On June 21, 1788, New Hampshire voted to ratify the new United States Constitution, producing the nine state majority required for the governing charter to go into effect, and triggering the first federal elections. But the document had not just emerged from the Constitutional Confederation after a few months of debate. The process of winning independence, surviving the collapse of the Confederation Congress, garnering support for constitutional reform, and obtaining ratification had made for an arduous 12 years. The experience of enduring the 1770s and 1780s framed the way that the convention delegates, the first government officials, and the voters viewed the Constitution.

George Washington was no exception. Washington's constitutional interpretation and his political theory have largely escaped the grasp of historians. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he did not outline his vision during the convention, nor did he draft lengthy pieces urging ratification during the state conventions. He did not pen voluminous manifestos on political systems the way Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, or James Madison did, nor did he author founding documents that shaped the United States's political tradition.Footnote 1

Scholars have largely focused on Washington's presidency for its symbolic value and its contribution to the development of the executive branch. Works by Edward Larson, John Ferling, and Kathleen Bartoloni-Tuazon have examined his broader vision for the new nation, emphasizing his nationalism, his political intelligence, and his unifying role at the critical moment of conception. Others, including Richard Smith, John Ray, and Matthew Spalding, have explored how he established countless precedents and filled in the details of the executive branch through his daily governing practices.Footnote 2 Only a few scholars have considered Washington's presidency through an intellectual approach. Recent works by Larson, Kevin Hayes, and Adrienne Harrison suggest a more robust mind at work than previous scholarship had acknowledged.Footnote 3

Washington's grasp of political ideology takes on oversized importance in the twenty-first century given the awesome scope of precedents he established during the first administration. His approach to the presidency reflected his conviction that the American people ratified the Constitution in order to create a new federal government, led by a single executive with power and energy to enforce the law. His actions in office indicated a commitment to the concept of a strong presidency, while revealing flexibility when it came to the text of the Constitution.

This article explores Washington's annotated copy of the Constitution and the Acts of Congress (hereafter called the Acts of Congress to remain consistent with the label Washington had placed on the front cover) to reveal new insights into his constitutional interpretation. Held in a private collection until 2012, this article is the first to examine Washington's notations in the Acts of Congress for their value as statements about political authority. Whereas other scholars, most recently Jonathan Gienapp, have explored how the debates in the 1790s challenge originalist arguments, this article demonstrates how Washington developed his own powerful interpretation of Article II of the Constitution.Footnote 4 Previous scholarship tends to paint the First Federal Congress as the venue for debate about constitutional interpretation, whereas Washington was relegated to the sidelines, setting precedent and tending to matters of state.Footnote 5 This distinction is a creation of modern scholarship. In fact, Washington paid careful attention to Congress's deliberations, and congressmen watched the president's actions to inform their understanding of the clauses contained in the Constitution. In 1993, Glenn Phelps demonstrated how Washington did not leave constitutional interpretation to the Supreme Court or Congress, but rather developed his own theories about executive power.Footnote 6 Yet, Washington's annotated copy of the Acts of Congress was still hidden from view when Phelps examined Washington's constitutionalism.

Washington's comments in the margins of his volume suggest an evolving view of presidential power and constitutional limitations on the executive branch as early as January 1790. His margin notes on the Acts of Congress served as blueprint for his defense of presidential authority and the expansion of the executive branch in the 1790s. Many scholars attribute the development of executive branch and the president's powers to Hamilton's financial ambitions and Washington's acquiescence to those plans.Footnote 7 At most, scholars credit Washington's sterling reputation and near-kingly status for the enlargement of presidential authority.Footnote 8 On the contrary, Washington interpreted the Constitution to acquire additional authority. In particular, he rejected the options outlined for the president in Article II and created the cabinet to support him in moments of diplomatic crisis, domestic insurrection, and constitutional uncertainty.Footnote 9 Finally, the annotated Acts of Congress inserts Washington's ideas about the presidency into the debate surrounding originalism by revealing how his analysis of the language evolved to meet the demands of governing, leading him to reject the delegates’ intent for Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution.Footnote 10

