger to national cohesion; however, the movement never represented a threat to the DC, and many of its members would eventually join this party. The inability of the MAB to significantly weaken the grip of the DC in Bergamo related to the fact that the movement did not aim to challenge the framework of the Republic after a period of crisis and transition following the fall of Fascism. This represents a significant contrast to the period of socio-political upheaval during the transition between the First and Second Italian Republics, which the Lega exploited to argue for neo-federalism and secessionism.

The MAB’s redesign of the Italian tricolour along republican, European and federalist lines represented a patriotic call to maintain Italian identity, while respecting the regional statutes in the constitution. Conversely, instead of arguing for the regionalism sanctioned by the constitution, the Lega Nord, through proposals for neo-federalist reform and later, threats of secessionism from the Italian state, challenged the very foundations of the Italian Republic which its predecessors had so defended. This argument for secessionism was at times deeply rooted in the focus on difference between the North and South, and drew upon an anti-southern discourse framework which had also been used by the MAB in the 1950s. However, the MAB had qualified its anti-southern position, not with neo-federalism, but with the idea that the nation would be stronger if southerners stayed and worked to improve their own region’s economy. The MAB’s proto-nativist discourse also did not include any references towards migration from abroad or Islam, which would instead later provide the Lega with another target against which to construct a separate Padanian identity.

In conclusion, the fundamental difference between the MAB and the Lega with regard to the region and the nation-state shows how important it is to avoid focusing solely on the continuities in discourse at the expense of the clear discontinuities between the two movements. It also demonstrates the great significance played by the context in which each movement was founded, since the historical environment in which a political movement operates is what makes it unique to its time in terms of purpose, objectives and individual endeavours.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Anna Bull, Aurelien Mondon, Rachel Cohen and Modern Italy’s three anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments on earlier drafts of this article. I’m extremely grateful to Giuseppe Sala and Maria Chiara Gonella for kindly giving me permission to publish their postcards and also for taking the time to meet me and share their insights into the MAB. I wish to thank Dr Paola Palermo from the Archivio Comunale di Bergamo for her permission to reproduce the photographs of electoral lists. A big thank you also goes to Jonathan Newth for his tireless and patient copy-editing work.

Notes on contributor

George Newth is a PhD Candidate at University of Bath and holds an MA in Contemporary Italian Culture and History from UCL. His doctoral research provides a reconceptualisation of the roots of the Lega Nord focusing in particular on its links with 1950s regionalist movements in Lombardy and Piedmont. He has previously published ‘A Brief Comparative History of Economic Regionalism in the North Italian Macro-region and Catalonia’ (Progressus: Rivista di storia, University of Siena, 2014). He was the ASMI Post-Graduate Representative between 2015 and 2017 and chaired the Organising Committee of the ASMI Postgraduate Summer School in 2016.