*******

Washington's experiences during the Revolutionary War and the Confederation Period shaped his views of the Constitution and presidential authority. During the war, Congress had no enforcement mechanism to compel the states to contribute men, supplies, or money to support the army. Instead, Congress depended on each state to voluntarily abide by its requests. Often, state governments hoarded supplies for their own militias and refused to levy the necessary taxes on their citizens to meet congressional demands. The states worried that if they supplied the Continental Army, no local troops or supplies would be left to defend their local communities from British attack. Furthermore, the states feared that a standing army would threaten their liberties. After the war, Congress's inability to raise funds continued. It still relied on voluntary requisitions from the states and could not defend the nation from domestic or foreign threats. These challenges convinced Washington that the national government needed more expansive powers to wrangle the states and their conflicting interests.Footnote 11

Washington voiced his frustrations in private communications. On March 21, 1781, Washington wrote to Benjamin Harrison, “If the States will not, or cannot provide me with the means; it is in vain for them to look to me for the end, and accomplishment of their wishes. Bricks are not to be made without straw.”Footnote 12 As he prepared to relinquish his military commission in June 1783, Washington emphasized that “it [was] indispensable to the happiness of the individual States that there be lodged somewhere, a supreme power to regulate and govern the general concerns of the confederated Republic.”Footnote 13 Washington referred to his Revolutionary War experience: “the [country's] distresses and disappointments, which have very often occurred, have in too many instances resulted more from a want of energy in the Continental Government, than a deficiency of means in the particular States—That the inefficacy of measures, arising from the want of an adequate authority in the supreme Power…served also to accumulate the expences of the War.”Footnote 14

By 1786, Washington no longer believed that the Confederation Congress, with its executive departments in lieu of an executive branch, could govern the nation with sufficient diligence and firmness. Washington confessed to Secretary of Foreign Affairs John Jay that congressmen “would be induced to use [legislative authority], on many occasions, very timidly & inefficatiously for fear of loosing their popularity.”Footnote 15 The outbreak of Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts confirmed his fears. Congress's and Massachusetts's inability to suppress the rebellion further convinced Washington that the new nation needed great centralized power.Footnote 16

On May 8, 1787, Washington left Mount Vernon to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.Footnote 17 He participated because he believed that the convention represented the best opportunity to reform the government. He was also convinced that the delegates shared a common goal of remedying the deficiencies of executive authority in the Confederation Congress. These expectations framed his understanding of the delegates’ debates and decisions adopted during the convention.

Washington's role in the convention also shaped his understanding of the final Constitution and the role of the presidency in the new federal government. He arrived in Philadelphia on Sunday, May 13.Footnote 18 Over the next 10 days, while waiting for other delegates to arrive, he gathered with Madison, Edmund Randolph, and other members of the Virginia delegation. They crafted their strategy for the convention and drafted the Virginia Plan, which featured a powerful bicameral legislature and executive. Once enough delegates arrived to reach a quorum, they unanimously elected Washington the president of the convention.Footnote 19 During the sessions, he frequently sat on the raised platform in front of the room or huddled with the Virginia delegation. As the presiding officer, he said very little during the convention. Washington was never a great orator, and he preferred to listen to the other delegates. He also suspected that his words would hold great weight, and he strove to avoid accusations that he dictated his wishes to the convention or the American people.Footnote 20

Once the workday ended, Washington participated in a lively social scene. He lived with Robert Morris, a Pennsylvania delegate.Footnote 21 He attended the theatre, drank tea, ate dinner, and went riding with the elite families in Philadelphia. Many of the other delegates attended these social events with Washington. These gatherings offered an opportunity to discuss the latest proposals and negotiate deals in a private, less intense setting. They also provided Washington with critical information about how the delegates perceived the clauses contained in the ever-changing draft of the Constitution.Footnote 22

After the convention, Washington remained keenly interested in the progress of the proposed government. He sent copies of the final draft of the Constitution to leading statesmen—including Thomas Jefferson and the Marquis de Lafayette abroad, and Benjamin Harrison, Edmund Randolph, and Patrick Henry at home—and urged them to support ratification.Footnote 23 On October 6, 1787, James Wilson delivered a speech in favor of the Constitution at a public meeting in Philadelphia. Washington read Wilson's speech on October 17, after it was published in the General Advertiser. When Washington read Wilson's interpretation of the Constitution, he found the argument so compelling that he sent the speech to David Stuart for publication in Virginia newspapers so that Virginians would understand how to interpret the draft: “As the enclosed Advertiser contains a speech of Mr Wilson's (as able, candid, & honest a member as any in Convention)…The republication (if you can get it done) will be of service at this juncture.”Footnote 24 On November 5, 1787, Washington sent Stuart additional materials that he hoped would turn the tide in favor of ratification, including a pamphlet titled “An American Citizen,” a broadside written by Tench Coxe and originally published in Philadelphia.Footnote 25

Washington closely followed the debates at the state ratification conventions and in the press. He believed that the nation's future depended on the ratification of the new government, but he also wanted to know how citizens perceived and interpreted the proposed constitution. Washington subscribed to many newspapers from across the country and read them daily. When new guests arrived at Mount Vernon, he quizzed them on the progress of ratification in their home states.Footnote 26 Washington also carried on an extensive correspondence with friends and colleagues across the country. When their letters bearing news of the conventions did not arrive promptly, Washington sent his enslaved manservant, William Lee, down to Alexandria to fetch the mail.Footnote 27

Washington's close attention to the convention and ratification debates reflected his firm commitment to the new nation, but also his need to understand how other Americans understood the language contained in the Constitution. As soon as the delegates agreed to a single executive, everyone present, including Washington, understood that he would be the first president. No one else matched his reputation or record of public service. The words in the Constitution, and how they were interpreted, would serve as his guide once he took office. Washington viewed the creation of the Constitution and its ratification by the states as public validation for more expansive presidential power. The delegates and the American public had confirmed his own opinions about the nature of government and the need for a unified executive authority.

*******

After his inauguration on April 30, 1789, Washington entered office expecting to utilize the governing options exactly as they were described in the Constitution. Those options included Article II, Section 2, which states that the president “shall have power, by and with advice and consent of the Senate, to make treaties…appoint ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, judges of the court, and all other offices of the United States.”Footnote 28

Yet, the delegates interpreted this clause differently than many twenty-first-century audiences do. In earlier drafts, the delegates had considered and then explicitly rejected three proposals for an executive council to provide advice to the president. First, they considered the executive council presented in the Virginia Plan. This council, composed of members of the executive and judicial branches, would help the president review and enforce legislation.Footnote 29 Second, they considered an advisory council proposed by Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina that included the future executive departments and the president's private secretary. Although this council would provide advice and support, the president would not be bound to follow his advisors’ recommendations and the council would not limit his authority in any way. Finally, they considered a council suggested by George Mason, based on the Council of State in his home state of Virginia. Two members from each region—New England, the mid-Atlantic, and the South—would sit on Mason's council, advise the president, and serve as a check on executive authority. The delegates rejected all three of these proposals, including Pinckney's advisory council, which looked startlingly like the future cabinet created by Washington.

Instead, they expected that the Senate would serve as a council for foreign affairs. They believed that the Senate, consisting of only twenty-six members in 1789, was small enough to advise the president while still answering directly to the American people through elections.Footnote 30 The delegates also included a provision for the president to obtain written advice from the department secretaries on issues pertaining to their department. This clause contained two important restrictions.Footnote 31 First, the president needed to request written advice. The inclusion of the word “written” indicated the delegates’ intent to ensure that each secretary would take responsibility for his opinions and maintain transparency in the governing process. Second, the secretaries could provide advice on issues in their areas of expertise. These two clauses, taken together, demonstrate that the delegates resolved against in-person advice in group meetings, which would obscure the decision-making process.Footnote 32

The ratification debates confirmed this interpretation. When critics of the Constitution, including Mason, protested the lack of an executive council, many delegates retorted that the Senate rendered a council unnecessary. The Anti-Federalist contingent at the Pennsylvania State Ratification Convention further supported the expectation that the Senate would serve as a council on foreign affairs. In fact, this prospect served as the lynchpin of their arguments against ratification. They worried that the Senate would acquire too much executive power or would be forced to remain in session year-round, at enormous expense to the taxpayers, just to advise the president.Footnote 33

Washington shared these expectations. In late May, he submitted all the previous treaties between the United States and Native American nations for the Senate's consideration.Footnote 34 In early August 1789, he planned his first visit to the Senate to discuss foreign affairs. Washington started by meeting with a committee to plan the details of his visit.Footnote 35 Two days before the scheduled date, he sent official notice that he would arrive at 11;30 in the morning on August 22 to “advise with them on the terms of the Treaty to be negotiated with the Southern Indians.”Footnote 36 On the day of the meeting, he brought Henry Knox, Acting Secretary of War, to answer questions or provide additional details as needed, and a list of questions to guide the senators’ discussion.Footnote 37

Despite Washington's careful preparations, after he delivered his address, the senators sat in silence. They shuffled their papers, cleared their throats, and avoided making eye contact with him. After several minutes, Senator William Maclay of Pennsylvania suggested that Washington return the following Monday, so that they could discuss the issue further in committee. Outraged, Washington yelled, “this defeats every purpose of my coming here!”Footnote 38 When Washington regained his composure, he agreed to return a few days later for the committee's report. But on his way out of Federal Hall, he reportedly swore that he would never again return to the Senate for advice. He kept his word.Footnote 39

Washington's rejection of the Senate as a council on foreign affairs acquired additional significance, considering his order of the Acts of Congress 1 month later. On September 29, 1789, Congress concluded its first session. Sometime during the next 2 weeks, Washington sent a private order to Francis Childs and John Swain, owners of a prominent printing house in New York City. Washington requested that they print and bind a copy of the Constitution and all the laws passed during the first session of the Federal Congress. He instructed them to include a personalized plaque on the front of the volume that read “President of the United States.” Washington also ordered additional copies of the volumes for his department secretaries and Chief Justice John Jay.Footnote 40 Washington placed this order after the end of the first congressional session and before his departure for a tour of the Northern states on October 15, 1789.Footnote 41 On December 9, Washington received his volumes after he returned from Boston.

Washington's notations in his volume help explain how he viewed executive authority. On the sixth page, next to the second paragraph of Article I, Section 7, Washington drew a bracket and wrote the word “President.” This clause describes the president's right to veto legislation. On the seventh page, next to the third and fourth paragraphs of Article I, Section 7, Washington drew two more brackets with the word “President” next to each clause. The first clause explains that if the president fails to sign the legislation within 10 days, the bill will become law. The second paragraph outlined the process by which Congress could override the president's veto. Washington likely added “President” next to these paragraphs to demarcate the separation of powers and the authority granted to his office (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Acts Passed at a Congress of the United States of America (New York: Francis Childs and John Swaine, 1789). Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies' Association.

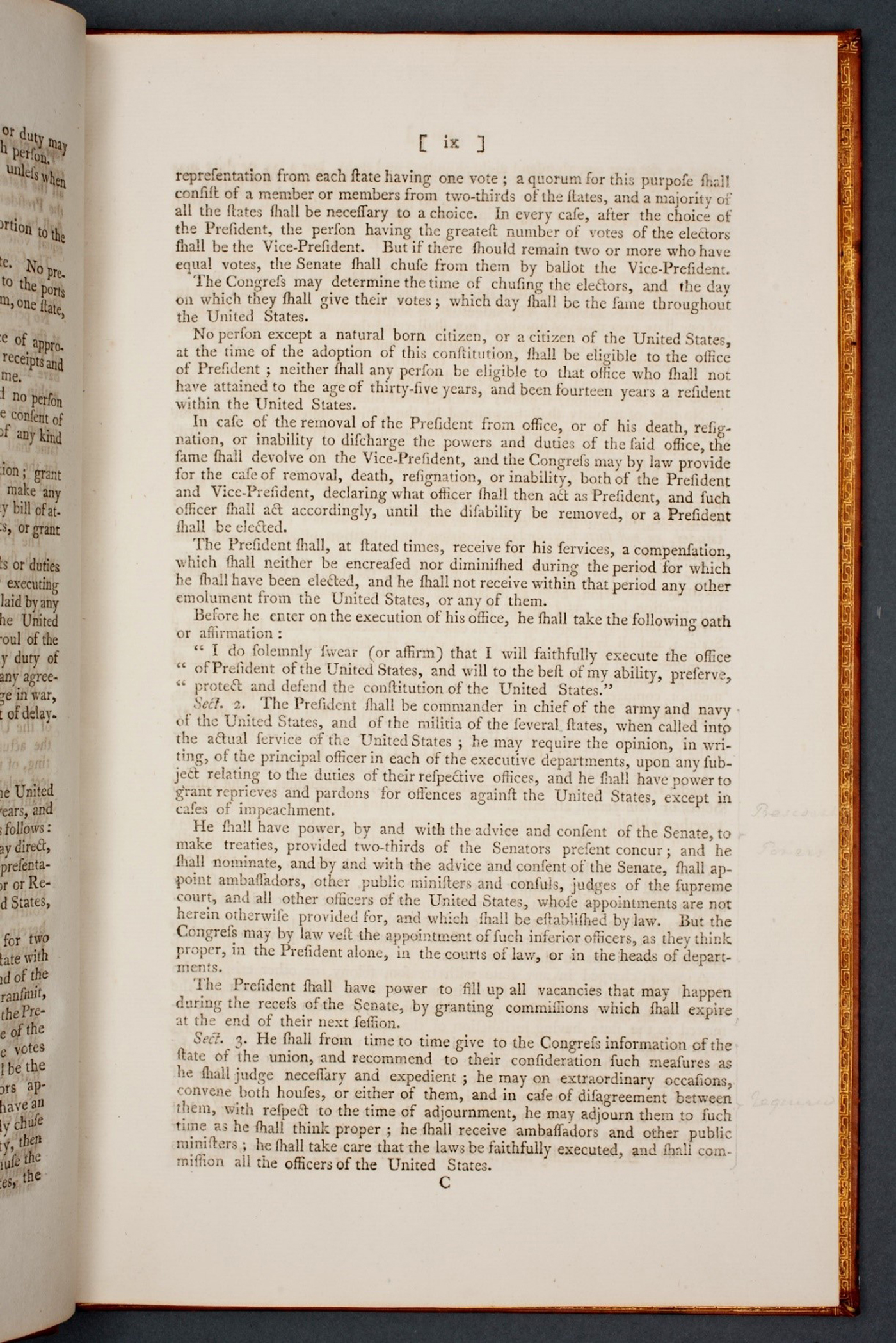

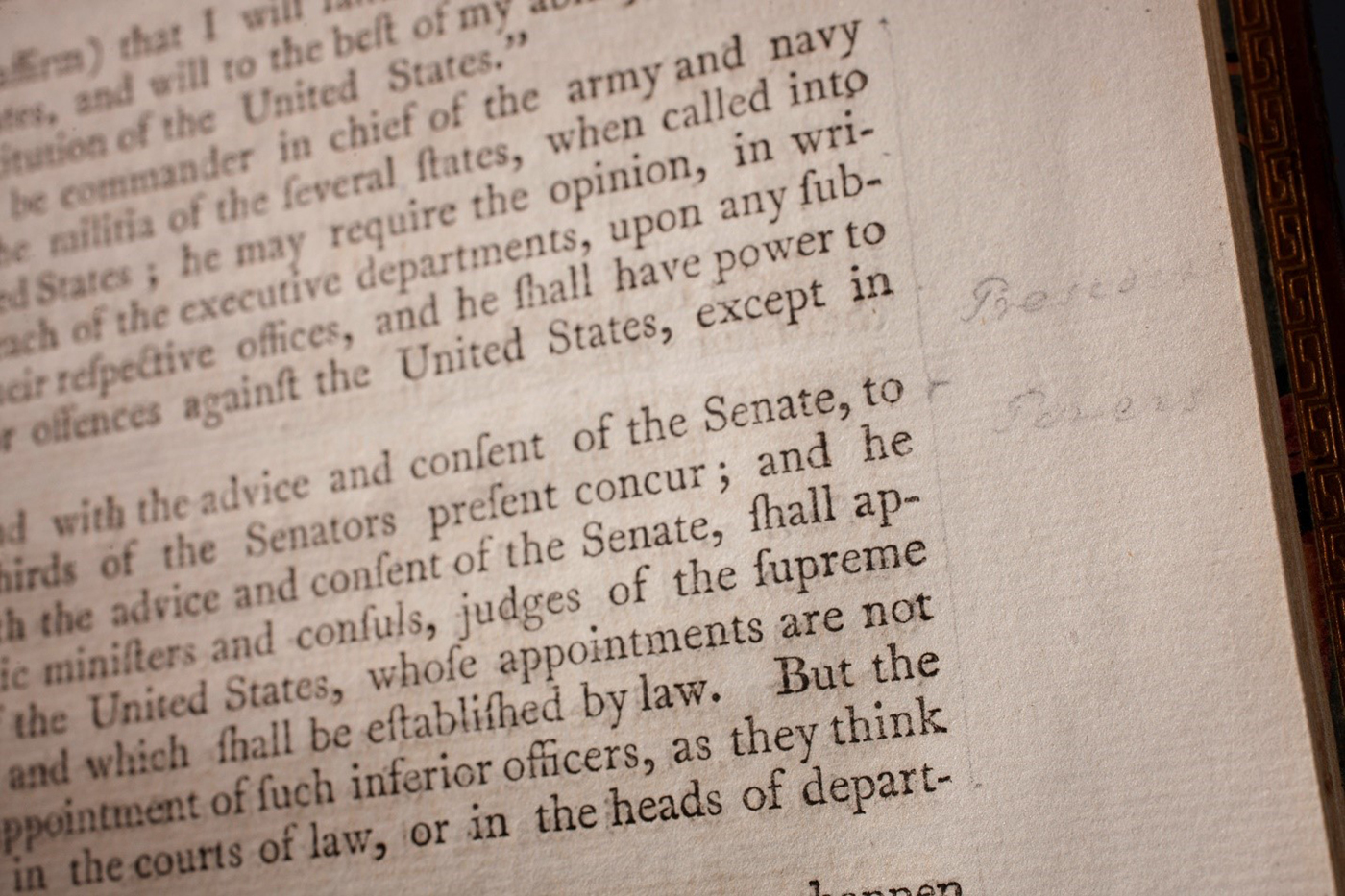

Washington paid extra attention to Article II, which outlined the president's duties and responsibilities. Article II, Section 2 states that the president “may require the opinion, in writing, of the principal officer in each of the executive departments, upon any subject relating to the duties of their respective offices.” Additionally, Article II, Section 2 states that the president “shall have power, by and with advice and consent of the Senate, to make treaties…appoint ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, judges of the court, and all other offices of the United States.” Next to these clauses, Washington drew another bracket and wrote the phrase “President Powers” (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Acts Passed at a Congress of the United States of America (New York: Francis Childs and John Swaine, 1789). Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies' Association.

Article II, Section 3 states: “He shall from time to time give to the Congress information of the state of the union, and recommend to their consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.” Next to this clause, Washington wrote the word “Required”Footnote 42 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Acts Passed at a Congress of the United States of America (New York: Francis Childs and John Swaine, 1789). Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies' Association.

Evidence suggests he jotted down these comments after December 9, when he delivered a similar volume to Jay, and before he delivered his annual address to Congress on January 8, 1790. Washington probably wrote his remarks as he prepared his first annual address to Congress in early January 1790. He probably did not make these notations after 1790. Washington ordered a new bound volume of the Constitution and the acts passed by Congress for each year of his presidency. After receiving a new volume in late 1790, it is unlikely that he would have returned to an outdated edition and inscribed notations.Footnote 43

These notations demonstrate that Washington distinguished between mandatory actions “Required” of him as president and the options available to him at the discretion of the “President,” such as those outlined in Article II, Section 2. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Washington almost never wrote in the margins of his books, indicating that his notations in the margins of the Constitution were not mindless scribbles. Washington was also quite particular about the written record his left for historians to study.Footnote 44 He bequeathed all of his papers and books, including the Acts of Congress, to his nephew and Supreme Court Justice, Bushrod Washington.Footnote 45 He knew future readers would see and study the comments. Finally, he meant what he wrote. In Article II, Section III, Washington labeled the annual addresses and the duty to provide suggestions to Congress as “required.” He believed that the Constitution obligated him to provide annual updates to Congress. He noted this responsibility and faithfully compiled an annual report for Congress at the beginning of each annual session.Footnote 46 Significantly, he did not write “Required” next to Article II, Section 2.

On the other hand, Washington believed that the delegates at the Federal Constitution had intended to create a powerful executive to remedy the issues of the Confederation Period. Accordingly, it provided to the president certain powers to use at his discretion, including consulting the Senate if it served him well. Washington determined that the Constitution did not require him to consult with the Senate on foreign affairs, otherwise he would have noted “required” next to these provisions. Significantly, Washington notated his copy of the Constitution after his failed visit to the Senate's chambers in August. He described the “advice and consent” function of the Senate as “President Powers” after he had already discounted the Senate as a viable council on foreign affairs.

*******

Article II, Section 2 also states that the president “may require the opinion, in writing, of the principal officer in each of the executive departments, upon any subject relating to the duties of their respective offices.”Footnote 47 This grant of authority contains two critical clauses. First, the opinions must be in writing to ensure transparency at the highest levels of office and to force government officials to take responsibility for their positions. Second, the secretaries may only provide advice on issues pertaining to their departments, to prevent them from interfering in matters beyond their area of expertise.Footnote 48

Washington initially limited himself to written correspondence with the secretaries, but he quickly discovered that the issues facing the government were much too complex to manage through writing alone. By January 1790, he was requesting written opinions, followed by an in-person meeting to discuss follow-up questions or tricky details. Individual conferences also proved insufficient.

Washington's notations on his Acts of Congress indicated his belief that the Constitution provided a mandate for a strong, independent executive. He believed that the options outlined in Article II, Section 2 failed to provide adequate means for the president to obtain advice. Instead, Washington focused on the spirit of the clause as implicitly granting him the power to create an executive cabinet if he needed one to fulfill his expressly mandated powers.

On November 26, 1791, Washington summoned his first cabinet meeting to discuss ongoing conflict with Great Britain and France. The meeting exposed his belief that pressing diplomatic issues required more advice than Jefferson, the secretary of state, could provide. He needed the input of all his secretaries and attorney general, and he benefited from their vigorous debate. Over the next 5 years, he organized ninety-seven cabinet meetings to advise on constitutional questions, domestic insurrections, and diplomatic crises. The department secretaries, through cabinet meetings, played an integral role in the administration's response to precedent-setting moments in the 1790s, including the neutrality crisis, the Whiskey Rebellion, and Jay's Treaty. They helped Washington establish rules of neutrality, assert the federal government's right to tax its citizens and enforce compliance, and invoke executive privilege. In each of these moments, the secretaries encouraged him to assert presidential power at the expense of Congress and the state governments. The cabinet proved to be central to the expansion of executive authority in the 1790s.

Yet, the delegates at the Constitutional Convention had rejected the cabinet, and the Constitution contains provisions that specifically guard against the “dangerous cabals” feared by the delegates.Footnote 49 Washington had witnessed the debates and understood the delegates’ intentions toward the cabinet. But he also believed that the constitutional reforms intended to create a strong executive and that Article II granted the president enough authority to govern effectively, including the authority to deviate from the delegates’ original intent. When the provisions outlined in Article II, Section 2 proved insufficient, Washington elected to view them as suggestions, rather than as binding limitations. He did not write down that he explicitly rejected the options outlined in the Constitution, but his actions indicated that he adopted an alternative path: a subtle form of rejection. He did not think that the Constitution was bad, unimportant, or irrelevant, but rather that the cabinet offered him the advice he needed to govern effectively. Each president since Washington has organized a cabinet based on his precedent. More importantly, each president selects his own trusted advisors and manages those relationships without congressional or public oversight.

*******

Any discussion of presidential power granted by the Constitution must begin with Washington. Article II tersely outlines the authority of the executive branch but is quite reticent with details about how the president should exercise that authority, especially compared with the institutions provided to other branches of government about how to use their power. With little guidance or examples to follow, Washington fleshed out the specifics of daily governance. When the parameters of the Constitution failed to provide the support that Washington needed to address the conflicts he faced, he decided to focus on the intention that motivated the grant of power, or rather the intention as he interpreted it. Washington's annotated Acts of Congress reveals this interpretation more clearly than any published material he produced. The document also explains how he justified expansive use of executive authority and the creation of the president's cabinet. Finally, the Acts of Congress place Washington squarely at the center of the originalist debate. Washington disregarded the delegates’ intent to prohibit a cabinet. Instead, he focused on the grants of power contained in the Constitution and created the advisory body that he needed to govern.